1. Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) remains a significant global health challenge, leading to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Characterized by progressive and irreversible airflow limitation, COPD exacerbations—acute episodes of symptom worsening—accelerate disease progression, compromise patient quality of life, and increase healthcare utilization [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Thus, preventing exacerbations has become a central goal in COPD management to mitigate poor outcomes, including heightened mortality risk [

9,

10].

Over recent decades, treatment strategies have evolved beyond improving lung function to focus on stabilizing the disease and reducing exacerbations [

7,

11,

12]. Early identification of at-risk patients is crucial for enabling timely interventions that can prevent hospitalizations and slow disease progression [

9,

13]. Current guidelines, such as those from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) and the Spanish COPD guide (GesEPOC), classify patients as high risk only if they experience two or more moderate exacerbations or a single severe exacerbation [

1,

11]. However, emerging evidence indicates that these criteria may overlook patients with early signs of instability, such as those who experience only one moderate exacerbation or frequently use short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Frequent SABA use (≥3 canisters annually) is now recognized as a robust indicator of underlying disease instability, correlating with an elevated risk of future exacerbations and increased healthcare utilization [

14,

21,

22]. This reveals a critical gap in current guidelines, which may overlook patients who, despite appearing stable by conventional criteria, remain at heightened risk of rapid disease progression [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. By incorporating SABA use as a marker of early instability, clinicians can optimize decision-making, particularly in primary care settings where advanced diagnostic tools like spirometry are often less accessible [

14,

21,

23,

24].

Building on the foundation of the

Seleida project, which demonstrated the utility of electronic health records (EHRs) in predicting poor disease control in COPD and asthma [

25], this study refines the concept of poor control by including patients with a single moderate exacerbation or moderate-to-high SABA use. By leveraging routinely available clinical data, such as rescue medication use and antibiotic prescriptions, this updated model aims to enhance the early identification of high-risk COPD patients, especially in resource-limited primary care settings.

This refined approach not only aligns with the need for proactive patient management but also offers a practical strategy to reduce exacerbations, hospitalizations, and healthcare costs. The following sections outline the methodology used to refine the predictive model, validate its performance, and assess its potential for improving COPD management in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective, multicenter study utilized anonymized electronic health records (EHRs) from the

Spanish Sistema Nacional de Salud (SNS) to develop a predictive model for identifying poorly controlled COPD patients based on readily accessible clinical variables [

25]. Data were randomly sampled from two primary care centers to ensure a representative cohort of real-world COPD cases. Building on the original

Seleida study—a prior observational, non-interventional multicenter analysis—this work refines the definition of poor disease control by including patients with a single moderate exacerbation or moderate-to-high SABA use, addressing gaps in traditional criteria [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

This analysis was derived from the original Seleida study, which obtained prior approval from the ethics committees of both participating centers. All data were anonymized in compliance with data protection regulations to ensure confidentiality.

2.2. Patient Selection and Variables Collected

Eligible patients were aged 40 to 80 years, with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD or documented COPD treatment for at least three months per year over the past two years. Exclusion criteria included active malignancies, patients in palliative care, those with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), chronic users of systemic corticosteroids, recipients of biologic therapies, and participants in clinical trials. Additionally, bedridden or severely disabled patients were excluded to minimize confounding factors affecting disease control. Only patients with complete, up-to-date clinical records and consistent follow-up during the study period were included to ensure robust predictive analyses.

Key clinical variables extracted from EHRs included demographic data (age, sex, and province of residence), anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI), and relevant comorbidities (e.g., smoking status, sleep apnea, obesity, cardiovascular diseases). COPD-specific variables encompassed daily inhalation frequency, use of rescue medications (annual SABA and short-acting muscarinic antagonist [SAMA] prescriptions), the number of exacerbations in the past year (moderate or severe), as well as emergency department visits or physician consultations for respiratory issues. Data on systemic corticosteroid use (converted to prednisone-equivalent doses) and antibiotic prescriptions for bronchitis or exacerbations were also collected, along with blood eosinophil counts. A comprehensive description of the variables collected in the

Seleida study has been previously published [

25].

2.3. Model Definition

Current COPD risk and control models, such as those proposed in the GOLD 2024 and GesEPOC 2021 frameworks, primarily rely on spirometry, symptom assessments, and exacerbation history [

1,

11]. However, these approaches may fail to identify patients at risk who experience moderate exacerbations or exhibit elevated SABA use, both of which are strongly linked to worse clinical outcomes [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Moderate exacerbations—defined as episodes requiring systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics without hospitalization—and the use of three or more SABA canisters annually are established predictors of increased exacerbation risk and suboptimal disease management [

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The core premise of our model is that a well-controlled COPD patient should not require frequent rescue medications or experience exacerbations within the past year. To address existing gaps, we developed a predictive model that redefines COPD control by incorporating moderate exacerbations and frequent SABA use as primary indicators. This model identifies patients with a single moderate exacerbation, one severe exacerbation, or frequent SABA use (≥3 canisters annually), providing a more precise tool for detecting patients who may be overlooked by traditional criteria.

In our model, control is defined by the probability of future exacerbations, with higher probabilities indicating poorer control. To enhance its practicality in primary care settings, we intentionally excluded spirometry data, focusing instead on easily accessible clinical markers. This decision broadens its applicability, especially in settings where spirometry is underutilized or unavailable [

23]. The refined approach aims to support proactive management, reduce exacerbations, slow disease progression, and alleviate healthcare costs.

By integrating previously overlooked variables, the model enhances early identification of high-risk patients, enabling timely interventions. Its focus on moderate exacerbations and frequent SABA use aligns with current evidence, underscoring their predictive value for adverse outcomes [

14,

16,

26]. This adaptability to real-world primary care settings increases the model’s potential to improve COPD management through early interventions, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and reducing the overall healthcare burden [

27].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

After excluding 4 patients from the initial cohort of 110 to avoid bias (see section 2.6), all statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.4.2) [

28]. This platform was chosen for its robust capabilities in handling complex predictive models essential for identifying high-risk COPD patients [

28]. A significance level of 0.05 was set, and variables with more than 50% missing data were excluded to ensure model stability [

29]. The analysis was divided into two phases to enhance predictive accuracy.

2.4.1. Phase 1

Associations between clinical variables and disease control were assessed using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables [

30]. To control for multiple comparisons and reduce the risk of Type I errors, the Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied [

27]. This phase aimed to identify clinically relevant variables, ensuring that only the most significant predictors were carried forward to the subsequent model for targeted interventions.

2.4.2. Phase 2

Variables identified as significant in Phase 1 (adjusted p-value < 0.05) were included in a logistic regression model using the

glmnet package [

31]. To prevent overfitting, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regularization was applied, optimizing model performance by selecting relevant variables while shrinking coefficients [

31]. LASSO was preferred over Ridge regression, which only shrinks coefficients, as it also performs variable selection, resulting in a more parsimonious and interpretable model. Although Elastic Net combines aspects of both methods, its added complexity was deemed unnecessary given our dataset [

31].

The model was further refined using a backward stepwise approach guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [

27]. Predictive performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy, employing an 80/20 training-validation split [

32]. Bootstrapping with 1,000 iterations was applied to confirm the stability of the coefficients.

2.5. Definition of Minimal Sample Size for Model Validation

Sample size calculations were grounded on data from the AVOIDEX study, which reported that 48.2% of patients were non-exacerbators [

33]. This approach ensured that the study had sufficient power to detect clinically relevant predictors.

2.5.1. Determination of Minimum Events in the Training Set

Based on the “10 events per predictor variable” rule, the training set (80% of the dataset) required at least 30 events to ensure stable estimates [

27]. With three predictor variables, this threshold was comfortably met, allowing for reliable identification of patients at risk.

2.5.2. Calculation of Total Sample Size

To validate model performance, we applied the formula 0.2 × n × 0.482 ≥ 10, which yielded a required sample size of at least 104 patients [

27]. This calculation was essential to ensure that the model’s findings could be generalized to clinical practice, where timely identification of high-risk patients is crucial for early intervention.

2.5.3. Verification of Events in the Training Set

The training set contained approximately 40 events (0.8 × 104 × 0.482 ≈ 40), exceeding the minimum requirement of 30 events, thereby confirming model stability. The total sample size of 106 patients provided robust internal validity. Although McNemar’s test indicated no significant differences in error rates compared to reference classifiers, suggesting strong predictive reliability, further studies with larger cohorts could enhance the model’s precision [

34,

35].

2.6. Limitations

This model focuses on accessible clinical variables, but several limitations must be acknowledged. The exclusion of spirometry data, while enhancing practicality in primary care, may reduce precision in complex cases where lung function assessments are crucial [

36,

37]. Although spirometry remains the gold standard for COPD diagnosis, its underutilization in primary care is often due to resource and time constraints [

24,

38]. This underscores the need for pragmatic tools that can function effectively without spirometry[

37].

The retrospective design may introduce biases, such as incomplete or inconsistent data. To address this, variables with more than 50% missing data were excluded [

29]. Additionally, four patients without documented COPD treatment in the past year were removed to prevent confounding from potential data entry errors, overdiagnosis, untreated mild cases, poor adherence, unrecorded private sector care, or failure to deregister deceased patients.

While the model relies on rescue medication use and exacerbation history to guide interventions, further validation in diverse populations is essential to confirm its generalizability. Expanding cohorts to include a broader range of demographics would enhance its applicability. Future iterations could incorporate spirometry or patient-reported outcomes to increase precision, especially in more complex cases [

36].

Despite these limitations, the model effectively identifies key predictors of poor COPD control using readily available data, addressing gaps in current diagnostic criteria [

25]. This highlights its potential for early detection and proactive management in primary care, with a focus on prioritizing interventions for poorly controlled patients.

3. Results

Our findings underscore the critical need for early, proactive interventions in COPD management, particularly following a patient’s first exacerbation. These episodes not only accelerate disease progression but also increase healthcare utilization and reduce quality of life [

11,

20]. Early identification of poorly controlled patients is essential, as they face a significantly higher risk of rapid decline, imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems [

26].

The study demonstrates that promptly identifying patients after even a single moderate exacerbation allows for timely interventions to prevent further deterioration [

20,

21]. By integrating exacerbation history with key biomarkers, such as eosinophil levels, we enhanced the precision of personalized treatment strategies [

36]. This approach aligns with evidence supporting individualized interventions, optimizing patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs.

The following results highlight the need for a predictive model to prioritize patients with poor control, enabling targeted interventions that can mitigate disease progression and alleviate strain on healthcare resources.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

From the initial cohort of 110 patients, 4 from the Valencia cohort were excluded due to a lack of prescribed maintenance or rescue medication in the previous year. These patients, initially classified as having good COPD control, were excluded to prevent potential bias, as their apparent control status likely reflected incomplete treatment records rather than their actual clinical condition (see section 2.3) [

29]. This adjustment resulted in a final cohort of 106 patients, with a mean age of 68.8 ± 8.2 years, predominantly male (72.6%).

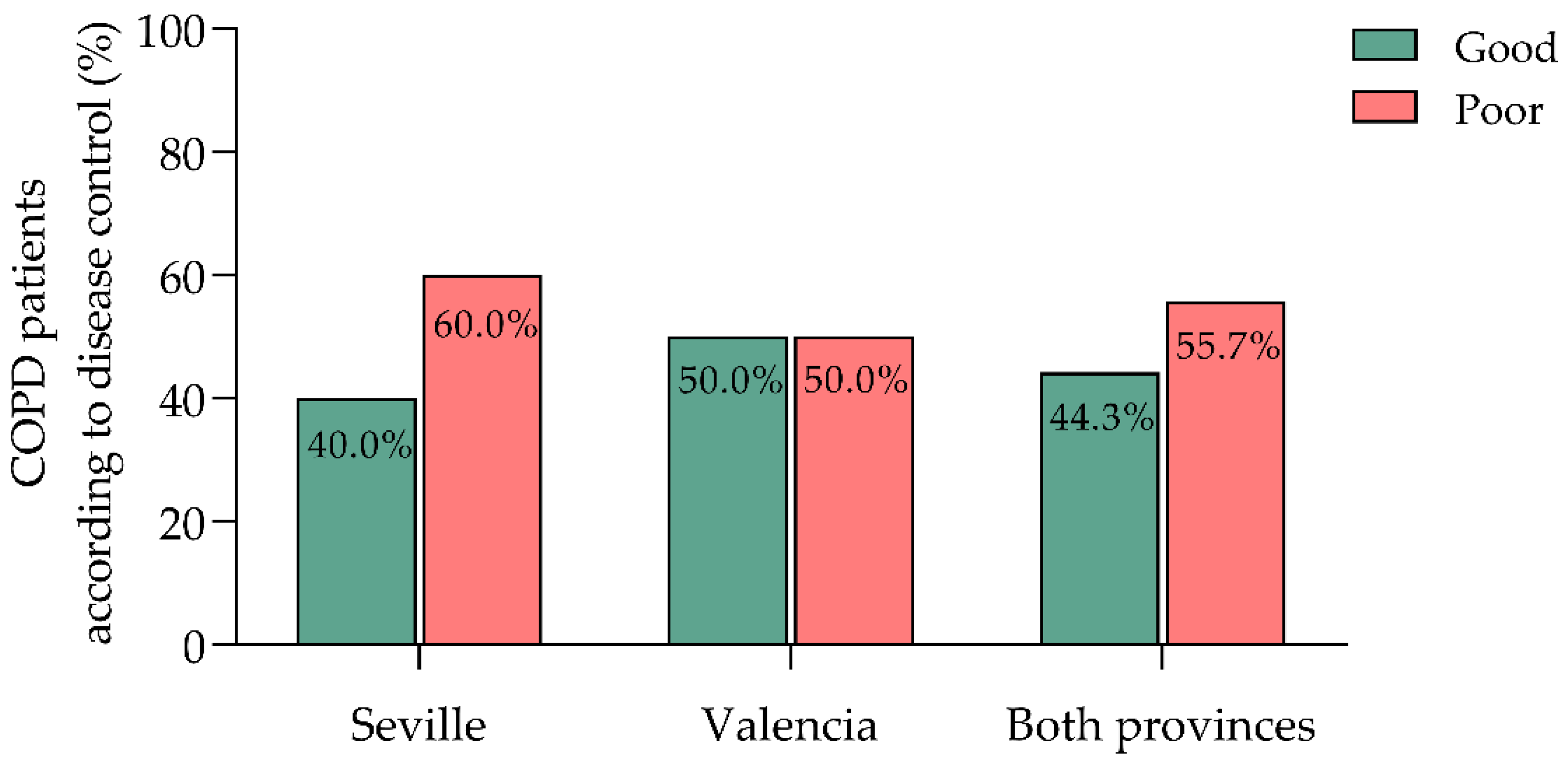

Using our refined criteria for poor COPD control—defined as at least one moderate exacerbation, one severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization, or annual use of three or more SABA canisters—55.7% of patients were classified as poorly controlled, while 44.3% were well-controlled (

Figure 1). These rates slightly exceed those reported in the AVOIDEX study (51.8% poorly controlled, 48.2% well-controlled) [

33], supporting the external validity of our findings. The higher proportion of poorly controlled patients in our cohort ensured a sufficient number of events to validate the model, meeting the “10 events per predictor variable” threshold [

27].

Patients were distributed across two healthcare centers in Seville and Valencia. The Seville center had a higher proportion of poorly controlled patients (60.0%) compared to Valencia (50.0%), while Valencia had a greater proportion of well-controlled cases (50.0% vs. 40.0% in Seville) (

Figure 1). However, this difference was not statistically significant (χ² = 1.055, p = 0.304), suggesting minimal regional variations.

Aside from the control criteria, baseline characteristics were largely similar between the two groups. These findings underscore the need for more targeted strategies to identify patients at risk of poor control, particularly in regions like Seville, where a higher burden of poorly controlled cases was observed.

3.2. Exacerbations and Healthcare Utilization

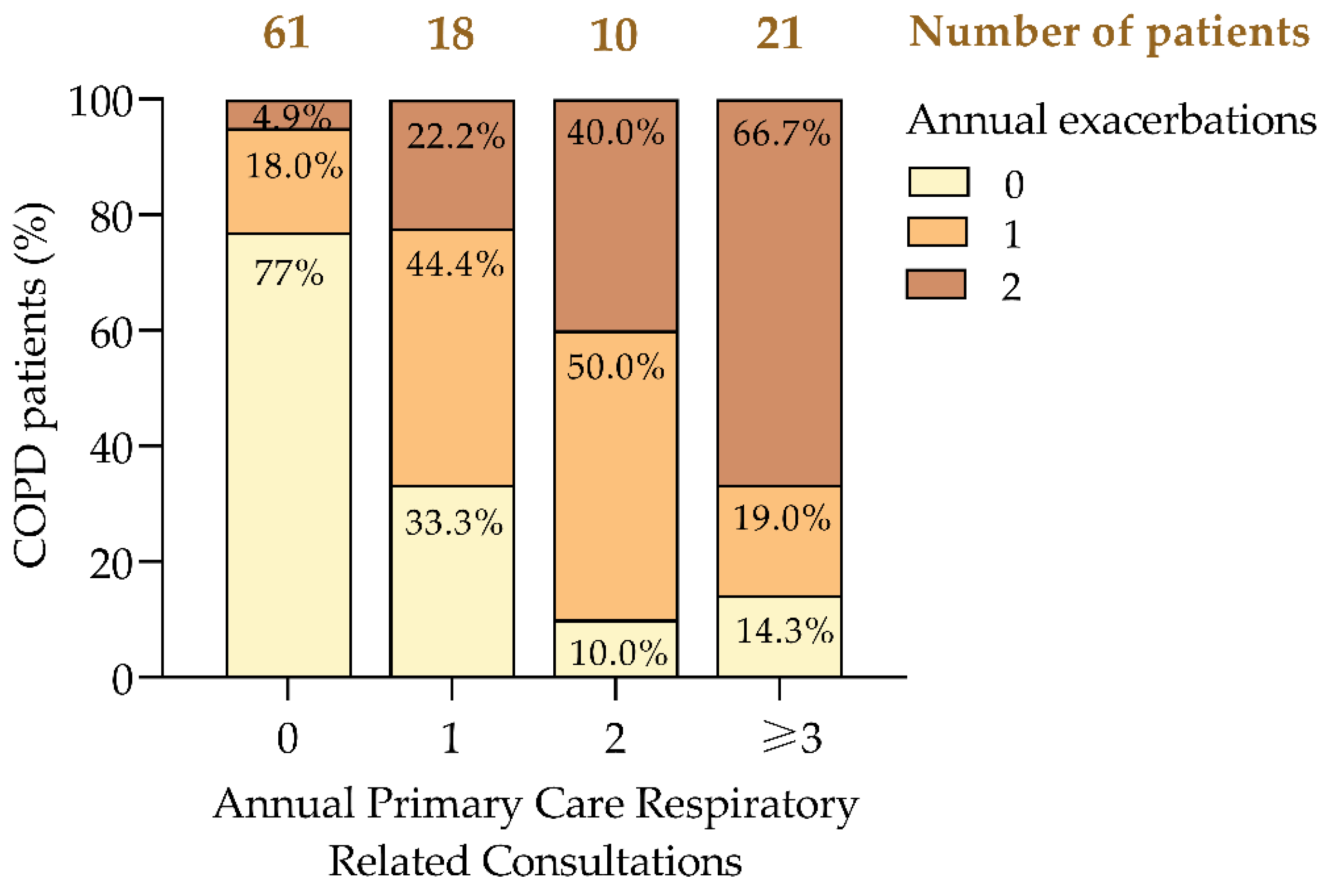

The frequency of exacerbations was strongly associated with increased healthcare utilization, consistent with previous studies [

8,

39]. A paired t-test confirmed a significant correlation between annual exacerbations and respiratory consultations (p = 0.010), indicating that patients with frequent exacerbations consumed more healthcare resources.

Our analysis revealed a clear trend: as the frequency of consultations increased, so did the proportion of patients experiencing multiple exacerbations (

Figure 2). Notably, 66.7% of patients with three or more consultations had ≥2 exacerbations, compared to only 4.9% among those with no consultations (

Figure 2). Conversely, 77.0% of patients who did not require consultations had no exacerbations, highlighting the link between effective COPD control and reduced healthcare demands.

The data also showed a progressive increase in the proportion of patients with ≥2 exacerbations as consultation frequency rose, from 4.9% in those without consultations to 66.7% in those with three or more consultations. Additionally, 44.4% of patients with one consultation and 50.0% of those with two consultations experienced a single exacerbation, suggesting that early interventions in these groups could prevent further disease progression.

A strong positive correlation (r = 0.617, p < 0.001) confirmed that patients with more exacerbations had higher healthcare demands. These findings align with prior research demonstrating a high prevalence of exacerbations among poorly controlled patients [

20,

26,

40], underscoring the need for targeted interventions to reduce both exacerbations and the associated healthcare burden.

3.3. Medication Data on COPD Exacerbations

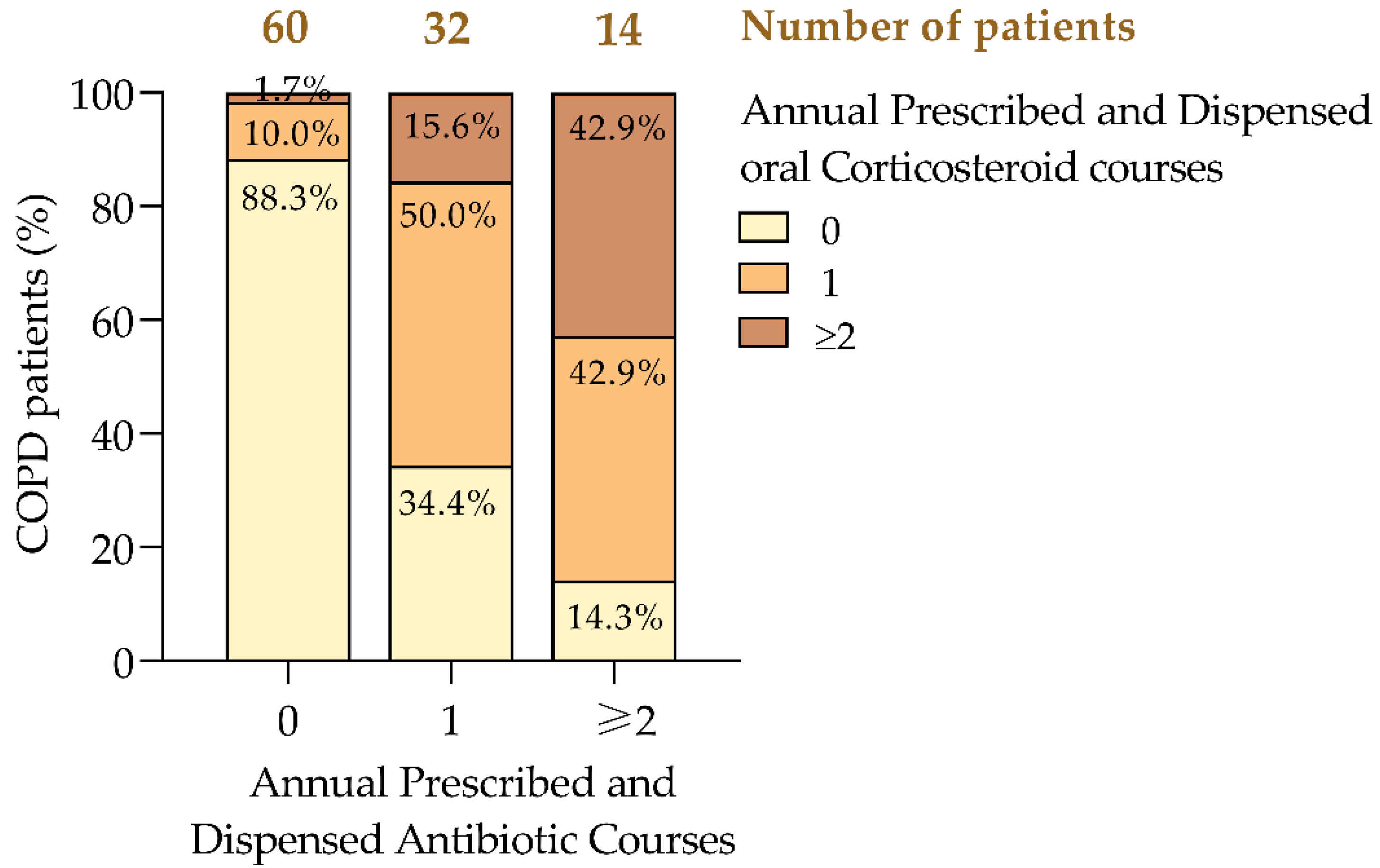

COPD exacerbations were primarily managed with antibiotics and oral corticosteroids [

1,

11]. Among patients who did not require antibiotics, 88.3% also did not need corticosteroids, while 10% required one course and 1.7% needed two or more. In contrast, among those prescribed a single antibiotic course, 50% also required one corticosteroid course, and 15.6% needed two or more (

Figure 3). Patients requiring two or more antibiotic courses were more likely to need corticosteroids, with 42.9% requiring one course and another 42.9% needing two or more. This pattern suggests that frequent antibiotic use correlates with more severe exacerbations that also necessitate corticosteroid treatment [

6,

8].

Although a paired t-test did not reveal a significant difference between antibiotic and corticosteroid use (p = 0.207), Pearson’s correlation (r = 0.623, p < 0.001) indicated a strong positive association, suggesting that higher antibiotic use predicts a greater need for corticosteroids. Bivariate linear regression further supported this, showing that each additional antibiotic course was associated with a 0.603-unit increase in corticosteroid use (p < 0.001).

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.613, Hedges’ g = 0.617) demonstrated that patients with poorly controlled COPD were significantly more likely to require multiple courses of antibiotics and corticosteroids, along with increased SABA use [

14,

15,

41]. These findings underscore the need for personalized management strategies to reduce exacerbations and optimize treatment, supporting evidence for tailored interventions aimed at improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare costs [

26,

36].

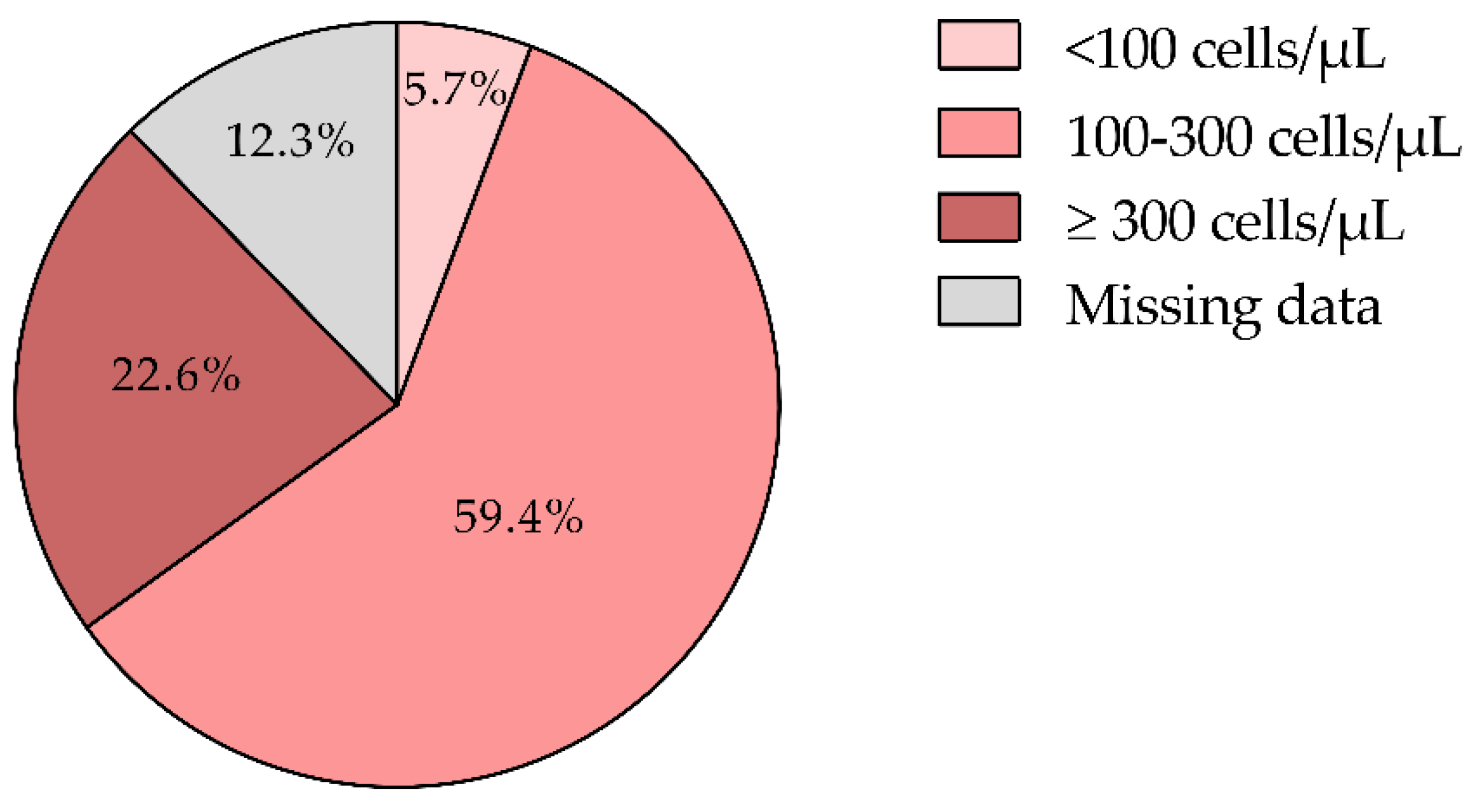

3.4. Eosinophil Levels and Disease Phenotypes

Eosinophil counts were available for 87.7% of patients, with a mean of 230.9 ± 137.8 cells/µL. The majority (59.4%) had levels between 100 and 300 cells/µL, while 22.6% had counts ≥300 cells/µL. According to GOLD and GesEPOC guidelines [

1,

11], eosinophil levels ≥300 cells/µL strongly support the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) due to the associated inflammatory burden. For patients with levels between 100 and 300 cells/µL, ICS may also be beneficial, particularly for those with at least one moderate exacerbation in the past year [

1,

14,

20,

42].

Aligned with the GOLD 2024 guidelines, ICS are recommended for patients with a history of hospitalization due to COPD exacerbations, two or more moderate exacerbations annually, or eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/µL. Conversely, ICS should be avoided in patients with counts <100 cells/µL or those with a history of mycobacterial infections or recurrent pneumonia [

43]. In our cohort, only 5.7% had eosinophil counts <100 cells/µL (

Figure 4), suggesting that ICS therapy may not be necessary for this subgroup (

Figure 4).

Overall, 82.0% of patients met the eosinophilic profile (≥100 cells/µL) (

Figure 4) recommended for ICS treatment, highlighting the role of eosinophil levels in guiding COPD management. Tailoring treatment based on eosinophil counts enables more targeted interventions, potentially reducing exacerbations and improving patient outcomes [

14,

20,

42,

44]. However, the absence of eosinophil data in 12.3% of patients limits the ability to fully personalize treatment, underscoring the need for consistent monitoring to optimize therapeutic strategies.

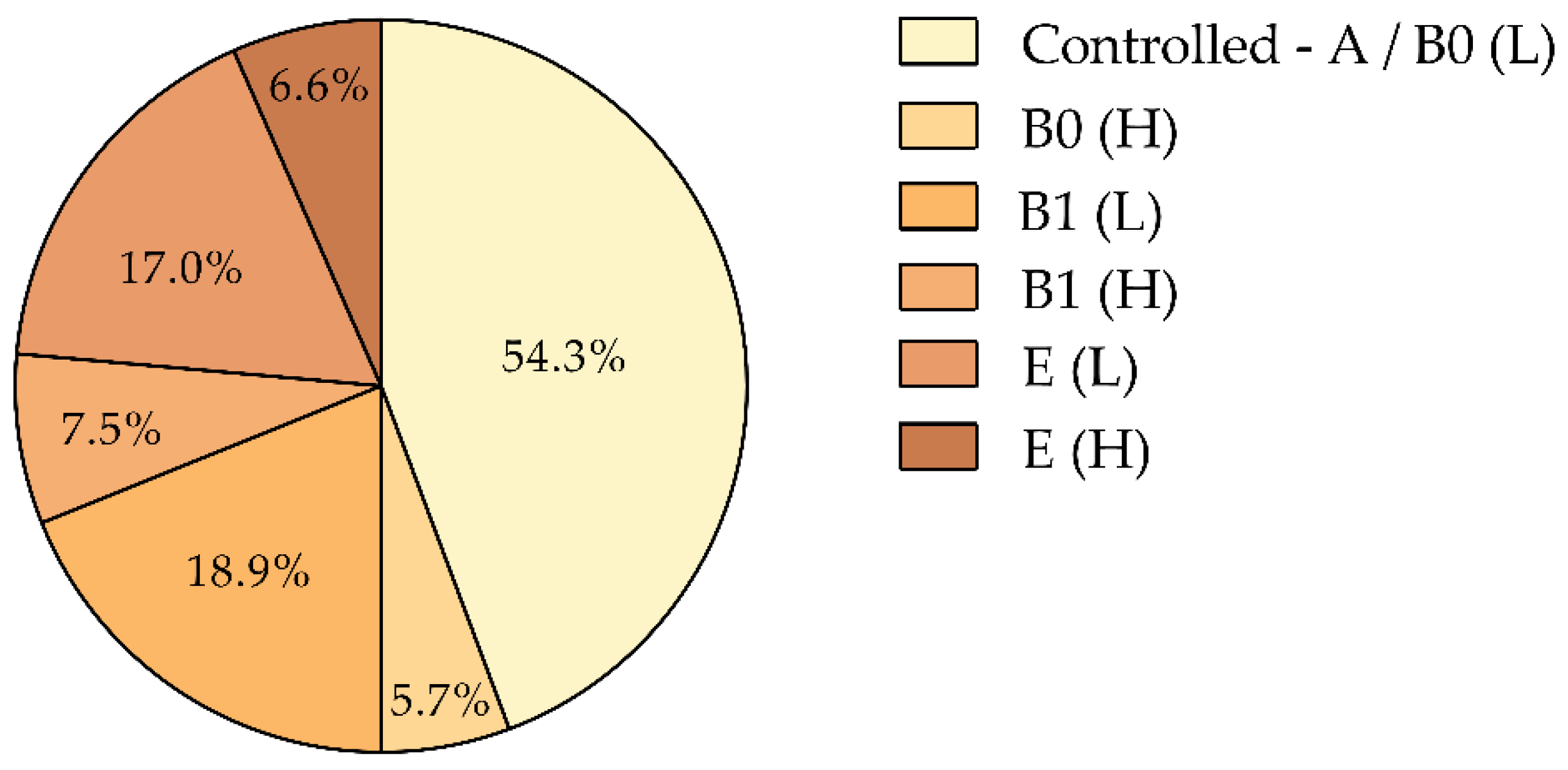

3.5. COPD Phenotypes Based on Exacerbation Frequency and Annual SABA Use

Patients were classified into six distinct phenotypic subgroups according to the GOLD 2024 ABE classification [

1] and their annual SABA consumption (

Figure 5):

Controlled (A/B0 [L]): No exacerbations and low SABA use (44.3%).

B0 [H]: No exacerbations but high SABA use (5.7%).

B1 [L]: One moderate exacerbation with low SABA use (18.9%).

B1 [H]: One moderate exacerbation with high SABA use (7.5%).

E [L]: Two or more exacerbations with low SABA use (17.0%).

E [H]: Two or more exacerbations with high SABA use (6.6%).

This classification system stratifies patients based on exacerbation frequency and SABA consumption, where the first letter indicates the number of exacerbations and the letter in brackets denotes SABA use (‘L’ for low, <3 canisters/year; ‘H’ for high, ≥3 canisters/year). Elevated SABA use, particularly among patients with frequent exacerbations, correlates with poor disease control and suggests a need for more intensive management [

14,

15,

21].

Notably, high SABA use in patients without exacerbations (B0 [H]) likely reflects an increased symptom burden [

14,

36], indicating that these patients may benefit from a reevaluation of their treatment regimen. This stratification aligns with the GOLD ABE framework, providing a structured approach to tailor interventions based on individual patient risk profiles. By integrating both exacerbation history and SABA use, this classification system supports a personalized approach to COPD management, with the goal of optimizing outcomes and reducing exacerbation rates [

15,

20].

3.6. Determination of Clinical Variables for Predict Poor Control of COPD Disease

We developed a predictive model for poor COPD control using robust statistical techniques to ensure stability and accuracy [

35,

38]. Four untreated patients with no recorded daily inhalations were excluded to prevent potential confounding from overdiagnosis, mild disease, or incomplete records [

31]. This exclusion ensured the model focused solely on actively treated patients, thereby enhancing data reliability.

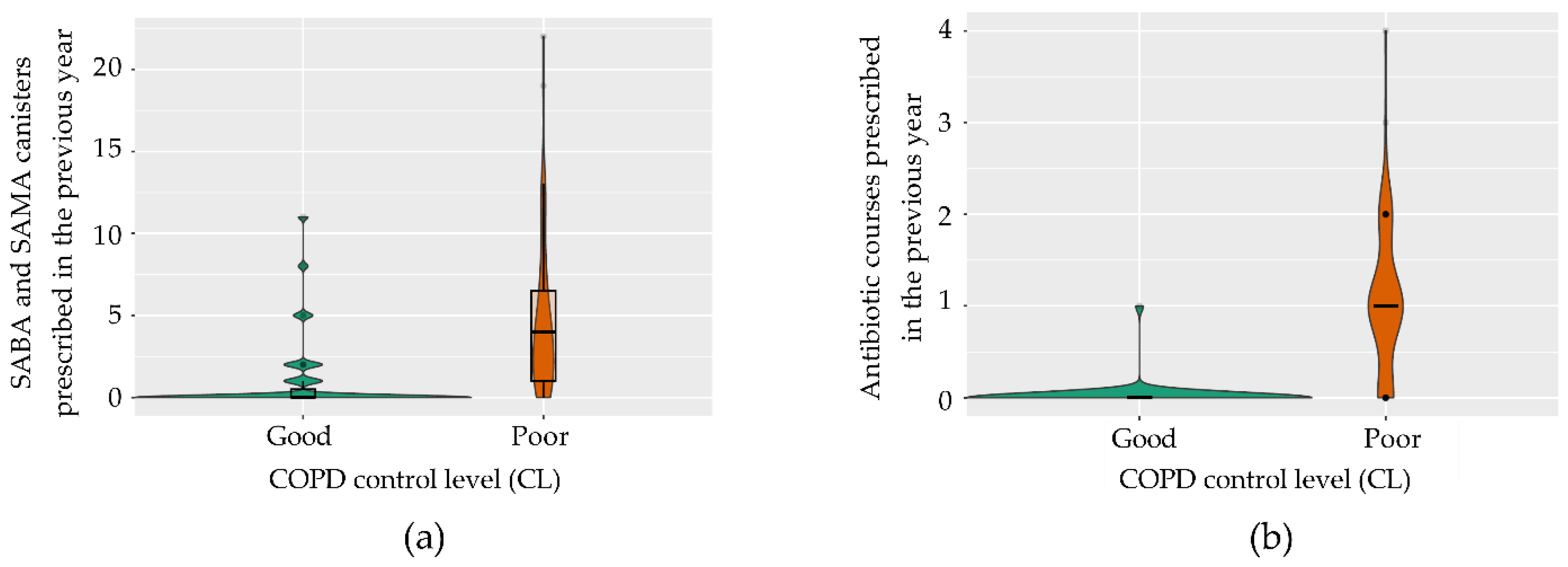

3.6.1. Statistical Analysis and Model Development

Univariate analysis identified significant associations between poor control and several variables, including SABA/SAMA use (p < 0.001), respiratory consultations (p = 0.010), annual corticosteroid courses (p < 0.001), prednisone doses (p = 0.004), and antibiotic courses (p < 0.001). Age showed a weaker association (p = 0.049). To ensure robustness, we applied the Benjamini-Hochberg correction and addressed multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [

27].

Subsequently, we developed a binary logistic regression model using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for variable selection [

31]. The analysis identified two primary predictors: the annual count of SABA/SAMA inhalers dispensed and antibiotic courses prescribed for exacerbations (

Figure 6 and

Table 1). The model demonstrated strong reliability, with a residual deviance of 44.33 and an AIC of 50.33.

Although the transformed variable ‘daily inhalation frequency’ (categorized as 1 vs. >1 inhalation/day) indicated that patients using only one inhalation per day had significantly better control than those requiring multiple doses (p = 0.018), it was excluded to prevent overfitting due to high bias and increased standard error.

By focusing on key variables—specifically, rescue medication use and antibiotic prescriptions—the model remains both clinically relevant and easy to interpret for primary care providers. Utilizing data readily available from electronic health records (EHRs) enables clinicians to promptly identify at-risk patients, facilitating timely, data-driven interventions without the need for complex diagnostics.

3.6.2. Key Findings and Model Optimization

Both predictors—SABA/SAMA inhaler use and antibiotic courses—were statistically significant and clinically relevant markers of disease instability (

Table 1) [

45,

46]. To enhance the model, we applied LASSO regularization, which improved interpretability by selecting the most relevant variables [

31]. Bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations) confirmed the stability of the model’s coefficients (

Table 2) [

27]. The positive coefficients for both predictors indicate that increased medication use correlates with a higher likelihood of poor control, underscoring the need for targeted management strategies.

3.6.3. Model Performance

The final model achieved an accuracy of 90.91% [95% CI: 70.84–98.88], with a sensitivity of 92.86%, specificity of 87.50%, PPV of 92.86%, and NPV of 87.50%. The kappa coefficient of 80.36% post-LASSO confirmed strong predictive reliability. The model demonstrated substantial discriminative ability, with an AUC-ROC of 0.978. Additionally, a high positive likelihood ratio (LR+ of 7.43) indicated strong predictive power for identifying poor control, while a low negative likelihood ratio (LR- of 0.082) minimized the risk of misclassifying patients with good control.

3.6.4. Predictive Equation

Following LASSO regularization, the final predictive equation is:

[SABA+SAMA]: total number of SABA and SAMA canister prescribed and dispensed in the previous year.

[Antibiotic_courses]: number of antibiotic courses prescribed and dispensed in the previous year due to bronchitis or COPD exacerbations.

The model classifies patients based on their predicted probability (y) of poor COPD control, using a threshold of 0.50. Patients with probabilities above this threshold are classified as poorly controlled, while those below it are deemed well-controlled. Further adjustments to the cutoff point using ROC curve analysis and Youden’s J index did not result in significant improvements, confirming the model’s optimal performance.

4. Discussion

This study introduces a clinically practical model for identifying poorly controlled COPD patients in primary care, demonstrating exceptional predictive performance with an AUC-ROC of 0.978, along with high sensitivity (92.86%) and specificity (87.50%). By focusing on straightforward yet robust markers, such as SABA use and antibiotic prescriptions [

25], the model provides a powerful tool for early detection, particularly in settings where access to advanced diagnosis is limited [

47].

A key insight from our analysis reveals that many patients, despite appearing stable under traditional criteria, may exhibit early signs of poor control when assessed through medication use patterns. For instance, a COPD patient with only one moderate exacerbation in the past year but frequent SABA use (≥3 canisters annually) would typically be classified as stable according to current guidelines. However, our model identifies this patient as high-risk, prompting clinicians to optimize maintenance therapy or initiate preventive interventions. This proactive approach could significantly reduce exacerbations and hospitalizations, bridging critical gaps in conventional diagnostic practices while enabling more personalized management strategies.

Our findings also underscore that patients on a maintenance regimen of a single daily inhalation exhibit significantly better disease control compared to those requiring multiple inhalations (p = 0.018) [

19]. This observation suggests that streamlined treatment strategies align with the shift towards personalized, proactive COPD management and may enhance patient adherence. However, in order to prevent overfitting or loss of consistency, we have decide to exclude this variable from the predictive model because it remains uncertain whether the superior control observed in these patients is due to an inherently lower symptomatic burden or if the regimen’s simplicity itself drives better outcomes [

1,

21,

48,

49]. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between inhalation frequency and clinical stability.

Additionally, the model’s reliance on medication patterns, particularly rescue medication use and annual antibiotic prescriptions, extends beyond prediction by offering a pathway for preclinical phenotyping. This approach could facilitate the early identification of high-risk patients, enabling targeted interventions tailored to specific COPD phenotypes [

50,

51]. By leveraging readily available electronic health records (EHRs), the model can seamlessly integrate into various healthcare settings, enhancing its practicality and scalability [

25].

Implementing this model could yield substantial cost savings by reducing the frequency of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits [

52]. Early identification of high-risk patients enables more efficient allocation of resources, which is crucial for sustainable COPD management, particularly in resource-constrained settings [

53]. For example, preventing a single hospitalization can result in significant cost savings, thereby alleviating pressure on healthcare systems.

While excluding spirometry data enhances the model’s feasibility in primary care, it may limit precision in complex cases [

54]. Future iterations could incorporate real-time patient data and leverage machine learning algorithms to refine predictions, enabling continuous monitoring and adaptive interventions [

36,

55,

56,

57]. Moreover, integrating patient-reported outcomes could provide a more comprehensive assessment of disease control, further enhancing the model’s utility.

To confirm its generalizability, expanding the validation cohort to include more diverse populations is essential. Broader implementation across different healthcare contexts will help establish its utility, driving a more personalized approach to COPD management. As healthcare systems face increasing pressures, this model offers a scalable solution to shift from reactive to proactive care, ultimately optimizing patient outcomes, reducing costs, and ensuring a more sustainable approach to COPD management.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a practical predictive model for early identification of poorly controlled COPD patients in primary care. By focusing on simple yet robust markers—specifically, SABA/SAMA use and antibiotic prescriptions—the model achieves high sensitivity (92.86%) and specificity (87.50%), allowing for proactive interventions that reduce disease progression and alleviate healthcare burdens [

17,

25,

30].

By expanding the criteria to include patients with a single moderate exacerbation or frequent SABA use, the model addresses gaps in current diagnostic approaches and aligns with the shift towards personalized medicine [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. It leverages routinely collected EHR data, facilitating seamless integration into diverse healthcare settings and supporting evidence-based decision-making.

Further validation in larger, diverse populations is needed to confirm its generalizability. Future iterations could incorporate machine learning and real-time data to enhance predictive capabilities and enable continuous patient monitoring [

36,

57]. Additionally, integrating patient-reported outcomes could provide a more comprehensive view of disease control [

58,

59].

Ultimately, this model can transform COPD management by shifting from reactive to proactive care, enabling earlier, targeted interventions that optimize resource use and improve patient outcomes. As healthcare systems face growing pressures, such tools offer scalable solutions to enhance patient care and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology, and draft preparation through their scientific and medical expertise. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project received support from EP Health Marketing SL, a scientific content publisher, which declares that it did not receive any public funding or subsidies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset of Valencia (protocol code CEIm 132.22, approval date 6 March 2023). The project was registered in the Portal de Ética de la Investigación Biomédica de Andalucía through the Sistema de Información de los Comités de Ética de la Investigación (protocol code 1140-N-23, approval date 12 September 2023). The SEMERGEN research department gave its endorsement to the project (2023-00035, approval date 6 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study, which involved exclusively extracting anonymized data from patients’ Electronic Health Records (EHR). No diagnostic tests were performed, no clinical interventions were conducted, and no modifications to patient management were made. Furthermore, no treatment recommendations were provided based on the extracted data. The study’s sole objective was to extract specific variables to develop a predictive model, with no implications for patient privacy or confidentiality. This waiver aligns with the ethical guidelines of the Research Ethics Committees consulted, which determined that the study posed minimal risk to patients and that obtaining individual informed consent was unnecessary.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by EP Health Marketing, S.L., Spain and bioinformatic analysis by Lina Marcela Gallego-Paez. The authors thank Eva Trillo Calvo, family physician and current director of primary care of Sector II of Zaragoza at the Servicio Aragonés de Salud, for her support and collaboration at the beginning of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Maya Viejo, J.D. has received research grants from AMGEN, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini and Novartis. He is a member of the SEMERGEN and SEMG and he belongs to the SEMERGEN respiratory work group. Navarro Ros, F.M. has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Esteve, Ferrer, GSK, Kern Parma, Lundbeck, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi and Viatris. He is a member of the SEMERGEN and he belongs to the SEMERGEN respiratory work group.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstrucitve Lung Disease 2024, 1–218.

- Boers, E.; Barrett, M.; Su, J.G.; Benjafield, A. V; Sinha, S.; Kaye, L.; Zar, H.J.; Vuong, V.; Tellez, D.; Gondalia, R.; et al. Global Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Through 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, E2346598. [CrossRef]

- Buttery, S.A.R.A.C.; Zysman, M.A.; Vikjord, S.I.A.A.; Hopkinson, N.I.S.; Jenkins, C.H.; Vanfleteren, L.O.E.G.W. Contemporary Perspectives in COPD : Patient Burden , the Role of Gender and Trajectories of Multimorbidity. Respirology 2021, 26, 419–441. [CrossRef]

- Sandelowsky, H.; Weinreich, U.M.; Aarli, B.B.; Sundh, J.; Høines, K.; Stratelis, G.; Løkke, A.; Janson, C.; Jensen, C.; Larsson, K. 1 COPD – Do the Right Thing. BMC Fam Pr. 2021, 22, 244.

- Stöber, A.; Lutter, J.I.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Kirsch, F.; Schramm, A.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Leidl, R. Impact of Lung Function and Exacerbations on Health-Related Quality of Life in COPD Patients Within One Year: Real-World Analysis Based on Claims Data. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 2637–2651. [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, N.; Huang, Y.C. Acute Exacerbations and Respiratory Failure in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008, 5, 530–535. [CrossRef]

- Kim, V.; Aaron, S.D. What Is a COPD Exacerbation ? Current Definitions , Pitfalls , Challenges and Opportunities for Improvement. Eur Respir J 2018, 52, 1801261. [CrossRef]

- Anzueto, A. Impact of Exacerbations on COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2010, 19, 113–118. [CrossRef]

- Rothnie, K.J.; Müllerová, H.; Quint, J.K. Natural History of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations in a General Practice – Based Population with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 198, 464–471. [CrossRef]

- Viniol, C.; Vogelmeier, C.F. Exacerbations of COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 170103. [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles, M.; Calle, M.; Molina, J.; Almagro, P.; Gómez, J.T.; Trigueros, J.A.; Cosío, B.G.; Casanova, C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Riesco, J.A.; et al. Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) 2021: Updated Pharmacological Treatment of Stable COPD. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 69–81. [CrossRef]

- Bollmeier, S.G.; Hartmann, A.P. Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease : A Review Focusing on Exacerbations. Am J Heal. Syst Pharm 2020, 77, 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Early Detection and Prediction of Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chinese Med. J. Pulm. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 1, 102–107. [CrossRef]

- Janson, C.; Wiklund, F.; Telg, G.; Stratelis, G.; Sandelowsky, H. High Use of Short-Acting β 2 -Agonists in COPD Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Exacerbations and Mortality. ERJ Open Res 2023, 9, 00722–02022. [CrossRef]

- Gondalia, R.; Bender, B.G.; Theye, B.; Stempel, D.A. Higher Short-Acting Beta-Agonist Use Is Associated with Greater COPD Burden. Respir. Med. 2019, 158, 110–113. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, H.; Rubino, A.; Müllerová, H.; Morris, T.; Varghese, P.; Xu, Y.; Nigris, E. De; Quint, J.K. Frequency and Severity of Exacerbations of COPD Associated with Future Risk of Exacerbations and Mortality : A UK Routine Health Care Data Study. Int J Chron Obs. Pulmon Dis 2022, 17, 427–437.

- Løkke, A.; Hilberg, O.; Lange, P.; Licht, S.D.F.; Lykkegaard, J. Disease Trajectories and Impact of One Moderate Exacerbation in Gold B COPD Patients. Int J Chron Obs. Pulmon Dis 2022, 17, 569–578.

- Løkke, A.; Hilberg, O.; Lange, P.; Ibsen, R.; Bakke, P.; Ørts, L. The Impact on Future Risk of One Moderate COPD Exacerbation in GOLD A Patients – a Cohort Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 4520. [CrossRef]

- Marott, J.L.; Çolak, Y.; Ingebrigtsen, T.S.; Vestbo, J.; Nordestgaard, B.; Lange, P. Exacerbation History , Severity of Dyspnoea and Maintenance Treatment Predicts Risk of Future Exacerbations in Patients with COPD in the General Population. Respir Med 2022, 192, 106725.

- Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tong, S.; Dong, J. Moderate and Severe Exacerbations Have a Significant Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life, Utility, and Lung Function in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Maltais, F.; Naya, I.P.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Boucot, I.H.; Jones, P.W.; Bjermer, L.; Tombs, L.; Compton, C.; Lipson, D.A.; Kerwin, E.M. Salbutamol Use in Relation to Maintenance Bronchodilator Efficacy in COPD: A Prospective Subgroup Analysis of the EMAX Trial. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 280. [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, J.M.; Haddon, J.M.; Bradly-Kennedy, C.; Kuramoto, L.; Ford, G.T. Resource Use Study in COPD (RUSIC): A Prospective Study to Quantify the Effects of COPD Exacerbations on Health Care Resource Use among COPD Patients. Can. Respir. J. 2007, 14, 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Derom, E.; van Weel, C.; Liistro, G.; Buffels, J.; Schermer, T.; Lammers, E.; Wouters, E.; Decramer, M. Primary Care Spirometry*. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 31, 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Chapron, A.; Lemée, T.; Pau, G.; Jouneau, S.; Kerbrat, S.; Balusson, F.; Oger, E. Spirometry Practice by French General Practitioners between 2010 and 2018 in Adults Aged 40 to 75 Years. NPJ Prim. care Respir. Med. 2023, 33, 33. [CrossRef]

- Navarro Ros, F.; Maya Viejo, J.D. Preclinical Evaluation of Electronic Health Records ( EHRs ) to Predict Poor Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases in Primary Care : A Novel Approach to Focus Our Efforts. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5609.

- Hurst, J.R.; Han, M.K.; Singh, B.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, G.; Nigris, E. De Prognostic Risk Factors for Moderate - to - Severe Exacerbations in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease : A Systematic Literature Review. Respir Res 2022, 23, 213.

- Steyerberg, E.W. Clinical Prediction Models; Springer Science & Business Medi, 2019;

- Computing, R.F. for S. The R Project for Statistical Computing Available online: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Schneeweiss, S.; Avorn, J. A Review of Uses of Health Care Utilization Databases for Epidemiologic Research on Therapeutics. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 323–337. [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, P. An Introduction to Statistics: Choosing the Correct Statistical Test. Indian J. Crit. care Med. peer-reviewed, Off. Publ. Indian Soc. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, S184–S186. [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1996, 58, 267–288.

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The Advantages of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) over F1 Score and Accuracy in Binary Classification Evaluation. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 6. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Izquierdo, J.L.; Juárez Campo, M.; Sicras-Mainar, A.; Nuevo, J. Impact of COPD Exacerbations and Burden of Disease in Spain: AVOIDEX Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 1103–1114. [CrossRef]

- Gönen, M. Sample Size and Power for McNemar’s Test with Clustered Data. Stat. Med. 2004, 23, 2283–2294. [CrossRef]

- Lachenbruch, P.A. On the Sample Size for Studies Based upon McNemar’s Test. Stat. Med. 1992, 11, 1521–1525. [CrossRef]

- Franssen, F.M.E.; Alter, P.; Bar, N.; Benedikter, B.J.; Iurato, S.; Maier, D.; Maxheim, M.; Roessler, F.K.; Spruit, M.A.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; et al. Personalized Medicine for Patients with COPD: Where Are We? Int. J. COPD 2019, 14, 1465–1484. [CrossRef]

- López-Campos, J.L.; Hartl, S.; Pozo-Rodriguez, F.; Roberts, C.M. European COPD Audit: Design, Organisation of Work and Methodology. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 270–276. [CrossRef]

- Perret, J.; Yip, S.W.S.; Idrose, N.S.; Hancock, K.; Abramson, M.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Walters, E.H.; Waidyatillake, N. Undiagnosed and “overdiagnosed” COPD Using Postbronchodilator Spirometry in Primary Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001478. [CrossRef]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Seemungal, T.A.R. COPD Exacerbations: Defining Their Cause and Prevention. Lancet (London, England) 2007, 370, 786–796. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, G.C.; Wedzicha, J.A. COPD Exacerbations .1: Epidemiology. Thorax 2006, 61, 164–168. [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, U.S.; Aboussouan, L.S. Treating and Preventing Acute Exacerbations of COPD. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2016, 83, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- David, B.; Bafadhel, M.; Koenderman, L.; De Soyza, A. Eosinophilic Inflammation in COPD: From an Inflammatory Marker to a Treatable Trait. Thorax 2021, 76, 188–195. [CrossRef]

- Archontakis Barakakis, P.; Tran, T.; You, J.Y.; Hernandez Romero, G.J.; Gidwani, V.; Martinez, F.J.; Fortis, S. High versus Medium Dose of Inhaled Corticosteroid in Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 469–482. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Bafadhel, M.; Brightling, C.E.; Sciurba, F.C.; Curtis, J.L.; Martinez, F.J.; Pasquale, C.B.; Merrill, D.D.; Metzdorf, N.; Petruzzelli, S.; et al. Blood Eosinophil Counts in Clinical Trials for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 660–671. [CrossRef]

- Stolbrink, M.; Bonnett, L.J.; Blakey, J.D. Antibiotics for COPD Exacerbations: Does Drug or Duration Matter? A Primary Care Database Analysis. BMJ open Respir. Res. 2019, 6, e000458. [CrossRef]

- Fan, V.S.; Gylys-colwell, I.; Locke, E.; Sumino, K.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Thomas, R.M.; Magzamen, S. Overuse of Short-Acting Beta-Agonist Bronchodilators in COPD during Periods of Clinical Stability. Respir Med 2016, 116, 100–106. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Schiff, G.D.; Graber, M.L.; Onakpoya, I.; Thompson, M.J. The Global Burden of Diagnostic Errors in Primary Care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 484–494. [CrossRef]

- Sharafkhaneh, A.; Altan, A.E.; Colice, G.L.; Hanania, N.A.; Donohue, J.F.; Kurlander, J.L.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Altman, P.R. A Simple Rule to Identify Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Who May Need Treatment Reevaluation. Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 1310–1320. [CrossRef]

- Negewo, N.A.; Gibson, P.G.; Wark, P.A.; Simpson, J.L.; McDonald, V.M. Treatment Burden, Clinical Outcomes, and Comorbidities in COPD: An Examination of the Utility of Medication Regimen Complexity Index in COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2017, 12, 2929–2942. [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; He, B. Personalized Medicine in COPD Treatment. Curr. Respir. Care Rep. 2014, 3, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, E.F.M.; Wouters, B.B.R.A.F.; Augustin, I.M.L.; Franssen, F.M.E. Personalized Medicine and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med . 2017, 23, 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Alí, A.; Giraldo-Cadavid, L.F.; Karpf, E.; Quintero, L.A.; Aguirre, C.E.; Rincón, E.; Vejarano, A.I.; Perlaza, I.; Torres-Duque, C.A.; Casas, A. Frequency of Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations Due to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations in Patients Included in Two Models of Care. Biomedica 2019, 39, 748–758. [CrossRef]

- Kirenga, B.J.; Alupo, P.; van Gemert, F.; Jones, R. Implication of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report for Resource-Limited Settings: Tracing the G in the GOLD. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61.

- Bailey, K.L. The Importance of the Assessment of Pulmonary Function in COPD. Med. Clin. North Am. 2012, 96, 745–752. [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A. Digital Twin for Healthcare Systems. Front. Digit. Heal. 2023, 5, 1253050. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Albadawy, M. Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Prediction: Exploring Key Domains and Essential Functions. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Updat. 2024, 5, 100148. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.; Singh, S.; Pathania, M.; Gosavi, S.; Abhishek, S.; Parchani, A.; Dhar, M. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Medicine: Catalyzing a Sustainable Global Healthcare Paradigm. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1227091. [CrossRef]

- Quittner, A.L.; Nicolais, C.J.; Saez-Flores, E. 13 - Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes Into Research and Clinical Practice. In Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children; Wilmott, R.W., Deterding, R., Li, A., Ratjen, F., Sly, P., Zar, H.J., Bush, A.B.T.-K.D. of the R.T. in C. (Ninth E., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2019; pp. 231-240.e3 ISBN 978-0-323-44887-1.

- Siu, D.C.H.; Gafni-Lachter, L. Addressing Barriers to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Care: Three Innovative Evidence-Based Approaches: A Review. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2024, 19, 331–341. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).