1. Introduction

International carbon offset markets and global carbon markets aim to channel carbon funding for climate change management towards developing nations. They are crucial for promoting green growth in East Africa/Ethiopia, particularly in sustainable agriculture and renewable energy generation. By establishing well defined carbon permits, these markets boost abatement, technology transfer, and investment in low carbon technologies and services. In fewer than ten years, the volume, value, and scope of global carbon trading have all increased dramatically, according to Ervine (2014). According to United Nations Framework convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) website assessed on January 2022), there were over 8,475 registered clean development mechanisms (CDM) Projects in the world wide. According to UNEP (2016), the total amount of Certified Emission Reduction (CER) permits issued has also climbed to more than $1.7 billion. Companies, governments, and people purchased approximately 1 billion carbon offsets in the voluntary carbon markets during the past ten years, spending slightly under $4.5 billion on renewable energy and conservation (Ecosystems Marketplace, 2016). Globally, compliance carbon pricing schemes have been tested in the voluntary markets (Climate Policy Initiative, 2015).

Climate change poses challenges to Sub Saharan African nations, causing increased fires, floods, and droughts. Forests provide essential services, but underinvestment in environmental preservation leads to global warming. Market based assessments encourage service owners to control use.

In 1992, Malaysia initiated the first carbon offset project using forests, sequestering 15.6 million tons of carbon dioxide and recovering 25,000 hectares of rainforest, equivalent to 4.25 million tons of carbon (Auckland et al., 2002). Carbon sequestration projects are significant financial inflows for developing nations due to their investment in this area. According to Tipper (2002), there is evidence from experience that carbon sequestration initiatives in developing nations can enhance local livelihoods and reduce rural poverty when implemented in collaboration with small land holders. Carbon sequestration initiatives could potentially promote environmental preservation, as Ethiopia consumed 100 kwh of electricity per capital in 2022-2023.The massive Grand Renaissance hydropower facility (4.8 GW) is set to run at full capacity, but negotiations with Egypt and Sudan are delaying its completion. Additionally, a 2 GW dam is being built. 88% of the energy is provided by biomass. However, it had one of the lowest global consumptions. Other energy sources used by many households include charcoal, gas, dung, and firewood. Wood charcoal, widely used in country stores and hotels for coffee brewing, contributes to deforestation, affecting 140,000 hectares annually due to lack of electricity and alternatives.

Population growth and unemployment increase forest fuel demand, with 90% coming from biomass. Ethiopia’s carbon trading faces challenges and future prospects, with supply gap exceeding 58 tons cubic meters.

2. Methodology

Entails calculating and confirming greenhouse gas emissions, producing carbon credits, and planning emission reduction initiatives. This credit can be exchanged on carbon markets and represents the emissions that the project prevented or reduced. Ethiopia faces significant hurdles in accurately measuring and monitoring emissions due to a lack of resources and infrastructure for carbon trading. To encourage the use of carbon trading as a mechanism for mitigating climate change, stakeholders must also have their capacity built and their knowledge raised.

3.0. The Kyoto Protocol, the Structure of the Ethiopian Economy and Source of Carbon Emissions3.1. The Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol, a 1997 international agreement, aims to reduce the six principal greenhouse gases: CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, and SF6.The UN 1998 treaty aimed to decrease global emissions by 5.2% from 1990 levels by the end of 2012, with most industrialized nations agreeing to legally binding emission objectives.

The Kyoto Protocol enables Annex I nations to reduce emissions through GHG removals, International Emissions Trading, and carbon initiatives, supporting non-Annex I countries’ cap requirements and sustainable development in developing nations. (Carbon Trust 2009). It is challenging to verify whether these claimed reductions in emissions are real (World Bank 2010).

3.2. Economics/Theory

Carbon trading requires emission quantification and permit exchange for emitters, with property rights playing a crucial role in the economics and theory of carbon trading (Goldenberg et al. 1996). In particular, the issue of climate change is one in which greenhouse gas emitters escape the full financial consequences of their activities (IMF 2008). Emitters incur input and additional costs, which are divided into internalized or external costs and private or internal costs, which are entirely absorbed by the decision maker. (Halsnaes et al. 2007). External expenses, such as greenhouse gas emissions, can impact the welfare of others and the environment, affecting both present and future human wellbeing. (Stern 2007; Tothet al. 2001). It is possible to evaluate and translate these external expenses into a single (monetary) unit.

The justification is that the emitter can internalize external costs by adding them to their private costs, thereby bearing the entire social cost of their activities. (IMF 2008).

Ethiopia’s economy shifts from agriculture to industry, with building subsector growth driving CO2 emissions. 80% priced through fuel excise taxes in 2021, with road transport sector having the highest priced emissions.

3.3. Carbon Emission Sources in Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s carbon emissions, primarily from livestock and land use change, increased by 4.8% in 2020, accounting for 0.37% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) production.

3.3.1. a. Agriculture

Ethiopia’s agricultural sector, largely reliant on rainfall, faces low production despite improved irrigation and fertilizer, and poor land management contributes to land degradation.

3.3.1. b. Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry

Ethiopia’s wood lands are under stress from factors like forest clearance, land use conversion, illegal extraction, human settlement, forest fires, and infrastructure construction. Sustainable forest management could reduce carbon footprint by 2.76 billion tons.

Rural and urban residents rely on firewood and charcoal for food and coffee, despite the lack of alternative energy sources. The government is focusing on Reducing Emission for Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but native wood is cleared for charcoal and firewood production. There are no restrictions on distant work or other options for rural residents.

3.3.1. c. Energy

Between 1990 and 2012, the world’s primary energy supply more than doubled. In 2012, 93% of the energy came from biofuels and trash, with fossil fuels coming in second at 6% and renewable at 1%. Winds, geothermal, and hydropower comprise most of the renewable energy used in the electric grid system. According to Ethiopia’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), 77% of the population uses wood as fuel because they do not have access to contemporary energy sources. Ethiopia will boost biogas production and lessen the need for fuel wood by encouraging efficiency, given that fuel wood is used by rural households and they do not have access to power (USAID, 2015).

Since hydro power accounts for more than 98% of the total power generation capacity and is supplemented by the use of both on and off grid diesel generators managed by Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP), the electric power sector only contributes very low emissions. The energy sector’s current emissions make up less than 5 Mt CO2e, or 3% of all emissions in the nation. (The average percentage of a nation’s GHG emissions that comes from the production of electricity worldwide is greater than 25 %.)

3.3.1. d Transport, Industry and Building

In transport: -Road transportation, especially freight and construction vehicles, accounts for 75% of emissions, with private passenger cars contributing less. Another major contributor to transport related emissions is air travel (23%). Inland water transportation emits very little. Industries: - Industry contributes only 3% of greenhouse gas emissions overall, considering its relatively tiny percentage of organized industrial economic activity. Cement is the single largest industrial source of emissions at roughly 2 Mt CO2e, or 50% of the 4 Mt CO2e emissions from industry. Mining comes in second at 32%, while the textile and leather industry comes in third at 17%. Only around 2% of companies’ emissions come from the steel, other engineering, chemicals (including fertilizer), pulp and paper, and food processing industries combined.

Buildings: - contribute around 3%, or 5 Mt CO2e, to the emissions of today. The primary causes are the usage of private off grid power generators in cities (2 Mt of CO2e) and emissions associated with solid and liquid waste (3 Mt of CO2e) test the emissions of GHGs.

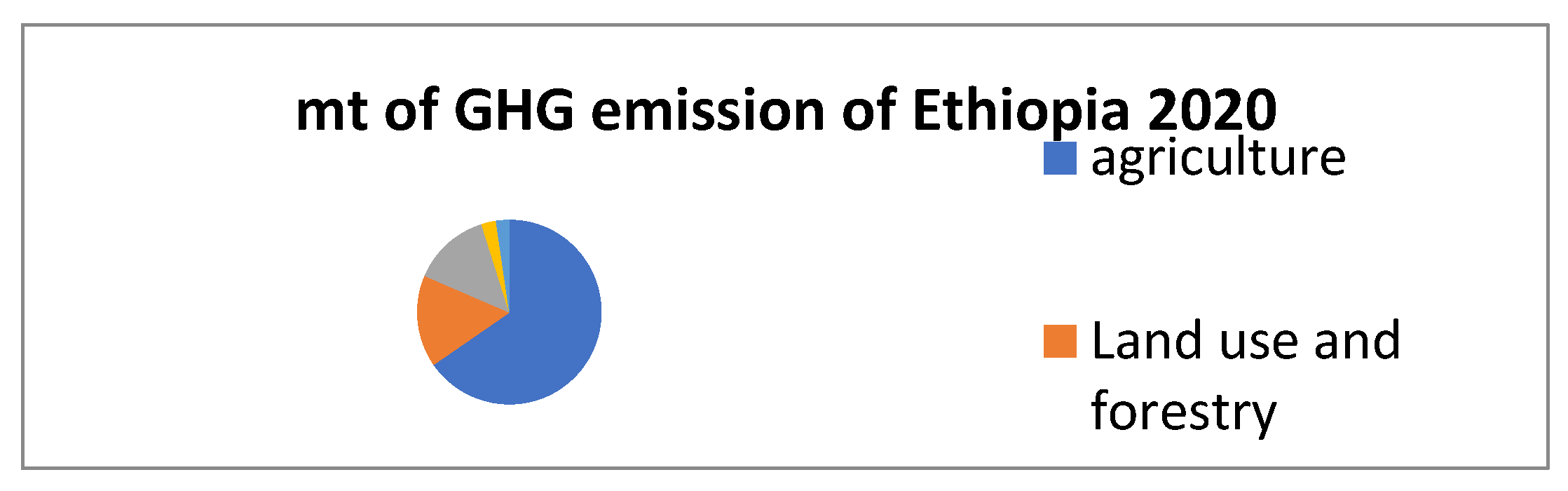

Table 1.

the GHG Emission of the sector by Metric tonnes and percentage of Ethiopia 2020.

Table 1.

the GHG Emission of the sector by Metric tonnes and percentage of Ethiopia 2020.

| No |

GHG sources |

Metric Tonne (Mt) of Emission |

% |

| 1 |

Agriculture |

130 |

77.6 |

| 2 |

Land use and forestry |

32 |

19.1 |

| 3 |

energy |

27.1 |

16.7 |

| 4 |

Waste |

5.1 |

2.56 |

| 5 |

industrial process |

4.6 |

2.31 |

Figure 1.

The sector of carbon sources versus the percentage of emission 2020.

Figure 1.

The sector of carbon sources versus the percentage of emission 2020.

3.4. Green House Gas (GHG) in Ethiopia

3.4.1. Methane (CH₄): Livestock, rice production, and fugitive emissions contribute to methane emissions, with cattle, sheep, and goats generating methane through enteric fermentation.

3.4.2 Carbon Dioxide (CO₂): The burning of fossil fuels, industrial processes, land use changes, transportation, and residential and commercial sectors contribute to significant CO2 emissions in Ethiopia, with deforestation potentially liberating atmospherically stored carbon.

3.4.3. Nitrous Oxide (N₂O): Nitrous oxide emissions are caused by synthetic fertilizers, soil disturbance, and industrial processes, including agricultural methods, soil management techniques, and certain industrial operations.

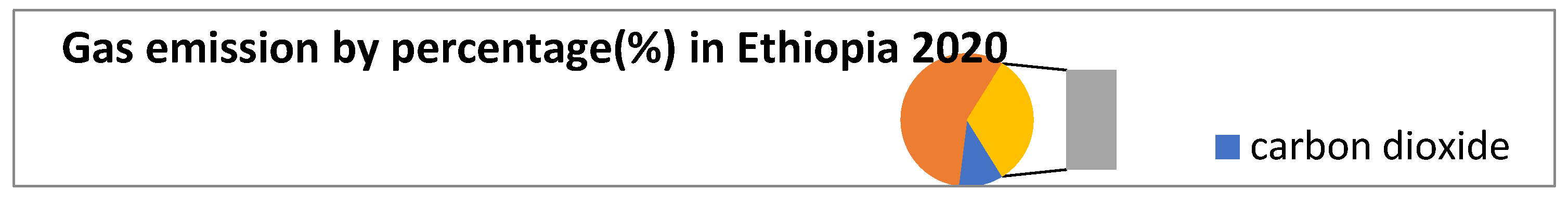

Table 2.

Kinds of GHG, comparison of their effects, and percentage in Ethiopia in 2020.

Table 2.

Kinds of GHG, comparison of their effects, and percentage in Ethiopia in 2020.

| No |

Types of GHG |

Comparison effect with stay in the atmosphere |

Percentage (%) |

| 1 |

Carbon dioxide |

1000yrs, 1/80 of CH4

|

10.8 |

| 2 |

Methane |

20yrs and 80CO2

|

56.6 |

| 3 |

Nitrous oxides |

120yrs and 180CO2

|

32.1 |

Figure 2.

The percentage of each GHG in Ethiopia in 2020.

Figure 2.

The percentage of each GHG in Ethiopia in 2020.

4.0. Wood Charcoal Production’s Effects on Ethiopian Green Economy

Nearly half of the world’s population and about 81% of Sub Saharan African (SSA) households rely on wood based biomass energy (firewood and charcoal in particular) for cooking and heating (AREAP, 2011). Wood based biomass as the main source of energy is reported at 94% in Ethiopia, (van Beukering, 2007). Fire wood and charcoal accounted for about 91% of Africa’s round wood production in 2000 (Falcão, 2008).

Due to a lack of sufficient alternative energy sources and poverty, the majority of Ethiopians cook using charcoal. They sell it to make ends meet. Not only that, but even with alternate energy sources, the majority of residents living in both rural and urban areas still utilize coal. They will be used as a trend for preparing and brewing coffee in every single home, hotel, restaurant, and even more places. Where people depart densely and earn money, the majority of the women concentrate on brewing coffee. Since charcoal cooks coffee better and sweeter than other methods, they utilize it for cooking instead of other fuels. Although there is a strategy in place by the government to control illegal deforestation and automate systems that generate zero carbon credits, the laws and regulations concerning the establishment of a green economy in the country are abhorrent. Because they depend on agriculture for their subsistence, the rural poor need a continuous strategy that leads to industry and finds alternate ways to meet their demands. They also need to be made aware of how deforestation contributes to global warming, and they need incentives to help them satisfy their demands.

If the issue is not resolved by the government’s strategy implemented locally instead of only through written plans without any action, it will affect the country’s ability to reduce global warming and seize the opportunity to enter the carbon market.

Figure 3.

The Figure is taken from a shop in Shegger City around Furi.

Figure 3.

The Figure is taken from a shop in Shegger City around Furi.

5.0. Policy Response to Climate Change in East Africa

Except Eritrea, every nation in sub-Saharan Africa has ratified and signed the 2015 Paris Agreement, which includes a pledge to carry out national climate policies and make nationally decided contributions. When it comes to climate plans and action, member states profit from the assistance provided by the African Union Commission and Regional Economic Communities. The cornerstone of the African climate change policy is Agenda 2063, which outlines coordinated efforts, independence, and financial resources for Africa to synchronize climate action at the continental, regional, and national levels. To increase the region’s capacity for adaptation and fortify itself against the negative effects of climate change, the East Africa Community created the Climate Change Policy (EACCCP) in 2009 (Apollo & Mbah, 2021). In order to increase agricultural output, resilience to climate change, and adaptation through technological innovation, nations in the region have founded the Eastern Africa Climate Smart Agriculture Platform (EACSAP) in 2014 (Apollo & Mbah, 2021; Price, 2018). The majority of the adaptation policy goals in the region are centered around disaster response, transportation, energy, forests, agriculture and food security, livelihoods, and coastal zones. However, regional policy coherence is limited by a lack of horizontal links across nations and programs (Price, 2018). Similarly, Apollo and Mbah (2021) emphasize that in order to maximize the execution of the current plans, it is critical that efforts to promote climate change education and innovation in East Africa are coordinated across the government, business community, civil society, and educational institutions. The majority of the nations in the area have concurrently created their own national climate change policies. The nation-specific climate policies, their areas of emphasis, and the steps needed to put them into practice are outlined in Table 8.1. The majority of the previously compiled policy documents appear to treat climate change as a technical issue requiring specialist solutions, and they treat it as such apart from a more comprehensive development agenda (Addaney, 2018; Apollo & Mbah, 2021; Orindi et al., 2005). This may be because, rather than focusing on climate change, the nation’s urgently need to address other development issues including unemployment and growth as well as poverty reduction. But as was previously said in-depth, climate change would have a negative short- and long-term impact on the region’s sustainable development. Weisser and colleagues (2014) contend that through knowledge and innovation, adaptation to climate change should be mainstreamed into the current livelihood coping mechanisms rather than just concentrating on new activities.

Ethiopia’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is a plan for lowering greenhouse gas emissions and preparing for the effects of climate change. It is a fundamental element of the Paris pact, an international pact designed to mitigate climate change. Ethiopia’s commitment to lowering greenhouse gas emissions and preparing for the effects of climate change is outlined in the country’s NDC. Ethiopia’s NDC, which covers the years 2015 through 2030, was submitted in 2016. By 2030, the nation wants to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 7% compared to business as usual.

This goal is consistent with the worldwide endeavor to keep the average global temperature increase to well below 20 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue measures to keep the increase to 1.50 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Ethiopia NDC prioritizes a number of important areas, such as waste management, transportation, energy, and agriculture. The nation wants to boost the usage of electric vehicles, raise the proportion of renewable energy in its energy mix, and increase energy efficiency. Ethiopia intends to advance climate-smart farming methods, boost soil carbon sequestration, and better water management.

Table 3.

Policy response to Climate changes in some East African countries.

Table 3.

Policy response to Climate changes in some East African countries.

| Country |

Policy |

Main objectives |

Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) Emissions |

| Ethiopia |

Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) strategy 2011 Updated NDC 2021 |

keep greenhouse emissions low |

69 percent to 14 percent of which is to be an unconditional effort |

| Burundi |

National Climate Change Policy 2012 Updated NDC 2021 |

Promote resilient climate development by coordinating restorative environmental activities |

3 percent by 2030, or 13percent with international support |

| Kenya |

National Climate Change Action Plan 2018−2022 National Climate Change Policy 2018 Climate Change Act 2016 Updated NDC 2020 |

Integrate climate change into sectoral planning and implementation at all levels Promote a climate resilient and low carbon economic development Mainstream climate change into sector functions |

32 percent by 2030 |

| Somalia |

Somalia National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) 2013 Environmental and Climate Change Policy 2012 First NDC 2021 |

Reduce change-induced vulnerabilities to the poorest communities who depend on natural resources Identify the key environmental challenges and opportunities |

30 percent by 2030 |

| South Sudan |

National Environment Policy 2015–2025 Updated NDC 202 |

To enhance the protection, conservation, and sustainable use of natural resources |

Sectoral actions/ reductions 110 MT reduction by 2030 with additional sequestered 45 million tCO2 e |

| Rwanda |

National Environment and Climate Change Policy 2019 Rwanda Green Growth and Climate Resilience: National strategy for climate change and low carbon development 2011 Updated NDC 2020 |

Achieve a clean and healthy environment, resilient to climate change for a high quality of life Promote climate resilience and green development through adaptation, mitigation, and poverty reduction |

38 percent by 2030 |

| Tanzania |

National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) 2012 Updated NDC 2021 |

Enhance technical, institutional, and individual capacity of citizens to address climate change impacts |

30–35 percent by 203 |

| Uganda |

Green Growth Development Strategy 2017–2030 National Climate change policy (NCCP) 2015 Updated NDC 2022 |

Achieve an inclusive low-carbon economic development that observes efficient and sustainable use of natural resources and human capital Attain transformation through climate change mitigation and adaptation |

25 percent by 2030 |

6.0. Carbon Trading in Ethiopia

Sub Saharan African policymakers are exploring a “green economy” to support agriculture dependent countries like Ethiopia through carbon trading schemes, compensating wealthy nations for carbon reduction projects, and proposing a $100 billion Green Climate Fund for change adaptation.

Despite contributing only 4% of global emissions, Africa’s 94% of adaptation and mitigation investments fund green economies, causing Ethiopia to be negatively impacted. Ethiopia can benefit from carbon emission trading, enabling higher-emission nations to maintain Kyoto Protocol limits by purchasing rights from Ethiopia, and promoting a green economy for climate change resilience since 2011. The UN’s REDD+ program is preparing eight million hectares of land in the Oromia Region, with regional offices in Tigray, Amhara, and Southern aiming to complete readiness proposals by June 2016. Human activity is causing climate change, causing global issues, with Ethiopia, with minimal action, at risk of severe environmental damage and economic reversal.

The Natural Regeneration project, situated in the Humbo Community, is Ethiopia’s first ever attempt at carbon trading. Since the Humbo project is World Vision’s first carbon initiative, much negotiation at the federal, state, local, and community levels has been necessary. The World Bank, the Ethiopian Environment Protection Agency, World Vision Australia, World Vision Ethiopia, local and regional governments, and the community all established partnerships (Rinaudo et al., 2008). As of June 2008, monies remitted from Australia totaled US$ 282,537. According to a recent report, the Humbo Community Based Forest Management Project’s carbon credits cost the World Bank (WB) $34,000 (Addis Fortune, 2010).

The project has conserved 2,728 hectares of degraded forest that were being continuously exploited for wood, charcoal, and fodder extraction; these areas are now being restored and maintained sustainably. This is one of its current accomplishments. Furthermore, the introduction of farmer managed natural resources proved successful in Ethiopia; for the first time, the country is experiencing the immense potential of natural forest regeneration (Rinaudo et al., 2008).

The World Bank’s Bio Carbon Fund funded a project to help local farmers in seven community cooperatives regenerate native plants on their property. The project repaired 2,728 hectares of soil and increased crop yields, serving as a template for farmer led initiatives in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad. The project has since been reregistered under Gold Standard, issuing 104,067 VERs, and highlights general problems in the CDM’s forest sector.

6.2.1. Carbon Trading Opportunity in Ethiopa

I/The Kyoto Protocol Adaptation Fund: Funding for adaptation initiatives in poor nations like Ethiopia, funded by a two percent share of CDM proceeds and additional financing streams, aims to prevent deforestation and land degradation. According to Behr et al. (2009) and FAO (2004), the Meeting of the Parties COP is expected to bring the Adaptation Fund into effect. The Prototype Carbon Fund (PCF), established by international organizations such as the World Bank, aims to discover the best practices for implementing greenhouse gas reduction programs. With a maximum budget of $180 million and an expiration date of 2012, the PCF has raised over $100 million from both public and private sources and invested it in a number of biomass and renewable energy projects. Per ton of CO2, PCF pays between $3 and $12 (Pronove, 2002). The World Bank is establishing the Bio Carbon Fund to finance initiatives aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, supporting sustainable development, and preserving biodiversity. Participants in the BCF are anticipated to contribute $2–3 million, with capitalization up to $100 million over the course of one or more closings. The BCF is anticipated to be operational by fall 2003, with a call for contributions to be issued in early 2003 (FAO, 2004). The voluntary carbon market is now the sole option for storing carbon and preventing deforestation. Bali’s approval of REDD has emphasized developing pilots or “Readiness” projects. Norway, the World Bank, and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility have committed funds for REDD activities.

Large businesses are voluntarily reducing greenhouse gas emissions, leading to the establishment of carbon credit markets. These markets, driven by industry associations and knowledge hubs like Climate Change Central and CDM Central, fund carbon offset initiatives in emerging nations.

II/Competitive advantage: Businesses can gain a competitive edge by reducing emissions and promoting environmental responsibility. Consumers and investors favor low carbon and sustainable businesses, enhancing their reputation and brand value. As Ethiopia’s economy diversifies, businesses can benefit from agreements to reduce carbon emissions. Responsible organizations can highlight their environmental responsibility to clients and consumers, gaining a competitive advantage.

III/Economic incentives for emission reductions: Carbon markets provide financial incentives to companies to reduce emissions, encouraging the use of eco-friendly technologies, renewable energy sources, ecosystem restoration, and investment information related to emissions, thereby promoting sustainable practices. Industries like cement, sugar, glass, and geothermal byproducts receive additional incentives for managing gas emissions, while electric engines are being used in transportation to reduce emissions.

The GEF is financing climate change related activities and programs, supporting developing countries like Ethiopia, which heavily rely on traditional biomass energy. (Such as OPEC countries). The UNFCCC was followed in the establishment of this fund. This fund has been the recipient of grants totaling about US$450 million each year since 2005 (S.P. Pfaff et al., 2004).

IV/Innovation and technology development: Innovation in renewable energy and sustainable technology is fueled by the need to reduce emissions. Businesses can take advantage of opportunities in low carbon technology development and deployment to effectively fulfill emission targets. Ethiopia therefore has the potential to produce energy from renewable sources such hydropower, wind, sun, and geothermal energy.

V/Flexibility and compliance options: Businesses have the freedom to meet their emission reduction goals thanks to the carbon market. If a business finds it challenging to cut emissions internally, it can expand its options for compliance by investing in carbon offsetting projects or buying allowances from other businesses.

VI/Access to funding: Taking part in carbon markets can make it easier to find finance options. Initiatives for sustainable development and emission reduction are financially supported by a large number of international organizations and investors.

VII/Available potential from host countries: Forestation and reforestation help nation’s access carbon markets, while deforestation reduces global forest loss. Land management changes, like RAI land, increase carbon stocks and plant biomass storage capacity. Exploring reforestation strategies for carbon finance or integrating it into management goals is possible. A feasibility study by BERSMP, an initiative of FARM-Africa and SOS Sahel, aims to determine the potential for carbon financing in the Bale Mountains. This analysis indicates that there is a great deal of potential for both a Reduced Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) component to be sold on the voluntary market and an acceptable Afforestation/Reforestation (AR) component under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) (Tsegaye Tadesse, 2008). The report indicates a REDD project in Bale Mountain Eco region, covering 600,000 acres, with 3,000 hectares for reforestation, 2,000 for Forest Agency, and 1,000 for community-based woodlot planting.

6.2.2. Carbon Trading Challenges in Ethiopia

The creation and sale of carbon credits presents challenges, some exclusive to forestry projects, while others apply to all initiatives seeking to raise funds through carbon markets. Carbon trading, involving activities affecting forests, is crucial for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. US initiatives like the KP and regional carbon markets have been established. (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Although forestry initiatives have raised questions and created controversy, they may nevertheless present significant market potential for carbon offsets. These are covered in the section below.

I/Complexity and administrative burden: Accurate emission measurement, reporting, and verification are necessary for participation in carbon markets. Producing this kind of fruit can be challenging and time consuming, particularly for small businesses with little funding.

II/Market volatility: Changes in regulations, political decisions, and market speculation are just a few of the variables that can cause price swings in the carbon market. The financial planning of carbon trading companies may be impacted by this uncertainty.

III/Risk over allocation or scarcity: Over allocation of carbon allowances can occur occasionally, leading to an excess of allowances and low market prices. Contrarily, a lack of subsidies may lead to exorbitant expenses, which would make compliance expensive for companies.

IV/Carbon leakage: Some companies, particularly those with high energy use, may be at risk of carbon leakage. If this happens, production may move to regions with less stringent emission regulations, which would increase global emissions. For managed forests, leakage defined as deliberate or inadvertent activities that may occur outside of the project boundaries and result in a net elevated emissions profile remains a genuine but manageable concern (Matt Smith, 2007). Leakage, as defined by Rinaudo et al. (2008), is the term used to describe emissions that occur outside the project’s boundaries as a consequence of the project. Farmers using pastured fields for cattle grazing may find alternative grazing locations in a forestry project, leading to additional forest clearing and emissions leakage, with a net decrease less than a credit exchange (Stephenson and Bosch, 2003).

V/Integrity and additionality of carbon offsets: The test of additionality assesses if an offset project would have proceeded without the forest carbon market, assuming financial and technical viability. (Rinaudo et al., 2008; Gorte and Ramseur, 2010; Moura Costa). The project’s offset integrity is significantly influenced by its ability to achieve additional emissions reductions compared to those that would have occurred without the project (Rinaudo et al., 2008; Gorte and Ramseur, 2010; Moura Costa). Of the CDM criteria, additionality is an important aspect, although putting the additionality criterion into practice can be difficult. Subjectivity may play a role in determining a project’s additionality, which could result in conflicting findings. Historical data on deforestation programs is often hazy, making it difficult to accurately predict the outcome of these initiatives. (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Carbon offset programs require verified emissions reductions, but rigorous monitoring and certification processes may challenge their legitimacy and integrity.

VI/Measurement: Carbon sequestration in forests can be difficult to measure. Different methods have been used to estimate carbon sequestration by different activities in different locations, including as tables, models, and protocols (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Estimators often rely on commercial timber volume, ignoring the potential linear correlation between volume and carbon sequestration, as seen in thinning, a forestry technique aiming to maximize volume. Field measurements are essential for calibrating estimated carbon storage to actual ground conditions, but they are costly and susceptible to sample error. (Sean Weaver, 2008; Gorte and Ramseur, 2010).

VII/Forward Crediting: Biological sequestration initiatives face a unique challenge due to the long time lag between project start and actual carbon sequestration, causing significant offsets over several years or decades (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Trees develop at varying rates and shapes throughout their lives, with species growth peaking at a significant age. Even old-growth forests can store carbon in their soils (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). The study explores the question of sequestration offset distribution, focusing on whether they should be distributed annually based on production or in a lump amount determined by future sequestration.

VII/Land tenure: Land tenure is a significant issue in the carbon market, as it is required for carbon credits approval. In Africa, property rights are a major concern. Madagascar’s natural forest restoration project aimed to address this issue. According to Doyle and Erdmann (2010), local communities in Indonesia that reside in or close to natural forests that are the focus of REDD programs are not legally entitled to the forests.

IX/Performance: Forestry projects face concerns about potential stoppage or reverse of sequestration, as they take decades to provide offsets, and human activity or natural events may neutralize emissions. (Sean Weaver, 2008; Patrick Doyle and Tom Erdmann, 2010; Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Forests composed of living organisms, face permanence issues due to their life cycle, which varies greatly depending on the tree type, with some species reaching over 1,000 years. However, trees eventually die, and the carbon they contain is either released into the environment, added to the soil, or processed into wood products (Gorte and Ramseur, 2010). Peak credit delivery for reforestation initiatives takes five years due to immature trees’ low carbon storage, and exante pre-sold credits may have lower value due to carbon market risks. (Doyle and Erdmann, 2010).

7.0. Key Finding On Private Sector Climate Financing and Green Growth

Ethiopia’s low adaptive ability, traditional agricultural practices, and resource extraction make it vulnerable to climate change, causing annual GDP loss of 11.4% since 1960.

Ethiopia is implementing climate action plans, including the Climate Resilient Green Economy, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote resilience through reforestation, renewable electricity production, and transportation networks.

Ethiopia’s National Determined Contributions estimate $316 billion in financing for 2021-2030, with a potential annual financial deficit of $33.1 billion if $1.45 billion in climate funding is received.

The Government of Ethiopia should increase climate funds and spend on climate smart technology, using creative financing and public capital to attract private investment and encourage tax breaks for green growth.

Ethiopia needs to invest in technologies and data management to fully utilize its natural capital, track stocks through natural capital accounting, adopt prudent fiscal measures, and enhance institutional reforms.

Ethiopia’s GDP from natural rents, mainly from forestry, decreased from 15.8% in 2010 to 5.1% in 2020 due to population pressure and decreased rent from minerals. The Green Legacy Initiative should be implemented for improved forest protection and sustainable management.

The Biocarbon Fund Initiative should be expanded to promote sustainable forest landscapes and increase carbon emissions reduction. Ethiopia’s natural capital, the Abay, Ogaden, and South Omo basins, holds potential for 10 trillion barrels of oil.

Ethiopia can secure green project funding through domestic changes like public private partnerships, capital markets, and bankable climate finance proposals, while development partners must support its natural resource capitalization.

Ethiopia must abandon agriculture, adopt carbon pricing, transition to renewable energy, and phase out coal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and maintain long-term human and environmental health.

The absence of rules and regulations in Ethiopia’s charcoal industry, despite its significant role in livelihood and energy, is concerning, as it operates in a policy and legal vacuum, making interaction costly and ineffective.

8.0. Conclusions

Ethiopia may offer opportunities for carbon trading, but there are also significant challenges that need to be addressed. To effectively participate in carbon trading and maximize its benefits, the government and pertinent stakeholders must work together to provide the necessary infrastructure, capacity, and legal frameworks. Ethiopia can resolve the challenges and competing interests associated with these developing markets while maximizing the benefits of carbon trading by implementing the recommended solutions.

9.0. Recommendation

The following suggestions are given in light of Ethiopia’s carbon trading opportunities and difficulties analysis:

Create a compressive carbon trading strategy: Ethiopia’s government needs to create a detailed, transparent carbon trading plan that highlights the nation’s advantages. Targets for mitigating climate change and Ethiopia’s development priorities should be in line with this approach.

Strengthen the legal and regulatory framework: In order to facilitate carbon trading activities, Ethiopia should put up a strong legal and regulatory framework. This includes creating rules and guidelines for carbon offset projects, emissions trading, and carbon pricing mechanisms. Private sector professionals and international organizations can offer technical support and direction in this process.

Invest in the construction of infrastructure: Ethiopia must create the required infrastructure, such as an emissions measurement, reporting, and verification system, in order to take part in carbon trading. Investigate creative funding sources give climate adaption top priority. Start efforts to raise public awareness and engagement. Look for global collaborations.

Ethiopia can handle the issues related to these developing markets and optimize the advantages of carbon trading by putting the aforementioned strategies into practice.

Abbreviation

| CDM |

Clean development mechanisms |

| CER |

Certified emission reduction |

| GDP |

Growth Domestic Product |

| Mt CO2e |

Metric ton of carbon dioxide emission |

| RAI |

Rainfall anomaly index |

| REDD |

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation |

References

- Agency, E. N. (2023). Ethiopian New Agency. Retrieved from HTTPS://www.ena.et.

- AUKLAND LPM,costa,bass,Hug.N,Landell mill R.Tipper and R.Carr. (2019, JAN 1). laying the foundations for clean development:preparing the land use section A quick guide of clean development mechanisms. Abebe Cheffo, 31.

- Behr.T,Martin,Witte,Wache,Hoxell and James Manzer. (2009). toward a global market potential and limitS of carbon market integration energy policy paper series. 509.

- Doyle,P and Erdmann T. (2010). Using carbon markets to fund forestry project:Challenges and solutions.DAIdeas innovations in action volume 6.,No.3.

- FAO. (2022). ,land use change and forestry or agriculture indicators from FAOSTAT emission,Database[online]. Retrieved from FAOSTAT: https:///www.fao.org/faostat/.

- FAO. (2004). A review of carbon sequestration project. FAO. Rome,Italy.

- FAO. (2004). Carbon sequestration in dry land,soils.world soil resources reports,102. Rome,Italy.

- Fortune, A. (2010, October 21). frist ever carbon credit trade. Addis Ababa, Oromia, Ethiopia.

- h, E. (2014). carbon market crisis and the future of carbon market dependent climate changes finance. Ervin h, 723-747.

- initiatives, c. p. (2015). <Global landscape of climate finance=. www.climate policy initiative.org.

- S.P.Pfaff,S,Suzi Kerr leslie Lipper,Romina Cavatassi,Benjamin Davis,Joanna Hendry and Arturo Sanchez. (2004). tropical forests carbon benefits the poor? evidence from Costa Rice. ESA, 04-10.

- Stephenson K. and Bosch D. (July,2003). Nonpoint sources and carbon sequentration credits trading: what can the twio learn from each other? paper prepared for American agricultral association. American Agricultural Economics Associations Annual Meeting, (pp. 27-30). Montreal,Canada.

- T.etal, R. (2008). Carbon trading community Forestry and development responces to povert.,53,.

- UNEP. (2016). Emission gap report,avialable. new york: www.unep.org/puplication ebook/emission gap report/.

- USAID. (2015). Green house Emission in Ethiopia. USAID,from people of America, p-2.

- W., G. R. (2010). Forest carbon market:potentials and drawbacks. Congressional research service report congress,prepared for members and comittee.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).