Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Non-Clinical and Clinical Data Mining

2.2. Animal Studies

2.3. Bioanalysis

2.4. Data Analysis and Modelling

2.4.1. Rata PK Data Analysis

2.4.2. Correlation Analysis

2.4.3. Clearance Allometry Modeling

3. Results

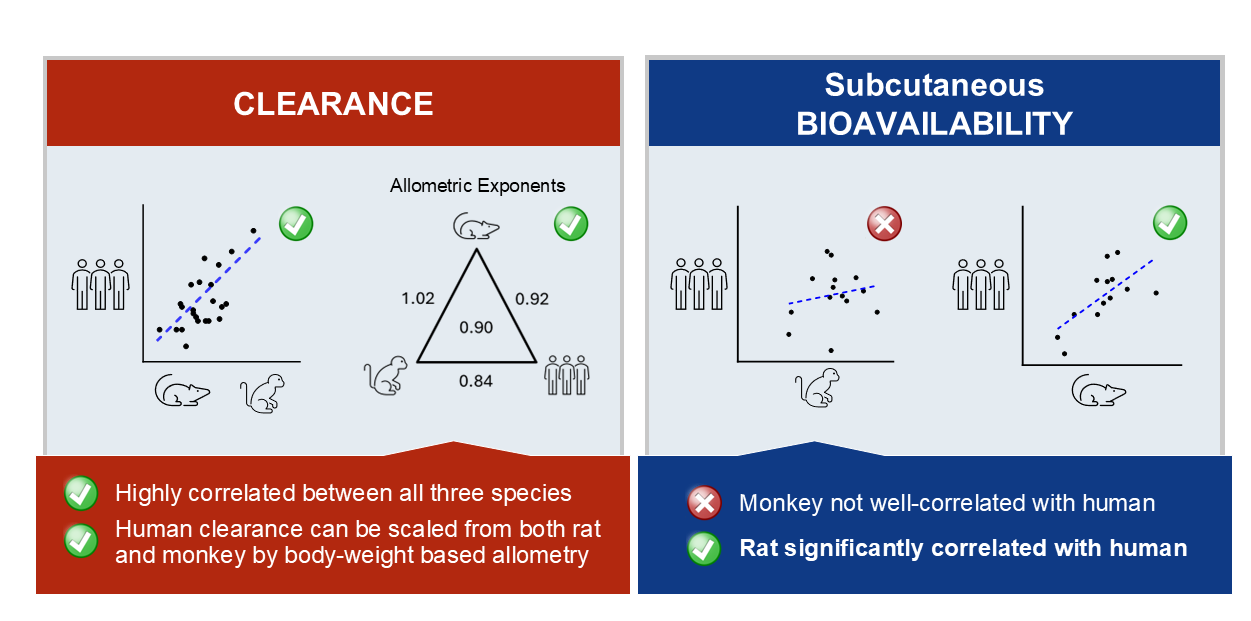

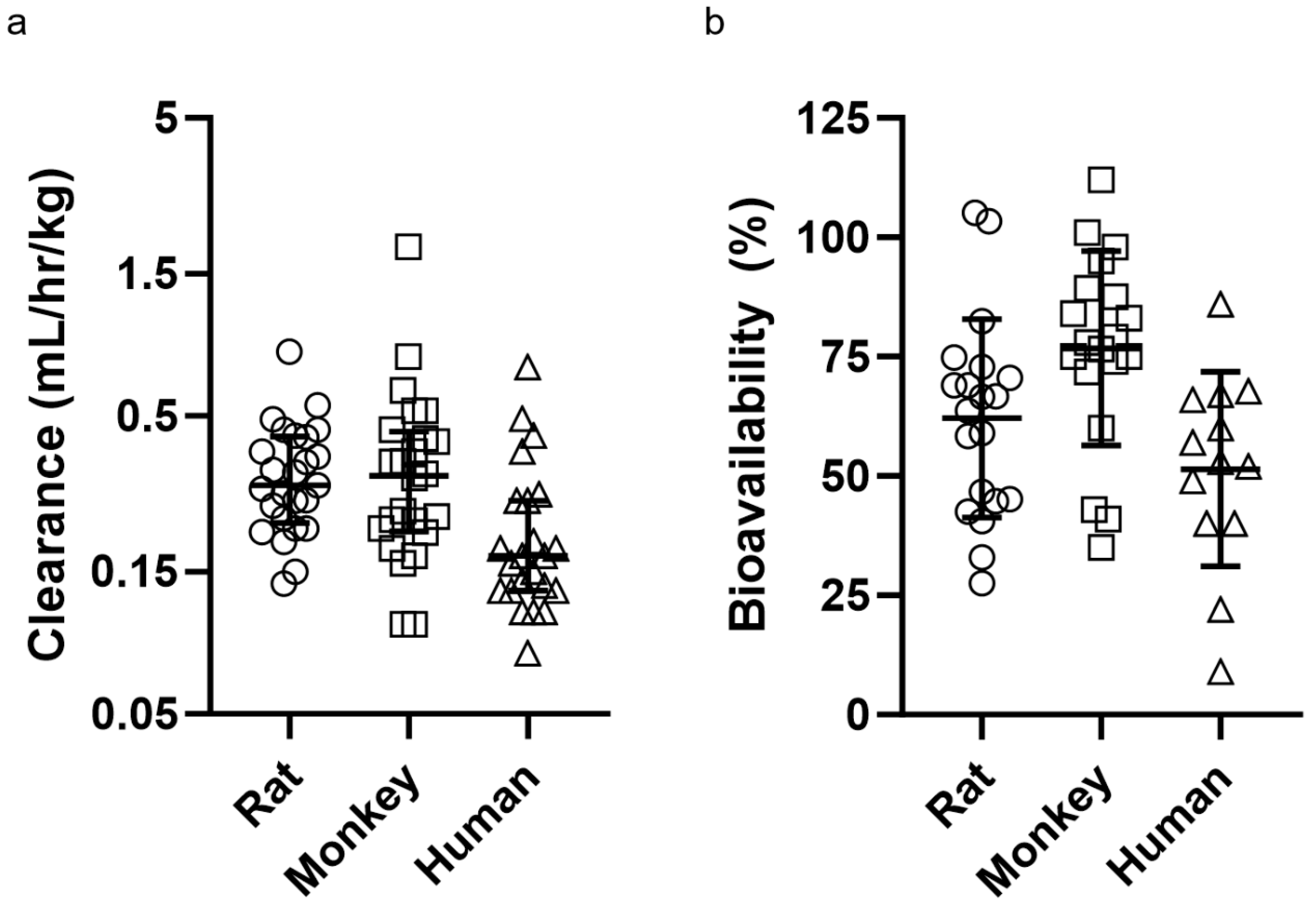

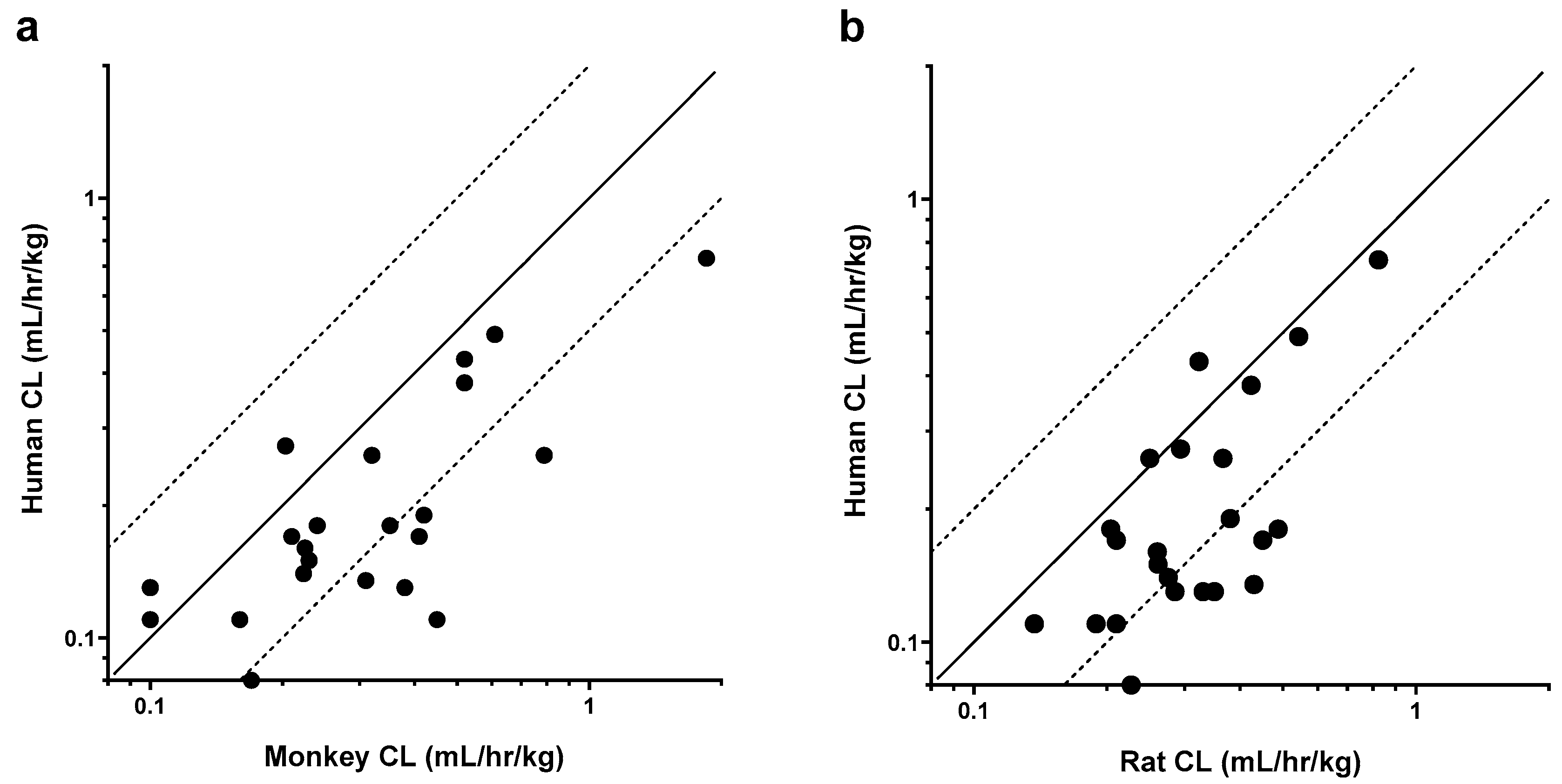

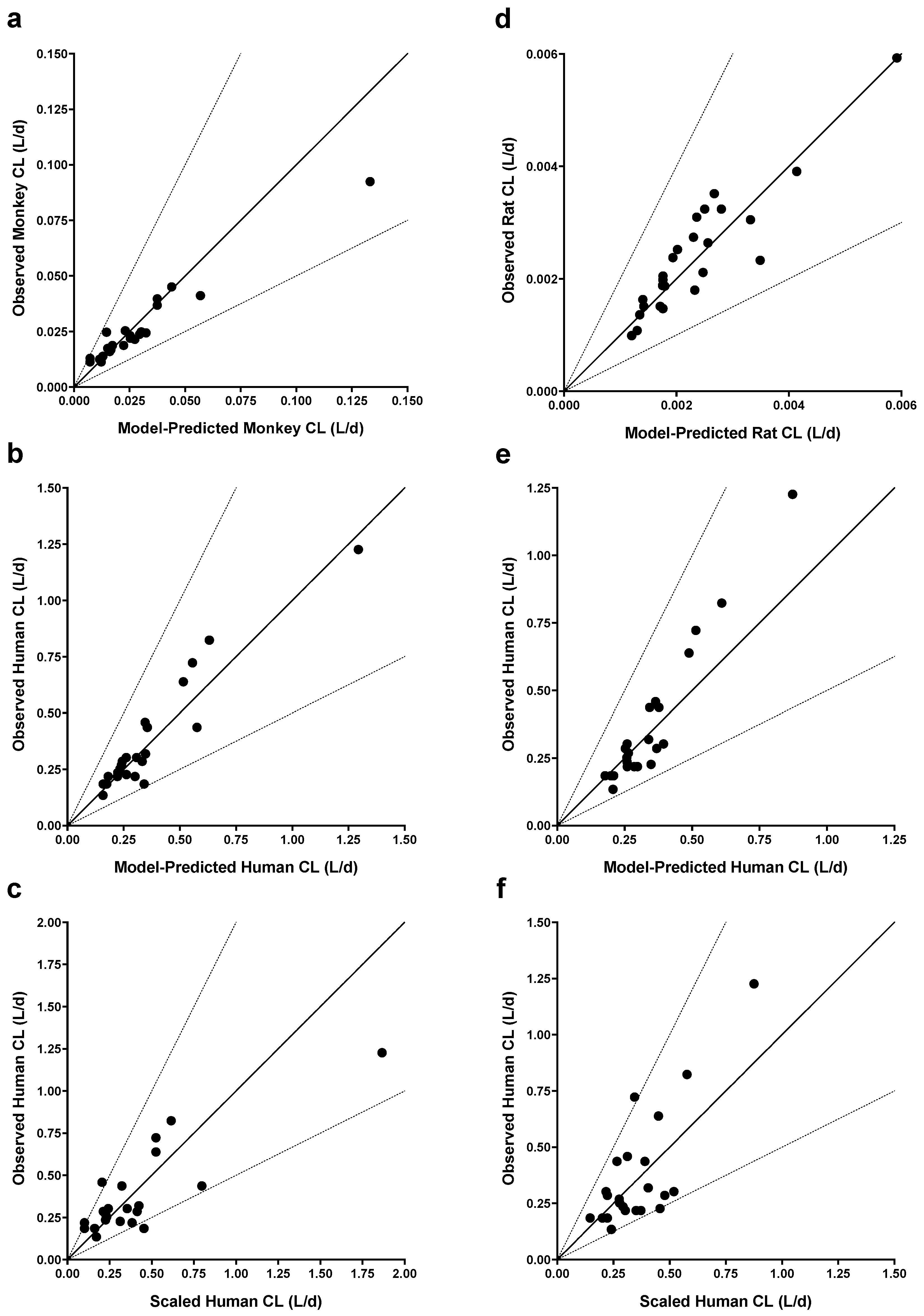

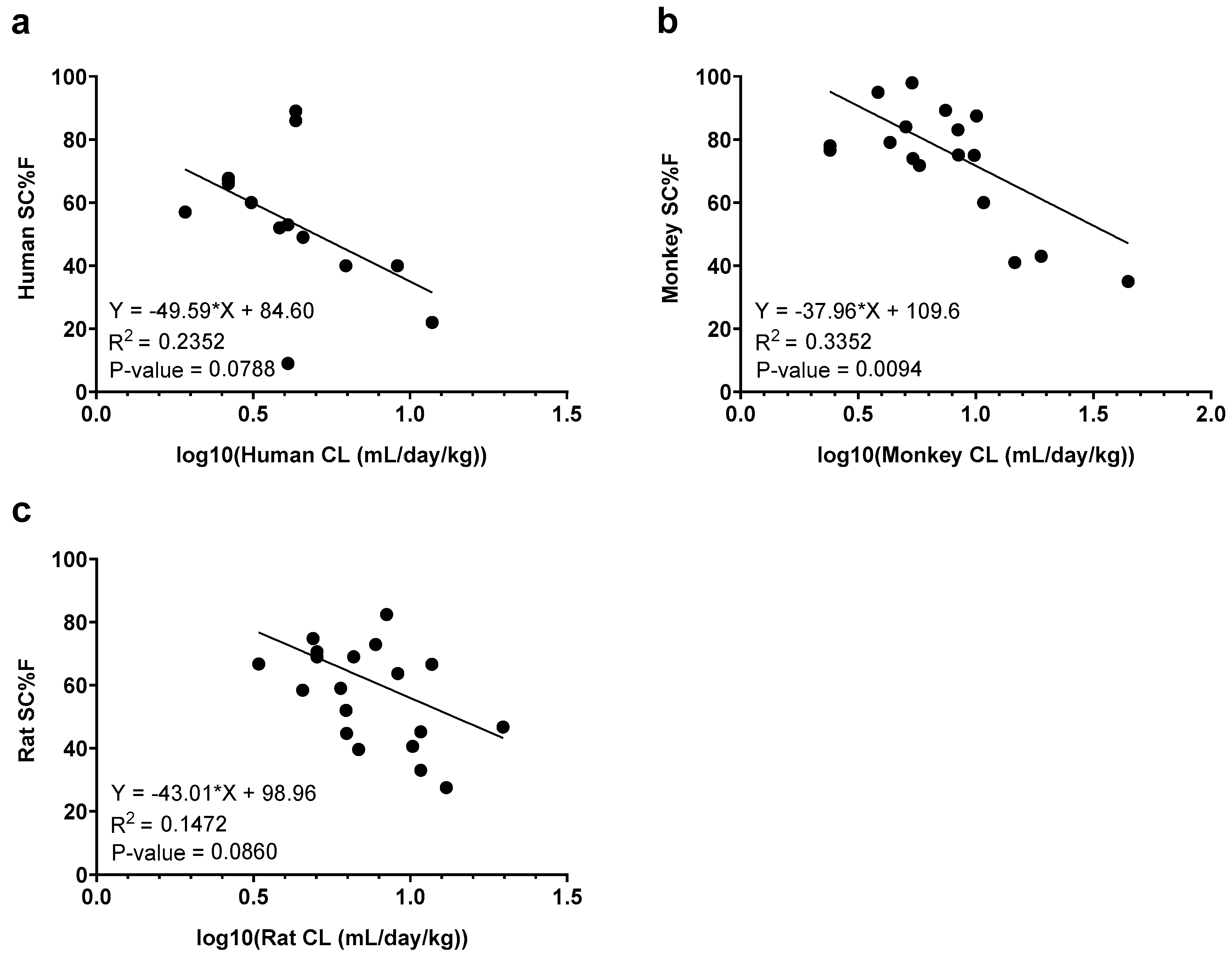

3.1. Rat and Monkey Predict Human Clearance

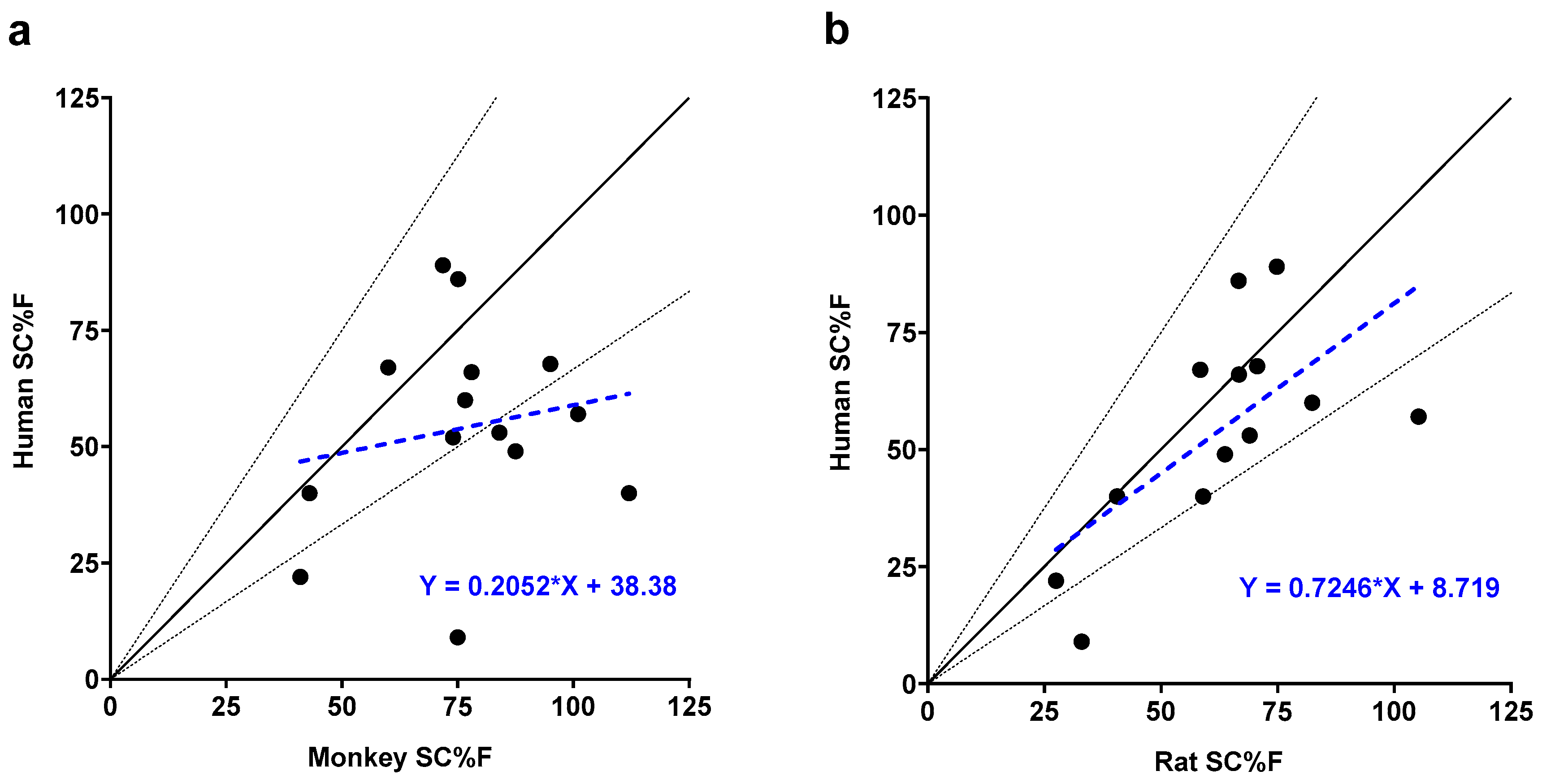

3.2. Rat SC Bioavailability Significantly Correlates with Human

4. Discussion

4.1. Rat and Monkey Are Predictive Models for mAb Clearance

4.2. Rat as a Predictive Model for mAb SC Bioavailability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Monoclonal Antibody | Animal number | IV AUCinf (mg*hr/mL) |

IV AUC % Extrapolated |

IV Tlast (hr) |

Animal number | SC AUCinf (mg*hr/mL) |

SC AUC % Extrapolated |

SC Tlast (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alirocumab | 1 | 10200 | 1.42 | 1008 | 4 | 6280 | 2.20 | 504 |

| 2 | 9390 | 0.0 | 1008 | 5 | 8120 | 3.54 | 840 | |

| 3 | 9880 | 1.31 | 1008 | 6 | 5890 | 3.46 | 336 | |

| canakinumab | 1 | 16800 | 4.37 | 840 | 4 | 11600 | 0.18 | 504 |

| 2 | 18000 | 10.5 | 1008 | 5 | 9070 | 0.54 | 336 | |

| 3 | 13600 | 0.48 | 672 | 6 | 7590 | 0.01 | 336 | |

| guselkumab | 1 | 6720 | 0.16 | 504 | 4 | 8000 | 6.00 | 1008 |

| 2 | 12500 | 8.65 | 1008 | 5 | 4970 | 0.10 | 336 | |

| 3 | 6590 | 0.34 | 504 | 6 | 3480 | 1.03 | 168 | |

| secukinumab | 1 | 22400 | 21.2 | 1008 | 4 | 11000 | 0.47 | 504 |

| 2 | 20800 | 17 | 1008 | 5 | 15100 | 7.32 | 672 | |

| 3 | 22500 | 16.9 | 1008 | 6 | 17700 | 18.7 | 672 | |

| tabalumab | 1 | 11400 | 2.61 | 672 | 4 | 15800 | 16.2 | 1008 |

| 2 | 14500 | 11.2 | 1008 | 5 | 9790 | 0.22 | 504 | |

| 3 | 14200 | 12.7 | 1008 | 6 | 16700 | 17.10 | 1008 | |

| ustekinumab | 1 | 13300 | 10.2 | 1008 | 4 | 7420 | 0.24 | 336 |

| 2 | 14000 | 11.7 | 1008 | 5 | 10100 | 1.71 | 1008 | |

| 3 | 15700 | 11.2 | 1008 | 6 | 12900 | 8.50 | 1008 | |

| risankizumab | 1 | 15100 | 14.3 | 1008 | 4 | 12200 | 10.4 | 1008 |

| 2 | 15200 | 11.9 | 1008 | 5 | 10800 | 9.85 | 1008 | |

| 3 | 13900 | 12 | 1008 | 6 | 9970 | 1.29 | 1008 | |

| mAb 4 | 1 | 8090 | 1.72 | 336 | 4 | 7340 | 0.10 | 672 |

| 2 | 8300 | 0.02 | 504 | 5 | 5500 | 2.00 | 336 | |

| 3 | - | - | - | 6 | 12600 | 15.5 | 840 | |

| mAb 5 | 1 | 12600 | 5.16 | 1008 | 4 | 5130 | 0.72 | 336 |

| 2 | 12400 | 7.31 | 1008 | 5 | 5380 | 1.90 | 336 | |

| 3 | 9930 | 3.23 | 1008 | 6 | 5140 | 3.50 | 504 | |

| mAb 6 | 1 | 11400 | 15.4 | 1008 | 4 | 5160 | 15.3 | 336 |

| 2 | 11200 | 15.7 | 1008 | 5 | 3860 | 7.26 | 240 | |

| 3 | 9280 | 12.5 | 1008 | 6 | - | - | - | |

| mAb 9 | 1 | 4800 | 0.66 | 1008 | 4 | 1280 | 0.10 | 504 |

| 2 | 5740 | 2.64 | 1008 | 5 | 1010 | 1.14 | 240 | |

| 3 | 6230 | 0.14 | 504 | 6 | 2320 | 5.72 | 1008 | |

| mAb 12 | 1 | 3430 | 0.19 | 504 | 4 | 2110 | 0.44 | 336 |

| 2 | 4190 | 2.57 | 1008 | 5 | 1340 | 0.42 | 240 | |

| 3 | 3420 | 2.17 | 1008 | 6 | 1720 | 0.26 | 240 | |

| mAb 13 | 1 | 9940 | 5.83 | 1008 | 4 | 4430 | 0.16 | 336 |

| 2 | 8820 | 4.89 | 1008 | 5 | 9120 | 6.14 | 1008 | |

| 3 | 9150 | 3.76 | 1008 | 6 | - | - | - | |

| mAb 14 | 1 | 6320 | 1.33 | 1008 | 4 | 3290 | 0.00 | 336 |

| 2 | 6870 | 1.52 | 1008 | 5 | 2200 | 3.32 | 240 | |

| 3 | 8320 | 4.4 | 1008 | 6 | 3240 | 0.47 | 336 |

References

- Martin, K.P.; Grimaldi, C.; Grempler, R.; Hansel, S.; Kumar, S. Trends in industrialization of biotherapeutics: a survey of product characteristics of 89 antibody-based biotherapeutics. MAbs 2023, 15, 2191301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, Y. Which factors matter the most? Revisiting and dissecting antibody therapeutic doses. Drug Discov Today 2021, 26, 1980–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, W.F.; Bhansali, S.G.; Morris, M.E. Mechanistic determinants of biotherapeutics absorption following SC administration. AAPS J 2012, 14, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D.S.; Sanchez-Felix, M.; Badkar, A.V.; Mrsny, R. Accelerating the development of novel technologies and tools for the subcutaneous delivery of biotherapeutics. J Control Release 2020, 321, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta-Mannan, A.; Witcher, D.R.; Lu, J.; Wroblewski, V.J. Influence of improved FcRn binding on the subcutaneous bioavailability of monoclonal antibodies in cynomolgus monkeys. MAbs 2012, 4, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.; Eichling, S.; Franzen, L.; Herzog, V.; Ickenstein, L.M.; Jere, D.; Nonis, L.; Schwach, G.; Stoll, P.; Venczel, M.; et al. Evaluation of In Vitro Tools to Predict the In Vivo Absorption of Biopharmaceuticals Following Subcutaneous Administration. J Pharm Sci 2022, 111, 2514–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Zhou, H.; Jiao, Q.; Davis, H.M. Interspecies scaling of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: initial look. J Clin Pharmacol 2009, 49, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Q.; Salinger, D.H.; Endres, C.J.; Gibbs, J.P.; Hsu, C.P.; Stouch, B.J.; Hurh, E.; Gibbs, M.A. Quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetics for monoclonal antibodies: retrospective analysis of monkey as a single species for first-in-human prediction. Clin Pharmacokinet 2011, 50, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Felix, M.; Burke, M.; Chen, H.H.; Patterson, C.; Mittal, S. Predicting bioavailability of monoclonal antibodies after subcutaneous administration: Open innovation challenge. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 167, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.H.; Papakyriacou, P.; Gardener, M.J.; Gliddon, L.; Weston, C.J.; Lalor, P.F. The Contribution of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells to Clearance of Therapeutic Antibody. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 753833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Meng, Y.G.; Hoyte, K.; Lutman, J.; Lu, Y.; Iyer, S.; DeForge, L.E.; Theil, F.P.; Fielder, P.J.; Prabhu, S. Subcutaneous bioavailability of therapeutic antibodies as a function of FcRn binding affinity in mice. MAbs 2012, 4, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, W.F.; Jacobsen, B. Subcutaneous absorption of biotherapeutics: knowns and unknowns. Drug Metab Dispos 2014, 42, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D.S.; Kourtis, L.C.; Thyagarajapuram, N.R.; Sirkar, R.; Kapur, S.; Harrison, M.W.; Bryan, D.J.; Jones, G.B.; Wright, J.M. Optimizing the Bioavailability of Subcutaneously Administered Biotherapeutics Through Mechanochemical Drivers. Pharm Res 2017, 34, 2000–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, P. Predicting Human Bioavailability of Subcutaneously Administered Fusion Proteins and Monoclonal Antibodies Using Human Intravenous Clearance or Antibody Isoelectric Point. AAPS J 2023, 25, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, I. A Single Animal Species-Based Prediction of Human Clearance and First-in-Human Dose of Monoclonal Antibodies: Beyond Monkey. Antibodies (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm.

- Lu, R.M.; Hwang, Y.C.; Liu, I.J.; Lee, C.C.; Tsai, H.Z.; Li, H.J.; Wu, H.C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J Biomed Sci 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Gallolu Kankanamalage, S.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y. Optimization of therapeutic antibodies. Antib Ther 2021, 4, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, L.B.; Wade, J.; Wang, M.; Tam, A.; King, A.; Piche-Nicholas, N.; Kavosi, M.S.; Penn, S.; Cirelli, D.; Kurz, J.C.; et al. Establishing in vitro in vivo correlations to screen monoclonal antibodies for physicochemical properties related to favorable human pharmacokinetics. MAbs 2018, 10, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotzel, I.; Theil, F.P.; Bernstein, L.J.; Prabhu, S.; Deng, R.; Quintana, L.; Lutman, J.; Sibia, R.; Chan, P.; Bumbaca, D.; et al. A strategy for risk mitigation of antibodies with fast clearance. MAbs 2012, 4, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, R.; Thomas, J.; Kapur, S.; Woldeyes, M.; Rauk, A.; Robarge, J.; Feng, J.; Abbou Oucherif, K. Predicting the clinical subcutaneous absorption rate constant of monoclonal antibodies using only the primary sequence: a machine learning approach. MAbs 2024, 16, 2352887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, J.T.; Meibohm, B. Pharmacokinetics of Monoclonal Antibodies. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2017, 6, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce, R.; Abad, L.; Amaravadi, L.; Gelzleichter, T.; Gore, E.; Green, J.; Gupta, S.; Herzyk, D.; Hurst, C.; Ivens, I.A.; et al. Immunogenicity of biologically-derived therapeutics: assessment and interpretation of nonclinical safety studies. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2009, 54, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, A.; Keunecke, A.; van Steeg, T.J.; van der Graaf, P.H.; Avery, L.B.; Jones, H.; Berkhout, J. Linear pharmacokinetic parameters for monoclonal antibodies are similar within a species and across different pharmacological targets: A comparison between human, cynomolgus monkey and hFcRn Tg32 transgenic mouse using a population-modeling approach. MAbs 2018, 10, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiche, Y.N.; Yeung, Y.A.; Chaparro-Riggers, J.; Barman, I.; Strop, P.; Chin, S.M.; Pham, A.; Bolton, G.; McDonough, D.; Lindquist, K.; et al. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binds independently to both sites of the IgG homodimer with identical affinity. MAbs 2015, 7, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall'Acqua, W.F.; Kiener, P.A.; Wu, H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 23514–23524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraya, K.; Tachibana, T. Translational Approach for Predicting Human Pharmacokinetics of Engineered Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies with Increased FcRn-Binding Mutations. BioDrugs 2023, 37, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbie, G.J.; Criste, R.; Dall'acqua, W.F.; Jensen, K.; Patel, N.K.; Losonsky, G.A.; Griffin, M.P. A novel investigational Fc-modified humanized monoclonal antibody, motavizumab-YTE, has an extended half-life in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 6147–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, L.B.; Wang, M.; Kavosi, M.S.; Joyce, A.; Kurz, J.C.; Fan, Y.Y.; Dowty, M.E.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, A.; et al. Utility of a human FcRn transgenic mouse model in drug discovery for early assessment and prediction of human pharmacokinetics of monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 2016, 8, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuber, T.; Frese, K.; Jaehrling, J.; Jager, S.; Daubert, D.; Felderer, K.; Linnemann, M.; Hohne, A.; Kaden, S.; Kolln, J.; et al. Characterization and screening of IgG binding to the neonatal Fc receptor. MAbs 2014, 6, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta-Mannan, A. Mechanisms Influencing the Pharmacokinetics and Disposition of Monoclonal Antibodies and Peptides. Drug Metab Dispos 2019, 47, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, A.M.; Kaminskas, L.M.; Smith, A.; Nicolazzo, J.A.; Porter, C.J.; Bulitta, J.B.; McIntosh, M.P. The lymphatic system plays a major role in the intravenous and subcutaneous pharmacokinetics of trastuzumab in rats. Mol Pharm 2014, 11, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, L.; Gershkovich, P.; Mendelman, A.; Amsili, S.; Ezov, N.; Hoffman, A. The role of the lymphatic system in subcutaneous absorption of macromolecules in the rat model. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2007, 67, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, P.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Tran, D.; Seo, S.K. Impact of injection sites on clinical pharmacokinetics of subcutaneously administered peptides and proteins. J Control Release 2021, 336, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.A.; Tsonis, C.; Sellins, K.; Rushlow, K.; Scharton-Kersten, T.; Colditz, I.; Glenn, G.M. Transcutaneous immunization of domestic animals: opportunities and challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2000, 43, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A. Use of nontraditional animals for evaluation of pharmaceutical products. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2006, 2, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Wang, W.; Rasmussen, J.C.; Joshi, A.; Houston, J.P.; Adams, K.E.; Cameron, A.; Ke, S.; Kwon, S.; Mawad, M.E.; et al. Quantitative imaging of lymph function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, H3109–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosh, E.H.; Vistnes, L.M.; Ksander, G.A. The panniculus carnosus in the domestic pig. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1977, 59, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, R.A.; Afifi, A.K.; Miyauchi, R. Anatomy Atlases: Illustrated Encyclopedia of Human Anatomic Variation: Opus I: Muscular System: Alphabetical Listing of Muscles: P: Panniculus Carnosus Available online:. Available online: https://www.anatomyatlases.org/AnatomicVariants/MuscularSystem/Text/P/05Panniculus.shtml (accessed on 03 Sept 2024).

| Monoclonal Antibody | Rat CL (mL/hr/kg) | Monkey CL (mL/hr/kg) | Human CL (mL/hr/kg) | Rat SC%F |

Monkey SC%F | Human SC%F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alirocumab | 0.488a | 0.352c | 0.180b | 66.6a | 75.1 | 86.0b |

| canakinumab | 0.189a | 0.450c | 0.110b | 58.4a | 60.0 | 67.0b |

| guselkumab | 0.380a | 0.420c | 0.190b | 63.7a | 87.5 | 49.0b |

| secukinumab | 0.137a | 0.100c | 0.110b | 66.7a | 78.0 | 66.0b |

| tabalumab | 0.227a | 0.170c | 0.080c | 105.2a | 101.0 | 57.0b |

| ustekinumab | 0.210a | 0.160c | 0.110b | 70.6a | 95.0 | 67.8b |

| bevacizumab | 0.275c | 0.223c | 0.140b | 69.0 | 98.0 | - |

| ocrelizumab | 0.330c | - | 0.130b | - | - | - |

| risankizumab | 0.204a | 0.240c | 0.180b | 74.8a | 71.8 | 89.0b7 |

| mAb 1 | 0.210c | 0.210 | 0.170c | 69.0 | 84.0 | 53.0c |

| mAb 2 | 0.260 | 0.225 | 0.160c | - | 74.0 | 52.0c |

| mAb 3 | 0.250c | 0.790c | 0.260c | 59.0c | 43.0c | 40.0c |

| mAb 4 | 0.366a | 0.320c | 0.260c | 103.4a | - | - |

| mAb 5 | 0.261a | 0.230c | 0.150c | 44.7a | - | - |

| mAb 6 | 0.285a | 0.380c | 0.130c | 42.5a | - | - |

| mAb 7 | 0.350c | 0.100c | 0.130c | 82.4c | 76.6c | 60.0c |

| mAb 8 | 0.430c | 0.310c | 0.135c | - | 89.3c | - |

| mAb 9 | 0.543a | 0.610c | 0.490c | 27.5a | 41.0c | 22.0c |

| mAb 10 | 0.450c | 0.410c | 0.170c | 33.0c | 75.0c | 9.0c |

| mAb 11 | 0.293c | 0.203c | 0.273c | - | - | - |

| mAb 12 | 0.823a | 1.850c | 0.730c | 46.7a | 35.0c | - |

| mAb 13 | 0.323a | 0.520c | 0.430c | 72.9a | - | - |

| mAb 14 | 0.424a | 0.520c | 0.380c | 40.6a | 112.0c | 40.0c |

| mAb 15 | 0.450c | 0.350c | - | 45.2c | 83.1c | - |

| mAb 16 | 0.150c | 0.180c | - | - | 79.1c | - |

| Spearman rho | Monkey CL vs. Human CLa | Rat CL vs. Human CLa | Rat CL vs. Monkey CLa |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| 95% CI | 0.33 to 0.85 | 0.20 to 0.80 | 0.18 to 0.79 |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| Sample size | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Parameters | Monkey-to- Human | Rat-to- Human | Rat-to- Monkey | 3-Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αTVa (%RSE) | 0.0087 (15) | 0.0065 (8) | 0.0074 (10) | 0.0072 (9) |

| 95% CI | 0.0062 – 0.0112 | 0.0055 – 0.0075 | 0.006 – 0.0088 | 0.0059 – 0.0085 |

| βTVb (%RSE) | 0.84 (4) | 0.92 (2) | 1.02 (4) | 0.90 (2) |

| 95% CI | 0.78 – 0.90 | 0.88 – 0.95 | 0.94 – 1.10 | 0.87 – 0.94 |

| ω2(α) c (%RSE) | 0.27 (38) | 0.17 (35) | 0.22 (42) | 0.23 (40) |

| σ2 d (%RSE) | 0.08 (23) | 0.07 (18) | 0.08 (33) | 0.1 (23) |

| Correlation Coefficient | Monkey SC%F vs. Human SC%F |

Rat SC%F vs. Human SC%F |

Rat SC%F vs. Monkey SC%F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman rho | |||

| R | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.39 |

| 95% CI | -0.47 to 0.61 | 0.11 to 0.88 | -0.15 to 0.75 |

| p-value | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Simple linear regression | |||

| r2 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.16 |

| p-value | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| Sample size | 14 | 13 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).