1. Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrosing interstitial pneumonia characterized by progression and resulting in poor prognosis and high mortality [

1,

2]. In 2014, the first disease-modifying antifibrotic agents, including pirfenidone, were introduced and widely applied for the treatment of IPF [

3,

4]. However, maintaining the maximal dose of pirfenidone is difficult due to related adverse effects, and the efficacy of different doses of pirfenidone remains unclear [5-7]. Only a few retrospective observational studies have been reported [8-10]. Pirfenidone showed clinical efficacy of reduction in approximately 50% of lung function decline. However, it did not halt the progression of IPF [

3]. Several risk factors for poor prognosis in IPF have been reported [

11,

12], and lung function decline is one of the most important [

13,

14].

Recently, there has been increasing interest in and evidence for biomarkers for predicting the prognosis of IPF because blood biomarkers are relatively easy to assess and do not require much patient effort. In addition, they can be measured repeatedly and less invasively than pulmonary function [

15,

16]. Krebs von den Lugen-6 (KL-6) is a mucin-like glycoprotein produced by type 2 alveolar epithelial cells that is one of the most widely used biomarkers in IPF [

17,

18]. Recently, Huang et al. reported that a higher level of KL-6 at baseline was significantly related to high mortality in 47 IPF patients receiving nintedanib (HR 5.39, 95% CI: 1.16-24.97, p = 0.031) and demonstrated a trend predicting faster lung function decline [

19]. Therefore, in this study, we estimate the clinical efficacy of pirfenidone according to three doses for the prevention of disease progression and the roles of baseline and change of KL-6 for predicting disease progression in IPF patients receiving pirfenidone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a prospective, single-center, observational study of patients with IPF at Haeundae Paik Hospital, Republic of Korea, from April 2021 to March 2023. Patients were divided into three groups based on their daily dose of pirfenidone, which had been maintained for a minimum of six months before enrollment: (1) 600 mg, (2) 1,200 mg, and (3) 1,800 mg. The duration of the study was 12 months.

2.2. Study Subjects

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who were diagnosed with IPF according to the diagnostic criteria of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/Japanese Respiratory Society/Latin American Thoracic Association statement [

20]; (2) patients within five years of diagnosis of IPF; (3) patients who had maintained the fixed dosage of pirfenidone for at least six months and consented to continue the same dosage during the study period; and (4) patients who consented to participation in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who refused to provide informed consent for the study; (2) patients who could not maintain the fixed dose of pirfenidone due to a drug adverse event (including patients for whom pulmonary function decreased and were given the option to increase their dose of pirfenidone and those for whom the duration of medication was less than six months); and (3) patients who did not undergo the necessary tests for the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Haeundae Paik Hospital (IRB number: 2021-05-049). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to enrollment.

2.3. Clinical data

Clinical data for all enrolled patients were prospectively collected. Spirometry, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco), and the six-minute walk test (6MWT) were performed every six months from enrollment. Spirometry and DLco were measured according to the ATS/ERS recommendation, and the results were presented as a percentage of the normal predicted value [21-23]. The 6MWT was conducted in accordance with previously published guidelines [

24]. Laboratory tests, including KL-6, were measured every three months using the Nanopia KL-6 assay (SEKISUI MEDICAL, Tokyo, Japan). Disease progression was defined as an absolute decline ≥5% of forced vital capacity (FVC) (%, predicted value) or an absolute decline ≥10% of DLco (%, predicted value) over 12 months [

13]. All pirfenidone-related adverse events and IPF-related adverse events during the study period were recorded.

2.4. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the efficacy of pirfenidone according to dose for the prevention of lung function decline (change from baseline in FVC or DLco over 12 months), defined as disease progression. The secondary endpoint was the role of KL-6 in predicting disease progression.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Variables were summarized as frequency and percentage for categorical data and mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range (IQR)) for numeric data. Group differences were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and independent t-test, analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U test, or Kruskal-Wallis test for numeric data as appropriate. To determine whether distributions were normal, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test. We used error bar charts, spaghetti plots, and line graphs to visualize data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors independently related to disease progression. Considering the nature of the repeated measured data, a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with random intercepts was used. The GLMM model included repeated measures of numeric variables as dependent variables: group, time, and group x time interaction as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. To avoid assumptions about the covariance structure, we used an unstructured covariance matrix that was allowed to differ across groups for the GLMM analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 26.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R statistical software (version 3.4.0; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria,

http://www.r-project.org/). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study population and baseline characteristics

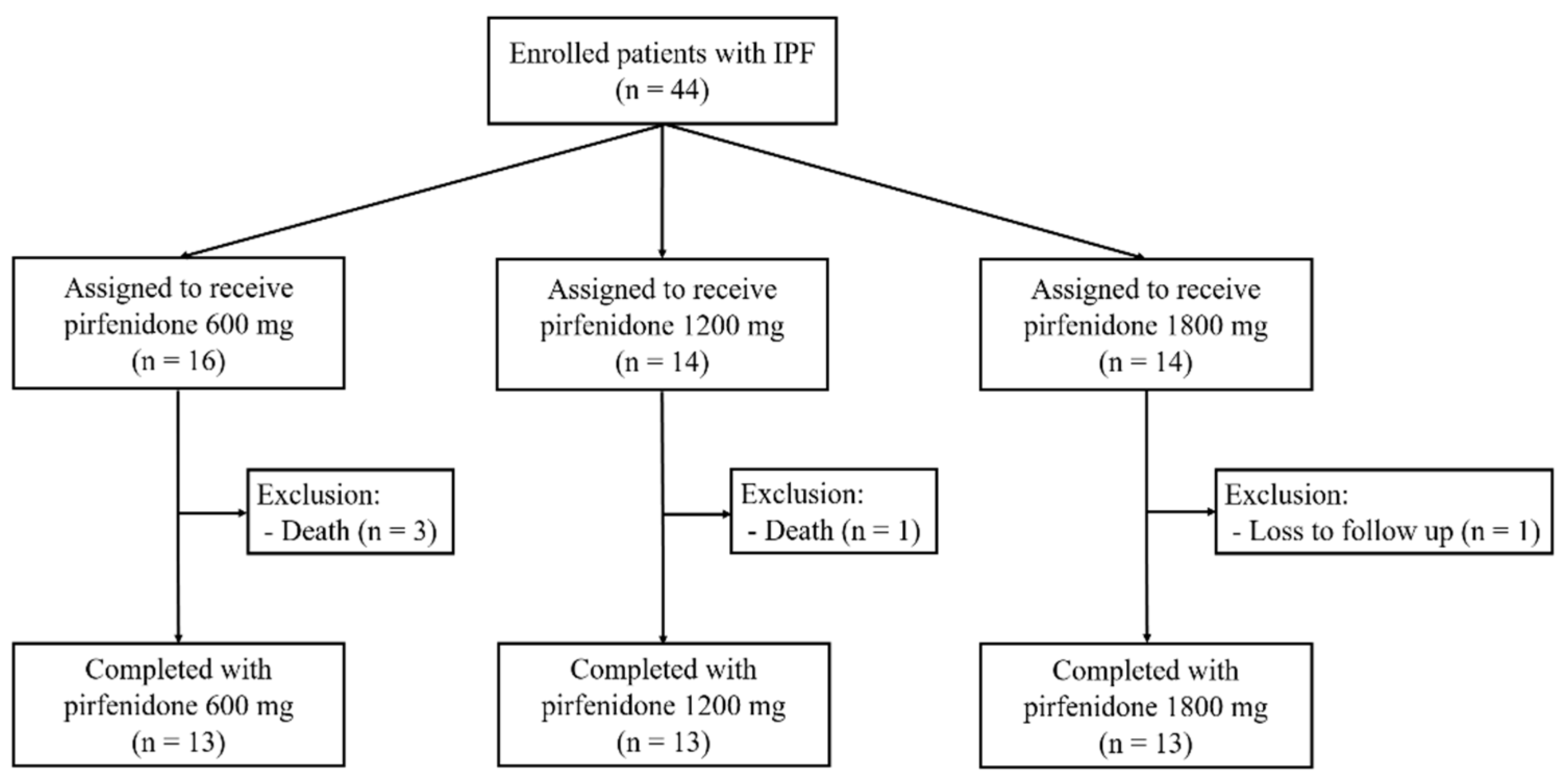

We enrolled a total of 44 patients, and four patients were excluded due to death (four patients) and drop-out (one patient) (

Figure 1). Finally, 13 patients were assigned to each group, and 39 patients completed the study.

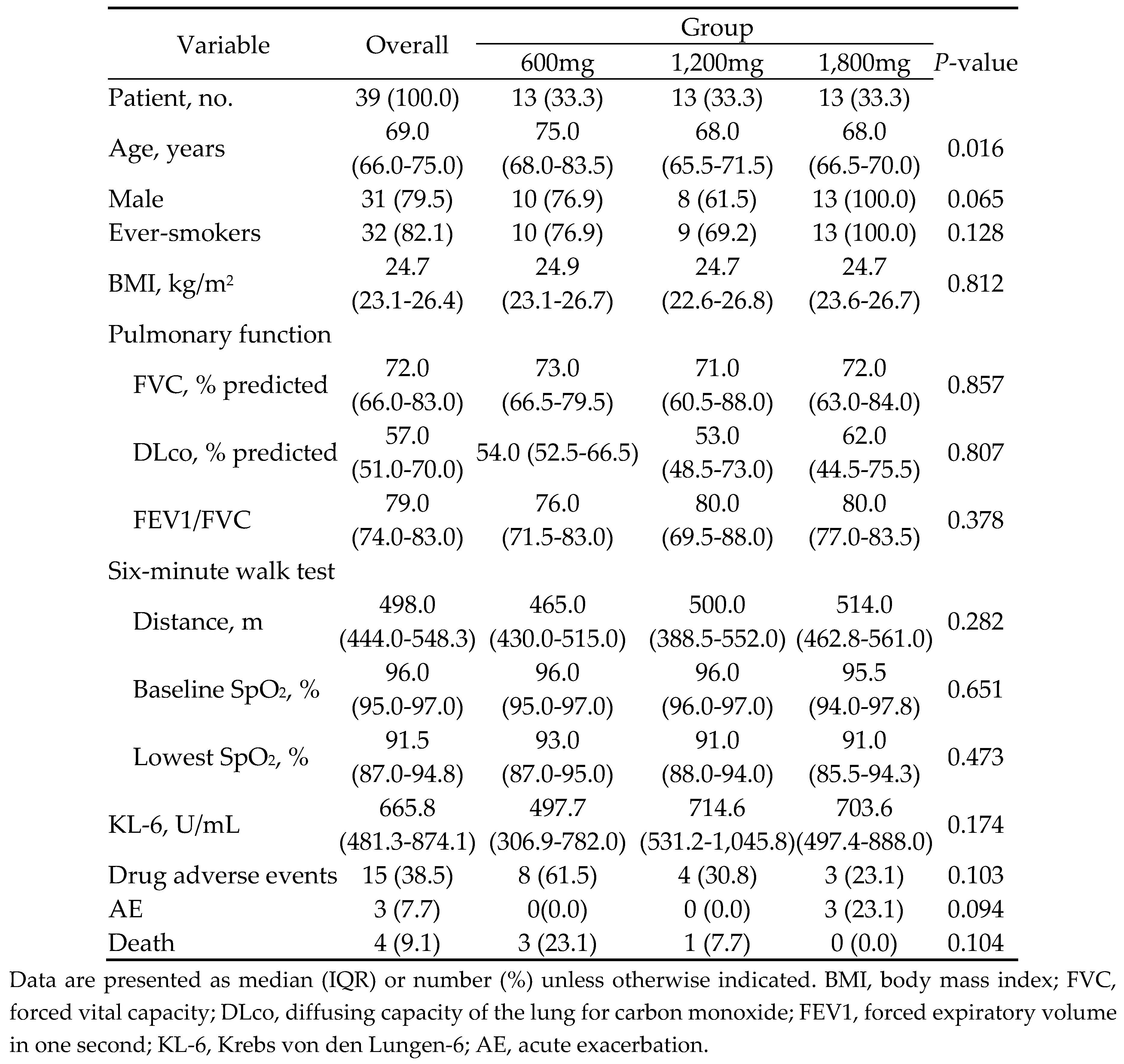

The median patient age was 71.7 years (IQR: 66.0-75.0 years), and 79.5% of patients were male. Most patients (82.1%) were ever-smokers. The 600 mg group was significantly older than the other groups (median age: 75.9 vs. 69.2 vs. 68.2 years, p = 0.016). The other baseline characteristics were similar among the three groups (

Table 1). Three patients died during the study period (600 mg group: 3 patients, 1,200 mg group: 1 patient), with all three among the group of six patients who suffered acute exacerbation (AE). There were no differences in rates of pirfenidone-related adverse events among the three groups (rate %: 61.5% vs. 30.8% vs. 23.1%, p = 0.103). The most common pirfenidone-related adverse event was anorexia (93.3%), followed by photosensitivity (26.7%) and itching (20.0%).

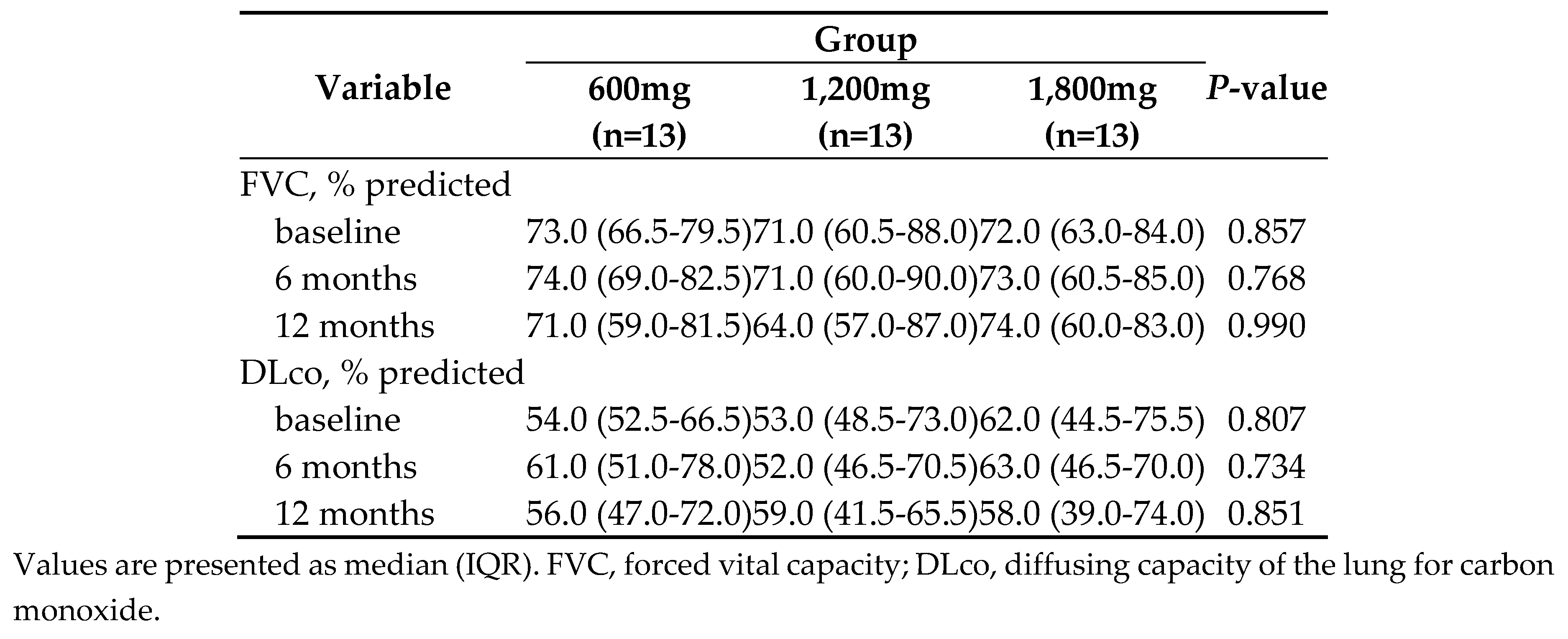

3.2. Primary endpoint

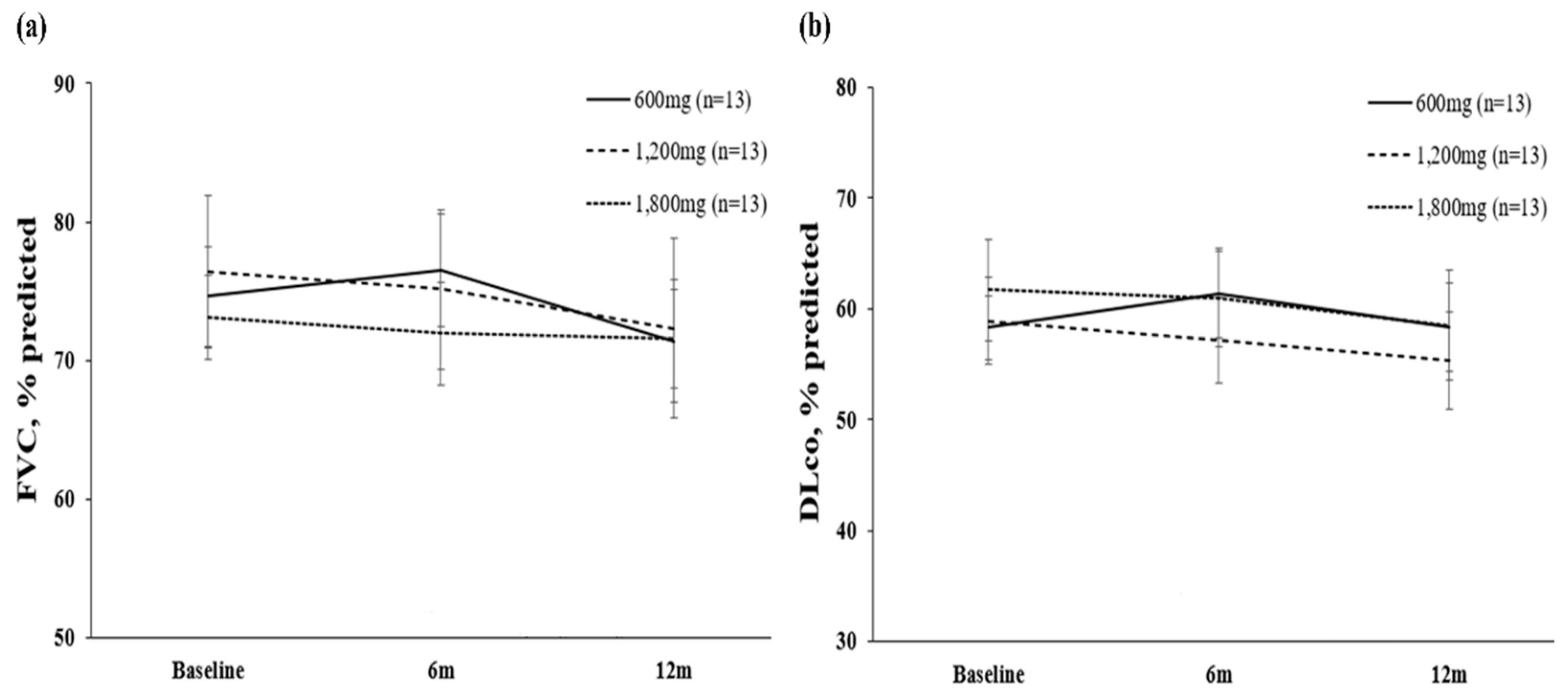

The overall median change of FVC over 12 months was -2.7 % (IQR: -9.1%, -1.2%). There was no difference in FVC decline among the three groups (change of FVC, % predicted value: -3.23 vs. -4.08 vs. – 1.54, p = 0.621) (

Table 2,

Figure 2). The overall median change of DLco over 12 months was – 3.8% (IQR: -13.6%, -3.7 %). There were no differences in DLco decline among the three groups (change of DLco, % predicted value: 0.00 vs. -.3.62 vs. -3.15, p = 0.437).

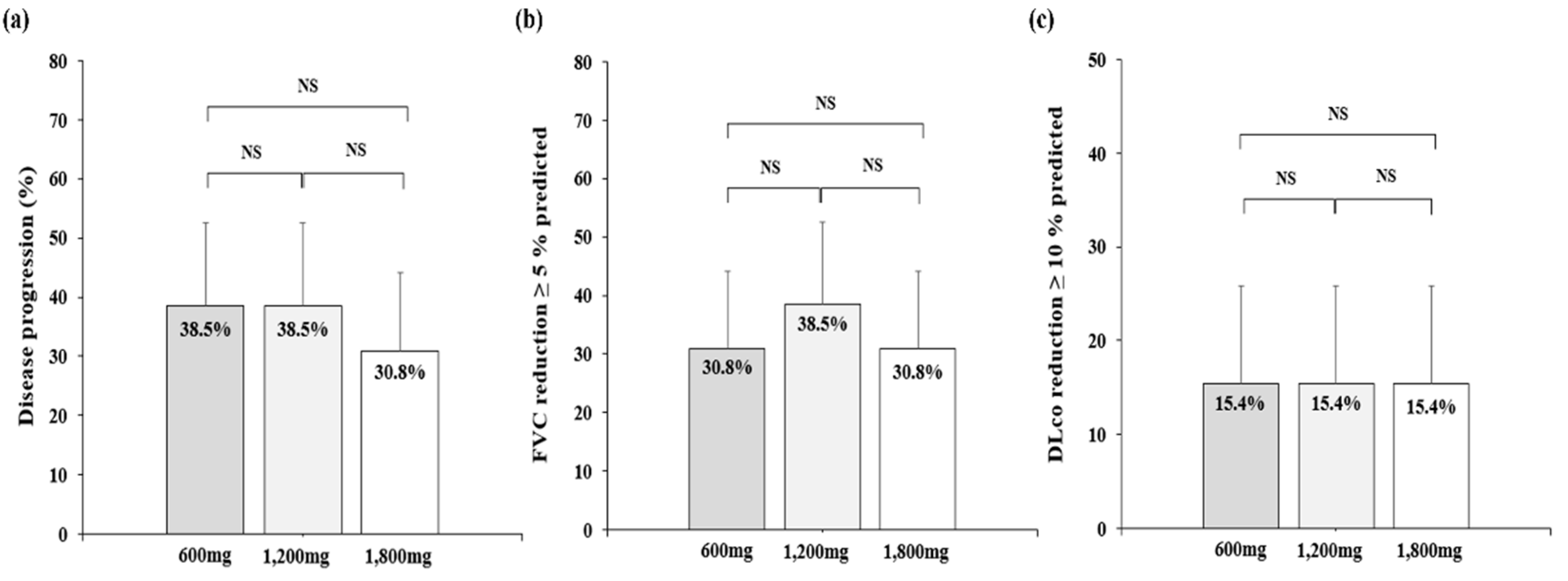

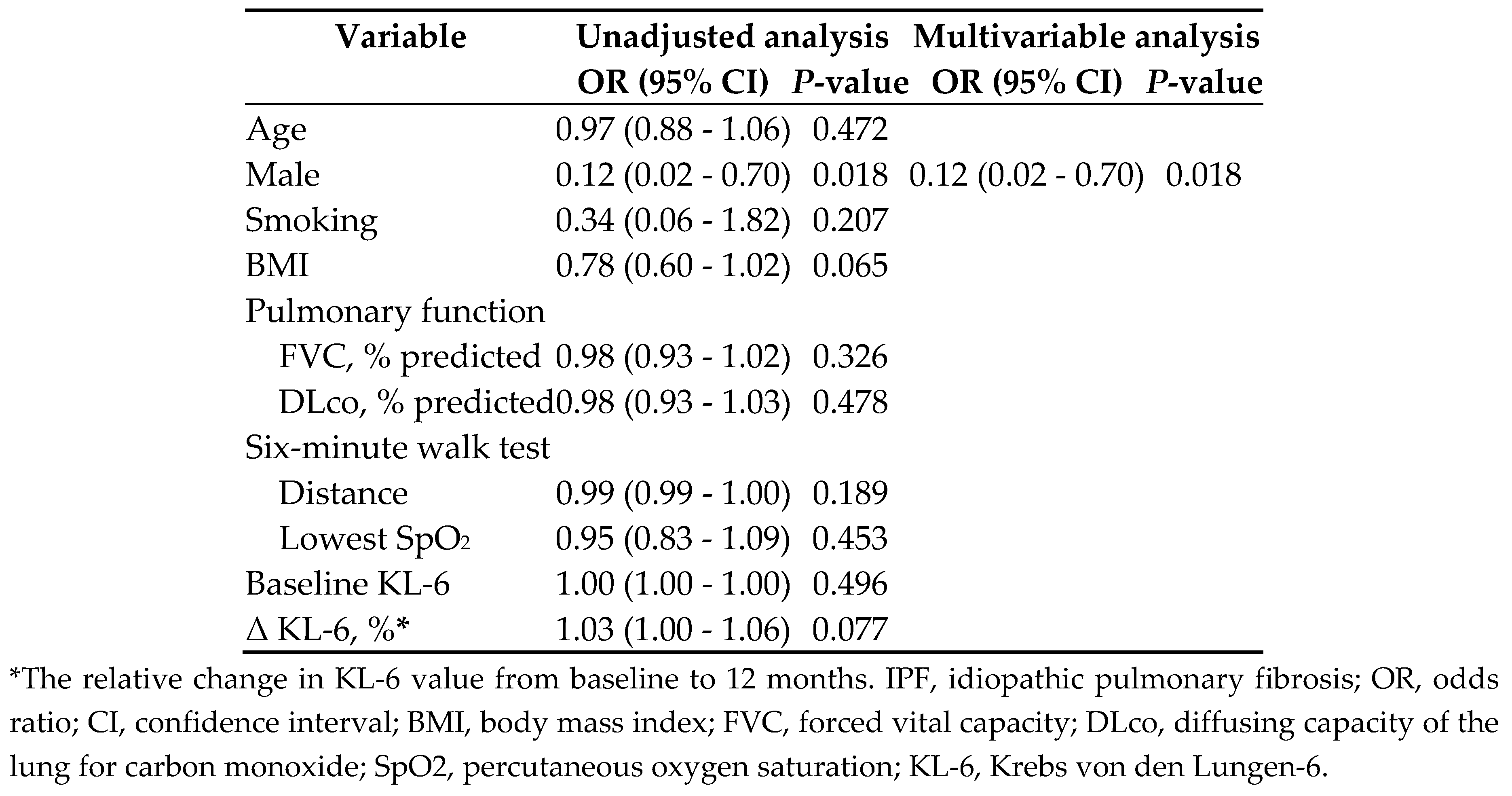

A total of 14 patients (35.9%) suffered disease progression (

Figure 3). There were no differences in the rate of disease progression among the three groups (38.5% vs. 38.5% vs. 30.8%, p = 1.000). In multivariate logistic regression for predicting disease progression, female gender was a statically significant risk factor (odds ratio (OR) 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.01-0.063, p = 0.015) (

Table 3).

3.2. Secondary endpoint

The median value of KL-6 in all patients was 668.1 U/mL (IQR: 465.3-924.5 U/mL). The baseline value and changes of KL-6 were similar among the three groups (median: 496.6 vs. 735.0 vs. 698.1 U/mL, p = 0.174), and there were no statistically significant risk factors for predicting disease progression. In a sub-group analysis of the baseline values of 27 patients (77.1%) with KL-6 ≥ 500 U/mL, the relative change of KL-6 showed a tendency to predict disease progression in multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR 1.03, 95% CI: 1.00-1.06, p = 0.74) (

Supplementary Table S1).

4. Discussion

This study was the first prospective study to demonstrate the efficacy of pirfenidone according to dose in disease progression, defined as the decline of FVC or DLco in patients with IPF. We observed no significant differences in disease progression rate according to the dose of pirfenidone over 12 months. Female gender was the only risk factor for disease progression in multivariate logistic regression analysis. KL-6 did not predict disease progression.

For East Asian patients with IPF, pirfenidone was approved with a recommended maximum dose of 1,800mg per day based on a previous study in Japan, in contrast to the recommended maximum dose in Europe and the United States, which is 2,400mg [

4,

25,

26]. However, previous post-marketing data reflecting real-world clinical settings showed that many East Asian patients with IPF are unable to take the recommended maximum dose of pirfenidone due to related adverse events [

5,

10]. To address this issue, previous research sought to estimate the efficacy of lower doses of pirfenidone for preventing lung function decline [

8,

9]. However, these studies have limitations such as retrospective design, small samples of research to review, and possible biases such as dose adjustments and different durations of fixed doses [5,8-10]. Therefore, we conducted a prospective study of IPF patients who maintained the same durations of fixed-dose administration of pirfenidone and the same evaluation period to determine lung function decline.

The most well-supported effect of pirfenidone is the reduction of lung function decline, which has been demonstrated through a number of previous studies [

3,

4,

27]. Our results showed that, regardless of dose, pirfenidone prevented lung function decline over 12 months, agreeing with the results of previous studies. A previous multicenter retrospective study of 338 non-standard patients with IPF who had received less than 1,800mg of pirfenidone showed a consistent effect on the prevention of disease progression (mean difference of FVC, % predicted and DLco, % predicted per year before and after treatment: 2.13 vs. 3.17%, p = 0.307) compared to a standard group who had received 1,800mg of pirfenidone [

8]. However, this result does not imply that maintaining the recommended maximum dose of pirfenidone is not imperative but rather emphasizes the importance of the best efforts to maintain the highest feasible dose of pirfenidone continuously considering each patient’s characteristics and pirfenidone-related adverse events in real practice.

Disease progression is one of the most crucial prognostic factors of mortality, and recent international guidelines defined a decline in FVC greater than 5% or in DLco greater than 10% over 12 months as one criterion of lung function decline [

13]. In this study, the baseline values and changes of KL-6 were not significant predictive factors for disease progression except in sub-group analysis of patients with KL-6 values over 500U/mL, among whom change of KL-6 between baseline and 12 months showed a tendency for predicting disease progression. In our study, the baseline KL-6 value was lower than 500 U/mL in 30.8% of patients. Previous studies reported conflicting results compared to our study, regarding KL-6 as one of the best biomarkers for predicting disease progression [28-30]. Our results may conflict with the result of previous studies showing the predictive capacity for disease progression in patients with IPF due to the substantial number of patients with baseline values less than 500 U/mL of KL-6 in this study, as well as the small total number of enrolled patients. Previous studies suggested a diagnostic cut-off value of IPF around 500 U/mL, and the predictive capacity for disease progression might be greater for higher values of KL-6 [

29,

31,

32]. In addition, the different definitions of disease progression we used compared to previous studies might contribute to these conflicting results [28-30]. Additional research is needed to further assess the role of KL-6 in disease progression.

There are some limitations to this study. First, it was a single-center cohort study with a small number of patients, which limited the generalizability of our findings. However, the baseline characteristics and results were similar overall to those of patients in other studies [8-10,19]. Second, we defined disease progression solely as lung function decline, excluding criteria such as symptoms and radiologic evidence. However, in this study, the rate of disease progression was 35.9%, which was not lower than previous studies [

4,

33]. Therefore, this difference should have minimal impact on the primary endpoint of lung function decline. Third, due to the prospective nature of this study aimed at prohibiting dose changes of pirfenidone, there is possible bias because IPF patients with relatively stable and low rates of pirfenidone-related adverse events were included.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated no significant differences in disease progression rate among IPF patients who were assigned fixed doses of 600mg, 1,200mg, or 1,800mg of pirfenidone over 12 months. This result emphasizes the importance of consistently maintaining the maximum feasible dose of pirfenidone in real practice. Further large-scale research is needed to elucidate the role of KL-6 in predicting disease progression.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Logistic regression analysis for disease progression in IPF patients with high baseline KL-6 levels (≥500 U/mL).

Author Contributions

HYL, SYJ, and JHL contributed to the study design, analysis of literature, manuscript conceptualization, and preparation. MYH, JHJ, and DWK contributed to data curation and validation of data and results of the study. JHJ and JHK contributed to the analysis of data and reviewed the manuscript, providing critical feedback. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by ILDONG Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., Republic of Korea. The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of data, or the preparation of the manuscript. Otherwise, the authors of this study have nothing to disclose.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Haeundae-Paik Hospital (approval no: 2021-05-049).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects who participated in this study were informed of the study protocol and provided written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Travis, W.D.; Costabel, U.; Hansell, D.M.; King, T.E., Jr.; Lynch, D.A.; Nicholson, A.G.; Ryerson, C.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Selman, M.; Wells, A.U.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 188, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.E., Jr.; Bradford, W.Z.; Castro-Bernardini, S.; Fagan, E.A.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.K.; Gorina, E.; Hopkins, P.M.; Kardatzke, D.; Lancaster, L.; et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, P.W.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; Glassberg, M.K.; Kardatzke, D.; King, T.E., Jr.; Lancaster, L.; Sahn, S.A.; Szwarcberg, J.; et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 2011, 377, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.P.; Park, M.S.; Oh, I.J.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, Y.W.; Park, J.S.; Uh, S.T.; Kim, Y.S.; Jegal, Y.; Song, J.W. Safety and Efficacy of Pirfenidone in Advanced Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Nationwide Post-Marketing Surveillance Study in Korean Patients. Adv Ther 2020, 37, 2303–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, T.; Azuma, A.; Inoue, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Chida, K.; Bando, M.; Niimi, Y.; Kakutani, S.; Suga, M.; Sugiyama, Y.; et al. All-case post-marketing surveillance of 1371 patients treated with pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Investig 2015, 53, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Niimi, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Kakutani, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Board, P.A. Post-marketing surveillance of pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Japan: Interim analysis of 973 patients. Eur Respir J 2012, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Lee, J.K.; Choi, S.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Cho, Y.J.; Yoon, H.I.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.T.; Kim, Y.W.; Park, J.S. Efficacy of lower dose pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in real practice: a retrospective cohort study. Korean J Intern Med 2022, 37, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.G.; Lee, T.H.; Hong, Y.; Ryoo, J.; Heo, J.W.; Gil, B.M.; Kang, H.S.; Kwon, S.S.; Kim, Y.H. Effects of low-dose pirfenidone on survival and lung function decline in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): Results from a real-world study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Moon, S.W.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, K.S.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Efficacy of low dose pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: real world experience from a tertiary university hospital. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 21218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durheim, M.T.; Judy, J.; Bender, S.; Baumer, D.; Lucas, J.; Robinson, S.B.; Mohamedaly, O.; Shah, B.R.; Leonard, T.; Conoscenti, C.S.; et al. In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A US Cohort Study. Lung 2019, 197, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryerson, C.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ley, B.; Lee, J.S.; Mooney, J.J.; Jones, K.D.; Elicker, B.M.; Wolters, P.J.; Koth, L.L.; King, T.E., Jr.; et al. Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: the ILD-GAP model. Chest 2014, 145, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi-Shah, B.A.; Chowdhury, B.A. Forced vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis--FDA review of pirfenidone and nintedanib. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clynick, B.; Corte, T.J.; Jo, H.E.; Stewart, I.; Glaspole, I.N.; Grainge, C.; Maher, T.M.; Navaratnam, V.; Hubbard, R.; Hopkins, P.M.A.; et al. Biomarker signatures for progressive idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainer, A.; Faverio, P.; Busnelli, S.; Catalano, M.; Della Zoppa, M.; Marruchella, A.; Pesci, A.; Luppi, F. Molecular Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: State of the Art and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Nagata, N.; Kumazoe, H.; Oda, K.; Ishimoto, H.; Yoshimi, M.; Takata, S.; Hamada, M.; Koreeda, Y.; Takakura, K.; et al. Prognostic value of serial serum KL-6 measurements in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Investig 2017, 55, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N.; Hattori, N.; Yokoyama, A.; Kohno, N. Utility of KL-6/MUC1 in the clinical management of interstitial lung diseases. Respir Investig 2012, 50, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.H.; Kuo, C.W.; Chen, C.W.; Tseng, Y.L.; Wu, C.L.; Lin, S.H. Baseline plasma KL-6 level predicts adverse outcomes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis receiving nintedanib: a retrospective real-world cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2021, 21, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; van der Grinten, C.P.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005, 26, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, B.L.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Cooper, B.G.; Jensen, R.; Kendrick, A.; MacIntyre, N.R.; Thompson, B.R.; Wanger, J. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, N.; Crapo, R.O.; Viegi, G.; Johnson, D.C.; van der Grinten, C.P.M.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Enright, P.; et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005, 26, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.J.; Puhan, M.A.; Andrianopoulos, V.; Hernandes, N.A.; Mitchell, K.E.; Hill, C.J.; Lee, A.L.; Camillo, C.A.; Troosters, T.; Spruit, M.A.; et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014, 44, 1447–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, H.; Ebina, M.; Kondoh, Y.; Ogura, T.; Azuma, A.; Suga, M.; Taguchi, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Nakata, K.; Sato, A.; et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2010, 35, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Johnson, W.C.; Lockhart, D.; Mageto, Y. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with a new antifibrotic agent, pirfenidone: results of a prospective, open-label Phase II study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 159, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabel, U.; Albera, C.; Lancaster, L.; Hormel, P.; Hulter, H.; Noble, P. Final analysis of RECAP, an open-label extension study of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Eur Respir J 2016, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Jehn, L.B.; Costabel, U.; Boerner, E.; Waelscher, J.; Theegarten, D.; Taube, C.; Bonella, F. Serum KL-6 as a Biomarker of Progression at Any Time in Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Kim, J.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, H.C. Baseline serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 as a biomarker for the disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep-Uk 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Han, Q.; Huang, J.; Ou, Y.; Chen, M.; Wen, Y.; Mosha, S.S.; Deng, K.; Chen, R. Sequential changes of serum KL-6 predict the progression of interstitial lung disease. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, 4705–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Z.; Wang, Q.B.; Liu, T.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, B.K. Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) as a diagnostic marker for pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem 2023, 114, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.J.; Park, K.J.; Ko, D.H.; Koo, H.J.; Lee, S.M.; Song, J.W.; Lee, W.; Lee, H.K.; Do, K.H.; Chun, S.; et al. Analytical and Clinical Performance of the Nanopia Krebs von den Lungen 6 Assay in Korean Patients With Interstitial Lung Diseases. Ann Lab Med 2019, 39, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurkova, M.; Kriegova, E.; Kolek, V.; Lostakova, V.; Sterclova, M.; Bartos, V.; Doubkova, M.; Binkova, I.; Svoboda, M.; Strenkova, J.; et al. Effect of pirfenidone on lung function decline and survival: 5-yr experience from a real-life IPF cohort from the Czech EMPIRE registry. Respir Res 2019, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).