Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

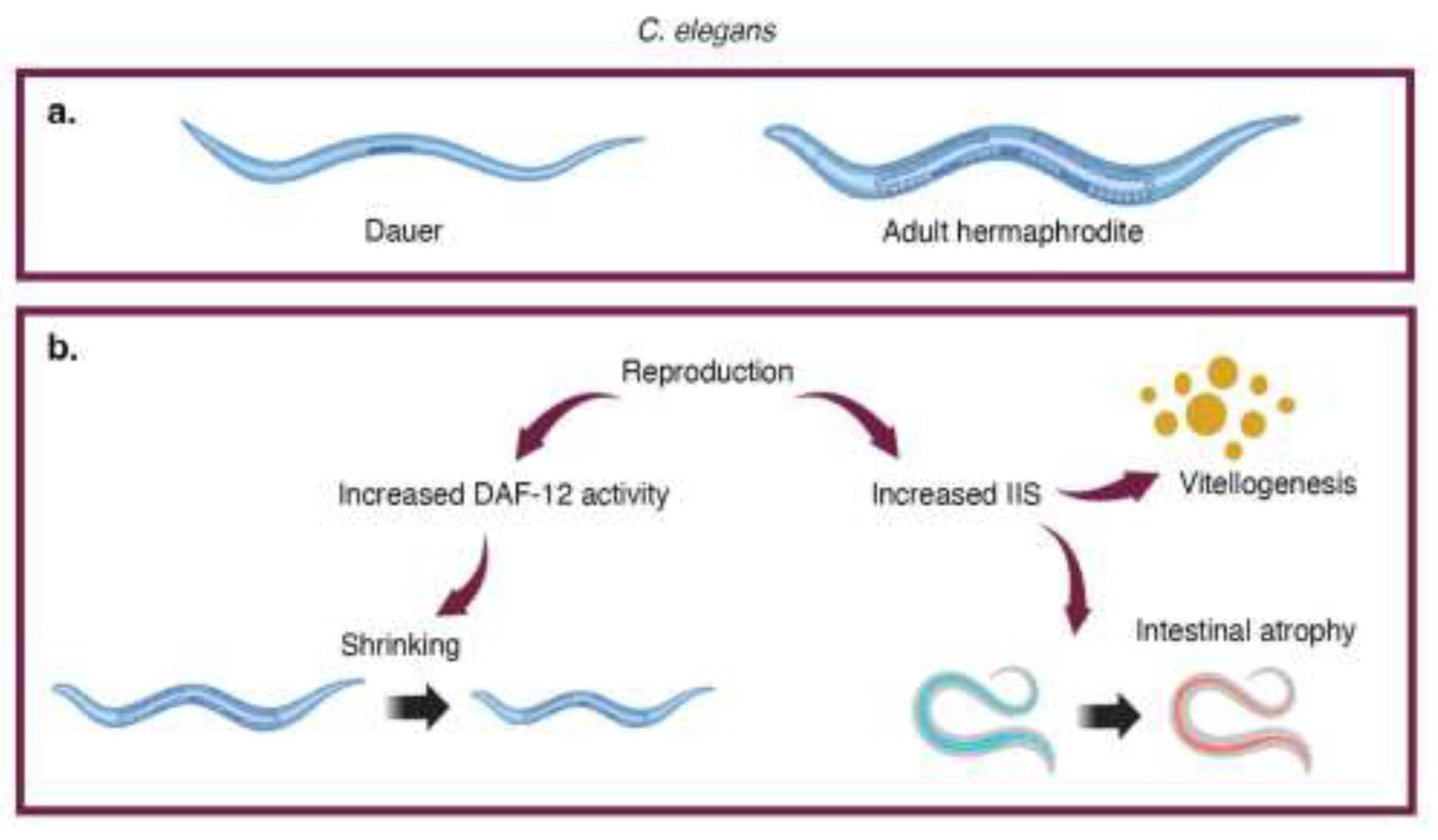

C. elegans

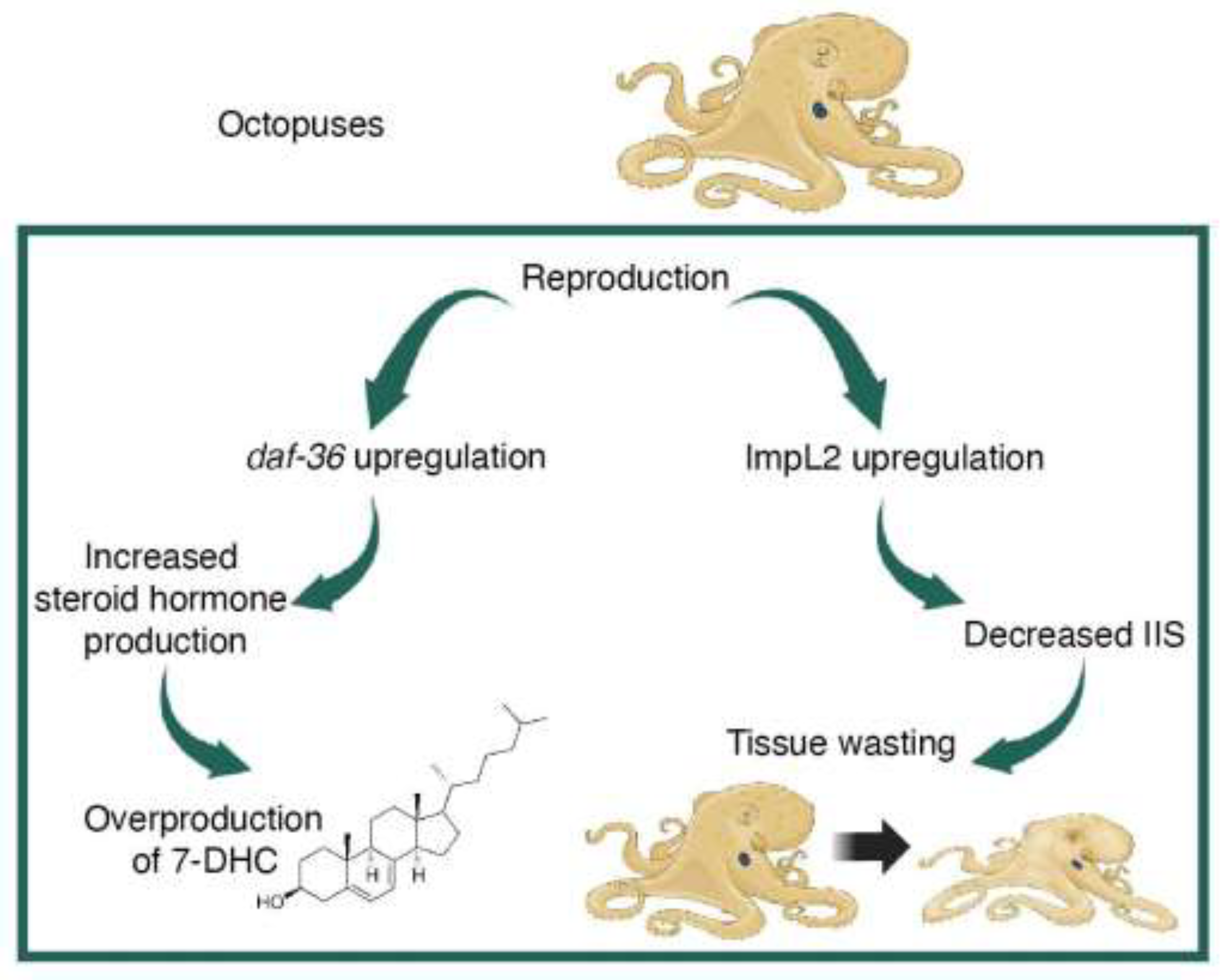

Octopuses

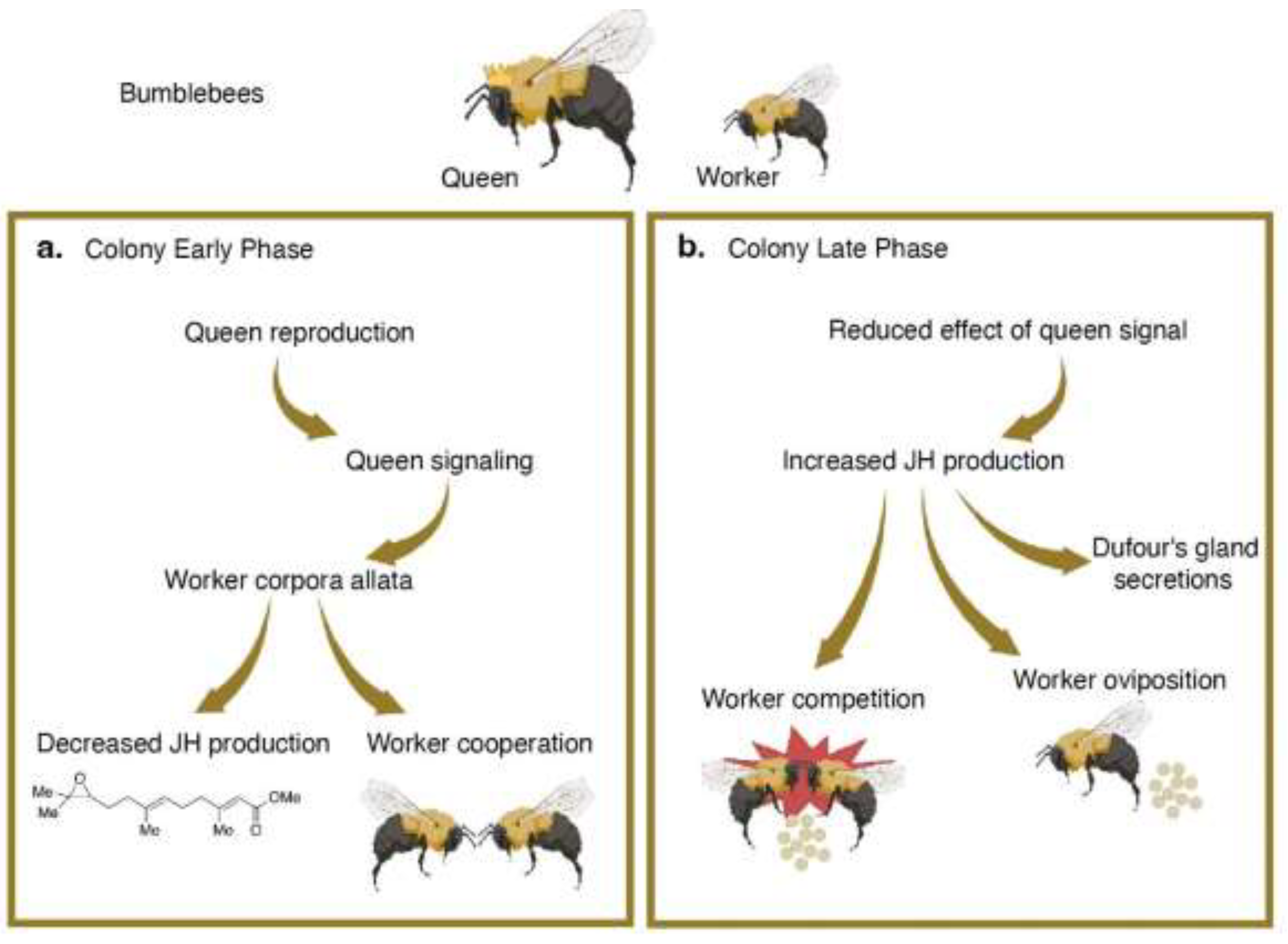

Bumblebees

Conclusions

References

- Northcutt RG: Evolution of centralized nervous systems: two schools of evolutionary thought. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109 Suppl 1:10626–10633. [CrossRef]

- Hartenstein V: The Central Nervous System of Invertebrates. In The Wiley Handbook of Evolutionary Neuroscience. Shepherd, S V. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016:173–235.

- Picard MAL, Vicoso B, Bertrand S, Escriva H: Diversity of Modes of Reproduction and Sex Determination Systems in Invertebrates, and the Putative Contribution of Genetic Conflict. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12:1136A sweeping examination of invertebrate reproduction, focusing on sexual vs asexual reproduction and sex-determination systems. This broader analysis is a valuable tool in analyzing the implications of these systems.

- Hughes PW: Between semelparity and iteroparity: Empirical evidence for a continuum of modes of parity. Ecology and Evolution 2017, 7:8232–8261. [CrossRef]

- Finch CE: Longevity, senescence, and the genome. University of Chicago Press; 1990.

- Mack HID, Heimbucher T, Murphy CT: The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for aging research. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models 2018, 27:3–13. [CrossRef]

- Cassada RC, Russell RL: The dauerlarva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology 1975, 46:326–342. [CrossRef]

- Albert PS, Riddle DL: Mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans that form dauer-like larvae. Developmental Biology 1988, 126:270–293. [CrossRef]

- Riddle DL, Swanson MM, Albert PS: Interacting genes in nematode dauer larva formation. Nature 1981, 290:668–671. [CrossRef]

- Mahanti P, Bose N, Bethke A, Judkins JC, Wollam J, Dumas KJ, Zimmerman AM, Campbell SL, Hu PJ, Antebi A, et al.: Comparative metabolomics reveals endogenous ligands of DAF-12, a nuclear hormone receptor, regulating C. elegans development and lifespan. Cell Metab 2014, 19:73–83.

- Chasnov JR, Chow KL: Why are there males in the hermaphroditic species Caenorhabditis elegans? Genetics 2002, 160:983–994. [CrossRef]

- Maures TJ, Booth LN, Benayoun BA, Izrayelit Y, Schroeder FC, Brunet A: Males Shorten the Life Span of C. elegans Hermaphrodites via Secreted Compounds. Science 2013, 343:541–544. [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra M, Benedetto A, Sornda T, Gilliat AF, Au C, Zhang Q, van Schelt S, Petrache AL, Wang H, de la Guardia Y, et al.: C. elegans Eats Its Own Intestine to Make Yolk Leading to Multiple Senescent Pathologies. Current Biology 2018, 28:2544-2556.e5.

- Kern CC, Srivastava S, Ezcurra M, Hsiung KC, Hui N, Townsend S, Maczik D, Zhang B, Tse V, Konstantellos V, et al.: C. elegans ageing is accelerated by a self-destructive reproductive programme. Nat Commun 2023, 14:4381. A comparison of Caenorhabditis and Pristionchus reproductive programs, focusing on presence or absence of programmed death phenotypes in other species. The findings support C. elegans reproductive death, as yolk venting and other phenotypes only occur in hermaphrodites.

- Shi C, Murphy CT: Mating Induces Shrinking and Death in Caenorhabditis Mothers. Science 2014, 343:536–540.

- DePina AS, Iser WB, Park S-S, Maudsley S, Wilson MA, Wolkow CA: Regulation of Caenorhabditis elegans vitellogenesis by DAF-2/IIS through separable transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. BMC Physiology 2011, 11:11. [CrossRef]

- Venz R, Pekec T, Katic I, Ciosk R, Ewald CY: End-of-life targeted degradation of DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor promotes longevity free from growth-related pathologies. eLife 2021, 10:e71335. Degradation of DAF-2 receptors during aging extends C. elegans lifespan beyond that of daf-2 mutants. This is notable because it delivers relief from aging phenotypes without the detrimental effects of reduced IIS signaling in early life.

- Kim S-S, Lee C-K: Growth signaling and longevity in mouse models. BMB Rep 2019, 52:70–85. [CrossRef]

- Kenyon C: The Plasticity of Aging: Insights from Long-Lived Mutants. Cell 2005, 120:449–460.

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G: daf-2, an Insulin Receptor-Like Gene That Regulates Longevity and Diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 1997, 277:942–946.

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R: A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 1993, 366:461–464. [CrossRef]

- Kern CC, Townsend SJ, Salzmann A, Rendell NB, Taylor GW, Comisel RM, Foukas LC, Bähler J, Gems D: C. elegans feed yolk to their young in a form of primitive lactation. Nature Communications 2021, 12:5801. Demonstrates that yolk venting in C. elegans benefits the offpsring and delves further into the mechanics of IIS control of yolk production and venting.

- Zhao Y, Gilliat AF, Ziehm M, Turmaine M, Wang H, Ezcurra M, Yang C, Phillips G, McBay D, Zhang WB, et al.: Two forms of death in ageing Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun 2017, 8:15458. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Zhao Y, Ezcurra M, Benedetto A, Gilliat AF, Hellberg J, Ren Z, Galimov ER, Athigapanich T, Girstmair J, et al.: A parthenogenetic quasi-program causes teratoma-like tumors during aging in wild-type C. elegans. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2018, 4:6. [CrossRef]

- Sharma KK, Wang Z, Motola DL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Auchus RJ: Synthesis and activity of dafachronic acid ligands for the C. elegans DAF-12 nuclear hormone receptor. Molecular Endocrinology 2009, 23:640–648. [CrossRef]

- Hsin H, Kenyon C: Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans. Nature 1999, 399:362–366. [CrossRef]

- Dumas KJ, Guo C, Wang X, Burkhart KB, Adams EJ, Alam H, Hu PJ: Functional divergence of dafachronic acid pathways in the control of C. elegans development and lifespan. Dev Biol 2010, 340:605–612. [CrossRef]

- Packard A: Cephalopods and Fish: The Limits of Convergence. Biological Reviews 1972, 47:241–307. [CrossRef]

- Wodinsky J: Hormonal Inhibition of Feeding and Death in Octopus: Control by Optic Gland Secretion. Science 1977, 198:948–951.

- Wang ZY, Ragsdale CW: Multiple optic gland signaling pathways implicated in octopus maternal behaviors and death. Journal of Experimental Biology 2018, 221:jeb185751. [CrossRef]

- Wells MJ, Wells J: Pituitary Analogue in the Octopus. Nature 1969, 222:293–294. [CrossRef]

- Rocha F, Guerra A, González AF: A review of reproductive strategies in cephalopods. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2001, 76:291–304. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZY, Pergande MR, Ragsdale CW, Cologna SM: Steroid hormones of the octopus self-destruct system. Current Biology 2022, 32:2572-2579.e4. Characterizes the steroid secretions from the optic gland, identifying cholesterol metabolites that are upregulated at the end of life. The findings provide evidence for daf-36 enzyme activity leading to the increased production of 7-DHC in mated octopuses.

- Gerisch B, Rottiers V, Li D, Motola DL, Cummins CL, Lehrach H, Mangelsdorf DJ, Antebi A: A bile acid-like steroid modulates Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan through nuclear receptor signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104:5014–5019. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyama-Yanagawa T, Enya S, Shimada-Niwa Y, Yaguchi S, Haramoto Y, Matsuya T, Shiomi K, Sasakura Y, Takahashi S, Asashima M, et al.: The Conserved Rieske Oxygenase DAF-36/Neverland Is a Novel Cholesterol-metabolizing Enzyme*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286:25756–25762.

- Porter FD: Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet 2008, 16:535–541.

- Ryan AK, Bartlett K, Clayton P, Eaton S, Mills L, Donnai D, Winter RM, Burn J: Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: a variable clinical and biochemical phenotype. Journal of Medical Genetics 1998, 35:558–565. [CrossRef]

- Honegger B, Galic M, Köhler K, Wittwer F, Brogiolo W, Hafen E, Stocker H: Imp-L2, a putative homolog of vertebrate IGF-binding protein 7, counteracts insulin signaling in Drosophila and is essential for starvation resistance. Journal of Biology 2008, 7:10. [CrossRef]

- Bian L, Li F, Chang Q, Liu C, Tan J, Zhang S, Li X, Li M, Sun Y, Xu R, et al.: Comparison of Behavior, Histology and ImpL2 Gene Expression of Octopus sinensis Under Starvation and Senescence Conditions. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Clarevega A, Bilder D: Malignant Drosophila tumors interrupt insulin signaling to induce cachexia-like wasting. Developmental Cell 2015, 33:47–55.

- Kwon Y, Song W, Droujinine IA, Hu Y, Asara JM, Perrimon N: Systemic Organ Wasting Induced by Localized Expression of the Secreted Insulin/IGF Antagonist ImpL2. Developmental Cell 2015, 33:36–46.

- Grearson AG, Dugan A, Sakmar T, Sivitilli DM, Gire DH, Caldwell RL, Niell CM, Dölen G, Wang ZY, Grasse B: The Lesser Pacific Striped Octopus, Octopus chierchiae: An Emerging Laboratory Model. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8. Examines O. chierchiae through its life cycle under laboratory mariculture conditions, providing first detailed descriptions of iteroparous brooding behaviors.

- Rodaniche AF: Iteroparity in the Lesser Pacific Striped Octopus Octopus Chierchiae (Jatta, 1889). Bulletin of Marine Science 1984, 35:99–104.

- Goulson D: Bumblebees: Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation. Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Duchateau MJ, Velthuis HHW: Development and Reproductive Strategies in Bombus Terrestris Colonies. Behaviour 1988, 107:186–207.

- Amsalem E, Grozinger CM, Padilla M, Hefetz A: Chapter Two - The Physiological and Genomic Bases of Bumble Bee Social Behaviour. In Advances in Insect Physiology. Edited by Zayed A, Kent CF. Academic Press; 2015:37–93.

- Princen SA, Van Oystaeyen A, van Zweden JS, Wenseleers T: Worker dominance and reproduction in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris: when does it pay to bare one’s mandibles? Animal Behaviour 2020, 166:41–50.An analysis of the colony-wide effect of the queen and reproductive workers on overall worker reproduction. The authors show that reproduction is controlled largely through dominance of the queen or of dominant workers.

- Shpigler H, Amsalem E, Huang ZY, Cohen M, Siegel AJ, Hefetz A, Bloch G: Gonadotropic and Physiological Functions of Juvenile Hormone in Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) Workers. PLOS ONE 2014, 9:e100650. [CrossRef]

- Krieger GM, Duchateau M-J, Van Doorn A, Ibarra F, Francke W, Ayasse M: Identification of Queen Sex Pheromone Components of the Bumblebee Bombus terrestris. J Chem Ecol 2006, 32:453–471. [CrossRef]

- Amsalem E, Orlova M, Grozinger CM: A conserved class of queen pheromones? Re-evaluating the evidence in bumblebees (Bombus impatiens). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 282:20151800. [CrossRef]

- Röseler P-F, Röseler I, van Honk CGJ: Evidence for inhibition of corpora allata activity in workers ofBombus terrestris by a pheromone from the queen’s mandibular glands. Experientia 1981, 37:348–351. [CrossRef]

- Van Honk CGJ, Velthuis HHW, Röseler P-F, Malotaux ME: THE MANDIBULAR GLANDS OF BOMBUS TERRESTRIS QUEENS AS A SOURCE OF QUEEN PHEROMONES. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1980, 28:191–198. [CrossRef]

- Pandey A, Motro U, Bloch G: Juvenile hormone interacts with multiple factors to modulate aggression and dominance in groups of orphan bumble bee (Bombus terrestris) workers. Hormones and Behavior 2020, 117:104602. Examines the effect of decreased juvenile hormone levels on egg laying, dominance, and aggression in bumblebee workers. In groups of worker bees outside the colony, reduction in juvenile hormone leads to lower aggressiveness, less egg laying, and less dominance. Juvenile hormone reduction does not, however, change existing hierarchies.

- Hefetz A, Grozinger CM: Hormonal Regulation of Behavioral and Phenotypic Plasticity in Bumblebees. In Hormones, Brain and Behavior. . Elsevier; 2017:453–464.

- Bloch G, Borst DW, Huang Z-Y, Robinson GE, Hefetz A: Effects of social conditions on Juvenile Hormone mediated reproductive development in Bombus terrestris workers. Physiological Entomology 1996, 21:257–267. [CrossRef]

- Amsalem E, Hefetz A: The appeasement effect of sterility signaling in dominance contests among Bombus terrestris workers. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2010, 64:1685–1694. [CrossRef]

- Amsalem E, Shamia D, Hefetz A: Aggression or ovarian development as determinants of reproductive dominance in Bombus terrestris: interpretation using a simulation model. Insect Soc 2013, 60:213–222. [CrossRef]

- Bloch G, Hefetz A: Regulation of reproduction by dominant workers in bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) queenright colonies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1999, 45:125–135. [CrossRef]

- Derstine NT, Villar G, Orlova M, Hefetz A, Millar J, Amsalem E: Dufour’s gland analysis reveals caste and physiology specific signals in Bombus impatiens. Sci Rep 2021, 11:2821. Dufour's gland is responsible for pheromone secretions in bumblebees. The authors characterize Dufour's gland secretions, identifying compounds specific to reproductive status.

- Amsalem E, Twele R, Francke W, Hefetz A: Reproductive competition in the bumble-bee Bombus terrestris: do workers advertise sterility? Proc Biol Sci 2009, 276:1295–1304. [CrossRef]

- Carey JR: Longevity minimalists: life table studies of two species of northern Michigan adult mayflies. Experimental Gerontology 2002, 37:567–570. [CrossRef]

- Arnqvist G, Henriksson S: Sexual cannibalism in the fishing spider and a model for the evolution of sexual cannibalism based on genetic constraints. Evolutionary Ecology 1997, 11:255–273. [CrossRef]

- Roggenbuck H, Pekár S, Schneider JM: Sexual cannibalism in the European garden spider Araneus diadematus: the roles of female hunger and mate size dimorphism. Animal Behaviour 2011, 81:749–755. [CrossRef]

- Foellmer MW, Fairbairn DJ: Spontaneous male death during copulation in an orb-weaving spider. Proc R Soc Lond 2003, 270:S183-185. [CrossRef]

- Barry KL, Holwell GI, Herberstein ME: Female praying mantids use sexual cannibalism as a foraging strategy to increase fecundity. Behavioral Ecology 2008, 19:710–715. [CrossRef]

- Burke NW, Holwell GI: Male coercion and female injury in a sexually cannibalistic mantis. Biology Letters 2021, 17:20200811. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).