Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

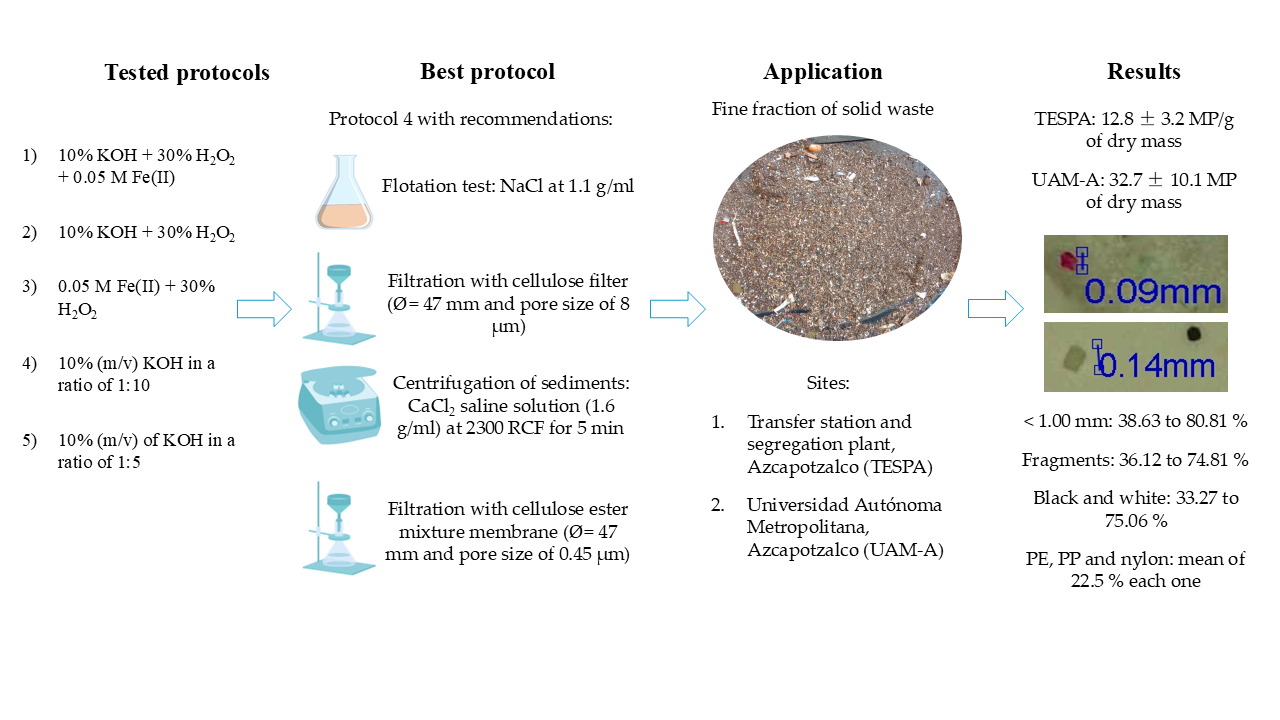

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Contamination Prevention

2.2. Description of Five Protocols for Microplastics Extraction

2.3. Application of the Best Protocol

2.3.1. Study Sites

2.3.2. Obtaining Samples of Thin Waste

2.3.3. Extraction of Microplastics

2.3.4. Microplastics Classification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Five Protocols

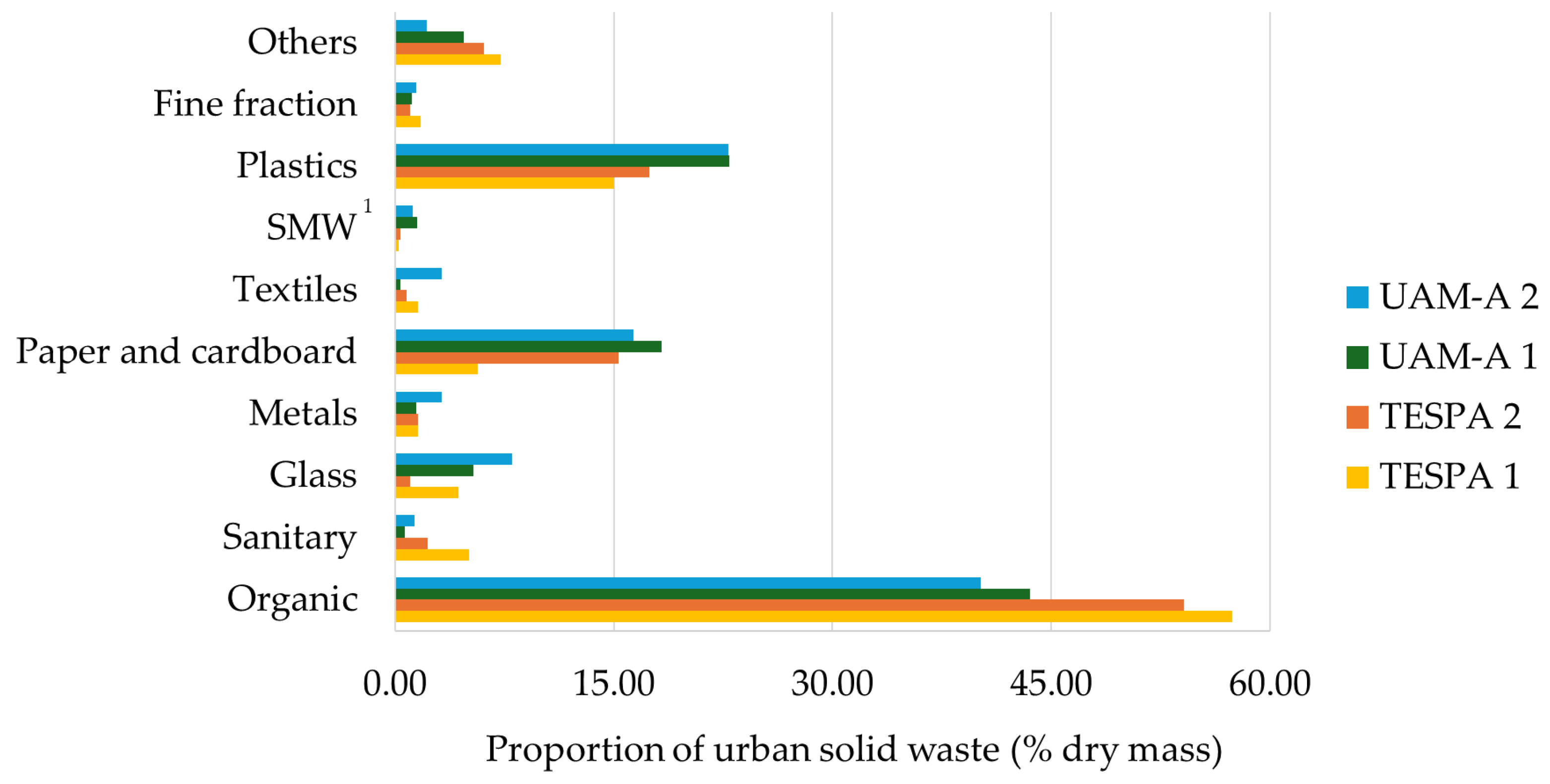

3.2. Classification of Urban Solid Waste

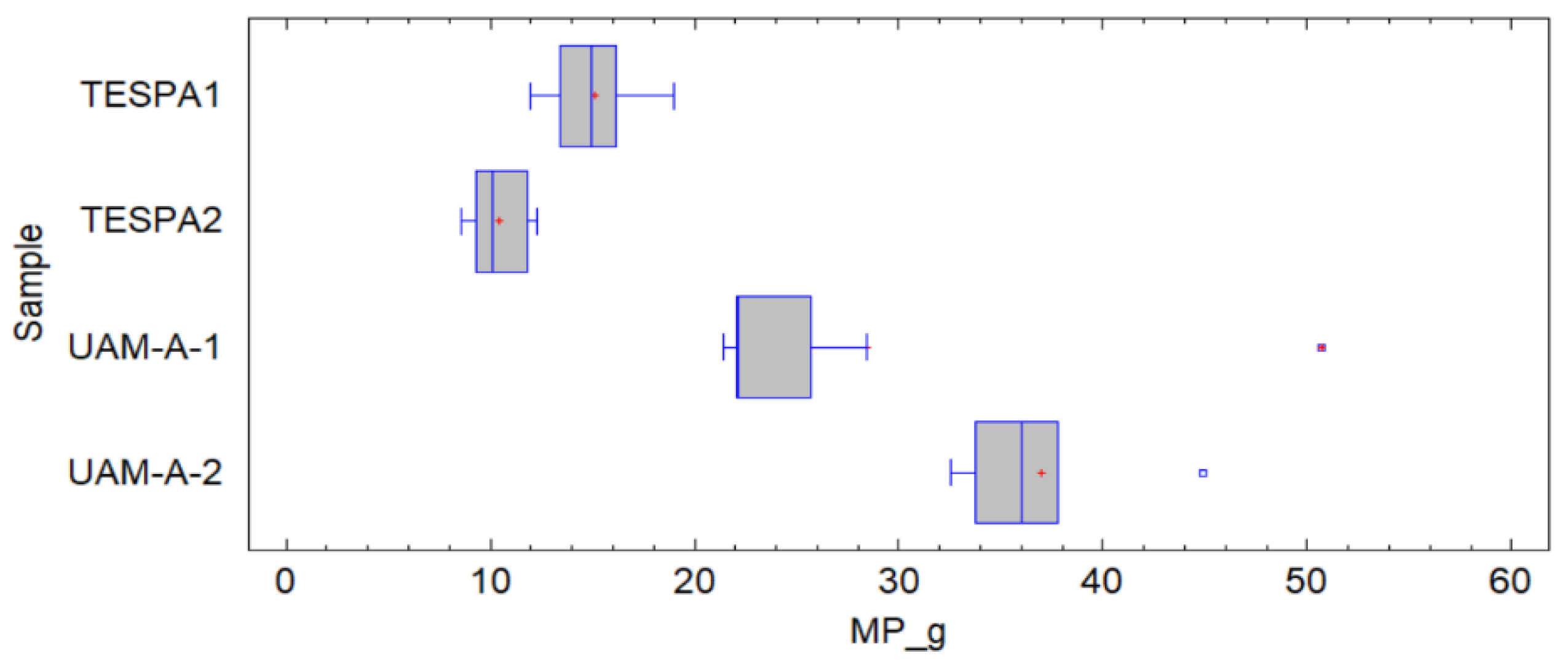

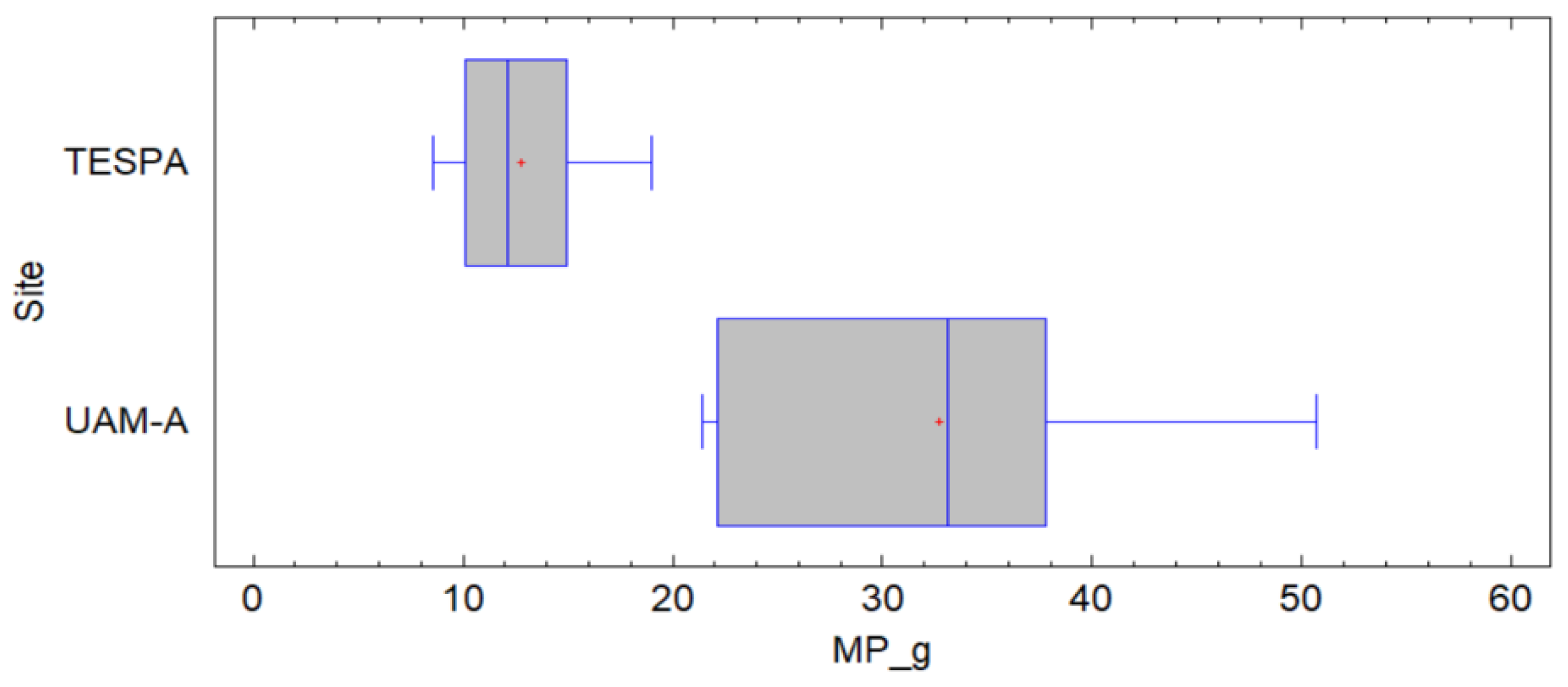

3.3. Abundance, Characteristics and Statistial Analysys of Microplastics in Fine Fraction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Y. Chae and Y. J. An, “Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. B. Borrelle et al., “Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, and K. L. Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binelli, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Hazard evaluation of plastic mixtures from four Italian subalpine great lakes on the basis of laboratory exposures of zebra mussels. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Avio et al., “Distribution and characterization of microplastic particles and textile microfibers in Adriatic food webs: General insights for biomonitoring strategies. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Andrady, “Microplastics in the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. U. Benson, O. D. Agboola, O. H. Fred-Ahmadu, G. E. De-la-Torre, A. Oluwalana, and A. B. Williams, “Micro(nano)plastics Prevalence, Food Web Interactions, and Toxicity Assessment in Aquatic Organisms: A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 851281. [Google Scholar]

- S. M. Bashir, S. Kimiko, C. W. Mak, J. K. H. Fang, and D. Gonçalves, “Personal Care and Cosmetic Products as a Potential Source of Environmental Contamination by Microplastics in a Densely Populated Asian City. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 683482. [Google Scholar]

- P. Rawat and S. Mohanty, “Potential Use of Fine Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste as Replacement of Soil in Embankment. in Soil Dynamics, Earthquake and Computational Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 300, K. Muthukkumaran, R. Ayothiraman, and S. Kolathayar, Eds. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, pp. 183–192.

- Amobonye, P. Bhagwat, S. Raveendran, S. Singh, and S. Pillai, “Environmental Impacts of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: A Current Overview. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 768297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kaza, L. S. Kaza, L. Yao, P. Bhada-Tata, and F. Van Woerden, “What a Waste 2.0. A global snapshot of solid waste management to 2050. Washington, DC, 2018. Accessed: Oct. 09, 2019. [Online]. Available online: http://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/tackling_increasing_plastic_waste.html.

- M. Yatoo et al., “Global perspective of municipal solid waste and landfill leachate: generation, composition, eco-toxicity, and sustainable management strategies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 23363–23392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Mohanan, Z. Montazer, P. K. Sharma, and D. B. Levin, “Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580709. [Google Scholar]

- Peydaei, H. Bagheri, L. Gurevich, N. de Jonge, and J. L. Nielsen, “Impact of polyethylene on salivary glands proteome in Galleria melonella. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2020, 34, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Hopewell, R. Dvorak, and E. Kosior, “Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Rawat and S. Mohanty, “Parametric Study on Dynamic Characterization of Municipal Solid Waste Fine Fractions for Geotechnical Purpose. J. Hazardous, Toxic, Radioact. Waste 2022, 26, 04021047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Palovčík, J. Jadrný, V. Smejkalová, B. Šmírová, and R. Šomplák, “Evaluation of properties and composition of the mixed municipal waste fine fraction, the case study of Czech Republic. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. C. Hernández Parrodi, D. Höllen, and R. Pomberger, “Characterization of fine fractions from landfill mining: A review of previous investigations. Detritus 2018, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Somani, M. Datta, G. V. Ramana, and T. R. Sreekrishnan, “Investigations on fine fraction of aged municipal solid waste recovered through landfill mining: Case study of three dumpsites from India. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Gyabaah, E. Awuah, P. Antwi-Agyei, and R. A. Kuffour, “Physicochemical properties and heavy metals distribution of waste fine particles and soil around urban and peri-urban dumpsites. Environ. Challenges 2023, 13, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMARNAT – Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, “Informe de la situación del medio ambiente en México. 2015. [Online]. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/informe15/tema/pdf/Informe15_completo.pdf.

- Cruz-Salas, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Measures to prevent cross-contamination in the analysis of microplastics: A short literature review. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2023, 39, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Cruz-Salas et al., “Presence of Microplastics in the Vaquita Marina Protection Zone in Baja California, Mexico. Microplastics 2023, 2, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. B. Alfonso, K. Takashima, S. Yamaguchi, M. Tanaka, and A. Isobe, “Microplastics on plankton samples: Multiple digestion techniques assessment based on weight, size, and FTIR spectroscopy analyses. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Wang et al., “Coastal zone use influences the spatial distribution of microplastics in Hangzhou Bay, China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Teng et al., “A systems analysis of microplastic pollution in Laizhou Bay, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. A. Rahman, G. S. Robin, M. Momotaj, J. Uddin, and M. A. M. Siddique, “Occurrence and spatial distribution of microplastics in beach sediments of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Ferreira, J. Thompson, A. Paris, D. Rohindra, and C. Rico, “Presence of microplastics in water, sediments and fish species in an urban coastal environment of Fiji, a Pacific small island developing state. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 153, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. A. Littman et al., “Coastal urbanization influences human pathogens and microdebris contamination in seafood. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisling, R. D. Harris, J. Blaze, J. Coffin, and J. E. Byers, “Low concentrations and low spatial variability of marine microplastics in oysters (Crassostrea virginica) in a rural Georgia estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Narmatha Sathish, K. Immaculate Jeyasanta, and J. Patterson, “Monitoring of microplastics in the clam Donax cuneatus and its habitat in Tuticorin coast of Gulf of Mannar (GoM), India. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kazour and R. Amara, “Is blue mussel caging an efficient method for monitoring environmental microplastics pollution? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 135649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Goswami, N. V. Vinithkumar, and G. Dharani, “First evidence of microplastics bioaccumulation by marine organisms in the Port Blair Bay, Andaman Islands. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 155, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. S. Robin et al., “Holistic assessment of microplastics in various coastal environmental matrices, southwest coast of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Zheng et al., “Characteristics of microplastics ingested by zooplankton from the Bohai Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. N. Sathish, I. Jeyasanta, and J. Patterson, “Occurrence of microplastics in epipelagic and mesopelagic fishes from Tuticorin, Southeast coast of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. M. Espinosa-Valdemar, B. A. García-García, R. C. Vázquez-Solís, A. de la L. Cisneros-Ramos, A. Vázquez-Morillas, and M. Velasco-Pérez, “Waste generation and composition in a mexican public university. Am. J. Environ. Eng. 2013, 3, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- J. Navarrete-Contreras, “Análisis de la composición y eficiencia de separación de los residuos sólidos urbanos de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Azcapotzalco. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, unidad Azcapotzalco, 2024.

- SOBSE - Secretaría de Obras y Servicios de la Ciudad de México, “Estación de transferencia y planta de selección Azcapotzalco.” [Online]. Available online: https://www.obras.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/00025 julio planta/250721estacion-de-transferencia-y-planta-de-seleccion-azcvf-4.pdf.

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México, “Estación de Transferencia y Planta de Selección Azcapotzalco, la más moderna de América Latina: Sheinbaum Pardo. 2021. Available online: https://www.jefaturadegobierno.cdmx.gob.mx/comunicacion/nota/estacion-de-transferencia-y-planta-de-seleccion-azcapotzalco-la-mas-moderna-de-america-latina-sheinbaum-pardo (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- SECOFI - Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial, “Norma Mexicana NMX-AA-61-1985, Protección al Ambienten - Contaminación Del Suelo - Residuos Sólidos Municipales - Determinación de la Generación.” 1985.

- SECOFI - Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial, “Norma Mexicana NMX-AA-015-1985. Protección al Ambiente - Contaminación del Suelo - Residuos Sólidos Municipales - Muestreo -Método de Cuarteo.” 1985.

- SECOFI - Secretaría de Comercio y Fomento Industrial, “Norma Mexicana NMX-AA-022-1985 Protección al Ambiente - Contaminación del Suelo - Residuos Sólidos Municipales - Selección y Cuantificación de Subproductos.” 1985.

- WtERT - Waste to Energy Research Technology, “Nationwide study of municipal residual waste to determine the proportion of problematic substances and recyclable materials. 2024. Available online: https://www.wtert.net/bestpractice/525/Nationwide-study-of-municipal-residual-waste-to-determine-the-proportion-of-problematic-substances-and-recyclable-materials.html (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Y. Ding et al., “A review of China’s municipal solid waste (MSW) and comparison with international regions: Management and technologies in treatment and resource utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. V. Ramachandra, H. A. Bharath, G. Kulkarni, and S. S. Han, “Municipal solid waste: Generation, composition and GHG emissions in Bangalore, India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. E. Edjabou et al., “Municipal solid waste composition: Sampling methodology, statistical analyses, and case study evaluation. Waste Manag. 2015, 36, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMARNAT - Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, “Diagnóstico Básico para la Gestión Integral de los Residuos. Ciudad de México, 2020. Accessed: Sep. 30, 2020. [Online]. Available: www.gob.mx/inecc.

- V. Jahagirdar, A. K. V. Jahagirdar, A. K. Mishra, and A. S. Kalamdhad, “Exploring the Fine Fraction from Landfill Mining: A Comprehensive Case Study of the Boragaon Dump Site in Guwahati, India. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Mönkäre, M. R. T. Palmroth, and J. A. Rintala, “Characterization of fine fraction mined from two Finnish landfills. Waste Manag. 2016, 47, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh and M., K. Chandel, “Physicochemical and FTIR spectroscopic analysis of fine fraction from a municipal solid waste dumpsite for potential reclamation of materials. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X20962844 2020, 39, 374–385.

- S. Keber, T. Schirmer, T. Elwert, and D. Goldmann, “Characterization of Fine Fractions from the Processing of Municipal Solid Waste Incinerator Bottom Ashes for the Potential Recovery of Valuable Metals. Miner. 2020, Vol. 10, Page 838, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 838, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Lakshmikanthan, L. G. P. Lakshmikanthan, L. G. Santhosh, and G. L. Sivakumar Babu, “Evaluation of Bioreactor Landfill as Sustainable Land Disposal Method. pp. 243–254, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq and J., L. Xu, “Microplastics in waste management systems: A review of analytical methods, challenges and prospects. Waste Manag. 2023, 171, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Okori, J. Lederer, A. J. Komakech, T. Schwarzböck, and J. Fellner, “Plastics and other extraneous matter in municipal solid waste compost: A systematic review of sources, occurrence, implications, and fate in amended soils. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, F. Fernández-Piñas, and R. Rosal, “Microplastics identification and quantification in the composted Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 151902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protocol | Oxidant | Conditions | Filtration | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 1 | Step 1: 10% KOH Step 2: 30% H2O2 Step 3: 0.05 M Fe(II) |

Mass of sample: 50 g. Step 1: 40 ° C 24 h Step 2: 40 mL 3 times every 20 min at 60 ° C Stage 3: 40 mL once |

Vacuum on cellulose filter (Ø= 47 mm and pore size of 8 μm) | Stirring for 10 seconds when adding each reagent | [24] |

| Protocol 2 | 180 mL of 10% KOH plus 20 mL of 30% H2O2 | Mass of sample: 50 g. 60 °C for 24 h with stirring every 6 or 8 h |

Vacuum on cellulose filter (Ø= 47 mm and pore size of 8 μm) | Covering the sample with aluminum foil and stirring with a glass rod | [25,26] |

| Protocol 3 | 20 mL of 0.05 M Fe(II) plus 20 mL of 30%H2O2 |

Mass of sample: 50 g. Room temperature for 5 min and then 75 °C for 30 min with stirring with magnetic bar |

After flotation: vacuum on cellulose filter (Ø= 47 mm and pore size of 8 μm) | The sample was sieved with 3 and 5 mm mesh. After digestion, the sample was subjected to flotation with saturated NaCl with stirring for 2 min with a glass rod and rest for 24 h | [27,28] |

| Protocol 4 | 10% (m/v) KOH in a ratio of 1:10 (sample mass: solution volume) | Mass of sample: 10 g. 40 °C for 72 h (until the presence of a clear solution, without traces of organic matter) |

After digestion: vacuum on a cellulose filter (Ø= 47 mm and pore size of 8 μm). | During digestion, the sample was stirred once a day with a glass rod, rinsed with deionized water before and after, and dried with adsorbent paper. After the first filtration, the filter paper with the sample was rinsed with deionized water |

[29,30,31] |

| Protocol 5 | 10% (m/v) of KOH in a ratio of 1:5 (sample mass: solution volume) | Mass of sample: 62 g. 60 °C for 24 h (with stirring) |

Vacuum on cellulose filter (Ø= 47 mm and pore size of 8 μm) | Heating on a grill and stirring with a magnetic bar | [32,33,34,35,36] |

| Category | Type of waste | Category | Type of waste |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic | Food waste | Paper and cardboard | Paper |

| Pruning waste | Cardboard | ||

| Napkins and sanitary paper | Tetra Pak | ||

| Sanitary | Disposable nappies | Textiles | Textiles |

| Sanitary towels | Special management waste (SMW) | Potentially hazardous | |

| Other sanitary | Construction | ||

| Glass | All types of glass | Plastics | All plastics |

| Metals | Aluminum cans | Others | Wood |

| Other cans | Semi-fine fraction | ||

| Other metals | Fine fraction | ||

| Other |

| Protocol | Degradation of organic matter | Virgin MP recovery percentage | Other comments | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 1 | After 24 h, the sample was not completely digested. | It could not be calculated | When adding H2O2 there was a significant loss of sample due to the fact that it spilled. Filtration was not possible |

Protocol not suitable for digestion of organic matter |

| Protocol 2 | After 24 hours of treatment, organic matter was still observed, and the sample was too thick | It could not be calculated | Filtering to retrieve virgin MP could not be performed | Protocol not suitable for digestion of organic matter |

| Protocol 3 | After 20 min, the sample was not completely digested, but much of the matter was destroyed | It could not be calculated | When H2O2 was added, there was a large amount of foam. The treatment did not last 30 min, since after 20 min the reagents had already evaporated, and the entire sample adhered to the glass |

Protocol moderately suitable for the digestion of organic matter |

| Protocol 4 | After digestion the sample had a good degradation | 100%, no color changes or presence of cracks | The filters were clearly visible as there was very little presence of organic matter. However, flotation tests with NaCl (1.1 g/ml) and centrifugation with CaCl2 (1.6 g/ml) and at a higher speed are recommended | Proper protocol |

| Protocol 5 | The sample changed color, but did not degrade | It could not be calculated | Filtration was not possible because the organic matter had not degraded | Protocol not suitable for digestion of organic matter |

| Site | Mean ± standard deviation | % Variance | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| TESPA 1 | 15.1 ± 2.7 | 17.8 | 14.9 |

| TESPA 2 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 15.4 | 10.1 |

| UAM-A 1 | 28.4 ± 12.6 | 44.2 | 22.2 |

| UAM-A 2 | 36.9 ± 4.8 | 13.2 | 36.0 |

| Site | Mean ± standard deviation | % Variance | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| TESPA | 12.8 ± 3.2 | 25.4 | 12.1 |

| UAM-A | 32.7 ± 10.1 | 30.8 | 33.1 |

| Region or country | Category of waste | % in weight | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Fine waste (0 – 10 mm) | 6.3 of household waste | [44] |

| China’s eastern coastal regions | Dust | 0.0 – 15.27 of municipal solid waste | [45] |

| Bangalore, India | Dust and sweeping | 6.53, average of domestic, markets, trade, slums and street sweeping | [46] |

| Three municipalities in Denmark | Gravel, stones and sand | 0.3 – 0.2 of residual waste | [47] |

| Mexico | Fine waste (< 2 mm) | 2.25 of urban solid waste | [48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).