Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. TA Outcomes Among Trauma-Exposed Youth

1.2. Services and Programs Aiming to Support the TA

1.3. Trauma-Informed Care

- What are the existing needs and TIC approaches to specifically support the TA of trauma-exposed youth?

- What are the effects of implementing TIC approaches?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Concept

2.1.3. Context

2.2. Types of Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

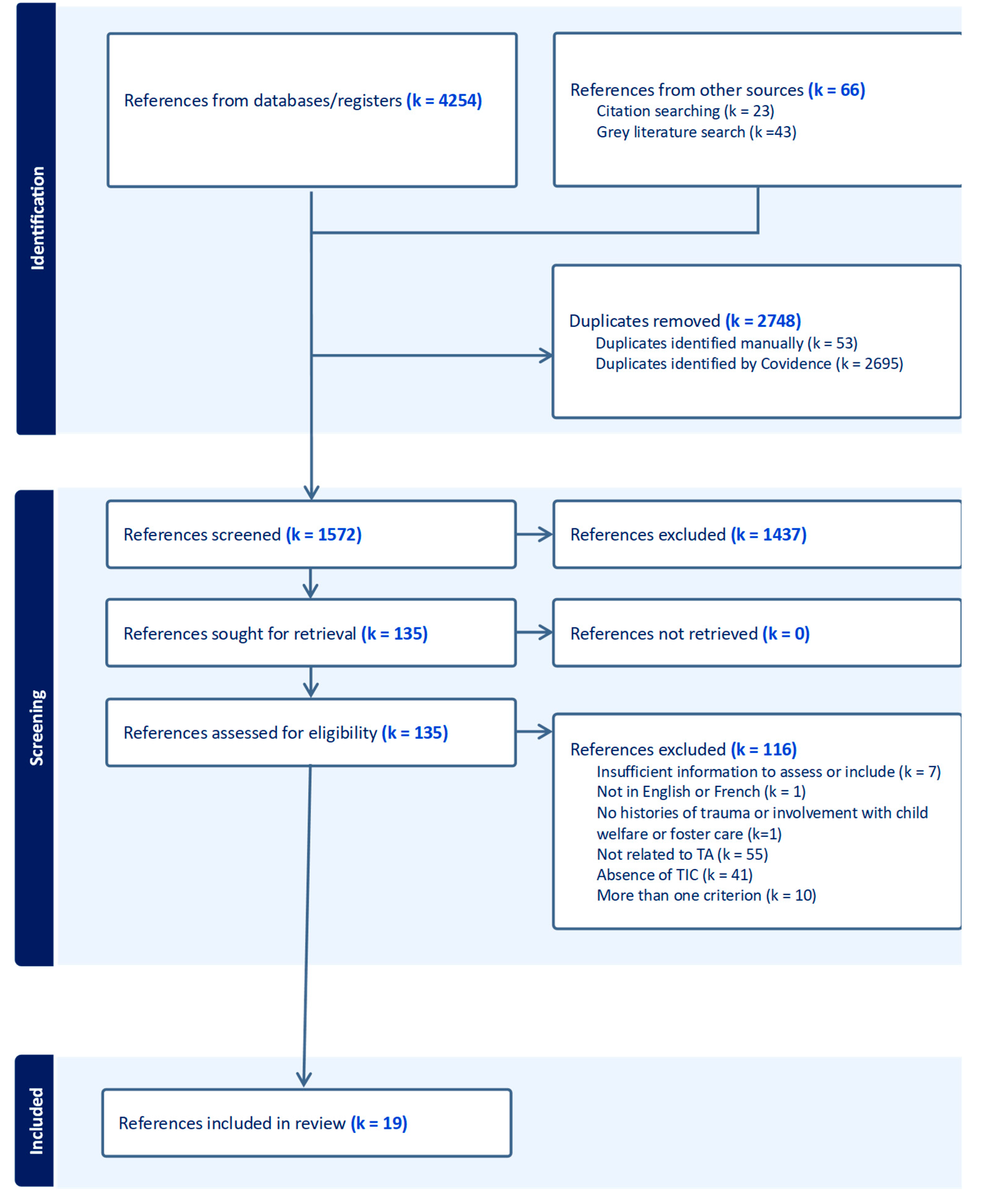

2.4. Sources of Evidence Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Analysis and Presentation

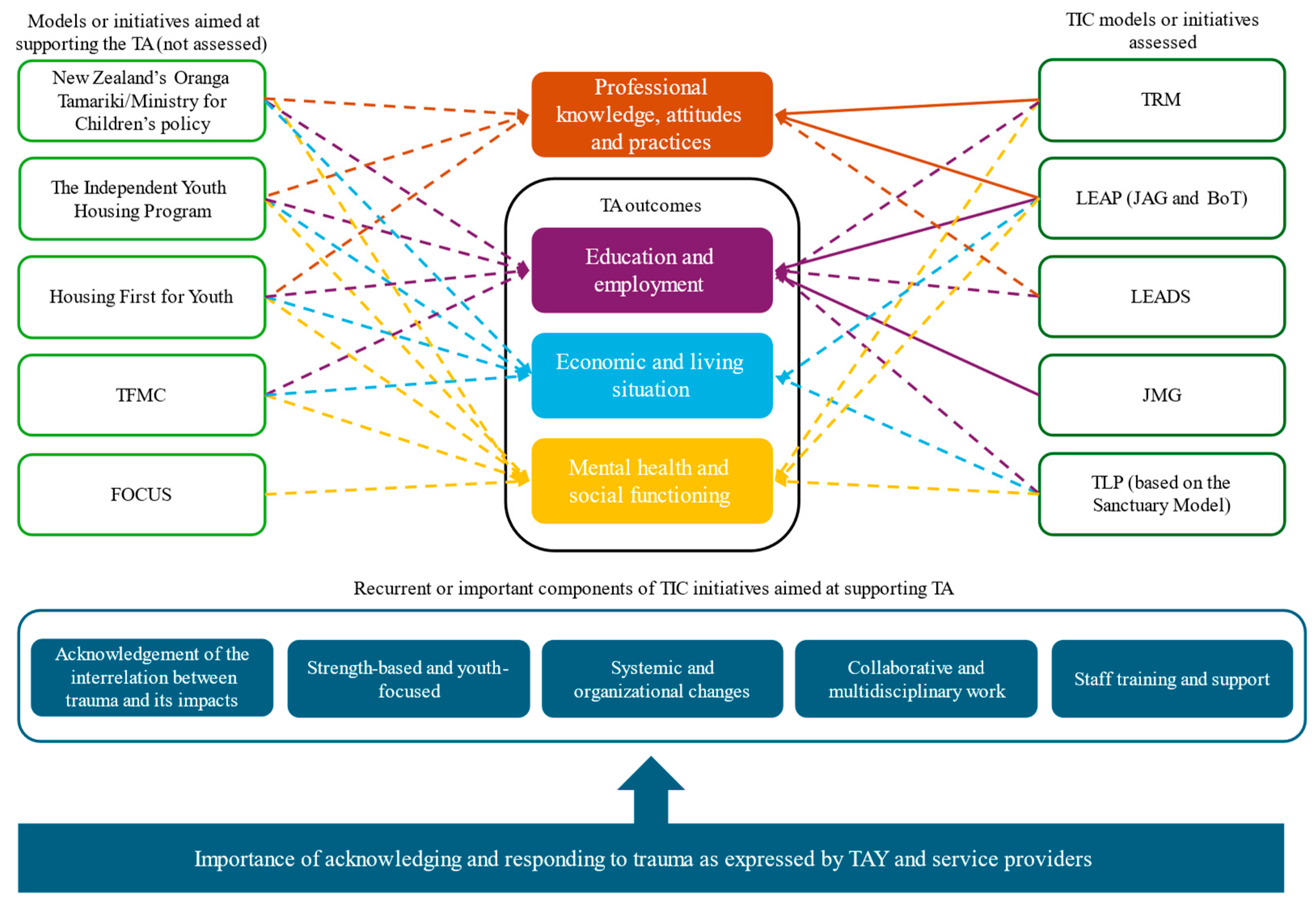

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included References

3.1.1. Need for or Importance of TIC

3.1.2. Description of Practices and Policies

3.1.3. Evaluation of TIC

3.1.4. Importance, Description and Evaluation of TIC

3.2. Results of Included References

3.2.1. Evidence of the Importance of or Need for TIC to Support the TA

3.2.2. Description of Existing TIC Practices and Policies Supporting the TA

3.2.3. Results of Evaluations of TIC Practices and Policies

4. Discussion

4.1. Acknowledging and Responding to Trauma

4.2. The Definition of TIC and Its Systemic Nature: Strengths and Challenges

4.3. Implementation of TIC Initiatives Through Staff Training and Support

4.4. Effects of TIC Initiatives

4.5. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Both references were included on the same line because they were related to the same evaluation. |

References

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. A Revised Inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse Negl., 2015, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Deneault, A.-A.; Racine, N.; Park, J.; Thiemann, R.; Zhu, J.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Williamson, T.; Fearon, P.; Cénat, J. M.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Moderators among Half a Million Adults in 206 Studies. World Psychiatry, 2023, 22, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; Coleman, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Milne, L.; Sell, J.; Daigneault, I. Trauma Experiences, Maltreatment-Related Impairments, and Resilience Among Child Welfare Youth in Residential Care. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict., 2011, 9, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, K.; Chamberland, C.; Lessard, G.; Clément, M.-È.; Wemmers, J.-A.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Gagné, M.-H.; Damant, D. Polyvictimization in a Child Welfare Sample of Children and Youths. Psychol. Violence, 2012, 2, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; p 27.

- Matte-Landry, A.; Collin-Vézina, D. Restraint, Seclusion and Time-out among Children and Youth in Group Homes and Residential Treatment Centers: A Latent Profile Analysis. Child Abuse Negl., 2020, 109, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A. R.; Hiller, R. M.; Halligan, S. L.; Lavi, I.; Macleod, J. A. A.; Wilkins, D. A Qualitative Investigation into Care-Leavers’ Experiences of Accessing Mental Health Support. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract., 2024, 97, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahr-Pederson, I.; Ershadi, A. E.; Hyland, P.; Hansen, M.; Perera, C.; Sheaf, G.; Bramsen, R. H.; Spitz, P.; Vallières, F. Polyvictimization and Psychopathology among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Studies Using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl., 2020, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J. I.; Toombs, E.; Radford, A.; Boles, K.; Mushquash, C. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Executive Function Difficulties in Children: A Systematic Review. Child Abuse Negl., 2020, 106, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, J.; Richard, M.-C.; Dufour, I.F.; Plourde, C. Les récits de vie des jeunes placés : vécu traumatique, stratégies pour y faire face et vision d’avenir. Criminologie 2023, 56, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kelder, R.; Van den Akker, A. L.; Geurts, H. M.; Lindauer, R. J. L.; Overbeek, G. Executive Functions in Trauma-Exposed Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology, 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarren-Sweeney, M. The Mental Health of Adolescents Residing in Court-Ordered Foster Care: Findings from a Population Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev., 2018, 49, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmingham, J. M.; Handley, E. D.; Rogosch, F. A.; Manly, J. T.; Cicchetti, D. Identifying Maltreatment Subgroups with Patterns of Maltreatment Subtype and Chronicity: A Latent Class Analysis Approach. Child Abuse Negl., 2019, 87, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J. J. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Am. Psychol., 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Singly, F. Penser Autrement La Jeunesse. Lien Soc. Polit. 2000, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supeno, E.; Bourdon, S. Bifurcations, Temporalités et Contamination Des Sphères de Vie. Parcours de Jeunes Adultes Non Diplômés et En Situation de Précarité Au Québec. Agora DébatsJeunesses, 2013, 65, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Blease, K.; Kerig, P. K. Emerging Adulthood. Child Maltreatment Dev. Psychopathol. Approach 2016, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M. E. The Difficult Transition to Adulthood for Foster Youth in the US: Implications for the State as Corporate Parent. Soc. Policy Rep., 2009, 23, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Kidd, S.; Schwan, K. Without a Home: The National Youth Homelessness Survey; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2016; p 126.

- Fournier, V.; Matte-Landry, A. L’insertion Professionnelle Des Jeunes Ayant Vécu Un Placement En Protection de La Jeunesse: Une Revue de La Portée; Centre de recherche universitaire sur les jeunes et les familles (CRUJeF). Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale, 2023; p 84.

- Spinelli, T. R.; Bruckner, E.; Kisiel, C. L. Understanding Trauma Experiences and Needs through a Comprehensive Assessment of Transition Age Youth in Child Welfare. Child Abuse Negl., 2021, 122, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaving Care and the Transition to Adulthood: International Contributions to Theory, Research, and Practice Get Access Arrow; Mann-Feder, V. R., Goyette, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, M. E.; Goyette, M.; Dumollard, M.; Ziani, M.; Picard, J. Portrait des jeunes ayant été placés sous les services de la protection de la jeunesse et leurs défis en emploi; INRS - Urbanisation Culture Société: Québec, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sacker, A.; Lacey, R. E.; Maughan, B.; Murray, E. T. Out-of-Home Care in Childhood and Socio-Economic Functioning in Adulthood: ONS Longitudinal Study 1971–2011. Child. Youth Serv. Rev., 2022, 132, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, S.; Palmer, L. Left behind? Educational Disadvantage, Child Protection, and Foster Care. Child Abuse Negl., 2024, 149, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, A. Mental Health and Homelessness Among Youth Aging Out of Foster Care: An Integrated Review. J. Stud. Res., 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Bellot, C.; Boisvert-Viens, J.; Fontaine, A. Itinérance, Judiciarisation et Marginalisation Des Jeunes Ex-Placés Au Québec. Chaire de Recherche Sur l’évaluation Des Actions Publiques à l’égard Des Jeunes et Des Populations Vulnérables., 2022.

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Bellot, C. The Covid-19 Pandemic and Needs of Youth Who Leave Care.; Chaire de recherche du Canada sur l’évaluation des actions publiques à l’égard des jeunes et des populations vulnérables, 2020; p 14.

- Pauzé, M.; Audet, M.; Pauzé, R. Soutenir l’intégration sociale de jeunes vulnérables devant composer avec les défis de transition vers l’âge adulte. Cah. Crit. Thérapie Fam. Prat. Réseaux, 2020, 64, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussières, E. L.; Dubé, M.; St-Germain, A.; Lacerte, D.; Bouchard, P.; Allard, M. L’efficacité et l’efficience Des Programmes d’accompagnement Des Jeunes Vers l’autonomie et La Préparation à La Vie d’adulte; UETMISS, CIUSSS de la Capitale-Nationale, installation Centre jeunesse de Québec, 2015; p 170.

- Heerde, J. A.; Hemphill, S. A.; Scholes-Balog, K. E. The Impact of Transitional Programmes on Post-Transition Outcomes for Youth Leaving out-of-Home Care: A Meta-Analysis. Health Soc. Care Community, 2018, 26, e15–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, H.; Smart, D.; Kerridge, G.; Currie, G.; Johnson, R.; Kaner, E.; Lynch, A.; Munro, E.; Swan, J.; McGoverrn, R. Moving from ‘What We Know Works’ to ‘What We Do in Practice’: An Evidence Overview of Implementation and Diffusion of Innovation in Transition to Adulthood for Care Experienced Young People. Child Fam. Soc. Work, 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS). Portrait Des Pratiques Visant La Transition à La Vie Adulte Des Jeunes Résidant En Milieu de Vie Substitut Au Québec; Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS), 2018; p 120.

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Tardif-Samson, A.; Gauthier-Davies, C. Rapport Sur Les Jeunes Participants Au Programme Qualification Jeunesse; Rapport de recherche; Chaire de recherche du Canada sur l’évaluation des actions publiques à l’égard des jeunes et des populations vulnérables, 2022; p 45.

- Child Welfare League of Canada. Equitable Standards for Transitions to Adulthood for Youth in Care; Child Welfare League of Canada, 2021; p 39.

- Zhang, S.; Conner, A.; Lim, Y.; Lefmann, T. Trauma-Informed Care for Children Involved with the Child Welfare System: A Meta-Analysis. Child Abuse Negl., 2021, 122, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminer, D.; Bravo, A. J.; Mezquita, L.; Pilatti, A.; Bravo, A. J.; Conway, C. C.; Henson, J. M.; Hogarth, L.; Ibáñez, M. I.; Kaminer, D.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adulthood Mental Health: A Cross-Cultural Examination among University Students in Seven Countries. Curr. Psychol., 2022, 42, 18370–18381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piel, M. H.; Lacasse, J. R. Responsive Engagement in Mental Health Services for Foster Youth Transitioning to Adulthood. J. Fam. Soc. Work, 2017, 20, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strolin-Goltzman, J.; Woodhouse, V.; Suter, J.; Werrbach, M. A Mixed Method Study on Educational Well-Being and Resilience among Youth in Foster Care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev., 2016, 70, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.; Park, C.; Jones, R.; Goodman, D.; Patel, M. Defining and Measuring Indicators of Successful Transitions for Youth Aging out of Child Welfare Systems: A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. Cogent Soc. Sci., 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte-Landry, A.; Brend, D.; Collin-Vézina, D. Le Pouvoir Transformationnel Des Approches Sensibles Au Trauma Dans Les Services à l’enfance et à La Jeunesse Au Québec. Trav. Soc., 2023, 69, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A. C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C. M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth., 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med., 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Fletcher, S.; Parslow, R.; Phelps, S.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R. A.; McFarlane kake, A.; Silove, D.; Creamer, M. Trauma at the Hands of Another: Longitudinal Study of Differences in the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Profile Following Interpersonal Compared with Noninterpersonal Trauma. J Clin Psychiatry, 2012, 73, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, W.; Rice, S.; Cohen, J.; Murray, L.; Schley, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S. Trauma-Focused Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for Interpersonal Trauma in Transitional-Aged Youth. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy, 2021, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Gisladottir, T.; Stefansdottir, R.; Johannsson, E.; Jakobsdottir, G.; Rognvaldsdottir, V. Health and Well-Being of University Students before and during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Gender Comparison. PloS One, 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2023.

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas., 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, R. E.; Westland, M. A.; Mo, E. A Trauma-Informed Care Approach to Supporting Foster Youth in Community College. In New Directions for Community Colleges; 2018; Vol. 2018, pp 49–58.

- Mendes, P.; Standfield, R.; Saunders, B.; McCurdy, S.; Walsh, J.; Turnbull, L.; Armstrong, E. Indigenous Care Leavers in Australia: A National Scoping Study; Report; Monash University, 2020; p 249.

- Mountz, S.; Capous-Desyllas, M.; Perez, N. Speaking Back to the System: Recommendations for Practice and Policy from the Perspectives of Youth Formerly in Foster Care Who Are LGBTQ. Child Welfare, 2020, 97, 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, A. Supporting Youth Aging out of Government Care with Their Transition to College. Thesis, Western University, 2019.

- Jivanjee, P.; Grover, L.; Thorp, K.; Masselli, B.; Bergan, J.; Brennan, E. M. Training Needs of Peer and Non-Peer Transition Service Providers: Results of a National Survey. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res., 2020, 47, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S. A Safe and Decent Place to Live: Towards a Housing First Framework for Youth; Canadian Homelessness Research Network, 2014; p 64.

- Gonzalez, R.; Cameron, C.; Klendo, L. The Therapeutic Family Model of Care: An Attachment and Trauma Informed Approach to Transitional Planning. Dev. Pract. Child Youth Fam. Work J., 2012, 32, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marlotte, L. 68.4 Bouncing Back: Resilience-Building in Foster Families and Youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 2017, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, C.; Pauter, S.; Ocampo, A.; Stokes, C.; Bruckner, E. Trauma-Informed Guiding Principles for Working with Transition Age Youth: Provider Fact Sheet, 2021.

- Child Protection Project Committee. Study Paper on Youth Aging into the Community; Study Paper 11; British Columbia Law Institute: Rochester, NY, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S. L. 49.2 Impact of the Leads (Learn - Educate - Achieve - Dream - Succeed) Program. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, J. K.; Hall, T. S.; Chua, J. C.; Ralston, K. G.; Leroux, D. F.; Belgrade, A.; Shattuck, S. Toxic Stress and Disconnection from Work and School among Youth in Detroit. J. Community Psychol., 2022, 50, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, A. T.; Mann-Feder, V.; Oterholm, I.; Refaeli, T. Supporting Transitions to Adulthood for Youth Leaving Care: Consensus Based Principles. Child. Youth Serv. Rev., 2020, 116, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, C. Best Practice Recommendations for Transitioning Adolescent Foster Girls. Scholarly Project, University of Utah, 2013.

- Ausikaitis, A. E. Empowering Homeless Youth in Transitional Living Programs: A Transformative Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Their Transition to Adulthood. Dissertation, Loyola University: Chicago, 2014.

- Spinelli, T. R.; Riley, T. J.; St Jean, N. E.; Ellis, J. D.; Bogard, J. E.; Kisiel, C. Transition Age Youth (TAY) Needs Assessment : Feedback from TAY and Providers Regarding TAY Services, Resources, and Training. Child Welfare, 2019, 97, 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. C.; Berragan, D. L. 1625 Independent People. Trauma Recovery Model Pilot; Evaluation report; University of Gloucestershire: Gloucester, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation (MDRC). Lessons from the Implementation of Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential, s.d. Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation (MDRC). Lessons from the Implementation of Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential, s.d.

- Trekson, L.; Wasserman, K.; Ho, V. Connecting to Opportunity; Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation (MDRC), 2019; p 150.

- Esaki, N.; Benamati, J.; Yanosy, S.; Middleton, J. S.; Hopson, L. M.; Hummer, V. L.; Bloom, S. L. The Sanctuary Model: Theoretical Framework. Fam. Soc., 2013, 94, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, S. A.; Gauvin, E.; Jamieson, A.; Rathgeber, M.; Faulkner-Gibson, L.; Bell, S.; Davidson, J.; Russel, J.; Burke, S. What Are Effective Strategies for Implementing Trauma-Informed Care in Youth Inpatient Psychiatric and Residential Treatment Settings? A Realist Systematic Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst., 2017, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, A. Trauma-Informed Care Implementation in the Child- and Youth-Serving Sectors: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil., 2020, 7, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, M.-E.; Matte-Landry, A.; Hivon, M.; Julien, G. La Pédiatrie Sociale En Communauté En Tant Qu’approche Sensible Au Trauma : Une Voie Légitime Vers La Transformation Des Services à l’enfance Au Québec. Trav. Soc., 2023, 69, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. D.; King, M. A.; Wissow, L. S. The Central Role of Relationships With Trauma-Informed Integrated Care for Children and Youth. Acad. Pediatr., 2017, 17, S94–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E. R.; Yackley, C. R.; Licht, E. S. Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Trauma-Informed Care Program within a Youth Residential Treatment Center and Special Needs School. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth, 2018, 35, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A. C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É. B.; Godfrey, C. M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth., 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulin, S. L’émergence de l’âge Adulte: De l’impact Des Référentiels Institutionnels En France et Au Québec 1. SociologieS 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velde, C. V. de. Devenir adulte: sociologie comparée de la jeunesse en Europe, 1re éd.; Lien social; Presses universitaires de France: Paris, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bargeman, M.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Trauma-Informed Care as a Rights-Based “Standard of Care”: A Critical Review. Child Abuse Negl., 2021, 119 Pt 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors [reference number] | Date | Type of document | Category of document | Objective | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ausikatis, A. E. [63] |

2014 | Thesis or dissertation | Importance or need for TIC; Assessment of TIC to support transition to adulthood | Explore the experiences of homeless young adults in transitional living programs (TLP). | Design and/or type of methods: Multiphase combination design; Mixed methods Methods: Surveys, questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups Time points: 2 time points (6 months delay) for surveys, questionnaires, and interviews; focus groups conducted in the 6 months delay. Participants: Homeless young adults including unaccompanied youth, runaways, throwaways, street-living youth, and youth aging out of foster care (18-21 years old) living in TLP. Participants took part in interviews (N=8) and focus groups (N=10). TIC approach: TLP based on the Sanctuary model which focuses on basic needs, independent living skills, educational and/or employment skills, increases in savings/income, clinical concerns, self-sufficiency and developmental growth, and transition to permanent housing. Program duration: The average length of stay is 6 months, but youth are allowed to stay up to two years. Outcomes: Mental and occupational health; sense of social support, independence, and belonging; support and services; goals; experiences in TLP. |

|

Baker, C., & Berragan, L. [65] |

2020 | Research report | Description of practices and policies; Assessment of TIC to support TA | Investigate the efficacy of the TRM model in helping practitioners to support care leavers and improve practice, knowledge, confidence, and understanding of a trauma-informed approach. | Design and/or type of methods: Mixed methods Methods: Self-report surveys (open-ended questions) and interviews with staff Time points: 2 for the surveys: initial and 3 months follow-up Participants: Staff members involved in the development and implementation of TRM in an organization serving young people leaving care or custody or at risk of entering custody. The initial survey was completed by 15 staff members, while the follow-up survey and interview were completed by 4 staff members. TIC approach: TRM draws together knowledge of attachment, trauma, criminology, and neurology to formulate interventions for children and young people with complex needs. Outcomes: Staff practice and knowledge, staff reflection on the impact of TRM on clients’ experiences and outcomes (e.g., mental health, life skills, independence, positive relationships). |

|

Butters, C. [62] |

2013 | Thesis or dissertation | Importance or need for TIC; Description of practices and policies | Present best practice recommendations for transitioning adolescent foster girls. | Design and/or type of methods: Review. Methods: Critical review of data, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials, and clinical practice guidelines relevant to adolescent foster girls transitioning to adulthood; Interviews and communication with stakeholders. |

|

Camp, J. K., Hall, T. S., Chua, J. C., Ralston, K. G., Leroux, D. F., Belgrade, A., & Shattuck, S. [60] |

2021 | Peer-reviewed article | Assessment of TIC to support TA | Determine if toxic stress exposure affected educational attainment and employment among youth. | Design and/or type of methods: Quantitative Methods: Secondary analysis of census data from the Detroit Jobs for Michigan Graduates (JMG) program. Time points: 1) intake; 2) during program enrollment; 3) following program completion. Participants: Youth (n=1934; 13-26 years old) who participated in the JMG program; 93.7% were from homes with low incomes; 4.9% were identified as “systems-involved”. To be enrolled in the JMG program, youth must have a minimum of four barriers across eight domains: educational; employment; disability and health; interpersonal and emotional; childcare and parenting; family; intergenerational; and basic needs. TIC approach: JMG comprises three different programs: in-school, out-of-school, and the LEAP program. It includes intake evaluations, specialized education/training courses, case management services, and job skills/career coaching. The LEAP program complements the out-of-school program for youth who have been identified as “system-involved” with a TIC approach, where cross-systems partnerships allow to meet gaps and unmet basic needs as well as providing additional leadership and skills-based training. Program duration: 2-3 years Outcomes: Achievement of one or more educational or employment goals such as graduating from high school, enrolling in college, earning a general education diploma, and/or becoming employed. |

|

Child Protection Project Committee [58] |

2021 | Government or organization document | Description of practices and policies | Review and compare legislative models that support policy and practice related to youth aging into the community. | Design and/or type of methods: Review Methods: Reviews of models (some including TIC principles) that support policy and practice related to youth aging out into the community. |

|

Gaetz, S. [54] |

2014 | Research report | Description of practices and policies | Provide a clear understanding of what Housing First is, and how it can work to support young people who experience or are at risk of homelessness. | Design and/or type of methods: NA (description of a program) Methods: Review of research, consultation, and interviews with key service providers and young people who have experienced homelessness. TIC approach: Housing First for youth with five kinds of supports (housing; health and wellbeing [including TIC]; access to income and education; complementary supports; and opportunities for meaningful engagement) to support housing and to facilitate TA. |

|

Gonzalez, R., Cameron, C., & Klendo, L. [55] |

2012 | Peer-reviewed article | Description of practices and policies | Examine how to ensure a successful TA for young people in care, relying on the Lighthouse Foundation TFMC. | Design and/or type of methods: NA (description of a model) Methods: NA TIC approach: The TFMC is an integrated model of therapeutic care where TAY in care during are encouraged to be active in education, work, and personal development, and participate in programs to address their psychological wellbeing. |

|

Hallett, R. E., Westland, M. A., & Mo, E. [49] |

2018 | Book chapter | Importance or need for TIC | Increase completion of community college and transition to four-year institutions; explore the importance of embedding a TIC approach for college students aging out of care. | Design and/or type of methods: Qualitative; constant comparative analysis Methods: Semi-structured interviews and documents review. Participants: 7 foster youth attending a community college and 8 stakeholders. |

|

Harder, A. T., Mann-Feder, V., Oterholm, I., & Refaeli, T. [61] |

2020 | Peer-reviewed article | Importance or need for TIC; Description of practices and policies | Propose principles that can support practice and policy in promoting successful TA for young care leavers. | Design and/or type of methods: Qualitative Methods: Participants nominated a principle that had significant implications for practice as well as strong research support. A smaller group reviewed and refined the principles in relation to research and eliminated redundancies. Participants: A network of researchers (15 academics from 14 countries) concerned with the transition experienced by TAYfrom public care participated in the nomination of principles. |

|

Hill, S. L. [59] |

2021 | Conference proceeding | Assessment of TIC to support transition to adulthood | Assess LEADS (Learn –Educate – Achieve – Dream – Succeed) and provide data on characteristics of the youth served, types of services provided, factors associated with success, and overall outcomes. | Design and/or type of methods: Mixed methods Methods: A 3-year evaluation of the LEADS program allowed to describe characteristics of the youth served, types of services provided, factors associated with success, and overall outcomes. Participants' perception of the program was also of interest. Time points: 1 Participants: Foster youth between the ninth and 12th grade or pursuing their General Educational Diploma (GED). TIC approach: LEADS, a trauma-informed, resiliency-based approach, which coordinates youth education assessments, creates individualized action plans, and advocates for support to meet academic demands. Program duration: Not specified Outcomes: Not specified |

|

Jivanjee, P., Grover, L., Thorp, K., Masseli, B., Bergan, J. & Brennan, E. M. [53] |

2019 | Peer-reviewed article | Importance or need for TIC | Assess service providers’ training needs and preferences to better serve TAY with mental health difficulties. | Design and/or type of methods: Cross-sectional participatory action research; Mixed methods Methods: Online survey (self-report questionnaires and open-ended questions) to assess service providers’ training needs and preferences. Time points: 1 Participants: 254 service providers working with TAY with mental health challenges and other needs. |

|

Kisiel, C., Pauters, S., Ocampo, A., Stokes, C., & Bruckner, E. [57] |

2021 | Government or organization document | Description of practices and policies | Recognize the impact of trauma on TAY by offering foundational principles for understanding and working with TAY. | Design and/or type of methods: NA (formulation of principles) Methods: Principles are informed from a range of perspectives, including NCTSN’s 12 Core Concepts, and experiences of youth, caregivers, and professionals. TIC approach: TIC principles for understanding and working with youth approaching transition from the child-serving system(s) (child welfare, juvenile justice, education, behavioral health, etc.) due to “aging out” or other circumstances. |

|

Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation [66] ; Trekson, L., Wasserman, K. & Ho, V.[1] [67] |

n.d.; 2019 | Government or organization document; Research report | Description of practices and policies; Assessment of TIC to support transition to adulthood | Description and evaluation of LEAP initiatives models (JAG and BoT) to serve youth. | Design and/or type of methods: Program evaluation; Mixed methods Methods: Site visits; interviews with participants; program participation data; financial data. Time points: 2 time points; years 2 and 3 or 4 of implementation for JAG, and years 2 and 3 of implementation for BoT Participants: 9 organizations offering JAG and 5 offering BoT comprising to up to 5000 participants (14-26 years old) with past or current experience in the foster care or juvenile or justice systems or with homelessness. TIC approach: The LEAP initiative aims to improve education and employment outcomes for youth who have a history of involvement in the foster care and/or justice systems, or who are experiencing homelessness. Two evidence-based models (JAG and BoT) were adapted to meet their needs, including support to address trauma they may have experienced in their lives as well as help to connect with postsecondary resources and programs. Outcomes: Implementation; Participants perspectives on their program experiences; Youth engagement; Factors facilitating or constraining participation; Education and employment; Cost. |

|

Marlotte, L. [56] |

2017 | Conference proceeding | Description of practices and policies | Explore the adaptation of FOCUS. | Design and/or type of methods: NA (clinical perspective) TIC approach: FOCUS (Families Over Coming Under Stress) is an evidence-based, skill-building preventive intervention for foster families and foster youth in college. |

|

Mendes, P., Sandfield, R., Saunders, B., McCurdy, S., Walsh, J., Turnbull, L., & Armstrong, E. [50] |

2020 | Research report | Importance or need for TIC | Investigate the numbers, needs, and outcomes of Indigenous care leavers and examine relevant funding, policy and practice. | Design and/or type of methods: Cross-sectional; Qualitative Methods: Focus groups and semi-structured interviews. Time points: 1 Participants: 53 key representatives of government departments (n=9), non-government organizations (n=32), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled organizations (n=12) in the leaving care sector. |

|

Mountz, S., Capous-Desyllas, M., & Perez, N. [51] |

2020 | Peer-reviewed article | Importance or need for TIC | Gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of youth formerly in foster care who are LGBTQ. | Design and/or type of methods: Cross-sectional community-based participatory research; Qualitative Methods: Photovoice and interviews on several themes related to TA (e.g., family history, transitioning out of care, mental health, substance use, identity, resilience). Time points: 1 Participants: 25 LGBTQ youth (18–26 years old) formerly in foster care. |

|

Schubert, A. [53] |

2019 | Thesis or dissertation | Importance or need for TIC | Create support and services that will foster college success. | Design and/or type of methods: Qualitative Methods: Consultation with youth and institutions. Participants: Youth in and aging out of care, post-secondary institutions with successful youth-in-care initiatives, community agencies, and alternate high school programs. |

|

Spinelli, T. R., Riley, T. J., St. Jean, N. E., Ellis, J. D., Bogard, J. E., & Kisiel, C. L. [64] |

2019 | Peer-reviewed article | Importance or need for TIC; Assessment of TIC to support transition to adulthood | Improve the quality of services, resources, and training for TAY providers. | Design and/or type of methods: Cross-sectional design; Mixed methods Methods: Written survey and focus groups assessing TAY and providers’ needs, strengths, barriers, and strategies for coping with trauma, as well as TIC resources and services, and perspectives on the most effective components of TIC staff training. Time points: 1 Participants: 95 providers who work with TAY and 34 TAY receiving services in child welfare (14-21 years old) TIC approach: TIC training (not otherwise specified). Program duration: Not specified Outcomes: Not specified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).