1. Introduction

There is an urgent need to reduce global carbon emissions in response to the increasing threat of climate change, which poses significant risks to ecosystems, economies, and public health worldwide. The transition to renewable energy is critical in this pursuit, with numerous sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels offering the potential to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. However, the prioritisation of carbon emissions reduction targets when implementing renewables has led to ‘carbon tunnel vision’ [

1], where the impacts of the renewable energy transition on broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) beyond Climate Action (SDG 13) and Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7) are generally overlooked.

In an attempt to overcome this carbon tunnel vision, several studies have investigated the links between energy production and the SDGs. Fuso Nerini et al. (2018) provided a high-level assessment exploring the synergies and trade-offs between SDG 7 (Clean Energy) and other SDG targets [

2]. Their work underscored the critical role energy system decisions play in achieving the UN 2030 Agenda [

3,

4]. Bisaga et al. (2021) built on that study to conduct a more targeted analysis by focusing on a particular energy type, in this case, off-grid solar. They further highlighted the need to develop context-specific rapid assessments to effectively evaluate the impact of a given renewable energy type on the SDGs [

5]. Tian et al. (2024) provided a further increase in the resolution of the relationship between renewables and the SDGs by considering seven aspects of the renewable energy production process, including source selection, operational requirements, the conversion process, waste production, reuse, transmission and distribution, and storage. This was done for six different renewable energy types, including biomass, hydropower, solar, geothermal, wind, and ocean energy (wave and tidal). This approach enables the assessment of the impact that a renewable energy project can have on the SDGs at a finer level of detail, helping to identify connections and dependencies that might be overlooked due to carbon tunnel vision [

6] .

To allow the links between renewable energy projects and the SDGs to be understood in a consistent, transparent, and user-friendly manner [

7], various frameworks and tools, have been developed and demonstrated. Examples include:

Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) tools to assist communities in ranking alternative local renewable energy sources (RESs) during the pre-feasibility stage by considering factors such as the ability of RESs to enhance energy security [

8];

A framework and Excel-based tool (the SDG-IAE framework) designed to help practitioners understand the interactions between energy projects and the SDGs and to inform conversations among stakeholders [

9]; and

The Energy Scenario Evaluation (ESE) framework for assessing the sustainability and public acceptability of energy transition scenarios, which includes a questionnaire consisting of five critical questions [

10].

However, the focus of previous studies has been solely on identifying links between RESs and the SDGs, not on determining which specific aspects of renewable energy projects contribute to these goals and/or what the most effective ways of improving the sustainability of renewable energy projects are. Even though these approaches raise awareness of potential problems, they do not help to diagnose any underlying causes that enable more sustainable renewable energy projects to be developed. Consequently, the overall aim of this study is to overcome this shortcoming by:

Developing an approach for identifying the project-level decisions made during the development of renewable energy projects that have an influence on the SDGs.

Developing an approach and tool for identifying the relationships between the project-level decisions identified in Objective 1 and the SDGs for specific renewable energy projects in a consistent, transparent and user-friendly fashion.

Illustrating the application and benefits of the approach developed in Objective 1 and the tool developed in Objective 2 by applying it to three case studies that are based on proposed renewable energy projects in Australia, each with different attributes (e.g., type of renewable technology, location, local demand, and other contextual factors).

The structure of the remainder of this paper is as follows.

Section 2 provides details of (i) the proposed approach for identifying the project-level decisions made during the development of renewable energy projects that have an influence on the SDGs and (ii) the approach and tool for identifying the relationships between project-level decisions identified and the SDGs for specific renewable energy projects in a consistent, transparent and user-friendly fashion. Then,

Section 3 introduces three case studies detailing the relationships between project-level decisions and the SDGs, with the results of the case study analyses given in

Section 4. A summary of the overall utility of the proposed approach and tool and conclusions are given in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

Details of the approach for identifying the project-level decisions (i.e. decisions that have to be made during the development of renewable energy projects that have an influence on the SDGs) are given in

Section 2.1. Then,

Section 2.2 details the approach and tool for identifying the relationships between the project-level decisions (developed in

Section 2.1) and the SDGs for specific renewable energy projects in a consistent, transparent and user-friendly fashion.

2.1. Identification of Relevant Project-Level Decisions

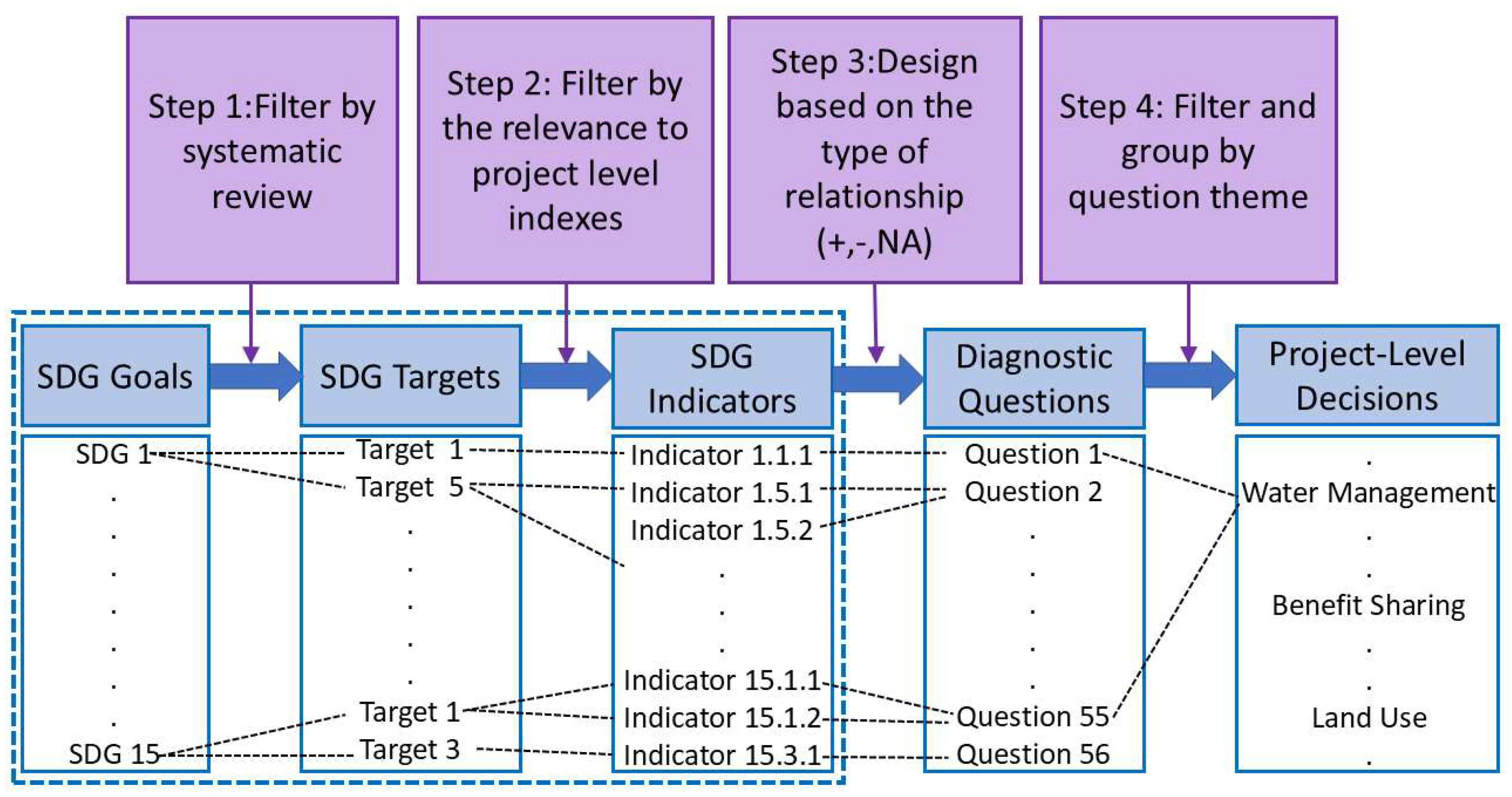

A summary of the proposed approach for identifying the project-level decisions made during the development of renewable energy projects that have an influence on the SDGs is given in

Figure 1. The approach consists of four main steps, which progressively identify and link the SDG Goals to the SDG Targets (Step 1), the SDG Targets to the SDG Indicators (Step 2), the SDG Indicators to a set of Diagnostic Questions (Step 3) and finally the set of Diagnostic Questions to Project-Level Decisions made during the development of renewable energy projects (Step 4). Details of each of these steps are given below.

As part of Step 1, the SDG Targets related to each of the SDG Goals relevant to different types of renewable energy projects (i.e., biomass, hydropower, solar, geothermal, wind, wave and tidal) were identified. Recognising the diverse impacts renewable energy projects can have on different SDG targets, we adopted the framing from Tian et al. (2024) [

6], which maps how seven key aspects of these projects (including source selection, operational requirements, the conversion process, waste production, reuse, transmission and distribution, and storage) enable or inhibit specific SDG targets. This provides a high-level overview of potential linkages between the SDGs and major renewable energy types, leading to the identification of a subset of impacted SDG targets. The detailed table and reference list supporting this high-level overview are provided in

Appendix A.

As part of Step 2, the SDG Indicators related to each of the SDG Targets determined in Step 1 were identified. A full set of indicators for all SDG targets is available from the SDG indicator framework [

11]. Many SDG indicators operate at regional or national scales, limiting their direct applicability to individual local scale projects. To address this, we systematically identified keywords within the SDG indicators that relate to the preselected targets impacted by projects. Examples of such keywords include 'sustainable agriculture', 'hazardous waste', and 'water-use efficiency'. We filtered out indicators applicable only at broader scales (e.g., national GDP). This filtering process refined broad associations into specific impacts relevant to individual projects, which assisted with establishing a direct link between project activities and the SDG targets they affect. The full list of SDG indicators identified through this process is summarised in

Appendix B.

In Step 3, a questionnaire was developed based on careful logic such that the answer to each question determines whether the associated project-level decision has a positive (enabling), negative (inhibiting) or neutral (neither enabling nor inhibiting, but can be improved or managed) impact on each of the SDG indicators identified in Step 2. This provides a repeatable way to identify which SDG indicators are relevant to a particular renewable energy project. The questions were formulated so that they only require binary “yes” or “no” responses and were aligned with established organisational reporting standards, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [

12,

13] and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) [

14], to ensure that the approach is robust and widely applicable. Great care was taken to streamline the questionnaire and minimise the number of questions required to address all of the relevant SDG indicators identified in Step 2. We achieved this by consolidating similar questions and eliminating redundancies. This resulted in a comprehensive set of 63 Diagnostic Questions, including some specifically tailored to reflect the unique characteristics of different types of renewable energy sources. This allows for a systematic evaluation of how specific projects may influence SDG targets at the project-level. These questions, along with the SDG indicators they address, and the mapping of the relationship between Diagnostic Questions and SDGs are provided in

Appendix B and

Appendix C.

In Step 4, the 63 Diagnostic Questions developed in Step 3 were grouped into coherent themes to make it easier to understand the relationships between the different types of factors that have to be considered during the development of renewable energy projects and their impact on the SDGs, thereby elucidating the types of decisions that are likely to result in the biggest increases in sustainability. These themes were adapted from common themes in ex-ante assessment frameworks [

10,

15,

16], which organise questions into relevant impact categories to anticipate potential outcomes. Specifically, we incorporated information from existing assessment frameworks from Australia, such as the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) [

17], and the Large-Scale Solar Energy Guidelines [

18,

19], to define the terminology for each Project-Level Decision Theme, ensuring ease of understanding and consistency with established contexts and practices. This resulted in the identification of the following 14 Project-Level Decision Themes, with details of which 63 questions belong to each of these themes given in

Appendix D:

Emissions Management

- 4.

Material Use and Efficiency

- 5.

Water Management

- 6.

Waste Management and Circular Design

- 7.

Climate and Disaster Management

- 8.

Benefit Sharing

- 9.

Biodiversity

- 10.

Land Use

- 11.

Heritage Protection (Natural and Historical)

- 12.

Heritage Protection (Indigenous)

- 13.

Community Engagement

- 14.

Energy Access and Local Use

- 15.

Hazard Mitigation and Health

- 16.

Storage Management

Although the process for identifying the types of decisions that have an impact on each of the SDGs is presented in the context of renewable energy projects in this paper, it is sufficiently generic to be applied to other decision contexts, such as sustainable tourism [

20] and business strategy development [

21]. Applying the methodology to other contexts would require the selection of context-specific SDG targets and indicators, as well as the development of context-specific assessment questions. This flexibility underscores the potential of our methodology to contribute to sustainable development initiatives in diverse fields.

2.2. Identification of Relationship between SDGs and Project-Level Decision Themes

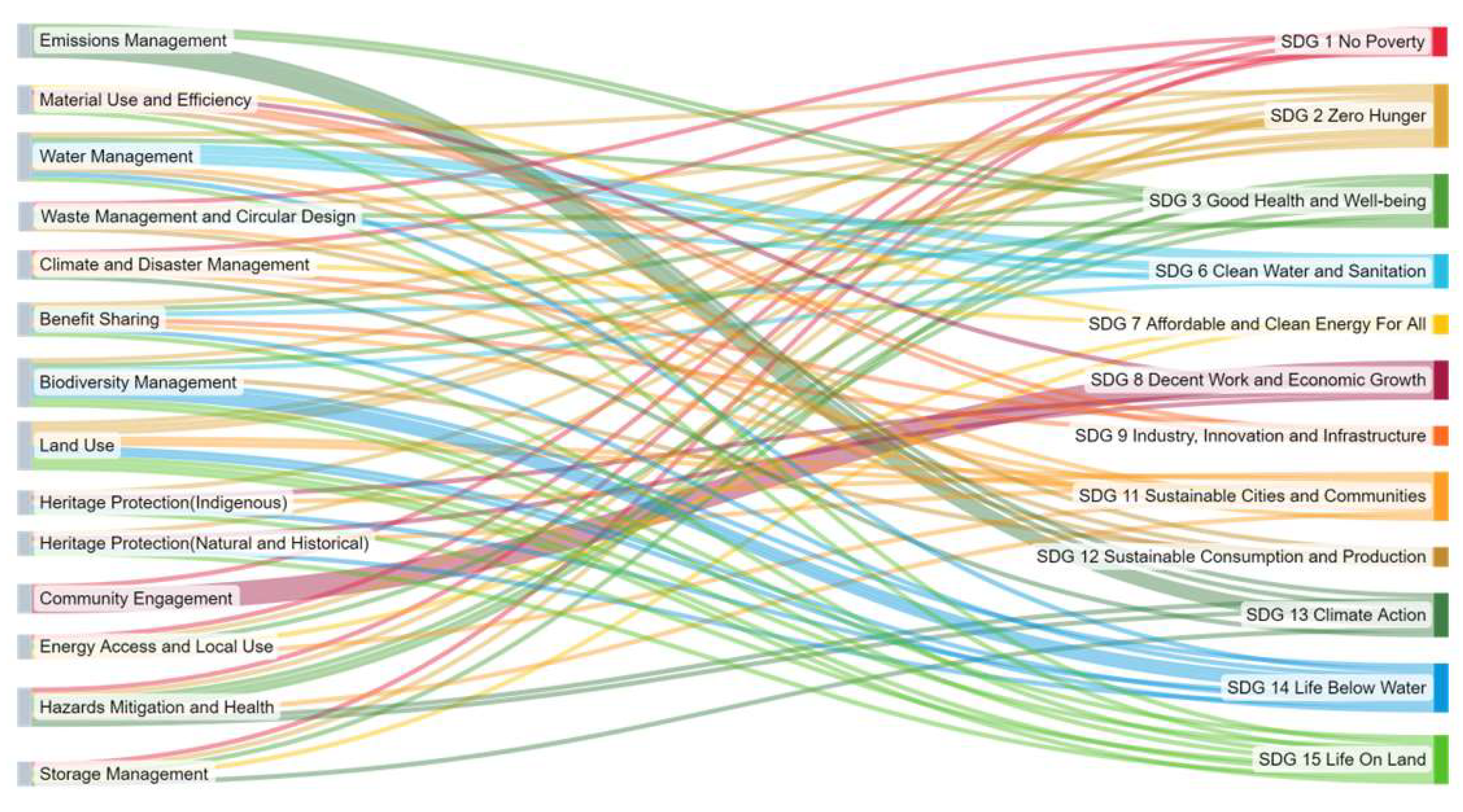

A summary of the relationship between the 14 Project-Level Decision Themes identified in

Section 2.1 and the SDGs is shown in

Figure 2. These relationships are manifest via the 63 Diagnostic Questions we developed (

Appendix D) and are colour-coded by SDG. The thematic grouping of the Diagnostic Questions facilitates easier analysis of the types of decisions that have a positive, negative or neutral impact on each of the SDGs by allowing stakeholders to focus on specific areas of interest. It also enables the broader sustainability impacts of relevant project-level decisions to be systematically considered during the project development process.

The lines in

Figure 2 represent all

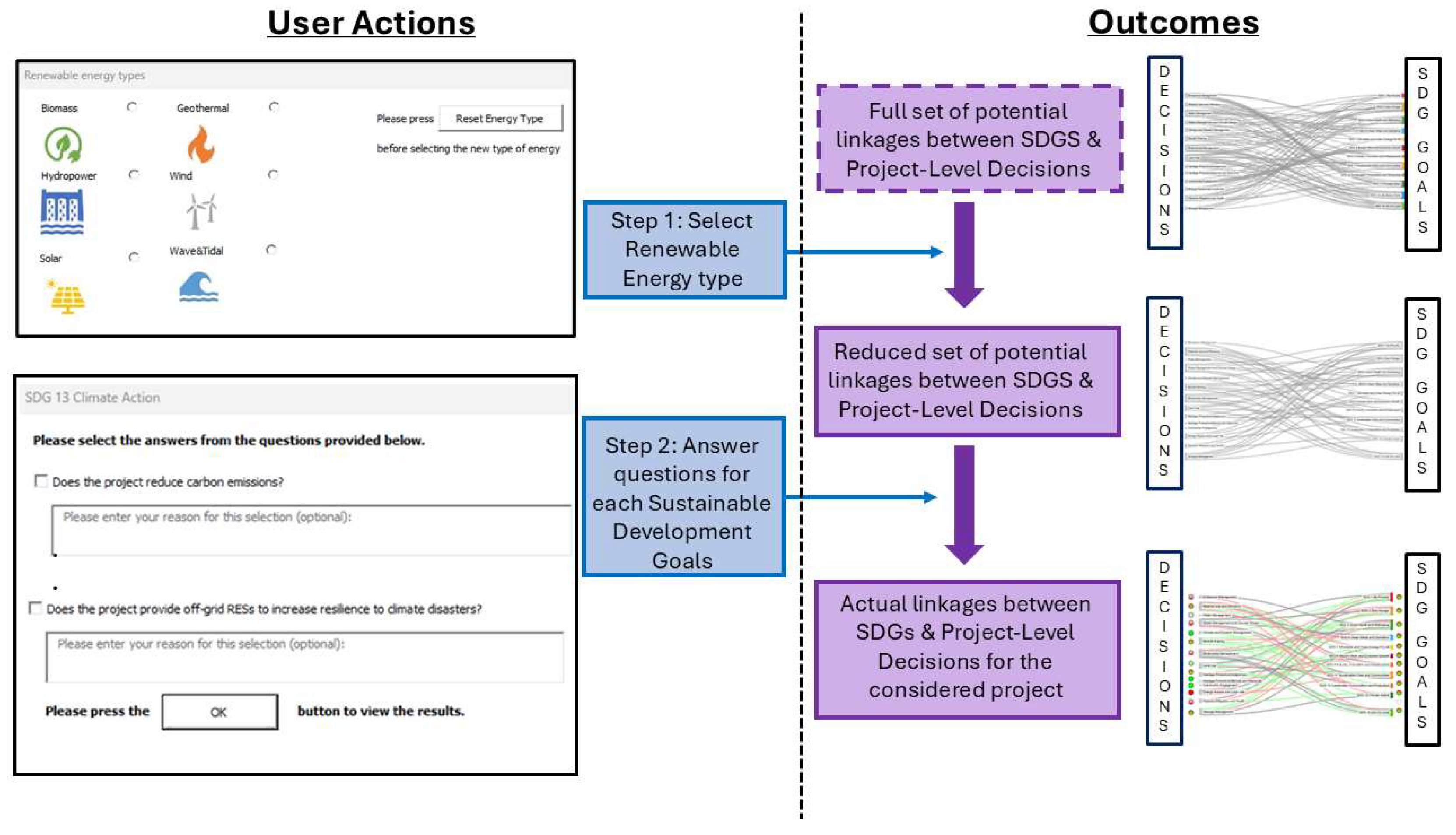

potential relationships between the 14 Project-Level Decision Themes and the SDGs. Whether these relationships are positive (i.e., enabling), negative (i.e., inhibiting) or neutral (i.e., no effect) is project specific and is determined by the responses to the 63 Diagnostic Questions for a particular renewable energy project. The approach for performing such assessments is summarised in

Figure 3, including how to implement the approach in an MS Excel tool that has been developed for this purpose. This tool is freely available on GitHub [link] and facilitates the practical application of the proposed approach in a transparent, consistent and easy-to-use fashion (see

Appendix E for further details on the MS Excel Tool).

The proposed approach consists of two steps, as indicated by the blue flowchart on the left-hand side of

Figure 3, labelled “User Action”, which also shows screenshots of how these two steps are implemented in the MS Excel Tool. The “Outcomes” of each of these “User Actions”, in terms of the transformations they achieve, are shown in the purple flowchart and illustrative figures on the right-hand side of

Figure 3, labelled “Outcomes”.

Step 1 (

Figure 3) requires users to select the renewable energy type for the project under consideration by clicking on the appropriate radio button. The reason for this is that, as identified by Tian et al. (2024) [

6], not all renewable energy types have the same impact on SDG targets. Consequently, not all of the 63 questions are applicable to all types of renewables and by selecting the type of renewable, the number of questions is tailored. For example, many onshore energy projects do not have an impact on SDG 14 (Life Below Water), which means that in these situations, the associated links are removed. A reduction in the number of Diagnostic Questions also results in a reduction in the potential number of linkages between Project-Level Decision Themes and the SDGs compared with those shown in

Figure 2 (which is represented by the top Sankey diagram in

Figure 3), as shown in the middle Sankey Diagram in

Figure 3.

Step 2 requires users to provide “yes/no” answers to the tailored Diagnostic Questions after the selection of the renewable energy type in Step 1. As can be seen from the screenshot from the MS Excel Tool in

Figure 3, this is achieved via tick boxes, with a tick indicating a “yes” response and the lack of a tick indicating a “no” response. However, users also have the option to provide brief details on the responses provided (e.g., the rationale for the selected response, the type of action currently being undertaken, etc.). As a result of this user input, the tool identifies which of the set of potential linkages between the Project-Level Decision Themes and the relevant SDGs (based on the renewable energy type selected in Step 1) are positive (i.e., which project-level decisions have a positive impact on each SDG), negative (i.e., which project-level decisions have a negative impact on each SDG), or neutral (i.e., which project-level decisions have no impact on each SDG), with the full mapping of project-level decision impacts on SDGs provided in

Appendix D. As can be seen by the bottom Sankey diagram in

Figure 3, this is indicated by green (positive), red (negative) or grey (neutral) connections between Project-Level Decision Themes and the SDGs.

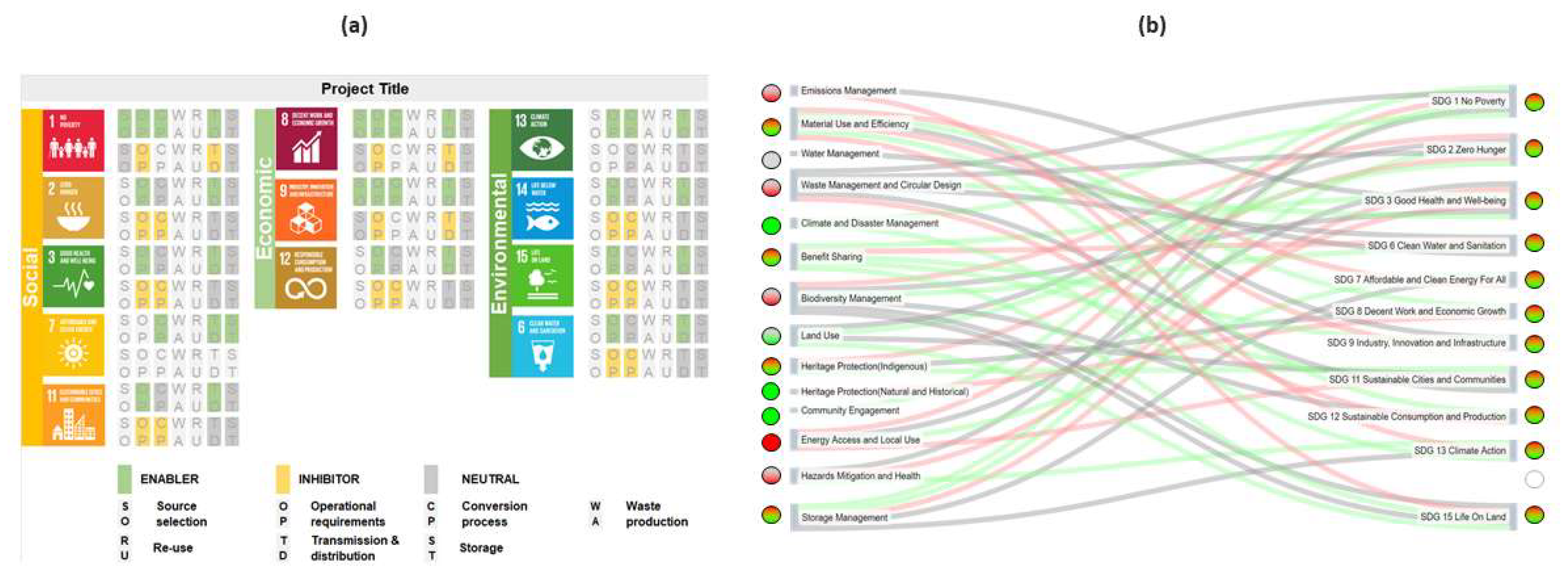

With the linkages identified as either positive, negative or neutral, the MS Excel tool produces two summary output plots that can be used for:

High-level sustainability assessments (Figure 4a): This consists of a plot indicating whether the renewable energy project under consideration has a positive (enabler - green), negative (inhibitor - yellow) or neutral (grey) impact on relevant SDGs for the seven aforementioned aspects of renewable energy production projects identified by Tian et al. (2024) (i.e., source selection, operational requirements, conversion process, waster production, re-use, transmission and distribution, storage). This provides a high-level assessment of the sustainability impacts of projects under consideration, which are likely to be different for different projects due to differences in their specific contexts (e.g., type of renewable energy source, location, etc.). Information on enabling impacts can be used to support the development of business cases and inhibiting impacts to identify areas that require attention.

Identification of project actions most suited to increasing sustainability (Figure 4b): This consists of a Sankey diagram showing whether the project-level decisions have an enabling, inhibiting or neutral impact on each of the SDGs, as shown by green, red and grey connecting lines, respectively, in the sub-figure. This provides an indication of which project-level decision(s) require attention to ensure proposed renewable energy projects are sustainable. The “traffic light” indicators on the right-hand side of the sub-figure summarise the impact on a particular SDG due to project-level decisions based on the survey responses provided (i.e., a complete green traffic light indicates that all impacts on this SDG are enabling, a completely red traffic light indicates that all impacts on this SDG are inhibiting, a completely grey traffic light indicates that there is no impact on this SDG and a traffic light with a mixture of colours indicates at least one type of impact for each colour shown). The traffic light indicators on the left-hand side of the figure summarise the contribution of a particular Project-Level Decision Theme to the overall impact of the proposed renewable energy project on a particular SDG based on the survey responses provided (i.e., a completely green traffic light indicates that all project-level decisions belonging to this theme only have enabling impacts on affected SDGs, a completely red traffic light indicates that all project-level decisions belonging to this theme only have inhibiting impacts on affected SDGs, a completely grey traffic light indicates that all project-level decisions belonging to this theme do not have any impacts on the SDGs and a traffic light with more than one colour indicates that project-level decisions belonging to this theme have at least one type of impact for each colour shown).

It should be noted that the plots in

Figure 4 can also be used for effective stakeholder communication.

3. Case Studies

To highlight the need for a consistent, transparent, and accessible assessment of the sustainability impacts of renewable energy projects, as well as the ability to link potential improvements in sustainability to project-level decisions, we apply the proposed approach and tool to three case studies. A summary of these case studies is given in

Figure 5. As can be seen, the case studies are in different locations in Australia (New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria) and consider different renewable energy sources (biogas, solar, offshore wind). This significant diversity in the case studies was selected to illustrate how geographical information, project architecture, inherent technological characteristics, and natural environmental factors affect project-level decisions related to the SDGs.

The first illustrative case study is based on a project in South Australia focused on biogas production from a wastewater treatment plant, where producing this type of renewable energy is highly feasible for integration into the existing energy supply chain. However, there are concerns regarding job displacement due to the new technology involved, unintentional emission leakage during conversion processes and from distribution pipelines [

23], and chemical contamination of surrounding water bodies, which may have harmful impacts on protected marine areas [

24,

25].

The second illustrative case study is based on a large-scale solar project in New South Wales that has sparked controversy on social media [

26,

27]. The controversies stem from high construction costs, land disputes with the local community, construction delays, and multiple lawsuits involving stakeholders [

28]. Moreover, it has been closely examined for its significant impact on biodiversity [

29] and concerns regarding substantial ongoing water consumption [

30]. Nonetheless, the amount of low-carbon energy supplied by this project has generated 529GWh of electricity that supplies 50,000 households [

31], and therefore represents a particularly useful case study for exploring ‘carbon tunnel vision’.

The third illustrative case study is based on a proposed offshore wind farm in Victoria. Growth in offshore wind has recently emerged as a new trend in Australia's green energy sector. However, potential concerns about this particular project have been raised in relation to significant job displacement in the fishing and shipping industries, as well as the need for large infrastructure to transmit and convert electricity [

24]. Additionally, the potential impacts on marine and wildlife-protected areas are also uncertain and contentious [

32].

As part of the demonstration of the application of the MS Excel tool to the three illustrative case studies, the relevant type of renewable energy source was selected in Step 1 of the proposed process using the developed MS Excel Tool (see

Figure 3) and then the corresponding Diagnostic Questions were answered by the authors in Step 2 using publicly available information for Case Study 1 [

33], Case Study 2 [

34] and Case Study 3 [

35], where reasonable assumptions were made in the absence of information. Details of the main differences in the information used to answer the Diagnostic Questions are given below, with a full set of responses to all Diagnostic Questions for each case study given in

Appendix F, Appendix G and Appendix H, respectively.

Energy Type:

Stored energy versus kinetic energy. These energy types have different geographical impacts during source selection, distinct land impacts during the conversion processes, and varying requirements for overcoming intermittency in storage and distribution [

36]. Case Study 1 involves stored energy (the storage of wastewater), while Case Studies 2 and 3 involve kinetic energy (i.e., capturing readily available solar and wind energy).

Region:

Urban versus rural versus marine environments. The location of RESs plays a decisive role in local energy utilisation, influences the development status of existing infrastructure, and affects local populations differently [

37]. Case Study 1 is located in an urban area, Case Study 2 is in a rural area, and Case Study 3 is in a marine area.

Storage Type:

Different storage methods, such as batteries. According to Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) assessments, when the capacity of battery storage exceeds certain thresholds, which vary by country, there are potential health and hazard impacts that need to be addressed [

38]. For example, according to the Australian Standards [

18], if a project includes battery energy storage with a capacity of more than 30 MW, the developer must undertake a preliminary hazard analysis. To investigate such potential impacts, it is assumed Case studies 1 and 2 do not have storage onsite, whereas Case Study 3 has a battery Energy Storage System (BESS).

National Native Title:

Recognition of Indigenous land rights. Surveys conducted by the Australian Ministry of Energy (AMOE) indicate that many RESs in Australia are being built on traditional lands [

39]. Recognising First Nations' titles and protecting the land-use rights of Indigenous peoples should therefore be included in the development process of RESs. Also, engaging with local communities can boost the process of achieving public backing or certification, known as a "social license to operate" (SLO) [

40]. For Case Studies 1 and 3, the projects are not located on traditional land. For Case Study 2, the project is constructed on the land of First Nations’ people and there is a high possibility that the people living in this land may face relocation due to the construction of the project [

41].

Existing Network connection:

Infrastructure and material footprint. The existing network connections are a critical factor influencing the material footprint during the construction of RESs. For example, offshore wind farms face substantial upfront costs and are criticised for lacking integration, necessitating additional supporting infrastructure to connect and transmit energy to the national grid [

42]. For Case Studies 1 and 2, both projects are connected to the existing energy grid. However, for Case Study 3, a new connection to the grid needs to be built.

Regional demand correlation:

Local energy demand. According to classifications adapted from [

39], a higher degree of regional demand correlation indicates a greater need for local clean energy supply. As previously mentioned, the location of RES plants directly influences regional energy needs, affecting the share of green electricity supplied to the area. For Case Study 1, as the plant is located in an urban area within close proximity of the existing grid, the local demand for green electricity is medium. For Case Study 2, the plant is located in a rural area and the correlation with demand for local energy is considered high. For Case Study 3, as the location is offshore and the main purpose of green energy generation is to support and supply the national grid, there is negligible correlation between local demand and use for this type of renewable energy, hence it is classified as low.

4. Results and Discussion

To demonstrate the differences in the high-level impact on sustainability of the three illustrative renewable energy case studies considered,

Section 4.1 presents a sustainability impact assessment using the tool output (see

Figure 4a). Then, to show the benefits of linking SDG impacts to project-level decisions,

Section 4.2 contains a comparison of the project-level decisions and whether they resulted in a positive, negative or neutral impact (see

Figure 4b). It should be noted that the case study results do not represent sustainability assessments of the three actual renewable energy projects on which the case studies are based. They are simply intended to illustrate the usefulness of the sustainability assessment framework and tool introduced in this paper, rather than provide commentary on the proposed projects themselves.

4.1. Impact of Renewable Energy Projects on SDGs

Figure 6 shows the high-level impact on sustainability for each of the three illustrative case studies considered, with green cells indicating a positive impact, yellow cells indicating a negative impact, and grey cells indicating that there was no impact. The impacts on each SDG are also separated across the seven aforementioned aspects of renewable energy projects introduced by Tian et al. (2024) [

6]. As can be seen, across the three case studies, there is a large difference in the impacts on sustainability, due in part to the differences in the type of energy system, but also the specific choices made for each project, highlighting the need for project-specific assessments and standardised, easy-to-use tools for performing such assessments.

Among the case studies, Case Study 3 has the highest number of positive impacts on overall SDG targets, while Case Study 2 has the most negative impacts. Note that these findings do not comment directly on the magnitude of the impacts, just the number of connections identified based on the survey responses.

Considering social SDG targets, Case Study 1 has the highest number of positive impacts, as the project significantly contributes to the energy-food nexus and could further enhance sustainable agriculture. Conversely, both Case Studies 2 and 3 have negative impacts on food-producing area; however, Case Study 2 further negatively affects native vegetation due to construction-related clearing, raising concerns about habitat disruption and wildlife protection.

Considering economic SDG targets, Case Study 3 has the highest number of positive impacts, as this project plays a critical role in boosting the local economy and providing more job opportunities. In contrast, Case Studies 1 and 2 negatively impact the job market, with Case Study 2 also demonstrating inefficiency in material use (see

Appendix F and Appendix G).

Considering environmental SDG targets, Case Studies 1 and 3 both have a similar number of positive impacts, such as reducing carbon emissions and protecting biodiversity, although Case Study 1 could improve efforts in nearby marine wildlife protection areas. The downsides for Case Study 2 include interconnected social and environmental impacts from land occupation and substantial water usage across multiple stages of the renewable energy generation process.

While the above results are for three illustrative case studies, they demonstrate that the sustainability assessment of renewable energy projects is complex and can be affected by many different factors, highlighting the need to perform such assessments on a case-by-case basis. In addition, they demonstrate the value of the proposed approach and tool, as they enable the detailed high-level sustainability assessment of renewable energy projects to be performed relatively easily by answering “yes” or “no” to 63 (or fewer) carefully designed Diagnostic Questions based on the best available information, as evidenced by the desktop study of publicly available documents we used to perform our assessments. However, although these results indicate which SDGs are affected and at which points in a project's supply chain, they do not suggest how sustainability can be improved or altered, highlighting the need to also connect these types of assessments with project-level decisions.

4.2. Impact of Renewable Energy Project on SDG

Figure 7 illustrates significant differences in the positive, negative and neutral connections between Project-Level Decision Themes and the SDGs across the three case studies considered, which is attributable to both the type of renewable energy and the specific project configurations, as reflected in the survey responses (

Appendix E to

Appendix G). This underscores the need for a context-specific, easy-to-use method and tool to identify the underlying causes of these differences. In addition, the results for the three case studies demonstrate some of the potential key findings the proposed approach can provide for a renewable energy project assessment, as discussed below.

In Case Study 1, the “Storage Management” project-level decision appears to be potentially underutilised because it has no positive impact on the SDGs, as indicated by its fully grey traffic light. The existence of multiple neutral connections highlights the potential role that pre-implementation storage plans could play in enhancing multiple SDGs, such as SDG 1 (No Poverty), since local storage can improve the reliability of energy access by supporting economic activities, and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), as local storage can overcome the intermittency of energy supply. Therefore, implementing effective storage management can serve as a strong enabler of sustainable development when planned and executed properly for this particular case study. Insight into which project-level decisions have already fulfilled sustainability objectives can also be gained by examining the traffic lights associated with the SDGs. For example, both SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) received a fully green traffic light. This indicates that the combined effect of multiple project-level decisions—such as biodiversity management, benefit sharing, and heritage protection—was well-coordinated, highlighting areas of strong achievement.

In Case Study 2, multiple project-level decisions have resulted in several SDGs being marked as half green and half red on the right-hand side of

Figure 7, indicating a mix of enabling and inhibiting impacts within the same categories. Poor performance in areas such as water management, waste management and circular design, climate and disaster management, and biodiversity management has led to these mixed outcomes. This demonstrates that when considering the project's sustainability as a whole, it is crucial to make correct decisions across multiple domains rather than selectively focusing on certain goals. Additionally, the interconnection of these decisions highlights the necessity for different stakeholders to work collaboratively, ensuring that efforts in one area support progress in others. Notably, SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) is significantly impacted in Case Study 2, as indicated by the larger number of red connections from the project-level decisions to this SDG in

Figure 7. This corresponds to the fact that land occupancy is one of the most controversial issues associated with this case study [

26]. Multiple project-level decisions can aid in better handling this issue, including improvements in water management, land use planning, and heritage protection (both Indigenous and natural/historical). Additionally, SDG 14 (Life Below Water) does not apply to this case study, as there are no decisions related to marine protection or wildlife.

In Case Study 3, SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) is fully grey, with project-level decisions related to water management, waste management and circular design, and biodiversity management all having no impact on that goal. This highlights that additional actions in water and biodiversity management could result in a positive impact on SDG 6. Additionally, there are opportunities to increase the sustainability of the project by adopting improved climate and disaster management practices, which would have a positive impact on SDG 13 (Climate Action). This SDG could also be enhanced by connecting the project to off-grid infrastructure to aid surrounding communities, which is currently not the case as it is directly connected to the national grid.

The above results provide an indication of the complexity of the relationships between project-level decisions and the SDGs and how these can be significantly different depending on specific local project conditions and circumstances. This highlights the need for a project-specific approach and tool that can be applied easily and consistently to different projects, such as the one proposed in this paper. The results also highlight the value in linking project-level decisions with each of the SDGs, both in terms of the insights gained in relation to which decisions contribute to different SDGs in a positive, negative or neutral manner and, more importantly, the identification of actions that can be undertaken to improve the sustainability of renewable energy projects, thereby assisting with overcoming carbon tunnel vision.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This paper presents a novel approach to evaluating the sustainability of renewable energy projects and to identifying which project-level decisions influence the SDGs, as well as a user-friendly MS Excel tool for implementing this approach in a consistent and easy-to-use fashion. A key attribute of the approach is that it is deliberately parsimonious, enabling the relationship between project-level decisions and relevant SDGs to be determined by answering fewer than 63 diagnostic “yes/no” questions. This makes the approach transparent and easy to implement in practice, while providing a detailed high-level sustainability assessment and identifying the linkages between project-level decisions and specific SDGs. This enables project developers and relevant stakeholders to better understand and mitigate their projects’ positive, negative, and neutral impacts on the SDGs during the planning or feasibility study stages of a project, and hence which actions can be taken to increase the broader sustainability of renewable energy projects, beyond the goal of reducing carbon emissions, thereby overcoming carbon tunnel vision.

The application and value of the approach and tool were demonstrated on three illustrative case studies located in different geographical regions of Australia that use different types of renewable energy sources. While based on real projects, the case studies were constructed to provide varied contextual factors for the sake of demonstrating the proposed approach and tool, rather than providing sustainability assessments of the actual projects on which the case studies are based. This was achieved by using publicly available information to answer the diagnostic “yes/no” questions. The results of the sustainability assessments show that the different case studies impact the SDGs differently and that different project-level decisions emerge as most influential depending on specific project context. This highlights the need to perform such assessments on a project-by-project basis, as well as the value of the proposed approach and tool.

As the MS Excel tool for implementing the proposed approach is easy to use and produces outputs that relate a range of project-level decisions to all SDGs, it facilitates dialogue among various stakeholders, enabling them to share their perspectives and decisions on specific projects. Providing a common platform helps stakeholders make more informed decisions to achieve increasingly green "traffic lights" for all SDGs. The fact that the tool is developed in MS Excel and freely available on GitHub means that it is easily accessible and that practitioners can contribute feedback and submit suggestions for future updates and enhancements.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. GitHub, Tool S1: Diagnostic Tool for Assessing and Increasing the Sustainability of Renewable Energy Projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, JT, SAC, HRM, ACZ, JH; methodology, JT, SAC, HRM, ACZ, JH; software, JT, SAC, ACZ.; validation, SAC, HRM; writing—original draft preparation, JT, SAC, HRM; writing—review and editing, SAC, HRM, ACZ, JH; visualisation, JT, HRM; supervision, HRM, SAC, ACZ, JH; project administration, HRM; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Future Fuels Cooperative Research Centre for providing funding for this work through project RP1.2-04. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this paper, whose comments have improved its quality significantly.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1. High-level overview of potential linkages between the SDGs and major renewable energy types with supporting literature.

Appendix B

Table B1. The full list of SDG indicators and their corresponding questions.

Appendix C

Table C1. The complete mapping of the relationship between Diagnostic Questions and SDGs.

Appendix D

Table D1. The comprehensive relationships between the 14 Project-Level Decision Themes and the 63 Diagnostic Questions.

Appendix E

Detailed functions of the MS Excel diagnostic tool.

Appendix F

Table F1. Full set of responses to all Diagnostic Questions for Case Study 1.

Appendix G

Table G1. Full set of responses to all Diagnostic Questions for Case Study 2.

Appendix H

Table H1. Full set of responses to all Diagnostic Questions for Case Study 3.

References

- Konietzko, D. J., Moving Beyond Carbon Tunnel Vision With a Sustainability Data Strategy. Forbes, April 2022, 7.

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Tomei, J.; To, L. S.; Bisaga, I.; Parikh, P.; Black, M.; Borrion, A.; Spataru, C.; Castán Broto, V.; Anandarajah, G. , Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Energy 2018, 3(1), 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F., Sustainable development report 2022. Cambridge University Press: 2022.

- Colglazier, W., Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, (6252), 1048-1050.

- Bisaga, I.; Parikh, P.; Tomei, J.; To, L. S. , Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the sustainable development goals: A case study of off-grid solar energy in Rwanda. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Culley, S. A.; Maier, H. R.; Zecchin, A. C. Is renewable energy sustainable? Potential relationships between renewable energy production and the Sustainable Development Goals. npj Climate Action 2024, 3(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lucia, L.; Slade, R.; Khan, J. Decision-making fitness of methods to understand Sustainable Development Goal interactions. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5(2), 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigim, K.; Munier, N.; Green, J. Pre-feasibility MCDM tools to aid communities in prioritizing local viable renewable energy sources. Renewable energy 2004, 29(11), 1775–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castor, J.; Bacha, K.; Nerini, F. F. SDGs in action: A novel framework for assessing energy projects against the sustainable development goals. Energy research & social science 2020, 68, 101556. [Google Scholar]

- Delafield, G.; Donnison, C.; Roddis, P.; Arvanitopoulos, T.; Sfyridis, A.; Dunnett, S.; Ball, T.; Logan, K. G. Conceptual framework for balancing society and nature in net-zero energy transitions. Environmental Science & Policy 2021, 125, 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics, U. Global indicator framework for the sustainable development goals and targets of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Developmental Science and Sustainable Development Goals for Children and Youth 2019, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. The global reporting initiative. The CPA journal 2003, 73(6), 60. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Gastaldi, M.; Ghiron, N. L.; Montalvan, R. A. V. Implications for Sustainable Development Goals: A framework to assess company disclosure in sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 319, 128624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. K. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact assessment and project appraisal 2012, 30(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzler, K.; Maier, S. D.; Jäger, M.; Horn, R. SDG-based sustainability assessment methodology for innovations in the field of urban surfaces. Sustainability 2020, 12(11), 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blix, T. B.; Myhr, A. I. A sustainability assessment framework for genome-edited salmon. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act, E. Environment protection and biodiversity conservation act. Commonwealth of Australia 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Large-Scale Solar Energy Guideline. Available online: https://shared-drupal-s3fs.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/master-test/fapub_pdf/Lisa+Drupal+Documents/16007_DPIE+Large+Scale+Solar+Energy+Guidelines_26-9-22.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Taylor, M. Planning the energy transition: a comparative examination of large-scale solar energy siting on agricultural land in Australia. Utrecht Law Review 2022, 18(2), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. Journal of sustainable tourism 2003, 11(6), 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, F. A.; Gholamzadeh Chofreh, A.; Estaki Orakani, Z.; Klemeš, J. J.; Davoudi, M.; Mardani, A. Sustainable business model: A review and framework development. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2021, 23, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, K.; Ho, H. K.; Su, B. Sankey diagram framework for energy and exergy flows. Applied energy 2014, 136, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkaloglu, S.; Cooper, J.; Hawkes, A. Methane emissions along biomethane and biogas supply chains are underestimated. One Earth 2022, 5(6), 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.; Pearce, M.; Cromar, N.; Fallowfield, H., Audit of the quality and quantity of treated wastewater discharging from Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) into the marine environment. 2005.

- Breed, W. G.; Hatch, J. H.; Rogers, C.; Brooker, W.; Breed, A. C.; Marklund, M. H.; Roberts, H.; Breed, M. F. Bolivar Wastewater Treatment Plant provides an important habitat for South Australian ducks and waders. Australian Field Ornithology 2020, 37, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food or energy? The battle over the future of Australia's prime agricultural land. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2019-05-23/battle-over-the-future-of-prime-australian-agricultural-land/11140144 (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Longest running solar farm contract dispute finally settled after more than two years. Available online: https://reneweconomy.com.au/longest-running-solar-farm-contract-dispute-finally-settled-after-more-than-two-years/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Sunraysia solar farm finally complete and at full capacity, but legal dispute remains. Available online: https://reneweconomy.com.au/sunraysia-solar-farm-finally-complete-and-at-full-capacity-but-legal-dispute-remains/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- RE: Sunraysia Solar Farm, Balranald LGA. Available online: https://majorprojects.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/prweb/PRRestService/mp/01/getContent?AttachRef=SSD-7680%2120190513T232207.075%20GMT (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Re: NSW Solar Farm - Water Usage During Construction. Available online: https://majorprojects.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/prweb/PRRestService/mp/01/getContent?AttachRef=SSD-7680%2120190227T235409.272%20GMT (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Sunraysia Solar Farm (SSD 7680). Available online: https://majorprojects.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/prweb/PRRestService/mp/01/getContent?AttachRef=SSD-7680%2120190227T235438.469%20GMT (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Shields, M. A.; Woolf, D. K.; Grist, E. P.; Kerr, S. A.; Jackson, A.; Harris, R. E.; Bell, M. C.; Beharie, R.; Want, A.; Osalusi, E. Marine renewable energy: The ecological implications of altering the hydrodynamics of the marine environment. Ocean & coastal management 2011, 54(1), 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar Wastewater Treatment Plant. Available online: https://watertalks.sawater.com.au/bolivarwwtp (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Sunraysia Solar Farm: 255MWDC utility-scale solar PV project. Available online: https://sunraysiasolarfarm.com.au/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Star of the South. Available online: https://www.starofthesouth.com.au/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Kwasinski, A.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Song, J.; Sharma, R. Availability evaluation of micro-grids for resistant power supply during natural disasters. IEEE Transactions on Smart grid 2012, 3(4), 2007–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K. J.; Jones, G. A. A population-induced renewable energy timeline in nine world regions. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzen, J.; Lakshmipathy, S.; Kapahi, A.; Kraft, S.; DiDomizio, M. Lithium ion battery energy storage systems (BESS) hazards. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2023, 81, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024 ISP Consultation. Available online: https://aemo.com.au/energy-systems/major-publications/integrated-system-plan-isp/2024-integrated-system-plan-isp (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Nelsen, J. L., Social license to operate. In Taylor & Francis: 2006; Vol. 20, pp 161-162.

- Rahman, A.; Farrok, O.; Haque, M. M. Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: Solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 161, 112279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. W.; Sadiq, M.; Terriche, Y.; Naqvi, S. A. R.; Mutarraf, M. U.; Hassan, M. A.; Yang, G.; Su, C.-L.; Guerrero, J. M. Offshore wind farm-grid integration: A review on infrastructure, challenges, and grid solutions. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 102811–102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).