Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PROSTATE tissues

2.2. Transcriptomic Characterization of Individual Genes (Appendix A)

2.3. Transcriptomic Characterization of Functional Pathways and Their Interplay

2.4. Quantification of Transcriptomic Regulation (Appendix A)

3. Results

3.1. The three CHS and TLR genes with the highest expression level (largest AVE)

3.2. The Three Most Controlled CHS and TLR Genes in Each Profiled Region

3.3. The Three Least Controlled CHS and TLR Genes in Each Profiled Region

3.4. Regulation of the TLR-Signaling Pathway In The Cancer Nodules Compared To The Surrounding Normal Tissue

3.5. Regulation of the Chemokine Signaling (CHS) Pathway

3.6. Remodeling of the TLR-CHS Interplay

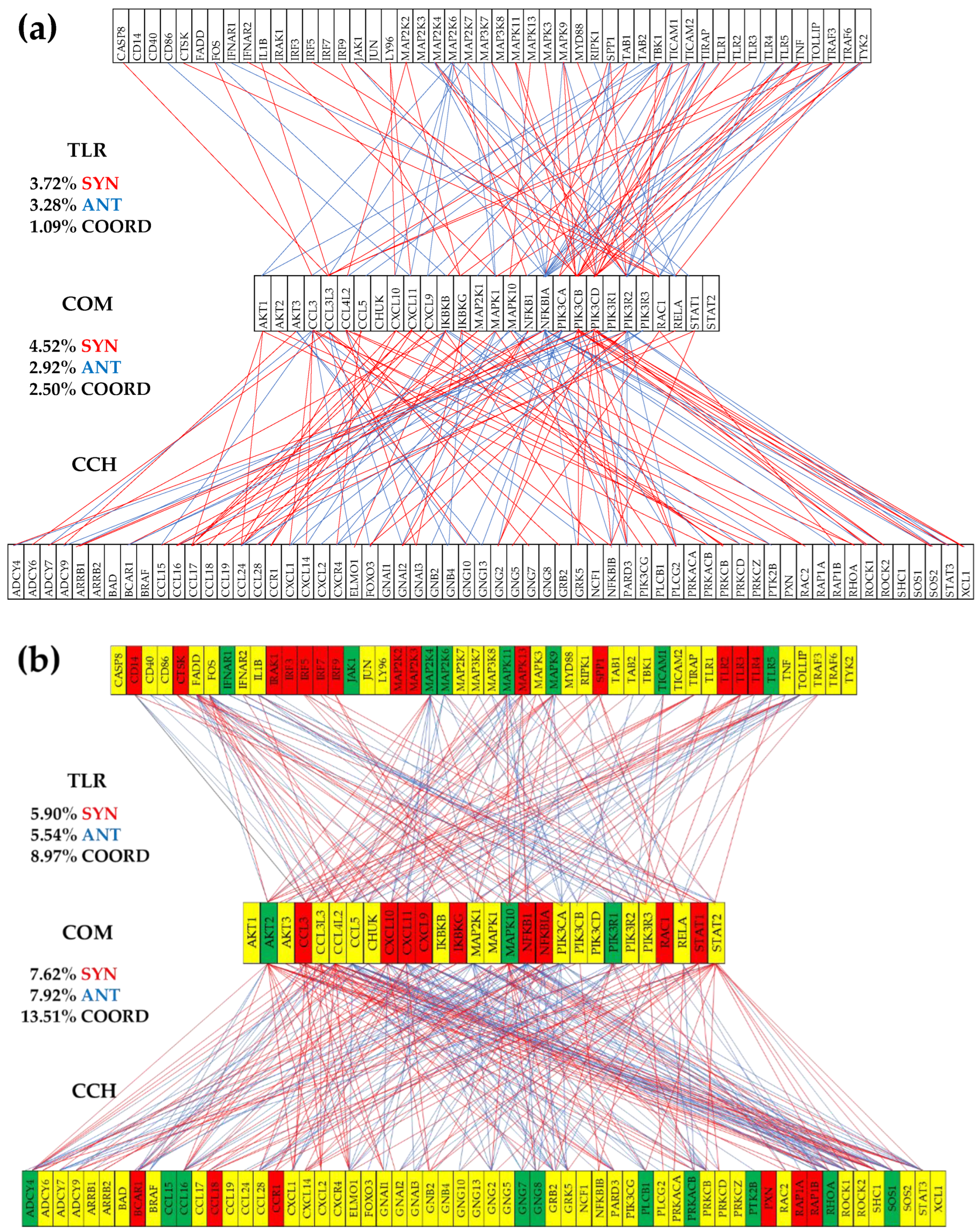

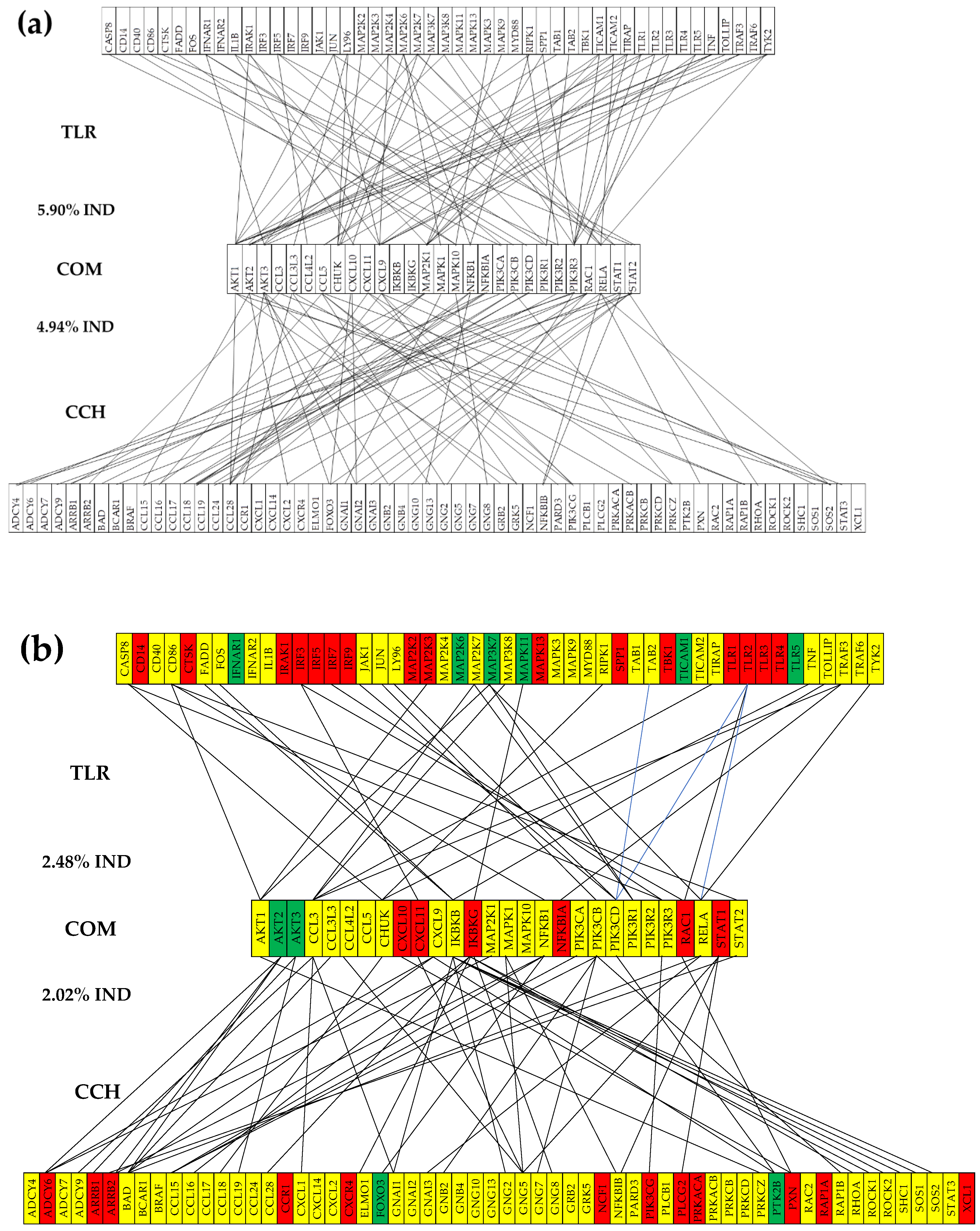

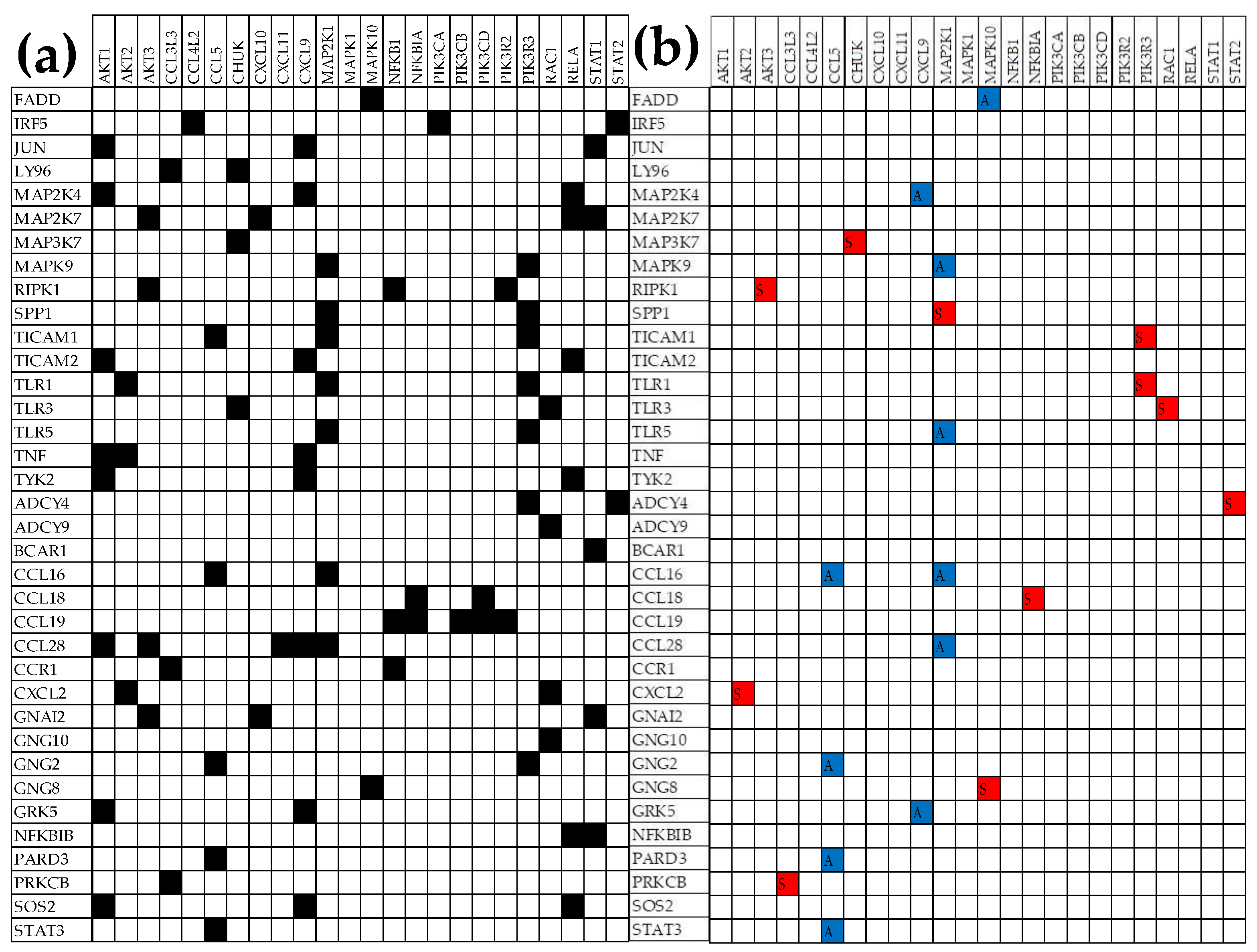

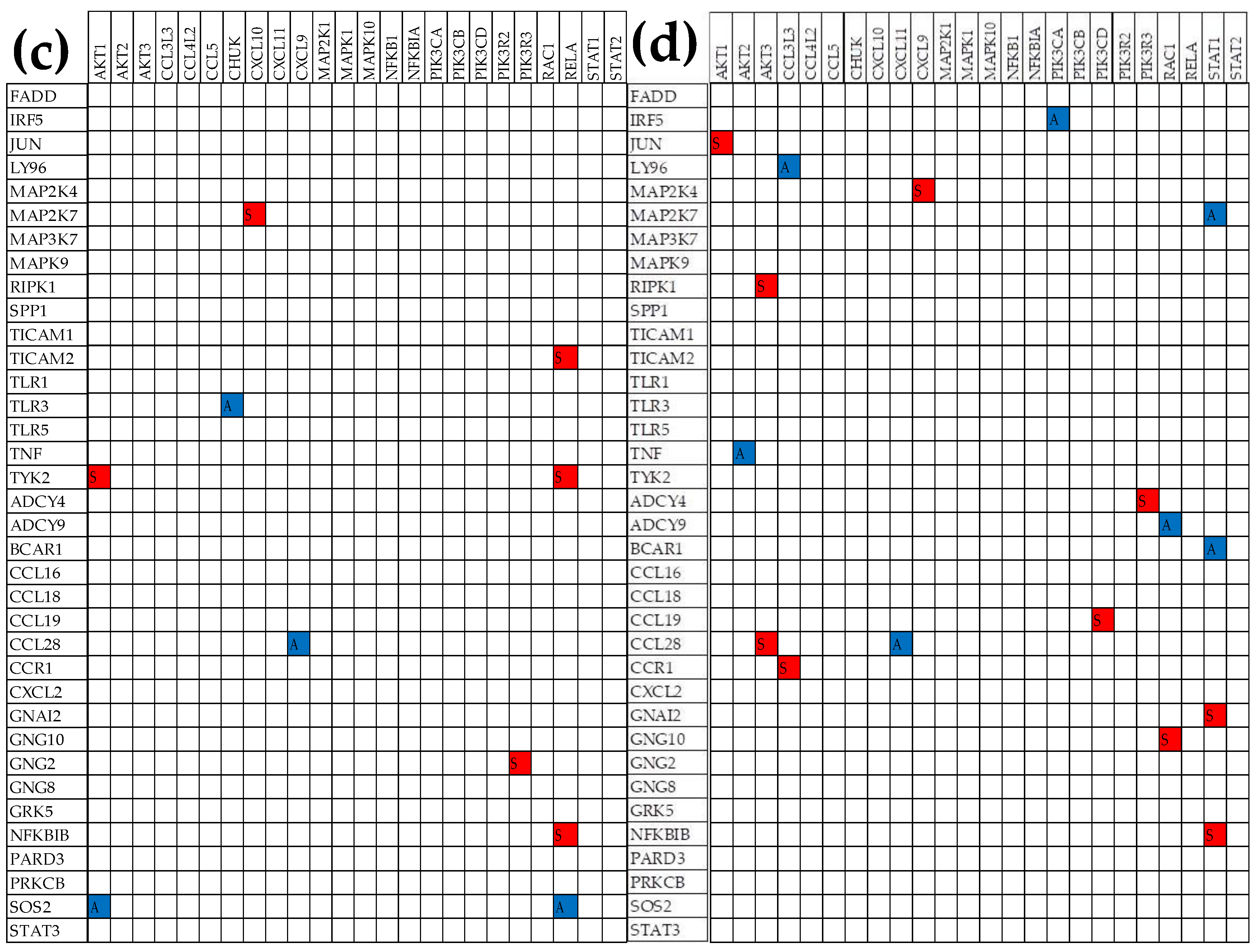

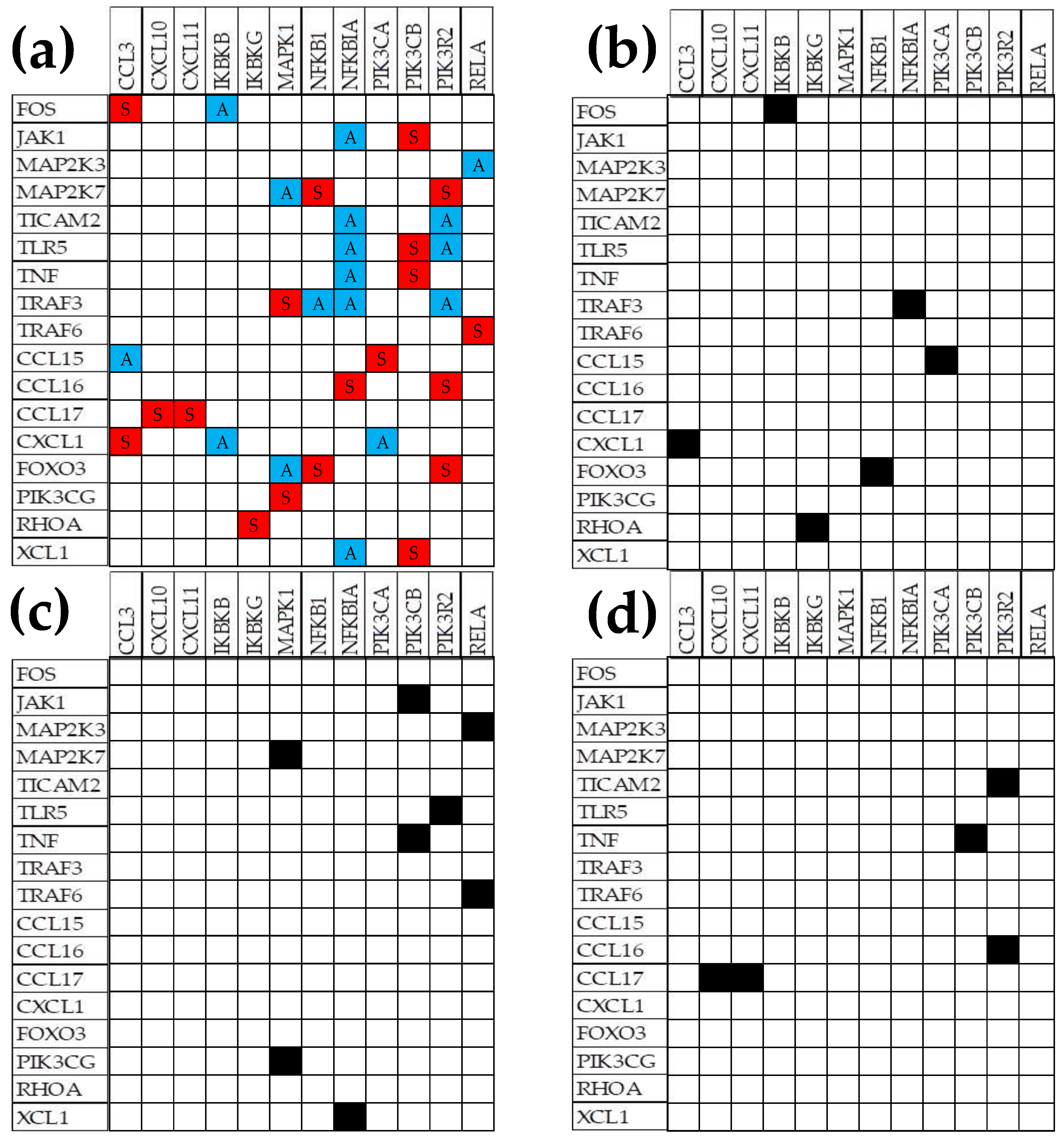

3.6.1. Significant Expression Coordination

3.6.2. Significant Expression Independence

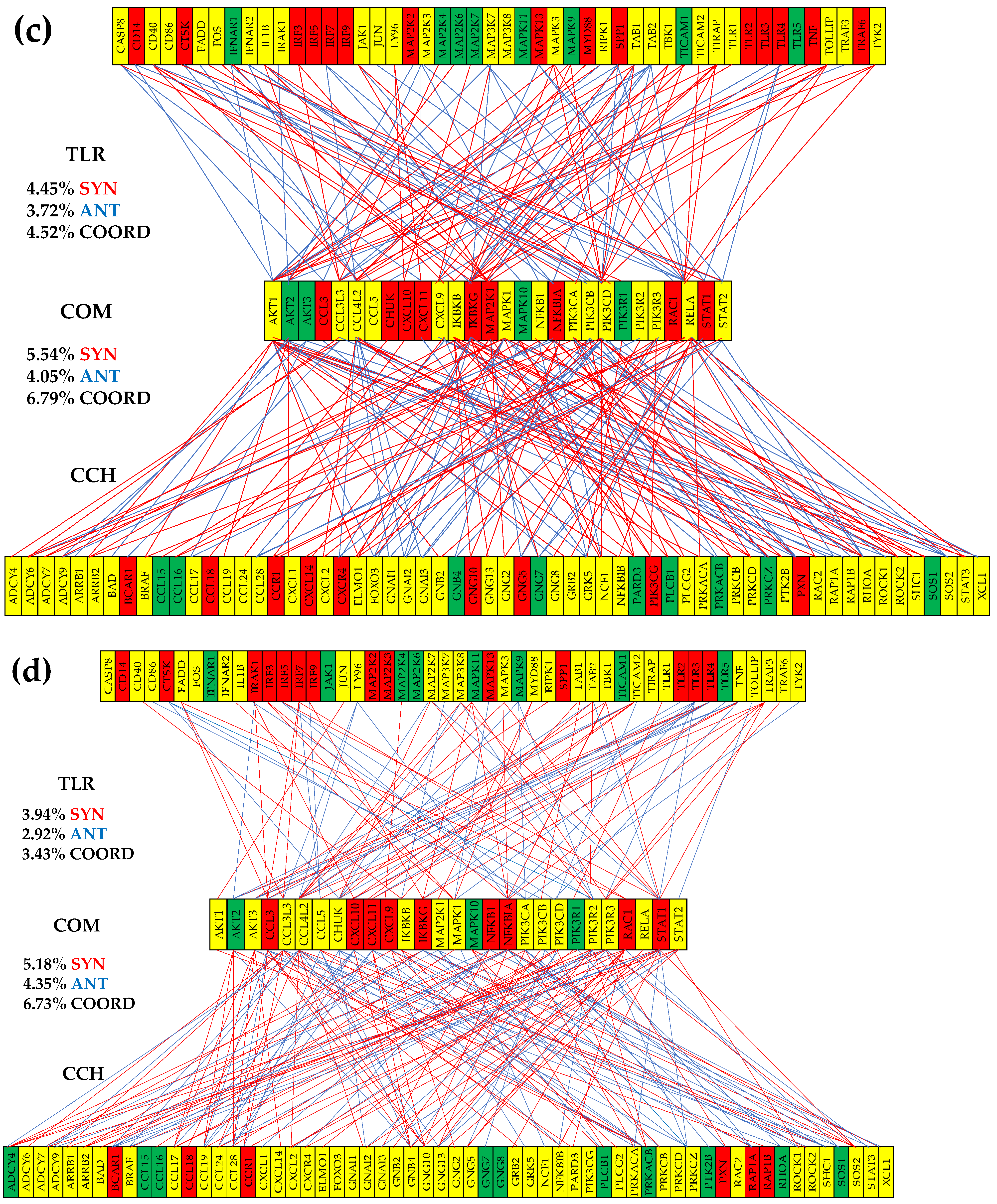

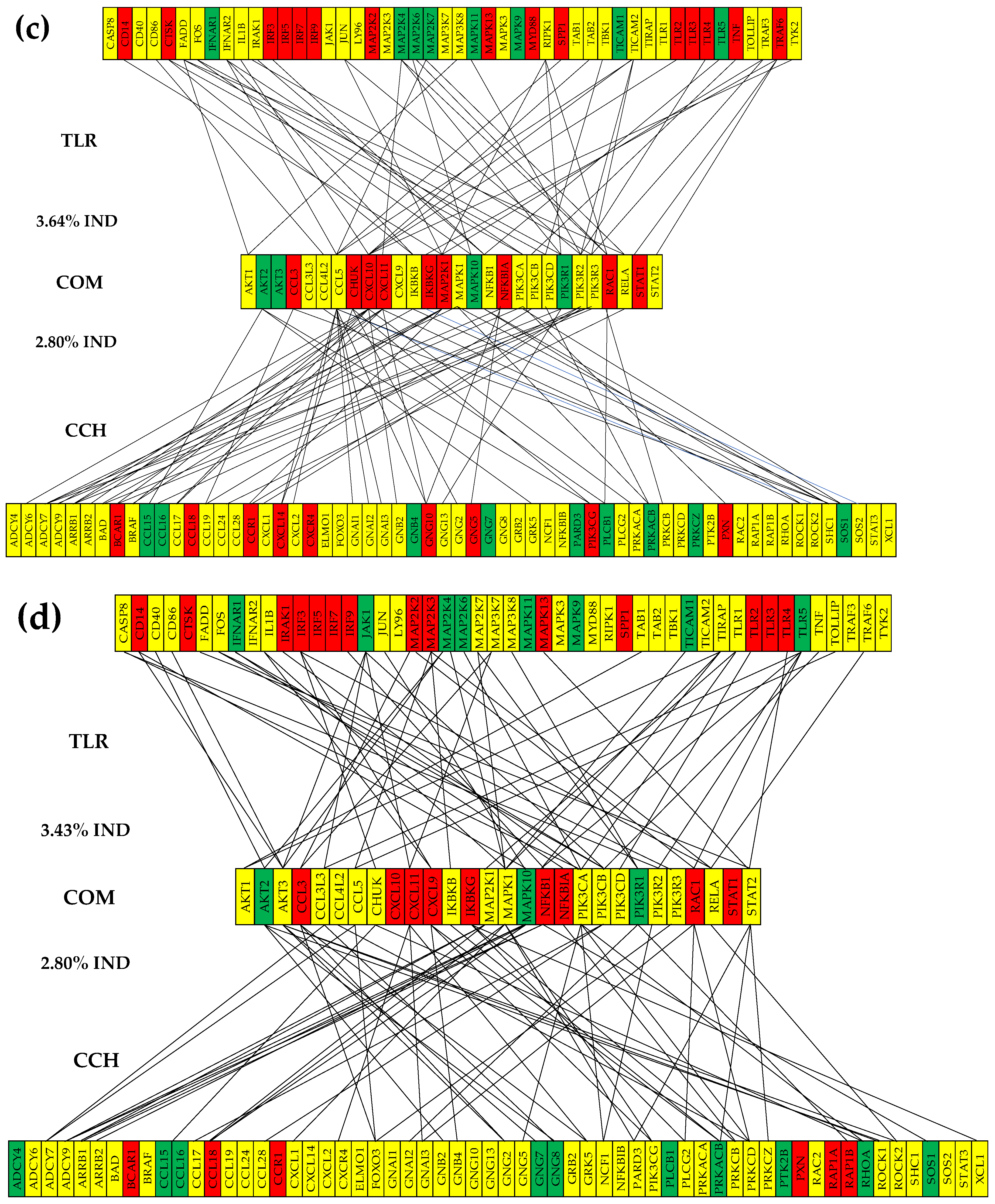

3.6.3. Prostate Cancer Couples Several Normally Independently Expressed TLR and CHS genes

3.6.4. Prostate Cancer Decouples Several Coordinately Expressed TLR and CHS Gene-Pairs in the Normal Tissue

3.6.5. Prostate Cancer Switches to the Opposite the Normal Coupling of Several Gene Pairs

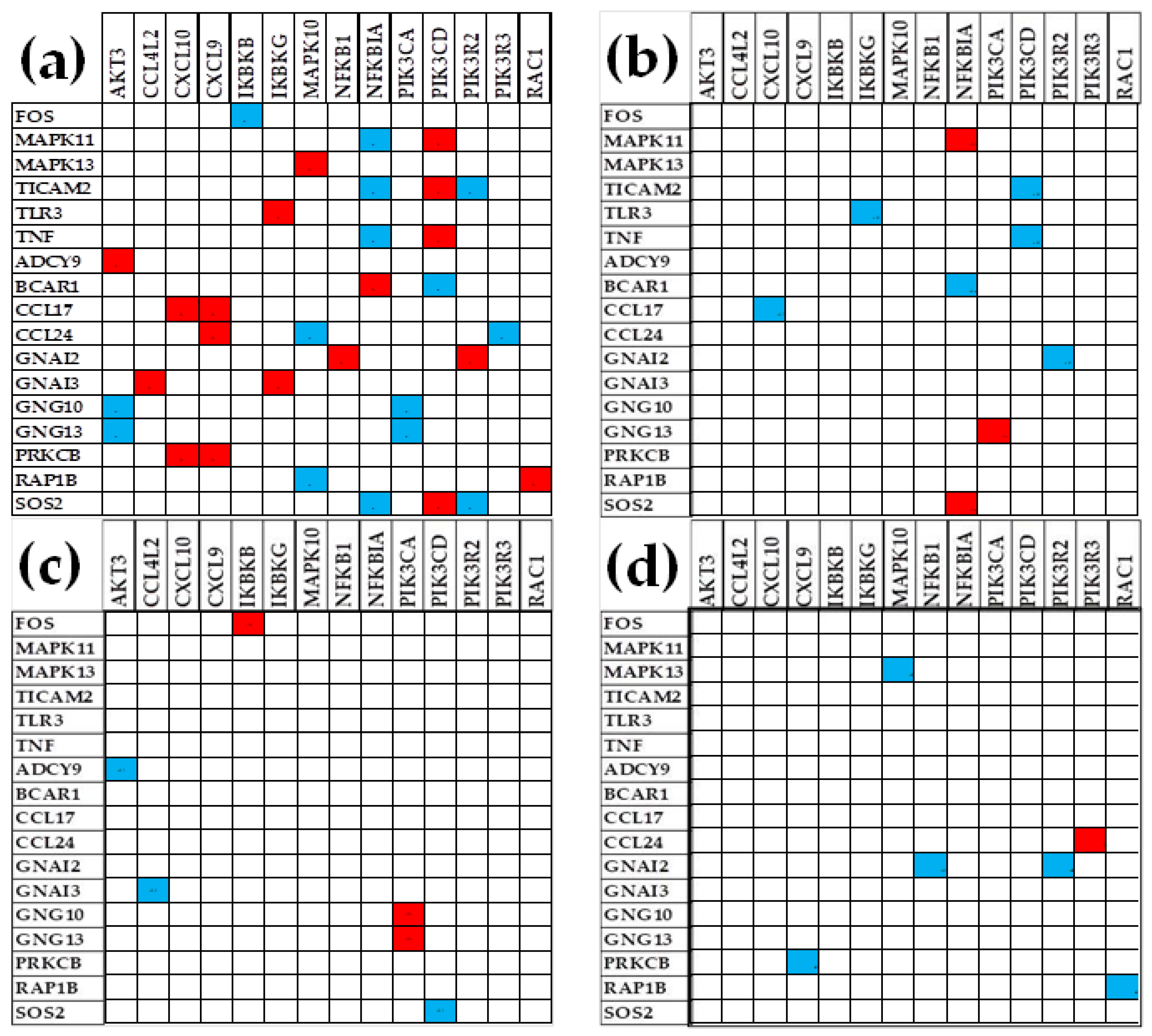

3.7. Key Influential Genes in the CHS and TLR Signaling Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A (software details in [71])

- 1.

- Normalized Average expression level (AVE)

- 2.

- Relative Expression Variation (REV)

- 3.

- Correlation (COR) of expression levels of two genes

- 4.

- Relative Control Strength (RCS)

- 5.

- Relative Expression Control (REC)

- 6.

- Gene Commanding Height (GCH)

- 7.

- Significant regulation of the individual genes’ expression levels

- 8.

- Fold-change (FC) of the Relative Control Strength:

References

- Carpenter, S.; O'Neill, LAJ. From periphery to center stage: 50 years of advancements in innate immunity. Cell.; 187(9):2030-2051. [CrossRef]

- Janeway, C.A. Jr. Pillars article: approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold spring harb symp quant biol. 1989. 54: 1-13. J Immunol. 2013; 191(9):4475-87. PMID: 24141854.

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994; 12:991-1045. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R.; Iwasaki, A. Exploring new perspectives in immunology. Cell. 2024; 187(9):2079-2094. [CrossRef]

- De Nunzio, C.; Lombardo, R. Best of 2022 in prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023; 26(1):5-7. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Hoden, B.; DeRubeis, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Upregulation of TLR5 indicates a favorable prognosis in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2023; 83(11):1035-1045. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. A Personalized Genomics Approach of the Prostate Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1644. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Iacobas, D.A. Personalized 3-Gene Panel for Prostate Cancer Target Therapy. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 360-382. [CrossRef]

- Gambara, G.; De Cesaris, P.; De Nunzio, C.; Ziparo, E.; Tubaro, A.; Filippini, A.; Riccioli, A. Toll-like receptors in prostate infection and cancer between bench and bedside. J Cell Mol Med. 2013; 17(6):713-22. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, G.; Choi, A.; Kim, S.; Yum, J.S.; Chun, E.; Shin, H. Comparative network-based analysis of toll-like receptor agonist, L-pampo signaling pathways in immune and cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2024; 14(1):17173. [CrossRef]

- Gene Commanding Height (GCH) Hierarchy in the Cancer Nucleus and Cancer-Free Resection Margins from a Surgically Removed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma of a 65y Old Black Man. [(accessed on 1 May, 2024)]; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?&acc=GSE133906.

- Genomic Fabric Remodeling in Prostate Cancer. [(accessed on 1 May, 2024)]; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE168718.

- Transcriptomic Heterogeneity of the Prostate Cancer. [(accessed on 1 May, 2024)]; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE183889.

- Agilent-026652 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4x44K v2. (accessed on 1 May, 2024). Available on line at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL10332.

- Iacobas, D.A.; Obiomon, E.A.; Iacobas, S. Genomic Fabrics of the Excretory System’s Functional Pathways Remodeled in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 9471-9499. [CrossRef]

- KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Available online at: www.kegg.jp. Accessed 05/22/2024.

- Toll-like receptor pathway [(accessed on 1 May, 2024)]; Available online at: https://www.genome.jp/pathway/hsa04620. (Accessed on July 21, 2024).

- Chemokine signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human). Available online at: https://www.genome.jp/pathway/hsa04062. (Accessed on July 21, 2024).

- Cheng, C.; Song, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, B. RAC3 Promotes Proliferation, Migration and Invasion via PYCR1/JAK/STAT Signaling in Bladder Cancer. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 218. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas DA. Powerful Quantifiers for Cancer Transcriptomics. World J Clinical Oncology 2020, 11(9):679-704. https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i9/679.htm.

- Prostate cancer. Available on line at: https://www.genome.jp/pathway/hsa05215. Accessed on: 11/02/2024.

- Horoszewicz, J.S.; Leong, S.S.; Kawinski, E.; Karr, J.P.; Rosenthal, H.; Chu, T.M.; Mirand, E.A.; Murphy, G.P. LNCaP model of human prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 1809–1818.

- Remodeling of DNA Transcription Genomic Fabric in Capridine-Treated LNCaP Human Prostate Cancer Cell Line. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE72414 (accessed on 11/01/2024.

- Alimirah, F.; Chen, J.; Basrawala, Z.; Xin, H.; Choubey, D. DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cell lines express androgen receptor: Implications for the androgen receptor functions and regulation. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2294–2300.

- Remodeling of Major Genomic Fabrics and Their Interplay in Capridine-Treated DU145 Classic Human Prostate Cancer. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE72333 (accessed on 1/01/2024).

- Iacobas, D.A.; Mgbemena, V.; Iacobas, S.; Menezes, K.M.; Wang, H.; Saganti, P.B. Genomic fabric remodeling in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): A new paradigm and proposal for a personalized gene therapy approach. Cancers 2020, 12, 3678. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Clarke, S.; Vo, B.T.; Khan, S.A. The essential role of Giα2 in prostate cancer cell migration. Mol Cancer Res. 2012; 10(10):1380-8. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.R. Jr.; Appleton, K.M.; Pierce, J.Y.; Peterson, Y.K. Suppression of GNAI2 message in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2014; 7:6. [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.A.; Salles, D.C.; Engle, E.L.; Zhu, Q.; Tukachinsky, H.; Lotan, T.L, Antonarakis ES. Mismatch repair-deficient prostate cancer with parenchymal brain metastases treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2021; 7(4):a006094. [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, S.R.; Luo, J.; Isaacs, W.B.; Jarrard, D.F. Modulation of CXCL14 (BRAK) expression in prostate cancer. Prostate 2005, 64, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, W.; Meng, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Overexpression of Interferon Regulatory Factor 7 (IRF7) Reduces Bone Metastasis of Prostate Cancer Cells in Mice. Oncol Res. 2017; 25(4):511-522. [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Gao, N.; Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, B.; Guo, L.; Feng, X.; Ji, J.; Cai, Q. et al. A multidimensional recommendation framework for identifying biological targets to aid the diagnosis and treatment of liver metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024; 23(1):239. [CrossRef]

- Mohite, P.; Lokwani, D.K.; Sakle, N.S. Exploring the therapeutic potential of SGLT2 inhibitors in cancer treatment: integrating in silico and in vitro investigations. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2024; 397(8):6107-6119. [CrossRef]

- Mauri, G.; Chiodoni, C.; Parenza, M.; Arioli, I.; Tripodo, C.; Colombo, M.P. Ultrasound-guided intra-tumor injection of combined immunotherapy cures mice from orthotopic prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013; 62(12):1811-9. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.K.; Zhang, Y.; Coomes, A.S.; Kim, W.J.; Stupay, R.; Lynch, L.D.; Atkinson, T.; Kim, J.I.; Nie, Z.; Daaka, Y. G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK5 phosphorylates moesin and regulates metastasis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 3489-3500. [CrossRef]

- Hongo, H.; Kosaka, T.; Takayama, K.I.; Baba, Y.; Yasumizu, Y.; Ueda, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Inoue, S.; Beltran, H.; Oya, M. G-protein signaling of oxytocin receptor as a potential target for cabazitaxel-resistant prostate cancer. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae002. [CrossRef]

- Nickols, N.G.; Nazarian, R.; Zhao, S.G.; Tan, V.; Uzunangelov, V.; Xia, Z.; Baertsch, R.; Neeman, E.; Gao, A.C.; Thomas, G.V.; et al. MEK-ERK signaling is a therapeutic target in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2019, 22, 531-538. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yin, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, G.; Deng, M.; Zhang, G.; Bu, X.; Cai, S.; Du, J.; He, Z. FOXO3a modulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling and suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer cells. Cell Signal 2015, 27, 510-518. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Guo, L.; Gao, M.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. Research Trends and Regulation of CCL5 in Prostate Cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2021, 14, 1417-1427. [CrossRef]

- Aldinucci, D.; Borghese, C.; Casagrande, N. The CCL5/CCR5 Axis in Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vindrieux, D.; Escobar, P.; Lazennec, G. Emerging roles of chemokines in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009, 16, 663-673. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Motegi, T.; Iio, A.; Kaji, K.; Goto-Koshino, Y.; Eto, S.; Ikeda, N.; Nakagawa, T.; Nishimura, R.; Yonezawa, T.; et al. Anti-CCR4 treatment depletes regulatory T cells and leads to clinical activity in a canine model of advanced prostate cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.N.; Jones, D.Z.; Kidd, N.C.; Yeyeodu, S.; Brock, G.; Ragin, C.; Jackson, M.; McFarlane-Anderson, N.; Tulloch-Reid, M.; Sean Kimbro, K.; et al. Toll-like receptor-associated sequence variants and prostate cancer risk among men of African descent. Genes Immun 2013, 14, 347-355. [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, D.J.; Kobayashi, N.; Ruscetti, M.; Zhi, A.; Tran, L.M.; Huang, J.; Gleave, M.; Wu, H. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 1878-1889. [CrossRef]

- Ide, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Terado, Y.; Kamiyama, Y.; Muto, S.; Horie, S. Tyk2 expression and its signaling enhances the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 369, 292-296. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhu, M.; Song, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Ophiopogonin D' induces RIPK1-dependent necroptosis in androgen-dependent LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2020, 56, 439-447. [CrossRef]

- Vuk-Pavlovic, S.; Bulur, P.A.; Lin, Y.; Qin, R.; Szumlanski, C.L.; Zhao, X.; Dietz, A.B. Immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DRlow/- monocytes in prostate cancer. Prostate 2010, 70, 443-455. [CrossRef]

- Deveci Ozkan, A.; Kaleli, S.; Onen, H.I.; Sarihan, M.; Guney Eskiler, G.; Kalayci Yigin, A.; Akdogan, M. Anti-inflammatory effects of nobiletin on TLR4/TRIF/IRF3 and TLR9/IRF7 signaling pathways in prostate cancer cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2020; 42(2):93-100. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, I.; Takagi, K.; Yamaguchi-Tanaka, M.; Sato, A.; Sato, M.; Miki, Y.; Ito, A.; Suzuki, T. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 is a potent prognostic factor in prostate cancer associated with proliferation and invasion. Pathol Res Pract. 2024; 260:155379. [CrossRef]

- Tolkach, Y.; Kristiansen, G. The Heterogeneity of Prostate Cancer: A Practical Approach. Pathobiology 2018, 85, 108–116. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, E.; Maaskola, J.; Schultz, N.; Friedrich, S.; Marklund, M.; Bergenstråhle, J.; Tarish, F.; Tanoglidi, A.; Vickovic, S.; Larsson, L.; et al. Spatial maps of prostate cancer transcriptomes reveal an unexplored landscape of heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2419. [CrossRef]

- Brady, L.; Kriner, M.; Coleman, I.; Morrissey, C.; Roudier, M.; True, L.D.; Gulati, R.; Plymate, S.R.; Zhou, Z.; Birditt, B.; et al. Inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity of metastatic prostate cancer determined by digital spatial gene expression profiling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1426. [CrossRef]

- Kulac, I.; Roudier, M.P.; Haffner, M.C. Molecular Pathology of Prostate Cancer. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2021, 14, 387–401.

- Tu, S.-M.; Zhang, M.; Wood, C.G.; Pisters, L.L. Stem Cell Theory of Cancer: Origin of Tumor Heterogeneity and Plasticity. Cancers 2021, 13, 4006. [CrossRef]

- MAPK signaling pathway. Available online at: https://www.genome.jp/pathway/hsa04010. Accessed on 11/12/2024.

- Huang, R.H.; Zeng, Q.M.; Jiang, B.; Xu, G.; Xiao, G.C.; Xia, W.; Liao, Y.F.; Wu, Y.T.; Zou, J.R.; Qian, B. et al. Overexpression of DUSP26 gene suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion of human prostate cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2024; 442(2):114231. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Lee, P.R.; Cohen, J.E.; Fields, R.D. Coordinated Activity of Transcriptional Networks Responding to the Pattern of Action Potential Firing in Neurons. Genes 2019, 10, 754. [CrossRef]

- Basic Laws of Chemistry–Theories–Principles. Available online: https://azchemistry.com/basic-laws-of-chemistry. Accessed on 10/11/2024.

- Wang, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zhu, W.; Yi, Q.; Zhong, J. The Role of CXCL11 and its Receptors in Cancer: Prospective but Challenging Clinical Targets. Cancer Control 2024, 10732748241241162. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Jiao, W.; Shen, B. The role of proinflammatory cytokines and CXC chemokines (CXCL1-CXCL16) in the progression of prostate cancer: insights on their therapeutic management. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2024, 29, 73. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Toll-like receptors and prostate cancer. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 352. [CrossRef]

- Michalaki, V.; Syrigos, K.; Charles, P.; Waxman, J. Serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha correlate with clinicopathological features and patient survival in patients with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2004, 90, 2312-2316. [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.P.; Barnkob, M.S.; Bai, A.; Higham, E.M.; Wittrup, K.D.; Chen, J. Differential requirement for CD70 and CD80/CD86 in dendritic cell-mediated activation of tumor-tolerized CD8 T cells. J Immunol 2012, 189, 1708-1716. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Deng, B.; Zhao, F.; You, H.; Liu, Y.; Xie, L.; Song, G.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, G.; Shen, W. Silencing SPP1 in M2 macrophages inhibits the progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer via the MMP9/TGFbeta1 axis. Transl Androl Urol 2024, 13, 1239-1255. [CrossRef]

- Messex, J.K.; Byrd, C.J.; Thomas, M.U.; Liou, G.Y. Macrophages Cytokine Spp1 Increases Growth of Prostate Intraepithelial Neoplasia to Promote Prostate Tumor Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J, Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014; 30(4):523-30. [CrossRef]

- KEGG-designed functional pathways of the excretory system. Available online at: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/hsa04960 / 04961 / 04962 / 04964 / 04964 / 04966. Accessed 11/10/2024.

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S. Papillary Thyroid Cancer Remodels the Genetic Information Processing Pathways. Genes 2024, 15, 621. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. Biomarkers, Master Regulators and Genomic Fabric Remodeling in a Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Genes 2020, 11, 1030. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Tuli, N.Y.; Iacobas, S.; Rasamny, J.K.; Moscatello, A.; Geliebter, J.; Tiwari, R.K. Gene master regulators of papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Oncotarget. 2017; 9(2):2410-2424. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Ede, N.; Iacobas, D.A. The Gene Master Regulators (GMR) Approach Provides Legitimate Targets for Personalized, Time-Sensitive Cancer Gene Therapy. Genes 2019, 10, 560. [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Song, N.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Shi, P.; Wang, Z.; Su, W.; Wang, H. A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis: causal association between chemokines and pan-carcinoma. Front Genet. 2023; 14:1285274. [CrossRef]

- Batson, J.; Maccarthy-Morrogh, L.; Archer, A.; Tanton, H.; Nobes, C.D. EphA receptors regulate prostate cancer cell dissemination through Vav2-RhoA mediated cell-cell repulsion. Biol Open. 2014; 3(6):453-62. [CrossRef]

- Batson, J.; Astin, J.W.; Nobes, C.D. Regulation of contact inhibition of locomotion by Eph-ephrin signalling. J. Microsc. 2013; 251, 232–241 10.1111/jmi.12024.

- Wang, C.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, Z.; Cai, H. The diagnostic or prognostic values of FADD in cancers based on pan-cancer analysis. Biomed Rep. 2023; 19(5):77. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xie, W.; Niu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Xie, W. Induced Necroptosis and Its Role in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10760. [CrossRef]

- McCann, C.; Crawford, N.; Majkut, J.; Holohan, C.; Armstrong, C.W.D.; Maxwell, P.J.; Ong, C.W.; LaBonte, M.J.; McDade, S.S.; Waugh, D.J. et al. Cytoplasmic FLIP(S) and nuclear FLIP(L) mediate resistance of castrate-resistant prostate cancer to apoptosis induced by IAP antagonists. Cell Death Dis. 2018; 9(11):1081. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Lai, T.H.; Zada, S.; Hwang, J.S.; Pham, T.M.; Yun, M.; Kim, D.R. Functional Linkage of RKIP to the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Autophagy during the Development of Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 273. [CrossRef]

- Sabater, A.; Sanchis, P.; Seniuk, R.; Pascual, G.; Anselmino, N.; Alonso, D.F.; Cayol, F.; Vazquez, E.; Marti, M.; Cotignola, J.; et al. Unmasking Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer with a Machine Learning-Driven Seven-Gene Stemness Signature That Predicts Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11356. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. Advanced Molecular Solutions for Cancer Therapy—The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the Biomarker Paradigm. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 1694-1699. [CrossRef]

- Manceau, C.; Fromont, G.; Beauval, J.-B.; Barret, E.; Brureau, L.; Créhange, G.; Dariane, C.; Fiard, G.; Gauthé, M.; Mathieu, R.; et al. Biomarker in Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4251. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, S.; Jalali, A.; O’Neill, A.; Murphy, L.; Gorman, L.; Reilly, A.-M.; Heffernan, Á.; Lynch, T.; Power, R.; O’Malley, K.J.; et al. Integrating Serum Biomarkers into Prediction Models for Biochemical Recurrence Following Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4162. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. The Genomic Fabric Perspective on the Transcriptome Between Universal Quantifiers and Personalized Genomic Medicine. Biol Theory 2016, 11, 123–137 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.-M.; Trikannad, A.K.; Vellanki, S.; Hussain, M.; Malik, N.; Singh, S.R.; Jillella, A.; Obulareddy, S.; Malapati, S.; Bhatti, S.A.; et al. Stem Cell Origin of Cancer: Clinical Implications beyond Immunotherapy for Drug versus Therapy Development in Cancer Care. Cancers 2024, 16, 1151. [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.-M.; Chen, J.Z.; Singh, S.R.; Maraboyina, S.; Gokden, N.; Hsu, P.-C.; Langford, T. Stem Cell Theory of Cancer: Clinical Implications for Cellular Metabolism and Anti-Cancer Metabolomics. Cancers 2024, 16, 624. [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S. Towards a Personalized Cancer Gene Therapy: A Case of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer & Oncol Res 2017; 5(3): 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Teleman, A.A. Role for Torsin in Lipid Metabolism. Dev Cell. 2016; 38(3):223-4. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, X.X.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Liang, Z.R.; Yan, X.; Wang, J. Construction and validation of a prognosis signature based on the immune microenvironment in gastric cancer. Front Surg. 2023; 10:1088292. [CrossRef]

- Muthu, M.; Chun, S.; Gopal, J.; Park, G.-S.; Nile, A.; Shin, J.; Shin, J.; Kim, T.-H.; Oh, J.-W. The MUDENG Augmentation: A Genesis in Anti-Cancer Therapy? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5583. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Shang, X.; Xie, J.; Xie, C.; Tang, Z.; Luo, Q.; Wu, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, N.; He, K. et al. Cooperation between IRTKS and deubiquitinase OTUD4 enhances the SETDB1-mediated H3K9 trimethylation that promotes tumor metastasis via suppressing E-cadherin expression. Cancer Lett. 2023; 575:216404. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, F.N.; Vasciaveo, A.; Antao, A.M.; Zou, M.; Di Bernardo, M.; de Brot, S.; Rodriguez-Calero, A.; Chui, A.; Wang, A.L.E.; Floc'h, N. et al. A forward genetic screen identifies Sirtuin1 as a driver of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- German, B.; Alaiwi, S.A.; Ho, K.L.; Nanda, J.S.; Fonseca, M.A.; Burkhart, D.L.; Sheahan, A.V.; Bergom, H.E.; Morel, K.L.; Beltran, H. et al. MYBL2 Drives Prostate Cancer Plasticity: Inhibiting Its Transcriptional Target CDK2 for RB1-Deficient Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res Commun. 2024; 4(9):2295-2307. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Tamukong, P.; Galvan, G.C.; Yang, Q.; De Hoedt, A.; Freeman, M.R.; You, S.; Freedland, S. Prostate cancers with distinct transcriptional programs in Black and White men. Genome Med. 2024; 16(1):92. [CrossRef]

- Moran, B.; Rahman, A.; Palonen, K.; Lanigan, F.T.; Gallagher, W.M. Master transcriptional regulators in cancer: discovery via reverse engineering approaches and subsequent validation. Cancer Res. 2017; 77:2186–90. [CrossRef]

- Sledziona, J.; Burikhanov, R.; Araujo, N.; Jiang, J.; Hebbar, N.; Rangnekar, V.M. The Tumor Suppressor Par-4 Regulates Adipogenesis by Transcriptional Repression of PPARγ. Cells 2024, 13, 1495. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Y.; He, F.; Gong, Z.; Yuan, F. Reynoutria multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke and its ingredient suppress lethal prostate cancer growth by inducing CDC25B-CDK1 mediated cell cycle arrest. Bioorg Chem. 2024; 152:107731. [CrossRef]

| CHEMOKINE SIGNALING | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | N | A | B | C |

| GNAI2 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | 58 | 69 | 96 | 68 |

| RAC3 | ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 3 (rho family, small GTP binding protein | 23 | 11 | 15 | 17 |

| STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 |

| GNAI2 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | 58 | 69 | 96 | 68 |

| CXCL14 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 14 | 5 | 33 | 36 | 23 |

| NFKBIA | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| GNAI2 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | 58 | 69 | 96 | 68 |

| NFKBIA | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| CXCL14 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 14 | 5 | 33 | 36 | 23 |

| GNAI2 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), alpha inhibiting activity polypeptide 2 | 58 | 69 | 96 | 68 |

| STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 |

| NFKBIA | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| TOLL-LIKE RECEPTOR SIGNALING | |||||

| STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 |

| MAP2K7 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 | 17 | 12 | 16 | 14 |

| PIK3R2 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 2 (beta) | 15 | 16 | 16 | 13 |

| NFKBIA | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| IRF7 | interferon regulatory factor 7 | 10 | 31 | 42 | 21 |

| PIK3R2 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 2 (beta) | 15 | 16 | 16 | 13 |

| NFKBIA | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| IRF7 | interferon regulatory factor 7 | 10 | 31 | 42 | 21 |

| STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 |

| STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 24 |

| NFKBIA | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 15 | 32 | 42 | 23 |

| IRF7 | interferon regulatory factor 7 | 10 | 31 | 42 | 21 |

| CHEMOKINE SIGNALING | Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | N | A | B | C |

| CCL15 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 | 2.75 | -1.91 | 0.37 | 0.10 |

| VAV2 | vav 2 guanine nucleotide exchange factor | 2.39 | -0.65 | -0.59 | 2.37 |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 1.73 | 0.01 | -1.00 | 0.35 |

| GNB1 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), beta polypeptide 1 | -0.40 | 4.18 | 0.06 | 0.63 |

| CXCL16 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 16 | 0.18 | 2.06 | 0.06 | -1.01 |

| FOXO3 | forkhead box O3 | 0.49 | 2.02 | 0.76 | -0.51 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | -0.72 | 0.38 | 2.59 | 0.33 |

| GRK5 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 | -1.24 | 0.26 | 1.55 | -1.07 |

| CCL16 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 16 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 1.46 | 3.65 |

| CCL16 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 16 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 1.46 | 3.65 |

| VAV2 | vav 2 guanine nucleotide exchange factor | 2.39 | -0.65 | -0.59 | 2.37 |

| PLCB1 | phospholipase C, beta 1 (phosphoinositide-specific) | -0.69 | -0.53 | 0.13 | 2.29 |

| TOLL-LIKE RECEPTOR SIGNALING | |||||

| PIK3R1 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 1 (alpha) | 1.56 | -0.24 | 1.09 | 1.34 |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 | 1.34 | 1.46 | -0.30 | 0.05 |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha | 1.30 | 0.62 | 0.10 | -0.31 |

| TYK2 | tyrosine kinase 2 | -1.85 | 2.95 | 0.74 | -1.71 |

| RIPK1 | receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | 1.05 | 2.79 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | -0.41 | 1.83 | 1.76 | 0.66 |

| TOLLIP | toll interacting protein | -1.05 | 1.29 | 2.67 | -1.19 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | -0.72 | 0.38 | 2.59 | 0.33 |

| IRF3 | interferon regulatory factor 3 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 2.20 | -0.36 |

| IRF5 | interferon regulatory factor 5 | -0.11 | 1.02 | 0.43 | 2.66 |

| MAP2K3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 | 0.75 | 1.34 | 0.54 | 1.83 |

| CCL5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | -1.87 | -0.52 | -0.76 | 1.66 |

| CHEMOKINE SIGNALING | Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | N | A | B | C |

| GNG13 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), gamma 13 | -2.90 | -0.81 | -1.12 | -0.25 |

| FGR | FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase | -2.82 | 0.11 | -0.02 | -0.23 |

| CXCL9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | -2.48 | -1.37 | 0.76 | -1.50 |

| CCL15 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 | 2.75 | -1.91 | 0.37 | 0.10 |

| CCL14 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 14 | -1.66 | -1.54 | -1.13 | -1.47 |

| CXCL11 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | -2.18 | -1.44 | -1.62 | -0.88 |

| CCL19 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 | -1.99 | 0.90 | -1.91 | -2.41 |

| CCL17 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 17 | -0.38 | -0.15 | -1.75 | 0.54 |

| CXCL11 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | -2.18 | -1.44 | -1.62 | -0.88 |

| CCL19 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 | -1.99 | 0.90 | -1.91 | -2.41 |

| NFKB1 | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | 0.91 | -0.82 | 0.64 | -2.23 |

| CXCL9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | -2.48 | -1.37 | 0.76 | -1.50 |

| TOLL-LIKE RECEPTOR SIGNALING | |||||

| CD86 | CD86 molecule | -3.10 | -0.49 | -1.12 | -1.41 |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | -2.70 | -1.56 | -0.83 | -1.92 |

| CXCL9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | -2.48 | -1.37 | 0.76 | -1.50 |

| TICAM2 | TICAM2 – TIR domain-containing adaptor molecule 2 | -0.83 | -2.27 | -0.63 | 0.17 |

| SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | -1.22 | -1.61 | -0.28 | 0.28 |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | -2.70 | -1.56 | -0.83 | -1.92 |

| CXCL11 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | -2.18 | -1.44 | -1.62 | -0.88 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor | -0.89 | -0.39 | -1.60 | -0.49 |

| CD86 | CD86 molecule | -3.10 | -0.49 | -1.12 | -1.41 |

| NFKB1 | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | 0.91 | -0.82 | 0.64 | -2.23 |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | -2.70 | -1.56 | -0.83 | -1.92 |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 | 0.15 | 1.34 | 0.64 | -1.90 |

| CHEMOKINE SIGNALING | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | N | A | B | C |

| CCL15 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 | 16.84 | 0.14 | 1.36 | 1.58 |

| PRKCD | protein kinase C, delta | 9.96 | 2.26 | 1.62 | 3.66 |

| VAV2 | vav 2 guanine nucleotide exchange factor | 9.22 | 2.32 | 1.57 | 3.79 |

| GNB1 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), beta polypeptide 1 | 1.94 | 34.15 | 1.51 | 4.54 |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 | 1.93 | 9.99 | 4.50 | 3.21 |

| TYK2 | tyrosine kinase 2 | 0.79 | 8.75 | 3.13 | 1.07 |

| CCR6 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.36 | 4.07 | 5.46 | 1.22 |

| CCR1 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | 1.98 | 4.40 | 4.88 | 3.32 |

| BCAR1 | BCAR1 scaffold protein, Cas family member | 1.94 | 3.30 | 4.81 | 4.51 |

| CCL16 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 16 | 4.03 | 4.20 | 2.63 | 14.72 |

| PLCB1 | phospholipase C, beta 1 (phosphoinositide-specific) | 1.13 | 2.48 | 1.47 | 9.67 |

| PREX1 | phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchange factor 1 | 2.14 | 1.87 | 2.03 | 8.07 |

| TOLL-LIKE RECEPTOR SIGNALING | |||||

| FADD | Fas (TNFRSF6)-associated via death domain | 7.28 | 5.03 | 2.24 | 0.42 |

| IKBKB | inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase beta | 5.86 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.21 |

| MAP2K4 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 | 5.80 | 2.35 | 2.23 | 3.08 |

| RIPK1 | receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | 2.60 | 11.86 | 3.01 | 5.31 |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | 1.20 | 9.79 | 2.58 | 5.27 |

| TOLLIP | toll interacting protein | 1.08 | 9.03 | 7.21 | 1.45 |

| TOLLIP | toll interacting protein | 1.08 | 9.03 | 7.21 | 1.45 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 1.50 | 2.69 | 6.40 | 3.53 |

| MAP3K7 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | 4.33 | 4.40 | 6.02 | 2.77 |

| IRF5 | interferon regulatory factor 5 | 1.83 | 4.40 | 2.99 | 11.34 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1, beta | 0.76 | 2.60 | 1.17 | 5.48 |

| RIPK1 | receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | 2.60 | 11.86 | 3.01 | 5.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).