1. Introduction

Primary energy sources such as coal, oil and natural gas have restricted the sustainable development of human beings because of their non-renewability, scarcity and many ecological and environmental problems. Considering the rational utilization of resources and sustainable development strategies, it is urgent to seek environmentally friendly renewable resources and realize the resource utilization of waste [

1,

2,

3]. Biomass, as a representative new energy source, is the only renewable green organic carbon source on the earth, which can be used as an oil substitute to produce a variety of fuels, chemicals and carbon-based materials, which has attracted wide attention from people [

4].

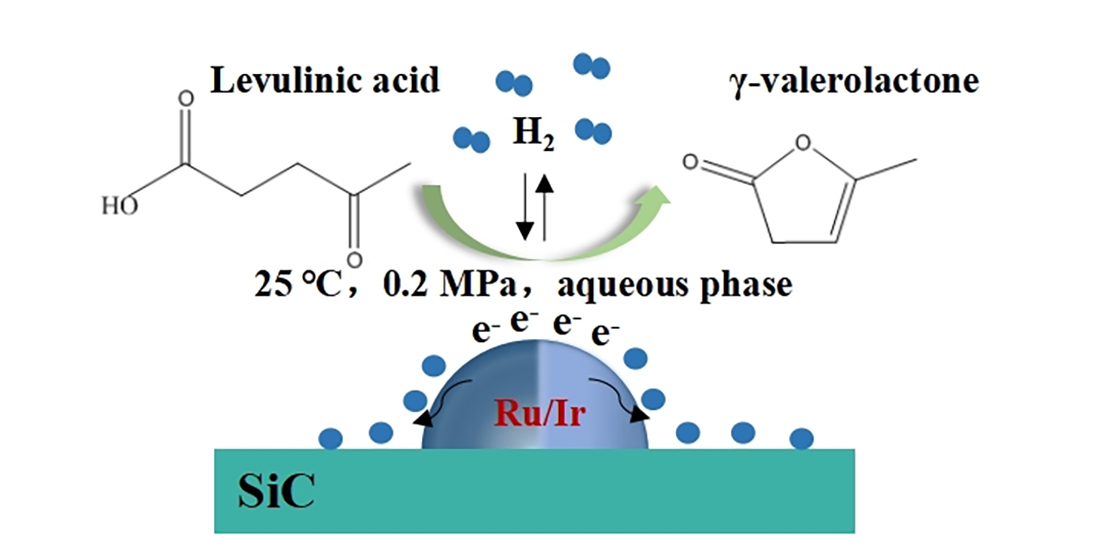

Lignocellulose, the main component of biomass, can be converted into a variety of platform compounds, and then into a series of high value-added chemicals by hydrogenation, deoxygenation, decarbonylation and so on. Levulinic acid (LA), an important biomass-based platform compound of lignocellulose obtained by multistep hydrolysis, which can be used to prepare medicines, resins, spices, coatings and the synthesis of high value-added chemicals [

5,

6,

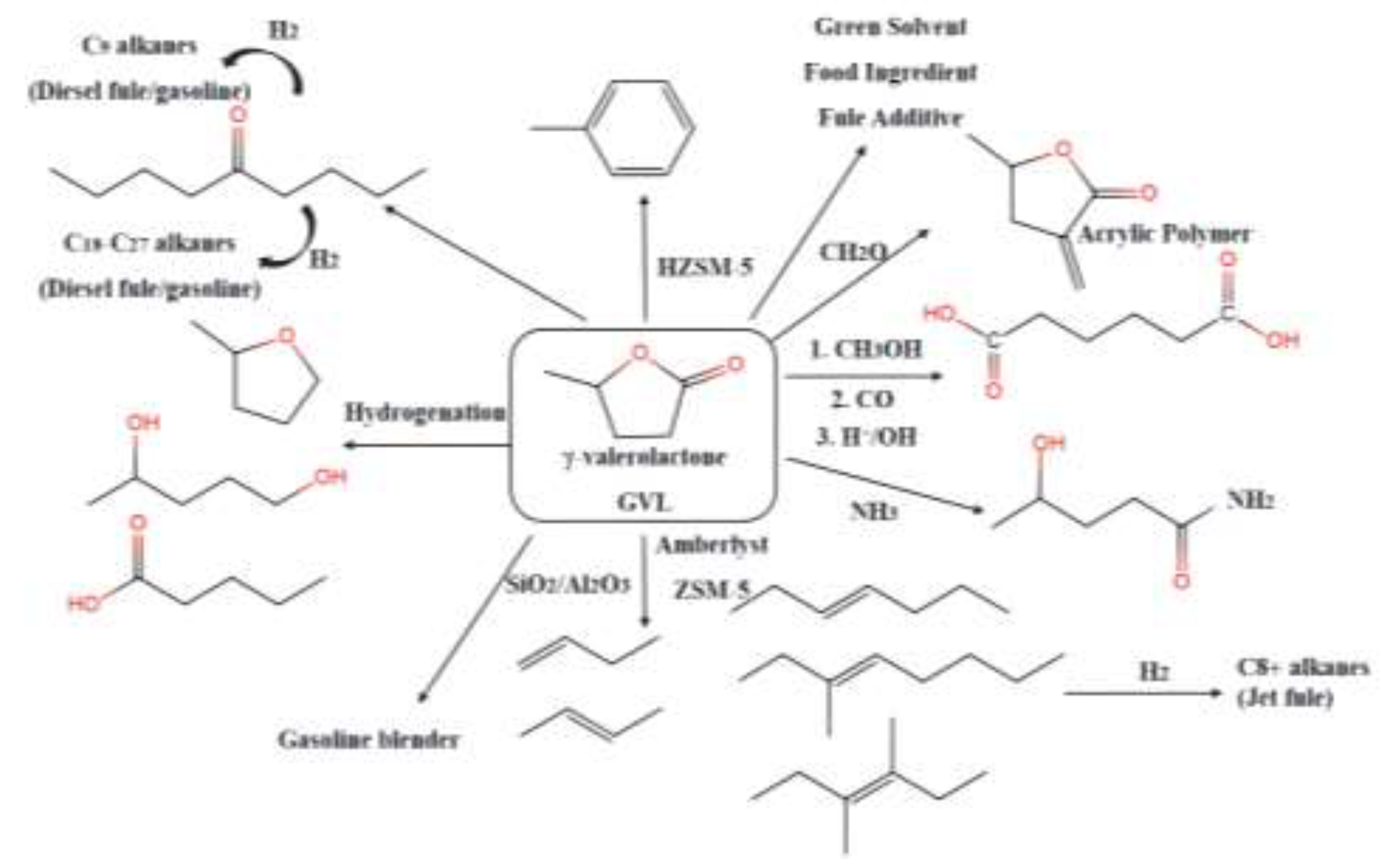

7]. γ-Valerolactone (GVL), prepared by hydrogenation of LA and its esters, is also a very important biomass platform molecule with the characteristics of non-toxic, biodegradable chemical that can be used as a solvent, fuel additive, and in the food industry, etc. [

8,

9,

10](

Scheme 1).

Ru-based heterogeneous catalysts are the most commonly used catalysts for the hydrogenation of LA to GVL. However, the Ru/C suffers from inactivation due to the formation of carbonaceous deposits, resulting in poor stability. In addition, carbon supports require multiple regeneration cycles to regenerate the catalyst, the presence of Ru nanoparticles on them is also thermodynamically unstable and tends to sinter into larger particles when exposed to high temperatures [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Ir catalyst also shows good catalytic performance in this hydrogenation reaction [

15,

16], but in most cases, Ir-based catalyst catalyzed LA hydrogenation still occurs at high temperature or high pressure. Compared with mono-metal catalysts, metal nano-alloy catalysts have better catalytic performance due to their special metal structure and synergistic effect between two or three different metals, which has been the focus of research in recent years [

14,

17,

18,

19]. Moreover, the researchers found that the activity and stability of the different metal nanoalloy catalysts were improved.

Selecting appropriate support is just as crucial in catalytic performance. For Ru-based catalysts supported by metal oxide supports (such as Al

2O

3, SiO

2, MCM-41, SBA-15, TiO

2, and CeO

2), the exposed hydroxyl groups (–OH) on the surface of oxide supports are prone to rehydrate with water in acidic aqueous phase, resulting in the collapse of the support structure, thus reducing the efficiency of the catalyst and even leading to catalyst deactivation [

20,

21,

22]. SiC is such a support with excellent acid-resistance, and it has shown improved performance for many reactions even in harsh reaction conditions [

23,

24,

25,

26].In our previous work, a highly dispersed Ir/SiC catalyst was prepared and showed excellent catalytic activity and stability for the aqueous hydrogenation of LA to GVL at 50 °C and 0.2 MPa of H

2 pressure [

15].

In this work, we prepared RuIr alloy catalysts supported by high specific surface area SiC for the aqueous hydrogenation of LA to GVL. The physicochemical properties of the as-synthesized catalysts and the influence of the thermal treatment of the catalyst were investigated. Then, the effects of support chemical composition and type of solvent were also studied. The results showed that SiC contributed to the increase of LA hydrogenation activity by the interaction with Ru and Ir metal, and the thermal treatment enhanced the stability of the catalysts.

Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

Prepared catalysts were thermally in the presence of Ru and Ir particles and form a more active heterogeneous interface.

Table 1 shows the physicochemical properties of the RuIr/SiC catalysts treated at different calcination times. SiC has a higher specific surface area (

Table 1, entry 1), but a decreased specific surface area after loading RuIr. Compared with the Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 catalyst directly reduced without calcination, the specific surface area of the calcinated catalyst is further reduced, and Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-12 shows the lowest specific surface area and pore volume (

Table 1, entry 6), which may be due to the serious aggregation of RuIr species with the extension of calcination time, leading to the surface covering and pore plugging of the support.

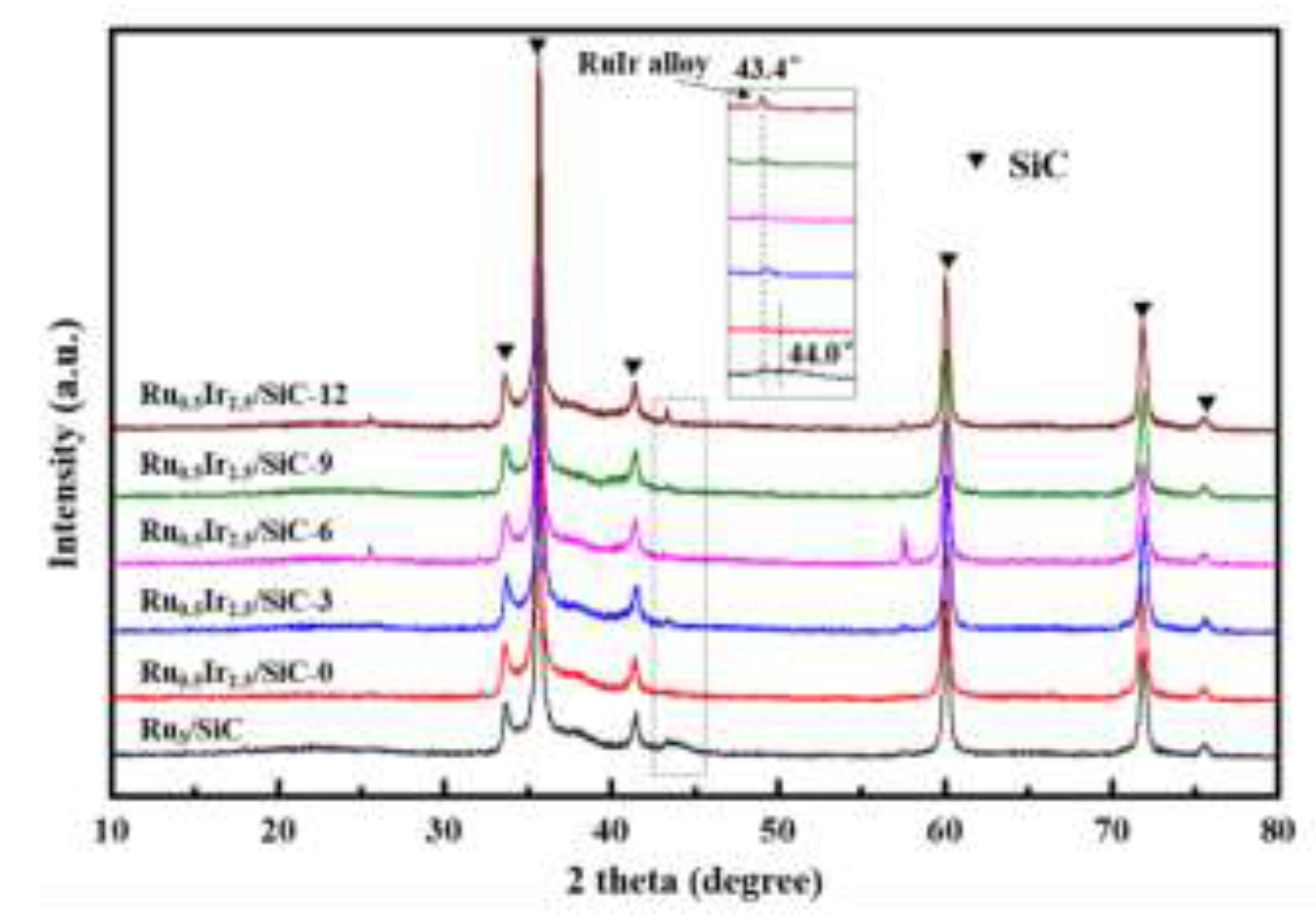

XRD pattern of synthesized RuIr/SiC catalysts treated with different calcination times is shown in

Figure 1. From the diffraction pattern, all the strong diffraction peaks at 35.7

o, 41.4

o, 60.1

o, 71.8

o and 75.6

o 2θ correspond to the characteristic diffraction peaks of β-SiC, namely: (101), (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222), respectively [

28]. For the Ru

3/SiC catalyst, the weak diffraction peak at 2θ = 44.0 is attributed to the characteristic peak of metallic Ru, corresponding to the Ru (101) crystal plane. The diffraction peaks of Ru and Ir are not observed for Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 catalyst, which may be due to the fact that Ru and Ir are not formed alloys and independently distributed on the SiC surface, while the loading of Ru is low and Ir particles are very small. For the RuIr/SiC catalyst reduced after calcination, there is a diffraction peak at 43.4

o, indicating the formation of RuIr alloy.

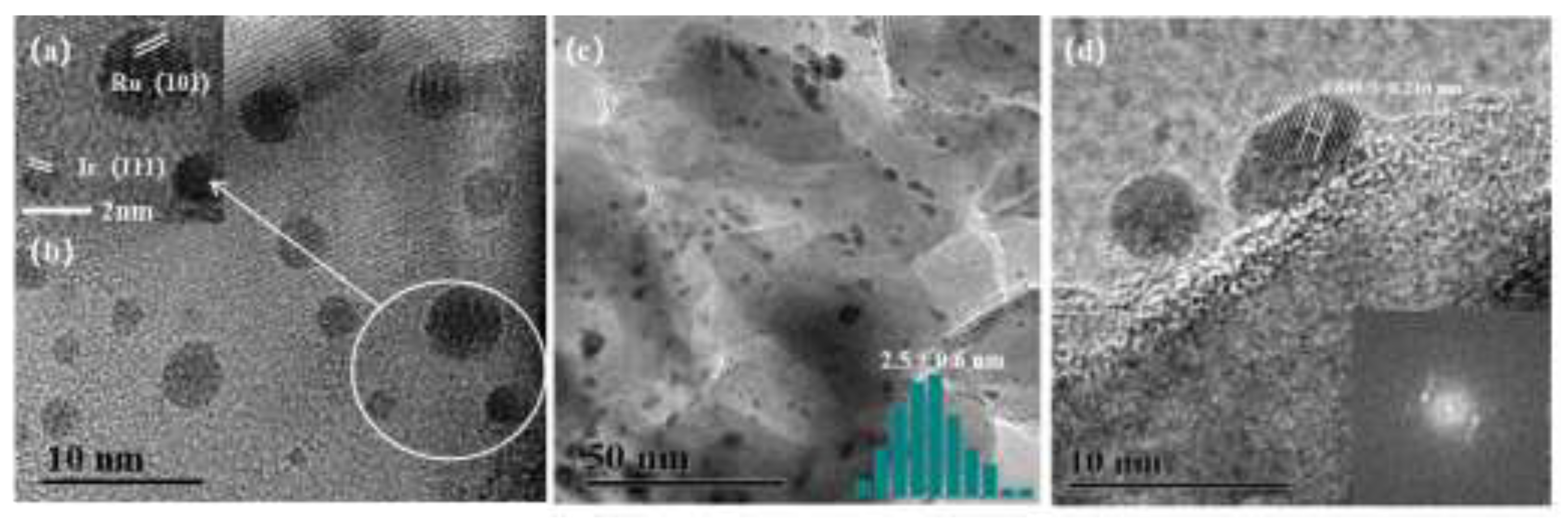

Figure 2 shows representative TEM images of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 and Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 catalysts. From the TEM images of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 (

Figure 2a and

2b), Ru and Ir nanoparticles are independently distributed on the SiC surface with an average diameter of about 2.4 nm and 1.5 nm, respectively (

Figure S1). The lattice spacings of Ir and Ru nanoparticles in Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 catalyst are 0.216 nm and 0.205 nm, respectively, corresponding to Ir (111) and Ru (101) crystal planes [

29]. For Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6, the bimetallic RuIr nanoparticles were uniformly dispersed on the SiC surface with an average diameter of about 2.5 nm (

Figure 2c). The high-resolution TEM image of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 shows that the lattice spacing of RuIr alloy nanoparticles are about 0.216 nm, corresponding to Ir (111) crystal planes (Fig. 3d), which may be due to the segregation behavior of metal Ir on the surface of alloy particles [

30]. The combined XRD results confirm that Ru and Ir exist as alloys.

H

2-temperature-programmed reduction (H

2-TPR) was carried out to study the oxidation-reduction properties of the catalysts and the strength of the interaction between Ru, Ir and SiC. From the H

2-TPR results (

Figure 3), the reduction peak of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 catalyst at 124 °C is attributed to the reduction of RuO

x, amorphous RuO

2 or Ru(OH)

x. The peak in the range of 300-400 °C is probably due to the reduction of Ru(OH)

3 species or the reduction of RuO

2 [

31]. After the formation of RuIr alloy on the catalyst, the reduction temperature of the catalysts in the low-temperature range increases from 124 °C to 196 °C, indicating that the interaction between metal and SiC is enhanced after RuIr formation, which is beneficial to the dispersion and stabilization of RuIr alloy nanoparticles.

2.2. Catalytic Performance Studies

The catalytic performances of different catalysts for the hydrogenation of LA into GVL were investigated. The results are summarized in

Table 2. From the Table, Monometallic Ir

3/SiC and Ru

3/SiC catalysts have lower activity for the reaction. At 25 °C, the LA conversions are 61.8% and 55.9 %, respectively for Ir

3/SiC and Ru

3/SiC (

Table 2, entries 1 and 2). When replacing a small amount of Ir by the Ru, the bimetallic Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC catalyst shows enhanced catalytic activity (

Table 2, entry 3). The superior hydrogenation activity originates from the synergistic effect among Ru, Ir and SiC, which changes the electronic structure of the SiC surface [

29]. The Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC catalysts treated with different calcination times at 300 °C show different catalytic activities. After the calcination of 3 h, the LA conversions is 90.5% (

Table 2, entry 4). When the calcination time is extended to 6 h, the LA conversions reaches 99.8% (

Table 2, entry 5). With the longer calcination time, the conversion rate of LA decreases (87.2% and 61.5% for 9 h and 12 h, respectively) (

Table 2, entries 6 and 7). The decrease of catalyst activity may be due to the agglomeration of metal nanoparticles caused by long cacination time.

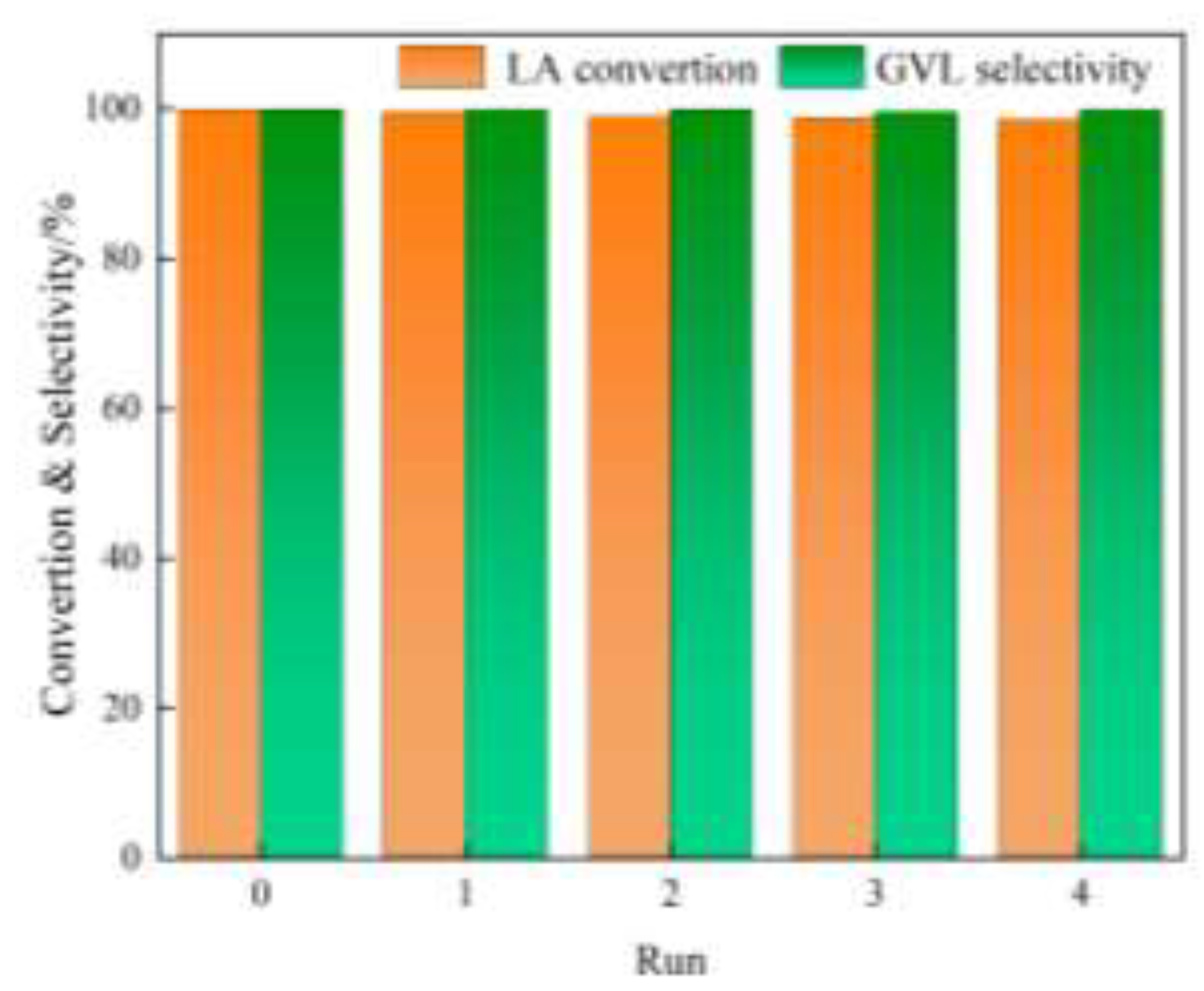

The stability of catalyst is an important performance in the evaluation of heterogeneous catalysts. Since LA is an acidic substance, it is easy to corrode the catalyst and cause the loss of active components during the reaction process, resulting in the deactivation of the catalyst. Therefore, improving the stability of catalyst has always been a focus of research for this reaction. The stability of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC catalysts in LA hydrogenation was further studied. Although Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-0 has the best catalytic activity, the stability of the catalyst is relatively poor. After 5 cycles, the activity of the catalyst was decreased from 99.9% to 87.0% (

Figure S2). This is mainly caused by the agglomeration of the active metal on the support surface, which can also be seen from the TEM image (

Figure S3) of the catalyst after 5 reactions. Under the same reaction conditions, the Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 catalyst showed high catalytic stability and nearly no loss of activity after 5 consecutive catalytic operation cycles (

Figure 4). The catalyst after 5 cycles of reaction was characterized by TEM (

Figure S4) , we can see that there is no obvious change in the morphology such as particle agglomeration. Overall, the stability of RuIr/SiC alloy catalyst is reliable in biomass LA hydrogenation. Therefore, the Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 catalyst was selected for the work.

2.3. RuIr/SiC alloy Nanoparticles for Catalysis

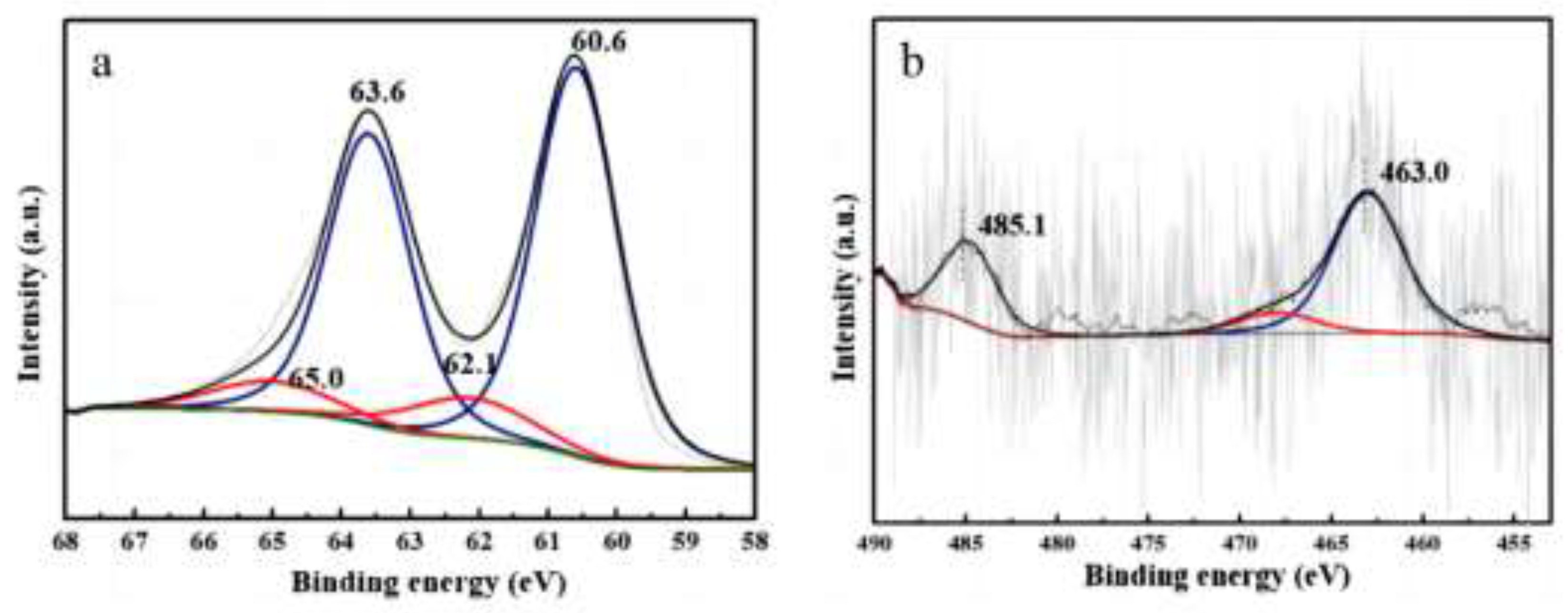

XPS was carried out to study the electronic properties of Ir and Ru in the bimetallic Ru

0.5Ir2.5/

SiC-6 catalyst. From the XPS results shown in

Figure 5a, the binding energy (BE) at 60.6 eV and 63.6 eV are attributed to Ir(0) 4f

7/2 and Ir(0) 4f

5/2 electronic states, respectively, which are lower than the standard values of metallic Ir (60.9 eV for Ir 4f

7/2 and 63.9 eV for Ir 4f

5/2), indicating that Ir particles are enriched with electrons. The BE values at 62.1 eV and 65.0 eV are correspond to the 4f

7/2 and 4f

5/2 peaks of Ir

n+, indicating that a small amount of Ir in the catalyst is partially oxidized. Furthermore, the peaks of Ir

0 and Ir

n+ of Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 shift towards lower BE values compared to the BE of Ir on Ir

3/SiC (

Figure S5a). From

Figure 5b, the BE values at 463.0 eV and 485.1 eV are attributed to Ru

0 3p

3/2 and Ru

0 3p

1/2 electronic states, respectively, and the BE values of Ru shift to the higher BE values compared o Ru

3/SiC (

Figure S5b). In the previous work, we have confirmed that some electrons in the conduction band of SiC transfer to Ir due to the Mott-Schottky effect in Ir

3/SiC [

15]. In Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6, the electron enrichment on Ir is further enhanced because of the electrons on Ru in RuIr alloy also are transferred to Ir. Thus, the catalytic activity of Ir increases greatly.

H

2-temperature-programmed desorption (H

2-TPD) was used to get an insight into the strengths of hydrogen-surface interactions and number of active sites for H

2 adsorptionon the catalyst. From the H

2-TPD spectra (

Figure 6), for Ir

3/SiC, a wide H

2 desorption peak in the 320-590 °C range with a maximum at 539 °C is attributed to desorption of hydrogen from Ir particles. And then a huge H

2 desorption starts from 600 °C and continues to above 800 °C, which may be due to H

2 directly desorbs from the SiC surface. These results indicate that there exist at least two sites on the SiC surface for H

2 chemisorption: weak and strong chemisorption sites. For Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6, the H

2 desorption temperatures from both sites decreases to 529 °C and 580 °C, respectively. The decrease in desorption temperatures means that the adsorbed hydrogen species have weaker interactions with SiC surface, and this will benefit to the hydrogenation processes that occur on the SiC surface. From the TPD results, RuIr alloy nanoparticles obviously increases the active sites for H

2 chemisorption but weakens the interactions between adsorbed hydrogen and SiC surface. There are many studies have shown that hydrogen atoms can be chemisorbed on the SiC surface, and that the migration of hydrogen atoms on SiC has a very low energy barrier [

26,

32]. In this work, H

2 can be dissociated on Ir surface and then spillover to the SiC surface. These spillover hydrogen species have a lower migration barrier on the SiC surface, and thus have high activity in chemical reactions.

Support is an important factor affecting the activity and stability of the catalyst, and the interaction between metal and support can improve the performance of the catalyst. The catalytic performance of RuIr alloy catalysts with different support composition for the hydrogenation of LA was investigated and results are shown in

Figure S6. Ru

0.5Ir

2.5/SiC-6 catalyst shows the highest catalytic activity for the hydrogenation of LA at 25

oC in water under 0.2 MPa H

2 pressure for 2 h (4 mmol LA). When the reaction temperature rises to 50

oC (10 mmol LA), SiC shows better acid resistance in this reaction.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Preparation Methods

Iridium chloride hydrate (IrCl3·3H2O), Ruthenium(III) chloride hydrate (RuCl3·3H2O), LA, ethanol, TiO2, ZrO2, SiO2 and Al2O3 were purchased from Aladdin. Graphene and active carbon were obtained from TM (Shanxi, Taiyuan). Deionized water was made in the lab. High purity nitrogen gas, argon gas and hydrogen gas (99%) was obtained from TISCO (Shanxi, Taiyuan). All reagents and chemicals were used as received without any further purification.

A simply and easily adaptable co-impregnation method has been used to synthesize bimetal RuIr/SiC alloy catalysts. Cubic SiC powders with a specific surface area of 46 m

2 g

-1 were prepared by a sol-gel and carbothermal reduction process [

27]. In a typical synthesis, the SiC support was added to the ethanol solution (10 mL) containing the requisite amount of IrCl

3 solution (2 mg/mL) and RuCl

3 solution (10 mg/mL) and stirred well for 4 h at room temperature. The mixture was heated to 80 °C until the solvent was completely evaporated. The obtained solid was dried in an oven at 100 °C for 12 h and subsequently calcined at 300 °C with a rate of 10 °C/ min for 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, and 12 h, respectively. Subsequently, these calcined samples were reduced by 5% H

2/Ar mixture at 300

oC with a rate of 5 °C/ min for 2 h and were labeled as RuIr/SiC-3, RuIr/SiC-6, RuIr/SiC-9, RuIr/SiC-12. The catalyst directly reduced without calcination was recorded as RuIr/SiC-0.

RuIr/graphene, RuIr/TiO2, RuIr/ZrO2, RuIr/SiO2 and RuIr/Al2O3 catalysts were also obtained by the similar mothed.

3.2. Catalysts Characterization

The micromorphology and structure of the catalyst were characterized using a JEM-2100F high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The main phase and crystal structure of the catalysts were performed by X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku D-max/RB-2500) using CuKα radiation (λ=1.5406 Å) with a scanning speed of 4°/min. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was obtained with an ESCALAB 3MKII de VG spectrometer with a Mg Kα as X-ray source, and the peaks were calibrated with the characteristic C 1s peak at 284.8 eV. N2 isotherms adsorption-desorption and pore size distribution curves of the material (77 K) were measured on a TriStar II 3020 instrument. The BET specific surface area (m2/g) was estimated based on the N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms. Moreover, pore size and pore size distributions were calculated using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method.

Hydrogen temperature-programed reduction (H2-TPR) and Hydrogen temperature-programed desorption (H2-TPD) experiments of the catalysts were performed on a chemical adsorption instrument (Tianjin TP-5080). The granularity of the catalyst is 20-40 orders. For H2-TPR, the 50 mg sample was loaded into a quartz tube, and 10 vol% H2/N2 mixture was introduced as reducing gas. First, the sample was purged at 30 °C until the baseline was stable, and then heated at a heating rate of 10 °C/min for reduction. For H2-TPD, 100 mg of catalyst sample was pretreated in N2 flow (25 mL/min) at 300 °C for 2 h, and then cooled to room temperature. After the pretreatment, H2 was introduced to the sample in the form of pulse injection for 10−20 min until adsorption saturation. The system was purged with N2 (25 mL/min) until the signal reduced to constant. The temperature was then increased linearly from 30 to 800 °C with a rate of 10 °C/ min. The signal was detected by TCD detector。

3.3. Catalytic Reaction

The catalytic reaction of LA hydrogenation to GVL was conducted in a 50 mL stainless-steel autoclave with a pressure gauge and automatic temperature control. A typical reaction process is described as follows: 4 mmol of LA, 50 mg of catalyst and 10 ml of solvent were dispersed in the autoclave. The reactor was purged three times by hydrogen to eject air, then filled with 0.2 MPa H2 and reacted for 2 h at room temperature (25 oC). After the reaction, the reaction mixture was filtered through a organic filtration membrane, and the resulting filtrate was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS, BRUKER SCION SQ 456, Germany).

4. Conclusions

To summarize, we prepared SiC-supported RuIr alloy nanocatalyst and characterized by TEM and XPS analysis. RuIr alloy nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed on the SiC surface. The XPS characterization results indicate that there is an inter-electron interaction among Ru, Ir and SiC, which is also the main reason for the high activity of the catalyst for hydrogenation of LA under mild conditions. Also, the catalyst was recycled from the reaction medium and reused for five consecutive runs without any significant decrease in the catalytic activity and product yield. Comparing the RuIr catalysts loaded by other supports, SiC support shows better acid resistance in this reaction. Thus, we believe the present report will be a valuable addition to the biomass conversion in industrial production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The size distributions of (a) Ru and (b) Ir nanoparticles in the Ru0.5-Ir2.5/SiC-0 catalyst; Figure S2: Recyclability in the hydrogenation of LA over Ru0.5Ir2.5/SiC-0 catalyst; Figure S3: The TEM image of used Ru0.5Ir2.5/SiC-0 catalyst after five cycles; Figure S4: The TEM image of the Ru0.5Ir2.5/SiC-6 catalyst after five cycles; Figure S5: XPS of Ir3/SiC (a) and Ru3/SiC (b); Figure S6: Catalytic performances of RuIr catalysts with different support for LA hydrogenation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Yingyong Wang and Xiangyun Guo; formal analysis, Jingru Wang, Yingyong Wang and Xiangyun Guo; investigation, Jingru Wang; resources, Xianshu Dong and Yuping Fan; data curation, Xianshu Dong and Yuping Fan; writing—review and editing, Jingru Wang; funding acquisition, Xiangyun Guo and Jingru Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21673271, 21603259), the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021222111), the Scientific and Technological Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (No. 2022L058), the 2022 Annual University Fund of Taiyuan University of Technology (No. 2022QN068).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to all those who helped me during the writing of this paper. A special acknowledgement should be shown to Prof. Guo Xiangyun and Prof. Wang Yingyong, for their invaluable instruction and inspiration. I am thankful to SXICC and Taiyuan University of Technology for infrastructure and sample characterization facilities. I am also extremely grateful to my husband Mr. Song and my lovely son Song Shaohui for their support and encouragement in my life.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Armaroli, N.; Balzani, V. , The Future of Energy Supply: Challenges and Opportunities. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2006, 46, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuhe Liao, S.-F. K. , Gil Van den Bossche, Joost Van Aelst, Sander Van den Bosch, Tom Renders, Kranti Navare, Thomas Nicolaï, Korneel Van Aelst, Maarten Maesen, Hironori Matsushima, Johan M. Thevelein, Karel Van Acker, Bert Lagrain, Danny Verboekend, Bert F. Sels, A Sustainable Wood Biorefinery for Low–Carbon Footprint Chemicals Production. Science 2020, 367, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Shafiei, N.; Nezafat, Z.; Bidgoli, N. S. S. , Recent Progresses in the Application of Lignin Derived (Nano)Catalysts in Oxidation Reactions. Molecular Catalysis 2020, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zou, W.; Yue, H.; Tian, G.; Feng, S. , Transfer Hydrogenation of Methyl Levulinate into Gamma-Valerolactone, 1,4-Pentanediol, and 1-Pentanol over Cu–ZrO2 Catalyst under Solvothermal Conditions. Catalysis Communications 2016, 76, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, A.; Apte, M.; Pandey, R. A. , Levulinic Acid Production from Renewable Waste Resources: Bottlenecks, Potential Remedies, Advancements and Applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Jarvis, C.; Gu, J.; Yan, Y. , Production and Catalytic Transformation of Levulinic Acid: A Platform for Speciality Chemicals and Fuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakova, I. L.; Demidova, Y. S.; Simonov, M. N.; Niphadkar, P. S.; Bokade, V. V.; Devi, N.; Dhepe, P. L.; Murzin, D. Y. , Mesoporous Carbon and Microporous Zeolite Supported Ru Catalysts for Selective Levulinic Acid Hydrogenation into Γ-Valerolactone. Catalysis for Sustainable Energy 2019, 6, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Gu, C.; Feng, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, L. , Selective Production of 2-Butanol from Hydrogenolysis of Levulinic Acid Catalyzed by the Non-Precious Nimn Bimetallic Catalyst. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9, 15603–15611. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.; Yu, I. K. M.; Tsang, D. C. W.; Ng, Y. H.; Ok, Y. S.; Sherwood, J.; Clark, J. H. , Green Synthesis of Gamma-Valerolactone (Gvl) through Hydrogenation of Biomass-Derived Levulinic Acid Using Non-Noble Metal Catalysts: A Critical Review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 372, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W. , Hydrodeoxygenation of Levulinic Acid over Ru-Based Catalyst: Importance of Acidic Promoter. Catalysis Communications 2023, 184, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maumela, M.; Marx, S.; Meijboom, R. , Heterogeneous Ru Catalysts as the Emerging Potential Superior Catalysts in the Selective Hydrogenation of Bio-Derived Levulinic Acid to Γ-Valerolactone: Effect of Particle Size, Solvent, and Support on Activity, Stability, and Selectivity. Catalysts 2021, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gu, L.; Shao, S.; Li, W.; Zeng, D.; Yang, F.; Hao, S. , Stable Yolk-Structured Catalysts Towards Aqueous Levulinic Acid Hydrogenation within a Single Ru Nanoparticle Anchored inside the Mesoporous Shell of Hollow Carbon Spheres. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 576, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Sun, W.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Wei, H.; Ma, L. , Pore-Scale Investigation on Multiphase Reactive Transport for the Conversion of Levulinic Acid to Γ-Valerolactone with Ru/C Catalyst. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 427, 130917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Bernal, Z.; Ángeles Lillo-Ródenas, M.; Carmen Román-Martínez, M. , Effect of the Carbon Surface Chemistry on the Metal Speciation in Ru/C Catalysts. Impact on the Transformation of Levulinic Acid to Γ-Valerolactone. Applied Surface Science 2025, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Tong, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Guo, X. , Highly Active Ir/Sic Catalyst for Aqueous Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid to Γ-Valerolactone. Catalysis Communications 2020, 139, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fan, K. , Catalytic Conversion of Biomass-Derived Levulinic Acid into Γ-Valerolactone Using Iridium Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nanotubes. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2013, 34, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Liu, X.; Uguna, C. N.; Sun, C. , Selective Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid to Γ-Valerolactone over Copper Based Bimetallic Catalysts Derived from Metal-Organic Frameworks. Materials Today Sustainability 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, F. , Facile Fabrication of Composition-Tuned Ru–Ni Bimetallics in Ordered Mesoporous Carbon for Levulinic Acid Hydrogenation. ACS Catalysis 2014, 4, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. S. R.; Kantam, M. L. , Selective Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid into Γ-Valerolactone over Cu/Ni Hydrotalcite-Derived Catalyst. Catalysis Today 2018, 309, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawi, M. S. a. S. , An Optimal Direct Synthesis of Crsba-15 Mesoporous Materials with Enhanced Hydrothermal Stability. Chemistry Of Materials 2007, 19, 509–519. [Google Scholar]

- El Doukkali, M.; Iriondo, A.; Cambra, J. F.; Jalowiecki-Duhamel, L.; Mamede, A. S.; Dumeignil, F.; Arias, P. L. , Pt Monometallic and Bimetallic Catalysts Prepared by Acid Sol–Gel Method for Liquid Phase Reforming of Bioglycerol. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2013, 368-369, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, O. A.; Luo, H. Y.; Heyden, A.; Román-Leshkov, Y.; Bond, J. Q. , Toward Rational Design of Stable, Supported Metal Catalysts for Aqueous-Phase Processing: Insights from the Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid. Journal of Catalysis 2015, 329, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiao, Z.-F.; Zhao, J.-X.; Yao, D.; Li, X.; Guo, X.-Y. , Boosting the Selectivity of Pt Catalysts for Cinnamaldehyde Hydrogenation to Cinnamylalcohol by Surface Oxidation of Sic Support. Journal of Catalysis 2023, 425, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, Q.; Bai, X.; Song, Y. , Research Progress on Application in Energy Conversion of Silicon Carbide-Based Catalyst Carriers. Catalysts 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadhem, A. M.; Tavares, F.; Realpe, N.; Lezcano, G.; Yudhanto, A.; Subah, M.; Manaças, V.; Osinski, J.; Lubineau, G.; Castaño, P. , A Holistic Approach to Include Sic and Design the Optimal Extrudate Catalyst for Hydrogen Production–Reforming Routes. Fuel 2023, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.-H.; Guo, X.-N.; Sankar, M.; Yang, H.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Tong, X.-L.; Jin, G.-Q.; Guo, X.-Y. , Synergistic Effect of Segregated Pd and Au Nanoparticles on Semiconducting Sic for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 23029–23036. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.-Q.; Guo, X.-Y. , Synthesis and Characterization of Mesoporous Silicon Carbide. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2003, 60, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.-H.; Guo, X.-N.; Pan, Y.-T.; Chen, S.; Jiao, Z.-F.; Yang, H.; Guo, X.-Y. , Visible-Light-Driven Selective Photocatalytic Hydrogenation of Cinnamaldehyde over Au/Sic Catalysts. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 9361–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Tong, X.; Guo, X. , Enhanced Activity of Ru-Ir Nanoparticles over Sic for Hydrogenation of Levulinic Acid at Room-Temperature. Materials Research Bulletin 2021, 135, 111128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagot, P. A. J.; Cerezo, A.; Smith, G. D. W. , 3d Atom Probe Study of Gaseous Adsorption on Alloy Catalyst Surfaces Iii: Ternary Alloys – No on Pt–Rh–Ru and Pt–Rh–Ir. Surface Science 2008, 602, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, L. A.; Collins, S. E.; Han, C. W.; Ortalan, V.; Zanella, R. , Synergetic Effect of Bimetallic Au-Ru/Tio2 Catalysts for Complete Oxidation of Methanol. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 207, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann, J.; Peng, X.; Wieferink, J.; Krüger, P. , Adsorption of Hydrogen and Hydrocarbon Molecules on Sic(001). Surface Science Reports 2014, 69, 55–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).