2. Material And Methods

2.1. Neural Cellular Automaton: A Multi-Agent Model for Morphogenesis, and Aging?

Cellular Automata (CAs) were initially introduced by von Neumann to study self-replicating machines [

62]. Since then, they have become widely used as simple models for Artificial Life [

61]. The core concept behind CAs revolves around maintaining a discrete spatial grid of cells, each individual cell

i being assigned a binary, numerical, or even vector-valued state

at every time step

.

The evolution of these cell states over time follows local update rules. Specifically, we have that , where is a function of the current state of cell i, i.e., , and of the states of its neighboring cells, which we collect in the matrix .

Despite their typically simple and predefined update rules, CAs often exhibit complex dynamics (c.f., Conway’s Game of Life [

66]) and have even been employed for universal computation tasks, as in Wolfram’s rule 110[

63,

64].

Neural Cellular Automata (NCAs) [

67] can be seen as an extension to “traditional” CAs. In this context, the local update rule is replaced with a more flexible ANN,

, where

denotes the set of trainable parameters of the ANN,

(see, e.g., Appendix A in Ref. [

41]). By employing Machine Learning (ML) techniques, NCAs have been utilized to perform tasks such as self-orchestrated pattern formation [

39], the simultaneous co-evolution of a rigid robot’s morphology and controller [

51], and have been proposed as a promising candidate for robust, decentralized controllers of autonomous drug delivery systems [

68].

An NCA is essentially a grid of interconnected cells, each equipped with an identical ANN that is capable of perceiving the numerical states of its immediate cellular neighbors,

, and proposing actions,

, to regulate its own cell state, following the equation

where we also account for possible imperfections in the cell-specific state updates via a Gaussian noise term of amplitude

.

Thus, the cellular agents of an NCA perceive the numerical states of their immediate, respective neighborhoods, , at any given time step, , to update their own states (c.f., fig:introduction:simulation (A, B)). Importantly, we do not include any explicit signature of aging in our model, i.e.,, no cell-internal marker or explicit input to the cellular agents other than their self-regulated cellular states that would contain temporal information.

However, being immersed in a dynamical multi-cellular environment where every part has its own agenda, the cellular agents’ state updates can also be utilized for active communicating with their neighbors, following a policy

. From the perspective of

Reinforcement Learning [

80], an NCA can thus be considered a trainable multi-agent system that needs to utilize local communication rules to achieve a target system-level outcome.

So far, our approach is agnostic to the particular ANN architecture of the update function,

. Closely following Ref. [

41], we here briefly describe the genuine ANN architecture deployed in our cellular agents, which is schematically depicted in fig:introduction:simulation (B): Inspired by Ref. [

81], we partition an NCA’s cell’s ANN into (i) a sensory part,

, preprocessing each neighborhood cell state separately into a respective sensor embedding, which we collect in the matrix

. These sensor embeddings are then (ii) averaged across all neighbor embeddings into a single context vector

. A subsequent (iii) controller ANN,

, potentially with recurrent feedback connections, eventually outputs the cell’s action,

based on the cell-specific context vector

. Notably, for the controller module we here utilize so-termed RGRN architectures [

41] that are inspired by a combination of

Recurrent ANNs (RNNs) [

82] and

Gene Regulatory Networks [

83] (see Appendix A in Ref. [

41] for details).

Analogous to Ref. [

41], we model morphogenesis by employing NCAs on a two-dimensional

square grid with the objective that all cells of the grid assume a cell-specific predefined target cell type,

, after a fixed number of

developmental time steps, starting from an initial cell state configuration

. We assign the first

elements,

, of an NCA’s

-dimensional cell state

as indicators for expressing one of

discrete cell types, while the remaining

elements of the cell state represent its hidden states,

, that can be utilized by the NCA for intercellular communication. A cell’s “type”,

, is now defined as the index,

, of the maximum element of its indicator vector

:

For an NCA to assemble a predefined target pattern of target cell types , we thus need to find a suitable set of NCA parameters that minimizes the deviation of all actual cell types and the desired ones after developmental time steps. Below, we introduce an evolutionary algorithms to evolve suitable sets of NCA parameters that maximize a fitness score based on comparing the “final” cell types of the NCA, , after the developmental stage to the predefined target cell types . In this context, the NCA parameters thus correspond to the virtual organism’s genotype, while the grid of final cell types represent the system-level phenotype that is seen by the selection mechanism of the evolutionary process (c.f., fig:introduction:simulation (C)).

2.2. Neuroevolution of NCAs: An Evolutionary Algorithm Approach to Morphogenesis

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are heuristic optimization techniques designed to maintain and optimize a set, or population,

, comprising parameters or individuals,

, over successive generations in order to maximize an objective function or fitness score,

. Drawing inspiration from the principles of natural selection and biological life’s DNA-based reproduction mechanisms, EAs (i) predominantly select high-fitness individuals for reproduction, and utilize (ii) crossover and (iii) mutation operations to generate new offspring by (ii) merging the genomic material of two high-quality individuals from the current population,

, and (iii) occasionally mutating offspring genomes,

by adding typically Gaussian noise to the parameters; the ⨁ symbol signifies a genuine merging operation of two genomes, which may vary according to the specific EA implementation. Thus, populations of individuals are directed towards high-fitness regions within the parameter space

, typically across numerous generations of successive selection and reproduction cycles (i)-(iii) [

41].

Closely following our previous work [

41], and in contrast to many “traditional” EA use-cases, we here explicitly distinguish between the genotypic parameters,

, and the corresponding phenotypic realizations,

. More specifically, we utilize NCAs (c.f., sec:methods:nca) to model the biologically inspired developmental layer [

19] in between genotypes and phenotypes,

, akin to the process of morphogenesis: Here, a genotype,

, corresponds to a particular realization

j of an NCA’s parameters, comprising the set of initial cell states

and the corresponding ANN parameters

, such that

where we explicitly distinguish between structural (S) and functional (F) genes. We then employ eq:nca-update for

developmental steps to successively transform the NCA’s cell states from an initial state into a “final” set of cell types

on the NCA’s grid. This mature phenotype,

represents a two-dimensional tissue of cells, and is the input to the fitness score based on which the EA selects: As illustrated in fig:introduction:simulation (C), we here optimize for a fitness score in the phenotype- rather than genotype space,

, while still performing genetic recombination and mutation in the genotype space.

Let’s recall: our goal is to achieve morphogenesis of a two-dimensional spatial tissue of cell types,

, that optimally resembles a predefined target pattern,

, of a total of

cells on an

square grid of an NCA. Moreover, we aim to derive a virtual organism with this capability by modeling a biologically inspired evolutionary process with EAs to evolve a suitable set of NCA parameters (c.f., fig:introduction:simulation (C)). Thus, we introduce our phenotype-based fitness score,

, as [

41]

where

counts the number of correctly assumed cell types after

developmental steps (where

),

counts the number of developmental steps at which the target pattern is realized entirely (whenever

for all

i), and

counts pairs of successive time steps,

, without cell type updates in the entire tissue (where

for all

i).

Thus, we design an evolutionary process that primarily selects for NCAs that assume the correct cell type pattern after (precisely) developmental steps and reinforces NCAs (by a factor of in the fitness score) that prematurely achieve and maintain the target pattern. To avoid developmental stagnation and increase the EA’s performance, we specifically discount the fitness score of NCAs with static behavior by . A fitness score of indicates that the problem is solved.

Although the above framework [

41] can be utilized in conjunction with any black-box evolutionary or genetic algorithm, we found the well-established Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolutionary Strategy (CMA-ES) [

75] to be a viable choice for our purposes.

2.3. Information-Theoretic Analysis: Active Information Storage, Transfer Entropy and Spatial Entropy on the NCA

Information theory [

84] offers valuable insights into the dynamics of complex systems. In order to understand the NCA’s information dynamics during aging, we used three key information-theoretic metrics to examine the information dynamics: active information storage [

77], transfer entropy [

78], and the spatial entropy.

Active Information Storage (AIS) quantifies the amount of information from an agent’s past that is pertinent to predicting its future state. Specifically, AIS refers to the portion of stored information currently utilized for determining the agent’s next state [

77]. Mathematically, the AIS of an agent

Q is expressed as the local mutual information between its semi-infinite past

as

and its next state

at time step

:

Here, is an approximation with history length k. The time-averaged value, weighted by the distribution of , is denoted as . In our study, we calculated the local AIS across the states of the cells.

Transfer Entropy (TE) measures the information transferred from a source agent to a destination agent that is not contained in the past of the destination agent. We employed the local TE concept introduced by Lizier [

77]. The local TE from a source agent

Z to a destination agent

Q is defined as the local mutual information between the previous state of the source

and the next state of the destination agent

, conditioned on the semi-infinite past of the destination

(as

):

The transfer entropy is the local TE averaged over time, denoted as , where is an approximation with history length k. Unlike mutual information, which measures static correlation, transfer entropy captures the dynamic, directional flow of information within the agent network.

Spatial Entropy (SE) measures the randomness or disorder within a spatial distribution of states. It provides insight into the complexity of spatial patterns in a system, such as an NCA with multiple states. In our study, we compute SE by evaluating the entropy of the distribution of cell states across the grid at each time step. Formally, the spatial entropy

H at time step

n is defined as:

where

S is the set of possible states, and

is the probability of state

s occurring in the grid at time step

n. This measure provides an indication of the level of unpredictability or complexity in the spatial arrangement of cell states. In this article, we calculate the spatial entropy for the states of the NCA across different time steps.

3. System

Following our previous study [

41], we utilize EAs to evolve NCAs to perform morphogenesis tasks. Each cell in our NCA implementation is equipped with a gene regulatory network-inspired recurrent ANN, conceptually substituting the intricate internal decision-making competencies of biological cells (see fig:introduction:simulation (B) for a visualization and Appendix A in [

41] for numerical details). In other words, each cell in the NCA is equipped with an information processing pipeline that transforms sensory input of its local environment in the NCA’s grid into control instructions to regularize its own cell type. If done in a coordinated way, these local individual cell-state updates guide the formation of a mature system-level phenotype - in our case of a target tissue - over successive developmental steps.

More specifically, we utilize

cells on an NCA with fixed boundary conditions (see sec:methods:nca and Appendix C in Ref. [

41]) and train it analogously to [

41] via evolutionary algorithms (see sec:methods:ea) to perform morphogenesis -

i.e.,, self-orchestrated tissue growth - of a

smiley-face pattern in a predefined number of

developmental steps (see fig:introduction:simulation (C) for an illustration of the evolutionary process).

The target tissue consists of

distinct cell types: one cell type for the background cells, one for the face cells, and a single cell type for the facial organs,

i.e.,., for the eyes and the mouth (c.f., blue-, magenta-, and white-colored cells in fig:introduction:simulation (A)). Moreover, we allow the NCA to utilize

hidden channel of its

cell state channels for unconstrained intercellular communication. In cell-state updates, given by eq:nca-update, we utilize a noise level of

, limit the numerical value of the proposed action

to

, and clip the cell-states post-update

to

(see Appendix C and Ref. [

41] for more details on our NCA implementation).

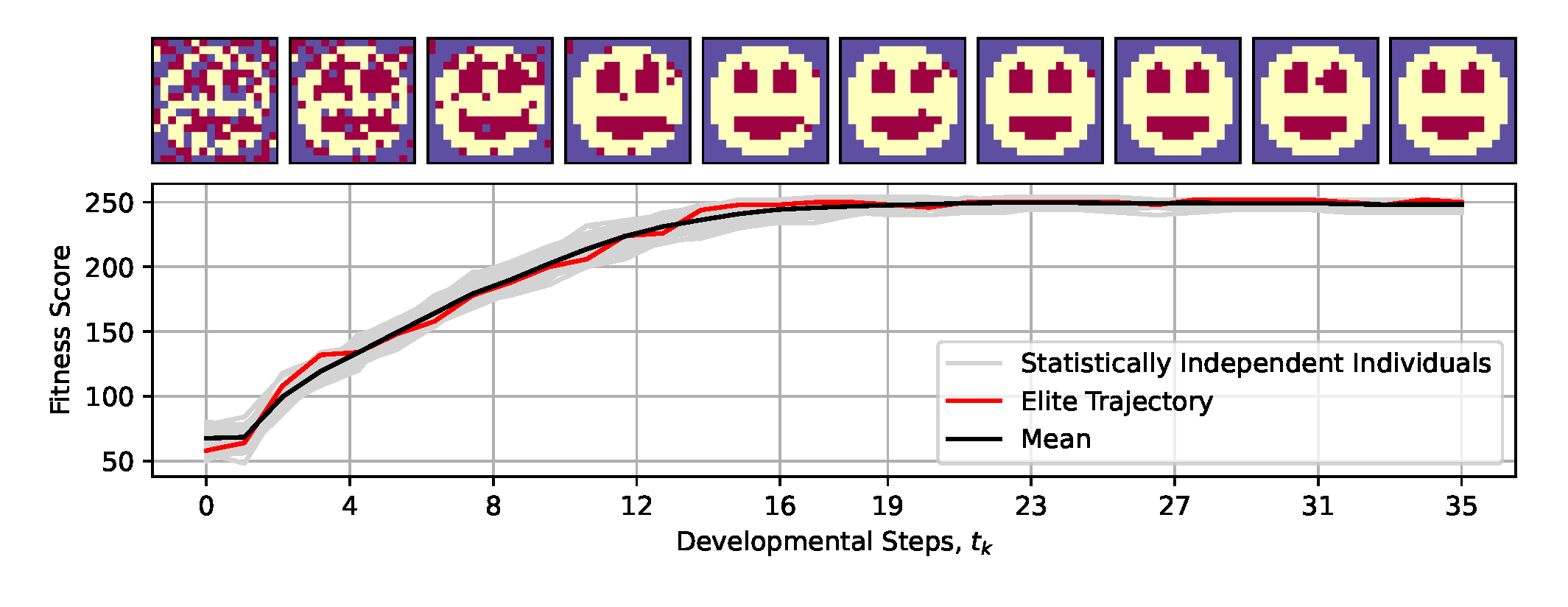

Our NCAs transform an embryonic genotype, , into a mature phenotype, , and we here quantify an NCA’s performance by evaluating the corresponding fitness score, , defined by eq:fitness with respect to the smiley-face pattern over the NCA’s entire life-span of developmental steps. As illustrated in fig:system:morphogenesis, a successfully evolved NCA maximizes the fitness score to , exhibiting correctly expressed cell types after time steps, then maintaining the target pattern until (see sec:methods:ea for details on the evolutionary process).

Notably, the cellular agents do not perceive any information about the current nor the final fitness score of their corresponding NCA. The fitness score is only utilized by the EA to optimize the NCA’s parameters over evolutionary time-scales. Moreover, there is no contribution neither to the fitness score nor to the NCA’s ANN sensory inputs that would provide the system with explicit temporal information indicating the “age” of any part of the virtual organism, or even a notion of “time” in general. Thus, the self-orchestrated pattern formation of the here - and previously [

41] - investigated NCAs is fully driven via emergent,

i.e.,, evolved, intercellular communication rules and intracellular decision-making.

4. Computational Results

4.1. Aging as a Loss of Goal-Directedness: Organism Learned Development During Evolution, Not to Maintain Anatomical Homeostasis After Development

We aimed to assess whether the self-regulatory behavior of biological systems that drive morphogenesis induces aging-like phenomena at long time-frames. To this end, we use NCAs evolved in silico to model the process of morphogenesis and then deploy their self-regulatory dynamics for much longer times compared to the reproduction stage during evolution (i.e., when selected for reproduction). We monitor and analyze the NCAs morphological integrity throughout their lifetimes and compare such long-term morphological trajectories with biological aging. The evolutionary process described in sec:methods:ea,sec:system explicitly selects for optimal fitness scores after developmental steps, which corresponds to the fertility age of real-world organisms. However, this implies that the behavior of an NCA with a potentially much longer lifetime of , and particularly , is not subject to selection and may fundamentally be considered ill-defined or ambiguous.

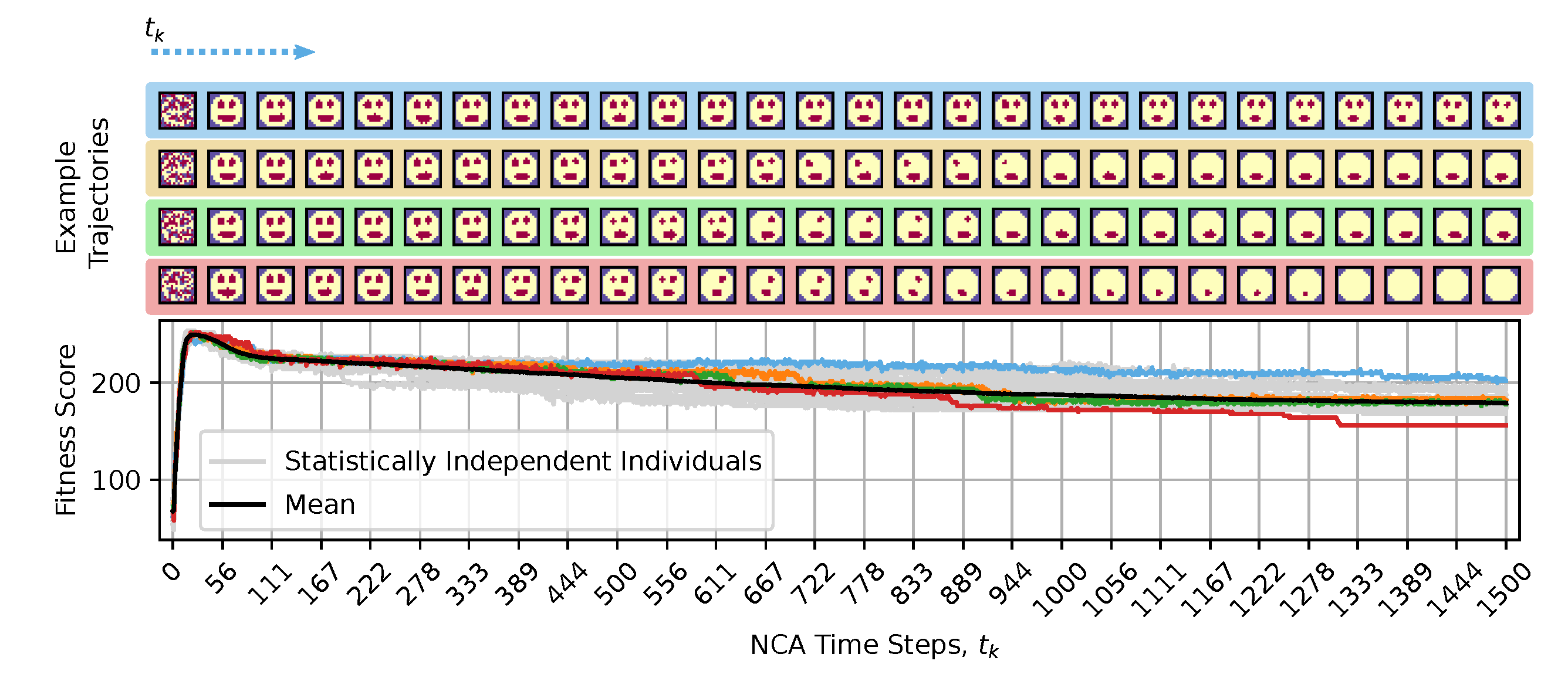

To demonstrate this, we deploy the NCA solution that has been evolved to self-assemble a smiley-face pattern during a morphogenesis phase of developmental steps (c.f., fig:system:morphogenesis) for a much longer lifetime of up to time steps, notably without any further optimization considering the extended lifetime. From the results presented in fig:result:pleiotropy, we learn that after an initial rapid rise in the fitness score during the developmental phase, the NCA’s long-term fitness score gradually declines, primarily due to the loss of different internal organs such as a single or both eyes and, occasionally, the mouth. Moreover, this is not only a feature of the particular NCA demonstrated here, but is a systematic phenomenon of the presented framework.

Thus, we argue that the biologically-ubiquitous self-regulatory behavior of a substrate’s agential parts may induce system-level dynamics that resemble the process of biological aging if applied on timescales that exceed development. The organisms learned during evolution with development as the primary goal; once they reached that goal, we observed that they don’t regenerate by themselves and slowly show signs of morphological deterioration, e.g., aging. In this sense, aging can be seen primarily as a loss of goal-directedness, the goal of development being different from the goal of maintenance of the anatomy over timescales exceeding development. This view on aging is related to programmatic theories of aging like antagonistic pleiotropy or hyperfunction theory [

10,

14,

15] that state that what is good for development could ultimately cause aging. In our framework, the lack of goal-directedness after development may cause some informational antagonistic pleiotropy (or hyperfunction) as cells lose their developmental policy after reaching the target morphology but it is broader in scope as giving a new goal to the cellular collective like regeneration and therefore by reactivating developmental pathways may cure aging (see regenerative experiments below).

4.2. Impact of Defects of Cellular Information Processing at Different Levels on the Rate of Aging in a Multi-Scale Competency Architecture

To determine how the perception-action cycles of the unicellular agents of a collective multi-cellular organism influence, at least in part, the rate of morphological decline, we here investigate the effects of an NCA’s system parameters on its long-term morphological integrity. Based on the NCA system defined in section III, we identify four key mechanisms involved in the corresponding uni-cellular perception-action cycles affecting morphological integrity, namely cell-specific differentiation reliablility (a), reliable state updates (b), reliable communication between neighbors (c), and persistent genetic encoding (d). Our framework allows us to selectively control these corresponding processes (a-d) and explicitly corrupt them independently over the lifetime of the virtual organism. Thereby we demonstrate the severe effects of these processes on the rate of morphological aging.

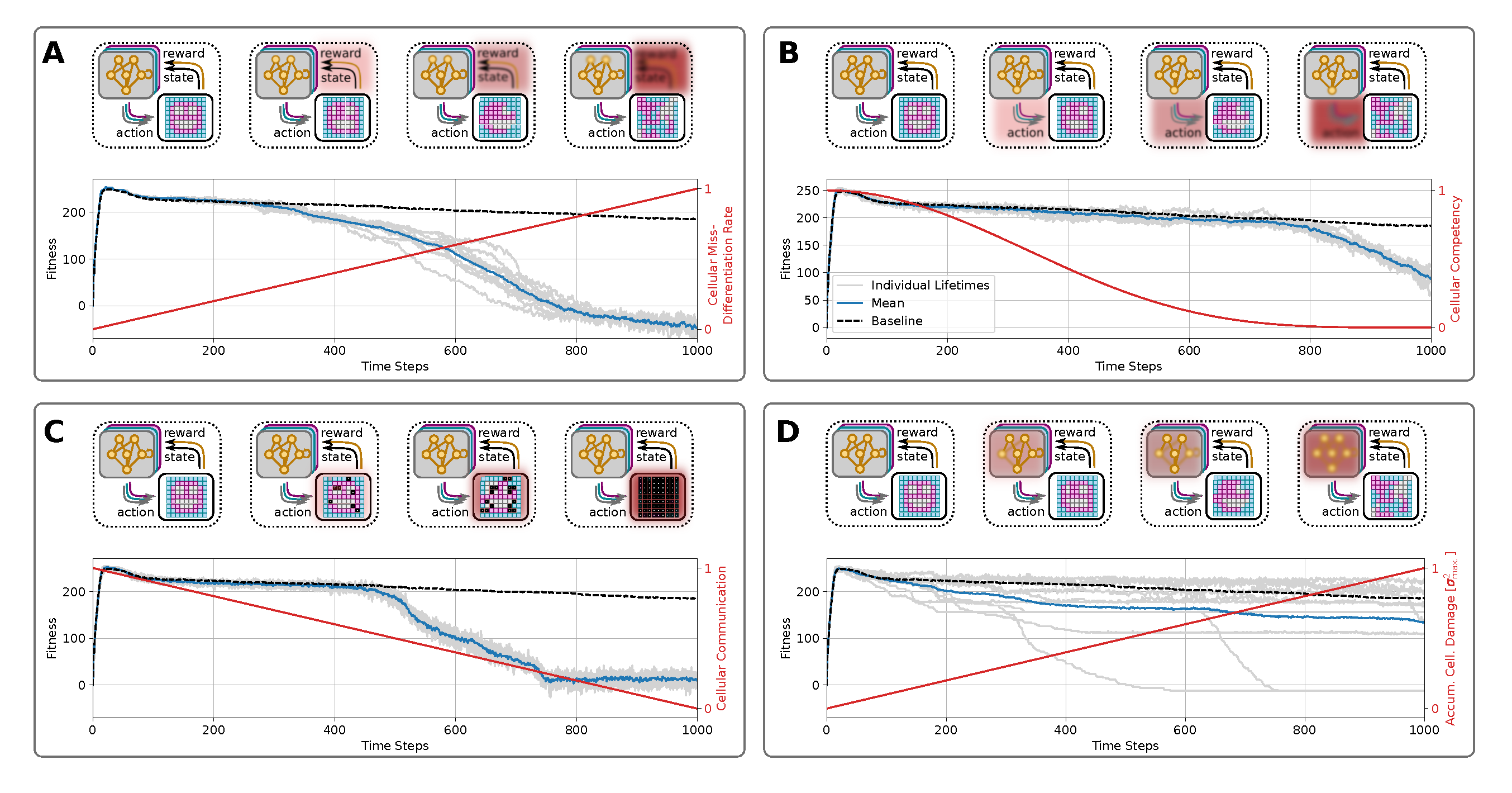

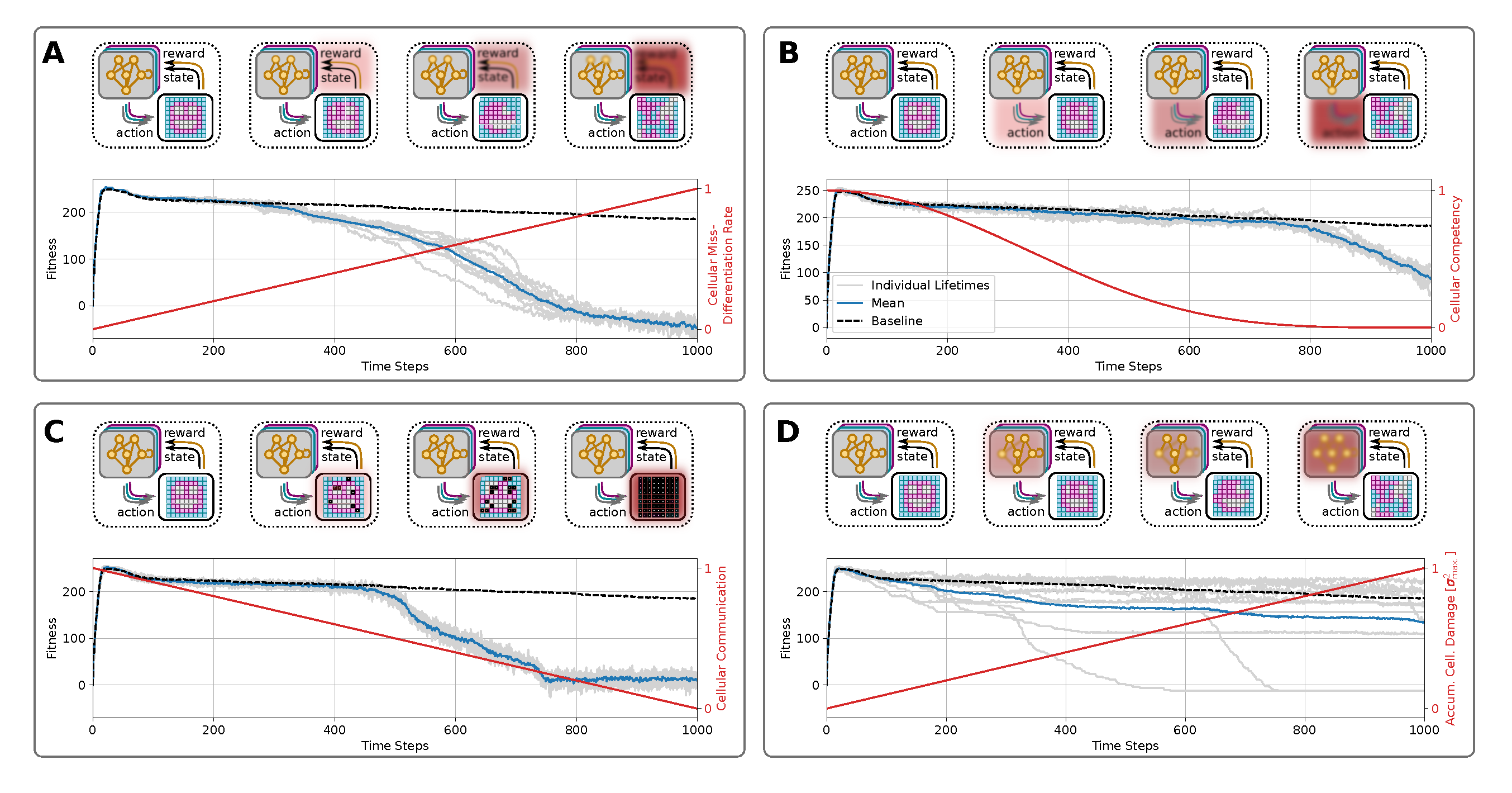

In the following sections, we therefore study the factors accelerating aging, not the cause of aging per se that we see primarily as a loss of goal-directedness. We introduce these known aging mechanisms (i-iv), respectively, based on and deployed to the biologically motivated unicellular competencies in our NCA system. We then demonstrate and discuss the corresponding implications on enhanced rates of morphological aging in long-term simulations of such virtual organisms. We illustrate the respective results in a compact form in fig:results:schedules(A-D), and continue below with an information-theoretic analysis of these processes.

4.2.1. Cellular Differentiation

One critical parameter in our system is the noise level

utilized to corrupt the NCA’s update step given by eq:nca-update. While a moderate noise level can help an evolutionary process to identify robust NCA parameters that solve a specific morphogenesis task, chosen too low, the evolutionary process will in our case most likely identify a direct encoding of the target pattern, largely neglecting cellular competencies in the pattern formation task [

41]. In turn, a too-large noise level will not only prevent the evolutionary process from finding a good solution to the morphogenesis task but, in general, drastically limit the cell specification capacities of the NCA’s cell states. Therefore, noisy cell state updates in our system could be seen as the accumulation of misdifferentiated cells, ultimately corrupting the state perceptions of neighboring cells on the NCA creating a default of cellular communication (a hallmark of aging) similarly to [

6,

85]. This mechanism accelerates aging but is not a cause per se.

We argue that an increasing noise level over the lifetime of such an NCA-akin organism successively affects its morphological integrity. To demonstrate this, we thus utilize the pre-evolved NCA from above (c.f., fig:system:morphogenesis,fig:result:pleiotropy) and deploy it for an extended lifetime of timesteps while successively increasing the noise level linearly from to . The results depicted in fig:results:schedules (A) show that while the correspondingly affected virtual organisms initially follow their unaffected cousins (c.f., fig:system:morphogenesis,fig:result:pleiotropy and black-dashed line in fig:results:schedules (A)), after a particular duration (specific to the particular NCA solution and noise schedule ) the fitness score rapidly drops at , emphasizing an enhanced rate of degradation of the target tissue compared to the baseline with constant noise .

Noise influences the dynamical cell states in our NCA experiments. These states are the inputs and outputs of the virtual tissues’ ANN augmented cells, and represent dynamic variables of the self-regulatory NCA dynamics, with attractor states or instabilities. We thus interpret the effect discussed here as cellular misdifferentation-enhanced morphological aging. Understanding such “run-away” arguments in the “biological software” of cell state expressions, or instabilities in the context of competent tissues seems central to understanding aging.

4.2.2. Cellular Competency

Next, we directly manipulate the cellular decision-making competency - the reliability with which uni-cellular agents can regulate their own cell states within a tissue (e.g., regulative development and regenerative tissue allostasis). Here, we investigate whether degrading unicellular competencies throughout the lifetime of an organism enhances morphological aging: while young, healthy cells are highly reliable in their (re)actions to external perturbations, especially during development, the reliability of such cell decisions might be strongly affected over the lifetime of an organism, inducing morphological decline. To this end, and following 6, we define the decision-making as a probability at which proposed actions of unicellular agents are actually forwarded to the environment at a given time step. More specifically, at every instance in time we draw a uniform random number for every cell in the tissue. Only if we consider the cell’s action in the NCA’s update step, described by eq:nca-update, and omit it otherwise by setting . In that way, we can scale the average reliability of decision-making of all cells in the tissue, i.e.,, while corresponds to fully reliable decision-making of every cell at every time step, parameterizes fully passive cells which can’t make decisions at all.

Here, we utilize as decreasing cellular competency by transforming to in time steps following the functional form (see fig:results:schedules (B)). This increasingly corrupts cellular competencies by successively decreasing the reliability at which every unicellular agent in the grid can regularize, and thus “correct” their states against noise or faulty cell state configurations.

The results of fig:results:schedules (B) reveal that the fitness score of NCAs whose cellular competencies are gradually affected remains similar to the baseline fitness scores of the unperturbed case (c.f., fig:system:morphogenesis,fig:result:pleiotropy). But eventually, at , the small but finite noise of used in our simulations leads to accumulated damage in the NCA’s states that is catastrophic for its morphological integrity, thus destroying the target morphology via diffusive processes.

Thus, decreasing cellular decision-making competencies in a noisy collective organism necessarily lead to morphological aging effects, caused by unreliability in the “biological cell-state reconfiguration software”. However, the rate at which these decreasing cellular competencies lead to significant aging effects is an intricate interplay between the actual noise in the system and the robustness of the unicellular agents to persist against accumulating noise in their respective state configurations.

4.2.3. Cell-Cell Communication

Another necessary feature of systems with decentralized collective decision-making is reliable communication between agents. Similar to biological tissue, the cells of an NCA are integrated into a lattice of functionally homogeneous cells that only diverge in their respective cell state history. However, their neighbor coordination typically remains fixed [

39,

41,

67]. Here, we specifically manipulate the connectivity between the unicellular agents in the NCA’s grid by blocking increasingly many communication channels between neighboring cells as time proceeds. This approach is biologically motivated by cells closing their gap junctions (GJs) to their neighbors, which is known in vivo to shift cells from cooperatively working on large morphogenetic setpoints (organ maintenance) toward individual goals appropriate to unicellular organisms such as proliferation and migration [

50,

86,

87,

88]. It is also related to altered cell-cell communication found during aging [

6]. Indeed, aging involves deficiencies in neural, neuroendocrine, and hormonal signaling pathways [

89] as well as the alterations in the bidirectional communication between human genome and microbiome. Chronic inflammation is also part of this altered cellular communication [

6].

We achieve this technically by omitting the corresponding input state

of a blocked connection, or GJ from cell

j to cell

i (see fig:introduction:simulation (B)). More specifically, we utilize a probability

which defines the fraction of GJs that should remain open for each cell in the tissue at a given time

. In turn, if for a particular cell

i, the fraction of connections to its neighbors exceeds

at time

, we henceforth randomly block another one of its

still connected GJs (once closed, GJs remain closed in our case); see sec:methods:nca and [

41] for more details on our definition of cellular neighborhoods.

By linearly transforming to , we successively isolate the unicellular agents from their host tissue by blocking an increasing number of their GJs until, eventually at time , all cells are effectively isolated from their surroundings. In fig:results:schedules (C) we demonstrate the effects of this approach: Again, the self-orchestrated morphogenetic program can withstand the effects of increasingly corrupted competencies for a surprisingly long time. However, at , corresponding to and thus half the GJs of every cell being closed, the effects of the removed communication channels can be observed by a resulting rapid drop in the phenotypical fitness scores caused by a rapid degradation of the target pattern.

Thus, decreasing the ability of cells to communicate with their neighbors leads to enhanced effects of morphological aging if a threshold of GJs is closed.

4.2.4. Accumulation of Genetic Damage

Another potential source for self-induced aging is accumulating damage to the cells’ genetic material via successive mutations of the functional genome over the lifetime of the virtual organism: To this end, we utilize the pre-evolved NCA solution discussed above (c.f., fig:system:morphogenesis,fig:result:pleiotropy), but at every time step , we successively manipulate the cells’ ANN parameters throughout their lifetime. This directly introduces accumulating genetic mutations to the self-regulatory mechanisms of the NCA, causes potential dysfunctional decision-making behavior at the uni-cellular level, and correspondingly leads to enhanced morphological decline. More specifically, we add zero-centered normal distributed noise of standard deviation to the functional genes of the NCA, , where . The mutated functional genes are then mapped to the ANN parameters of the unicellular agents’ controllers at every time step , thus directly affecting the intracellular decision-making machinery of the NCA.

From the results depicted in fig:results:schedules (D) we can learn several things: First, the evolved NCA solutions seem incredibly brittle against accumulating genetic damage in the ANN parameters, which is reflected by the fact that most of the deployed simulations (with statistically independent mutations) retain high-fitness target patterns for the entire simulated lifetime of the NCA of timesteps. Second, and in contrast to sec:results:induced-degeneracy:noise,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:competency,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:cell-communication this leads to large qualitative deviations in individual behavior of an ensemble of statistical independently mutated NCA solutions: some solutions die off early and obtain vanishing fitness scores, others degrade rather continuously with a spread-out fitness score of , and many solutions still maintain their integrity although accumulating significant genetic damage of in total.

Thus third, while many mutations appear neutral in our framework, critical mutations to specific genes might induce detrimental modifications to the behavior of the unicellular agents (if they occur at the “correct” moment), typically causing a rapid degradation of the target pattern of the affected NCA as reflected by significant drops in the fitness scores of the corresponding virtual tissue. Notably, due to technical reasons, we mutate the functional genome of every agent homogeneously, thus retaining a functionally homogeneous distributed decision-making in the NCA, which nevertheless deviates functionally from the baseline at . Potentially intriguing effects based on heterogeneous mutations, and thus heterogeneous agents in the NCA are out of the scope of this work, and we leave a more thorough investigation to a further contribution.

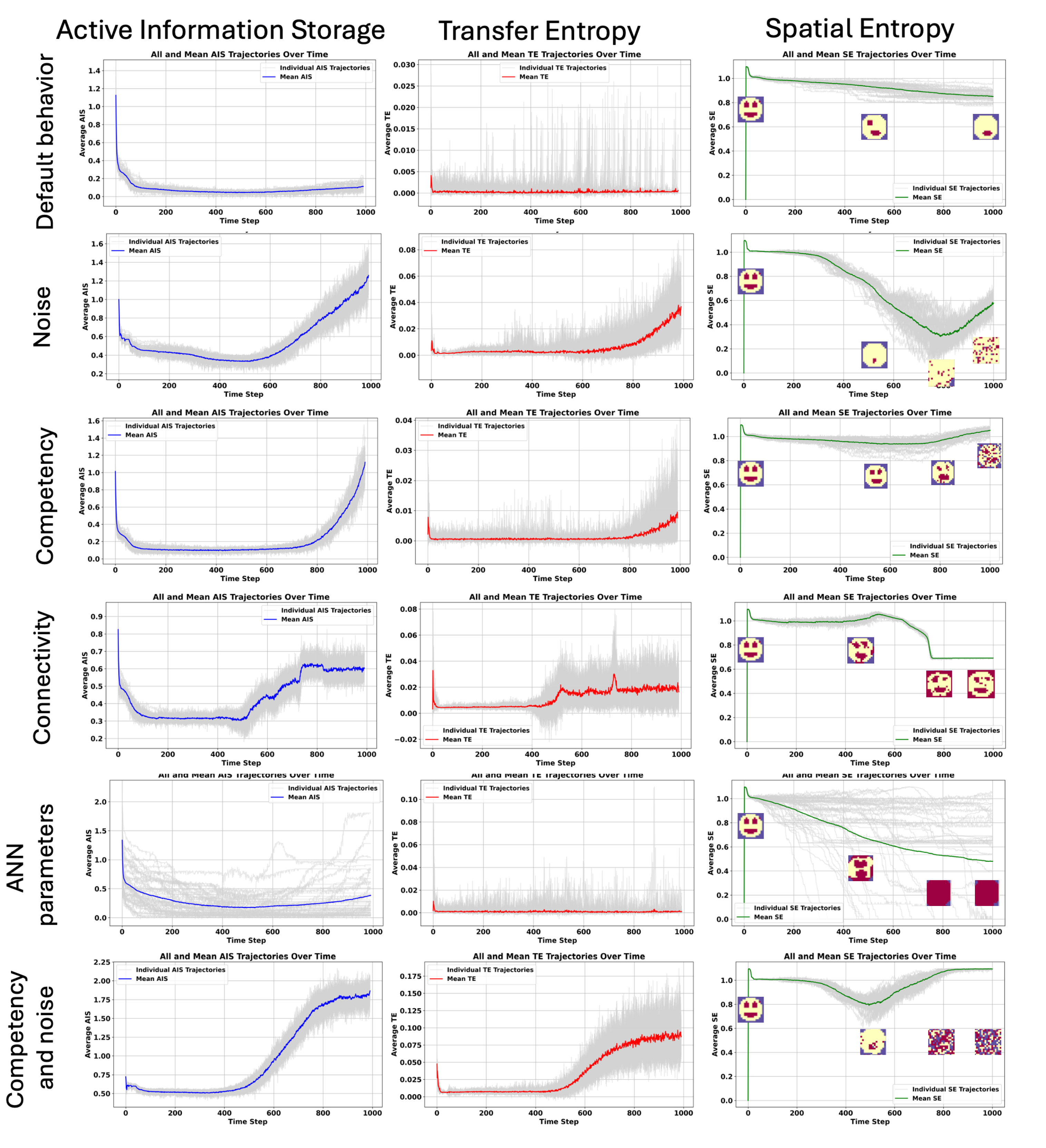

4.3. The Acceleration of Aging Is Linked to Increase in AIS and TE, While Spatial Entropy Revealed Two Different Kind of Aging: Loss of Structure and Proliferation, and Accumulation of Morphological Noise

In order to understand the information dynamics of aging and the cellular information processing in a competent tissue, we applied information-theoretic measures such as (i)

Active Information Storage (AIS), and

Transfer Entropy (TE) and the Spatial Entropy (SE), e.g., the entropy applied to the states of the organism. (see

Figure 6).

We observed in the default behavior case, without any add of the noise or induced loss of competency that both the mean AIS and TE are decreasing during development and aging. For some organisms, we can see that TE can increase during aging, indicating episodes of regeneration in the sense that the morphology is impaired and the organisms try to recover. As we can observe it, the spatial entropy is slowly decreasing during aging, and the anatomy is slowly impaired, with the loss of organs like eyes (see

Figure 6).

Interestingly, we observe that for the cases where we increase noise, see sec:results:induced-degeneracy:noise, there is a threshold value for increasing the noise level after which a rapid decline in fitness occurs - which we interpret as rapid aging-/dying. Indeed, at the same moment, the SE is decreasing, showing a complete disappearance of the anatomy towards a quasi-random distribution of the states. In this case, the AIS and TE increase around 600 steps, a bit more of half-life. A high TE can be interpreted as a high entropy of actions, the cells trying to act after the decline and disappearance of the anatomy.

However, the loss of competency of the cells does not impact the AIS and TE immediately as in the noise case. It is delayed and is starting to have a lot of random states in the anatomy with an increase of the AIS and TE at the end of the lifespan of the organism . But when noise increases and loss of competency are associated the increase in AIS and TE during aging is higher than in the case when only noise is added. Maybe, the loss of competency alters the capacity of the cells to understand the decline of the anatomy and their potentials to counteract it. Noise in the other hand clearly creates a lot of cellular actions during lifespan.

When the connectivity of the cells is altered, from 500 steps, we can observe an increase in AIS and more variability on TE (decrease and increase during aging). By closing the gap junctions, the cells are not receiving information from their neighbors gradually, increasing the uncertainty about their actions. We can see with the SE that the cells can counteract the loss of connectivity until 500 steps until an important decrease in spatial entropy and a complete inversion of the states of the anatomy.

The case that is creating the highest variability in anatomical outcome is the one where we altered the ANN parameters. AIS decreases and then increases over time slightly, TE is close to 0 after development and SE shows different types of aging, a loss of structure (organs) and proliferation of a specific states in the tissue (cancer), and a random activation of cell states.

We can conclude that if the states of the organisms do not change over time, if the anatomy reached a steady state, the AIS and TE are low. AIS is low because there is no new information to be gained from observing past states—future states are always the same and known, independent of the past. Essentially, the predictability is absolute, but since the system does not utilize past information to determine this (the state is intrinsically static), the AIS has low values. This indicates that in a non-changing system there is no information flow necessary between past and future states. The future state is always known (it’s the same as the current state), and thus, the storage of information from past states is irrelevant for future predictions. However, when AIS increases, it is associated to an increase in TE too. It happens in the cases of catastrophic changes in the morphology, as related to changes in spatial entropy. This important change implies an important information flow between cells, possibly representing the cellular attempts to recover from the high morphological changes. The absence of information flow in the default behavior can indicate that the systems considered that it reached its goal, e.g., development and morphostasis is not one of its goal, leading to a steady decrease of the anatomy, or in other words, aging. SE measures the entropy of the grid states. When SE is very high it corresponds to a random distribution of the states over the tissue. This random distribution can be found mainly in the cases of the loss of competency, noise and when both perturbations of associated. SE reveals also a different kind of aging corresponding to a loss of structure, with the loss of specific organs or the proliferation of a specific states in the tissue, like in the loss of connectivity and ANN parameters cases, meaning that the different perturbations lead to different kind of morphological degradation.

4.4. Regeneration as the Cure for Aging?

4.4.1. Loss of Organs Does Not Imply the Loss of Information About the Organ

In biological systems, certain cells or tissues retain “memories” of past states, influencing future behaviors. For instance, epigenetic memory in cells allows them to “remember” previous environmental exposures or developmental cues. Even if the external trigger is removed, cells can maintain certain gene expression patterns or epigenetic marks [

90]. Similarly, tissues may retain information about past structural organization. For example, some amphibians can regenerate limbs or eyes after they are entirely removed [

91,

92,

93]. Planarian flatworms exhibit a kind of holographic memory where, upon cutting into many pieces, each fragment of the animal regenerates everything that is missing to create a perfect and complete copy [

94,

95]. This persistence of information about the system’s target morphology, which serves as the setpoint for the process of anatomical homeostasis, can be implemented in a variety of biochemical, bioelectrical, and biomechanical information, thus it is important to study this important question.

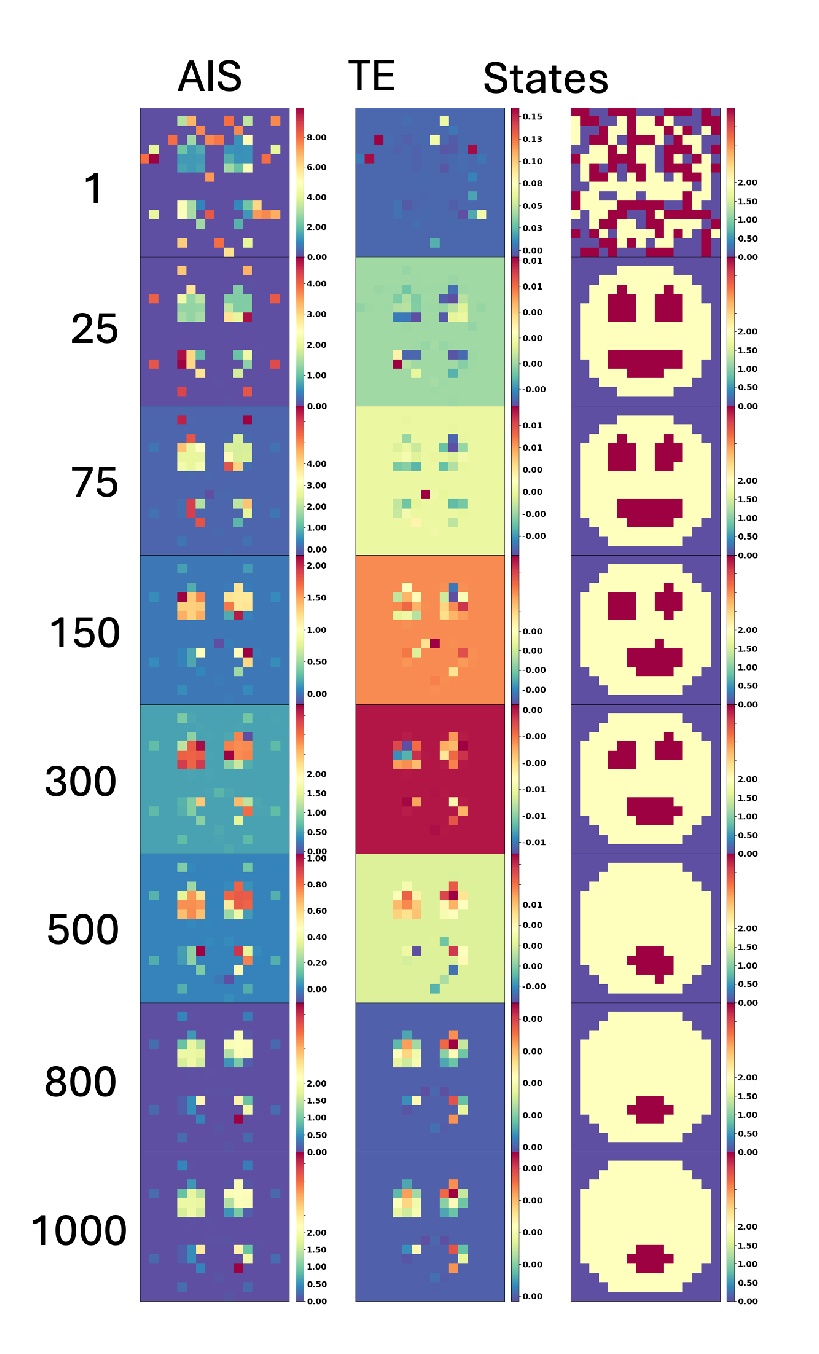

In order to analyze the information dynamics during loss of organs, we computed the spatial AIS and TE (see

Figure 7). We observed that the loss of the eyes during aging does not imply the loss of the AIS at the location of the eye as we can see at step 800 of

Figure 7. The AIS is high and located at the position of the eyes in 100% of the cases. This suggests a memory retention in the system. For example, high AIS values at the “eye” locations in our system parallels the prepattern of the developing amphibian face consisting of regions of specialized cellular resting potential that determine the organs [

96]. Even after visible features are lost, underlying patterns (like bioelectric signals or AIS) can persist, reflecting the system’s inherent memory of structure. AIS measures how much information about the past states is retained in a system over time. This retention can create a lingering effect, where regions that previously had distinct structures (like the eyes) continue to show high AIS values. Even if the explicit structure is no longer present (e.g., the “eyes” disappear in the smiley face), the underlying system dynamics may still carry information related to those past configurations. This residual AIS indicates that the system “remembers” these regions as important parts of its past structure, maintaining high information storage due to the prior role they played.

We conclude that the loss of organs does not imply the loss of information about the organ (see example

Figure 7). Following this result we decided to explore the implications for rejuvenation by inducing the regeneration of the organs in the system in the next section.

4.4.2. Implication for Rejuvenation: A Simulated Experiment of Organ Restoration

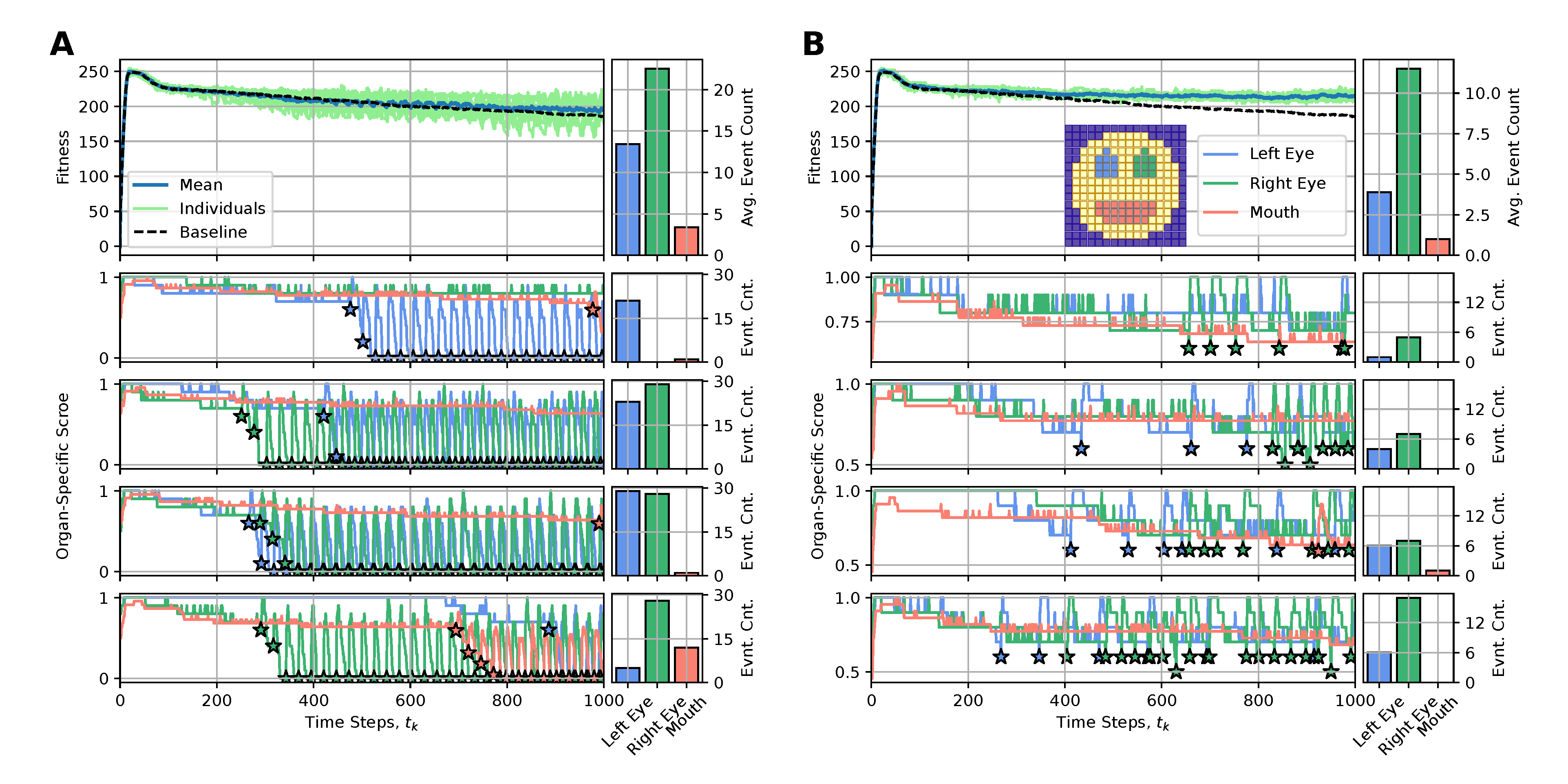

The main reason for the long-term fitness degradation in our experiments - as discussed in sec:results:antagonist-pleiotropy, i.e.,, even without artificially affected cellular competencies - is the loss of specific internal organs, such as the eyes or the mouth. Thus, we here aim to correspondingly counteract the loss of detrimentally affected organs by replacing either the entire organ or specifically reconfiguring the affected cells of the NCA with “regenerative” state information (also erasing their internal working memory by resetting their RNN state information, see appendices A and B for details).

To achieve this, we define an organ-specific score function, , that quantifies for every time-step the fraction of correctly expressed target cells out of the total number of target cells of a specific organ, (c.f., blue, green, and red cells in the snapshot of the smiley-face pattern NCA in fig:results:restoration:organ, respectively). Whenever an organ’s score falls below a predefined threshold value of , we perform an intervention to the affected organ, aiming at restoring its morphology locally. To interfere as little as possible with the NCA’s inherent developmental program, we propose utilizing the initial cell states as the regenerative state information of affected cells, (c.f., sec:methods:nca). This corresponds to reconfiguring the affected cells to their initial (primordial) state at the onset of the developmental program of the NCA .

4.4.3. Less Is More: Organ Restoration Induction by Injecting the Regenerative Information Only to Incorrectly-Positioned Cells

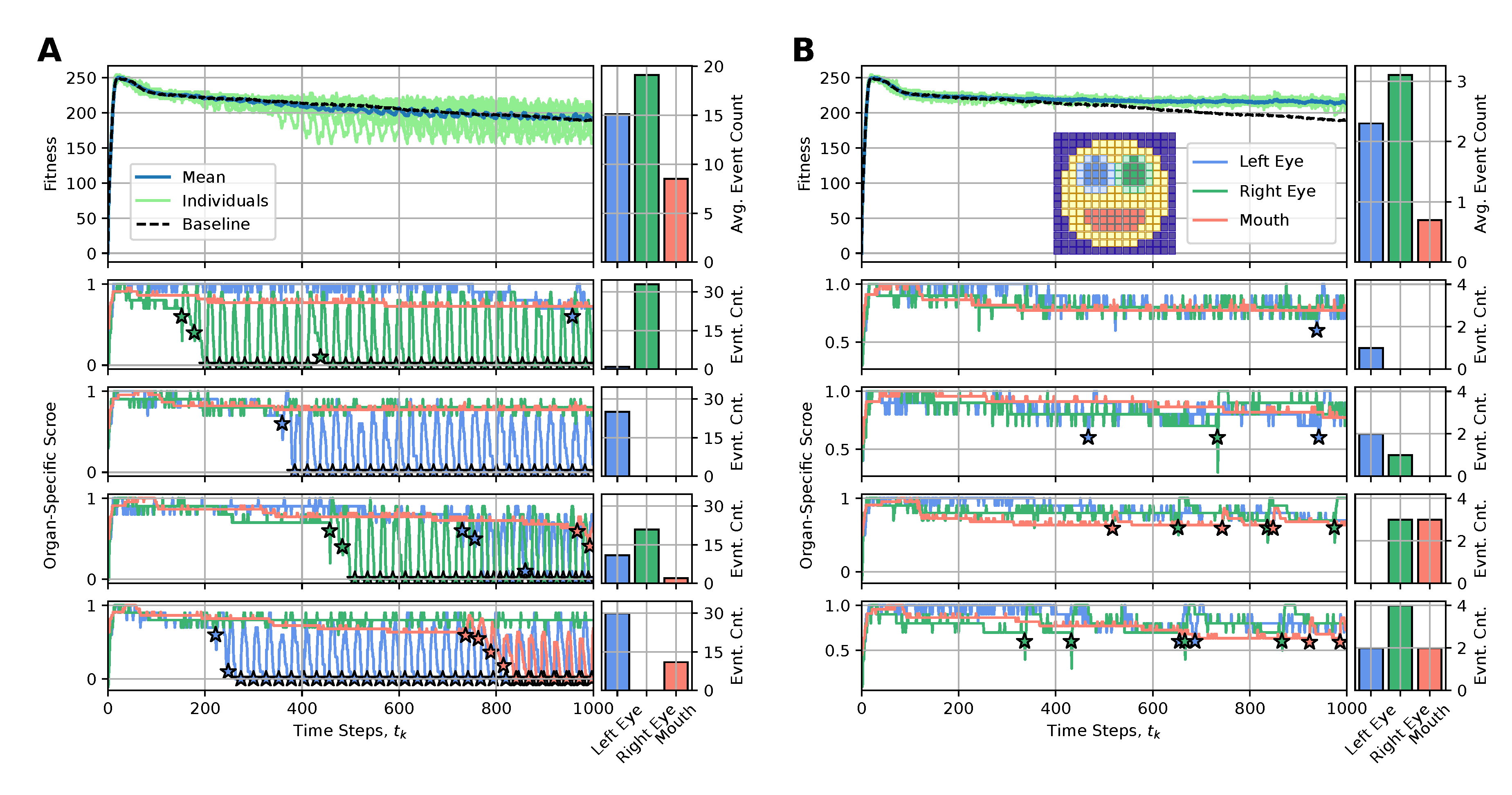

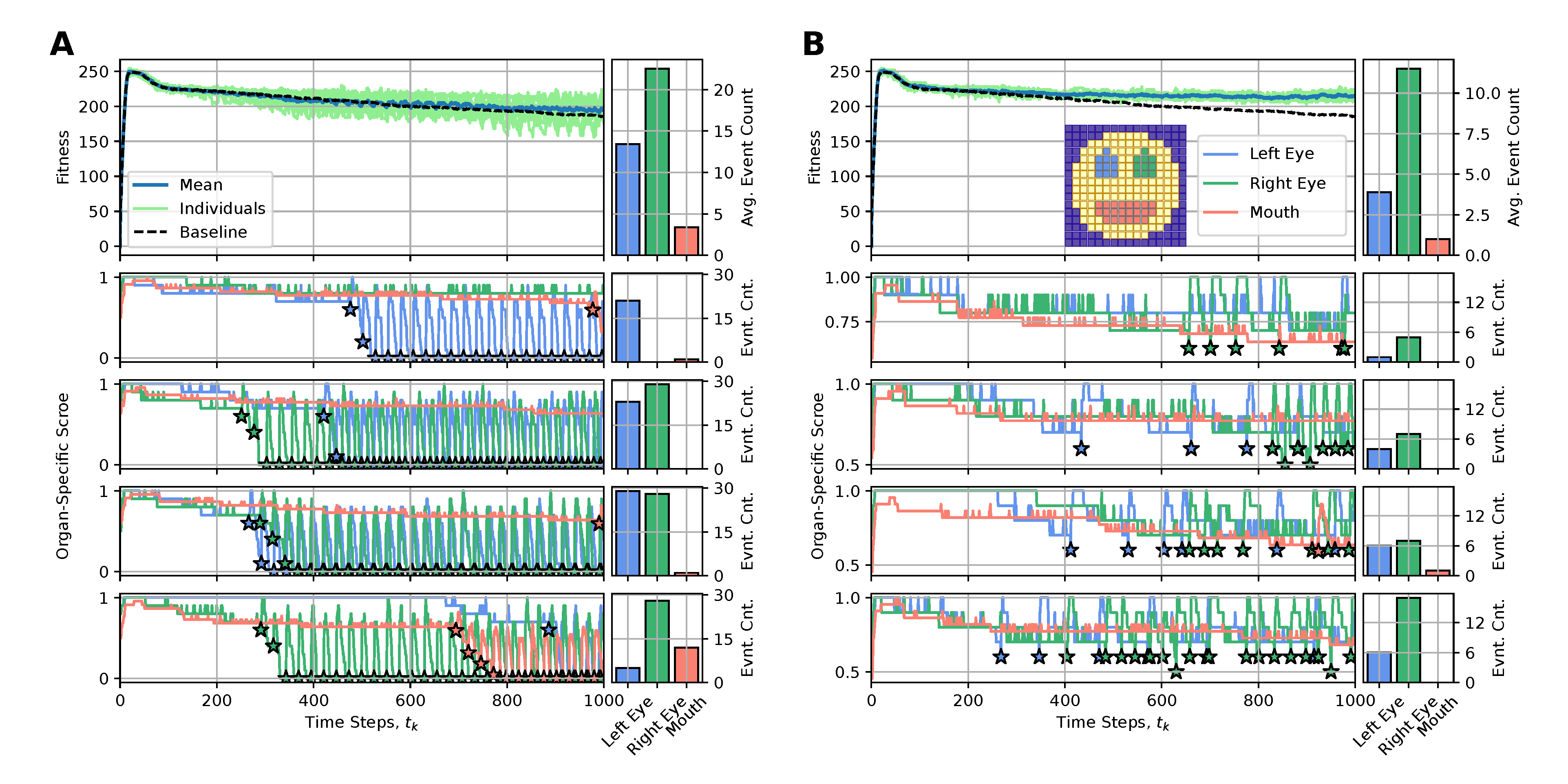

We thus deploy the NCA solution discussed in sec:results:antagonist-pleiotropy (c.f., fig:result:pleiotropy) for an extended life-span of time steps and apply the here discussed rejuvenation interventions whenever an organ’s score falls below a threshold value of . In fig:results:restoration:organ (A) and (B) we respectively present the results of this procedure by either (A) resetting all cells of an affected organ with their initial configuration or (B) only resetting the particular cells of an affected organ that express different cell states than their target types. We present for both (A) and (B) the long-term fitness scores of 10 statistically independent simulations, contrast their mean behavior with the baseline case without interventions (see fig:result:pleiotropy), and visualize the organ-specific scores and the corresponding intervention events for selected individuals.

We see that method (A) is not very sustainable: Although we generally measure significant short-term improvements in a respective organs’ scores after such intervention events, the intervened organs dissolve again quickly so that after time steps (which we set as the lower limit of two consecutive interventions, allowing for unperturbed development during this period) the organ needs to be reset again, and again. This periodic need for interventions - also reflected in correspondingly oscillating fitness scores of the entire organism - seems fundamental in our system and is not significantly affected by the delay between two interventions. The resulting fitness scores of the intervened individuals are only slightly improved compared to the baseline case.

Strikingly, if only the wrongly expressed cells of an affected organ are reconfigured to their initial state, as in case (B), very few of such targeted interventions (on the order of , c.f., bar plots in fig:results:restoration:organ (B)) suffice to sustainably restore degrading organs and allow the corresponding virtual organism to maintain its morphological integrity over an extended lifespan. The corresponding long-term fitness scores of the rejuvenated individuals show significant improvement compared to the baseline case and can even be stabilized into a steady state of a constant value of, here, ; notably, the difference to the maximum fitness score of right after the developmental stage at arises due to the accumulative stagnation loss term in eq:fitness.

4.4.4. Boundaries Matter: Organ Restoration Is More Efficient with the Injection of a Differential Pattern Including the Organ Cell States and Neighboring Cell States

Although the above approach is already promising, we further investigate how including the cells at the boundary to adjacent tissue surrounding the respective organs affects regeneration in our procedure. Thus, we additionally consider the respective boundary cells for the left- and right eyes in the evaluation of the respective organs’ scores but intentionally omit the boundaries of the mouth (c.f., emphasized color-coded cells in fig:results:restoration:socket, similar to fig:results:restoration:organ); notably, the mouth is much more stable than the eyes, and its cells already occupy a substantial fraction of the face.

Deploying the same experiments as above in sub:results:restoration:organ, we see in fig:results:restoration:socket that (A) interventions reconfiguring all the cells of affected organs (now also including their respective surrounding tissue) show similar performance to the corresponding case shown in fig:results:restoration:socket (A). However, the more targeted cell-specific interventions depicted in fig:results:restoration:socket (B) of now manipulating not only the wrongly expressed cells of an affected organ but also the wrongly expressed cells of their respective boundaries greatly improve the performance of restoration interventions compared to the cases fig:results:restoration:organ,fig:results:restoration:socket (A) and fig:results:restoration:socket (B). Here, an average number of as little as interventions (and in some cases even one single or two) suffice to stabilize the morphology of the here investigated smiley-face pattern organism in long lifespan experiments.

We conclude that boundaries (and more generally relations) between organs matter in our regeneration experiments: including surrounding tissue in detecting affected organs and in subsequent regeneration experiments that specifically target the wrongly expressed cells of the affected organs can be an efficient approach for regeneration and rejuvenation applications in our system.

A different but likewise promising approach is replacing the affected organs or cells directly with their target states (rather than their respective initial states as here). However, while “transplanting” entire organs can be effective, there is little quantitative difference in rejuvenation performance between replacing cells with their target states and reconfiguring cells into their initial states. From a biological perspective, the latter approach of resetting cells to their primordial states strikes us as conceptually and technologically more feasible, as the number of specialized target states might greatly exceed the number of necessary primordial initial states: resetting cells to their initial cell state, or at least to a particular primordial cell state suitable for starting a specific morphogenetic task, could serve as a general fallback mechanism to induce regeneration of the respective (here virtual) organism by restarting the developmental program locally.

At this point, we would like to stress that the developmental program of our NCA has neither been optimized for such long lifespans nor for the here proposed intervention experiments. The latter can thus be seen as minimally invasive ad-hoc cellular reconfiguration interventions, i.e., a dynamic and targeted “hacking” of the organism’s developmental plan by an external agent [

19] (

i.e.,, us, in this case).

Overall, we conclude that such a procedure of targeted cellular interventions is a reliable approach for rejuvenation in our system.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper, we aim to address a significant gap in the aging literature which so-far lacks - to the best of our knowledge – computational models of aging considering cellular information processing and multi-scale competency. We seek to address this knowledge gap by developing an evolutionary framework integrating the multi-scale competency architecture of multicellular tissue.

Specifically, we here utilize numerical tools from

Artificial Life [

61], so-called

Neural Celular Automata (NCAs) [

39,

41,

67] which we trained with an evolutionary algorithm to perform self-orchestrated targeted pattern formation,

i.e.,, morphogenesis of a

smiley-face pattern. The localized unicellular decision-making centers in our NCA implementation are modeled by

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) which perceive the numerical states of their direct cellular neighbors on the grid of the NCA to regulate their own cell state individually. In that way, NCAs substitute homeostatic and morphogenetic pathways of “real” multicellular biological tissue, the NCA-specific ANNs and numerical states respectively corresponding to cell-internal decision-making machinery (such as gene regulatory networks) and cell-type expressions.

Analogously to their biological counterparts, the NCA’s cells form their decisions following a global agenda, allowing the collective of cells to assume a predefined target pattern over a predefined developmental time, thus simulating the process of embryogenesis. The evolutionary algorithm selects mature phenotypes directly after the predefined developmental stage (i.e.,, fully grown tissue), specifically quantifying how well the cells of the corresponding NCAs can grow the facial features and organs of the smiley-face pattern in a fully self-orchestrated and decentralized way. Notably, the NCA’s cells do not in any way explicitly perceive time or their age (in terms of simulation time steps), but their dynamics is fully governed by regulating and exchanging noisy state information on the NCA’s grid. Yet, when deploying a successfully trained NCA for much longer times than necessary for development (at which stage evolutionary selection would have occurred), the tissue of the NCA expresses signs of aging, such as successively blurring boundaries between- or entirely losing a single or several organs. We emphasize that this behavior is emergent and happens without any further intervention.

We propose, that even in the absence of accumulated cellular or genetic damage, a biological system left without any goal in the morphospace will start degrading anatomically. Using an in silico model of homeostatic morphogenesis with a multi-scale competency architecture and information dynamics analysis, we find the following, which provides a novel perspective on aging dynamics with significant implications for longevity research and regenerative medicine: (1) Absence of Long-Term Morphostasis goal: Aging emerges naturally after development due to the lack of an evolved regenerative goal, rather than being caused by specific detrimental properties of developmental programs (e.g., antagonistic pleiotropy or hyperfunction); (2) Acceleration Factors vs. Root Cause: Cellular misdifferentiation, reduced competency, communication failures, and genetic damage all accelerate aging but are not its primary cause; (3) Information Dynamics in Aging: Aging correlates with increased active information storage and transfer entropy, while spatial entropy measures distinguish two dynamics, (i) the loss of structure and (ii) morphological noise accumulation; (4) Dormant Regenerative Potential: Despite organ loss, spatial information persists in our cybernetic tissue, indicating a memory of lost structures, which can be reactivated for organ restoration through targeted regenerative information; and (5) Optimized Regeneration Strategies: Restoration is most efficient when regenerative information includes differential patterns of affected cells and their neighboring tissue, highlighting strategies and protocols for rejuvenation.

While the cells in our system learn to perform morphogenesis, i.e, how to grow an adult morphology successfully, we still observe aging effects in long-term simulations even without artificially perturbing the NCA’s parameters. These results suggest that development and morphostasis, while close in terms of morphological trajectories and tasks still significantly diverge. To counteract aging, it is therefore necessary to (re)activate a developmental/regenerative goal. We explicitly demonstrated this by providing our cybernetic tissue with the necessary information for regeneration, thereby inducing rejuvenation through self-organization at the anatomical level. Our results suggest a roadmap for rejuvenation therapies, particularly that curing aging may imply to provide a new goal to the tissue, i.e., regeneration. In other words, this suggests that solving regeneration solves aging. As currently debated, regenerative species, such as salamanders or planaria, might not age at all. While, already known for planaria, this is the subject of current research for salamander. The latter not only lack senescent phenotypes but it is indeed impossible to define an epigenetic clock for specimen older than four years [

97]. One extension to the present work thus will be comparing a system that has learned to regenerate and actively maintain morphostasis after development to an aging system that has only been trained on morphogenesis tasks. Understanding their differences in terms of information dynamics will allow us to form a thorough understanding of the homeostatic loops that allow differently expressed cells in a self-assembling tissue to maintain their integrity against adversarial attacks or thermodynamic noise.

This work also emphasized how to optimize regenerative strategies. Our results show the importance of the information at the level of the borders of integrated tissue or organs for regeneration. This importance can be found in the field of bioelectricity. Indeed, research indicates that mutations in critical neurogenesis genes, such as Notch, can lead to developmental defects [

98]. These organ defects can be cured through the overexpression or activation of native HCN2 (hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated) channels [

99,

100,

101]. As voltage-sensitive ion channels, HCN2 channels respond to their cellular environment by enhancing hyperpolarization in cells that are slightly polarized, while remaining inactive in depolarized cells. This mechanism functions analogously to “contrast enhancers,” which sharpen weak differences in membrane potential (

) across compartment boundaries, much like a sharpening filter brings clarity to a blurred image. In other words, HCN2 enhances and sharpens the borders in the bioelectrical pattern.

Moreover, our results suggest that a multicellular collective is capable of maintaining the memory about fully degraded features of an organism, as explicitly demonstrated here via organ regeneration experiment and information dynamics analysis. This suggests that this information is dormant and can be “retrieved” by injecting the appropriate signals that trigger regeneration in our system. This finding opens up exciting possibilities for future research, particularly in the realm of regenerative medicine and bioengineering. By understanding how cells store and retrieve hierarchical anatomical information, we could potentially develop new methods to promote regeneration in damaged tissues or organs. Additionally, exploring the mechanisms by which cells communicate and coordinate to maintain this memory could lead to breakthroughs in preventing age-related degeneration. For example, targeting specific bioelectrical patterns or enhancing the function of key ion channels like HCN2 could help maintain tissue integrity and function over time. Furthermore, the here discussed principles targeting the “software” of life could be applied to synthetic biology and rejuvenation, where designing artificial systems with similar regenerative capabilities [

102,

103] as well as new aging treatments might become feasible [

26,

34].

While our current framework is capable of self-assembling target patterns of heterogeneously distributed cell types, the ANN-based decision-making centers of our NCA’s cells are implemented homogeneously: all cells of an NCA typically share the same ANN structure and parameters, and thus the same basic functionality. Yet, the cells might be configured differently and thus effectively behave heterogeneously due to cell-specific state expressions and input relations, in short, due to their morphogenetic history. In that way, these artificial cells’ functionality mirrors gene regulatory networks. Thus, further in silico studies could investigate minimally complex high-level interventions necessary to induce robust regenerative effects in affected tissue simply by reconfiguring the cellular collective locally. Furthermore, allowing cell-specific functional mutations during the lifetime of such virtual organisms might be an intriguing way to study morphogenetic and aging-related implications of heterogeneity.

Our results validate aspects of both damage-based and programmatic theories of aging [

1,

4,

5] but in very different ways. On the one hand, accelerated morphological decline (or an increased rate of aging) in our system mainly originates from: increasing cellular misdiffentiation, decreasing cellular competency, defective cell-cell communication, and accumulation of genetic damage. While these four characteristics align with damage-based theories of aging [

6], they are only sufficient not necessary, i.e., not really causal, as our system undergoes aging also in their absence. Therefore, our model tends towards programmatic theories of aging, antagonistic pleiotropy or hyperfunction [

14,

15], or the theories of the software design flaw [

5,

26], in which the causes of aging have to be found in development. Similarly, but not analogously, we here relate aging to the absence of a developmental/regenerative or morphostatic goal, which nonetheless may imply an abnormal continuation of specific developmental pathways that are not beneficial for anatomical homeostasis. However, our results suggest that developmental programs (that are learned during evolution) can also qualify as regenerative pathways when “reactivated” in aging individuals, thus representing a potential protocol for a cure for aging ref. In a sense, regeneration is learned for free and is just dormant after development. This is an important result and indicates that we should focus our research efforts for curing aging on the reactivation of the regenerative capabilities. And our results suggest an experimental research program for regenerative medicine where we create an embryo-like environment allowing the tissue to regenerate. In turn, when interpreting the NCAs’ numerical states as bioelectric degrees of freedom, instead of transcriptomic cell-state expressions, a promising approach toward innovative no-aging or rejuvenation treatments might be to focus on high-level control layers such as bioelectricity that encode collective anatomical goals [

26,

102].

Our study showed fundamental computational principles in multicellular aging systems, bridging developmental biology with aging research. We explicitly demonstrate that developmental pathways, initially used for morphogenesis, may be dormant and can be reactivated for regeneration and tissue maintenance later in life. Moreover, we observed that cells collectively retain and manipulate morphological information, indicating that targeted interventions could potentially rejuvenate or maintain tissue integrity as organisms age.

Overall, we focused on the loss of goal-directedness in morphospace as the cause of the degradation of the system in this article. However, it may be possible that this cause extends towards nother levels in biological systems but also to artificial ones. For example, it may be possible that to counteract psychological decline during aging by giving new life goals to organism, which is in line with resistance to cognitive decline that has been found in elderly having high social engagement and new activities [

104,

105,

106]. This can take place by providing new patterns (as occurs in metamorphosis [

107,

108]) within a body, or via communication of signals between bodies, as recently observed in cross-embryo morphogenetic error correction effects [

109]. In terms of learning theory, we could ask: what’s the objective of a goal-directed system once it reached its goal? Our results may point towards the idea that a goal-directed system that achieved its goal becomes an aging system in a broad sense: a system deviating from its goal slowly. For a morphogenetic system, this might be reflected by a slowly degrading anatomy, a slight shift in morphospace [

21] ultimately leading to death: an anatomical configuration incompatible with life. For AI systems, a decline in performance, similarly to what we found with

ChatGPT or other LLMs [

110], could be interpreted as aging or developmental defects after the target morphology has been reached [

39]. Overall, our results suggest that reaching a goal by generative means is completely different from maintaining it. Thus, to engineer robust and autonomous AI and intelligent robotic systems or synthetic morphology we should integrate the learning of these two different tasks.

Exploring these principles further could lead to significant advancements in delaying or reversing age-related decline. Integrating computational models with experimental biology might pave the way to uncover new strategies to enhance regeneration through manipulating cellular behavior, potentially extending the healthy lifespan of tissues.

Future research will focus on applying these computational insights to real-world biological systems, aiming to develop therapies that modulate aging processes and improve recovery from injuries, thus optimizing the health span of multicellular organisms. These findings not only deepen our understanding of the aging process but also highlight the potential of using computational approaches to predict and control the dynamics of cellular systems in aging. The insights gained from this study open new avenues for research in aging and regenerative medicine, paving the way for novel interventions that could one day transform our approach to aging and chronic disease treatment.

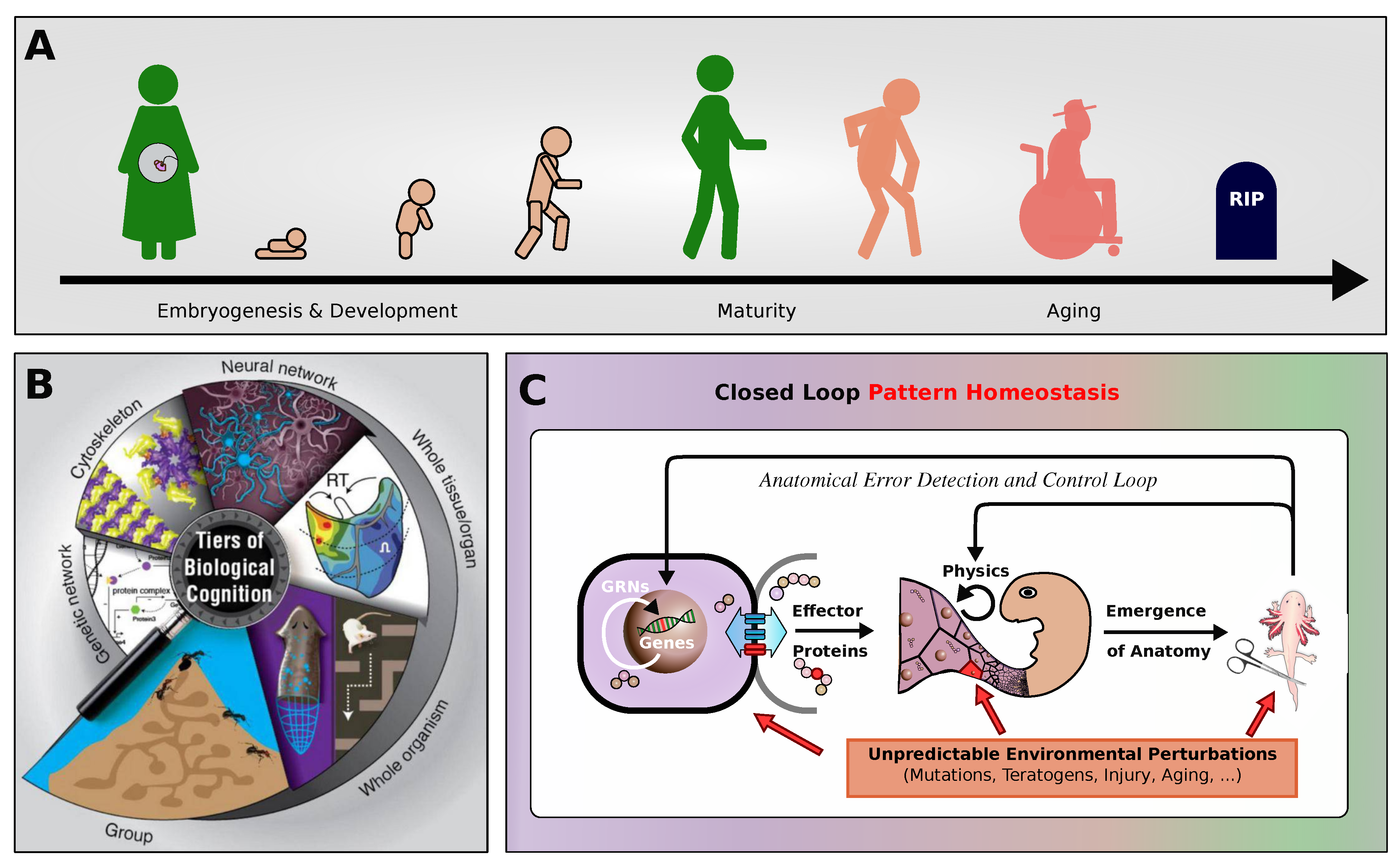

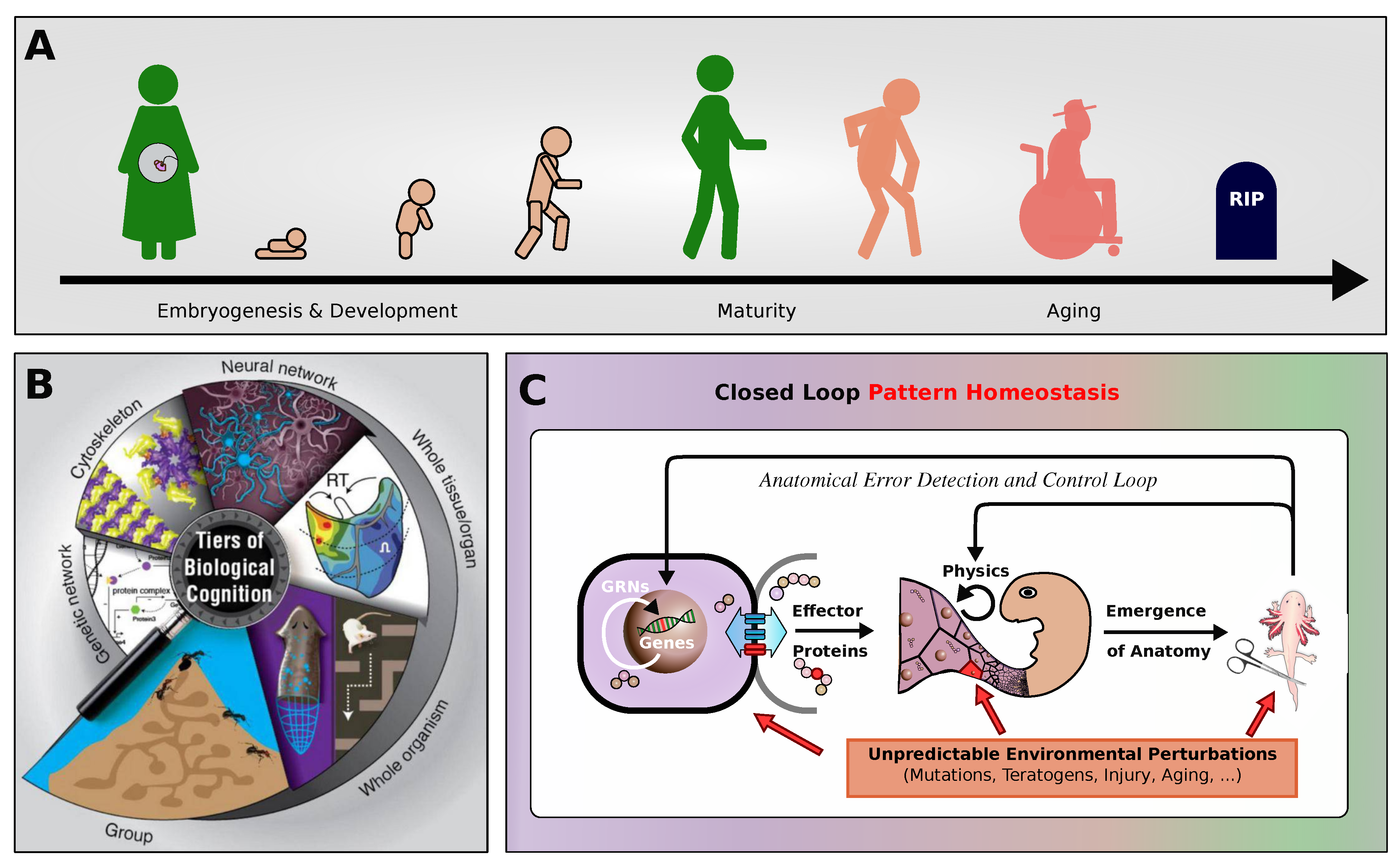

Figure 1.

(A) A schematic illustration of the stages of life of a complex organism, starting from embryogenesis, development and growth, through maturity, decline, aging, and eventually death. (B) Multicellular organisms are composites of hierarchically interlocked layers of biological self-organization, spanning physical scales from the molecular level, over cells, tissues, organs, to organisms and even groups or collectives of individuals. (C) To develop an organism’s morphology, and sustain its integrity against environmental perturbations, biology maintains a multi-scale closed loop pattern homeostasis mechanism, where the components at every scale of self-organization are capable of self-regulatory and error-correcting behavior. Fundamentally, cells themselves have numerous behavioral and information processing capabilities: To control multicellular morphology during embryogenesis and also in mature and even aging tissue, cells utilize a variety of communication channels, such as bioelectrical, biochemical, and biomechanical processes, enacting local communication protocols via intercellular signaling, intracellular information processing, and cell-state regulation2. This can be seen as a process of physiological computation by which cells interact and respond to their environment to create complex patterns and structures, guiding embryogenesis, maturation, metamorphosis, remodeling, regeneration, and suppression of cancer and aging3. In most organisms, with only very few exceptions, these homeostatic processes eventually break down, leading to irreversible morphological decline, aging, and death.

Figure 1.

(A) A schematic illustration of the stages of life of a complex organism, starting from embryogenesis, development and growth, through maturity, decline, aging, and eventually death. (B) Multicellular organisms are composites of hierarchically interlocked layers of biological self-organization, spanning physical scales from the molecular level, over cells, tissues, organs, to organisms and even groups or collectives of individuals. (C) To develop an organism’s morphology, and sustain its integrity against environmental perturbations, biology maintains a multi-scale closed loop pattern homeostasis mechanism, where the components at every scale of self-organization are capable of self-regulatory and error-correcting behavior. Fundamentally, cells themselves have numerous behavioral and information processing capabilities: To control multicellular morphology during embryogenesis and also in mature and even aging tissue, cells utilize a variety of communication channels, such as bioelectrical, biochemical, and biomechanical processes, enacting local communication protocols via intercellular signaling, intracellular information processing, and cell-state regulation2. This can be seen as a process of physiological computation by which cells interact and respond to their environment to create complex patterns and structures, guiding embryogenesis, maturation, metamorphosis, remodeling, regeneration, and suppression of cancer and aging3. In most organisms, with only very few exceptions, these homeostatic processes eventually break down, leading to irreversible morphological decline, aging, and death.

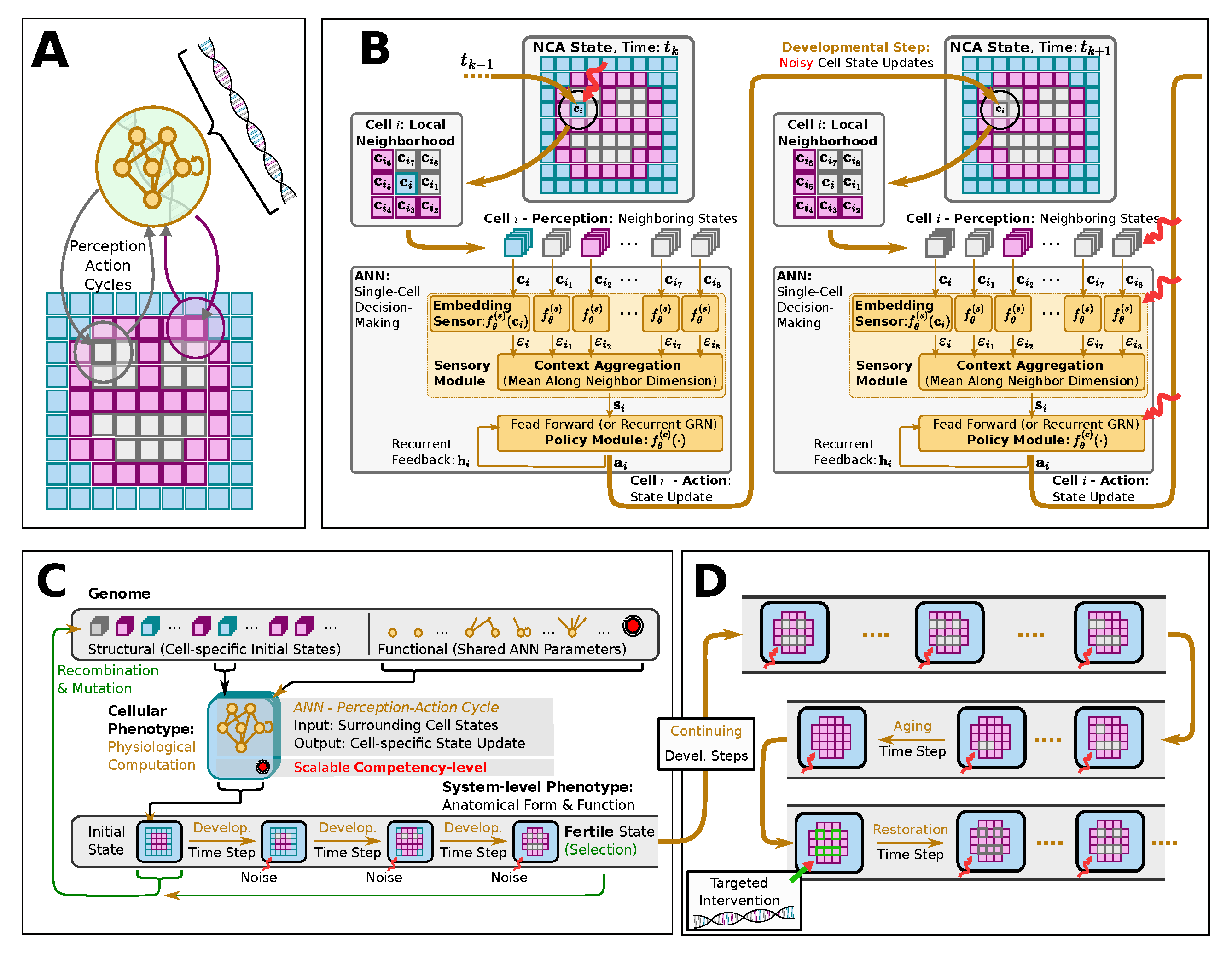

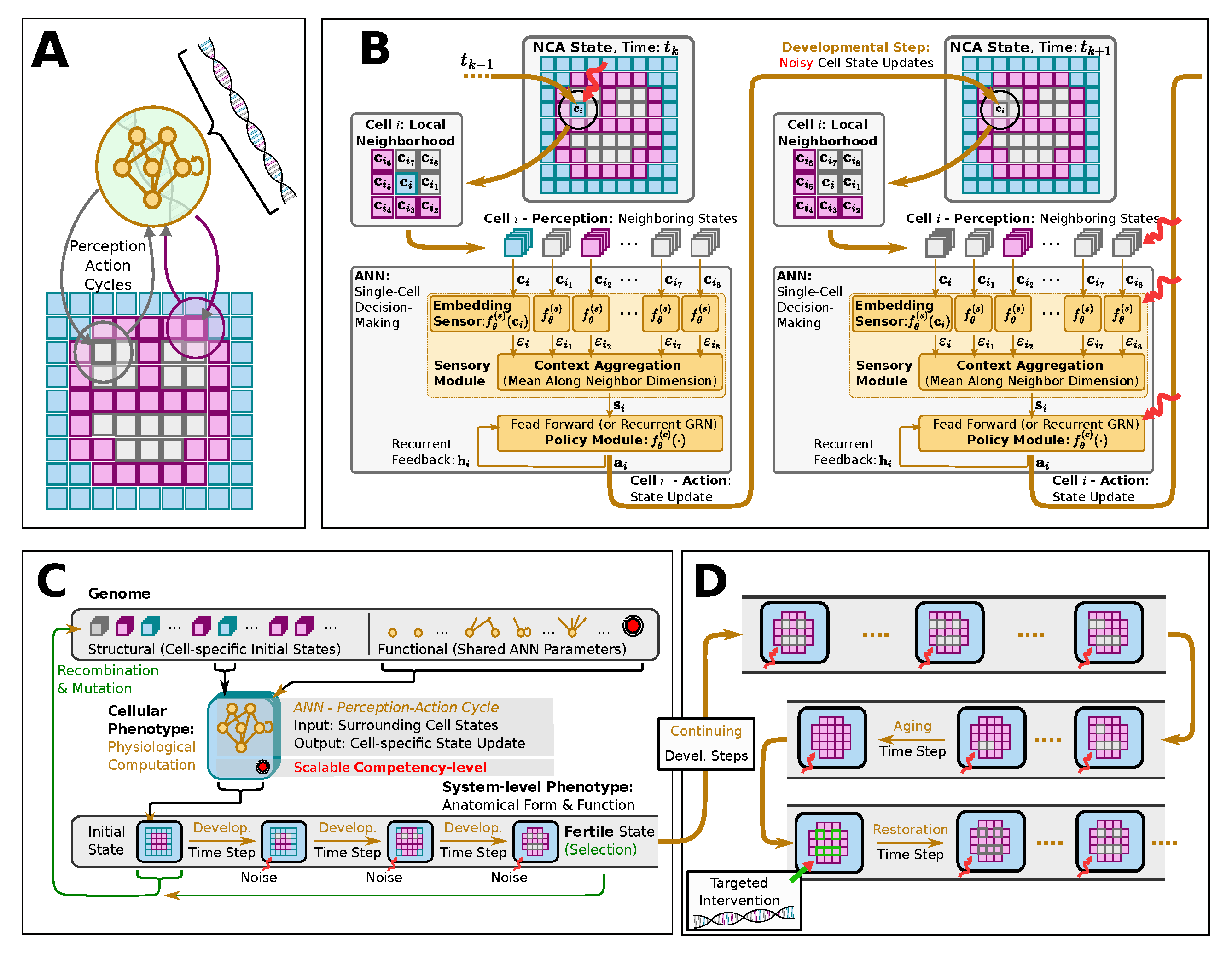

Figure 2.

(

A): (A): Schematic computational model of a biologically inspired multi-scale competency architecture [

19], relying on Neural Cellular Automata [

39,

67] (NCAs) in an evolutionary setting [

41]:: in an evolutionary NCA, a genetic code, i.e., a cell’s “DNA” (represented by a string of numerical parameters), is compiled into a uni-cellular phenotype containing a proto-cognitive decision-making center (represented by a tiny recurrent neural network parameterized by the “DNA”) by which the cellular agent can actively regulate its own numerical cell state based on local measurements of the states of its immediate cellular neighbors on a square grid of cells. In that way, the collective of cells can be trained, or evolved, to perform morphogenesis of a predefined target pattern of expressed cell types (color-coded in blue, magenta, and white), of, e.g., a smiley-face pattern (reminiscent of the bioelectric craniofacial prepattern defining the amphibian face [

79]. (

B): : Detailed information flowchart of uni-cellular decision-making of cells on the grid of a NCA, modeling the process of morphogenesis (c.f., (A)): each cell expresses its cell-type based on local communication protocols with its neighboring cells so the collective of cells self-assembles a target pattern. This is implemented via subsequent uni-cellular perception-action cycles that update each cell’s respective state on the NCA’s grid purely based on local measurements of neighboring cell states. (

C): Schematics of the evolutionary process of uni-cellular competencies that drive the self-orchestrated morphogenesis of a target pattern (here, of a smiley, face). (

D): Schematics of long-term behavior of an NCA evolved in (

C) that is not controlled by the evolutionary process. Developmental errors or noise (red wiggly arrows) might lead to a collapse of the target pattern over time, especially long after the selection process occurs (where genetic material is passed on to the next generation. Following pleiotropic considerations, we assume that the long-term “solutions” or the target morphogenetic state might significantly differ from the target state that the evolutionary process “sees” through selection, simply because different states might be more probable (such as, here, a “red” circle without facial features). Moreover, detecting such deviating pleiotropic defects (missing facial features, in our case), and performing targeted interventions of the most affected cells allow us to “reprogram“ the cellular collective and reset it via targeted interventions - without further optimization or adaptation - so the tissue auto-regenerates to the original target pattern.

Figure 2.

(

A): (A): Schematic computational model of a biologically inspired multi-scale competency architecture [

19], relying on Neural Cellular Automata [

39,

67] (NCAs) in an evolutionary setting [

41]:: in an evolutionary NCA, a genetic code, i.e., a cell’s “DNA” (represented by a string of numerical parameters), is compiled into a uni-cellular phenotype containing a proto-cognitive decision-making center (represented by a tiny recurrent neural network parameterized by the “DNA”) by which the cellular agent can actively regulate its own numerical cell state based on local measurements of the states of its immediate cellular neighbors on a square grid of cells. In that way, the collective of cells can be trained, or evolved, to perform morphogenesis of a predefined target pattern of expressed cell types (color-coded in blue, magenta, and white), of, e.g., a smiley-face pattern (reminiscent of the bioelectric craniofacial prepattern defining the amphibian face [

79]. (

B): : Detailed information flowchart of uni-cellular decision-making of cells on the grid of a NCA, modeling the process of morphogenesis (c.f., (A)): each cell expresses its cell-type based on local communication protocols with its neighboring cells so the collective of cells self-assembles a target pattern. This is implemented via subsequent uni-cellular perception-action cycles that update each cell’s respective state on the NCA’s grid purely based on local measurements of neighboring cell states. (

C): Schematics of the evolutionary process of uni-cellular competencies that drive the self-orchestrated morphogenesis of a target pattern (here, of a smiley, face). (

D): Schematics of long-term behavior of an NCA evolved in (

C) that is not controlled by the evolutionary process. Developmental errors or noise (red wiggly arrows) might lead to a collapse of the target pattern over time, especially long after the selection process occurs (where genetic material is passed on to the next generation. Following pleiotropic considerations, we assume that the long-term “solutions” or the target morphogenetic state might significantly differ from the target state that the evolutionary process “sees” through selection, simply because different states might be more probable (such as, here, a “red” circle without facial features). Moreover, detecting such deviating pleiotropic defects (missing facial features, in our case), and performing targeted interventions of the most affected cells allow us to “reprogram“ the cellular collective and reset it via targeted interventions - without further optimization or adaptation - so the tissue auto-regenerates to the original target pattern.

Figure 3.

Typical fitness score evaluations during developmental steps of morphogenesis of 50 statistically independent runs of an NCA that has been evolved to self-assemble a -smiley-face pattern. Example NCA states from the individual with the highest developmental fitness score (c.f., red “elite trajectory” in bottom panel) are presented throughout the developmental phase as temporal snapshots corresponding to the ticks of the horizontal axis; background-, facial-, and internal organ cells (of eyes and mouth) are colored purple, yellow, and red, respectively.

Figure 3.

Typical fitness score evaluations during developmental steps of morphogenesis of 50 statistically independent runs of an NCA that has been evolved to self-assemble a -smiley-face pattern. Example NCA states from the individual with the highest developmental fitness score (c.f., red “elite trajectory” in bottom panel) are presented throughout the developmental phase as temporal snapshots corresponding to the ticks of the horizontal axis; background-, facial-, and internal organ cells (of eyes and mouth) are colored purple, yellow, and red, respectively.

Figure 4.

Same as fig:system:morphogenesis, but evaluated for developmental (or NCA-) time steps, furthermore displaying multiple example trajectories of NCA-states (color-coded): The blue-emphasized individual maintains an approximate smiley-face pattern for exceptionally long times, and thus displays the highest long-term fitness score. The orange- and green-emphasized individuals lose, respectively, either a left or right eye at steps, and both eyes at steps, but maintain their mouth for long times; these individuals display close-to-average long-term fitness scores. The red-emphasized individual eventually loses the mouth, thus displaying the lowest long-term fitness score among the presented trajectories. The spherical face structure seems incredibly robust.

Figure 4.

Same as fig:system:morphogenesis, but evaluated for developmental (or NCA-) time steps, furthermore displaying multiple example trajectories of NCA-states (color-coded): The blue-emphasized individual maintains an approximate smiley-face pattern for exceptionally long times, and thus displays the highest long-term fitness score. The orange- and green-emphasized individuals lose, respectively, either a left or right eye at steps, and both eyes at steps, but maintain their mouth for long times; these individuals display close-to-average long-term fitness scores. The red-emphasized individual eventually loses the mouth, thus displaying the lowest long-term fitness score among the presented trajectories. The spherical face structure seems incredibly robust.

Figure 5.

Panels (

A-D): Schematic visualization of the amplified damaging processes to cellular competencies corresponding to sec:results:induced-degeneracy:noise,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:competency,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:cell-communication,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:ann-damage, respectively. (

A): The fitness over the lifetime of the

smiley-face NCA discussed in sec:system where the noise level for cell-state updates is linearly increased from

to

(emphasized by red line), for

time steps

; gray lines show statistically independent trajectories of individual lifetimes of the NCA, the blue line represents the corresponding ensemble mean, and the black-dashed line is the baseline mean fitness without corrupted competencies (c.f., fig:result:pleiotropy). (

B): similar to (

A) but corrupting cellular competencies via a successively decreasing decision-making probability

to

following the functional form

(see red line). (

C): similar to (

A, B) but permanently corrupting the intercellular communication pathways by successively disabling randomly selected communication channels (reminiscent of gap-junctions [

50]) between neighboring cells by linearly decreasing the gap-junction prohibiting probability from

to

(see text and red line). (

D): similar to (

A-C) but accumulating genetic damage in the unicellular decision-making machinery,

i.e.,, corrupting intracellular information processing and decision-making by adding zero-centered Gaussian noise of standard deviation

at every time step to the cells’ ANN parameters (which is equivalent to ANN parameters corrupted by

at time-step

with

). In (

A-D), the top panels schematically illustrate the perception-action cycles of every cell over the lifespan of the NCA; the particular processes affecting the cellular competencies, thus enhancing the rate of degradation of the target pattern in each panel (

A-D), are emphasized from left to right by red blurry blocks: this involves (

A) increasingly misdifferentiation and misperception of cell states by neighbours, (

B) increasingly unreliable cell decisions directly affecting the NCA’s action output, (

C) successively corrupted intercellular communication channels directly affecting the exchange of information between neighbors, and (

D) accumulation of genetic damage by successively diffusing the cells’ ANN parameters directly affecting the unicellular decision-making machinery.

Figure 5.

Panels (

A-D): Schematic visualization of the amplified damaging processes to cellular competencies corresponding to sec:results:induced-degeneracy:noise,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:competency,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:cell-communication,sec:results:induced-degeneracy:ann-damage, respectively. (

A): The fitness over the lifetime of the

smiley-face NCA discussed in sec:system where the noise level for cell-state updates is linearly increased from

to

(emphasized by red line), for

time steps

; gray lines show statistically independent trajectories of individual lifetimes of the NCA, the blue line represents the corresponding ensemble mean, and the black-dashed line is the baseline mean fitness without corrupted competencies (c.f., fig:result:pleiotropy). (

B): similar to (

A) but corrupting cellular competencies via a successively decreasing decision-making probability

to

following the functional form

(see red line). (

C): similar to (

A, B) but permanently corrupting the intercellular communication pathways by successively disabling randomly selected communication channels (reminiscent of gap-junctions [

50]) between neighboring cells by linearly decreasing the gap-junction prohibiting probability from

to

(see text and red line). (

D): similar to (

A-C) but accumulating genetic damage in the unicellular decision-making machinery,

i.e.,, corrupting intracellular information processing and decision-making by adding zero-centered Gaussian noise of standard deviation

at every time step to the cells’ ANN parameters (which is equivalent to ANN parameters corrupted by

at time-step

with

). In (

A-D), the top panels schematically illustrate the perception-action cycles of every cell over the lifespan of the NCA; the particular processes affecting the cellular competencies, thus enhancing the rate of degradation of the target pattern in each panel (

A-D), are emphasized from left to right by red blurry blocks: this involves (

A) increasingly misdifferentiation and misperception of cell states by neighbours, (

B) increasingly unreliable cell decisions directly affecting the NCA’s action output, (

C) successively corrupted intercellular communication channels directly affecting the exchange of information between neighbors, and (

D) accumulation of genetic damage by successively diffusing the cells’ ANN parameters directly affecting the unicellular decision-making machinery.

Figure 6.