Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

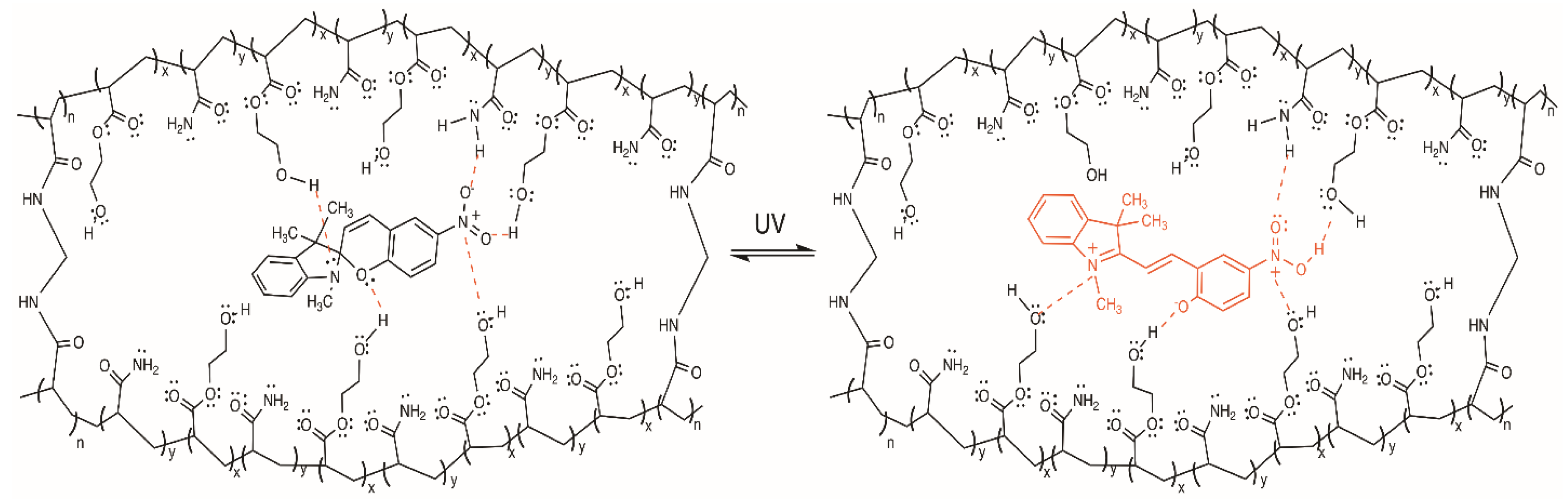

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

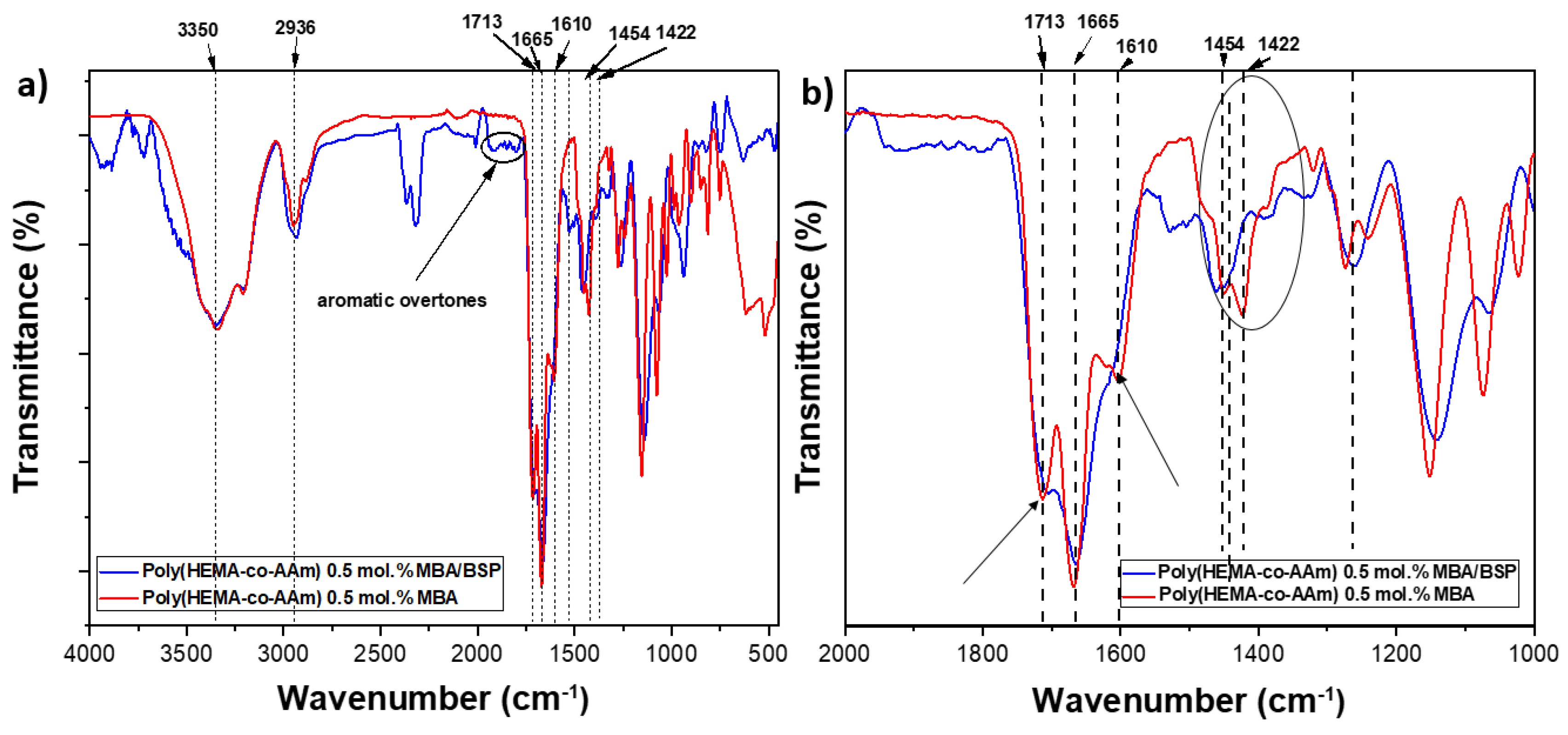

2.2. Structural Characterization by FT-IR Studies of the Hydrogels

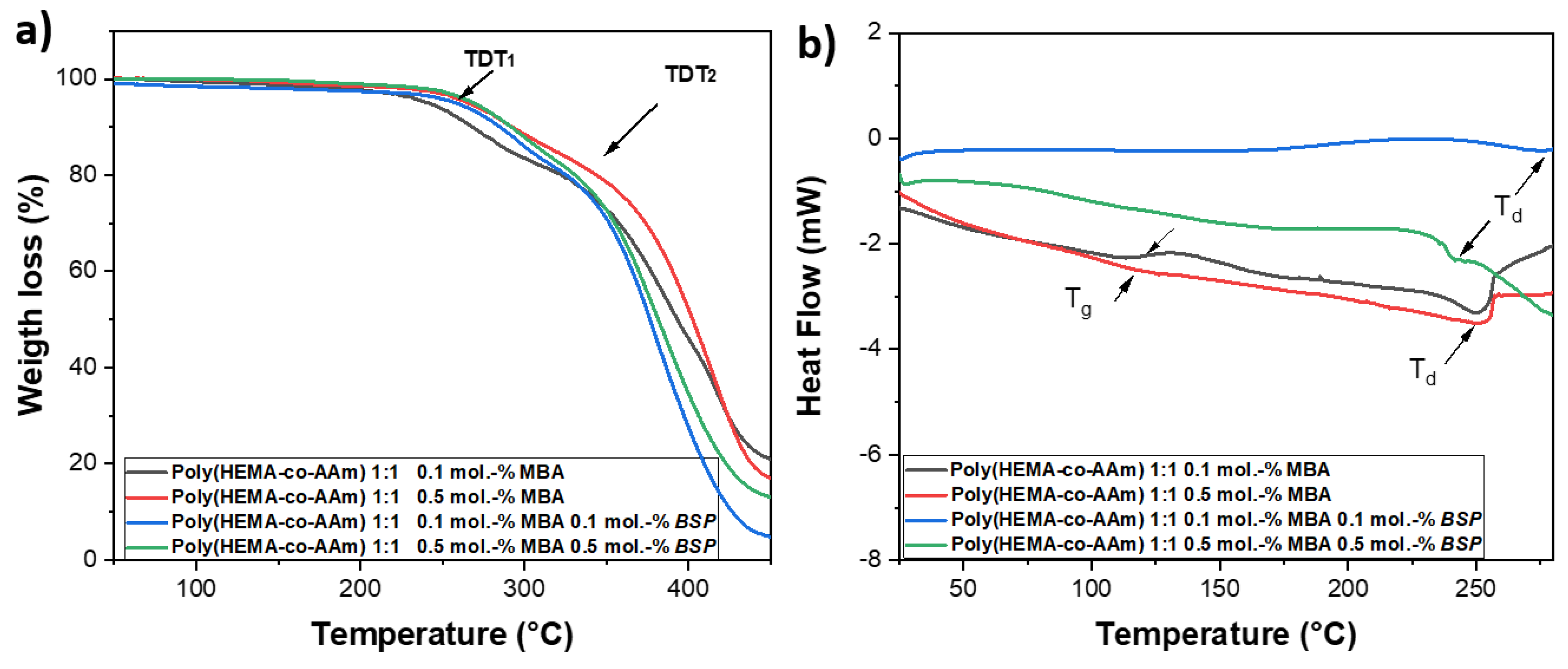

2.3. Characterization by TGA and DSC

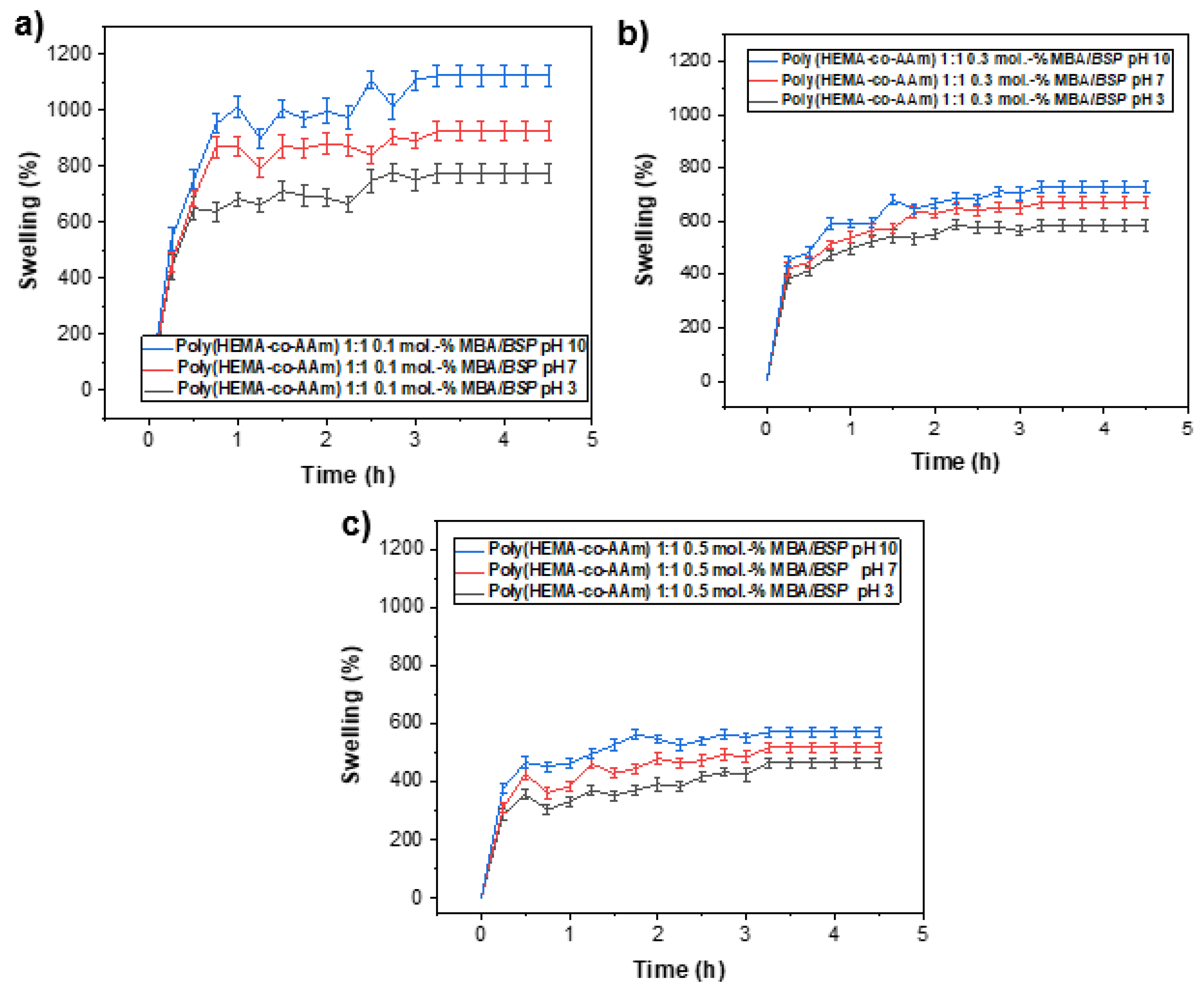

2.4. Swelling Behavior

2.5. Mechanical Properties

Lap Shear Test of Polymeric Hydrogel

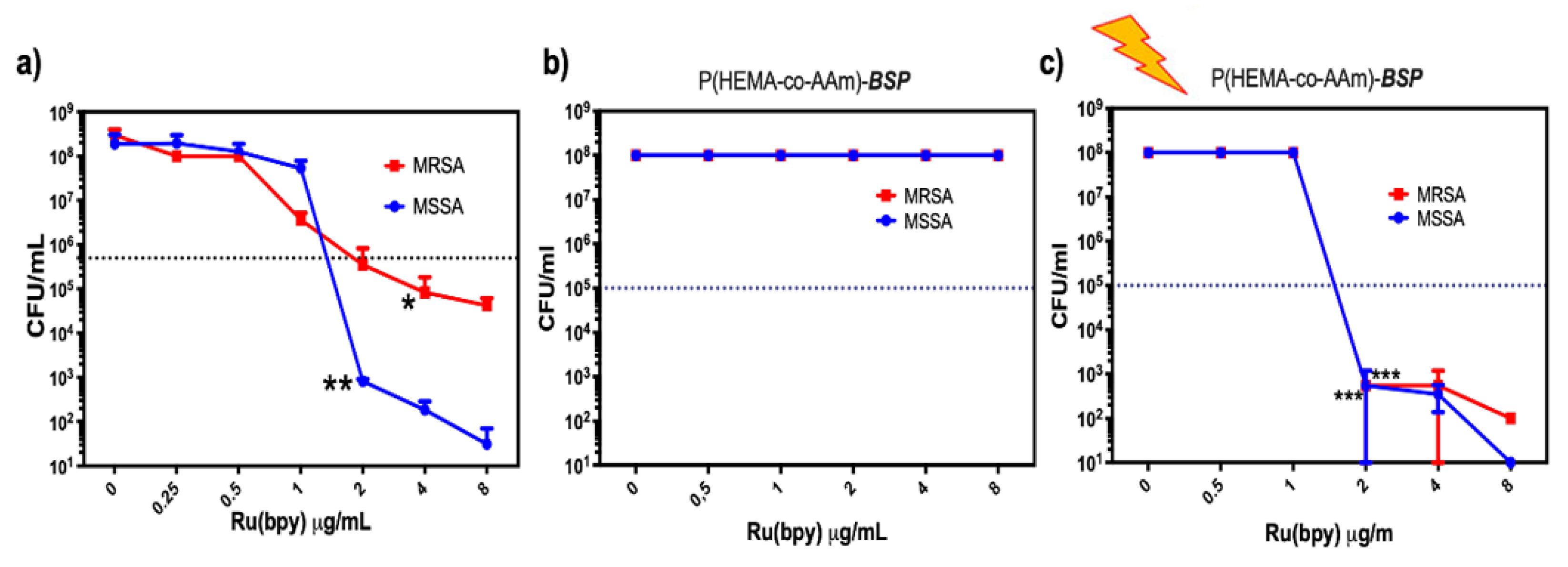

2.6. Antimicrobial Properties Based on Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

3. Conclusions

4. Experimental

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Measurement

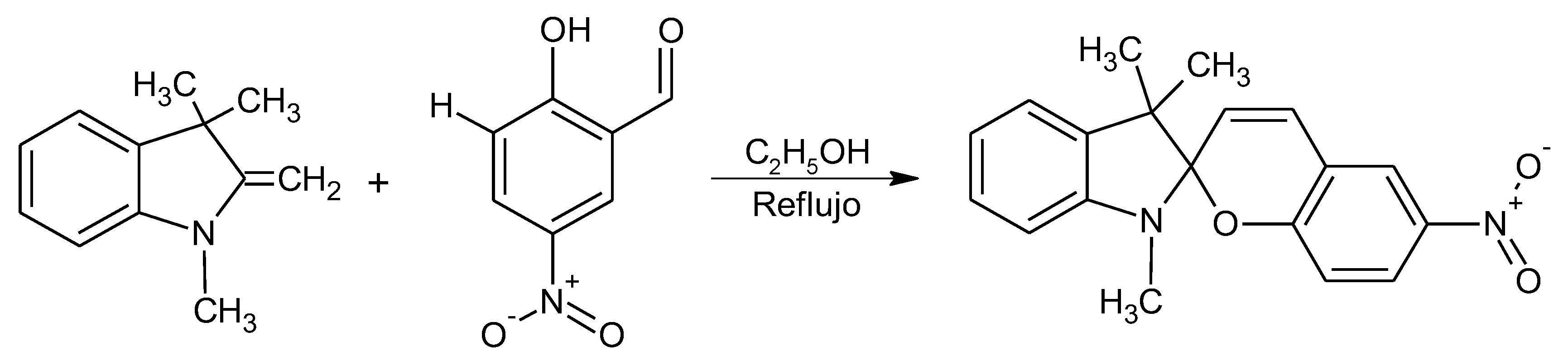

4.3. Synthesis of the 3,3-Dimethylindoline-6’-Nitrobenzospiropyran (BSP)

4.4. Hydrogel Films Preparation

4.5. Swelling Studies

4.6. Lap Shear Test Studies

4.7. Determination of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Properties

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vedadghavami, A.; Minooei, F.; Mohammadi, M. H.; Khetani, S.; Rezaei Kolahchi, A.; Mashayekhan, S.; Sanati-Nezhad, A. Manufacturing of Hydrogel Biomaterials with Controlled Mechanical Properties for Tissue Engineering Applications. Acta Biomater 2017, 62, 42–63. [CrossRef]

- Serra, L.; Doménech, J.; Peppas, N. A. Engineering Design and Molecular Dynamics of Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery Systems as Targeting Agents. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. March 2009, pp 519–528. [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, B.; Weldon, C.; Kohane, D. S. Tissue Adhesives as Active Implants; 2010; pp 39–56. [CrossRef]

- Mandell, S. P.; Gibran, N. S. Fibrin Sealants: Surgical Hemostat, Sealant and Adhesive. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014, 14 (6), 821–830. [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, N. M.; Maitra, U. Supramolecular Gels: Functions and Uses. Chem Soc Rev 2005, 34 (10), 821–836. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, A. Study on Superabsorbent Composites. IX: Synthesis, Characterization and Swelling Behaviors of Polyacrylamide/Clay Composites Based on Various Clays. React Funct Polym 2007, 67 (8), 737–745. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, M.; Rui Liang. Preparation and Properties of a Double-Coated Slow-Release NPK Compound Fertilizer with Superabsorbent and Water-Retention. Bioresour Technol 2008, 99 (3), 547–554. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C.; Sun, L.; Zhao, Y. Emerging Functional Biomaterials as Medical Patches. ACS Nano 2021, 15 (4), 5977–6007. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Kim, H. N.; Seong, M.; Lee, S.; Kang, M.; Yi, H.; Bae, W. G.; Kwak, M. K.; Jeong, H. E. Multifunctional Smart Skin Adhesive Patches for Advanced Health Care. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7 (15). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Yan, L.; Wang, K.; Han, L.; Lu, X. Infant Skin Friendly Adhesive Hydrogel Patch Activated at Body Temperature for Bioelectronics Securing and Diabetic Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2022, 16 (6), 8662–8676. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; An, S.; Ryu, Y. C.; Seo, S. H.; Park, S.; Lee, M. J.; Cho, S.; Choi, K. Adhesive Hydrogel Patch-Mediated Combination Drug Therapy Induces Regenerative Wound Healing through Reconstruction of Regenerative Microenvironment. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12 (18). [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhou, N.; Du, S.; Gao, Y.; Suo, H.; Yang, J.; Tao, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Transparent Photothermal Hydrogels for Wound Visualization and Accelerated Healing. Fundamental Research 2022, 2 (2), 268–275. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, D.; Paul, A.; Cai, L.; Enejder, A.; Yang, F.; Heilshorn, S. C. Covalently Adaptable Elastin-Like Protein–Hyaluronic Acid (ELP–HA) Hybrid Hydrogels with Secondary Thermoresponsive Crosslinking for Injectable Stem Cell Delivery. Adv Funct Mater 2017, 27 (28), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. Y.; Yeo, Y. H.; Jeong, J. E.; Park, S. A.; Park, W. H. Dual-Crosslinked Methylcellulose Hydrogels for 3D Bioprinting Applications. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 238 (January), 116192. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. E.; Carberry, B. J.; Worrell, B. T.; Dudaryeva, O. Y.; McBride, M. K.; Bowman, C. N.; Anseth, K. S. Photopolymerized Dynamic Hydrogels with Tunable Viscoelastic Properties through Thioester Exchange. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 496–503. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Yin, X.; Chen, D.; Xu, W.; Xiao, P. Photopolymerized Maleilated Chitosan/Methacrylated Silk Fibroin Micro/Nanocomposite Hydrogels as Potential Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 108, 383–390. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H.; Kim, K.; Kim, B. S.; An, Y. H.; Lee, U. J.; Lee, S. H.; Kim, S. L.; Kim, B. G.; Hwang, N. S. Fabrication of Polyphenol-Incorporated Anti-Inflammatory Hydrogel via High-Affinity Enzymatic Crosslinking for Wet Tissue Adhesion. Biomaterials 2020, 242 (January), 119905. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Duan, J.; Ma, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Z. Enzymatic Crosslinking to Fabricate Antioxidant Peptide-Based Supramolecular Hydrogel for Improving Cutaneous Wound Healing. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7 (13), 2220–2225. [CrossRef]

- Mredha, M. T. I.; Pathak, S. K.; Tran, V. T.; Cui, J.; Jeon, I. Hydrogels with Superior Mechanical Properties from the Synergistic Effect in Hydrophobic–Hydrophilic Copolymers. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 362, 325–338. [CrossRef]

- Oveissi, F.; Naficy, S.; Le, T. Y. L.; Fletcher, D. F.; Dehghani, F. Tough and Processable Hydrogels Based on Lignin and Hydrophilic Polyurethane. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2018, 1 (6), 2073–2081. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Ahuja, N.; Ma, C.; Liu, X. Injectable Scaffolds: Preparation and Application in Dental and Craniofacial Regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering R: Reports 2017, 111, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Stojkov, G.; Niyazov, Z.; Picchioni, F.; Bose, R. K. Relationship between Structure and Rheology of Hydrogels for Various Applications. Gels 2021, 7 (4). [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gilbert, S.; Castro-García, M.; Díaz-Chamorro, H.; Marambio, O. G.; Sánchez, J.; Martin-Trasancos, R.; Inostroza, M.; García-Herrera, C.; Pizarro, G. del C. Synthesis, Characterization and Catechol-Based Bioinspired Adhesive Properties in Wet Medium of Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate-Co-Acrylamide) Hydrogels. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16 (2). [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, K. Mechanical Characterisation of Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng 2008, 4 (January 2008), 1–16.

- Oyen, M. L. Mechanical Characterisation of Hydrogel Materials. International Materials Reviews 2014, 59 (1), 44–59. [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Bhatia, N.; Kumar, A.; A., G.; R., T.; S. K., S.; Vadakkadath Meethal, K.; T. M., S.; T. V., S. Bioinspired Gelatin Based Sticky Hydrogel for Diverse Surfaces in Burn Wound Care. Sci Rep 2022, 12 (1), 13735. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.; Pratap Singh, A.; Yadav, R. K. A Review on Polymer Hydrogel and Polymer Microneedle Based Transdermal Drug Delivery System. Mater Today Proc 2022, 61, 1061–1066. [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Biocompatible Nanoparticles and Vesicular Systems in Transdermal Drug Delivery for Various Skin Diseases. Int J Pharm 2019, 555, 49–62. [CrossRef]

- Kamei, M.; Matsuo, K.; Imanishi, H.; Hara, Y.; Quen, Y.-S.; Kamiyama, F.; Oiso, N.; Kawada, A.; Okada, N.; Nakayama, T. Transcutaneous Immunization with a Highly Active Form of XCL1 as a Vaccine Adjuvant Using a Hydrophilic Gel Patch Elicits Long-Term CD8+ T Cell Responses. J Pharmacol Sci 2020, 143 (3), 182–187. [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Ito, Y.; Imanishi, Y. Preparation of Porous Membranes Grafted with Poly(Spiropyran-containing Methacrylate) and Photocontrol of Permeability. J Appl Polym Sci 1994, 51 (12), 2027–2033. [CrossRef]

- Bardavid, Y.; Goykhman, I.; Nozaki, D.; Cuniberti, G.; Yitzchaik, S. Dipole Assisted Photogated Switch in Spiropyran Grafted Polyaniline Nanowires. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115 (7), 3123–3128. [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Sabey, C. J.; Fernando, G. F. Photoresponsive Polymers: An Investigation of Their Photoinduced Temperature Changes during Photoviscosity Measurements. Polymer (Guildf) 2007, 48 (1), 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Warshawsky, A.; Kahana, N.; Buchholtz, F.; Zelichonok, A.; Ratner, J.; Krongauz, V. Photochromic Polysulfones. 1. Synthesis of Polymeric Polysulfone Carrying Pendant Spiropyran and Spirooxazine Groups; 1995; Vol. 34. https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines.

- Allcock, H. R.; Kim, C. Photochromic Polyphosphazenes with Spiropyran Units. Macromolecules 1991, 24 (10), 2846–2851. [CrossRef]

- Raymo, F. M.; Tomasulo, M. Optical Processing with Photochromic Switches. Chemistry – A European Journal 2006, 12 (12), 3186–3193. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. M.; Harbron, E. J. Photomodulated PPV Emission in a Photochromic Polymer Film. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007, 111 (11), 4425–4430. [CrossRef]

- WANG, S.; YU, C.; CHOI, M.; KIM, S. A Switching Fluorescent Photochromic Carbazole–Spironaphthoxazine Copolymer. Dyes and Pigments 2008, 77 (1), 245–248. [CrossRef]

- Tomasulo, M.; Yildiz, I.; Raymo, F. M. Nanoparticle-Induced Transition from Positive to Negative Photochromism. Inorganica Chim Acta 2007, 360 (3), 938–944. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.-Q.; Zhu, L.; Han, J. J.; Wu, W.; Hurst, J. K.; Li, A. D. Q. Spiropyran-Based Photochromic Polymer Nanoparticles with Optically Switchable Luminescence. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128 (13), 4303–4309. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Azadi, A.; Rafiei, P. Hydrogel Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2008, 60 (15), 1638–1649. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, M. R.; Reis, A. V.; Takahashi, S. H.; Rubira, A. F.; Feitosa, J. P. A.; Muniz, E. C. Synthesis of a Novel Superabsorbent Hydrogel by Copolymerization of Acrylamide and Cashew Gum Modified with Glycidyl Methacrylate. Carbohydr Polym 2005, 61 (4), 464–471. [CrossRef]

- Patachia, S.; Valente, A. J. M.; Baciu, C. Effect of Non-Associated Electrolyte Solutions on the Behaviour of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)-Based Hydrogels. Eur Polym J 2007, 43 (2), 460–467. [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N. A.; Bures, P.; Leobandung, W.; Ichikawa, H. Hydrogels in Pharmaceutical Formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2000, 50 (1), 27–46. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.C.; He, Ch.C.;Huang, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.F.; Xiong, Ch. Preparation and Properties of Thermo-Sensitive Hydrogels of Konjac Glucomannan Grafted n-Isopropylacrylamide for Controlled Drug Delivery. Iranian Journal of Polymer Science and Technology 2007.

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Concheiro, A. Reversible Adsorption by a PH- and Temperature-Sensitive Acrylic Hydrogel. Journal of Controlled Release 2002, 80 (1–3), 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Elisseeff, L. L. and J. Injectable Hydrogels for Cartilage Tissue Engineering; 2003.

- Yang, M.; Tian, J.; Zhang, K.; Fei, X.; Yin, F.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Bioinspired Adhesive Antibacterial Hydrogel with Self-Healing and On-Demand Removability for Enhanced Full-Thickness Skin Wound Repair. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24 (11), 4843–4853. [CrossRef]

- Khutoryanskiy, V. V. Advances in Mucoadhesion and Mucoadhesive Polymers. Macromol Biosci 2011, 11 (6), 748–764. [CrossRef]

- Lahsoune, M.; Boutayeb, H.; Zerouali, K.; Belabbes, H.; El Mdaghri, N. Prévalence et État de Sensibilité Aux Antibiotiques d’Acinetobacter Baumannii Dans Un CHU Marocain. Med Mal Infect 2007, 37 (12), 828–831. [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R. B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M. E.; Giske, C. G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J. F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; Paterson, D. L.; Rice, L. B.; Stelling, J.; Struelens, M. J.; Vatopoulos, A.; Weber, J. T.; Monnet, D. L. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2012, 18 (3), 268–281. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T. R.; Yi, L.-X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; Yu, L.-F.; Gu, D.; Ren, H.; Chen, X.; Lv, L.; He, D.; Zhou, H.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.-H.; Shen, J. Emergence of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Mechanism MCR-1 in Animals and Human Beings in China: A Microbiological and Molecular Biological Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16 (2), 161–168. [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M. K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2016, 80 (3), 629–661. [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-C. Community-Acquired Klebsiella Pneumoniae Bacteremia: Global Differences in Clinical Patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 2002, 8 (2), 160–166. [CrossRef]

- Lakhundi, S.; Zhang, K. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018, 31 (4). [CrossRef]

- Diekema, D. J.; Pfaller, M. A.; Schmitz, F. J.; Smayevsky, J.; Bell, J.; Jones, R. N.; Beach, M. Survey of Infections Due to Staphylococcus Species: Frequency of Occurrence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Isolates Collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific Region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001, 32 (s2), S114–S132. [CrossRef]

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella Spp. as Nosocomial Pathogens: Epidemiology, Taxonomy, Typing Methods, and Pathogenicity Factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998, 11 (4), 589–603. [CrossRef]

- Nadasy, K. A.; Domiati-Saad, R.; Tribble, M. A. Invasive Klebsiella Pneumoniae Syndrome in North America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007, 45 (3), e25–e28. [CrossRef]

- Giulieri, S. G.; Tong, S. Y. C.; Williamson, D. A. Using Genomics to Understand Meticillin- and Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections. Microb Genom 2020, 6 (1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, F.; Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, D.; Dang, W.; Duan, J. Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant Gram-Positive Cocci in a Chinese Hospital over an 8-Year Period; 2015; Vol. 8. www.ijcem.com/.

- Morita, S.; Kitagawa, K.; Ozaki, Y. Hydrogen-Bond Structures in Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate): Infrared Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations with Model Compounds. Vib Spectrosc 2009, 51 (1), 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Ye, S.; Li, G.; Osawa, M. Effect of Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) on the Absorption of Bisphenol A in Poly(Acrylate)s Thin Films. Vib Spectrosc 2004, 35 (1–2), 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. W.; Sun, Y. M.; Huang, W. F. Curing Kinetics of the Synthesis of Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) (PHEMA) with Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) as a Crosslinking Agent. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 1997, 35 (10), 1873–1889. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. K.; Lesser, A. J. A Physical and Mechanical Study of Prestressed Competitive Double Network Thermoplastic Elastomers. Macromolecules 2011, 44 (6), 1480–1490. [CrossRef]

- Normand, V.; Lootens, D. L.; Amici, E.; Plucknett, K. P.; Aymard, P. New Insight into Agarose Gel Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2000, 1 (4), 730–738. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C. T.; Thorpe, S. D.; O’Brien, F. J.; Robinson, A. J.; Kelly, D. J. The Effect of Concentration, Thermal History and Cell Seeding Density on the Initial Mechanical Properties of Agarose Hydrogels. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2009, 2 (5), 512–521. [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. S.; Lim, T. K.; Voo, W. P.; Pogaku, R.; Tey, B. T.; Zhang, Z. Effect of Formulation of Alginate Beads on Their Mechanical Behavior and Stiffness. Particuology 2011, 9 (3), 228–234. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. S.; Hong, J. P.; Seo, Y. S.; Chung, S. M.; Nah, C. Fabrication and Characterization of Electrospun Polybutadiene Fibers Crosslinked by UV Irradiation. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 101 (4), 2333–2337. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhou, B.; Yang, K.; Xiong, X.; Luan, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Lei, P.; Luo, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, G.; Liang, L.; Wang, R.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Biofilm-Inspired Adhesive and Antibacterial Hydrogel with Tough Tissue Integration Performance for Sealing Hemostasis and Wound Healing. Bioact Mater 2020, 5 (4), 768–778. [CrossRef]

- Kłosiński, K. K.; Wach, R. A.; Girek-Bąk, M. K.; Rokita, B.; Kołat, D.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Kłosińska, B.; Duda, Ł.; Pasieka, Z. W. Biocompatibility and Mechanical Properties of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogels. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 15 (1), 144. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Z.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, K.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Ni, Y.; Wu, H. Mussel-Inspired Blue-Light-Activated Cellulose-Based Adhesive Hydrogel with Fast Gelation, Rapid Haemostasis and Antibacterial Property for Wound Healing. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 417, 129329. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gilbert, S.; Díaz-Chamorro, H.; Marambio, O. G.; Sánchez, J.; Martin-Trasancos, R.; Inostroza, M.; García-Herrera, C.; Pizarro, G. del C. Influence of Different Experimental Conditions on Bond Strength of Self-Adhesive Synthetic Polymer System Hydrogels for Biological Applications. React Funct Polym 2025, 213, 106264. [CrossRef]

- Engler, A. J.; Sen, S.; Sweeney, H. L.; Discher, D. E. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell 2006, 126 (4), 677–689. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shariati, K.; Ghovvati, M.; Vo, S.; Origer, N.; Imahori, T.; Kaneko, N.; Annabi, N. Hemostatic Patch with Ultra-Strengthened Mechanical Properties for Efficient Adhesion to Wet Surfaces. Biomaterials 2023, 301, 122240. [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Mooney, D. Polymeric Tissue Adhesives. Chem Rev 2021, 121 (18), 11336–11384. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G. R.; Ravanat, J.-L.; Cadet, J.; Miyamoto, S.; Medeiros, M. H. G.; Di Mascio, P. Energy Transfer between Singlet ( 1 Δ g ) and Triplet ( 3 Σ g - ) Molecular Oxygen in Aqueous Solution. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126 (10), 3056–3057. [CrossRef]

- Greer, A. Christopher Foote’s Discovery of the Role of Singlet Oxygen [ 1 O 2 ( 1 Δ g )] in Photosensitized Oxidation Reactions. Acc Chem Res 2006, 39 (11), 797–804. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. Photosensitized Generation of Singlet Oxygen. Photochem Photobiol 2007, 82 (5), 1161–1177. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Collins, J. G.; Keene, F. R. Ruthenium Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents. Chem Soc Rev 2015, 44 (8), 2529–2542. [CrossRef]

- Hormazábal, D. B.; Reyes, Á. B.; Cuevas, M. F.; Bravo, A. R.; Costa, D. M.; González, I. A.; Navas, D.; Brito, I.; Dreyse, P.; Cabrera, A. R.; Palavecino, C. E. Photodynamic Effectiveness of Copper-Iminopyridine Photosensitizers Coupled to Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Against Klebsiella Pneumoniae and the Bacterial Response to Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26 (9), 4178. [CrossRef]

| Feed monomer ratio | [AAm] (mol/g) |

[HEMA] (mol/g) |

[MBA] (mol.-%) |

[BSP] (mol.-%) |

Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 95 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 90 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 90 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 92 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 90 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 90 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.015/1.065 | 0.015/1.950 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 90 |

| AAm | HEMA | Ester | -NO2 | |

| Copolymer | (C=O) | (C=O) | (C=O) | -N-O |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 0.1 mol.% MBA | 1658 | 1713 (s) | (w) | --- |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm)-BSP with 0.1 mol.% MBA | 1659 | (w) | 1613 (s) | 1454 (s) |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 0.5 mol.% MBA | 1656 | 1713 (s) | (w) | --- |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm)-BSP with 0.5 mol.% MBA | 1657 | (w) | 1610 (s) | 1454 (s) |

| Feed monomer ratio | MBA (mol.-%) |

BSP (mol.-%) |

Shear stress (kPa) |

Shear modulus (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(HEMA-co-AAm) 1:1 | 0.1 0.5 |

0.0 0.0 |

0.67 ± 033 1.97 ± 0.25 |

1.69 ± 0.46 3.33 ± 1.27 |

| P(HEMA-co-AAm)-BSP 1:1 | 0.1 0.5 |

0.1 0.5 |

1.81±0.37 3.41±0.17 |

4.34 ±0.91 6.18 ±1.02 |

| Polymeric materials | Biomedical application | Young modulus (E)* | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyethyl methacrylate –co-acrylamide with Dopamine | Catechol-based bioinspired adhesive properties in a wet medium | 33.37±2.74-58.86±2.04 kPa |

[23] |

| Maleic anhydride-modified β-cyclodextrin (CD), amantadine as a competitive guest | Adhesive antibacterial hydrogel | 37.4-85.8 37.6 kPa |

[47] |

| Chitosan grafted with methacrylate, dopamine, and N-hydroxymethyl acrylamide | Biofilm-inspired adhesive antibacterial hydrogel | 34.0 kPa | [68] |

| Carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel | Biodegradable carbohydrate polymers |

2.3 kPa to 13.3 kPa, 12.5 kPa |

[69] |

| Allyl cellulose with Dopamine | Mussel-inspired cellulose-based adhesive hydrogel | 38.8 to 40.2 kPa | [70] |

| Hydroxyethyl methacrylate –co-acrylamide with cross-linker (MBA) | Biomimetic adhesive hidrogel | 1.39 ± 0.06 kPa, 3.85 ± 1.87 kPa | [71] |

| Hydroxyethyl methacrylate with acrylamide, N’N-methylene bis-acrylamide (MBA) and photochromic agent (BSP) | Photoactive hydrogels as materials for biological applications, such as antimicrobial patches |

4.34 ±0.91 6.18 ±1.02 kPa |

This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).