1. Introduction

Microplastic (MP) pollution, defined as plastic particles measuring ≤ 5 mm, is an emerging environmental concern affecting diverse ecosystems and organisms. Depending on their origin, MPs are classified as primary, intentionally manufactured at this size, or secondary, resulting from the fragmentation of larger plastic debris. These pollutants have been detected in a wide range of environmental matrices, including marine, terrestrial, and urban ecosystems, as well as in numerous species, from marine organisms to terrestrial birds and mammals (Weitzel et al., 2021; Sherlock et al., 2022).

Although much research on MPs has focused on marine environments, terrestrial and urban ecosystems exhibit unique dynamics that influence the distribution, degradation, and exposure to these pollutants. In urban settings, MPs primarily originate from anthropogenic activities such as vehicular traffic, construction waste, and improper solid waste management. Urban birds, due to their opportunistic feeding habits and proximity to human activities, are continually exposed to MPs. This behavior often leads to the ingestion of plastic particles mistaken for food, potentially causing adverse physiological effects and disrupting urban ecosystem balance (Carlen et al., 2021; Tokunaga et al., 2023).

Previous studies have documented the harmful impacts of MPs on birds, including organ inflammation, reproductive disruptions, and malnutrition, highlighting the urgent need to understand these interactions. However, most of this research has been conducted on seabirds, leaving a gap in knowledge about how MPs affect urban species. The domestic pigeon (Columba livia), widely distributed in cities, serves as an ideal model to study MP pollution in urban environments due to its feeding behavior, close association with humans, and availability for non-invasive sampling through fecal analysis.

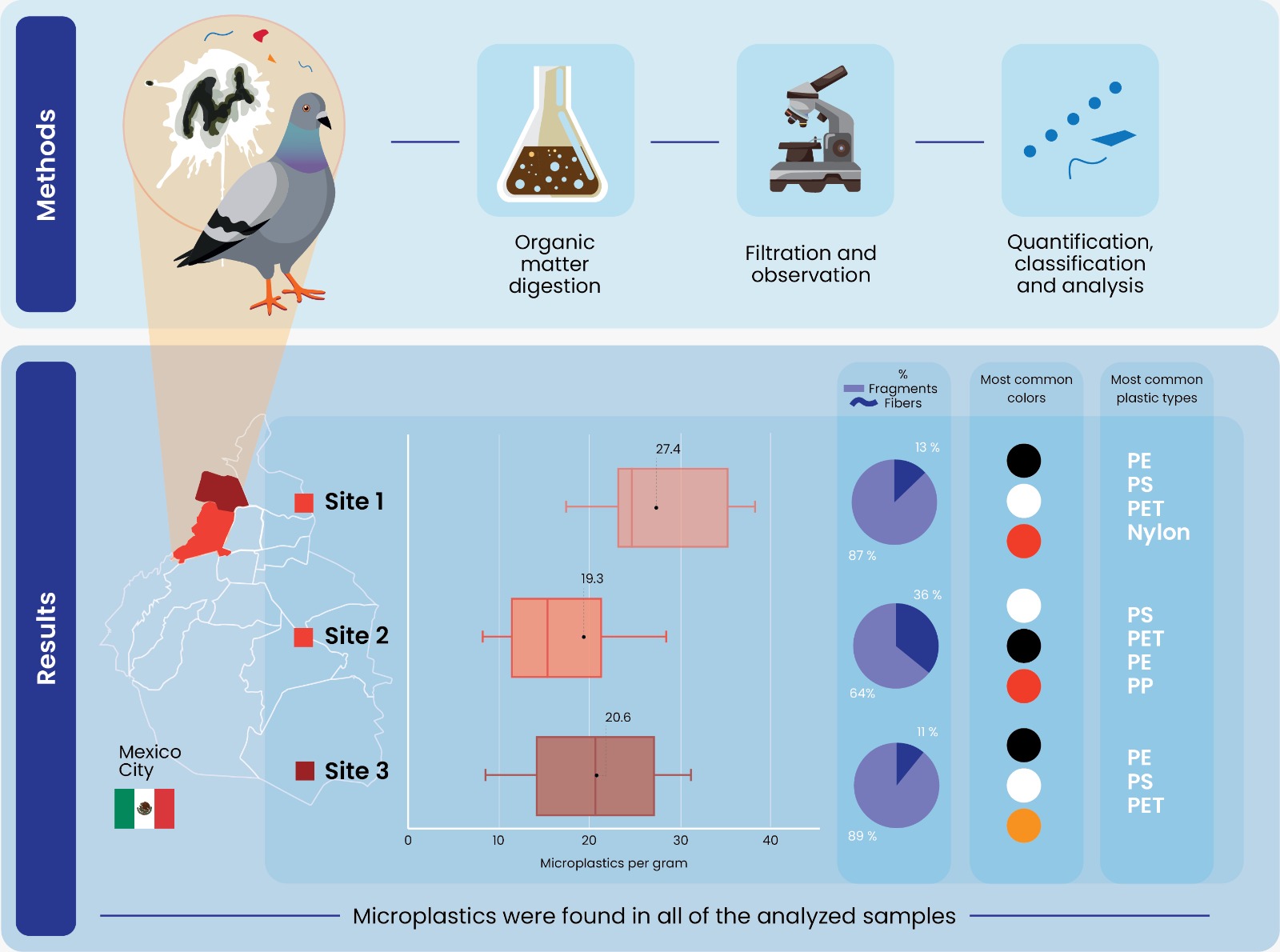

In this context, the present study aimed to develop and apply an efficient methodology to assess the presence of MPs in the feces of urban pigeons (Columba livia) from three representative sites in Mexico City. By doing so, this research seeks to enhance our understanding of plastic pollution in urban environments, identify potential MP sources, and evaluate the utility of urban birds as bioindicators of this contamination.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the sampling of bird feces, the extraction and characterization of microplastics, and the statistical analysis for the three areas studied.

2.1. Contamination Prevention

To ensure the integrity of the samples and prevent cross-contamination from airborne plastic particles, strict protocols were implemented throughout the analysis. These measures included wearing cotton laboratory coats, exclusively using glass and metal equipment, pre-washing all materials with deionized water and ethanol, and oven-drying them prior to use. The workspace was thoroughly cleaned with absorbent paper and ethanol, and blanks were incorporated during sample processing to monitor potential contamination. Furthermore, a laminar flow hood was utilized for critical steps, including digestion and filtration, to minimize exposure to external plastic particles. This rigorous protocol ensured reliable data and reduced the risk of contamination artifacts. (Cruz-Salas, 2023).

2.2. Sites Studied

Site 1. It is a passenger public transport truck parking lot. Around it is a park, informal trade stalls, and street vendors. A market is located a few meters across an avenue. There is a large influx of people, pigeons live under the bridge (

Figure 1a).

Site 2. It is a closed street where pigeons come down to eat in the surrounding houses; the pigeons live on the roofs, balconies and windowsills (

Figure 1b).

Site 3. The train workshop is part of the Metro Collective Transport System (STC) of México City. There are various businesses around the site and a bus terminal. Pigeons take shelter in the beams of the workshop roof (

Figure 1c).

2.3. Extraction of Microplastics

Ten feces samples were collected from each site, taking precautions to avoid cross-contamination. The points were randomly chosen in areas where feces accumulated. A metal spatula was used to collect the feces. They were stored in glass petri dishes and then transferred to the laboratory at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Azcapotzalco campus. Each collected sample was weighed on a wet basis and taken to an oven at 60 °C for 24 hours at 60 °C, to eliminate water content.

The dry samples were taken to the laminar flow hood, where 50 ml of 50% hydrogen peroxide was added. The samples were left to rest for 1 to 3 weeks, during which 10 ml of hydrogen peroxide was added until the reaction stopped. After digestion, the samples were rinsed with deionized water (filtered with membranes) and filtered with filter paper. The process was carried out in the extraction hood. The filters were dried for 24 hours at 60 °C, and finally, each filter was analyzed.

2.4. Microplastics Classification and Statistical Analysis

Microplastics were analyzed under a digital microscope with 1,200x magnification to determine their abundance and classify them by shape (fragments, films, foams, and fibers) and color. Polymer composition was identified using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) with a wavelength range of 600–4000 cm⁻¹, employing 32 scans per sample for optimal spectral resolution.

A statistical analysis of the microplastic concentrations in the pigeon feces of the three sites (normalized by dry mass) was performed using Statgraphics Centurion XV, Version 15.2.06; all analyses were performed with 95% confidence. The data was thoroughly analyzed, starting with a normality test conducted using the Shapiro-Wilk method to assess whether the data followed a normal distribution. Since the data did not meet normality criteria, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to determine if statistically significant differences existed in the microplastic concentrations at the three sampling sites.

3. Results

This section shows the relevant results of this research.

3.3. Abundance, Characteristics and Statistial Analysys of Microplastics of the Sites Studied

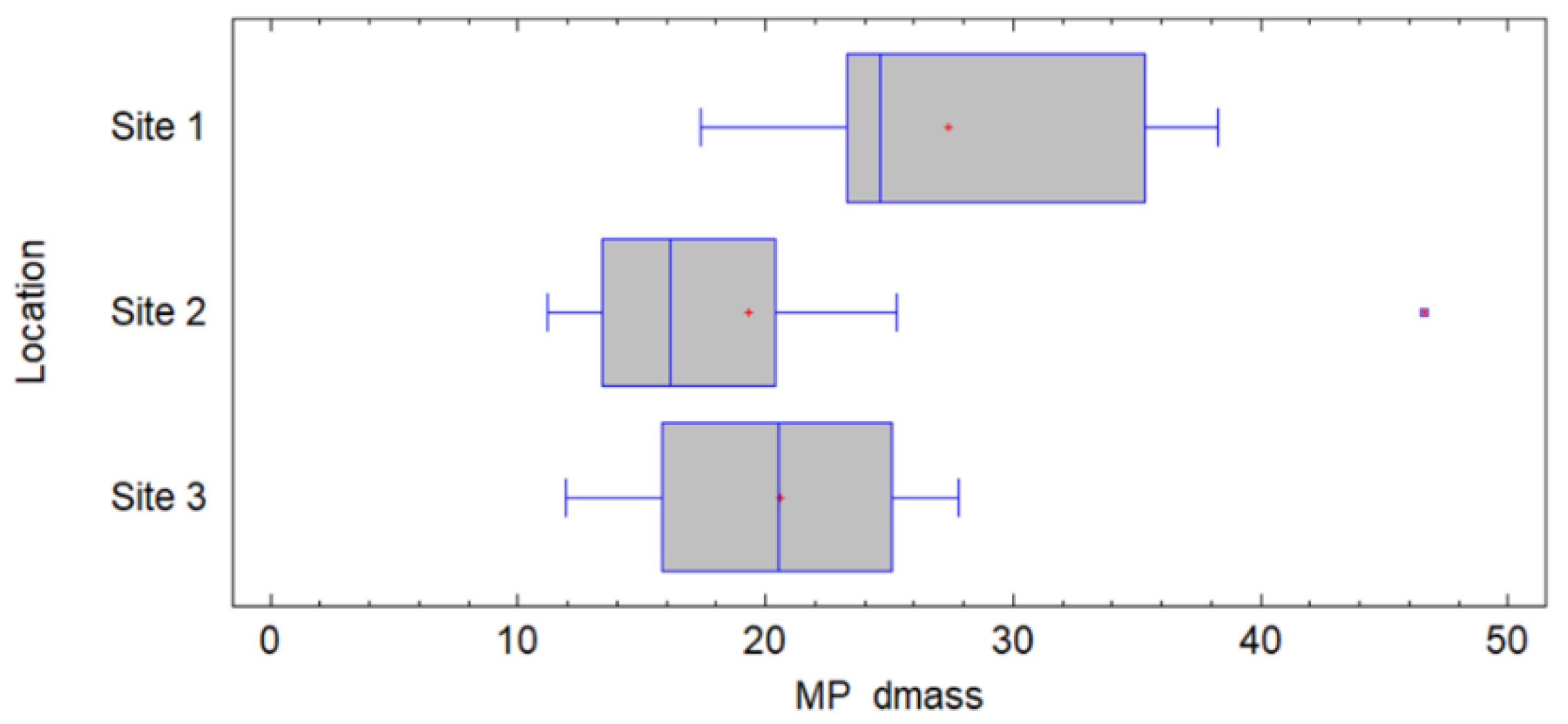

Microplastics were detected in all fecal samples analyzed, with concentrations ranging from 16.4 to 27.8 MP/g dry feces across the three sampling sites. Site 1, located near a public transport hub and bustling market, exhibited the highest mean concentration (27.4 ± 7.6 MP/g of dry mass), likely due to high levels of human activity and inadequate waste management. In contrast, Site 2, a residential area, recorded the lowest mean concentration (19.3 ± 10.5 MP/g of dry mass), reflecting reduced environmental disturbance. Site 3, a metro workshop surrounded by businesses, had intermediate concentrations (20.6 ± 5.3 MP/g of dry mass), indicating localized pollution sources potentially linked to industrial activity. (

Table 1).

Figure 2 presents the box-and-whisker plot illustrating the abundance of microplastics across the three sampling sites. The Kruskal-Wallis test yielded a p-value of 0.043, indicating a statistically significant difference in microplastic concentrations between sites. Sites 1 and 3 exhibited the highest values, likely due to greater exposure to plastic waste generated by the high density of pedestrians and street vendors in these areas. This increased human activity may contribute to higher contamination levels, thereby enhancing the pigeons’ likelihood of interacting with and ingesting microplastics.

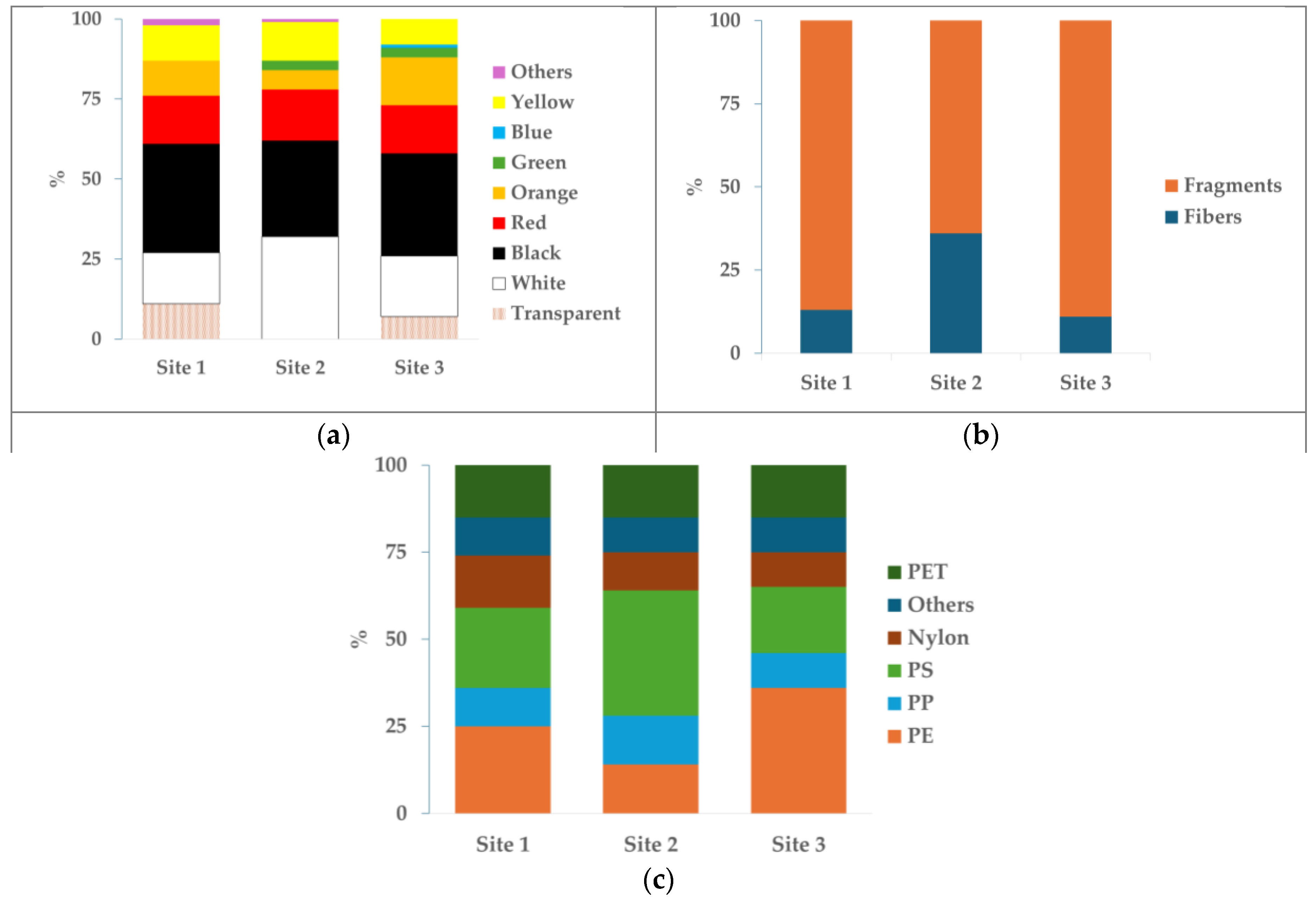

Figure 3 presents the classifications of microplastics based on their color, type, and polymer composition. The most prevalent shape identified was fragments, comprising 80% of all microplastics, followed by fibers at 20%. The color analysis revealed black as the most common (32%), followed by white (22%) and blue (16%). Polymers such as polystyrene (PS) and polyethylene (PE) dominated the samples, representing 26% and 25%, respectively. These findings highlight the diversity of environmental sources contributing to microplastic contamination and suggest that pigeons ingest particles derived from common urban waste materials, such as food packaging and textiles.

Figure 4 illustrates examples of MP extracted from pigeon feces, showcasing the diversity in shapes and colors observed across sites. Fragments were the most commonly identified shape, with fibers appearing less frequently. The variability in polymer types and particle colors reflects both environmental heterogeneity and potential selective ingestion patterns. These visual examples underscore the need for standardized imaging protocols to improve cross-study comparisons.

4. Discussion

The microplastic concentration in pigeon feces differed notably among the three sites, reflecting variations in environmental contamination and bird behavior. Site 1, located near a truck parking area and a bustling market, exhibited the highest average microplastic count (27.4 ± 7.6 particles/g of dry feces), potentially due to the extensive human activity and proximity to commercial activities. In contrast, Site 2, a residential area with less environmental disturbance, recorded the lowest average (19.3 ± 10.5 particles/g of dry feces), which might indicate reduced exposure to microplastic pollution. Interestingly, Site 3, a metro workshop surrounded by urban infrastructure, had intermediate microplastic levels (20.6 ± 5.3 particles/g of dry feces), suggesting localized contamination sources. These differences underscore how environmental settings and human activities influence microplastic availability and ingestion by urban birds.

Microplastic quantities vary significantly across studies, influenced by habitats, exposure pathways, and methodologies. Urban pigeons in our study showed moderate levels (19–27 particles/g of dry feces), while Tokunaga et al. (2023) reported fewer particles (13.6% detection) in bird lungs, emphasizing inhalation exposure. In other studies using feces as indicator of plastic ingestion, Gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papua) exhibited lower ingestion levels (0.23 ± 0.53 items/scat), reflecting the remoteness of their habitat but highlighting bioaccumulation through prey (Bessa et al., 2019). In contrast, King penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) showed higher microplastic densities (21.9 ± 5.8 microfibers/g), probably from foraging in polluted marine zones (Le Guen et al., 2020). In the other hand, terrestrial chickens had much higher counts (129.8 ± 82.3 particles/g), linked to extensive contamination and food-based exposure (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2017).

The microplastics identified in pigeon feces from this study displayed significant variability in shapes, colors, and polymer types, reflecting both the diversity of environmental sources and the birds' exposure to human activities. Fragments were the most commonly observed shape across all sites, aligning with trends reported in other studies on avian microplastic ingestion (Collard et al., 2022). This presence is likely due to the widespread degradation of larger plastic items into smaller pieces in urban environments. Fibers were also present, albeit in lower proportions, likely originating from synthetic textiles or ropes commonly found in urban waste streams. Notably, no pellets or foam particles were detected, suggesting limited exposure to primary microplastic sources, such as industrial raw materials or packaging foams, in these environments. Urban bird studies, including ours and Tokunaga et al. (2023) found fragments as the dominant shape, likely from degraded plastics. Marine birds, like penguins, ingested more fibers from textiles (Bessa et al., 2019; Le Guen et al., 2020).

Microplastic colors were predominantly transparent or white, followed by black and blue. Transparent and white particles are often associated with packaging materials and plastic bags, while black and blue particles could likely originate from tire wear, synthetic fabrics, or construction materials. The color distribution observed may indicate differences in the degradation and fragmentation of plastic materials in the environment or selective ingestion patterns by pigeons. Polymer types identified in the samples included polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), and polypropylene (PP), which are among the most common plastics produced globally. These polymers are ubiquitous in consumer goods, packaging, and urban litter, making them readily available in the environment. The predominance of these materials corroborates findings from other studies in urban settings and highlights the pervasive nature of these plastics. The composition of microplastics varied among the three sampling sites. For instance, fibers were slightly more frequent at Site 1, likely due to the high human activity near the market, where synthetic textiles are prevalent. Conversely, Site 3 exhibited a higher proportion of fragments, possibly linked to the mechanical wear and tear associated with metro workshops. These variations underscore how localized activities and waste management practices influence the types and characteristics of microplastics in urban areas.

Analyzing bird feces offers a non-invasive and practical way to assess microplastic ingestion, particularly in urban species like pigeons (Columba livia), which are accessible and defecate frequently. This method avoids ethical concerns associated with dissection and supports long-term monitoring of urban plastic pollution trends. Fecal analysis also helps trace pollution sources by identifying microplastic types, sizes, and shapes. However, the method has limitations. Digestive processes can alter results, as some microplastics are excreted more easily than others, complicating exposure assessments. Contamination during collection in polluted environments is another challenge, requiring stringent protocols to ensure data reliability. Additionally, fecal analysis confirms exposure but not ingestion rates or physiological impacts, necessitating complementary studies for validation. Standardized methodologies are essential to address variability and improve comparability across studies.

The observed differences in MP concentrations among sites highlight the role of localized human activities in shaping environmental contamination. Site 1, with its proximity to a bustling market and high pedestrian traffic, recorded the highest concentrations, likely due to inadequate waste management and direct littering. Conversely, Site 2, a residential area, exhibited lower contamination, possibly reflecting reduced anthropogenic pressures. These findings align with previous studies indicating that urbanization intensity is a significant driver of MP distribution (Carlen et al., 2021). However, methodological limitations, such as the potential loss of smaller MP during processing and the influence of pigeon-specific feeding behaviors, must be considered. Future studies should integrate complementary methods, such as gut dissection or isotopic tracing, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of MP exposure pathways in urban birds

5. Conclusions

Urban pigeons (Columba livia) could serve as effective bioindicators for environmental microplastic contamination due to their widespread presence and close interactions with anthropogenic environments. Unlike many avian species studied in marine or remote ecosystems, pigeons inhabit highly urbanized settings, making them valuable for assessing pollution in densely populated areas. Their dietary flexibility and frequent scavenging of human waste increase their exposure to microplastics, providing insights into pollution levels and the effectiveness of urban waste management systems. Leveraging pigeons as sentinels could enhance monitoring programs in urban environments and guide strategies to mitigate pollution.

This study demonstrates the utility of Columba livia as a bioindicator of urban MP pollution, offering a non-invasive approach to monitor environmental contamination in densely populated areas. The significant differences in MP concentrations among sites highlight the influence of localized human activities and waste management practices on urban ecosystems. However, the study's scope is limited to fecal analysis, which provides exposure data but not ingestion rates or physiological impacts. Future research should address these gaps by integrating physiological assessments, broader geographic sampling, and long-term monitoring to develop comprehensive mitigation strategies for urban plastic pollution.

The ingestion of microplastics by pigeons in this study raises concerns about urban ecosystem health and potential impacts on avian physiology. The differences among sites emphasize the need for localized interventions targeting specific pollution sources, such as better waste management near markets and transport hubs. Moreover, as pigeons are integral to urban ecosystems, their ingestion of microplastics could indicate broader environmental risks, including potential bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of plastics within urban food webs. These findings call for integrated urban policies addressing microplastic pollution to safeguard both wildlife and human communities sharing these spaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.A.Z., A.A.C.S. and A.V.M.; methodology, V.A.V.C., M.E.B.L. and A.A.C.S.; formal analysis, J.C.A.Z. and G.C.C.; investigation, G.C.C. and A.V.M.; resources, A.I.H.S. and A.V.M.; data curation, J.C.A.Z. and V.A.V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.A.Z., A.A.C.S. and A.V.M.; writing—review and editing, A.V.M. and A.A.C.S.; project administration, A.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bessa, F. et al. (2019) ‘Microplastics in gentoo penguins from the Antarctic region’, Scientific Reports, 9(1), pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Collard, F. et al. (2022) ‘Plastic ingestion and associated additives in Faroe Islands chicks of the Northern Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis’, Water Biology and Security, 1(4), pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Le Guen, C. et al. (2020) ‘Microplastic study reveals the presence of natural and synthetic fibres in the diet of King Penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) foraging from South Georgia’, Environment International, 134(November 2019), p. 105303. [CrossRef]

- Huerta Lwanga, E. et al. (2017) ‘Field evidence for transfer of plastic debris along a terrestrial food chain’, Scientific Reports, 7(1), pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y. et al. (2023) ‘Airborne microplastics detected in the lungs of wild birds in Japan’, Chemosphere, 321(November 2022), p. 138032. [CrossRef]

- Reports, 9(1), pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Collard, F. et al. (2022) ‘Plastic ingestion and associated additives in Faroe Islands chicks of the Northern Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis’, Water Biology and Security, 1(4), pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Le Guen, C. et al. (2020) ‘Microplastic study reveals the presence of natural and synthetic fibres in the diet of King Penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) foraging from South Georgia’, Environment International, 134(November 2019), p. 105303. [CrossRef]

- Huerta Lwanga, E. et al. (2017) ‘Field evidence for transfer of plastic debris along a terrestrial food chain’, Scientific Reports, 7(1), pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y. et al. (2023) ‘Airborne microplastics detected in the lungs of wild birds in Japan’, Chemosphere, 321(November 2022), p. 138032. [CrossRef]

- Bao, R., Cheng, Z., Hou, Y., Xie, C., Pu, J., Peng, L., Gao, L., Chen, W., & Su, Y. (2022). Secondary microplastics formation and colonized microorganisms on the surface of conventional and degradable plastic granules during long-term UV aging in various environmental media. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 439(July), 129686. [CrossRef]

- Batool, F., Khan, H. A., & Saif-Ur-rehman, M. (2020). Feeding ecology of blue rock pigeon (Columba livia) in the three districts of Punjab, Pakistan. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 80(4), 881–890. [CrossRef]

- Bessa, F., Ratcliffe, N., Otero, V., Sobral, P., Marques, J. C., Waluda, C. M., Trathan, P. N., & Xavier, J. C. (2019). Microplastics in gentoo penguins from the Antarctic region. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Gu, X., Sun, Z., Xu, Y., Li, J., Pu, L., Ren, J., & Wang, X. (2023). Aging Characteristics and Ecological Effects of Primary Microplastics in Cosmetic Products Under Different Aging Processes. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 110(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Carlen, E. J., Li, R., & Winchell, K. M. (2021). Urbanization predicts flight initiation distance in feral pigeons (Columba livia) across New York City. Animal Behaviour, 178, 229–245. [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, A., Mielańczuk, M., & Syczewski, M. (2022). The Raman spectroscopy and SEM/EDS investigation of the primary sources of microplastics from cosmetics available in Poland. Chemosphere, 308(September). [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E. C., de Vine, R., Pantos, O., Clunies-Ross, P., Doake, F., Masterton, H., & Briers, R. A. (2022). Quantification and Characterisation of Pre-Production Pellet Pollution in the Avon-Heathcote Estuary/Ihutai, Aotearoa-New Zealand. Microplastics, 1(1), 67–84. [CrossRef]

- Lackmann, C., Velki, M., Šimić, A., Müller, A., Braun, U., Ečimović, S., & Hollert, H. (2022). Two types of microplastics (polystyrene-HBCD and car tire abrasion) affect oxidative stress-related biomarkers in earthworm Eisenia andrei in a time-dependent manner. Environment International, 163(February). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Liu, X., Bai, Y., Wei, H., & Lu, J. (2023). Spatiotemporal distribution and potential sources of atmospheric microplastic deposition in a semiarid urban environment of Northwest China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(29), 74372–74385. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-mancera, V. M., Salle, U. D. La, Buitrago-medina, D. A., Rosario, U., Marcela, V., & Alejandro, M. D. (2023). Revista de Medicina Veterinaria The domestic pigeon (Columba livia) and its association with self- perceived respiratory and skin morbidity in a neighborhood of Bogotá The domestic pigeon (Columba livia) and its association with self-perceived respira. 1(46).

- Sherlock, C., Fernie, K. J., Munno, K., Provencher, J., & Rochman, C. (2022). The potential of aerial insectivores for monitoring microplastics in terrestrial environments. Science of the Total Environment, 807, 150453. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y., Okochi, H., Tani, Y., Niida, Y., Tachibana, T., Saigawa, K., Katayama, K., Moriguchi, S., Kato, T., & Hayama, S. ichi. (2023). Airborne microplastics detected in the lungs of wild birds in Japan. Chemosphere, 321(February), 138032. [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, S. L., Feura, J. M., Rush, S. A., Iglay, R. B., & Woodrey, M. S. (2021). Availability and assessment of microplastic ingestion by marsh birds in Mississippi Gulf Coast tidal marshes. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 166(October 2020), 112187. [CrossRef]

- Xia, B., Sui, Q., Du, Y., Wang, L., Jing, J., Zhu, L., Zhao, X., Sun, X., Booth, A. M., Chen, B., Qu, K., & Xing, B. (2022). Secondary PVC microplastics are more toxic than primary PVC microplastics to Oryzias melastigma embryos. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 424(PB), 127421. [CrossRef]

- Carlin, J., Craig, C., Little, S., Donelly, M., Fox, D., Zhei, L., & Walters, L. (2020). Microplastic accumulation in the gastrointestinal tracts in birds of prey in central Florida, USA. 264. [CrossRef]

- Rivers-Auty, J., Bond, A. L., Grant, M. L., & Lavers, J. L. (2023). The one-two punch of plastic exposure: Macro- and micro-plastics induce multi-organ damage in seabirds. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 442, 130117. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Salas, A. A. ., Álvarez-Zeferino, J. C., Tapia-Fuentes, J., Pérez-Aragón, B., Martínez-Salvador, C., Vázquez-Morillas, A., & Ojeda-Benítez, S. (2023). Measures to prevent cross-contamination in the analysis of microplastics: A short literature review. Revista Internacional De Contaminación Ambiental, 39, 241–256. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).