Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

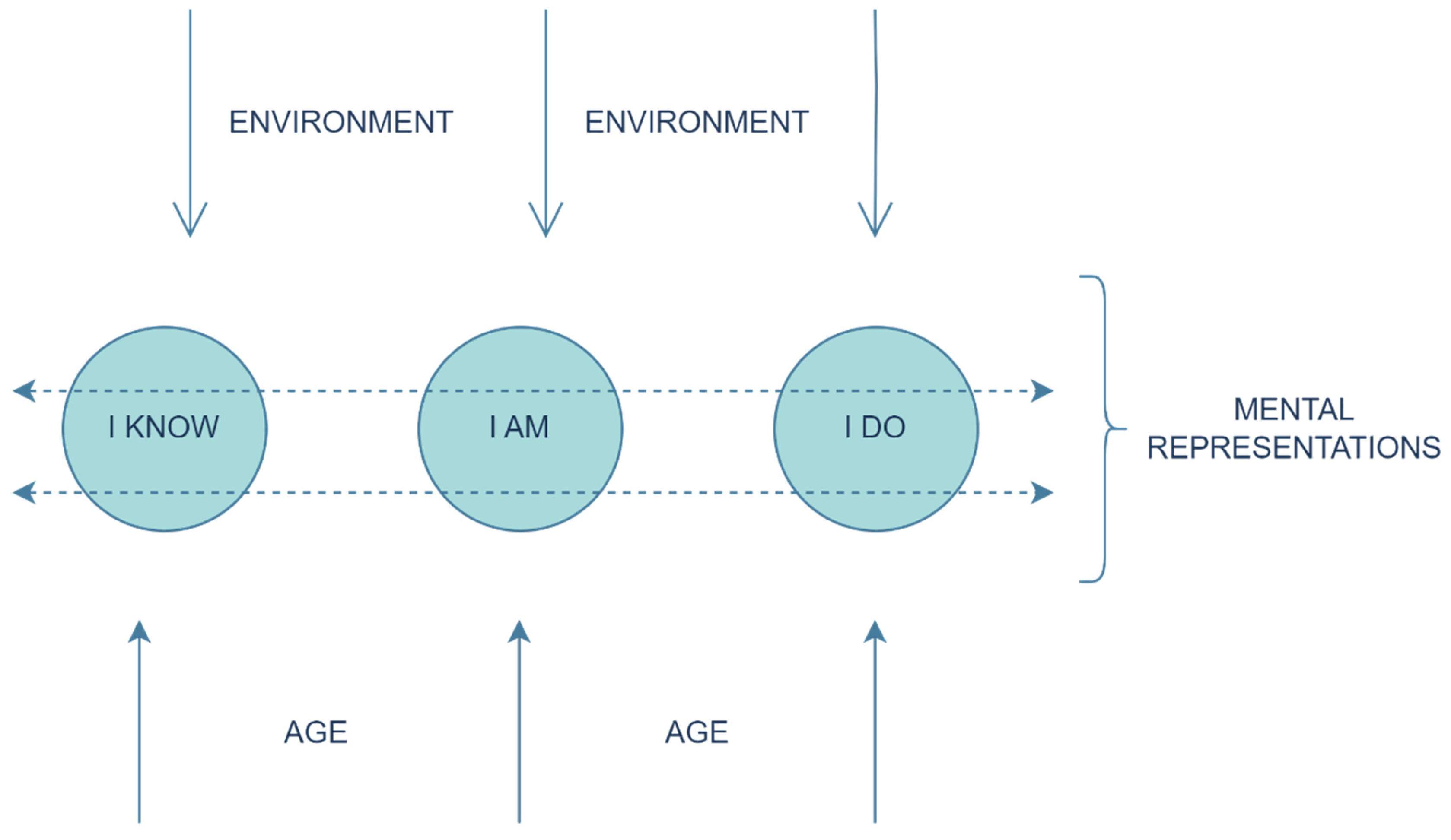

2.1. Schema—Mental Processes—Mental Representations

2.2. Theory of Wall, McClements, Bouffard, Findlay & Taylor (1985)

2.3. Motivation Theories—Motor Competence

3. Dynamic Motor Intervention Model

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Methodology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Kelso, J. A. S. Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior, 1st Ed. The MIT Press, 1995.

- Thelen, E.; Kelso, J. S.; Fogel, A. Self-organizing systems and infant motor development. Developmental Review, 1987, 7(1), pp. 39–65. [CrossRef]

- Thelen, E. Motor development as foundation and future of developmental psychology. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 2000, 24(4), pp. 385–397. [CrossRef]

- Thelen, E. Dynamic Systems Theory and the Complexity of Change. Dialogues, 2005, 15(2), pp. 255-283. [CrossRef]

- Inhelder, B.; Sinclair, H.; Bovet, M. Learning and the Development of Cognition, 1st ed. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1974.

- Fustana, A. The Cognitive Base and Representation of Intelligent Learners. In proceedings of the 4ου Panhellenic Conference of Education Sciences, Athens, Greece, 20- 22/6/2014, p. 615- 624. [CrossRef]

- Wall, A.E.; McClements, J; Bouffard, M.; Findlay, H.; Taylor, M.J. Approach to Motor Development: Implications for the Physically Awkward. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 1985, 2, pp. 21- 42.

- Siegel, L.S.; Brainerd, C.J., Eds. Alternatives to Piaget: Critical Essays on the Theory, 1st ed. New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- Chi, M. T. H.; Roscoe, R. D. The processes and challenges of conceptual change. In Reconsidering conceptual change: Issues in theory and practice, 1st ed.; M. Limon; L. Mason, Eds.; Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers 2002; pp. 3-27.

- Beilin, H.; Fireman, G. The foundation of Piaget’s theories: mental and physical. Advances in child development and behavior, 1999, 27, 221-246. [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulos, I. Developmental Psychology. Volume 1: Prenatal period—infancy. Athens, 1985.

- Maratou, O. Notes for the course of Developmental Psychology,University of Athens, 1990.

- Müller, U.; Sokol, B.; Overton, W.F. Reframing a Constructivist Model of the Development of Mental Representation: The Role of Higher-Order Operations. Developmental Reports, 1998, 18, pp.155- 201. [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Slone, M.; Dar, R. Which Way Cognitive Development? Piagetian and the Domain-Specific Research Programs. Theory & psychology, 2000, 10(3), pp. 353-373. [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.T.H. Knowledge structure and memory development. In Children’s thinking: What develops?, 1st ed.; R. Siegler, Ed.; Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1978; pp. 73-96.

- Demetriou, A.; Efklides, A. Structure and sequence of formal and postformal thought: General patterns and individual differences. Child Development, 1985, 56, pp. 1062-1091. [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. Domain-Generality versus Domain-Specificity: The Life and Impending Death of a False Dichotomy. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 1989, 35(1), pp. 115–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23086427.

- Siegler, R. S. How domain-general and domain-specific knowledge interact to produce strategy choices. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 1989, 35(1), pp. 1–26.

- Brown, A.L.; Bransford, J.D.; Ferrara, R.A.; Campione, J.C. Learning, Remembering, And Understanding. Technical Report No. 244, Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois, 1982, pp 1- 257. Retrieved 01/06/2018 from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/17511/ctrstreadtechrepv01982i00244opt.pdf.

- Koutsouki, D. Special physical education: Theory and practice; Athens, 1997.

- Koutsouki- Koskina, D. The effect of instruction on tracking performance at two levels of skill: A knowledge- Based Approach, Doctoral dissertation, Alberta CA: University of Alberta, 1986.

- Efklides, A. Metacognition and affect: What can metacognitive experiences tell us about the learning process? Educational Research Review, 2006,1, p.p. 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Reeve, R. A.; Brown, A. L. Metacognition reconsidered: implications for intervention research. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 1985, 13(3), pp. 343-356. [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. Metacognitive experiences in problem solving: Metacognition, motivation, and self-regulation. In Trends and prospects in motivation research, 1st ed.; A. Efklides; J. Kuhl; R. M. Sorrentino, Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001, pp. 297–323. [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Brown, A. L. Metacognitive skills and reading. In Handbook of Reading Research; P. D. Pearson; R. Barr; M. L. Kamil; P. Mosenthal, Eds; New York: Longman, 1984; pp. 353-394.

- Rudisill, M. E.; Mahar, M. T.; Meaney, K. S. The relationship between children’s Perceived and actual motor competence. Perceptual and motor skills, 1993, 76(3), pp. 895-906. [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. Effective Motivation Reconsidered: Toward a Developmental Model. Development, 1978, 21(1), pp. 34-64. [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children, Child Development, 1982, 53(1), pp. 87-97. [CrossRef]

- Fry, M.D; Duda, J.L. A Developmental Examination of Children’s Understanding of Effort and Ability in the Physical and Academic Domains, Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 1997, 68(4), pp. 331-344. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J. G. The Development of the Concepts of Effort and Ability, Perception of Academic Attainment, and the Understanding That Difficult Tasks Require More Ability. Child Development, 1978, 49(3), pp. 800-814. [CrossRef]

- Fry, M. D. (2000). A developmental examination of children’s understanding of task difficulty in the physical domain. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 2000, 12(2), pp. 180–202. [CrossRef]

- Folmer, A. S.; Cole, D. A.; Sigal, A. B.; Benbow, L. D.; Satterwhite, L. F.; Swygert, K. E.; Ciesla, J. A. Age-related changes in children’s understanding of effort and ability: implications for attribution theory and motivation. Journal of experimental child psychology, 2008, 99(2), pp. 114-134. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.C.T.; Moran, J.; Drury, B.; Venetsanou, F.; Fernandes, J.F.T. Actual vs. Perceived Motor Competence in Children (8–10 Years): An Issue of Non-Veridicality. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2018, 3, 20. [CrossRef]

- Liong, G. H. E.; Ridgers, N. D.; Barnett, L. M. Associations between Skill Perceptions and Young Children’s Actual Fundamental Movement Skills. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 2015, 120(2), 591-603. [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: an emergent relationship. Quest, 2008, 60(2), pp. 290-306. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M. J.; Jones, V.; O’Brien, W.; Barnett, L. M.; Eyre, E. Self-Perceived and Actual Motor Competence in Young British Children. Perceptual and motor skills, 2018, 125(2), pp. 251-264. [CrossRef]

- Estevan, I.; Barnett, L. M. Considerations Related to the Definition, Measurement and Analysis of Perceived Motor Competence. Sports Med., 2018, 48(12), pp. 2685-2694. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G., Luz, C., Martins, R., & Cordovil, R. Differences between Estimation and Real Performance in School-Age Children: fundamental movement skills. Child Development Research, 2016, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, O.; Belton, S.; O’Brien, W. The Relationship between Actual Fundamental Motor Skill Proficiency, Perceived Motor Skill Confidence and Competence, and Physical Activity in 8–12-Year-Old Irish Female Youth. Sports, 2017, 5, 74. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Close Interrelation of Motor Development and Cognitive Development and of the Cerebellum and Prefrontal Cortex. Child Development, 2000, 71, pp. 44-56. [CrossRef]

- Chi, M. T. H. Two Approaches to the Study of Experts’ Characteristics. In The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance, 1st ed.; K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman, Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2006; pp. 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Kryza, K. Practical Strategies for Developing Executive Functioning Skills for ALL Learners in the Differentiated Classroom. In Handbook of Executive Functioning; 1st ed; Goldstein, S. & Naglieri, J.A., Eds.; Springer, New York, NY, 2014; pp. 523–554. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).