1. Introduction

Five years after Coronavirus Infectious Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), SARS-CoV-2 remains as one of the most prevalent respiratory infections worldwide, with greater morbidity and mortality than other respiratory viruses that have been circulating for decades[

1]. During the early phase of the pandemic, convalescent plasma therapy was successfully administered, particularly to patients who responded poorly to antiviral treatments. However, the emergence of new subvariants has increasingly undermined the effectiveness of antibody-based therapies, reducing their ability to prevent severe disease outcomes [

2].

Despite the current interventions for SARS-CoV-2 infection including vaccines, antiviral drugs, monoclonal antibodies, corticosteroids, and other pharmacological agents, the high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 drives continuous evolution of its genome, with new mutations emerging, particularly in immune-relevant regions such as S-protein [

3,

4]. Specifically in the S-protein, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the N-terminal domain (NTD) are key regions where mutations highly affect the effectiveness of neutralizing antibodies [

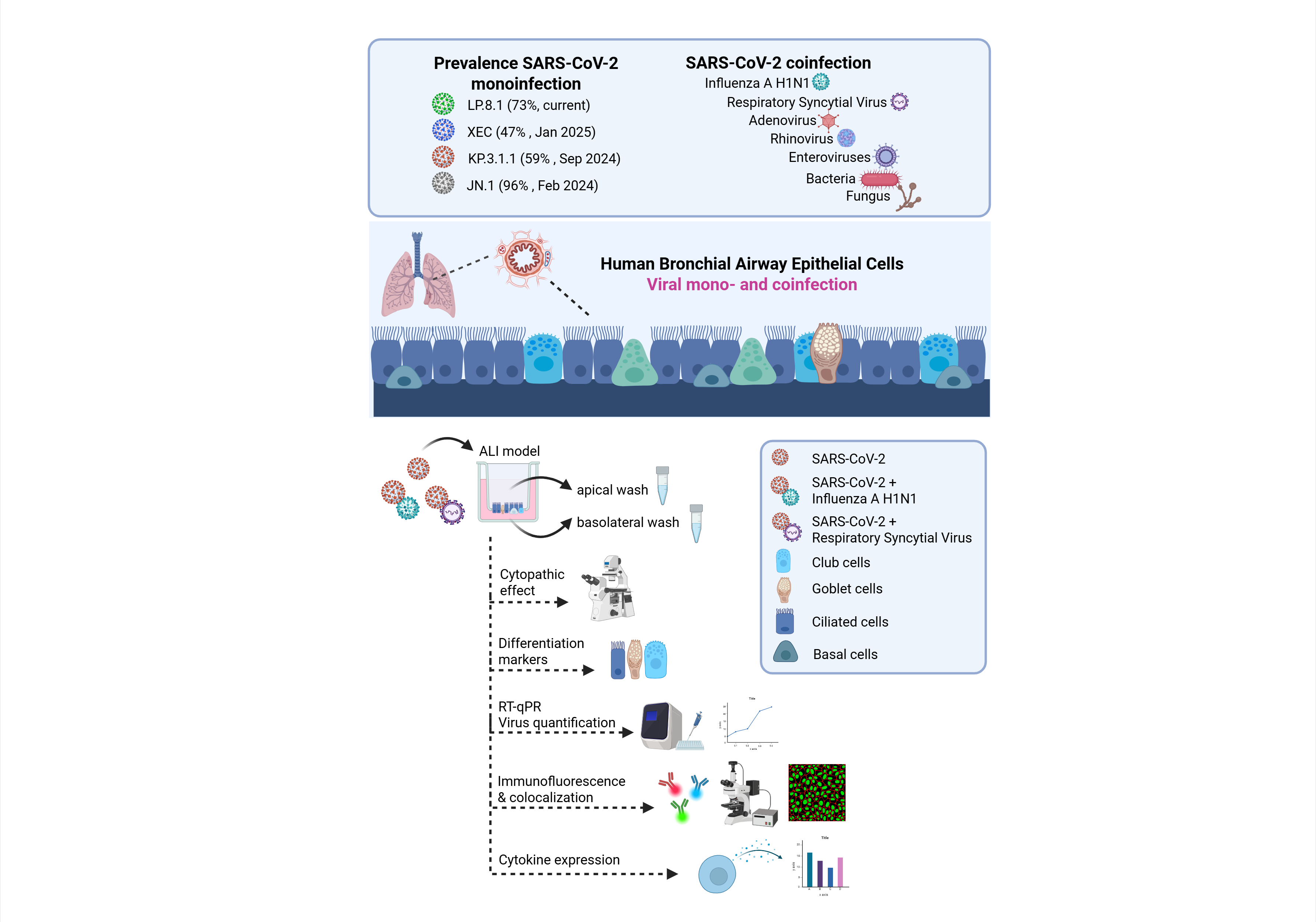

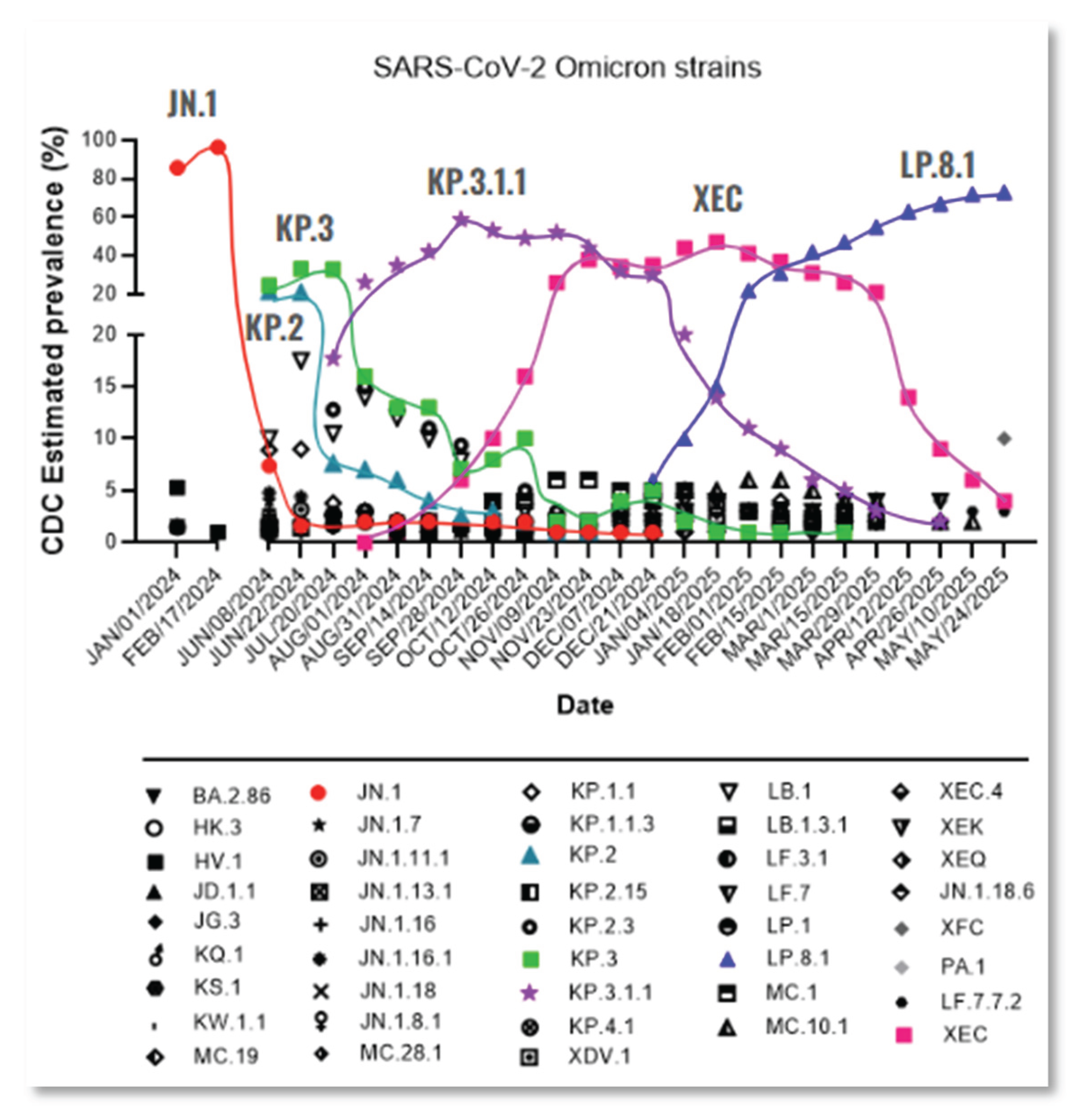

5]. Since the onset of the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 has rapidly evolved into multiple variants, with Omicron serving as the parent lineage for nearly all currently circulating subvariants. A comprehensive view of the evolutionary landscape of SARS-CoV-2 since the emergence of Omicron JN.1 is shown in

Figure 1.

Besides this, SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating in association with other respiratory viruses, but the prevalence of these coinfections has been underestimated due to the global focus being primarily directed toward SARS-CoV-2. Currently, SARS-CoV-2 coinfections with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV are increasingly recognized [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], but further studies are needed to better understand the extent of lung tissue damage caused by these coinfections and their implications for host immunity.

Here, we monitored the prevalence of emerging SARS-CoV-2 subvariants across the United States to identify key spike mutations in strains driving the recent waves of infection and evaluate their infection phenotypes. We assessed the efficacy of commercially available monoclonal antibodies and HCoP samples against a panel of recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 strains, including clinical isolates obtained within New Jersey. Several recent studies have evaluated SARS-CoV-2 infection in human airway epithelial cells, both as a monoinfection and in combination with other respiratory viruses [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, there is currently no available characterization of infections caused by the most recent Omicron subvariants, nor are there reports on coinfections involving these strains and other respiratory viruses in human bronchial cells.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of viral infection by the recent Omicron subvariants JN.1 and KP.3.1.1 in the bronchial region of the respiratory system using hBAECs. It is also the first report to investigate coinfection of Omicron KP.3.1.1 with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV, using hBAECs in an air-liquid interface (ALI) model. Our findings offer new insights into the pathogenicity and immune evasion mechanisms of recent Omicron subvariants and their interactions with other respiratory viruses, with important implications for public health preparedness and the development of therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

African green monkey kidney cells (VeroE6/TMPRSS2) were obtained from XenoTech, Japan (Cat. No. JCRB1819, Lot No. 2222020). Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells were purchased from the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources repository (BEI Resources, USA, Cat. No. NR-2628, Lot No. 494646-2). Both VeroE6/TMPRSS2 and MDCK cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, ATCC Cat. No. 30-2002TM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thomas Scientific, Cat. No. C788U22) and 1% antibiotic / antimycotic (A/A) (ThermoFisher Cat. No. 15240062). Human cervix epithelial cells (Hep-2) were purchased from Sigma (Cat. No. 86030501-1VL, Lot. No. 16K049), and maintained in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, ATCC Cat. No. 30-2003TM), supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A. All cell lines were cultured as monolayers at 37°C with 5% CO2 and appropriate humidity, and sub-cultured at regular intervals to maintain their exponential growth using recommended split ratios and medium replenishment volumes.

2.2. Viral Infections, Cytopathic Effect and Stock Preparation

2.2.1. SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 virus strains were obtained from BEI Resources and through the Hackensack Meridian Health BioRepository (HMH-BioR). All HMH-BioR strains were recovered from nasopharyngeal swabs collected by the New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH) surveillance program for COVID-19 and were confirmed as SARS-CoV-2 by whole-genome sequencing performed at the New York Genome Center. In this study, the WA1/2020 strain was used as the reference for SARS-CoV-2, as it was isolated from the oropharyngeal swab of a patient who returned from an affected region in China and later developed clinical disease (COVID-19) on January 19th of 2020, in Washington, USA. The source of each individual strain is listed in

Table S1. For virus propagation, 2x10^6 VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were seeded in a T25 flask one day prior to infection under the conditions described previously. Once the cells formed a confluent monolayer, the media was removed, and 100 µL of the virus inoculum was added to the flask allowing the infection for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the flask was replenished with fresh and warmed DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A.

2.2.2. Influenza A H1N1

Influenza A virus-A/WSN/33 (H1N1) PA-2A-Nluc (PASTN) (abbreviated here as IFAV_H1N1) was obtained from BEI Resources (Cat. No. NR-49383, Lot. No. 70037384). For virus propagation, 1.5x10^6 MDCK cells were seeded in a T25 flask with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A. After 24 h, the cell growth medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with virus propagation medium EMEM supplemented with 0.125% bovine serum albumin (BSA, ThermoFisher, Cat. No. 15260037) and 2 µg/mL TPCK-treated trypsin from bovine pancreas (TPCK-treated trypsin, Sigma, Cat. No. T1426). The cells were then infected with 100 µL of the virus inoculum and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Following the incubation, the flask was replenished with the virus propagation medium.

2.2.3. Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Recombinant Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) A2 Expressing Green Fluorescent Protein, rgRSV224 (abbreviated here as RSV) was obtained from BEI Resources (Cat. No. NR-52018, Lot. No. 70059814). For virus propagation, Hep2 cells were cultured in a T25 flask using an EMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A. Infection was carried out with 100 µL of the virus inoculum in 2 ml of EMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and 1% A/A, followed by 2 h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. After the incubation, the flask was replenished with EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A.

All viruses were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cytopathic effect (CPE) was monitored daily at 4x and 10x magnification using a phase contrast microscope (EVOS XL Core Imaging System, Cat. No. AMEX1000). Virus stocks were prepared by collecting the supernatants when 70%-80% CPE was observed. The cell debris was clarified by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 5 mins, and 500 µL of the supernatants were transferred into screw-cap tubes and stored at -80°C until further use.

2.3. Plaque Forming Unit Assay (PFU)

Virus titration was performed based on a method previously published [

17], with some modifications. For SARS-CoV-2, VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2.5x10^5 cells in 500 µL per well and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. Ten-fold serial dilutions of the virus stock were prepared in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% A/A. The cell monolayer was rinsed with the same medium, and 100 µL of the virus dilutions were added to the corresponding wells. The infection was allowed for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, with gentle rocking of the plates every 15 minutes. After 1 h, 500 µL of a pre-warmed overlay mixture (2x MEM with 2.5% Cellulose, 1:1) were added per well, and plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Finally, plates were fixed with 500 µL of 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for 24 h and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (CV).

For IFAV_H1N1, MDCK cells in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% A/A were seeded in a 24-well plate at the concentration of 2.5x10^5 cells / well, followed by overnight incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. Viral dilutions were prepared in EMEM with 0.125% BSA and 2ug/mL TPCK-treated trypsin. Cells were inoculated with 100 ul of each dilution, incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, followed by the addition of overlay media containing 2% low melting point agarose (Lonza, Cat. No. 50100) in virus propagation medium (1:1). Finally, cells were fixed with 10% NBF at 4 days post-infection during 24 h, and stained in 0.5% CV.

For RSV, 2.5x10^5 Hep2 cells in EMEM with 10% FBS and 1% A/A were used for seeding and viral dilutions were prepared in EMEM with 2% FBS and 1% A/A. The incubation with the virus was extended to 2 h followed by an addition of an overlay containing 0.3% agarose in EMEM with 10% FBS and 1% A/A. Plates were then incubated for 6 days, and the staining was performed using 0.05% neutral red for 1 h. For all viruses, viral plaques were counted visually, and the virus titer was determined as PFU/ml.

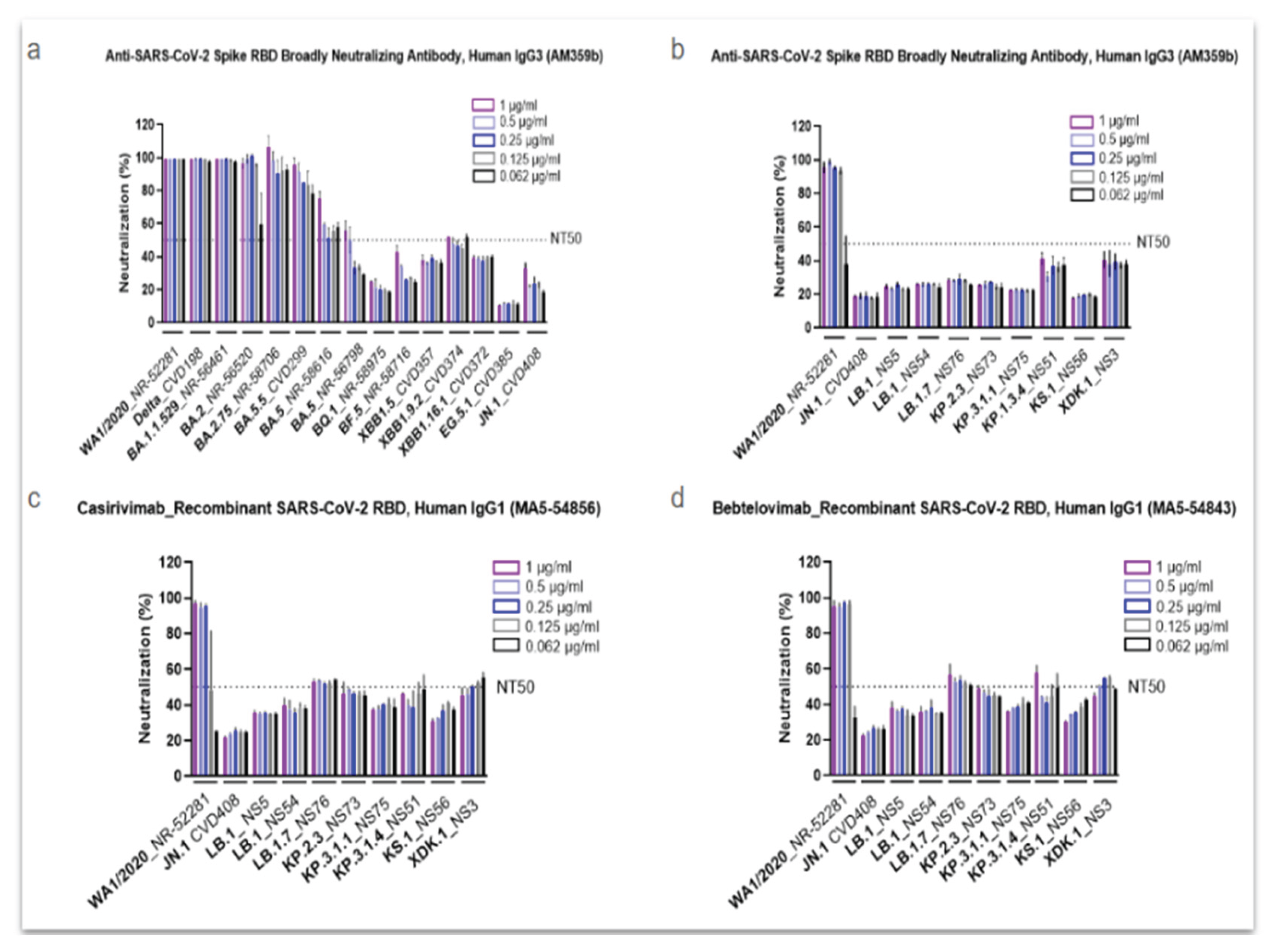

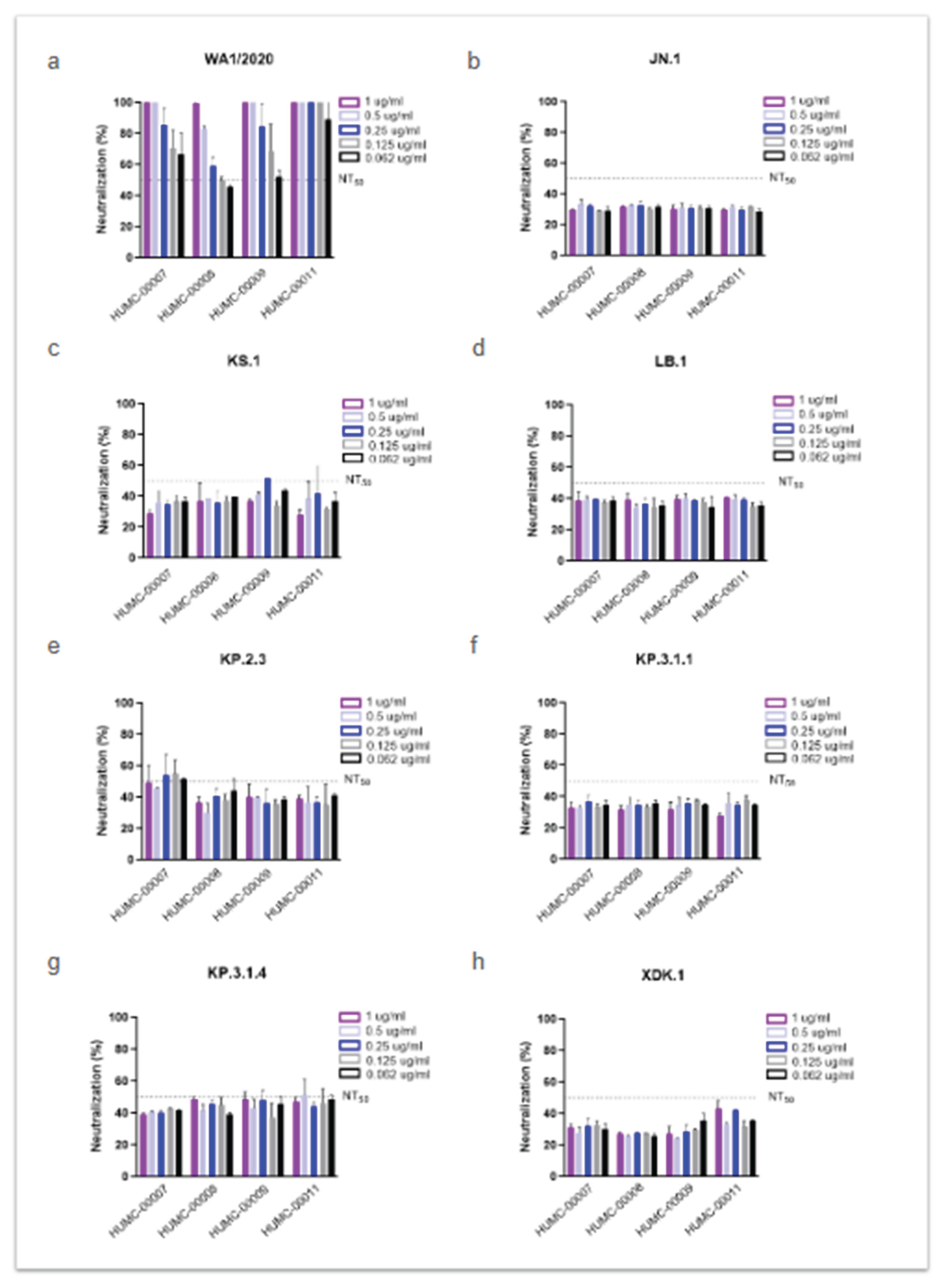

2.4. Antibodies and Human Convalescent Plasma

Three commercially available antibodies were purchased from different sources: 1) Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domain Broadly Neutralizing Antibody, Human IgG3 (AM359b) (Acro Biosystems, Cat. No. SPD-M400a); 2) Casirivimab Recombinant Human Monoclonal Antibody, SARS-CoV-2 RBD, IgG1 (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. MA5-54856); 3) Bebtelovimab Humanized Recombinant Human Monoclonal Antibody, SARS-CoV-2 RBD, IgG1 (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. MA5-54843). The antibody stocks concentrations were as follows: Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD (1 mg), Casirivimab (1.7 mg/mL), and Bebtelovimab (1.1 mg/mL). Additionally, HCoP samples (HUMC00007, HUMC00008, HUMC00009, and HUMC00011) were obtained from clinical specimens through the HMH-BioR, with 1,000-10,000 IgG titers against the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein. These samples were isolated from NJ patients that were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in 2020, and without receiving COVID-19 vaccination (HMH IRB. No. Pro2018-1022).

2.5. Neutralization Assay

Neutralization assays were performed as previously described [

18], with minor adaptations. Briefly, VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were seeded 24 h prior to the assay in 96-well plates at a density of 1x10^4 cells in 100 µL per well, followed by overnight incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. In a separate plate, two-fold serial dilutions of antibodies and HCoP samples were prepared in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A, to obtain the following final concentrations: 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125 and 0.062 µg/mL. An equal volume of SARS-CoV-2 virus was added to each dilution at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, and the antibody / plasma-virus mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After this incubation, the media from the cell-containing plates was removed and replaced with 100 µL of the antibody / plasma-virus mixture, allowing interaction with the cells for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 and with gentle plate rotation every 15 mins to ensure even distribution of the mixture. After this time, the antibody / plasma-virus mixture was removed, each well was replenished with 100 µL of fresh DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% A/A medium, and plates were incubated for 72 h following the same conditions. The CPE was monitored daily, and on day 3 post-infection, 100 µL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, Cat. No. G9241) were added per well. Neutralization titers at 50% (NT

50) were calculated after data normalization to the control cells without antibody / plasma.

2.6. Spike Protein Target-Based Sequencing

RNA extraction was performed using a QiaCube HT instrument (QIAGEN Cat. No. 9001896.), with QIAGEN 96-well format Cat. No. 9001896) and RNA extraction kit “QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT Kit” (QIAGEN Cat. No. 57731), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were lysed under highly denaturing conditions at room temperature (RT) in the presence of proteinase K and lysis buffer ACL, which together ensure the inactivation of nucleases. Buffer ACB was then added to adjust the binding conditions for RNA purification. The lysate was transferred to a QIAamp 96 plate, and nucleic acids were adsorbed onto the silica membranes under vacuum while contaminants passed through. Three wash steps effectively removed the remaining contaminants and enzyme inhibitors, and the RNA was eluted in buffer AVE. For cDNA synthesis, a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Cat. No. RR 047A) was used. The process was carried out in two steps: genomic DNA (gDNA) was eliminated using the gDNA Eraser at 42°C, followed by reverse transcription with the PrimeScript RT Mix I at 37°C.

To identify gene modifications in the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2, the full coding sequence of the open reading frame 2 (ORF2) gene was amplified and sequenced. PCR amplification was performed using the Takara® PrimeSTAR HS Kit (Takara Bio, USA, Inc., Cat. No. R010B) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the primers listed in Table S1. The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation cycle at 98°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles consisting of 15 sec of annealing at 54°C, a 2-min and 10-sec elongation at 72°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. PCR products were verified by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequently sent for Sanger sequencing to Genewiz® (South Plainfield, NJ, USA) using the same primers. The resulting sequences were analyzed using Seqman Pro version 17.5.0 (Lasergene DNAStar® software).

2.7. Ex-Vivo Air-Liquid Interface Model (ALI)

2.7.1. Human Bronchial Airway Epithelial Cells (hBAEC)

Sterile hBAEC were purchased from Epithelix (Geneva, Switzerland, Cat. No. EP51AB, Batch No. 02AB0940), after being isolated from a 62-year-old female donor, with non-smoking record and no reported pathology, and cryopreserved as passage 1 in October of 2022. Cells were cultivated in PneumaCult™ ExPlus Expansion Media (StemCell Cat. No. 05040) supplemented with 0.1% hydrocortisone (Stemcell Cat. No. 07925) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 3 days, the cells were washed with D-PBS (without Ca++ and Mg++) (Sigma Cat. No. D8537), and the detachment was achieved after using ACF Enzymatic Dissociation Solution for 7 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of ACF Enzyme Inhibition Solution used to neutralize the reaction (StemCell Cat. No. 05426). The cell suspension was centrifuged for 5 min at 360 g, and the pellet was resuspended in PneumaCult™Ex Plus Medium. Cells were then expanded into 24-well plates using transwell collagen-coated inserts (Corning Cat. No. 3495), with a polyester (PET) membrane of 0.4 uM pore size and a surface area of 0.33 cm². Each insert was seeded with a density of 3.3x10^4 cells in 200 µL of PneumaCult™-ExPlus Medium. Once 70%-80% confluence was reached, the cells were airlifted, with replacement of the basolateral medium every 2-3 days using PneumaCult™-ALI Maintenance Medium supplemented with 0.2% heparin (Stemcell Cat. No. 07980) and 0.5% hydrocortisone (StemCell Cat. No. 07925). The differentiation of the epithelium was monitored using a phase contrast microscope (EVOS XL Core Imaging System, Cat. No. AMEX1000).

2.7.2. Monoinfection and Coinfection Assays in Human Bronchial Airway Epithelial Cells

After 23-28 days of maturation, including mucus production and cilia beating, two independent hBAEC inserts were used to evaluate the effect of monoinfections (WA1/2020, JN.1 and KP.3.1.1) and coinfections (KP.31.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.31.1+ RSV). The apical surface of hBAEC was inoculated with 2x10^5 PFU/ml per insert of each corresponding virus in 200 µL of PneumaCult™-ALI Basal Medium. For coinfections, 2x10^5 PFU/ml of each virus strain were mixed and 200 uL from the mixture was used for infection. Plates were incubated for 2 h at 35°C with 5% CO2 to allow virus internalization. After incubation, the virus inoculum was collected and evaluated by PFU assay to determine the effectiveness of hBEAC infection. Additional apical washes were performed to eliminate the unbound virus, with the last wash being collected and used as the day-zero sample. Subsequently, plates were returned to the incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and CPE was monitored every 24 h, with collection of apical and basolateral washed in each time point. Mock cells were incubated with the growth culture medium during the infection step. All apical and basolateral samples from each time point were stored at -80°C and ALI cultured cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (w/v) (ThermoFisher Cat. No. J61899.AP) in both apical and basolateral chambers and conserved at 4°C until further processing.

2.7.3. Viral Quantification by Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR)

Apical and basolateral samples were inactivated with proteinase K (1:10 ratio) for 1 h at 65°C. Viral RNA was isolated from the samples, using the Qiagen QIAcube HT (Germantow, MD, USA) automated mid-to-high-throughput nucleic acid purification instrument with the QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT Kit (Cat. No. 57731). For SARS-CoV-2, RT-qPCR was performed using the E gene primer, probe panel, and RNase P gene as described before [

19]. For IFAV_H1N1, primers and probes or iTaq Universal SYBR Green One-Step Kit (Bio-Rad Cat. No. 172-5151) targeting the haemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA) and matrix (M) genes were used, using the sequences included in the WHO report of 2021 [

20]. For RSV, F and N proteins were amplified using primers and probes described in the literature [

21]. All the sequences related to the three viruses are listed in

Table S2. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was calculated using the standard error (SE) and standard deviation (SD) of the intercept from the standard curves of the RT-qPCR, and it was determined as 1 log of quantity of copies for this assay.

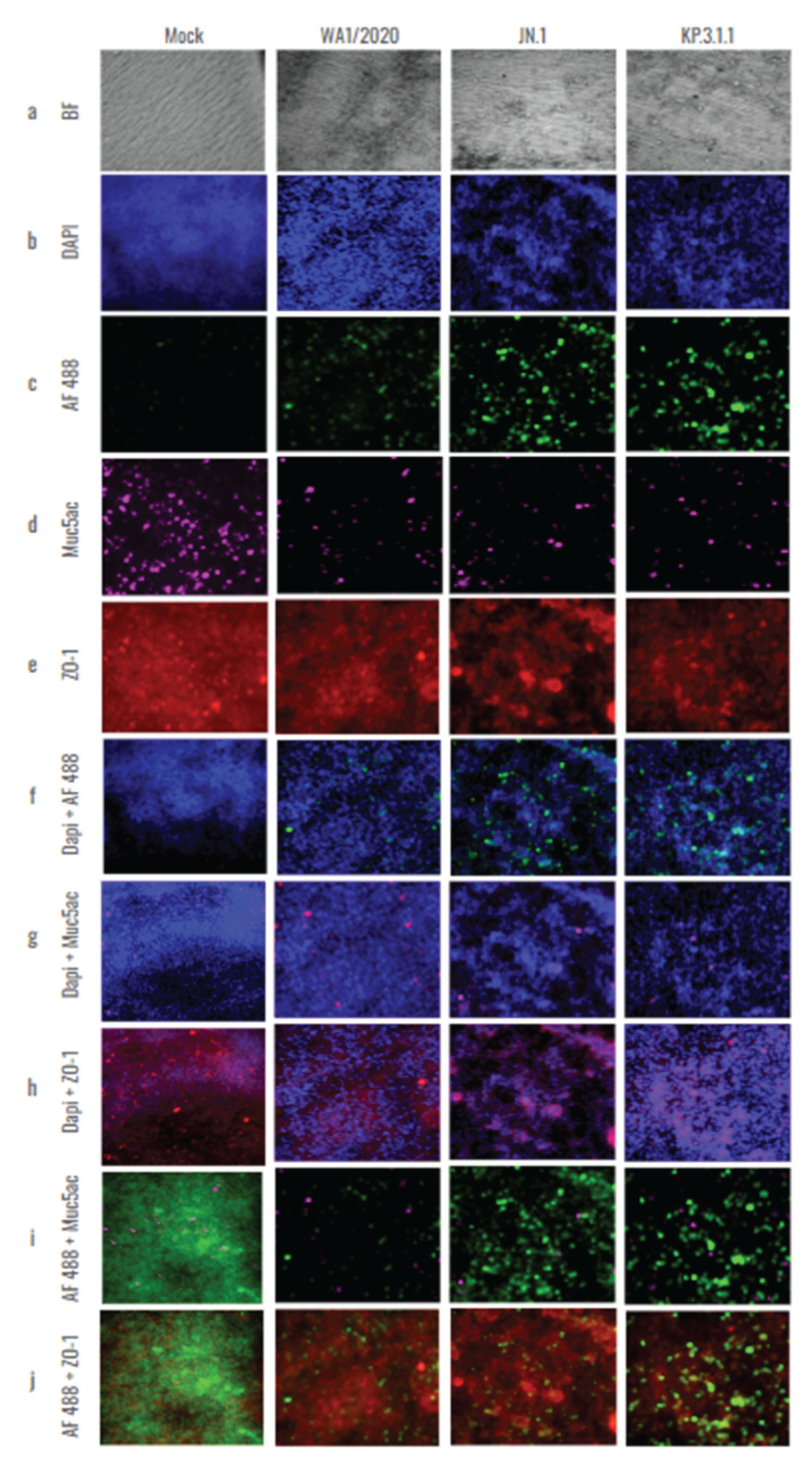

2.7.4. hBAEC Differentiation and Colocalization Evaluated by Immunofluorescence Assay

The differentiation of the hBAEC epithelium was assessed using fluorescence microscopy and specific differentiation markers. Three of 1X PBS washes were applied to the fixed cells, followed by blocking and permeabilization steps with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma Aldrich Cat. No. A7906) and 0.03% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich Cat. No. X100-5ML) for 30 min at RT. Immunofluorescence staining was performed for the following cell markers diluted in blocking buffer: tight junction protein, ZO1 (1:100 dilution, mouse monoclonal, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate; ThermoFisher, Cat. No. MA3-39100-A555) and goblet cell marker, Muc5ac (1:100 dilution, mouse monoclonal, Alexa Fluor® 647 conjugate; Abcam, Cat. No. ab309611). After the addition of each antibody conjugate, cells were incubated at RT with gentle agitation and washed three times using 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS. For the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid staining, blocked and permeabilized cells were incubated with the primary antibody (anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody, 1:10,000 dilution; BioLegend, Cat. No. A20087F) diluted in 2% BSA + 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS, incubated at 4°C overnight with gentle agitation and followed by three washes with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS. The secondary antibody conjugate (goat polyclonal, Alexa Fluor™ 488, ThermoFisher, Cat. No. A-11001) was added at 1:20,000, diluted in 5% BSA + 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS, for 1 h at RT. Cells were finally washed three times with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS, counter-stained with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; ThermoFisher Cat. No. 62249), and visualized with acquisition of images at 10x, using Nikon Ti2 Epi-fluorescence microscope and NIS Elements imaging software (Version 5.30.06).

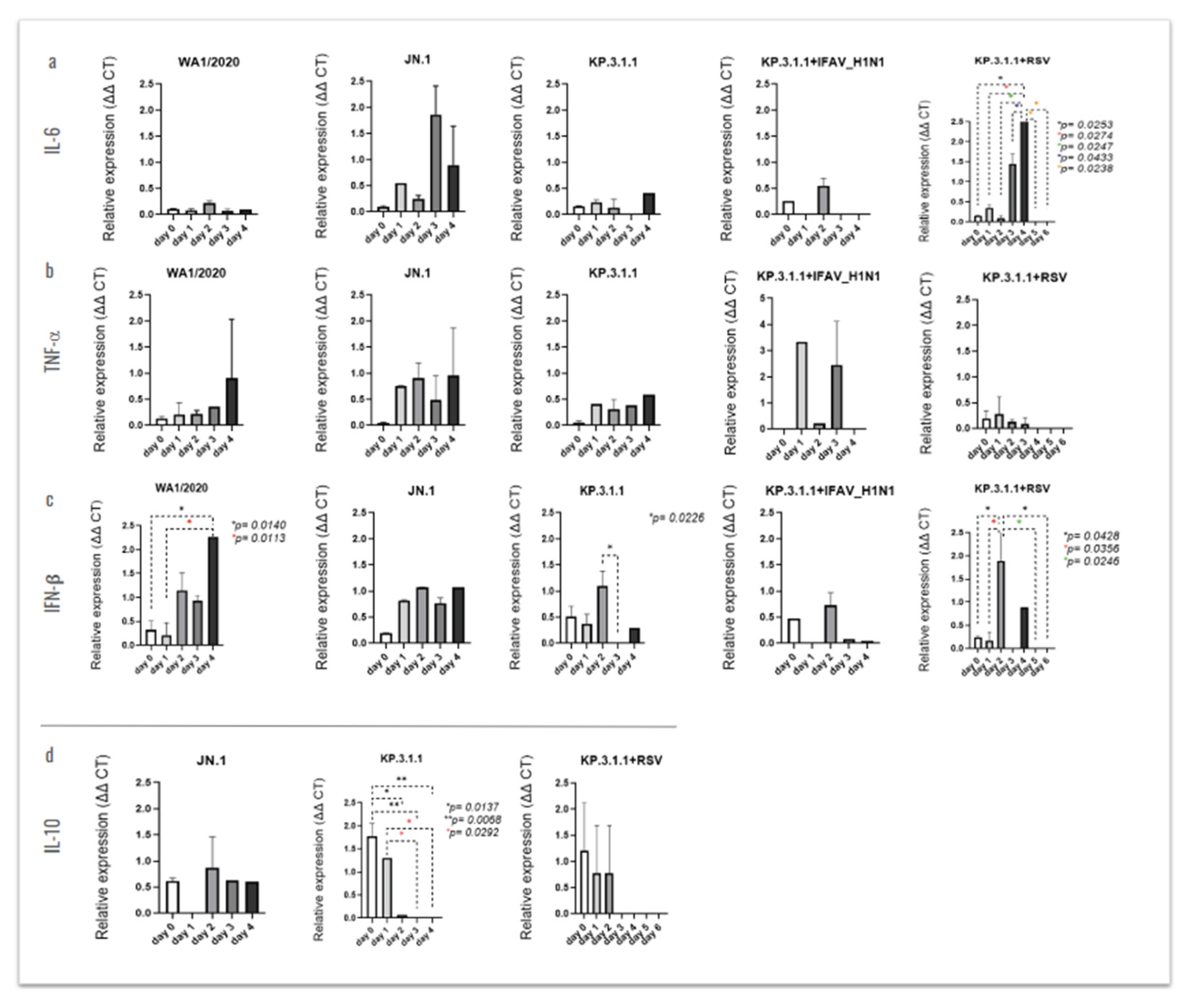

2.7.5. Profile of Cytokine Expression in hBAEC

To assess the cytokine expression profile in hBAEC, an RT-qPCR-based method was used for the detection of IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-β, and IL-10, using β-actin as a housekeeping reference gene for normalization. Apical and basolateral samples collected from all-time points were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 1 h. The RT-qPCR was performed using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green One-Step Kit (Bio-Rad Cat. No. 172-5151) following manufacturer’s instructions. The primers sequences to target the cytokines were obtained from a previous study [

22] and are listed in

Table S2. The reverse transcription step was carried out at 50°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of PCR amplification on the AriaMx Real-Time PCR System (Agilent Cat. No. G8830A). The amplification conditions included denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing and extension at 52°C for 30 sec, followed by Melt Curve analysis.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed, and plots were generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software (Boston, Massachusetts, USA). P value,

p<0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses. The viral particles obtained from the RT-qPCR assay were evaluated by comparing all time points from day 0 to day 4 (for SARS-CoV-2 and IFAV_H1N1) and to day 6 (for RSV), using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. NT

50 titers were calculated using non-linear regression analysis. To quantify the colocalization of Muc5ac and ZO-1 across the hBAEC imaged by widefield deconvolution immunofluorescence microscopy, we applied standard colocalization analysis, including Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) and Mander’s colocalization coefficient (MCC) analyses [

23], with statistical significance assessed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. To evaluate the cytokines expression compared to the housekeeping gene β-actin, the relative expression was calculated following the 2-

ΔΔCt Livak method [

24] and the data was analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple comparison test.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants, their susceptibility to neutralization by commercial human antibodies, and the mutation profiles within the S-protein region of newly emerged strains. Additionally, we assessed the ability of these variants to infect hBEACs, both alone and in combination with common respiratory viruses. The hBEACs were cultured at ALI, allowing them to differentiate into a pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium that closely resembles the in vivo human airway.

Our findings confirmed numerous studies indicating that the S-protein is a highly polymorphic gene containing multiple amino acid substitutions that create a unique pattern to every lineage of Omicron

[3,4,5]. When investigating the response of Omicron variants in comparison to a parent strain isolated at the beginning of the pandemic against Abs neutralization, we found a weak antiviral activity of AM359b, casirivimab and bebtelovimab against Omicron JN.1 or its most recent descendants. This effect was similar when evaluating different human sera from individuals infected at the early stages of the pandemic and without receiving vaccination.

Several antibody therapies have been evaluated in COVID-19 patients. The administration of casirivimab / imdevimab (REGEN-COV

®) reduced the viral load and improved clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 on low-flow or no supplemental oxygen conditions [

31]. This monoclonal antibody combination was authorized for the treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis of patients with COVID-19; however, it showed a more potent neutralization effect against initial SARS-CoV-2 variants compared to the Omicron variant [

32]. Indeed, starting January 2024, casirivimab is no longer authorized for therapeutic or post-exposure treatment in COVID-19 patients anymore [

33]. Another antibody, bebtelovimab, received emergency-use authorization by the FDA in the US back in 2022, as early therapy in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, especially high-risk adults and children over 12-year-old. However, the FDA update from 2024 provided information about reduced activity of bebtelovimab against the Omicron subvariants BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 [

34]. This poor response to antibody therapy shown by Omicron is also supported by other studies using early emerging Omicron subvariants [

35,36].

The Omicron variant exhibited more than a dozen mutations in the S-protein compared to the original strain isolated in Wuhan at the beginning of the pandemic, which have been linked to changes in viral pathogenesis, transmissibility and enhanced antibody evasion [

37]. Studies have also demonstrated significant reinfection rates and vaccine failure mainly due to the ability of Omicron to escape antibody neutralization [

38,39]. In recent years, several studies analyzed the impact of these spike protein mutations and their ability to escape the immune response of the host [

40,41]. Another group reported an impaired neutralizing activity of RBD class 3 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against XBB and BQ subvariants containing the R346T mutation [

42]. In correlation with this and another study [

43], we found the R346T amino acid substitution in LB.1, KP.2 and its descendants, KS.1 and XDK, whose response to neutralizing antibodies was also weak, probably explaining their reduced neutralization by sera. In contrast, both KP.3.1.1 and KP.3.1.4 variants lack the above-mentioned substitution, but harbor the Q493E mutation, which has been previously related to a reduced binding affinity to ACE2 but not a decreased antibody neutralization in a KP.3 strain [

44]. This is in alignment with our findings, since the KP.3.1.1 and KP.3.1.4 strains show a better response to neutralization assays within the pool of subvariants that we investigated. In line with this, a recent study suggests that the deletion of a serine in position 31, observed in LB.1, KP.2.3, KP.3 and KP.3.1.1 is the primary cause for reduced neutralizing antibody titers [

45], although in our findings LB.1 and KP.3.1.1 did not carry this mutation. It is noteworthy that the dominance of the KP.3.1.1 subvariant was the longest within the prevalent Omicron strains, although its correlation to the mutations on the S-protein has not been proved yet. Broadly expanded within the collection of omicron strains from this study is the polymorphism N969K, previously related to the modified expression levels of the S-protein in the cell surface, which impacts the syncytia formation of the virus and, thus, affects its recognition by the host [

46]. Additionally, the amino acid change D796Y present in all the strains from our study except for KP.2, has been correlated to a decreased neutralization by human sera without a significant modulation of the S-protein [

47]. All together, these studies help to explain the low responding phenotype to host immunity that these subvariants show in our findings, both against commercial neutralizing antibodies and human sera, highlighting the importance to renovate the composition of vaccines to cover these new circulating subvariants and bring back the immunity levels to the vaccinated population.

The implementation of measures to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the past also helped to reduce the incidence of cases with other respiratory viruses. However, since the beginning of the pandemic, several cases have been reported with SARS-CoV-2 coinfection. With the end of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the lack of these preventive actions, viruses like Influenza and RSV increased their circulation and more cases were reported soon after, providing all the necessary factors for the appearance of coinfections. However this phenomenon is still poorly investigated, with a prevalence not very well reported and sometimes miss-considered at low frequency [

48].

Influenza and RSV are reported as one of the most common respiratory viral illnesses by the CDC, and at higher risk in older adults, young children, people with weakened immune systems and pregnant women, within other populations [

49]. A recent example of coexistence of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus was highlighted in a study where authors found the occurrence of three outpatient coinfections in the pediatric population [

50]. On the other hand, RSV is the main cause of bronchiolitis worldwide and the most common lower respiratory tract infection, especially in young children [

51]. This population is particularly susceptible to respiratory viral coinfections [

52], where a high transmission rate of RSV or SARS-CoV-2 has been reported [

53]. Immortalized cell lines are commonly used for virus characterization due to their rapid growth, controlled conditions, robustness, and relatively short time requirements. Instead, hAEC provides a more physiologically relevant 3D model for studying viral infections under conditions that closely mimic the human respiratory tract’s environment and cellular functions. These live cells are derived from human donors and can develop stratified epithelium and produce immunological mediators, offering a more accurate representation of the in response. Several studies have previously investigated the effects of viral monoinfections of seasonal alpha- and betacoronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 or Spike glycoprotein S1 domain from SARS-CoV-2 [

54,55,56,57,58], and others evaluated the effects of monoclonal antibodies using an ALI model [

59]. Zarkoob and colleagues investigated the cellular complexity of human alveolar and tracheobronchial ALI tissue models during SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 and Influenza A virus, but as monoinfections [

60], and another study evaluated the coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza coinfection but using an in vitro assay with Calu-3 cell line [

61].

Due to the associated worse outcomes that may appear in viral coinfections compared to monoinfections, here we evaluated the SARS-CoV-2 infection of the ancestral WA1/2020 strain and the prevalent Omicron subvariants JN.1 and KP.3.1.1 using hBEAC in an ALI model (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). Our results indicated a lower CPE induced by WA1/2020 and lower infection in the apical and basolateral side of the hBAEC compared to the Omicron subvariants, where both JN.1 and KP.3.1.1 showed an increase in the viral load that peaked at 2 days post-infection. (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These findings were consistent through several readouts including CPE observations, viral RNA quantification by R-qPCR and viral detection by immunofluorescence analysis (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) but are in contraposition to previous reports where authors described a less favorable Omicron replication and less severity of infection in the lower respiratory tract [

62]. In some cases, this effect has been attributed to viral escape mechanisms against the immunity generated by vaccination and previous infections. Another work published in 2022 reported similar replication between Omicron BA.1 and the Delta variant in human nasal epithelial 3D cultures, but Omicron replication was significantly decreased in lower airway organoids [

63]. We believe that the discrepancies with previous studies may be related to differences in the viral cell entry between early circulating strains with the most recent prevalent subvariants, but this needs to be further investigated. In addition, we observed a high production of IFN-

β in the inserts infected with WA1/2020, which may be responsible for the low infection with this strain, as a previous study reported that IFN-

β treatment effectively block SARS-CoV-2 replication [

64]. Besides, the combination of KP.3.1.1 with IFAV_H1N1 or RSV induced more significant damage to the epithelium, but did not enhance the apical infection compared to Omicron monoinfection, suggesting that the combination with these two viruses did not attenuate the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in hBAEC.

In summary, hBAEC cultures proved to be a representative model for the characterization of viral respiratory mono- and coinfections in lower airway epithelial cells. Human cells were successfully cultured on permeable support with minimal differentiation requirements, offering valuable insights into the behavior of viruses coexisting in the lung environment, while avoiding the use of animal models. We recognize that additional characterization should include the use of lung organoids, as they allow for the investigation of viral infections’ impact on a broader range of cell types beyond epithelial cells. The data presented here contributes to the understanding of SARS-CoV-2 evolution and infection behaviors when affecting the human lung epithelial cells as a monoinfection or in combination with other respiratory viruses, as well as suggesting that there is still knowledge gaps related to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1.

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is continuously evolving. From January 2024 to March 2025, the Omicron variant was responsible for the different waves of prevalence, which are represented here by JN.1, KP.2, KP.3, KP.3.1.1, XEC and LP.8.1. Information extracted from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) bi-weekly update [

6].

Figure 1.

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is continuously evolving. From January 2024 to March 2025, the Omicron variant was responsible for the different waves of prevalence, which are represented here by JN.1, KP.2, KP.3, KP.3.1.1, XEC and LP.8.1. Information extracted from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) bi-weekly update [

6].

Figure 2.

Commercial antibodies failed to efficiently neutralize the most recent SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. The neutralization efficacy of human antibody AM359b (anti-spike RBD) was assessed against SARS-CoV-2 subvariants circulating from the onset of the pandemic up until JN.1 (a), as well as against WA1/2020 and selected Omicron subvariants (b). Two recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Abs, Casirivimab (c) and bebtelovimab (d), were evaluated against WA1/2020 and selected Omicron subvariants. All antibodies were tested with a concentration range from 1 to 0.062 µg/ml. NT50 represents the concentration required for a 50% neutralization activity.

Figure 2.

Commercial antibodies failed to efficiently neutralize the most recent SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. The neutralization efficacy of human antibody AM359b (anti-spike RBD) was assessed against SARS-CoV-2 subvariants circulating from the onset of the pandemic up until JN.1 (a), as well as against WA1/2020 and selected Omicron subvariants (b). Two recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Abs, Casirivimab (c) and bebtelovimab (d), were evaluated against WA1/2020 and selected Omicron subvariants. All antibodies were tested with a concentration range from 1 to 0.062 µg/ml. NT50 represents the concentration required for a 50% neutralization activity.

Figure 3.

Human convalescent plasma (HCoP) from previous and unvaccinated donors does not provide protection against the newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. The strains include SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020, used as a reference (a), Omicron JN.1 (b), and the newly emergent subvariants (c-h). HUMC-00007, HUMC-00008, HUMC-00009, and HUMC-00011 (human convalescent plasma samples collected in 2020) were tested with a concentration range from 1 to 0.062 µg/ml. NT50 represents the concentration required for a 50% neutralization activity.

Figure 3.

Human convalescent plasma (HCoP) from previous and unvaccinated donors does not provide protection against the newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants. The strains include SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020, used as a reference (a), Omicron JN.1 (b), and the newly emergent subvariants (c-h). HUMC-00007, HUMC-00008, HUMC-00009, and HUMC-00011 (human convalescent plasma samples collected in 2020) were tested with a concentration range from 1 to 0.062 µg/ml. NT50 represents the concentration required for a 50% neutralization activity.

Figure 4.

The new SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants exhibit additional amino acid substitutions in the spike protein. The WA1/2020 strain (hCoV-19/USA-WA1/2020 BEI NR-52281) was retrieved from the GISAID database and used as a reference (*). The absence or presence of mutations in the S-protein ORF2 region is indicated by empty or black circles, respectively, while red circles indicate new mutations in KP.3.1.1 compared to JN.1 and blue circles indicate new mutations present in XDK.1.

Figure 4.

The new SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants exhibit additional amino acid substitutions in the spike protein. The WA1/2020 strain (hCoV-19/USA-WA1/2020 BEI NR-52281) was retrieved from the GISAID database and used as a reference (*). The absence or presence of mutations in the S-protein ORF2 region is indicated by empty or black circles, respectively, while red circles indicate new mutations in KP.3.1.1 compared to JN.1 and blue circles indicate new mutations present in XDK.1.

Figure 5.

New SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants induce high damage in the human bronchial airway epithelium, especially when co-inoculated with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV. From the top to the bottom, mock epithelium (uninfected), monoinfections (WA1/2020, Omicron JN.1, and Omicron KP.3.1.1) and coinfections (KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV) were evaluated. From the left to the right, daily images were taken from 0 to 6 days. Cytopathic effects were identified by visual changes and disruption of the epithelial morphology, as indicated by the arrows. Images were captured at 4x magnification.

Figure 5.

New SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants induce high damage in the human bronchial airway epithelium, especially when co-inoculated with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV. From the top to the bottom, mock epithelium (uninfected), monoinfections (WA1/2020, Omicron JN.1, and Omicron KP.3.1.1) and coinfections (KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV) were evaluated. From the left to the right, daily images were taken from 0 to 6 days. Cytopathic effects were identified by visual changes and disruption of the epithelial morphology, as indicated by the arrows. Images were captured at 4x magnification.

Figure 6.

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron actively replicates in the human bronchial airway epithelium, both as monoinfection and in coinfection with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV. SARS-CoV-2 viral particles recovered from the hBAEC were quantified by RT-qPCR. Data is presented as the average of two technical replicates from two independent biological samples, with standard deviation (SD). (a) apical wash of hBAEC in WA1/2020, JN.1, and KP.3.1.1 monoinfections; (b) the basolateral wash of hBAEC in WA1/2020, JN.1, and KP.3.1.1 monoinfections; (c) the apical wash of hBAEC in KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV coinfections; (d) and the basolateral wash of hBAEC in KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV coinfections. SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels are expressed as copies per insert. LOQ indicates the limit of quantification for the RT-qPCR. The line above dots with an asterisk sign indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) in the infection levels compared to day 0 in each assay.

Figure 6.

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron actively replicates in the human bronchial airway epithelium, both as monoinfection and in coinfection with IFAV_H1N1 and RSV. SARS-CoV-2 viral particles recovered from the hBAEC were quantified by RT-qPCR. Data is presented as the average of two technical replicates from two independent biological samples, with standard deviation (SD). (a) apical wash of hBAEC in WA1/2020, JN.1, and KP.3.1.1 monoinfections; (b) the basolateral wash of hBAEC in WA1/2020, JN.1, and KP.3.1.1 monoinfections; (c) the apical wash of hBAEC in KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV coinfections; (d) and the basolateral wash of hBAEC in KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1+RSV coinfections. SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA levels are expressed as copies per insert. LOQ indicates the limit of quantification for the RT-qPCR. The line above dots with an asterisk sign indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) in the infection levels compared to day 0 in each assay.

Figure 7.

The newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants enhanced the infectivity and cytopathic effect in the human bronchial airway epithelium compared to the ancestral strain. Human bronchial airway epithelial cells (hBAEC) were infected with each corresponding SARS-CoV-2 strain at 2x10^5 PFU/ml per insert. hBAEC infected with monoinfections (WA1/2020, JN.1 and KP.3.1.1) and coinfection with KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 were fixed on day 4 post-infection, while coinfection with KP.3.1.1+RSV was fixed on day 6 post-infection. hBAEC were stained with antibodies against cell markers to assess the epithelium differentiation (Muc5ac for goblet cells -purple- and ZO-1 for tight junctions - red); with anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody / goat polyclonal Alexa Fluor™ 488 (green) for viral antigen detection and counter-stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (blue). From left to right, images are visualized at 10x magnification for Mock and or infected hBAEC with WA1/2020, JN.1 and KP.3.1.1. and are representative of two independent inserts for each condition. The cross-section scale bar is 10 μm. BF, brightfield; AF, Alexa Fluor.

Figure 7.

The newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants enhanced the infectivity and cytopathic effect in the human bronchial airway epithelium compared to the ancestral strain. Human bronchial airway epithelial cells (hBAEC) were infected with each corresponding SARS-CoV-2 strain at 2x10^5 PFU/ml per insert. hBAEC infected with monoinfections (WA1/2020, JN.1 and KP.3.1.1) and coinfection with KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 were fixed on day 4 post-infection, while coinfection with KP.3.1.1+RSV was fixed on day 6 post-infection. hBAEC were stained with antibodies against cell markers to assess the epithelium differentiation (Muc5ac for goblet cells -purple- and ZO-1 for tight junctions - red); with anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody / goat polyclonal Alexa Fluor™ 488 (green) for viral antigen detection and counter-stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (blue). From left to right, images are visualized at 10x magnification for Mock and or infected hBAEC with WA1/2020, JN.1 and KP.3.1.1. and are representative of two independent inserts for each condition. The cross-section scale bar is 10 μm. BF, brightfield; AF, Alexa Fluor.

Figure 8.

Colocalization analysis of hBAEC differentiation markers in SARS-CoV-2 infected tissues. Cells infected with WA1/2020, Omicron JN.1 and Omicron KP.3.1.1 were labeled with Dapi, Muc5ac and ZO-1 and co-stained with Alex Fluor 488. Merged and colocalization images are shown for each co-staining: (a) Dapi + Alexa Fluor 488; (b) Muc5ac + Alexa Fluor 488; (c) ZO-1+ Alexa Fluor 488. The scale bar for the merged images is 10 um and the intensity for the colocalization images is 12.5%. Pearson’s R values and the Mander’s overlap coefficients were obtained from the Nikon Ti2 Epi-fluorescence microscope and NIS Elements imaging software (Version 5.30.06). Analysis of variances (ANOVA) was performed followed by a Turkey’s multiple comparisons test with GraphPad Prism 10 (d-f).

Figure 8.

Colocalization analysis of hBAEC differentiation markers in SARS-CoV-2 infected tissues. Cells infected with WA1/2020, Omicron JN.1 and Omicron KP.3.1.1 were labeled with Dapi, Muc5ac and ZO-1 and co-stained with Alex Fluor 488. Merged and colocalization images are shown for each co-staining: (a) Dapi + Alexa Fluor 488; (b) Muc5ac + Alexa Fluor 488; (c) ZO-1+ Alexa Fluor 488. The scale bar for the merged images is 10 um and the intensity for the colocalization images is 12.5%. Pearson’s R values and the Mander’s overlap coefficients were obtained from the Nikon Ti2 Epi-fluorescence microscope and NIS Elements imaging software (Version 5.30.06). Analysis of variances (ANOVA) was performed followed by a Turkey’s multiple comparisons test with GraphPad Prism 10 (d-f).

Figure 9.

Coinfection with Influenza A H1N1 or RSV does not affect the replication capacity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in the hBAEC. Virus levels are expressed as log10 copies/ml. Graphs display the levels of (a) IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1 viral particles recovered from apical and basolateral wash samples, and (b) RSV and KP.3.1.1 viral particles recovered from apical and basolateral wash samples. Data are presented as the average of two technical replicates from two independent biological samples, with the standard deviation (SD). LOQ indicates the limit of quantification for the RT-qPCR.

Figure 9.

Coinfection with Influenza A H1N1 or RSV does not affect the replication capacity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in the hBAEC. Virus levels are expressed as log10 copies/ml. Graphs display the levels of (a) IFAV_H1N1 and KP.3.1.1 viral particles recovered from apical and basolateral wash samples, and (b) RSV and KP.3.1.1 viral particles recovered from apical and basolateral wash samples. Data are presented as the average of two technical replicates from two independent biological samples, with the standard deviation (SD). LOQ indicates the limit of quantification for the RT-qPCR.

Figure 10.

Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariant with Influenza A virus H1N1 or Respiratory Syncytial Virus affected the goblet cells and tight junctions in hBAEC. Human bronchial airway epithelial cells (hBAEC) were infected coinfected with KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 or KP.3.1.1+RSV at 2x10^5 PFU/ml of each combination per insert (Mock and KP.3.1.1 images are included as a side-by-side reference for the coinfections). Inserts were fixed on day 4 post-infection in the case of IFAV_H1N1 and on day 6 post-infection, in the case of RSV. hBAEC were stained with antibodies against cell markers to assess the epithelium differentiation (Muc5ac for goblet cells -purple- and ZO-1 for tight junctions - red), and counter-stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (blue). Images are representative of two independent inserts for each condition. The cross-section scale bar is 10 μm. BF, brightfield.

Figure 10.

Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariant with Influenza A virus H1N1 or Respiratory Syncytial Virus affected the goblet cells and tight junctions in hBAEC. Human bronchial airway epithelial cells (hBAEC) were infected coinfected with KP.3.1.1+IFAV_H1N1 or KP.3.1.1+RSV at 2x10^5 PFU/ml of each combination per insert (Mock and KP.3.1.1 images are included as a side-by-side reference for the coinfections). Inserts were fixed on day 4 post-infection in the case of IFAV_H1N1 and on day 6 post-infection, in the case of RSV. hBAEC were stained with antibodies against cell markers to assess the epithelium differentiation (Muc5ac for goblet cells -purple- and ZO-1 for tight junctions - red), and counter-stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (blue). Images are representative of two independent inserts for each condition. The cross-section scale bar is 10 μm. BF, brightfield.

Figure 11.

SARS-CoV-2 mono- and coinfections induce differential expression of immunological mediators in the apical side of the hBAEC. Apical washes were collected in each timepoint and analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by PCR assay. a) IL-6, b) TNFα, c) IFN-β, d) IL10. All measurements on y axis are represented as relative expression ΔΔCt. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two independent inserts. Significant differences are indicated for p<0.05 in the expression of the tested cytokines, when comparing all time points in each assay.

Figure 11.

SARS-CoV-2 mono- and coinfections induce differential expression of immunological mediators in the apical side of the hBAEC. Apical washes were collected in each timepoint and analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by PCR assay. a) IL-6, b) TNFα, c) IFN-β, d) IL10. All measurements on y axis are represented as relative expression ΔΔCt. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two independent inserts. Significant differences are indicated for p<0.05 in the expression of the tested cytokines, when comparing all time points in each assay.

Figure 12.

SARS-CoV-2 mono- and coinfections induce differential expression of immunological mediators in the basolateral side of the hBAEC. Basolateral media were collected in each timepoint and analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by PCR assay. a) IL-6, b) TNFα, c) IFN-β, d) IL10. All measurements on y axis are represented as relative expression ΔΔCt. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two independent inserts. Significant differences are indicated for p<0.05 in the expression of the tested cytokines, when comparing all time points in each assay.

Figure 12.

SARS-CoV-2 mono- and coinfections induce differential expression of immunological mediators in the basolateral side of the hBAEC. Basolateral media were collected in each timepoint and analyzed for cytokine and chemokine secretion by PCR assay. a) IL-6, b) TNFα, c) IFN-β, d) IL10. All measurements on y axis are represented as relative expression ΔΔCt. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of two independent inserts. Significant differences are indicated for p<0.05 in the expression of the tested cytokines, when comparing all time points in each assay.