Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

17 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent and debilitating condition with significant social and public health implications due to its high morbidity and mortality rates. The World Health Organization recognizes COPD as a major global health challenge. Despite extensive research, the complex pathophysiology of COPD has hindered the development of precise treatments. Recent advancements in understanding the gut-lung axis and immunological mechanisms have opened new avenues for COPD management. This review delves into the pathophysiological aspects of COPD, highlighting the interplay between genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors. It emphasizes the critical role of the gut-lung axis in modulating pulmonary immunity and disease progression, presenting dysbiosis as a key factor exacerbating inflammation and COPD symptoms. Emerging therapeutic approaches, including the modulation of gut microbiota through probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary changes, show promise in improving COPD outcomes. Additionally, advancements in immunotherapies, such as monoclonal antibodies targeting specific cytokines and immune checkpoint inhibitors, offer the potential for reducing inflammation and enhancing lung function. Precision medicine, which customizes treatment based on individual genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, represents a significant stride toward more effective COPD management. This review also identifies crucial research gaps, such as the need for a comprehensive understanding of non-smoking-related COPD, reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis, and the long-term effects of novel therapies. Future research can pave the way for innovative therapeutic strategies and improved patient care by addressing these gaps. This comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of an integrative approach to COPD, combining pathophysiological insights, immunological perspectives, and cutting-edge therapies to enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by this chronic disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Lung Health

3. Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System

3.1. Normal Lung Function

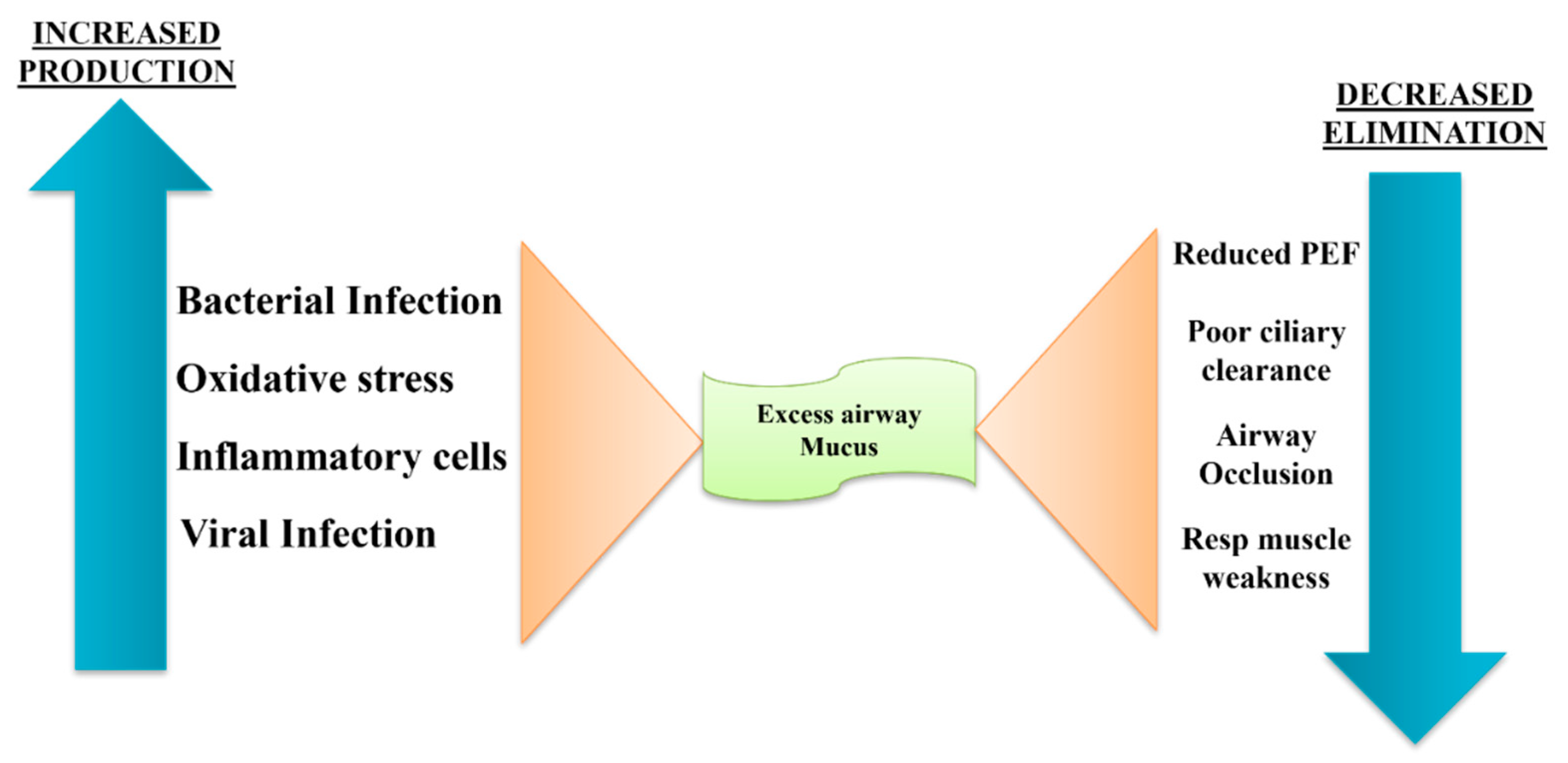

3.2. Pathophysiology of COPD

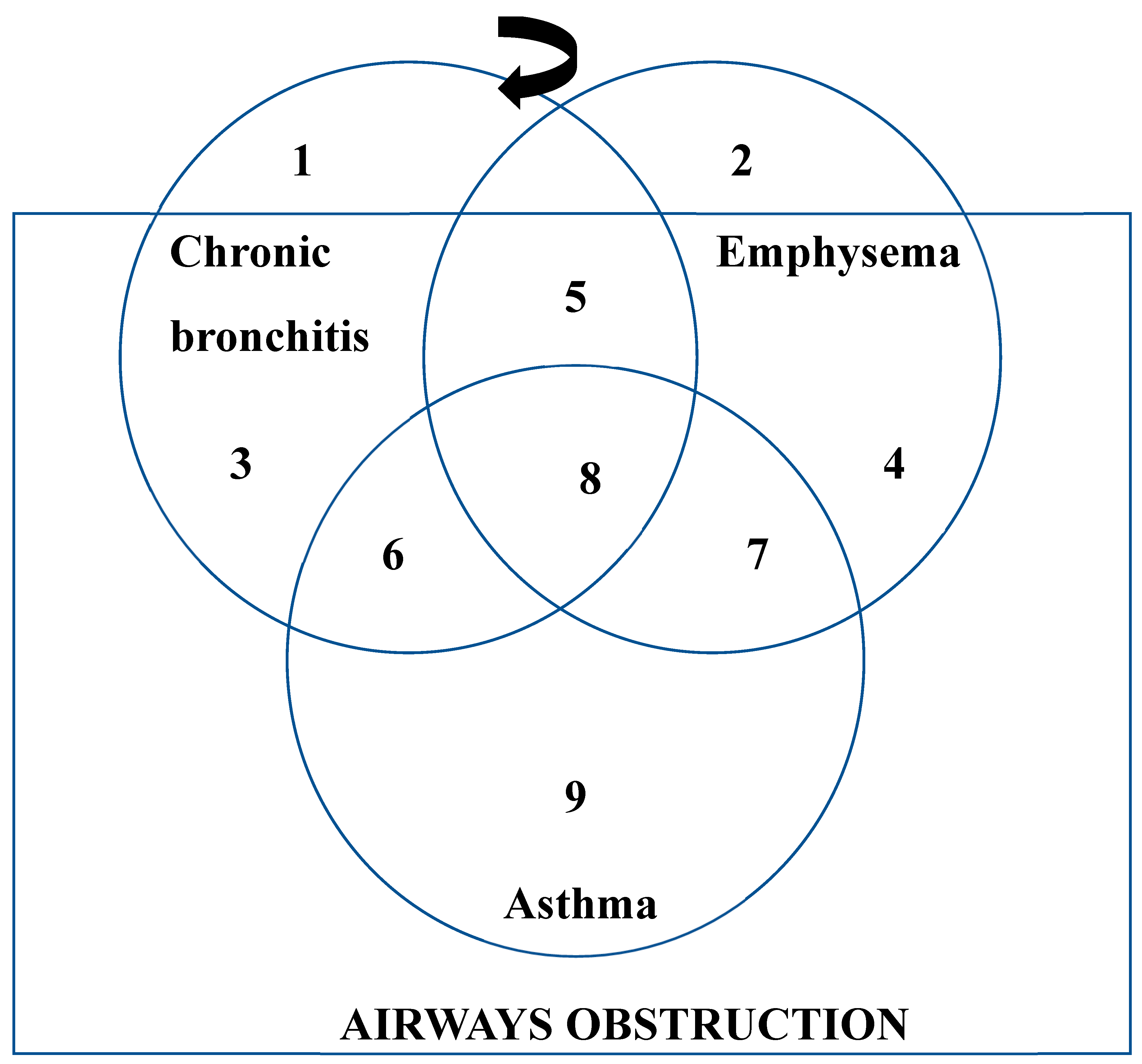

4. Types and Progression of COPD

4.1. Chronic Bronchitis

4.2. Emphysema

4.3. Asthma

5. Immunomodulatory Effects of Gut Microbiota in Respiratory Diseases

5.1. Role of Microbiome in Innate Immunity

5.2. Role of Microbiome in Adaptive Immunity

6. Immunological Perspective on COPD

7. Managing COPD: Treatment Approaches

8. Future Directions and Research Implications

8.1. Emerging Therapeutic Targets

- -

- Cytokines: Treatments aimed at IL-5, IL-4, and IL-13 have demonstrated potential in lowering inflammation and enhancing lung capacity. In individuals with eosinophilic COPD, for instance, mepolizumab and benralizumab (anti-IL-5) and dupilumab (anti-IL-4/IL-13) have shown promise [73].

- -

- Inhibitors of Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP): The anti-TSLP monoclonal antibody tezepelumab has demonstrated promise in lowering airway inflammation through the blockage of TSLP-mediated signaling pathways [74].

- -

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: By focusing on immune checkpoints like PD-1 and PD-L1, one can alter immunological responses, which may lessen inflammation and enhance COPD results [75].

8.2. Advances in Precision Medicine for COPD

- -

- Characterization of Endotypes and Phenotypes: By identifying particular endotypes and phenotypes, targeted treatments that target the underlying inflammatory mechanisms causing COPD can be developed [78].

- -

- Biomarker identification: By identifying biomarkers linked to particular endotypes, targeted medicines can be chosen with more efficacy, leading to better patient outcomes [79].

- -

-

Customized Treatment Plans: Based on lifestyle, genetic, and environmental information, customized treatment regimens are developed for each patient.Precision medicine has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of COPD by providing novel and efficient treatment alternatives that can greatly enhance both the prognosis and quality of life for patients [80].

8.3. Unexplored Areas of Gut-Lung Immunology

- -

- -

- Immune Modulation: Comprehending how microbial metabolites, like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), influence immune responses and mitigate lung inflammation.

- -

- Microbiota Transplantation: Examining the possibility of microbiota transplantation as a therapeutic approach to improve immunological function and restore healthy microbial communities.

9. Conclusion

References

- WHO. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd).

- Poh TY, Phua J, Lee KH, Lim TK. Understanding COPD-overlap syndromes. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11(4):285-98. [CrossRef]

- Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1-18. [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd.

- Raherison C, Girodet PO. Epidemiology of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2009;18(114):213-21. [CrossRef]

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-43.

- Breyer-Kohansal R, Hartl S, Burghuber OC, Wouters EF. The LEAD (Lung, Heart, Social, Body) study: objectives, methodology, and external validity of the population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol. 2019;29(8):315-24. [CrossRef]

- Agustí A, Faner R. COPD beyond smoking: new paradigm, novel opportunities. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(5):324-6. [CrossRef]

- Postma DS, Siafakas N, editors. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In: Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Eur Respir Mon. 1998;7:41–73.

- Gilliland FD, Li YF, Peters JM. Effects of glutathione S-transferase M1, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and environmental tobacco smoke on asthma and wheezing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(4):457-63. [CrossRef]

- Keatings VM, Collins PD, Scott DM, Barnes PJ. Differences in interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in induced sputum from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(2):530-4. [CrossRef]

- Lim SA, Roche WR, Belvisi MG, Walls AF, Holgate ST, Macedo P, et al. Balance of matrix metalloprotease-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 from alveolar macrophages in cigarette smokers: regulation by interleukin-10. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4):1355-60.

- Takizawa H, Tanaka M, Takami K, Ohtoshi T, Ito K, Satoh M, et al. Increased expression of transforming growth factor-β 1 in small airway epithelium from tobacco smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(6):1476-83. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Li Y, Xu Y, Zhang G, Zhang L, Huang J, et al. Emerging therapeutic approaches for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: focus on immunotherapy and precision medicine. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):172. [CrossRef]

- Chung KF. The role of airway smooth muscle in the pathogenesis of airway wall remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(4):347-54. [CrossRef]

- Anatomy and Physiology of Respiratory System Relevant to Anaesthesia [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 29]. Available from: http://www.ijaweb.org.

- Mittman C, Edelman NH, Norris AH. Relationship between chest wall and pulmonary compliance with age. J Appl Physiol. 1965;20:211–16. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Nusrath A, Tong JL, Smith JE. Pathways through the nose for nasal intubation: A comparison of three endotracheal tubes. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:269–74. [CrossRef]

- Ratnovsky A, Elad D, Halpern P. Mechanics of respiratory muscles. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;163:82–89. [CrossRef]

- Stevens JJWM, Jones JG. Functional anatomy and pathophysiology of the upper airway. Baillière’s Clin Anaesthesiol. 1995;9:213–34. [CrossRef]

- Hudgel DW, Hendricks C. Palate and hypopharynx – sites of inspiratory narrowing of the upper airway during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:1542–7. [CrossRef]

- Wheatley JR, Kelly WT, Tully A, Engel LA. Pressure-diameter relationships of the upper airway in awake supine subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70(5):2242–51.

- Mittman C, Edelman NH, Norris AH, et al. Relationship between chest wall and pulmonary compliance with age. J Appl Physiol. 1965;20:1211–16. [CrossRef]

- Tolep K, Higgins N, Muza S, et al. Comparison of diaphragm strength between healthy adult elderly and young men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:677–82. [CrossRef]

- Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, et al. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:725–34.

- Zeleznik J. Normative aging of the respiratory system. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Stam H, Hrachovina V, Stijnen T, et al. Diffusing capacity dependent on lung volume and age in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2356–63. [CrossRef]

- MacNee W. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(4):258–66. [CrossRef]

- Bates DV. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(11):600–5. [CrossRef]

- Snider GL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Risk factors, pathophysiology, and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:411–29.

- Burgel PR, Nesme-Meyer P, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, Roche N, Perez T, et al. Cough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjects. Chest. 2009;135(4):975–82. [CrossRef]

- Kim V, Han MK, Vance GB, Make BJ, Newell JD, Hokanson JE, et al. The chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD: an analysis of the COPDGene Study. Chest. 2011;140(3):626–33. [CrossRef]

- Kim V, Criner GJ. Chronic Bronchitis and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):228–37. [CrossRef]

- Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709–21. [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen M, Notkola IL, Nissinen A, Tukiainen H, Koskela H. Thirty-year cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis and COPD in relation to 30-year pulmonary function and 40-year mortality: a follow-up in middle-aged rural men. Chest. 2006;130(4):1129–37. [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, García-Río F, Muñoz L, Duran-Tauleria E, Sánchez G, et al. Chronic respiratory symptoms, spirometry and knowledge of COPD among general population. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):1973–80. [CrossRef]

- Ebert RV, Terracio MJ. The bronchiolar epithelium in cigarette smokers. Observations with the scanning electron microscope. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;111(1):4–11.

- Deshmukh HS, Shaver CM, Case LM, Dietsch M, Wesselkamper SC, Hardie WD, et al. Metalloproteinases mediate mucin 5AC expression by epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;171(4):305–14. [CrossRef]

- Burgel PR, Nadel JA. Roles of epidermal growth factor receptor activation in epithelial cell repair and mucin production in airway epithelium. Thorax. 2004;59(11):992–6. [CrossRef]

- Holtzman MJ, Byers DE, Alexander-Brett JM, Wang X. Acute and chronic airway responses to viral infection: implications for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(2):132–40. [CrossRef]

- Innes AL, Carrington SD, Thornton DJ, Kirkham S, Rousseau K, Dougherty RH, et al. Epithelial mucin stores are increased in the large airways of smokers with airflow obstruction. Chest. 2006;130(4):1102–8. [CrossRef]

- Hogg JC, Chu FS, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2645–53. [CrossRef]

- James AL, Wenzel S. Clinical relevance of airway remodelling in airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(1):134–55. [CrossRef]

- Macklem PT, Proctor DF, Hogg JC. The stability of peripheral airways. Respir Physiol. 1970;8(2):191–203. [CrossRef]

- Kim V, Criner GJ. Chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):228–37. [CrossRef]

- Filley GF. Emphysema and chronic bronchitis: clinical manifestations and their physiologic significance. Med Clin North Am. 1967;51(2):283–92. [CrossRef]

- Sahebjami H, Diaz PT, Clanton TL, Pacht ER. Emphysema-like changes in HIV. Ann Intern Med. 2008;116(10):876. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein R, Da Ma H, Ghezzo H, Whittaker K, Fraser RS, Cosio MG. Morphometry of small airways in smokers and its relationship to emphysema type and hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(1):267–76. [CrossRef]

- Celli BR. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from unjustified nihilism to evidence-based optimism. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(1):58–65. [CrossRef]

- The definition of emphysema. Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Division of Lung Diseases workshop. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132(1):182–5.

- Hayes JA, Korthy A, Snider GL. The pathology of elastase-induced panacinar emphysema in hamsters. J Pathol. 1975;117(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi M, Yamada G, Koba H, Takahashi H. Classification of centrilobular emphysema based on CT-pathologic correlations. Open Respir Med J. 2012;6(1):155. [CrossRef]

- López-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. [CrossRef]

- Pons J, Sauleda J, Ferrer JM, et al. Blunted γδ T-lymphocyte response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:441–6.

- McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, et al. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1567–75. [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzo G, Rossi A, De Falco S, et al. Mechanical ventilation and COPD: from pathophysiology to ventilatory management. Minerva Med. 2022;113(3):460–70. [CrossRef]

- Leap J, Hamilton D, Wilkerson P, et al. Pathophysiology of COPD. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2021;44(1):2–8. [CrossRef]

- MacNee W. ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pathology, pathogenesis, and pathophysiology. BMJ. 2006;332(7551):1202–4.

- Tian P, Wen F. Clinical significance of airway mucus hypersecretion in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Transl Int Med. 2015;3(3):89–92. [CrossRef]

- Berg K, Wright JL. The pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: progress in the 20th and 21st centuries. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(12):1423–8. [CrossRef]

- Kiowski W, Linder L, Stoschitzky K, et al. Diminished vascular response to inhibition of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and enhanced vasoconstriction to exogenously administered endothelin-1 in clinically healthy smokers. Circulation. 1994;90(1):27–34. [CrossRef]

- Masoli, M., Fabian, D., Holt, S., Beasley, R. and (2004), The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy, 59: 469-478. [CrossRef]

- Better understanding of childhood asthma, towards primary prevention: are we there yet? Consideration of pertinent literature.

- 64. Patterns of growth and decline in lung function in persistent childhood asthma.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators,Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.Lancet. 2016; 388: 1459-1544.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention GINA, (2015).

- Lange P, Parner J, Vestbo J, Schnohr P, Jensen G. A 15-year follow-up study of ventilatory function in adults with asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:1194–1200. [CrossRef]

- Gerth van Wijk RG, de Graaf-in’t Veld C, Garrelds IM. Nasal hyperreactivity. Rhinology. 1999;37(2):50–5.

- Van Gerven L, Steelant B, Hellings PW. Nasal hyperreactivity in rhinitis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Allergy. 2018;73:1784. [CrossRef]

- Schleich, F.; Brusselle, G.; Louis, R.; Vandenplas, O.; Michils, A.; Pilette, C.; Peche, R.; Manise, M.; Joos, G. Heterogeneity of phenotypes in severe asthmatics. The Belgian Severe Asthma Registry (BSAR). Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 1723–1732. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.K.; Bush, A.; Stokes, J.; Nair, P.; Akuthota, P. Eosinophilic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 8, 465–473.

- Diamant, Z.; Vijverberg, S.; Alving, K.; Bakirtas, A.; Bjermer, L.; Custovic, A.; Dahlen, S.; Gaga, M.; van Wijk, R.G.; Del Giacco, S.; et al. Toward clinically applicable biomarkers for asthma: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2019, 74, 1835–1851. [CrossRef]

- J. Bousquet, R. Lockey, H.J. MallingAllergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. A WHO position paper J Allergy Clin Immunol, 102 (1998), pp. 558-562.

- K. Okubo, Y. Kurono, K. Ichimura, M. Enomoto, Y. Okamoto, Y. Kawauchi, et al. (Eds.), [Practical Guideline for the Management of Allergic Rhinitis in Japan] (8th ed.), Life Science, Tokyo (2016)(in Japanese).

- Haahtela, T, Jarvinen, M, Kava, T, et al. Comparison of a β2-agonist, terbutaline, with an inhaled corticosteroid, budesonide, in newly detected asthma. N Engl J Med 1991;325:388-392.

- Takaku, Y.; Nakagome, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nishihara, F.; Soma, T.; Hagiwara, K.; Kanazawa, M.; Nagata, M. Changes in airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness after inhaled corticosteroid cessation in allergic asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2010 . [CrossRef]

- Erminia Ridolo, Francesco Pucciarini, Maria Cristina Nizi, Eleni Makri, Paola Kihlgren, Lorenzo Panella & Cristoforo Incorvaia (2020) Mabs for treating asthma: omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab, Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16:10, 2349-2356. [CrossRef]

- Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, et al, 2018. Nano-based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 16, Pages- 1-33. [CrossRef]

- Buxton DB, Lee SC, Wickline SA, et al, 2003. Recommendations of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Nanotechnology Working Group. Circulation, 108(22), Pages- 2737-2742. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi YK, Hughes L, Baabdullah AM, et al, 2022. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 66, Pages- 102542. [CrossRef]

- Lane S, Molina J, Plusa T. An international observational prospective study to determine the cost of asthma exacerbations (COAX).Respir Med2006;100:434–450. [CrossRef]

- Hoskins G, McCowan C, Neville RG, Thomas GE, Smith B, Silverman S. Risk factors and costs associated with an asthma attack.Thorax2000;55:19–24. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury NK, Choudhury R, Gogoi B, Chang CM, Pandey RP. Microbial Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and their Application. Curr Drug Targets. 2022;23(7):752-760. [CrossRef]

- Pandey RP, Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Emerging Concern with Imminent Therapeutic Strategies for Treating Resistance in Biofilm. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Apr 2;11(4):476. [CrossRef]

- Pandey RP, Mukherjee R, Priyadarshini A, Gupta A, Vibhuti A, Leal E, Sengupta U, Katoch VM, Sharma P, Moore CE, Raj VS, Lyu X. Potential of nanoparticles encapsulated drugs for possible inhibition of the antimicrobial resistance development. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Sep;141:111943. [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Y., Pandey, R. P., Dutt, M., Gupta, A., Vibhuti, A., Raj, V. S., ... & Priyadarshini, A. (2023). Liposomes and phytosomes: Nanocarrier systems and their applications for the delivery of phytoconstituents. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 491, 215251. [CrossRef]

- Pandey RP, Vidic J, Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Experimental Methods for the Biological Evaluation of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Risks. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Feb 11;15(2):612. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Dhiman R, Prudencio CR, da Costa AC, Vibhuti A, Leal E, Chang CM, Raj VS, Pandey RP. Chitosan: Applications in Drug Delivery System. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2023;23(2):187-191. [CrossRef]

- Ruby M, Gifford CC, Pandey R, Raj VS, Sabbisetti VS, Ajay AK. Autophagy as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Kidney Disease and the Roles of TGF-β1 in Autophagy and Kidney Fibrosis. Cells. 2023 Jan 26;12(3):412. [CrossRef]

- Gunjan, Vidic J, Manzano M, Raj VS, Pandey RP, Chang CM. Comparative meta-analysis of antimicrobial resistance from different food sources along with one health approach in Italy and Thailand. One Health. 2022 Dec 22;16:100477. [CrossRef]

- Khatri P, Rani A, Hameed S, Chandra S, Chang CM, Pandey RP. Current Understanding of the Molecular Basis of Spices for the Development of Potential Antimicrobial Medicine. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Jan 29;12(2):270. [CrossRef]

- Pandey RP, Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance system mapping in different countries. Drug Target Insights. 2022 Nov 30;16:36-48. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, R Prudencio C, da Costa AC, Leal E, Chang CM, Pandey RP. Systematic Surveillance and Meta-Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Food Sources from China and the USA. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Oct 25;11(11):1471. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi S, Khatri P, Fatima Z, Pandey RP, Hameed S. A Landscape of CRISPR/Cas Technique for Emerging Viral Disease Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Progress and Prospects. Pathogens. 2022 Dec 29;12(1):56. [CrossRef]

- Tinker RJ, da Costa AC, Tahmasebi R, Milagres FAP, Dos Santos Morais V, Pandey RP, José-Abrego A, Brustulin R, Rodrigues Teles MDA, Cunha MS, Araújo ELL, Gómez MM, Deng X, Delwart E, Sabino EC, Leal E, Luchs A. Norovirus strains in patients with acute gastroenteritis in rural and low-income urban areas in northern Brazil. Arch Virol. 2021 Mar;166(3):905-913. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TTH, Pandey RP, Parajuli P, Han JM, Jung HJ, Park YI, Sohng JK. Microbial Synthesis of Non-Natural Anthraquinone Glucosides Displaying Superior Antiproliferative Properties. Molecules. 2018 Aug 28;23(9):2171. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi R, Srivastava M, Singh B, Sharma S, Pandey RP, Asthana S, Kumar D, Raj VS. Identification and validation of potent Mycobacterial proteasome inhibitor from Enamine library. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(19):8644-8654. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).