Submitted:

21 August 2024

Posted:

22 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

Association Between ALI/GAP/NLR/BMI/FVC/DLCO/6MWT and Albumin

Survival Curve Based on Predictors of IPF Mortality

Discussion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Q.; Cox, I.A.; Campbell, J.A.; Xia, Q.; Otahal, P.; Graaff, B.; Corte, T.J.; Teoh, A.K.; Walters, E.H.; Palmer, A.J. Mortality and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 14, 8, 00591-2021. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.D; Reffett, T.; Brown, A.W.; Fischer, C.P.; Shlobin, O.A.; Ahmad, S.; Weir, N.; Sheridan, M.J. The Red Cell Distribution Width as a Prognostic Indicator in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2013, 143, 1692–1698. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, A.U.; Desai, S.R.; Rubens, M.B.; Goh, N.S.; Cramer, D.; Nicholson, A.G.; Colby, T.V.; du Bois, R.M.; Hansell, D.M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A composite physiologic index derived from disease extent observed by computed tomography. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 962–969. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, H.R.; King, T.E., Jr.; Bartelson, B.B.; Vourlekis, J.S.; Schwarz, M.I.; Brown, K.K. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 538–542. [CrossRef]

- Desai, O.; Winkler, J.; Minasyan, M.; Herzog, E.L. The Role of Immune and Inflammatory Cells in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 43. [CrossRef]

- Jouneau, S.; Kerjouan, M.; Rousseau, C.; Lederlin, M.; Llamas-Guttierez, F.; De.; Latour, B.; Guillot, S.; Vernhet, L.; Desrues, B; Thibault, R. What are the best indicators to assess malnutrition in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients? A cross-sectional study in a referral center. Nutrition 2019, 62, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Jouneau, S.; Crestani, B.; Thibault, R.; Lederlin, M.; Vernhet, L.; Valenzuela, C.; Wijsenbeek, M.; Kreuter, M.; Stansen, W.; Quaresma, M,; et. al. Analysis of body mass index, weight loss and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 312. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hong, C.; Guo, Z.; Huang, H.; Ye, L. Association between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among stroke patients: NHANES, 1999–2018. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1370322. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, D.; Kanzaki, Y.; Sakane, K.; Ito, T.; Sohmiya, K.; Hoshiga, M. Prognostic impact of a novel index of nutrition and inflammation for patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Heart Vessels 2020, 35, 1201–8. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Huang, B.; Wang, R.; Tie, H.; Luo, S. The prognostic value of advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) in elderly patients with heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 934551. [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M,; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et. al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 18-47. [CrossRef]

- Ley, B.; Ryerson, C.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ryu, J.H.; Tomassetti, S.; Lee, J.S.; Poletti, V,; Buccioli, M.; Elicker, B.M.; Jones, K.D.; et. al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 684–9. [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic. Dis. 1987, 40, 373-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuyts, W.A.; Agostini, C.; Antoniou, K.M.; Bouros, D.; Chambers, R.C.; Cottin, V.; Egan, J.J.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Lories, R.; Parfrey, H.; Prasse A.; et. al. The pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis: a moving target. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 1207–18. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 519–31. [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Integrating mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1339–50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adane, T.; Melku, M.; Worku, Y.B.; Fasil, A., Aynalem, M.; Kelem, A.; Geteva, S. The association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and Glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Azab, B.; Camacho-Rivera, M.; Taioli, E. Average values and racial differences of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio among a nationally representative sample of United States subjects. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e112361. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, N.Y.; Na, S.H.; Youn, Y.H.; Shin, C.S. Reference values of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte-monocyte ratio, platelet-lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume in healthy adults in South Korea. Medicine 2018, 97, e11138. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinellu, A.; Paliogiannis, P.; Sotgiu, E.; Mellino, S.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, E.; Negri, S.; Collu, C.; Pintus, G.; Serra, A.; et .al. Blood Cell Count Derived Inflammation Indexes in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung 2020, 198, 821–827. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, M.; Bergantini, L.; Carleo, A.; Cameli, P.; Perrone, A.; Fossi, A.; Sestini, P.; Bargagli, B. Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte Ratio in Bronchoalveolar Lavage From IPF Patients: A Novel Prognostic Biomarker? Minerva Med. 2022, 113, 526-531. [CrossRef]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Satta, R.; Deligia, G.; Farina, G.; Bassu, S.; Mangoni, A.A.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. Associations between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios and the presence and severity of psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 19, 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Fois, A.G.; Sotgia, S.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, E.; Pirina, P.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 48, e12984. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Fois, A.G.; Sotgia, S.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, E.; Pirina, P.; Negri, S.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and clinical outcomes in COPD: recent evidence and future perspectives. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 170113. [CrossRef]

- Mochimaru, T.; Ueda, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Asano, K.; Fukunaga, K. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a novel independent predictor of severe exacerbation in patients with asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 337–339. [CrossRef]

- Mikolasch, T.A.; George, P.M.; Sahota, J.; Nancarrow, T.; Barratt, S.L.; Woodhead, F.A.; Kouranos, V.; Cope, V.S.A.; Creamer, A.W.; Fidan S.; et. al. Multi-center evaluation of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR) ratio as an independent predictor of mortality and clinical risk stratifier in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101758. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Xie, B.; Ye, O.; Ban, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Geng, J.; et. al. Blood monocyte counts as a prognostic biomarker andpredictor in Chinese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 955125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takuma, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Kono, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Hashimoto, D.; Yokomura, K.; Mori, K.; Shimizu, M.; Inoue, Y.; Yasui, H.; et.al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio being associated with mortality risk in patients receiving antifibrotic therapy. Respir. Med. 2024, 223, 107542. [CrossRef]

- Achaiah, A.; Rathnapala, A.; Pereira, A.; Bothwell, H.; Dwivedi, K.; Barker, R.; Iotchkova, V.; Benamore, R.; Hoyles, R.K.; Ho, L.P. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as an indicator for disease progression in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, e001202. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Kono, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Hashimoto, D.; Yokomura, K.; Imokawa, S.; Inoue, Y.; Hozumi, H.; Karayama, M.; Furuhashi, K.; et. al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, BMJ Open Respir Res 2023, 10, e001763. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S.; Song, H.; Yang, K.; Dai, H.; Wang, C. Serum prealbumin is a prognostic indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin. Respir. J. 2019, 13, 493-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Mori, K.; Aono, Y.; Kono, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Yokomura, K.; Hozumi, H.; Karayama, M.; Furuhashi, K.; Enomoto, N.; et. al. Cause of mortality and sarcopenia in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis receiving antifibrotic therapy. Respirology 2021, 26, 171–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Mori, K.; Aono, Y.; Kono, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Yokomura, K.; Naoi, H.; Hozumi, H.; Karayama, M.; Furuhashi, K.; et. al. Combined assessment of the GAP index and body mass index at antifibrotic therapy initiation for prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouneau, S.; Rousseau, C.; Lederlin, M.; Lescoat, A.; Kerjouan, M.; Chauvin, P.; Luque-Paz, D.; Guillot, S.; Oger, E.; Vernhet, L.; et. al. Malnutrition and decreased food intake at diagnosis are associated with hospitalization and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1335–1342. [CrossRef]

- Jouneau, S.; Crestani, B.; Thibault, R.; Lederlin, M.; Vernhet, L.; Yang, M.; Morgenthien, E.; Kirchgaessler, K.; Cottin, V. Post hoc analysis of clinical outcomes in placebo- and Pirfenidone-treated patients with iPF stratified by BMi and weight loss. Respiration 2022, 101, 142–154. [CrossRef]

- Mochizuka, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Kono, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Hashimoto, D.; Yokomura, K.; Inoue, Y.; Yasui, H.; Hozumi, H.; Karayama, M.; Furuhashi, K.; et. al. Respirology 2023, 28, 775–783. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subjects | |

|---|---|

| Gender, M/F(n/%) | 80 (78.4) /22 (21.6) |

| Age, years | 70.4±7.39 |

| Smokers, never/current/ex (n) | 13 (12.7)/ 16 (15.7)/ 73 (71.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1±1.79 |

| Disease duration (months) | 33.4±8.61 |

| AE (n,%) | 15 (14.7) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.4±0.62 |

| GAP Stages | |

| I | 44 (43.1) |

| II | 32 (31.4) |

| III | 26 (25.5) |

| GAP index (1/2/3/4/5/6/7) | 2 (2.0)/12 (11.8)/30 (29.4)/16 (15.7)/16 (15.7)/19(18.6)/7(6.9) |

| Pulmonary function test | |

| FVC, %-pred | 70.2±7.54 |

| FEV1, %-pred | 74.7±7.43 |

| DLCO, % | 49.7±11.82 |

| 6MWT (meters) | 359.2±49.42 |

| Laboratory variables | |

| Neutrophils (10^9/L) | 5.50±1.26 |

| Lymphocytes (10^9/L) | 1.7 ±0.35 |

| Monocytes (10^9/L) | 1.7 ±0.35 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.5±0.69 |

| LDH, U/L | 212.9±65.90 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22.8±28.70 |

| AST (U/L) | 20.8±7.11 |

| NLR | 3.3±1.05 |

| ALI | 29.6±15.32 |

| Survivor/Nonsurvivor (n/%) | 91 (89.2)/ 11 (10.8) |

| ALI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (IQR) | p | ||

| GAP stages | 1 (0-3) | 44 | 38.5 (18.60)a |

0.000 |

| 2 (4-5) | 32 | 21.6 (7.35)b | ||

| 3 (6-8) | 26 | 17.5 (10.72)c | ||

| FVC(median split) | <70 | 44 | 21.1 (9,58) | 0.000 |

| ≥70 | 58 | 31,3 (20,05 | ||

| DLCO | <51 | 49 | 20.3 (10.75) | 0.000 |

| ≥51 | 53 | 32.0 (20.04) | ||

| 6MWT (meters) | <350 | 36 | 19.6 (11.63) | 0.001 |

| ≥350 | 66 | 29.7 (17.65) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ≤1 | 65 | 27,5 (19,96) | 0.233 |

| >1 | 37 | 22,1 (12,59) | ||

| GAP stage 1 (n=44) | GAP stage 1 (n=44) | GAP stage 3 (n=26) | ||

| BMI | 25.2±1.30a | 23.7±1.50b | 22.5±1.42c | 0,000 |

| NLR | 2.5±0.71a | 3.6±0.70b | 4.1±1.15b,c | 0,000 |

| Albumin | 4.0±0.53a | 3.36±0.45b | 2.93±0.11c | 0,000 |

| Neutrophils (10^9/L) | 4.5±0.84a | 6.1±0.76b | 6.5±1.08b,c | 0,000 |

| Lymphocytes (10^9/L) | 1,6 (0) | 1.7 (0) | 1.6 (0) | 0,070 |

| Monocytes (10^9/L) | 0.8 (0) | 0.7 (0) | 0.9 (0) | 0,114 |

| ALI | 38 (16,59)a | 25,1 (7.43)b | 17.6 (4.27)c | 0,000 |

|

ALI Quantile 1 [< 21,2] (n=36) |

ALI Quantile 2 [21,3-31,4] (n=33) |

ALI Quantile 3 [>31,5] (n=33) |

||

| BMI | 22.9±1.38a | 24.1±1.73b | 25.2±1.43c | 0,000 |

| NLR | 4.2±0.96a | 3,3±0.45b | 2.3±0.56c | 0,000 |

| Albumin | 2.8±0.48a | 3.7±0.41b | 4.0±0.55c | 0,000 |

| Neutrophils (10^9/L) | 6.4±0,96a | 5.7±0.86b | 4.2±0.76c | 0,000 |

| Lymphocytes (10^9/L) | 1.6 (0)a | 1.7 (0)b | 1.9 (1)b,c | 0,000 |

| Monocytes (10^9/L) | 0,9 (0) | 0,8 (0) | 0.8 (0) | 0,534 |

| Gap stage | FVC | DLCO | 6MWT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALI | r | -0.815 | 0.498 | 0.637 | 0.445 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| BMI | r | -0.634 | 0.406 | 0.493 | 0.499 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| NLR | r | 0.638 | -0.348 | -0.525 | -0.257 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.009 | |

| Albumin | r | -0.636 | 0.410 | 0.431 | 0.412 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

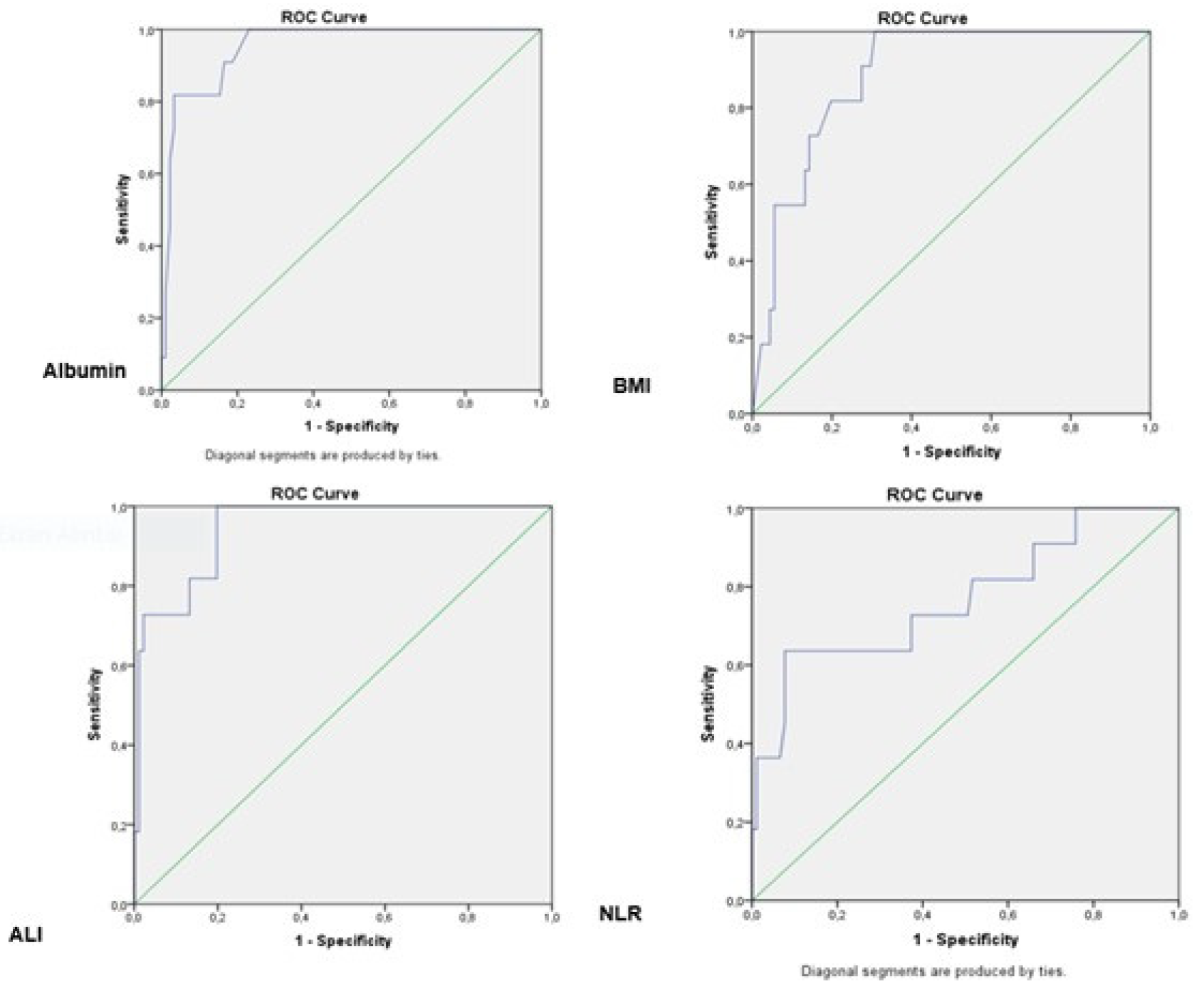

| AUC (%95) | Cut off | p | sensitivity (%) | specifity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin | 0.952 (0.904-1,000) | 2.45 | 0.000 | 63,6 | 97,8 |

| BMI | 0.885 (0.811-0.959) | 21,84 | 0,000 | 54,5 | 94,5 |

| ALI | 0.945 (0.892-0.998) | 11,20 | 0,000 | 63,6 | 98,9 |

| NLR | 0.768 (0.600-0.936) | 5,25 | 0,004 | 36,4 | 98,9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).