1. Introduction

Lung cancer remain one of the most common causes of cancer related mortality in worldwide, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for approximately 85% of cases [

1]. Among the various subtypes of NSCLC, mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene play a crucial role in lung tumorigenesis, making EGFR a primary therapeutic target [

2].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogenous lipid bilayer nano-vesicles released into the extracellular space by almost all cells in the body in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions [

3]. They are able to facilitate intracellular communication by transporting various bioactive molecules, such as proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (including DNA, RNA, and microRNAs), and other metabolites and signaling molecules that reflect their cell of origin [

4]. Upon secretion, EVs can expedite both paracrine and endocrine signaling by transporting their cargo to specific target cells, thereby regulating the activity and behavior of the recipient cells [

5].

Depending on their size and biogenesis pathway, EVs are classified into three main groups. Exosomes (also referred to as small EVs, sEVs) have a size range of 30-200 nm and are constitutively produced through the budding of late endosomes known as multivesicular bodies (MVB) containing intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) [

6]. When the MVB merges with the plasma membrane, it releases exosomes into the extracellular microenvironment [

7]. Microvesicles are bigger in size ranging from 100 nm to 1 µm and are formed directly through budding from the plasma membrane in the process of ectocytosis [

8]. Apoptotic bodies are less studied EVs range from 50 to 5000 nm in diameter and are formed during plasma membrane blebbing or when the cells undergo programmed cell death during apoptosis [

9].

During cancer progression, cancer cells release an increased amount of EVs, with significant changes in their cargo. These alternations in their composition enhance communication within the tumor microenvironment, promoting metastasis to distant organs or stimulating immune responses [

3,

10]. However, the precise mechanism underlying EV biogenesis and its subsequent effect on recipient cells is still not fully understood. Given the critical role of EVs in cellular communication and cancer progression, it is essential to understand the signaling pathways that influence their biogenesis and release. One such pathway is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway, which is frequently dysregulated in various cancers, including lung cancer.

The EGFR signaling pathway, also known as ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), play a crucial role in various cellular processes such as proliferation, survival, migration and differentiation [

11]. EGFR can be activated by multiple ligands, including epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-α), amphiregulin (AREG) and others [

12]. Upon ligand binding, EGFR undergo dimerization and autophosphorylation, initiating downstream signaling pathway cascades, such as the Ras/Raf//MAPK, PI3K/Akt and JAK-STAT pathways, which regulate key cellular processes involved in cancer progression [

13]. Dysregulation of EGFR signaling, either through receptor overexpression, constitute activation of the receptor due to gene mutation or ligand stimulation, is frequently observed in NSCLC and is associated with poor progression and resistance to therapy [

13,

14]. EGFR activating mutations (exon 19 deletion and L858R point mutation) are present in 10-20% of Caucasian patients and in 50% of Asian patients. The mechanism by which EGFR influences tumor behavior and intercellular communication through the modulation of EV biogenesis and alteration of their cargo is not fully understood.

Previous studies have reported that the formation of MVBs during biogenesis of EVs can be stimulated by growth factors as the cells modulate its production of EVs based on its requirements [

15]. A recently published review article by Ferlizza et al. [

16] demonstrated that EGFR pathway has role in the biogenesis and function of EVs. EGFR can modulate the composition and release of EVs, thereby affecting their ability to mediate communication between cancer cells and the surrounding stromal cells.

However, low levels of phosphorylation lead to EGFR undergoing Clathrin-mediated endocytosis and recycling. Conversely, high levels of phosphorylation result in EGFR being ubiquitinated and recognized by the ESCRT complex, which then directs pEGFR to intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) and potentially to lysosomes for degradation. Furthermore, EGFR mutations may lead to increased auto-phosphorylation and MAPK signaling in certain cancers, such as NSCLC, displaying abnormal ubiquitination [

16,

17].

Since the luminal cargo of EVs reflects the cellular context of origin and contains bioactive molecules that are actively expressed during the process of packaging and release [

18], EVs released upon EGFR activation in lung cancer may carry mutated forms of EGFR, oncogenic proteins, various types of nucleic acids, especially microRNAs, and other signaling molecules.

Previous studies reported that pEGFR and other receptor tyrosine kinases can be detected in EVs purified from the plasma of tumor-bearing mice and from the conditioned media of cultured cancer cells [

19]. However, the mechanisms by which mutant EGFR in lung cancer affect the biogenesis and cargo composition of EVs have not been thoroughly investigated. On the other hand, numerous investigations have shown that several miRNAs are involved in the regulation of EGFR expression in cancer. Particularly, EGFR expression is regulated by mir-128-b [

20], mir-21 [

21], and mir-494 [

22] in lung cancer. Still, how these miRNAs are regulated in EVs upon EGFR activation is not well understood.

Understanding the exact effects of the EGFR activation on the features and functions of EVs is necessary to learn more about how tumors grow and what therapeutic targets might be useful. Generally, the different cargo contents of EVs can make them promising candidates for biomarkers, enabling the non-invasive monitoring of disease onset and progression.

In the present work, we aimed to isolate and characterize EVs released by two lung cancer cells: PC9 lung cancer cell line harboring mutant EGFR in exon 19, and A549 lung cancer cell line wild type for EGFR. In addition, we investigated, if mir-128, one of the target miRNAs for EGFR, is dysregulated in these cell lines and EVs released by them.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

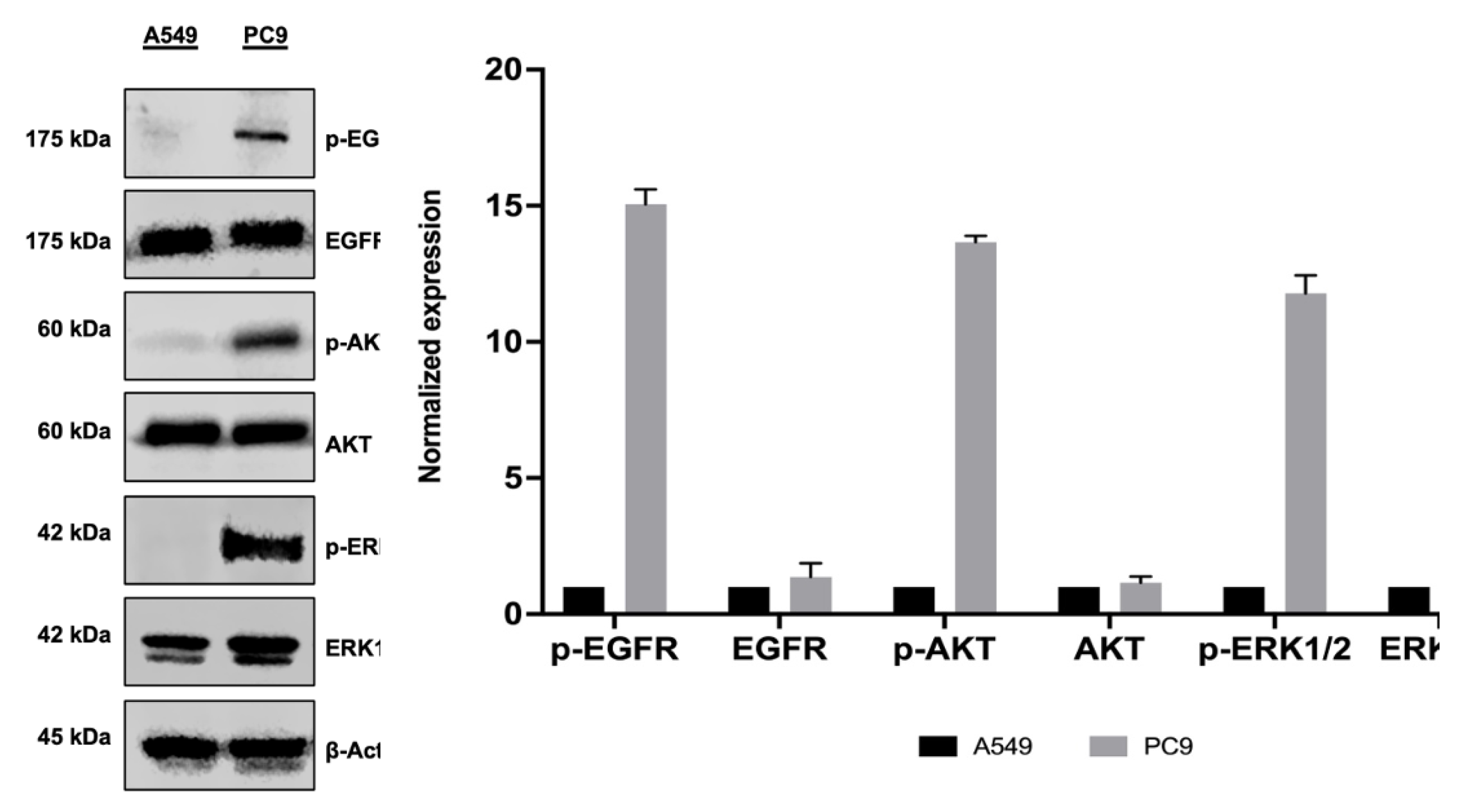

In this study, we used two human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines: PC9 and A549. Both adherent growing cell lines display epithelial morphology, but while PC9 cells harbor an EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation, A549 harbor wild type EGFR. PC9 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. A549 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% FCS and 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. Both cell lines were kept at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Subculturing was performed when cells reached 80-90% confluency using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA to detach the cells, ensuring their continuous proliferation and viability.

2.2. Isolation of EVs

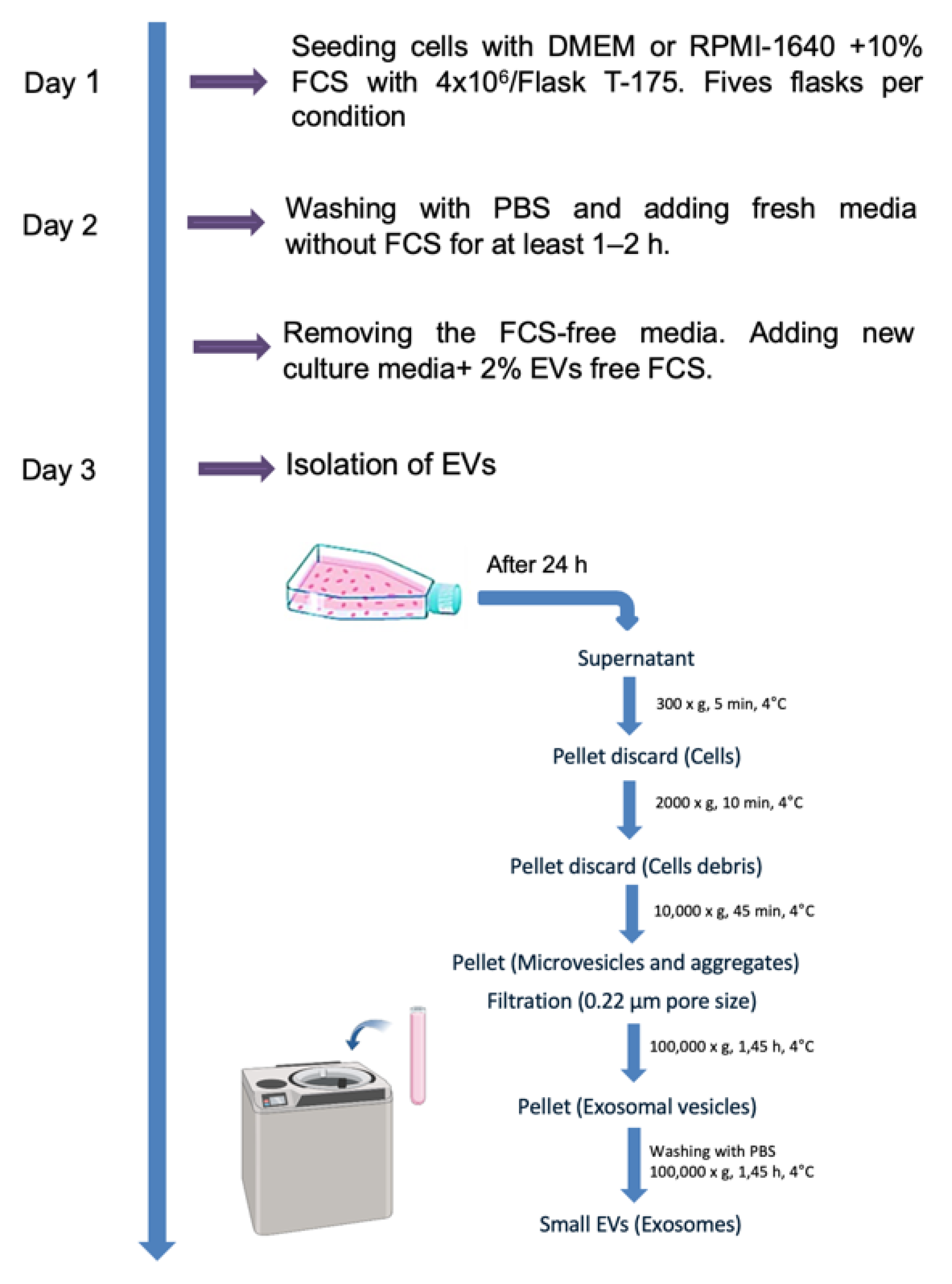

For isolation of EVs, five T-175 flasks with 4x106 cells each were seeded for each experiment and cell line to obtain sufficient number of EVs. When the cells reached 90% confluency, they were washed twice with PBS and incubated for 24 hours with medium containing 2% EV-depleted FCS. Conditioned media (CCM) was collected from both lung cancer cell lines and EVs were isolated using differential (ultra)centrifugation as previously described, with slight modifications [

23]. Briefly, as shown in (

Figure 1), 20 mL of serum free conditioned media from each flask was subjected to centrifugation at 300 ×g for 5 minutes, 2,000 ×g for 10 minutes, and 10,000 ×g for 45 minutes at 4 °C in order to completely eliminate cellular debris and large vesicles. Subsequently, the resulting supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 μm polyethersulfone filter (Nalgene, Rochester, NY) to eliminate particles exceeding a diameter of 220 nm. To isolate small EVs from the pre-cleared CCM, the filtered supernatant was transferred into ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) and subjected to high-speed ultracentrifugation at a force of 100,000 xg for a duration of 1:45 hour at 4 °C (Optima XPN-100, Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) using a SW32 Ti Swinging Bucket rotor. The resulting EV-enriched pellet was reconstituted in 30 mL of cold PBS, then subjected to another round of ultracentrifugation at 100,000 xg for an additional 1:45 hour at 4 °C. The final pellets, containing EVs, were resuspended in 100 µl of PBS and stored at -80 °C for later use.

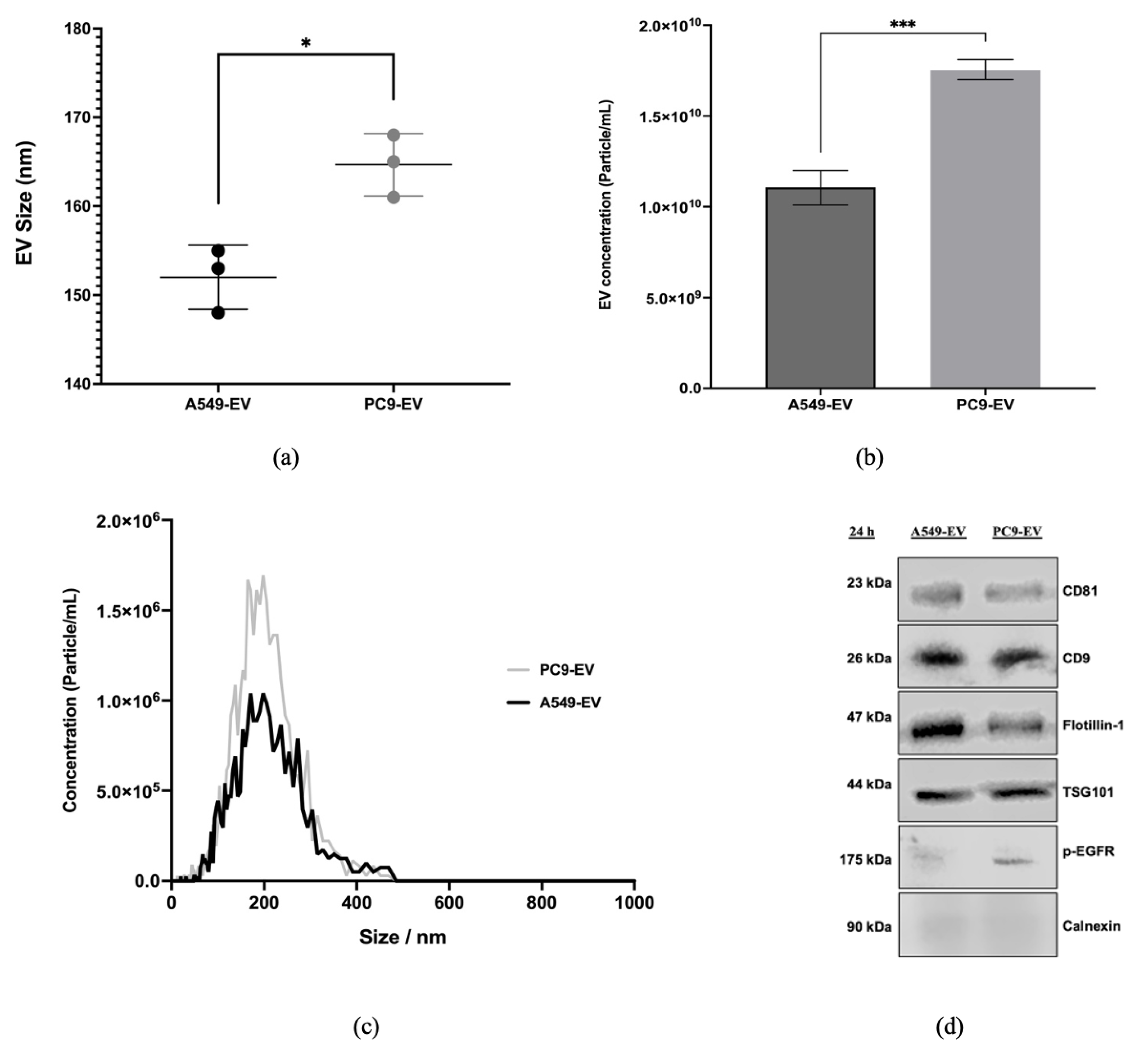

The protein concentrations of the EV preparations were determined with a BCA kit (Pierce). The size distribution of EVs was measured by ZetaView nanoparticle tracking analysis (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, Germany). Expression levels of representative EV-related markers CD9, CD81, TSG101 and Flotillin-1 were detected by Western blot.

Figure 1.

Isolation of EVs by Ultracentrifugation. The isolation of EVs by ultracentrifugation involves several key steps. First, cell culture supernatant is collected and subjected to a series of centrifugation steps to remove cellular debris and large particles. Next, the clarified supernatant undergoes ultracentrifugation at high speeds, to pellet EVs. The pellet containing EVs is then carefully resuspended and washed with buffer to further remove contaminants. Finally, the isolated EVs can be resuspended in an appropriate buffer or media without FCS for downstream analyses, such as characterization or functional studies.

Figure 1.

Isolation of EVs by Ultracentrifugation. The isolation of EVs by ultracentrifugation involves several key steps. First, cell culture supernatant is collected and subjected to a series of centrifugation steps to remove cellular debris and large particles. Next, the clarified supernatant undergoes ultracentrifugation at high speeds, to pellet EVs. The pellet containing EVs is then carefully resuspended and washed with buffer to further remove contaminants. Finally, the isolated EVs can be resuspended in an appropriate buffer or media without FCS for downstream analyses, such as characterization or functional studies.

2.3. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

Nanoparticle tracking analysis quantified the size distribution and concentration of the EVs as reported previously. [

24] Briefly, EV samples were diluted in HBSS buffer to final volume of 1 mL (dilution range: 1:50–1:2000). The optimal measurement concentrations were determined by testing the particle count per frame within the range of 140 to 200 particles per frame. The manufacturer’s default software settings were used for EVs. Two cycles were conducted for each measurement, involving the scanning of 11 cell positions and capturing 30 frames per position. The measurements were performed under the specified settings. Focus: Autofocus; Camera sensitivity for all samples: 79; Shutter speed: 70; Scattering intensity: Automatically detected; Cell temperature: 24 °C. Following capture, the videos were subjected to specific analysis parameters using the built-in ZetaView Software 8.05.11 SP1: Minimum area: 5, minimum brightness: 30, maximum area: 1000. Hardware: CMOS camera; 40 mW embedded laser at 488 nm.

2.4. Western Blotting

PC9 and A549 were lysed with 1x RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease and phosphatase cocktail inhibitor). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The protein concentrations of the supernatant were then estimated using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Cat#: 23227). The EVs isolated from PC9 and A549 CCM were lysed with 1x RIPA buffer. Then equal volumes of protein (20 μg for EVs and 10 μg for cell lysates) for each sample were prepared and separated by 8-12% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane or 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Sigma-Aldrich, Massachusetts, USA, GE10600003). Subsequently, the membrane was washed with TBS four times for 5 minutes each at room temperature and stained with Ponceau S to visualize the protein bands followed by blocking with 5% BSA in TBS-T for an hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. After being rinsed four times for five minutes each time with TBS buffer, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies of interest (

Table 1) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed again four times for five minutes with TBS-T, and HRP-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG were added for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were again washed four times and protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (GE Healthcare Life Science) and analyzed using an Odyssey Fc Imager (LI-COR Biosciences).

2.5. miRNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

For RNA extraction, samples were transferred to RNase-free tubes and total RNA, including miRNA, from EV and cells was extracted utilizing the QIAGEN miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed to assess the concentration and purity of the eluted RNA. cDNA synthesis was performed by reverse-transcribing 5 ng of RNA using miRURY LNART kit miRNA PCR assays (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed by using a QuantStudio 5 Machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with miRCURY LNA SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The PCR reactions were carried out in duplicates with 60 cycles of denaturation (10s at 95 °C) Annealing (60s at 56 °C) and Elongation (30s at 54 °C) after an initial enzyme activation (2 min at 95 °C).

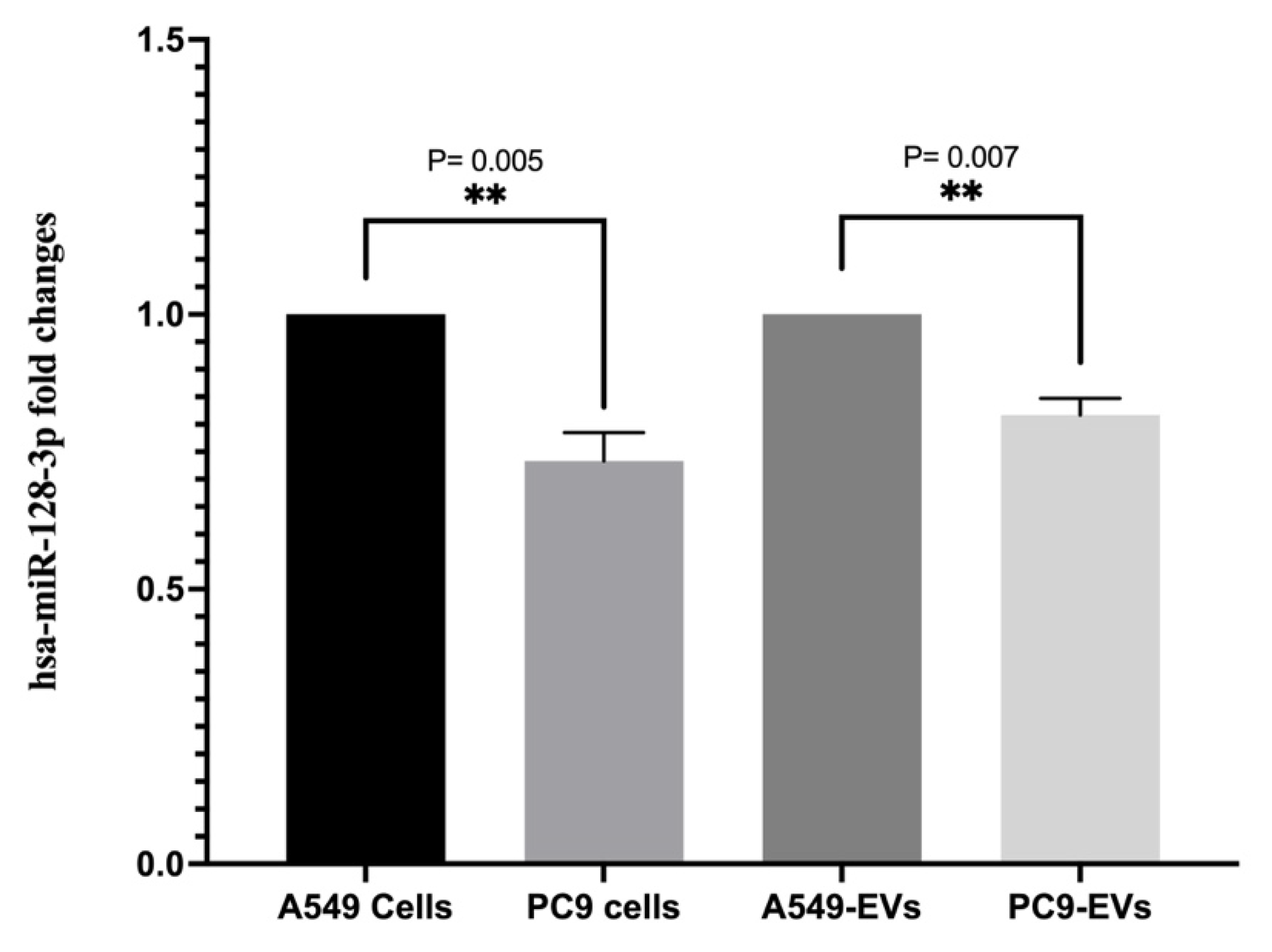

Previous studies reported that EGFR signaling is regulated by hsa-miR-128-3p in NSCLS harboring EGFR mutation [

20]. Depending on this, the EV hsa-miR-128-3p (5’UCACAGUGAACCGGUCUCUUU) expression levels were evaluated with triplicate experiments and hsa-miR-103a-3p (5’AGCAGCAUUGUACAGGGCUAUGA) served as an endogenous control. The miRNA expression levels in EV from A549 treated with EGF were compared with the untreated control. The expression levels of the target miRNA were normalized to the hsa-miR-103a-3p and the calculation was performed using the comparative 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.6. The miRNA Target Prediction

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The software SPSS V22.0 (IBM, USA) was used for all statistical analyses, and GraphPad Prism10.1.2. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for producing the graphs. One-way ANOVA Student’s t-test was used to analyze the differences’ statistical significance. The threshold of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

The EGFR signaling pathway is well documented for its pivotal involvement in various cellular processes. EGFR mutations are present in 10-20% of Caucasian and 50% of Asian NSCL patients, leading to constitutive activation of downstream pathways. This dysregulation leads to poor prognosis and resistance to therapy [

2]. However, its role in regulating EVs is not clear. The present study aimed to better understand how constitutive activation of EGFR influences the release of EVs and their miRNA cargo composition, which could offer insight into tumor progression and potential therapeutic targets.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding intercellular communication facilitated by EVs. These are the carriers that transport various types of proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and signaling molecules. Among these vesicles, small EVs (exosomes) and large EVs (microvesicles) have attracted a lot of attention because they are found in biological fluids and can facilitate intercellular communication and initiate signaling cascades [

26].

Our findings demonstrated that EGFR mutations affects EV secretion in lung cancer cells. Specifically, the PC9 cell line harboring mutant EGFR showed a significant increase in EV concentration compared to A549 harboring wild type EGFR, suggesting that EGFR signaling positively regulates EVs secretion. These results are consistent with previous studies that suggested EGFR signaling may affect EV biogenesis and release. Montermini et al. [

27] detected pEGFR and several other tyrosine kinases in EVs purified from the plasma of tumor-bearing mice and from the conditioned media of cultured cancer cells. He also showed that inhibition of oncogenic EGFR with the second generation of TKI, including CI-1033 and PF-00299804, triggers the release of exosome-like extracellular vesicles and affects the level of their phosphoprotein and DNA content.

In contrast, another study by Zhou et al. [

28] showed that during wound healing in BUMPT cells, cells treated with EGF to activate EGFR signaling, led to a decrease in exosome production accompanied by a promotion of wound healing. Conversely, inhibition of EGFR by gefitinib increases exosome production, accompanied by inhibition of wound healing. This decrease in EV release upon EGFR activation may be due to the process of EGFR ubiquitination, in which activated EGFR undergo rapid Clathrin-mediated endocytosis and are recognized by the ESCRT complexes, where the lysosomally targeted receptors, such as activated EGFR, are sorted onto the ILVs of MVBs for subsequent lysosomal degradation or undergo recycling by being retained on the limiting membrane of the MVB and returned to the plasma membrane and released as exosomes [

29,

30].

In our study, nanoparticle tracking analysis revealed that the size of EVs derived from both cell lines ranged between 30 and 200 nm, confirming successful EV isolation. It also showed that mutated EGFR cells produced EVs that were bigger in size compared to EVs derived from wild type EGFR cells. This size increase could be due to alterations in the cellular machinery involved in EV biogenesis, influenced by EGFR signaling. However, the presence of EV-specific proteins such as CD9, CD81, TSG101, and Flotillin-1 in the isolated EVs from both cell lines confirmed their identity and the successful isolation process. These proteins are well-established markers for EVs and are commonly used to validate their presence and purity [

31]. In addition to classical EV markers, immunoblotting shows that EVs released by mutated EGFR cell line PC9 but not wild type EGFR cell line A549 carry pEGFR, indicating that the phosphorylated form of EGFR is successfully packaged into EVs.

Many researches have demonstrated the association between EVs and miRNA dysregulation in cancer [

32]. The significance of microRNAs in lung cancer has been highlighted by Bai et al. [

25], who established how oncogenic signaling pathways like EGFR can change the expression of these molecules. Results in our labs and other previously published data demonstrated that several tumor suppressors miRNA are downregulated in lung cancer cells harboring EGFR mutations. Interestingly, our present study also found the downregulation of hsa-miR-128-3p in PC9 cells and EVs derived from this lung cancer cells. The involvement of this specific microRNA in the pathogenesis of lung cancer has been suggested previously [

20], while its decrease in EVs indicates a possible mechanism by which EGFR signaling modulates tumor behavior. However, downregulation of EVs hsa-miR-128-3p may influence the tumor microenvironment by altering gene expression in recipient cells treated with EVs, thereby promoting tumor progression and metastasis.

Our findings from this study contribute to the growing body of evidence that EVs have a significant impact on cancer biology, specifically in relation to EGFR signaling.

Previous studies have proven that EVs can carry oncogenic proteins, RNA, and other bioactive molecules, facilitating communication within the tumor microenvironment and promoting metastatic processes [

26]. However, Lin et al. [

33] demonstrated that EVs derived from EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells increased the sensitivity of recipient cells to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib. This suggests that these EVs may play a role in modulating drug response by enhancing the efficacy of targeted therapies in EGFR-mutant NSCLC

The differential expression of EVs-associated microRNAs, such as hsa-miR-128-3p, indicates that EVs have the potential to be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. Exosomal microRNAs have been suggested as non-invasive biomarkers due to their stability in body fluids and their ability to reflect the molecular state of the cell of origin [

3]. Therefore, the downregulation of hsa-miR-128-3p in EVs isolated from EGFR-mutant cells and EGFR-mutant NSCLS patients could serve as a diagnostic marker for EGFR constitutive activation in lung cancer.

However, the study also raises several questions that need further investigation. We still need to fully elucidate the exact mechanism by which EGFR signaling modulates EV biogenesis and specific cargo selection. Understanding these mechanisms could provide insights into the development of targeted therapies that disrupt EV-mediated communication in the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, we need to explore in more detail the functional implications of altered EV composition on recipient cells and their role in tumor progression.