1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has deeply affected the world and reaffirmed the importance of front-line scientific research [

1]. Much remains to be understood about the immune response triggered by SARS-CoV-2, including the variation in immunological memory for long-term protection, why some patients develop more aggressive forms of the disease, and the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying disease control [

2]. However, it is common ground that the immune response is critical for restraining infection and disease spread. In this scenario, antibodies are pivotal in the protective cellular and molecular pathways triggered by natural infection, vaccine-based and other immunotherapeutic strategies used to combat COVID-19.

Antibodies perform multiple functions, and their Fc portion carries out most of them [

3]. Immunoglobulins (Igs) bind specifically to pathogen epitopes via their hypervariable Fab portion and can prevent them from entering or damaging cells through neutralization. Moreover, the Complement cascade can be activated after Ig binding, leading to the lysis of pathogens or infected cells. Ig can also trigger the phagocytosis of opsonized pathogens and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), which are mediated by their Fc portion [

4]. All Fc-mediated Ig functions are carried out by Fc receptors (FcR); among them, the FcRs for IgG (FcγR) are the most relevant. The FcγR family comprises activating and inhibitory receptors bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) or immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM), respectively. Multiple cell types express them and have well-described signaling pathways [

5]. There is FcαR for IgA, FcμR for IgM, and other membrane-bound FcRs [

6], but cytoplasmic FcRs are less explored.

Two FcRs are found in the intracellular environment: the neonatal FcR (FcRn,

FCGRT gene) and tripartite motif-containing protein 21 (TRIM21). Despite its name, FcRn is widely expressed throughout human adult life. It cycles between the plasma membrane and within intracellular endosomes, binding to IgG under acidic but not neutral pH conditions. When the extracellular environment is neutral, IgG must be endocytosed and coupled to FcRn in acidic endosomes. Then, FcRn:IgG complexes can be sorted to the plasma membrane for recycling, while other cargo components are targeted for lysosomal degradation. The IgGs are released once reexposed to a neutral extracellular medium [

7]. This process contributes to the unusually long half-life of circulating IgG and is likely one of the bases for many IgG-based infusion treatments [

8].

The other intracellular FcR participates in a more complex cellular response, leading to pathogen destruction in proteasomes and inflammation. TRIM21 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase, a homodimer that forms a 1:1 complex with an antibody [

9], and at least 24 TRIM21 homodimers must bind to an adenovirus particle for full virus neutralization [

10]. The degradation of invading viruses by TRIM21 is known as antibody-dependent intracellular neutralization (ADIN), a rapid and efficient process [

11]. It is important to highlight that among FcRs, TRIM21 has the highest known affinity for IgG but also binds to IgA [

12] and IgM [

13]. TRIM21 is particularly important for the antiviral response because it mediates the degradation of IgG-coated viruses by proteasomes, and the resulting fragments can activate the antiviral innate immune response [

14]. The initial sequence of monoubiquitination is still under debate, as experimental

in vitro conditions may profoundly affect the ubiquitination stage. The current model of TRIM21 activation predicts that after dimerization, TRIM21 interacts with the E2 enzymes UBE2W or UBE2D2, which are more promiscuous E2 enzymes [

15], promoting the monoubiquitination of TRIM21 at its N-terminus. Then, UBE2N and UBE2V2 build a polyubiquitin chain on the N-terminal monoubiquitin. This step is thought to trigger immune signaling and the proteasomal degradation of TRIM21, IgG, and the virus [

16]. Then, the ATPase p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP), an enzyme with segregase and unfoldase activity, is required for TRIM21-dependent proteasome degradation of viral capsids [

17]. Finally, after deubiquitination by Poh1 [

14,

18], proteasomal activity generates cytoplasmic fragments of virus components, including genomic sequences of either DNA or RNA, depending on the pathogen. These immunological danger signals are then recognized by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as cGAS, RIG-1, and MDA5. Activating these and other danger sensors leads to an antiviral response and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators that ultimately contribute to infection control [

19]. In the context of COVID-19, the literature has demonstrated the role of TRIM21 in promoting the ubiquitination of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid. Then, polyubiquitination results in the tagging of the N protein for degradation by the host cell proteasome. The alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and micron variants can be subjected to TRIM21-dependent degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [

20].

In this work, we used publicly available scRNA-seq data to study the repertoire of intracellular FcRs in adaptive and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and myeloid cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). The samples were obtained from healthy individuals and COVID-19 patients with mild or severe symptoms. When comparing the groups of sick patients, myeloid cells primarily transcribed the FCGRT gene, especially in patients with severe symptoms. Since myeloid cells represented approximately 60% of all cells identified in BALF samples from this group, FcRn may impact infection, but its effects on clinical recovery remain unknown. TRIM21 transcription was upregulated in most subpopulations of ILCs, as in adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells from mild cases compared to those from uninfected individuals and severe cases. Therefore, we only investigated the TRIM21 signaling pathway in the mild group, as it could serve as a protective mediator. Although ILCs were most abundant in these BALF samples, representing approximately 83% of all cells, some key downstream components of the pathway were absent, such as UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2V2, and PSMD14 (Poh1). Therefore, ILCs are likely not central to the TRIM21 pathway in patients with mild symptoms. Regarding adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells, most populations, especially adaptive lymphoid cells, transcribed UBE2D2, UBE2N, UBE2V2, and VCP. Although the PRRs RIG-1 (DDX58) and MDA5 (IFIH1) were transcribed, NLRP3 and some critical components of the NF-κB pathway, such as IKBKG, p105 (NFKB1), and p100 (NFKB2) were not observed. Accordingly, most cells in mild cases were negative or had low IL1B, IL18, and TNF transcriptional levels. These results suggest that, although in a limited number of cells, the TRIM21 FcR may protect COVID-19 patients on two fronts: conventional virus destruction by proteasomes in adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells and downregulation of the pathway’s inflammatory branch, preventing an exacerbated inflammatory response.

2. Materials and Methods

According to the authors who uploaded the primary dataset used [

21], the patients were categorized as severe if admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and/or invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation was necessary. Patients with mild symptoms had fever during cell collection, respiratory symptoms, and moderate infection with bilateral pneumonia, as evidenced by computed tomography (CT) imaging. However, they required no admission to ICU or mechanical ventilation. The median age of patients with mild COVID-19 symptoms was 36 yo, and that of severely ill individuals was 65 yo. After CT analysis and other laboratory tests, control samples were obtained from three healthy individuals free of tuberculosis, tumors, and other lung diseases. The median age was 24 yo. We used another dataset [

22] that consisted of BALF samples from 21 patients with severe COVID-19. All patients were admitted to ICU and/or were on noninvasive/mechanical ventilation; the median age was 67 years. The scRNA-seq data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession code GSE157344 (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157344).

We deployed the CellHeap [

23] processing workflow for scRNA-seq data analysis in the Santos Dumont (SD) Supercomputer (

https://sdumont.lncc.br), which has an installed processing capacity of 5.1 Petaflop/s. The workflow received as input the BALF scRNA-seq data for the main dataset, PRJNA608742, from the NCBI GEO repository (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA608742). Liao et al. [

21] generated this dataset and considered the samples of twelve patients as input data. Three samples corresponded to healthy individuals (control), three were from mild patients, and six had severe COVID-19 symptoms. Each sample had two read files for paired-end runs.

We used the 10x Genomics pipeline CellRanger v.6.1.0 [

24] with default parameters for sample demultiplexing. Then, the reads were aligned, and gene expression was quantified using the GRCh38 human genome and a SARS-CoV-2 genome (NC_045512) as a reference. The

count function of the Cellranger software automatically identified the infected cells, and in this work, all reads associated with SARS-CoV-2 received the “sarscov2” prefix. Then, we executed an R script that created two files, separating infected from noninfected cells. We selected only SARS-CoV-2noninfected cells for all analyses to avoid possible gene expression subversions that intracellular infection could generate. Therefore, analyzing uninfected cells in the lungs would provide a more accurate understanding of the functions of various cell types.

We used the SoupX [

25] package version 1.6.2 to estimate ambient RNA contamination for quality control. Moreover, we used the Seurat [

26] v4 package to identify and remove low-quality cells according to the following three criteria commonly used for scRNA-seq quality control processing [

27]: Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) count < 301; Genes expressed < 151 and > 3000; and > 20% mitochondrial RNA.

Each dataset was normalized and scaled with default parameters for clustering analysis using Seurat v4. After normalization, we executed the following steps:

-The FindVariableGenes function detected the variable genes with the “vst” method and a number of features equal to 2000;

-The datasets were integrated with Seurat’s FindIntegrationAnchors and IntegrataData functions by running a canonical correlation analysis (CCA) on each subset. We then performed dimensionality reduction using the PCA and UMAP algorithms;

-In the final step of the clustering process, we calculated a shared nearest neighbor (SSN) graph between all cells through the FindClusters function with a resolution parameter equal to 1.2; to identify markers for every cluster compared to all remaining cells, we used the FindAllMarkers function with default thresholds.

We used the CellAssign (version 0.99.21) [

28] and Sctype [

29] R packages for cell type annotation. The Sctype was used only for the ILCs since their annotation required support for negative markers, which CellAssign does not provide. The complete list of markers for CellAssign and ScType for each cell type is provided in the Results section.

We generated ridge plots for the noncomparative analysis of cell types using Seurat’s RidgePlot function. Essentially, the Ridge Plot is a density plot, i.e., a representation of the distribution of gene expression. It uses a kernel density estimate to show the probability density function of a gene expression for a given cell type. Therefore, we analyzed transcriptional modulations using a noncomparative strategy to analyze FcRs and downstream molecules involved in immune regulation, virus danger recognition, and inflammatory response. To calculate average expression values, we used Seurat’s AverageExpression function. Using an R script, we filtered cells for each gene of interest and each cell type for which the expression level was above zero. Then, we applied Seurat’s AverageExpression function to the filtered cell sets.

We analyzed the percentage of each cell cluster (adaptive lymphoid cells, myeloid cells, or ILCs) and their subpopulations in the three patient groups. Considering the control group as an example, we considered the total number of cells in the sample as “Ac”; in this case, there were 18,585 cells, as indicated in the public repository. Then, considering the total number of adaptive lymphoid cells (Bc), myeloid cells (Cc), and ILCs (Dc), the following formulas were used to determine the percentage of each cell cluster: (100*Bc)/Ac; (100*Cc)/Ac; and (100*Dc)/Ac respectively. The number of unidentified cells (Uc) was calculated as Ac - (Bc + Cc + Dc), and the percentage of Uc was calculated as (100*Uc)/Ac. The same procedure was performed for both groups of COVID-19 patients.

3. Results

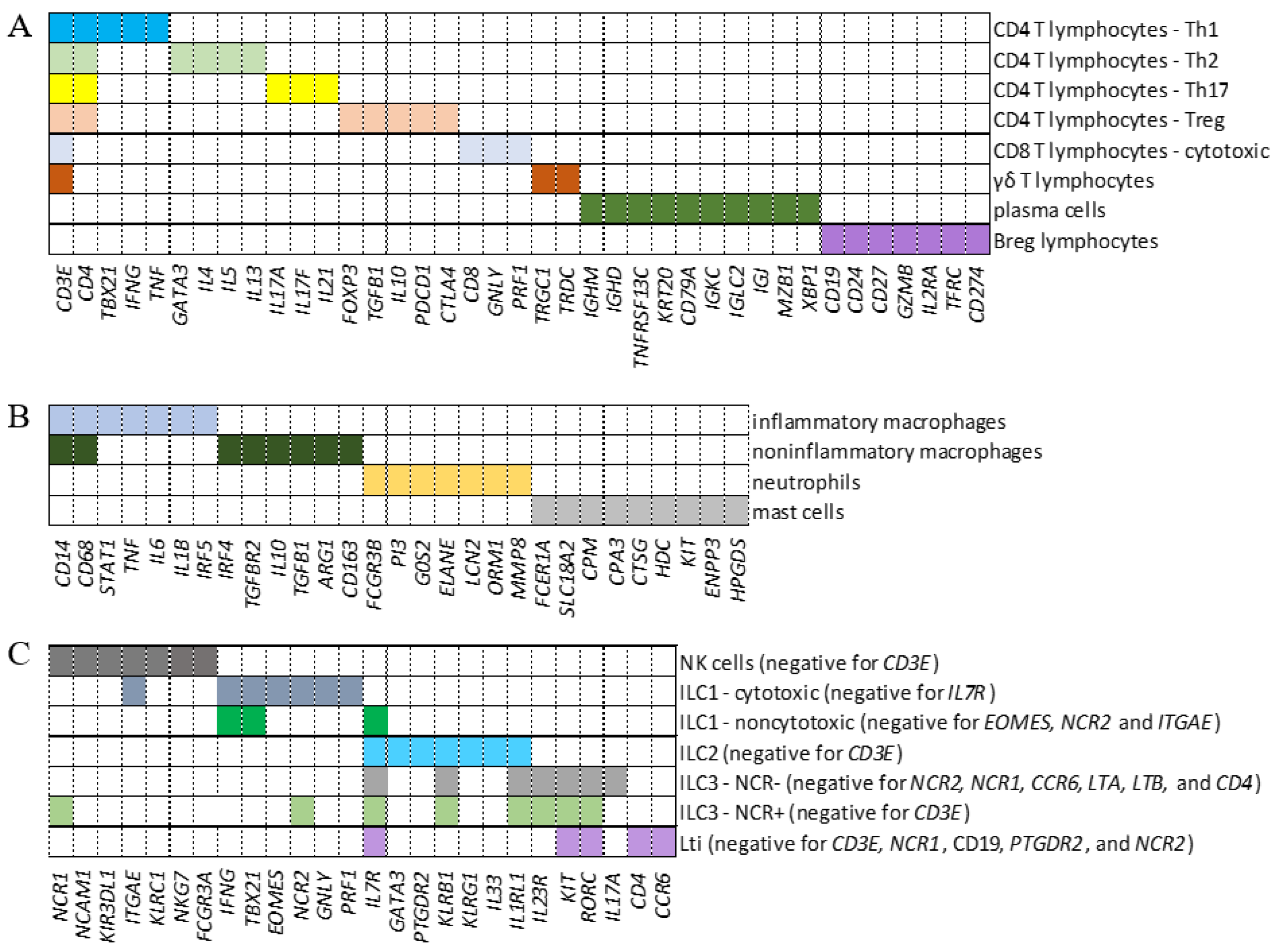

To analyze the transcription of intracellular FcRs in adaptive lymphoid cells, myeloid cells, and ILCs from BALF samples, we defined genes whose combination composed a signature phenotype to identify CD4

+ Th1, Th2, Treg, Th17, CD8

+ cytotoxic cells, γδ T lymphocytes, plasma cells, Breg, inflammatory and noninflammatory macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells (Fig. 1A and B). Moreover, ILC1, noncytotoxic ILC1, ILC2, ILC3 NCR

-, LTi, NK, and ILC3 NCR

+ cells were identified (Fig. 1C). As an exploratory analysis, we wanted multiple cell types included with maximum confidence for cell identification. Considering the numerous genes that could be used to discern each cell population, we first tested two previously published combinations of genes [

21,

30]. However, when comparing both combinations, the analysis showed an enormous difference in the number of cells identified per population. More significantly, there was a considerable difference in the repertoire of molecules transcribed, such as cytokines and chemokines, besides a lack of transcription of the expected cell markers per population (data not shown). Identifying myeloid cells was particularly challenging. Then, we decided to design new combinations of marker genes (Fig. 1) to identify each cell subpopulation and used the well-known profile of membrane FcRs for data curation [

31], always in control individuals. Then, after numerous tests to ensure that the identified cell subpopulation would transcribe the signature membrane FcRs, the same combinations of genes were used to identify each cell population in COVID-19 patients with mild or severe symptoms.

Figure 1.

Identification of cell populations. Panels A, B, and C show the combinations of genes used to identify adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (C), respectively. Each colored segment shows the combination of genes that must be simultaneously transcribed to identify all indicated subpopulations. In the case of ILCs, the genes indicated in parentheses as negative represent a group of additional genes that must not be transcribed for this cellular classification.

Figure 1.

Identification of cell populations. Panels A, B, and C show the combinations of genes used to identify adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (C), respectively. Each colored segment shows the combination of genes that must be simultaneously transcribed to identify all indicated subpopulations. In the case of ILCs, the genes indicated in parentheses as negative represent a group of additional genes that must not be transcribed for this cellular classification.

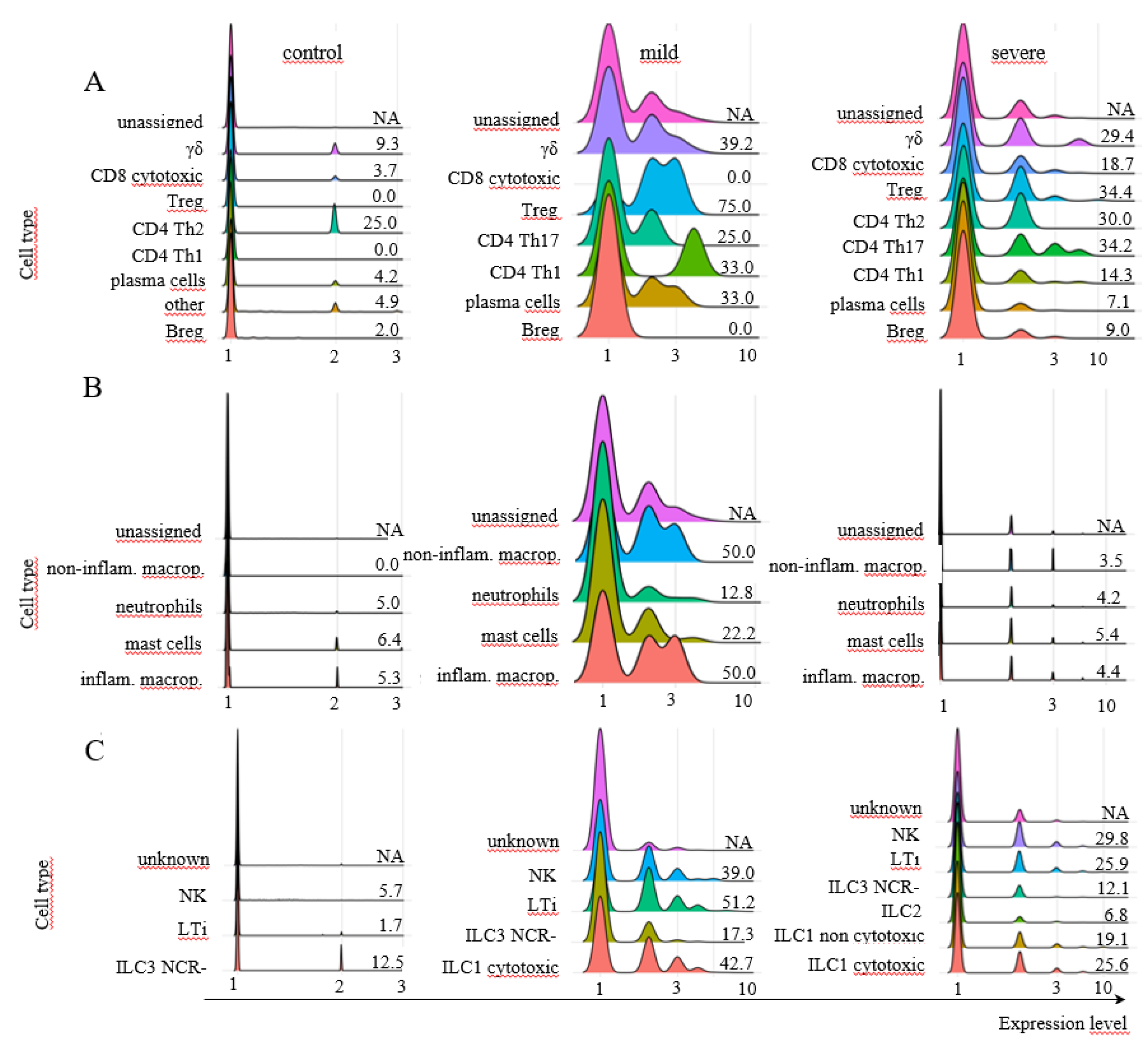

Approximately 62% of the cells from control individuals were identified as myeloid cells (Fig. 2A), with approximately 21% being ILCs and less than 4% being adaptive lymphoid cells (Fig. 2A), which were represented mainly by CD8+ cytotoxic T and Breg lymphocytes (Fig. 2B). Regarding the prevalent population of myeloid cells, neutrophils composed almost the entire population (Fig. 2C), while NK cells were the main ILC population (Fig. 2D). In mild cases, approximately 83% of the cells were identified as ILCs, with less than 6% being adaptive lymphoid or myeloid cells (Fig. 2A). The main subpopulations were γσ T lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 2B), mast cells and neutrophils (Fig. 2C), and a similar distribution of ILCs as ILC3 NCR-, cytotoxic ILC1s, LTi, and NK cells (Fig. 2D). In severe cases, almost 61% of the cells were myeloid cells, followed by approximately 30% ILCs and approximately 10% adaptive T lymphocytes (Fig. 2A). There were CD8 cytotoxic and plasma cells (Fig. 2B), and almost 90% of the myeloid cells were identified as mast cells, with approximately 10% being neutrophils (Fig. 2C). Moreover, mostly NK cells and cytotoxic ILC1s were among the ILCs (Fig. 2D). The predominant cellular populations found in severe cases were primarily cells with cytotoxic or inflammatory functions, which are correlated with disease severity.

Figure 2.

Percentages of different cellular populations among patient groups. The percentage of each cell cluster is shown in A, and the percentages of each subpopulation per cluster are shown in the other panels. Adaptive lymphoid cells are shown in B; myeloid cells are shown in C; and ILCs are shown in D. The total number of cells analyzed per group of patients is shown at the top of the figure.

Figure 2.

Percentages of different cellular populations among patient groups. The percentage of each cell cluster is shown in A, and the percentages of each subpopulation per cluster are shown in the other panels. Adaptive lymphoid cells are shown in B; myeloid cells are shown in C; and ILCs are shown in D. The total number of cells analyzed per group of patients is shown at the top of the figure.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that ILCs were identified as a prominent group of lung cells in patients with mild COVID-19. ILCs are crucial for immune defense against infectious pathogens and play an important role in regulating adaptive immunity, tissue remodeling, and repair. They do not rearrange antigen-specific receptors, and although they are found in all tissues, ILCs are particularly enriched in the lungs [

32] and mucosal surfaces. In patients with COVID-19, the number of ILCs in peripheral blood decreases greatly in patients with more severe symptoms [

33], and clinical recovery is correlated with increased numbers of ILCs, especially ILC2s [

34,

35,

36]. In this work, ILCs were identified based on the literature [

37,

38].

After identifying the cell types, we analyzed FCGRT transcription in adaptive lymphoid cells. We observed modest and variable transcriptional levels of this receptor in control individuals and patients with mild symptoms, except for CD4+ Th1 lymphocytes (Fig. 3A). In severe cases, there was an enrichment of γσ T lymphocytes transcribing the FCGRT, followed by CD4+ Th2 cells (Fig. 3A). Myeloid cells, on the other hand, showed higher percentages of positive cells and levels of FCGRT transcription in all three groups of patients (Fig. 3B), with 34.6% to 37.3% of mast cells transcribing the receptor in patients with mild and severe COVID-19, respectively. Regarding neutrophils, another prevalent cell population in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, we observed that 19.2% of the cells transcribed FCGRT in mild cases (Fig. 3B). Regarding ILCs, most ILC3 NCR- cells in the control group transcribed FCGRT. After infection, NK cells were the main population transcribing this gene in mild cases. In severe cases, NK and LTi cells mainly transcribed the FCGRT gene (Fig. 3C). The possible protective effect of FcRn on lung cells from COVID-19 patients remains to be verified via functional in vitro assays, especially in severe cases, as almost 40% of mast cells transcribed this receptor, the primary cell population found in this group.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional profile of FCGRT in different cellular populations. The transcriptional profile of FCGRT in the indicated subpopulations of adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and ILCs (C) is shown for control individuals or patients with mild or severe symptoms of COVID-19. The information next to each population represents the percentage of cells whose FCGRT transcriptional level was above zero. The colors assigned to each histogram may vary between cell populations, and correct identification should be based on the indicated population name. No CD4+ Th2 lymphocytes were identified in the samples from mild cases. To calculate the percentage of FCGRT+ cells, we used the number of total cells per subpopulation per patient group (considered 100%). This number was revealed by the phenotypic analysis indicated in the MM section. Then, we determined the number of FCGRT+ cells per subpopulation. NA means not available.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional profile of FCGRT in different cellular populations. The transcriptional profile of FCGRT in the indicated subpopulations of adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and ILCs (C) is shown for control individuals or patients with mild or severe symptoms of COVID-19. The information next to each population represents the percentage of cells whose FCGRT transcriptional level was above zero. The colors assigned to each histogram may vary between cell populations, and correct identification should be based on the indicated population name. No CD4+ Th2 lymphocytes were identified in the samples from mild cases. To calculate the percentage of FCGRT+ cells, we used the number of total cells per subpopulation per patient group (considered 100%). This number was revealed by the phenotypic analysis indicated in the MM section. Then, we determined the number of FCGRT+ cells per subpopulation. NA means not available.

When we analyzed

TRIM21 transcription, very few adaptive lymphoid cells, myeloid cells, and ILCs from control individuals transcribed this receptor (Fig. 4A-C). However, this scenario changed in cells obtained from individuals with mild symptoms, where only Breg and CD8

+ cytotoxic T cells remained negative for the receptor after infection (Fig. 4A-C). In severe cases, the transcription of

TRIM21 was reduced in most adaptive lymphoid populations compared to mild cases (Fig. 4A) and decreased to near zero in myeloid cells and ILCs (Fig. 4B-C). Moreover, the poor transcription of

TRIM21 in myeloid, ILCs, and adaptive lymphoid cells from severe cases was confirmed using another dataset [

22] (data not shown). The profile and levels of

FCGRT transcription were also similar in severe cases when comparing both datasets (data not shown). Considering that TRIM21 transcription was primarily upregulated in cells from individuals with mild symptoms and that this pathway may be protective against infection, we further investigated its downstream components only in this group of patients.

Figure 4.

Transcriptional profile of TRIM21 in different cell populations. The transcriptional profile of TRIM21 is shown for adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and ILCs (C). The samples were obtained from healthy control individuals or patients with mild or severe symptoms of COVID-19. The information next to each subpopulation represents the percentage of cells with TRIM21 transcriptional levels above zero. To calculate the percentages, we used the number of total cells per subpopulation (100%) per patient group, revealed by the phenotypic analysis in the MM section, and the number of TRIM21+ cells per subpopulation was used. No CD4+ Th2 lymphocytes were identified in the samples from mild cases. NA means not available.

Figure 4.

Transcriptional profile of TRIM21 in different cell populations. The transcriptional profile of TRIM21 is shown for adaptive lymphoid cells (A), myeloid cells (B), and ILCs (C). The samples were obtained from healthy control individuals or patients with mild or severe symptoms of COVID-19. The information next to each subpopulation represents the percentage of cells with TRIM21 transcriptional levels above zero. To calculate the percentages, we used the number of total cells per subpopulation (100%) per patient group, revealed by the phenotypic analysis in the MM section, and the number of TRIM21+ cells per subpopulation was used. No CD4+ Th2 lymphocytes were identified in the samples from mild cases. NA means not available.

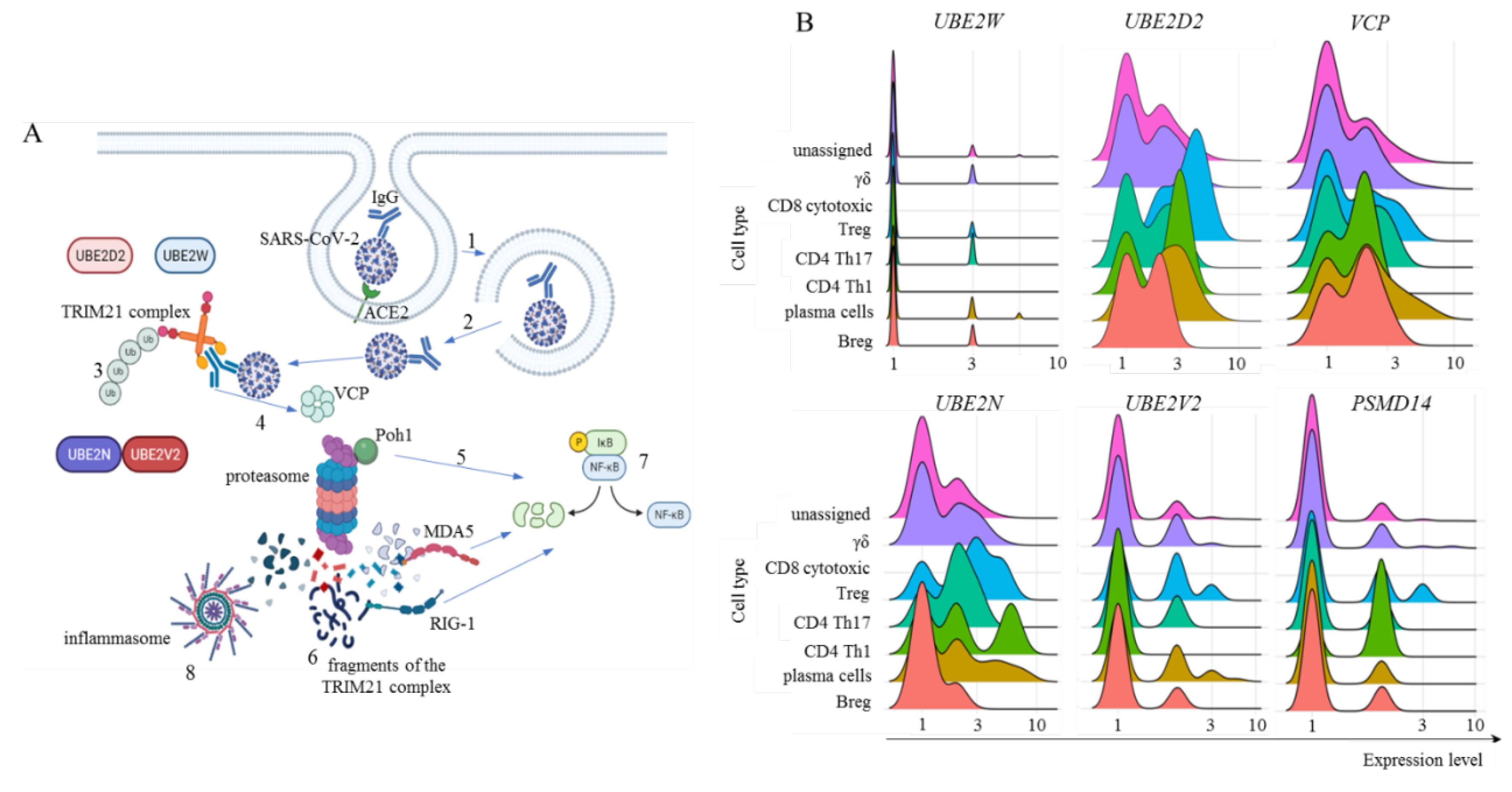

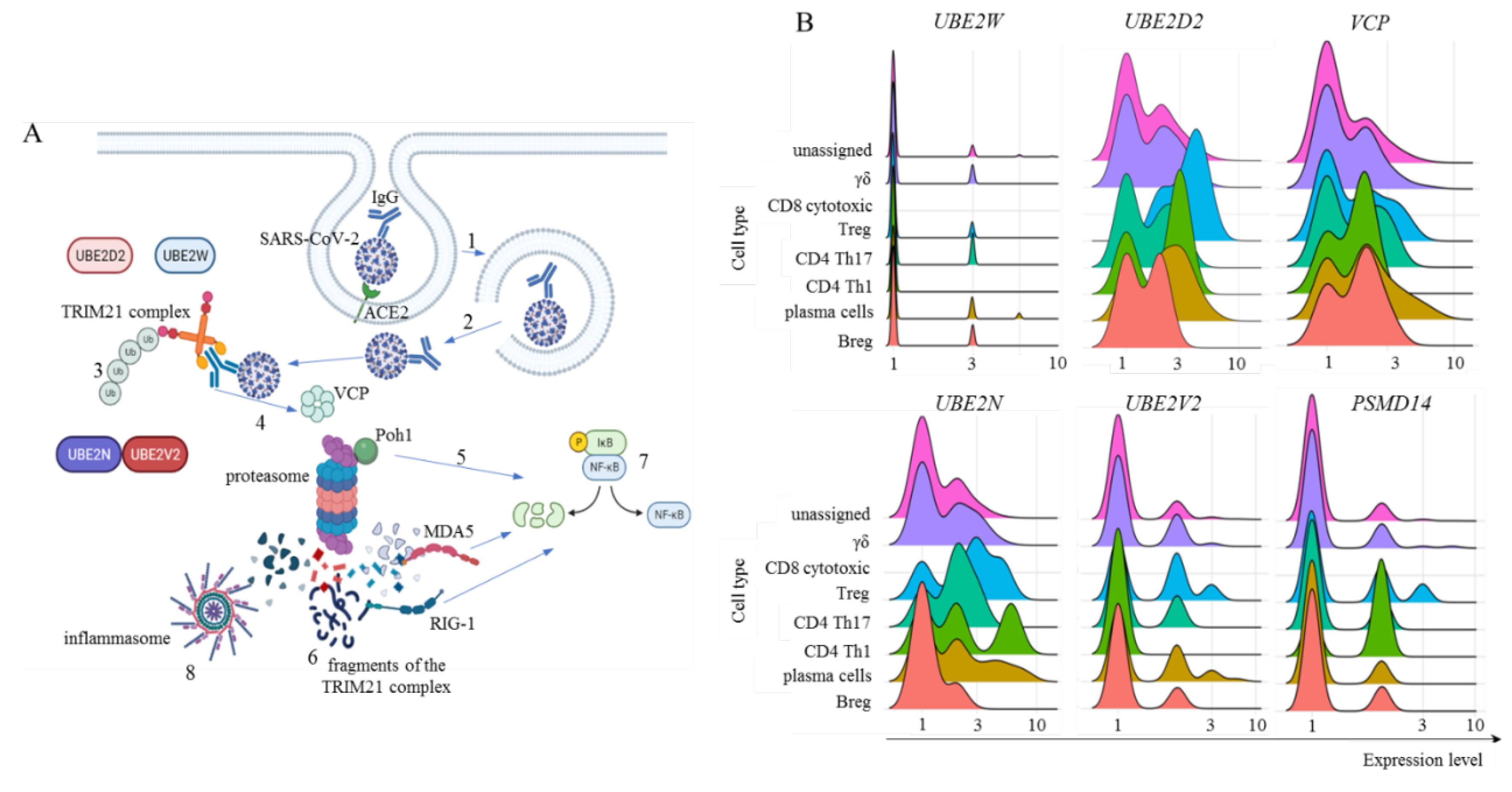

To activate the TRIM21 pathway, the SARS-CoV-2 virus must be enveloped in IgG and evade endosomal vesicles to enter the cytoplasm. (Fig. 5A; a general schematic representation of the pathway). It is currently accepted that the binding of TRIM21 to Ig leads to clustering-induced RING domain dimerization. TRIM21 then interacts with the E2 enzyme UBE2W, which first promotes the monoubiquitination of the N-terminus of TRIM21 for UBE2N and UBE2V2 to build a K63-linked polyubiquitin chain. However, it was recently described that UBE2D2 can also initiate polyubiquitination followed by UBE2N and UBE2V2 activity [

16] (Fig. 5A). Then, some proteasomal substrates require previous enzymatic processing, as in the case of large intact viral capsids. For this purpose, in the TRIM21-dependent virus neutralization pathway, the TPase p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP) is necessary [

17]. Furthermore, before proteasomal degradation, ubiquitin(s) must be removed from the substrate, and the proteasome-associated deubiquitinase Poh1 (

PSMD14) is known to be required for virus degradation [

14] (Fig. 5A). In fact, Poh1 has dual functions: deubiquitination and induction of the inflammatory response through the activation of NF-κB. Ultimately, multiple viral fragments are generated in the cytoplasm and are made available for danger sensor recognition, such as MDA-5, RIG-1, and inflammasomes, like NLRP3, and others to trigger the transcription and signaling of multiple inflammatory mediators (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

General TRIM21 pathway and its components transcription in adaptive lymphoid cells. Panel A represents the general TRIM21 pathway, where IgG-coated SARS-CoV-2 viruses invade host cells primarily by interacting with the ACE2 receptor and are enclosed in endosomal vesicles (1). Then, the virus bound to IgG must escape the endosome and reach the cytoplasm (2), where TRIM21 dimers bind to the Fc portion of IgG with high affinity. The addition of monoubiquitin is performed by UBE2W or UBE2D2, the structural base for polyubiquitination by UBE2N and UBE2V2 (3). For TRIM21-dependent virus proteasomal degradation, VCP activity is required (4), in addition to substrate deubiquitination by Poh1, which can directly activate the innate antiviral response by activating NF-κB (5). After degradation, cytoplasmic virus fragments (6), including genomic dsRNA recognized by MDA-5 and RIG-1, can also activate NF-κB (7). Moreover, nongenomic fragments of the virus can activate inflammasomes such as NLRP3 (8), all of which contribute to the production of type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines. Panel B shows our analysis of E2 ubiquitin enzymes UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2N, and UBE2V2 transcriptional levels. Moreover, Poh1 (PSMD14 gene) and VCP transcription were analyzed in adaptive lymphoid cells from COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms. The artwork was prepared using BioRender.com.

Figure 5.

General TRIM21 pathway and its components transcription in adaptive lymphoid cells. Panel A represents the general TRIM21 pathway, where IgG-coated SARS-CoV-2 viruses invade host cells primarily by interacting with the ACE2 receptor and are enclosed in endosomal vesicles (1). Then, the virus bound to IgG must escape the endosome and reach the cytoplasm (2), where TRIM21 dimers bind to the Fc portion of IgG with high affinity. The addition of monoubiquitin is performed by UBE2W or UBE2D2, the structural base for polyubiquitination by UBE2N and UBE2V2 (3). For TRIM21-dependent virus proteasomal degradation, VCP activity is required (4), in addition to substrate deubiquitination by Poh1, which can directly activate the innate antiviral response by activating NF-κB (5). After degradation, cytoplasmic virus fragments (6), including genomic dsRNA recognized by MDA-5 and RIG-1, can also activate NF-κB (7). Moreover, nongenomic fragments of the virus can activate inflammasomes such as NLRP3 (8), all of which contribute to the production of type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines. Panel B shows our analysis of E2 ubiquitin enzymes UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2N, and UBE2V2 transcriptional levels. Moreover, Poh1 (PSMD14 gene) and VCP transcription were analyzed in adaptive lymphoid cells from COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms. The artwork was prepared using BioRender.com.

As ILCs composed more than 80% of the cells identified in BALF samples from mild cases, we first analyzed the TRIM21 pathway in this cluster. Multiple required components of the via were not transcribed by any ILC subpopulation, including UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2V2, and PSMD14 (data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that the TRIM21 pathway plays a protective role exerted by ILCs in mild cases of COVID-19. Although TRIM21 was not detected as a prevalent cell population in the BALF samples, we analyzed the TRIM21 pathway in adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells.

Our findings revealed that adaptive lymphoid cells from mild COVID-19 patients had minimal UBE2W transcript levels (Fig. 5B). However, most cells from all populations were positive for UBE2D2 and UBE2N transcription, with a moderate general percentage of UBE2V2-positive cells (Fig. 5B). We also observed that most adaptive lymphoid cells from mild COVID-19 patients transcribed VCP (Fig. 5B). Regarding Poh1, most Treg, CD4+ Th17 cells, and Th1 cells transcribed the PSMD14 gene. In comparison, fewer γδ cells, plasma cells, and Breg cells were positive for this molecule (Fig. 5B).

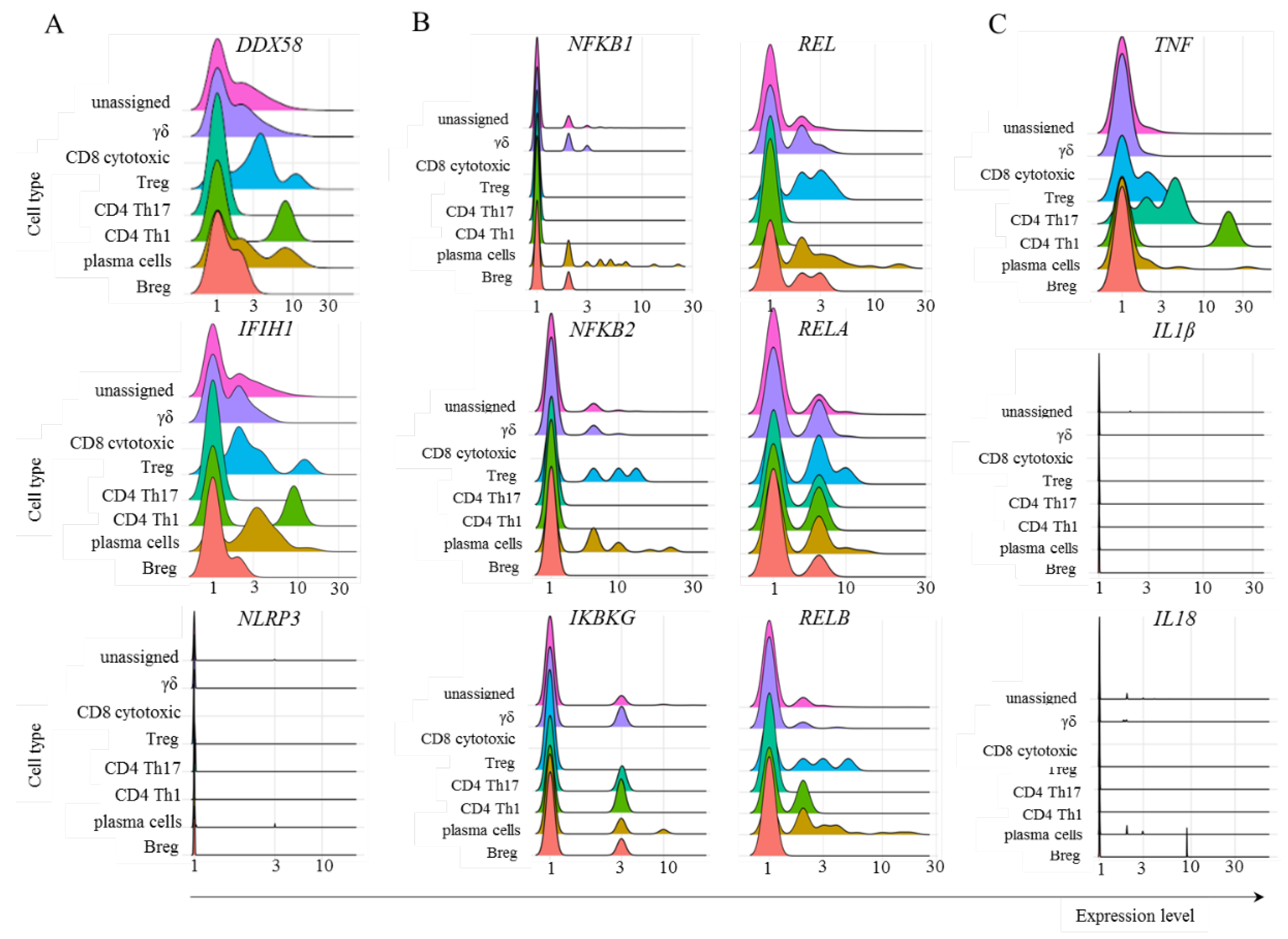

To evaluate the cognate antiviral response mediated by TRIM21, we studied the transcription of some relevant components involved in sensing immunological danger in the cytoplasm. The PRRs RIG-1 (

DDX58) and MDA-5 (

IFIH1) bind to short and long sequences of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), respectively. SARS-CoV-2 is a retrovirus, so these sensors are expected to play a central role in this response. Moreover, multiple nongenomic viral structures generated by proteasomal degradation are potentially recognized by inflammasomes, and the NLRP3 structure is a pivotal component of this family. In the canonical pathway, inflammasomes can bind to diverse damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) or pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) molecules and, through the activation of caspase 1, activate the inflammatory mediators IL-1β and IL-18 [

39]. In the samples obtained from patients with mild symptoms, only CD4

+ Th17 cells did not transcribe

DDX58 or

IFIH1 (Fig. 6A). To our surprise, no adaptive lymphoid population transcribed

NLRP3 (Fig. 6A). Considering the NF-κB pathway, we observed no transcription or few cells transcribed p105 (

NFKB1), p100 (

NFKB2), and

IKBKG (Fig. 6B), whose gene product phosphorylates inhibitors of kappa B kinase (IKK), leading to NF-κB activation. The percentage of cells transcribing c-REL (

REL), p65 (

RELA), and

RELB was variable but generally greater than the percentage of cells transcribing the other components studied of the NF-κB pathway (Fig. 6B). Then, the signature cytokines expected after NF-κB and inflammasome activation are TNF and IL-1β/IL-18, respectively. We observed few Treg cells as TNF

+ (Fig. 6C). Although these cells are associated with IL-10 and TGF-β production, they can secrete TNF under pathogenic conditions [

40]. Moreover, no adaptive lymphoid cells transcribed either

IL1B or

IL18, suggesting that even if the

NLRP3 gene or any other member of the inflammasome sensor family was transcribed, the expected outcome of inflammasome activation would likely not be achieved (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Transcription of some members of the TRIM21-dependent virus innate response. The analysis was performed for the indicated molecules in the populations of adaptive lymphoid cells obtained from mild cases of COVID-19. Panel A represents the transcription of danger sensors, panel B represents some members of the NF-κB pathway, and panel C shows the inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL1B, and IL18.

Figure 6.

Transcription of some members of the TRIM21-dependent virus innate response. The analysis was performed for the indicated molecules in the populations of adaptive lymphoid cells obtained from mild cases of COVID-19. Panel A represents the transcription of danger sensors, panel B represents some members of the NF-κB pathway, and panel C shows the inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL1B, and IL18.

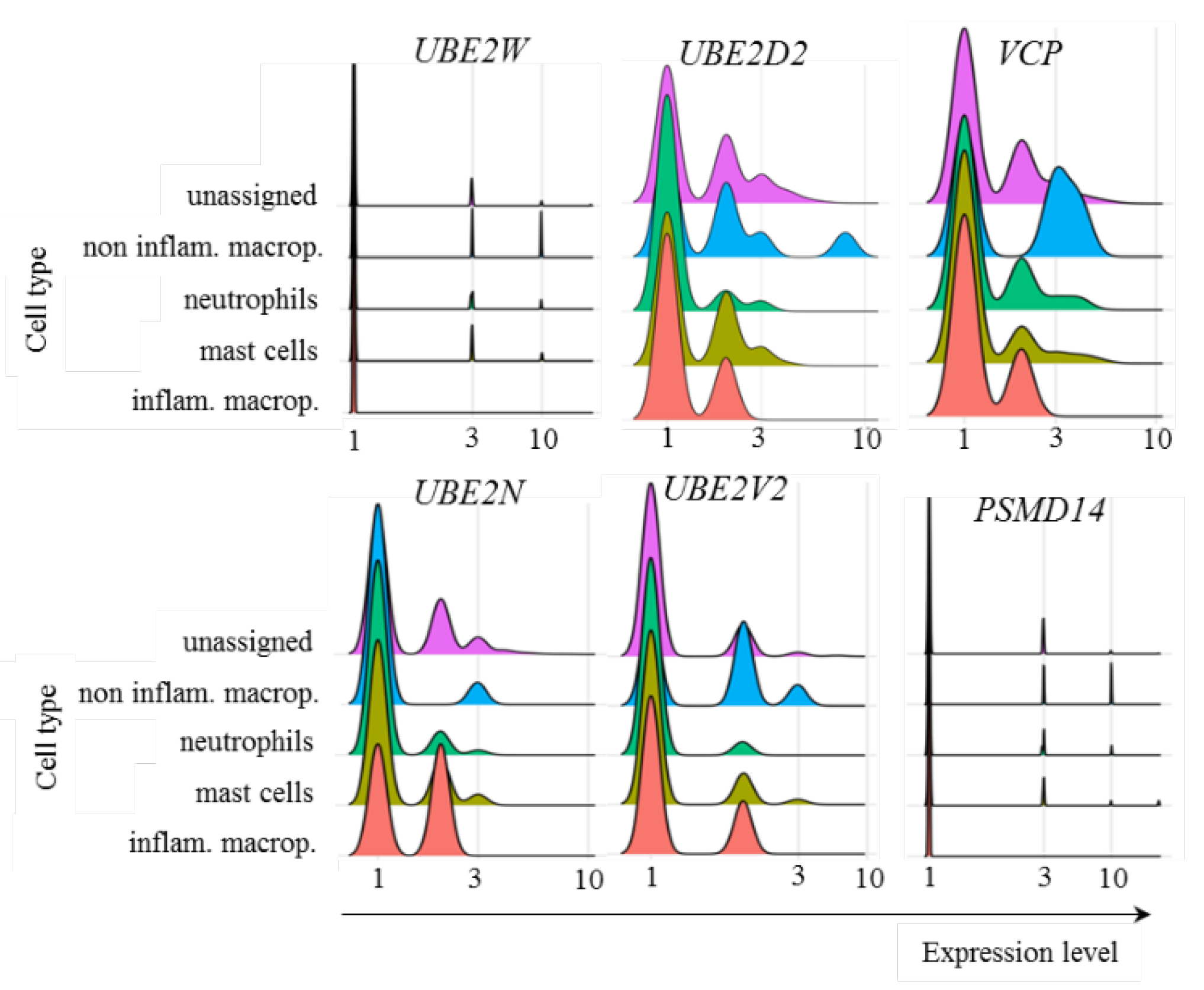

In regards to myeloid cells from patients with mild symptoms, the transcriptional profile of ubiquitin pathway members was similar to that of adaptive lymphoid cells, with no relevant levels of UBE2W transcription and variable levels of UBE2D2, UBE2N, and UBE2V2 (Fig. 7). VCP was also transcribed at different levels by the cell subpopulations (Fig. 7). However, PSMD14 showed no relevant transcription of any population of myeloid cells analyzed (Fig. 7). Presently, it remains unclear whether the absence of Poh1 might obstruct subsequent stages of the pathway or whether alternative deubiquitinases would act to remove conjugated ubiquitin molecules.

Figure 7.

Transcriptional levels of UPS-related genes. The transcriptional levels of the E2 ubiquitin enzymes UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2N, and UBE2V2, in addition to Poh1 (PSMD14 gene) and VCP, were analyzed in the indicated myeloid cells from COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms.

Figure 7.

Transcriptional levels of UPS-related genes. The transcriptional levels of the E2 ubiquitin enzymes UBE2W, UBE2D2, UBE2N, and UBE2V2, in addition to Poh1 (PSMD14 gene) and VCP, were analyzed in the indicated myeloid cells from COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms.

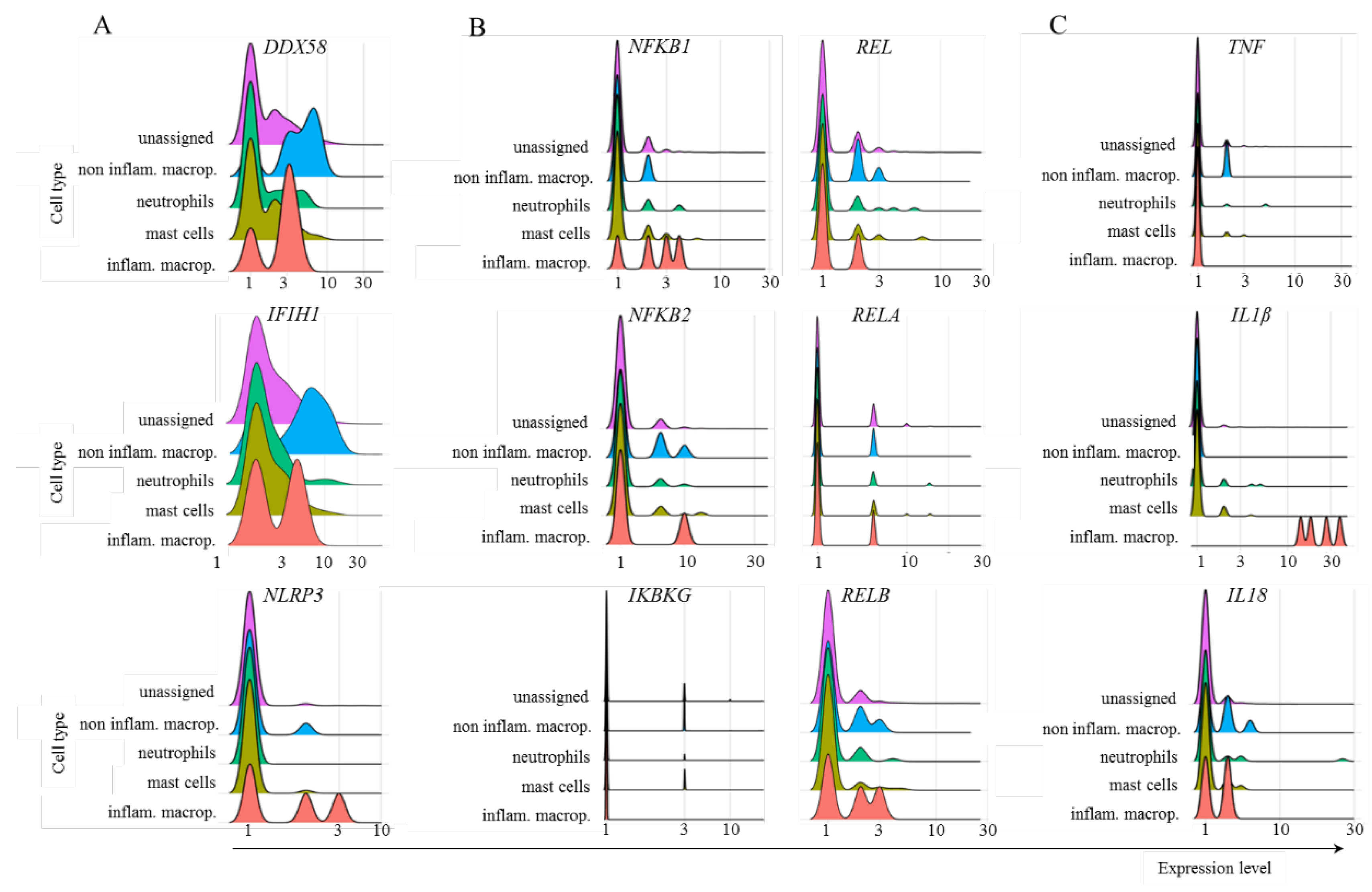

Multiple myeloid cell populations transcribed DDX58 and IFIH1. However, the NLRP3 gene was transcribed only by inflammatory macrophages and, at a lower frequency, by noninflammatory macrophages (Fig. 8). Most inflammatory macrophages transcribed NFKB1, and a few subpopulations transcribed NFKB2, REL, or RELA. Moreover, there was no important transcription of IKBKG in any of the cell populations evaluated, and a fraction of cells transcribed RELB (Fig. 8). Regarding the cytokines, very few noninflammatory macrophages transcribed TNF, all inflammatory macrophages transcribed IL1B, and mostly inflammatory and noninflammatory macrophages transcribed IL18 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Transcription of several members of the TRIM21-dependent virus innate response in myeloid cells. The analysis was performed for the indicated molecules in the populations of myeloid cells obtained from mild cases of COVID-19.

Figure 8.

Transcription of several members of the TRIM21-dependent virus innate response in myeloid cells. The analysis was performed for the indicated molecules in the populations of myeloid cells obtained from mild cases of COVID-19.

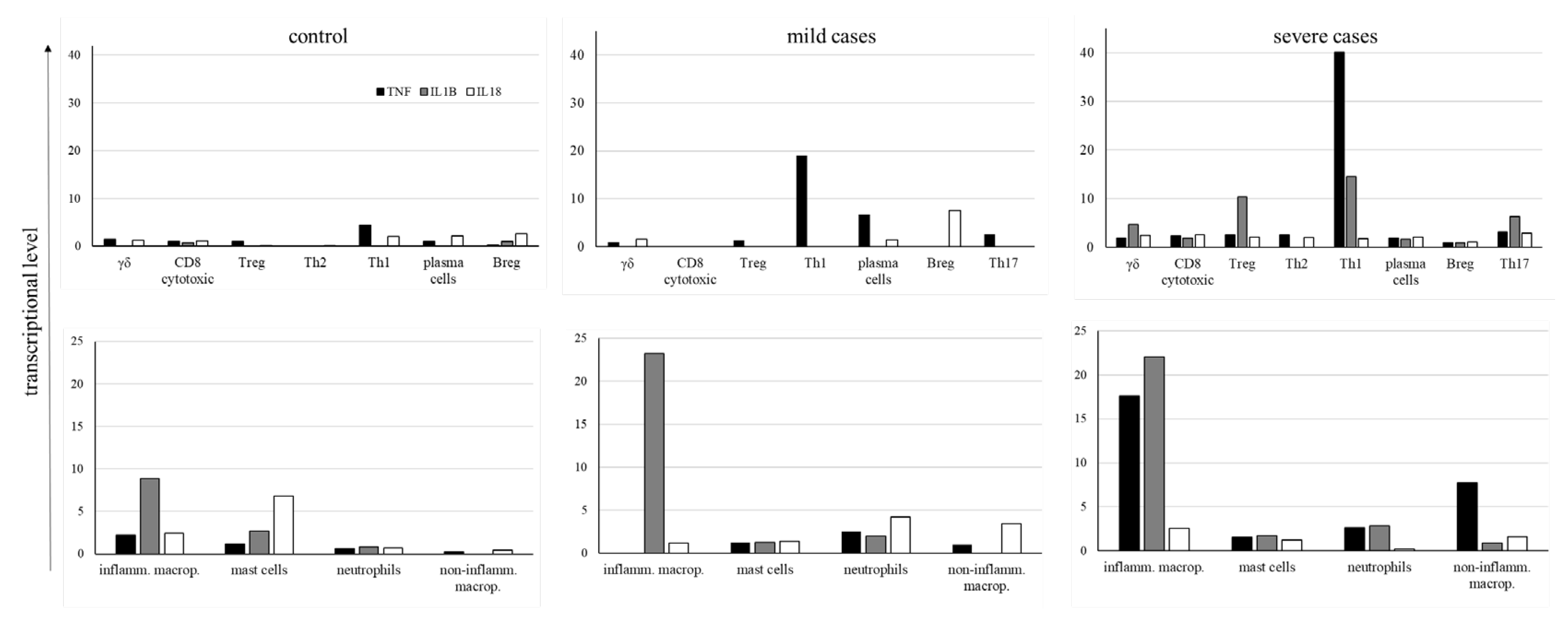

Considering the great importance of TNF, IL-1β, and IL18 in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and to evaluate whether their levels were lower in mild cases than in severe cases, we analyzed their average expression levels in all groups of patients (Fig. 9). In the control group, very low levels of cytokines transcription were observed in adaptive lymphocytes as well as in myeloid cells, although inflammatory macrophages and mast cells had some prominence (Fig. 9). In mild cases, mostly CD4+ Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes transcribed TNF, with Breg cells transcribing IL18. Moreover, inflammatory macrophages primarily transcribed IL1B. As this cytokine must be enzymatically cleaved, we do not know the levels of biologically active IL-1β. On the other hand, in severe cases, comparatively higher levels of TNF were found in CD4+ Th1 cells in addition to inflammatory and noninflammatory macrophages (Fig. 9), with higher levels of IL1B in inflammatory macrophages (Fig. 9). The extended profile of cytokines and chemokines transcribed by adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1, confirming the increased transcription of inflammatory mediators in severe cases.

Figure 9.

Average levels of cytokines transcription. The levels of TNF, IL-1β, and IL-18 cytokines were analyzed in the indicated cell populations obtained from control individuals and COVID-19 patients with mild or severe symptoms. Negative cells were excluded from calculating cytokine average transcriptional levels, and only cells transcribing each cytokine were considered for the calculation.

Figure 9.

Average levels of cytokines transcription. The levels of TNF, IL-1β, and IL-18 cytokines were analyzed in the indicated cell populations obtained from control individuals and COVID-19 patients with mild or severe symptoms. Negative cells were excluded from calculating cytokine average transcriptional levels, and only cells transcribing each cytokine were considered for the calculation.

4. Discussion

A more comprehensive and detailed analysis of FcRs can yield benefits not only for the investigation of SARS-CoV-2 infection but also for multiple diseases whose treatments involve antibody-based immunotherapies, such as cancer [

41], Ebola, cytomegalovirus, influenza, human immunodeficiency, respiratory syncytial viruses [

42], psoriasis [

43], and many others. Our results indicate that multiple cell populations found in the lungs of COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms upregulate the TRIM21 receptor and transcribe its required downstream signaling components dedicated to virus degradation. On the other hand, in severe cases, fewer cell populations transcribed the receptor, mostly with near-zero transcriptional levels. Therefore, we hypothesized that this FcR could contribute to protection against exuberant inflammatory reactions, preventing lung cytokine storm. However, the biological relevance of TRIM21 and FcRn remains to be elucidated in

in vitro functional assays.

Early in the pandemic, risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, kidney disease, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder were recognized as contributing factors to disease severity. However, it later became clear that an excessive and exuberant inflammatory response could contribute more decisively to increased morbidity and mortality rates [

44]. These events ultimately lead to exudative diffuse alveolar damage and end-stage acute respiratory failure. Therefore, understanding the molecular pathways that may contribute to immunoprotection is critical to understanding the pathology.

To illustrate the complexity of the possible roles of FcRs, antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) is a mechanism by which the severity of certain viral infections is increased in the presence of subneutralizing or nonneutralizing antiviral antibodies.

In vitro assays of ADE associate this enhanced pathogenesis with abnormal FcγR-mediated viral host cell invasion, which overlaps with the conventional function of FcγRs in mediating protection [

45]. The presence of membrane-bound FcRs in non-COVID-19 patients might be related to pathology, at least in some acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) patients [

46]. In this case, critically ill patients who eventually died of SARS had accumulated pulmonary proinflammatory mediators, no wound-healing macrophages, and faster neutralizing antibody responses. Serum from these patients enhanced

in vitro SARS-CoV-induced CCL2 chemokine and IL-8 production by human monocyte-derived wound-healing macrophages. In this case, this effect was reduced after FcγR blockade [

47]. Therefore, screening for the biological functions of FcRs and their potential roles in the protection or pathogenesis of infections is central.

Our findings were derived from the analysis of sc-RNAseq data, an important method for screening cellular transcriptional profiles. This method enables the assessment of phenotypic modulations and potential biochemical pathways that may play a role in various biological processes. However, confirming the biological relevance of these hypotheses in vitro and in vivo is necessary. Our analysis focused on patients with mild symptoms, the group with the most consistent transcriptional upregulation of TRIM21 and downstream components, who were more likely to benefit from the antiviral activity of this pathway. However, our analysis included a limited sample size of only three patients with mild symptoms, accounting for a total of 2,486 cells. Multiple reasons led to this reduced sampling. The lung cells were obtained by BAL, an invasive procedure usually not clinically indicated for patients with no severe symptoms. Moreover, multiple parameters must be evaluated and considered when analyzing different datasets available in public repositories. These include the clinical characteristics used for patient categorization with mild or severe symptoms, clinical procedures to collect the samples, postcollection computational processing, data compatibility to run by CellHeap, available datasets containing BALF samples from the three groups of patients, and others. These facts were determinant to having just this dataset of patients with mild disease analyzed. As more datasets are available with samples from only severe patients, we analyzed another dataset containing only this group (data not shown). This additional dataset comprised approximately 40,000 cells from twenty-two patients, and we observed similar intracellular FcR profiles to our results for severe patients.

The number of immune cells in the lungs of normal individuals was calculated to be in the range of 7x10

10 cells [

48]. We do not know the number of total cells in the lungs of patients with mild COVID-19, but this number is possibly greater than that in healthy individuals. In regards to the BAL procedure for cell collection, it probably harvests cells with weaker interstitial adherence, and in our analysis, we excluded virus-infected and dead cells, all likely altered the proportion of cell populations found in the lungs. Therefore, reaching an approximate number of lung cells from mild COVID-19 patients who could express TRIM21 and the required components of the pathway would be speculative. However, as an exercise, we observed that 32% of all cells analyzed in mild cases, from the three patients transcribed the

TRIM21 gene, and part of these cells had the downstream components. If as few as 10% of the cells were equipped with all receptor signaling components, and considering the total number of cells in normal lungs as a reference, we would find at least 2,3x10

9 cells per individual who could respond to the infection through TRIM21.

Regarding cellular identification, there is no consensus on the repertoire of genes sufficient to discern individual subpopulations. For mast cells, for example, Liao et al. [

21] used the

TPSB2 gene, while Wauters et al. used the genes

MS4A2,

TPSAB1, and

TPSB2 [

30]. We used both possibilities to identify this population, and the resulting number of cells and transcriptional levels of some selected genes were very different. Moreover, there was no transcription of

FCER1A in either analysis, a signature gene for mast cells. Therefore, in this work, we used the well-known repertoire of membrane FcRs expressed by each cell population in the group of healthy control patients as an internal reference for data curation. In the case of mast cells, for example, the combination of genes used here identified cells that transcribed

FCER1A, and the same was done for all populations.

The pulmonary landscape of cellular subpopulations of the immune system and their regulated functions are central to the clinical outcome of COVID-19, as populations generally associated with a protective role in viral infections may turn into pathogenic cells. Many aspects related to the abnormal activation of inflammatory pathways in the lungs of severe patients remain to be clarified to avoid inflammatory secondary damage and worsened symptoms. For example, in severe cases, a significantly greater percentage of CD4

+ T lymphocytes producing IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 and of CD8

+ T lymphocytes producing IFN-γ, TNF, and exposed CD107a were observed compared with those in the corresponding mild group [

49]. Increasing evidence indicates that Th17 lymphocytes contribute to severe lung pathology and mortality [

50], and increased Th2 cytokines are observed in patients with fatal infection [

47]. Moreover, virus-specific T lymphocytes obtained from patients with severe COVID-19 tended to have a greater frequency of the central memory phenotype (CD27

+/CD45RO

+). On the other hand, the cytolytic activity of NK cells is associated with SARS-CoV-2 clearance and disease control [

51]. Plasma cells are also essential for a protective immune response against COVID-19, with strong T lymphocyte responses correlated with increased neutralizing antibodies. Myeloid cells are also pivotal for disease control, and abnormal cells are associated with the death of patients with severe COVID-19. These cells are associated with damage in multiple organs induced by the secretion of high amounts of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and abnormal coagulation [

52]. In general, very high levels of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

53] and IFN-γ [

54] are also critical to the pathophysiology of the disease and the development of severe symptoms. Therefore, we focused on analyzing most of these cell populations.

This work evaluated multiple cell subpopulations based on previously described cells involved in either COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or disease control [

21,

55,

56]. However, as our work focused on potentially protective intracellular FcRs, we aimed to include the regulatory lymphocyte populations of Breg and Treg cells. Breg cells have not been extensively investigated in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but it was previously reported that these cells are important for protecting the lungs from respiratory diseases [

57]. Moreover, Treg cells were reported to be a protective cell population in COVID-19 patients, with fewer Treg cells in the blood being associated with poor prognosis and an increased likelihood of long-term lung disease [

58].

We found that more than 80% of the lung cells obtained from patients with mild COVID-19 were ILCs, with a balanced frequency of ILC3 NCR-, ILC1 cytotoxic, LTi, and NK cells. This would be compatible with the primarily reduced number of these cells observed in blood from COVID-19 patients, which could suggest the migration of ILCs to primary virus-affected target tissues such as the lungs [

35]. However, to the best of our knowledge, pulmonary enrichment of ILCs has not been previously observed in patients with mild COVID-19. Unlike T and B cells, ILCs are innate lymphocytes that do not rearrange antigen receptors or express cell surface markers associated with other lymphoid or myeloid cell subpopulations. There are five major groups of ILCs, which are NK, ILC1, ILC2, ILC3, and LTi cells, with ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s roughly mirroring CD4

+ Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells, respectively. NK cells, in turn, reflect the functions of CD8

+ cytotoxic T cells [

59]. Although ILC2s were shown to be protective against pneumonia recovery after COVID-19 [

34], this population was not found in our samples from mild cases.

In summary, we observed several molecular features that might contribute to controlling lung infection and disease severity, preventing it from escalating to an uncontrollable immune-mediated pathogenic response. We observed evidence of the relevance of TRIM21-mediated degradation of SARS-CoV-2 by the UPS, considering the receptor itself and the downstream required components observed in adaptive lymphoid and myeloid cells from mild samples. Moreover, although this pathway can provide PAMP fragments recognized by multiple PRRs involved in the antiviral inflammatory response, this pathway branch does not seem critically active in these cells. Therefore, other pathways likely act in parallel with TRIM21 to downregulate or impair the transcription of the inflammatory components NLRP3, IL1B, and IL18 in most cell types studied, including no transcription in any ILC population (data not shown). Moreover, essential members of the NF-κB inflammatory pathway, another critical player in the TRIM21 inflammatory pathway, were transcribed at low levels, which is consistent with the low levels of TNF found in mild cases. Taken together, our data suggest the participation of TRIM21 in the refined pathophysiology of COVID-19, possibly having a protective role through the degradation of the virus but leading to no robust inflammation in the lungs.