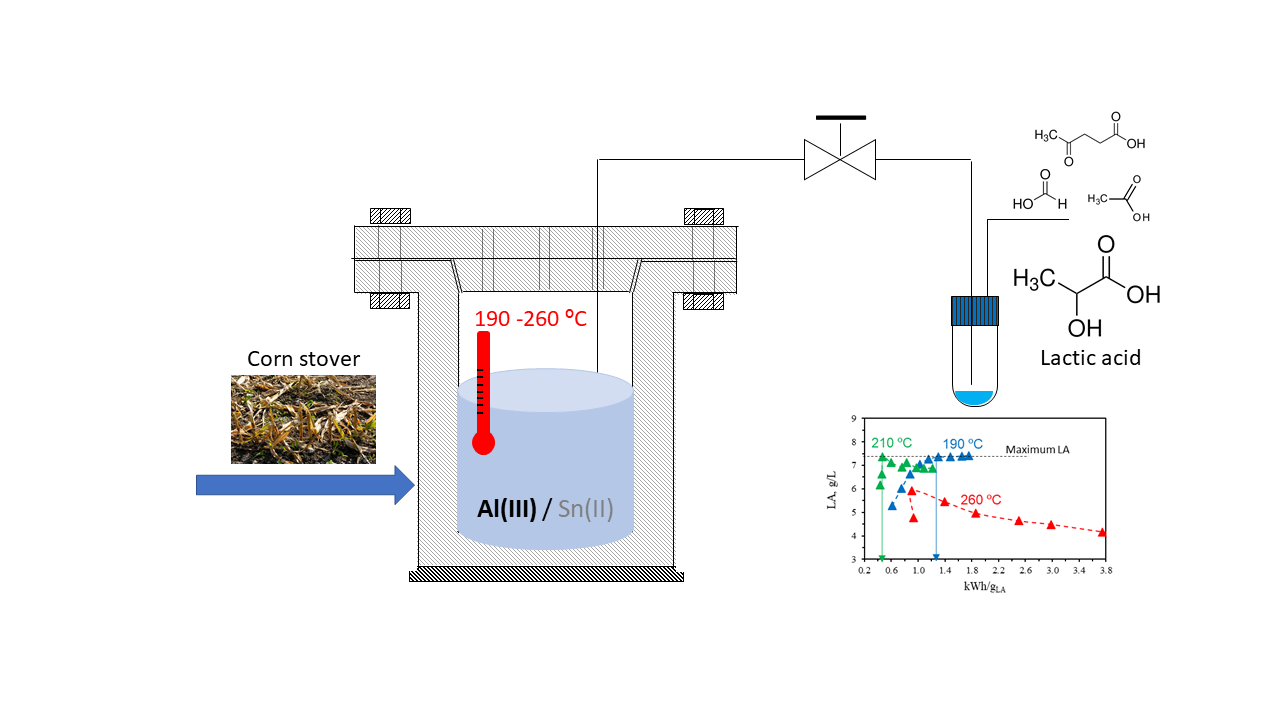

2.1. Effect of Molar Concentration of an Equimolar Al(III)/Sn(II) Mixture

The effect of molar concentration of catalyst was tested in the range from 5 mM to 32 mM for a equimolar mixture of AlCl

3/SnCl

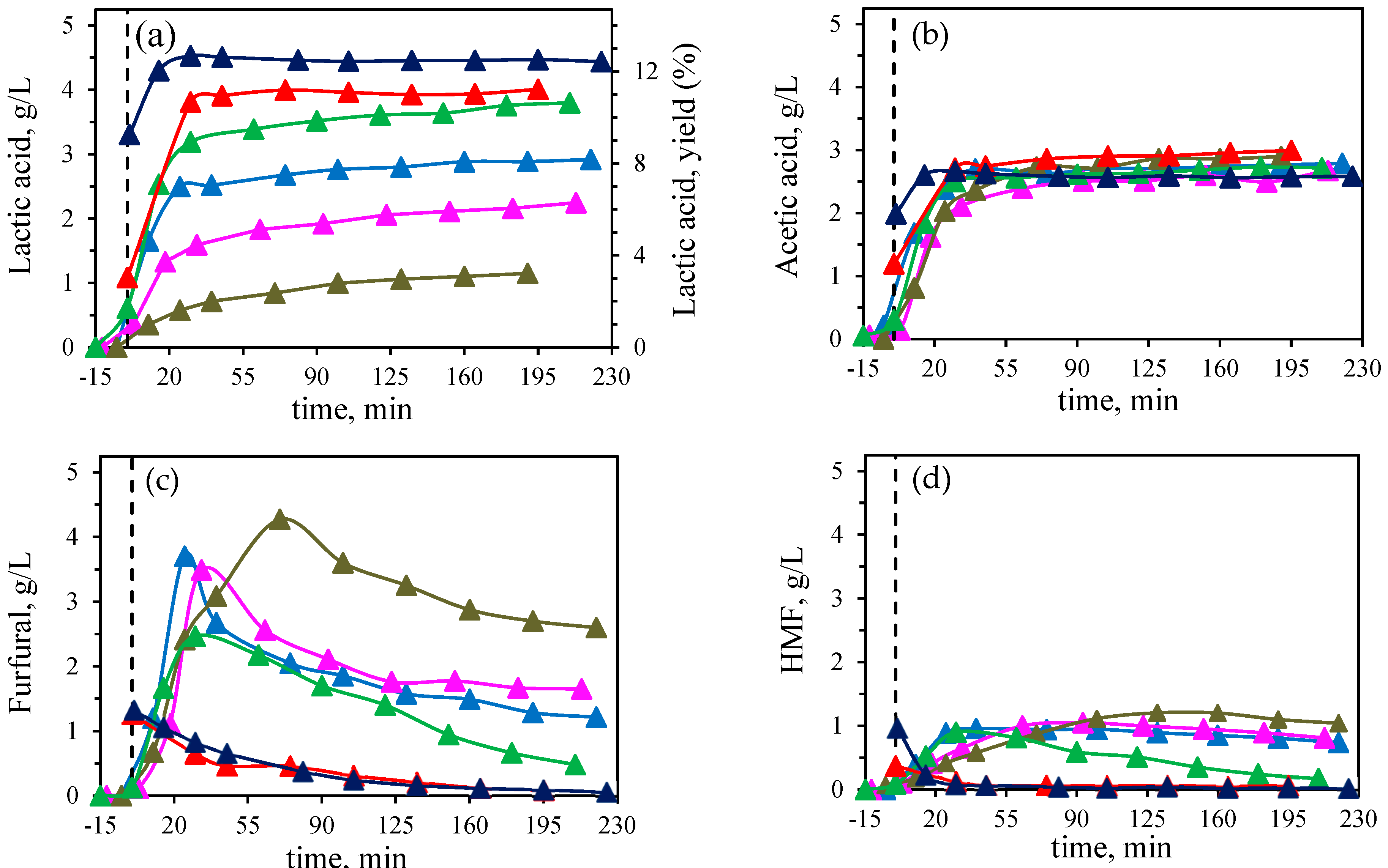

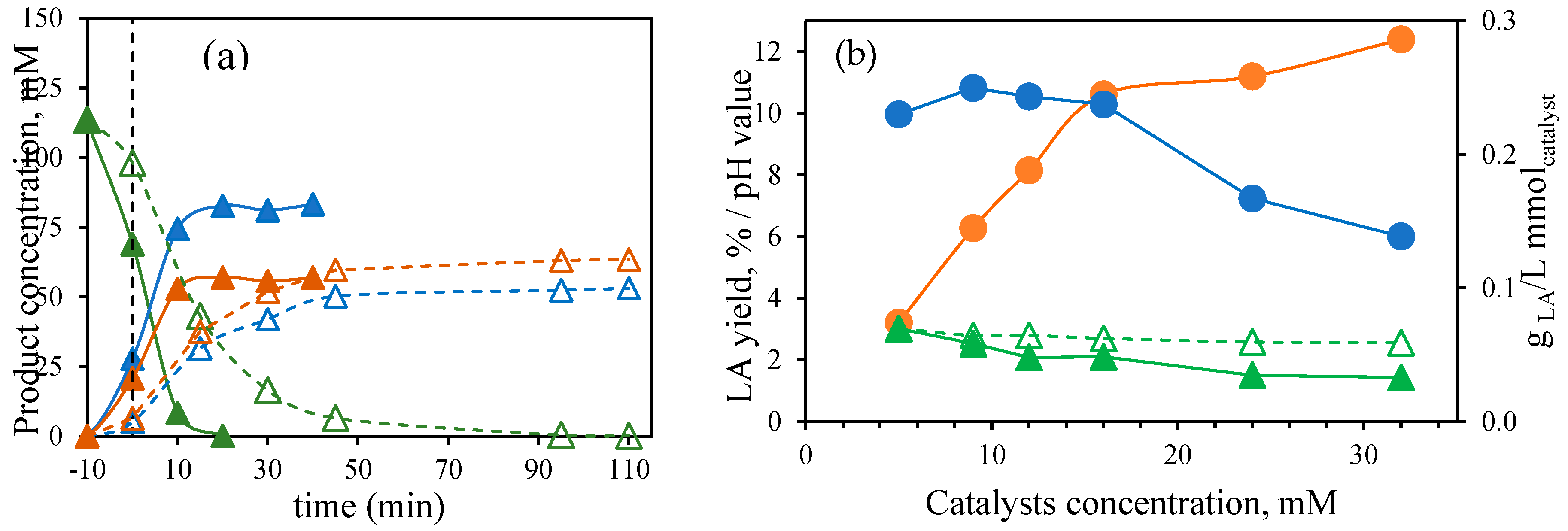

2 at 190 ºC using corn stover at 5 wt.%. Different products distribution was obtained by changing the catalyst molar concentration (

Figure 1). By increasing the molar concentration of the mixture of catalyst, an increase in the LA concentration and yield was observed. This increase was remarkable in the low concentration range of the catalyst molar concentration explored in this work with values of 1.20 and 2.2 gLA/L at 5 and 9 mM, respectively; while values among 2.9-4.5 gLA/L were obtained at concentrations of the calalystyts higher than 12 mM and up to 32 mM, which correspond to yields in the range of 8.2 to 12.3 %.

In the hydrothermal transformation of the polysaccharide fraction of the biomass, a complex network has been described including dehydration, isomerization, and retro-aldol condensations.

When performing the reaction at 190 ºC in the absence of an external catalyst (

Figure 2), 49.4 % of the initial corn stover was solubilized, mainly the hemicellulose fraction and some of the glucan fraction. This can be clearly observed in the product distribution, since the acetyl groups from the hemicellulose are released yielding high concentration of acetic acid in the reaction medium, up to 2.5 g/L after 140 min of isothermal treatment time. On the other hand, the dehydration of the pentoses produces furfural in an increasing concentration with time, up to 2.4 g/L. HMF, as dehydration product from hexoses, was also found in the reaction medium but in a much lower concentation, since the solid residue still contains a 62% of glucans. Therefore, in the absence of catalyst, the dehydration route is the predominant route. Glyceraldehyde (triose) as precursor in the retroaldol route was the predominant triose and lower amounts of glycoaldehyde (diose) were also identified, being these compounds intermediates in LA production through the dehydration, producing 0.37 gLA/L after treatment, much lower than the final concentration when using a high enough catalyst concentration.

Rasrendra et al. [

16] also indicated that when reacting glyceraldehyde or dihydroxyacetone in the absence of salt catalysts or with Bronsted acids like HCl, lactic acid was not detected and the formation of the isomerisation products (dihydroxyacetone or glyceraldehyde), the dehydration product (pyruvaldehyde) and brown insoluble products were observed instead.

It can be concluded that the presence of inorganic salts acting a Lewis acidic metal centers is crucial in the production of lactic acid. To check the neat effect of subW as reaction medium, a study was conducted using glucose as the initial sugar monomer and an equimolar mixture of Al(III)/Sn(II) at 90 °C. After 4 h no glucose breakdown was observed, keeping its concentration constant. This suggests a positive effect between subW and the Lewis acid catalyst also to produce lactic acid from sugar.

When using the equimolar mixture Al(III)/Sn(II), the production of furfural is promoted at low concentration (

Figure 1c) reaching a maximum at 5 mM of 4.3 g/L. Lower concentrations of furfural were observed when increasing catalyst concentration, probably due to degradation to humins and other products such as formic acid [

19] and the promotion of the retro aldol route to produce LA. In fact, different chloride metals have been proved as optimum catalysts in the formation of furfural from lignocellulosic biomass with furfural yields slightly higher than 50 % from a xylose solution of 73 mM at 180 °C when using metal salt chloride in the range from 0.83 mM and 0.91 mM of CrCl

3 and AlCl

3, respectively [

17]. Similar behaviour was observed for HMF, but the highest concentration of HMF was lower than for furfural with values of 1.2 g/L and with concentrations lower than 0.1 g/L for concentrations of catalyst higher than 16 mM. By increasing metal concentration, the concentration of the glyceraldehyde and glycoaldehyde decreased dramatically, limiting the LA production (profile not shown).

Therefore, high concentrations of Lewis acid promote the degradation of dehydration products and LA formation. In this regard, it is well know that water can rehydrate HMF to form levulinic and formic acids [

18]. At low molar catalyst concentrations (5-9 mM) the levulinic acid concentration was low, from 0 to 0.3 g/L. Higher concentration of formic acid was obtained but it probably comes from the degradation of other components present in the reaction medium such as furfural or sugar monomers, such as xylose, as it has been described in the literature [

19]. By increasing the catalyst molar concentration, the levulinic acid formation increased, similar to formic acid. To support that the mixture of Lewis acids catalyse the conversion of HMF into levulinic and formic acid, two separate experiments (initial concentration of 114 mM of HMF) were carried out at 190 °C using two different molar concentration of the catalysts equimolar mixture, 24 mM and 5 mM, to check its effect on the degradation of HMF (

Figure 3a).

It can be clearly observed that an increase in the catalyst concentration led to a faster increase in the levulinic and formic acids formation. At 5 mM slightly higher formic acid concentration was obtained (63.2 mM, 9.3 % yield) than for levulinic acid (52.4 mM, 39 % yield). However, at 24 mM, after 20 min of isothermal time, HMF was completely degraded and the corresponding final concentrations of levulinic and formic acids were 83 mM (61.6 % yield) and 57 mM (8.4 % yield), respectively, highlighting that not equimolar concentrations were obtained. Rasrendra et al. [

16] also reported that when an aqueous solution of HMF (0.1 M) and AlCl

3 (5 mM) were heated to 180 °C for 1 h, 90% HMF conversion was observed and levulinic acid was obtained in 50 mol% yield. These authors also observed that in the conversion of D-glucose using AlCl

3 (C

glucose = 0.1 mol/L, C

salt = 5 mM) at 140 °C, levulinic and formic acids were not formed in 1:1 molar ratio being the amount of formic acid slightly higher than that of levulinic acid, similar to the results presented in

Figure 3a. These authors did not propose a sound explanation for this observation, suggesting that additional formic acid is formed by yet unknown pathways. In the present work, when treating corn stover at 190 °C at diferent molar concentrations of the equimolar mixture of Al(III):Sn(II), higher molar concentration of formic acid was obtained than for levulinic acid. For instance, at 24 mM formic acid, molar concentration was 69.5 mM (3.2 g/L), while levulinic acid concentration was 43.1 mM (5 g/L). As previously published by Illera et al. [

19] formic acid could be formed as degradation product of furfural and also from xylose. According to Lange et al. [

20] protonation at C3-OH of xylose would result in decomposition to formic acid and a C4 fragment, which degrades very rapidly and it is not observed experimentally according to these authors.

Figure 3b plots the final LA yield achieved using the different catalysts molar concentrations and the LA productivity per mmol of catalyst used after the treatment of corn stover at 190 °C. As previously described, LA yield significantly increases when the catalyst concentration ranges from 5 to 16 mM. Beyond 16 mM, the increase in LA yield becomes less significant. When plotting productivity in terms of LA produced per mmol of catalyst, a relatively consistent productivity is noted up to 16 mM. At higher concentrations, productivity declines. Therefore, 16 mM was considered the optimum catalyst concentration to mantain high selectivity for LA while also high LA productivity.

Figure 3b also shows the initial pH of the water and catalyst mixtures and the medium pH during the corn stover treatments. As the catalyst molar concentration increased, the final pH decreased, which can be attributed to the higher organic acids concentrations by increasing the catalyst molar concentration.

The values of LA yields contrasts with the results previously reported by Deng et al. [

5]. These authors reported that the combination of equimolar AlCl

3 with SnCl

2 enabled highly effective conversion of fructose, glucose and cellulose to LA, affording yields of 90 %, 81 %, and 65 %, respectively. Other results reported in the literature were lower than the values reported by Deng et al. [

5] for pure sugar monomer or polysaccharides. Chambón et al. [

21] showed that cellulose could yield 27 % and 18.5 mol % of lactic acid by using tungstated zirconia (ZrW) and tungstated alumina (AlW) as Lewis acids. Other authors [

10], reported that a LA yield of 13 % (graphical lecture) and 17 % of levulinic acid (7.5 % of formic acid and 2 % of acetic acid) was obtained from glucose when using a Sn-Beta zeolite as catalyst at 200 °C, at 2:1 catalyst to sugar ratio (graphical lecture at 3 h, where maximum of LA was reached -then decreased down to 11 % after 5 h).

In any case, as it has been highlighted by Mäki-Arvela et al. [

22] it is more challenging to produce lactic acid from lignocellulosic biomass than to produce it directly from sugar.

2.2. Effect of the Ratio Al(III)/Sn(II)

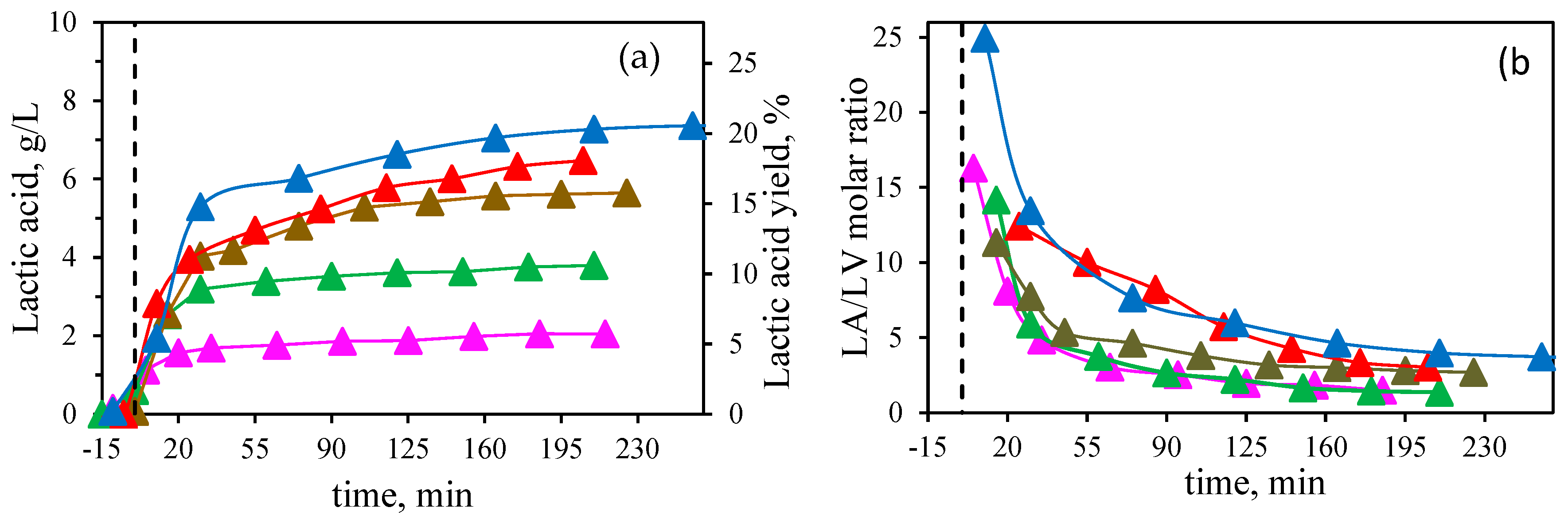

Optimizing catalyst properties is an important issue in the conversion of biomass to LA. To evaluate the effect of each metal cation, various Al(III)/Sn(II) molar ratios were tested at a constant concentration of 16 mM (the optimum one), including 1:3, 1:1, 3:1, 5:1, and solely Al(III) at 190 °C (

Figure 4).

By increasing the proportion of Al(III), both the concentration and yield of LA improved, with the highest levels achieved using only Al(III) as a catalyst, resulting in 7.4 gLA/L and a yield of 20.7%. In this work, the effect of Sn(II) was found to be not so effective in the conversion of biomass to LA. These findings contrast with those of Deng et al. [

5], who reported that an equimolar mixture of Al(III) and Sn(II) worked synergistically, achieving high lactic acid yields.

Supporting the results observed in this work, other studies have indicated that tin ions show low activity and selectivity for LA synthesis in aqueous phase [

23]. Bayu et al. [

23] suggested that the low catalytic activity of SnCl

2 in pure water is likely due to the hydrolysis of Sn(II) ions which form insoluble tin (hydr)oxide species. This is evidenced by the formation of a white precipitate of Sn(OH)Cl, as confirmed by X-ray analysis, removing the active tin species from the aqueous reaction media. These authors observed that the addition of choline chloride (ChCl) into water increased the catalytic activity and the selectivity towards LA in the conversion of trioses, monosaccharides and disaccharides [

23]. At ChCl concentrations of 40-50 %, SnCl

2 was fully dissolved, and the selectivity towards LA achieved 40-77 % under moderate conditions (155-190 ºC for 0.1-1.5 h). In contrast, LA selectivity was only ∼7% in pure water under the same conditions when SnCl

2 was used as catalyst.

In this work, to account for the lower solubility of Sn(II) species compared to Al(III), these metals were measured using IPC-MS in the solid residue generated after treatment with Al(III):Sn(II) (5:1) and solely Al(III) as catalyst. The insoluble salts resulting from the hydrolysis of metal salts (e.g., SnCl2, AlCl3) in water present different solubility. It was determined that in the Al(III):Sn(II), 5:1, experiment, 70 ± 6 % of the initial Sn (II) species added to the medium were determined in the solid residue while only 38 ± 4 % of the Al(III) species were determined in the solid residue. When only Al(III) was used as catalyst 24 ± 6 % of the Al(III) species were determined in the solid residue, supporting the less effective treatment when using Sn(II) in water.

The low activity of Sn(II) was also described in the literature by Lai et al. [

15], noting that SnCl

2 and SnSO

4 result in poor LA selectivity with the formation of significant quantities of dark brown insoluble products. This suggests that Sn(II) salts will contribute to uncontrollable condensation reactions.

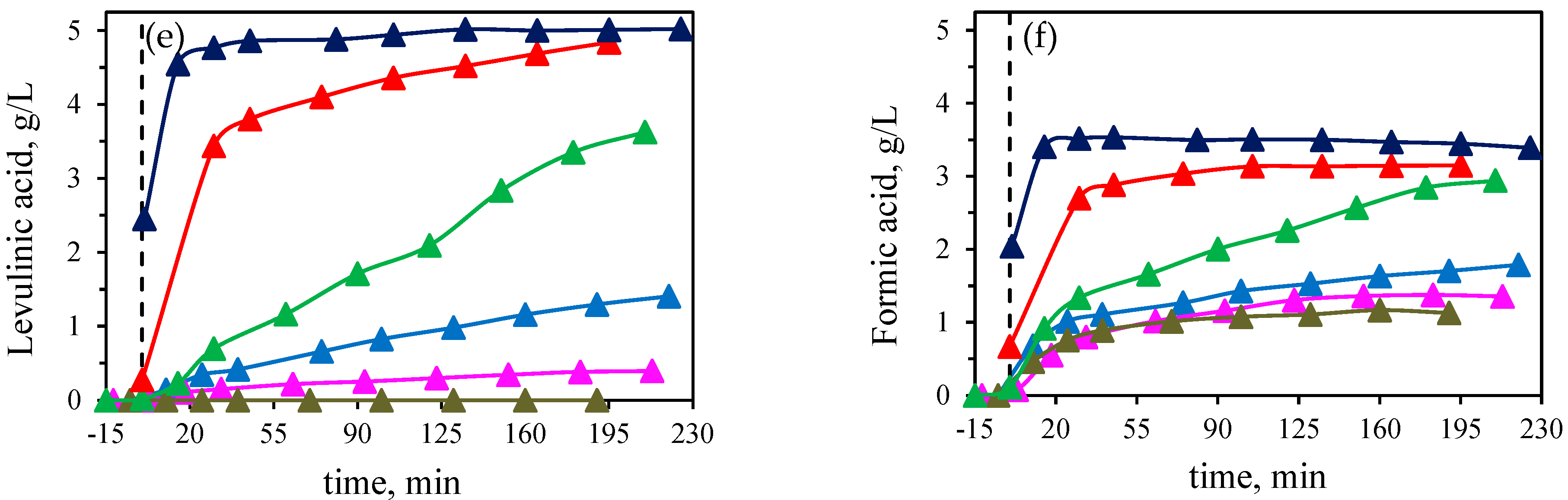

As previously described (

Figure 1), other organic acids are present in the reaction medium, being levulinic acid one of the major compounds formed. The effect of Sn(II) on the molar ratio lactic acid/levulinic acid is plotted in

Figure 4b. It can be observed that by increasing the ratio of Al(III), the molar ratio LA/LV also increased (final values in the range from 1.4 to 3.7 at 1:3 Al(III):Sn(II) ratio and only Al(III), respectively), since the presence of Sn(II) induced faster degradation of HMF into levulinic and formic acids. Thus, the presence of Al (III) was found essential for the LA formation.

Rasrendra et al [

16] also reported that the use of aluminum salts results in the formation of considerable amounts of lactic acid, 19 % of yield, when starting from glucose as raw material (C

glucose = 0.1 M) with a 5 mM of Al(III) at 140 °C. Besides the lower solubility of Sn(II) species compared to Al(III) species, according to Azlan et al. [

2], Al(III) has a small ionic radius of Al(III) ions, determined as 54 pm [

24], which along with their high charge density and strong electrostatic force, allows them to effectively interact with the substrate, facilitating the cleavage of glycosidic bonds. In contrast, Sn(II) ions have a significant larger ionic radius of 118 pm [

24], which may hinder their ability to attach on the O atoms for breaking glycosidic bonds, as suggested for Sn(IV), with a 69 pm ionic radius, by Azlan et al. [

2].

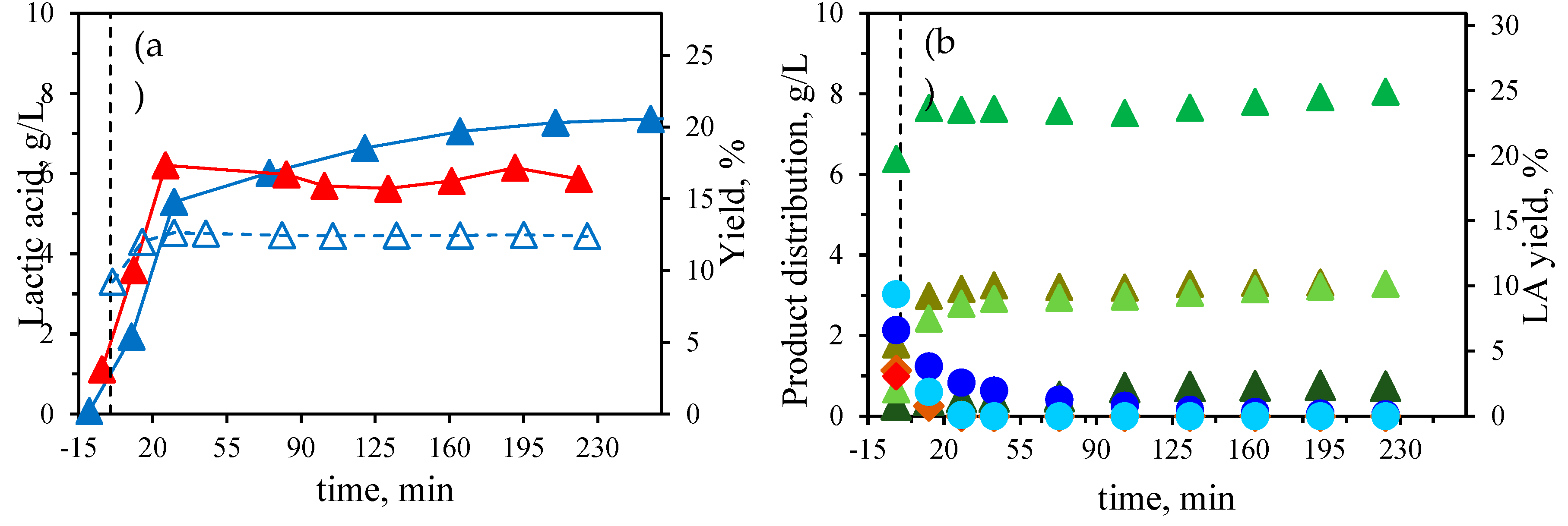

To explore the increased concentration and yield of LA with Al(III), further experiments were conducted using AlCl

3 as the sole catalyst, with the Al (III) concentration raised to 32 mM (

Figure 5a). However, increasing the Al(III) concentration up to this level did not lead to a higher LA concentration in the medium at the biomass concentration tested in this study, and 16 mM of Al (III) was considered as the optimum catalyst concentration.

Figure 5a also shows the lactic acid profile obtained with 32 mM of the equimolar mixture Al(III):Sn(II), equivalent to 16 mM of Al(III), observing lower LA yields. Therefore, it is confirmed that the presence of Sn(II) lowered the LA production.

A further kinetic study was performed using pure sugar monomer derived from biomass, to compare with the results obtained from corn stover, a type of lignocellulosic biomass, by using 16 mM of Al (III). The feedstock comprised a blend of pure glucose and xylose. The concentrations were selected based on the assumption that the entire glucan and xylan fractions of the corn stover were present as free sugar monomers in the reaction medium (glucose 20.5 g/L + xylose 13.1 g/L). The kinetic profile of the identified components has been plotted in

Figure 5b. The main component released into the medium was LA, similar to corn stover, with concentrations slightly higher than those obtained from corn stover, at 8.1 g/L (24.9 % yield). However, the production of LA was significantly faster when starting from pure sugars, as less than 15 min of isothermal treatment were sufficient to achieve stable concentrations of LA. In the case of lignocellulosic biomass, the polysaccharide fraction must first undergo hydrolysis to release sugar monomers, which are then converted into LA, thereby slowing the LA formation rate. Due to the rapid kinetic process, the sugar dehydration product concentrations continuously decreased during the isothermal process. Formic and levulinic acids were found in relative high concentrations due to degradation of HMF, as previously demonstrated, although formic acid could also result from the degradation of furfural and xylose. The main difference between the component profiles from corn stover and pure sugars lies in the acetic acid profile. Up to 2.7 g/L were obtained from corn stover due to the hydrolysis of the acetyl groups form hemicellulose, while only 0.75 g/L of acetic was formed from the glucose + xylose mixture.

Therefore, AlCl

3 has been found as an ideal catalyst for biomass conversion into LA. Furthermore, as pointed out by Guo et al. [

25], Al(III), in chloride form, AlCl

3, is inexpensive and has low toxicity.

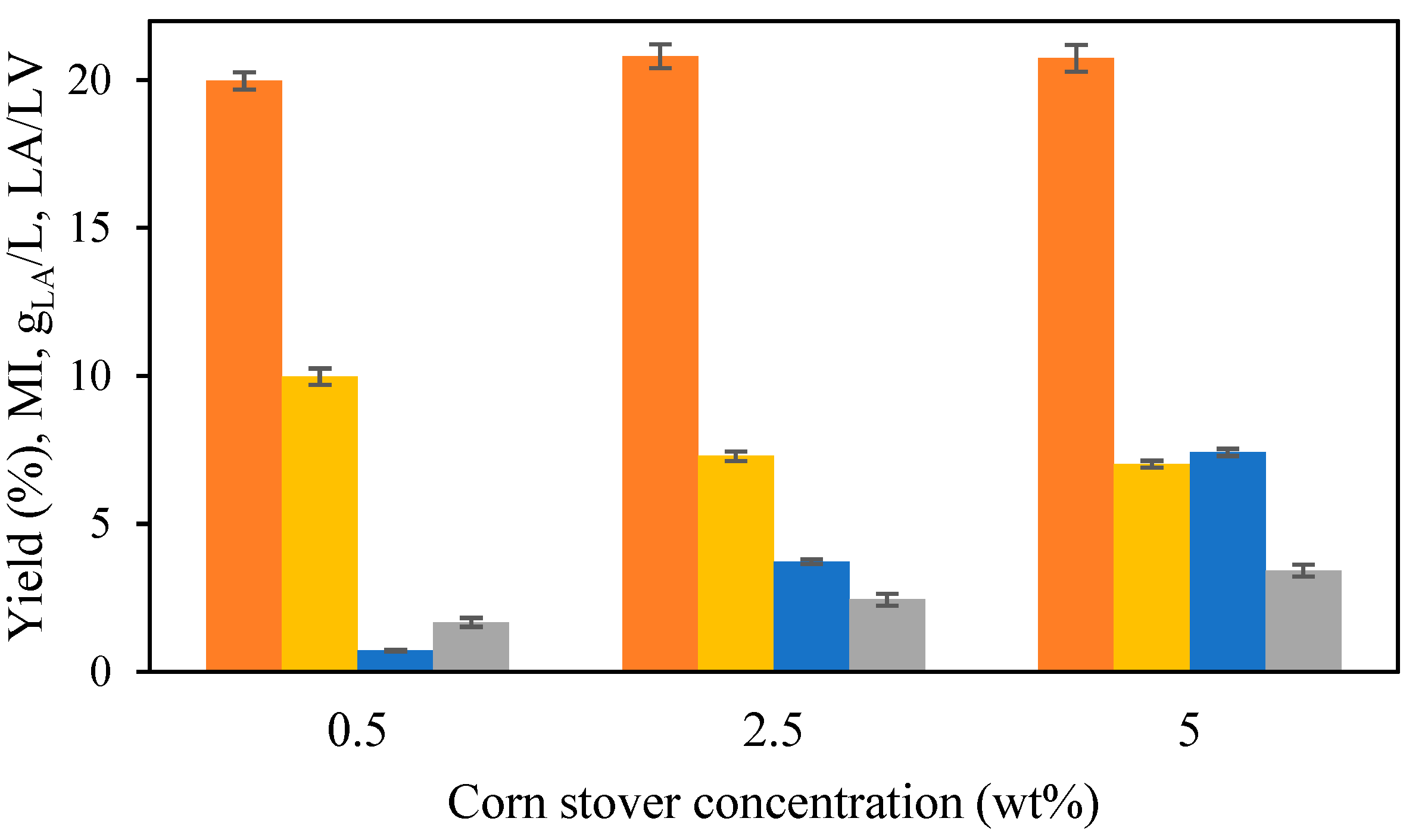

2.3. Effect of the Corn Stover Concentration

To assess the effect of biomass concentration, two additional biomass loadings were tested besides the 5 wt. % previously reported: 0.5 wt. %, and 2.5 wt. %. Experiments were conducted at 190 °C, with 16 mM of Al(III). Higher biomass concentrations were not attempted due to stirring difficulties, as reported in the study on the alkaline treatment of corn stover to produce LA [

12]. During the treatment, the percentage of corn stover that was hydrolyzed was similar across all three biomass loadings, with values of 71%, 69%, and 72% for 0.5 wt. %, 2.5 wt. %, and 5 wt. %, respectively. LA production parameters after 220 min of isothermal treatment at 190 °C are presented in

Figure 6. The LA yield showed little variation across the three different biomass loadings tested, in the range from 20 to 21 wt. %. However, the LA concentration rose with increasing biomass concentration, reaching 0.7 gLA/L, 3.7 gLA/L, and 7.4 gLA/L at 0.5 wt. %, 2.5 wt. %, and 5 wt. %, respectively. As the LA concentration increased, the molar ratio lactic acid to levulinic acid (LA/LV) also rose (

Figure 6).

To evaluate the impact of increased biomass loading and the resulting LA production, the Mass Intensity (MI) was assessed to compare the outcomes at various corn stover loadings in the reactor [

26]:

In the ideal situation MI would approach to 1. The total mass includes all components introduced into the reaction vessel, such as solvents, catalyst, and reagents, but excludes water, as water typically does not have a significant environmental impact on its own.

For a concentration of 0.5 wt. %, the MI reached a value of 10.0±0.3, but MI decreased to similar values for 2.5 wt. % (7.3±0.2) and 5 wt. % (7.0±0.1). Considering the higher LA concentration, a biomass loading of 5 wt. % was considered as the optimal.

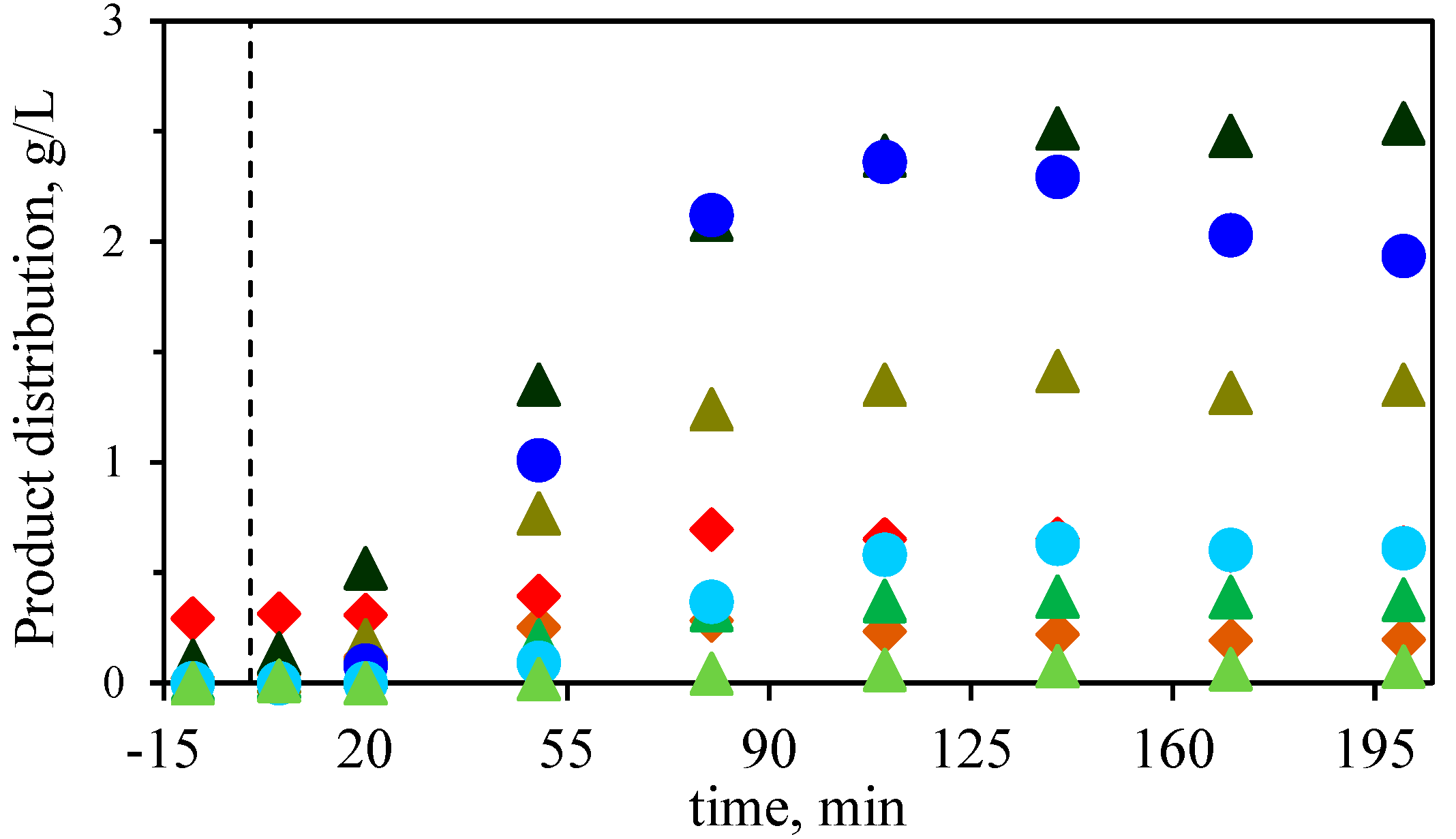

2.4. Effect of Treatment Temperature

Temperature plays a crucial role in determining reaction pathways [

15]. The breakage of the C–C bond requires high temperatures. To analyze how temperature affects lactic acid production from corn stover, experiments were conducted at three different temperatures: 190 °C, 210 °C, and 260 °C, with 16 mM of Al(III).

Figure 7a illustrates the LA profiles observed in the reaction medium at these three temperatures.

At 190 °C, a maximum in LA concentration at 7.3-7.4 g/L was reached after 210 min of isothermal treatment time, with no further degradation observed. To further confirm the thermal stability of LA at this temperature, an aqueous LA solution was prepared at a concentration of 5.8 g/L. This concentration remained stable throughout the isothermal treatment at 190 °C for 225 min of isothermal treatment, maintaining a level of 5.8 ± 0.1 g/L. Previous research using Yb

3+ (a Lewis lanthanide) as a catalyst under subcritical water conditions showed that LA suffered degradation at temperatures above 220 ºC and isothermal times longer than 20 min, corresponding to severity factors above 5.5 [

13]. The severity factor, R

o, is a common parameter that considers the combined effect of temperature and reaction time according to [

27]:

At a constant temperature of 190 °C throughout the isothermal treatment, the highest severity factor recorded was 5.2, which is below the threshold of 5.5 where LA degradation begins [

13]. By increasing temperature up to 210 °C the initial reaction rate of LA formation increased, allowing the maximum LA concentration of 7.4 g/L to be achieved more quickly, after 45 min of isothermal treatment. Longer treatment resulted in LA degradation due to increasing severity factors over time, reaching values of 5.6 by the end of the treatment at 210 °C (225 min). Nonetheless, the degradation curve was smooth, as the concentration decreased from 7.4 to 6.9 g/L after treatment.

At the highest temperature tested in this study, 260 °C, the maximum LA concentration was lower than the maximum levels achieved at 190 °C and 210 °C, measuring 5.9 g/L compared to 7.4 g/L. This suggests that LA degradation began early in the process, as the severity factor after just 7 min of isothermal treatment at 260 °C was already 5.6, surpassing the previously reported threshold of 5.5, beyond which degradation occurs. After reaching this maximum, the rate of degradation exceeded that of production, resulting in a rapid decline.

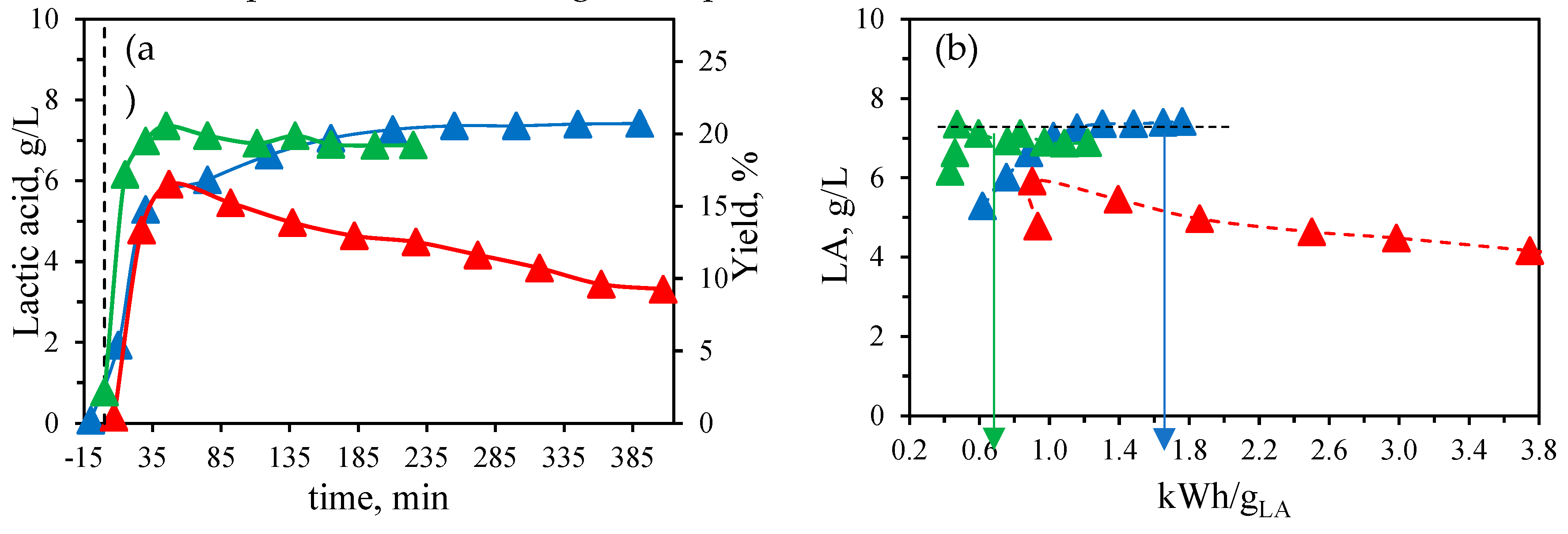

During the catalytic hydrothermal treatment with Al (III) as catalyst, the total energy consumption was continuously registered.

Figure 7b illustrates the relationship between lactic acid concentration in the reaction medium and the energy consumption per g of LA produced at the three tested temperatures: 190 °C, 210 °C and 260 °C. As previously described, a comparable maximum concentration of LA was attained at both 190 °C and 210 °C, although this peak was reached more rapidly at 210 °C. Despite the higher energy consumption recorded at 210 °C compared to 190 °C, the earlier attainment of the lactic acid peak resulted in lower energy consumption per gram of lactic acid at the maximum concentration, with values of 0.47 kWh/gLA at 210 °C and 1.2-1.3 kWh/gLA at 190 °C for the same maximum lactic acid concentration achieved in these treatments. Therefore, 210 °C appears to be an optimal temperature for lactic acid production, yielding high concentrations with minimal energy consumption at the peak. Nonetheless, it is advisable to expedite cooling after reaching this maximum, as a slow but continuous degradation of lactic acid was observed at 210 °C, whereas no degradation occurred at 190 °C. At the highest temperature tested, 260 °C, the maximum concentration was lower, accompanied by increased energy consumption per gram of lactic acid due to ongoing degradation.