1. Introduction

In 2023, 7.2 million hectares of vineyards were cultivated worldwide [

1]. In the same year, 35,000 hectares were cultivated in Mexico [

2]. Additionally, 455,000 tons of grapes were harvested, of which 73,000 tons were designated for wine production [

3]. The state of Coahuila is one of the most important wine regions in Mexico, and it is known for its winemaking tradition, which dates back several centuries. The ethnobiological significance of grapes in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, is notable; this fruit was present before the Spanish arrived and was utilized by indigenous tribes such as the Mexicas. Although the exact amount of wine produced in Coahuila can vary annually depending on the harvests and climatic conditions, Coahuila generally produces about 20% of Mexican wine, and Parras de la Fuente is the main producer, accounting for approximately 95% of the state’s production [

4].

Grape pomace is the primary by-product of the wine industry, representing approximately 30% of the total weight of the grapes used for wine production [

5]; this means that approximately 21,900 tons of grape pomace are generated annually in Mexico, specifically in the region of Parras, Coahuila, around 4,380 tons of grape pomace are produced (empirical calculation based on data obtained from Ramirez, 2023 [

4].

Grape pomace is a waste discarded in municipal landfills, leading to significant environmental pollution as it decomposes. There is a strong emphasis on protecting the environment [

6]. Therefore, it is crucial to find ways to reuse and develop new bioproducts made from grape pomace [

7].

The generation of grape pomace waste in Mexico, particularly in Coahuila, has risen in recent years due to the influx of international wineries operating in the region over the past decade, totaling 22 wineries [

8]. This growth makes Coahuila the second-largest wine-producing state in the country. The quality of the grapes produced in the region contributes to its reputation; however, this has also led to serious environmental pollution due to the massive accumulation of waste in fields and landfills, as there is no defined use for it. While a small portion of this waste is utilized as livestock feed, the majority poses an environmental challenge, as there are currently no waste recovery initiatives in the area. This situation presents an opportunity to add value to the primary by-product of the wine industry.

This by-product is gaining increasing attention in food research due to its rich content of bioactive compounds and functional properties [

9,

10,

11]. Recent research has highlighted the significant potential of this by-product as a functional ingredient in food production, driven by its nutritional characteristics and beneficial effects on human health [

12,

13,

14].

This study will explore the production of grape pomace flour (GPF) from this residue as an alternative for valorization [

15]. GPF is produced by grinding dried pomace, and its inclusion in food products enhances their nutritional value, functionality, and sensory properties. The bioactive compounds found in GPF include polyphenols, anthocyanins, flavonoids, and dietary fiber. These compounds are linked to beneficial effects such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective activities [

14,

16,

17,

18]. It has also been reported that gluten-free bioproducts can be formulated from grape pomace flour [

18,

19].

This study aimed to determine the nutritional and functional properties of grape pomace flour (GPF) from grapes cultivated in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, to predict its potential applications in the food industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Plan

The study was conducted in three experimental phases:

Phase 1: Grape Pomace Flour (GPF) was generated from the grape residue, and the effect of 4 particle sizes on color parameters was evaluated by a completely randomized design with one factor (particle size) and four levels (550, 450, 250, and <180 µm) and color parameters L*, a*, and b* as response variables.

Phase 2: Nutritional properties of GPF were evaluated by a uni-factorial design with particle size <180 µm as the only level and Moisture, Ash, Minerals, Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrate as response variables.

Phase 3: The functional properties of GPF: Water Solubility Index (WSI), Swelling Power (SP), Water Absorption Index (WAI), and Oil Absorption Index (OAI) were evaluated using commercial wheat flour as control. Total phenolic content and compound identification were also performed.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Chemical Reagents

Cellulose filter paper (Whatman®, U.S.A.), petroleum ether (Sigma-Aldrich®, U.S.A.), distilled water (J.T. Baker®, U.S.A. ), concentrated sulfuric acid, 0.1 N hydrochloric acid (Merk Millipore®, Germany), commercial wheat flour (HT) “Escudo Anaya” (Moldeo Anaya®, Mexico), whole wheat flour (HTi) “San Blas” (Molinos San Blas®, Mexico) and vegetable oil (Merk Millipore®, Germany), commercial wheat flour (HT) “Escudo Anaya” (Moldeo Anaya®, Mexico), whole wheat flour (HTi) “San Blas” (Molinos San Blas®, Mexico) and commercial edible vegetable oil “123” (Deli Max®, Mexico).

2.2.2. Plant Material

17 kg of wet grape pomace was kindly provided by the red wine production factory of the Technological University of Parras (UTP) (2023 campaign), located in Parras de la Fuente (Coahuila, Mexico); grape pomace was sourced from the production of wine made from Tempranillo grapes and had the following characteristics: total acidity of 6.7%, pH 3.8, and 25.6 °Bx. Grape pomace was immediately transported to the Research Center and Ethnobiological Garden (CIJE) food laboratory of the Autonomous University of Coahuila (UAdeC) located in Viesca, Coahuila, for future analysis.

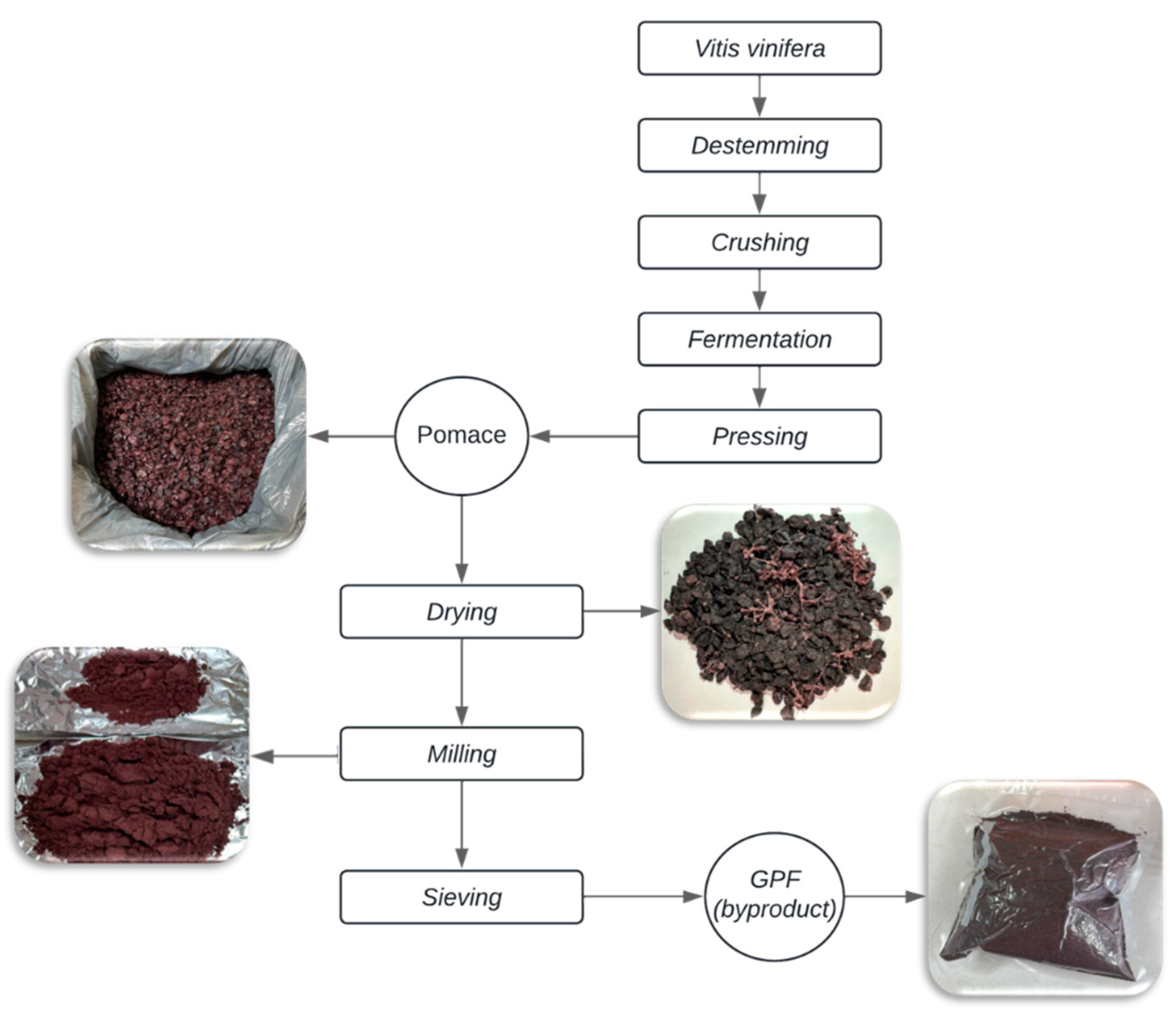

2.3. Grape Pomace Flour (GPF)

The complete pomace (seeds, skins, and stems) was dried in an oven (ICB®, Mexico) for 96 hours at an average temperature of 60 °C. After drying, the grape pomace was milled using a paddle impact mill (RETSCH®, Germany) until a fine powder was obtained. The particle size of the GPF was determined using dry sieve analysis, a conventional method for assessing particle size distribution. For this purpose, stainless steel sieves (Fiicsa®, Mexico) with mesh sizes of 550, 450, 250, and <180 µm were employed. The GPF was vacuum-packed in transparent, food-grade bags with a capacity of 1 kg.

Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the process used to obtain grape pomace flour (GPF), and the bags were stored in a dark place at room temperature. The production yield of GPF was calculated using formula 1:

2.3.1. Color Analysis in GPF

Color analysis (WR-10QC colorimeter, FRU®, China) was performed on flours with different particle sizes to identify the effect of milling on color and possible applications in food development. Measurements were taken at three points for each sample to represent color accurately. The data were read directly from the equipment and expressed in terms of the parameters L*, a*, and b*. L*: Indicates the brightness of the sample, with values ranging from 0 (black) to 100 (white). a*: Represents the color trend on the red-green scale. b*: Indicates the color trend on the yellow-blue scale.

2.4. Nutritional Properties of GPF

2.4.1. Determination of Moisture, Ash, Minerals, Fat, Protein, fiber and Carbohydrate

Moisture content was determined using the AOAC 2005 method 925.09 [

20]. A drying oven (ICB®, Mexico) was used to dry 1 g of the sample to a constant weight at 105 °C for 4 hours. The sample was then cooled in a desiccator for 30 minutes. The moisture percentage was calculated based on weight difference using an analytical balance (OHAUS Adventurer®, USA).

For ash determination, 5 g of the sample was weighed in pre-tared porcelain crucibles. The sample was pre-calcined on a grill and then fully calcined in a muffle furnace (Feliza®, Mexico) at 525 °C for 5–12 hours. After cooling, the samples were weighed to determine their ash percentage [

21].

Determining minerals in grape pomace flour was conducted in triplicate using X-ray fluorescence equipment (Panalytical Epsilon 1, Netherlands) [

22]. The samples were heat-treated at 600 °C for 1 hour to assess ignition losses in a muffle furnace (Thermolyne, USA). The weight percentages of the elements were calculated based on the ash percentage of the material.

Fat content was determined using a Soxhlet extraction system (Scorpion Scientific®, Mexico). 1 g sample was weighed on Whatman brand cellulose paper, and 8 mL of petroleum ether was added at a temperature range of 30–75 °C and allowed to stand for 3 hours. Afterward, the remaining ether was evaporated, and the change in weight of the flask was recorded and expressed as a percentage [

23].

Protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method for total nitrogen analysis [

24]; 1 g sample was digested with sulfuric acid and then subjected to automatic distillation using a CTR Scientific® distiller (Mexico). After distillation, the sample was titrated with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid. A factor of 6.25 was applied, multiplying this factor by the percentage of nitrogen obtained to calculate the total protein content.

The fiber content was measured using the AOAC 991.43 acid and alkaline hydrolysis method [

25]. A 2 g defatted sample was placed in a Berzelius glass with 100 mL of 0.225 N sulfuric acid (Fisher Scientific, USA) and connected to reflux equipment for 30 minutes. After boiling, it was dried, filtered with a linen cloth, washed with hot distilled water, and checked for acid traces with litmus paper (Whatman, England). The remaining fiber was then treated with 100 mL of 0.313 N sodium hydroxide (Fisher Scientific, USA) in reflux for 30 minutes, filtered, and washed, verifying the alkaline reaction. The fiber was dried in an oven (ICB®, Mexico), Germany) at 100 °C for 12 hours, weighed, and then incinerated in a muffle furnace (Feliza®, Mexico) at 550 °C for 3 hours, with the final weight recorded.

Finally, the carbohydrate content was calculated as the percentage difference based on the results of the other determinations [

26].

2.5. Functional Properties of GPF

2.5.1. Determination of Water Solubility Index (WSI), Swelling Power (SP), Water Absorption Index (WAI), and Oil Absorption Index (OAI)

Three 0.5 g samples of GPF were weighed using an analytical balance (OHAUS Adventurer®, USA) and placed in centrifuge tubes. Then, 6 mL of distilled water at 30 °C was added to each tube, and the tubes were placed in a shaking incubator for 30 minutes (Lab Instruments®, Mexico). The samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 minutes in a centrifuge (Lab Instruments®, Mexico). The supernatant was decanted, its volume was measured, and 2 mL of the filtrate was taken for drying at 90 °C for 4 hours. The gel retained in the tubes was weighed and recorded to calculate the Water Solubility Index (WSI), Swelling Power (SP), and Water Absorption Index (WAI) according to equations 2, 3, 4, and 5 [

27]. Commercial vegetable oil was used instead of water to determine the Oil Absorption Index (OAI).

2.5.2. Determination and Identification of Bioactive Compounds of GPF

2.5.2.1. Preparation of GPF Extracts

Methanol extracts were prepared with 25 mL of solution (methanol/ water) (80% v/v), and 2.5 g of GPF sample homogenized with the Ultra-Turrax apparatus (T18, Wilmington, USA) at 24,000 rpm for 1 min. The mixture was left under continuous stirring (300 rpm) at room temperature for 30 min. Each resulting sample was centrifuged (4480g for 15 min, 4 °C), and the supernatants were collected and filtered by 0.45 μm (Orange Scientific, Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium). Only 15 mL aliquot of the extracts were evaporated to dryness (30 °C) in the RCV 2–18 speed-vacuum evaporator (Chris. Osterode am Harz. Germany) and stored at −20 °C until their analysis.

2.5.2.2. Total Polyphenol Content

Total phenolic content (TPC) of the GPF extracts was determined by Folin–Ciocalteu method [

28], 80 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent 10% (v/v) was added to 20 µL of extract (previously dissolved in distilled water), followed by 100 µL of sodium carbonate (7.5% (m/v)) and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature (23 °C) for 1 h. After that, absorbance was measured at 750 nm (Microplate Spectrophotometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in a 96-well microplate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Gallic acid was used as a standard for the calibration curve, and the results were expressed as milligrams equivalent of gallic acid per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g DE).

2.5.2.3. Phenolic Compounds Identification by HPLC

The quantitative profile of phenolic compounds in GPF extracts (previously dissolved in ultrapure water) was performed using a Waters Alliance e2695 separation module system interfaced with a photodiode array UV/Vis detector 2998 (PDA 190–600 nm) (Waters, USA). The compounds were separated in a reverse-phase C18 column (COSMOSIL 5C1 8-AR-II Packed Column–4.6 mm I.D. x 250 mm; Dartford, UK). The mobile phases and the gradient program were prepared according to Oliveira et al. [

28] with some modifications. The mobile phase was composed of solvent A:Water/acetonitrile/TFA (94.9/5/0.1%) and solvent B: Acetonitrile/TFA (99.9/0.1%) with the elution gradient: 0–1 min 0% B; 1–30 min 21% B; 30–42 min 27% B; 45–55 min 58% B; 55–60 min0%B, and kept another 1 min at 0% B. Flow rate was 1mL/min, the oven temperature was set as 25 °C, and the injection volume was 20 µL. Detection was performed at 280 nm, 320 nm, 360 nm, and 520 nm, while data acquisition and analysis were accomplished using Software Empower 3. Compounds were identified by comparing the retention times and spectra with pure standards (HPLC grade).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Determinations were conducted in triplicate, and the results were expressed as percentages, means, and standard deviations (±). Statistical analysis was performed using Tukey’s mean comparison test (p<0.05) with Statistica® (Software, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Grape Pomace Flour (GPF)

GPF production yielded 13 kg, resulting in % overall yield of 76.5%. The yield obtained in GPF was higher than that determined in Pinot noir grape pomace flour from white wine from Brazil (11%) [

29].

3.1.1. Color Analysis in GPF

Visual perception typically serves as the first impression of food, and color influences acceptability [

30]. The determination of the color parameters at different particle sizes is shown in

Table 1. These findings reveal a relationship between particle size and color. An increase in the L* value was observed as particle size decreased, while the a* and b* values decreased with smaller particle sizes of GPF. Furthermore, the table indicates that the color obtained from the size fraction below 180 µm closely resembles the characteristic color of grapes. This aligns with the average particle size recommended for flours by the Mexican Official Standard NOM-247-SSA1-2008 [

31], validating this particle size as appropriate for GPF. A smaller particle size also directly affects the digestion of the nutrients present in the flour [

30]. Tukey’s mean comparison test (p<0.05) indicates that there are no significant differences in “L*” values for particle sizes <180 µm and 250 µm; however, significant differences are observed for 425 µm and >425 µm. The results for parameter “a*” revealed that all values are statistically different, while the results for parameter “b*” exhibited a trend similar to that of parameter “L*”. Based on the above, a particle size of less than 180 µm was chosen for subsequent studies.

The color of GPF indicates antioxidant quality; the color of pomace is mainly attributed to phenolic compounds, which have important antioxidant properties. To continue this interesting topic, the final section of the manuscript will be the determination and identification of phenolic compounds.

3.2. Nutritional Properties of GPF

3.2.1. Determination of Moisture, Ash, Minerals, Fat, Protein, fiber and Carbohydrate

Results presented in

Table 2 indicate that GPF has a moisture content of 4.4 ± 0.17 %, which is within the permissible limit set by CODEX STAN 152-1985, which states that moisture in flour should not exceed 15%. The moisture value determined in GPF is lower than those reported in other agro-industrial waste flours such as chontaduro flour (11%) [

32], cocoa shell flour (10%) [

33], and quinoa flour (10%) [

34].

The ash content determined in GPF was 13.7%. As shown in

Table 3, the main minerals found in Mexican grape pomace flour were potassium, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, silicon, chlorine, and iron. Potassium, calcium, and phosphorus have been previously reported as the main minerals in European grape pomace [

35]. However, in the case of Mexican grape pomace, magnesium was the second largest mineral found after potassium, so it can be established that this residue is a good source of magnesium. Magnesium is essential in the human body; this mineral is essential in energy production, the construction of proteins and nucleic acids, insulin function, healthy nerve and muscle function, the immune system, heart rate stability, and blood circulation [

36]. Potassium, the main mineral found, is considered an essential mineral to help maintain osmotic balance in humans and plays an essential role in reducing blood pressure and the risk of osteoporosis due to reduced urinary calcium excretion [

37]. Calcium, another mineral in Mexican grape pomace in high concentrations, is essential for forming and maintaining bones and skeletal integrity [

38]. Nutritional insecurity is associated with a deficiency of micronutrients that play an essential role in the normal metabolic functioning of the human body [

39], and agro-industrial waste such as grape pomace can be a very good source of these micronutrients [

40].

The protein value determined in GPF (11.9%) (

Table 2) was higher than that reported in grape pomace flour from ‘Vinhão’ variety from Portugal (9%) [

41] and grape pomace from Quinta de Azevedo (9.8%) [

42] and lower than that reported in Pinot noir grape pomace flour from white wine from Brazil (13%) [

29]. The lower protein value in red wines compared to white wines is due to the alcoholic fermentation process [

29].

Dietary fiber in GPF was 14.9%. Flours with 10 – 20 % fiber can help maintain intestinal health, reduce cholesterol, and regulate blood sugar levels [

43]. The fiber content in GPF indicates that incorporating it into food products enhances their nutritional profile [

44]. Overall, GPF has been recognized as an excellent opportunity to transform a waste product into a valuable bioproduct, thereby adding value to the wine industry.

The fat value obtained in this study for GPF was 9.4%. This result was higher than that reported for grape pomace flour from the cultivar ‘Vinhão’ from Portugal (3.3%) [

41] and grape husk flour from the cultivar Marselan (5.1%) from Brazil [

42]. The higher lipid content in Mexican grape pomace may be due to the greater presence of seeds.

3.3. Functional Properties of GPF

3.3.1. Determination of Water Solubility Index (WSI), Swelling Power (SP), Water Absorption Index (WAI), and Oil Absorption Index (OAI)

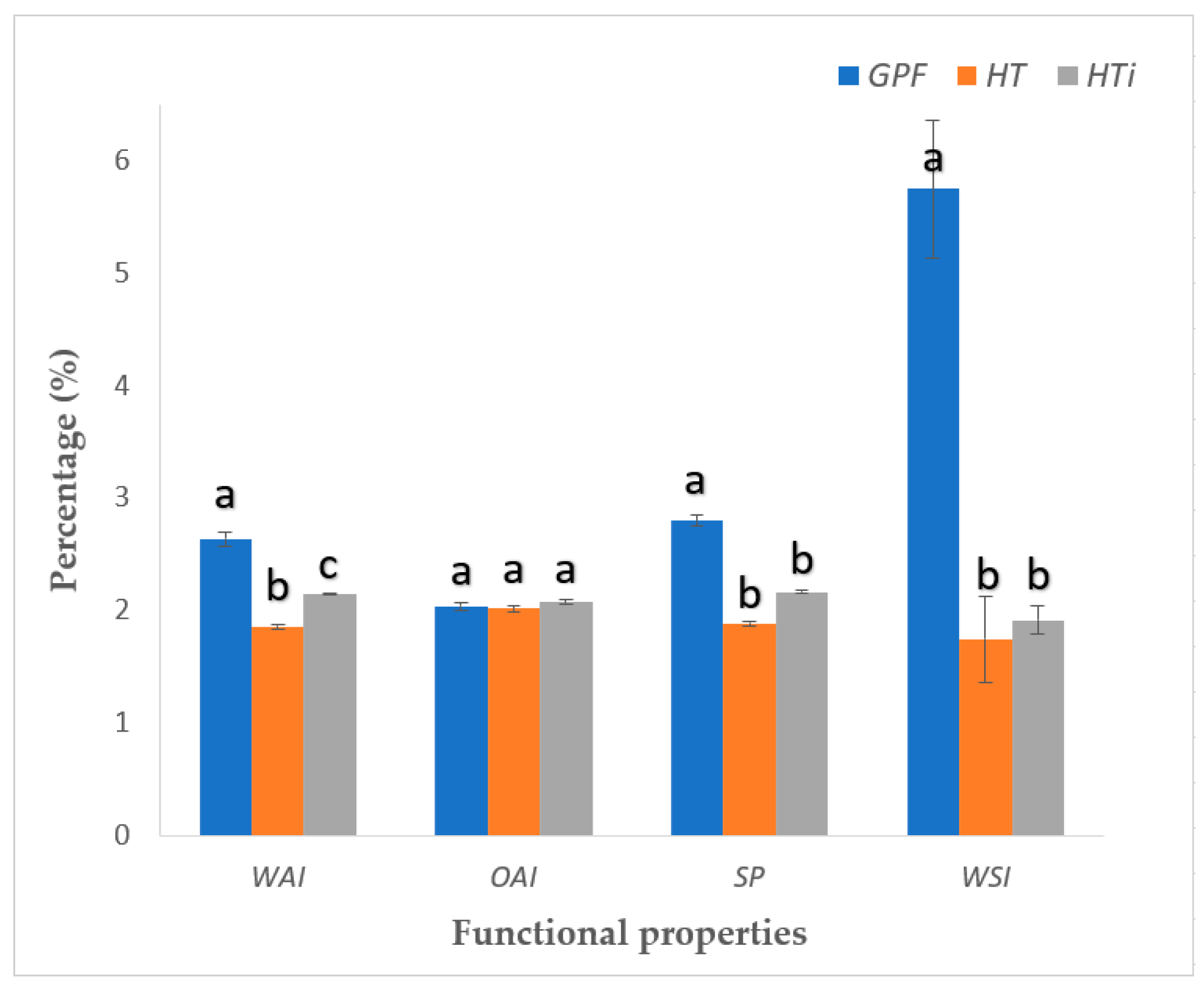

WAI reflects the amount of water that the flour can retain. As shown in

Figure 2, GPF significantly exhibited the highest WAI value (2.64 ± 0.06 g/g), followed by whole wheat flour (HTi) (2.15 ± 0.01 g/g) and regular wheat flour (HT) (1.86 ± 0.02 g/g). The WAI value for GPF exceeds those reported for other non-conventional flours, such as rice flour (1.25 ± 0.01 g/g), amaranth flour (0.96 ± 0.01 g/g), quinoa flour (1.15 ± 0.04 g/g), and chickpea flour (1.92 ± 0.09 g/g) [

45]. A higher water holding capacity is advantageous as it enhances the texture of the products, and these elevated values are attributed to the higher fiber content in the flour [

46].

The determination of OAI revealed that GPF (2.04 ± 0.03 g/g) did not present a significant difference with respect to HT (2.02 ± 0.03 g/g) and HTi (2.08 ± 0.02 g/g) (

Figure 2).

The OAI value of GPF (2.04 ± 0.03 g/g) is higher than the 1.4 ± 0.3 g/kg reported in quinoa seeds [

47] and is comparable to values found in some cereals, such as rice [

48]. This is advantageous, as a higher oil absorption capacity is desirable in bioproducts intended for baking applications [

47].

In the present study, the determination of SP revealed that GPF (2.80 ± 0.05 mL/g) was significantly higher than the values obtained for HT and HTi flours (1.89 ± 0.02 mL/g and 2.17 ± 0.01 mL/g, respectively). The SP values indicate a strong ability of the flour to increase in volume by absorbing liquids; this characteristic enhances the overall texture of bioproducts and is crucial for preparing viscous foods such as doughs and baked goods, ensuring proper interaction between proteins and water [

49].

Finally, in the essay on WSI, GPF (5.75 ± 0.61 %) was significantly higher than HT and HTi (1.75 ± 0.38 % and 1.92 ± 0.12 %, respectively). The WSI for GPF is comparable to that of banana flour (5.50 ± 0.38 %) [

50] and blue corn flour (5.70 ± 0.04 %) [

51]. These studies suggest that the solubility index is related to the soluble solids content in the flour, and the WSI measures the amount of dissolved matter in water, indicating the degradation of components within the food matrix [

52].

The moisture analysis of the evaluated flours revealed that GPF has a significantly lower moisture content (4.87%) compared to the two commercial flours: HT (11.04%) and HTi (11.03%). GPF is a bioproduct well within the maximum moisture limit (15%) for flours set by Mexican Official Standard NOM-247-SSA1-2008 [

31]. Moisture content is critical in product quality and shelf life of flours and influences the preservation and susceptibility to deterioration by microorganisms [

53].

3.3.2. Determination and Identification of Bioactive Compounds of GPF3.3.3. Determination of Total Polyphenolic Content

The total polyphenol content of grape pomace flour (GPF) showed that it is a significant source of these compounds, with a value of 0.97 ± 0.03 mg GAE g⁻¹. The results obtained are higher than those of some studies that tested different extraction methodologies for bioactive compounds from grape pomace. Monteiro, 2021 [

54] obtained 0.30 ± 0.261 mg GAE g⁻¹, using a mixture of reagents (methanol: water) for extraction, combined with ultrasound. Aresta et al., 2020 [

55] obtained 0.57 ± 0.01 mg GAE g⁻¹ for a supercritical fluid extraction using carbon dioxide and ethanol as a co-solvent to increase the low polarity of carbon dioxide and facilitate the extraction of polar compounds.

Grape pomace flour, a rich source of total polyphenols (TPC), is an excellent option for developing functional and nutraceutical foods due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. Polyphenols are the most abundant antioxidants in the human diet, widely present in plant-based foods and beverages. Scientific evidence suggests that regular consumption of foods rich in these compounds protects against cardiovascular and degenerative diseases, cancer, and diabetes. In addition to its potential as a functional ingredient, including grape pomace flour in various food matrices would improve nutritional value and contribute to sustainability through the utilization of agricultural by-products, enhancing its potential in the food industry. It is also important to highlight that polyphenols are rapidly absorbed and metabolized in the human body, with the gut microbiota playing a key role in this process.

3.3.4. Identification of Compounds by HPLC

The individual phenolic compounds of GPF extracts identified using HPLC are summarized in

Table 4.

The chromatographic profile of GPF extracts indicated that phenolic acids and flavonoids are GPF’s most prevalent chemical classes. The phenolic compound identification analysis results showed that among the phenolic acids, gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, vinyl acid, syringic acid, and 4-caffeoylquinic acid were present. In the flavonoid class, rutin, kaempferol-3-O-glucoside, neodiosmin, and quercetin were identified. This result aligns with findings by Negro et al. (2021) [

56], who reported that the primary polyphenols in grape pomace are phenolic acids and flavonoids. Additionally, Chakka (2022)[

57] highlighted that grape pomace represents a significant source of bioactive, non-nutritive compounds, with phenolic acids being the most noteworthy.

The significance of phenolic acids in GPF is heightened by the wide array of functional compounds that offer health benefits. These compounds exhibit various functional properties, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral activities [

58,

59], as well as neuroprotective, antibacterial, antiosteoporotic, analgesic [

60,

61], antivenom, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, and free radical scavenging activities [

62,

63], alongside cardioprotective, antidiabetic, and antiendotoxic properties [

64,

65,

66].

The functional properties provided by the presence of flavonoids in GPF include antioxidative, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective activities, and improvements in metabolic function [

68,

69], as well as antirheumatic, antioxidant, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, anti-obesity, antiosteoporotic, anticancer, and antiulcer effects [

59,

70]; prevention of osteoporosis, antiviral [

71,

72]; and anti-allergy, blood pressure-lowering, and antiviral activities [

73,

74].

3.4. Potential Applicability of Grape Pomace Flour (GPF)

The GPF could offer several potential applications within the value chain due to the combination of its nutritional characteristics and functional properties. Such applications include Food Industry as a functional ingredient for bakery and other cocked foodstuffs, highlighting its high dietary fiber, protein, and antioxidant-rich phenolic contents. GPF can absorb water and oil, enhancing the texture and stability of final products such as bread, cookies, and muffins while also reducing the need for fats and other additives in these formulations; in Healthy and Dietary Foods Developments, the inclusion of GPF could be beneficial, exploiting its low moisture and high fiber content as a promotor of gut health related to the potential prebiotic effect, also could control cholesterol, and aid in blood sugar management. Additionally, as a plant base by-product rich in natural antioxidants, it plays a significant role in the development of nutraceutical and functional foods, aiming the prevention of chronic diseases like obesity, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer;

Natural Colorant and Flavor Substitute is another trend application; the natural color of GPF, derived from phenolic compounds, mostly anthocyanins, offers visual appeal for industries and final consumers and could be used as a natural additive in food products, especially in applications where a distinctive color is needed, avoiding synthetic additives; Gluten-Free Products, the GPF could be a sustainable attentive for gluten-free products production, making it suitable for people with gluten intolerance issues in products such as pasta, snacks, and cookies; Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries also can be reached due to the high antioxidant properties of GPF, which can boost natural skincare products and dietary supplements, exerting its anti-inflammatory and protective properties against oxidative damage.

4. Conclusions

Grape pomace flour (GPF) demonstrates exceptional functional and nutritional properties, positioning it as a promising ingredient for the food industry. Its ability to enhance texture and stability in baked goods and its high antioxidant and fiber content support its use in functional and health-oriented foods. Additionally, GPF provides aesthetic benefits as a natural colorant. This improves the nutritional profile of foods and promotes a circular bioeconomy by repurposing by-products from the wine industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.; methodology, C.T.; formal analysis, C.T.; research, A.G.; writing-preparation of the original draft, A.G., C.T; writing-revision and editing, A.G., C.T. and N.R.; visualization and supervision, J.A., N.R.; Investigation, A.S., C.B.; Funding acquisition, C.T.; Methodology, A.G, C.T., A.S., C.B., R.G.; Resources, R.G., J.A. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Mexican Council for Humanities, Science, and Technology CONAHCYT (Proyecto RENAJEB-2023-17).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies and Research and Research Center and Ethnobiological Garden of the Universidad Autonoma de Coahuila for the support provided for the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). State of the World Vine and Wine Sector 2023. International Organization of Vine and Wine Intergovernmental Organization, 10 April 2024. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/documents/OIV_State_of_the_world_Vine_and_Wine_sector_in_2022_2.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (SADER). Industria de la viña y vino, motor de crecimiento y empleo para 15 entidades del país. Agricultura 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/prensa/industria-de-la-vina-y-vino-motor-de-crecimiento-y-empleo-para-15-entidades-del-pais-agricultura?idiom=es (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Panorama Agroalimentario México 2018–2024, 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap/acciones-y-programas/panorama-agroalimentario-258035 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Ramírez Rebeca. Aumenta Coahuila 11% la producción de vino. Periódico Vanguardia de Coahuila, January 20, 2023. Available online: https://vanguardia.com.mx/dinero/aumenta-coahuila-11-la-produccion-de-vino-AG6091266 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- López-Astorga, M., Molina-Domínguez, C. C., Ovando-Martínez, M., & Leon-Bejarano, M. Orujo de Uva: Más que un Residuo, una Fuente de Compuestos Bioactivos. Epistemus 2023, 16(33). [CrossRef]

- Muhlack, R. A., Potumarthi, R., & Jeffery, D. W. Sustainable wineries through waste valorization: A review of grape marc utilization for value-added products. Waste Management 2018, 72, 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., You, Y., Huang, W., & Zhan, J. The high-value and sustainable utilization of grape pomace: A review. Food Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- From the vineyard to your palate. Available online: http://hazturismoencoahuila.com/index.php/portfolio/vinos Parras es un sitio vitivinícola, Torreón, Múzquiz y Piedras Negras (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Almanza-oliveros, A. Almanza-oliveros, A., Bautista-hern, I., Castro-l, C., Aguilar-z, P., Meza-carranco, Z., Rojas, R., Michel, M. R., Cristian, G., & Mart, G. Grape Pomace—Advances in Its Bioactivity, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Foods, 2024; 13, 4, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinei, M., & Oroian, M. The potential of grape pomace varieties as a dietary source of pectic substances. Foods 2021, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Han, Y., Tian, X., Sajid, M., Mehmood, S., Wang, H., & Li, H. Phenolic composition of grape pomace and its metabolism. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64(15), 4865 – 4881. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-López, J. E., Flores-Gallegos, A. C., Ascacio-Valdes, J. A., Contreras Esquivel, J. C., Torres-León, C., Rúelas-Chácon, X., & Aguilar, C. N. Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Sourced from Agroindustrial Byproducts and Its Applications. Foods 2023, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- López-Astorga, M., Molina-Domínguez, C. C., Ovando-Martínez, M., & Leon-Bejarano, M. Orujo de Uva: Más que un Residuo, una Fuente de Compuestos Bioactivos. Epistemus 2023, 16(33). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Ahmed, I. A., Özcan, M. M., Al Juhaimi, F., Babiker, E. F. E., Ghafoor, K., Banjanin, T., Osman, M. A., Gassem, M. A., & Alqah, H. A. S. Chemical composition, bioactive compounds, mineral contents, and fatty acid composition of pomace powder of different grape varieties. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2020, 44(7), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Antonić, B., Jančíková, S., Dordević, D., & Tremlová, B. Grape pomace valorization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Foods 2020, 9(11). [CrossRef]

- Baldán, Y., Riveros, M., Fabani, M. P., & Rodriguez, R. Grape pomace powder valorization: a novel ingredient to improve the nutritional quality of gluten-free muffins. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13(11), 9997–10009. [CrossRef]

- Milinčić, D. D., Kostić, A., Špirović Trifunović, B. D., Tešić, Ž. L. J., Tosti, T. B., Dramićanin, A. M., Barać, M. B., & Pešić, M. B. Grape seed flour of different grape pomaces: Fatty acid profile, soluble sugar profile and nutritional value. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2020, 85(3), 305–319. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, G. C., Minatel, I. O., Junior, A. P., Gomez-Gomez, H. A., de Camargo, J. P. C., Diamante, M. S., Pereira Basílio, L. S., Tecchio, M. A., & Pereira Lima, G. P. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of grape pomace flours. Food Science and Technology 2021, 135. [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu-Iuga, M., Dimian, M., & Mironeasa, S. Development and quality evaluation of gluten-free pasta with grape peels and whey powders. Lwt 2020, 130(March). [CrossRef]

- Bergesse, A. E., Figueroa Gisela, Y., Parra, M. L., Sontag, L. O., Nepote, V., & Ryan, L. C. Piñón flour (Araucaria araucana (Mol.) K. Koch). Obtaining and evaluating nutritional and sensory quality. Nutricion Clinica y Dietetica Hospitalaria 2020, 40(3), 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Pillco Cochan, C. J., Guzmán Loayza, D., & Cuéllar Bautista, J. E. Composición físico química y análisis proximal del fruto de sofaique “Geoffroea decorticans (Hook. et Arn.)” procedente de la región Ica-Perú. Revista de La Sociedad Química Del Perú 2021, 87(1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Siller-Sánchez, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Kumar Verma, D.; Aguilar-González, M. Solid-State Fermentation-Assisted Extraction of Flavonoids from Grape Pomace Using Co-Cultures. Processes 2024, 12, 2027. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, P., Melissa, J., Castro, L., & Beatriz, G. Producción de harinas para consumo humano a partir de la reutilización de desechos orgánicos. Minerva 2023, 4, 157–166, ISSN-E: 2697-3650.

- Goyal, K., Singh, N., Jindal, S., Kaur, R., Goyal, A., & Awasthi, R. Kjeldahl Method. Advanced Techniques of Analytical Chemistry: Volume 1 2022 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.M.P., Toro, C.R., Londoño, L. et al. Bioprocessing of pineapple waste biomass for sustainable production of bioactive compounds with high antioxidant activity. Food Measure 2023, 17, 586–606. [CrossRef]

- McCleary, B. V., McLoughlin, C., Charmier, L. M. J., & McGeough, P. Measurement of available carbohydrates, digestible, and resistant starch in food ingredients and products. Cereal Chemistry 2020, 97(1), 114–137. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sandoval E., L. A. y S. G. Influencia de la sustitución parcial de la harina de trigo por harina de quinoa y papa en las propiedades termomecánicas y de panificación de masas. Actualidad & Divulgación Científica 2012, 15(1), 199–207. [CrossRef]

- Ana A. Vilas-Boas, Débora A. Campos, Catarina Nunes, Sónia Ribeiro, João Nunes, Ana Oliveira and Manuela Pintado, Polyphenol Extraction by Different Techniques for Valorisation of Non-Compliant Portuguese Sweet Cherries towards a Novel Antioxidant Extract. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5556. [CrossRef]

- Carolina Beres, Suely Pereira Freitas, Ronoel Luiz de Oliveira Godoy, Denize Cristine Rodrigues de Oliveira, Rosires Deliza, Marcello Iacomini, Caroline Mellinger-Silva, Lourdes Maria Correa Cabral, Antioxidant dietary fibre from grape pomace flour or extract: Does it make any difference on the nutritional and functional value?, Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 2019, 56, 276–285. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S. Coloring of food by the use of natural color extracted by beetroot (Beta Vulgaris), betalain pigment. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research 2021, 9(1), 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Products and services. Flours. Sanitary and nutritional provisions and specifications. Mexican Official Standards, Government of Mexico, Pub. L. No. NOM-247-SSA1-2008, 1 (2008). Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5100356&fecha=27/07/2009#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Dussán-Sarria, S., de la Cruz-Noguera, R. E., & Godoy, S. P. Study of the amino acid profile and proximal analysis of extruded dry pastas based on quinoa flour and peach palm flour. Informacion Tecnologica 2019, 30(6), 93–100. [CrossRef]

- Burgos Briones, G., & Cedeño, U. A. Evaluación técnica del enriquecimiento de harina de trigo con cascarilla de cacao (Theobroma cacao). Colón Ciencias, Tecnologia y Negocios 2020, 7(2), 20–36. [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Tirado, L., Prieto-Rosales, G., & Aguirre, E. Caracterización de la harina de quinua (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) y la harina de tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) para su industrialización. Tayacaja 2020, 3(1), 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Caponio, G.R.; Minervini, F.; Tamma, G.; Gambacorta, G.; De Angelis, M. Promising Application of Grape Pomace and Its Agri-Food Valorization: Source of Bioactive Molecules with Beneficial Effects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9075. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Tang, M.; Wei, X.; Peng, Y. Association between Magnesium Deficiency Score and Sleep Quality in Adults: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 358, 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Antonić, B.; Jančíková, S.; Dordević, D.; Tremlová, B. Grape Pomace Valorization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2020, 9, 1627. [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J.; Razzaque, M.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M. Calcium and Vitamin D in Human Health: Hype or Real? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 180, 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Rojas, R.; Contreras, J.; Serna, L.; Belmares, R.; Aguilar, C. Mango Seed: Functional and Nutritional Properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Ramírez-Guzman, N.; Londoño-Hernandez, L.; Martinez-Medina, G.A.; Díaz-Herrera, R.; Navarro-Macias, V.; Alvarez-Pérez, O.B.; Picazo, B.; Villarreal-Vázquez, M.; Ascacio-Valdes, J. Food Waste and Byproducts: An Opportunity to Minimize Malnutrition and Hunger in Developing Countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 52. [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.R.; Voss, G.B.; Machado, M.; Paiva, J.A.P.; Nunes, J.; Pintado, M. Chemical Characterization of the Cultivar ‘Vinhão’ (Vitis Vinifera L.) Grape Pomace towards Its Circular Valorisation and Its Health Benefits. Meas. Foods 2024, 15, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Bender, A. B. B., Luvielmo, M. de M., Loureiro, B. B., Speroni, C. S., Boligon, A. A., Silva, L. P. da ., & Penna, N. G. Obtenção e caracterização de farinha de casca de uva e sua utilização em snack extrusado. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology, 2016 19. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, W., & Mendoza, D. R. Fibra alimentaria y enfermedades crónicas: FSHN18-11-Span/FS322, 11/2019. EDIS 2020, 2020(1), 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Jofre, Carla; Campderrós, Mercedes Edith; Rinaldoni, A. N. Valorización de subproductos: el orujo de uva como ingrediente funcional. La Alimentación Latinoamericana 2022, 12(364), 44–50, ISSN 0325-3384.

- Culetu, A., Susman, I. E., Duta, D. E., & Belc, N. Nutritional and functional properties of gluten-free flours. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(14). [CrossRef]

- Klunklin, W., & Savage, G. Physicochemical, antioxidant properties and in vitro digestibility of wheat–purple rice flour mixtures. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2018, 53(8), 1962–1971. [CrossRef]

- Villar, N., Esparza, M., & Sorolla, A. Physical, functional and chemical properties of flour obtained from quinoa seeds. Master Degree, Food Science and Technology, Universitat Politècnica De València, Septiembre 2021. https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/175400.

- Di Cairano, M., Condelli, N., Caruso, M. C., Marti, A., Cela, N., & Galgano, F. Functional properties and predicted glycemic index of gluten free cereal, pseudocereal and legume flours. Lwt 2020, 133 (June). [CrossRef]

- García, O., Aiello, C., Peña, M. C., Ruíz, J. L., & Acevedo, I. D. C. Caracterización físico quimicas y propiedades funcionales de la harina obtenida de granos de quinchoncho (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.) sometidos a diferentes procesamientos. Revista Cientifica Agrícola 2012, 12(4), 919–928.

- Khoza, M., Kayitesi, E., & Dlamini, B. C. Physicochemical characteristics, microstructure and health promoting properties of green banana flour. Foods 2021, 10(12), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Anaya Esparza, L. M., Gómez-Rodríguez, V. M., Ramírez Vega, H., Hernández Estrada, S., Hernández-Villaseñor, L. A., & Villagrán de la Mora, B. Z. Propiedades nutricionales, fisicoquímicas, funcionales, compuestos fenólicos y actividad antioxidante de harinas de tres accesiones de maíz azul nativo de México. INGENIERÍA: Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación 2024, 11(1), 23–39. [CrossRef]

- Forsido, S. F., Welelaw, E., Belachew, T., & Hensel, O. Effects of storage temperature and packaging material on physico-chemical, microbial and sensory properties and shelf life of extruded composite baby food flour. Heliyon 2021, 7(4), e06821. [CrossRef]

- Vivanco-Laica, S. V. Effect of calcium propionate and potassium sorbate on the shelf life of farinaceous premixes from oca (Oxalis tu-berosa), achira (Canna edulis), mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). Barchelor, Food Engineering, Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ecuador, Enero 2020.

- Monteiro, G. C., Minatel, I. O., Junior, A. P., Gomez-Gomez, H. A., de Camargo, J. P. C., Diamante, M. S., Pereira Basílio, L.S., Tecchio, M.A. & Lima, G. P. P. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of grape pomace flours. Lwt, 2021, 135, 110053. [CrossRef]

- Aresta, A., Cotugno, P., De Vietro, N., Massari, F., & Zambonin, C. Determination of polyphenols and vitamins in wine-making by-products by supercritical fluid extraction (SFE). Analytical Letters, 2020, 53(16), 2585–2595. [CrossRef]

- Negro, C.; Aprile, A.; Luvisi, A.; De Bellis, L.; Miceli, A. Antioxidant Activity and Polyphenols Characterization of Four Monovarietal Grape Pomaces from Salento (Apulia, Italy). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1406. [CrossRef]

- Ashok Kumar Chakka, Ayenampudi Surendra Babu. Bioactive Compounds of Winery by-products: Extraction Techniques and their Potential Health Benefits. Applied Food Research 2022, 2(1), 100058, ISSN 2772–5022. [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M., Liñán-Atero, R., Tarahi, M., Christodoulou, M. C., & Aghababaei, F. The Potential Health Benefits of Gallic Acid: Therapeutic and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13(8), 1001. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, S., Rabiei, Z., & Amini-Khoei, H. Exploring the multifaceted neuroprotective actions of gallic acid: A review. International Journal of Food Properties, 2020, 23(1), 736–752. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., He, Y., Luo, C., Feng, B., Ran, F., Xu, H., Ci, Z., Xu, R., Han, L., & Zhang, D. New progress in the pharmacology of protocatechuic acid: A compound ingested in daily foods and herbs frequently and heavily. Pharmacological research, 2020, 161, 105109. Pharmacological research. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shijun, Gai, Zhibo, Gui, Ting, Chen, Juanli, Chen, Qingfa, Li, Yunlun, Antioxidant Effects of Protocatechuic Acid and Protocatechuic Aldehyde: Old Wine in a New Bottle, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2021, 6139308, 19 pages. [CrossRef]

- Marzena Matejczyk, Piotr Ofman, Edyta Juszczuk-Kubiak, Renata Świsłocka, Wong Ling Shing, Kavindra Kumar Kesari, Balu Prakash, Włodzimierz Lewandowski, Biological effects of vanillic acid, iso-vanillic acid, and orto-vanillic acid as environmental pollutants, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, Volume 277, 2024, 116383. [CrossRef]

- Jaskiran Kaur, Monica Gulati, Sachin Kumar Singh, Gowthamarajan Kuppusamy, Bhupinder Kapoor, Vijay Mishra, Saurabh Gupta, Mohammed F. Arshad, Omji Porwal, Niraj Kumar Jha, M.V.N.L. Chaitanya, Dinesh Kumar Chellappan, Gaurav Gupta, Piyush Kumar Gupta, Kamal Dua, Rubiya Khursheed, Ankit Awasthi, Leander Corrie, Discovering multifaceted role of vanillic acid beyond flavours: Nutraceutical and therapeutic potential, Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 122, 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu, C., Ramgopal, M., Ramanjaneyulu, G., Anuradha, C. M., & Suresh Kumar, C. Syringic acid (SA) ‒ A Review of Its Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Pharmacological and Industrial Importance. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie, 2018, 108, 547–557. [CrossRef]

- Shimsa S., Mondal S., Mini S., Syringic Acid: A Promising Phenolic Phytochemical with Extensive Therapeutic Applications. R&D of Functional Food Products 2024; 1(5), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, A., M’rabet, Y., & Boulila, A. Caffeoylquinic Acid Derivatives: Chemical Diversity and Effect on the Oxidative Stress-Related Pathologies. Chemistry Africa, 2024, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, D., Nawrot-Hadzik, I., Kozłowska, W., Ślusarczyk, S., Matkowski, A. Caffeoylquinic Acids. In: Xiao, J., Sarker, S.D., Asakawa, Y. (eds) Handbook of Dietary Phytochemicals. Springer, Singapore. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ravindra Semwal, Sunil Kumar Joshi, Ruchi Badoni Semwal, Deepak Kumar Semwal, Health benefits and limitations of rutin - A natural flavonoid with high nutraceutical value. Phytochemistry Letters 2021, 46, 119–128. [CrossRef]

- Muvhulawa, N., Dludla, P. V., Ziqubu, K., Mthembu, S. X., Mthiyane, F., Nkambule, B. B., & Mazibuko-Mbeje, S. E. Rutin ameliorates inflammation and improves metabolic function: A comprehensive analysis of scientific literature. Pharmacological research 2022, 178, 106163. [CrossRef]

- Khaled Rashed. Kaempferol-3-o-D-glucoside bioactivities: A review. IJSIT, 2020, 9(4), 2013–217. ISSN 2319-5436.

- Chang, X., Fang, X., Yao, Y., Xu, Z., Wu, C., & Lu, L. Identification and Characterization of Glycosyltransferases Involved in the Biosynthesis of Neodiosmin. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2024, 72(8), 4348–4357. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wong, W.-L.; Guo, J. Prediction of Potential 3CLpro-Targeting Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Compounds from Chinese Medicine. Preprints 2020, 2020030247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanova M, Atanassova S, Atanasov V, Grozeva N. Content of Polyphenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Potential of Some Bulgarian Red Grape Varieties and Red Wines, Determined by HPLC, UV, and NIR Spectroscopy. Agriculture 2020, 10(6), 193. [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, D.J.; Arroyo-Hernández, M.; Posada-Ayala, M.; Santos, C. The High Content of Quercetin and Catechin in Airen Grape Juice Supports Its Application in Functional Food Production. Foods 2021, 10, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).