Submitted:

15 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

vivo ETs are rather not absorbed, while providing mainly ellagic acid (EA), which due to its trivial water-solubility, first pass effect, metabolism in the intestine to give UROs, or irreversible binding to cellular DNA and proteins is in turn very low bioavailable, thus failing as therapeutic in vivo. Up-to-day, only UROs have confirmed the beneficial effect demonstrated in vitro, by reaching tissues to the extent necessary for having therapeutic outcomes. Unfortunately, upon administration of food rich in ETs or ETs and EA, UROs formation is affected by extreme interindividual variability that renders them unreliable as novel clinically usable drugs. Large attention has been therefore paid specifically to multitarget EA, which is incessantly investigated as such or nanotechnologically manipulated to be a potential “lead compound” with protective action towards AD. A brief overview of the multi-factorial and multi-target aspects that characterize AD, and polyphenols activity respectively, as well as of the traditional and/or innovative clinical treatments available to treat AD constitutes the opening of this work. Upon focus on the pathophysiology of OS, and on EA chemical features and mechanisms leading to its antioxidant activity, an all-round updated analysis on the current EA-rich foods and EA involvement in the field of AD has been provided. The possible clinical usage of EA to treat AD has been shown reporting results by its applications in vivo and clinical trials. A critical view about the need for a more extensive use of the most rapid diagnostic methods to detect AD from its early symptoms has also been included in this work.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

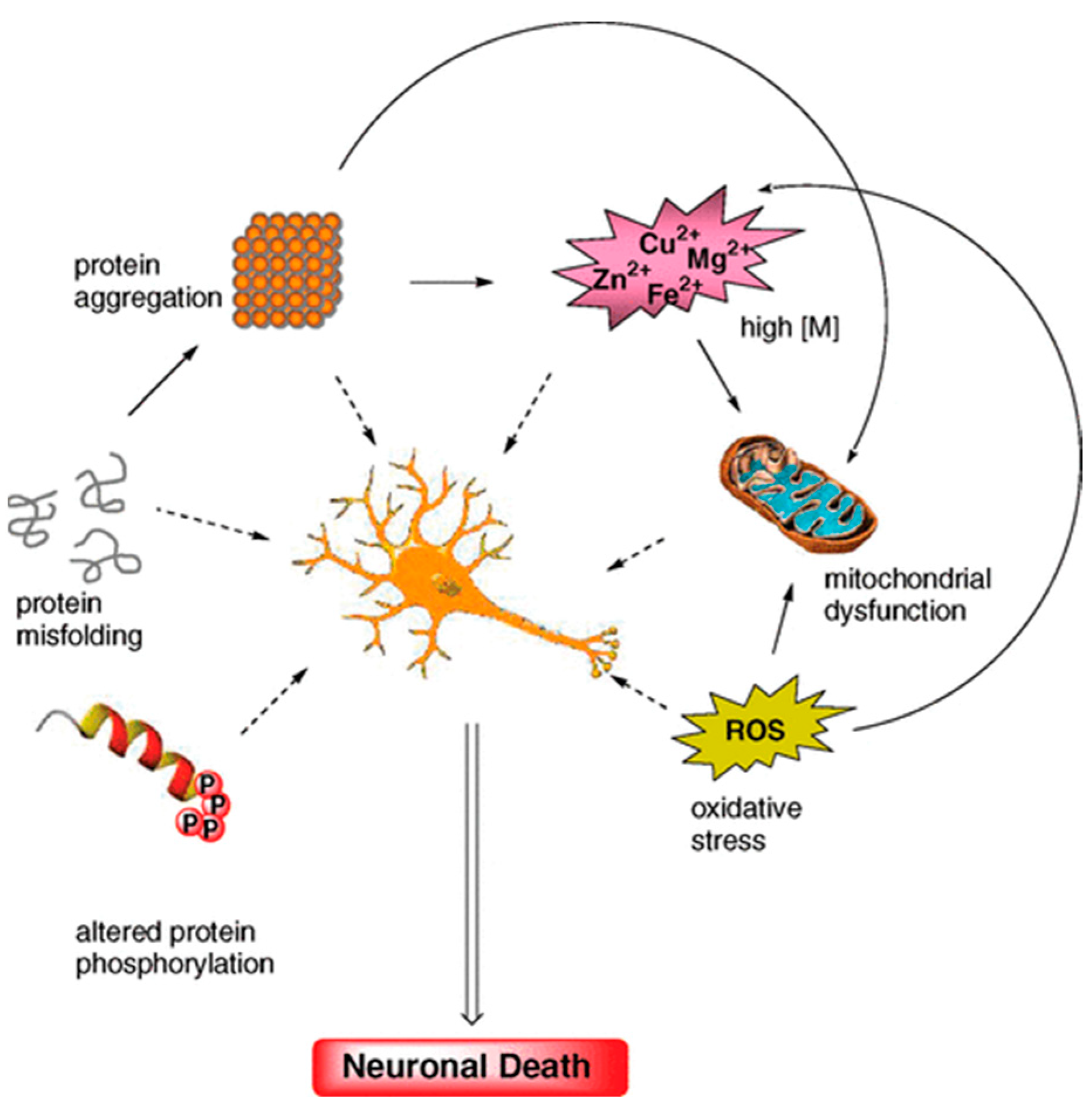

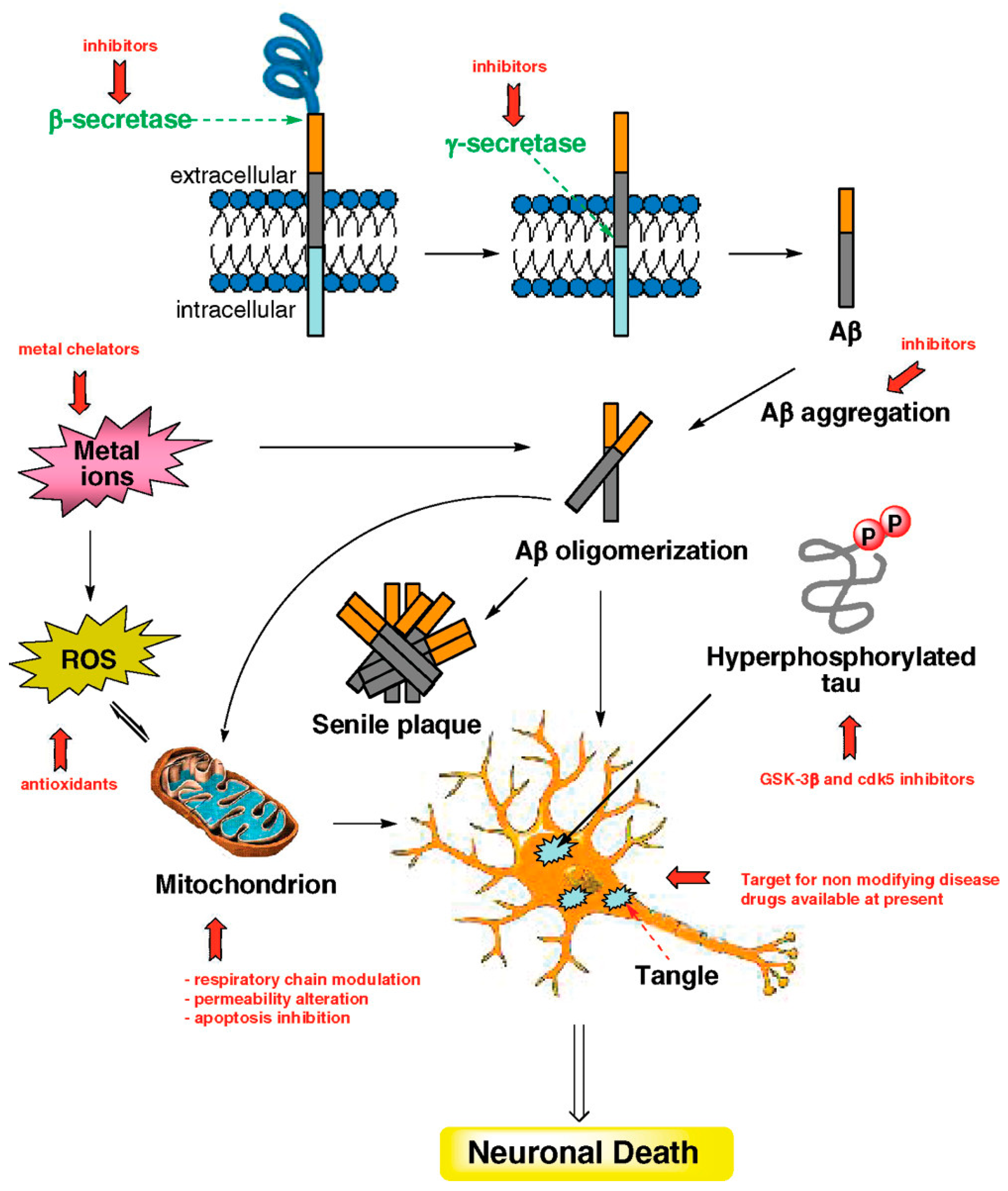

2. Multifactorial Nature of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Alzheimer Disease (AD)

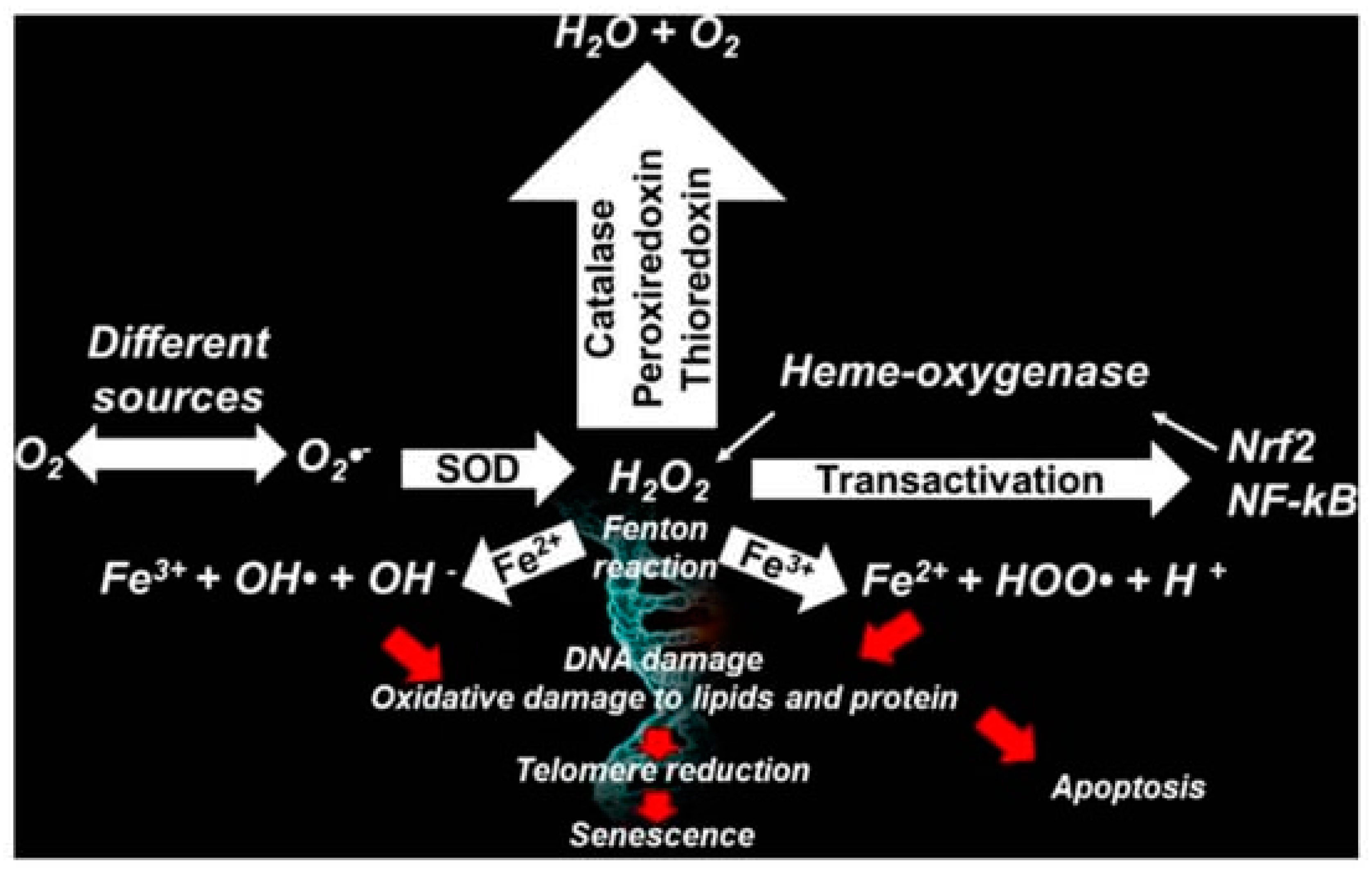

2.1. More in Deep in The Multifactorial Causes of AD: Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS)

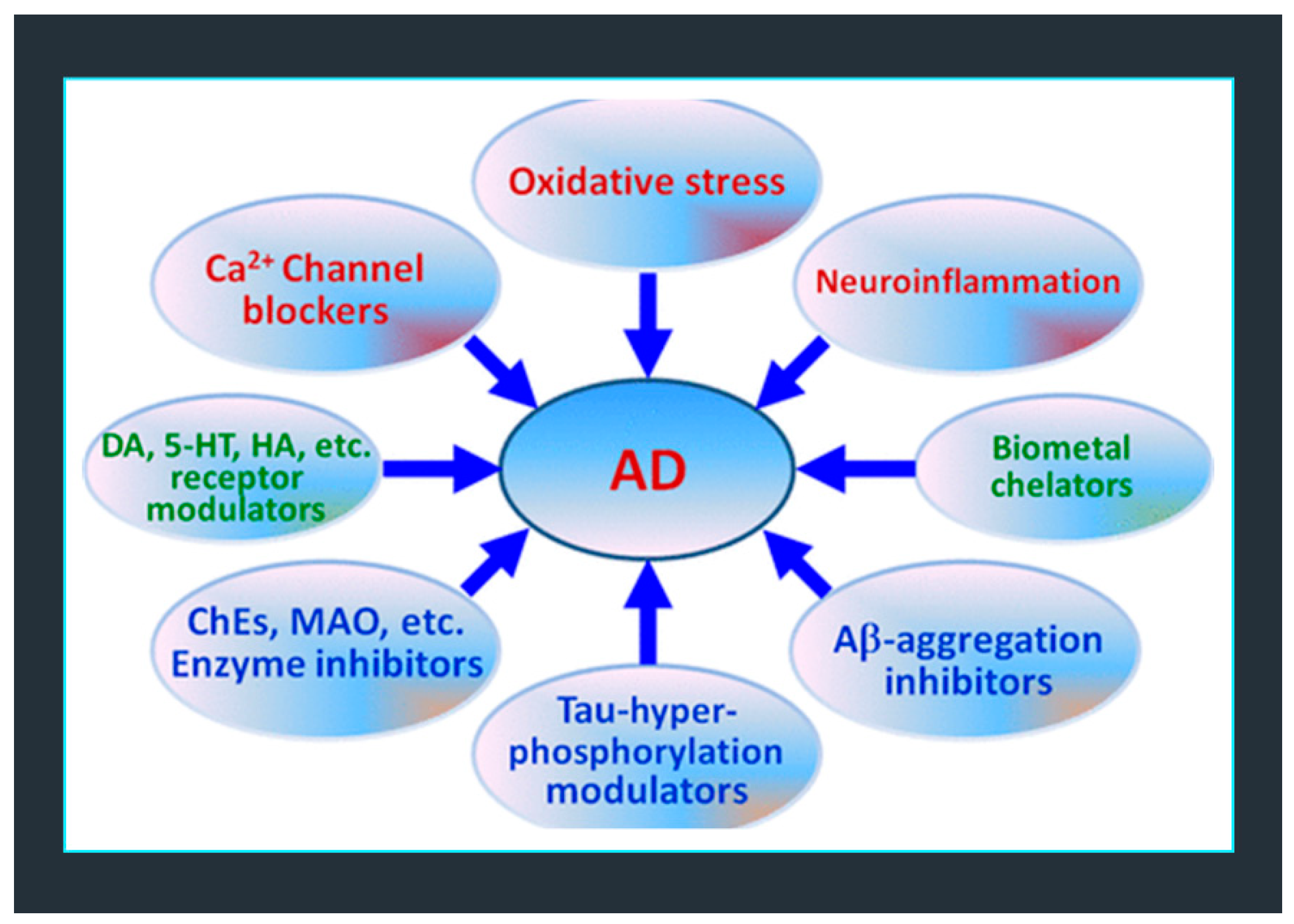

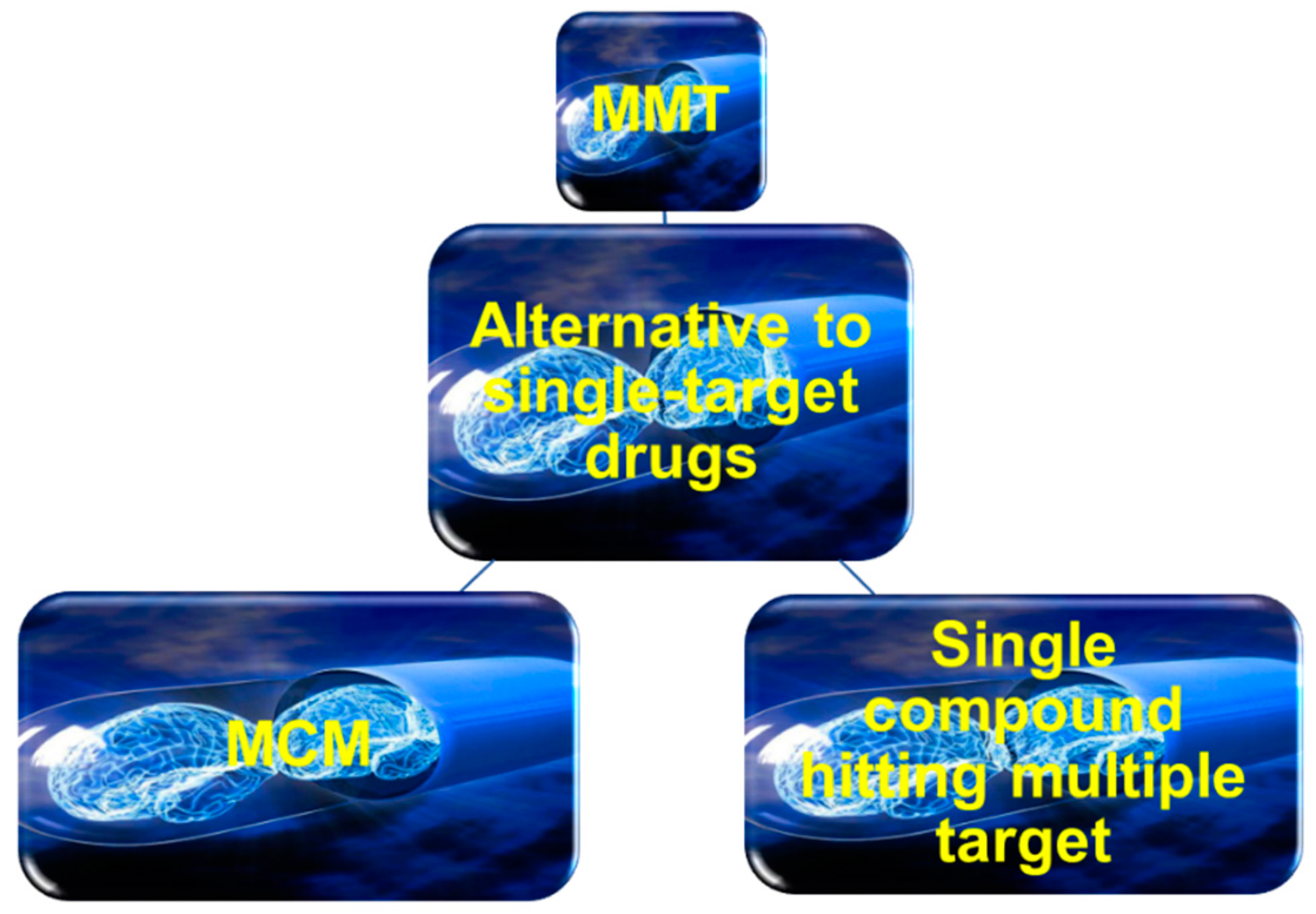

3. One-Target Drugs vs. Multi-Target Therapies in the Treatment of Degenerative Diseases

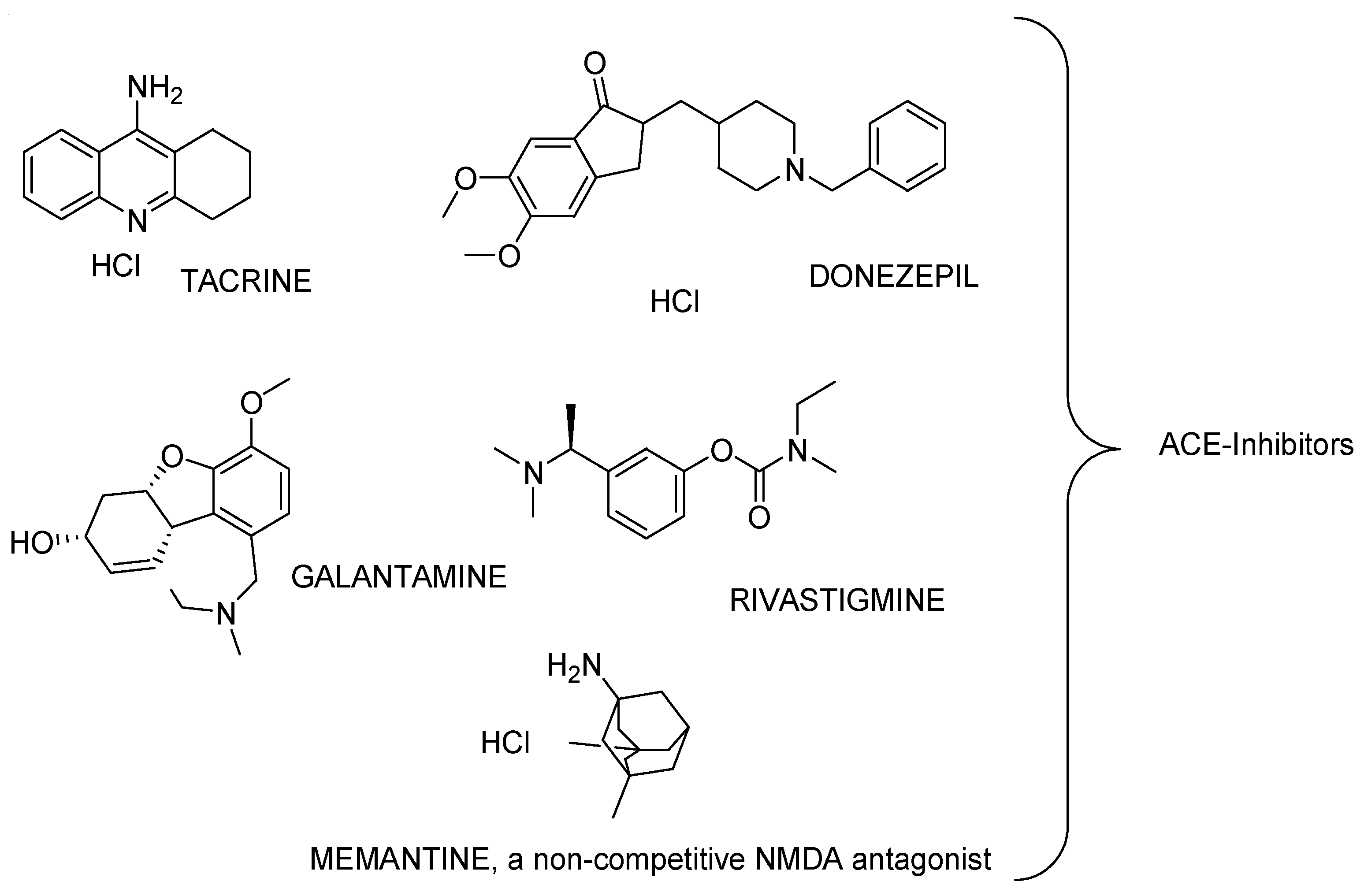

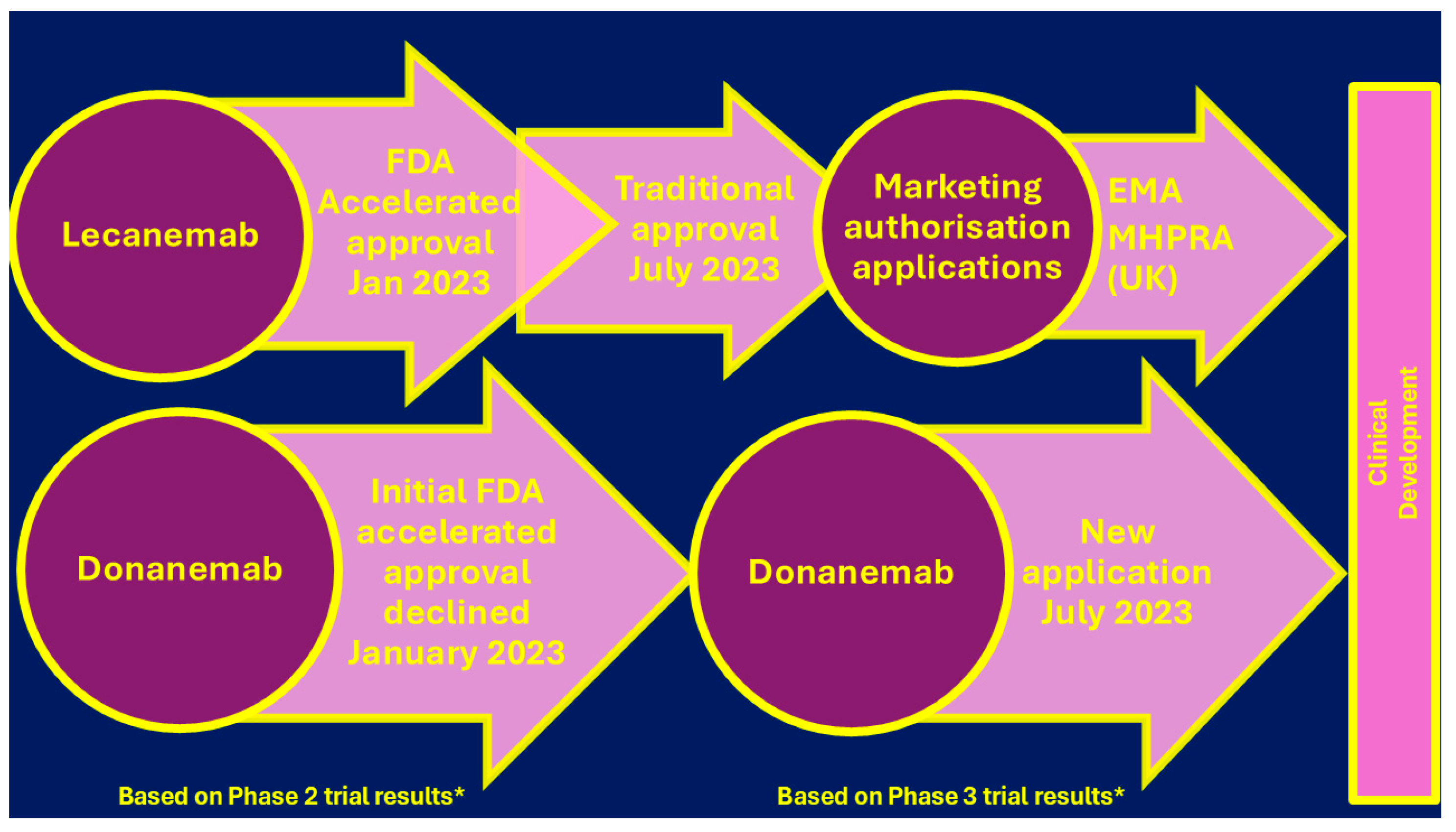

3.1. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Currently Available Medicines and/or Treatments in Development

Current AD Therapies

Versus Disease-Modifying Therapies in Alzheimer's Disease [123]

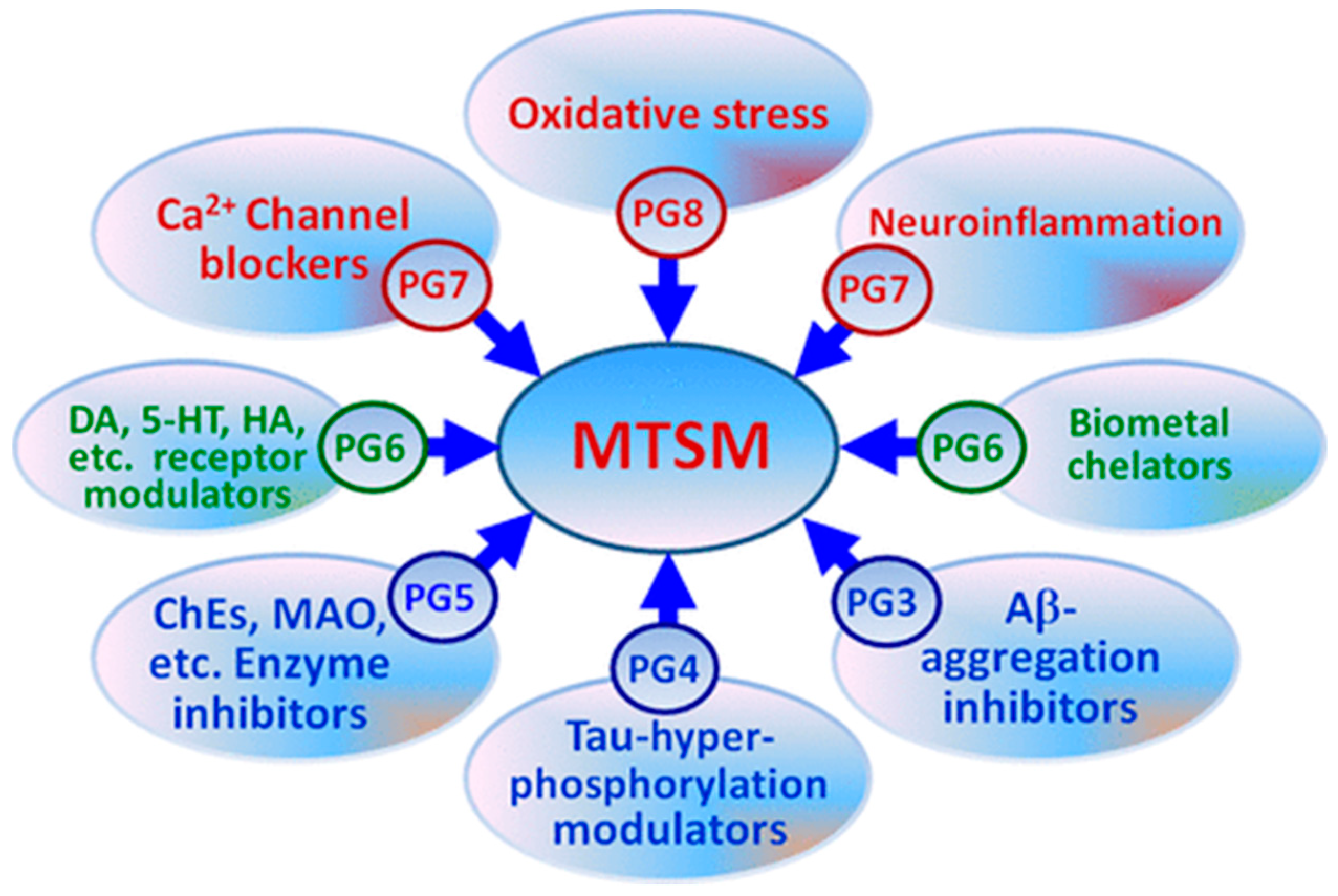

Multi-Target Therapy (MTT) for AD

4. Ellagitannins (ETs) and EA as Multi-Target Compounds: Strengths and Weaknesses

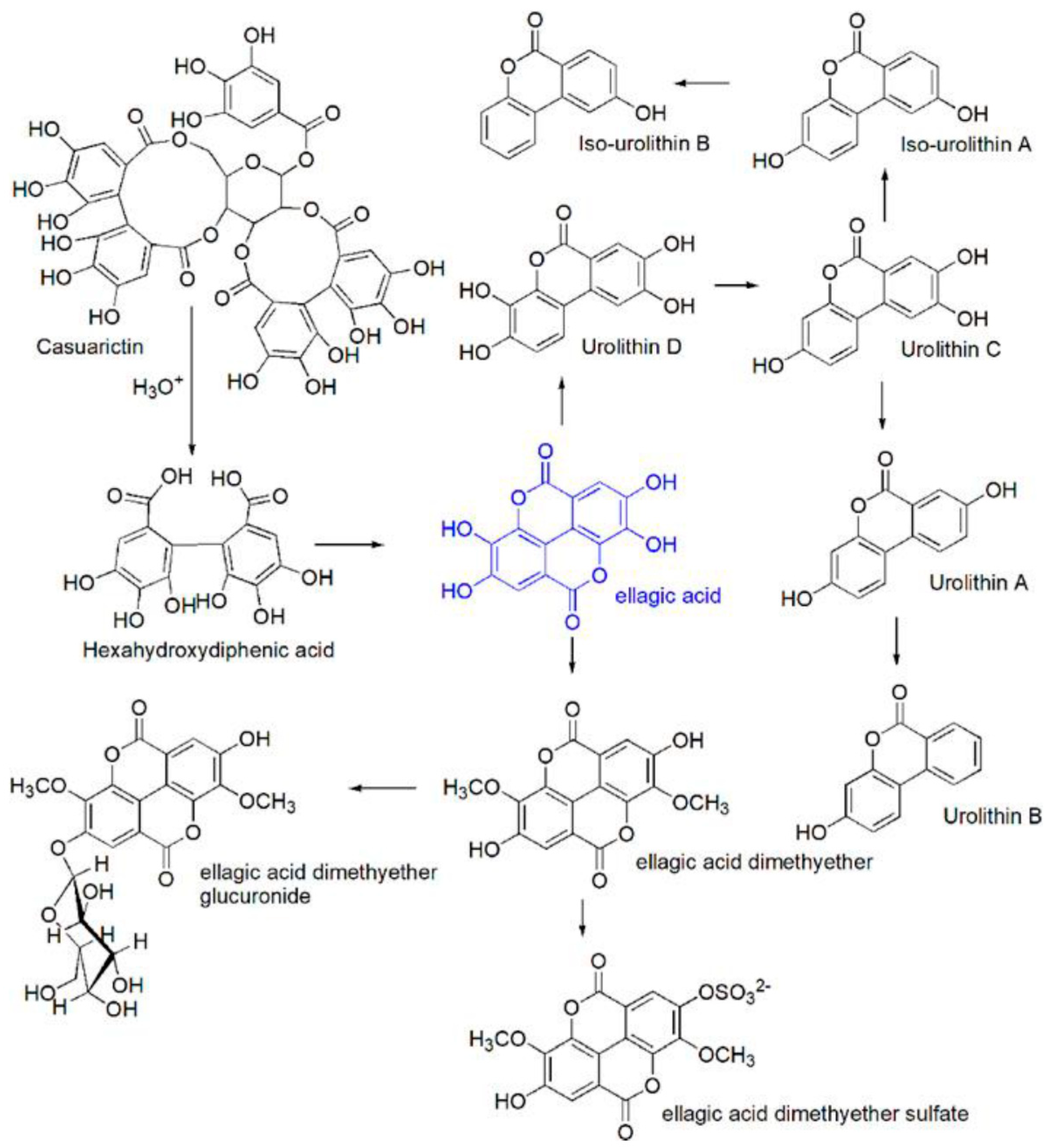

4.1. Bioavailability Drawbacks Associated with ETs and EA

4.2. Ellagic Acid or Urolithins?

4.4. Drawbacks Associated to UROs Hamper Their Clinical Development Thus Quenching the Researcher Interest

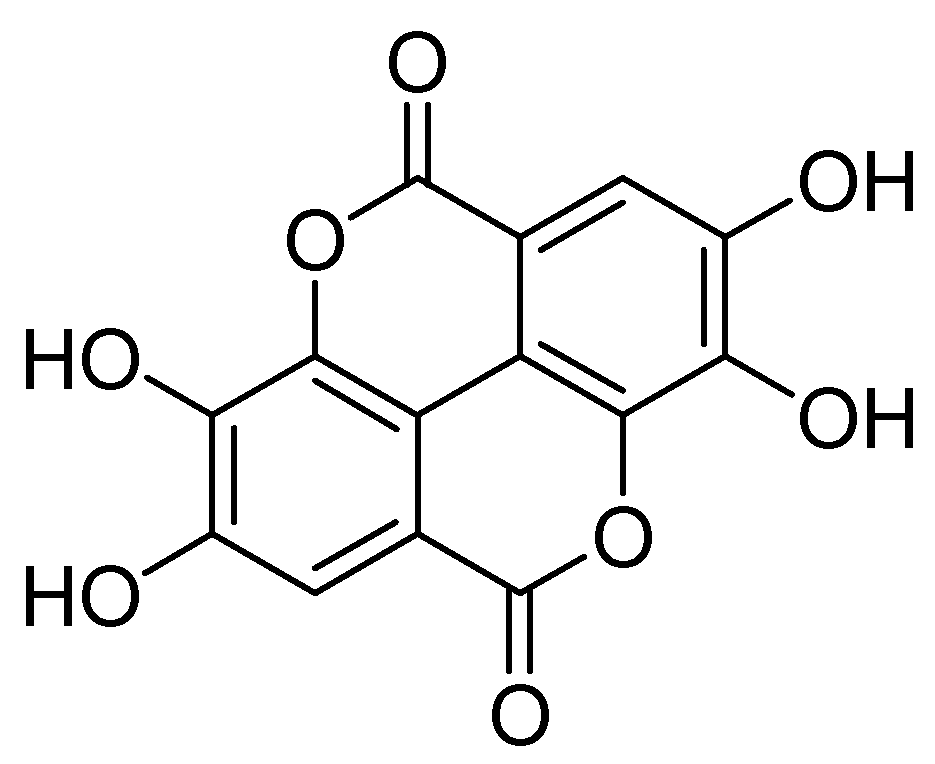

5. EA as Template Antioxidant Molecule for the Development of New Therapeutics for AD

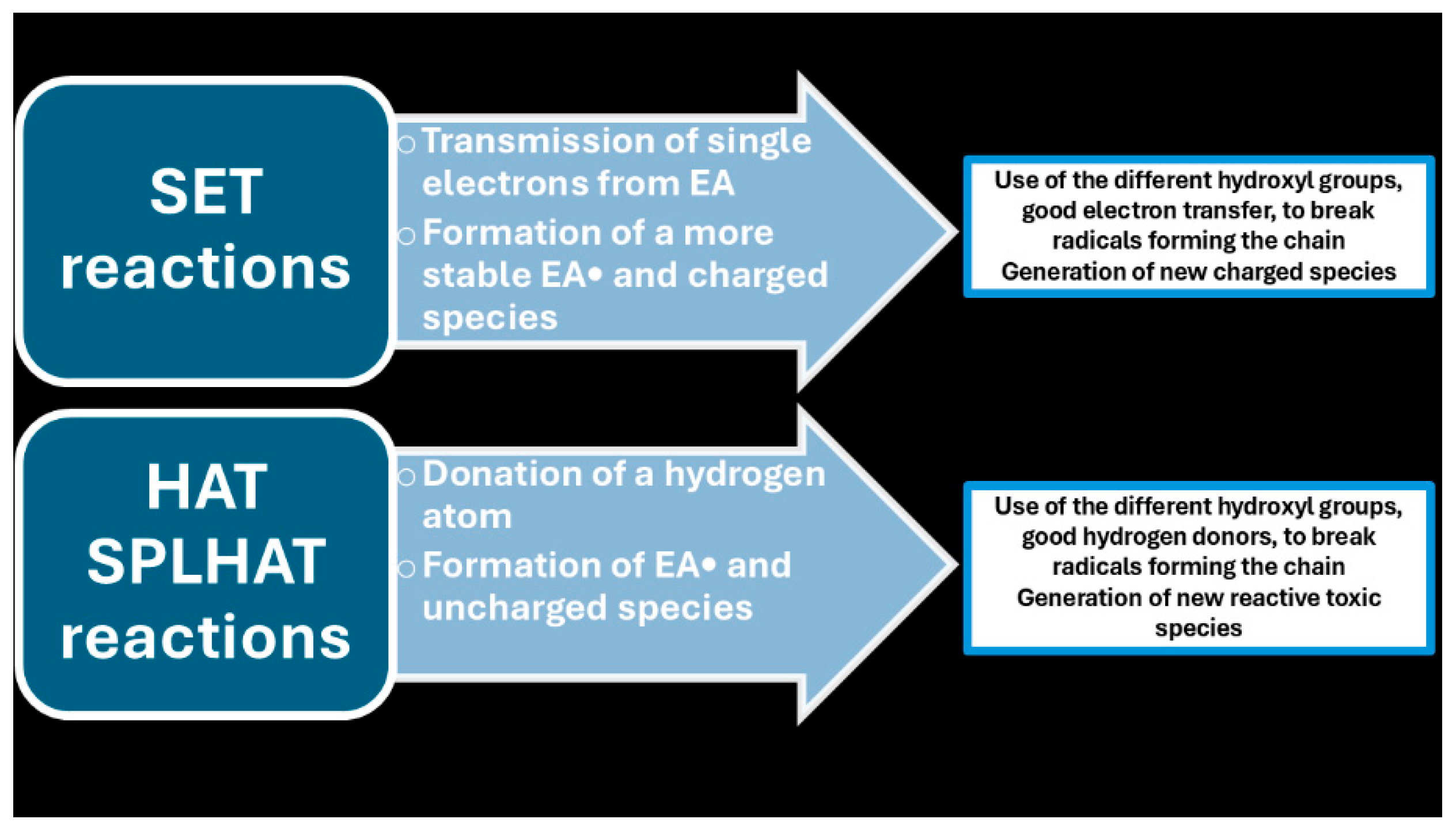

5.1. EA Antioxidant Effects: Proposed Mechanisms of Action

Type I scavenging reactions

Type II scavenging reactions

6. EA-rich foods, EA Food Supplements, and EA Involvement in the Treatment of AD

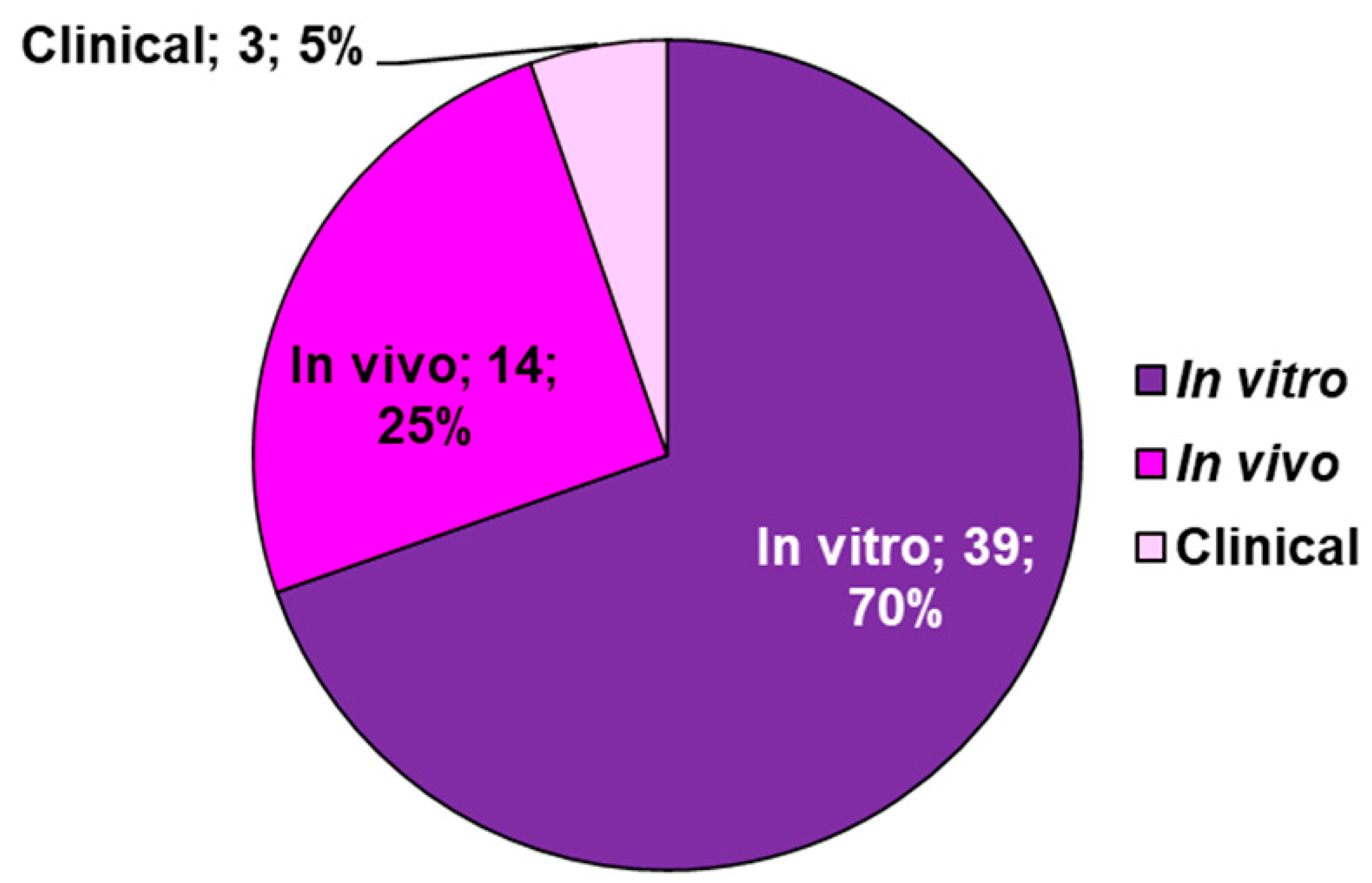

6.1. Most Relevant In Vitro and In Vivo Studies Using ETs and EA-rich Plants

8. Conclusions, Perspective for the Future and Authors Opinions

8.1. Imaging Analyses Available to Confirm the Presence of AD

8.2. An Opportunity to Change

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| AChE | acetyl cholinesterase |

| ACR | acrylamide |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| AGE | advanced glycation end-product |

| ASD | amorphous solid dispersion |

| ATRA | all-trans retinoic acid |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BP | blood pressure |

| BuChE | butyrylcholinesterase |

| Cmax | maximum concentration in plasma |

| CA | cornus ammonis |

| CAAdP | cellulose acetate adipate propionate |

| Ca2+-EA-ALG NP | ellagic acid encapsulated in calcium-alginate nanoparticles |

| CAT | catalase |

| Ch/β-GP | chitosan/β-glycerophosphate |

| CMCAB | carboxymethyl cellulose acetate butyrate |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| Cup | cuprizone |

| cyt C | cytochrome c |

| DG | dentate gyrus |

| d-gal | d-galactose |

| DOX | doxorubicin |

| EA | ellagic acid |

| EA-NP | ellagic acid nanoparticle |

| EEG | electroencephalographic |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| EPM | elevated plus-maze |

| Erβ | estrogen receptor β |

| ET | ellagitannin |

| FST | forced swimming test |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid type |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| HPMCAS | hydroxy-propyl-methyl cellulose acetate succinate |

| HPC | hippocampus/hippocampal |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| iNOS | nitric oxide synthase |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LPO | lipid peroxidation |

| LTP | long-term potentiation |

| MAO | monoamine oxidase |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MFB | medial forebrain bundle |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| OLG | oligodendrocyte |

| PCL | poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| PCO | protein carbonylation |

| PCPA | p-chlorophenylalanine |

| PD | Parkinson disease |

| PDI | protein disulfide isomerase |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PON-1 | paraoxonase |

| PTZ | pentylenetetrazol |

| PVP | polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| RAGE | receptor of advanced glycation end-products |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SA | sodium arsenite |

| SAD | sporadic Alzheimer disease |

| SNc | substantia nigra pars compacta |

| SNO | S-nitrosylation |

| SNO-PDI | S-nitrosylation of protein disulfide isomerase |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SSB | single-strand break |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| TAC | total antioxidant capacity |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| TCDD | 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin |

| ThT | thioflavin T |

| TOS | total oxidant status |

| TST | tail suspension test |

| β-gal | β-galactosidase |

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptamine |

| 6-OHDA | 6-hydroxydopamine |

References

- Brookmeyer, R.; Gray, S.; Kawas, C. Projections of Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States and the Public Health Impact of Delaying Disease Onset. Am J Public Health 1998, 88, 1337–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, V.C.T.; Cai, Y.; Markus, H.S. Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Mechanisms, Treatment, and Future Directions. International Journal of Stroke 2024, 19, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabert, M.H.; Liu, X.; Doty, R.L.; Serby, M.; Zamora, D.; Pelton, G.H.; Marder, K.; Albers, M.W.; Stern, Y.; Devanand, D.P. A 10-item Smell Identification Scale Related to Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann Neurol 2005, 58, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldemar, G.; Dubois, B.; Emre, M.; Georges, J.; McKeith, I.G.; Rossor, M.; Scheltens, P.; Tariska, P.; Winblad, B. Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Disorders Associated with Dementia: EFNS Guideline. Eur J Neurol 2007, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, N.; Shah, M.A.; Rasul, A.; Chauhdary, Z.; Saleem, U.; Khan, H.; Ahmed, N.; Uddin, Md.S.; Mathew, B.; Behl, T.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Ellagic Acid in Alzheimer’s Disease: Focus on Underlying Molecular Mechanisms of Therapeutic Potential. Curr Pharm Des 2021, 27, 3591–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiraboschi, P.; Hansen, L.A.; Thal, L.J.; Corey-Bloom, J. The Importance of Neuritic Plaques and Tangles to the Development and Evolution of AD. Neurology 2004, 62, 1984–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, A.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; Tumiatti, V.; Recanatini, M.; Melchiorre, C. Multi-Target-Directed Ligands To Combat Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Med Chem 2008, 51, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oset-Gasque, M.J.; Marco-Contelles, J. Alzheimer’s Disease, the “One-Molecule, One-Target” Paradigm, and the Multitarget Directed Ligand Approach. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lee, G.; Zhong, K.; Fonseca, J.; Cheng, F. Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Development Pipeline: 2023. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.W.; Sano, M. Economic Considerations in the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin Interv Aging 2006, 1, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamptey, R.N.L.; Chaulagain, B.; Trivedi, R.; Gothwal, A.; Layek, B.; Singh, J. A Review of the Common Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Therapeutic Approaches and the Potential Role of Nanotherapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, V.M.; Masand, N.; Gautam, V.; Kaushik, S.; Wu, D. Multi-Target-Directed Ligand Approach in Anti-Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery. In Deciphering Drug Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 285–319. [Google Scholar]

- Alfei, S.; Turrini, F.; Catena, S.; Zunin, P.; Grilli, M.; Pittaluga, A.M.; Boggia, R. Ellagic Acid a Multi-Target Bioactive Compound for Drug Discovery in CNS? A Narrative Review. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 183, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Holcroft, D.M.; Kader, A.A. Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate Juice and Its Relationship with Phenolic Composition and Processing. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Holcroft, D.M.; Kader, A.A. Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate Juice and Its Relationship with Phenolic Composition and Processing. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Zuccari, G. Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Capabilities, and Bioavailability: Ellagic Acid or Urolithins? Antioxidants 2020, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, G.; Rossoni, G.; Santagati, N.; Facino, R. Anti-Ischemic Activity and Endothelium-Dependent Vasorelaxant Effect of Hydrolysable Tannins from the Leaves of Rhus Coriaria (Sumac) in Isolated Rabbit Heart and Thoracic Aorta. Planta Med 2009, 75, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrosa, M.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagitannins, Ellagic Acid and Vascular Health. Mol Aspects Med 2010, 31, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrosa, M.; González-Sarrías, A.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Selma, M. V.; Azorín-Ortuño, M.; Toti, S.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Dolara, P.; Espín, J.C. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of a Pomegranate Extract and Its Metabolite Urolithin-A in a Colitis Rat Model and the Effect of Colon Inflammation on Phenolic Metabolism☆. J Nutr Biochem 2010, 21, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mente, A.; de Koning, L.; Shannon, H.S.; Anand, S.S. A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Causal Link Between Dietary Factors and Coronary Heart Disease. Arch Intern Med 2009, 169, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y.; Ohie, T.; Yonekawa, Y.; Yonemoto, K.; Aizawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Taguchi, C.; et al. Coffee and Green Tea As a Large Source of Antioxidant Polyphenols in the Japanese Population. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, I.; Yeşiloğlu, Y.; Bayrak, Y. Spectroscopic Studies on the Antioxidant Activity of Ellagic Acid. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2014, 130, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, R.J.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Perry, G. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. In Handbook of Neurotoxicity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.N.; Khan, R.H. Protein Misfolding and Related Human Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of Toxicity, Proteins Involved, and Current Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 223, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majid, N.; Khan, R.H. Protein Aggregation: Consequences, Mechanism, Characterization and Inhibitory Strategies. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 242, 125123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Sahoo, B.R.; Zheng, J.; Faller, P.; Straub, J.E.; Dominguez, L.; Shea, J.-E.; Dokholyan, N. V.; De Simone, A.; et al. Amyloid Oligomers: A Joint Experimental/Computational Perspective on Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, Type II Diabetes, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Chem Rev 2021, 121, 2545–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrank, S.; Barrington, N.; Stutzmann, G.E. Calcium-Handling Defects and Neurodegenerative Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2020, 12, a035212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. ..Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Mediated Antibacterial Oxidative Therapies: Available Methods to Generate ROS and a Novel Option Proposal. IJMS 2024, 2024051628.

- Prati, F.; Bottegoni, G.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Cavalli, A. BACE-1 Inhibitors: From Recent Single-Target Molecules to Multitarget Compounds for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Med Chem 2018, 61, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhoba, X.H.; Viegas Jr., C.; Mosa, R.A.; Viegas, F.P.; Pooe, O.J. <p>Potential Impact of the Multi-Target Drug Approach in the Treatment of Some Complex Diseases</P>. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020, Volume 14, 3235–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morató, X.; Pytel, V.; Jofresa, S.; Ruiz, A.; Boada, M. Symptomatic and Disease-Modifying Therapy Pipeline for Alzheimer’s Disease: Towards a Personalized Polypharmacology Patient-Centered Approach. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W.; Klein, P. New Approaches for Developing Multi-Targeted Drug Combinations for Disease Modification of Complex Brain Disorders. Does Epilepsy Prevention Become a Realistic Goal? Pharmacol Ther 2022, 229, 107934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatematteo, F.S.; Niso, M.; Contino, M.; Leopoldo, M.; Abate, C. Multi-Target Directed Ligands (MTDLs) Binding the Σ1 Receptor as Promising Therapeutics: State of the Art and Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Giannoni, P.; Signorello, M.G.; Torazza, C.; Zuccari, G.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. The Remarkable and Selective In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Synthesized Bola-Amphiphilic Nanovesicles on Etoposide-Sensitive and -Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphy, R.; Rankovic, Z. Designed Multiple Ligands. An Emerging Drug Discovery Paradigm. J Med Chem 2005, 48, 6523–6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morphy, R.; Rankovic, Z. Fragments, Network Biology and Designing Multiple Ligands. Drug Discov Today 2007, 12, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphy, R.; Kay, C.; Rankovic, Z. From Magic Bullets to Designed Multiple Ligands. Drug Discov Today 2004, 9, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolami, M.; Rocco, D.; Messore, A.; Di Santo, R.; Costi, R.; Madia, V.N.; Scipione, L.; Pandolfi, F. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease – a Patent Review (2016–Present). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2021, 31, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimberti, D.; Scarpini, E. Old and New Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2016, 25, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padala, K.P.; Padala, P.R.; McNeilly, D.P.; Geske, J.A.; Sullivan, D.H.; Potter, J.F. The Effect of HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors on Cognition in Patients With Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Prospective Withdrawal and Rechallenge Pilot Study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012, 10, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, M.F.; Kost, J.; Tariot, P.N.; Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Vellas, B.; Sur, C.; Mukai, Y.; Voss, T.; Furtek, C.; et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.F.; Kost, J.; Voss, T.; Mukai, Y.; Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Tariot, P.N.; Vellas, B.; van Dyck, C.H.; Boada, M.; et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1408–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henley, D.; Raghavan, N.; Sperling, R.; Aisen, P.; Raman, R.; Romano, G. Preliminary Results of a Trial of Atabecestat in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1483–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, A.M.; Tariot, P.N.; Zimmer, J.A.; Selzler, K.J.; Bragg, S.M.; Andersen, S.W.; Landry, J.; Krull, J.H.; Downing, A.M.; Willis, B.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lanabecestat for Treatment of Early and Mild Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, A.C.; Evans, C.D.; Mancini, M.; Wang, H.; Shcherbinin, S.; Lu, M.; Natanegara, F.; Willis, B.A. Phase II (NAVIGATE-AD Study) Results of LY3202626 Effects on Patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2021, 5, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.Gov. A Study of CNP520 Versus Placebo in Participants at Risk for the Onset of Clinical Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Iraji, A.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Firuzi, O.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Edraki, N. Novel Small Molecule Therapeutic Agents for Alzheimer Disease: Focusing on BACE1 and Multi-Target Directed Ligands. Bioorg Chem 2020, 97, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbimbo, B.P.; Watling, M. Investigational BACE Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2019, 28, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doody, R.S.; Raman, R.; Farlow, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Vellas, B.; Joffe, S.; Kieburtz, K.; He, F.; Sun, X.; Thomas, R.G.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Semagacestat for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coric, V.; Salloway, S.; van Dyck, C.H.; Dubois, B.; Andreasen, N.; Brody, M.; Curtis, C.; Soininen, H.; Thein, S.; Shiovitz, T.; et al. Targeting Prodromal Alzheimer Disease With Avagacestat. JAMA Neurol 2015, 72, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.C. Effect of Tarenflurbil on Cognitive Decline and Activities of Daily Living in Patients With Mild Alzheimer Disease<Subtitle>A Randomized Controlled Trial</Subtitle>. JAMA 2009, 302, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, C.W.; Bush, A.I.; Mackinnon, A.; Macfarlane, S.; Mastwyk, M.; MacGregor, L.; Kiers, L.; Cherny, R.; Li, Q.-X.; Tammer, A.; et al. Metal-Protein Attenuation With Iodochlorhydroxyquin (Clioquinol) Targeting Aβ Amyloid Deposition and Toxicity in Alzheimer Disease. Arch Neurol 2003, 60, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannfelt, L.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Batsman, S.; Ames, D.; Harrison, J.; Masters, C.L.; Targum, S.; Bush, A.I.; Murdoch, R.; et al. Safety, Efficacy, and Biomarker Findings of PBT2 in Targeting Aβ as a Modifying Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Phase IIa, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Neurol 2008, 7, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L.; Rowe, C.C.; Barnham, K.J.; Cherny, R.; Woodward, M.; Bozinosvski, S.; Salvado, O.; Bourgeat, P.; Perez, K.; Fowler, C.; et al. A Randomized, Exploratory Molecular Imaging Study Targeting Amyloid β with a Novel 8-OH Quinoline in Alzheimer’s Disease: The PBT2-204 IMAGINE Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2017, 3, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantile, F.; Prisco, A. Vaccination against β-Amyloid as a Strategy for the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biology (Basel) 2020, 9, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolar, M.; Abushakra, S.; Hey, J.A.; Porsteinsson, A.; Sabbagh, M. Aducanumab, Gantenerumab, BAN2401, and ALZ-801—the First Wave of Amyloid-Targeting Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease with Potential for near Term Approval. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowitzki, S.; Lasser, R.A.; Dorflinger, E.; Scheltens, P.; Barkhof, F.; Nikolcheva, T.; Ashford, E.; Retout, S.; Hofmann, C.; Delmar, P.; et al. A Phase III Randomized Trial of Gantenerumab in Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2017, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.; Liu, K.Y. Questions EMERGE as Biogen Claims Aducanumab Turnaround. Nat Rev Neurol 2020, 16, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.C.; Emerson, S.; Kesselheim, A.S. Evaluation of Aducanumab for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 2021, 325, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpas, C.B.; Vivash, L.; Genc, S.; Saling, M.M.; Desmond, P.; Steward, C.; Hicks, R.J.; Callahan, J.; Brodtmann, A.; Collins, S.; et al. A Phase IIa Randomized Control Trial of VEL015 (Sodium Selenate) in Mild-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2016, 54, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, B.R.; Roberts, B.R.; Malpas, C.B.; Vivash, L.; Genc, S.; Saling, M.M.; Desmond, P.; Steward, C.; Hicks, R.J.; Callahan, J.; et al. Supranutritional Sodium Selenate Supplementation Delivers Selenium to the Central Nervous System: Results from a Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.S.; Mitev, V.; Vlaykova, T.; Cavicchi, L.; Zhelev, N. Discovery and Development of Seliciclib. How Systems Biology Approaches Can Lead to Better Drug Performance. J Biotechnol 2015, 202, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, G.M.; Catania, M.V.; Puzzo, D.; Spatuzza, M.; Pellitteri, R.; Gulisano, W.; Torrisi, S.A.; Giurdanella, G.; Piazza, C.; Impellizzeri, A.R.; et al. The Antineoplastic Drug Flavopiridol Reverses Memory Impairment Induced by Amyloid-ß 1-42 Oligomers in Mice. Pharmacol Res 2016, 106, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovestone, S.; Boada, M.; Dubois, B.; Hüll, M.; Rinne, J.O.; Huppertz, H.-J.; Calero, M.; Andrés, M. V.; Gómez-Carrillo, B.; León, T.; et al. A Phase II Trial of Tideglusib in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 45, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade Nunes, M.; Araujo Viel, T.; Sousa Buck, H. Microdose Lithium Treatment Stabilized Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2013, 10, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, S.; Kishi, T.; Annas, P.; Basun, H.; Hampel, H.; Iwata, N. Lithium as a Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 48, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, S.; Kishi, T.; Annas, P.; Basun, H.; Hampel, H.; Iwata, N. Lithium as a Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 48, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischik, C.M.; Staff, R.T.; Wischik, D.J.; Bentham, P.; Murray, A.D.; Storey, J.M.D.; Kook, K.A.; Harrington, C.R. Tau Aggregation Inhibitor Therapy: An Exploratory Phase 2 Study in Mild or Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 44, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, S.; Feldman, H.H.; Schneider, L.S.; Wilcock, G.K.; Frisoni, G.B.; Hardlund, J.H.; Moebius, H.J.; Bentham, P.; Kook, K.A.; Wischik, D.J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tau-Aggregation Inhibitor Therapy in Patients with Mild or Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomised, Controlled, Double-Blind, Parallel-Arm, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet 2016, 388, 2873–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.H.; Pipingas, A.; Scholey, A.B. Investigation of the Effects of Solid Lipid Curcumin on Cognition and Mood in a Healthy Older Population. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2015, 29, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and the Effect of BMS-241027 on Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Subjects with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Morimoto, B.H.; Schmechel, D.; Hirman, J.; Blackwell, A.; Keith, J.; Gold, M. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Ascending-Dose, Randomized Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Effects on Cognition of AL-108 after 12 Weeks of Intranasal Administration in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2013, 35, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozes, I.; Stewart, A.; Morimoto, B.; Fox, A.; Sutherland, K.; Schmechel, D. Addressing Alzheimers Disease Tangles: From NAP to AL-108. Curr Alzheimer Res 2009, 6, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, R.M.; Miller, Z.; Koestler, M.; Rojas, J.C.; Ljubenkov, P.A.; Rosen, H.J.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Fagan, A.M.; Cobigo, Y.; Brown, J.A.; et al. Reactions to Multiple Ascending Doses of the Microtubule Stabilizer TPI-287 in Patients With Alzheimer Disease, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, and Corticobasal Syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. 24 Months Safety and Efficacy Study of AADvac1 in Patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Congdon, E.E.; Sigurdsson, E.M. Tau-Targeting Therapies for Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-C.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Wang, G.-Q.; Liu, H.-Y.; Cao, Y.-P. Early Active Immunization with Aβ 3–10 -KLH Vaccine Reduces Tau Phosphorylation in the Hippocampus and Protects Cognition of Mice. Neural Regen Res 2020, 15, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Phase 2 Study of BIIB092 in Participants with Early Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of ABBV-8E12 in Subjects with Early Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. An Extension Study of ABBV-8E12 in Early Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

- ClinicalTrials.Gov. A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Semorinemab in Patients with Prodromal to Mild Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of Semorinemab in Patients with Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Single-Ascending-Dose Study of BIIB076 in Healthy Volunteers and Participants with Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of LY3303560 in Participants with Early Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of JNJ-63733657 in Participants with Early Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study to Test the Safety and Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Single Doses of UCB0107 in Healthy Japanese Subjects.

- Courade, J.-P.; Angers, R.; Mairet-Coello, G.; Pacico, N.; Tyson, K.; Lightwood, D.; Munro, R.; McMillan, D.; Griffin, R.; Baker, T.; et al. Epitope Determines Efficacy of Therapeutic Anti-Tau Antibodies in a Functional Assay with Human Alzheimer Tau. Acta Neuropathol 2018, 136, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Lin, C. TLR4 Targeting as a Promising Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer Disease Treatment. Front Neurosci 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Alonso, A.; Schetters, S.T.T.; Sri, S.; Askew, K.; Mancuso, R.; Vargas-Caballero, M.; Holscher, C.; Perry, V.H.; Gomez-Nicola, D. Pharmacological Targeting of CSF1R Inhibits Microglial Proliferation and Prevents the Progression of Alzheimer’s-like Pathology. Brain 2016, 139, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, R.; Fryatt, G.; Cleal, M.; Obst, J.; Pipi, E.; Monzón-Sandoval, J.; Ribe, E.; Winchester, L.; Webber, C.; Nevado, A.; et al. CSF1R Inhibitor JNJ-40346527 Attenuates Microglial Proliferation and Neurodegeneration in P301S Mice. Brain 2019, 142, 3243–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosna, J.; Philipp, S.; Albay, R.; Reyes-Ruiz, J.M.; Baglietto-Vargas, D.; LaFerla, F.M.; Glabe, C.G. Early Long-Term Administration of the CSF1R Inhibitor PLX3397 Ablates Microglia and Reduces Accumulation of Intraneuronal Amyloid, Neuritic Plaque Deposition and Pre-Fibrillar Oligomers in 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Kim, H.; Yang, E.-J.; Kim, H.-S. Inhibition of STAT3 Phosphorylation Attenuates Impairments in Learning and Memory in 5XFAD Mice, an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Pharmacol Sci 2020, 143, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Pilot Open Labeled Study of Tacrolimus in Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Kheiri, G.; Dolatshahi, M.; Rahmani, F.; Rezaei, N. Role of P38/MAPKs in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Amyloid Beta Toxicity Targeted Therapy. Rev Neurosci 2018, 30, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maphis, N.; Jiang, S.; Xu, G.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Roy, S.M.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Watterson, D.M.; Lamb, B.T.; Bhaskar, K. Selective Suppression of the α Isoform of P38 MAPK Rescues Late-Stage Tau Pathology. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, M.S.; Son, S.H.; Jeon, S.H.; Do, J.; Kim, N.; Ju, Y.-J.; Lee, S.J.; Chung, E.K.; Inn, K.-S.; Kim, N.-J.; et al. A Selective P38α/β MAPK Inhibitor Alleviates Neuropathology and Cognitive Impairment, and Modulates Microglia Function in 5XFAD Mouse. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, N.; Delekate, A.; Breithausen, B.; Keppler, K.; Poll, S.; Schulte, T.; Peter, J.; Plescher, M.; Hansen, J.N.; Blank, N.; et al. P2Y1 Receptor Blockade Normalizes Network Dysfunction and Cognition in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2018, 215, 1649–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, S.; Claxton, A.; Baker, L.D.; Hanson, A.J.; Cholerton, B.; Trittschuh, E.H.; Dahl, D.; Caulder, E.; Neth, B.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Effects of Regular and Long-Acting Insulin on Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Pilot Clinical Trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2017, 57, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Kalaitzidis, G.; Malli, A.; Kalaitzoglou, D.; Myserlis, P.Gr.; Lioutas, V.-A. Intranasal Insulin in Alzheimer’s Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. J Neurol 2018, 265, 1497–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, S.; Raman, R.; Chow, T.W.; Rafii, M.S.; Sun, C.-K.; Rissman, R.A.; Donohue, M.C.; Brewer, J.B.; Jenkins, C.; Harless, K.; et al. Safety, Efficacy, and Feasibility of Intranasal Insulin for the Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease Dementia. JAMA Neurol 2020, 77, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gejl, M.; Gjedde, A.; Egefjord, L.; Møller, A.; Hansen, S.B.; Vang, K.; Rodell, A.; Brændgaard, H.; Gottrup, H.; Schacht, A.; et al. In Alzheimer’s Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Front Aging Neurosci 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchsinger, J.A.; Perez, T.; Chang, H.; Mehta, P.; Steffener, J.; Pradabhan, G.; Ichise, M.; Manly, J.; Devanand, D.P.; Bagiella, E. Metformin in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results of a Pilot Randomized Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2016, 51, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Mechanic-Hamilton, D.; Xie, S.X.; Combs, M.F.; Cappola, A.R.; Xie, L.; Detre, J.A.; Wolk, D.A.; Arnold, S.E. Effects of the Insulin Sensitizer Metformin in Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2017, 31, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, S.; Strosznajder, A.K.; Jeżyna, M.; Strosznajder, J.B. The Novel Role of PPAR Alpha in the Brain: Promising Target in Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurochem Res 2020, 45, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Hanyu, H.; Hirao, K.; Kanetaka, H.; Sakurai, H.; Iwamoto, T. Efficacy of PPAR-γ Agonist Pioglitazone in Mild Alzheimer Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2011, 32, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. AD-4833/TOMM40_303 Extension Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Pioglitazone to Slow Cognitive Decline in Participants with Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Biomarker Qualification for Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) Due to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of Pioglitazone in Delaying Its Onset.

- Therapeutic Advantages of Dual Targeting of PPAR-δ and PPAR-γ in an Experimental Model of Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis Alzheimers Dis 2018, 5, 01–08. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Kuang, W.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. A Phase II Randomized Trial of Sodium Oligomannate in Alzheimer’s Dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Chan, P.; Wang, T.; Hong, Z.; Wang, S.; Kuang, W.; He, J.; Pan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, Y.; et al. A 36-Week Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Phase 3 Clinical Trial of Sodium Oligomannate for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2021, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of AGB101 in Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Nighttime Agitation and Restless Legs Syndrome in People with Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Lin, C.-H.; Chen, P.-K.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chuo, L.-J.; Chen, Y.-S.; Tsai, G.E.; Lane, H.-Y. Benzoate, a D-Amino Acid Oxidase Inhibitor, for the Treatment of Early-Phase Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 75, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, H.-Y.; Tu, C.-H.; Lin, W.-C.; Lin, C.-H. Brain Activity of Benzoate, a D-Amino Acid Oxidase Inhibitor, in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 24, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Chen, P.-K.; Wang, S.-H.; Lane, H.-Y. Effect of Sodium Benzoate on Cognitive Function Among Patients With Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e216156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Riluzole in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of BHV-4157 in Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Quinn, J.F.; Raman, R.; Thomas, R.G.; Yurko-Mauro, K.; Nelson, E.B.; Van Dyck, C.; Galvin, J.E.; Emond, J.; Jack, C.R.; Weiner, M.; et al. Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 2010, 304, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. DHA Brain Delivery Trial (PreventE4).

- Bhatt, D.L.; Hull, M.A.; Song, M.; Van Hulle, C.; Carlsson, C.; Chapman, M.J.; Toth, P.P. Beyond Cardiovascular Medicine: Potential Future Uses of Icosapent Ethyl. European Heart Journal Supplements 2020, 22, J54–J64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belder, C.R.S.; Schott, J.M.; Fox, N.C. Preparing for Disease-Modifying Therapies in Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 782–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, L.S.; Barakos, J.; Dhadda, S.; Kanekiyo, M.; Reyderman, L.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D.; Swanson, C.J.; Sabbagh, M. ARIA in Patients Treated with Lecanemab (BAN2401) in a Phase 2 Study in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumiatti, V.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; Milelli, A.; Matera, R.; Melchiorre, C. Progress in Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease: An Update. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2008, 18, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myriad Genetics. Pharmaceutical Methods, Dosing Regimes and Dosage for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2005.

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research Method of Reducing Abeta42 and Treating Diseases. 2006.

- Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. Medicine Comprising Combination of Acetylcholine Esterase Inhibitor and 5-Substituted 2-Oxadiazolyl-1,6-Naphthyridin-2(1H)-One Derivative. 2005.

- Gallagher, M. Method for Improving Cognitive Function by Co-Administration of a GABAB Receptor Antagonist and an Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor. 2005.

- Prevention and Treatment of Cognitive Impairment. 2006.

- Huang Y, L.G.S.A. Substituted Amide Beta Secretase Inhibitors. 2006.

- Stamford AW, H.Y.L.G.S.C.V.J. Macrocyclic Beta-Secretase Inhibitors 2006.

- Gregory CW, S.P. Leuprolide Acetate and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors/NMDA Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Rabinoff M Novel Medication Treatment and Delivery Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease, Other Disorders with Memory Impairment, and Possible Treatment Strategies for Memory Improvement. 2006.

- Compositions and Methods for Treating CNS Disorders. 2007.

- Method for the Treatment of Cognitive Dysfunction. 2007.

- Parsons, C.G.; Danysz, W.; Dekundy, A.; Pulte, I. Memantine and Cholinesterase Inhibitors: Complementary Mechanisms in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotox Res 2013, 24, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, A.A. Multimodal Therapy in Clinical Psychology. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier, 2001; pp. 10193–10197.

- Mesiti, F.; Chavarria, D.; Gaspar, A.; Alcaro, S.; Borges, F. The Chemistry Toolbox of Multitarget-Directed Ligands for Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 181, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, Q.; Gu, K.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. Therapeutic Agents in Alzheimer’s Disease Through a Multi-Targetdirected Ligands Strategy: Recent Progress Based on Tacrine Core. Curr Top Med Chem 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Jangid, K.; Kumar, V.; Devi, B.; Arora, T.; Mishra, J.; Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, A.R.; Parkash, J.; Bhatti, J.S.; et al. Mannich Reaction Mediated Derivatization of Chromones and Their Biological Evaluations as Putative Multipotent Ligands for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. RSC Med Chem 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas Silva, M.; Dias, K.S.T.; Gontijo, V.S.; Ortiz, C.J.C.; Viegas Jr., C. Multi-Target Directed Drugs as a Modern Approach for Drug Design Towards Alzheimer’s Disease: An Update. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 3491–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, Y.; Ohie, T.; Yonekawa, Y.; Yonemoto, K.; Aizawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Taguchi, C.; et al. Coffee and Green Tea As a Large Source of Antioxidant Polyphenols in the Japanese Population. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; N. Setzer, W.; Fazel Nabavi, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Braidy, N.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Mohammad Nabavi, S. Insights Into Effects of Ellagic Acid on the Nervous System: A Mini Review. Curr Pharm Des 2016, 22, 1350–1360. [CrossRef]

- Heber, D.; Schulman, R.N.; Seeram, N.P. Pomegranates: Ancient Roots to Modern Medicine, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Quispe, C.; Castillo, C.M.S.; Caroca, R.; Lazo-Vélez, M.A.; Antonyak, H.; Polishchuk, A.; Lysiuk, R.; Oliinyk, P.; De Masi, L.; et al. Ellagic Acid: A Review on Its Natural Sources, Chemical Stability, and Therapeutic Potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.J.; Edwards, D.; Pun, S.; Chaliha, M.; Sultanbawa, Y. Profiling Ellagic Acid Content: The Importance of Form and Ascorbic Acid Levels. Food Research International 2014, 66, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.-Y.; Chan, C.-L.; Yang, Q.-Q.; Li, H.-B.; Zhang, D.; Ge, Y.-Y.; Gunaratne, A.; Ge, J.; Corke, H. Bioactive Compounds and Beneficial Functions of Sprouted Grains. In Sprouted Grains; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 191–246.

- Zafrilla, P.; Ferreres, F.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Effect of Processing and Storage on the Antioxidant Ellagic Acid Derivatives and Flavonoids of Red Raspberry ( Rubus Idaeus ) Jams. J Agric Food Chem 2001, 49, 3651–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sarrías, A.; García-Villalba, R.; Núñez-Sánchez, M.Á.; Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Zafrilla, P.; Mulero, J.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Espín, J.C. Identifying the Limits for Ellagic Acid Bioavailability: A Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study in Healthy Volunteers after Consumption of Pomegranate Extracts. J Funct Foods 2015, 19, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, S.A.; Abdulrahman, A.O.; Zamzami, M.A.; Khan, M.I. Urolithins: The Gut Based Polyphenol Metabolites of Ellagitannins in Cancer Prevention, a Review. Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccari, G.; Baldassari, S.; Ailuno, G.; Turrini, F.; Alfei, S.; Caviglioli, G. Formulation Strategies to Improve Oral Bioavailability of Ellagic Acid. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Landete, J.M. Ellagitannins, Ellagic Acid and Their Derived Metabolites: A Review about Source, Metabolism, Functions and Health. Food Research International 2011, 44, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.-L.; Giner, R.; Marín, M.; Recio, M. A Pharmacological Update of Ellagic Acid. Planta Med 2018, 84, 1068–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, R.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Cortés-Martín, A.; Ávila-Gálvez, M.Á.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C.; González-Sarrías, A. Urolithins: A Comprehensive Update on Their Metabolism, Bioactivity, and Associated Gut Microbiota. Mol Nutr Food Res 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary Polyphenols, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Curr Opin Food Sci 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, R.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Cortés-Martín, A.; Ávila-Gálvez, M.Á.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C.; González-Sarrías, A. Urolithins: A Comprehensive Update on Their Metabolism, Bioactivity, and Associated Gut Microbiota. Mol Nutr Food Res 2022, 66, e2101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimoto, H.; Shibata, M.; Myojin, Y.; Ito, H.; Sugimoto, Y.; Tai, A.; Hatano, T. In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Ellagitannin Metabolite Urolithin A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011, 21, 5901–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savi, M.; Bocchi, L.; Mena, P.; Dall’Asta, M.; Crozier, A.; Brighenti, F.; Stilli, D.; Del Rio, D. In Vivo Administration of Urolithin A and B Prevents the Occurrence of Cardiac Dysfunction in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guada, M.; Ganugula, R.; Vadhanam, M.; Ravi Kumar, M.N.V. Urolithin A Mitigates Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Inhibiting Renal Inflammation and Apoptosis in an Experimental Rat Model. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2017, 363, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Chandrashekharappa, S.; Bodduluri, S.R.; Baby, B. V.; Hegde, B.; Kotla, N.G.; Hiwale, A.A.; Saiyed, T.; Patel, P.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; et al. Enhancement of the Gut Barrier Integrity by a Microbial Metabolite through the Nrf2 Pathway. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, D.; Ganugula, R.; Arora, M.; Nabity, M.B.; Sheikh-Hamad, D.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Oral Delivery of Nanoparticle Urolithin A Normalizes Cellular Stress and Improves Survival in Mouse Model of Cisplatin-Induced AKI. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2019, 317, F1255–F1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Hou, N.; Yan, W.; Qin, Y.; Ye, Q.; Cheng, X.; Xiao, Q.; Bao, Y.; et al. Urolithin B, a Gut Microbiota Metabolite, Protects against Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via P62/Keap1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Pharmacol Res 2020, 153, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Chen, F.; Lei, J.; Li, Q.; Zhou, B. Activation of the MiR-34a-Mediated SIRT1/MTOR Signaling Pathway by Urolithin A Attenuates d-Galactose-Induced Brain Aging in Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Liao, J.; Shen, K.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Tian, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, B.; Pan, H. Protective Effect of Urolithin a on Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Mice via Modulation of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 129, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Henning, S.M.; Chan, B.; Long, J.; Zhong, J.; Acin-Perez, R.; Petcherski, A.; Shirihai, O.; Heber, D.; et al. Ellagic Acid and Its Microbial Metabolite Urolithin A Alleviate Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance in Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Ma, H.; Liu, W.; Niesen, D.B.; Shah, N.; Crews, R.; Rose, K.N.; Vattem, D.A.; Seeram, N.P. Pomegranate’s Neuroprotective Effects against Alzheimer’s Disease Are Mediated by Urolithins, Its Ellagitannin-Gut Microbial Derived Metabolites. ACS Chem Neurosci 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, B.; Ou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Ye, X.; Kong, X.; Long, D.; Sun, X.; et al. Urolithin A Attenuates Memory Impairment and Neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 Mice. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Gong, L.-F.; Wu, Y.-F.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, B.-J.; Wu, L.; Yu, K.-H. Urolithin A Targets the PI3K/Akt/NF-ΚB Pathways and Prevents IL-1β-Induced Inflammatory Response in Human Osteoarthritis: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Food Funct 2019, 10, 6135–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahsan, A.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, X.; Tang, W.; Liu, M.; Ma, S.; Jiang, L.; Hu, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z. Urolithin A-activated Autophagy but Not Mitophagy Protects against Ischemic Neuronal Injury by Inhibiting ER Stress in Vitro and in Vivo. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, N.; Das, A.; Biswas, N.; Gnyawali, S.; Singh, K.; Gorain, M.; Polcyn, C.; Khanna, S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Urolithin A Augments Angiogenic Pathways in Skeletal Muscle by Bolstering NAD+ and SIRT1. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.H.; Choi, G.E.; Kim, J.S.; Chae, C.W.; Lim, J.R.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Urolithin A Suppresses High Glucose-Induced Neuronal Amyloidogenesis by Modulating TGM2-Dependent ER-Mitochondria Contacts and Calcium Homeostasis. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Mo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Fu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, A. Urolithin A Alleviates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via PI3K/Akt Pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 486, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.-H.; Chen, W.-Q.; Shen, Z.-Y. Urolithin A Shows Anti-Atherosclerotic Activity via Activation of Class B Scavenger Receptor and Activation of Nef2 Signaling Pathway. Pharmacological Reports 2018, 70, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Haller, V.; Ritsch, A. A Novel Candidate for Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis: Urolithin B Decreases Lipid Plaque Deposition in ApoE −/− Mice and Increases Early Stages of Reverse Cholesterol Transport in Ox-LDL Treated Macrophages Cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toney, A.M.; Fan, R.; Xian, Y.; Chaidez, V.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Chung, S. Urolithin A, a Gut Metabolite, Improves Insulin Sensitivity Through Augmentation of Mitochondrial Function and Biogenesis. Obesity 2019, 27, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Weschka, D.; Bereswill, S.; Heimesaat, M.M. Immune-Modulatory Effects upon Oral Application of Cumin-Essential-Oil to Mice Suffering from Acute Campylobacteriosis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.O.; Kuerban, A.; Alshehri, Z.A.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Khan, J.A.; Khan, M.I. <p>Urolithins Attenuate Multiple Symptoms of Obesity in Rats Fed on a High-Fat Diet</P>. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2020, Volume 13, 3337–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.O.; Alzubaidi, M.Y.; Nadeem, M.S.; Khan, J.A.; Rather, I.A.; Khan, M.I. Effects of Urolithins on Obesity-Associated Gut Dysbiosis in Rats Fed on a High-Fat Diet. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2021, 72, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, S.; Sasaki, K.; Kondo, S.; Komatsu, W.; Yoshizawa, F.; Isoda, H.; Yagasaki, K. Antihyperuricemic Effect of Urolithin A in Cultured Hepatocytes and Model Mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.-H.; Ye, X.-J.; Li, Q.-F.; Gong, Z.; Cao, X.; Li, J.-H.; Zhao, S.-T.; Sun, X.-D.; He, X.-S.; Xuan, A.-G. Urolithin A Prevents Focal Cerebral Ischemic Injury via Attenuating Apoptosis and Neuroinflammation in Mice. Neuroscience 2020, 448, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.-X.; Li, X.; Deng, S.-Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Deng, X.; Han, B.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.-Z.; et al. Urolithin A Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Targeting Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. EBioMedicine 2021, 64, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.; Mouchiroud, L.; Andreux, P.A.; Katsyuba, E.; Moullan, N.; Nicolet-dit-Félix, A.A.; Williams, E.G.; Jha, P.; Lo Sasso, G.; Huzard, D.; et al. Urolithin A Induces Mitophagy and Prolongs Lifespan in C. Elegans and Increases Muscle Function in Rodents. Nat Med 2016, 22, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Kang, H.; Song, C.; Lei, Z.; Li, L.; Guo, J.; Xu, Y.; Guan, H.; Fang, Z.; Li, F. Urolithin A Inhibits the Catabolic Effect of TNFα on Nucleus Pulposus Cell and Alleviates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in Vivo. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, N.R.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Kolluru, V.; Ankem, M.; Damodaran, C.; Vadhanam, M. V. A Natural Molecule, Urolithin A, Downregulates Androgen Receptor Activation and Suppresses Growth of Prostate Cancer. Mol Carcinog 2018, 57, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Shi, C.; Pan, F.; Shao, J.; Feng, L.; Chen, G.; Ou, C.; Zhang, J.; Fu, W. Urolithin B Suppresses Tumor Growth in Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Inducing the Inactivation of Wnt/Β-catenin Signaling. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 17273–17282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.; Shi, X.C.; Xie, B.C.; Zhu, M.Q.; Chen, Y.; Chu, X.Y.; Cai, G.H.; Liu, M.; Yang, S.Z.; Mitchell, G.A.; et al. Urolithin A Exerts Antiobesity Effects through Enhancing Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis in Mice. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuohetaerbaike, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, N. nan; Kang, J.; Mao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Pancreas Protective Effects of Urolithin A on Type 2 Diabetic Mice Induced by High Fat and Streptozotocin via Regulating Autophagy and AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 250, 112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jasper, H.; Toan, S.; Muid, D.; Chang, X.; Zhou, H. Mitophagy Coordinates the Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response to Attenuate Inflammation-Mediated Myocardial Injury. Redox Biol 2021, 45, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, P.; D’Amico, D.; Andreux, P.A.; Laurila, P.-P.; Wohlwend, M.; Li, H.; Imamura de Lima, T.; Place, N.; Rinsch, C.; Zanou, N.; et al. Urolithin A Improves Muscle Function by Inducing Mitophagy in Muscular Dystrophy. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggia, R.; Turrini, F.; Villa, C.; Lacapra, C.; Zunin, P.; Parodi, B. Green Extraction from Pomegranate Marcs for the Production of Functional Foods and Cosmetics. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggia, R.; Turrini, F.; Roggeri, A.; Olivero, G.; Cisani, F.; Bonfiglio, T.; Summa, M.; Grilli, M.; Caviglioli, G.; Alfei, S.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Aged Brain: Impact of the Oral Administration of Ellagic Acid Microdispersion. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Turrini, F.; Catena, S.; Zunin, P.; Parodi, B.; Zuccari, G.; Pittaluga, A.M.; Boggia, R. Preparation of Ellagic Acid Micro and Nano Formulations with Amazingly Increased Water Solubility by Its Entrapment in Pectin or Non-PAMAM Dendrimers Suitable for Clinical Applications. New Journal of Chemistry 2019, 43, 2438–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and Hydrolysable Tannins: Occurrence, Dietary Intake and Pharmacological Effects. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Barrio, R.; Truchado, P.; Ito, H.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. UV and MS Identification of Urolithins and Nasutins, the Bioavailable Metabolites of Ellagitannins and Ellagic Acid in Different Mammals. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; García-Villalba, R.; González-Sarrías, A.; Selma, M. V.; Espín, J.C. Ellagic Acid Metabolism by Human Gut Microbiota: Consistent Observation of Three Urolithin Phenotypes in Intervention Trials, Independent of Food Source, Age, and Health Status. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 6535–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneto, H.; Katakami, N.; Matsuhisa, M.; Matsuoka, T. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Progression of Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2010, 2010, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Francisco Marquez, M.; Pérez-González, A. Ellagic Acid: An Unusually Versatile Protector against Oxidative Stress. Chem Res Toxicol 2014, 27, 904–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Mazzone, G.; Alvarez-Diduk, R.; Marino, T.; Alvarez-Idaboy, J.R.; Russo, N. Food Antioxidants: Chemical Insights at the Molecular Level. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 2016, 7, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francenia Santos-Sánchez, N.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Antioxidant Compounds and Their Antioxidant Mechanism. In Antioxidants; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Álvarez-Diduk, R.; Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. N -Acetylserotonin and 6-Hydroxymelatonin against Oxidative Stress: Implications for the Overall Protection Exerted by Melatonin. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119, 8535–8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.M.; Valentão, P.; Pereira, J.A.; Andrade, P.B. Phenolics: From Chemistry to Biology. Molecules 2009, 14, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbaliferiz, S.; Iranshahi, M. Prooxidant Activity of Polyphenols, Flavonoids, Anthocyanins and Carotenoids: Updated Review of Mechanisms and Catalyzing Metals. Phytotherapy Research 2016, 30, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Domenicotti, C. Polyester-Based Dendrimer Nanoparticles Combined with Etoposide Have an Improved Cytotoxic and Pro-Oxidant Effect on Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olas, B. Berry Phenolic Antioxidants – Implications for Human Health? Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P. Berry Fruits for Cancer Prevention: Current Status and Future Prospects. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Jamieson, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Bishayee, A. Neuroprotective Potential of Ellagic Acid: A Critical Review. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 1211–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Jagan Mohan Rao, L.; Shivanandappa, T. Isolation of Ellagic Acid from the Aqueous Extract of the Roots of Decalepis Hamiltonii: Antioxidant Activity and Cytoprotective Effect. Food Chem 2007, 103, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.O.; Damaceno Alves, A.; Almeida, D.A.T. de; Balogun, S.O.; de Oliveira, R.G.; Aires Aguiar, A.; Soares, I.M.; Marson-Ascêncio, P.G.; Ascêncio, S.D.; de Oliveira Martins, D.T. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory and Mechanism of Action of Extract of Macrosiphonia Longiflora (Desf.) Müll. Arg. J Ethnopharmacol 2014, 154, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Luo, H.; Xu, M.; Zhai, M.; Guo, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, L. Dynamic Changes in Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity during Pecan (Carya Illinoinensis) Kernel Ripening and Its Phenolics Profiles. Molecules 2018, 23, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, D.C.; Vo, P.H.; Coggeshall, M. V.; Lin, C.-H. Identification and Characterization of Phenolic Compounds in Black Walnut Kernels. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 4503–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramoniam, A.; Ambrose, Ss.; Solairaj, P. Hepatoprotective Activity of Active Fractions of Thespesia Lampas Dalz and Gibs (Malvaceae). J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2012, 3, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Britto Policarpi, P.; Turcatto, L.; Demoliner, F.; Ferrari, R.A.; Bascuñan, V.L.A.F.; Ramos, J.C.; Jachmanián, I.; Vitali, L.; Micke, G.A.; Block, J.M. Nutritional Potential, Chemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Chichá (Sterculia Striata) Nuts and Its by-Products. Food Research International 2018, 106, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, H.-C.; Wu, W.-T.; Huang, H.-S.; Wu, M.-C. Antimicrobial Activities of Various Fractions of Longan ( Dimocarpus Longan Lour. Fen Ke) Seed Extract. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2014, 65, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.; De la Garza, H.; Wong-Paz, J.; Aguilar, C.N.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.; Castro-López, C.; Aguilera-Carbó, A. Polyphenolic Content, in Vitro Antioxidant Activity and Chemical Composition of Extract from Nephelium Lappaceum L. (Mexican Rambutan) Husk. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2017, 10, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, A.; Gudej, J. Investigation into Biologically Active Constituents of Geum Rivale L. Acta Pol Pharm 2013, 70, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Sun, C.; Yang, J.; Shi, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wan, H. Evaluation of the Hepatoprotective and Antioxidant Activities of Rubus Parvifolius L. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2011, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Lim, S.S.; Lee, O.-H.; Kang, I.-J. Bioactivity-Guided Isolation and Identification of Anti-Adipogenic Compounds from Sanguisorba Officinalis. Pharm Biol 2017, 55, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.P.; Suzuki, K.; Derek, T.; Ozeki, M.; Okubo, T. Clinical Evaluation of Emblica Officinalis Gatertn (Amla) in Healthy Human Subjects: Health Benefits and Safety Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Placebo-Controlled Study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2020, 17, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Moreira, I.; Arnaez, E.; Quesada, S.; Azofeifa, G.; Vargas, F.; Alvarado, D.; Chen, P. Flavonoids and Ellagitannins Characterization, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities of Phyllanthus Acuminatus Vahl. Plants 2017, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Costa, C.; Moulay, L.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagic Acid Derivatives, Ellagitannins, Proanthocyanidins and Other Phenolics, Vitamin C and Antioxidant Capacity of Two Powder Products from Camu-Camu Fruit (Myrciaria Dubia). Food Chem 2013, 139, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado-Silva, C.; Pozo-Bayón, M.; Osorio, C. Targeted Metabolomic Analysis of Polyphenols with Antioxidant Activity in Sour Guava (Psidium Friedrichsthalianum Nied.) Fruit. Molecules 2016, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayanan, S.; Chandran, R.; Thankarajan, S.; Abrahamse, H.; Thangaraj, P. Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Bacterial Activity of Syzygium Calophyllifolium Walp. Fruit. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajera, H.P.; Gevariya, S.N.; Hirpara, D.G.; Patel, S. V.; Golakiya, B.A. Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Functionality Associated with Phenolic Constituents from Fruit Parts of Indigenous Black Jamun (Syzygium Cumini L.) Landraces. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 3180–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, L.M.; Porte, A.; de Oliveira Godoy, R.L.; da Costa Souza, M.; Pacheco, S.; de Araujo Santiago, M.C.P.; Gouvêa, A.C.M.S.; da Silva de Mattos do Nascimento, L.; Borguini, R.G. Chemical Characterization of Myrciaria Floribunda (H. West Ex Willd) Fruit. Food Chem 2018, 248, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão, T.R.; de Araújo, A.A.; Soares, L.A.L.; de Moraes Ramos, R.T.; Bezerra, I.C.F.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; de Souza Neto, M.A.; Melo, M.C.N.; de Araújo, R.F.; de Aguiar Guerra, A.C.V.; et al. Crude Extract and Fractions from Eugenia Uniflora Linn Leaves Showed Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activities. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Ferranti, P.; Nicoletti, R.; Perrotta, G.M.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. Establishment of Pressurized-Liquid Extraction by Response Surface Methodology Approach Coupled to HPLC-DAD-TOF-MS for the Determination of Phenolic Compounds of Myrtle Leaves. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, 3547–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.F.; Espindola, P.P. de T.; Torquato, H.F. V.; Vital, W.D.; Justo, G.Z.; Silva, D.B.; Carollo, C.A.; de Picoli Souza, K.; Paredes-Gamero, E.J.; dos Santos, E.L. Leaf and Root Extracts from Campomanesia Adamantium (Myrtaceae) Promote Apoptotic Death of Leukemic Cells via Activation of Intracellular Calcium and Caspase-3. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Puig, C.G.; Reigosa, M.J.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Pedrol, N. Unravelling the Bioherbicide Potential of Eucalyptus Globulus Labill: Biochemistry and Effects of Its Aqueous Extract. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, A.D.T.; Chaliha, M.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Netzel, M.E. Nutritional Characteristics and Antimicrobial Activity of Australian Grown Feijoa (Acca Sellowiana). Foods 2019, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Alvarez, M.-C.; Moussa, I.; Njomnang Soh, P.; Nongonierma, R.; Abdoulaye, A.; Nicolau-Travers, M.-L.; Fabre, A.; Wdzieczak-Bakala, J.; Ahond, A.; Poupat, C.; et al. Both Plants Sebastiania Chamaelea from Niger and Chrozophora Senegalensis from Senegal Used in African Traditional Medicine in Malaria Treatment Share a Same Active Principle. J Ethnopharmacol 2013, 149, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siraj, Md.A.; Shilpi, J.A.; Hossain, Md.G.; Uddin, S.J.; Islam, Md.K.; Jahan, I.A.; Hossain, H. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Acalypha Hispida Leaf and Analysis of Its Major Bioactive Polyphenols by HPLC. Adv Pharm Bull 2016, 6, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Pacheco, A.; Escalona Arranz, J.; Beaven, M.; Peres-Roses, R.; Gámez, Y.; Camacho-Pozo, M.; Maury, G.; de Macedo, M.; Cos, P.; Tavares, J.; et al. Bioassay-Guided In Vitro Study of the Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Properties of the Leaves from Excoecaria Lucida Sw. Pharmacognosy Res 2017, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-S.; Jung, S.-H.; Kim, J. Polyphenols from Euphorbia Pekinensis Inhibit AGEs Formation In Vitro and Vessel Dilation in Larval Zebrafish In Vivo. Planta Med 2018, 84, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugroho, A.; Rhim, T.-J.; Choi, M.-Y.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, Y.-C.; Kim, M.-S.; Park, H.-J. Simultaneous Analysis and Peroxynitrite-Scavenging Activity of Galloylated Flavonoid Glycosides and Ellagic Acid in Euphorbia Supina. Arch Pharm Res 2014, 37, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-H.; Kao, M.-Y.; Wu, S.-C.; Lo, D.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chang, J.-C.; Chiou, R.Y.-Y. Oral Administration of Trapa Taiwanensis Nakai Fruit Skin Extracts Conferring Hepatoprotection from CCl 4 -Caused Injury. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 3686–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, Y.; Khan, M. Chromatographic Profiling of Ellagic Acid in Woodfordia Fruticosa Flowers and Their Gastroprotective Potential in Ethanol-Induced Ulcers in Rats. Pharmacognosy Res 2016, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.O.M.; Vilegas, W.; Tangerina, M.M.P.; Arunachalam, K.; Balogun, S.O.; Orlandi-Mattos, P.E.; Colodel, E.M.; Martins, D.T. de O. Lafoensia Pacari A. St.-Hil.: Wound Healing Activity and Mechanism of Action of Standardized Hydroethanolic Leaves Extract. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 219, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Kwon, M.J.; Yoo, J.Y.; Choi, H.-J.; Ahn, Y.-J. Antiviral Activity and Possible Mode of Action of Ellagic Acid Identified in Lagerstroemia Speciosa Leaves toward Human Rhinoviruses. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Juan, C.-W.J.; Juan, C.-W.J.; Lin, C.-S.; Lin, C.-S.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Chang, C.-L.; Chang, C.-L. NEUROPROTECTIVE EFFECT OF TERMINALIA CHEBULA EXTRACTS AND ELLAGIC ACID IN PC12 CELLS. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 2017, 14, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, R.; Pandey, A.K. Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Activities of Terminalia Bellirica Fruit in Alloxan Induced Diabetic Rats. South African Journal of Botany 2020, 130, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Aouadhi, C.; Kaddour, R.; Gruber, M.; Zargouni, H.; Zaouali, W.; Hamida, N. Ben; Nasri, M. Ben; Ouerghi, Z.; Hosni, K. Comparison of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Two Cultivated Cistus Species from Tunisia. Bioscience Journal 2016, 32, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, K.W.; Mat-Junit, S.; Ismail, A.; Aminudin, N.; Abdul-Aziz, A. Polyphenols in Barringtonia Racemosa and Their Protection against Oxidation of LDL, Serum and Haemoglobin. Food Chem 2014, 146, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreres, F.; Grosso, C.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B. Ellagic Acid and Derivatives from Cochlospermum Angolensis Welw. Extracts: HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS n Profiling, Quantification and In Vitro Anti-depressant, Anti-cholinesterase and Anti-oxidant Activities. Phytochemical Analysis 2013, 24, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnappa, P.; Venkatarangaiah, K.; Venkatesh; Shivamogga Rajanna, S.K.; Kashi Prakash Gupta, R. Antioxidant and Prophylactic Effects of Delonix Elata L., Stem Bark Extracts, and Flavonoid Isolated Quercetin against Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sumi, S.A.; Siraj, Md.A.; Hossain, A.; Mia, Md.S.; Afrin, S.; Rahman, Md.M. Investigation of the Key Pharmacological Activities of Ficus Racemosa and Analysis of Its Major Bioactive Polyphenols by HPLC-DAD. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.-J.; Chen, J.-H.; Ng, L.T. Hepatoprotection of Gentiana Scabra Extract and Polyphenols in Liver of Carbon Tetrachloride-Intoxicated Mice. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology 2011, 30, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, X.; Guan, Y.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.-F. Chromatographic Fingerprint and the Simultaneous Determination of Five Bioactive Components of Geranium Carolinianum L. Water Extract by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 8740–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Chen, P. Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Analysis of African Mango ( Irvingia Gabonensis ) Seeds, Extract, and Related Dietary Supplements. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 8703–8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alañón, M.E.; Palomo, I.; Rodríguez, L.; Fuentes, E.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. Antiplatelet Activity of Natural Bioactive Extracts from Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) and Its By-Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldisserotto, A.; Buso, P.; Radice, M.; Dissette, V.; Lampronti, I.; Gambari, R.; Manfredini, S.; Vertuani, S. Moringa Oleifera Leaf Extracts as Multifunctional Ingredients for “Natural and Organic” Sunscreens and Photoprotective Preparations. Molecules 2018, 23, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RK Abbas; AA Al-Mushhin; FS Elsharbasy; KO Ashiry Reduce the Risk of Oxidation and Pathogenic Bacteria Activity by Moringa Oleifera Different Leaf Extract Grown in Sudan. . J Microb Biochem Technol 2020, 12, 427. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Kim, M.; Jang, Y.; Lee, H.W.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Park, H.W.; Le Dang, Q.; Kim, J.-C. Characterization and Mechanisms of Anti-Influenza Virus Metabolites Isolated from the Vietnamese Medicinal Plant Polygonum Chinense. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Talcott, S.T. Fruit Maturity and Juice Extraction Influences Ellagic Acid Derivatives and Other Antioxidant Polyphenolics in Muscadine Grapes. J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott, S.T.; Lee, J.-H. Ellagic Acid and Flavonoid Antioxidant Content of Muscadine Wine and Juice. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 3186–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfoudhi, A.; Prencipe, F.P.; Mighri, Z.; Pellati, F. Metabolite Profiling of Polyphenols in the Tunisian Plant Tamarix Aphylla (L.) Karst. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2014, 99, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, B.; Daningtia, N.R.; Yuliani, G.A.; Yuniarti, W.M. Effects of a Standardized 40% Ellagic Acid Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) Extract on Seminiferous Tubule Histopathology, Diameter, and Epithelium Thickness in Albino Wistar Rats after Heat Exposure. Vet World 2019, 12, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Özen, C.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Chigurupati, S.; Patra, J.K.; Horbanczuk, J.O.; Jóźwik, A.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Uhrin, P.; Atanasov, A.G. Vasculoprotective Effects of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.). Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.-M.; Jeon, S.-Y.; Sohng, B.-H.; Kim, J.-G.; Lee, J.-M.; Lee, K.-B.; Jeong, H.-H.; Hur, J.-M.; Kang, Y.-H.; Song, K.-S. β-Secretase(BACE1) Inhibitors from Pomegranate (Punica Granatum) Husk. Arch Pharm Res 2005, 28, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojanathammanee, L.; Puig, K.L.; Combs, C.K. Pomegranate Polyphenols and Extract Inhibit Nuclear Factor of Activated T-Cell Activity and Microglial Activation In Vitro and in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. J Nutr 2013, 143, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R.E.; Shah, A.; Fagan, A.M.; Schwetye, K.E.; Parsadanian, M.; Schulman, R.N.; Finn, M.B.; Holtzman, D.M. Pomegranate Juice Decreases Amyloid Load and Improves Behavior in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Dis 2006, 24, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food B.

- Williams, D.J.; Edwards, D.; Pun, S.; Chaliha, M.; Burren, B.; Tinggi, U.; Sultanbawa, Y. Organic Acids in Kakadu Plum ( Terminalia Ferdinandiana ): The Good (Ellagic), the Bad (Oxalic) and the Uncertain (Ascorbic). Food Research International 2016, 89, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masci, A.; Coccia, A.; Lendaro, E.; Mosca, L.; Paolicelli, P.; Cesa, S. Evaluation of Different Extraction Methods from Pomegranate Whole Fruit or Peels and the Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activity of the Polyphenolic Fraction. Food Chem 2016, 202, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Määttä-Riihinen, K.R.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Törrönen, A.R. Identification and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Berries of Fragaria and Rubus Species (Family Rosaceae). J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 6178–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Esmaeilizadeh, M. Pharmacological Properties of Salvia Officinalis and Its Components. J Tradit Complement Med 2017, 7, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojanathammanee, L.; Puig, K.L.; Combs, C.K. Pomegranate Polyphenols and Extract Inhibit Nuclear Factor of Activated T-Cell Activity and Microglial Activation In Vitro and in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. J Nutr 2013, 143, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, M.; Sun, G.; Liu, R. Ellagic Acid Promotes Aβ42 Fibrillization and Inhibits Aβ42-Induced Neurotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 390, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Panchal, S.S.; Shah, A. Ellagic Acid: Insights into Its Neuroprotective and Cognitive Enhancement Effects in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2018, 175, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, V.B.; Askari, V.R.; Mousavi, S.H. Ellagic Acid Reveals Promising Anti-Aging Effects against d-Galactose-Induced Aging on Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line, SH-SY5Y: A Mechanistic Study. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 108, 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjaeraa, C.; Nånberg, E. Effect of Ellagic Acid on Proliferation, Cell Adhesion and Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2009, 63, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredsson, C.F.; Rendel, F.; Liang, Q.-L.; Sundström, B.E.; Nånberg, E. Altered Sensitivity to Ellagic Acid in Neuroblastoma Cells Undergoing Differentiation with 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-Acetate and All-Trans Retinoic Acid. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2015, 76, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tzou, B.; Liu, Y.; Tsai, M.; Shyue, S.; Tzeng, S. Inhibition of Cadmium-induced Oxidative Injury in Rat Primary Astrocytes by the Addition of Antioxidants and the Reduction of Intracellular Calcium. J Cell Biochem 2008, 103, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabiraj, P.; Marin, J.E.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Zubia, E.; Narayan, M. Ellagic Acid Mitigates SNO-PDI Induced Aggregation of Parkinsonian Biomarkers. ACS Chem Neurosci 2014, 5, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Deng, R.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Kebaituli, G.; Li, X.; Liu, R. Ellagic Acid Protects against Neuron Damage in Ischemic Stroke through Regulating the Ratio of Bcl-2/Bax Expression. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2017, 42, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, W.A.; Jeyabalan, J.; Kichambre, S.; Gupta, R.C. Oxidatively Generated DNA Damage after Cu(II) Catalysis of Dopamine and Related Catecholamine Neurotransmitters and Neurotoxins: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 50, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, H.A.; Masoud, M.A.; Maher, O.W. Prophylactic Effects of Ellagic Acid and Rosmarinic Acid on Doxorubicin-induced Neurotoxicity in Rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudarzi, M.; Amiri, S.; Nesari, A.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Mansouri, E.; Mehrzadi, S. The Possible Neuroprotective Effect of Ellagic Acid on Sodium Arsenate-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats. Life Sci 2018, 198, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firdaus, F.; Zafeer, M.F.; Anis, E.; Ahmad, M.; Afzal, M. Ellagic Acid Attenuates Arsenic Induced Neuro-Inflammation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Associated Apoptosis. Toxicol Rep 2018, 5, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudarzi, M.; Mombeini, M.A.; Fatemi, I.; Aminzadeh, A.; Kalantari, H.; Nesari, A.; Najafzadehvarzi, H.; Mehrzadi, S. Neuroprotective Effects of Ellagic Acid against Acrylamide-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats. Neurol Res 2019, 41, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanadgol, N.; Golab, F.; Tashakkor, Z.; Taki, N.; Moradi Kouchi, S.; Mostafaie, A.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Taghizadeh, G.; Sharifzadeh, M. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Neuroprotective Effects of Ellagic Acid on Cuprizone-Induced Acute Demyelination through Limitation of Microgliosis, Adjustment of CXCL12/IL-17/IL-11 Axis and Restriction of Mature Oligodendrocytes Apoptosis. Pharm Biol 2017, 55, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, E.A.; Vodhanel, J.; Abushaban, A. The Modulatory Effects of Ellagic Acid and Vitamin E Succinate on TCDD-induced Oxidative Stress in Different Brain Regions of Rats after Subchronic Exposure. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2004, 18, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoun, E.A.; Vodhanel, J.; Holden, B.; Abushaban, A. The Effects of Ellagic Acid and Vitamin E Succinate on Antioxidant Enzymes Activities and Glutathione Levels in Different Brain Regions of Rats After Subchronic Exposure to TCDD. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2006, 69, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, A.; Gok, O.; Beyaz, S.; Arslan, E.; Erman, O.; Ağca, C.A. The Preventive Effect of Ellagic Acid on Brain Damage in Rats via Regulating of Nrf-2, NF-kB and Apoptotic Pathway. J Food Biochem 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.T.; Farbood, Y.; Naghizadeh, B.; Shabani, S.; Mirshekar, M.A.; Sarkaki, A. Beneficial Effects of Ellagic Acid against Animal Models of Scopolamine- and Diazepam-Induced Cognitive Impairments. Pharm Biol 2016, 54, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farbood, Y.; Sarkaki, A.; Dolatshahi, M.; Taqhi Mansouri, S.M.; Khodadadi, A. Ellagic Acid Protects the Brain Against 6-Hydroxydopamine Induced Neuroinflammation in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Basic Clin Neurosci 2015, 6, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Dolatshahi, M.; Mansouri, S.M.T.; Khodadadi, A. Neuroprotective Effects of Ellagic Acid in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Med Iran 2016, 54, 494–502. [Google Scholar]