1. Introduction

HER2 gene amplification occurs in about 20% of invasive breast cancer, 6% to 37% of gastric cancers and 5% of colorectal cancers. HER2 mutations are detected in about 2.5% of lung cancers, 15%-25% of breast cancers, 20% of gastric cancers, 20% of bile duct cancers, 27% of ovarian cancers and 18%~80% in endometrial cancer. As a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer, HER2 overexpression or HER2 oncogene amplification demonstrates increased tumor aggressiveness, recurrence and poorer survival [

1,

2]. While the members of human EGFR or HER receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) subfamily, EGFR (HER1/erbB1), HER2 (neu/erbB2), HER3 (erbB3), and HER4 (erbB4) are structurally conserved with an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular kinase domain [

3,

4].

Currently, there are a variety of approved HER2-targeted therapies for HER2-positive cancer. Monoclonal antibody-based therapies significantly improving outcomes in HER2-positive breast cancer, but these treatments eventually become ineffective due to acquired resistance [

6]. HER2-targeting ADC structurally composed of a humanized anti-HER2 antibody, provide valuable therapy with the potential to respond to cytotoxic agents-insensitive breast cancer and other HER2 expressing cancers in clinical practice [

7], while interstitial lung disease and pneumonitis, Ocular toxicity, gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity are important risks requiring careful monitoring and prompt intervention [

8]. As traditional chemotherapy modality, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) inhibit tyrosine kinase phosphorylation by binding to HER2 intracellular tyrosine kinase and interfering with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding, thereby achieving anti-tumor effects through multiple pathways. In addition, small molecule TKIs are widely used in patients with HER2 positive ABC brain metastases and has the potential to hinder tumor penetration and accumulation due to their unique ability to cross the blood-brain tumor barrier or some other biological barrier.

SPH5030 is a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting HER2, with a modified structure from tucatinib and pyrotinib. It has advantages such as target selectivity of tucatinib and the irreversible inhibitory effect of pyrotinib [

9]. SPH5030 can inhibit both constitutive and ligand-induced ErbB signaling, have shown non-cross-resistance with Trastuzumab in preclinical studies and also have promising activity in heavily pretreated metastatic HER2-positive cancer patients [

10]. Irreversible inhibitors are covalently bound to cysteine residues in the receptor ATP site (cys797 for EGFR and cys805 for HER2) through an electrophilic structure in the molecule, and thus remain better inhibited against mutant HER2 receptors than reversible inhibitors [

11,

12,

13]. Therefore, irreversible small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have potential advantages and attract more attention [

14].

The objectives of the present work were to characterize the pharmacokinetic, tissue distribution and excretion properties after administration of SPH5030 in Sprague Dawley rats and Cynomolgus monkeys, as well as in vitro drug-drug interaction assessment and metabolite identification in different species. These preclinical studies may shed light on the indication selection and adverse reactions expectation in the future clinical trials.

3. Discussion

SPH5030 is a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting HER2, which has advantages of better target selectivity and the irreversible inhibitory effect. SPH5030 inhibits the kinase activity of HER2 and EGFR at IC

50 values of 3.51 nM and 8.13 nM and is an irreversible HER2 inhibitors with better HER2 selectivity, of which the IC

50 values of HER2 inhibitory activity is 23 times smaller than Neratinib and 21.1 times than Pyrotinib [

9]. Furthermore, SPH5030 shows better cell proliferation inhibitory activities in cell-based assays with IC

50 NCI-N87 of 1.09 nM and IC

50BT-474 of 2.01 nM, and assumed to attenuate the off-target adverse events in patients.

In vitro and in vivo preclinical pharmacokinetics studies show good druggability and less drug-drug interactions in SPH5030, which is expected a good clinical application prospects in the future. In rats and monkeys, SPH5030 exhibits a low clearance and widely tissue distributed drug characteristics under intravenous and oral administration. Besides, SPH5030 was the major circulating entity in rats and monkeys and no gender differences in drug plasma exposure were observed. The oral bioavailability of SPH5030 is about 56.4–64.3% in rats and 18.1–38.0% in monkeys, and the elimination half-life (T

1/2) 4.61~9.14 h in rats and monkeys. M8 is detected in plasma about 12.7-14.9% and 22-53% of SPH5030 for rats and monkeys, respectively. As a low solubility and low permeability compound, as well as the weak efflux transporter substrate and inhibitor, SPH5030 can be corroborated by non-linear oral exposure across some ranges of the dose. As is reported in 2024 ACSO annual meeting abstracts [

20], in Phase I clinical trials, SPH5030 plasma exposures from single-dose and steady-state showed a proportional dose increase, but absorption of SPH5030 was found to reach a plateau from 400 to 600mg.

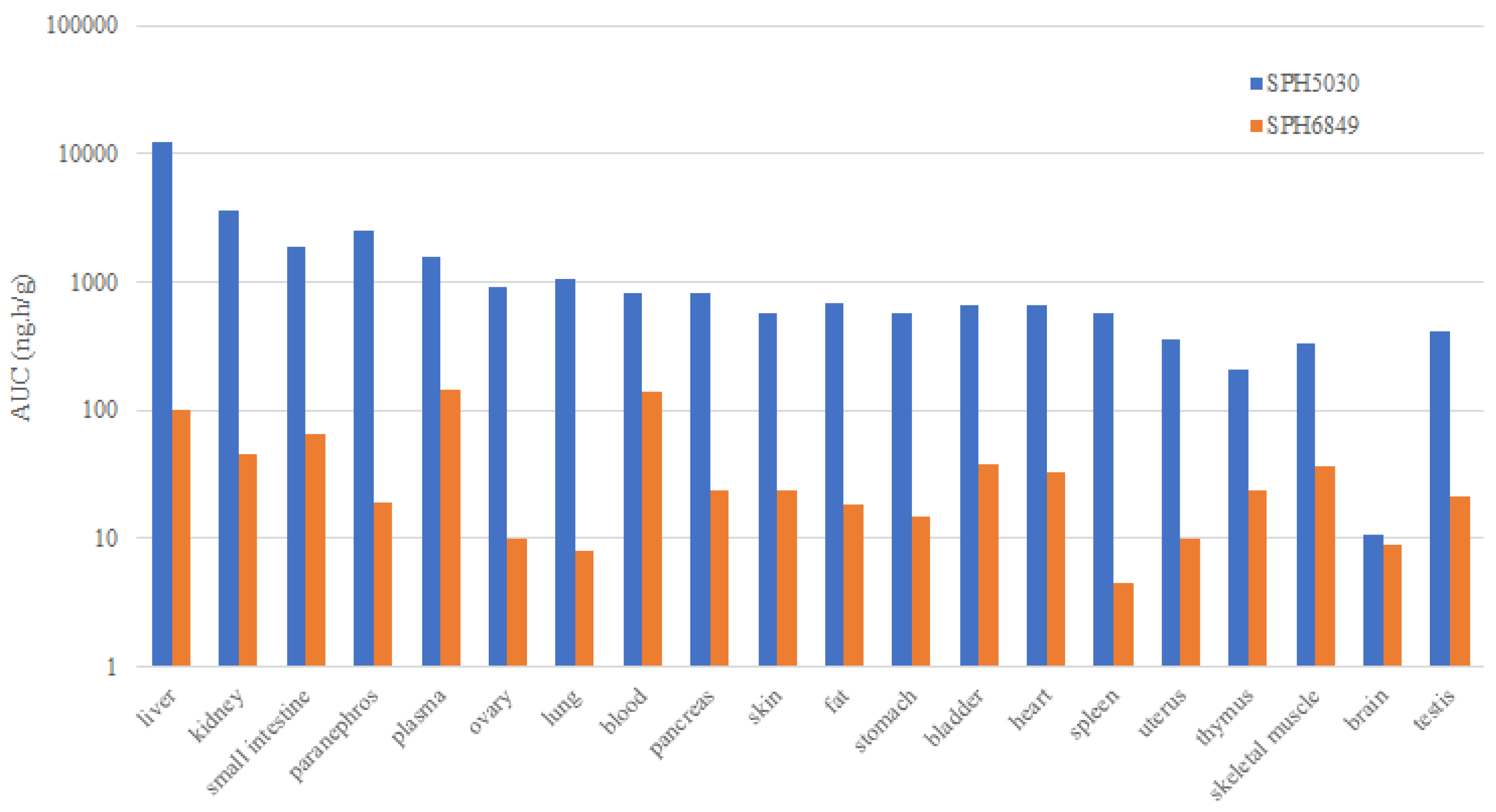

As to the tissue distribution, SPH5030 is widely distributed and maintain a high concentration in the target organ with peak tissue concentration of about 5 hours after dosing. AUC

2-48 values of SPH5030 in lung and liver tissues were more than 10 times, and in ovary, kidney, pancreas and fat tissues, about 3~8 times that of plasma. These pharmacokinetic properties of SPH5030 allow for a reasonable dosing frequency and reduction in the dose administered. Therefore, SPH5030 can be considered for treatment of lung and ovarian cancers related to HER2-positive or HER2 mutations. Furthermore, SPH5030 can cross the blood-brain barrier and is distributed in brain tissue, which also has the potential to be used in the patients with brain metastases. Meanwhile, SPH5030 exhibited good efficacy effects in the clinical trials [

20]. Of the 28 evaluable patients for efficacy, 6 pts (21.4%) achieved partial response (PR, breast cancer (BC) = 5, colorectal cancer (CRC) = 1), while 16 patients (57.1%) achieved stable disease (4 patients SD≥ 24 weeks,14.3%). Objective response rate (ORR) was 21.4%, disease control rate was 78.6%, and clinical benefit rate was 35.7%. Three patients in the 600 mg dose group achieved PR, with ORR of 50.0%.

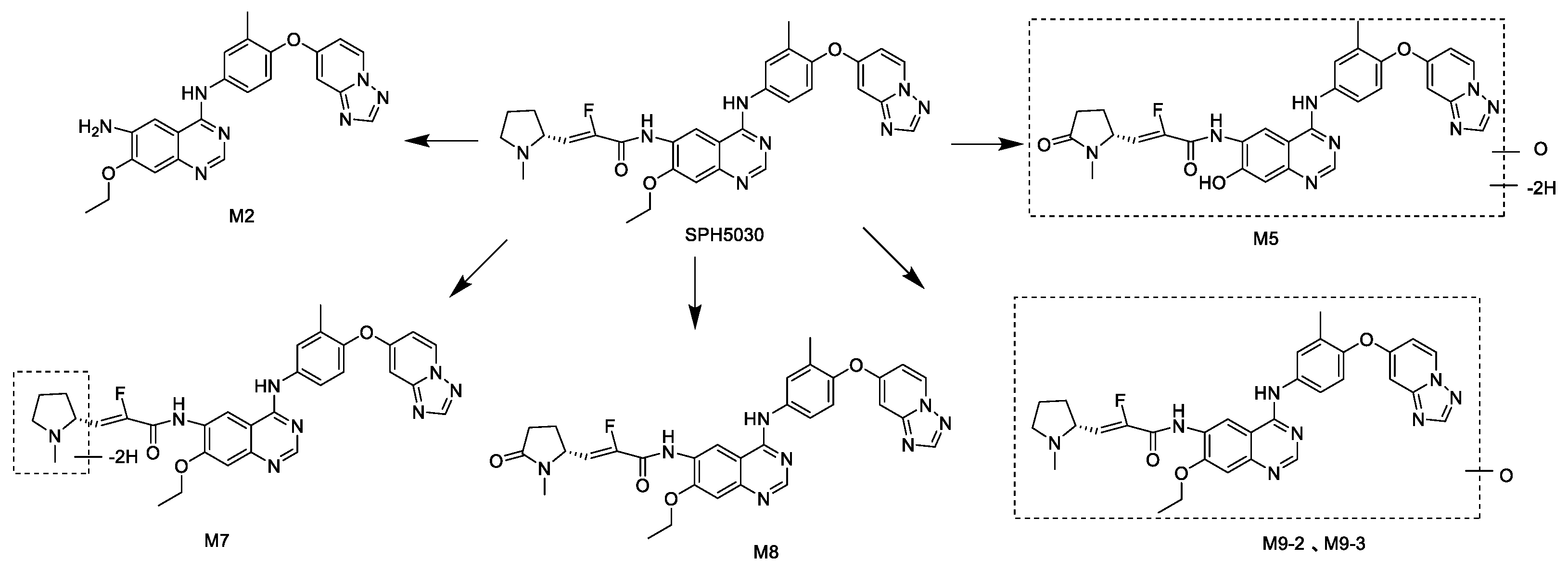

Finally, the in vitro drug-drug interaction studies of SHP5030 were preliminary assessed, due to the fact that there are DDI problems in most of the HER2-targeting inhibitors, such as Tucatinib, Pyrotinib and Rapatinib. Once orally absorbed, SPH5030 was eliminated through extensive oxidative metabolism and amide hydrolysis metabolism, and to a lesser extent as an unchanged drug excreted through feces, urine and hepatobiliary routes, which accounted for approximately 30.91% of the dose in rats. SPH5030 undergoes oxidative metabolism by P450 isoenzymes, of which M7 and M8 is mainly catalyzed by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, to a lesser extent, CYP2C8. In vitro study showed weak inhibitory effects with IC

50 of 16.0 μM, 17.1 μM and 20.7 μM for CYP2C8, CYP3A4/5 (1’-hydroxyl-Midazolam) and CYP3A4/5 (6β-hydroxy-Testosterone). At the recommended clinical dose of 400 mg, the safety margin of CYP3A4 inhibition is at least 5~7 times higher than human plasma C

max (

Table 3). Although in vitro induction study showed increased tendency in CYP3A4 enzyme mRNA level after treatment of SPH5030, no concentration-dependent increase of the enzyme activities of CYP3A4 was found in vitro study. Furthermore, the concentration of SPH5030 did not decrease after multiple consecutive dosing both in rats and monkeys. Therefore, the risk of CYP3A4 enzyme induction of SPH5030 remains low and need further validation in the clinical trials. These characteristics may exclude most of the possible drug-drug interaction in clinical trails.

Phenotyping experiments demonstrated that CYP3A4 is the most active enzyme responsible for the biotransforma tion of SPH5030. Considering that CYP3A4 has a broad substrate specificity and a number of multiple-medication drugs were mainly metabolized by CYP3A4, it is worth monitoring the effects of co-administrated CYP3A4 inhibitors, inducers or substrates in future clinical trials [

21]. Besides, SPH5030 is the inhibitor of uptake transporters MATE1 and MATE2-K, and not the substrate for OAT1, OAT3. As MATE1 and MATE2-K transporters are always involved in cationic drug renal tubular secretion in concert with OAT1, which partially explains the reason for less excretion through urine of SPH5030.

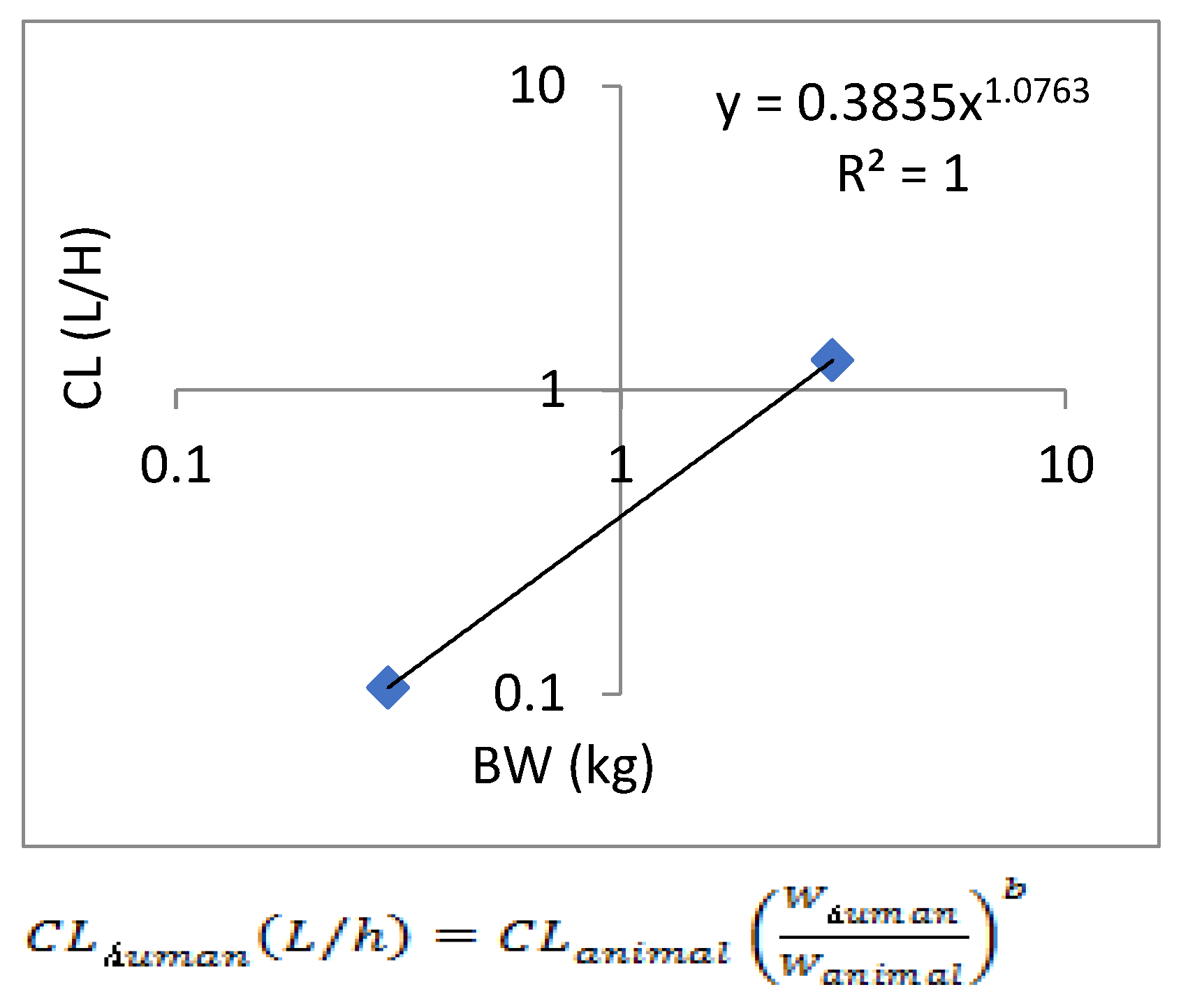

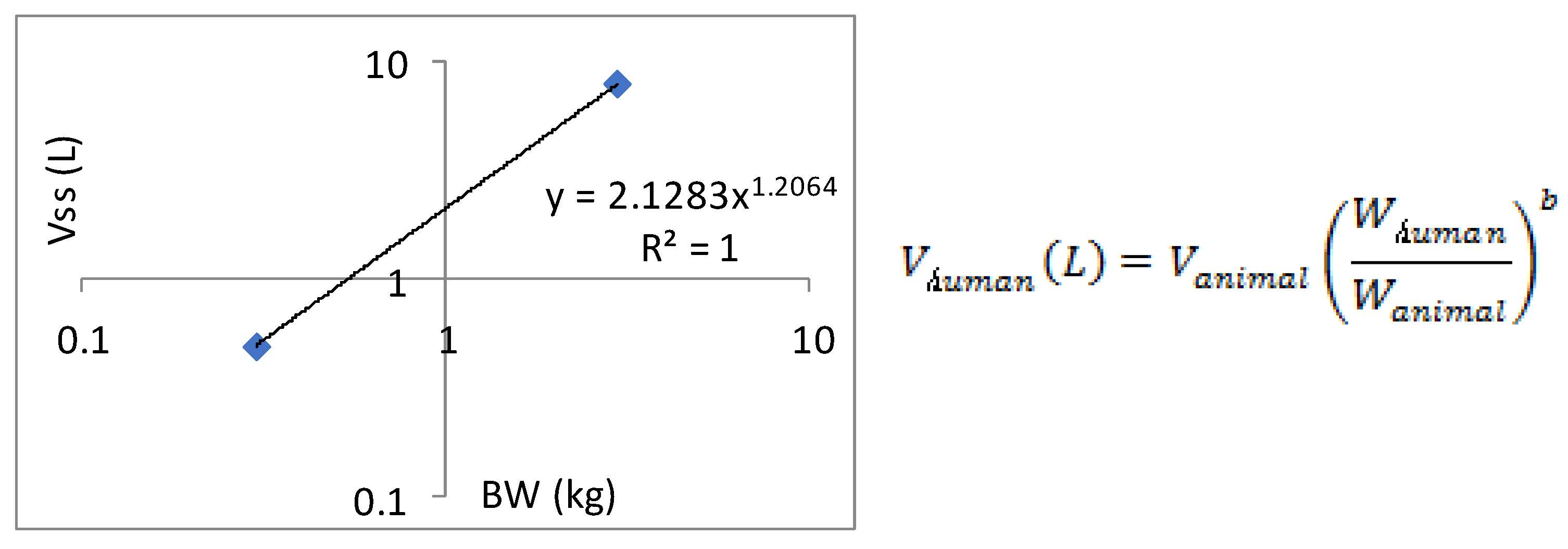

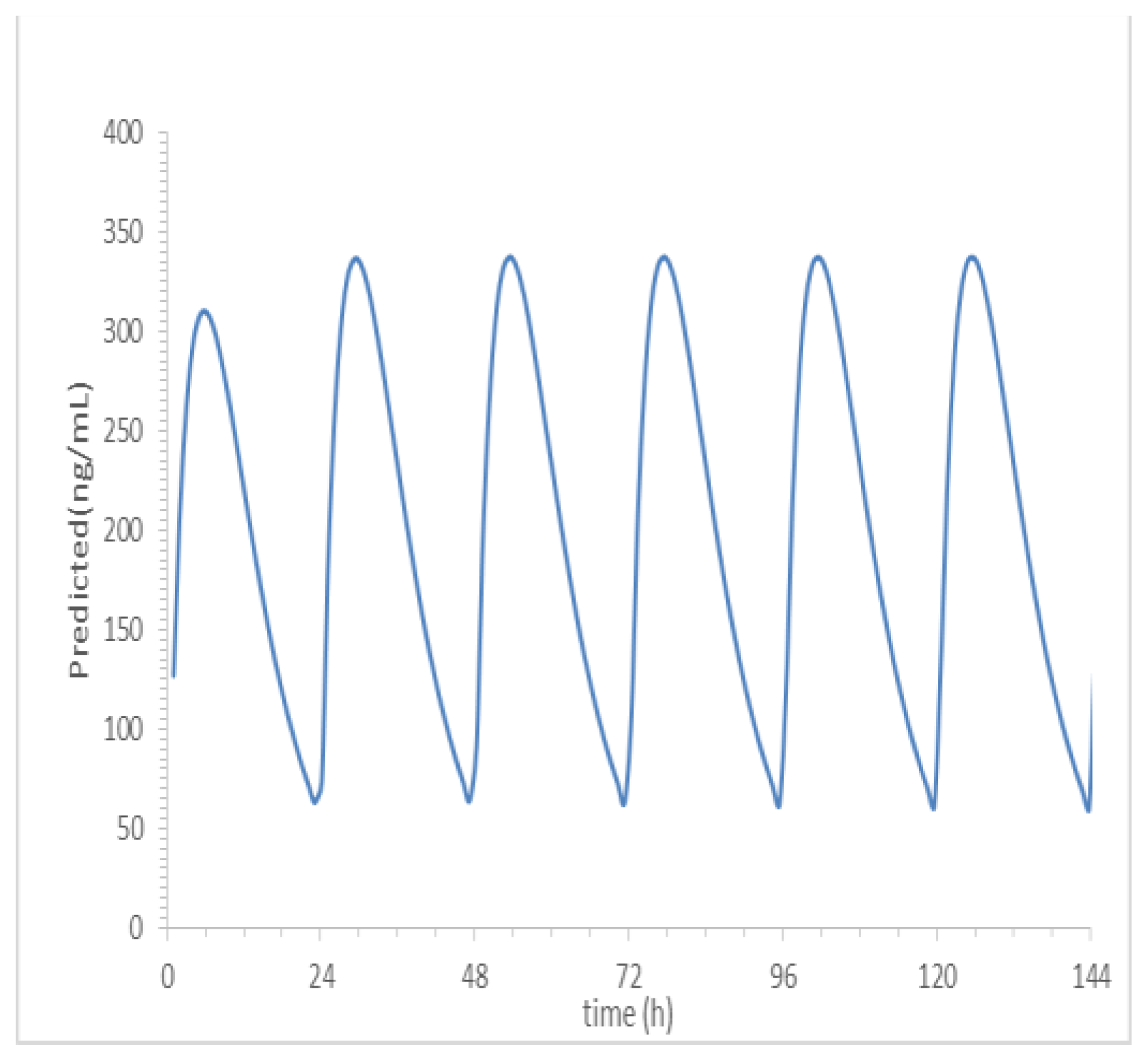

Allometric scaling for the prediction of human CL and Vdss of SPH5030 was based on interspecies simple allometric scaling of rat and cynomolgus monkey intravenous pharmacokinetic parameters [

17]. Since the distribution phase rates of SPH5030 far exceeded the terminal elimination rates for each of the preclinical species tested, we assumed a one-compartment model for the prediction human pharmacokinetics [

22,

23]. Prediction of human CL was performed by extrapolating preclinical species unbound plasma intravenous clearance, calculated based on experimental determination of plasma protein binding fraction unbound (fu,p) for each species including human. Results from this simple allometric scaling method provided a CLp of 0.75 mL/min/kg with an allometric exponent of 1.0763. To eliminate the significant uncertainty in the allometric amplification model, a single genus allometric growth model method was adopted. Based on the average results of the two genera, the CL of the human body was calculated to be 8.71 L/h. In addition, the in vivo-in vitro extrapolation (IVIVE) method was used to predict a human clearance rate of 16.67 L/h based on human liver cell metabolism data. Therefore, the predicted human clearance rate is 21.15 L/h, and the apparent volume of distribution (V/F) is 216.5 L, and the absorption rate constant K

a is 0.5011. Based on the predicted results of human PK parameters, after oral administration of 100mg SPH5030, the peak concentration of the first administration was about 310 ng/mL, the steady-state valley concentration of C

min, ss were about 55 ng/mL.

Based on the report in clinical trials, SPH5030 was well tolerated at doses ranging from 50 to 600mg.Treatment-emerged adverse events (TEAEs) and ≥grade (G) 3 TEAEs occurred in 30 pts (100.0%) and 10 pts (33.3%), respectively. The most common TRAEs (≥20%) were diarrhea (66.7%, 16.7% ≥ G3), creatinine increased (30.0%, 0% ≥ G3), hypokalemia (23.3%, 3.3% ≥ G3), fatigue (23.3%, 3.3% ≥ G3), AST increased (20.0%, 0% ≥ G3), and bilirubin increased (20.0%, 0%≥ G3). One in 6 pts receiving 600 mg dose experienced a DLT (diarrhea, G3). Overall, as an orally irreversible HER2 inhibitor, SPH5030 demonstrated desirable pharmacokinetic properties and safety profiles, which is expected to have an ideal clinical application prospect in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drugs, Chemicals and Reagents

SPH5030 maleate and its major metabolite (SPH6849) were synthesized by Shanghai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HPLC grade acetonitrile and methanol were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), formic acid was obtained from Fluka (Munich, Germany), and ammonium acetate was obtained from ROE (ROE, USA). Purified water was generated by Milli-Q gradient water purification system (Millipore, Molsheim, France).

4.2. Animals

Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (170-280g, 6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Shanghai Sipur-Bikai Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd and Shanghai JSJ Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. Cynomolgus monkeys (3-5 kg, 3–6 years old) were purchased from Hainan Xinzhengyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All animals were treated in accordance with Institutional Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

4.3. Analytical Method and Method Validation

LC-MS/MS consists of an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) and a Sciex Triple QuadTM 6500+ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX) with electrospray ionization (ESI) source. MS detection was performed in positive ESI mode (scan mode MRM) with the source temperature maintaining at 550 °C. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Analyst software (AB SCIEX). A Eclipse Plus C18(100 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 μm; Agilent) thermostatted at 40 °C. The mobile phases were 2 mM NH4OAc & 0.2% FA in H2O (A) and ACN (B) at a flow rate of 0.600 mL/min. The UPLC-MS/MS method for all animal plasma, tissue, feces, bile, and urine samples were validated for selectivity, lower limit of quantification, linearity, accuracy and precision, dilution reliability, matrix effects, and stability.

4.4. Intravenous and Intragastric PK Studies of SPH5030

SPH5030 was administrated at a dose of 4 mg/kg (intravenous, i.v.), 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, and 16 mg/kg (intragastric, i.g.) for both rats and Cynomolgus monkeys. Blood samples were collected from the retrobulbar venous plexus at 0 and 5 min, and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 24, 36 and 48 h for rats (0.2 mL for each time point), and from a limb vein at 0, 5, and 15 min and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 24, 36 and 48 h for monkeys (0.2 mL for each time point) post-dose. The collected blood samples were placed in EDTA-K2 anticoagulation test tubes, centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min (4 °C). The plasma was separated within 2 h and stored at 70 °C for testing. The concentrations of SPH5030 and its metabolite SPH6849 in the plasma of rats and cynomolgus monkeys at different time points were determined by validated LC-MS/MS method. The non-compartmental model of Phoenix WinNonlin 7.0 software (Pharsight, USA) was used to calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters of rats and cynomolgus monkeys after administration.

4.5. Tissue Distribution and Excretion Test in SD Rats

SD rats were divided into four time groups (3/sex/group) and fasted for 12 h before drug administration. 8 mg/kg SPH5030 was dosed by gavage and were anesthetized and bled through the abdominal aorta at 2 h, 5 h, 15 h and 48 h after administration, respectively, and dissected immediately. The tissues were collected and washed with cold saline, labeled and stored at 70 °C for testing.

In excretion test, SPH5030 was administered to SD rats by gavage at a dose of 8 mg/kg after fasted overnight. Urine and faecal samples were collected from rats (3M/3F) from 0-8, 8-24, 24-48 h, 48-72 h and 72-96 h after administration. SD rats were placed in metabolic cages, fed and watered freely, and blank urine and fecal samples were collected. The volume of the urine samples was recorded and the fecal samples were weighed. Another six SD rats (3M/3F) were anesthetized and bile duct cannulation was performed to allow bile collection at 0 - 4, 4 - 8, 8 - 24 and 24 - 48 h post dosing and the volumes were recorded. All samples were stored at -70ºC for testing. The concentrations of SPH5030 and SPH6849 in tissues, feces, urine and bile were determined by the validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method.

4.6. In Vivo and In Vitro Metabolite Identification

The plasma samples collected from rats and monkeys of the same sex at 1 h, 5 h, 10 h and 24 h after drug administration were mixed in equal volumes to obtain combined plasma samples, respectively. The combined biological samples were taken separately, added with approximately twice the volume of acetonitrile. The supernatant was taken, blown dry at 40℃ under nitrogen flow, and re-dissolved with acetonitrile/water (1: 9, v/v) for UPLC-UV/Q-TOF MS analysis. PeakView ® V1.2 and MetabolitePilot V1.5 software from AB Sciex were used for data analysis.

The hepatocytes incubation system (100 µL) contained William’s Medium E medium (pH 7.4), hepatocytes at a cell density of 1.0×106 cells/mL and SPH5030 at a final concentration of 3.0 µM was incubated at 37 °C. After 3 h of reaction, 100 µL of ice-cold acetonitrile was added to stop the reaction. The incubated samples were diluted with acetonitrile, vortexed for 1 min, and centrifuged for 5 min (14 000 rpm). The supernatant was collected, dried under nitrogen flow at 40ºC, and then reconstituted with acetonitrile/water (1:9, v/v) for UPLC-Q/TOF MS analysis. PeakView ® V1.2 and MetabolitePilot V1.5 software from AB Sciex were used for data analysis.

4.7. In Vitro Metabolic Profiles Analysis

Pooled human liver microsomes with selective inhibitors and recombinant human CYP450 enzymes were used to identify the CYP450 isozymes responsible for the metabolism of SPH5030 in vitro [

15]. Human liver microsomal chemical inhibition assay: incubation system (100 µL) contained 0.5 mg/mL human liver microsome, 1.0 mM NADPH and various concentrations of inhibitors. After 10 min of pre-incubation, 3.0 µM SPH5030 was added to the mixture to initiate the reaction. Meanwhile, recombinant CYP450 enzyme assay were also employed to identify the metabolizing CYP450 isozymes: incubation system (100 µL) contained 3.0 µM SPH5030 and 1.0 mM NADPH was incubated at 37 ℃. After 3 min of pre-incubation, the human recombinant P450 enzymes (BD Biosciences, Woburn, MA, USA) was added to the mixture to initiate the reaction. The final concentration of each recombinant enzyme protein was 50 pmol/mL. After incubation for 60 min, both of the incubation system reaction above were stopped by adding into the same volume of ice-cold acetonitrile. After appropriate pretreatment, the supernatant was taken for UPLC-Q/TOF MS analysis.

SPH5030 was also tested for its CYP enzyme inhibition effects on marker reactions specific for CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4/5. For the reversible CYP450 inhibition assay, 5 min pre-incubation at 37 °C was needed and the reaction was initiated by the addition of NADPH (1.00 mM). For the time-dependent CYP450 inhibition assay, before probe substrates were added, 30 min of pre-incubation in the presence or absence of NADPH (1μM) was processed. The final concentration of the probe substrates and incubation time corresponding to each CYP450 isoenzyme are shown in

Table 1-2. The metabolites generated from probe substrates were detected and IC

50 was calculated by sigmoidal (logistic) fitting in Graphpad Prism (v8.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For time-dependent Inhibition assay, IC

50 shift was determined by the ratio of IC

50 values between the 30 min pre-incubation minus and plus NADPH.

For CYP450 induction assay, cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes were thawed and seeded in collagen coated 48-well cell culture plates at a density of 0.7 million viable cells/mL and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO

2. In the following two days, the cells were treated with SPH5030 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) and incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO

2, with medium change and replenishment every 24 h. After treatment, probe substrates were incubated with the cells at 37℃ for 30 min. and the metabolites formation s was detected by LC/MS/MS. Total RNA from the hepatocytes was isolated and cDNA was synthesized. The expression levels of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP3A4 and 18S (internal reference) were detected by real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR.2.5 [

16].

4.8. Transporter Mediated Interaction

Caco-2 cells purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured for 21 days in an incubator at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 and 90% relative humidity environment. Cell layers with a transepithelial electrical resistance value of > 300 Ω cm2 were used. SPH5030 (2.00, 10.0 and 50.0 μM) in HBSS containing 0.5% BSA was added to the apical side to assess permeability in the A → B direction and in the basolateral side to assess permeability in the B → A direction. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, samples were collected from both the donor and receiver sides. All incubations were performed in duplicate. The concentration of SPH5030 was measured by the LC-MS/MS method described above. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) was calculated using the equation, Papp (cm/s) = [dq/dt/C0 × A]. The efflux ratio (ER) was estimated as ER = Papp, B → A/Papp, A → B.

MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-BCRP cells were seeded into 96-Multiwell Insert Systems at 5×105/cm2 and cultured for 7 days for confluent cell monolayer formation. After washed twice, blank or inhibitor-containing transport buffer was pre-incubated with cells for 30 min. For the substrate determination, transport buffer containing SPH5030 at 10 μM was treated bidirectionally of the cell monolayer with or without selective inhibitors. For the inhibitor determination, transport buffer containing probe substrateswas treated bidirectionally of the cell monolayer with or without selective inhibitor. After 120 min incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, Samples collected from the donor and receiver side were analyzed by LC/MS/MS together with the initial dosing samples.

HEK293-OATP1B1, HEK293-OATP1B3, HEK293-OAT1, HEK293-OAT3, HEK293-OCT2, HEK293-Mock, HEK293-MATE1, HEK293-MATE2-K and HEK293-Wildtype cells were seeded into poly-D-lysine coated 96 well plate at 5×104 cells/well and cultured for 48 hours. For the substrate investigation, SPH5030 (1.00/ 10.0 µM, with or without selective inhibitors) were incubated on the transporter transfected cells for 10 minutes after the cells were washed and preincubated with transport buffer for 10 min. For the inhibitor investigation, the cells were washed and preincubated with transport buffer containing SPH5030 (0.3-50.0 µM) for 10 min (the pre-incubation time of OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 was 30 min). Following this, different concentrations of SPH5030 and probe substrates were co-incubated on the transfected cells for a certain time. All of the cells samples from substrate and inhibitor assay were then washed, lysed and taken out for LC/MS/MS analysis. Protein concentrations of the cell lysate were quantified using a BCA assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.9. Simple Allometric Scaling of Preclinical In Vivo Clearance and Volume of Distribution for Human Pharmacokinetics Prediction

Assuming a one-compartment model, simple allometric scaling [

17] was applied using mean pharmacokinetic parameters of unbound CL and unbound Vd

ss for danicamtiv from intravenous pharmacokinetic studies in mouse, rat and cynomolgus monkey, which were correlated to corresponding body weight (BW) using the power equation Y = a × BW

b, where a and b are coefficient and exponent, respectively. Least square fitting of log BW versus log Y allowed for estimates of exponents and coefficients. Rat, cynomolgus monkey and human body weights of 0.30, 3 and 60 kg, respectively, were used [

18]. Assuming a one-compartment model, the predicted t

1/2 of danicamtiv in human was calculated using the predicted pharmacokinetic parameters (t

1/2 = V

ss × 0.693/CL) [

19].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xia G.; methodology, Xu J.; software, Gong X.; validation, Zhang Z. and Li L.; formal analysis, Xu J.; investigation, , Gu Y., Xu J. and Ding S.; resources, Li D. and Gong W.; data curation, Gu Y. and Xu J.; writing—original draft preparation, Gu Y.; writing—review and editing, Gong X. and Xia G.; visualization, Gong X.; supervision, Xia G. and Zhang Z.; project administration, Gong W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”