Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

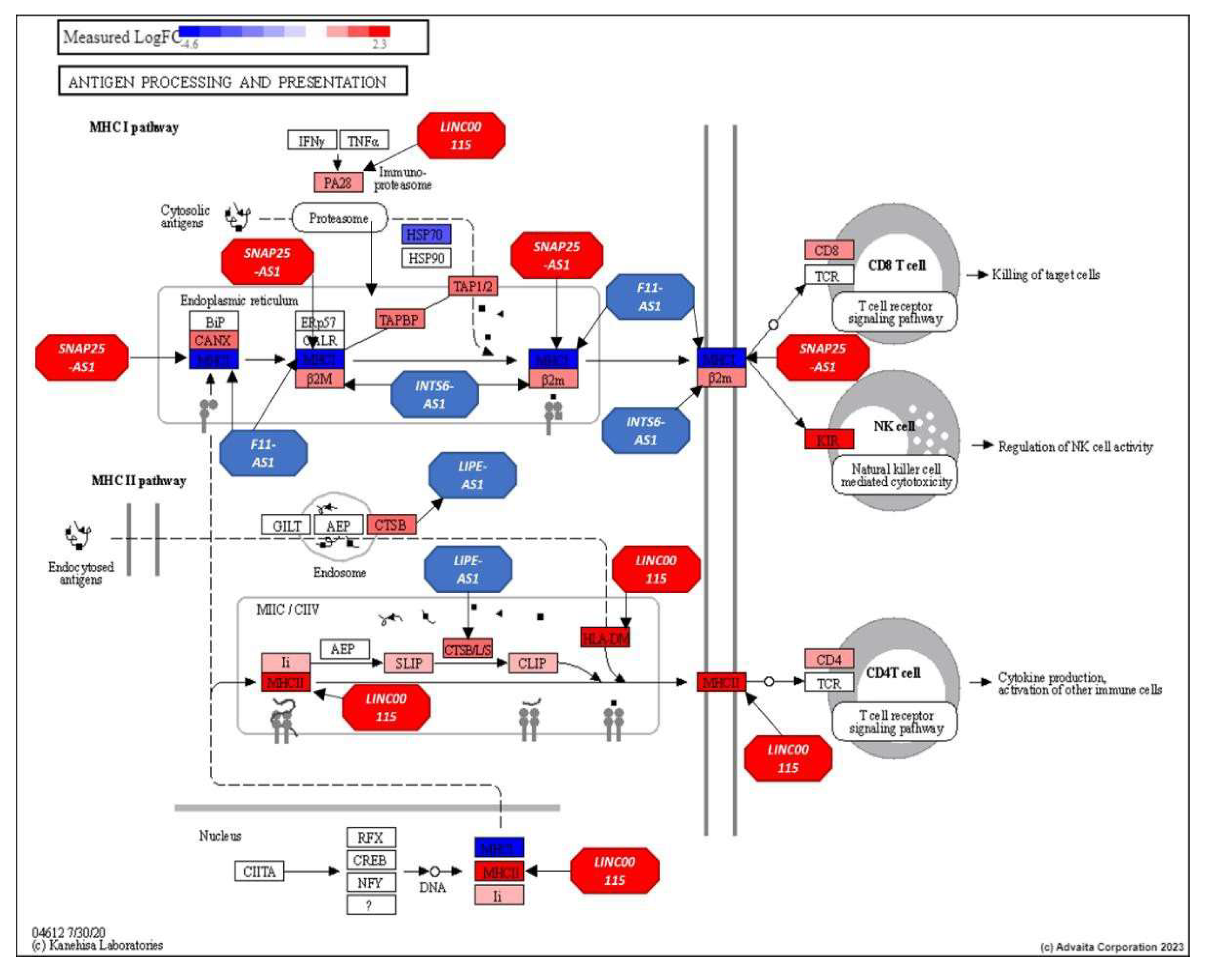

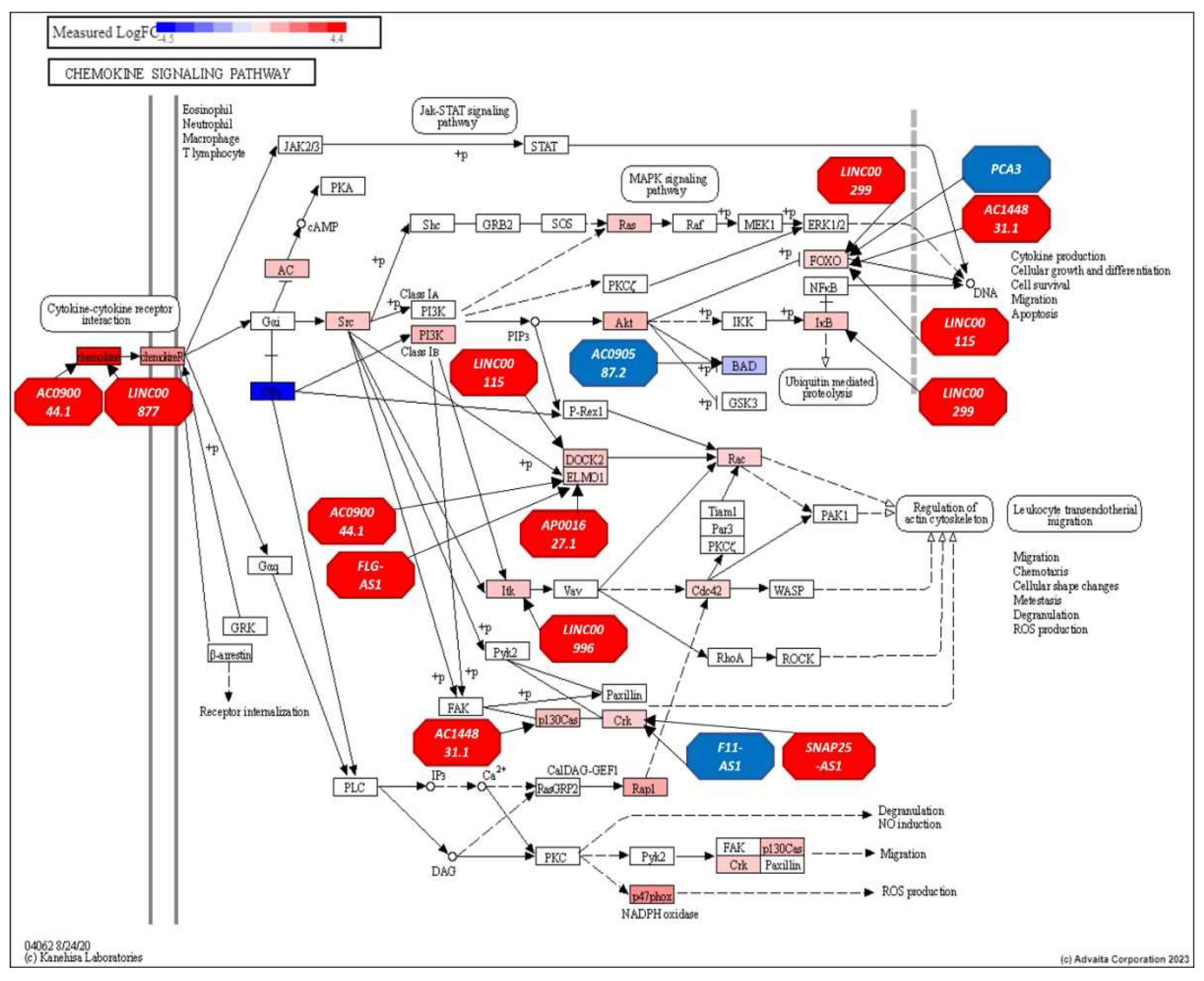

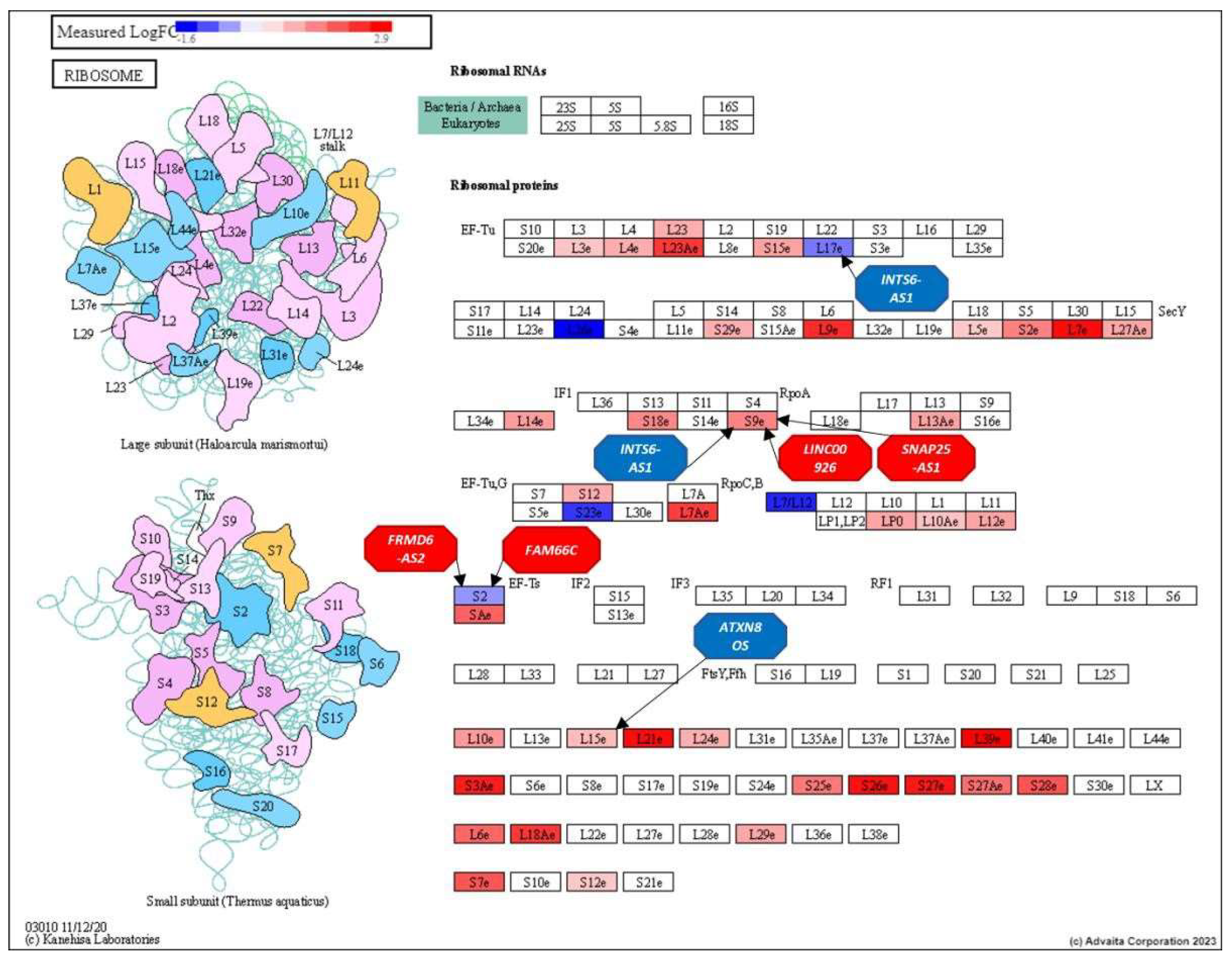

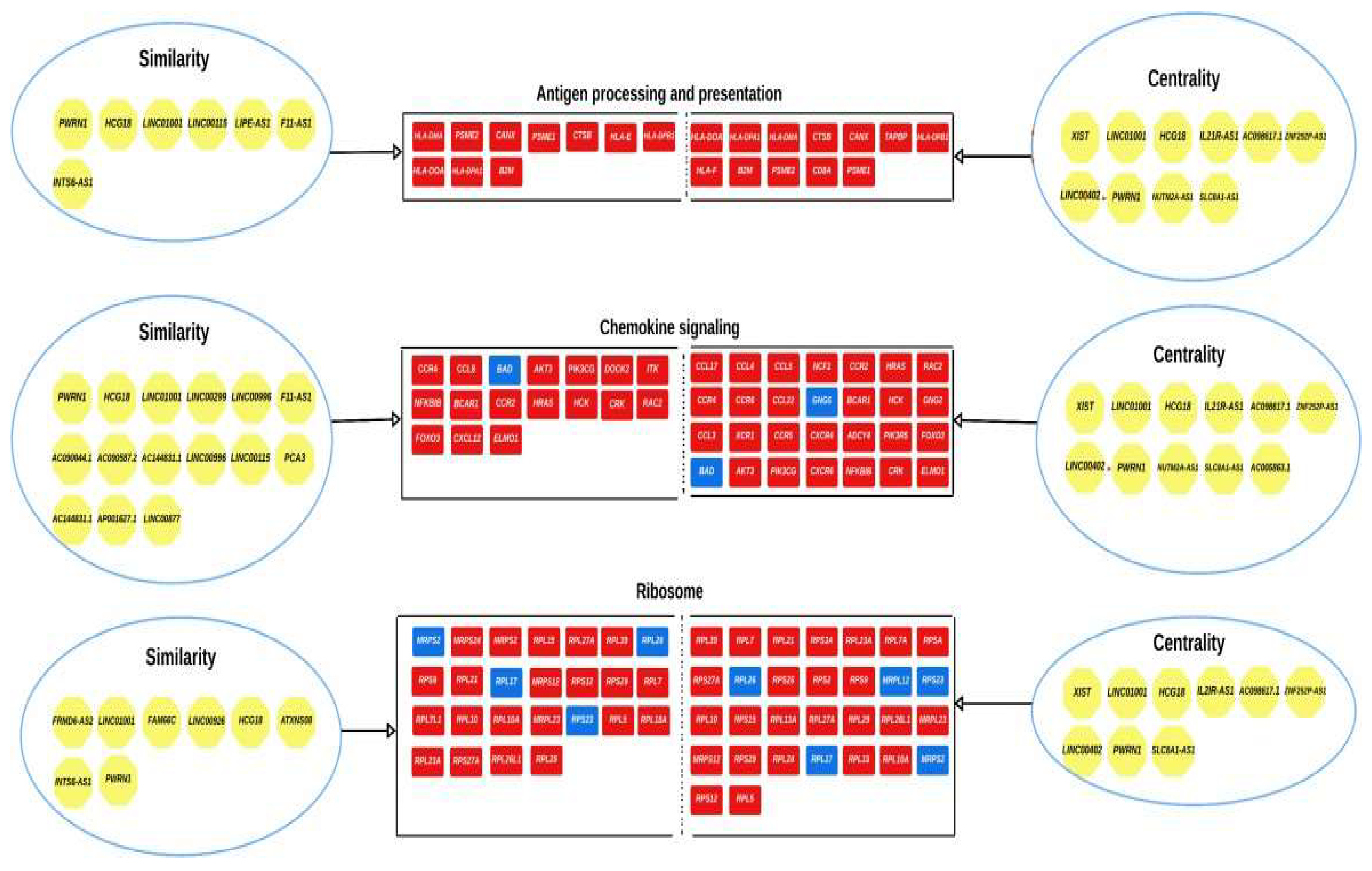

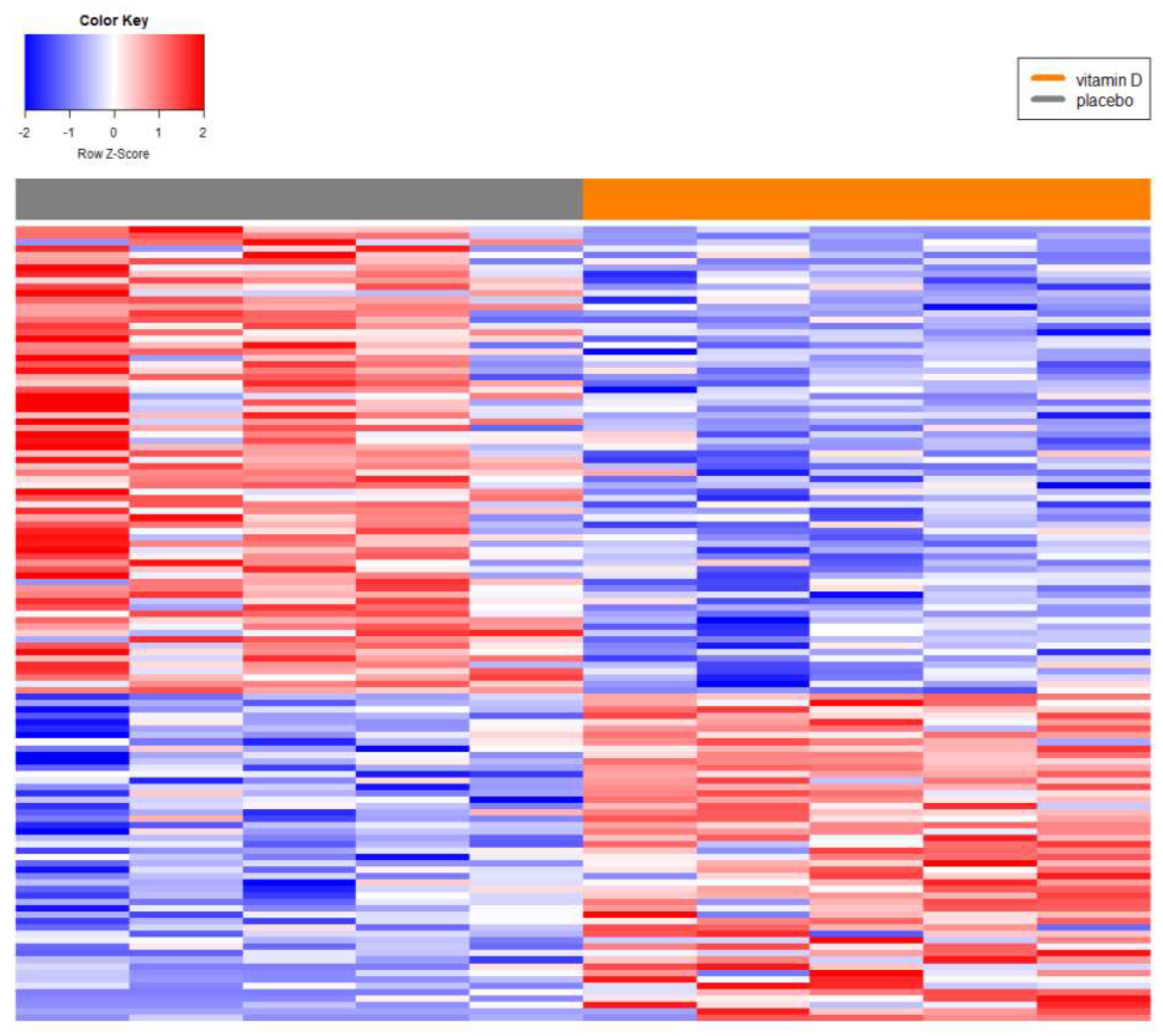

Background/Objectives: Prostate cancer (PC) is the most common non-cutaneous cancer in men globally, with significant racial disparities. Men of African descent (AF) are more likely to develop PC and face higher mortality compared to men of European descent (EU). The biological mechanisms underlying these differences remain unclear. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), recognized as key regulators of gene expression and immune processes, have emerged as potential contributors to these disparities. This study aimed to investigate the regulatory role of lncRNAs in localized PC in AF men relative to EUs and assess their involvement in immune response and inflammation. Methods: A systems biology approach was employed to analyze differentially expressed (DE) lncRNAs and their roles in prostate cancer (PC). Immune-related pathways were investigated through over-representation analysis of lncRNA-mRNA networks. The study also examined the effects of vitamin D supplementation on lncRNA expression in African descent (AF) PC patients, highlighting potential regulatory roles in immune response and inflammation. Results: Key lncRNAs specific to AF men were identified, with several implicated in immune response and inflammatory processes. Notably, 10 out of the top 11 ranked lncRNAs demonstrated strong interactions with immune-related genes. Pathway analysis revealed their regulatory influence on Antigen Processing and Presentation, Chemokine Signaling, and Ribosome pathways, suggesting critical roles in immune regulation. Conclusions: These findings highlight the pivotal role of lncRNAs in PC racial disparities, particularly through immune modulation. The identified lncRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets to address racial disparities in PC outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Sample Preparation

2.2. RNA-Seq Preparation and Differential Expression Analyses.

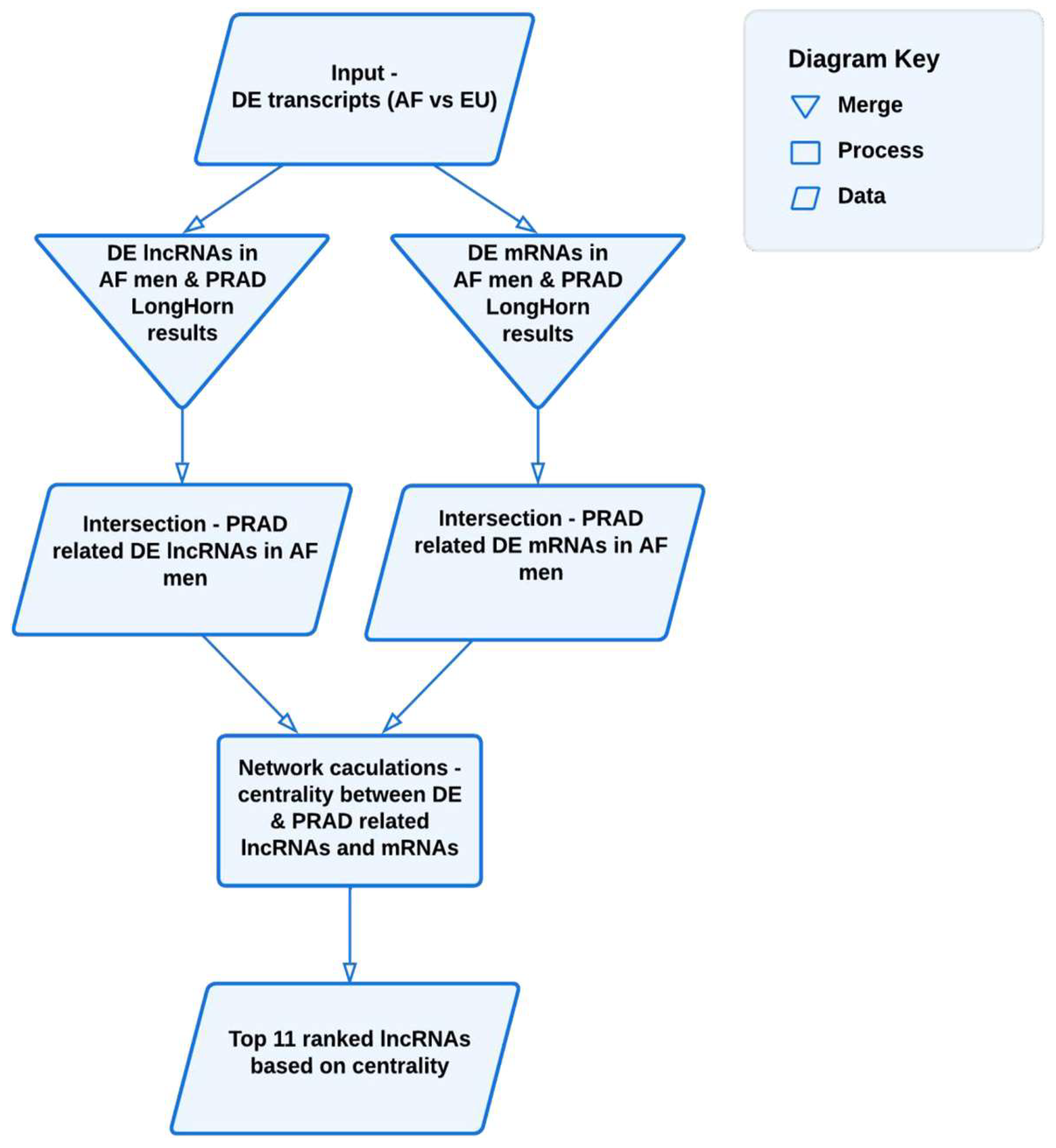

2.3. Network Analysis Using Centrality Metrics

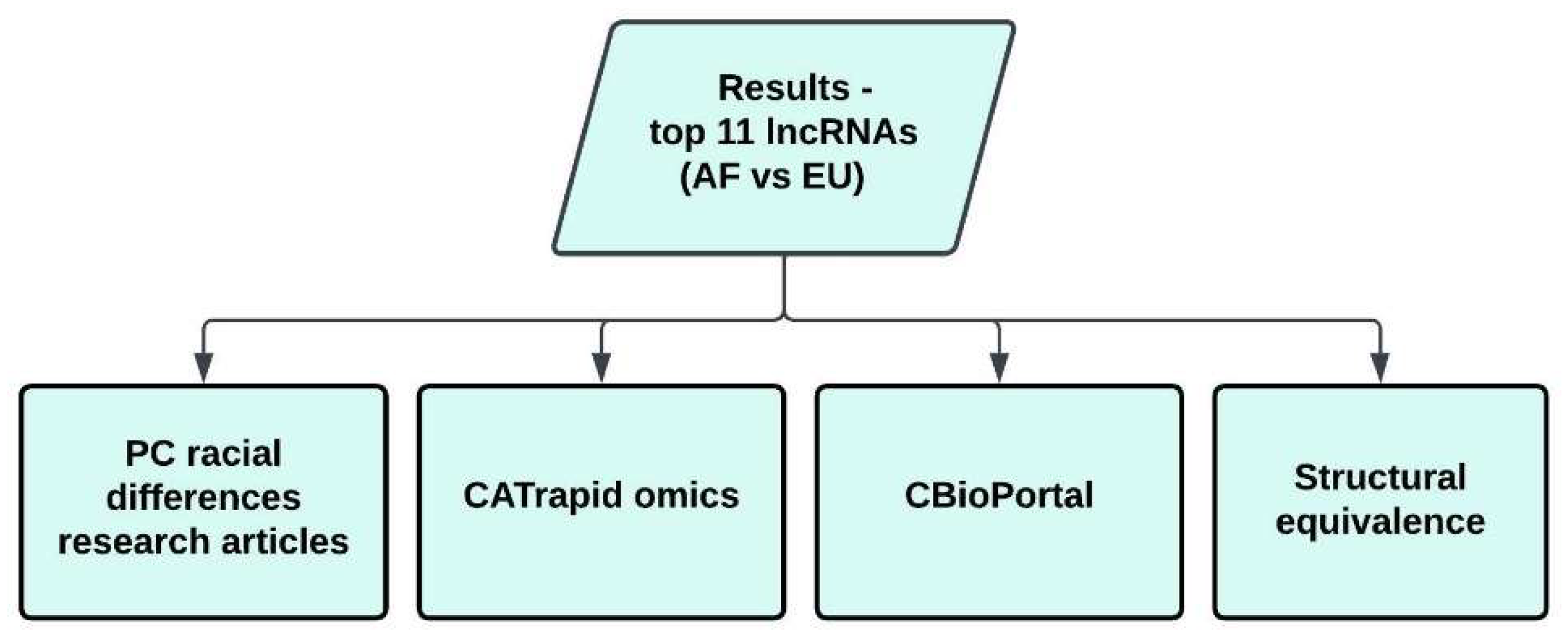

2.4. LncRNA Systems Biology Analyses

2.5. Association Analyses

2.6. CATrapid Omics

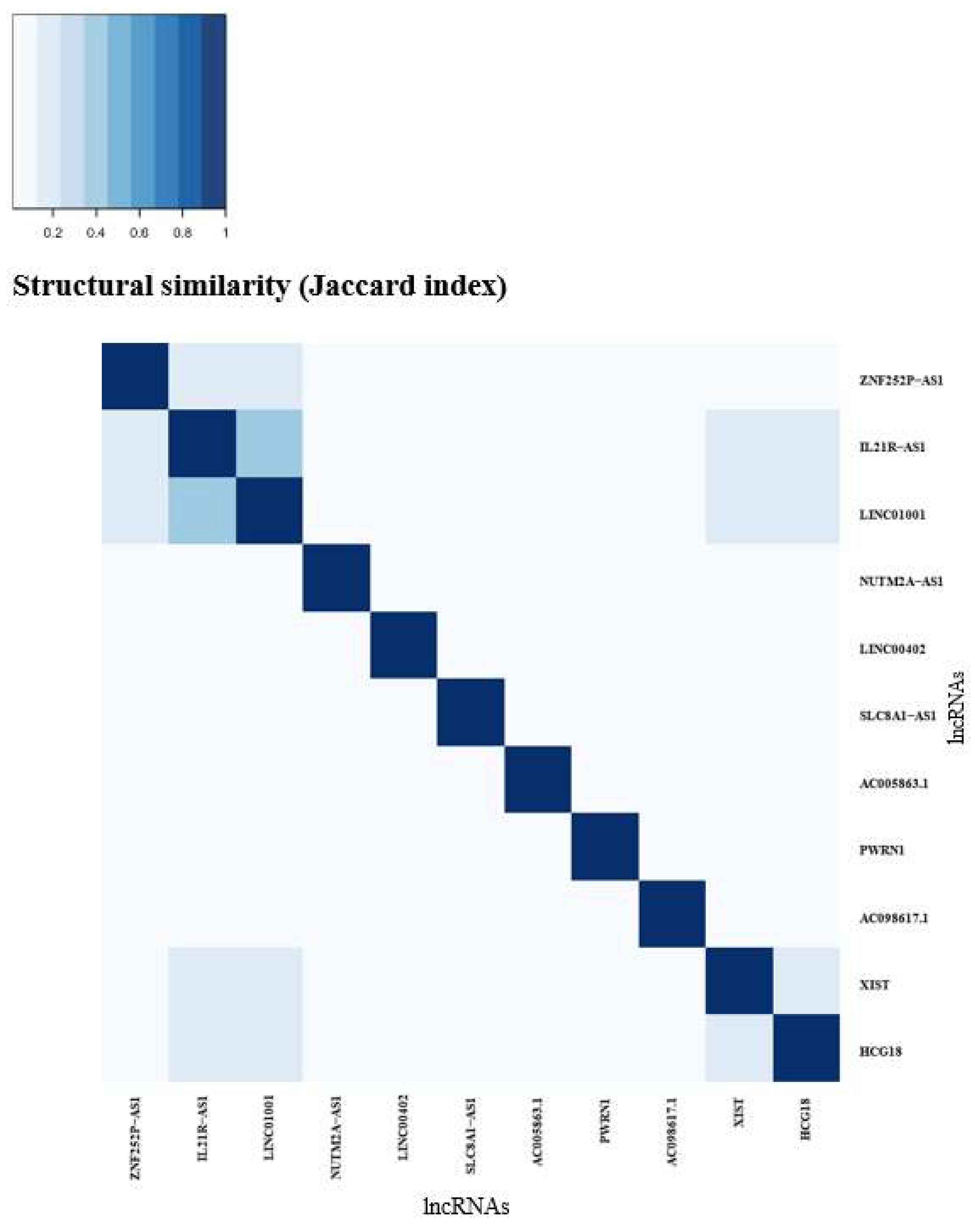

2.8. Structural Equivalence of Top 11 Ranking Central lncRNAs

2.9. Structural Equivalence Analysis of All lncRNAs

2.10. Systems Level Analyses

2.11. Gene Ontology Comparisons

3. Results

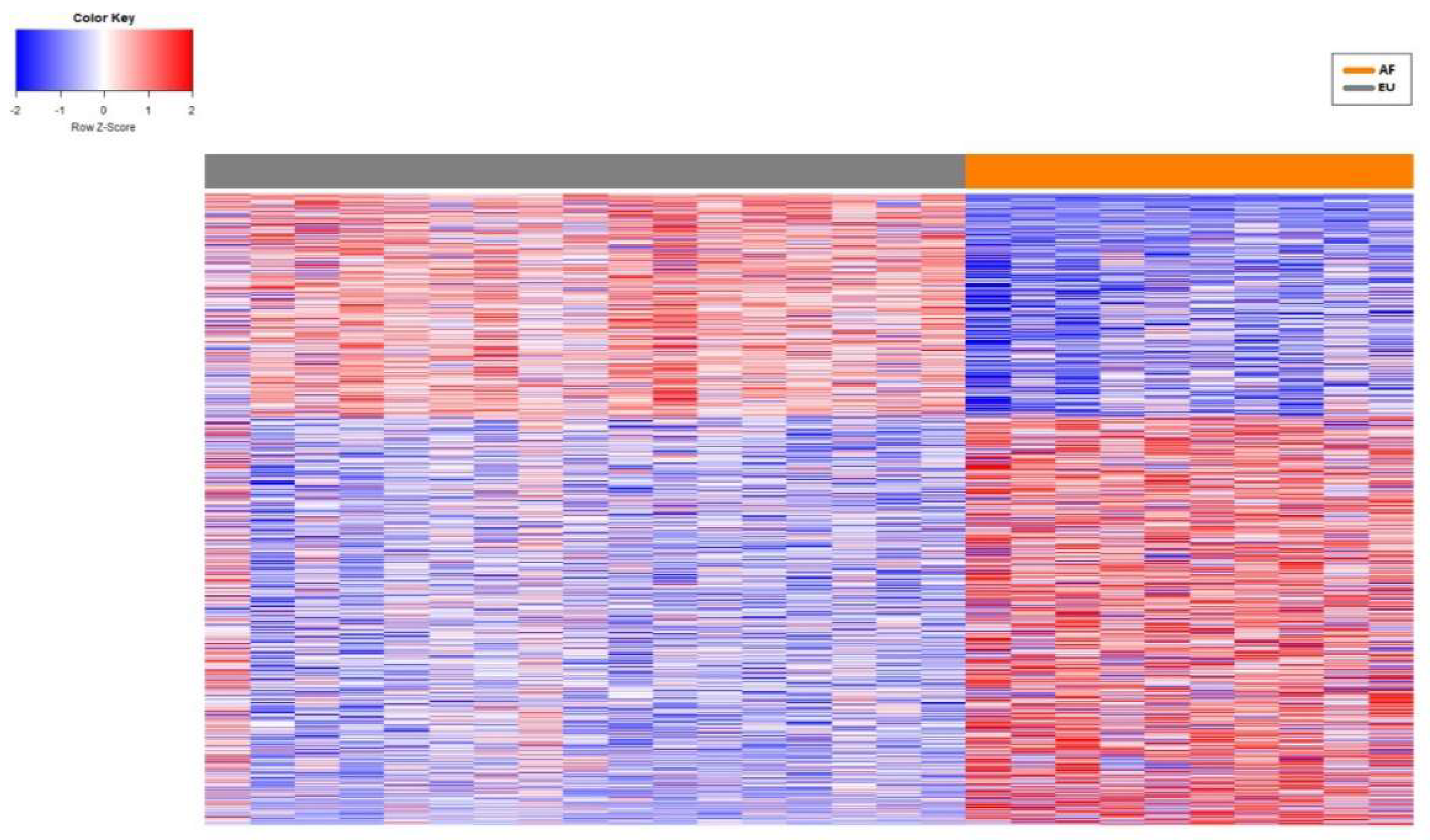

3.2. Network Analysis

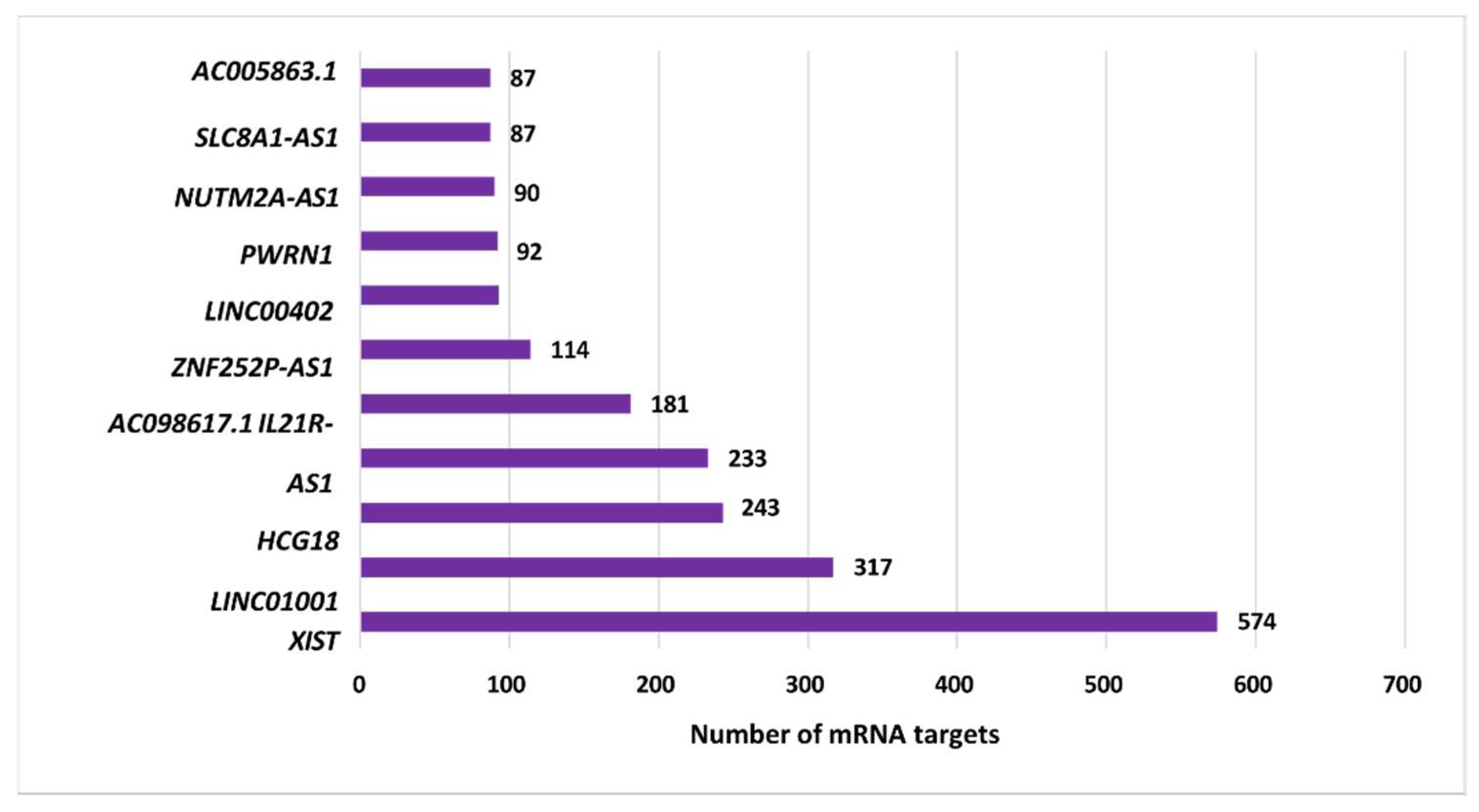

3.3. Analysis of the Top-Ranking lncRNAs

3.4. Structural Equivalence (AF vs EU)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, C.E.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019, 69, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.L.; Chinegwundoh, F. Update on prostate cancer in black men within the UK. Ecancermedicalscience 2014, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, D.; Packianathan, S.; Chen, A.M.; Vijayakumar, S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol 2016, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, C.H.; McDonald, J.; Vadaparampil, S.; Rice, L.; Jefferson, M. Conducting Precision Medicine Research with African Americans. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0154850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Chan, T.; Waldron, L.; Speers, C.; Feng, F.Y.; Ogunwobi, O.O.; Osborne, J.R. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Genomic Sequencing. JAMA Oncol 2016, 2, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.C.R.; Acuna, S.M.; Aoki, J.I.; Floeter-Winter, L.M.; Muxel, S.M. Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Regulation of Gene Expression: Physiology and Disease. Noncoding RNA 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Bajic, V.B.; Zhang, Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol 2013, 10, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misawa, A.; Takayama, K.I.; Inoue, S. Long non-coding RNAs and prostate cancer. Cancer Sci 2017, 108, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; da Silveira, W.A.; Kelly, R.C.; Overton, I.; Allott, E.H.; Hardiman, G. Long non-coding RNAs and their potential impact on diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy in prostate cancer: racial, ethnic, and geographical considerations. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2021, 21, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcala-Corona, S.A.; Sandoval-Motta, S.; Espinal-Enriquez, J.; Hernandez-Lemus, E. Modularity in Biological Networks. Front Genet 2021, 12, 701331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabasi, A.L.; Gulbahce, N.; Loscalzo, J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasman, D.; Fotuhi Siahpirani, A.; Roy, S. Network-based approaches for analysis of complex biological systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2016, 39, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silveira, W.A.; Renaud, L.; Hazard, E.S.; Hardiman, G. miRNA and lncRNA Expression Networks Modulate Cell Cycle and DNA Repair Inhibition in Senescent Prostate Cells. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silveira, W.A.; Renaud, L.; Simpson, J.; Glen, W.B., Jr.; Hazard, E.S.; Chung, D.; Hardiman, G. miRmapper: A Tool for Interpretation of miRNA⁻mRNA Interaction Networks. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golberk, J. Golberk, J. Introduction to Social Media Investigtion; Elsevier: 2015.

- Golberk, J. Golberk, J. Analyzing the Social Web; 2013.

- Fiscon, G.; Conte, F.; Farina, L.; Paci, P. Network-Based Approaches to Explore Complex Biological Systems towards Network Medicine. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R-bloggers. Network Centrality in R: An Introduction. Availabe online: https://www.r-bloggers.com/2018/12/network-centrality-in-r-an-introduction/ (accessed on.

- Ahonen, M.H.; Tenkanen, L.; Teppo, L.; Hakama, M.; Tuohimaa, P. Prostate cancer risk and prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (Finland). Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N.; Grant, W.B.; Willett, W.C. Does the High Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in African Americans Contribute to Health Disparities? Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardiman, G.; Savage, S.J.; Hazard, E.S.; Wilson, R.C.; Courtney, S.M.; Smith, M.T.; Hollis, B.W.; Halbert, C.H.; Gattoni-Celli, S. Systems analysis of the prostate transcriptome in African-American men compared with European-American men. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.M.; Till, C.A.; Tangen, C.M.; Goodman, P.J.; Song, X.; Torkko, K.C.; Kristal, A.R.; Peters, U.; Neuhouser, M.L. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of prostate cancer: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014, 23, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.G. Vitamin D, sunlight, and the epidemiology of prostate cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2013, 13, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.G. Vitamin D and the epidemiology of prostate cancer. Semin Dial 2005, 18, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddappa, M.; Hussain, S.; Wani, S.A.; White, J.; Tang, H.; Gray, J.S.; Jafari, H.; Wu, H.C.; Long, M.D.; Elhussin, I. , et al. African American Prostate Cancer Displays Quantitatively Distinct Vitamin D Receptor Cistrome-transcriptome Relationships Regulated by BAZ1A. Cancer Res Commun 2023, 3, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S.S. Vitamin D and African Americans. J Nutr 2006, 136, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, T.L.; Adams, J.S.; Henderson, S.L.; Holick, M.F. Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet 1982, 1, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2010.

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2017.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, D.; Haider, S.; Ballester, B.; Holland, R.; London, D.; Thorisson, G.; Kasprzyk, A. BioMart--biological queries made easy. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENSEMBL. Biotypes. Availabe online: https://www.ensembl.org/info/genome/genebuild/biotypes.html (accessed on.

- Chiu, H.S.; Somvanshi, S.; Patel, E.; Chen, T.W.; Singh, V.P.; Zorman, B.; Patil, S.L.; Pan, Y.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. , et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis of lncRNA Regulation Supports Their Targeting of Cancer Genes in Each Tumor Context. Cell Rep 2018, 23, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Kensler, K.H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Xu, M.; Pan, Y.; Long, M.; Montone, K.T. , et al. Integrative comparison of the genomic and transcriptomic landscape between prostate cancer patients of predominantly African or European genetic ancestry. PLoS Genet 2020, 16, e1008641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmatpanah, F.; Robles, G.; Lilly, M.; Keane, T.; Kumar, V.; Mercola, D.; Randhawa, P.; McClelland, M. RNA expression differences in prostate tumors and tumor-adjacent stroma between Black and White Americans. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayford, W.; Beksac, A.T.; Alger, J.; Alshalalfa, M.; Ahmed, M.; Khan, I.; Falagario, U.G.; Liu, Y.; Davicioni, E.; Spratt, D.E. , et al. Comparative analysis of 1152 African-American and European-American men with prostate cancer identifies distinct genomic and immunological differences. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, F.; Zanzoni, A.; Klus, P.; Marchese, D.; Cirillo, D.; Tartaglia, G.G. catRAPID omics: a web server for large-scale prediction of protein-RNA interactions. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2928–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachane, A.N.; Harrison, P.M. Mining mammalian transcript data for functional long non-coding RNAs. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prostate Adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Firehose Legacy).

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E. , et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, J.; Wankowicz, S.A.; Liu, D.; Gao, J.; Kundra, R.; Reznik, E.; Chatila, W.K.; Chakravarty, D.; Han, G.C.; Coleman, I. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nature genetics 2018, 50, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Cyrta, J.; Heller, G.; Prandi, D.; Armenia, J.; Coleman, I.; Cieslik, M.; Benelli, M.; Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 11428–11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Coleman, I.; Morrissey, C.; Zhang, X.; True, L.D.; Gulati, R.; Etzioni, R.; Bolouri, H.; Montgomery, B.; White, T. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nature medicine 2016, 22, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, Y.-M.; Schultz, N.; Lonigro, R.J.; Mosquera, J.-M.; Montgomery, B.; Taplin, M.-E.; Pritchard, C.C.; Attard, G. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2015, 161, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, K.A.; Yau, C.; Hinoue, T.; Wolf, D.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Drill, E.; Shen, R.; Taylor, A.M.; Cherniack, A.D.; Thorsson, V. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.S.; Wu, Y.-M.; Robinson, D.R.; Cao, X.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Khan, A.P.; Quist, M.J.; Jing, X.; Lonigro, R.J.; Brenner, J.C. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 2012, 487, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghici, S.; Khatri, P.; Tarca, A.L.; Amin, K.; Done, A.; Voichita, C.; Georgescu, C.; Romero, R. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res 2007, 17, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Bardes, E.E.; Aronow, B.J.; Jegga, A.G. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, W305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supek, F.; Bosnjak, M.; Skunca, N.; Smuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 2011, 6, e21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardou, P.; Mariette, J.; Escudie, F.; Djemiel, C.; Klopp, C. jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Pertea, G.; Trapnell, C.; Pimentel, H.; Kelley, R.; Salzberg, S.L. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 2013, 14, R36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, I.; Plummer, S.J.; Jorgenson, E.; Liu, X.; Rybicki, B.A.; Casey, G.; Witte, J.S. 8q24 and prostate cancer: association with advanced disease and meta-analysis. Eur J Hum Genet 2008, 16, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaspishvili, T.; Berman, D.M.; Ross, A.E.; Scher, H.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Squire, J.A.; Lotan, T.L. Clinical implications of PTEN loss in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2018, 15, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluri, R.T.K.; Audet-Walsh, É. Genomic deletion at 10q23 in prostate cancer: more than PTEN loss? Frontiers in oncology 2018, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitobe, Y.; Takayama, K.I.; Horie-Inoue, K.; Inoue, S. Prostate cancer-associated lncRNAs. Cancer Lett 2018, 418, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, T.; Cui, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, P.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, D. RNAInter in 2020: RNA interactome repository with increased coverage and annotation. Nucleic acids research 2020, 48, D189–D197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, P.; Chen, X.; Xie, R.; Xie, W.; Huang, L.; Dong, W.; Han, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, J.; Huang, J. , et al. A novel AR translational regulator lncRNA LBCS inhibits castration resistance of prostate cancer. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Prencipe, M.; Gallagher, W.M.; Watson, R.W. Commercialized biomarkers: new horizons in prostate cancer diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2015, 15, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.T. Urinary biomarkers for prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol 2015, 25, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.C.; Morgan, R.A.; Brown, M.; Overton, I.; Hardiman, G. The Non-coding Genome and Network Biology. In Systems Biology II, Springer: 2024; pp. 163-181.

- Nguyen, N.; Souza, T.; Kleinjans, J.; Jennen, D. Transcriptome analysis of long noncoding RNAs reveals their potential roles in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Noncoding RNA Res 2022, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Qi, M.; Fei, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, K. Long non-coding RNA XIST: a novel oncogene in multiple cancers. Mol Med 2021, 27, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balas, M.M.; Johnson, A.M. Exploring the mechanisms behind long noncoding RNAs and cancer. Noncoding RNA Res 2018, 3, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.S.; Ainiwaer, J.L.; Sheyhiding, I.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.W. Identification of key long non-coding RNAs as competing endogenous RNAs for miRNA-mRNA in lung adenocarcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2016, 20, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Ke, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Fang, S.; Lu, K. LINC01001 Promotes Progression of Crizotinib-Resistant NSCLC by Modulating IGF2BP2/MYC Axis. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 759267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ma, T.T.; Ma, Y.H.; Jiang, Y.F. LncRNA HCG18 contributes to nasopharyngeal carcinoma development by modulating miR-140/CCND1 and Hedgehog signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 10387–10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaad, Y.M. Clinical Role of Human Leukocyte Antigen in Health and Disease. Scand J Immunol 2015, 82, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wu, T.; Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, X. The long non-coding RNA HCG18 promotes the growth and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through sponging miR-1271 and upregulating MTDH/Wnt/beta-catenin. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Q.; He, X.; Wei, H.; Zhang, D. NOTCH1 regulates the proliferation and migration of bladder cancer cells by cooperating with long non-coding RNA HCG18 and microRNA-34c-5p. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 6596–6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Mo, J.; Pang, M.; Chen, Z.; Feng, F.; Xie, P.; Yang, B. Identification of HCG18 and MCM3AP-AS1 That Associate With Bone Metastasis, Poor Prognosis and Increased Abundance of M2 Macrophage Infiltration in Prostate Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2021, 20, 1533033821990064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, U.; Sarkar, S.; Suk, K.; Mohammad, O.; Baig, M.S.; Savai, R. Phytochemicals as modulators of M1-M2 macrophages in inflammation. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17937–17950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Ismail, N. M1 and M2 Macrophages Polarization via mTORC1 Influences Innate Immunity and Outcome of Ehrlichia Infection. J Cell Immunol 2020, 2, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Lu, K.; Hou, Y.; You, Z.; Shu, C.; Wei, X.; Wu, T.; Shi, N.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J. , et al. YY1 complex in M2 macrophage promotes prostate cancer progression by upregulating IL-6. J Immunother Cancer 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Tan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Oyang, L.; Tian, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, M.; Wang, H. , et al. Role of the NFkappaB-signaling pathway in cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz, D.; Zietara, N.; Uzel, G.; Weidemann, T.; Braun, C.J.; Diestelhorst, J.; Krawitz, P.M.; Robinson, P.N.; Hecht, J.; Puchalka, J. , et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the IL-21 receptor gene cause a primary immunodeficiency syndrome. J Exp Med 2013, 210, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, C.; Corbin, J.M.; Thibivilliers, S.; Webb, Z.D.; Zhao, Y.D.; Koster, J.; Fung, K.M.; Asch, A.S.; Wren, J.D.; Ruiz-Echevarria, M.J. A TMEFF2-regulated cell cycle derived gene signature is prognostic of recurrence risk in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gery, S.; Sawyers, C.L.; Agus, D.B.; Said, J.W.; Koeffler, H.P. TMEFF2 is an androgen-regulated gene exhibiting antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4739–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebali, S.; Davis, C.A.; Merkel, A.; Dobin, A.; Lassmann, T.; Mortazavi, A.; Tanzer, A.; Lagarde, J.; Lin, W.; Schlesinger, F. , et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature 2012, 489, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poliseno, L.; Marranci, A.; Pandolfi, P.P. Pseudogenes in Human Cancer. Front Med (Lausanne) 2015, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, L.; Mo, Y.Y. Role of Pseudogenes in Tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Rand, K.A.; Hazelett, D.J.; Ingles, S.A.; Kittles, R.A.; Strom, S.S.; Rybicki, B.A.; Nemesure, B.; Isaacs, W.B.; Stanford, J.L. , et al. Prostate Cancer Susceptibility in Men of African Ancestry at 8q24. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, M.A.; Butler, M.G.; Cataletto, M.E. Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. J Endocrinol Invest 2015, 38, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhuang, Z. LncRNA NUTM2A-AS1 positively modulates TET1 and HIF-1A to enhance gastric cancer tumorigenesis and drug resistance by sponging miR-376a. Cancer Med 2020, 9, 9499–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Andrieux, G.; Hasan, A.M.M.; Ahmed, M.; Hosen, M.I.; Rahman, T.; Hossain, M.A.; Boerries, M. Harnessing the tissue and plasma lncRNA-peptidome to discover peptide-based cancer biomarkers. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, K.; Liang, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, H. Identification of candidate genes that may contribute to the metastasis of prostate cancer by bioinformatics analysis. Oncol Lett 2018, 15, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L. A social matching system: using implicit and explicit information for personalized recommendation in online dating service. Queensland University of Technology, 2013.

- Mpakali, A.; Stratikos, E. The Role of Antigen Processing and Presentation in Cancer and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disis, M.L. Immune regulation of cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 4531–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.; Connors, T.J.; Farber, D.L. Human T Cell Development, Localization, and Function throughout Life. Immunity 2018, 48, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.E.; Nibbs, R.J.B. A guide to chemokines and their receptors. FEBS J 2018, 285, 2944–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, M.T.; Luster, A.D. Chemokines in cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2014, 2, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, Z.; Batai, K.; Farhat, R.; Shah, E.; Makowski, A.; Gann, P.H.; Kittles, R.; Nonn, L. Prostatic compensation of the vitamin D axis in African American men. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Naughton, D.P. Vitamin D in health and disease: current perspectives. Nutr J 2010, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.; Maseeh, A. Vitamin D: The "sunshine" vitamin. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2012, 3, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, T.; Kikuta, J.; Ishii, M. The Effects of Vitamin D on Immune System and Inflammatory Diseases. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.; Dasgupta, P.; Murphy, J.J. Prostate Cancer: The Role of Inflammation and Chemokines. Am J Pathol 2019, 189, 2119–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, M.; Dogra, N.; Kyprianou, N. Inflammation as a Driver of Prostate Cancer Metastasis and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, H.; Dong, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yi, Y.; Lin, C. A novel necroptosis-related lncRNAs signature for survival prediction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Medicine 2022, 101, e30621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, B.L.; Tummers, B.; Green, D.R. Crashing the computer: apoptosis vs. necroptosis in neuroinflammation. Cell Death & Differentiation 2019, 26, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, S.; Ba, Y.; Zhang, H. Identification of m6A-related lncRNAs as prognostic signature within colon tumor immune microenvironment. Cancer Reports 2023, 6, e1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.-l.; Xing, L.; Wang, L.; Song, W.-t.; Li, D.-b.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y.-w.; Liu, M.-m.; Ni, W.-j.; Zhang, P. LncRNA ADAMTS9-AS2 inhibits cell proliferation and decreases chemoresistance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma via the miR-27a-3p/FOXO1 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussemakers, M.J.; van Bokhoven, A.; Verhaegh, G.W.; Smit, F.P.; Karthaus, H.F.; Schalken, J.A.; Debruyne, F.M.; Ru, N.; Isaacs, W.B. DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 5975–5979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O'Malley, P.G.; Nguyen, D.P.; Al Hussein Al Awamlh, B.; Wu, G.; Thompson, I.M.; Sanda, M.; Rubin, M.; Wei, J.T.; Lee, R.; Christos, P. , et al. Racial Variation in the Utility of Urinary Biomarkers PCA3 and T2ERG in a Large Multicenter Study. J Urol 2017, 198, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Mesa, M.D. Vitamin D: Classic and Novel Actions. Ann Nutr Metab 2018, 72, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knights, A.J.; Funnell, A.P.; Crossley, M.; Pearson, R.C. Holding Tight: Cell Junctions and Cancer Spread. Trends Cancer Res 2012, 8, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.C.; Davis, T.P. Calcium modulation of adherens and tight junction function: a potential mechanism for blood-brain barrier disruption after stroke. Stroke 2002, 33, 1706–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CbioPortal Datasets queried |

|---|

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (MSK/DFCI, Nature Genetics 2018)[47] |

| Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma (SU2C/PCF Dream Team, PNAS 2019)[48] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (Fred Hutchinson CRC, Nat Med 2016)[49] |

| Metastatic Prostate Cancer (SU2C/PCF Dream Team, Cell 2015)[50] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Firehose Legacy)[45] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (TCGA, Cell 2015)[51] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas)[52] |

| Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma (MCTP, Nature 2012)[53] |

| Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer (Multi-Institute, Nat Med 2016) [611] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (Broad/Cornell, Cell 2013) [612] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (Broad/Cornell, Nat Genet 2012) [613] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (CPC-GENE, Nature 2017) [614] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (MSK, Cancer Cell 2010) [615] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (MSK, PNAS 2014) [616] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma (SMMU, Eur Urol 2017) [617] |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma Organoids (MSK, Cell 2014) [618] |

| Prostate Cancer (MSK, JCO Precis Oncol 2017) [608] |

| Gene Ontology Biological Process |

p-value | q-value FDR B&H |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation of immune system process | 1.686 x 10^-15 | 6.107 x 10^-12 |

| T cell migration | 3.414 x 10^-3 | 3.264 x 10^-2 |

| Regulation of immune response | 2.456 x 10^-12 | 1.776 x 10^-9 |

| Leukocyte activation | 1.242 x 10^-12 | 1.125 x 10^-9 |

| Regulation of defense response | 4.105 x 10^-5 | 8.801 x 10^-4 |

| Top ranking lncRNAs | Number of mRNA interactions |

Chromosome location |

|---|---|---|

| XIST | 574 | Xq13.2 |

| LINC01001 | 317 | 11p15.5 |

| HCG18 | 243 | 6p22.1 |

| IL21R-AS1 | 233 | 16p12.1 |

| AC098617.1 | 181 | 2q32.3 |

| ZNF252P-AS1 | 114 | 8q24.3 |

| LINC00402 | 93 | 13q22.1 |

| PWRN1 | 92 | 15q11.2 |

| NUTM2A-AS1 | 90 | 10q23.2 |

| SLC8A1-AS1 | 87 | 2p22.1 |

| AC005863.1 | 87 | 17p12 |

| Article | LncRNA | Differentially expressed | FDR | Up or down regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al. 2020 [40] | AC098617.1 | Yes | 0.01 | Not defined |

| Yuan et al. 2020 [40] | LINC00402 | Yes | 0.01 | Not defined |

| Yuan et al. 2020 [40] | SLC8A1-AS1 | Yes | 0.01 | Not defined |

| Yuan et al. 2020 [40] | AC005863.1 | Yes | 0.01 | Not defined |

| Rayford, et al. 2021 [42] | LINC01001 | Yes | 0.02 | Not defined |

| Rayford, et al. 2021 [42] | AC098617.1 | Yes | 0.02 | Not defined |

| lncRNA (A) | lncRNA (B) |

Neither | A Not B |

B Not A |

Both | Log2 Odds Ratio | p- Value | q- Value | Tendency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIST | IL21R- AS1 | 4000 | 38 | 14 | 4 | >3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | Co- occurrence |

| HCG18 | ZNF252P- AS1 | 3715 | 54 | 272 | 15 | 1.924 | <0.001 | 0.001 | Co- occurrence |

| NUTM2A- AS1 | SLC8A1- AS1 | 3967 | 72 | 13 | 4 | >3 | <0.001 | 0.003 | Co- occurrence |

| IL21R- AS1 | NUTM2A- AS1 | 3965 | 15 | 73 | 3 | >3 | 0.004 | 0.038 | Co- occurrence |

| lncRNAs identified using structural equivalence analysis | Chromosome location |

|---|---|

| AC104024.1 | 17p11.2 |

| AC084125.4 | 8q24.3 |

| LINC00877 | 3p13 |

| DNM3OS | 1q24.3 |

| LINC00539 | 13q12.11 |

| ATP1B3-AS1 | 3q23 |

| FGF13-AS1 | Xq26.3 |

| AC107079.1 | 2q37.3 |

| GK-AS1 | Xp21.2 |

| COL4A2-AS1 | 13q34 |

| FRMD6-AS2 | 14q22.1 |

| HIF1A-AS2 | 14q23.2 |

| AP001627.1 | 3q13.12 |

| LINC00882 | 3q13.12 |

| LINC00987 | 12p13.31 |

| ATXN8OS | 13q21.33 |

| AC090587.2 | 10q24.2 |

| PCA3 | 9q21.2 |

| PCCA-AS1 | 13q32.3 |

| RAI1-AS1 | 17p11.2 |

| LINC01068 | 13q31.1 |

| LINC00887 | 3q29 |

| HLCS-IT1 | 21q22.13 |

| DDX11-AS1 | 12p11.21 |

| AC144831.1 | 17q25.3 |

| LINC00299 | 2p25.1 |

| LINC00115 | 1p36.33 |

| AP000439.2 | 11q13.3 |

| FAM66C | 12p13.31 |

| HPN-AS1 | 13q13.11 |

| LINC00313 | 21q22.3 |

| LUCAT1 | 5q14.3 |

| LINC00926 | 15q21.3 |

| ZBTB20-AS4 | 3q13.31 |

| LINC00494 | 20q13.13 |

| CAMTA1-IT1 | 1p36.23 |

| MIR497HG | 17p13.1 |

| LIPE-AS1 | 19q13.2 |

| FLG-AS1 | 1q21.3 |

| SLC8A1-AS1 | 2p22.1 |

| SNAP25-AS1 | 20p12.2 |

| F11-AS1 | 4q35.2 |

| INTS6-AS1 | 13q13.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).