1. Introduction

Cancer remains a significant public health challenge in the 21st century, with the World Health Organization (WHO) reporting that cancer causes the death of approximately one in twelve women and one in nine men globally [

1]. Lung cancer, primarily categorized into small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-small lung carcinoma (NSCLC), was the most prevalent malignancy in 2022, accounting for a substantial portion of cancer-related deaths globally [

2,

3]. Despite recent advancements in understanding the molecular underpinnings of lung cancer and the development of targeted therapies, there is still an urgent need to further elucidate the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the complex systemic networks involved in intercellular communication [

4].

Exosomes are small, nano-sized membrane vesicles secreted by almost all living cells, found in various human biofluids, including blood, saliva, and urine. Cancer cells secrete exosomes in greater quantities than normal cells, participating in a well-orchestrated intracellular communication system. Tumor progression strongly depends on neoangiogenesis to support tumor growth, with exosomal cargo affecting multiple signaling pathways, including MAPK, YAP, and VEGF, that regulate angiogenesis [

5]. Additionally, exosomes derived from primary tumors can also convey systemic signals that prepare metastatic sites [

6]. Besides, tumor cell-derived exosomes can induce the differentiation of normal stromal fibroblasts towards cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which are crucial for supporting and maintaining tumor development [

7]. In this dynamic interplay, CAFs secrete extracellular vesicles that promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), proliferation, invasion and migration abilities of tumor cells, aligning with cancer hallmarks [

8].

The complexity associated with the molecular cargo of tumor-derived exosomes necessitates the integration of multi-omics high-throughput technologies to identify diverse molecules enriched in exosomes and to apply advanced bioinformatics approaches for discerning molecular targets and their intermolecular interactions involved in tumor angiogenesis, growth, migration and invasion. Recent advancements towards standardizing exosome isolation methodologies and breakthroughs in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies for high-throughput detection and quantification facilitate the identification of exosome-based molecules as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for several tumor types, including NSCLC [

9]. Previous studies have shown that the exosomal proteome and miRNAome derived from blood liquid biopsies of lung cancer patients can efficiently discriminate them from healthy individuals [

10,

11,

12]. Notably, some exosomal proteins or miRNAs suggest promise as potential biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and anti-tumor drug-resistance and immunotherapy-response prediction [

11,

13,

14,

15]. Before testing clinical samples, the isolation of exosomes from in vitro cell cultures of well-established tumorigenic cell lines, combined with comprehensive molecular cargo characterization and the integration of proteogenomics and in-depth bioinformatics approaches, can lay the foundation for decoding the complex exosomal cargo interactome and elucidating the role of cancer-related exosomes in tumor pathogenesis, progression, migration, invasion, and metastasis.

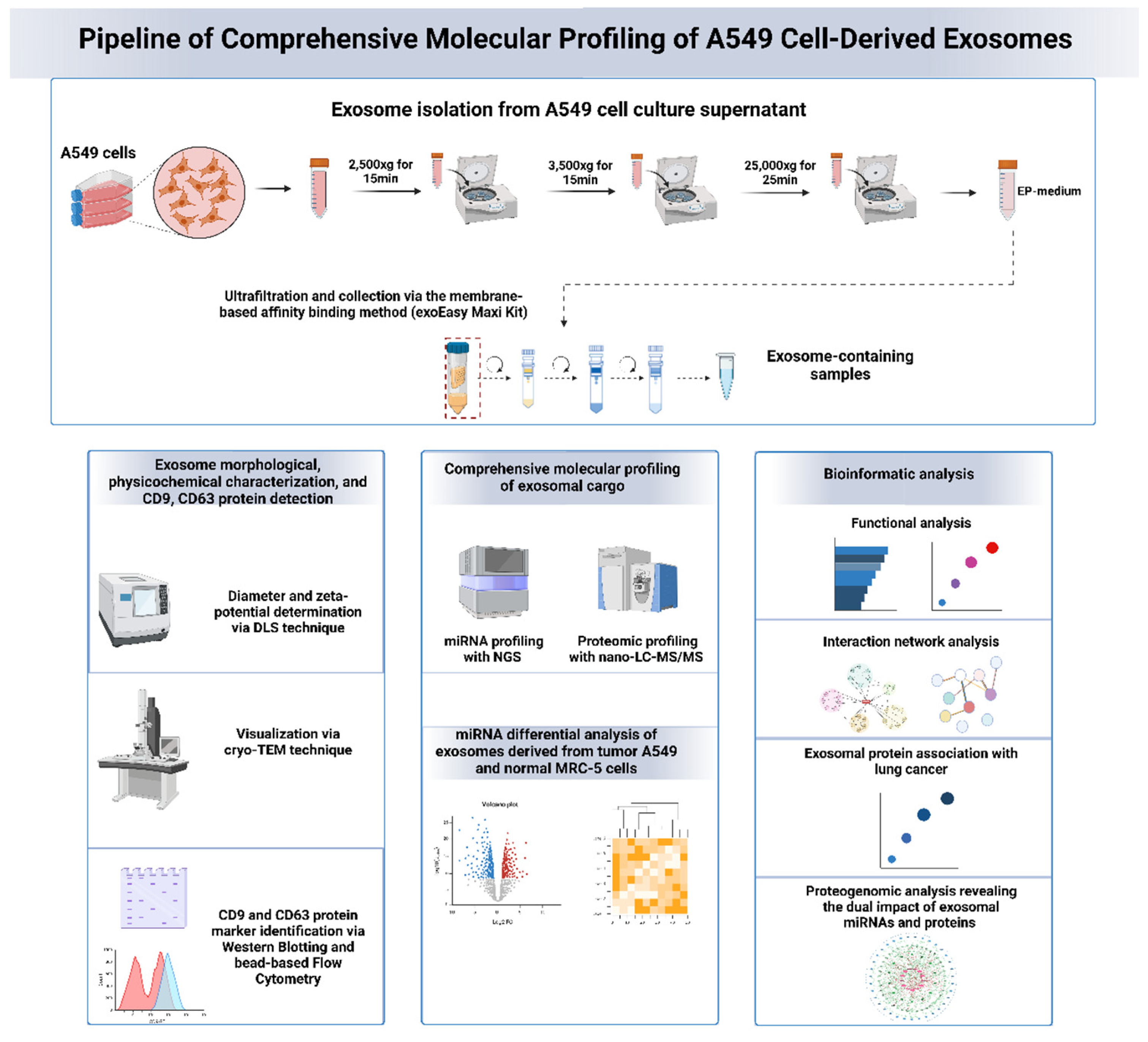

In this study, we isolated exosomes from the lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell line using a previously established protocol, followed by detailed characterization of their physicochemical and morphological properties using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM). Common exosomal protein markers, such as CD9 and CD63, were identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes through Western Blotting and Flow Cytometry. The isolated exosomes underwent global proteomic and microRNA profiling using NGS-based and nano-LC Mass Spectrometry-based high-throughput methodologies, accompanied by functional bioinformatics analysis to identify cellular compartments, biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways associated with the exosomal cargo. Protein-protein interaction networks were also constructed to identify subnetworks of key proteins that interact with multiple proteins, potentially playing a dominant regulatory role in the exosomal protein interactome.

Following a proteogenomic approach, the target genes of the identified exosomal miRNAs and the protein interactors of the identified exosomal proteins were integrated in complex networks to decipher the exosomal interactome and identify potentially dually affected genes (DAGs) in the potential exosome-recipient cells, potentially deregulated through synergistic or antagonistic interactions. A differential expression and secretion analysis of exosomal miRNAs from A549 cells compared to normal lung MRC-5 cells was performed to identify the upregulated miRNAs in A549 cell-derived exosomes, serving as foundation for future biomarker-based clinical studies.

Overall, this study integrates high-throughput discovery data from well-characterized lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell-derived exosomes with novel bioinformatics approaches to elucidate the exosome interactome and the cellular mechanisms impacted by tumorigenic exosomes. We also propose candidate exosomal protein and miRNA biomarkers with strong association with lung cancer tumorigenicity with potential translatability towards further clinical testing in lung adenocarcinoma patient diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular profiling pipeline used for the analysis of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell-derived exosomes. The pipeline includes exosome isolation, characterization (physicochemical and morphological properties), followed by proteomic profiling and miRNA sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis was performed to identify the differentially expressed miRNAs in cancerous A549 cell-derived exosomes compared to normal MRC-5 cells. Functional enrichment and exosome molecular interactome analysis were conducted to explore the effects of exosomal cargo and identify exosomal key regulatory molecules involved in lung cancer progression. Proteogenomic network analysis was also performed to determine key molecules (genes and proteins) that are dually regulated by exosomal miRNAs and proteins through extensive interactions.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular profiling pipeline used for the analysis of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell-derived exosomes. The pipeline includes exosome isolation, characterization (physicochemical and morphological properties), followed by proteomic profiling and miRNA sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis was performed to identify the differentially expressed miRNAs in cancerous A549 cell-derived exosomes compared to normal MRC-5 cells. Functional enrichment and exosome molecular interactome analysis were conducted to explore the effects of exosomal cargo and identify exosomal key regulatory molecules involved in lung cancer progression. Proteogenomic network analysis was also performed to determine key molecules (genes and proteins) that are dually regulated by exosomal miRNAs and proteins through extensive interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culturing

The human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial A549 (RRID: CVCL_0023) and the human normal fetal lung fibroblasts MRC-5 (RRID: CVCL_0440) cell lines were used for the in vitro assays as exosome-donor cells. These cell lines are routinely maintained and handled in our laboratory following established cell culturing guidelines [

16,

17]. Specifically, the cells were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were examined morphologically daily for possible contaminations and sub-cultured every 2-3 days at a confluency of approximately 70%. For all the biological assays, including the exosome isolation experiments, only cells with low passage (<15) number were used to ensure their closer resemblance to the original cells and avoid senescence-induced molecular alterations or phenotypic or genotypic changes linked to passage number variations.

2.2. Exosome Isolation via Modified Protocol

The exosomes were isolated from the cell culture medium, combining successive low-speed centrifugation steps with sequential ultrafiltration and membrane-based affinity binding [exoEasy Maxi kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands)], as reported elsewhere [

18]. Particularly, 1.5X106 cells were seeded in 100 mm Nunc™ EasYDish™ cell culture dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) bearing 56.7 cm2 surface area. After 24 hours, the cell growth medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS 1X, pH 7.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by the addition of cell growth Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum (exosome-depleted FBS, Capricorn Scientific GmbH, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA). The exosome-depleted FBS was selected to ensure the absence of any “contaminating” FBS-associated vesicles that could lead to misleading exosome characterization and profiling data. After 24 hours and at cell confluency of approximately 70-80%, the cell culture supernatants were collected and subjected to differential low-speed centrifugation steps (2,500xg for 15min, 3,500xg for 15min, 25,000xg for 25min) to efficiently remove viable cells, dead cells, cell debris as well as the apoptotic bodies and microvesicles as a pellet (EP-medium generation). The supernatant was collected and subjected to sequential ultrafiltration steps using 50kDa MWCO Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). After each ultrafiltration step, the concentrated exosome-containing sample was resuspended with PBS 1X, pH 7.4 inside the filter unit and then collected. The concentrated exosome-containing samples were then combined into a single suspension, followed by exosome collection via the membrane-based affinity binding method (exoEasy Maxi Kit), following the guidelines of the kit. The purified exosome containing samples were either directly proceeded to physicochemical analysis or stored to -80°C for downstream assays.

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis of Exosomes

The physicochemical analysis of the exosomal samples were conducted via assessing the size distribution, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of the purified exosomes immediately after isolation using the Malvern Instrument Nano ZetaSizer. The instrument features a 4mW He-Ne laser operating at a wavelength of 633nm and its detector for the scattered light was set at a fixed angle of 175° from the incident laser beam. For the assessment of size distribution and zeta potential, the exosomal suspension was further diluted 1:20 with PBS 1X, pH 7.4 and analyzed at a stable temperature of 25°C. During the size distribution analysis, the DLS instrument measures the Brownian motion of the particles and determines their size using the Stokes-Einstein equation. The polydispersity index (PDI), which indicates the sample heterogeneity, is calculated using the formula PDI=(σ/d)², where σ represents the standard deviation of the size distribution, and d is the average particle diameter. The zeta potential is derived by measuring particle velocity using Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LVD), which reveals its Electrophoretic Mobility. The Electrophoretic Mobility, using the Henry Equation, provides the zeta potential of the sample.

2.4. Morphological Analysis of Exosomes via Cryo-TEM

The exosomal samples were freeze-dried and prepared for cryo-TEM analysis using a controlled environment vitrification system (CEVS). A small sample volume (5-10 μL) was applied to a carbon film supported by a copper grid and then blotted with filter paper to create a thin liquid layer on the grid. The grid was rapidly frozen in liquid ethane at −180°C and then transferred to liquid nitrogen (−196°C). The exosomal samples were examined using a TEM microscope (Philips CM120 BioTWIN Cryo) equipped with a post-column energy filter (GATAN GIF 100) and an Oxford CT3500 cryo-holder with its workstation. The temperature during analysis was kept at −180°C, and the acceleration voltage was set to 120kV. Images were captured with a CCD camera (Gatan 791) at approximately 1μm defocus while maintaining low-dose conditions.

2.5. CD9 and CD63 Exosomal Markers Identification with Western Blot and Flow Cytometry Analysis

For the detection of CD9 and CD63 exosomal proteins via Western Blot, whole cell lysate and exosomal protein content at equal quantity (30μg of total protein) were analyzed. Briefly, the whole cell lysate was prepared by A549 cell trypsinization and washing with ice-cold PBS 1X, pH 7.5. The cells were then incubated for 30 min in RIPA 1x lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) containing PMSF Protease Inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) on ice. A centrifugation step at 14.000g for 10 min was performed and the supernatant was collected. To prepare the exosome lysate, A549 cell-derived exosomes were incubated with 1X RIPA buffer supplemented with PMSF protease inhibitors for 10 minutes on ice. The protein content of exosomes and whole cell lysate was quantified using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The protein samples were denaturated at 95◦C for 10 min in Laemmli Lysis-buffer (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and were further separated by electrophoresis in a 15% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to PVDF Western Blotting Membranes (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and the bocking of immunoblots was performed with 1 X PBST (0.1% Tween 20) supplemented with 5% skim milk. The immunoblots were then incubated with the appropriate primary monoclonal antibody against CD9 or CD63 exosomal marker (1:5000 dilution of CD9/60232-1-Ig and CD63/67605-1-lg Monoclonal antibodies, Proteintech Group, Rosemont, USA) overnight at RT. The same procedure was also performed for the primary antibody against the β-actin monoclonal antibody (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA). The next day, the membranes were washed 3 times with 1X PBST (0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with the secondary anti-mouse antibody m-IgG Fc BP-HRP (sc-525409, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA) for 1h at room RT. Following three additional washing steps, protein bands were visualized using the chemiluminescence Immobilon ECL Ultra Western HRP Substrate (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and a gel imaging system captured images.

CD9 and CD63 protein markers were also detected with Flow Cytometry using superparamagnetic capture beads conjugated with anti-CD63 antibodies (Abcam Inc, Toronto, ON, Canada). To ensure efficient binding of exosomes on the surface of the capture beads, the XE buffer, used for exosome collection during the final isolation step, was replaced with 1X PBS utilizing the 50kDa MWCO Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Then, 10μg of purified A549 cell-derived exosomes were incubated overnight at room temperature with 50 μL anti-CD63 capture beads, following the manufacturer's instructions. The next day, the samples were incubated for 60 minutes at 4°C with PE-conjugated anti-CD9 antibody [VJ1/20]. Following multiple washing steps with 1X Assay Buffer, the purified beads conjugated with CD63+ exosomes with either CD9 presence or not were incubated with PE-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-CD9 antibody. The final product was collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1X Assay Buffer for flow cytometry analysis.

2.6. Proteomic Profiling of Exosomal proteins via Nano-LC-MS/MS

Exosomes isolated via the modified protocol were freeze-dried for 24h. The exosome-containing powder was dissolved in 50 μL of lysis buffer (4% w/w SDS, 0.1 M Tris-HCL, 0.1 M dithioerythritol (DTE) pH = 7.6) and then, probe sonication was performed to the samples following 3 cycles of 38% amplitude and 12sec on/off. The lysis of the samples was performed on the bench for 45min. After the solubilization of the samples, a centrifugation step at 13,000rpm for 10min was performed so that the remaining debris was discarded. According to Bradford assay, 200-500μg of proteins per sample were placed in the filter unit of the Amicon Ultra 0.5 Centrifugal Filter Device (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with 0.1 M DTE in 8 M urea solution and a centrifugation step was performed at 13,000rpm for 30min. Then, 0.05 M of iodoacetamide in 8M urea and 0.1 M Tris-HCL pH = 8.5 were added to the samples and the total reaction was incubated for 20min at RT in the dark for the reduction and the alkylation of the samples. For the digestion of the samples, a tryptic solution (500μM) was added for an overnight incubation, with a final trypsin-to-protein ratio of 1:100. The peptide flow-through was freeze-dried, and afterwards, the lyophilized peptide powder was resuspended in 75 μL of HPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA) phase A (99.9% water with 0.1% formic acid (v/v)). The final peptide mixture was purified utilizing a Millex® syringe-driven filter (Merk KGaA, Athens, Greece) unit and was then analyzed with nano LC-MS/MS. The separation of the peptides was accomplished by a reversed-phase analytical C-18 column (75 μm x 50 cm; 100 Å, 2-μm-bead-packed Acclaim PepMap RSLC, Thermo Scientific) and by using an Ultimate-3000 system (Dionex, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) interfaced to an LTQ-Velos Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, 6 μL of peptide mixture were loaded on a C-18 pre-column at a constant flow rate of 5 L/min in phase A. The elution time lasted 180 min and had a gradient of 2–35% phase B (99.9% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) at 300 nL/min flow rate. An Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer fitted with a nanospray source was used to collect the mass spectra. A data-dependent acquisition mode with the XCaliburTM v.2.2 SP1.48 (Themo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) software was selected for the instrument. Full scan data were acquired at a resolving power of 60,000, with a maximum integration time of 100 ms. The 20 most intense ions per survey scan were analyzed with the data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry performing higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation in the Orbitrap at a resolving power of 15,000 and a collision energy of 36 NSE%. MS/MS spectra were acquired at a resolving power of 15,000, with a maximum integration time of 120 ms. Measurements were performed using m/z 445.120025 as lock mass. To minimize the repetitive selection of the same peptide, Dynamic exclusion settings were implemented with a repeat duration of 30sec.

2.7. MS/MS Data Processing, Protein Abundance Estimation and Bioinformatics Analysis of Proteomic Data

MS/MS data were analyzed with the Proteome Discoverer (version 1.4.0.388, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The SEQUEST engine against Homo sapiens protein reference database of Uniprot (

https://www.uniprot.org/, accessed on 06/2022) was selected for the analysis of MS2 spectra and the following Proteome Discoverer parameters were chosen: two maximum missed cleavage points for trypsin; oxidation of methionine as a variable modification; 10 ppm peptide mass tolerance; and 0.05 ppm fragment ion tolerance. A percolator based on q-values at a 0.01% false discovery rate (FDR) validated the peptide spectral matches, and extra peptide filtering was accomplished with an Xcorr versus peptide charge values (percolator maximum Delta Cn was set at 0.05). The doubly- and triply-charged peptides were analyzed with values of 2.2 and 3.5, respectively. Only peptides with a minimum length of 6 amino acids were accepted.

The corresponding gene identifiers of the proteins isolated from A549 cell-derived exosomes were retrieved by Uniprot’s Retrieve/ID mapping tool (

https://www.uniprot.org/id-mapping). To maintain stricter criteria and more robust information on the proteomic data, only the 68 unique proteins identified in at least 2 biological replicates, out of the 252 unique proteins identified in all 3 biological replicates, were used for the downstream bioinformatic analysis.

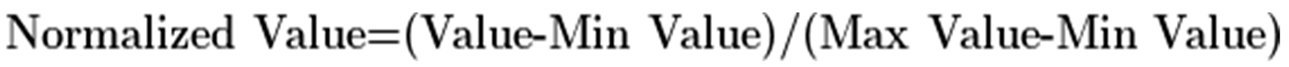

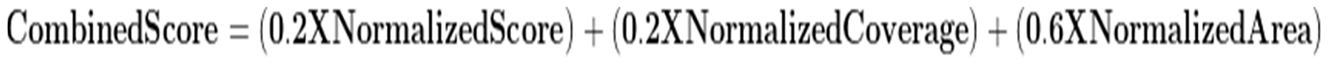

To determine the relative abundance of each protein with high confidence across the different identified proteins in exosomes, a multi-criteria ranking approach was applied, combining the parameters of Score (confidence of the protein identification), Coverage (percentage of the protein sequence covered by the identified peptides) and Area (integrated peak area of the peptide ion signals). A fixed weight of 0.6 was applied to the metric of Area since this parameter is the most important to estimate the protein relative abundance. The Coverage and Score metrics were assigned with a fixed weight of 0.2. Initially, the values of Area, Score and Coverage of each protein were normalized to a range between 0 and 1 following this formula:

Where

Normalized Value is the Score, Coverage and Area values of each protein after applying normalization,

Value is the Score, Coverage or Area value of each protein,

Min Value and

Max Value are the minimum and maximum values of all the proteins of the dataset considering the parameters of Score, Coverage or Area.

Considering the assigned weights to each metric, the Combined Score of each protein identified in at least 2 of 3 samples was estimated following this formula:

Where

NormalizedScore, NormalizedCoverage and

NormalizedArea are the Score, Coverage or Area of each protein normalized to a range between 0 and 1, and CombinedScore is the final score assigned to each identified protein based on the multi-criteria ranking approach.

The Venn diagram was constructed utilizing the FunRich tool to present the overlaps of the protein identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes with the total exosomal proteomic data registered in Vesiclepedia database [

19,

20]. In addition, FunRich tool was used to present the different subcellular locations of the identified proteins according to the cellular compartment in terms of the percentage of proteins found in each compartment with a threshold at log10(p-values)>2 to focus on significantly enriched categories. To identify associations between the identified proteins and those relevant to lung cancer biomarkers, text-mining approaches were applied using DisGeNET with 'lung cancer' as the search term, followed by filtering for biomarker relevance [

21]. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment as per molecular functions, biological processes and cellular components, as well as Reactome pathway analysis, were conducted via the clusterProfiler and Reactome PA packages, respectively, in R [

22,

23]. The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of the identified proteins was constructed via the STRING database (v11.5), according to the following settings: (a) the minimum interaction score at high confidence (0.7); (b) the max number of interactors shown for the first shell no more than ten; and (c) the max number of interactors shown for the second shell no more than five.

2.8. Total MicroRNA Profiling of Exosomes Using NGS

The total exosomal miRNAs were isolated using the RLT Buffer and the miRNeasy (Qiagen, Limburg, NL) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with slight modifications. Briefly, RLT reagent was added to 0.4ml of isolated exosomes at a final concentration of 3:1 v/v, as described elsewhere [

24,

25]. All samples were homogenized by vortexing for 1min and incubated for 5 min at RT. Then, 0.4ml of chloroform was added to each sample (1:1 v/v chloroform to the starting volume of each sample), and the samples were shaken vigorously for 15 sec and incubated for 3 min at RT. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000xg for 15 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase was incubated with 1.5 volumes of 100% ethanol, and the mixture was loaded onto RNeasy mini columns. The column washing steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Small RNA-Seq analysis was performed with the NEBNext® Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina® (NEB, USA). Qubit High Sensitivity DNA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the assessment of the small RNA-seq libraries, and the quality control of the libraries was employed with the Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 kit (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The libraries were combined in equimolar concentrations, and sequencing was carried out by the Illumina NextSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), generating approximately 20 million single-end reads per sample, with each read measuring 50 bp in length.

2.9. MicroRNA Data Processing and Bioinformatic Analysis

The generated raw sequence reads (20-51nt length) from the three small RNA-Seq libraries underwent preprocessing to eliminate adapter sequences using Trim Galore! (Galaxy Version 0.6.7+galaxy0). To enhance the reliability of the analysis, the reads with a base call quality lower than Q25 were excluded and the quality of the remaining reads was evaluated with FastQC (version 0.12.1). Sequences longer than 17 nucleotides following trimming were preserved, while duplicate reads were collapsed using the miRDeep2 Mapper tool (Galaxy Version 2.0.0). The resulting collapsed reads from all samples were mapped to human mature and precursor sequences obtained from miRBase, and the miRDeep2 Quantifier tool (Galaxy Version 2.0.0) was utilized for quantitative expression analysis [

26,

27]. To enhance the robustness of the analysis, only the miRNAs identified consistently across all three biological replicates were used for further analysis in R. Subcellular localization of the identified miRNAs was conducted with the RNALocate v.2.0 database and functional analysis of the identified miRNAs was conducted using the miRNA Enrichment Analysis and Annotation Tool (miEAA) [

26,

27]. Accordingly, Gene Ontology (GO), Disease Ontology (DO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed using miRPathDB, miRWalk, and KEGG databases, respectively [

28,

29,

30].

Differential expression analysis of miRNAs identified in cancerous A549 cell-derived exosomes compared to normal MRC-5 cell-derived exosomes was conducted using the DESeq2 bioinformatic tool. Differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs were determined based on a log2 fold change (FC) > 1 or < -1 and an adjusted p-value < 0.05, using the Wald test for hypothesis testing in DESeq2.

2.10. Proteogenomics-Based Bioinformatics analysis

To conduct a comprehensive analysis of the biological cargo involved in A549 cell-derived exosomes, a proteogenomic-based bioinformatic analysis was performed, leveraging data from both genomics and proteomics to enhance the interpretation of molecular mechanisms. Briefly, the target genes of top 20 enriched miRNAs in A549 cells-derived exosomes were retrieved from the miRTarBase [

31], the TarBase[

32] and miRecords[

33] databases using the multiMiR package in R [

34]. For enhanced accuracy, the results were further filtered to include only miRNA-gene interactions experimentally validated through methods such as reporter gene assays (e.g., luciferase assays), immunoblotting/western blotting, and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Accordingly, the protein interactors of the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes were retrieved by STRING database (v11.5). The circular network of miRNAs, the miRNA target-genes and the exosomal proteins was constructed using Cytoscape (v3.10.1).

4. Discussion

Exosomes derived from malignant cells obtain their oncogenic properties and transmit molecular signals to nearby or distant recipient cells. This process facilitates the neoplastic transformation of normal cells or induces the metastatic potential of tumorigenic cells with initially low migration capacity [

43,

44]. Advancements in high-throughput next-generation methodologies allow for comprehensive proteomic and miRNA profiling of exosomes, providing an in-depth molecular mapping of their cargo and also facilitating the development of diagnostic panels for tumor diagnosis and monitoring [

12,

45].

In this study, we presented a comprehensive characterization of exosomes derived from adenocarcinoma A549 cell cultures, including analysis of their biophysical and morphological properties, as well as in-depth profiling of their protein and miRNA cargo. By leveraging high-throughput methodologies and bioinformatics approaches, we provided a detailed molecular profiling of the exosomal cargo incorporating functional and interaction network analysis. Additionally, we integrated the proteomic and miRNA profiling information into proteogenomics networks, offering a more in-depth view of the exosomal cargo. This approach enables the detection of potential molecular effects on exosome-recipient cells by highlighting dually-affected genes that are co-regulated through interactions with both exosomal proteins and miRNAs. Besides, the differential secretion analysis of exosomal miRNAs derived from tumorigenic A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells compared to normal lung fibroblast cells (MRC-5) unveiled distinct miRNA profiles.

The exosomes isolated from the A549 cells displayed round shape with distinct lipid-bilayer with uniform distribution at around 40nm, in accordance with previous studies [

46,

47]. Their small size and distinctive disk-like dish shape are characteristic attributes that differentiate exosomal vesicles from other EVs [

48]. The Western Blot and Flow Cytometry analysis verified the presence of tetraspanins CD9 and CD63 at the exosomal vesicles, also shown by previous studies [

40]. Notably, Western Blot analysis of the A549 parental cell lysate revealed more protein migration patterns than in exosomal lysates, suggesting the presence of multiple glycosylation forms of these proteins and indicating a possible selective enrichment of specific glycosylation forms within exosomes. CD63 and CD9 tetraspanins promote tumor development and determine invasiveness in certain cancer types [

49,

50,

51], while glycosylation, as a post-translational process, has a key role in modulating the expression and molecular function of these membrane proteins [

50].

The total proteomic analysis of A549 cell-derived exosomes revealed that the majority of the exosomal proteins enrich the extracellular region, exosomal component and lysosomes, validating the credibility of the methodology followed. The top 20 most enriched proteins in A549 cell-derived exosomes included PRPF38B (PA: Q5VTL8), ACTB (PA: P60709), ACTG2 (PA: P63267), LUM (PA: P51884), HBA1 (PA: P69905), PRSS1 (PA: P07477), ITIH2 (PA: P19823), GOLM1 (PA: Q8NBJ4), TPM4 (PA: P67936) and SPP1 (PA: P10451). These highly abundant proteins and their association with key biological processes could shed light on their potential implication in tumor development and progression in potential exosome-recipient cells. For instance, the PRPF38B gene, which encodes the Pre-mRNA-splicing factor 38B, is predicted to participate in mRNA splicing via precatalytic spliceosome. Alterations in the cellular abundance of the proteins involved in mRNA splicing process, potentially facilitated by extracellular exosomes, could lead to gene expression dysregulation through alternative splicing events and/or errors in the splicing process, which are associated with disease development including different types of cancer [

52,

53]. The LUM gene, encoding a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family, is known to regulate ECM organization and is involved in tumor development and progression [

54]. According to previous reports, the elevated expression of LUM in lung cancer cells promotes the metastatic potential of lung cancer cells via autocrine regulatory mechanism [

55]. Exosomal LUM is also associated with diagnostic and prognostic value in different malignancies including neuroblastoma [

56], gastric cancer [

57]. The HBA1 gene, which encodes the human hemoglobin protein alpha 1, has also been identified as a protein biomarker of NSCLC and SCLC, according to previous studies [

58,

59,

60]. Furthermore, the GOLM1 gene, encoding a resident cis-Golgi membrane protein, promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and tumor cell proliferation, activating matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP13) signaling events that contribute to NSCLC aggressiveness [

61]. Elevated levels of TPM4, a member of the tropomyosin family of actin-binding proteins involved in cytoskeleton organization, are associated with increased cell migration and motility in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines such as A549 and NCI-H1299 [

62].

The bioinformatics-based association analysis identified candidate exosomal proteins associated with lung cancer, including SPP1, CD44, ALB, SPARC, CAT, GAPDH, and CADM1. For instance, the SPP1 gene encoding the secreted phosphoprotein 1, an extracellular matrix (ECM) protein with several adhesion receptor binding domains, is associated with lung cancer progression, resistance to therapy and poor prognosis [

63,

64]. SPP1 protein could also serve as a biomarker for identifying and predicting prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma and other cancers [

63]. Similarly, dysregulation and aberrant expression of CD44, a cell-surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions, contribute to malignancy initiation and progression potentially serving as both biomarker and therapeutic target [

65]. Notably, CD44 protein encapsulated in tumor-derived exosomes, which display that inherent enhanced organotropism, may play a pivotal role in maintaining cancer progression, metastasis [

66,

67] and chemoresistance [

68]. Elevated CD44 expression has also been observed in exosomes from bladder cancer cells, supporting its utility as a tumor biomarker [

69].

The comprehensive profiling of the miRNAs encapsulated in the A549 cell-derived exosomes and the bioinformatics-based subcellular analysis revealed that the identified miRNAs are primarily localized in exosomes, extracellular region and microvesicles. The subcellular analysis results of both isolated exosomal proteins and miRNAs verify the consistency and reliability of the methodologies followed to isolate and analyze macromolecules. The GO enrichment analysis of the identified miRNAs revealed that they participate in regulating several biological processes, including metabolism, gene expression and cellular macromolecule biosynthesis, molecular functions, such as protein/enzyme binding, protein kinase binding, RNA binding, and, molecular pathways associated with cancer progression including MAPK [

70], Wnt [

71] and p53 signaling [

72], DNA damage response [

73], Focal adhesion [

74] and cell cycle regulation [

75]. The top 10 miRNAs selectively enriched in A549 cell-derived exosomes, ranked by the average normalized counts across samples, included hsa-miR-619-5p, hsa-miR-122-5p, hsa-miR-9901, hsa-miR-7704, hsa-miR-151a-3p, hsa-miR-423-5p, hsa-miR-1246, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-let-7i-5p and hsa-miR-100-5p. For instance, the tumor derived exosomal hsa-miR-619-5p, which suppresses RCAN1.4 gene expression, has been associated with tumor growth and metastasis and angiogenesis in endothelial HUVEC cells and lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells [

76]. Also, the upregulated expression of hsa-miR-619-5p in plasma-derived exosomes of lung cancer patients could facilitate potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma, according to previous studies [

77]. Many researches have also shown that miR-122-5p is dysregulated in NSCLC cell-derived EVS and the delivery of miR-122-5p miRNAs enclosed in lung cancer cell-derived EVS promoted migration of liver cells, establishing a pre-metastatic environment for lung cancer metastasis towards liver [

78]. Hsa-miR-122-5p is also involved in NSCLC progression regulating the P53 protein, which is also involved in lipid metabolism of cancer cells via the mevalonate (MVA) pathway. Inhibiting miR-122-5p expression in A549 cells resulted in cell proliferation and migration reduction [

79]. Similarly, exosomal hsa-miR-151a-3p is associated with lung cancer metastasis towards bone potential serving as a novel biomarker for predicting bone metastasis in lung cancer [

80]. Similarly, the miRNAs hsa-miR-423-5p, hsa-miR-1246 and miR-21-5p are associated with lung adenocarcinoma aggressive behavior, stemness, and invasiveness, as well as biomarkers for lung cancer prognosis [

81,

82,

83].

In this study, we also employed a proteogenomics approach by integrating miRNA and proteomic data obtained from miRNA sequencing and total proteomics analysis of well-characterized exosomes derived from the tumorigenic A549 cells. This dual analysis facilitates a more in-depth understanding of the molecular interplay between the exosomal cargo and the potential exosome-recipient cells. By incorporating the multi-level molecular information into complex networks that illustrate interactions among the identified exosomal miRNAs with their target genes and the exosomal proteins with their co-interacting proteins, we aimed to identify genes and proteins in exosome-recipient cells within the tumor microenvironment that may be dually influenced, either synergistically or antagonistically, by the exosomal constituents. This methodology provides valuable insights into the regulatory effects of tumor cell-derived exosomes on cellular functions during cancer progression. The network analysis highlighted the complex molecular interactions within potential target cells upon exosome uptake, with both synergistic and antagonistic effects that may disrupt cellular homeostasis and promote tumorigenic effects. For instance, the CD44 protein, reported to mediate metastasis via the a6β4 integrin [

67] is targeted by four of the 13 exosomal miRNAs depicted in the network. Despite being a miRNA target, CD44 was also detected as an exosomal protein, indicating a potential competitive effect since exosomes deliver both suppressive miRNAs and active CD44 protein to modulate recipient cell function. Additionally, 7 out of 13 exosomal miRNAs, amongst them the has-miR-21-5p, target the oncogene SET, known for its role in cell cycle regulation, motility (via the SET-Rac1 complex), and metastasis (through inhibition of NM23H1) [

84]. Additionally, proteins of the network such as ACAN, CD44, CD74, EEF2, EIF2S1, and ALB, interact with both exosomal miRNAs including hsa-let-7b-5p, hsa-miR-122-5p, hsa-miR-27a-5p, and hsa-miR-423-5p, and exosomal proteins, which potentially affects their expression and cellular function resulting in dysregulated cellular pathways and imbalanced homeostasis of the exosome-recipient cells.

Implementing a gene-to-disease association analysis, we also found that the top 10 Dually Affected Genes (DAGS) associated with lung cancer are ERBB2, CD44, SPP1, GAPDH, APOE, SERPINE1, ENO1, SPARC, CD74, and SET. These genes play roles in receptor signaling, cell adhesion, extracellular matrix organization, and metabolic regulation. These DAGs could serve as key dysregulated genes of the cells internalizing lung cancer-derived exosomes, potentially resulting in cancer-associated cellular alterations involved in tumor maintenance and growth.

This study compared miRNA expression between tumorigenic A549 and non-tumorigenic MRC-5 cells, chosen for their relevance to lung cancer. The differential expression analysis revealed 44 upregulated and 40 downregulated miRNAs in exosomal vesicles derived from tumor cells compared to those derived from non-tumorigenic cells. The GO functional analysis of the upregulated miRNAs indicated their involvement in regulatory activities such as GTPase activity, DNA repair, apoptosis, cell death, as well as processes related to the cellular transport of macromolecules. MiRNA-disease association analysis linked these miRNAs to various cancers and Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting broader impacts on cellular homeostasis. Based on the analysis, the miRNAs hsa-miR-619-5p, hsa-miR-9901, hsa-miR-4755-3p, hsa-miR-4671-5p, and hsa-miR-1303 exhibited the most significant upregulation in the tumor-derived exosomes. Notably, tumorigenic hsa-miR-619-5p is both the most upregulated miRNA in the differential expression analysis and the most selectively enriched miRNA in A549 cell-derived exosomes, establishing it as a promising target for further biological studies to elucidate its precise role in tumor progression, as well as for clinical studies investigating its potential as a biomarker for disease diagnosis. Previous studies have shown that hsa-miR-1303 displayed elevated expression in NSCLC tissue samples also associated with tumor stage, serving as potential biomarker for disease diagnosis and prognosis prediction [

85].

Furthermore, network analysis, which incorporates the target genes of the top five upregulated miRNAs, facilitated the identification of key genes in exosome-recipient cells that may be significantly affected by these miRNAs. This analysis revealed that the KIF3A, POLR3A, YIPF4, GMEB1, NEK8, and IPO9 genes are targeted by at least three different miRNAs. These genes could serve as key molecular players that may experience significant expression alterations in recipient cells following exosome internalization. For instance, the KIF3A gene, which encodes the Kinesin family member 3A motor protein, has been associated with carcinogenesis inhibition and apoptosis induction in NSCLC cells, as well as with adverse survival outcomes in lung cancer patients bearing low KIF3A protein expression levels [

86]. Therefore, targeting of the KIF3A gene by multiple exosomal miRNAs could potentially result in tumorigenic effects.

Figure 2.

Physicochemical, morphological and biochemical characterization of A549 cell-derived exosomes concentrated via ultrafiltration and isolated using the membrane-based affinity binding method (exoEasy Maxi Kit, QIAGEN). (a) DLS analysis of exosomes considering the parameter of volume. The curve represents the means from three successive DLS measurements (n=3, biological replicates). (b) Representative zeta-potential distribution of the exosomes isolated via the proposed methodology The curves obtained by three successive measurements (n=3, technical replicates) are depicted. (c-e) Cryo-TEM analysis of isolated exosomes. Round-shaped exosomes are depicted (black arrows) with distinct exosomal lipid bilayer (white arrows). (f) Detection of CD9 and CD63 exosomal markers as well as cytoplasmic marker β-actin via Western Blot analysis. Equal amount of protein (30μg) from exosomes and whole cell lysate as calculated by BCA protein assay kit were loaded in wells of 15% SDS-PAGE gel for separation, followed by Western Blotting. (g) Flow Cytometry-based histogram representing the negative control-beads incubated with the anti-CD9 PE antibody without the addition of exosomes (blue curved), as well as the A549 cell-derived exosomes captured by the beads with subsequent incubation with the anti-CD9 antibody (red curve). The dot plots represent the gating strategies for the exosome containing samples and negative control-beads. Data were analyzed using FlowJo.

Figure 2.

Physicochemical, morphological and biochemical characterization of A549 cell-derived exosomes concentrated via ultrafiltration and isolated using the membrane-based affinity binding method (exoEasy Maxi Kit, QIAGEN). (a) DLS analysis of exosomes considering the parameter of volume. The curve represents the means from three successive DLS measurements (n=3, biological replicates). (b) Representative zeta-potential distribution of the exosomes isolated via the proposed methodology The curves obtained by three successive measurements (n=3, technical replicates) are depicted. (c-e) Cryo-TEM analysis of isolated exosomes. Round-shaped exosomes are depicted (black arrows) with distinct exosomal lipid bilayer (white arrows). (f) Detection of CD9 and CD63 exosomal markers as well as cytoplasmic marker β-actin via Western Blot analysis. Equal amount of protein (30μg) from exosomes and whole cell lysate as calculated by BCA protein assay kit were loaded in wells of 15% SDS-PAGE gel for separation, followed by Western Blotting. (g) Flow Cytometry-based histogram representing the negative control-beads incubated with the anti-CD9 PE antibody without the addition of exosomes (blue curved), as well as the A549 cell-derived exosomes captured by the beads with subsequent incubation with the anti-CD9 antibody (red curve). The dot plots represent the gating strategies for the exosome containing samples and negative control-beads. Data were analyzed using FlowJo.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the 68 proteins identified in at least 2 biological replicates of the A549 cell-derived exosomes isolated via the modified protocol. (a) Top 20 enriched exosomal proteins identified using a multi-criteria approach, integrating Score (protein identification confidence), Coverage (percentage of protein sequence covered by identified peptides), and Area (integrated peak area of peptide ion signals). (b) Venn diagram illustrating protein overlap between the A549 cell-derived exosome and exosomes registered in Vesiclepedia database. The overlap analysis was conducted by FunRich tool. (c) Cellular Component enrichment analysis according to FunRich tool depicting the five different statistically significant (log10(p-values)>2 subcellular localizations of the identified proteins (d) Plot illustrating the association of the identified exosomal proteins with lung cancer biomarkers, derived from text-mining methods and DisGeNET database.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the 68 proteins identified in at least 2 biological replicates of the A549 cell-derived exosomes isolated via the modified protocol. (a) Top 20 enriched exosomal proteins identified using a multi-criteria approach, integrating Score (protein identification confidence), Coverage (percentage of protein sequence covered by identified peptides), and Area (integrated peak area of peptide ion signals). (b) Venn diagram illustrating protein overlap between the A549 cell-derived exosome and exosomes registered in Vesiclepedia database. The overlap analysis was conducted by FunRich tool. (c) Cellular Component enrichment analysis according to FunRich tool depicting the five different statistically significant (log10(p-values)>2 subcellular localizations of the identified proteins (d) Plot illustrating the association of the identified exosomal proteins with lung cancer biomarkers, derived from text-mining methods and DisGeNET database.

Figure 4.

Functional bioinformatics-based analysis of the identified A549 cell-derived exosomal proteins. (a) Top 15 significantly enriched GO biological process (BP) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (b) Top 15 significantly enriched GO cellular component (CC) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (c) Top 15 significantly enriched GO molecular function (MF) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (d) The REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis on the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosome. The top 15 statistically significant pathways are listed, and their colors correspond to the adjusted p-values. (e) PPI network showing the interactions amongst the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The network was constructed using the STRING-DB tool. The exosomal proteins are shown as red nodes (low number of linked interacting proteins) and purple nodes (high number of linked interacting proteins). Proteins directly interact with the exosomal proteins and are not identified in exosomes as depicted as greed nodes. The line width indicates the confidence of data support. A minimum confidence interaction of 0.7 was selected for high confidence. The multi-colored dotted lines enclose 5 different subnetworks of exosomal proteins.

Figure 4.

Functional bioinformatics-based analysis of the identified A549 cell-derived exosomal proteins. (a) Top 15 significantly enriched GO biological process (BP) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (b) Top 15 significantly enriched GO cellular component (CC) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (c) Top 15 significantly enriched GO molecular function (MF) terms associated with the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The gene ratio and statistical significance (p-value < 0.05, following Benjamini and Hochberg’s adjustment method) are also depicted. (d) The REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis on the genes mapped to the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosome. The top 15 statistically significant pathways are listed, and their colors correspond to the adjusted p-values. (e) PPI network showing the interactions amongst the proteins identified in A549 cell-derived exosomes. The network was constructed using the STRING-DB tool. The exosomal proteins are shown as red nodes (low number of linked interacting proteins) and purple nodes (high number of linked interacting proteins). Proteins directly interact with the exosomal proteins and are not identified in exosomes as depicted as greed nodes. The line width indicates the confidence of data support. A minimum confidence interaction of 0.7 was selected for high confidence. The multi-colored dotted lines enclose 5 different subnetworks of exosomal proteins.

Figure 5.

Global microRNA profiling of exosomes derived from A549 cells (a) Top 20 enriched miRNAs based on the average of normalized count across the samples (b) Subcellular localization analysis of the identified miRNAs based on RNALocate database. (c) GO enrichment analysis based on Biological Process of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (d) GO enrichment analysis based on Cellular Comonent of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (e) GO enrichment analysis based on Molecular Function of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (f) Pathway enrichment analysis based on REACTOME of the identified exosomal miRNAs. For all enrichment analyses, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to adjust p-values for false discovery rate (FDR), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Global microRNA profiling of exosomes derived from A549 cells (a) Top 20 enriched miRNAs based on the average of normalized count across the samples (b) Subcellular localization analysis of the identified miRNAs based on RNALocate database. (c) GO enrichment analysis based on Biological Process of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (d) GO enrichment analysis based on Cellular Comonent of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (e) GO enrichment analysis based on Molecular Function of the identified exosomal miRNAs. (f) Pathway enrichment analysis based on REACTOME of the identified exosomal miRNAs. For all enrichment analyses, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to adjust p-values for false discovery rate (FDR), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Proteogenomic approach combining multi-level molecular information associated with A549 cell-derived exosomes as obtained via high-throughput methodologies. (a) A combined network analysis depicting the dual impact of miRNAs and proteins encapsulated within A549 cell-derived exosomes on potential recipient cells. The network integrates miRNA-target gene interactions (sourced from miRTarBase, TarBase, and miRecords databases) with protein-protein interactions retrieved from the STRING database. Key genes affected by both exosomal miRNAs and proteins, through synergistic or antagonistic interactions, are represented in more complex subnetworks. The blue nodes represent the identified exosomal proteins, the light green nodes indicate the protein interactors of the exosomal proteins/genes that are also targeted by exosomal miRNAs, the intense green nodes represent genes targeted solely by exosomal miRNAs, and the purple nodes denote the top 20 exosomal miRNAs. (b) A plot depicting the results of text mining conducted using the DisGeNET platform to identify dually affected genes (DAGs) associated with lung cancer pathophysiological mechanisms.

Figure 6.

Proteogenomic approach combining multi-level molecular information associated with A549 cell-derived exosomes as obtained via high-throughput methodologies. (a) A combined network analysis depicting the dual impact of miRNAs and proteins encapsulated within A549 cell-derived exosomes on potential recipient cells. The network integrates miRNA-target gene interactions (sourced from miRTarBase, TarBase, and miRecords databases) with protein-protein interactions retrieved from the STRING database. Key genes affected by both exosomal miRNAs and proteins, through synergistic or antagonistic interactions, are represented in more complex subnetworks. The blue nodes represent the identified exosomal proteins, the light green nodes indicate the protein interactors of the exosomal proteins/genes that are also targeted by exosomal miRNAs, the intense green nodes represent genes targeted solely by exosomal miRNAs, and the purple nodes denote the top 20 exosomal miRNAs. (b) A plot depicting the results of text mining conducted using the DisGeNET platform to identify dually affected genes (DAGs) associated with lung cancer pathophysiological mechanisms.

Figure 7.

Differential expression analysis of exosomal miRNAs derived from tumorigenic A549 cells and normal MRC-5 cells. (a) PCA plot demonstrating the clustering of samples derived from A549 and MRC-5 exosomes based on miRNA expression profiles. (b) Volcano plot illustrating the differentially expressed miRNAs between A549 and MRC-5 exosomes, with the x-axis displaying log2(fold change) and the y-axis showing -log10(p-value). (c) The top upregulated miRNAs in A549 cell-derived exosomes with log2 fold change >5 (d) Heatmap displaying the differentially expressed miRNAs between A549 and MRC-5 exosomes, with miRNAs on the y-axis and samples on the x-axis. Color intensity represents log2(fold change), with warm colors indicating upregulation and cool colors indicating downregulation in A549 cell-derived exosomes.

Figure 7.

Differential expression analysis of exosomal miRNAs derived from tumorigenic A549 cells and normal MRC-5 cells. (a) PCA plot demonstrating the clustering of samples derived from A549 and MRC-5 exosomes based on miRNA expression profiles. (b) Volcano plot illustrating the differentially expressed miRNAs between A549 and MRC-5 exosomes, with the x-axis displaying log2(fold change) and the y-axis showing -log10(p-value). (c) The top upregulated miRNAs in A549 cell-derived exosomes with log2 fold change >5 (d) Heatmap displaying the differentially expressed miRNAs between A549 and MRC-5 exosomes, with miRNAs on the y-axis and samples on the x-axis. Color intensity represents log2(fold change), with warm colors indicating upregulation and cool colors indicating downregulation in A549 cell-derived exosomes.

Figure 8.

Functional analysis of the upregulated miRNAs in A549-cell derived exosomes compared to MRC-5 cell-derived exosomes (a) GO enrichment analysis of the upregulated miRNAs based on miRTarBase resource. (b) GO enrichment analysis based on Biological Process of the upregulated miRNAs. (c) Pathway enrichment analysis based on miRWalk database of the upregulated miRNAs. (d) Disease enrichment analysis, based on MNDR (Molecular Network of Disease Relations) database to identify diseases significantly associated with the upregulated miRNAs. (e) Network representation of experimentally validated target genes for the top five upregulated miRNAs. The miRNAs and their target genes are represented with purple and green nodes respectively. Edges between miRNAs and genes illustrate validated interactions. This network visualization underscores potential key regulatory genes associated with the highly expressed miRNAs in the dataset.

Figure 8.

Functional analysis of the upregulated miRNAs in A549-cell derived exosomes compared to MRC-5 cell-derived exosomes (a) GO enrichment analysis of the upregulated miRNAs based on miRTarBase resource. (b) GO enrichment analysis based on Biological Process of the upregulated miRNAs. (c) Pathway enrichment analysis based on miRWalk database of the upregulated miRNAs. (d) Disease enrichment analysis, based on MNDR (Molecular Network of Disease Relations) database to identify diseases significantly associated with the upregulated miRNAs. (e) Network representation of experimentally validated target genes for the top five upregulated miRNAs. The miRNAs and their target genes are represented with purple and green nodes respectively. Edges between miRNAs and genes illustrate validated interactions. This network visualization underscores potential key regulatory genes associated with the highly expressed miRNAs in the dataset.

Where Normalized Value is the Score, Coverage and Area values of each protein after applying normalization, Value is the Score, Coverage or Area value of each protein, Min Value and Max Value are the minimum and maximum values of all the proteins of the dataset considering the parameters of Score, Coverage or Area.

Where Normalized Value is the Score, Coverage and Area values of each protein after applying normalization, Value is the Score, Coverage or Area value of each protein, Min Value and Max Value are the minimum and maximum values of all the proteins of the dataset considering the parameters of Score, Coverage or Area. Where NormalizedScore, NormalizedCoverage and NormalizedArea are the Score, Coverage or Area of each protein normalized to a range between 0 and 1, and CombinedScore is the final score assigned to each identified protein based on the multi-criteria ranking approach.

Where NormalizedScore, NormalizedCoverage and NormalizedArea are the Score, Coverage or Area of each protein normalized to a range between 0 and 1, and CombinedScore is the final score assigned to each identified protein based on the multi-criteria ranking approach.