Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. General Experimental Procedures

2.3. Extraction and Isolation

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC)

2.5. Determination of Total Flavonoids Compounds (TFC)

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

2.6.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.6.3. ABTS Assay

2.7. Antitumoral Activity

2.7.1. Cell Culture

2.7.2. Cell Viability Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

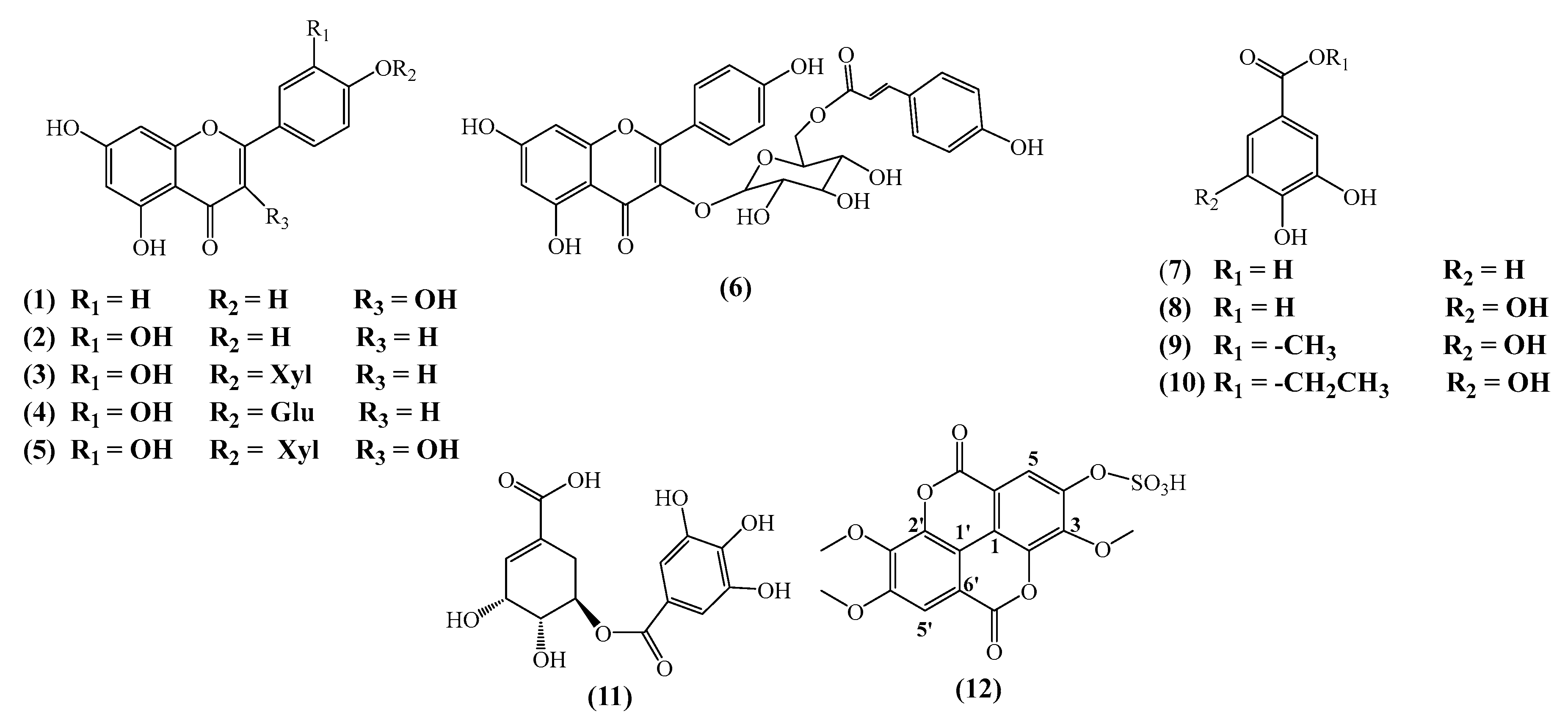

3.1. Phytochemical Study

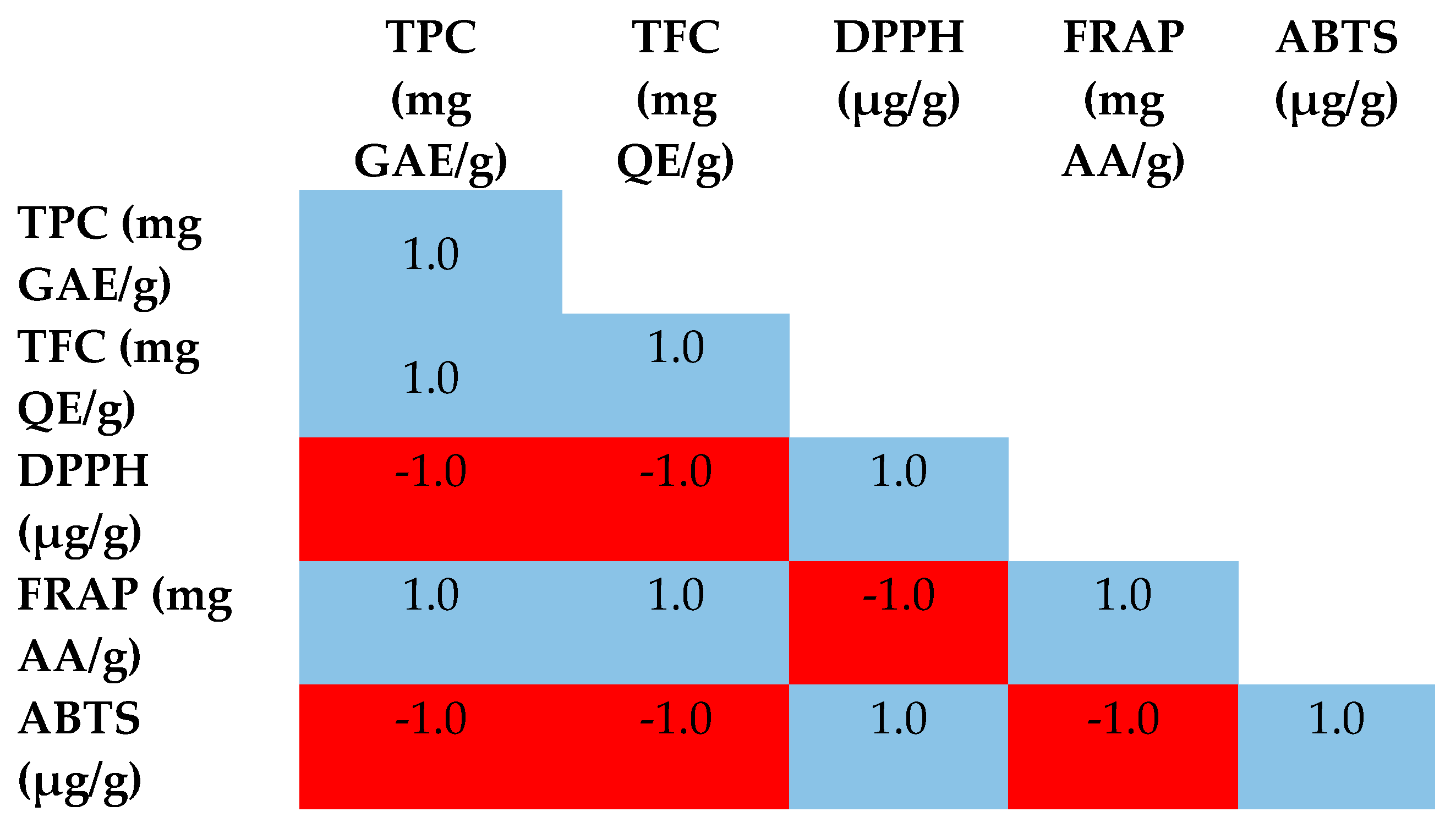

3.2. Total Phenolic and Flavonoids Contents

3.3. Antioxidant Activities

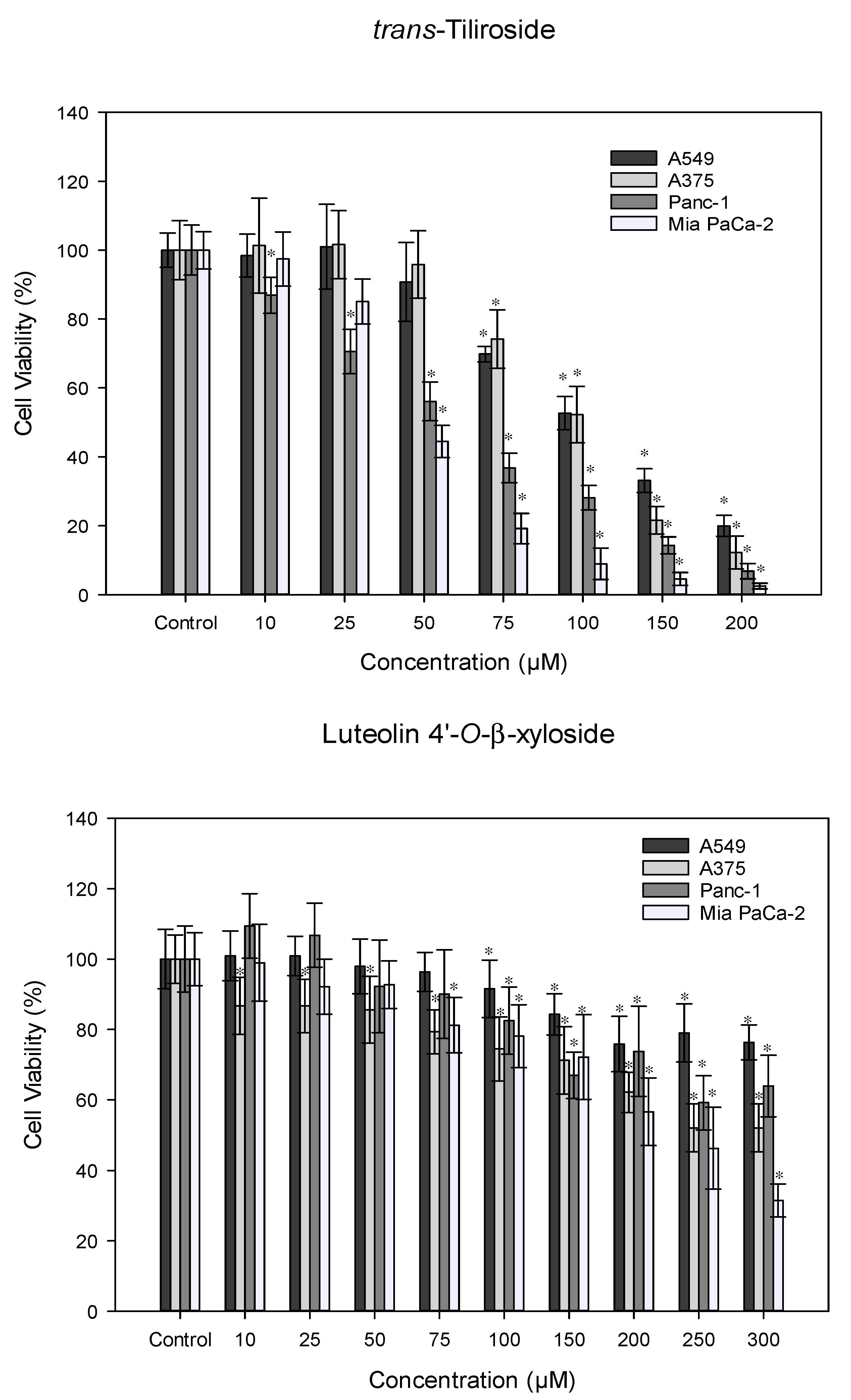

3.4. Antitumor Activity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J.M. Arrington and K. Kubitzki Flowering Plants · Dicotyledons; Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Ed.; Springer, 2003.

- Albaladejo, R.G.; Martín-Hernanz, S.; Reyes-Betancort, J.A.; Santos-Guerra, A.; Olangua-Corral, M.; Aparicio, A. Reconstruction of the Spatio-Temporal Diversification and Ecological Niche Evolution of Helianthemum (Cistaceae) in the Canary Islands Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing Data. Ann Bot 2021, 127, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabberly, D.J. The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants; Cambridge University press. England, 1997.

- Başlar, S.; Doǧan, Y.; Mert, H.H. A Study on the Soil-Plant Interactions of Some Cistus L. Species Distributed in West Anatolia. Turk J Botany 2002, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, O.; Gurbuz, I.; Kusmenoglu, S.; Turkoz, S. Fatty Acid Content of Three Cistus Species Growing in Turkey. Chem Nat Compd 2004, 40, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, Y.L. Phylogenetic Distribution and Evolution of Mycorrhizas in Land Plants. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 299–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-moraga, Á.; Argandoña, J.; Mota, B.; Pérez, J.; Verde, A. Screening for Polyphenols, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Extracts from Eleven Helianthemum Taxa ( Cistaceae ) Used in Folk Medicine in South-Eastern Spain. J Ethnopharmacol 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quézel, P.; Santa, S. Nouvelle Flore de l’Algérie et Des Régions Désertiques Méridionales. In; 1962; p. 502.

- Mouffouk, S.; Mouffouk, C.; Mouffouk, S.; Haba, H. Medicinal, Pharmacological and Biochemical Progress on the Study of Genus Helianthemum: A Review. Curr Chem Biol 2023, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemam, N.; Lassed, S.; Gül, F.; Altun, M.; Monteiro, M.; Menezes-Pinto, D.; Benayache, S.; Benayache, F.; Zama, D.; Demirtas, I.; et al. Characterization of Ethyl Acetate and N-Butanol Extracts of Cymbopogon Schoenanthus and Helianthemum Lippii and Their Effect on the Smooth Muscle of the Rat Distal Colon. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 252, 112613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdelaziz, I.; Haba, H.; Lavaud, C.; Harakat, D.; Benkhaled, M. Lignans and Other Constituents from Helianthemum Sessiliflorum Pers. Records of Natural Products 2015, 9, 342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Benabdelaziz, I.; Marcourt, L.; Benkhaled, M.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Haba, H. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities and Polyphenolic Constituents of Helianthemum Sessiliflorum Pers. Nat Prod Res 2017, 31, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzergoune, F.; Bitam, F.; Aberkane, M.C.; Mosset, P.; Fetha, M.N.H.; Boudjar, H.; Aberkane, A. Preliminary Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Activity Investigations on the Aerial Parts of Helianthemum Kahiricum. Chem Nat Compd 2013, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemam, Y.; Benayache, S.; Marchioni, E.; Zhao, M.; Mosset, P.; Benayache, F.; McPhee, D.J. On-Line Screening, Isolation and Identification of Antioxidant Compounds of Helianthemum Ruficomum. Molecules 2017, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terfassi, S.; Dauvergne, X.; Cérantola, S.; Lemoine, C.; Bensouici, C.; Fadila, B.; Christian, M.; Marchioni, E.; Benayache, S. First Report on Phytochemical Investigation, Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Activities of Helianthemum Getulum. Nat Prod Res 2022, 36, 2806–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassila, B. Constituants Chimiques Des Espèces Helianthemum Hirtum Ssp. Ruficomum (Cistaceae) et Onobrychis Crista-Galli (Fabaceae), Batna 1, 2020.

- Barbosa, E.; Calzada, F.; Campos, R. Antigiardial Activity of Methanolic Extracts from Helianthemum Glomeratum Lag. and Rubus Coriifolius Focke in Suckling Mice CD-1. J Ethnopharmacol 2006, 108, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, T.; Gerhard Gul, P. Accumulation of Flavonoids during Leaf Development in Cistus Laurifolius. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Yin, S.; Liu, M.; Kong, J.Q. Isolation and Characterization of a Multifunctional Flavonoid Glycosyltransferase from Ornithogalum Caudatum with Glycosidase Activity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawwar, M.A.M.; Hussein, S.A.M.; Merfort, I. Leaf Phenolics of Punica Granatum. Phytochemistry 1994, 37, 1175–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambor, J.; Skrzypczak, L. Flavonoids from the Flowers of Nymphaea Alba L. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 1991, 60, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Lopéz, R.; Meckes, M.; Cedillo-Rivera, R. Flavonoids of the Aerial Parts of Helianthemum Glomeratum. International Journal of Pharmacognosy 1995, 33, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toan Phan, N.H.; Dieu Thuan, N.T.; Duy, N. Van; Mai Huong, P.T.; Cuong, N.X.; Nam, N.H.; Thanh, N. Van; Minh, C. Van Flavonoids Isolated from Dipterocarpus Obtusifolius. Vietnam Journal of Chemistry 2015, 53, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.J.; Guan, S.; Shi, G.F.; Bao, Y.M.; Duan, Y.L.; Jiang, B. Protocatechuic Acid from Alpinia Oxyphylla against MPP+-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2006, 44, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudermine, S.; Malafronte, N.; Mencherini, T.; Esposito, T.; Aquino, R.P.; Beghidja, N.; Benayache, S.; D’Ambola, M.; Vassallo, A. Phenolic Compounds from Limonium Pruinosum. Nat Prod Commun 2015, 10, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooshiro, A.; Hiradate, S.; Kawano, S.; Takushi, T.; Fujii, Y.; Natsume, M.; Abe, H. Identification and Activity of Ethyl Gallate as an Antimicrobial Compound Produced by Geranium Carolinianum. Weed Biol Manag 2009, 9, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gen-Ichiro Nonaka, Masayuki Ageta, and I. N. Tannins and Related Compounds. XXV. A New Class of Gallotannins Possessing a (-)-Shikimic Acid Core from Castanopsis Cuspidata Var. Sieboldii NAKAI. (1). Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1985, 33, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manurung, J.; Kappen, J.; Schnitzler, J.; Frolov, A.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Agusta, A.; Muellner-Riehl, A.N.; Franke, K. Analysis of Unusual Sulfated Constituents and Anti-Infective Properties of Two Indonesian Mangroves, Lumnitzera Littorea and Lumnitzera Racemosa (Combretaceae). Separations 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, A.; Rózalski, M.; Krajewska, U.; Olszewska, M.A. Rare Ellagic Acid Sulphate Derivatives from the Rhizome of Geum Rivale L.-Structure, Cytotoxicity, and Validated HPLC-PDA Assay. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Lorente, F.; Garcia-Grau, M.M.; Nieto, J.L.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Flavonoids from Cistus Ladanifer Bee Pollen. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 2027–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B. Flavonoid Bisulphates and Their Co-Occurrences with Ellagic Acid in the Bixaceae, Frankeniaceae and Related Families. Phytochemistry 1975, 14, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B. Flavonoid Sulphates: A New Class of Sulphur Compounds in Higher Plants. Phytochemistry 1975, 14, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraoui, H.; Haba, H.; Long, C.; Benkhaled, M. A New Flavanone Sulfonate and Other Phenolic Compounds from Fumana Montana. Biochem Syst Ecol 2019, 86, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobrattee, M.A.; Neergheen, V.S.; Luximon-Ramma, A.; Aruoma, O.I.; Bahorun, T. Phenolics as Potential Antioxidant Therapeutic Agents: Mechanism and Actions. Mutation Research - Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2005, 579, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Phenolic Compounds: Structure, Classification, and Antioxidant Power. Bioactive Compounds: Health Benefits and Potential Applications, 2019; 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldemir, A.; Gökşen, N.; Ildız, N.; Karatoprak, G.Ş.; Koşar, M. Phytochemical Profile and Biological Activities of Helianthemum Canum l. Baumg. from Turkey. Chem Biodivers 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Albu, C.; Alecu, A.; Seciu-Grama, A.M.; Radu, G.L. Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Activity of Cornus Mas L. and Crataegus Monogyna Fruit Extracts. Molecules 2024, 29, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, M.A.; Khong, H.Y. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Pereskia Bleo. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menyhárt, O.; Harami-Papp, H.; Sukumar, S.; Schäfer, R.; Magnani, L.; de Barrios, O.; Győrffy, B. Guidelines for the Selection of Functional Assays to Evaluate the Hallmarks of Cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2016, 1866, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Zhong, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, M.; Yuan, X.; Lu, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Tiliroside Disrupted Iron Homeostasis and Induced Ferroptosis via Directly Targeting Calpain-2 in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Phytomedicine 2024, 127, 155392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.H.; Chen, J.; Wei, D.Z.; Wang, Z.T.; Tao, X.Y. Tyrosinase Inhibitory Effect and Inhibitory Mechanism of Tiliroside from Raspberry. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2009, 24, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomberg, J.; Wang, Z.; Farhat, A.; Guo, K.L.; Xie, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Kovacs, B.; Liu-Smith, F. Luteolin Inhibits Melanoma Growth in Vitro and in Vivo via Regulating ECM and Oncogenic Pathways but Not ROS. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 177, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, G.; Ren, D.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Q.; Sun, X. Luteolin Suppresses Growth and Migration of Human Lung Cancer Cells. Mol Biol Rep 2011, 38, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Q.; Li, M.H.; Qin, Y.M.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.H. Luteolin Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Induces Apoptosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells via Regulation of MicroRNA-34a-5p. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dai, S.; Dai, J.; Xiao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. Luteolin Decreases Invasiveness, Deactivates STAT3 Signaling, and Reverses Interleukin-6 Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Matrix Metalloproteinase Secretion of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Onco Targets Ther 2015, 8, 2989–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.C.; Canellas, E.; Asensio, E.; Nerín, C. Predicting the Antioxidant Capacity and Total Phenolic Content of Bearberry Leaves by Data Fusion of UV–Vis Spectroscopy and UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS. Talanta 2020, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amzad Hossain, M.; Shah, M.D. A Study on the Total Phenols Content and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oil and Different Solvent Extracts of Endemic Plant Merremia Borneensis. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2015, 8, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.; Nerín, C.; Alfonso, M.J.; Caballero, M.Á. Antioxidant Packaging with Encapsulated Green Tea for Fresh Minced Meat. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2017, 41, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabid, K.; Lamchouri, F.; Toufik, H.; Faouzi, M.E.A. Phytochemical Investigation, in Vitro and in Vivo Antioxidant Properties of Aqueous and Organic Extracts of Toxic Plant: Atractylis Gummifera L. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Huang, Z.; Liang, G.; Bi, Y.; Kong, F.; Wang, Z.; Tan, S.; Zhang, J. Preparation of Protein-Stabilized Litsea Cubeba Essential Oil Nano-Emulsion by Ultrasonication: Bioactivity, Stability, in Vitro Digestion, and Safety Evaluation. Ultrason Sonochem 2024, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extracts | TPC (mg GAE/g) * | TFC (mg QE/g) ** |

|---|---|---|

| H. cinereum EtOAc | 361.51 ± 0.84 a | 148.23 ± 0.51 a |

| H. cinereum BuOH | 145.88 ± 0.63 b | 94.89 ± 0.29 b |

| Samples | DPPH (IC50 µg/g) ** | FRAP (mg AA/g) * | ABTS (IC50 µg/g) ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. cinereum EtOAc | 17.23 ± 0.36 a | 221.16 ± 1.03 a | 85.16 ± 1.03 a |

| H. cinereum BuOH | 24.39 ± 0.21 b | 44.69 ± 0.64 b | 121.16 ± 1.03 b |

| Trolox | 11.97 ± 0.41 | - | 23.16 ± 0.54 |

| Ascorbic acid | 3.36 ± 0.13 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).