1. Introduction

Bacterial infections have always threatened the health of all human beings[

1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 2.2 million people die from wound infections every year[

2]. Antibiotics are the first-line drugs for treating these infections[

3]. However, the misuse and overuse of antibiotics has led to the emergence of bacterial resistance, which poses a deadly threat to humans[

4,

5,

6]. Many other antimicrobial agents such as quaternary ammonium salts (QAS), metal ions[

7], antimicrobial peptides, graphene oxide (GO) flakes, and nitric oxide (NO) have been gradually developed and have shown excellent antimicrobial effects[

8]. However, they have some shortcomings.QAS is prone to bacterial resistance, metal ions and oxides have broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, but the uncontrolled release of ions and significant cytotoxicity limit the wide application of these materials. Therefore, it is important to develop a new antimicrobial strategy. Examples include antimicrobial therapies based on bioactive materials, photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT). Among these approaches, PTT, as a novel therapeutic technique with high biocompatibility and medical efficiency, is considered a safe and effective strategy for the treatment of bacterial infections[

9]. It utilizes materials with high photothermal conversion efficiency to generate enough heat to kill bacteria under near-infrared (NIR) light irradiation[

10].

Polydopamine (PDA) nanoparticles are a potential antimicrobial material due to their excellent photothermal conversion properties, unique antimicrobial ability and simple green preparation process[

11,

12,

13]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that PDA can rapidly convert light energy into heat energy under near-infrared light irradiation, a property that shows great potential for application in the field of photothermal therapy (PTT). In addition, the surface of PDA is rich in catechol groups[

14]. These reactive groups enable it to interact with a variety of biomolecules to form nanocomposite particles capable of killing bacteria with photothermal therapy. For example, Li et al.[

15] linked PDA NPs with thiolated polyethylene glycol (PEG) and MagI (an antimicrobial peptide) to improve the stability and bacterial interaction ability of PDA NPs, respectively.The formation of PDA occurs through the oxidative polymerization of dopamine (DA)[

16]. However, PDA tends to aggregate and form further precipitates from solution[

17,

18]. To overcome these problems, hyaluronic acid graft-modified polydopamine nanoparticles were used to improve the stability of PDA NPs. Hyaluronic acid (HA), as a linear polymeric polysaccharide, contains a large number of hydrophilic hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups on its molecular chain, which can undergo Michael addition reaction with the amine groups in polydopamine[

19,

20].

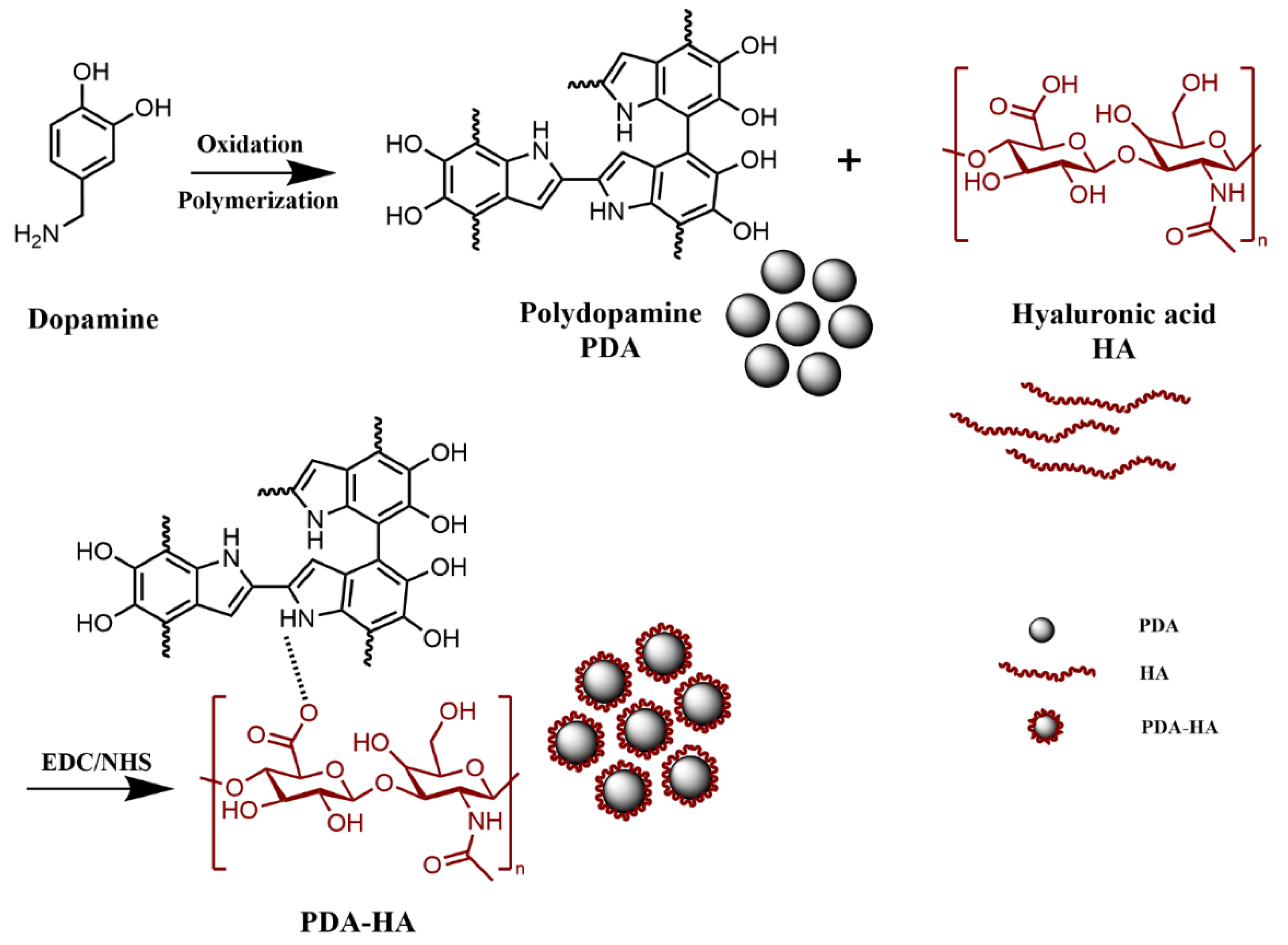

Based on this, in this study, dopamine and hyaluronic acid were used as raw materials, and hyaluronic acid (HA) was grafted onto polydopamine (PDA) nanoparticles by self-polymerization and Michael addition reactions under alkaline conditions, thus obtaining PDA-HA modified nanoparticles. This modified nanoparticles not only improved the stability of polydopamine nanoparticles, but also exhibited high photothermal conversion efficiency under near-infrared light (NIR) excitation, with significant antimicrobial effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

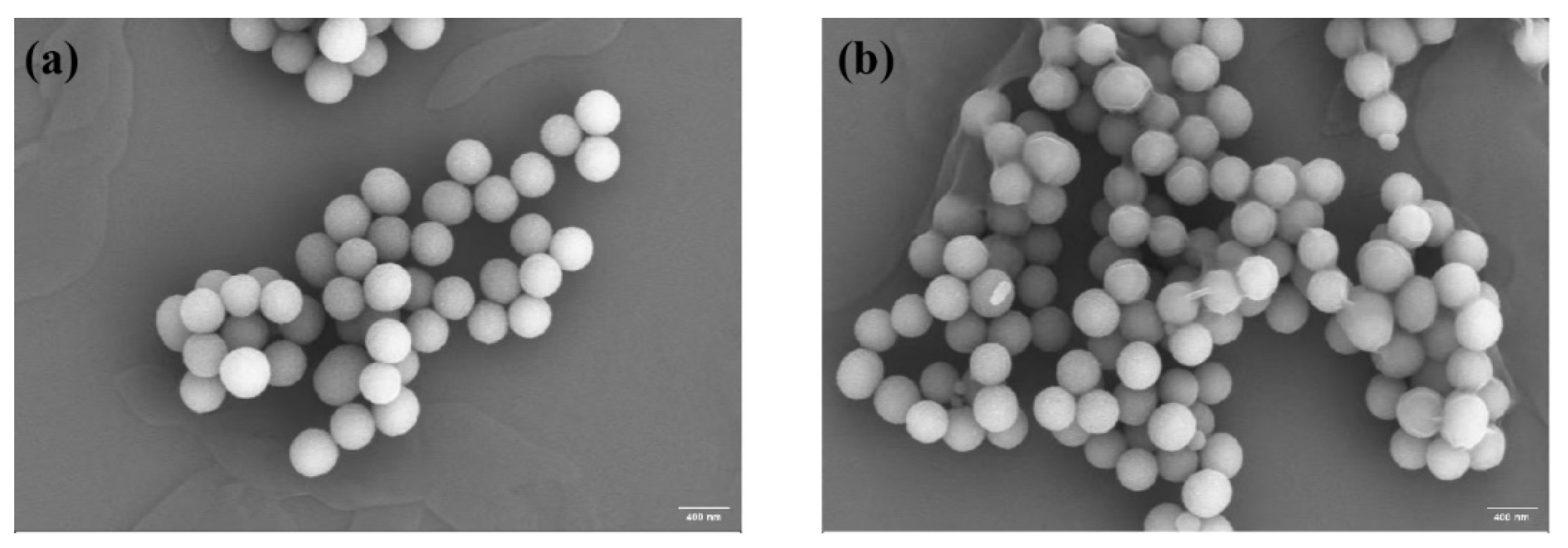

By scanning electron microscope image analysis, the average particle size of PDA was about 352 nm, the shape was spherical and uniformly distributed (

Figure 3a), the surface was relatively smooth, and some of the particles might be slightly agglomerated.PDA-HA had a monodispersed spherical shape, and the average particle size was about 400 nm (

Figure 3b).

2.2. Preparation of Hyaluronic Acid Graft-Modified Polydopamine (PDA-HA) Nanoparticles

Preparation of PDA-HA: Add 1 g of HA and 100 ml of deionized water in the reactor, put it on the magnetic stirrer to make it dissolve completely, add 1.50 g of EDC and 0.91 g of NHS and stir for 2 h, add 1.42 g of DA at 600 r/min for 12 h, add ammonia to adjust the pH to 8~9, stir for 24 h away from the light and centrifugation (13 000 rpm, 15 min) to remove the supernatant. 15 min) to remove the supernatant, centrifugation (13 000 rpm, 15 min) with deionized water for 3 times to remove the unreacted DA, poured into the polypropylene cap, and dried at 60 ℃ for 15 h to obtain PDA-HA.

Figure 1.

Preparation process of PDA-HA.

Figure 1.

Preparation process of PDA-HA.

2.3. Characterization of Materials

The chemical functional groups of DA, HA, PDA and PDA-HA were verified using an attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (ATR-FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific).DA, HA, PDA and PDA-HA were pre-dried for 24 h. The infrared spectra were tested in the range of 4000~500 cm−1. A British Renishaw’s Invia Raman microscope Raman spectrometer was used for Raman spectral analysis with a scanning range of 4000~500 cm−1. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV 400 NMR instrument. PDA and PDA-HA were observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM, Nova NanoSEM450). The sample solutions were diluted with distilled water, sonicated for 5 min, and the particle size and zeta potential were determined using a highly sensitive nanoparticle size analyzer, Zetasizer Nano ZS90 from Malvern Instruments, U.K. The samples were tested three times for each sample, and the average values were taken. The absorption peaks of the samples were determined using a UV-2450 UV spectrophotometer from Shimadzu, Japan, with a scanning wavelength of 230~350 nm.

2.4. NIR Performance Evaluation

The photothermal properties of the materials were evaluated by using an infrared thermal imager (FLIR T620) to monitor in real time the temperature changes of each group of samples under irradiation with a near-infrared (NIR) laser. The samples in each group were irradiated with a near-infrared (NIR) laser (808 nm, 2.0 W/cm2) for 20 min, during which time the temperature changes were recorded using an infrared thermography camera at 1 min intervals, and the warming curves were plotted. In addition, the photothermal stability was evaluated by repeated irradiation of PDA-HA with a NIR laser (808 nm, 2.0 W/cm2).

2.5. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties

In this study, the antimicrobial properties of the materials were evaluated using colony counting method. Typical Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and Gram-negative bacteria E. coli were selected as representative strains. The antimicrobial capacity of each group of samples (saline group, PDANPs group and PDA-HANPs group) under different treatment conditions against S. aureus and E. coli was evaluated by the plate coating method. The samples sterilized by UV irradiation were thoroughly mixed with 700 μL of S. aureus or E. coli bacterial solution (1×10

4 CFU/mL), respectively, and then subjected to the following two treatments for 20 min: darkness and 808 nm NIR light (2.0 W/cm

2). Subsequently, 50 μL of the bacterial suspension was inoculated onto LB solid agar culture plates and evenly coated, and then incubated in an oven at 37 ℃ for 24 h. Photographs were taken to record the growth of bacterial colonies and counted. The results of five times of the same set of samples were averaged. The antimicrobial rate R can be calculated using Equation (1):

Where: NC and N are the number of colonies on the control (saline group) and experimental samples (PDA group, PDA-HA group, PDA/NIR and PDA-HA/NIR group), respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Structure Analysis

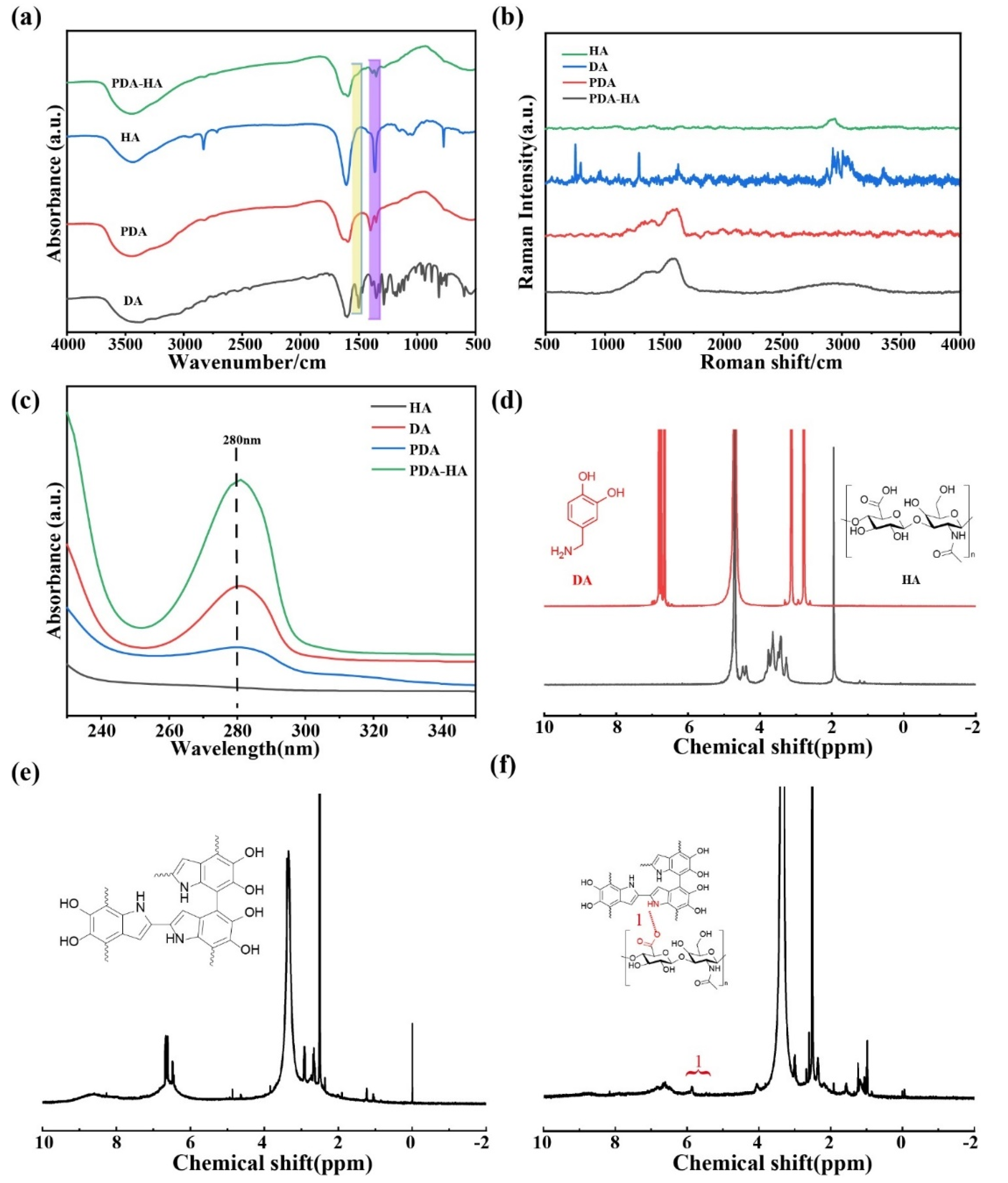

The FT-IR spectra of DA, HA, PDA and PDA-HA are shown in

Figure 2a. The absorption peak of pure HA appeared at 1607 cm

−1, which represented the asymmetric stretching peak of the carboxyl group.DA had several characteristic absorption peaks in the IR spectrum, and the broad absorption peaks near 3500-3200 cm

−1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (-OH) and amino (-NH₂) groups.PDA NPs showed a broad peak for the O-H bond on the aromatic ring near 3420 cm

−1, the characteristic peaks at 1630 and 1510 cm

−1 belonging to the stretching vibration of C=O and the bending vibration peak of N-H, respectively, demonstrating the successful synthesis of PDA[

21].Since HA itself contains an amide group, as well as HA is grafted onto the amino group of PDA by amide condensation, the amide bond is the focus of examining the success of HA grafting.However, the characteristic peak of the amide band that should have appeared at 1680-1630 cm

−1 overlapped with the characteristic peak of the benzene ring in the PDA, and a distinct characteristic peak of the amide second band appeared at 1570-1510 cm

−1[

12,

22]. In addition, the absorption peaks at 1210 cm

−1 and 1050 cm

−1 were the O-H deformation vibration peaks of secondary alcohols and the C-O stretching vibration peaks of saturated secondary alcohols, respectively. Accordingly, the appearance of the above HA-specific absorption peaks proved that HA was introduced on the surface of PDA, and the intensity of the corresponding characteristic absorption peaks (1351 cm

−1 and 1396 cm

−1) of PDA was relatively weakened in the HA-modified samples, which also proved that the modification of the surface of PDA by HA was more homogeneous and complete.

The Raman spectra of HA, DA, PDA and PDA-HA were analyzed and the results are shown in

Figure 2b. From

Figure 2b, two characteristic peaks of PDA can be seen, corresponding to the D band at 1352 cm

−1 and the G band at 1580 cm

−1[

23,

24,

25]. These two absorption peaks belong to the standard characteristic peaks of polydopamine, thus indicating that DA has been successfully synthesized as PDA.The Raman spectrum of HA with a strong absorption peak at 2938 cm

−1 can be attributed to the -OH stretching vibration of the alcohol chelates, whereas the appearance of new peaks at 2500-3200 cm

−1 for PDA-HA suggests that HA may be grafted onto PDA[

26,

27].

The UV-vis characterization of HA, DA, PDA and PDA-HA is shown in

Figure 2c. From the figure, it can be seen that HA has no absorption peaks between 230 and 350 nm, while DA shows a distinct characteristic absorption peak at 280 nm, which corresponds to the catechol structure on DA and is in accordance with the literature reports[

28].The characteristic absorption peaks of PDA are concentrated at 279 nm, and there are no other peaks in the NIR region[

29]. Similarly, PDA-HA showed a distinct absorption peak at 280 nm, suggesting possible grafting of HA on PDA.

The chemical structures of HA, DA (

Figure 2d), PDA (

Figure 2e) and PDA-HA (

Figure 2f) were characterized by

1H NMR spectroscopy, and the

1H NMR spectra of PDA-HA showed the presence of catechol aromatic proton peaks at chemical shifts of 6.65, 6.75, and 6.80 ppm, as well as catechol methylidene proton peaks at 3.1 and 2.8 ppm, and a catechol methylidene proton peak at the chemical shift at The methyl proton peak of HA was present at 1.9 ppm[

30,

31,

32,

33]. In addition, a new proton peak (-CH=N-) appeared at 5.84 ppm in the

1H NMR spectra of PDA-HA, proving the successful preparation of PDA-HA.

3.2. Microscopic Morphology Analysis

By scanning electron microscope image analysis, the average particle size of PDA was about 352 nm, the shape was spherical and uniformly distributed (

Figure 3a), the surface was relatively smooth, and some of the particles might be slightly agglomerated.PDA-HA had a monodispersed spherical shape, and the average particle size was about 400 nm (

Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) SEM image of PDA; (b) SEM image of PDA-HA.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM image of PDA; (b) SEM image of PDA-HA.

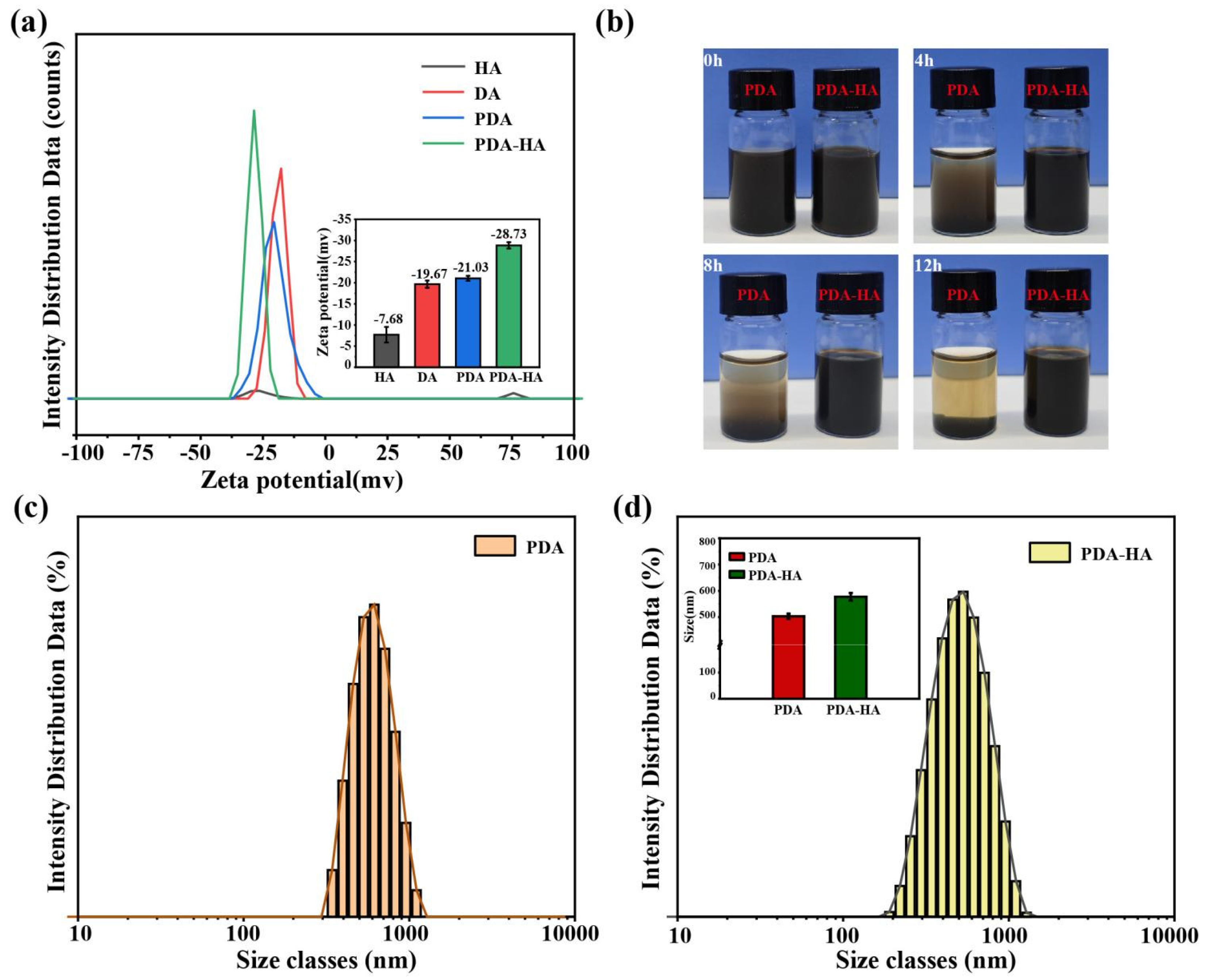

3.3. Surface and Stability Analysis

Surface modification of hydrophilic HA improves the water stability of NPs. To test this, we prepared PDA and PDA-HA solutions with deionized water. As shown in

Figure 4b, the PDA settled rapidly within 4 h. The PDA-HA solution was not stable at all. In contrast, we did not observe the settling of PDA-HA during the same time period. We even extended the experimental time to 12 h and still did not observe PDA-HA settling. Thus, we verified that PDA-HA is stable in aqueous solution and has better dispersion, which is useful for subsequent experiments.

Particle size and zeta potential determine the in vivo distribution, bioavailability, cytotoxicity and targeted delivery of nanosystems. Therefore, particle size and zeta potential of PDA-HA and PDA were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The particle size and zeta potential of PDA-HA changed significantly compared with pure PDA.The zeta potential of PDA-HA gradually increased from -21.03 mV to -28.03 mV (

Figure 4a) because of the negative charge of HA (

Figure 2d). After modifying HA, the particle size of NPs increased from 503 nm to 577 nm (

Figure 4d). In summary, it was shown that the particle size and zeta potential of the particles were significantly increased after hyaluronic acid graft-modified polydopamine nanoparticles.

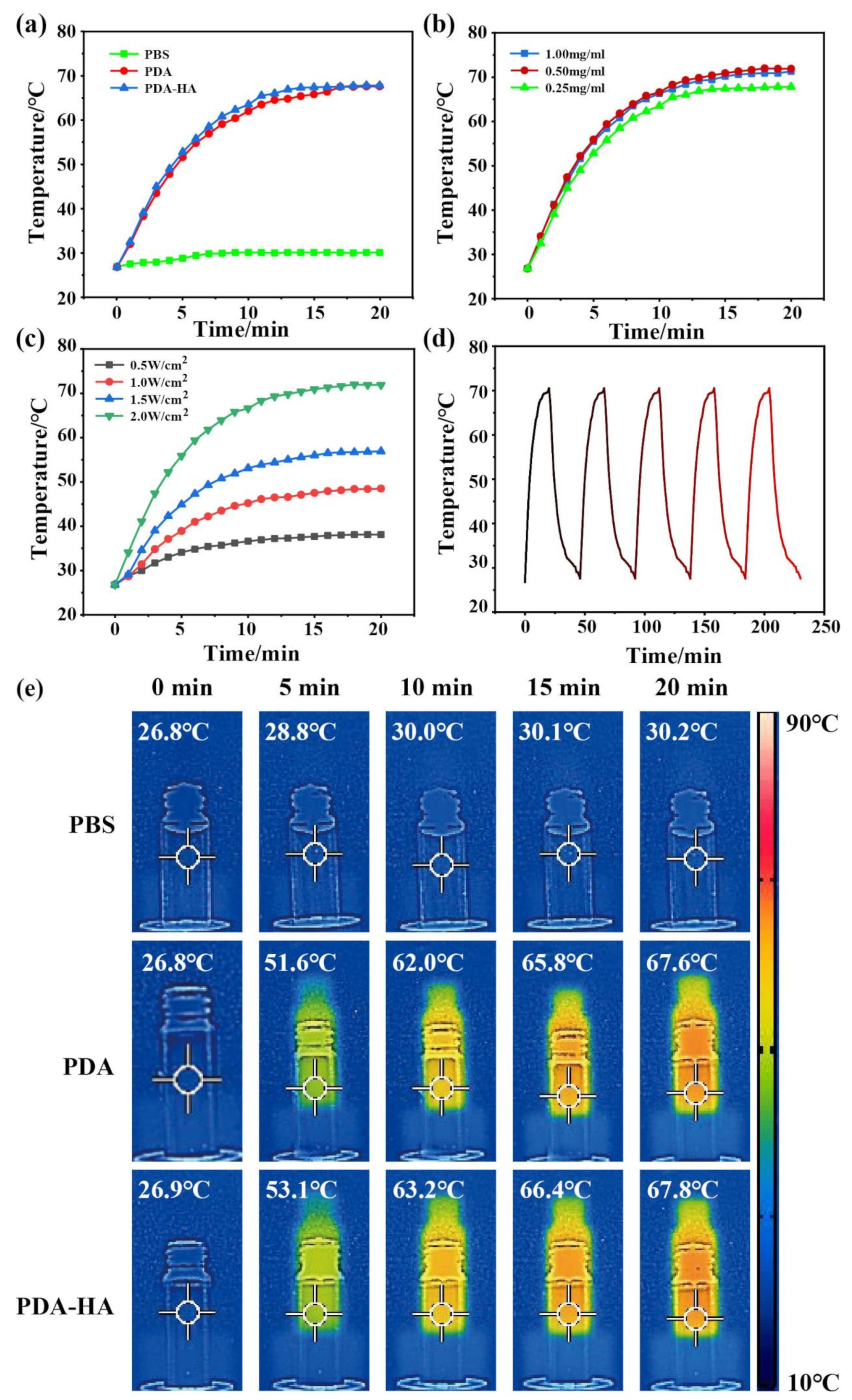

3.4. Evaluation of the Near Infrared Performance of PDA-HA

It was shown that PDA has good photothermal properties and can efficiently convert light energy into heat energy when irradiated with near-infrared light. Therefore, the photothermal properties of PDA and PDA-HA were evaluated to verify the potential of PDA-HA as a NIR-responsive material. The PDA solution (1 mg/ml) and PDA-HA (1 mg/ml) solution were irradiated with 808 nm, 2 W/cm2 NIR light to produce thermal effects. Under the same irradiation conditions, the temperature of pure saline (control) did not change significantly, whereas the temperature of PDA (1 mg/ml) solution and PDA-HA (1 mg/ml) solution increased gradually with irradiation time (

Figure 5a). Different concentrations of PDA-HA solutions (1, 0.5, 0.25 mg/ml) irradiated with 808 nm, 2 W/cm2 NIR light for 20 min showed no significant change in the final temperature (

Figure 5b), and their photothermal effect increased with the increase of 808 nm laser power density (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2 W/cm2) (

Figure 5c).The PDA and PDA- HA photothermal effects Under the same irradiation and concentration conditions, the final temperature of the PDA solution was 67.6 ℃, while that of the PDA-HA solution was 67.8 ℃ (

Figure 5e), and the experimental results showed that PDA grafted with HA does not greatly affect the photothermal effect of PDA, and photothermal imaging also proved this conclusion (

Figure 5e). Meanwhile, a solution containing 1 mg/ml PDA-HA was irradiated with near-infrared light (808 nm, 2 W/cm2) for 20 min, and then the solution was allowed to naturally cool down to room temperature, and the photothermal ability did not change significantly after five consecutive irradiations (

Figure 5d), so that the PDA-HA can be used as excellent near-infrared photoresponsive material.

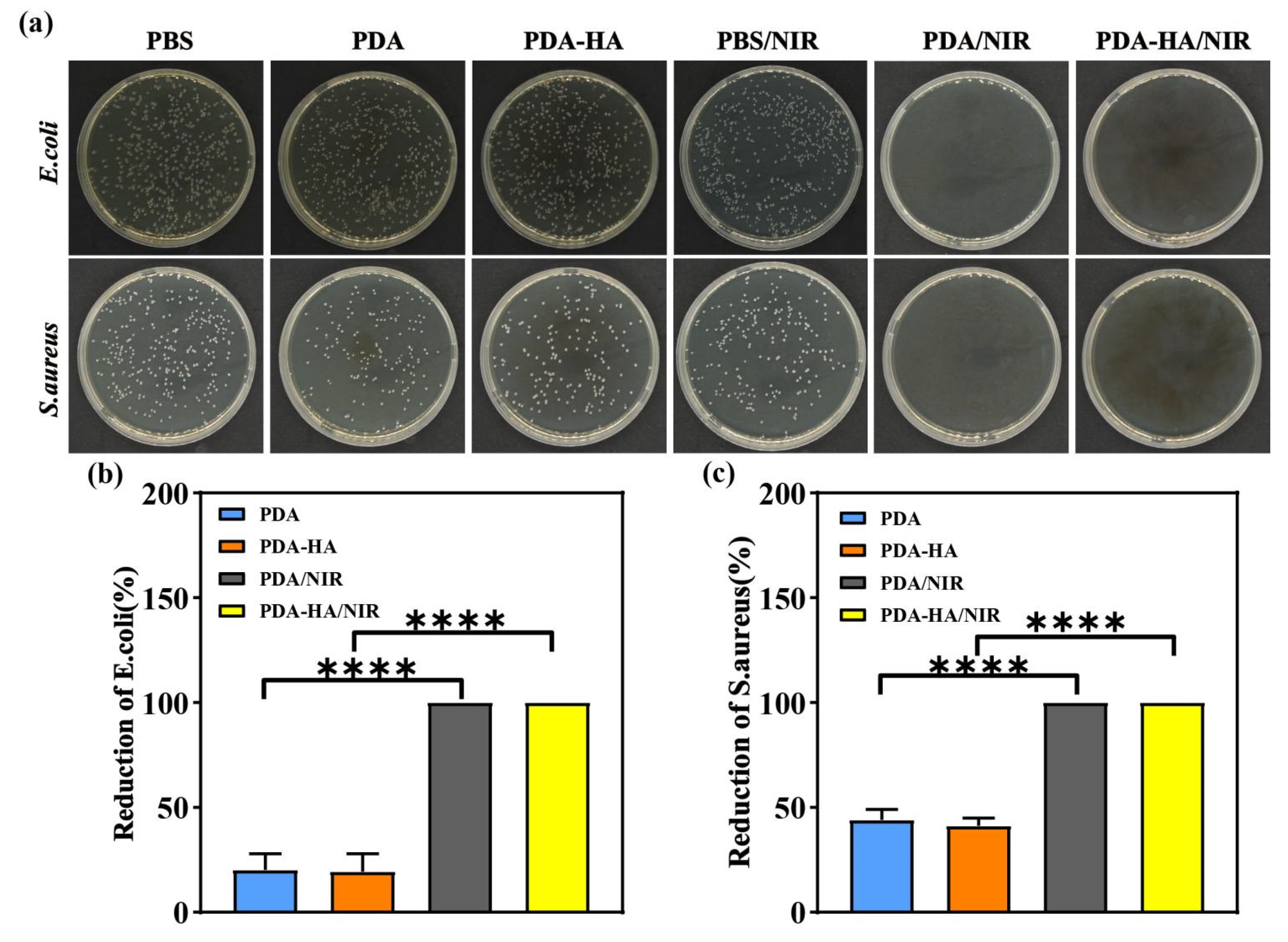

3.5. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties of PDA-HA

In this study, the antimicrobial properties of the samples from each group were evaluated using the dilution-coated plate method using S. aureus and E. coli as representative pathogenic bacteria models. As shown in

Figure 6 a, under dark conditions, a large number of S. aureus and E. coli were visible on the agar plates of the saline group, whereas the density of colonies in the media corresponding to the PDA and PDA-HA groups was lower than that corresponding to the PBS group, which may be attributed to the fact that the polydopamine disrupts the cell membranes of the bacteria through the production of free radicals, leading to the death of the bacteria[

34]. After the introduction of NIR light, the antimicrobial performance of the PBS group was not significantly improved, and a large number of colonies still existed on the surface. Notably, the PDA and PDA-HA groups showed no bacterial growth under NIR light irradiation and exhibited significant antibacterial effects with 100% antibacterial rate, which was attributed to the fact that under NIR irradiation, PDA could efficiently absorb the energy of the NIR light and convert it into heat, which led to a rapid increase in the temperature of the surroundings and thus killed the bacteria. In conclusion, the results of the antibacterial experiments showed that the hyaluronic acid graft-modified polydopamine nanoparticles had excellent antibacterial properties after NIR light irradiation.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, we grafted hyaluronic acid (HA) onto polydopamine (PDA) nanoparticles by self-polymerization and Michael addition reactions under alkaline conditions to obtain PDA-HA modified nanoparticles. This modified nanoparticles were synthesized in a simple process under mild conditions. By characterizing the physicochemical properties of PDA-HA, we found that the particles have uniform particle size and good dispersion. Infrared spectroscopy analysis confirmed the successful combination of PDA and HA, showing the characteristic absorption peaks of both. In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) results further confirmed the formation of PDA-HA. It is particularly noteworthy that PDA-HA exhibited excellent photothermal conversion ability under near-infrared light irradiation and significant antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, a property that makes it potentially valuable for application in the field of photothermal therapy. In summary, PDA-HA shows great potential for application in the biomedical field, especially in photothermal therapy and antimicrobial materials, due to its excellent NIR responsiveness, antimicrobial properties and good biocompatibility. Future research will focus on further optimizing the properties of the particles and conducting more in vitro and in vivo experiments to evaluate their effectiveness and safety in clinical treatments. Although this study has achieved some results, there are still some limitations. For example, more in-depth investigation is needed for the mechanism of long-term interaction between PDA-HA and organisms in terms of performance studies, and these will be the directions that need to be paid attention to and improved in the subsequent studies.

Author Contributions

Data curation, C.W and S.L; Conceptualization, C.W; Funding acquisition, C.W; Project administration, C.W; Writing-original draft S.L; Writing-review & editing, C.W.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Doctoral Start-up Fund of Hubei Institute of Science and Technology (BK202201) and the Youth Project of Hubei Provincial Nature Fund (2022CFB755).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sethulekshmi, A.S.; Saritha, A.; Joseph, K.; Aprem, A.S.; Sisupal, S.B. MoS(2) based nanomaterials: Advanced antibacterial agents for future. J. Control. Release 2022, 348, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, A.; Dong, L.; Hou, Y.; Mu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhong, X.; Shan, G. NIR-driven multifunctional PEC biosensor based on aptamer-modified PDA/MnO(2) photoelectrode for bacterial detection and inactivation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 257, 116320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Da, J.; Wu, W.; Zheng, C.; Hu, N. Niobium carbide-mediated photothermal therapy for infected wound treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 934981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmal, G.R.; Lin, Z.C.; Chiu, T.S.; Alalaiwe, A.; Liao, C.C.; Fang, J.Y. Chemo-photothermal therapy of chitosan/gold nanorod clusters for antibacterial treatment against the infection of planktonic and biofilm MRSA. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268 Pt 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Lau, J.W.; Do, T.C.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, B. Near-Infrared Light Brightens Bacterial Disinfection: Recent Progress and Perspectives. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 3937–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wang, R.; Fan, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y. Natural polyphenol assisted delivery of single-strand oligonucleotides by cationic polymers. Gene Ther. 2020, 27, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zheng, J. Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles: Structural Effects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1701503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, N.D.; Ouimet, M.A.; Uhrich, K.E. Antibiotic-containing polymers for localized, sustained drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 78, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Yao, K.; Xu, Z.K. Nanomaterials with a photothermal effect for antibacterial activities: an overview. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 8680–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overchuk, M.; Weersink, R.A.; Wilson, B.C.; Zheng, G. Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapies: Synergy Opportunities for Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7979–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Huang, Y.; You, S.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, E.; Mao, R.; Pan, W.; Tong, X.; Dong, W.; Ye, F.; et al. Engineering Robust Ag-Decorated Polydopamine Nano-Photothermal Platforms to Combat Bacterial Infection and Prompt Wound Healing. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y. A multi-responsive targeting drug delivery system for combination photothermal/chemotherapy of tumor. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2023, 34, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, P.; Liang, G.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Li, Y. Regulating the absorption spectrum of polydopamine. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhurakkat, P.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.B.; Shin, Y.M.; Lee, E.J.; Mikos, A.G.; Shin, H. Materials from Mussel-Inspired Chemistry for Cell and Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 2541–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.L.; Li, H.Y.; Ye, W.Y.; Zhao, M.Q.; Huang, D.N.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, B.Q.; Ren, K.F.; Ji, J.; Fu, G.S. Magainin-modified polydopamine nanoparticles for photothermal killing of bacteria at low temperature. Colloid Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2019, 183, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zeng, X.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Zeng, W.; Mei, L.; Zhao, Y. Versatile Polydopamine Platforms: Synthesis and Promising Applications for Surface Modification and Advanced Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8537–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhang, C.; Guo, T.; Tian, Y.; Song, W.; Lei, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, A.; Zhang, M.; Bai, S.; et al. Hydrogel Nanoarchitectonics of a Flexible and Self-Adhesive Electrode for Long-Term Wireless Electroencephalogram Recording and High-Accuracy Sustained Attention Evaluation. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El, Y.S.; Ball, V. Polydopamine as a stable and functional nanomaterial. Colloid Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2020, 186, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetkov, P.; Zakharova, K.; Morozkina, S.; Olekhnovich, R.; Uspenskaya, M. Hyaluronic Acid: The Influence of Molecular Weight on Structural, Physical, Physico-Chemical, and Degradable Properties of Biopolymer. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Raei, M.; Hushmandi, K.; Zarrabi, A.; Voelcker, N.H.; Aref, A.R.; et al. Hyaluronic acid-based nanoplatforms for Doxorubicin: A review of stimuli-responsive carriers, co-delivery and resistance suppression. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wen, F.; Su, W. Polydopamine/tannic acid/chitosan/poloxamer 407/188 thermosensitive hydrogel for antibacterial and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.P.; Jin, M.Y.; Huang, S.; Zhuang, Z.M.; Zhang, T.; Cao, L.L.; Lin, X.Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Versatile dopamine-functionalized hyaluronic acid-recombinant human collagen hydrogel promoting diabetic wound healing via inflammation control and vascularization tissue regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 35, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaw, O.; Noon, S.A.N.; Daduang, J.; Proungvitaya, S.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Ngernyuang, N.; Daduang, S.; Shinsuphan, N.; Phatthanakun, R.; Jearanaikoon, N.; et al. DNA aptamer-functionalized PDA nanoparticles: from colloidal chemistry to biosensor applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1427229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranu, R.; Chauhan, Y.; Ratan, A.; Singh, P.K.; Bhattacharya, B.; Tomar, S.K. Biogenic synthesis and thermo-magnetic study of highly porous carbon nanotubes. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 13, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Zamanian, A.; Sahranavard, M. Mussel-inspired polydopamine-mediated surface modification of freeze-cast poly (epsilon-caprolactone) scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Biomed. Tech. (Berl). 2020, 65, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zeng, X.; Wu, B.; Zeng, Q.; Pang, W.; Tang, J. Electrochemical co-deposition of reduced graphene oxide-gold nanocomposite on an ITO substrate and its application in the detection of dopamine. Science China(Chemistry) 2017, 60, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Babadinia, P.; Shariati, F.S.; Ahangari, C.R. Synthesis and characterization of Gd(3+)-loaded hyaluronic acid-polydopamine nanoparticles as a dual contrast agent for CT and MRI scans. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, J.; Guan, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Injectable multifunctional CMC/HA-DA hydrogel for repairing skin injury. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Niu, K.; Ni, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Hyaluronic Acid-Modified Gold-Polydopamine Complex Nanomedicine for Tumor-Targeting Drug Delivery and Chemo-Photothermal-Therapy Synergistic Therapy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Su, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, K.; Xie, M.; Cai, B.; Li, J. A hyaluronic acid / chitosan composite functionalized hydrogel based on enzyme-catalyzed and Schiff base reaction for promoting wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ye, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, X. Mechanically tough, adhesive, self-healing hydrogel promotes annulus fibrosus repair via autologous cell recruitment and microenvironment regulation. Acta Biomater. 2024, 178, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Li, S.; Pei, M.; Yang, H.; Gu, S.; Tao, Y.; Ye, D.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, W.; Xiao, P. Dopamine-Modified Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Adhesives with Fast-Forming and High Tissue Adhesion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 18225–18234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.M.; Hong, G.L.; Gwak, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Jeong, J.E.; Jung, J.Y.; Park, S.A.; Park, W.H. Self-crosslinkable hyaluronate-based hydrogels as a soft tissue filler. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Duan, G.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Gu, Z. Polydopamine antibacterial materials. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 1618–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).