1. List of acronymic and symbols

air: Air

ARC: Ames Research Center

arc: Electrical arc column

ar: Argon

CFD: Computational Fluid Dynamics

CuO: Cupric oxide (black copper oxide)

Cu₂O: Cuprous oxide (red copper oxide)

D: Diameter of Standard Probe

Di: Diffusion coefficient of the i-th species

EB: Energy Balance

γ: Catalytic efficiency

γN: Catalytic efficiency for the N + N → N₂ reaction

γO: Catalytic efficiency for the O + O → O₂ reaction

H⁰: Reservoir enthalpy

hi: Enthalpy of the i-th species

IHF: The Interaction Heating Facility

k: Mixture thermal conductivity

kv,i: Vibrational conductivity of bi-atomic species

LIF: Laser Induced Fluorescence

ṁ: Flow rate

Ns: Number of chemical species

Nvib: Number of chemical species with vibrational energy mode

P⁰: Reservoir pressure

ps: Probe stagnation pressure

PWT: Plasma Wind Tunnel

q: Total heat flux

qc: Convective (roto-translational) heat flux

qd: Diffusive (chemical) heat flux

qr: Radiative heat flux

qs: Probe stagnation wall heat flux

qv: Vibrational heat flux

RA: Specific gas constant for species A

ρ: Density

ρw: Wall density

ST: Sonic Throat

T: Temperature

Tw: Wall temperature

Tvib,i: Vibrational temperature of the i-th vibrational species

TPS: Thermal Protection Systems

U: Uncertainty

v: Velocity

x: Distance of probe from the nozzle exit section

Yi: Mass fraction of the i-th species

YA,w Mass fraction of species A at the wall

|MA| Total flux of atoms impinging the surface

|MA↓| Flux of atoms that recombine at the surface

2. Introduction

A crucial condition to replicate during tests at the arc-jet facility is the flow enthalpy, along with stagnation pressure, velocity gradients, and the chemical composition of the flow. These parameters are essential for accurately simulating the actual re-entry environment. In the test section, the enthalpy peaks along the centerline, gradually decreases toward the inner region, and sharply drops near the walls. Tests are primarily conducted in the core region, where flow properties change more slowly [

1]. The enthalpy in this region, often referred to as centerline or core enthalpy, should match flight conditions. Conversely, mass-averaged enthalpy accounts for the enthalpy of the entire stream, including the cooler regions near the water-cooled walls. Given the proportional relationship between enthalpy and heat transfer, any variations in enthalpy will affect the performance of the tested heatshield materials. Two experimental techniques are commonly used to measure mass-averaged enthalpy: the heat balance method [

2,

3], which divides net power input by mass flow rate, and the sonic throat method [

4], which relates enthalpy to flow rate and reservoir pressure. For centerline enthalpy determination, the heat transfer method is the standard, measuring heat transfer at the stagnation point of a calibration probe. Of course, the heat transfer-based methods are highly dependent on the type of probe used [

5,

7]. Probes with identical dimensions and material, like oxygen free high conductivity copper, but equipped with different sensing elements can yield varying heat flux measurements [

8]. Flow-ingestion probes have often been proposed for measuring the enthalpy of the flow and can be considered a valid alternative to flow-impact probes. These provide a more direct measurement of the enthalpy of the acquired gas sample, achieved through a dual energy balance. However, such probes require a specific calibration process, which depends heavily on the specific operating conditions [

9]. Particularly in low-pressure conditions, uncertainties become significant due to the difficulty in sampling a substantial amount of gas [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Alternative techniques, such as optical spectrometry or laser-induced fluorescence [

14,

15,

16], are very valuable non-invasive methods but are very challenging to implement, and LIF is not yet available for Scirocco, the 70MW Plasma Wind Tunnel at the Italian Aerospace Research Center. Recent advancements in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) may allow for precise reconstructions of test conditions [

17,

20], including enthalpy and thermal loads, but the most significant limitation is the lack of accurate knowledge of the catalytic recombination coefficient, γ [

21,

22,

23]. Various experimental estimates for the catalytic efficiency of copper and copper oxide, for both nitrogen and molecular oxygen, are reported in the literature. Unfortunately, these estimates differ by as much as an order of magnitude [

23], which can lead to significantly different predictions of heat fluxes and, consequently, the total enthalpy of the flow.

The enthalpy characterization performed on Scirocco PWT in this work, revealed significant discrepancies between experimental and numerical heat flux values, prompting a deeper investigation into the numerical models used up until now, particularly on the conservative assumption of fully catalytic walls.

Moreover, no systematic comparison between experimental and numerical enthalpy estimations methodologies has been done for Scirocco [

25,

26]. Park [

15] was the first to propose a comparative analysis of enthalpy determination methods, conducting an in-depth study of various techniques for a single operating point on the IHF facility. This work draws inspiration from Park’s study and try to replicate some of his findings on the Scirocco facility, with some significant differences, attributable to the varying facility performance. In this study, three currently feasible experimental methods were applied to the different operational conditions of the Scirocco arc-jet facility in nozzle C configuration: the sonic throat method, the heat balance method, and the heat transfer method. These methods were compared with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) solutions, where the inclusion of an estimated partial catalytic effect on the copper probe surface enhanced the agreement between numerical and experimental enthalpy and heat flux predictions, providing a clearer understanding of the test environment. The comparison of the available methodologies was carried out over a broader range of stagnation heat flux and enthalpy levels.

3. Facility Operating Conditions

Efforts are focused on the Scirocco Plasma Wind Tunnel, specifically under various operating conditions in the nozzle C configuration (a conical nozzle with a half-angle of 10° and an exit diameter of 90 cm, yielding a geometric area ratio of 144). For this configuration, both a robust set of experimental data and CFD reconstructions are available, as shown in

Table 1. Characterization was performed by incrementally increasing heat flux and total enthalpy over a relatively narrow stagnation pressure range of 27.9–62.0 mbar. The typical exposure time in these experiments is constant from test to test, in order of 4-6 seconds, taken after the steady-state heat flux of the oxidized surface is reached.

It’s important to take note of the chain uncertainty of all the devices observed; each field instrument is connected to the Local Control Unit that transmits the signal to the Data Acquisition System; this system has a measurement uncertainty Type B equal to 0.1% of Full Scale for each device. This last uncertainty source can in this case be considered negligible compared to the instrumental uncertainty, as it falls within the range of the instrumental error. Following, the detailed methodologies for calculating enthalpy values and their associated uncertainties are presented.

4. Enthalpy Measurement and Rebuilding

As previously mentioned, when discussing the enthalpy of the test flow, reference is generally made to two types of enthalpies: mass-averaged enthalpy and centerline (core) enthalpy. For the estimation of mass-averaged enthalpy, the sonic throat method and the energy balance method are used, while for the centerline total enthalpy determination the heat transfer method is employed, which represent the standard characterization method in Scirocco. Details regarding the methodologies and the uncertainty estimation will be provided below.

4.1. Mass-Averaged Enthalpy Measurement

4.1.1. Sonic throat method

The sonic throat method, is based on the relation between the mass-averaged total enthalpy and the cross-sectional area of the throat in m

2, the total pressure in the arc heater in Pa and the air mass flow rate injected in the column in kg/s. The assumption of isentropic expansion under thermodynamic equilibrium is explicit in the formulation of the sonic flow method, and a correction for frozen species is applied above enthalpy levels by Winovich over the enthalpy range between 1000 and 10,000 Btu/lbm (equivalently 2.3 to 23 MJ/kg). The equation is:

Despite these limitations, only simple state measurements are required for this method.

The instruments used in the measurements are an absolute pressure transducer and an air flow meter, listed in

Table 2, along with other instruments and the uncertainties specified by the manufacturers.

As calculated, the total instrumental percentage uncertainty is . However. Furthermore, a linear interpolation of the data has been calculated. The available data do not fit well with a linear regression model given the instrumental uncertainty of only 0.253%. In order to fit the available data with a linear regression, the average percentage error relative to the regression line is approximately 8.86%. It is important to note that such models are designed to provide an approximate estimate of the mean enthalpy value; however, they are presented here for the sake of completeness.

4.1.2. Energy Balance Method

The indirect measurement of the mass-averaged total enthalpy (

) of the Scirocco plasma flow is performed through the Energy Balance in a relatively simple way: by dividing the net power input by the mass flow rate in a so-called Energy Balance Method [

3]. In this case, the

is measured by dividing the total power input into the flow by the total mass flow rate of the test gas. The total power input is the electrical power provided to the electrodes minus the power losses in the cooling circuits. The relation that explains this methodology is reported below:

Below is a list of the quantities involved:

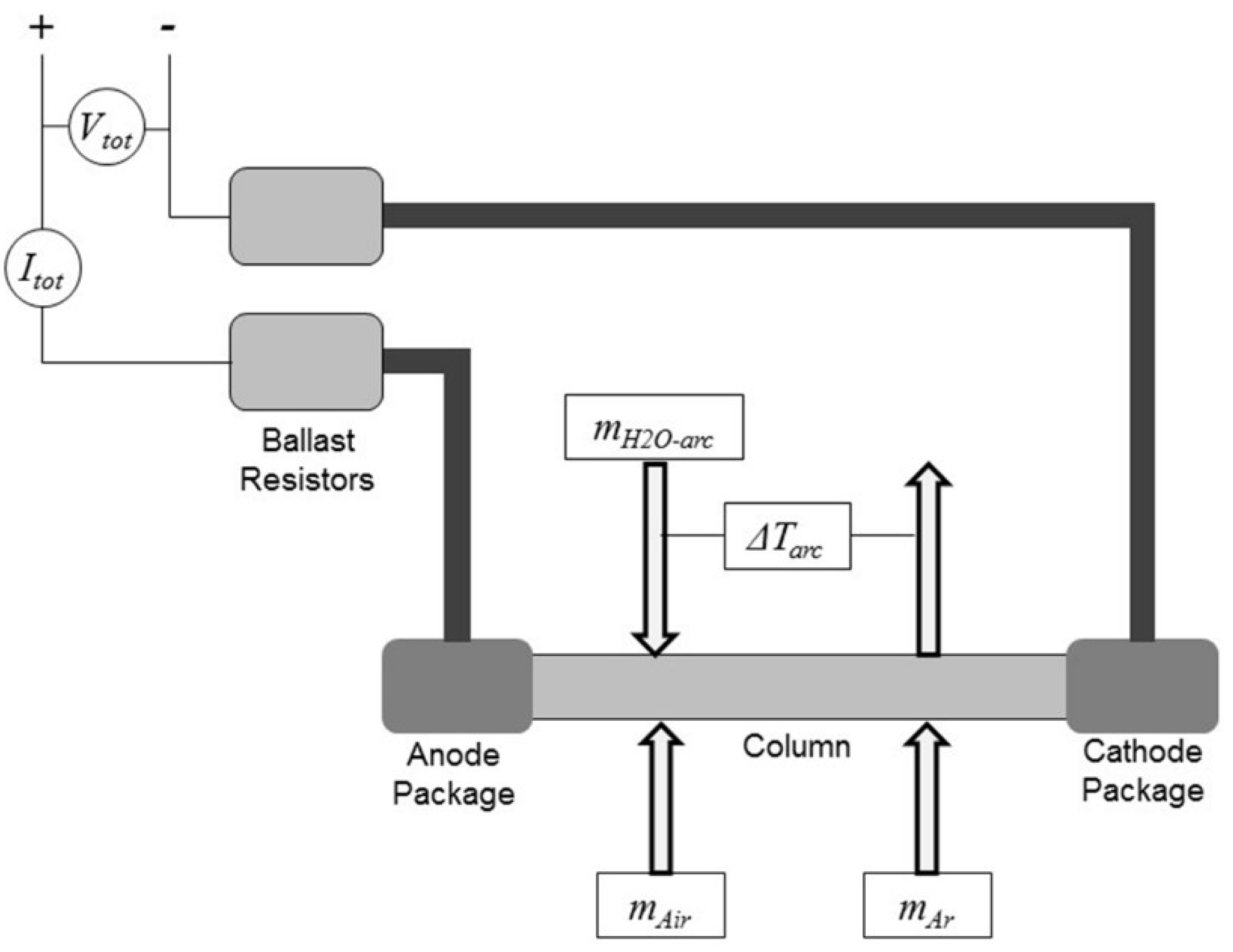

is the voltage of the Power Supply System between anode and cathode bar, V;

is the electrical current of the Power Supply System of the anode bar, A;

is the water flow rate of the arc heater cooling system, (m3/h);

is the delta-temperature of the water-flow of arc heater cooling system, (K);

is the air mass-flow rate of the arc heater complex, (kg/s);

is the argon mass-flow rate of the arc heater complex, (kg/s);

Figure 1 should help to clarify the measurement scheme:

The explicit formula for calculating the uncertainty via error propagation is not reported here for brevity, and overall uncertainty is approximately ±10.2% of the value of H0. For this level of error, the data fit a linear regression. This is a high value and the greatest weight on this result is determined by the differential thermopile for the measurement of (82.93% of the uncertain weight). The strong dependence on the temperature difference measured in the cooling water represents the main limitation of this methodology.

4.2. Centerline Enthalpy Measurement - Heat Transfer Method

In the Scirocco facility, the standard methodology for directly measuring enthalpy through thermal flux is the heat transfer method, which correlates the stagnation-point heat flux measured on the probe with the flow enthalpy.

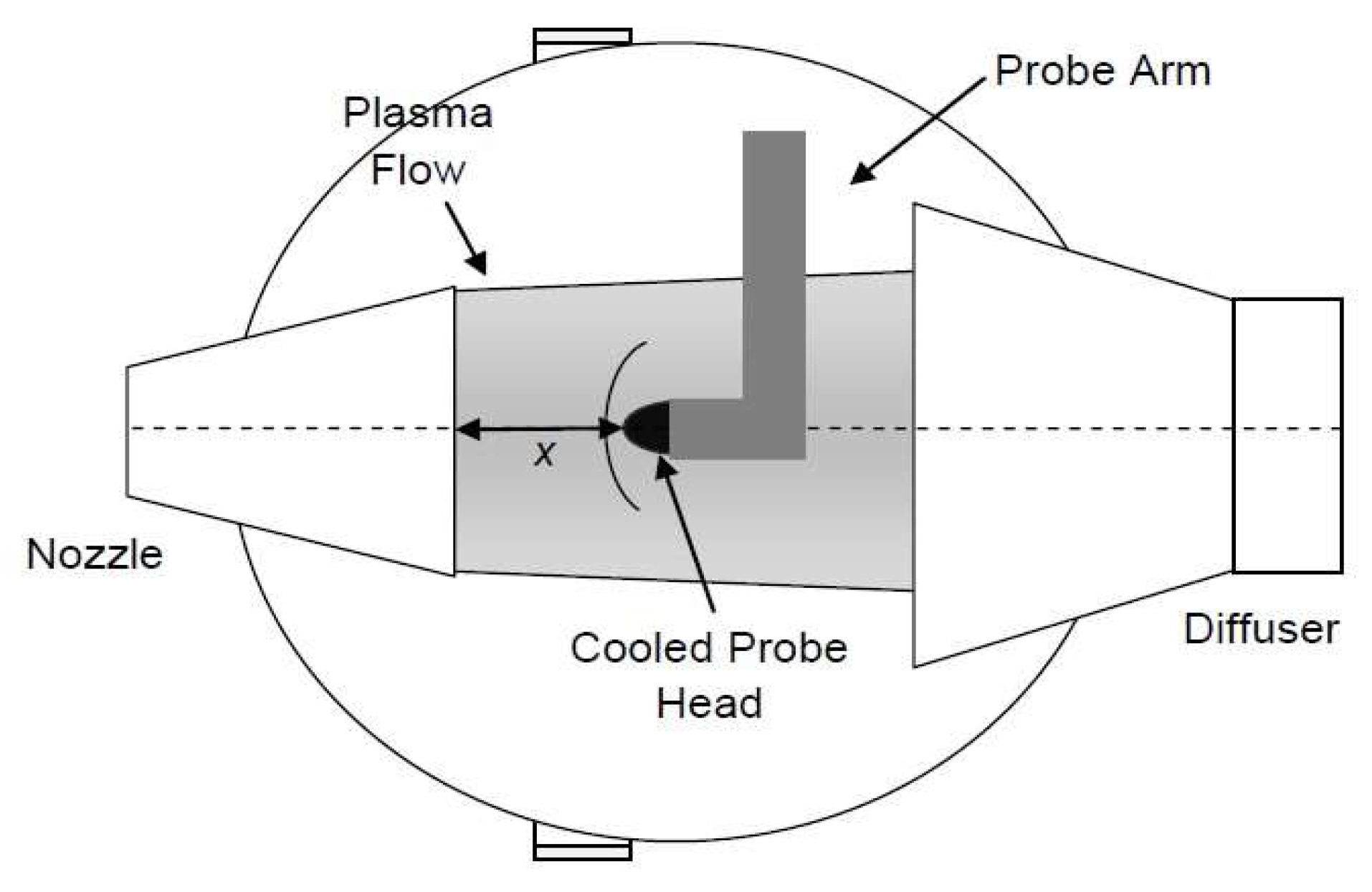

The experimental setup is sketched in

Figure 2. The distance from the nozzle throat to the probe position was x=2.8 m.

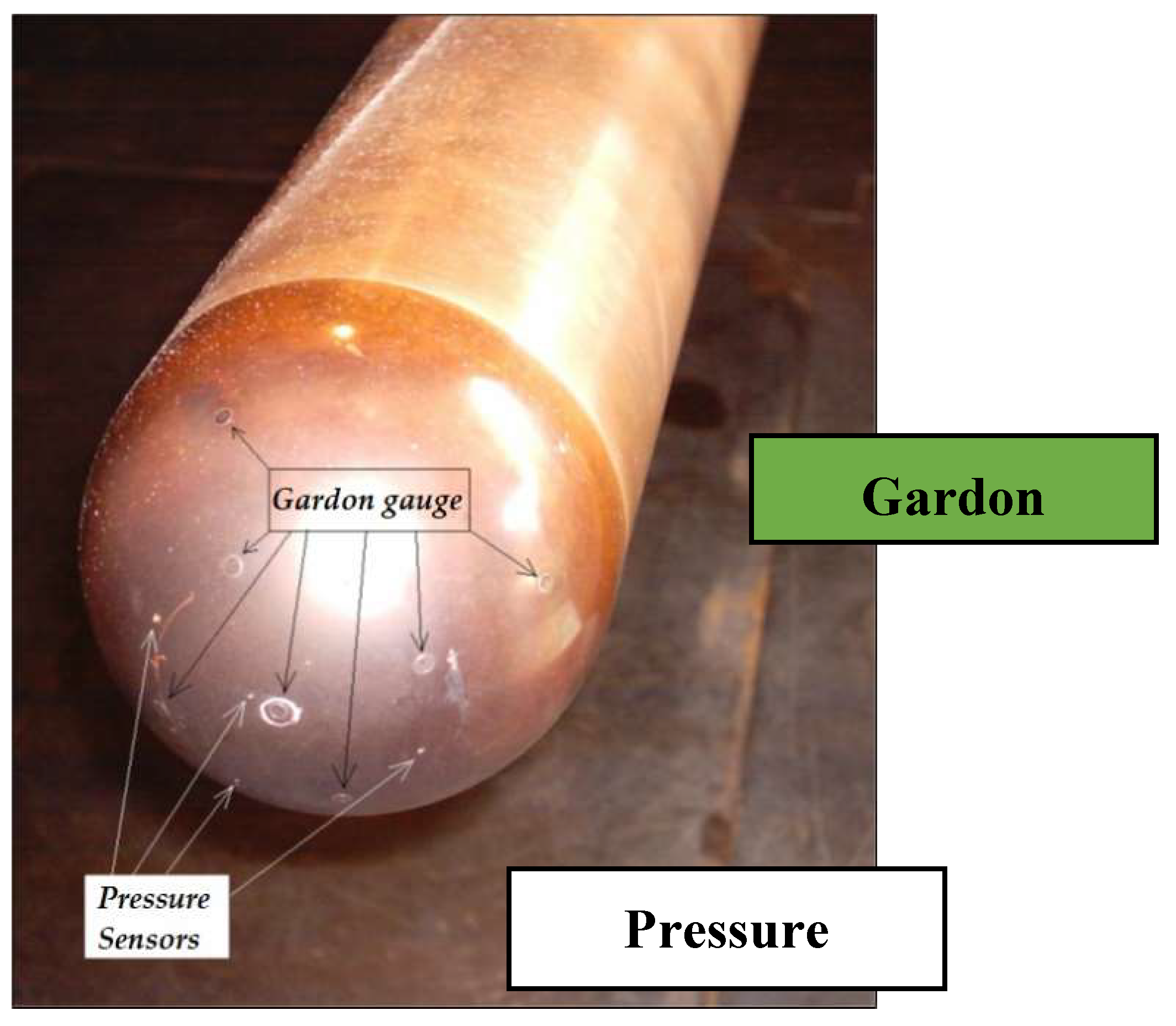

The stagnation heat flux and pressure are measured using a water-cooled copper probe (

Figure 3) of diameter

D=10 cm injected at a distance of

cm from the nozzle exit section in correspondence with the jet centerline. In the case of the Scirocco system the stagnation enthalpy in centerline of the flow is measured using a Gardon Gauge from Medtherm [

27] model GT-100-8-658/756A, with an operating range of 0-3000 kW/m

2 and expanded uncertainty of ±3%, which provides a "direct" measurement of the heat flux at the stagnation point, of course affected greatly by the possible copper surface catalytic recombination of oxygen and nitrogen atoms. The basic Gardon Gauge design is based on a differential copper-constantan type thermocouple. A thin constantan disk membrane is soldered to a body made of copper. The copper part is embedded into the copper probe and cooled through forced convection of high-pressure water.

Table 3.

Heat transfer constant for gases mixture [

22].

Table 3.

Heat transfer constant for gases mixture [

22].

| Gas |

|

| |

lbm |

g |

| Air |

0.0461 |

0.1235 |

| Argon |

0.0651 |

0.1744 |

The Gardon gauges are equipped with control thermocouples that measure their operating temperature, which typically averages around 370 K. This value will be used as a wall boundary condition in CFD calculations. The Enthalpy is calculated from the cold wall heat flux using the Fay-Riddle formulation, in the semi empirical and simplified formulation given by Zoby [

26,

27], for a mixture of air and argon:

In this formulation, the error is essentially dominated by the uncertainty in the measurement of the stagnation heat flux

, thus leading to total uncertainty of about ±3.02% [

27,

28].

The Fay-Riddell model, as is well known, assumes either equilibrium or fully catalytic conditions, meaning that the gas composition near the surface adjusts to the local thermodynamic state or promotes complete recombination of dissociated species, thereby increasing the heat flux due to exothermic reactions. In contrast, Goulard [

21] provides an alternative relation between stagnation point heat flux and enthalpy by assuming frozen conditions, where the gas composition remains unchanged as it approaches the surface, with an assigned catalytic recombination coefficient

, leading to a lower heat flux. As demonstrated by Park [

15], in his application, the two formulations converge for a

value of 0.04 for pure copper and oxygen recombination, at which point both models yield the same result.

4.3 Centerline Enthalpy Measurement – CFD rebuiling

The in-house developed CFD solver, NExT, has been used to numerically simulate the Scirocco tests. This CFD tool solves the Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations on a multi-block structured grid [

29], adopting a density-based finite volume approach, with a cell centered Flux Difference Splitting (FDS) upwind [

30] scheme for the convective terms. Second order formulation is obtained by means of an Essentially Non-Oscillatory (ENO) reconstruction of interface values. Chemical non-equilibrium [

31] is accounted for by solving the conservation equations for the mass fractions of gas species. Dissociating air is modelled with a 5-species gas mixture (including O, N, NO, O

2, and N

2) with chemical reaction rates provided by Park [

20]. The translational and rotational energy of the gas mixture is governed by a single temperature,

; the energy exchange between vibrational and translational modes (

TV) is instead modelled with the classical Landau-Teller non-equilibrium equation, with average relaxation times taken from the Millikan-White [

32], theory modified by Park [

33]. Also, the Park high-temperature limit [

18] is used to prevent the relaxation from becoming faster than the collision time. The viscosity of the single species is evaluated by a fit of collision integrals calculated by Yun and Mason [

34], the thermal conductivity is calculated by means of Eucken’s law, the viscosity and thermal conductivity of the gas mixture are then calculated by using the semi-empirical Wilke formulas. Finally, the diffusion of the multicomponent gas is computed through a sum rule of the binary diffusivity of each couple of species (from the tabulated collision integrals of Yun and Mason [

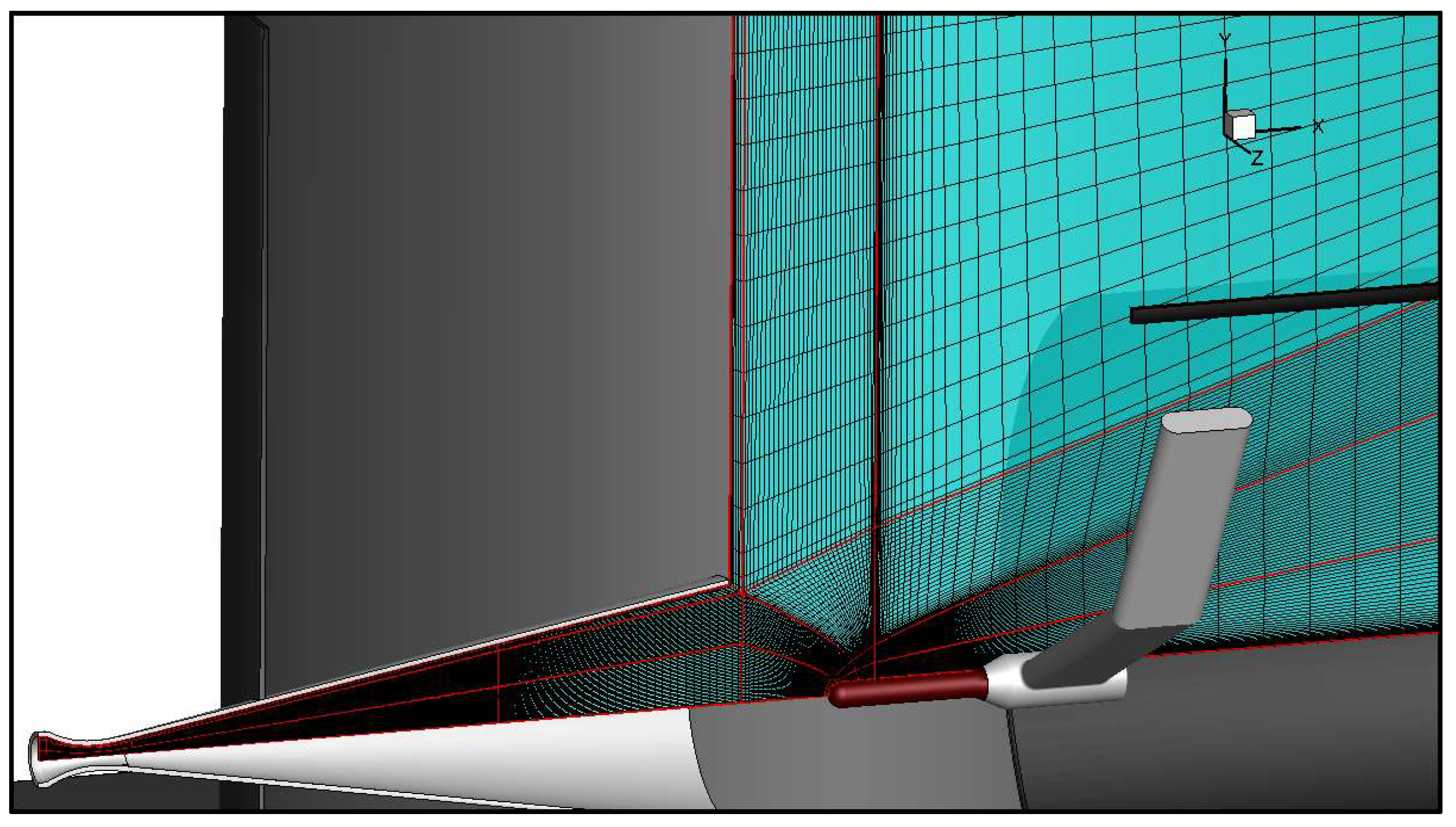

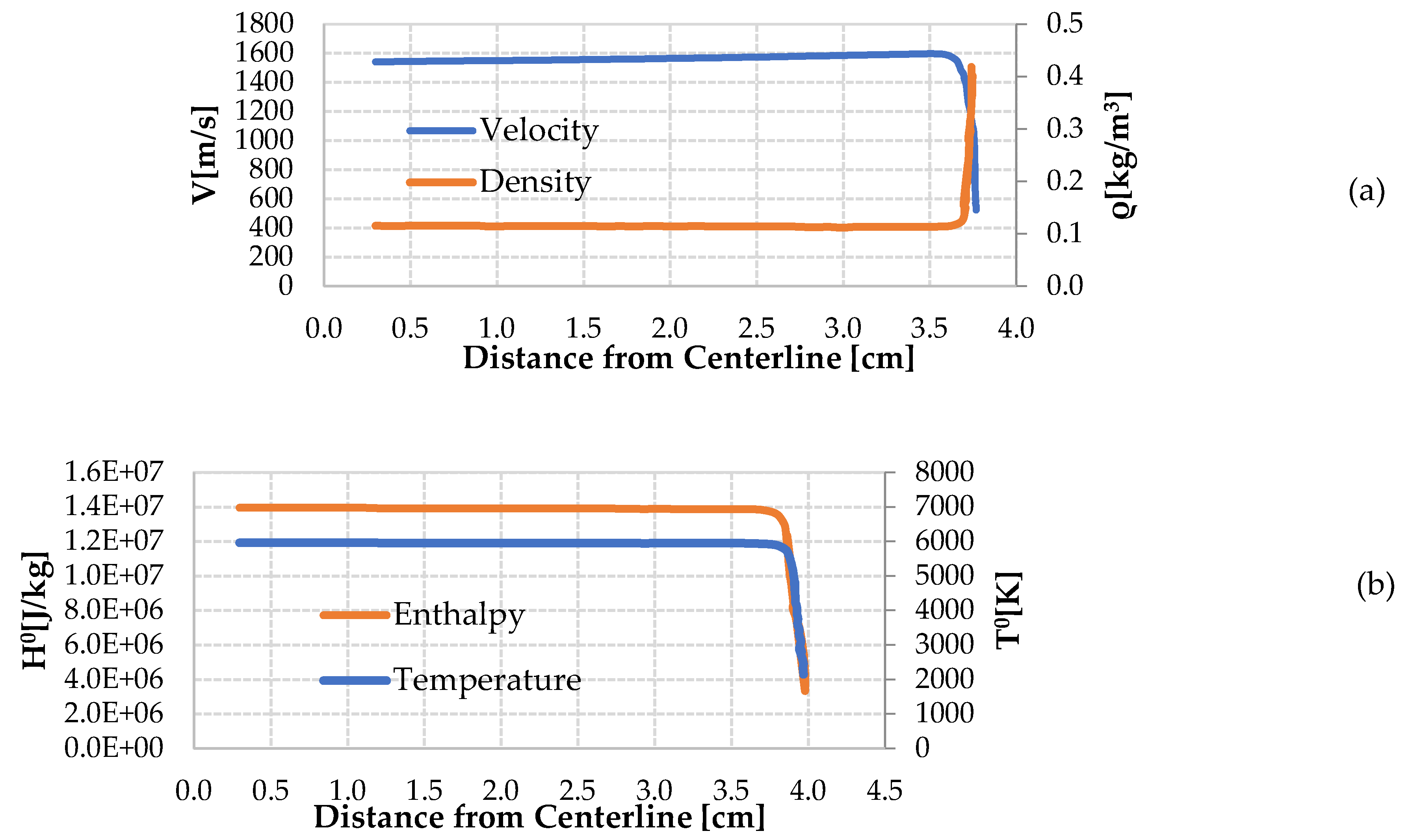

34]). A short description of the Scirocco test rebuilding chain follows. The CFD rebuilding,

Figure 4, of the selected Scirocco tests begins with the numerical evaluation of the reservoir conditions with equilibrium air calculations, imposing the total pressure and enthalpy (

,

) measured for each test: those give the inlet nozzle conditions. Starting from the inlet values as boundary conditions, an axis-symmetrical Navier–Stokes simulation of convergent-divergent nozzle is conducted to obtain the test section. The simulations are iterated by refining the estimation of

and

, until the numerical evaluation of the

and

on the probe matches the experimental measurements. The probe stagnation centerline enthalpy, in turn, coincides with the core enthalpy used for the comparison experimental values. The average enthalpy value is instead obtained by averaging the enthalpy across the nozzle exit section, once the stagnation conditions are matched.

The Scirocco rebuilding simulations have been performed by using the following main physical/numerical models:

2D-axi RANS approach (CIRA NExT solver)

Time marching to steady state solution strategy

2° order Upwind Flux Difference Splitting convective scheme

5-species air in thermal and chemical non-equilibrium as working gas

Fixed temperature (T=370K) nozzle wall boundary condition

Fixed temperature (T=370K) fully catalytic wall boundary condition for the calibration probe.

A 2D-axisymmetric domain including the nozzle, the test chamber and the calibration probe has been modelled and discretized by 34 blocks and about 110.000 cells structured multi-block mesh (on the finer level), as depicted in

Figure 4. The simulations were initially conducted on a coarse grid (approximately 7,000 cells) and a medium grid (around 30,000 cells) to verify grid convergence of the solution, though the results are omitted here for brevity.

Of course, the dependence on flow solution from the grid is not the only source of uncertainty. According to a previous study carried out by Cinquegrana [

25] the choice of a specific transport and chemical-kinetic model is affected by an uncertainty, which can be estimated to be below the 2% on the stagnation heat flux value. However, the level of uncertainty that allows the data to fit a linear curve is 5%. Another source of uncertainty is how the catalytic properties of the calibration probe are modelled, as it depends on the actual surface finish of the calibration probe's material (copper), adding further uncertainties to the simulation. The initial assumption is a fully catalytic response, based on the premise of a mirror-polished probe surface, in this work cases with partial catalytic behavior will also be considered.

At this time, it is worth to point out how the wall heat flux is calculated. Total heat flux is given by three terms, the convective one

after named as ‘roto-translational’, since it is due to the roto-translational temperatures, the vibrational

contribution, the diffusive

contribution, after named as ‘chemical’, and the radiative

contribution as reported in equation 4:

The ‘roto-translational’ wall heat flux contribution is reported in equation 5:

where

is the mixture thermal conductivity. The vibrational contribution to the total wall heat fluxes is valued as reported in equation 6:

where

are the number of chemical species with the vibrational energy mode,

the vibrational conductivity of bi-atomic species,

the vibrational temperature of the i-th vibrational species. Finally, the diffusive, or ‘chemical’ contribution is valued as explained in equation 7:

In NEXT code, it is possible to model partial catalysis of material by means of the recombination probability

, defined as the ratio between the flux of atoms that recombine at surface [

35],

, with the total flux of atoms impinging the surface,

[3636]. It can be shown that the expression for the mass flux of atoms impinging on the surface follows the kinetic theory, and after some elaborations and according to Scott [

37], can be used to derive:

In this case, the involved paths are two independent reactions, and , each with an associated efficiency and .

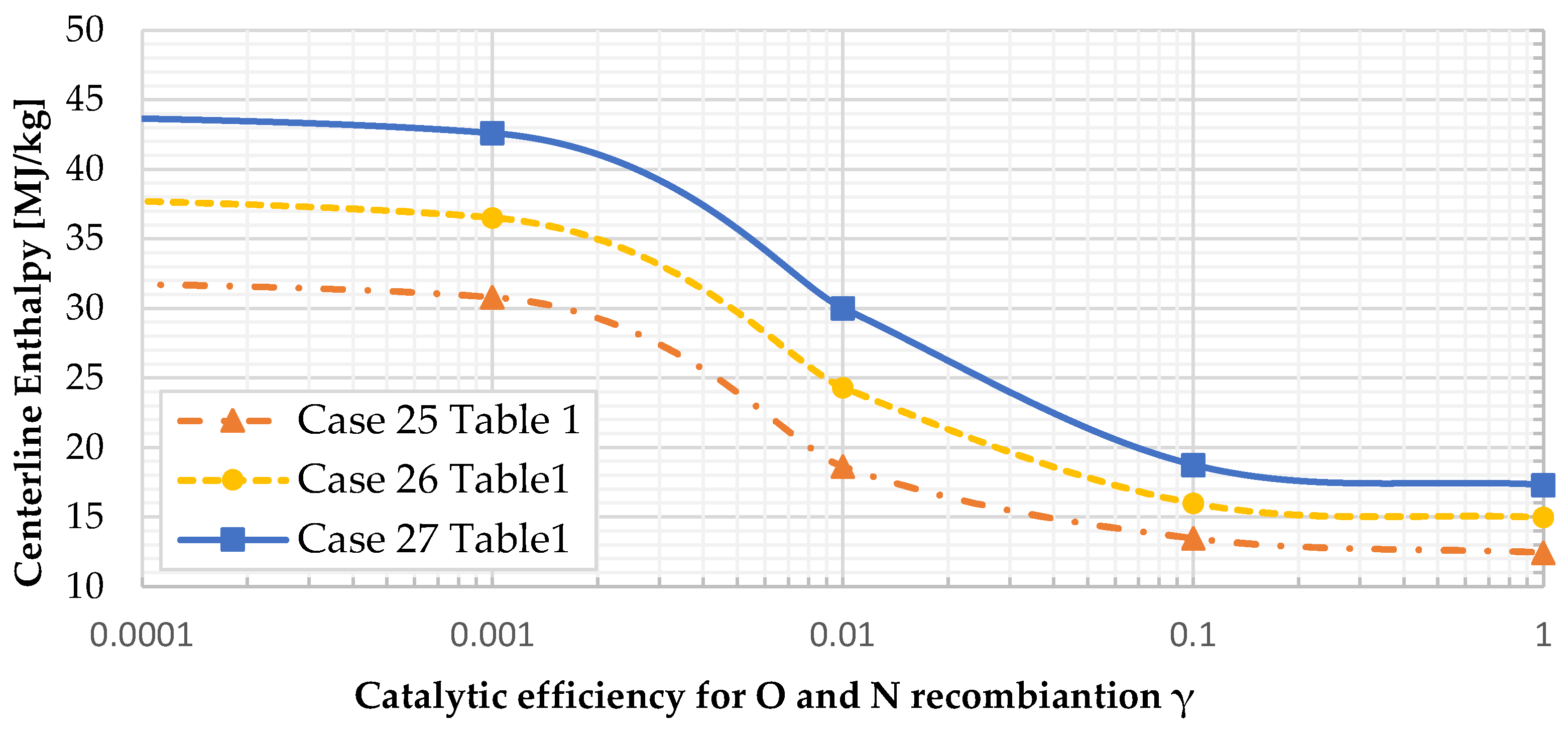

Under the very conservative assumption of a fully catalytic wall, it is possible to achieve the same wall heat flux with a lower total enthalpy. Conversely, if the wall is assumed to be partially catalytic, the match between experimental results and CFD simulations is obtained at higher total enthalpy values. To align the enthalpy values estimated via CFD with those determined through the inverse enthalpy estimation using the heat transfer method, a gamma value of 0.08 was applied. This value falls within the range suggested in the literature for slightly oxidized copper, as discussed in further detail below

5. Results and Discussion

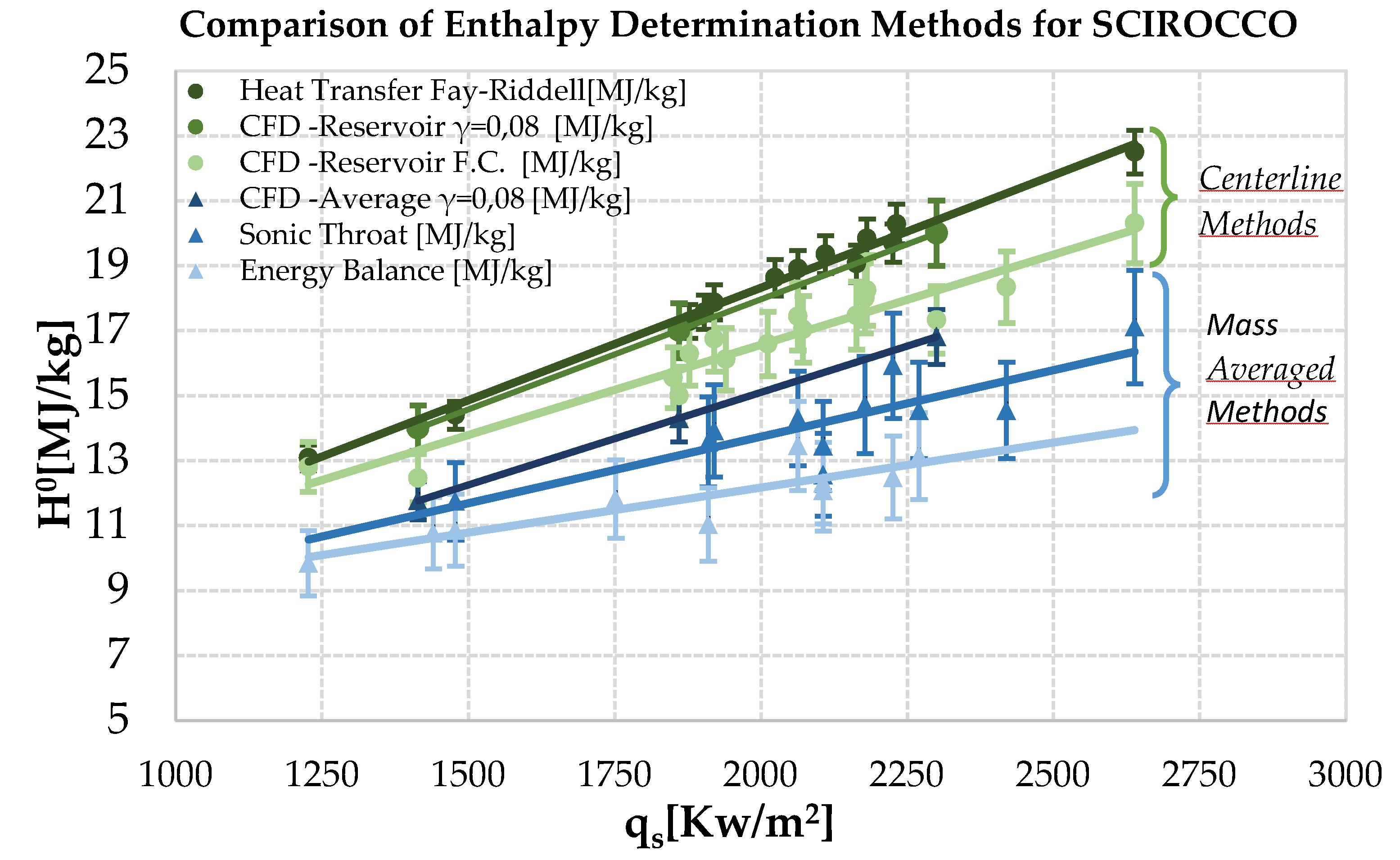

The total enthalpy was determined using several methodologies.

Figure 5 illustrates the results obtained from the experiment and the simulations, providing a comprehensive comparison of the methodologies. The data demonstrate the relationship between

and

, highlighting the linear trends. Error bars represent the uncertainties in the measurements, which were calculated as previously explained. The CFD simulations showed the better agreement with the total enthalpy estimates obtained using the Zoby formula, suggesting that this approach can be considered reliable for the reconstruction of the thermodynamic parameters in the Scirocco PWT, but only by taking into accounts for a more realistic the catalytic effect on the surface, highlighting, the importance of considering the probe oxidation and confirming the literature findings. In the case of complete catalytic activity of the copper surface, the enthalpy is, in fact, underestimated by approximately 10%.

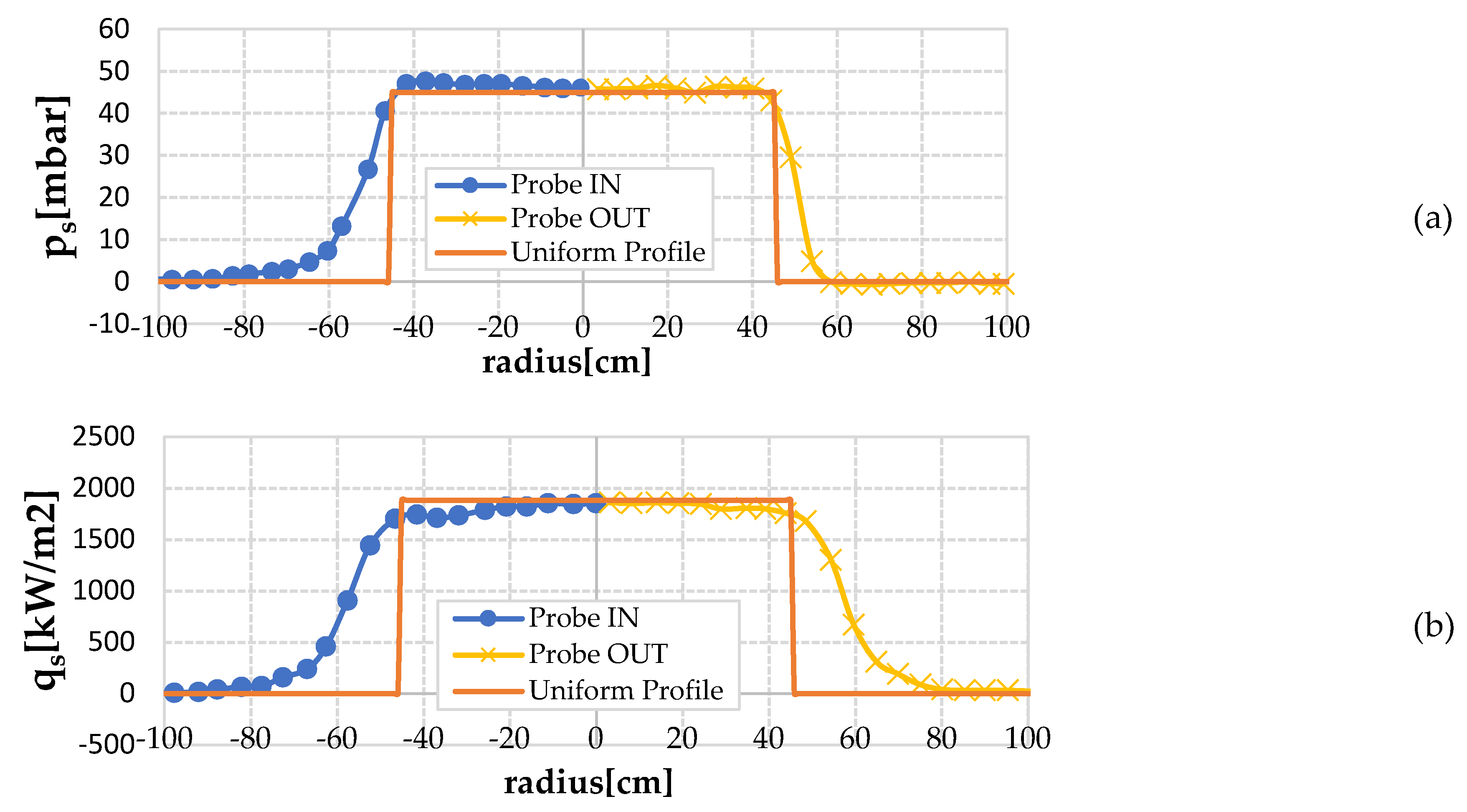

5.1. Mass averaged Enthalpy Measurement, and profile uniformity chacaterization

Regarding mass-averaged enthalpy methods, it was observed that both the Winowich formulas and the energy balance approach, when applied to the Scirocco facility, tend to underestimate the average flow enthalpy compared to values determined by CFD under the hypothesis of finite-rate catalyticity. This discrepancy, may be attributed to simplifying assumptions that fail to fully capture the complexity of the high-enthalpy flow generated, as well as the intrinsic limitations of the formulas themselves. These formulas are based on semiempirical data tailored to the geometry of the NASA-Ames IHF, which features a more radially shaped flow [

15,

16,

17] profile due to a differently shaped nozzle. Consequently, they could not directly be applicable to other similar facilities.

Based on spectroscopically determined centerline enthalpy, Park [

15] defines the ratio of centerline-to-average enthalpies as the centerline enthalpy determined via the spectroscopic method divided by that obtained from the sonic throat method or energy balance method, yielding a ratio of 1.4 to 1.5. Due to the higher non-uniformity in the radial flow profile, based on the plasma core profile reconstruction, the author suggests that it is reasonable for the average enthalpy to be 40% to 50% lower than the centerline value in the IHF facility [

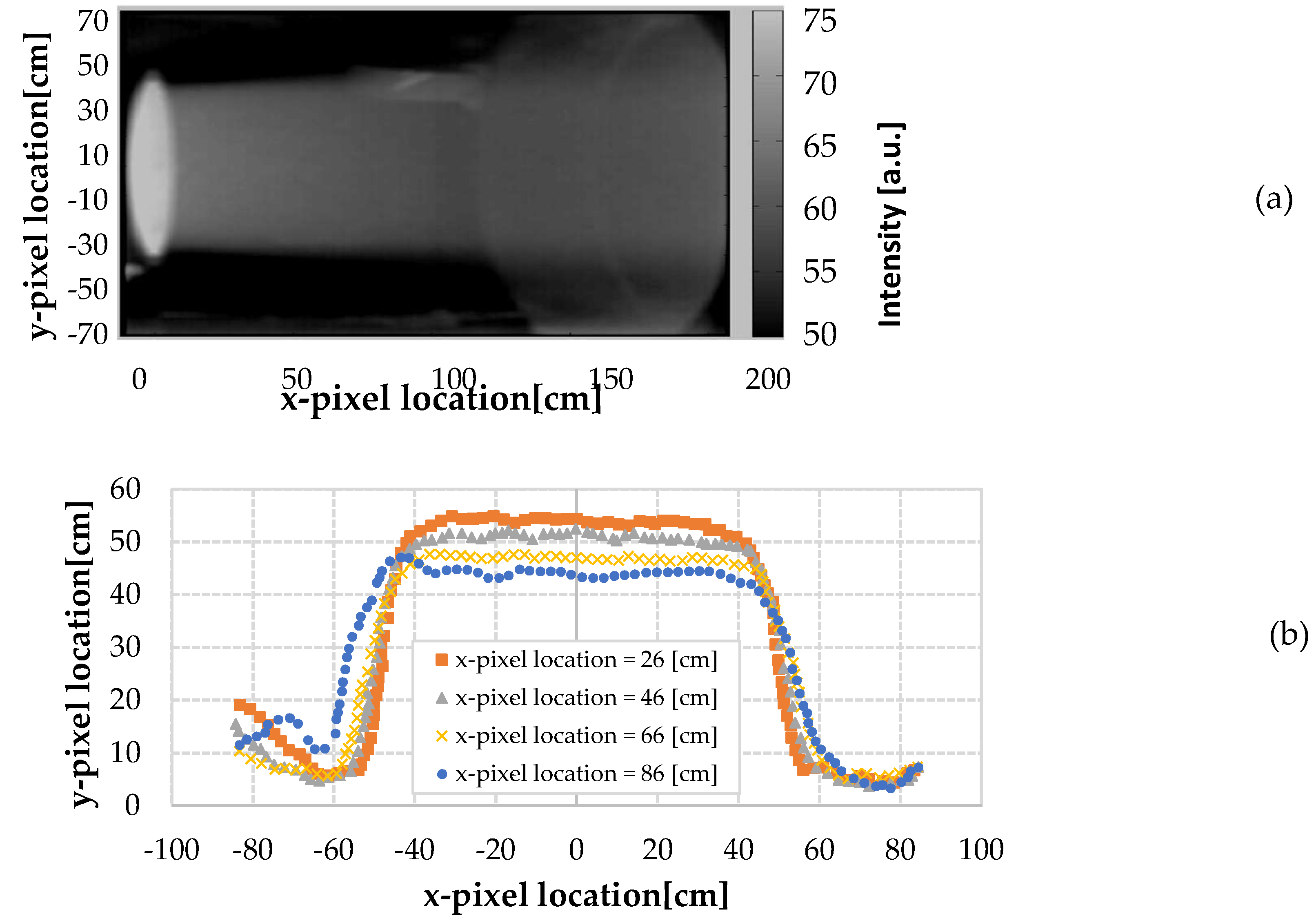

15]. In contrast, the Scirocco facility exhibits a more uniform flow, as confirmed by CFD analysis (

Figure 5), spectroscopic measurements (

Figure 6), and spatially resolved probe measurements (

Figure 7). Based on CFD simulations, the ratio between the centerline enthalpy and the mass-averaged enthalpy along the radial profile of the flow at the nozzle exit section for the SCIROCCO facility was calculated to be 1.2. This implies that average enthalpy is expected to be 20% lower than the centerline, as confirmed by experimental data.

To furtherly confirm jet uniformity, a high-speed CMOS camera (Phantom v4.0, B&W, 8-bit, 512x512 pixels) was employed, capturing 2000 frames at a sampling rate of 1071 Hz with an exposure time of 870μs. The maximum error was ± 5% of the full scale. It collects the radiation in the VIS and near IR spectral range corresponding to the spectral range for which the plasma emission is significant since it is transparent in the infrared spectral range as indicated in [

38]. Notice that the plasma jet presents a diameter of about one meters while the depth of field of the camera corresponds to few centimeters. For this reason, no Abel inversion was needed as reported in [

39,

40]. In

Figure 8, transversal profiles extracted from the mean radiation distribution of the free-stream plasma flow are shown. The excellent uniformity of the flow at the exit section of the nozzle in the Scirocco Wind Tunnel is influenced by several factors, including: the low half-angle and long length of the nozzle, which enable a very gradual expansion; a smooth, well-shaped nozzle throat, with profiles designed to maintain continuity with the linear section up to the second derivative; and a highly uniform and stable exit pressure, achieved through a unique and powerful vacuum system. The correlation between the data suggests that it would be possible to correct the systematic error to use Winovich's formulation in a way that aligns more closely with CFD calculations, even though the CFD results remain within the uncertainty of the formulation. The determination of average enthalpy using the energy balance method presents several limitations, particularly due to its strong dependence on the accuracy of cooling water temperature, as discussed in

Section 4.1.2.

Moreover, the energy balance method presents a significant limitation in the difficulty of achieving thermal steady-state in the facility. Terms associated with electrical power dissipation due to the Joule effect have much faster time constants, akin to the rise time of a first-order system, compared to those related to water cooling. This discrepancy can lead to inaccurate enthalpy estimates and prevent the application of this methodology in short-duration tests, where the thermal steady-state of the entire facility is not achieved.

The energy balance method showed a discrepancy of up to 30% in underestimating the enthalpy value, while the sonic throat method provided a closer estimate to the CFD values, with a difference of 13% in underestimating.

5.2. Centerline Enthalpy Measurement, and surface–catalytic recombination coefficient estimation

In the characterization of arc-jet tunnels, the standard procedure used in Scirocco involves determining the centerline enthalpy using a copper calorimeter, which is recognized for its high catalytic efficiency, as documented in the literature. The local flow enthalpy is calculated through Zoby heat transfer formula given by Park [

15], utilizing the heat transfer rates measured from the calorimeter alongside the assumption of full catalytic efficiency conditions on the wall.

The catalytic phenomena on surfaces significantly affect heat transfer, particularly in the context of total enthalpy determination, as shown in

Figure 9. It was found that the enthalpy exhibits the same trend observed by Park [

15], showing high sensitivity to the chosen γ value within the relevant range

A substantial amount of experimental data has been collected regarding the catalytic effects of oxygen and nitrogen for copper, primarily using arc-jet wind tunnels, along with side-arm reactors [

41], diffusion tubes andarc-jets [

42], and Plasmatron [

43]. This last device enables high chemical purity in plasma flows, providing high valuable data for studying catalytic processes under such conditions. Various studies have measured the catalytic efficiency of copper oxide in different test facilities, as summarized by Chug [

24].

Cheung et al. [

24]summarizes the existing data of catalytic efficiency for copper (Cu) and copper oxide. The copper can be oxidized in two different types of copper oxide: cupric oxide (CuO) and cuprous oxide (Cu₂O). The author reports these values:

ranging from 0.01 to 0.17,

ranging from 0.01 to 0.045 and

ranging from 0.025 to 0.11, for different gas mixture, enthalpy level, wall temperature and facilities. The efficiency of copper oxide has not been measured in a well-defined environment, where flow enthalpy is independently known, the material is unequivocally copper oxide, and the surface is smooth.

Viladegut and Chazot [

43] present an experimental approach to develop a catalytic model for surfaces exposed to high-temperature, low-pressure plasma flow conditions. This technique, known as the Mini-Max method, is applied at the Plasmatron facility at VKI to determine the catalytic recombination coefficient on a copper-based calorimeter. Their findings reveal a notable decrease in the recombination coefficient at elevated pressures, while it remains relatively stable across the range of power levels tested. They indicate a range for γ gamma between 0.088 and 0.026 for a copper probe, with a stagnation pressure range between 15 and 50 mbar, in good agreement with the analyzed cases for Scirocco.

In the case analyzed in this study, matching the CFD estimations with calorimetric measurements led to an estimation of γ = 0.08 for both nitrogen and oxygen recombination, as discussed in

Section 4.2. This value agrees with Pope’s [

44] estimation for copper and nitrogen (N₂) recombination, measured at a cold wall temperature of 350 K in an arc-jet facility.

Conclusions and Future Work

A systematic analysis of methods for determining the flow enthalpy in the Scirocco Plasma Wind Tunnel was conducted. Three experimental approaches—the sonic throat method, the heat balance method, and the heat transfer method—were evaluated across various operating conditions. Significant discrepancies were observed between measured and predicted heat flux values, necessitating a reassessment of both experimental and numerical models. Initial simulations using a Navier-Stokes model with fully catalytic copper walls underestimated the flow enthalpy. As discussed by Nawaz et al. [

45] a fully polished and catalytic surface is nearly impossible, as exposure to atmospheric air quickly forms a thin layer of copper oxide. This discrepancy has been mitigated by introducing partial catalytic behavior at the probe surface.

This adjustment improved alignment between computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and experimental data, providing a more accurate representation of heat flux and flow enthalpy. Further evidence of enthalpy underestimation was provided by spectroscopic measurements, showing that the rotational temperature at the nozzle exit exceeded values derived from CFD-based enthalpy calculations [

39,

40].

The analysis is of course subject to uncertainties related to simplifying assumptions, particularly regarding copper surface oxidation state and surface roughness which further complicate measurements, as rougher surfaces generally exhibit higher effective catalytic efficiency. Prolonged exposure exacerbates these effects, making precise determination of the catalytic efficiency coefficient challenging [

46,

47,

48].

Future studies will focus on exploring correlations between the catalytic efficiency coefficient and stagnation pressure, as observed by A. Viladegut and O. Chazot[

43]. Additionally, further efforts should investigate a broader range of operating conditions of both the Scirocco and GHIBLI facilities to refine experimental and computational methods for high-enthalpy flow predictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. Smoraldi.; Methodology, A. Smoraldi.; Simulations, L. Cutrone; Investigation, A. Smoraldi; Data curation, A. Smoraldi, L. Cutrone.; Writing—original draft preparation, A. Smoraldi.; Writing—review and editing, A. Smoraldi, L. Cutrone. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Purpura, for providing the materials that supported the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guida, D.; Smoraldi, A.; Schettino, A. Design of a High Enthalpy Hypersonic Nozzle for Ghibli Plasma Wind Tunnel. In Proceedings of the ICAS 2024 AIAA, Firenze, Italy, 9–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D.G. Measurement Requirements for Improved Modeling of Arcjet Facility Flows. Paper presented at RTO AVT Course on Measurement Techniques for High Enthalpy and Plasma Flows. Rhode-Saint-Genèse, Belgium, October 1999; Published in RTO EN-8.

- Hightower, T.M.; Balboni, J.A.; Mac Donald, C.L.; Anderson, K.F.; Martinez, E.R. Enthalpy by Energy Balance for Aerodynamic Heating Facility at NASA Ames Research Center Arc Jet Complex. 48th International Instrumentation Symposium, ISA – The Instrumentation, Systems, and Automation Society, San Diego, CA, May 2002.

- Winovich, W. On the Equilibrium Sonic-Flow Method for Evaluating Electric Arc Air-Heater Performances. NASA TN D-2132, March 1964.

- Loehle, S. Comparison of Heat Flux Gages for High Enthalpy Flows - NASA Ames and IRS. In Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Thermophysics Conference, AIAA; 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, D.; Philippidi, D.; Terrazas-Salinas, I. Uncertainty Analysis of Coaxial Thermocouple Calorimeters Used in Arc Jets. NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 94035.

- Standard Test Method for Measuring Heat Transfer Rate Using a Thermal Capacitance (Slug) Calorimeter. ASTM Standard E 457-08; American Society for Testing and Materials, 2008.

- Terrazas-Salinas, I., Carballo, J., Driver, D., & Balboni, J. (2012). Comparison of Heat Transfer Measurement Devices in Arc Jet Flows with Shear. Session: TP/HT-21: Entry, Descent and Landing, Published Online: 13 Nov 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Anderson and R. E. Sheldahl, Experiments with Two Flow-Swallowing Enthalpy Probes in High-Energy Supersonic Streams. AIAA Journal, 17 May 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Baronets, N. G. Bykove, A. N. Gordeev, I. S. Pershin, and M. I. Yakushin, Experimental characterization of induction plasmatron for simulation of entry into Martian atmosphere. in Aerothermodynamics for space vehicles: Proceedings of the 3rd European Symposium on Aerothermodynamics for space vehicles held at ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 24-26 November 1998, R. A. Harris, Ed., ESA SP-426, pp. 421, 1999.

- J. Grey, P. F. Jacobs, and M. P. Sherman, Calorimetric Probe for the Measurement of Extremely High Temperatures. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1962, 33, 738–741. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang, F. Sun, L. Zhu, M. P. Planche, H. Liao, C. Dong, and C. Coddet, Measurement of Specific Enthalpy Under Very Low Pressure Plasma Spray Condition. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2012, 21, 489–495. [CrossRef]

- Fasoulas, S.; Stockle, T.; Auweter-Kurtz, M. Measurement of Specific Enthalpy in Plasma Wind Tunnels Using a Mass Injection Probe. In Proceedings of the 32nd AIAA Thermophysics Conference, AIAA, Atlanta, GA; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Laux, T.; Feigl, M.; Auweter-Kurtz, M.; Stockle, T. Estimation of the Surface Catalycity of PVD Coatings by Simultaneous Heat Flux and LIF Measurements in High Enthalpy Air Flows. In Proceedings of the 34th Thermophysics Conference, AIAA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Raiche, G.A., II; Driver, D.M.; Olejniczak, J.; Terrazas-Salinas, I.; Hightower, T.M.; Saka, T. Comparison of Enthalpy Determination Methods for Arc-Jet Facility. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2006, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, J.H.; Driver, D.M.; Raiche, G.A., II. Radial Profiles of Arc-Jet Flow Properties Measured with Laser-Induced Fluorescence of Atomic Nitrogen. AIAA Paper 2003-0400, January 2003.

- Park, C. Stagnation-Point Radiation for Apollo 4. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2004, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, T.; Stöckle, T.; Fasoulas, S.; Messerschmid, E. Comparison of Numerical Results with Experimental Investigations Obtained by Newly Developed Probes in a Plasma Wind Tunnel. In Aerothermodynamics for Space Vehicles, Harris, R.A., Ed.; ESA Special Publication, Vol. 426, 1999; p. 445.

- Park, C. , Review of Chemical-Kinetic Problems of Future NASA Missions I - Earth Entries. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 1993, 7, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Park, S-H Lee Validation Of Multi-Temperature Nozzle Flow Code NOZNT AIAA-93-2862.

- Goulard, R. On Catalytic Recombination Rates in Hypersonic Stagnation Heat Transfer. Jet Propulsion 1958, 28, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.L.; Sheldahl, R.E. Influence of Calorimeter Surface Treatment on Heat-Transfer Measurements in Arc-Heated Test Streams. AIAA Journal 1966, 4, 715–716. [Google Scholar]

- Viladegut and, O. Chazot, Empirical Modeling of Copper Catalysis for Enthalpy Determination in Plasma Facilities. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 2512–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.M.; Park, G.; Schrijer, F.F.J. Oxygen and Nitrogen Surface Catalytic Recombination on Copper Oxide in Tertiary Gas Mixtures. In Proceedings of the 2015 World Congress on Aeronautics, N/Ao, Bio, Robotics and Energy, Incheon, Korea, 25–28 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- D. Cinquegrana, R. Votta, C. Purpura, and E. Trifoni, Continuum breakdown and surface catalysis effects in NASA arc jet testing at SCIROCCO. Aerospace Science and Technology 2019, 88, 258–272. [CrossRef]

- C. Purpura, F. De Filippis, P. Barrera, and D. D. Mandanici, Experimental characterization of the CIRA plasma wind tunnel SCIROCCO test section. Acta Astronautica 2008, 62, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Medtherm Corp. Coaxial Surface Thermocouple Probe, Bulletin 500; Medtherm Corp., PO Box 412, Huntsville, AL 35804, Ph 256-837-2000.

- Zoby, E.V. Empirical Stagnation-Point Heat-Transfer Relation in Several Gas Mixtures at High Enthalpy Levels. NASA TN D-4799, October 1968.

- Ranuzzi, G.; Cutrone, L. Numerical Simulation of LRE and HRE Reacting Flowfields. In Proceedings of the 67th International Astronautical Congress, 2016; Paper ID: 34544.

- Pandolfi, M. , Borrelli S., An Upwind Formulation for Hypersonic Non-equilibrium Flows, Modern Research Topics in Aerospace Propulsion, Springer-Verlag, 1991.

- Flament, C. Chemical and Vibrational Nonequilibrium Nozzle Flow Calculation by an Implicit Upwind Method. In Proceedings of the 8th GAMM Conference on Numerical Methods in Fluid Mechanics, Delft, 1989.

- Millikan, R.C.; White, D.R. Systematics of Vibrational Relaxation. Journal of Chemical Physics 1963, 39, 3209–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. Two-Temperature Interpretation of Dissociation Rate Data for N2 and O2. In Proceedings of the Aerospace Sciences Meetings, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.; Mason, E. Collision Integrals for the Transport Properties of Dissociating Air at High Temperatures. Physics of Fluids 1962, 5, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrone, L.; Mastellone, A.; Ranuzzi, G.; Schettino, A.; Matrone, A. User Manual of CAST v 2.1; Tech. Rep. CIRA/CAST/DT-86: User’s Manual CAST V.2 - REV.1, CIRA Scpa, March.

- Kang, S.-W.; Jones, W.L.; Dunn, M.G. Theoretical and Measured Electron-Density Distributions at High Altitudes. AIAA Journal 1973, 11, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. D. Scott. Wall boundary equations with slip and catalysis for multicomponent nonequilibrium gas flows. NASA TM X-58111, December 1973.

- L. Savino, A. Martucci, A. Del Vecchio, M. De Cesare, A novel physics methodologybased on Compact Emission Spectroscopy in the VNIR (0.4–0.9 μm) ranges for Plasma shock layer and Material Temperature determinations and study case of surface Emissivity evaluations in the VNIR - LWIR (7–14 μm) ranges during atmospheric re-entry by PWT facility. Infrared Physics & Technology 2020, 108, 103353. [CrossRef]

- Cipullo, L. Savino, E. Marenna, F. De Filippis, Thermodynamic State Investigation of Hypersonic Air plasma Flow Produced by an Arc-Jet Facility. Aerospace Science and Technology 2012, 23, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, L. , Cinquegrana D., French A., De Cesare M., resolved Optical Emission Spectroscopy as accurate physics methodology for plasma freestream temperature characterization. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2022, 291, 108323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. M. Driver e S. Sepka, Side Arm Reactor Study of Copper Catalysis. AIAA 2015-2666, Plasma and Arc Jet Testing, Diagnostics and Computational Methods, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Vasil’evskii, A. N. Gordeev, A. F. Kolesnikov, e A. V. Chaplygin, Thermal Effect of Surface Catalysis in Subsonic Dissociated-Air Jets. Experiment on a High-Frequency Plasmatron and Numerical Modeling. Fluid Dynamics 2020, 55, 708–720. [CrossRef]

- Viladegut e, O. Chazot, Empirical Modeling of Copper Catalysis for Enthalpy Determination in Plasma Facilities. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, pubblicato online il 24 giugno 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Pope, Stagnation-Point Convective Heat Transfer in Frozen Boundary Layers. AIAA Paper No. 68-15, 1968.

- Nawaz, A.; Driver, D.; Terrazas-Salinas, I.; Sepka, S. Surface Catalysis and Oxidation on Stagnation Point Heat Flux Measurements in High Enthalpy Arc Jets. In Proceedings of the 44th AIAA Thermophysics Conference, AIAA, 2013.

- Kidd, C.T. High Heat-Flux Measurements and Experimental Calibrations/Characterizations. In NASA CP 3061, NASA Langley Measurement Technology Conference; pp. 317–335, 1993.

- Kidd, C.T.; Nelson, C.G.; Scott, W.T. Extraneous Thermoelectric EMF Effects Resulting from the Press-Fit Installation of Coaxial Surface Thermocouples in Metal Models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Instrumentation Symposium, Instrument Society of America, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA; 1994; pp. 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Brune, J.A. Uncertainty Analysis of Slug Calorimeters in the NASA Hy-METS Arc-Jet Facility; Morrow, C.C. Published Online: 23 February 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).