Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

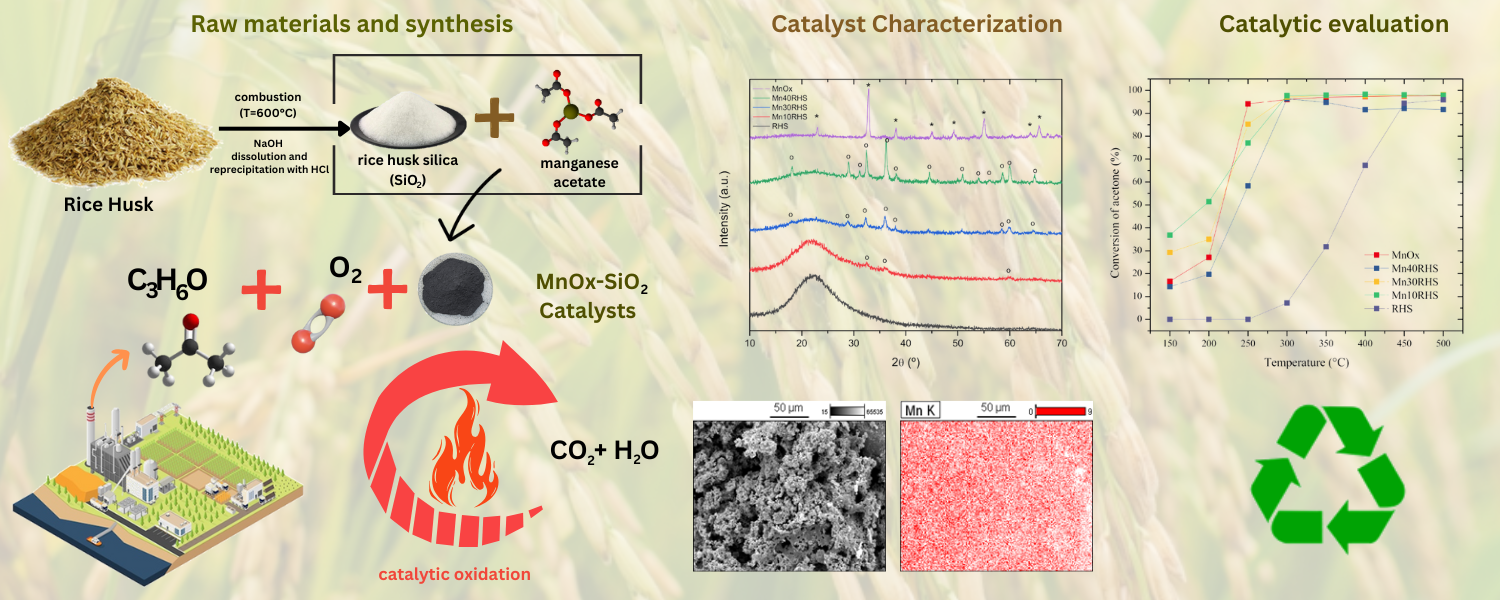

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of SiO2

2.2. Synthesis of Catalysts

2.3. Characterization Studies

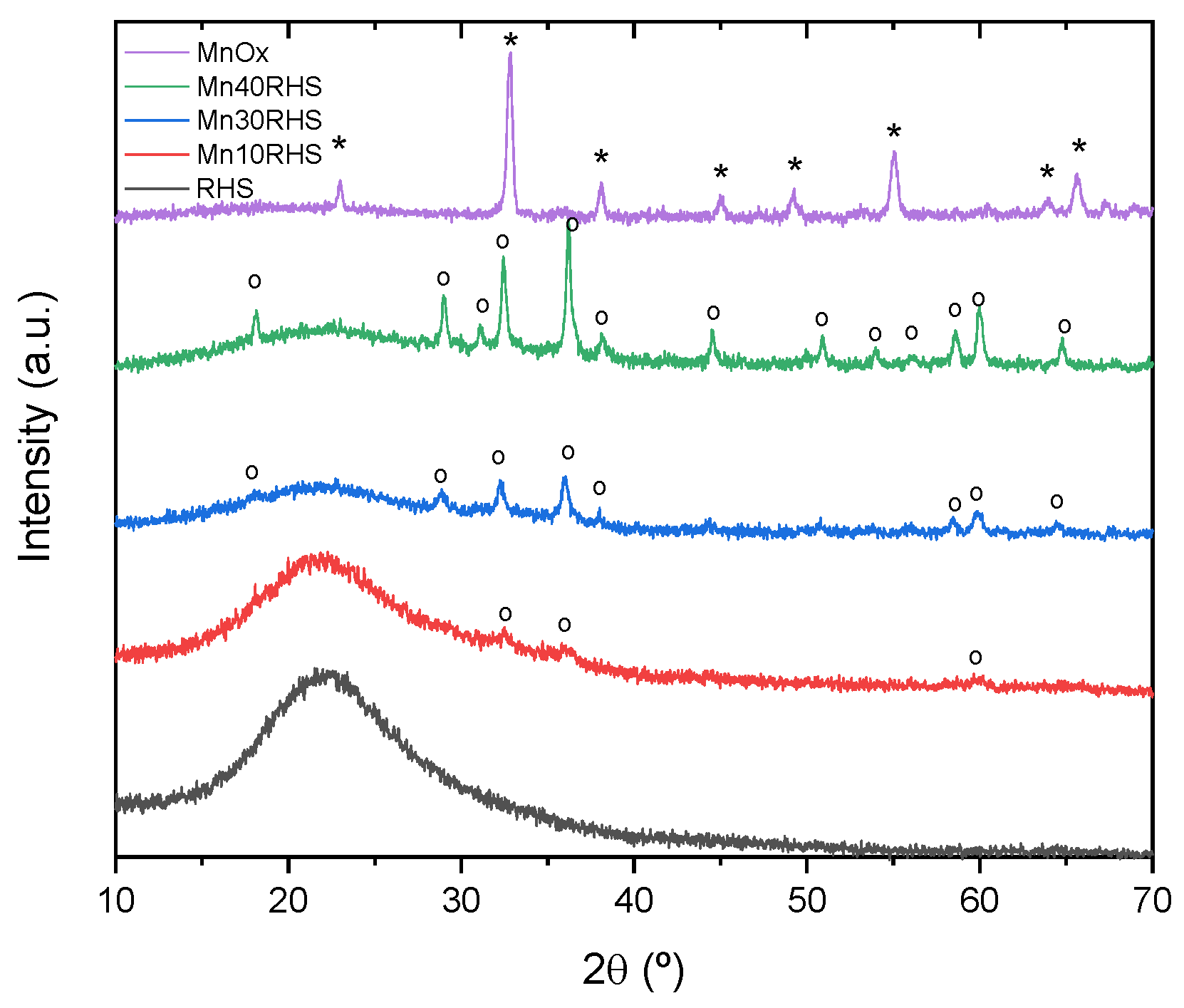

2.3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and Rietveld Analysis

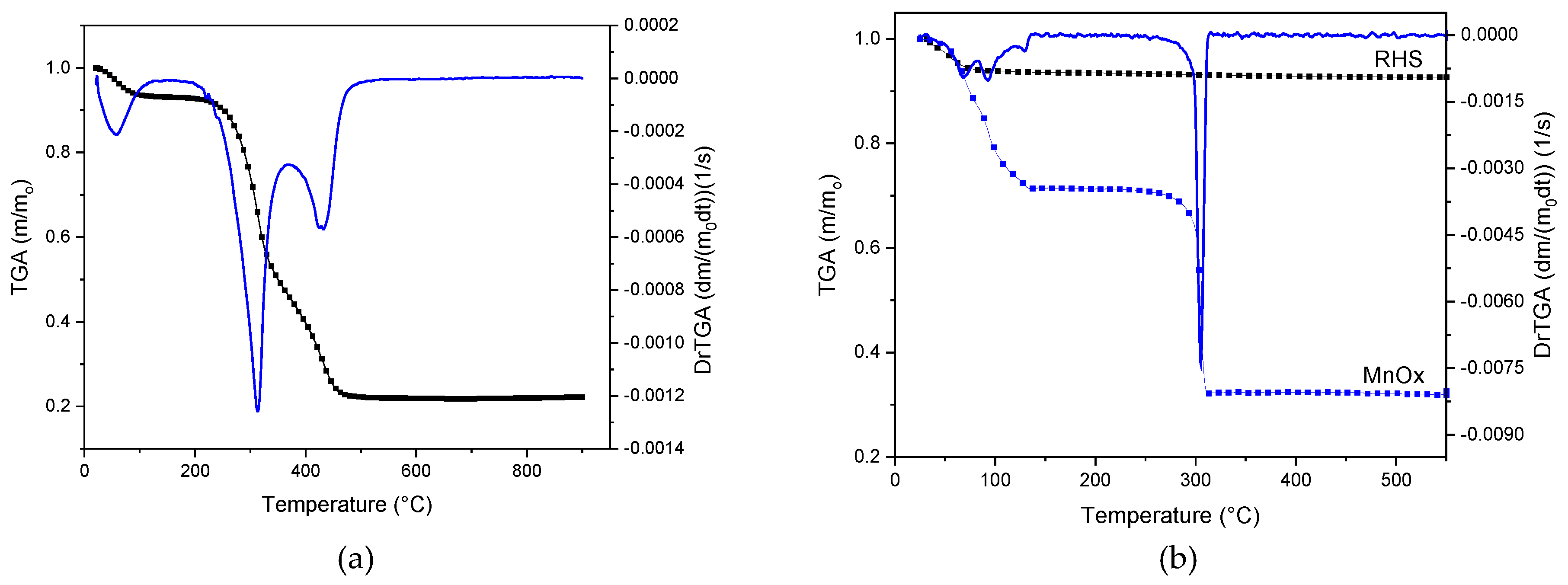

2.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.3.3. Microwave-Induced Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry

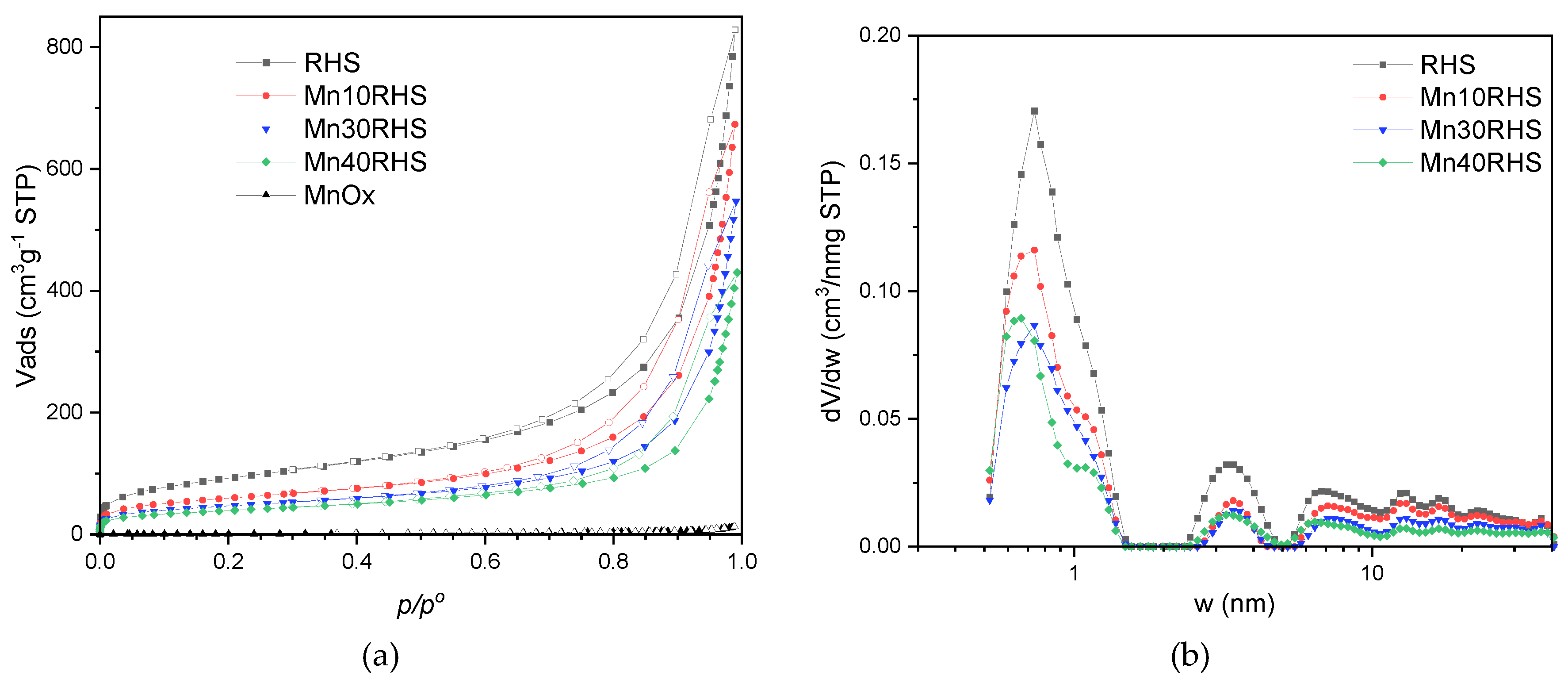

2.3.4. Textural Characterization

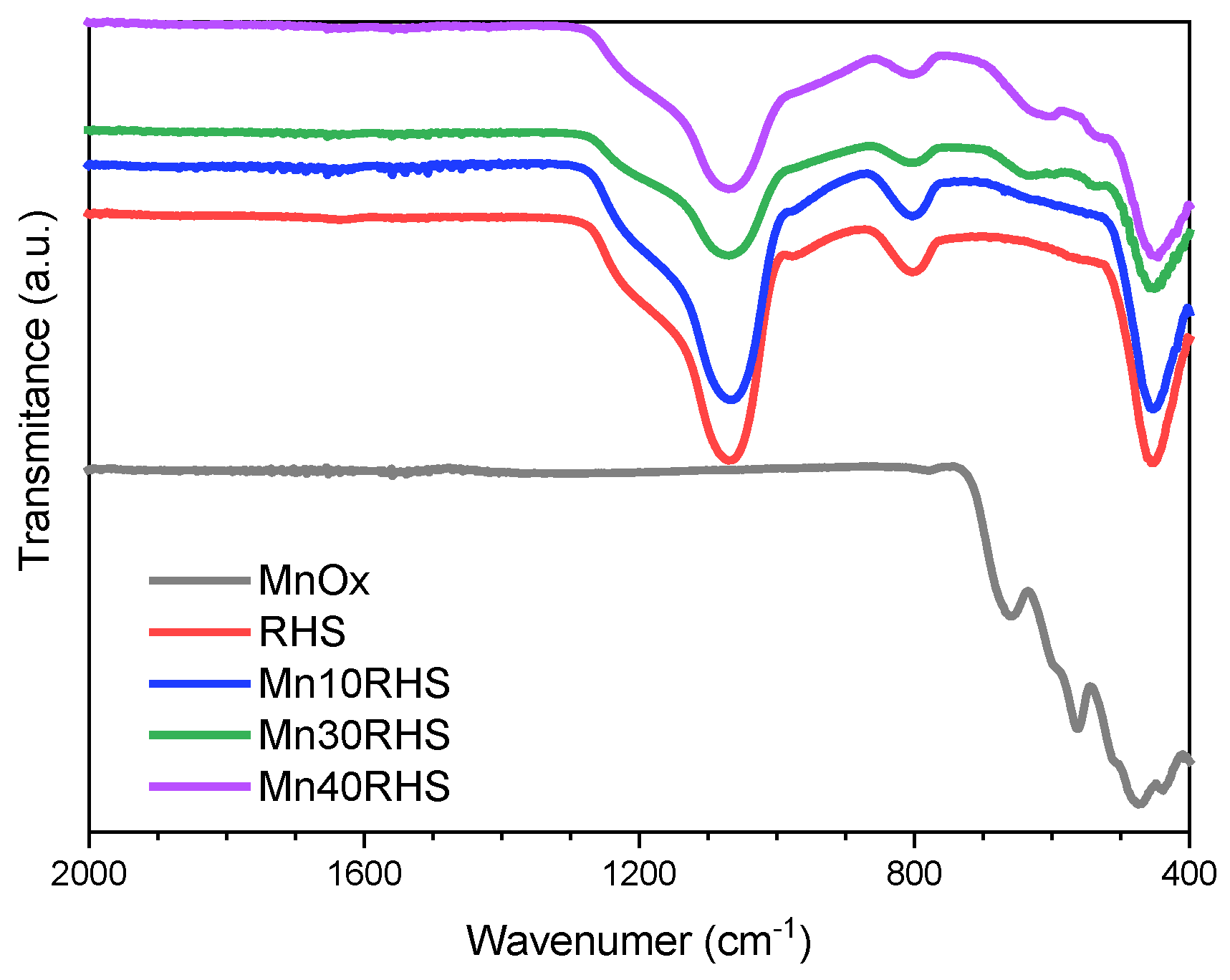

2.3.5. Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy

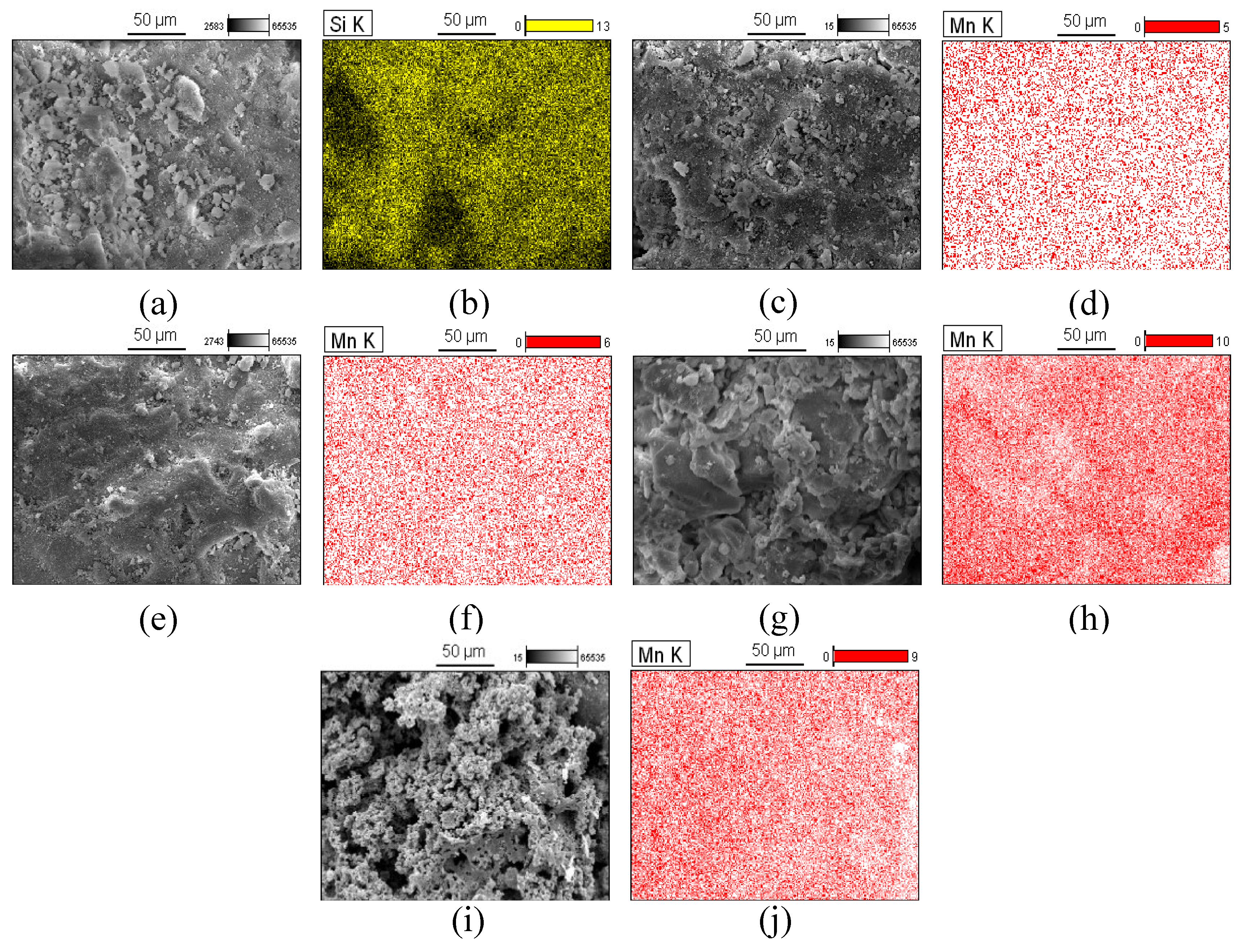

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersion Spectroscopy (EDS)

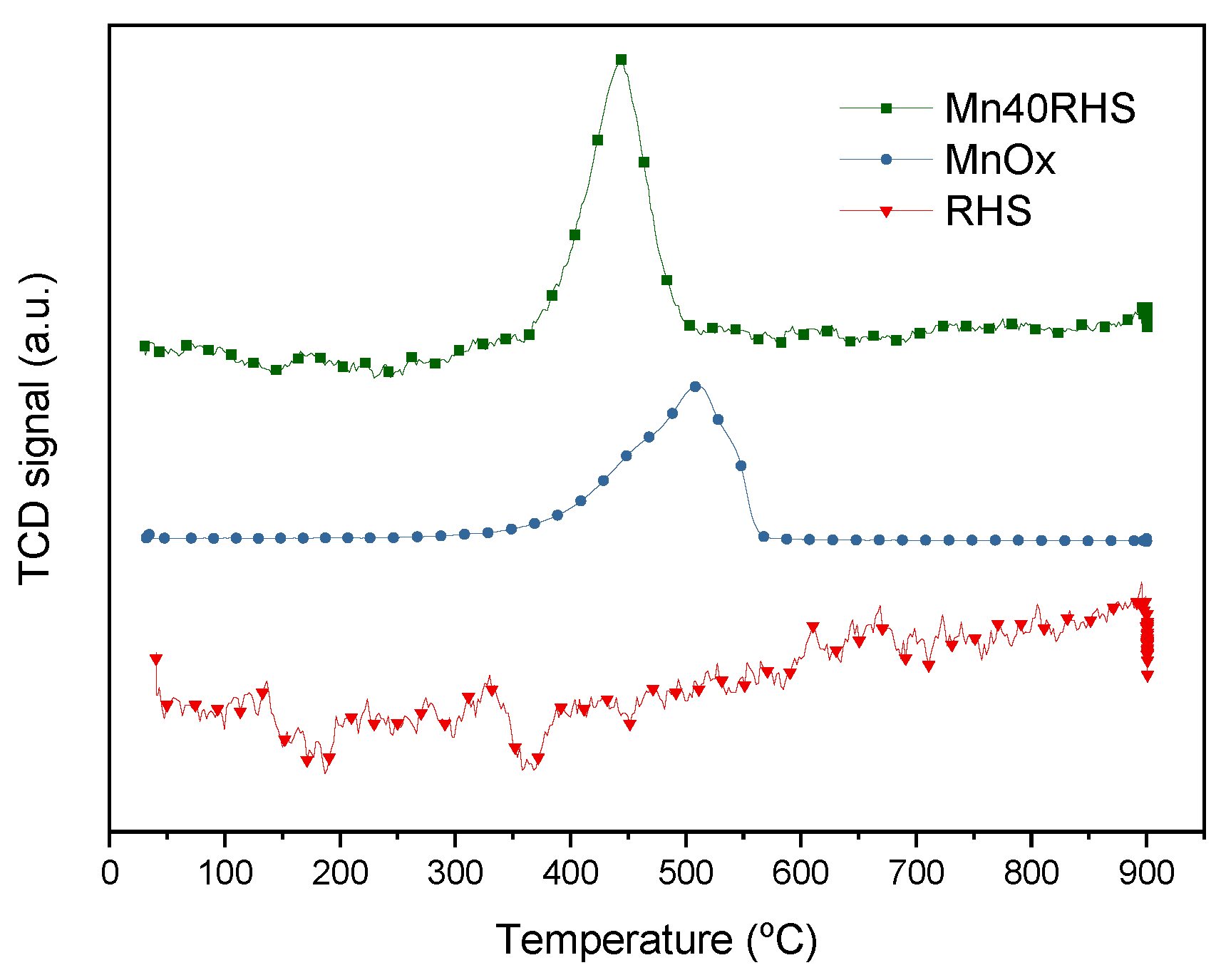

2.3.7. Temperature Programmed Reduction Mass Spectrometry (H2-TPR)

2.4. Catalytic Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization Results

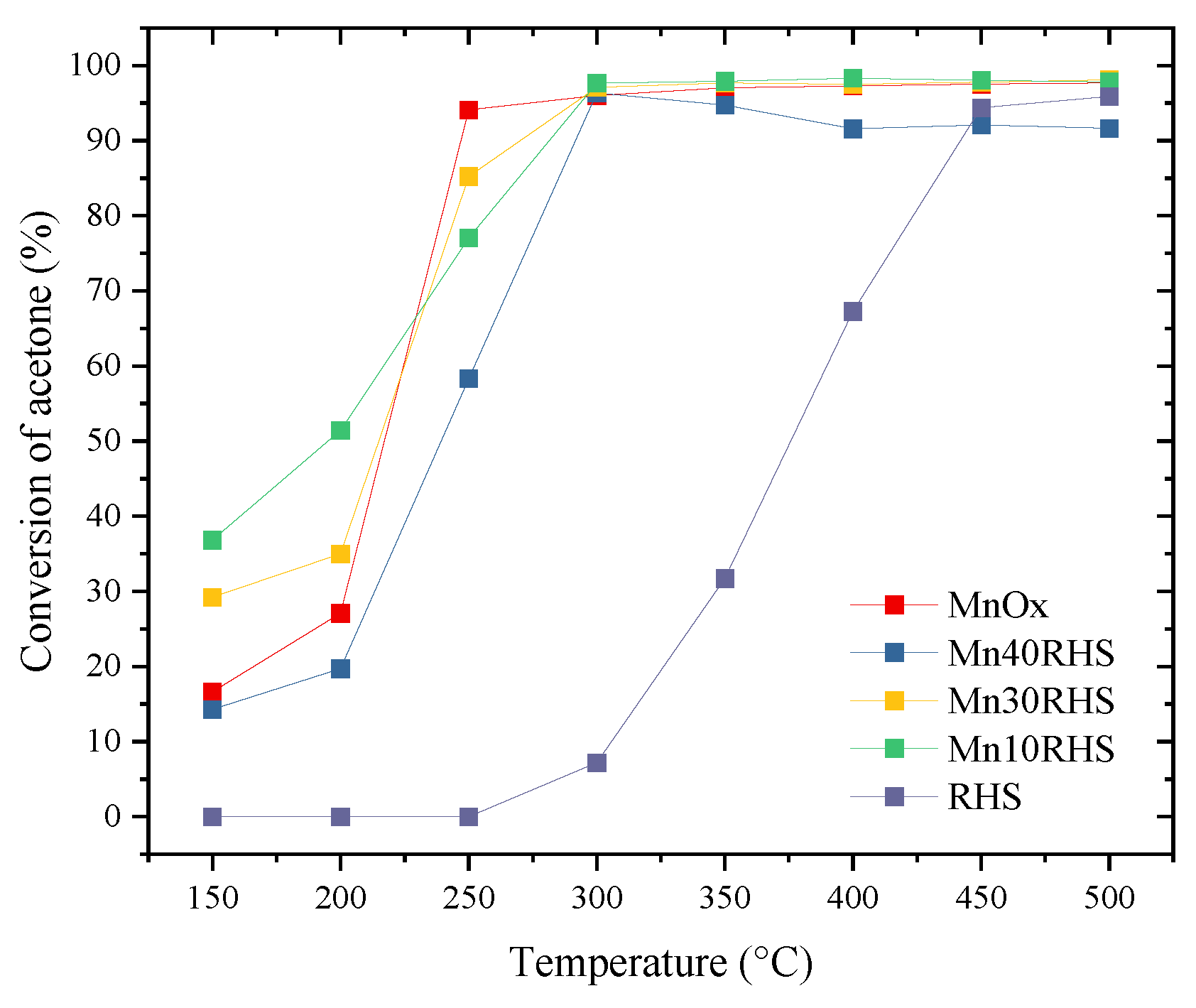

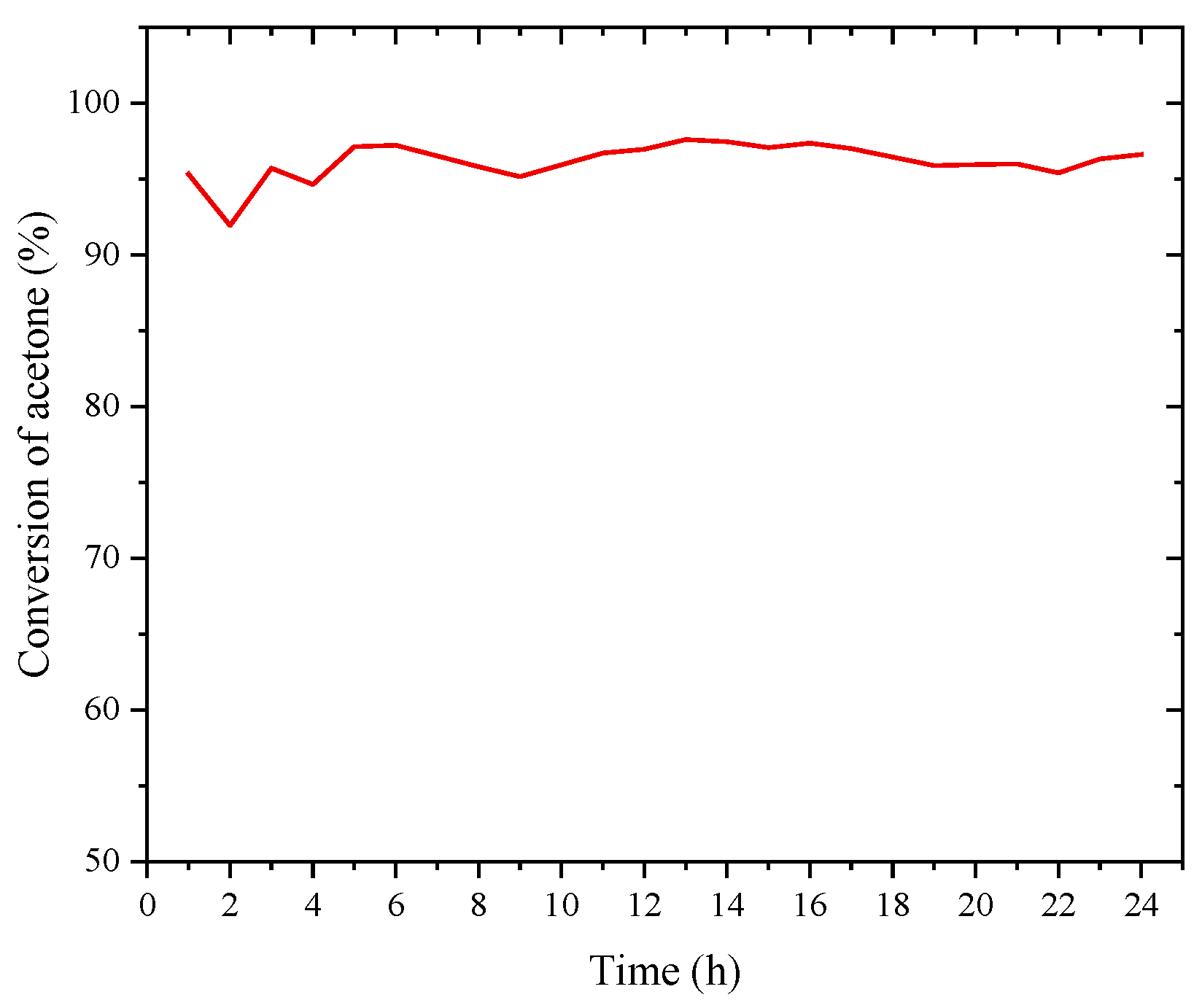

3.2. Activity Testing

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/infrastructure-industrialization/ (accessed May 1, 2024).

- Salgado, L. Arroz: situación y perspectivas. https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-ganaderia-agricultura-pesca/comunicacion/publicaciones/anuario-opypa-2022/analisis-sectorial-cadenas-productivas/arroz (accessed Mar 25, 2024).

- Uruguay XXI. Sector agrícola en Uruguay https://www.uruguayxxi.gub.uy/uploads/informacion/20c2018b1a2e68514020b55bcd11b62c6874640e.pdf (accessed Mar 25, 2024).

- Gebretatios, A. G.; Kadiri Kanakka Pillantakath, A. R.; Witoon, T.; Lim, J.-W.; Banat, F.; Cheng, C. K. Rice Husk Waste into Various Template-Engineered Mesoporous Silica Materials for Different Applications: A Comprehensive Review on Recent Developments. Chemosphere, 2023, 310, 136843. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Portugau, P.; Castiglioni, J.; Yermán, L.; Cuña, A. Evaluation of the Potential Utilization of Conventional and Unconventional Biomass Wastes Resources for Energy Production. Renewable Energy and Power Quality Journal, 2019, 511–515. [CrossRef]

- MGAP. Plantas de operación https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-industria-energia-mineria/publicaciones/plantas-operacion (accessed Mar 25, 2024).

- Xavier, L.; Rocha, M.; Pisani, J.; Zecchi, B. Aqueous Two-Phase Systems Based on Cholinium Ionic Liquids for the Recovery of Ferulic and p-Coumaric Acids from Rice Husk Hydrolysate. Applied Food Research, 2024, 4 (1), 100381. [CrossRef]

- Leal da Silva, E.; Torres, M.; Portugau, P.; Cuña, A. High Surface Activated Carbon Obtained from Uruguayan Rice Husk Wastes for Supercapacitor Electrode Applications: Correlation between Physicochemical and Electrochemical Properties. J Energy Storage, 2021, 44, 103494. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Portugau, P.; Castiglioni, J.; Cuña, A.; Yermán, L. Co-Combustion Behaviours of a Low Calorific Uruguayan Oil Shale with Biomass Wastes. Fuel, 2020, 266, 117118. [CrossRef]

- Adam, F.; Appaturi, J. N.; Iqbal, A. The Utilization of Rice Husk Silica as a Catalyst: Review and Recent Progress. Catal Today, 2012, 190 (1), 2–14. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C. A.; Fernandes, I. J.; Calheiro, D.; Kieling, A. G.; Brehm, F. A.; Rigon, M. R.; Berwanger Filho, J. A.; Schneider, I. A.; Osorio, E. Review of the Rice Production Cycle: By-Products and the Main Applications Focusing on Rice Husk Combustion and Ash Recycling. Waste Management & Research: The Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy, 2014, 32 (11), 1034–1048. [CrossRef]

- Santana Costa, J. A.; Paranhos, C. M. Systematic Evaluation of Amorphous Silica Production from Rice Husk Ashes. J Clean Prod, 2018, 192, 688–697. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J. de L.; Moreira, C. A.; Oliveira, A. G.; de Freitas, C. F.; Montanha, M. C.; Hechenleitner, A. A. W.; Pineda, E. A. G.; de Oliveira, D. M. F. Rice Husk-Derived Mesoporous Silica as a Promising Platform for Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery. Waste Biomass Valorization, 2022, 13 (1), 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Araichimani, P.; Prabu, K. M.; Kumar, G. S.; Karunakaran, G.; Surendhiran, S.; Shkir, Mohd.; AlFaify, S. Rice Husk-Derived Mesoporous Silica Nanostructure for Supercapacitors Application: A Possible Approach for Recycling Bio-Waste into a Value-Added Product. Silicon, 2022, 14 (15), 10129–10135. [CrossRef]

- Sinyoung, S.; Kunchariyakun, K.; Asavapisit, S.; MacKenzie, K. J. D. Synthesis of Belite Cement from Nano-Silica Extracted from Two Rice Husk Ashes. J Environ Manage, 2017, 190, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, B.; Libs, S.; Chaumette, P.; Kiennemann, A. Preparation and Characterization of Fischer–Tropsch Active Co/SiO2 Catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen, 1999, 186 (1–2), 145–168. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.; Cellier, C.; Gaigneaux, E. M.; Pirard, J.-P.; Heinrichs, B. Ag/SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and Pd/SiO2 Cogelled Xerogel Catalysts for Benzene Combustion: Relationships between Operating Synthesis Variables and Catalytic Activity. Catal Commun, 2007, 8 (8), 1244–1248. [CrossRef]

- Sitthisa, S.; Sooknoi, T.; Ma, Y.; Balbuena, P. B.; Resasco, D. E. Kinetics and Mechanism of Hydrogenation of Furfural on Cu/SiO2 Catalysts. J Catal, 2011, 277 (1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Peralta, Y. M.; Molina, R.; Moreno, S. Chemical and Structural Properties of Silica Obtained from Rice Husk and Its Potential as a Catalytic Support. J Environ Chem Eng, 2024, 12 (2), 112370. [CrossRef]

- Bratan, V.; Vasile, A.; Chesler, P.; Hornoiu, C. Insights into the Redox and Structural Properties of CoOx and MnOx: Fundamental Factors Affecting the Catalytic Performance in the Oxidation Process of VOCs. Catalysts, 2022, 12 (10), 1134. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wen, M.; Li, G.; An, T. Recent Advances in VOC Elimination by Catalytic Oxidation Technology onto Various Nanoparticles Catalysts: A Critical Review. Appl Catal B, 2021, 281, 119447. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yue, Y.; Qian, G. Low-Energy Production of a Monolithic Catalyst with MnCu-Synergetic Enhancement for Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds. J Environ Manage, 2023, 336, 117688. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. K. Diversity in the Family of Manganese Oxides at the Nanoscale: From Fundamentals to Applications. ACS Omega, 2020, 5 (40), 25493–25504. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; de los Santos, C.; Portugau, P.; Yeste, M. D. P.; Castiglioni, J. Utilization of a PILC-Al Obtained from Uruguayan Clay as Support of Mesoporous MnOx-Catalysts on the Combustion of Toluene. Appl Clay Sci, 2021, 201, 105935. [CrossRef]

- Gatica, J. M.; Castiglioni, J.; de los Santos, C.; Yeste, M. del P.; Cigredo, G.; Torres, M.; Vidal, H. Clay Honeycomb Monoliths as Support of Manganese Catalysts for VOCs Oxidation. International Journal of Chemical and Enviromental Engineering, 2015, 6 (4).

- Steven, S.; Restiawaty, E.; Pasymi, P.; Bindar, Y. An Appropriate Acid Leaching Sequence in Rice Husk Ash Extraction to Enhance the Produced Green Silica Quality for Sustainable Industrial Silica Gel Purpose. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng, 2021, 122, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Nzereogu, P. U.; Omah, A. D.; Ezema, F. I.; Iwuoha, E. I.; Nwanya, A. C. Silica Extraction from Rice Husk: Comprehensive Review and Applications. Hybrid Advances, 2023, 4, 100111. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, U.; Soltani, S.; Al-Resayes, S. I.; Nehdi, I. A. Metal Oxide Catalysts for Biodiesel Production. In Metal Oxides in Energy Technologies; Elsevier, 2018; pp 303–319. [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, H. M. A Profile Refinement Method for Nuclear and Magnetic Structures. J Appl Crystallogr, 1969, 2 (2), 65–71. [CrossRef]

- Mattos, B. D.; Rojas, O. J.; Magalhães, W. L. E. Biogenic SiO2 in Colloidal Dispersions via Ball Milling and Ultrasonication. Powder Technol, 2016, 301, 58–64. [CrossRef]

- Toby, B. H.; Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS-II : The Genesis of a Modern Open-Source All Purpose Crystallography Software Package. J Appl Crystallogr, 2013, 46 (2), 544–549. [CrossRef]

- Julien, C. M.; Massot, M.; Poinsignon, C. Lattice Vibrations of Manganese Oxides. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2004, 60 (3), 689–700. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A. L. The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Physical Review, 1939, 56 (10), 978–982. [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2015, 87 (9–10), 1051–1069. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, E.; Turco, M.; Russo, A.; Bagnasco, G.; Marchese, S.; Pernice, P.; Aronne, A. MnO x /ZrO2 Gel-Derived Materials for Hydrogen Peroxide Decomposition. J Solgel Sci Technol, 2011, 60 (3), 426–436. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M. S.; Razzak, S. A.; Hossain, M. M. Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) – A Review. Atmos Environ, 2016, 140, 117–134. [CrossRef]

- Mars, P.; van Krevelen, D. W. Oxidations Carried out by Means of Vanadium Oxide Catalysts. Chem Eng Sci, 1954, 3, 41–59. [CrossRef]

- Tichenor, B. A.; Palazzolo, M. A. Destruction of Volatile Organic Compounds via Catalytic Incineration. Environmental Progress, 1987, 6 (3), 172–176. [CrossRef]

- Gandı́a, L. M.; Vicente, M. A.; Gil, A. Complete Oxidation of Acetone over Manganese Oxide Catalysts Supported on Alumina- and Zirconia-Pillared Clays. Appl Catal B, 2002, 38 (4), 295–307. [CrossRef]

| Sample | SBET | Vtp | Vmp | Vµp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m2/g | cm3/g | |||

| RHS | 333 | 0.790 | 0.707 | 0.083 |

| Mn10RHS | 215 | 0.609 | 0.551 | 0.058 |

| Mn30RHS | 169 | 0.470 | 0.425 | 0.045 |

| Mn40RHS | 141 | 0.348 | 0.308 | 0.040 |

| MnOx | 2 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.000 |

| Parameter | Mn10RHS | Mn30RHS | Mn40RHS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 269 | 245 | 285 | |

| 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.85 | |

| 294 | 291 | 298 | |

| 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.94 | |

| - | 300 | 300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).