Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

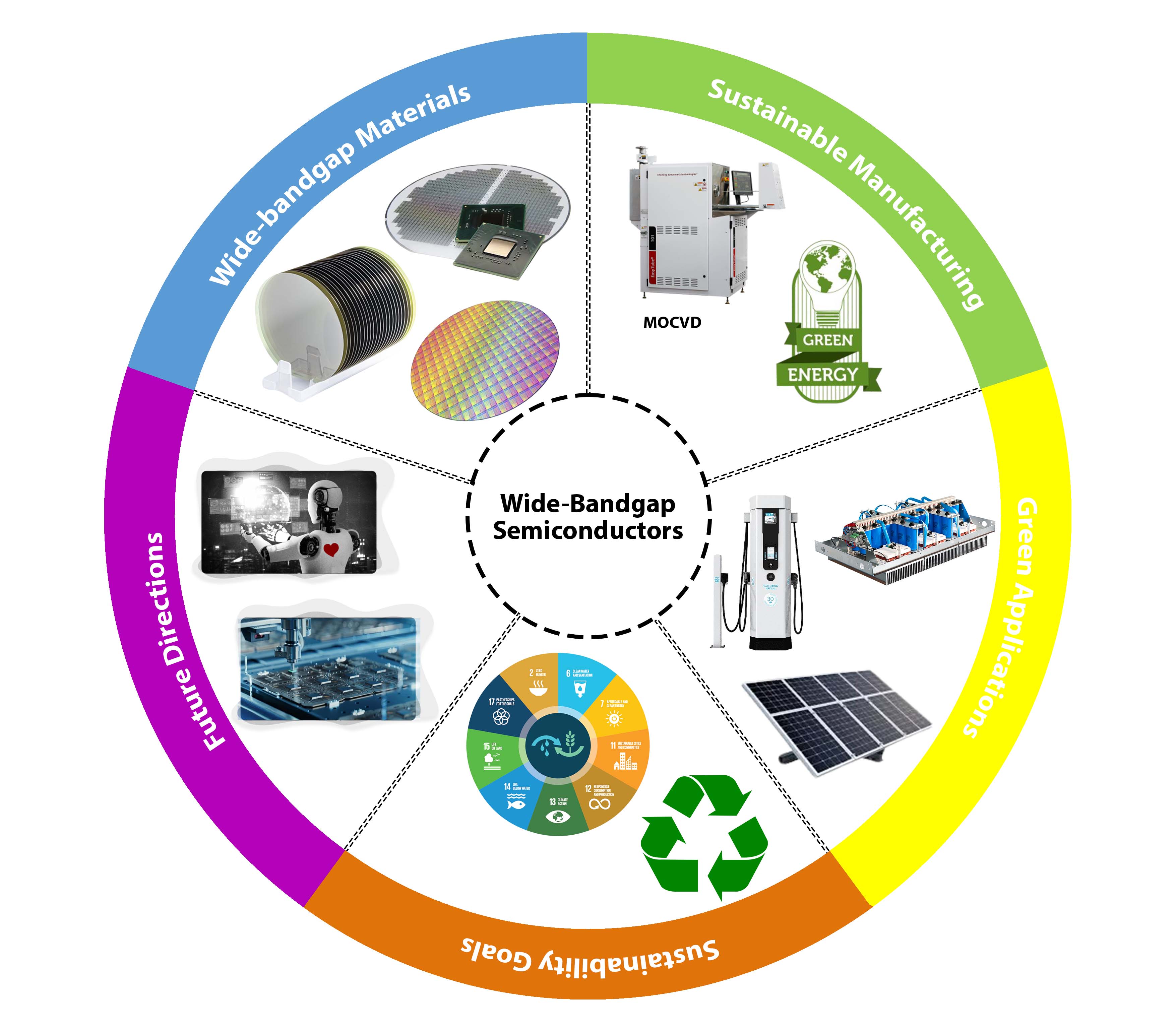

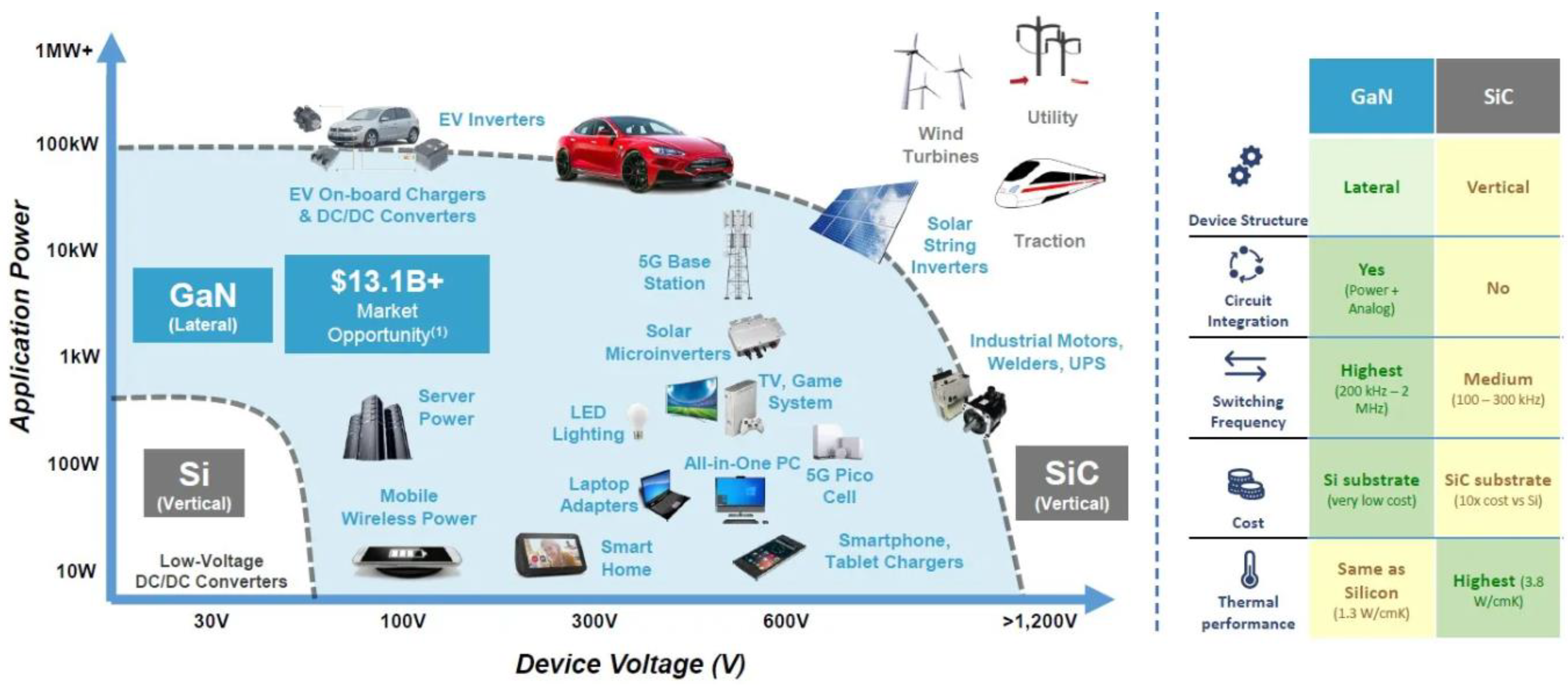

Wide-bandgap (WBG) semiconductors such as silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) have become pivotal in high-power, high-frequency, and high-temperature applications. Their superior properties, including higher thermal conductivity, breakdown voltage, and energy efficiency, make them essential for advanced technologies like electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and 5G infrastructure. However, their production processes are resource-intensive and pose significant environmental challenges. This review explores recent innovations in sustainable WBG manufacturing, focusing on low-energy epitaxial growth techniques, recycling of semiconductor materials, and efforts to reduce toxic byproducts. It also highlights the role of WBG materials in driving next-generation electronic systems and addresses the environmental concerns associated with scaling these materials for widespread use. The potential of Ultrawide-Bandgap (UWBG) materials for even more extreme applications is discussed, underscoring the need for continued innovation in sustainable practices to ensure the long-term viability of WBG technologies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

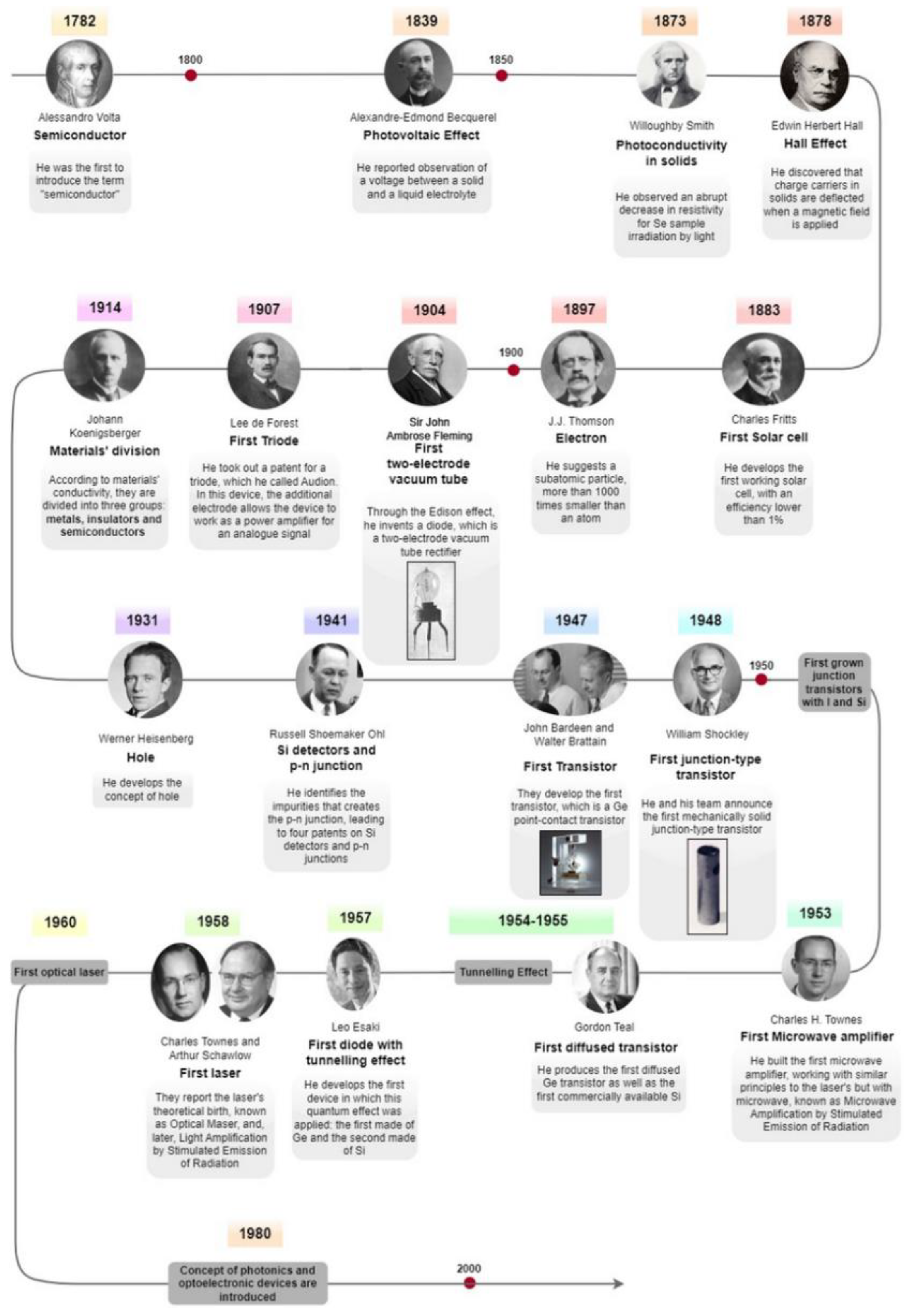

2. Semiconductor Fundamentals and Historical Development

2.1. Introduction to Semiconductors

2.2. The Shift to Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Semiconductors

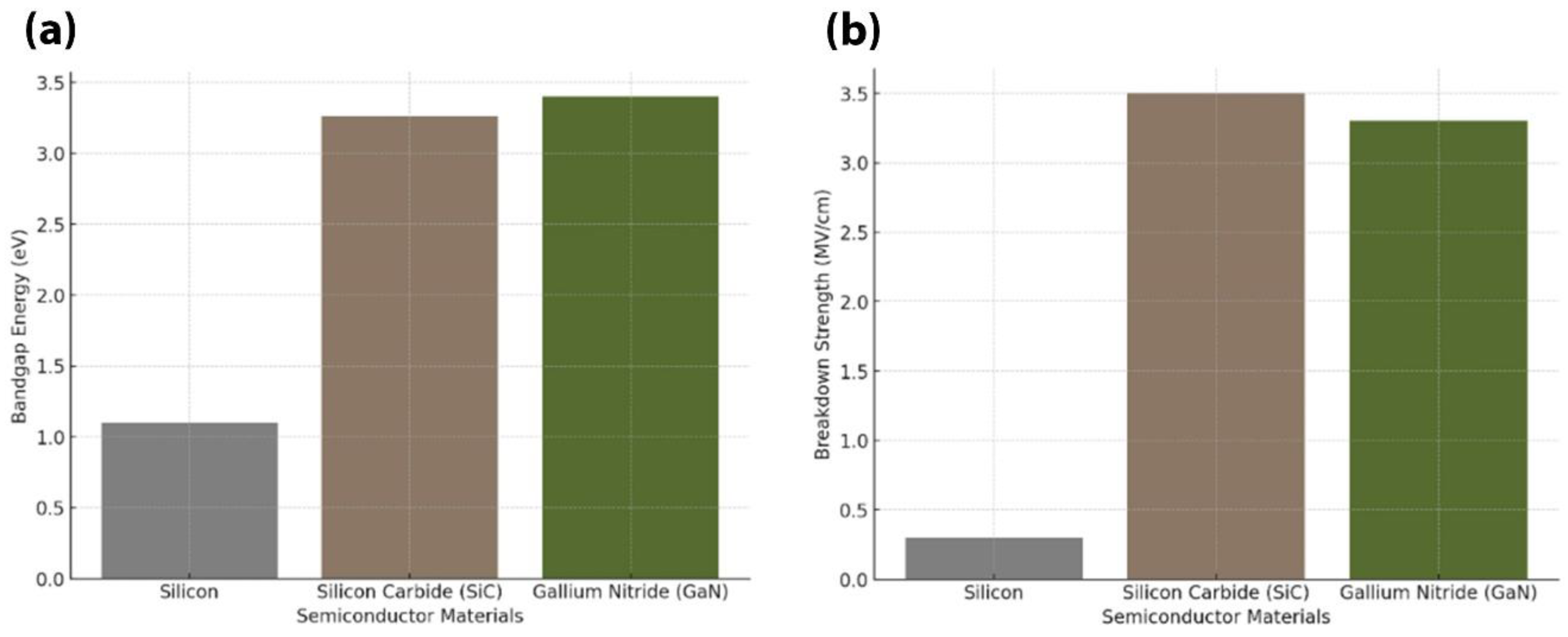

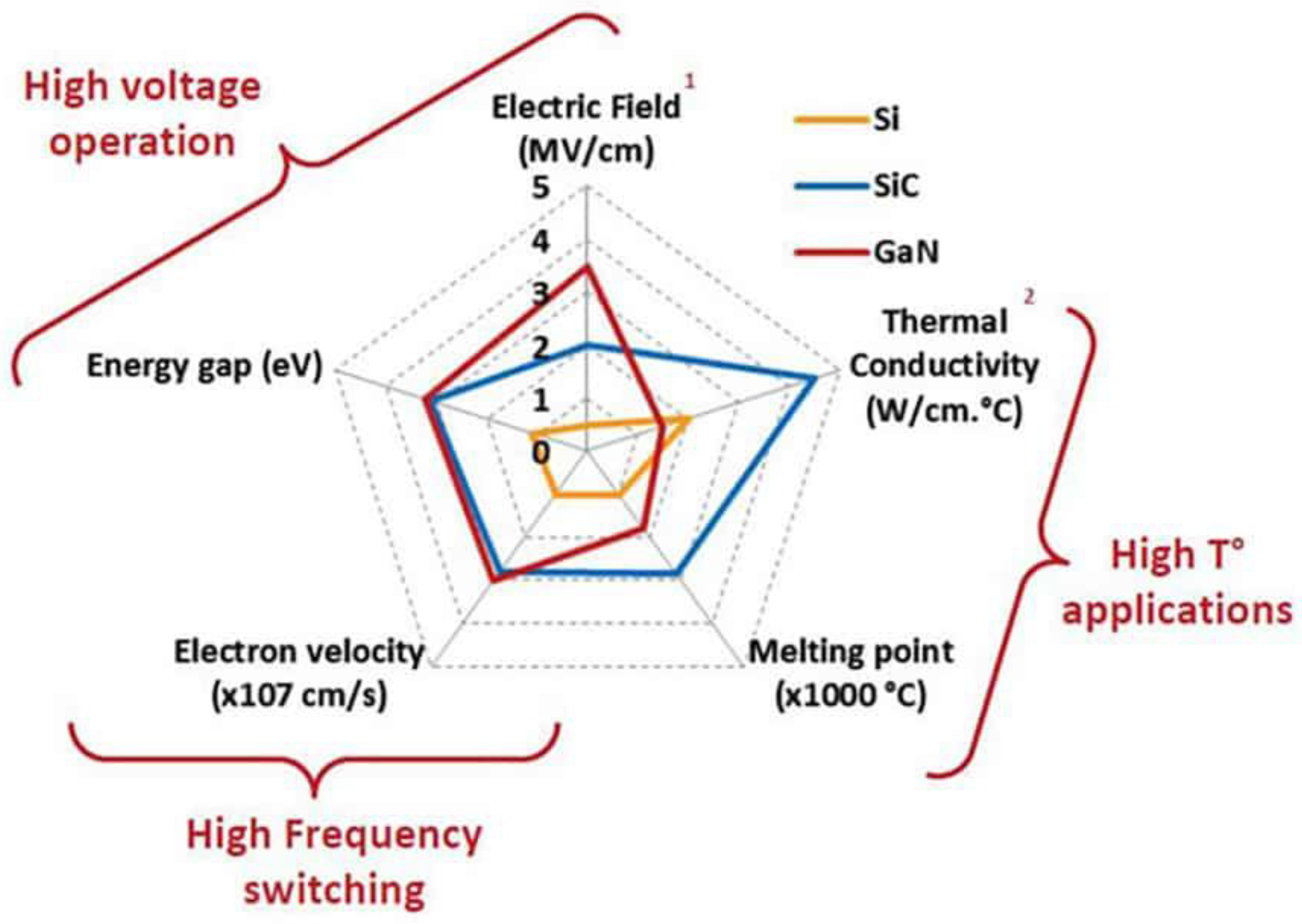

2.3. Fundamental Properties of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Semiconductors

| ELECTRICAL PROPERTY | SI | 4H-SIC | GAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| BANDGAP ENERGY (EV) | 1.1 | 3.26 | 3.4 |

| THERMAL CONDUCTION (W/CM.K) | 1.5 | 3.7 | 1.3 |

| ELECTRON MOBILITY (CM2/V.S) | 1300 | 900 | 900 - 2000 |

| SATURATION DRIFT VELOCITY | 1 x 107 | 2 x 107 | 2.5 x 107 |

2.3. Historical Development of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Semiconductors

Emergence of SiC and GaN

Pivotal Technological Advancements

Impact on Modern Applications

Evolution Toward Sustainable Manufacturing

Environmental Impact of Manufacturing

Current Innovations

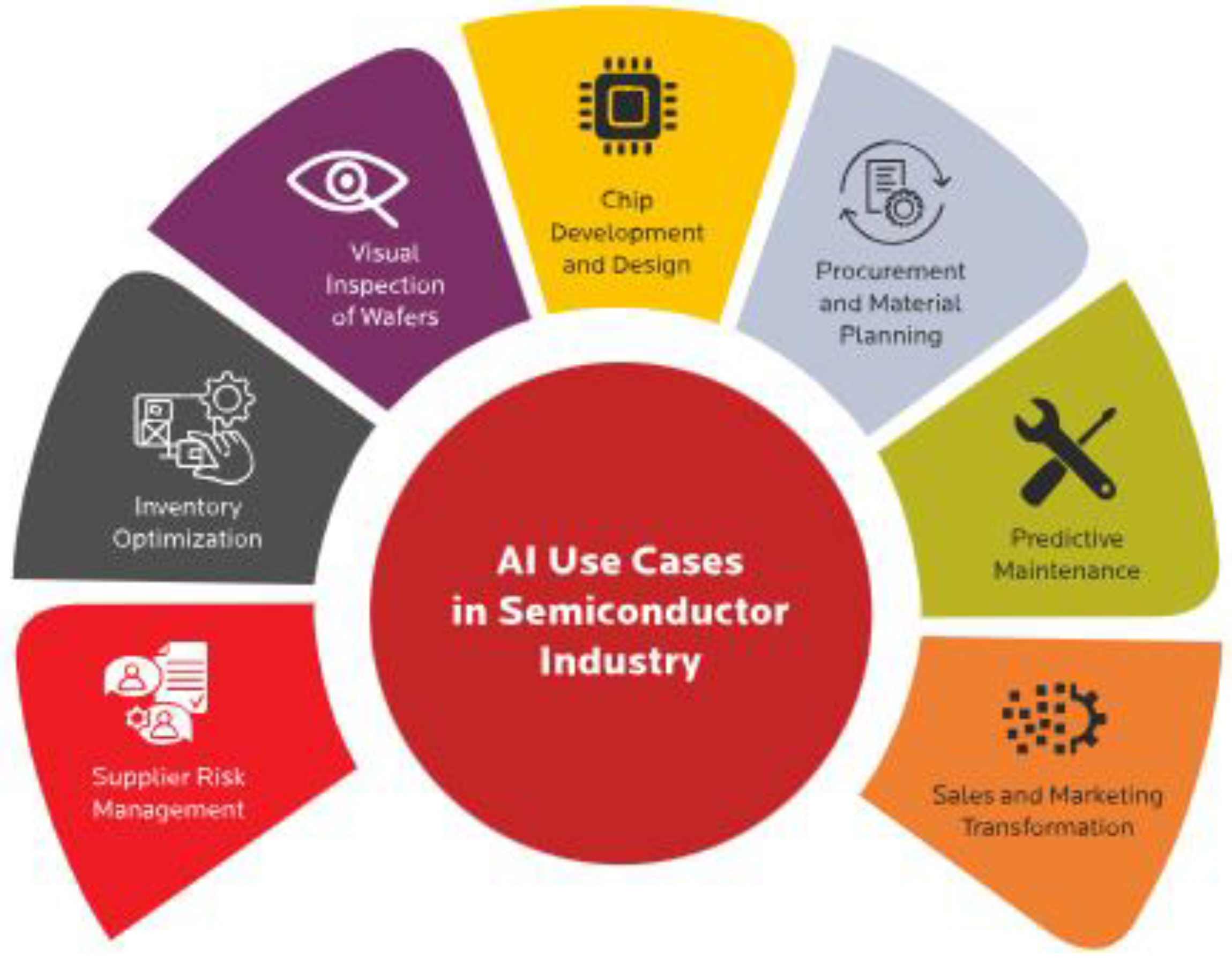

Integration of Industry 4.0 and Reconfigurable Technologies

Toward a Circular Economy

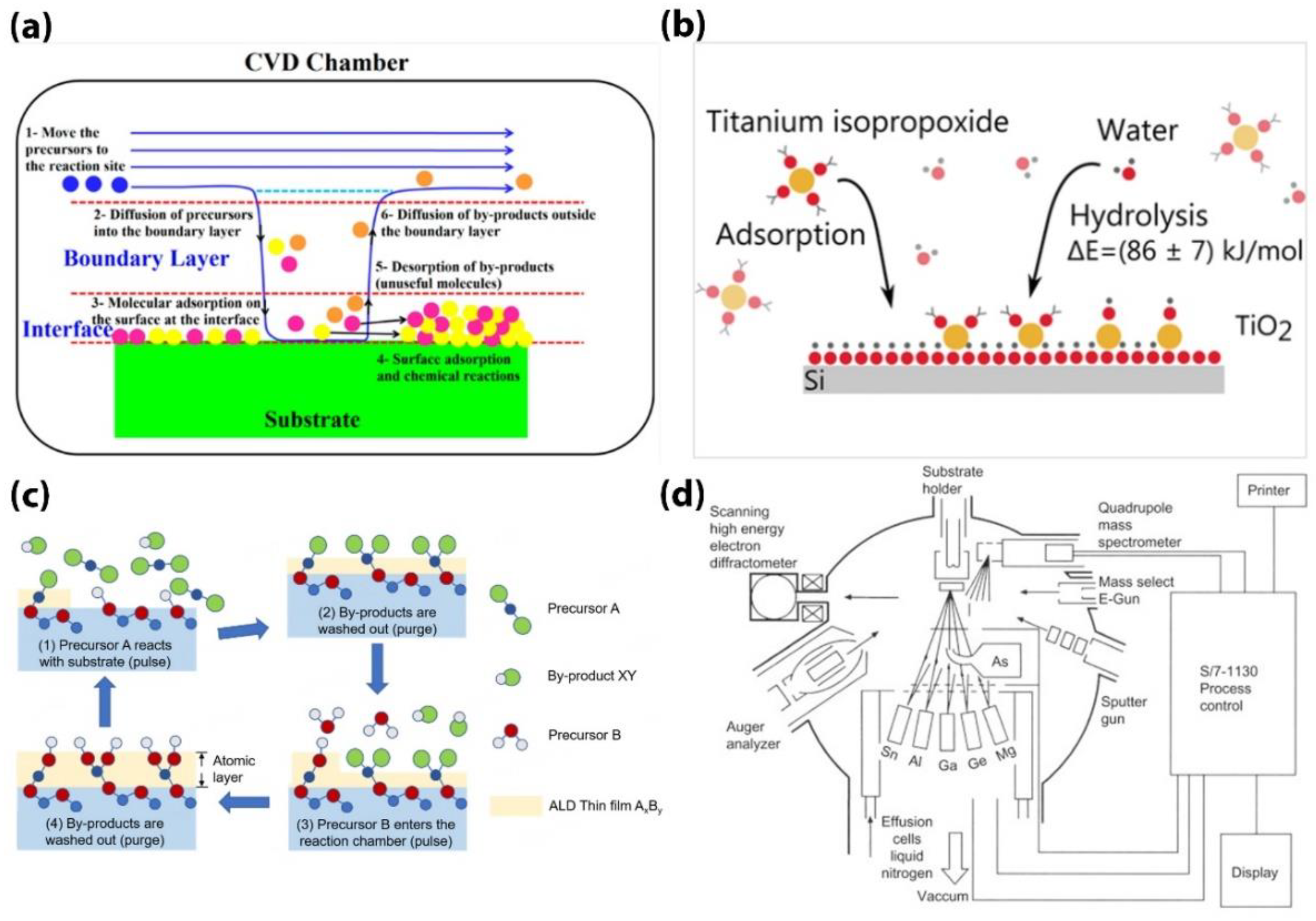

3. WBG Semiconductor Manufacturing

3.1. GaN and SiC Semiconductor Manufacturing Route

GaN Manufacturing Route

SiC Manufacturing Route

3.2. Innovations in WBG Semiconductor Manufacturing

4. Applications of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Semiconductors in Sustainable Technologies

5. Challenges and Future Prospects of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Semiconductors

Cost and Scalability

Material Availability and Sustainability

Integration with Existing Technologies

Ultrawide-Bandgap (UWBG) Materials

Long-Term Sustainability and Environmental Impact

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Yuvaraja, V. Khandelwal, X. Tang, and X. Li, “Wide bandgap semiconductor-based integrated circuits,” Chip, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 100072, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Prasad Bhupathi et al., “Investigation of WBG based Power Converters used in E-Transportation,” E3S Web of Conferences, vol. 552, p. 01145, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Chandran et al., “Solar-Driven Sustainability: III–V Semiconductor for Green Energy Production Technologies,” Nano-Micro Letters 2024 16:1, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–34, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Shenai, M. Bakowski, and N. Ohtani, “Foreword special issue on wide bandgap power switching devices for energy efficiency and renewable energy integration,” IEEE Trans Electron Devices, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 245–247, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Woo et al., “From wide to ultrawide-bandgap semiconductors for high power and high frequency electronic devices,” Journal of Physics: Materials, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 022003, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. S. Chaudhary, M. Denaï, S. S. Refaat, and G. Pissanidis, “Technology and Applications of Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Materials: Current State and Future Trends,” Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 6689, vol. 16, no. 18, p. 6689, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Forte and A. Spampinato, “High Power-Density Design Based on WBG GaN Devices for Three-Phase Motor Drives,” 2024 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, SPEEDAM 2024, pp. 65–70, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. ; H. Obdan, Y. Ye, T. Pajchrowski, A. Erken, and A. H. Obdan, “Examining the Optimal Use of WBG Devices in Induction Cookers,” Applied Sciences 2023, Vol. 13, Page 12517, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12517, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang et al., “(Invited) Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Based Devices for Digital and Industrial Applications,” ECS Trans, vol. 112, no. 2, p. 37, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. McDonald, “Power Conversion Semiconductor and Circuit Trends and Challenges for a Sustainable Energy Future,” Technical Digest - International Electron Devices Meeting, IEDM, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Krovi, P. Skarolek, and J. Bauer, “Comparison of Bi-Directional DC/DC Converter using Si and WBG Devices,” 2023 International Conference on Electrical Drives and Power Electronics, EDPE 2023 - Proceedings, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Vanhouche et al., “Environmental Analysis of RF Substrates,” 2024 Electronics Goes Green 2024+ (EGG), pp. 1–8, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Piner and M. W. Holtz, “(Invited) Heterogeneous Integration of Ultrawide Bandgap III-Nitrides and Diamond,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2023-02, no. 32, p. 1580, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ruberti, “Environmental performance and trends of the world’s semiconductor foundry industry,” J Ind Ecol, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. J. M. Lawley et al., “Geospatial Data and Deep Learning Expose ESG Risks to Critical Raw Materials Supply: The Case of Lithium,” Earth Science, Systems and Society, vol. 4, p. 10109, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Akyıldız, “The Importance of Silicon Metal on the Green Transition and the Role of Northern Countries in the Silicon Metal Market,” EGU24, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mei, Y. Geng, Z. Chen, S. Xiao, and Z. Gao, “Ensuring the sustainable supply of semiconductor material: A case of germanium in China,” Int J Prod Econ, vol. 271, p. 109231, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Semiconductor Market Size to Surpass USD 1,137.57 Billion by 2033.” Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/semiconductor-market.

- A. Machín, M. C. Cotto, F. Díaz, J. Duconge, C. Morant, and F. Márquez, “Environmental Aspects and Recycling of Solid-State Batteries: A Comprehensive Review,” Batteries 2024, Vol. 10, Page 255, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 255, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Dhivya and G. Premalatha, “E-Waste Challenges & Solutions,” Sustainable Management of Electronic Waste, pp. 255–275, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Jena, S. K. Mishra, and H. S. Moharana, “Challenges and way forward in the handling and disposal of battery waste: Towards sustainable practices,” Sustainable Social Development, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 2866, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Suresh et al., “Strategies for Carbon Footprint Reduction in Advancing Sustainability in Manufacturing,” https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/979-8-3693-3625-0.ch012, Jan. 1AD. [CrossRef]

- A. Fontana et al., “Enhancing the Sustainability of the Electronics in the Automotive Sector in the Context of Circular Economy Through a Decision-Making Framework,” IEEE Xplore, Jun. 2024, Accessed: Sep. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10631249.

- Ji. Seo, “Bridging Technology and Environment: Sustainable Approaches in Semiconductor Chemical Mechanical Planarization (CMP),” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2024-01, no. 20, p. 1272, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Esiri, O. A. Babayeju, I. O. Ekemezie, A. E. Esiri, O. A. Babayeju, and I. O. Ekemezie, “Implementing sustainable practices in oil and gas operations to minimize environmental footprint,” https://gsconlinepress.com/journals/gscarr/sites/default/files/GSCARR-2024-0207.pdf, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 112–121, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Reynolds, “Sustainable Supply Chain Practices- A Qualitative Investigation of Green Logistics Strategies,” Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Makprang, “SUSTAINABILITY IN SUPPLY CHAINS: STRATEGIES AND PRACTICES FOR A GREENER FUTURE,” RMUTT GLOBAL BUSINESS ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE REVIEW, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 85–108, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen and L. Gan, “Lenovo’s Green Supply Chain Management Framework for Green Development of Enterprises,” Frontiers in Business, Economics and Management, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 61–69, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Chaudhuri, B. Singh, A. K. Agrawal, S. Chatterjee, S. Gupta, and S. K. Mangla, “A TOE-DCV approach to green supply chain adoption for sustainable operations in the semiconductor industry,” Int J Prod Econ, vol. 275, p. 109327, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Feng, M. Qamruzzaman, S. S. Sharmin, and S. Karim, “Bridging Environmental Sustainability and Organizational Performance: The Role of Green Supply Chain Management in the Manufacturing Industry,” Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 5918, vol. 16, no. 14, p. 5918, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Vilochani, T. C. McAloone, and D. C. A. Pigosso, “Integration of sustainability into product development: insights from an industry survey,” Proceedings of the Design Society, vol. 4, pp. 1517–1526, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Aguayo-González et al., “Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Engineering: Products, Services, Technologies, and Social Inclusivity with a Gender Approach,” Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1888, vol. 16, no. 5, p. 1888, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Hayagan et al., “Challenges and Perspectives for Direct Recycling of Electrode Scraps and End-of-Life Lithium-ion Batteries,” Batter Supercaps, vol. 7, no. 6, p. e202400120, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Lingaitienė, A. Burinskienė, and V. Gružauskas, “Review of challenges to transition towards circular economy,” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 423–436, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Weiksnar, C. C. Ferraro, R. Kari, N. Mayer, and T. G. Townsend, “Opportunities and challenges with implementing a recycling program for municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) bottom ash as a construction aggregate: A programmatic review,” J Air Waste Manage Assoc, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Magni, M. Colledani, and G. Harper, “Editorial: The challenge towards more sustainable lithium ion batteries: from their recycling, recovery and reuse to the opportunities offered by novel materials and cell design,” Front Chem, vol. 12, p. 1421434, May 2024.

- J. M Kalyani, “Basics of Semiconductors,” International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 412–414, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Roy, C. Kumar Ghosh, S. Dey, and A. Kumar Pal, “Semiconductor Devices,” Solid State & Microelectronics Technology, pp. 249–279, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Venkatesh, Dr. S. Selvakumar, S. Dhasneem, and L. V. Kannan, “SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES: AN OVERVIEW,” Futuristic Trends in Electrical Engineering Volume 3 Book 1, pp. 11–37, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Fahlman, “Semiconductors,” Materials Chemistry, pp. 291–405, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Gachovska and J. L. Hudgins, “SiC and GaN Power Semiconductor Devices,” Power Electronics Handbook, pp. 87–150, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Lu, “A systematic analysis of wide band gap semiconductor used in power electronics,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 161–166, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Burgos, “Wide Bandgap Generation (WBGen): Developing the Future Wide Bandgap Power Electronics Engineering Workforce,” Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhan et al., “Effects of Thermal Boundary Resistance on Thermal Management of Gallium-Nitride-Based Semiconductor Devices: A Review,” Micromachines 2023, Vol. 14, Page 2076, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 2076, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Tran, “Thermal conductivity of wide and ultra-wide bandgap semiconductors,” vol. 2334, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Mitterhuber, B. Kosednar-Legenstein, A. Vohra, M. Borga, N. Posthuma, and E. Kraker, “Correlation of heat transport mechanism and structural properties of GaN high electron mobility transistors,” J Appl Phys, vol. 136, no. 4, p. 45108, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. M. Rodríguez-Benítez et al., “Recent Advance and Future Progress of GaN Power Semiconductor Devices Used in PV Module Integrated Converters,” Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Arseniuk and Y. Zinkovskyi, “MINIMIZING HIGH-FREQUENCY SWITCHING LOSSES IN WIDEBAND GAN HEMTS FOR FLYBACK CONVERTERS,” Information and Telecommunication Sciences, no. 2, pp. 53–60, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Glaser, P. Feuchter, and A. Díaz, “Looking beyond energy efficiency - Environmental aspects and impacts of WBG devices and applications over their life cycle,” 2023 25th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, EPE 2023 ECCE Europe, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Basu, “Brief history of semiconductor science and technology and India’s role in the decade after the invention of transistor,” Indian Journal of History of Science 2024 59:2, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 204–215, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. P. C. V. Bernardo, R. A. M. Lameirinhas, J. P. de Melo Cunha, and J. P. N. Torres, “A revision of the semiconductor theory from history to applications,” Discover Applied Sciences, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 1–59, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee et al., “The history and trends of semiconductor materials’ development,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2608, no. 1, p. 012019, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen and A. Q. Huang, “Extreme high efficiency enabled by silicon carbide (SiC) power devices,” Mater Sci Semicond Process, vol. 172, p. 108052, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Chi, “Technologies for Superior Reliability in SiC Power Devices,” 2023 China Semiconductor Technology International Conference, CSTIC 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Veliadis, “SiC Power Device Mass Commercialization,” European Solid-State Device Research Conference, vol. 2022-September, pp. 31–36, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. L. J. Petersen, “A History of Silicon Carbide (SiC) Wide Bandgap (WBG) Advancement through Power Electronic Building Blocks (PEBB) and Implications for the Future,” 2023 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium, ESTS 2023, pp. 362–368, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, H. S. Rizi, C. Chen, P. Liu, R. Yu, and A. Q. Huang, “An 800V/300 kW, 44 kW/L Air-Cooled SiC Power Electronics Building Block (PEBB),” IECON Proceedings (Industrial Electronics Conference), vol. 2021-October, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohanbabu, S. Maheswari, N. Vinodhkumar, P. Murugapandiyan, and R. S. Kumar, “Advancements in GaN Technologies: Power, RF, Digital and Quantum Applications,” Nanoelectronic Devices and Applications, pp. 1–28, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Gao, “Advancements and future prospects of Gallium Nitride (GaN) in semiconductor technology,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 37–44, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. M. A. Rajathi and B. R. Parveen, “A conceptual study on impact of green manufacturing practices,” Open Access Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 087–094, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Tyagi, S. Jilani, F. Talib, and M. Kumar, “A review of sustainable approach to smart manufacturing systems,” Smart Systems, pp. 34–52, Jun. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003495314-3/REVIEW-SUSTAINABLE-APPROACH-SMART-MANUFACTURING-SYSTEMS-PANKAJ-KUMAR-TYAGI-SHEEBA-JILANI-FAISAL-TALIB-MOHAN-KUMAR.

- R. G. Pungle, “Revolutionizing industry: the path to sustainable manufacturing,” International Journal of Engineering & Technology, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 167–172, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Khang and S. Akhai, “Green Intelligent and Sustainable Manufacturing : Key Advancements, Benefits, Challenges, and Applications for Transforming Industry,” Machine Vision and Industrial Robotics in Manufacturing, pp. 405–417, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- U. U. Mamudu et al., “Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Digital transformation and sustainable practices,” International Journal of Science and Research Archive, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 129–141, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. F. I. Abdillah, T. C. Kao, S. J. You, and Y. F. Wang, “Non-methane hydrocarbons from integrated semiconductor manufacturing processes: Assessments of chemical footprints, emissions factors, and treatment efficiency,” J Clean Prod, vol. 434, p. 140408, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Kumar, Mahesh. M. Kawade, G. K. Bharti, and G. Laxmaiah, “Implementation of Intelligent CPS for Integrating the Industry and Manufacturing Process,” AI-Driven IoT Systems for Industry 4.0, pp. 273–288, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Paliwal, A. Sikdar, and Z. Kachhi, “Integration of Advanced Technologies for Industry 4.0,” AI-Driven IoT Systems for Industry 4.0, pp. 114–142, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Krishna Pasupuleti, “Smart Industry 4.0: Transformative Innovations and Advanced Technologies,” Transformative Innovations in Smart Manufacturing, pp. 119–133, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Rizonildo, A. De Sousa, D. Barbosa De Alencar, J. C. Leite, H. Andrade, and S. Júnior, “Integration of Industry 4.0 technologies in industrial manufacturing processes,” Revista de Gestão e Secretariado, vol. 15, no. 7, p. e3844, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Citation Moch, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Its Impacts on Production Processes and Efficiency Enhancements Through Automation and Data Networking,” East African Journal of Business and Economics, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 370–378, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Vangeri et al., “Green Supply Chain Management in Eco-Friendly Sustainable Manufacturing Industries,” https://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/979-8-3693-3625-0.ch010, pp. 253–287, Jan. 1AD. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Zorpas, “The hidden concept and the beauty of multiple ‘R’ in the framework of waste strategies development reflecting to circular economy principles,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 952, p. 175508, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. S and K. K, “An EOQ Model for Circularity Index with Waste Minimization and Reduced Emission in Electrical and Electronic Equipment,” Contemporary Mathematics, pp. 3002–3037, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu et al., “Low temperature epitaxial technology for GaN-based materials,” Chinese Science Bulletin, vol. 68, no. 14, pp. 1762–1776, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Bera, “Microwave High Power High Efficiency GaN Amplifiers for Communication,” vol. 955, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Nishimura and T. Kachi, “Simulation of channeled implantation of magnesium ions in gallium nitride,” Applied Physics Express, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 116502, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Blevins, “Development of a World Class Silicon Carbide Substrate Manufacturing Capability,” IEEE Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 539–545, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, D. Sheng, Y. Yang, Z. Zhang, W. Wang, and H. Li, “Wafer-Scale p-Type SiC Single Crystals with High Crystalline Quality,” Cryst Growth Des, vol. 24, no. 13, pp. 5686–5692, Jul. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.CGD.4C00486/SUPPL_FILE/CG4C00486_SI_001.PDF. [CrossRef]

- F. Roccaforte, P. Fiorenza, M. Vivona, G. Greco, and F. Giannazzo, “Selective Doping in Silicon Carbide Power Devices,” Materials 2021, Vol. 14, Page 3923, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 3923, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang et al., “High quality and wafer-scale cubic silicon carbide single crystals,” Apr. 2023, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.09065v1.

- A. Hochreiter, F. Groß, M.-N. Möller, M. Krieger, and H. B. Weber, “Electrochemical etching strategy for shaping monolithic 3D structures from 4H-SiC wafers,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pearton, “Electronic properties of dopants and defects in widegap and ultra-widegap semiconductors and alloys,” Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Madyaningarum et al., “Chemical Processing Development for Radioactive Minerals Processing Facility: A Circular Economy Model,” Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1049–1056, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Luo et al., “Recycling potential of secondary zinc materials,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2738, no. 1, p. 012022, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Rathi, D. B. Sabale, and M. S. Kaswan, “Circular Economy for Indian Manufacturing Industry,” AIP Conf Proc, vol. 2986, no. 1, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Colangelo, “Reducing the environmental footprint of glass manufacturing,” Int J Appl Glass Sci, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 350–366, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Sabzi et al., “A Review on Sustainable Manufacturing of Ceramic-Based Thin Films by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): Reactions Kinetics and the Deposition Mechanisms,” Coatings 2023, Vol. 13, Page 188, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 188, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Reinke, Y. Kuzminykh, and P. Hoffmann, “Low temperature chemical vapor deposition using atomic layer deposition chemistry,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 1604–1611, Mar. 2015. https:// 10.1021/CM504216P/ASSET/IMAGES/MEDIUM/CM-2014-04216P_0008.GIF.

- B. Yu, J. Zhang, Y. Yang, D. Yu, Y. Mai, and X. Chen, “Influences of deposition conditions on atomic layer deposition films for enhanced performance in perovskite solar cells,” Energy Mater 2024;4:400045., vol. 4, no. 4, p. N/A-N/A, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Adachi and K. Wasa, “Thin Films and Nanomaterials,” Handbook of Sputter Deposition Technology: Fundamentals and Applications for Functional Thin Films, Nano-Materials and MEMS: Second Edition, pp. 3–39, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. F. I. Abdillah, T. C. Kao, S. J. You, and Y. F. Wang, “Non-methane hydrocarbons from integrated semiconductor manufacturing processes: Assessments of chemical footprints, emissions factors, and treatment efficiency,” J Clean Prod, vol. 434, p. 140408, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Luo, M. Gu, Q. Quan, Z. Jiang, and C. Wang, “Strategies for Managing Perfluorinated Compounds (PFCs) in Semiconductor Manufacturing: A Supply Chain and Public Management Approach,” Transactions on Engineering and Technology Research, vol. 2, pp. 76–85, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. C. Obiuto et al., “Chemical management in electronics manufacturing: Protecting worker health and the environment,” https://wjarr.com/sites/default/files/WJARR-2024-0648.pdf, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 010–018, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Matin, M. R. Islam, X. Wang, H. Huo, and G. Xu, “AIoT for sustainable manufacturing: Overview, challenges, and opportunities,” Internet of Things, vol. 24, p. 100901, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. D. W. Praveenraj, T. Vijayaraj, K. S. Kumar, N. K. Sakthivel, F. Multani, and P. Nagaveni, “Advanced Technological Improvements in Making of Smart Production Using AI and ML,” 2024 4th International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering, ICACITE 2024, pp. 178–183, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Alfred, N. Chinthamu, T. Jayanthy, E. Muniyandy, T. K. Dhiman, and T. Nimmy John, “Implementation of advanced techniques in production and manufacturing sectors through support vector machine algorithm with embedded system,” Measurement: Sensors, vol. 33, p. 101119, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Bhambri, S. Rani, and A. Khang, “AI-driven Digital Twin and Resource Optimization in Industry 4.0 Ecosystem,” Intelligent Techniques for Predictive Data Analytics, pp. 47–69, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Todescato et al., “Sustainable manufacturing through application of reconfigurable and intelligent systems in production processes: a system perspective,” Scientific Reports 2023 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “How is AI Transforming the Semiconductor Industry- Birlasoft.” Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.birlasoft.com/articles/ai-semiconductor-industry-use-cases-and-benefits.

- Y. Yu, D. Ma, and Y. Wang, “Structural resilience evolution and vulnerability assessment of semiconductor materials supply network in the global semiconductor industry,” Int J Prod Econ, vol. 270, p. 109172, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, W. Yang, Z. Zhao, S. Wang, and G. Q. Huang, “Do fairness concerns matter for ESG decision-making? Strategic interactions in digital twin-enabled sustainable semiconductor supply chain,” Int J Prod Econ, vol. 276, p. 109370, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. O. Paul, J. O. Ogugua, and N. L. Eyo-Udo, “Sustainable procurement practices: Balancing compliance, ethics, and cost-effectiveness,” International Journal of Scientific Research Updates, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 027–036, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Artudean, N. Aitonean, M. Parcalab, D. C. Popa, and L. Szabo, “Strategic Resource Challenges in the Development of Smart Cities,” 2024 24th IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics, AQTR 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Ogunsuji, O. R. Amosu, D. Choubey, B. E. Abikoye, P. Kumar, and S. C. Umeorah, “Sourcing renewable energy components: building resilient supply chains, reducing dependence on foreign suppliers, and enhancing energy security,” https://wjarr.com/sites/default/files/WJARR-2024-2297.pdf, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 251–262, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Ala-Lahti, “The awkward relations between EU innovation policies and environmental law,” Rev Eur Comp Int Environ Law, 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Creating Future-Ready Devices with SiC and GaN - Power Electronics News.” Accessed: Sep. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.powerelectronicsnews.com/creating-future-ready-devices-with-sic-and-gan/.

- 107. K.-Y. Lee, “Analysis of the various SiC power MOSFETs,” pp. 1–1, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Di Giovanni, “Silicon Carbide: Physics, Manufacturing, and Its Role in Large-Scale Vehicle Electrification,” Chips 2023, Vol. 2, Pages 209-222, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 209–222, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Qamar and H. Qamar, “Performance Improvement of SiC Based Electric Vehicle Charger with an Advanced PWM Method,” 2024 IEEE 25th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics, COMPEL 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Di Paolo Emilio, “Silicon Carbide Devices,” pp. 143–163, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Shanbhag, S. B. Shenoy, A. Sahoo, V. Paquinadin, N. Sam K, and J. Bodireddy, “Design and Implementation of GaN-Based DC-DC Converter for Solar Application in a DC Microgrid,” 2024 International Conference on Signal Processing, Computation, Electronics, Power and Telecommunication, IConSCEPT 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Abu-Siada and S. M. Islam, “Applications of Power Electronics in Renewable Energy Systems,” Power Electronics Handbook, pp. 797–843, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Xiao, “Application of Power Electronics Technology in Renewable Energy Systems,” Stud Soc Sci Res, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 157, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Cheng, “Application of Power Electronics Converters in Renewable Energy,” Journal of Electronic Research and Application, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 101–107, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. A. Adenekan, C. Ezeigweneme, and E. G. Chukwurah, “Driving innovation in energy and telecommunications: next-generation energy storage and 5G technology for enhanced connectivity and energy solutions,” International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 1581–1597, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Akbari, R. Bolla, R. Bruschi, F. Davoli, C. Lombardo, and B. Siccardi, “A Monitoring, Observability and Analytics Framework to Improve the Sustainability of B5G Technologies,” 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), pp. 969–975, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Renga, M. Ni, M. A. Marsan, and M. Meo, “Network Sharing to Enable Sustainable Communications in the Era of 5G and beyond,” IEEE International Conference on Communications, pp. 2840–2846, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Cascino et al., “Innovative Solutions to Make Driving Safer, Greener and More Connected,” 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements and Networking, M and N 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Davies, A. D. Johnson, R. I. Pelzel, M. D. Geen, A. M. Joel, and S. W. Lim, “MOVPE and its future production challenges,” J Cryst Growth, vol. 605, p. 127031, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Sadath, D. Mehrotra, and A. Kumar, “Scalability in Blockchain - Hyperledger Fabric and Hierarchical Model,” 2022 IEEE Global Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies, GlobConPT 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Mukherjee, D. Pal, A. Bhattacharyya, and S. Roy, “Future of the Semiconductor Industry,” Handbook of Semiconductors, pp. 359–374, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Ghasemi, A. Taimouri, and A. Sayadi, “The Prospects of Future Production: An Arena for Emerging New Strategies and Policies of Manufacturing–The Household Appliance Industry’s Review,” International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 12, no. 6, p. p203, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Teixeira, A. Mateus, and M. C. Brito, “Challenges to the Implementation of a Large-Scale Green Hydrogen Economy: Raw Materials Requirements, Technological Drivers, and Energy Policy Tasks,” SSRN, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Tan et al., “Toward Sustainable Ultrawide Bandgap van der Waals Materials: An ab initio Screening Effort,” Adv Funct Mater, vol. 34, no. 11, p. 2308679, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Ashby, “Materials and Sustainable Development, Second Edition,” Materials and Sustainable Development, Second Edition, pp. 1–565, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. He, D. R. Keith, H. C. Kim, R. De Kleine, J. Anderson, and M. Doolan, “Materials Challenges in the Electric Vehicle Transition,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 58, no. 28, pp. 12297–12303, Jul. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.EST.3C09042/SUPPL_FILE/ES3C09042_SI_001.PDF. [CrossRef]

- O. Oguntona, O. Akinradewo, O. Mokono, B. F. Ogunbayo, and C. Aigbavboa, “Limitations of Futuristic Building Materials for Achieving Sustainability in the Construction Industry,” Sustainable Construction in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, vol. 107, no. 107, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Tolusso, L. Mascheretti, and F. Marzullo, “Innovative Value Chains: Advancements in Critical Raw Materials Recovery from E-Waste for Europe’s Economic Resilience,” International Conference Electronics Goes Green 2024+: From Silicon to Sustainability, EGG 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Siddiqua, S. Das Kumar, C. N. Mulligan, and R. Haigh, “A Decade Review of Research Trends Using Waste Materials in the Building and Construction Industry: A Pathway towards a Circular Economy,” Waste 2023, Vol. 1, Pages 935-959, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 935–959, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Okogwu et al., “EXPLORING THE INTEGRATION OF SUSTAINABLE MATERIALS IN SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT,” Engineering Science & Technology Journal, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 49–65, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Salazar, I. Yakoumis, M. L. Grilli, D. Salazar, I. Yakoumis, and M. L. Grilli, “Substitution and Recycling of Critical Raw Materials in Optoelectronic, Magnetic and Energy Devices III,” physica status solidi (a), vol. 219, no. 15, p. 2200259, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Malest and M. R. Gabor, “Critical Raw Material in Circular Economy Context for Europe: A Decision Tree and Two-Step Cluster Analysis Approach,” Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 926 LNNS, pp. 375–388, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Toumi, “Characteristics and modeling of wide band gap (WBG) power semiconductor,” Power Electronics for Next-Generation Drives and Energy Systems: Converters and control for drives, pp. 1–40, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. V. Suman, A. S. Priya, G. M. A. Priyadarshini, K. Krishnamraju, A. Gangadhar, and M. Hema, “Integration Challenges and Opportunities for Gate-All-Around FET (GAA FET) in Next-Generation Electronic Devices,” vol. 112, pp. 1361–1368, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Chery, C. Fohn, J. De Messemaeker, and E. Beyne, “(Invited) Reliability Challenges in Advanced 3D Technologies,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2023-02, no. 17, p. 1188, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, X. Yuan, J. Wang, B. Hu, X. Yin, and Z. J. Shen, “Optimization of Power Sharing and Switching Frequency in Si/WBG Hybrid Half-Bridge Converters Using Power Loss Models,” IEEE J Emerg Sel Top Power Electron, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 2837–2849, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. H. Luo, X. Cheng, Y. B. Rao, J. A. Han, X. J. Deng, and B. Bin Cheng, “A W-band Hybrid Vector-modulated and Reflective-type Phase Shifter in 130-nm SiGe BiCMOS,” 2024 Photonics and Electromagnetics Research Symposium, PIERS 2024 - Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Lyons, D. Wickramaratne, and A. Janotti, “Dopants and defects in ultra-wide bandgap semiconductors,” Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci, vol. 30, p. 101148, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Porter, Y. Ma, Y. Qin, and Y. Zhang, “P-Type Doping Control of Magnetron Sputtered NiO for High Voltage UWBG Device Structures,” 2023 IEEE 10th Workshop on Wide Bandgap Power Devices and Applications, WiPDA 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Fu, “(Invited) Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Homo- and Hetero-P-N Junctions,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2024-01, no. 32, p. 1576, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Voss, “(Invited) Wbg and Uwbg Photoconductors and Applications,” ECS Meeting Abstracts, vol. MA2024-01, no. 32, p. 1566, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song and Y. Dong, “Influence of resource compensation and complete information on green sustainability of semiconductor supply chains,” Int J Prod Econ, vol. 271, p. 109227, May 2024. [CrossRef]

| Sustainability Practice | Description | Impact on Recycling | Impact on Energy Consumption | Impact on Waste Reduction | Toxic By-product Elimination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Energy Epitaxial Growth | Reduces energy required in the deposition of semiconductors | Low | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Green Chemistry in Manufacturing | Utilizes environmentally friendly chemicals to replace harmful substances in production processes | Low | Moderate | High | High |

| Closed-Loop Recycling Systems | Recovers and reuses materials from semiconductor production waste (e.g., silicon wafers, gallium). | High | Low | High | Moderate |

| Reduction of Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) | Innovating CVD processes to minimize toxic emissions and lower energy demands | Low | High | Low | High |

| Recycling of Semiconductor Materials | Implements strategies for reclaiming materials like silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) | High | Low | High | Low |

| Advanced Wastewater Treatment | Integrates new filtration technologies to treat and reuse wastewater from production facilities | Low | Low | High | High |

| Energy Efficiency Measures | Incorporates energy-efficient equipment and renewable energy sources to power semiconductor production lines | Low | High | Moderate | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).