1. Introduction

Atomic clocks rely on quantum physics and are affected by gravitation and dynamics. Frequency shifts of oscillators due to time dilation, are phenomena experienced daily (in GPS for example). The aim of this script is to show that a common origin, for both phenomena in gravitation and electrodynamics, exists and involves energy conservation laws. In the 60’s, Schiff [

1],[

2], claimed to have derived the first order approximation of Gravitational Time Dilation (GTD) from Special Relativity (SR) and the Weak Equivalence Principle (WEP) alone, the base of Schiff’s conjecture [

1],[

3]. By performing a careful analysis of Schiff’s derivation, it is possible to check the validity of that conjecture. The paper is articulated in the following chapters.

Section II is a revisitation of Schiff’s thought experiment on Time Dilation, of two accelerated clocks, whose ratio of their periods is re-derived pointing out some key aspects. An equivalent configuration of one accelerated clock, compared with two stationary clocks is studied, it is also obtained by applying the conservation of energy.

Einstein’s derivation in Section III brings to the same expression [

4], [

5], [

6], calculated in section II, to which the Equivalence Principle (EP) was originally applied to find the Gravitational Redshift. The remarkable differences between Schiff’s and Einstein’s derivations stimulates the application of EP to Schiff configuration.

In Section IV, the application of the EP to Schiff’s configuration is presented. It emerges that Schiff’s derivation of time dilation in absence of gravitation and the Weak EP, are not sufficient to get the GTD, conservation laws are needed.

Section V deals with Dicke’s derivation of GTD, based on conservation laws in gravitation, very close to Schiff’s derivation. At variance with Nobili

et al.’s claims [

1] both Dicke’s and Schiff’s derivations besides WEP, rely on the work of forces and mass energy equivalence. WEP and Work of the relevant interactions can be used to derive correctly the experimentally verified physical relations.

In Section VI are described the relationships between electrodynamics (SR) and gravitation for frequency shifts of oscillators at higher orders, relevant to time dilation. Schiff’s and Dicke’s derivations, relying on WEP (not on EP), and conservation laws, match with the results of GR in static gravitation at all orders of approximations. Frequency shift of atomic clocks depend on the energies at stake, referred to the Earth Cantered Inertial (ECI) frame.

2. Schiff’s Derivation of Time Dilation

An extensive revisitation of Schiff’s derivation [

2], of the variation of periods of accelerated clocks, is presented. Two alternatives are also illustrated, to arrive at the same physical relations in order to convey its importance.

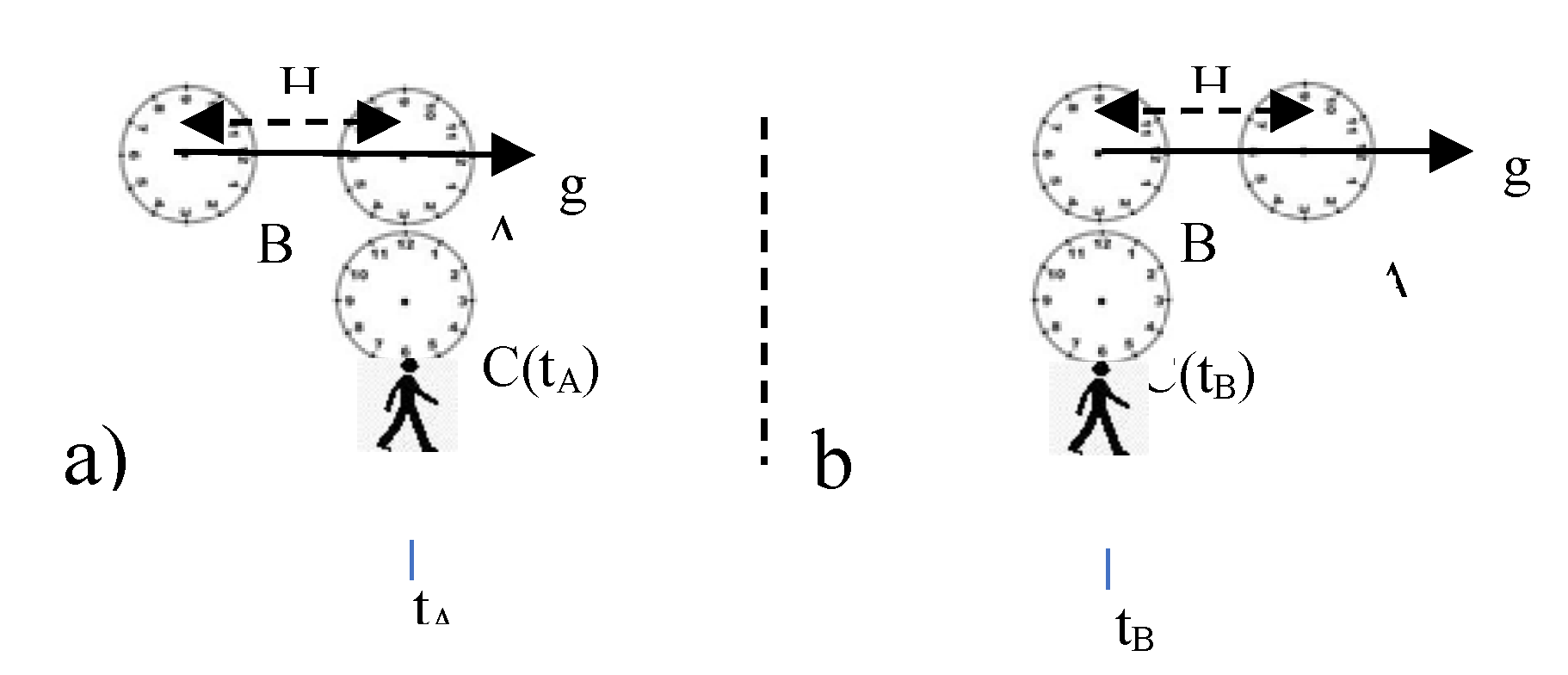

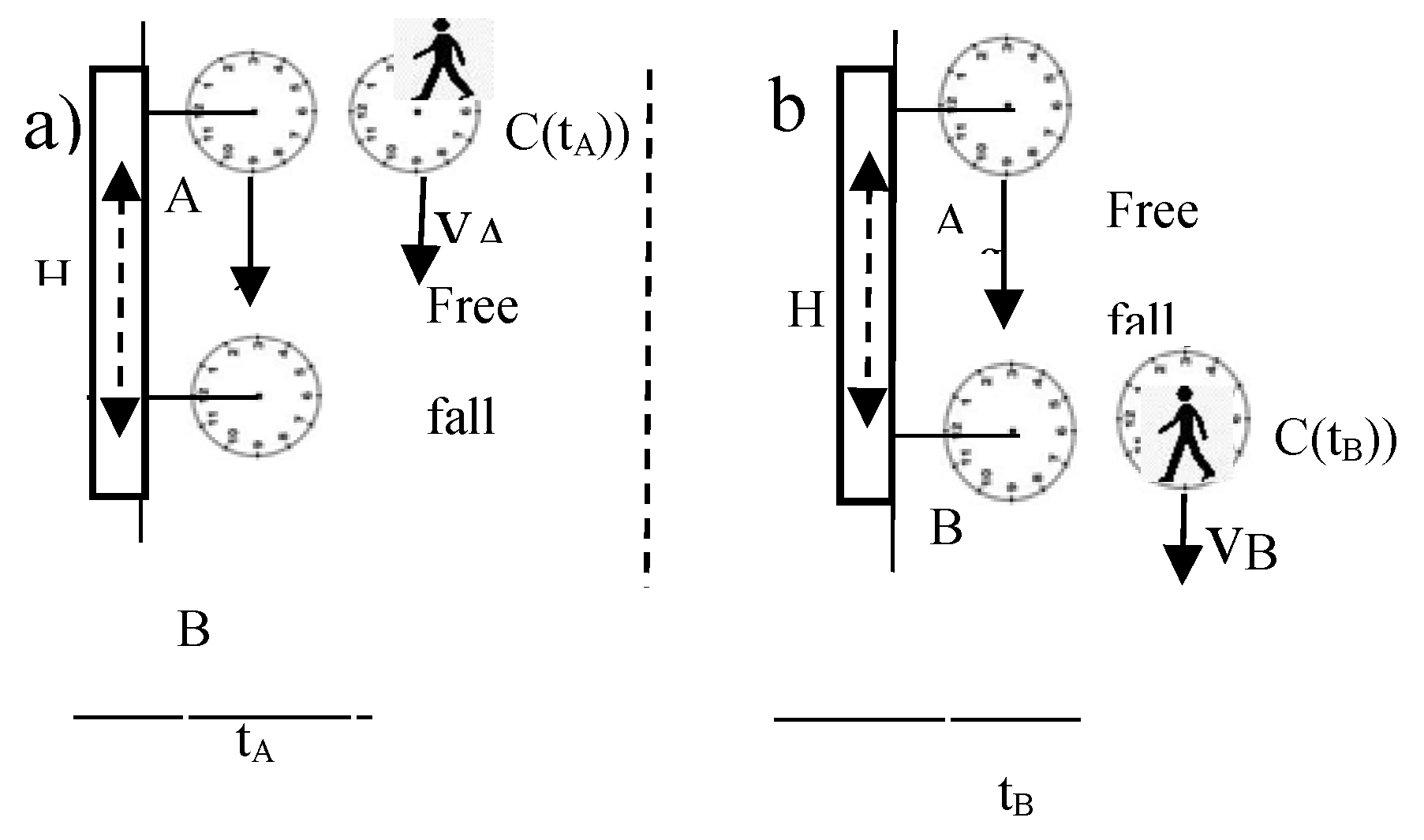

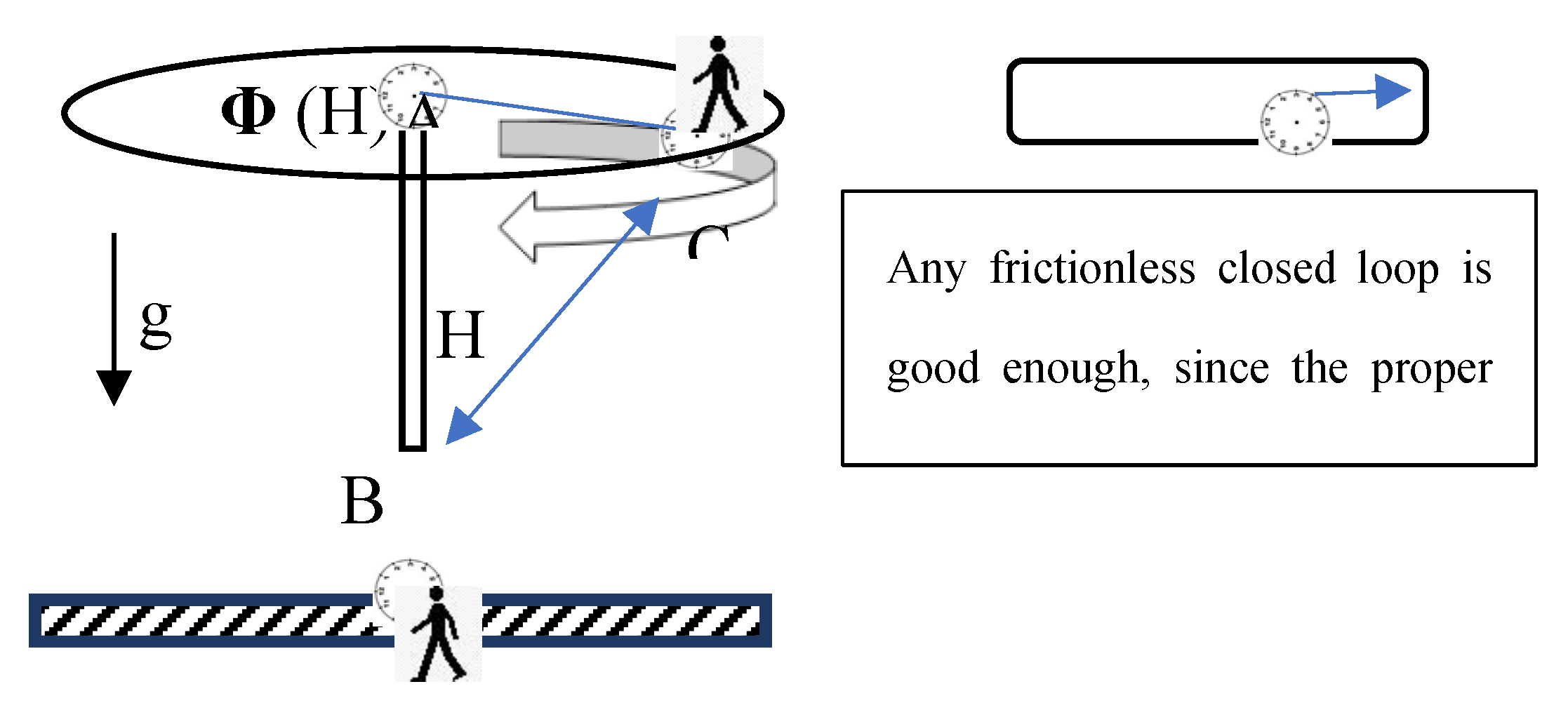

Clocks are displaced in Figure 1,2 horizontally, rather than vertically, as in [1],[2], to illustrate the sequence of events in accelerated motion, in absence of gravitation.

A, B, C are atomic clocks with same period T.

A, B are set at a distance H, B measured the acceleration g, in absence of gravitation.

vA and vB , are the speeds of each clock, as they sweep in near coincidence with C which is at rest in the inertial reference frame IRF0.

tA and tB (with tB > tA) are measured by C.

The comparisons between the periods of clocks TA (tA) and TB(tB) occurs with A at C(tA) and with B at C(tB).

From Special relativity:

T

A (t

A) = T /√(1-v

A(t

A)

2/c

2) same for B at t

B, hence

Equation (1) is a ratio of two transverse Doppler.

Being v

A/c<v

B/c<<1, by power series in v

A2/c

2 and v

B2/c

2

From kinematics, g times the displacement H , gives

From S=1/2 g*t

2 + v

0*t, where S=H, and v

A=v

0 , the following time interval is quickly derived from kinematics

That is the time taken by the system to pass from the speed vA to vB, as measured from the stationary clock C.

From Equation (4) t

B = t

A + Δt

Schiff and from Equation (3) it is

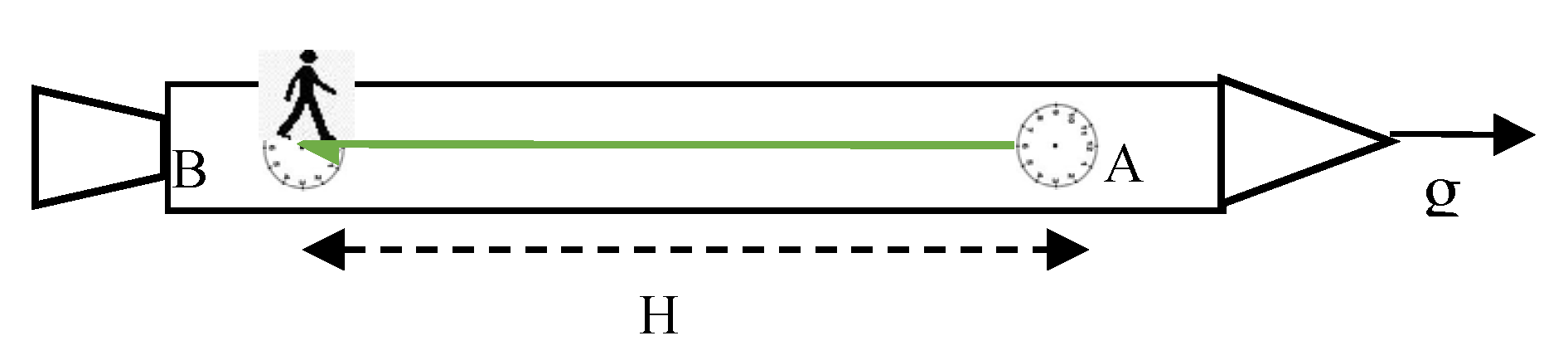

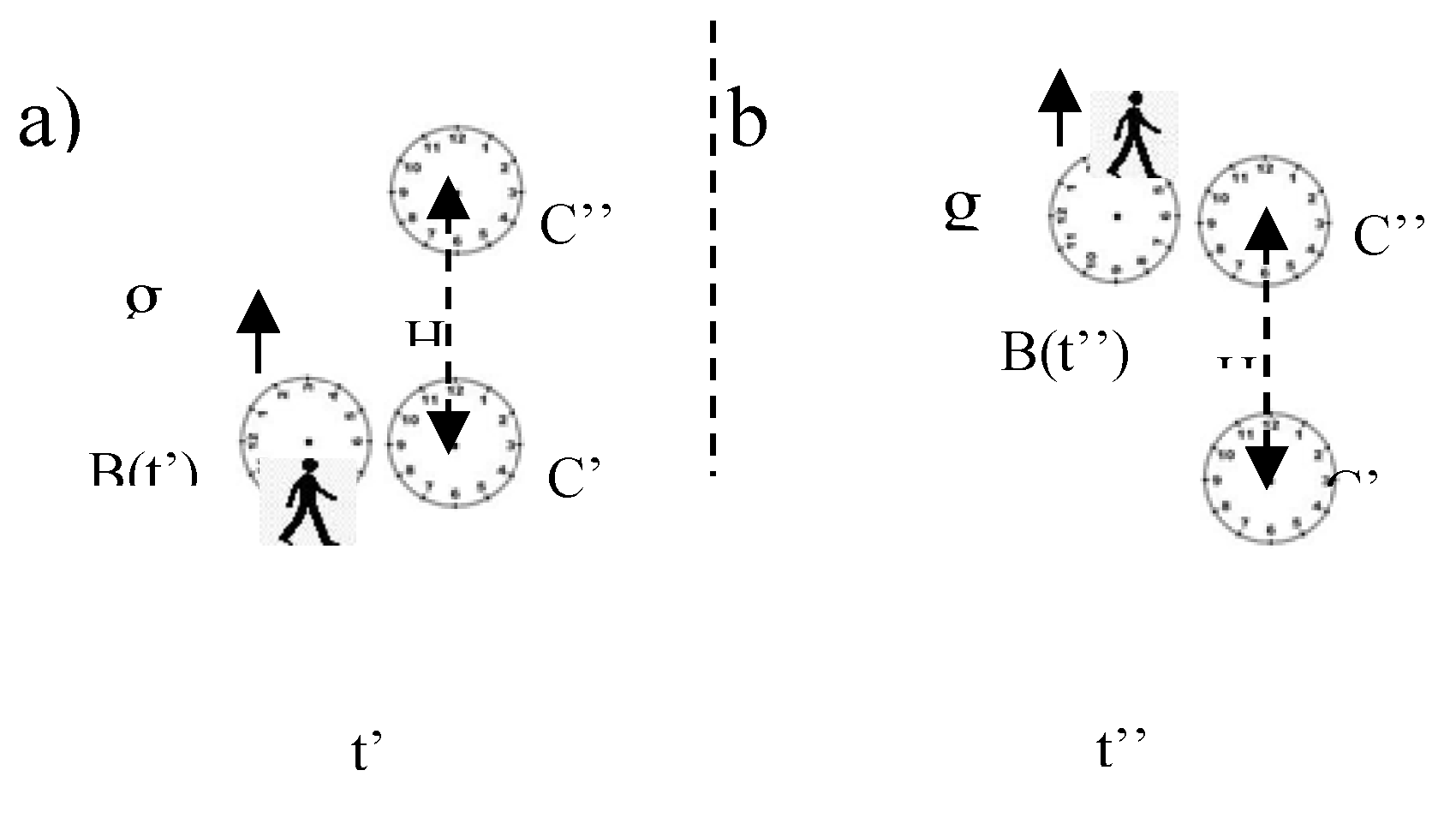

Same results can be obtained by considering only the clock B of

Figure 1, passing in front of twin clocks at rest.

The accelerated clock B faces in sequence C’ and C’’ at t’ and t’’. The same reasoning to obtain Equation (1) is followed:

TB(t’’) /TB(t’) = √(1-vB(t’)2/c2)/√(1-vB (t’’)2/c2) ≈ 1+(vB(t”)2-vB(t’)2)/2c2, being vB(t”)2-vB(t’)2=2gH, (6)

with ΔtSchiff = t’’- t’ = [√(vB(t’)2 +2gH)-vB(t’)]/g, it is

TB(t’+ ΔtSchiff)/ TB(t’) ≈ (1+gH/c2), same as Equation (5) but only the clock B is involved.

Schiff’s derivation is indeed equivalent to a comparison of the periods of one accelerated clock, along the displacement H, with two stationary clocks. The alternative derivation just proposed will be named Accelerated single clock configuration (ASCC) : two inertial observers and one accelerated observer. It provides an alternative to Schiff’s kinematical derivation, useful in paragraph four.

The dynamical version of ASCC, a third way to obtain the same results, involves an IRF

0 attached to a massive platform P (the LAB), inertial during the whole experiment. If bodies are accelerated from P, a variation of their kinetic energy is involved, as measured at rest with P. The work, performed by a force

F, provides an acceleration

g to a mass m along H, giving, the conservation of energy theorem, the following:

For atomic clocks of mass m, the above was already applied in [

10] . By considering the first order approximation of

work performed in SR

per unit of rest energy, W/mc

2 from Equation (7) : m(v

B(t”)

2-v

B(t’)

2))/2 /(mc

2) = mgH/(mc

2) the Equation (6) is obtained, hence from (1.1) also Equation (5).

The clock B in

Figure 2 is accelerated between C’ and C’’ and the variation of its rate, at the first order, is a function of the difference of its kinetic energy, per unit of its rest energy. In ASCC the ratio of frequency of oscillators in electrodynamics (SR), is mainly a consequence of the conservation of energy which also applies to the original Schiff’s derivation first illustrated.

The derivations just described give a first account about how conservation laws are connected to time dilation of atomic clocks, confirmed by experiments on transverse Doppler, and time-dilation [

7], [

8],[

9].

A review of Schiff’s derivation of variation of periods of clocks , in absence of gravitation, has been provided, by presenting two equivalent ways to compute the same quantity. Einstein’s derivation of the same relation between frequencies of oscillators is now considered and the relevant application of the Equivalence Principle is provided.

3. Einstein’s Derivation and the EP

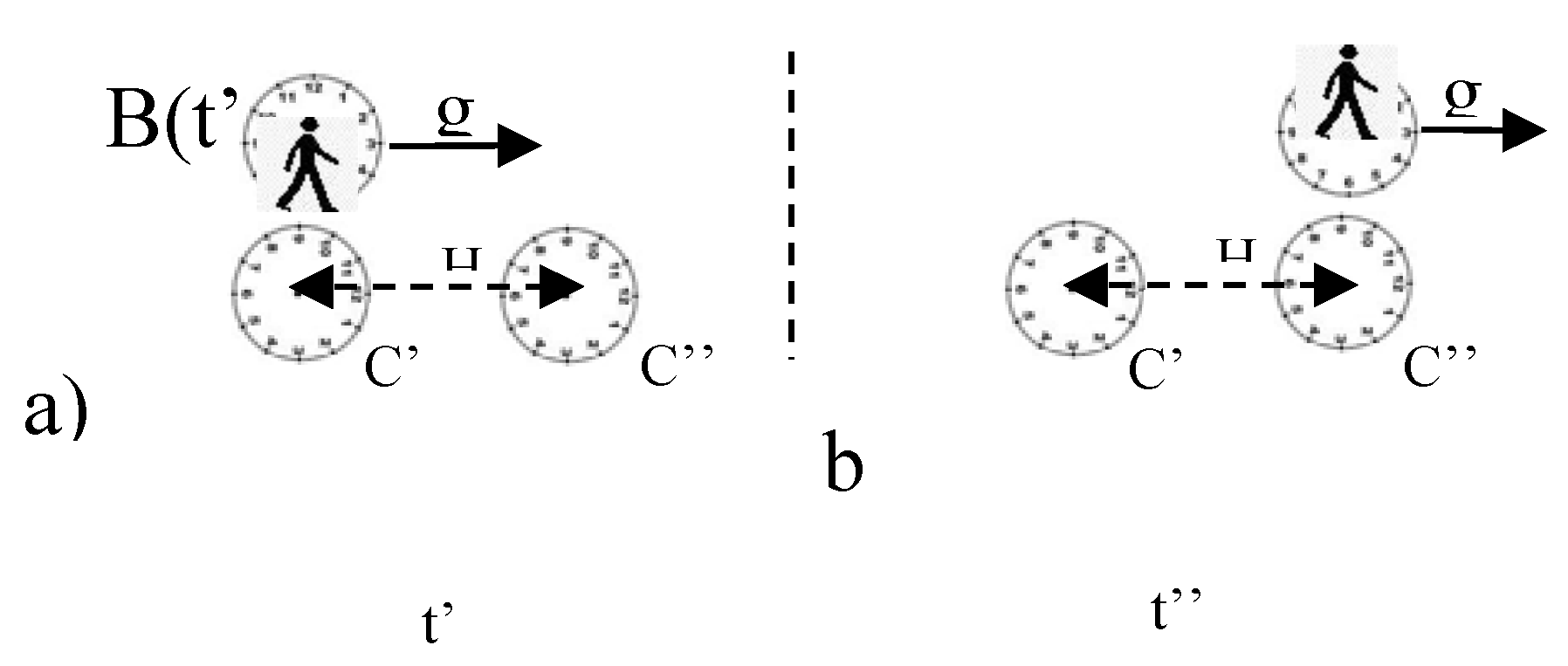

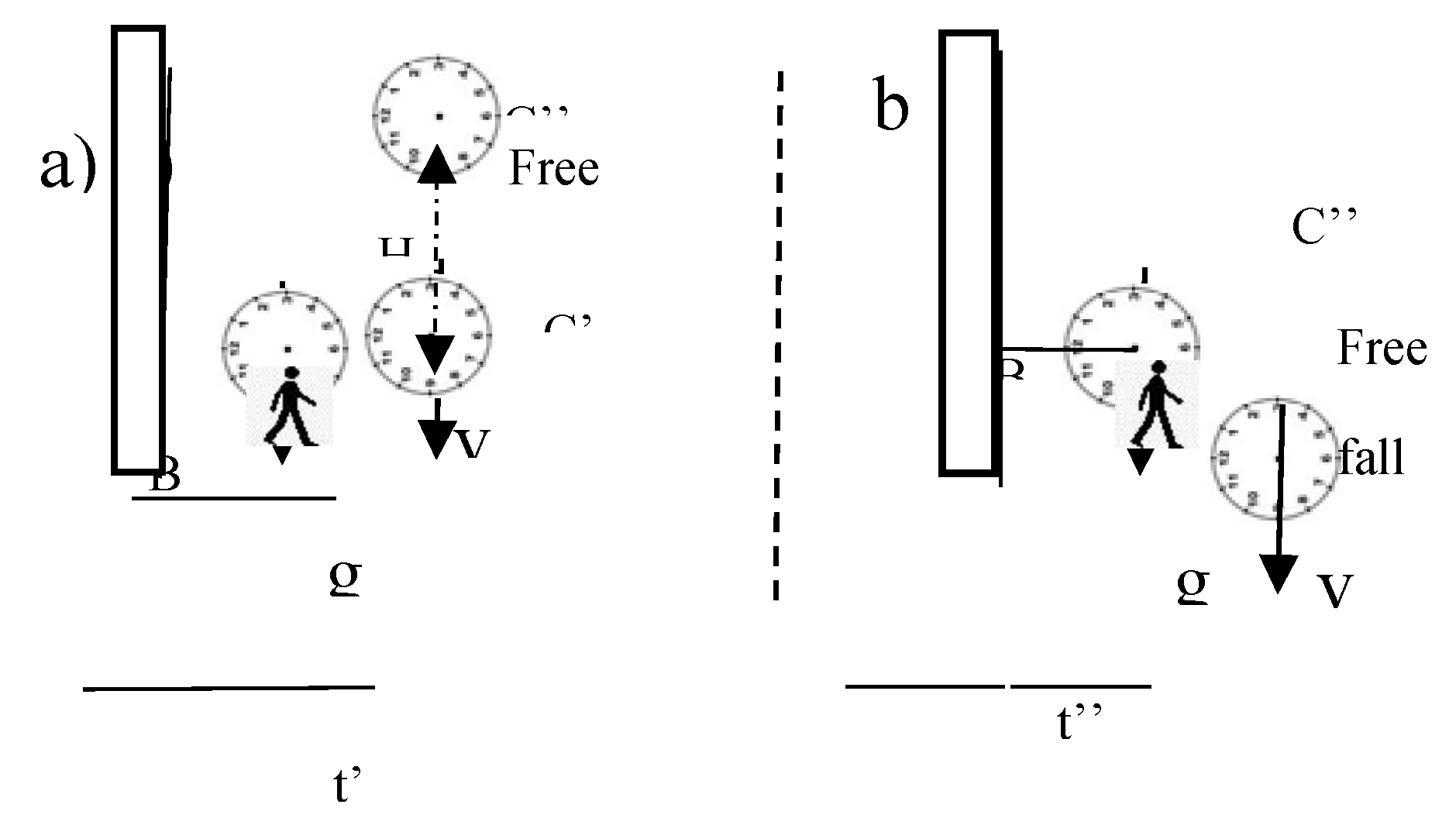

Einstein obtained the same expression as Equation (3) by involving

only two accelerated clocks, in absence of gravitation set at distance H, resorting to emission/absorption of EM waves. Feynman [

5], following Einstein’s reasoning, considered the emission of EM waves within a rocket, endowed with proper acceleration g, illustrated in

Figure 3.

The emission occurs at frequency f

A from an oscillator A, towards the observer in B, detecting f

B at the rear of the rocket. The finite travel time of the pulse, is approximated by H/c [

5],[

13]. The speed v (is not the speed of the rocket) is the instantanoeous speed of the observer B, in the IRF of emission, measured when the detection occurs. It involves a Longitudinal Doppler (LDE) for a moving observer, which gives, to the first order (v/c<<1), f

A/f

B = (1 + v/c) [

5], where v=g*H/c hence

According to SR the ratio of the proper times of the clocks, is the reverse of the frequency of the radiation exchanged [

4],[

5],[

6], hence for periods of clocks it is: T

B/T

A ≈ (1+gH/c

2);

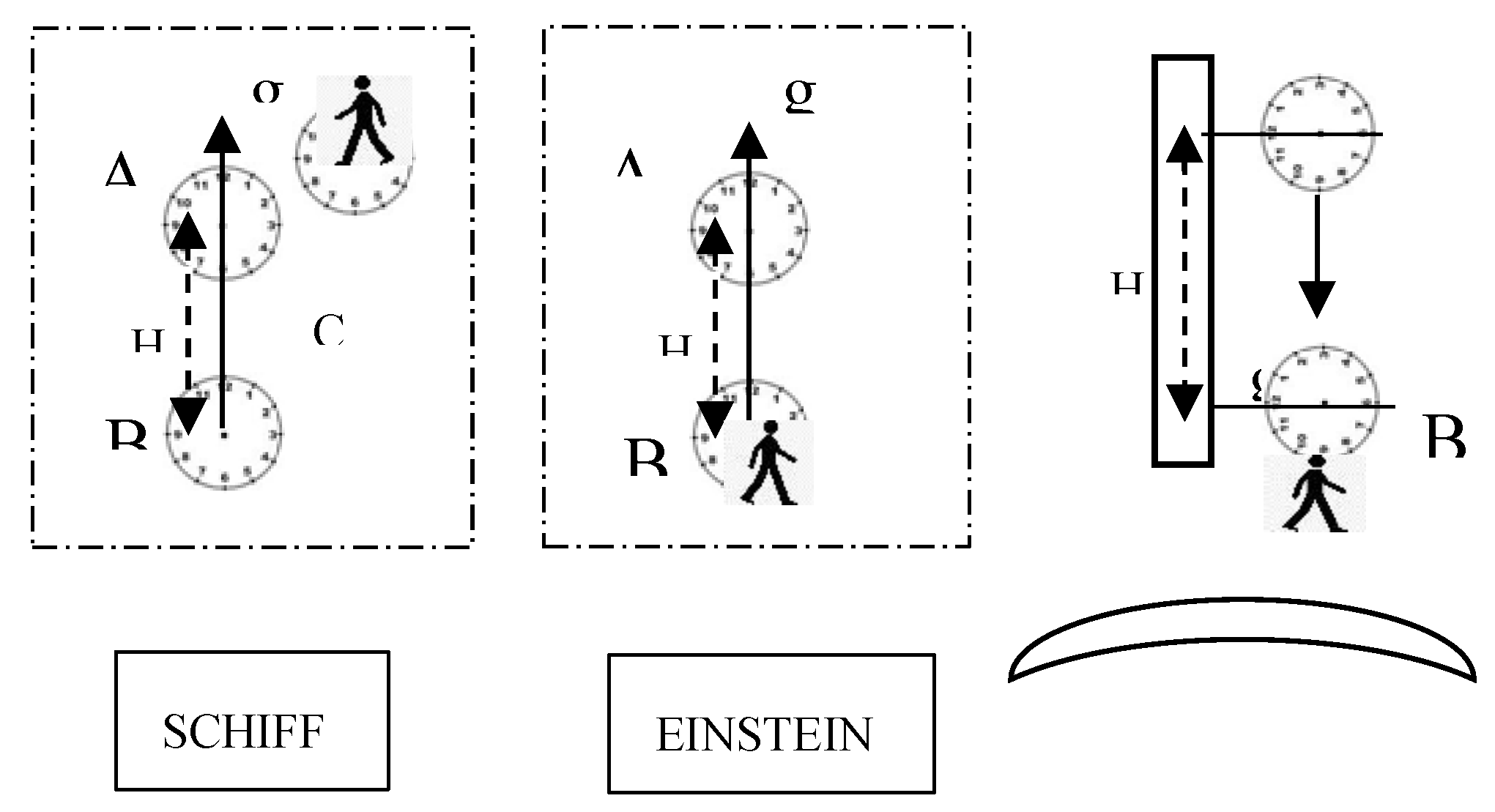

The application of the equivalence principle is now considered. The first two groups of clocks in

Figure 4, are under acceleration with no gravitation, displayed in a vertical arrangement, as originally proposed by the authors.

Equation (8) represents also, to the first order, the redshift verified in the Harvard Tower experiments [

12]. An observer, at the bottom of the Tower, detects the acceleration g and a blueshift of the incoming radiation. Similarly, at the rear of a rocket (Einstein’s case) with acceleration g, an observer detects the same blueshift of incoming radiation from a source at his front. That is the Equivalence Principle (EP) conceived by Einstein: indistinguishable configurations from local (elevator) observers. That implies a physical equivalence between a constant gravitational field and acceleration and between a free-falling frame and an inertial frame of reference.

With the application of the EP to Equation (9), where H is sufficiently short, to grant a constant gravitational field, it can be written the following [

1]

Equation (10) is experimentally tested and is the first order approximation of time dilation according to General Relativity. Schiff affirmed to have applied the WEP to his configuration in SR to obtain Equation (10). By extending such result piecewise, with Φ

g the Newtonian gravitational potential, setting ΔΦ

g = gH, for every stretch where gravitation can be considered constant,

Equation (5) and (8)-(9) belong to quite different physical configurations. Since Schiff declared to have applied the WEP to arrive at the GTD, it is quite important to check first what happens if the EP is applied.

The first observer of the

Figure 4, at rest with the stationary clock, does not detect any acceleration, a proper configuration must be found to let Schiff’s derivation comply with the EP.

4. Schiff’s Application of EP and WEP

As represented in

Figure 5, to maintain the same experiences in gravitation and acceleration, an equivalent configuration to Schiff’s in accelerated motion (the first in

Figure 4), must involve clocks in free fall.

From Straumann [

15]: “In any arbitrary gravitational field no local experiment can distinguish a freely falling

non-rotating system from a uniformly moving system in the absence of gravitation”. In

Figure 5, clocks A and B, in static gravitation are compared with C free falling.

The clock C has the same role of the stationary clock in the configurations presented in section II and an observer comoves with it. While C, freely falling, faces A, only the kinetics v

A can make a difference, whose calculations are the same as in section II, as also described in [

10]. In a similar fashion the values of the ratio of the periods of clocks in gravitation as in Equation (5), are obtained. Since the observer in both cases does not feel any acceleration, the Principle of Equivalence holds, Schiff’s configuration is compliant with EP and T

B(t

A + Δt

Schiff)/ T

A(t

B) ≈ (1+gH/c

2) as expected.

The correct application of the EP has been provided to Schiff’s derivation in SR, by exploiting the experiences of an observer in free fall and clocks at rest in static gravitation. Such derivation is totally different than Einstein’s. It is still quite unclear on which base Schiff said to have exploited only WEP to pass from time dilation in SR to GTD.

A clearer idea of the implications of the EP is provided by the application of the principle to ASCC, proposed in section II. The same arrangement is displayed vertically in

Figure 6, equivalent to the one proposed by Schiff. The observer is accelerated now, same as Einstein’s observer in the rocket.

The ASCC is characterized by clock B having a longer period when moving relative to the inertial C’ and C’’.

The counterpart of ASCC in gravitation is now named

Gravitational single clock configuration (GSCC), as in

Figure 7.

The observer in B is at rest in a gravitational field. The clock C’ is dropped from above with C’’ (inertial as the one at rest in ASCC), passing close by, at speed vC (t’).

Their period is compared with the period of B at closest distance, the observer in B, experiences the same as in ASCC.

Gravitation is the same in B, for clocks which pass by and static gravitation makes no difference. The Equation (5) is found again, thanks to the kinetics of the moving clock due to their potential [

10]. Same experiences are granted: in both cases, the observer detects the same acceleration g. The EP holds: experiences, of the observer in B, in fact, before and after the interval Δt

Schiff, provide the same ratio between clocks, as in static gravitation and identical measured accelerations.

The same result, with the configuration just illustrated, is easily obtained by lowering a body of mass m in gravitation. The amount of energy “mgH” is given away, thanks to the mechanical energy theorem [

10]. By replacing mgH with mΔΦ

g and dividing it, as well, by the rest energy, the relation between the periods is: T

C’’ = T

C’*(1+ΔΦ

g/c

2)

where ΔΦg = Φ(C’’)-Φ(C’) with Φg<0, the difference of gravitational potentials.

All the configurations in gravitation, relevant to the configurations in section II, have been analyzed.

The EP was exploited in its full form with free-fall/inertial-motion and static-gravitation/ acceleration. It is evident that, in all configurations, conservation of energy plays a fundamental role, both in absence (ASCC) and in presence of gravitation (GSCC). Such principles can be considered implicit in the application of the EP.

WEP and SR are not enough to find the gravitational time dilation, it would be impossible to obtain the values of the gravitational time dilation without conservation laws. The gravitational potential is not determined by WEP. Conservation Laws (CL) in gravitation are needed to arrive at an expression of GTD valid to a first order approximation.

5. Conservation Laws - Dicke’s Derivation

Equation (5), for oscillators in electrodynamics, has the same form as in gravitation up to a first order approximation, although SR and WEP should not be sufficient at all to arrive at the GTD. In the 60’ as well, Dicke affirmed [

1]: “The red shift can be obtained from Eötvös, mass-energy equivalence, and the conservation of energy in a static gravitational field…”.

Dicke’s derivation of the gravitational redshift [

11] at the first order (a direct consequence of the GTD) and also Feynman’s [5- (42.12)], followed also by other authors [4 – (pag.17)], involves quanta of EM radiation. SR is necessary for Dicke’s derivation, but also the conservation laws in gravitation.

Dicke’s derivation of GTD considers an atom, excited by a quantum hν0, then lifted for a height H. A work W must be performed, against gravitation along H, on the relevant mass hν0/c2 of the absorbed quantum, such that W= gH*hν0 /c2. Then the atom de-excites by emitting back, from above, the quantum of EM radiation, detected blue shifted by the quantity hν0(gH/c2), to avoid a perpetuum mobile. That implies hν = hν0(1+gH/c2) or hν = hν0(1+ΔΦg /c2) which gives the formula of the gravitational frequency shift: Δν/ν0= ΔΦg/c2.

As showed so far, Schiff’s and Dicke’s derivations of GTD, are based on same principles, obtaining, from quite different mechanisms, effects of the same class of phenomena to the first order approximation.

WEP, certifies the equilibrium balance between the interactions (Fa=Fg) whose displacement of their point of application occurs in free fall of bodies, irrespective of their composition. But how the free falling occurs in time (worldline), depends on the kinetics of bodies in a center of gravitation, hence it relies on the conservation of energy.

In the Earth Centered Inertial frame (ECIF), the conservation of energy in electrodynamics + WEP + energy conservation in static gravitation, determine the work necessary to change the speed of a unit mass.

The work of forces, WEP and mass energy equivalence, establish a relationship between periods of clocks in electrodynamics and gravitation. With ν the frequency of the clock ΔT/T = -ΔΦa/c2= ΔΦg/c2 ≈ - Δν/ν

When both static gravitation and electrodynamics are involved in a physical configuration, the previous can be written as

That formula can be found in [

5] when Feynman derived the variation of the rates of the clocks illustrating the action principle. In the previous section the kinetics of free fall was just a consequence of the differences of gravitational potential at which, according to the Conservation laws (CL), the two clocks were set before free falling.

In reference to Schiff’s derivation, of the gravitational redshift ΔΦ

g/c

2=Δf/f , it was declared by Nobili et al. [

1]: “it is important to stress that it has been obtained using neither the conservation of energy nor the mass-energy equivalence, all that is required is that the clocks obey the WEP like ordinary bodies and the special theory of relativity”. On the contrary, although the EP is sufficient to pass from SR to GR at the first order, involvement of conservation laws cannot be avoided together with WEP. In Schiff’s configuration the application of EP involves implicitly an application of conservation laws.

Slow speeds have been considered so far and short distances, for first order approximations. Since Equation (1) is exact, nothing would forbid to extend Schiff’s derivation of GTD to higher orders. The results of the previous section, derived with the EP, could be extended naturally to higher orders if acceleration and gravitation were measured the same, granting same experiences, but it is not the case. To provide a suitable connection between time dilation in electrodynamics and gravitation to higher orders of approximation, the price to pay, is to drop the “physical equivalence”, resorting only to conservations laws.

6. WEP and Energy Conservation

High speeds and non-straight trajectories are now considered. Conservation laws and WEP would make it possible to support a transition from electrodynamics to gravitation to find GTD in such cases, while the EP would stop to a very limited first order approximation in time, space and speed.

Frequency shifts of clocks in centrifuges were verified by Kündig, considering the formula Δf

cl /f

0 ≈ -1/2 v

2/c

2 [

16] . It means that the detected frequency shifts of photons is Δf

ph/f

0 =ΔT

cl/T ≈ 1/2 v

2/c

2 with f

0 the emitted frequency at rest, a first order approximation of

where γ = 1 /√(1-v2/c2). The general relation is expressed by Equation (1) and presented also in [20- 4.2] , suitable also for rotations.

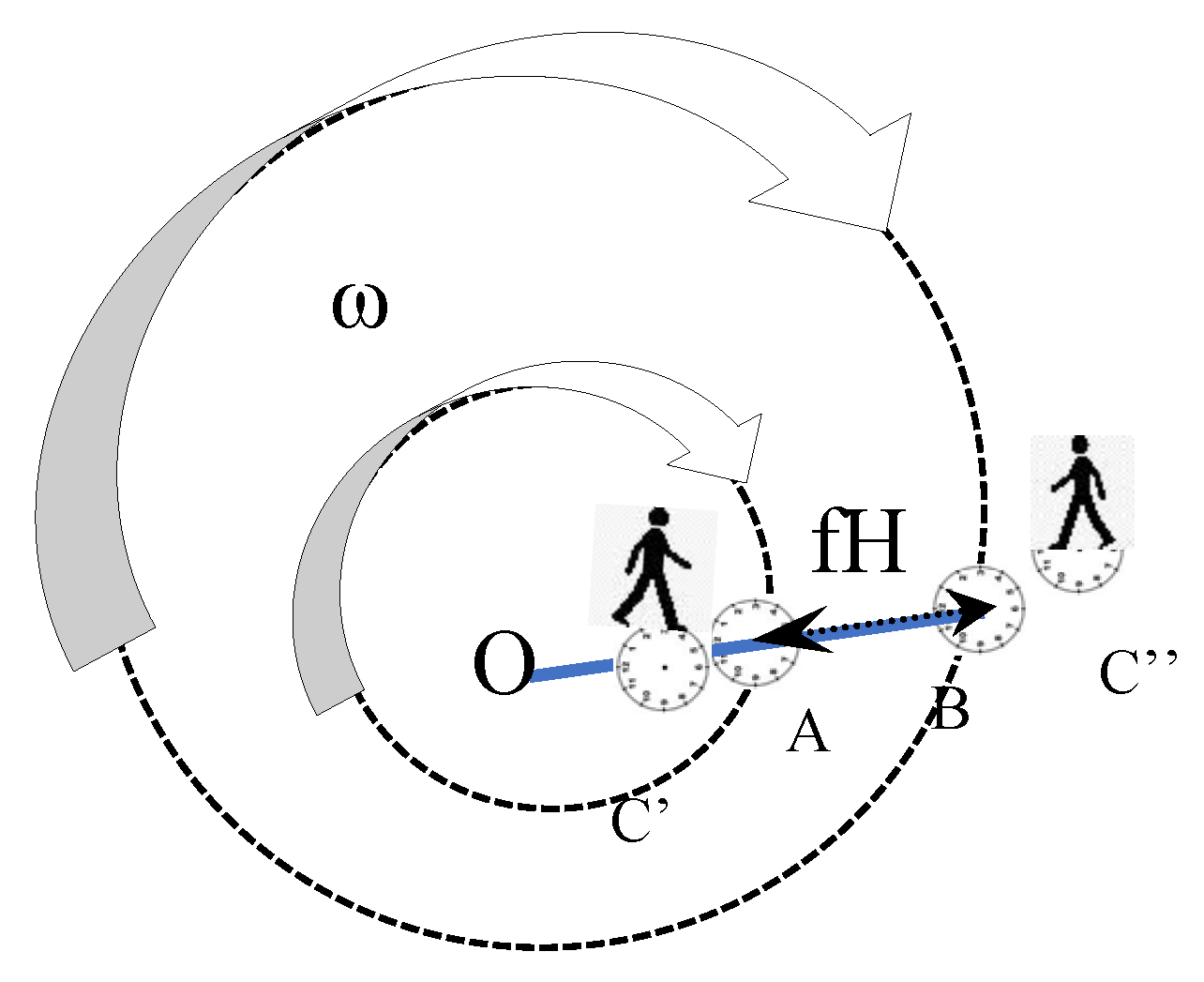

A and B, in circular motion, are attached to the same shaft (same angular speed ω, around O) as in

Figure 8 while C’ and C’’, are at rest: A passes close to C’ and B close to C” along the same shaft.

Since, in the very short period T, as measured from each stationary clock, the trajectory is virtually a straight line, it is possible to follow again the reasoning already followed in section II and obtain Eq(1). Since vB = ωrb > ωrA= vA , for detected photons it becomes fB/fA=√(1-vA2/c2)/√(1-vB2/c2)) >1, meaning that there is a blueshift if light passes from A to B.

The work of a force F=dp/dt =d(mvγ)/dt, to provide a speed v0 to a mass m in a IRF, is the relativistic Kinetic Energy W== = (γB-1) E0 =Krel

Since the variation of kinetic energy in general is ΔK

B,A = - E

0 (γ

A-γ

B) >0 , from Equation (14) ΔT/T *E

0= E

0 (γ

A-γ

B)/γ

A, hence

With A stationary, ΔT/Tcl= -ΔKB/ E0, the variation of the period of an oscillator B is a variation of its relativistic kinetic energy per unit of rest energy, referred to an inertial frame.

It is ΔT/T = -ΔΦc/c2, where ΦR(r)c = c2(γ-1) representing the relativistic centrifuge potential, with Φ(0)c=0 and

U = mc2(γ-1) = E0 (γ-1) the rotational K.E., a form of “potential energy”.

Schiff’s derivation in SR is extended to support more general configurations. Dicke’s reasoning in gravitation is extended to centrifugal configurations. In such cases, one must consider the work to provide the absorbed quantum with the same kinetics belonging to the point of absorption on the disk. The energy shift previously found, as hν = hν0(1+ΔΦg /c2) or hν0(1+1/2v2/c2), at higher orders becomes hν = hν0γ. From hν-hν0= (γ-1) hν0, it is found again ΔE/ E0 = (γ-1), where E0 (γ-1) is the potential energy of the mass relevant to the absorbed photon. A photon, departing from the center of a disk, will be detected blue-shifted by an observer sitting on the disk, complying with Kündig’s results.

Kündig [16 - Equation (3)] used the relation fB/fA = √(1+2Φed/c2), in static gravitation, Okun used instead E0 lab/E0 loc = dτ/dt= √(1+2Φg/c2) [18-Equation (9)].

Considering the substitutions in the ECI frame vA2/2 =-ΦA, vB2/2 =-ΦB in Equation (1), it is TB/TA= √(1+2ΦA/c2)/√(1+2ΦB/c2)

which is the ratio of the period found according to the Schwarzschild solution of GR in static gravitation.

The most general “relationship” between electrodynamics and gravitation has been obtained, involving conservation of energy, that covers all the orders of approximation,

hence ΔT/T = ΔU

rel/E

0 , by including the kinetics

Equation (15) accommodates inertial and gravitational effects on variation of frequency of oscillators, as referred to the ECI frame. Equation (1) becomes, with v2 = -2Φ (with Φ and v referred to the ECI frame), the GTD according to General Relativity.

Dicke’s original derivation gets automatically extended to support higher order effects by considering the “extended gravitational potential energies” ΔUrel

Fock [

21]: “We see the experimentally established presence of a frequency shift in the Gravitational field and the possibility of compensating it by a transverse Doppler”.

Following Fock’s reasoning, a circular guide (

Figure 9) in static gravitation, with no friction, suspended with a clock A at its center, drives a moving clock C at speed v, and a clock B is set below at distance H. In the configuration of

Figure 9 the effects of kinetics and static gravitation combined give, according to the Schwarzschild solution of GR

Since no orbital motion is involved, replacing

vC2 with Φ

C is not possible. If the cancellation of the two effects is imposed by T

B/T

C =1, then

The cancellation of gravitational effects with kinetics, as expressed by Equation (16), named “zero beat”, can be found in the NASA official report of GP-A experiment [

22]. It is valid to all orders of approximation and guarantees that there is no frequency-shift between C and B, according to GR. A blue-shift of radiation occurs for A-C same for A-B (redshift C-A same as the gravitational redshift B-A). WEP and conservation laws makes the frequencies of oscillators in ED and static gravitation match to any order of approximation. That gives a consistent common ground to all the configurations presented. The previous derivations resorted to WEP and conservation laws in their full form, avoiding the use of EP.

7. Conclusions

It is well known that a “physical equivalence”, is a very strong requirement, valid only locally especially due to the “tidal effects” of the gravitational field. The following results emerged:

- (1)

The kinetic energy theorem and mass energy equivalence are sufficient to account for the frequency shift of oscillators in electrodynamics, relevant to the time dilation at fist order.

- (2)

The application of the EP has been provided to Schiff’s original configuration. That helped to clarify that WEP cannot be sufficient to obtain the gravitational time dilation without conservation laws.

- (3)

Schiff’s and Dicke’s derivations, by applying the same principles, arrive at the gravitational time dilation from quite different viewpoints, hence SR + WEP + CLGrav → GTD , at variance with Nobili et al.’s claims.

- (4)

Schiff’s and Dicke’s derivations of the gravitational redshift/time dilation, are extended to higher orders, attaining a complete match with GR’s predictions for static gravitation.

- (5)

Variations of relativistic kinetic or potential energy per unit of relativistic energy, referred to the ECI frame, account for the frequency shifts of oscillators in static gravitation relevant to time dilation, in agreement with General Relativity.

References

- A. Nobili et al. “On the universality of free fall, the equivalence principle, and the gravitational redshift” Am. J. Phys. 81 (7), (2013).

- L. Schiff “On experimental tests of the General Theory of Relativity”Am. J. Phys. 28, 340–343, (1960).

- C. Will “The confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment” Living Reviews in Relativity volume 17, Article number: 4, (2014).

- H. Schwartz “Eintein’s comprehensive 1907 essay on relativity part II-III”, Am. J. Phys. 45 (9), (1977).

- R. Feynman “The Feynman Lectures on Physics”, Vol. 2 Ch. 42.6, (1965).

- S. Boughn “The case of the identically accelerated twins” Am. J. Phys. 57 (9), (1989).

- J. Bailey “Measurements of relativistic time dilatation for positive and negative muons in a circular orbit” Nature, 268-5618,pp. 301-305, (1977).

- D. Hasselkamp, E. Mondry, A. Scharmann, “Direct observation of the transversal Doppler-shift” A. Z Physik A, 289: 151, (1979).

- B. Botermann et al., “Test of Time Dilation Using Stored Li+ Ions as.

- Clocks at Relativistic Speed” Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 239902 (2015).

- T. Cheng “A College Course on Relativity and Cosmology” Oxford University Press, 4.27 box 4.1, (2015).

- R. Dicke, “The Theoretical Significance of Experimental Relativity” Blackie and Son, London and Glasgow, (1964).

- R. Pound and J. Snider, Effect of Gravity on Nuclear Resonance, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 539, (1964).

- A. Einstein “On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light”, Annalen der Physik, 35, pp. 898-908, (1911).

- R. Vessot, M. Levine “Test of Relativistic Gravitation with a Space-Born Hydrogen Maser” Phys. Rev. Lett. vol 45 number 26, (1980).

- N. Straumann “General Relativity with applications to astrophysics”, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, (2004).

- W. Kündig “Measurement of the transverse doppler effect in an accelerated system” Phys Rev, 129 (6) pp. 2371-2375, (1963).

- F. Hawley, K. Holcomb “Foundations of Modern Cosmology” Oxford university press pp 221-222, (2005).

- L. Okun, K. Selivanov, V.Telegdi “On the interpretation of the redshift in a static gravitational field” Am. J. Phys. 68 115 (2000).

- N. Ashby “Relativity in the Global Positioning System” Living Rev. Relativ. 6, 1 (2003).

- G. Giuliani “On the Doppler effect of photons in rotating systems” EJP 35-2 (2015).

- V. Fock “The theory of Space, Time and Gravitation”, Pergamon, p.188-51.20, (1964).

- Nasa Technical reports, “Gravitational redshift space-probe experiment” pp. 62,70 (1979).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the indivdividual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).