4. Discussion

The Silesian region is inhabited by more than 4.3 million people, which is about 12% of the Polish population. The population density in the Silesian Voivodeship is nearly 3 times higher compared to the average population density in Poland (355 vs 121 persons per 1 km2). Moreover, Silesian Voivodeship borders both the Czech Republic and Slovakia and before the pandemic began, thousands of people benefited from the cross-border labor market - many residents of the Silesian region worked in Czech and Slovak companies. After the Polish government introduced mandatory border controls and a two-week quarantine for Poles returning to the country from abroad in March 2020, full border traffic within the internal borders of the European Union was restored on June 13, 2020. Thus, during the period covered by our research, cross-border traffic was no longer restricted, allowing the free circulation of virus variants between neighboring countries.

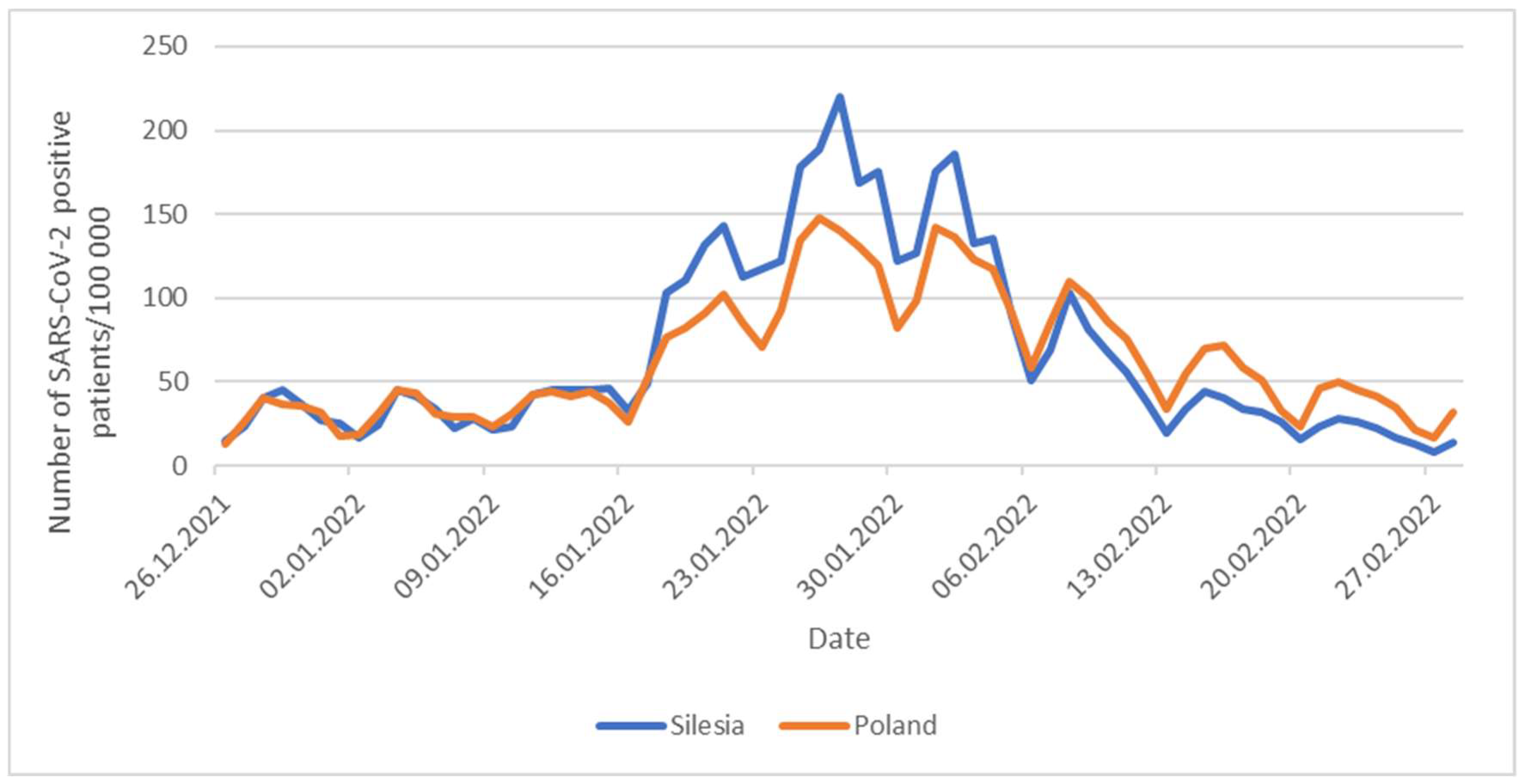

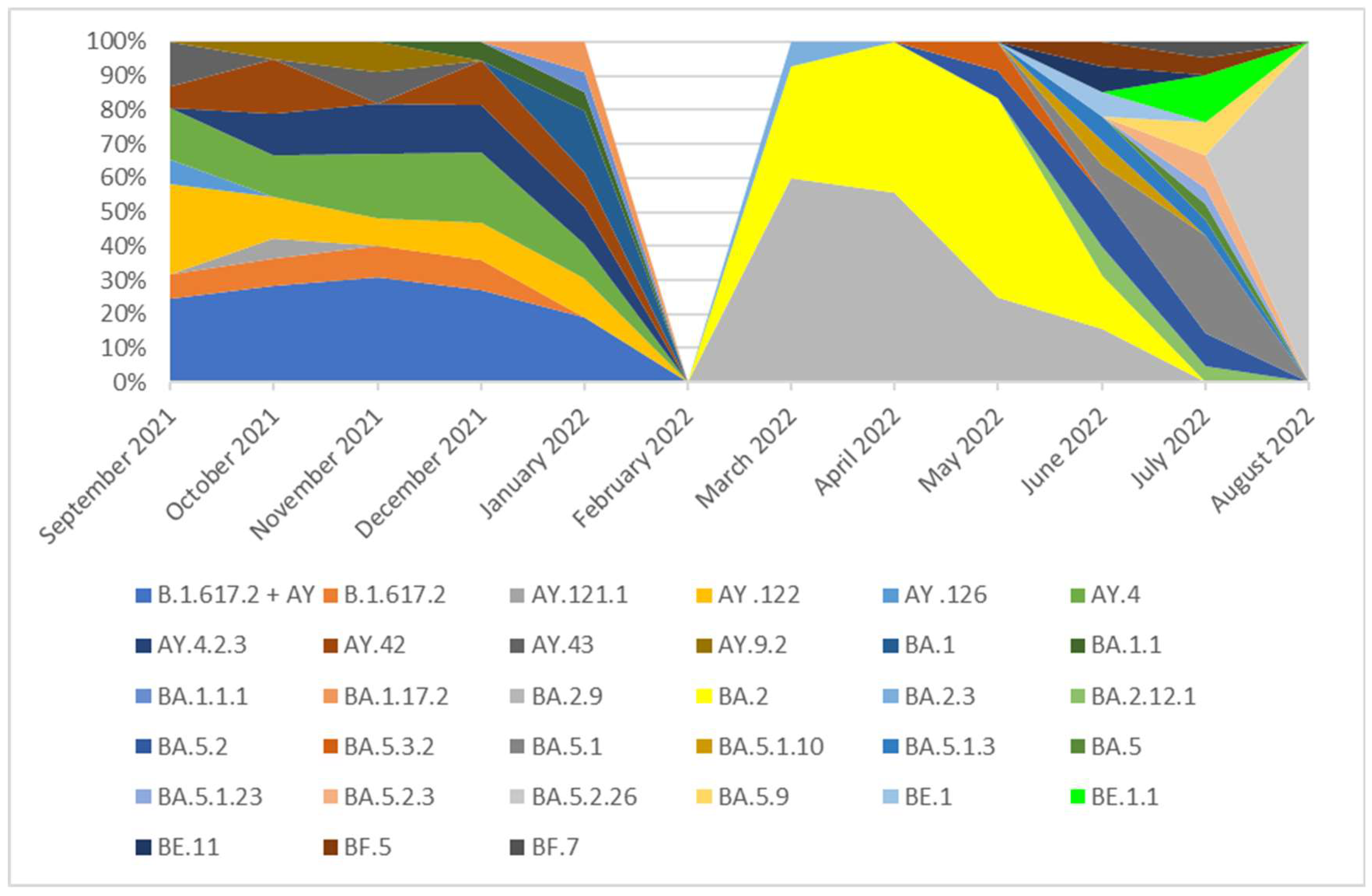

In the period from September 2021 to January 2022, the Delta variant (B.1.617.2+ AY) dominated in Southern Poland. It was consistently replaced by the Omicron B.1.1.529 + BA variant. Contrasting Silesia with Poland, the Omicron variant appeared in Southern Poland earlier. It was first recorded in December 2021 (BA.1.1), while in the rest of the country it appeared in January 2022 and caused the fifth wave which peaked at the end of January 2022 [

17]. The earlier appearance of the Omicron variant in the Silesian province may be responsible for different dynamics of the development of the fifth wave of the pandemic in this region compared to the rest of the country (

Figure 10). Namely, during the initial phase of the fifth wave of the pandemic, in the second half of January 2022, the incidence rate of positive cases (per 100 000 inhabitants) was more dynamic in Silesia compared to the rest of Poland. Then, in February, a faster decrease in the number of new infections per 100 000 inhabitants was observed is our region than in Poland. This early and rapid spread of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, combined with a significant population density, may explain why the presence of the Delta variant of the virus was no longer observed in Silesia in March.

In March and April, the dominant variant both in Silesia and the rest of the country was the BA.2.9 one. The BA.2 variant occurred with a similar frequency. Interestingly, in the given period, the BA.2.7 variant also appeared with high frequency in Poland, but it was not noted in Silesia. Since June 2022, a large variety of variants without any specific dominance has been observed in Southern Poland. A similar situation occurred throughout Poland.

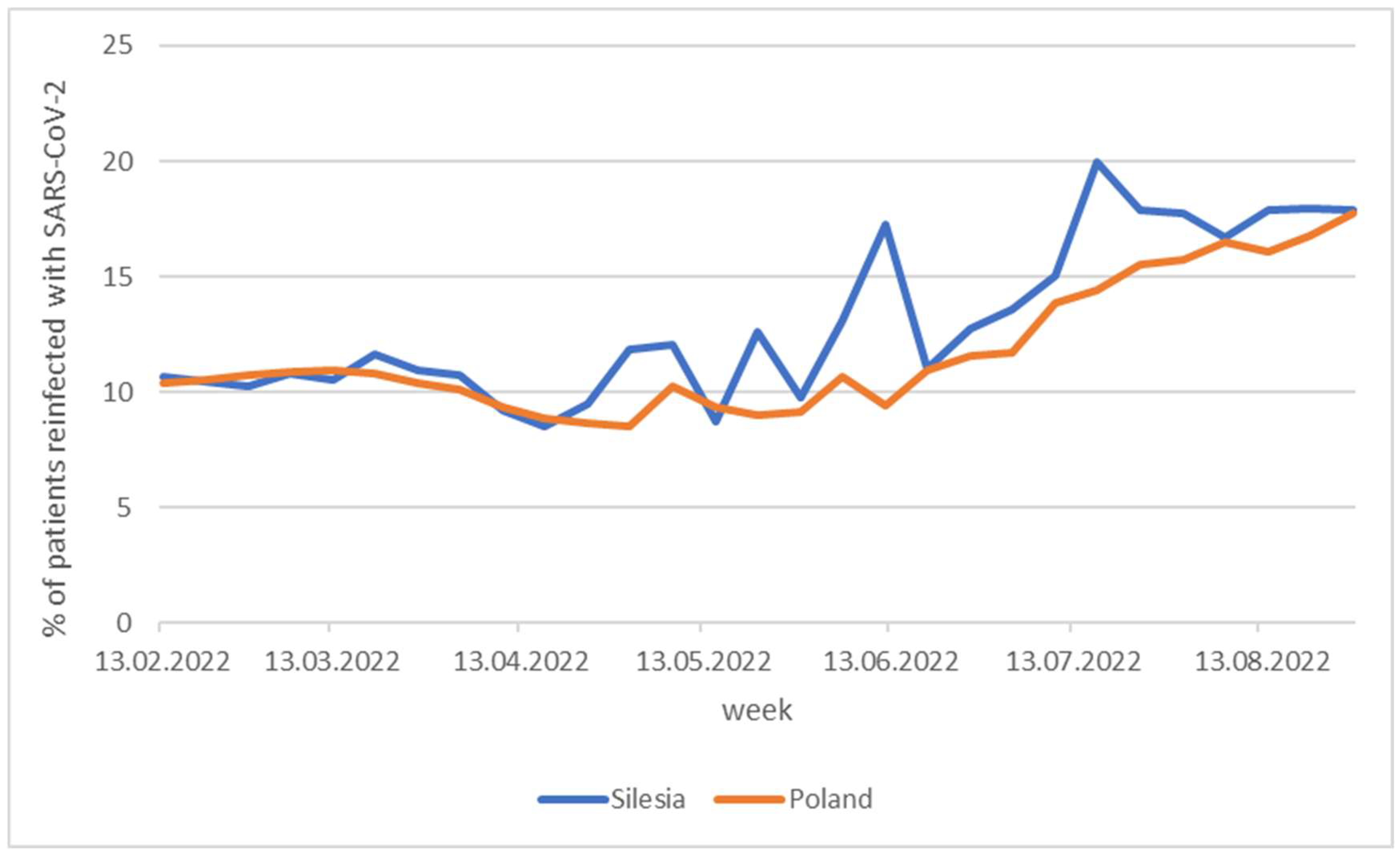

According to the data available on the government website, during the period from early May to mid-July, considerably more cases of reinfection were observed in the region covered by our research compared to the rest of the country (

Figure 11), what is especially noteworthy. In Silesia BA.5 subvariants (BA.5.2 and BA.5.32) appeared as early as May, while in the rest of the country presence of BA.5.1, BA.5.2, and BA.5.2.1 subvariants was recorded two months later, in July. The BA.5 clades stem from BA.2 by acquisition of Δ69-70 deletion in N-terminal domain, L452R, F486V, and reversed R493Q mutations in the receptor biding region, S704L mutation located outside the receptor biding region of the spike protein as well as D3N mutation in M protein.

Previously conducted studies have shown that BA.5 competed with BA.2 because of its increased resistance to neutralization [

18,

19,

20] and its higher infectivity resulting from higher replication fitness, transmissibility, and pathogenicity [

21,

22,

23]. The functional examination of impact of mutations characterizing BA.5 S proteins showed that mutations of Δ69-70, L452R, and F486V contribute to the higher infectiousness and fusogenicity of the BA.5 S protein. Moreover, L452R and F486V substitutions were responsible for reduced sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies [

24].

The other studies have shown that antibodies isolated from BA.1 infected or vaccinated individuals showed reduced efficacy against L452 mutations causing the most severe escape of variants BA4/BA.5 harboring L452R mutation [

20] which may explain the ability of the BA.5 variants to evade the neutralizing effect of antibodies arisen during previous infections. The importance of L452R mutation for impairing antibody binding allowing the B5 variant to escape the immune system was also demonstrated by Tuekprakhon et al. [

25]. Moreover, S371F mutation (occurring in Omicron but not Delta variant) was involved in the emergence of conformational changes of the region recognized by antibodies isolated from vaccinated individuals who had recovered from SARS [

20].

What is more, in June and July in Silesia region we observed the occurrence of BA.2.12.1, the another derivative of BA.2 variant arising by acquisition of L452Q and S704L mutations in addition to the known mutations in BA.2. Omicron BA 2.12.1 subvariant appeared in December 2021 in the United States and spread very fast in many parts of US, but also in other countries [

26]. Many studies showed that the BA.2.12.1 like BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants substantially escape neutralizing antibodies induced by both vaccination and infection. Compared to BA.2 Omicron variant, BA.2.12.1 subvariant shows stronger immune escape and faster transmissibility. In contrary to BA.5, BA.2.12.1 Omicron subvariant showed only modest resistance to sera from vaccinated and boosted individuals compared to BA.2 [

19]. The reduced sensitivity of BA.2.12.1 compared to BA.2 S protein to neutralization by sera vaccinated donors was found, however, this effect was donor dependent. On the contrary, S704L mutation increased susceptibility to neutralization [

24]. Noteworthy, BA.2.12.1 variant has not been detected either in the rest of Poland or in neighboring countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia), thus, it was probably imported to Silesia from further regions of Europe or the world. In Silesia BA.2.12.1 was completely replaced by BA.5.2.26 in August, which reflects a transmission advantage of BA.5 subvariants. The dominance of previously circulating variants of the virus by more efficient variants has also been observed in other regions, e.g. South Korea, where BA.1 was the dominant variant for 10 weeks starting from the 1st week of 2022, BA.2 was the dominant variant in the 12th and 13th weeks of 2022, and they were subsequently replaced by BA.5 which became the dominant variant in June 2022 [

28].

In the Czech Republic, the Omicron variant was first noted in December 2021. An earlier dominance of the Omicron variants was also observed, which replaced the delta variants already in January 2022, when this variant was just appearing in Silesia. Similarly to Silesia and the rest of Poland, the dominance of the BA.2.9 variant has also been observed since March 2022. Since June, the diversity of variants in the Czech Republic has been very large.

Similarly in Slovakia, we observed the earlier displacement of the delta variant by omicron, which dominated already in January 2022. What is more, comparing Slovakia with Silesia, a clear difference can be noticed, consisting in the dominance of the BA.2 variant from March to May 2022 instead of the BA.2.9 variant.

When comparing the molecular diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in Silesia with the above regions, the difference in the occurrence of variants of the BF (BF.5 and BF.7) line locally in Silesia should be also noted What is more, we observed greater diversity among BE line variants (BE.1, BE.1.1 and BE.1).

Analyzing the dynamics of the appearance of individual variants globally, it can be concluded that the Omicron variant appeared earlier in the world than in the regions discussed in this work. It was first sequenced in November 2021 in South Africa, while in Silesia it appeared in December 2021, as well as in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In other regions of our country, it was detected in January 2022 [

29]. An interesting aspect seems to be the earlier appearance of the Omicron variant in Silesia than in the rest of Poland. It seems likely that the variants moved from our southern neighbors into the country. It should be noted, however, that not all samples were reported in GISAID and it cannot be ruled out that Omicron had occurred in other regions of Poland earlier.

Skuza et al. conduct an active monitoring program among military personnel to identify Variants of Concern (VOC) of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, with a particular focus on overseas military operations. Screening of 1699 soldiers using RT-qPCR tests was conducted between November 2021 and May 2022. Out of these, 84 samples tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and met the criteria for whole genome sequencing analysis for variant identification [

30]. Based on analysis of samples from 79 soldiers tested in Poland between November 2021 and March 2022, it can be inferred that the obtained results match the molecular analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in Silesia. Until December 2021, the Delta variant dominated, and then it was replaced by the Omicron lineage from January to March 2022. Similarly to Silesia, the variants BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.1.1.1, and BA.2.9 were dominant in this period. The BA.2.3 variant which was observed in our region in March did not appear in the study by Skuza et al.. Additionally, the population studied by Skuza et al. was characterized by greater molecular diversity. What is more, in March, the Delta variant still appeared there, which had already been completely replaced by Omicron in Silesia during this period [

30]. This difference may be due to the fact that Omicron was detected in Silesia as early as December 2021, while in the cohort studied by Skuza this variant was observed only in January 2022. Similar clades were identified in 89 soldiers deployed from Romania in February and March 2022. However, the BA.1.1.13 variant occurred more frequently than among Polish soldiers and samples isolated in Silesia. Similarly, among soldiers returning from France between February and June 2022, the BA.2.9 variant predominated. Additionally, Skuza et al. found a high frequency of the BA.2.56 line, which did not occur in Silesia. Skuza et al. findings indicate that all genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2 found in Polish Armed Forces members had already been circulating in Poland prior to their return from their missions. This suggests that there was minimal transmission of these variants within the national population, or any transmissions that did occur did not significantly impact the SARS-CoV-2 variants present in Poland.

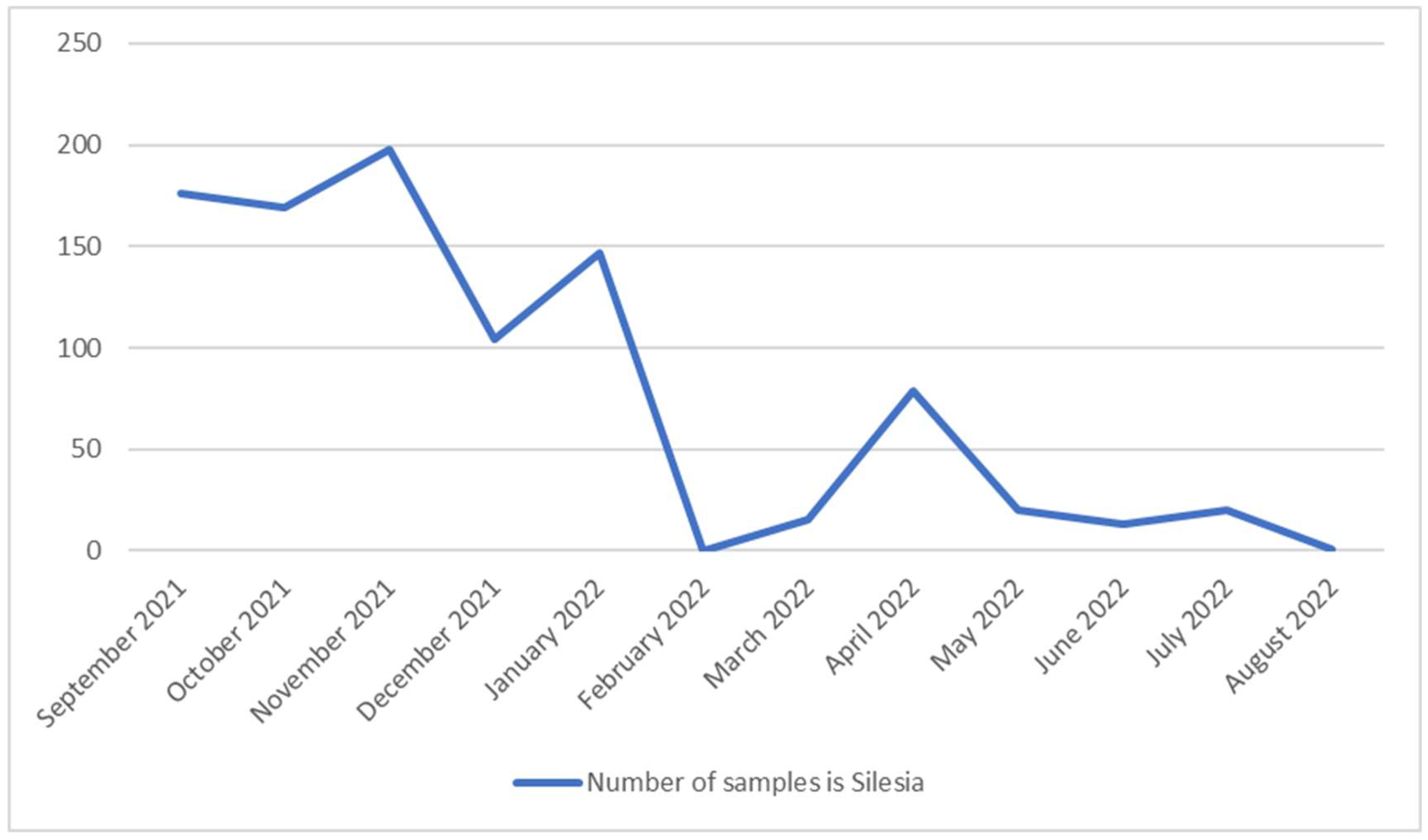

Figure 1.

Changes in the number of SARS-CoV-2 samples isolated from September 2021 to August 2022 in Silesia.

Figure 1.

Changes in the number of SARS-CoV-2 samples isolated from September 2021 to August 2022 in Silesia.

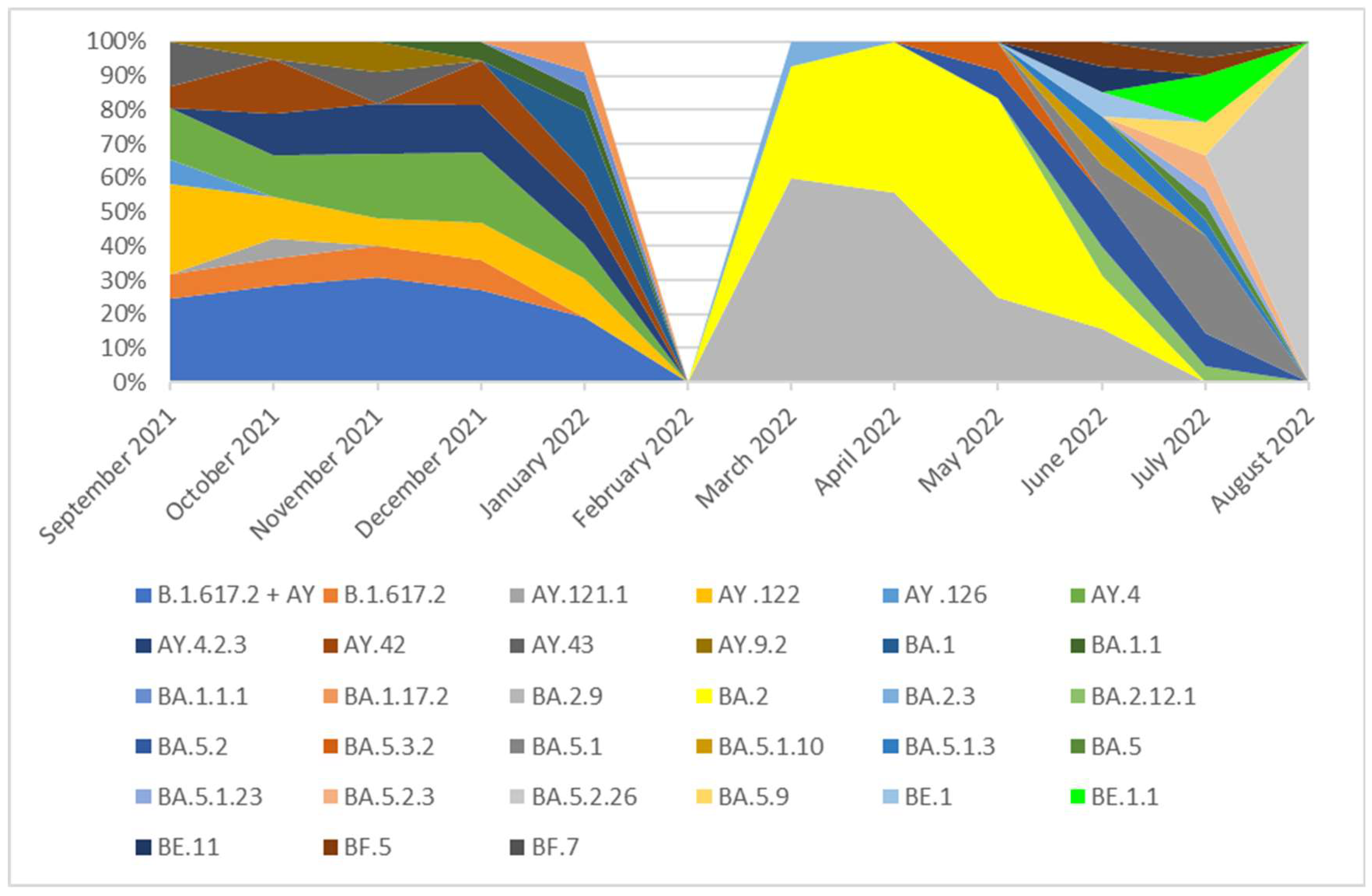

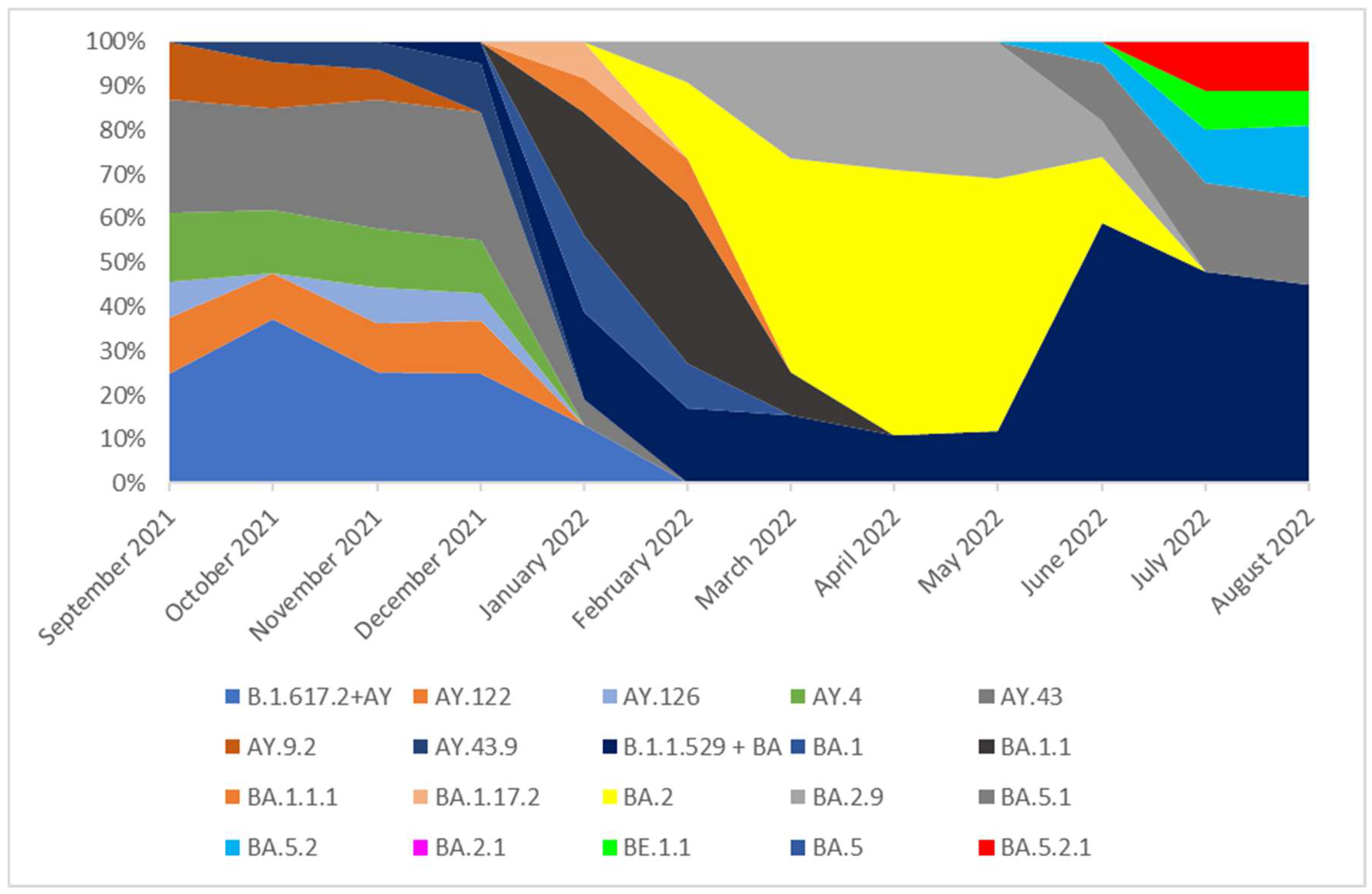

Figure 2.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Southern Poland from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to January 2022, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred in these months with a frequency of >5% were: B.1.617.2, AY.122, AY.4, AY.4.2.3, AY.42. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 8 to 26%). In addition, several cases of lineages: AY.121.1, AY.126, AY.43, AY.9.2 were recorded during this period. The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In March 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Silesia in the next analyzed months. In February 2022 no sample was isolated. In March and April 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.2.9 (60% and 52%, respectively). In May this lineage was superseded by BA.2 (35%). In June 2022 there were no clearly dominant variant, and lineages: BA.2 (15%), BA.2.9 (15%), BA.2.12.1 (8%), BA.5.1 (8%), BA.5.2 (15%), BA.5.1.10 (7%), BA.5.1.3 (7%), BE.1 (7%), BE.11 (7%), BF.5 (7%) were isolated. In July the BA.5.2 lineage was noted in 30%. Except variants: BA.2.12.1 (5%), BA.5.1 (10%), BA.5.1.3 (5%),.5 (5%) there were also new lineages: BA.5 (5%), BA.5.1.23 (5%), BA.5.2.3 (10%), BA.5.9 (10%), BE.1.1 (15%), BF.5 (5%), BF.7 (5%). One sample was isolated in August 2022 and that was BA.5.2.26 (100%).

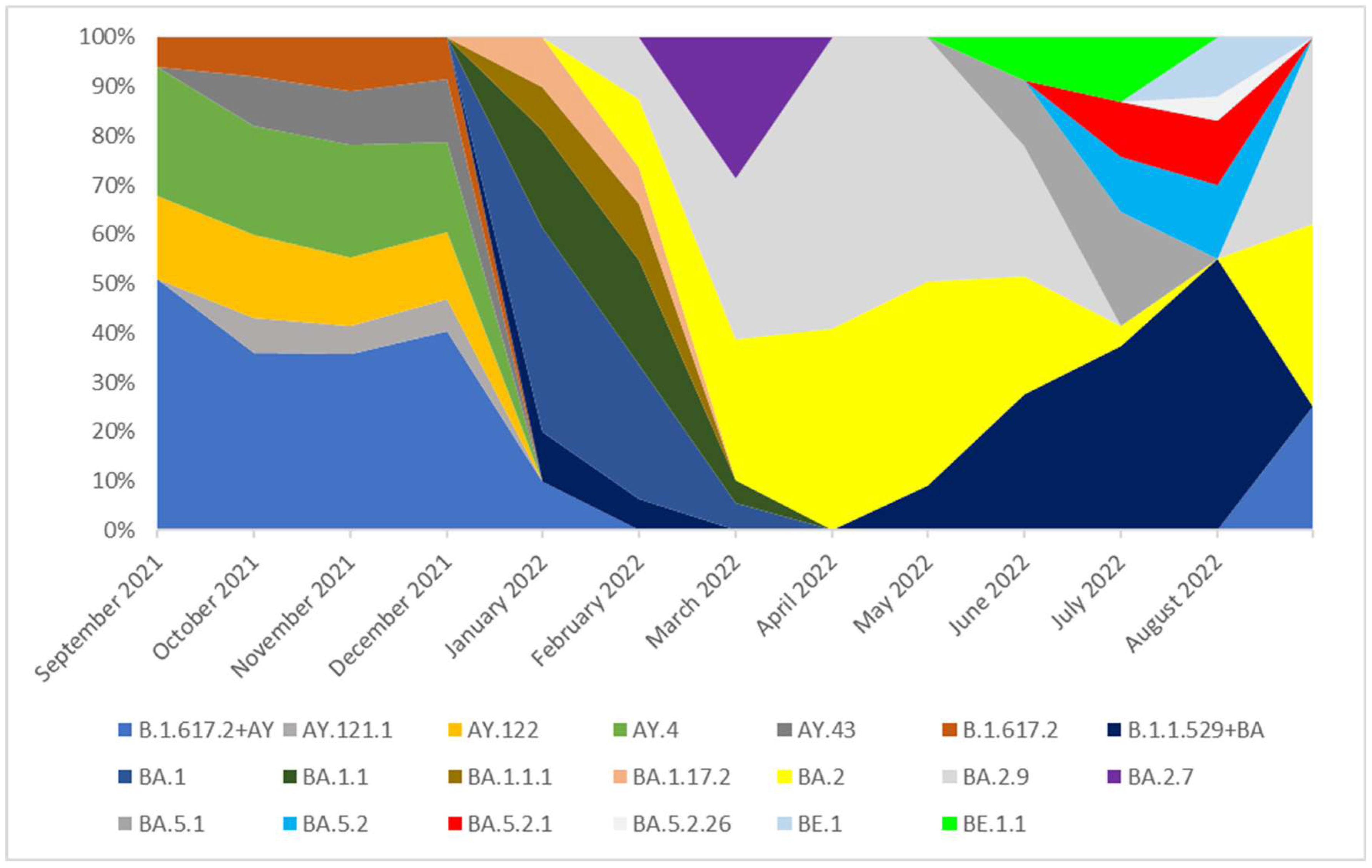

Figure 2.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Southern Poland from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to January 2022, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred in these months with a frequency of >5% were: B.1.617.2, AY.122, AY.4, AY.4.2.3, AY.42. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 8 to 26%). In addition, several cases of lineages: AY.121.1, AY.126, AY.43, AY.9.2 were recorded during this period. The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In March 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Silesia in the next analyzed months. In February 2022 no sample was isolated. In March and April 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.2.9 (60% and 52%, respectively). In May this lineage was superseded by BA.2 (35%). In June 2022 there were no clearly dominant variant, and lineages: BA.2 (15%), BA.2.9 (15%), BA.2.12.1 (8%), BA.5.1 (8%), BA.5.2 (15%), BA.5.1.10 (7%), BA.5.1.3 (7%), BE.1 (7%), BE.11 (7%), BF.5 (7%) were isolated. In July the BA.5.2 lineage was noted in 30%. Except variants: BA.2.12.1 (5%), BA.5.1 (10%), BA.5.1.3 (5%),.5 (5%) there were also new lineages: BA.5 (5%), BA.5.1.23 (5%), BA.5.2.3 (10%), BA.5.9 (10%), BE.1.1 (15%), BF.5 (5%), BF.7 (5%). One sample was isolated in August 2022 and that was BA.5.2.26 (100%).

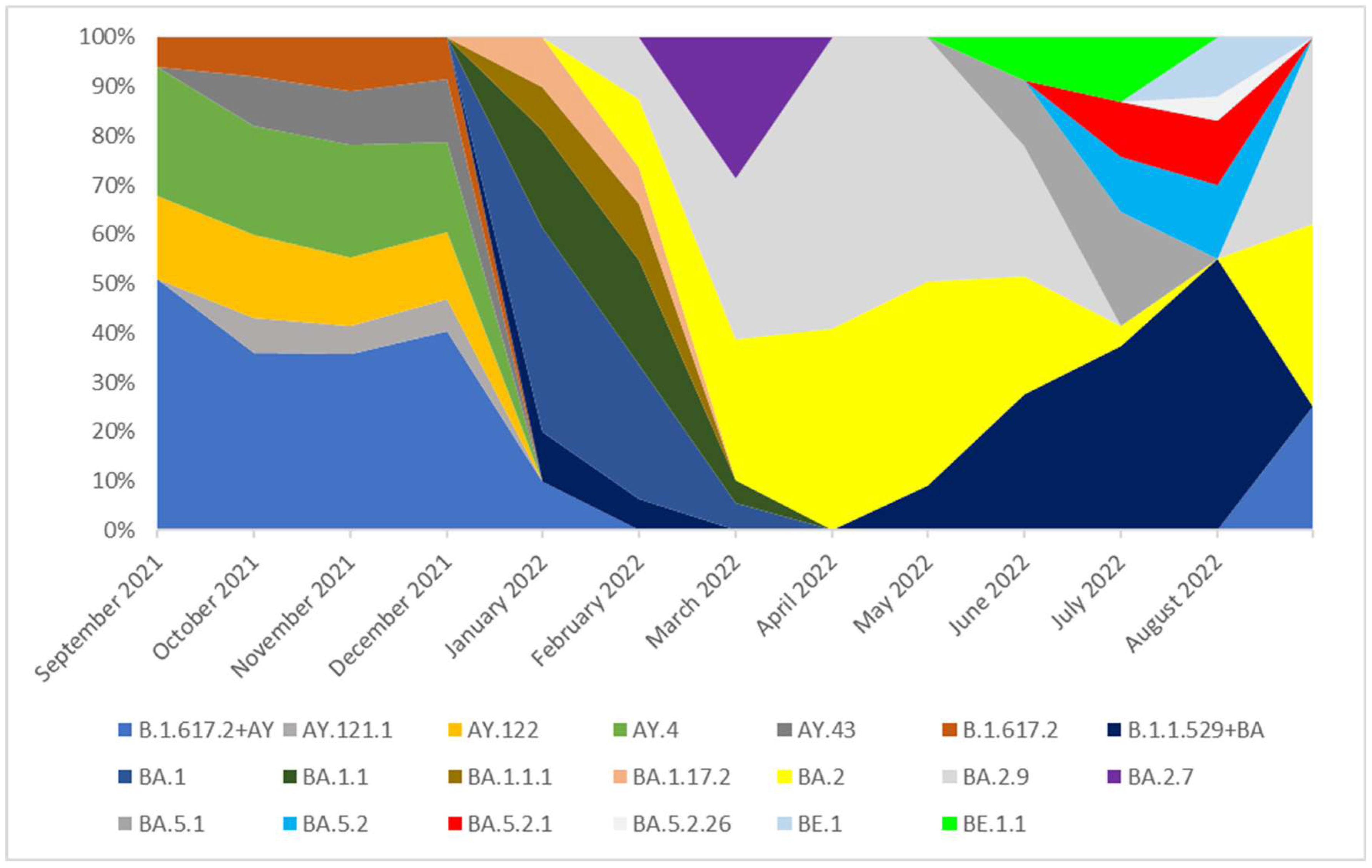

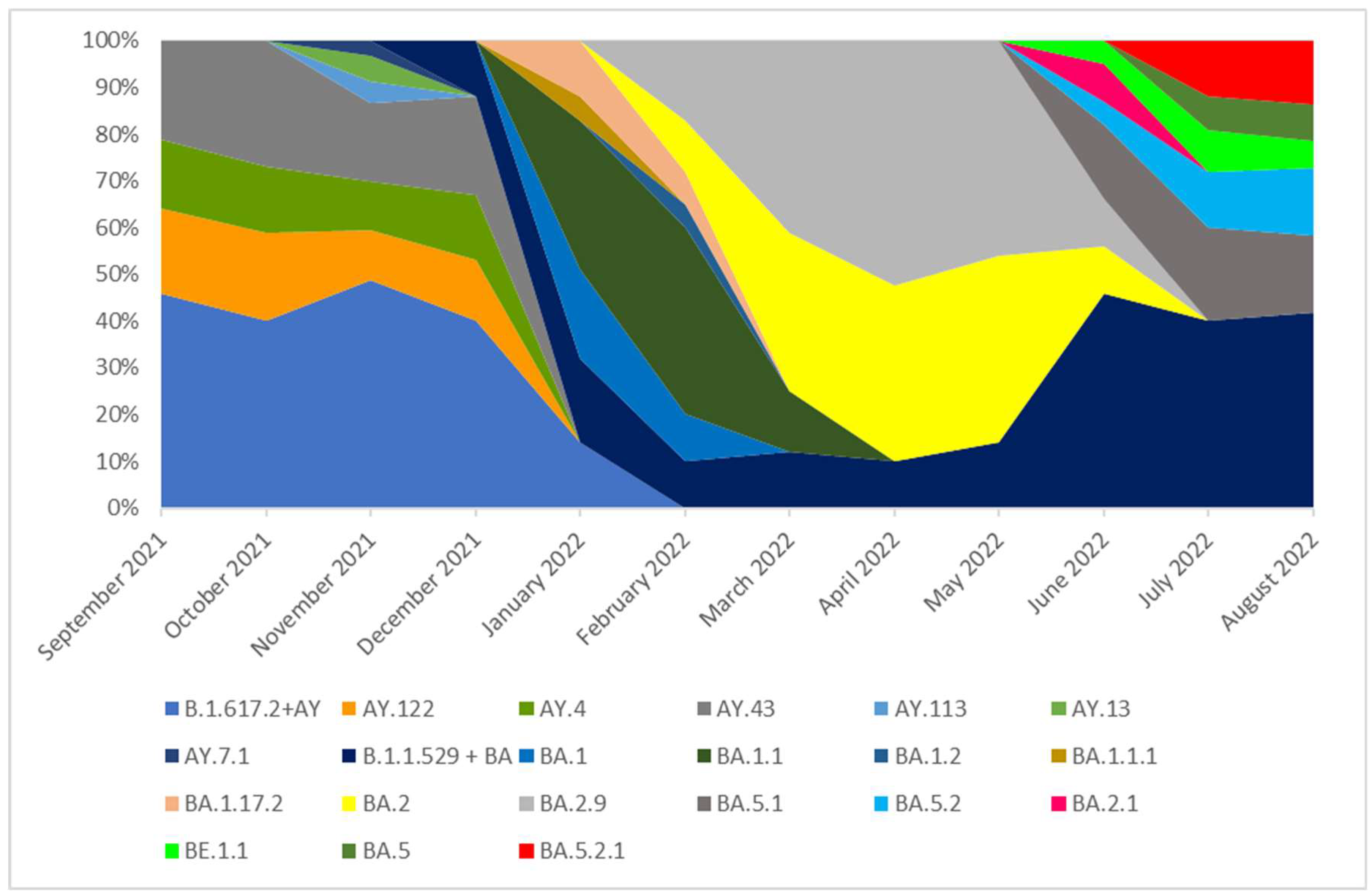

Figure 3.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Poland from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to December 2021, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: B.1.617.2, AY.121.1, AY.122, AY.4, AY.43. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 6 to 26%). The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2+ AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Poland in the next analyzed months. In January and February 2022, the dominant variant was the BA.1 line and next the BA.1.1 variant. From March to June 2022, the dominated lineages were BA.2 and BA.2.9. The variant BA.2.7 (36%) was also observed with high frequency in March. In July and August 2022 none of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

Figure 3.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Poland from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to December 2021, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: B.1.617.2, AY.121.1, AY.122, AY.4, AY.43. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 6 to 26%). The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2+ AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Poland in the next analyzed months. In January and February 2022, the dominant variant was the BA.1 line and next the BA.1.1 variant. From March to June 2022, the dominated lineages were BA.2 and BA.2.9. The variant BA.2.7 (36%) was also observed with high frequency in March. In July and August 2022 none of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

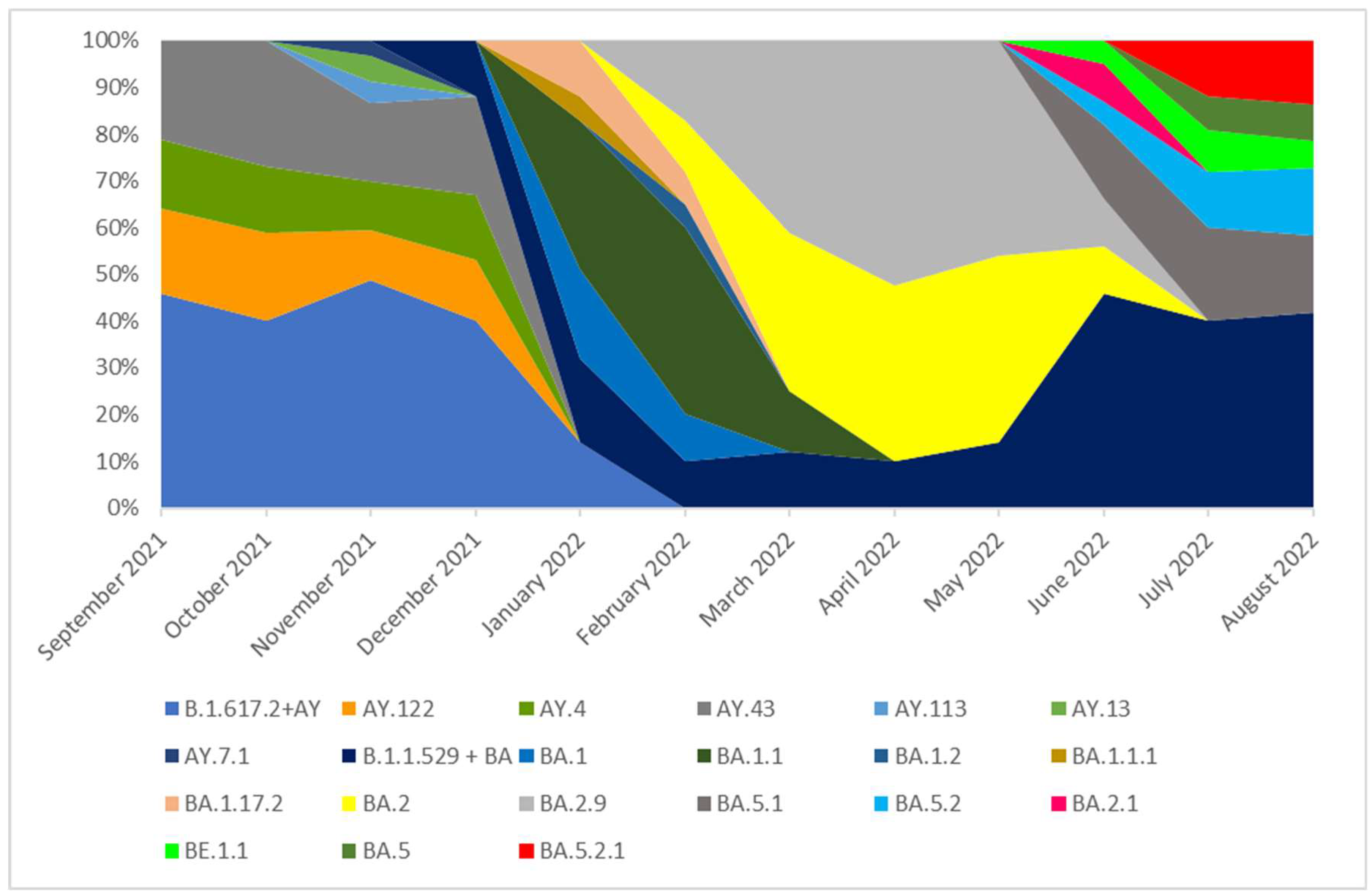

Figure 4.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Czech Republic from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to January 2022, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: AY.122, AY.4, AY.43. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 13 to 27%). In addition, several cases of lineages: AY.113, AY.13, AY.7.1 were recorded during this period. The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Czech Republic in the next analyzed months. In February 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.1.1 (40%). In March this lineage was superseded by BA.2 one (35%). From March to May 2022 the dominant variants were: BA.2 and BA.2.9. From June to August 2022 none of lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

Figure 4.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Czech Republic from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to January 2022, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: AY.122, AY.4, AY.43. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 13 to 27%). In addition, several cases of lineages: AY.113, AY.13, AY.7.1 were recorded during this period. The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Czech Republic in the next analyzed months. In February 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.1.1 (40%). In March this lineage was superseded by BA.2 one (35%). From March to May 2022 the dominant variants were: BA.2 and BA.2.9. From June to August 2022 none of lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

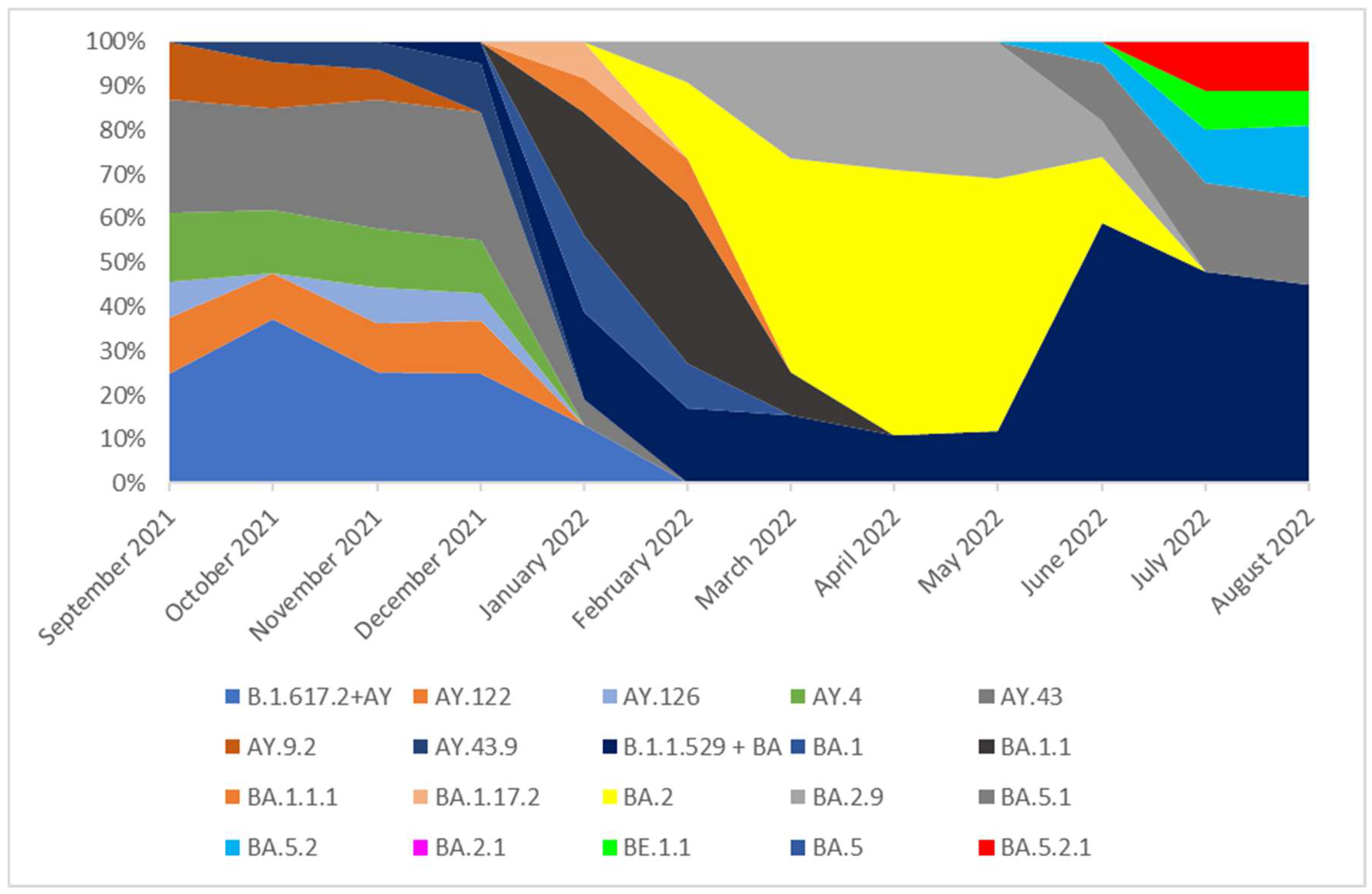

Figure 5.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Slovakia from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to December 2021, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: AY.122, AY.126, AY.4, AY.43, AY.9.2, AY.43.9. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 5 to 9%). The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Slovakia in the next analyzed months. In February 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.1.1 (36%). In March this lineage was superseded by BA.2 one (50%). From March to May 2022 the dominant variant was BA.2. The BA.2.9 variant also occurred with high frequency. From June to August 2022 none of lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

Figure 5.

The percentage distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants isolated in Slovakia from 1th September 2021 to 31th August 2022 based on whole-genome sequencing. In the period from September 2021 to December 2021, the Delta (B.1.617.2+ AY) variant was dominant and lineages which occurred with these months in a frequency of >5% were: AY.122, AY.126, AY.4, AY.43, AY.9.2, AY.43.9. None of these lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency (from 5 to 9%). The remaining lineages of delta variant, occurring with a frequency of <5%, are marked as B.1.617.2 + AY in the chart. In January 2022, the B.1.617.2 + AY variant was replaced by the B.1.1.529 + BA which completely dominated lineages circulating in Slovakia in the next analyzed months. In February 2022, the dominated lineage was BA.1.1 (36%). In March this lineage was superseded by BA.2 one (50%). From March to May 2022 the dominant variant was BA.2. The BA.2.9 variant also occurred with high frequency. From June to August 2022 none of lineages was dominant and they were noted with similar frequency.

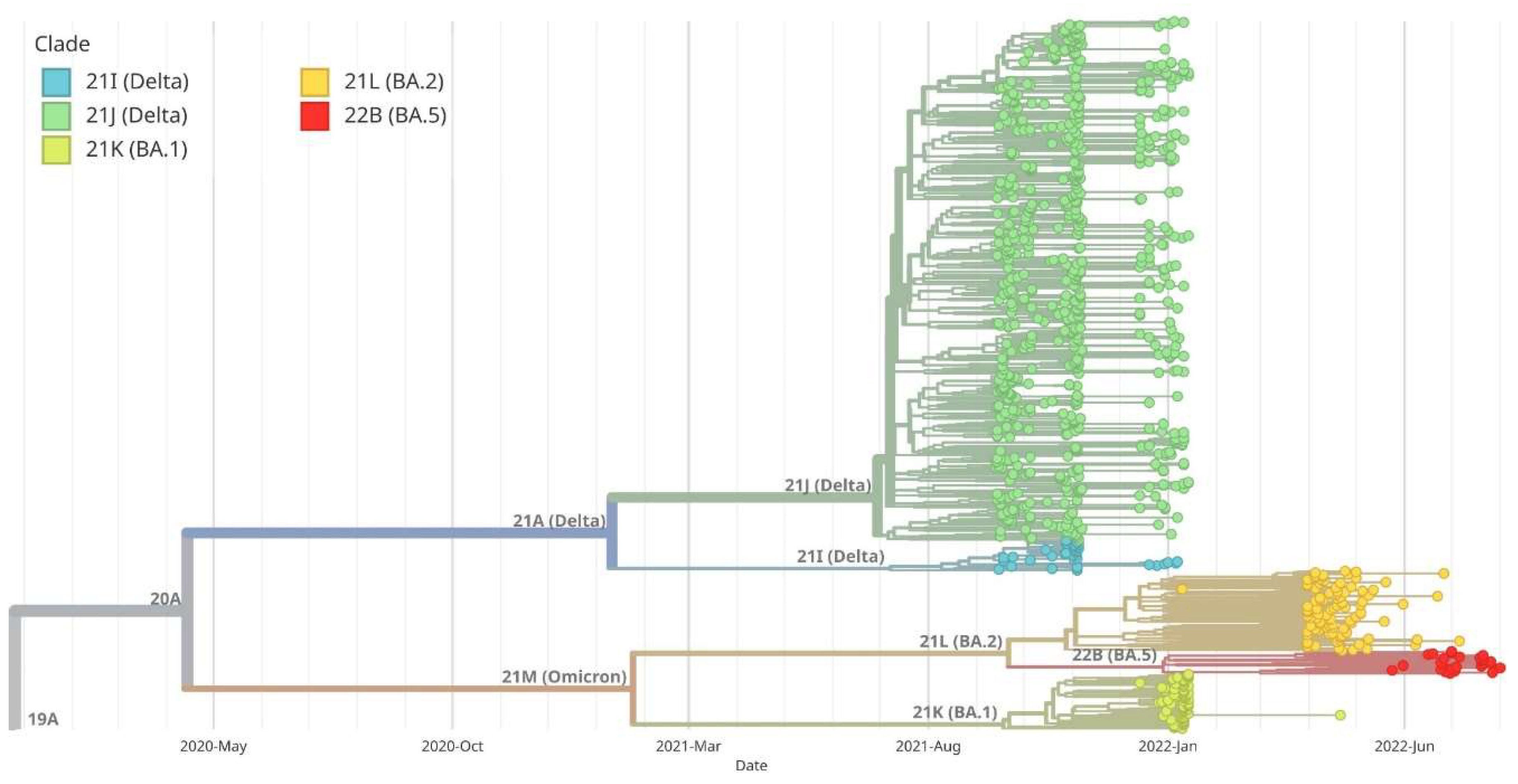

Figure 6.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Southern Poland. The branches corresponding to the five primary clades are highlighted in blue, dark green, light green, orange and red. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. The variant 21J (Delta) has definitely dominated in Poland since August 2021, while the 21M (Omicron) variant began to displace the 21J in January 2022. Initially, it was the BA.1 variant gradually replaced by a BA.2 variant and then a BA.5 variant.

Figure 6.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Southern Poland. The branches corresponding to the five primary clades are highlighted in blue, dark green, light green, orange and red. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. The variant 21J (Delta) has definitely dominated in Poland since August 2021, while the 21M (Omicron) variant began to displace the 21J in January 2022. Initially, it was the BA.1 variant gradually replaced by a BA.2 variant and then a BA.5 variant.

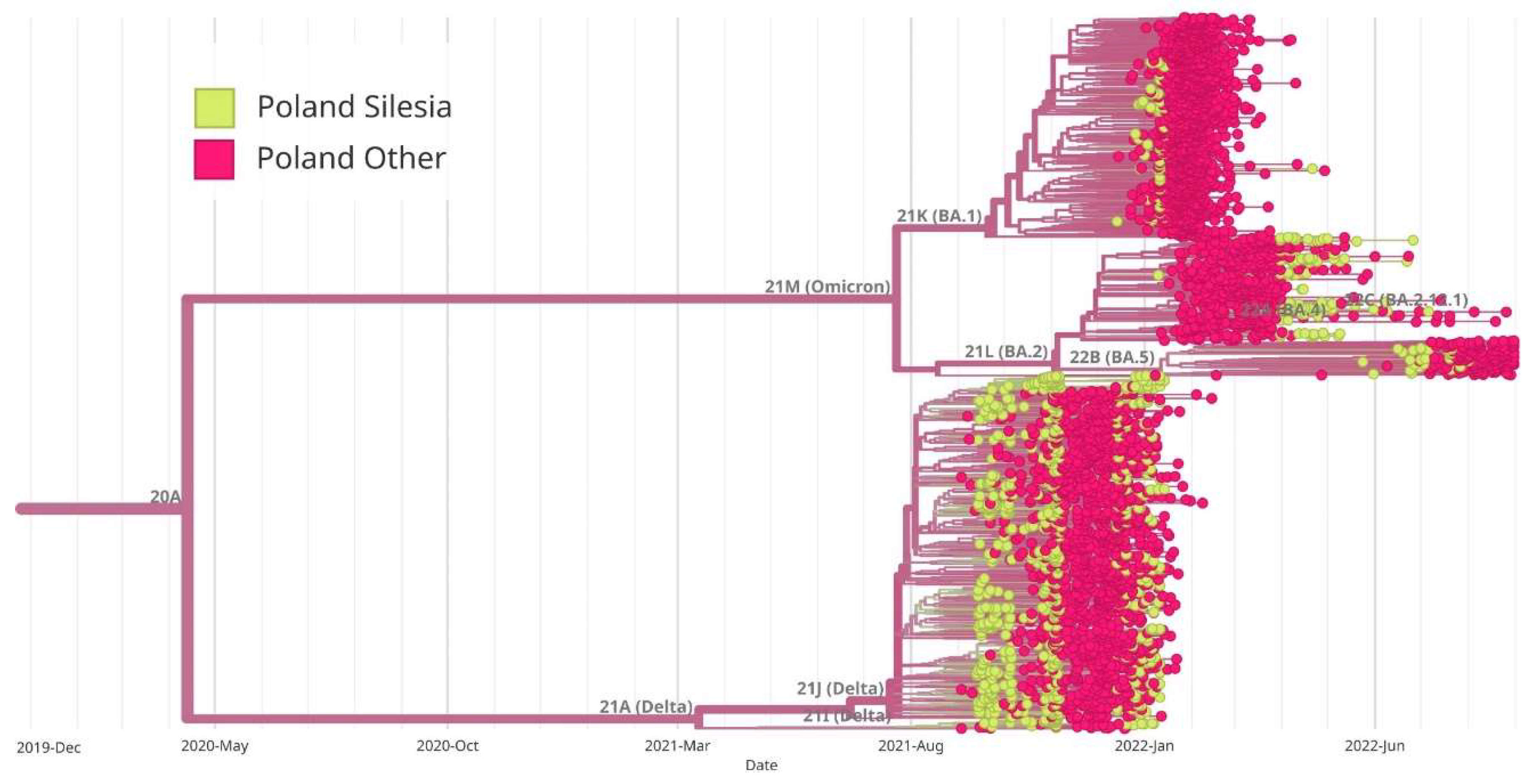

Figure 7.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia within the broader context of Poland. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in green, while those corresponding to the rest of the country are marked in red. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared earlier in Silesia than in the rest of the country, while BA.1 variant (Omicron) began to appear at the same time both in Silesia and throughout Poland. On the other hand, BA.2 variant appeared earlier in other regions of Poland, and later in Silesia. The BA.5 variant dominated Silesia earlier than the rest of Poland.

Figure 7.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia within the broader context of Poland. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in green, while those corresponding to the rest of the country are marked in red. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared earlier in Silesia than in the rest of the country, while BA.1 variant (Omicron) began to appear at the same time both in Silesia and throughout Poland. On the other hand, BA.2 variant appeared earlier in other regions of Poland, and later in Silesia. The BA.5 variant dominated Silesia earlier than the rest of Poland.

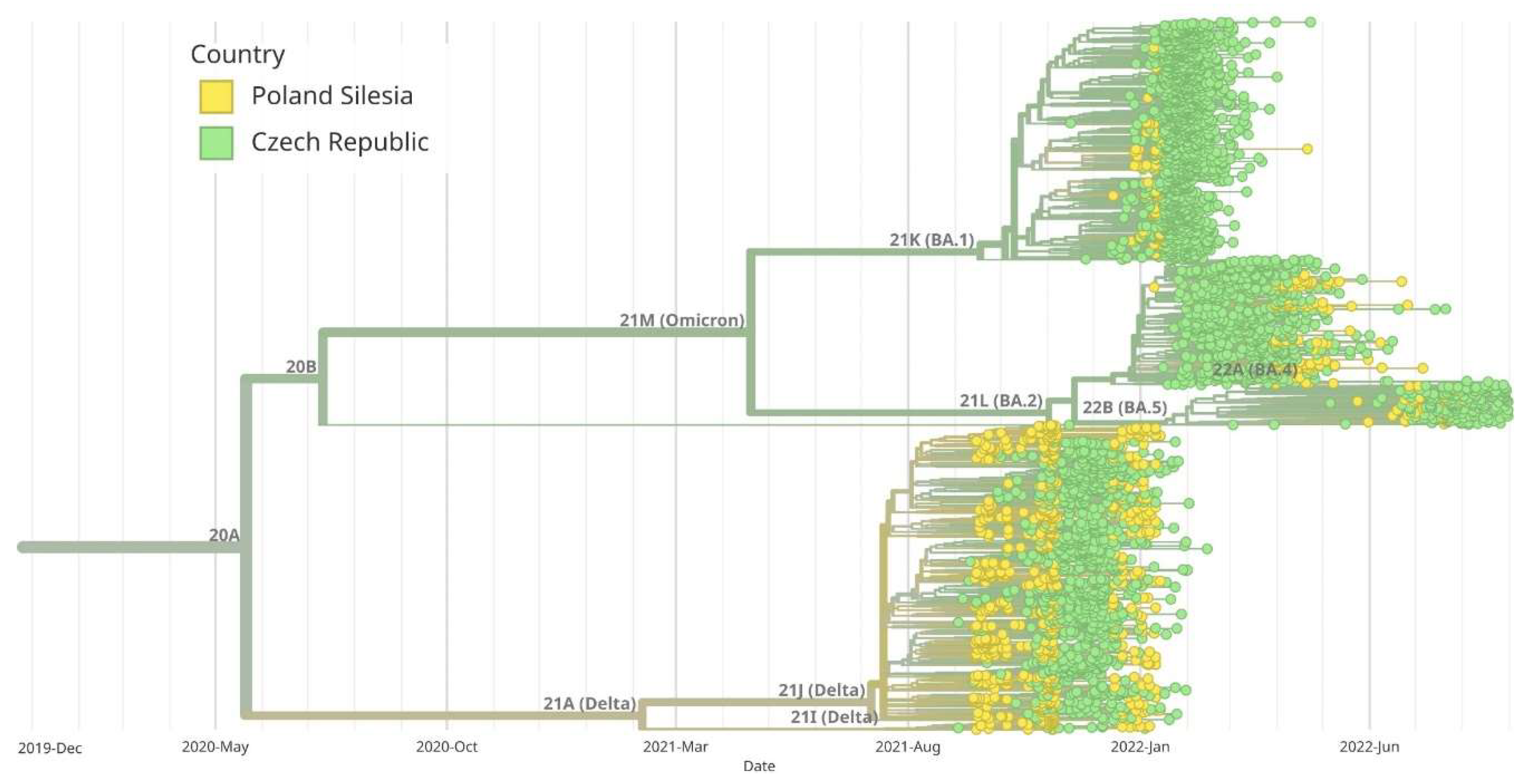

Figure 8.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia comparing to Chech Republic. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in yellow, while those corresponding to the Czech Republic are marked in green. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared earlier in Silesia than in the Czech Republic. BA.1 and BA.5 variants began to appear at the same time both in Silesia and Czech Republic, while BA.2 variant (Omicron) dominated the Czech Republic earlier than Silesia.

Figure 8.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia comparing to Chech Republic. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in yellow, while those corresponding to the Czech Republic are marked in green. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared earlier in Silesia than in the Czech Republic. BA.1 and BA.5 variants began to appear at the same time both in Silesia and Czech Republic, while BA.2 variant (Omicron) dominated the Czech Republic earlier than Silesia.

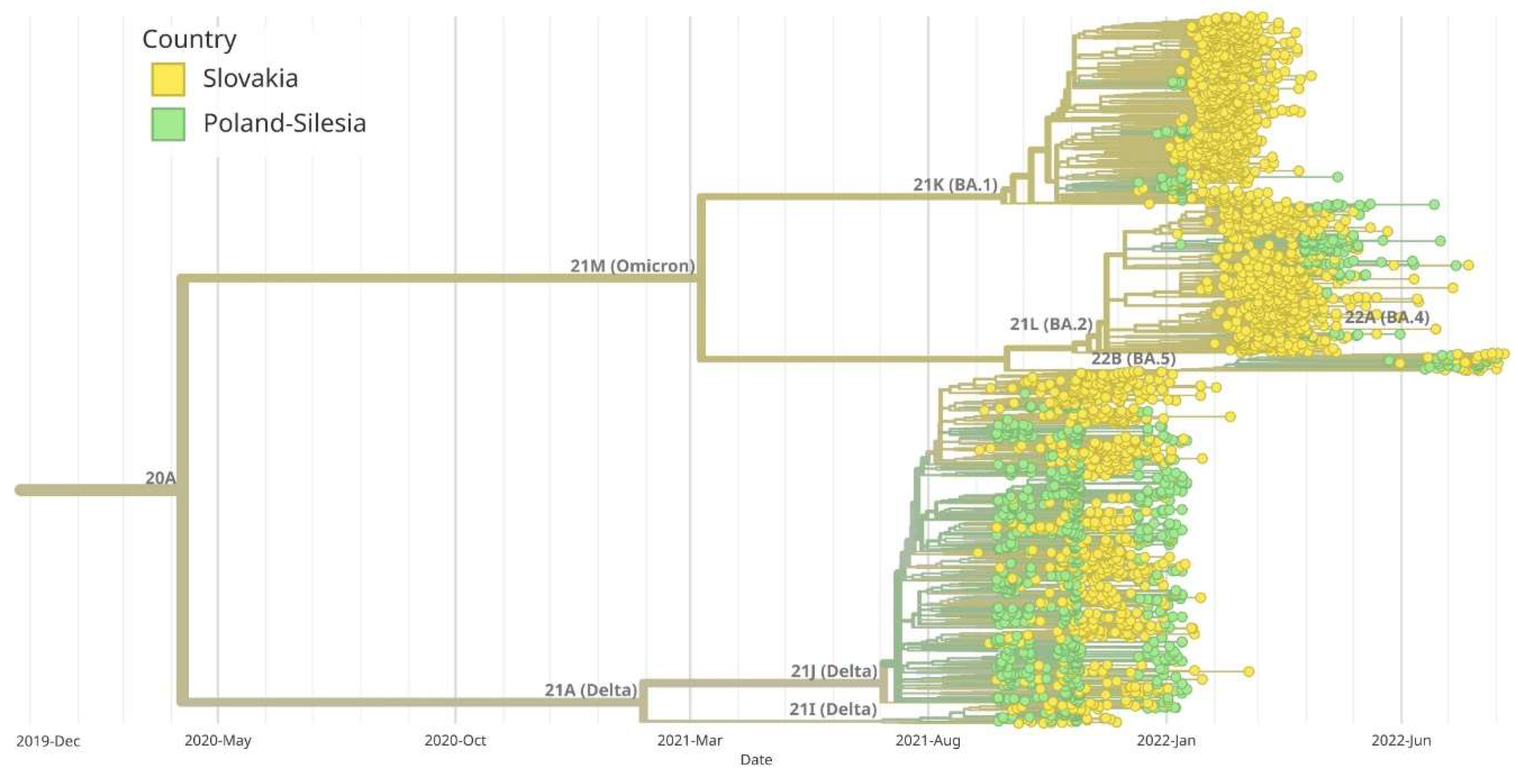

Figure 9.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia comparing to Slovakia. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in green, while those corresponding to the Slovakia are marked in yellow. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared at the same time in Silesia and Slovakia. BA.1 and BA.5 variants began to appear earlier in Silesia than in Slovakia, while BA.2 variant dominated the Slovakia earlier than Silesia.

Figure 9.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences in Silesia comparing to Slovakia. Variants corresponding to Silesia are marked in green, while those corresponding to the Slovakia are marked in yellow. Virus variants were classified using the Nextstrain lineage systems. Variant 21A (Delta) appeared at the same time in Silesia and Slovakia. BA.1 and BA.5 variants began to appear earlier in Silesia than in Slovakia, while BA.2 variant dominated the Slovakia earlier than Silesia.

Figure 10.

Daily number of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases per 100 000 inhabitants.

Figure 10.

Daily number of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases per 100 000 inhabitants.

Figure 11.

Weekly percentage of SARS-CoV-2 reinfected patients.

Figure 11.

Weekly percentage of SARS-CoV-2 reinfected patients.