Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of MXenes

2.3. Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles and MXene/MNPs Heterostructures

2.4. PEG-Coating of MXenes and Nanoparticles

2.5. Synthesis of Polymer-Based Nanocomposites

2.6. Structural and Chemical Characterization

2.7. Magnetic Characterization

2.8. Photocatalysis and Piezocatalysis Study

3. Results and Discussion

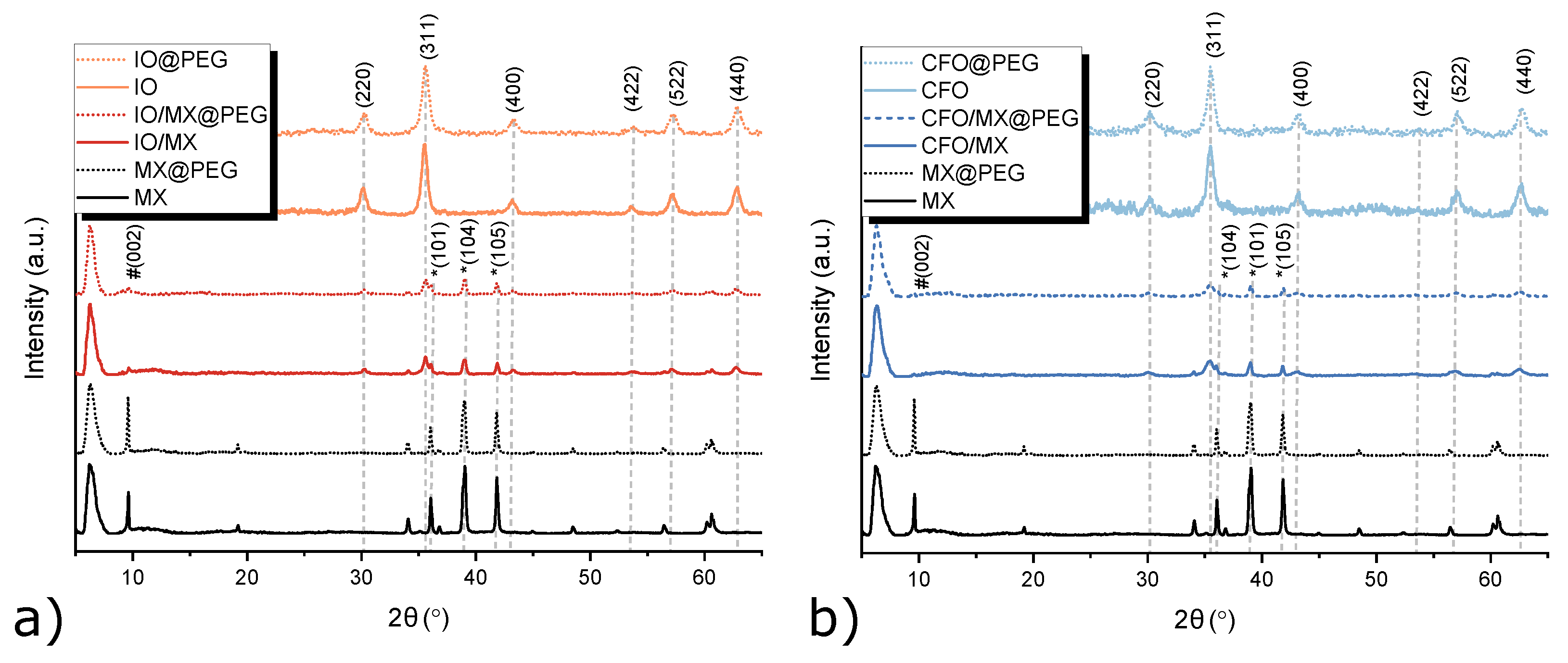

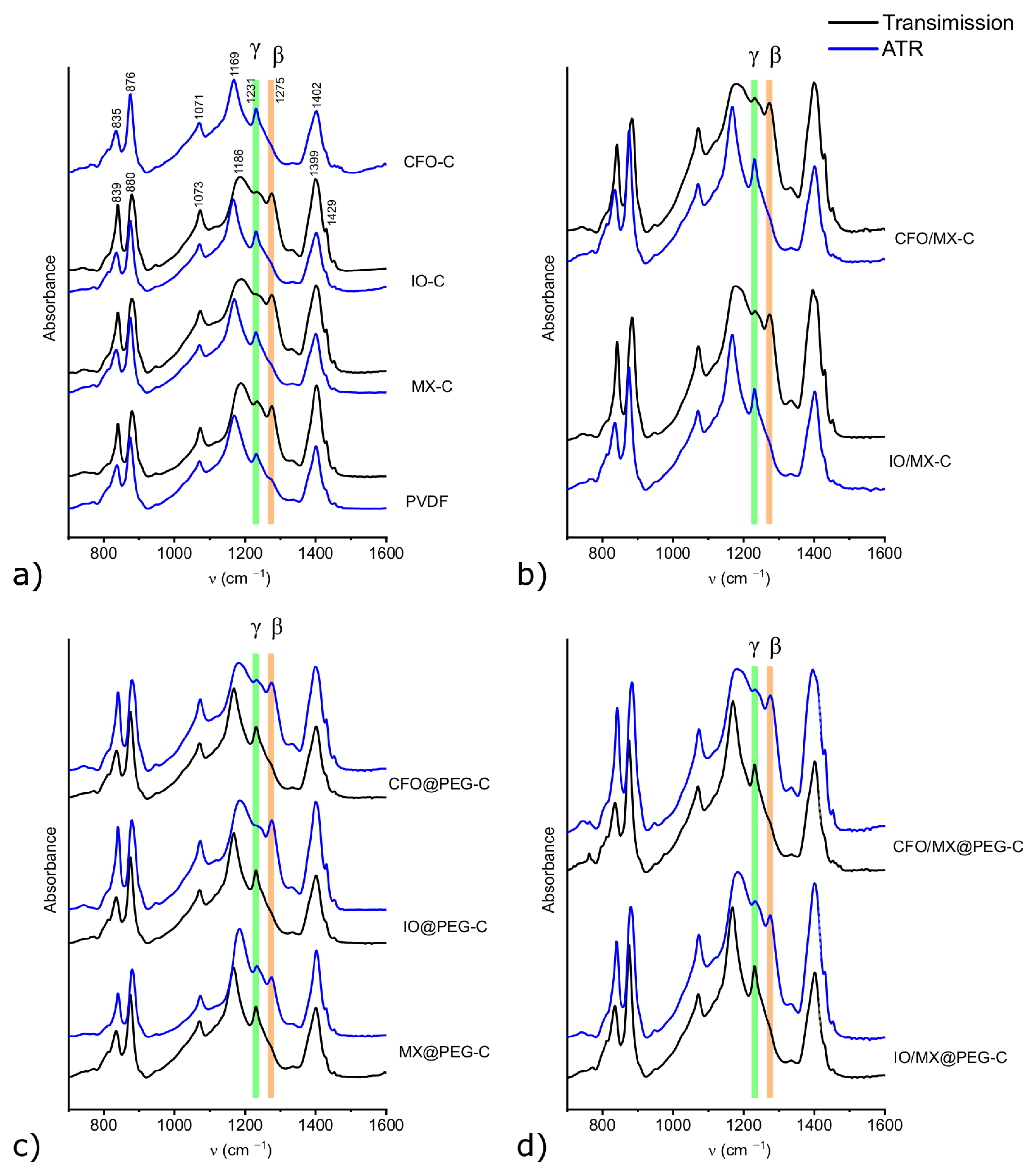

3.1. Structural Characterization of Single Materials and Heterostructures

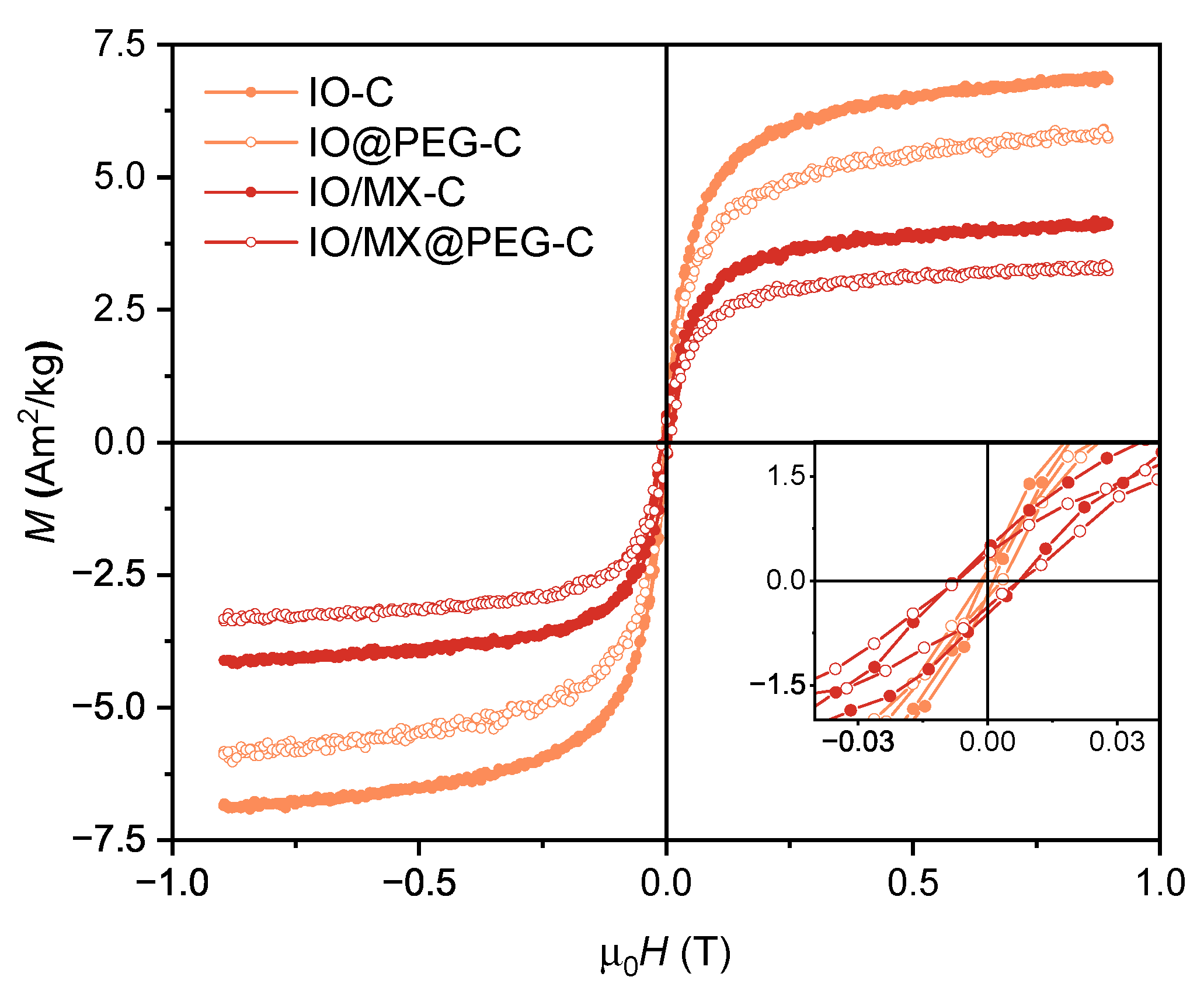

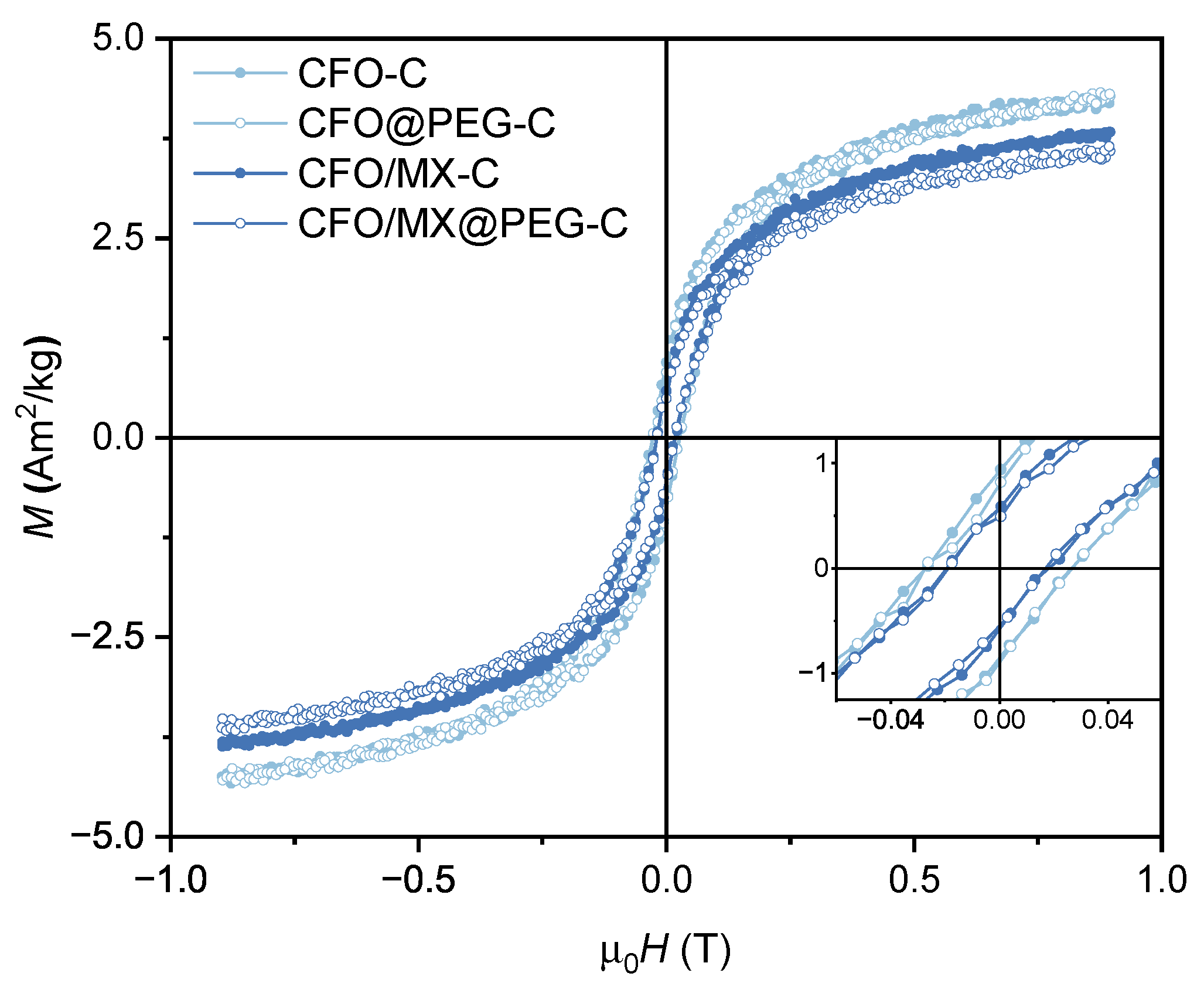

3.2. Magnetic Properties of PVDF-Based Nanocomposites

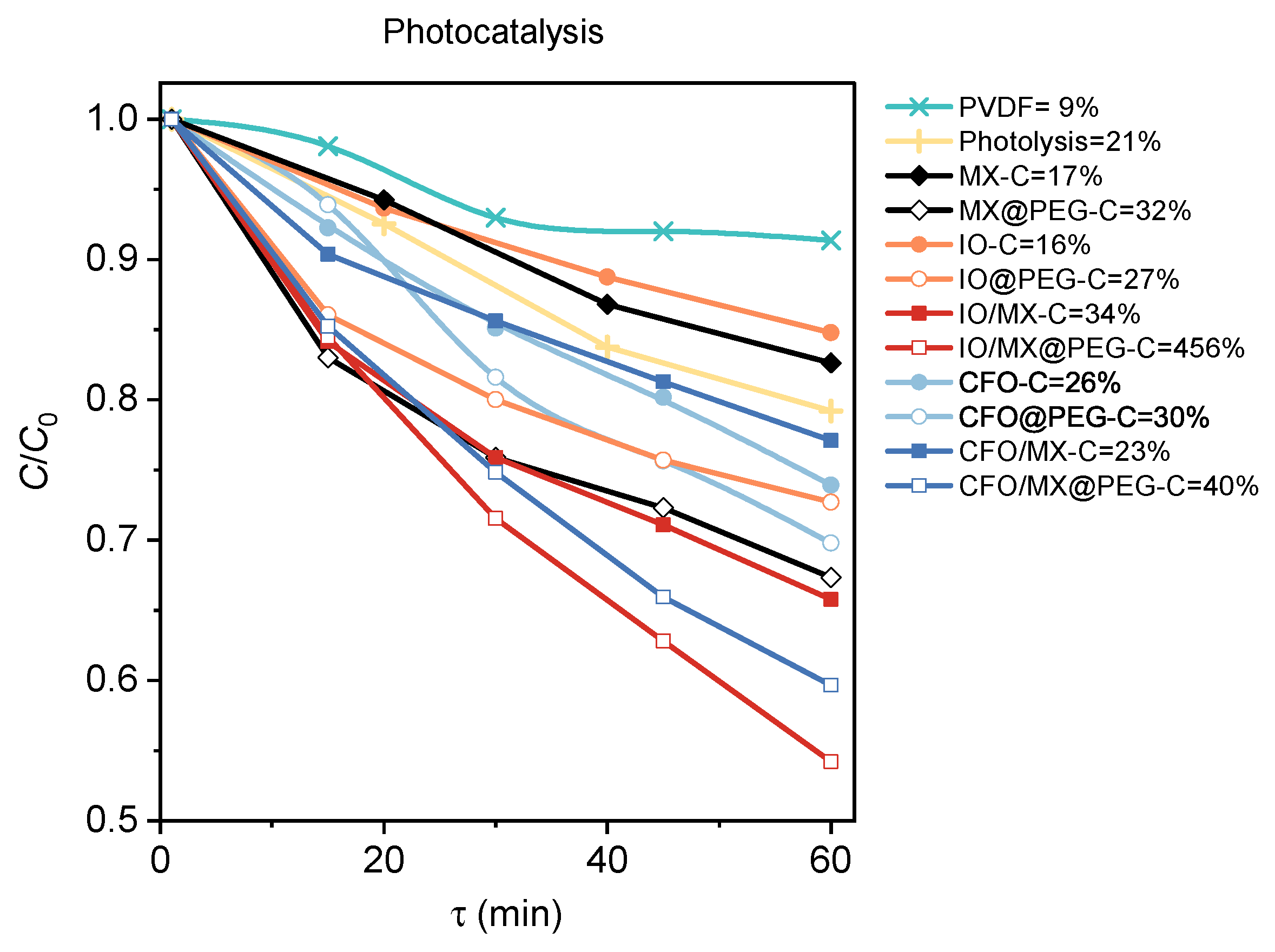

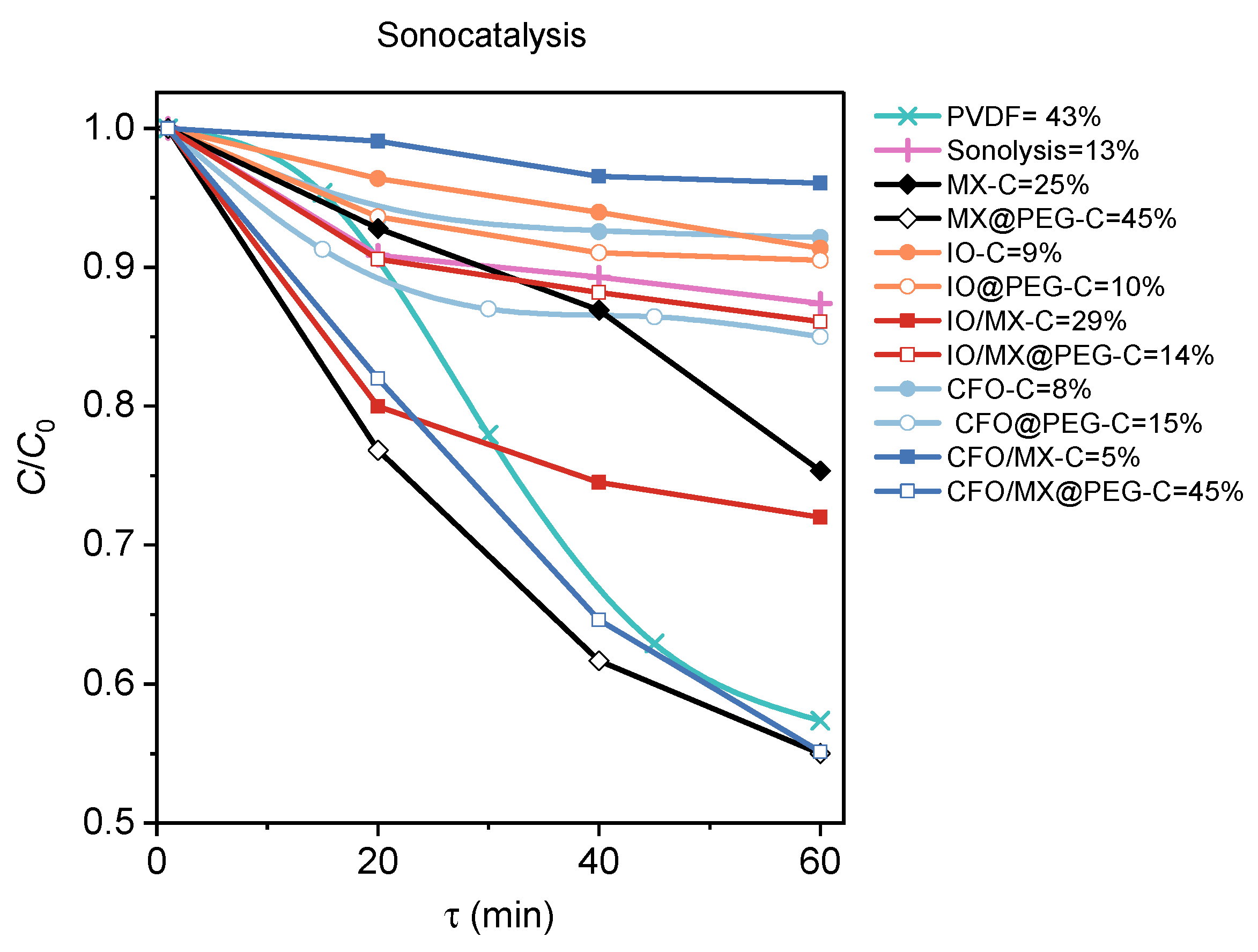

3.3. Photocatalysis and Piezocatalysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mondal, S.; Purkait, M.K.; De, S. Advances in Dye Removal Technologies, 1 ed.; Green Chemistry and Sustainable Technology (GCST), Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; p. 323. 341 b/w illustrations, 21 illustrations in colour. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Suárez, L.A.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.G.; Linares-Hernández, I.; Martínez-Miranda, V.; Teutli-Sequeira, E.A. A critical review of textile industry wastewater: green technologies for the removal of indigo dyes. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 20, 10553–10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, T.; Repon, M.R.; Islam, T.; Sarwar, Z.; Rahman, M.M. Impact of textile dyes on health and ecosystem: a review of structure, causes, and potential solutions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 9207–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, N.; Tahmid, M.; Shoronika, A.Z.; Fariha, A.; Roy, H.; Pervez, M.N.; Cai, Y.; Naddeo, V.; Islam, M.S. A Comprehensive Review on the Sustainable Treatment of Textile Wastewater: Zero Liquid Discharge and Resource Recovery Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Textile dye wastewater characteristics and constituents of synthetic effluents: a critical review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2019, 16, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanaw, A.; Birlie, B.; Teshome, B.; Jemberie, M. Textile effluent treatment methods and eco-friendly resolution of textile wastewater. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2022, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, G.; Arputhalatha, A.; Kannan, K.; Lakkaboyana, S.K.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Kumar, V.; Marella, R.K. Current Trends in the Application of Nanomaterials for the Removal of Pollutants from Industrial Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadow, S.I.; Estrada, A.L.; Li, Y.Y. Characterization and potential of two different anaerobic mixed microflora for bioenergy recovery and decolorization of textile wastewater: Effect of C/N ratio, dye concentration and pH. Bioresource Technology Reports 2022, 17, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, C.M.B.; Oliveira do Nascimento, G.F.; Bezerra da Costa, G.R.; Baptisttella, A.M.S.; Fraga, T.J.M.; de Assis Filho, R.B.; Ghislandi, M.G.; da Motta Sobrinho, M.A. Real textile wastewater treatment using nano graphene-based materials: Optimum pH, dosage, and kinetics for colour and turbidity removal. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2020, 98, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuengmatcha, P.; Kuyyogsuy, A.; Porrawatkul, P.; Pimsen, R.; Chanthai, S.; Nuengmatcha, P. Efficient degradation of dye pollutants in wastewater via photocatalysis using a magnetic zinc oxide/graphene/iron oxide-based catalyst. Water Science and Engineering 2023, 16, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Pal, A.; Sahoo, C. Photocatalytic degradation of a mixture of Crystal Violet (Basic Violet 3) and Methyl Red dye in aqueous suspensions using Ag+ doped TiO2. Dyes and Pigments 2006, 69, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, C.; Skillen, N.; Adams, M.; Robertson, P.K. Photocatalytic reactors for environmental remediation: a review. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2011, 86, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, N.; Palanichamy, M.; Murugesan, V. Sol–gel preparation and characterization of alkaline earth metal doped nano TiO2: Efficient photocatalytic degradation of 4-chlorophenol. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 2007, 273, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.S.; Xu, H.; Konishi, H.; Li, X. Direct Water Splitting Through Vibrating Piezoelectric Microfibers in Water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2010, 1, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.S.; Xu, H.; Konishi, H.; Li, X. Piezoelectrochemical Effect: A New Mechanism for Azo Dye Decolorization in Aqueous Solution through Vibrating Piezoelectric Microfibers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2012, 116, 13045–13051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Li, W.; Zheng, R.K.; Luo, H. Piezoelectrically induced mechano-catalytic effect for degradation of dye wastewater through vibrating Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 fibers. Applied Physics Letters 2014, 104, 162907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, M.; Adamaki, V.; Khanbareh, H.; Bowen, C.R. Control of electro-chemical processes using energy harvesting materials and devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 7757–7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sang, Y.; Chang, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, R.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.L. Enhanced Ferroelectric-Nanocrystal-Based Hybrid Photocatalysis by Ultrasonic-Wave-Generated Piezophototronic Effect. Nano Letters 2015, 15, 2372–2379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.F.; Ong, W.L.; Ho, G.W. Self-Biased Hybrid Piezoelectric-Photoelectrochemical Cell with Photocatalytic Functionalities. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 7661–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Yan, C.F.; Rtimi, S.; Bandara, J. Piezoelectric materials for catalytic/photocatalytic removal of pollutants: Recent advances and outlook. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2019, 241, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.M.; Chang, K.S. Synergistic piezophotocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performance of poly(vinylidene fluoride)–ZnSnO3 and poly(methyl methacrylate)–ZnSnO3 nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 30513–30520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Fu, Y.; Zang, W.; Wang, Q.; Xing, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, X. A flexible self-powered T-ZnO/PVDF/fabric electronic-skin with multi-functions of tactile-perception, atmosphere-detection and self-clean. Nano Energy 2017, 31, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.A.; Ahmad Sajid, T.; Saeed, M.; Naseem, B.; Muneer, M. Explication of molecular interactions between leucine and pharmaceutical active ionic liquid in an aqueous system: Volumetric and acoustic studies. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 360, 119510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghows, N.; Entezari, M.H. Exceptional catalytic efficiency in mineralization of the reactive textile azo dye (RB5) by a combination of ultrasound and core–shell nanoparticles (CdS/TiO2). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2011, 195, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataee, A.; Karimi, A.; Arefi-Oskoui, S.; Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani, R.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Soltani, B.; Joo, S.W. Sonochemical synthesis of Pr-doped ZnO nanoparticles for sonocatalytic degradation of Acid Red 17. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2015, 22, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirsath, S.; Pinjari, D.; Gogate, P.; Sonawane, S.; Pandit, A. Ultrasound assisted synthesis of doped TiO2 nano-particles: Characterization and comparison of effectiveness for photocatalytic oxidation of dyestuff effluent. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2013, 20, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, A.; Ning, X.; Cao, Y.; Xie, J.; Jia, D. Boosting the piezocatalytic performance of Bi2WO6 nanosheets towards the degradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Xie, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G. High piezo–catalytic activity of ZnO/Al2O3 nanosheets utilizing ultrasonic energy for wastewater treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 242, 118532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, S. Atomically thin ZnS nanosheets: Facile synthesis and superior piezocatalytic H2 production from pure H2O. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2020, 277, 119250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Qiu, J.; Li, N.; Chen, D.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; He, J.; Lu, J. Efficient piezocatalytic removal of BPA and Cr(VI) with SnS2/CNFs membrane by harvesting vibration energy. Nano Energy 2021, 86, 106036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, B.; Hoque, N.A.; Janowicz, N.; Das, S.; Tiwari, M.K. Re-usable self-poled piezoelectric/piezocatalytic films with exceptional energy harvesting and water remediation capability. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Yao, B.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Yu, Y.; Niu, J. Fabrication of PVDF-based piezocatalytic active membrane with enhanced oxytetracycline degradation efficiency through embedding few-layer E-MoS2 nanosheets. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 415, 129000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadanova, A.; Abdurakhmanov, M.; Gulakhmedov, R.; Shuaibov, A.; Selimov, D.; Sobola, D.; Částková, K.; Ramazanov, S.; Orudzhev, F. Piezo-, photo- and piezophotocatalytic activity of electrospun fibrous PVDF/CTAB membrane. Chimica Techno Acta 2022, 9, 20229420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Huang, Q. MXenes: Two-Dimensional Building Blocks for Future Materials and Devices. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 5775–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, S.; Kiran, N.U.; Mane, P.; Chakraborty, B.; Besra, L.; Chatterjee, S.; Chatterjee, S. Hydrophobic MXene with enhanced electrical conductivity. Surfaces and Interfaces 2023, 39, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, K.; Omelyanchik, A.; Shilov, N.; Gorshenkov, M.; Andreev, N.; Comite, A.; Slimani, S.; Peddis, D.; Ovchenkov, Y.; Vasiliev, A.; Magomedov, K.E.; Rodionova, V. Iron Oxide Nanoparticle-Assisted Delamination of Ti3C2Tx MXenes: A New Approach to Produce Magnetic MXene-Based Composites. Nanomaterials 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, B.; Gogotsi, Y. MXenes: trends, growth, and future directions. Graphene and 2D Materials 2022, 7, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, K.V.; Magomedov, K.E.; Shilov, N.R.; Rodionova, V.V.; Omelyanchik, A.S. Adsorption of Copper Ions on the Surface of Multilayer Ti3C2Tx MXenes with Mixed Functionalization. Nanobiotechnology Reports 2023, 18, S84–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, Z. Adsorptive environmental applications of MXene nanomaterials: a review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 19895–19905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, I.; Bukhari, A.; Gilani, E.; Nazir, A.; Zain, H.; Bukhari, A.; Shaheen, A.; Hussain, S.; Imtiaz, A. Functionalization of chitosan biopolymer using two dimensional metal-organic frameworks and MXene for rapid, efficient, and selective removal of lead (II) and methyl blue from wastewater. Process Biochemistry 2023, 129, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, S.; Akram, S.; Murtaza, M.; Amjad, A.; Shah, S.S.A.; Waseem, A. Development of MOF-MXene composite for the removal of dyes and antibiotic. Diamond and Related Materials 2023, 136, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi Hafez Moghaddas, S.M.; Elahi, B.; Javanbakht, V. Biosynthesis of pure zinc oxide nanoparticles using Quince seed mucilage for photocatalytic dye degradation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 821, 153519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaez, Z.; Javanbakht, V. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of ZSM-5/ZnO nanocomposite modified by Ag nanoparticles for methyl orange degradation. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2020, 388, 112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Javanbakht, V. Dye removal from aqueous solution by a novel dual cross-linked biocomposite obtained from mucilage of Plantago Psyllium and eggshell membrane. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 134, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, M.; Javanbakht, V. Photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes by a novel nanophotocatalyst of TiO2/ZnTiO3/αFe2O3 by ultraviolet light irradiation. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2018, 29, 9908–9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, M.; Javanbakht, V. Methylene Blue removal from aqueous solution by a biocomposite synthesized from sodium alginate and wastes of oil extraction from almond peanut. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 114, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, M.; Javanbakht, V.; Esmaili, J. Synthesis of zeolite/nickel ferrite/sodium alginate bionanocomposite via a co-precipitation technique for efficient removal of water-soluble methylene blue dye. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 116, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeenjan, F.; Javanbakht, V. Methylene blue removal from aqueous solution by magnetic clinoptilolite/chitosan/EDTA nanocomposite. Research on Chemical Intermediates 2018, 44, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Waldner, G.; Fallmann, H.; Hager, S.; Klare, M.; Krutzler, T.; Malato, S.; Maletzky, P. The photo-fenton reaction and the TiO2/UV process for waste water treatment—novel developments. Catalysis Today 1999, 53, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William H. Glaze, J.W.K.; Chapin, D.H. The Chemistry of Water Treatment Processes Involving Ozone, Hydrogen Peroxide and Ultraviolet Radiation. Ozone: Science & Engineering 1987, 9, 335–352. [CrossRef]

- Ítalo Lacerda Fernandes.; Pereira Barbosa, D.; Botelho de Oliveira, S.; Antônio da Silva, V.; Henrique Sousa, M.; Montero-Muñoz, M.; A. H. Coaquira, J. Synthesis and characterization of the MNP@SiO2@TiO2 nanocomposite showing strong photocatalytic activity against methylene blue dye. Applied Surface Science 2022, 580, 152195. [CrossRef]

- Mahdikhah, V.; Saadatkia, S.; Sheibani, S.; Ataie, A. Outstanding photocatalytic activity of CoFe2O4 /rGO nanocomposite in degradation of organic dyes. Optical Materials 2020, 108, 110193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, Z.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.; Lung, C.W.; Lo, I.M.C. Magnetically recyclable nanophotocatalysts in photocatalysis-involving processes for organic pollutant removal from wastewater: current status and perspectives. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2024, 11, 1784–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, A.; Mennig, M.;Schmidt, H.,DoctorBlade.In Sol-Gel Technologies for Glass Producers and Users; Aegerter, M.A.; Mennig, M., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2004; pp. 89–92. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Guidolin, T.; Possolli, N.M.; Polla, M.B.; Wermuth, T.B.; Franco de Oliveira, T.; Eller, S.; Klegues Montedo, O.R.; Arcaro, S.; Cechinel, M.A.P. Photocatalytic pathway on the degradation of methylene blue from aqueous solutions using magnetite nanoparticles. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 318, 128556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, C.A.; Song, Y.; Huang, Y. A novel simple method to stably synthesize Ti3AlC2 powder with high purity. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2006, 428, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, Y. Pressureless Sintering and Properties of Ti3AlC2. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology 2010, 7, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidiu, M.; Lukatskaya, M.R.; Zhao, M.Q.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide `clay’with high volumetric capacitance. Nature 2014, 516, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelyanchik, A.S.; Sobolev, K.V.; Shilov, N.R.; Andreev, N.V.; Gorshenkov, M.V.; Rodionova, V.V. Modification of the Codeposition Method for the Synthesis of Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles with a High Magnetization Value and a Controlled Reaction Yield. Nanobiotechnology Reports 2023, 18, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio, T.; Bottino, A.; Capannelli, G.; Piaggio, P. Characterization of PVDF membranes by vibrational spectroscopy. Journal of Membrane Science 2002, 210, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, D.; D’Souza, N.A. One-step fabrication of biomimetic PVDF-BaTiO3 nanofibrous composite using DoE. Materials Research Express 2018, 5, 085308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, A.M.; Afifi, M. Influence the β-PVDF phase on structural and elastic properties of PVDF/PLZT composites. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2024, 301, 117152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliya, R.Z.; Ooi, P.C.; Sadri, R.; Talik, N.A.; Yau, Z.Y.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Goh, B.T.; Dee, C.F.; Aslfattahi, N.; Al-Bati, S.; Ibtehaj, K.; Hj Jumali, M.H.; Mohd Razip Wee, M.F.; Mohamed, M.A.; Othman, M. Exploration of 2D Ti3C2 MXene for all solution processed piezoelectric nanogenerator applications. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marija, M.; M., N.L. Modification of TiO2 nanoparticles through lanthanum doping and peg templating. Processing and Application of Ceramics 2014, 8, 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Jo, E.H.; Jang, H.D.; Kim, T.O. Synthesis of PEG-modified TiO2–InVO4 nanoparticles via combustion method and photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Materials Letters 2013, 92, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y.; Huang, H.; He, H.; Ji, H.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J. Highly sensitive, reliable and flexible pressure sensor based on piezoelectric PVDF hybrid film using MXene nanosheet reinforcement. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 886, 161069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orudzhev, F.; Alikhanov, N.; Amirov, A.; Rabadanova, A.; Selimov, D.; Shuaibov, A.; Gulakhmedov, R.; Abdurakhmanov, M.; Magomedova, A.; Ramazanov, S.; Sobola, D.; Giraev, K.; Amirov, A.; Rabadanov, K.; Gadzhimagomedov, S.; Murtazali, R.; Rodionova, V. Porous Hybrid PVDF/BiFeO3 Smart Composite with Magnetic, Piezophotocatalytic, and Light-Emission Properties. Catalysts 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cai, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Li, K.; Lee, J.M.; Min, Y. photocatalytic degradation of TiO2 via incorporating Ti3C2 MXene for methylene blue removal from water. Catalysis Communications 2023, 174, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, M.S.I.; Samsudin, M.F.R.; Tahir, A.A.; Sufian, S. Effect of MXene Loaded on g-C3N4 Photocatalyst for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My Tran, N.; Thanh Hoai Ta, Q.; Sreedhar, A.; Noh, J.S. Ti3C2Tx MXene playing as a strong methylene blue adsorbent in wastewater. Applied Surface Science 2021, 537, 148006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, L.; Geng, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Lv, P.; Mu, Y.; Huang, S. Heterostructured MXene-derived oxides as superior photocatalysts for MB degradation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 919, 165629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample (group/ID) | Filler (10 wt.%) | PEG Coated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Polymer | PVDF | - | - |

| MXene-based | MX-C | TiCT | - |

| MX@PEG-C | TiCT | ✓ | |

| Iron Oxide-based | IO-C | FeO | - |

| IO@PEG-C | FeO | ✓ | |

| IO/MX-C | TiCT/FeO | - | |

| IO/MX@PEG-C | TiCT/FeO | ✓ | |

| Cobalt Ferrite-based | CFO-C | CoFeO | - |

| CFO@PEG-C | CoFeO | ✓ | |

| CFO/MX-C | TiCT/CoFeO | - | |

| CFO/MX@PEG-C | TiCT/CoFeO | ✓ |

| Sample | D, nm | a, Å |

| FeO | 10±1 | 8.352±0.007 |

| TiCT/FeO | 15±3 | 8.357±0.007 |

| CoFeO | 10±2 | 8.380±0.006 |

| TiCT/CoFeO | 9±1 | 8.387±0.008 |

| Sample | M[A mkg] | M/M | H[mT] |

| IO-C | 7.4±0.7 | 0.02 | 2.4±0.1 |

| IO@PEG-C | 6.4±0.6 | 0.03 | 4.9±0.1 |

| IO/MX-C | 4.4±0.4 | 0.10 | 14.9±0.1 |

| IO/MX@PEG-C | 3.6±0.4 | 0.11 | 14.6±0.1 |

| CFO-C | 5.2±0.5 | 0.18 | 53.7±0.1 |

| CFO@PEG-C | 4.8±0.5 | 0.16 | 54.4±0.1 |

| CFO/MX-C | 4.3±0.4 | 0.13 | 37.7±0.1 |

| CFO/MX@PEG-C | 4.1±0.4 | 0.12 | 35.9±0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).