Submitted:

19 January 2024

Posted:

22 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and discussion

2.1. TPC and AA

2.2. Characterisation of PCs composition

2.2.1. Anthocyanins

2.2.2. Non-anthocyanins

2.3. Nutritional properties

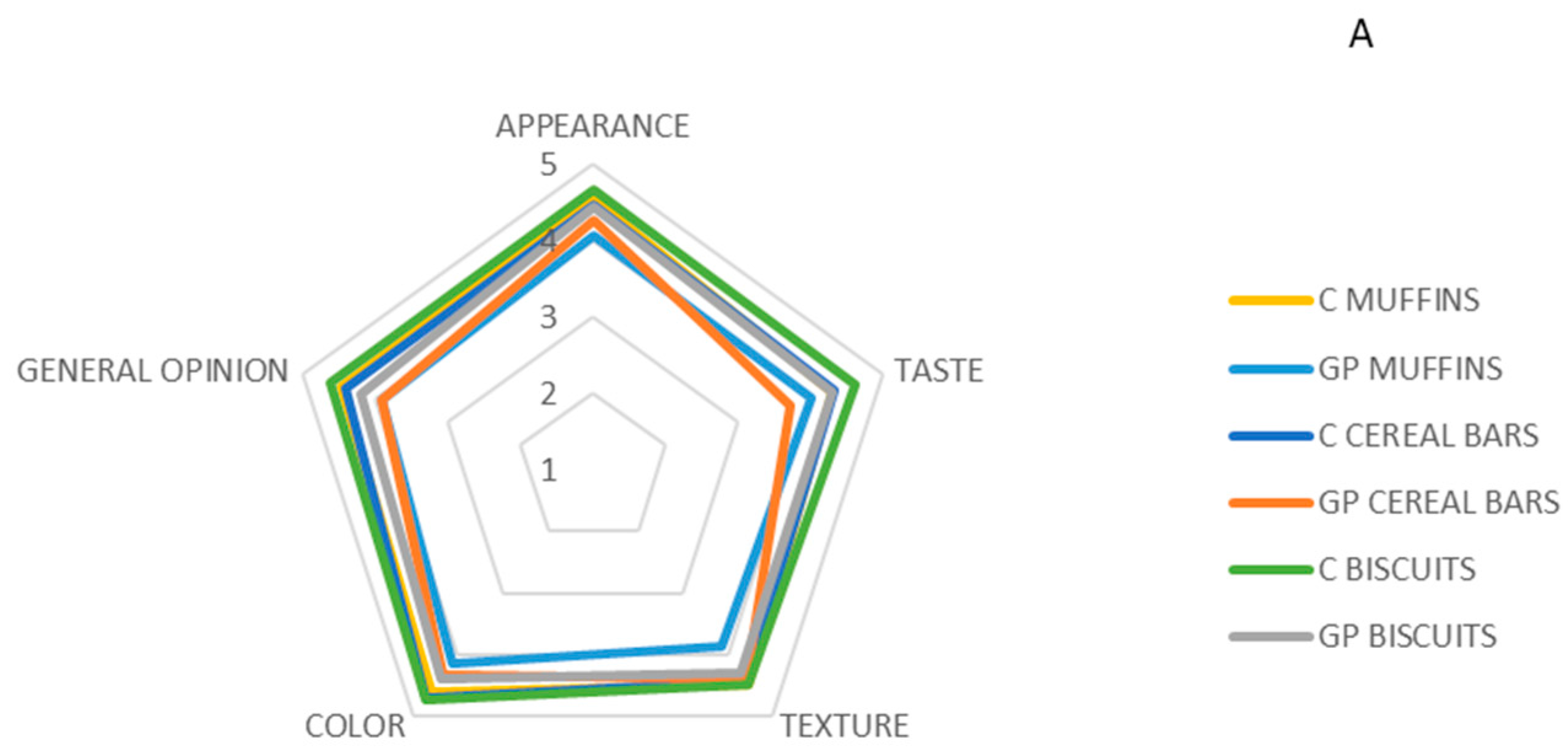

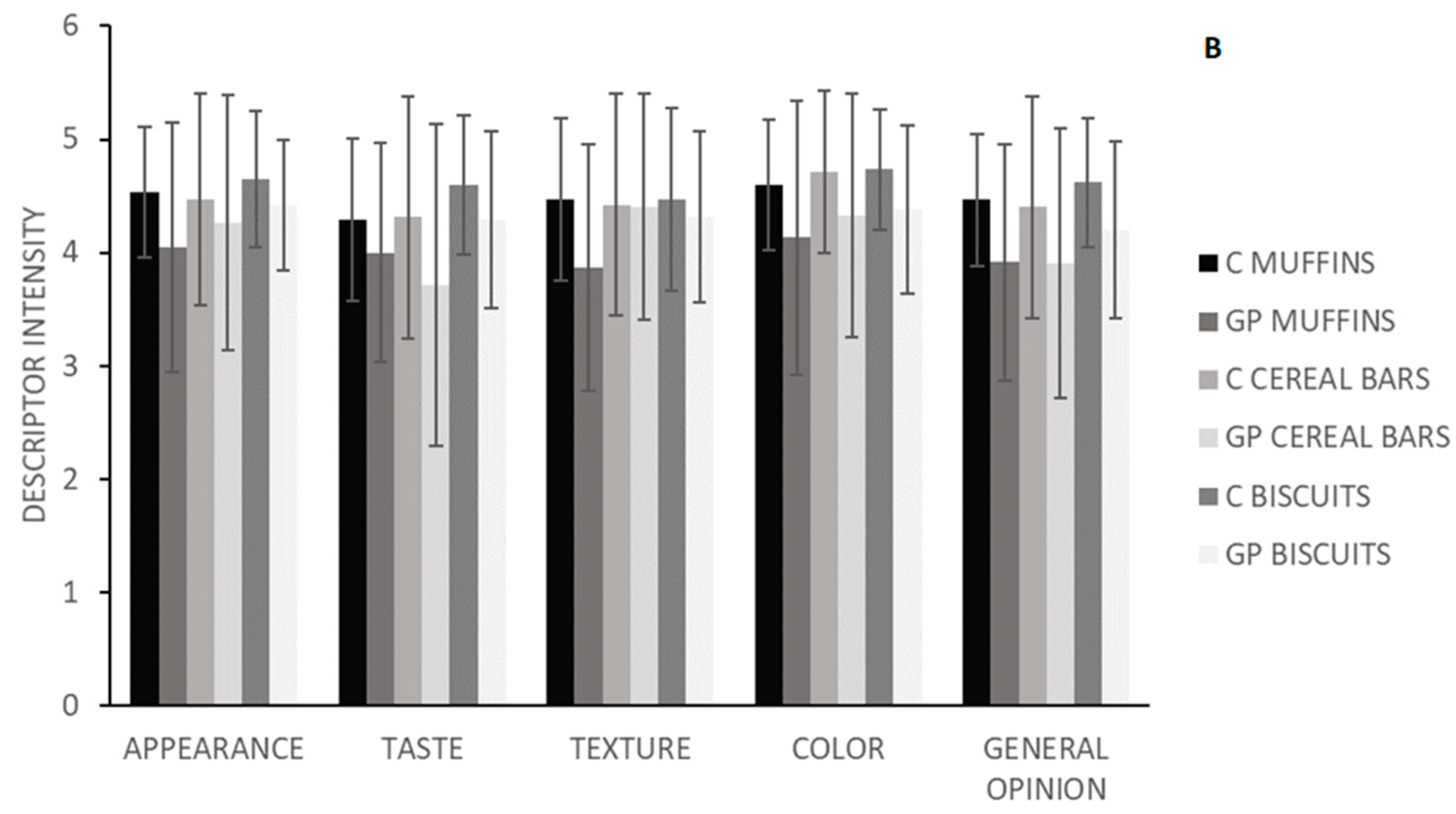

2.4. Sensory evaluation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. GP powder preparation

3.3. Foods preparation

3.3.1. Muffins

3.3.2. Biscuits

3.3.3. Cereal bars

3.4. PCs extraction

3.5. Total phenolic content (TPC)

3.6. Antioxidant activity (AA)

3.7. Non-anthocyanins PCs

3.8. Anthocyanins

3.9. Nutritional parameters

3.10. Sensory analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D. Agrochemical Characterisation of the Solid By-Products and Residues from the Winery and Distillery Industry. Waste Management 2008, 28, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasqualone, A.; Bianco, A.M.; Paradiso, V.M.; Summo, C.; Gambacorta, G.; Caponio, F. Physico-Chemical, Sensory and Volatile Profiles of Biscuits Enriched with Grape Marc Extract. Food Research International 2014, 65, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Brandón, M.; Lores, M.; Insam, H.; Domínguez, J. Strategies for Recycling and Valorization of Grape Marc. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2019, 39, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Ahmedna, M. Functional Components of Grape Pomace: Their Composition, Biological Properties and Potential Applications. Int J Food Sci Technol 2013, 48, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniolli, A.; Fontana, A.R.; Piccoli, P.; Bottini, R. Characterization of Polyphenols and Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity in Grape Pomace of the Cv. Malbec. Food Chem 2015, 178, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez Lanzi, C.; Perdicaro, D.J.; Antoniolli, A.; Fontana, A.R.; Miatello, R.M.; Bottini, R.; Vazquez Prieto, M.A. Grape Pomace and Grape Pomace Extract Improve Insulin Signaling in High-Fat-Fructose Fed Rat-Induced Metabolic Syndrome. Food Funct 2016, 7, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, F.C.; Rincón, A.M.; Bou-Rached, L. Contenido de Polifenoles y Actividad Antioxidante de Varias Semillas y Nueces. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2008, 58, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Penner, M.H.; Zhao, Y. Chemical Composition of Dietary Fiber and Polyphenols of Five Different Varieties of Wine Grape Pomace Skins. Food Research International 2011, 44, 2712–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, H.; Acun, S.; Şen, H.; Nayir, N.; Türk, S. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolics and Some Chemical Properties of Öküzgözü and Narince Grape Pomace and Grape Seed Flour. J Food Agric Environ 2013, 11, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Llobera, A.; Cañellas, J. Dietary Fibre Content and Antioxidant Activity of Manto Negro Red Grape (Vitis Vinifera): Pomace and Stem. Food Chem 2007, 101, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, J.E.; Fox, P.F. Significance and Applications of Phenolic Compounds in the Production and Quality of Milk and Dairy Products: A Review. Int Dairy J 2001, 11, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.N.; Paule, A.; Aragonès, G.; Barbosa, M.; Caddeo, C.; Debs, E.; Dinkova, R.; Eckert, G.P.; Fontana, A.; Gebrayel, P.; et al. Recent Advances in Research on Polyphenols: Effects on Microbiota, Metabolism, and Health. Mol Nutr Food Res 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mézes, M.; Erdélyi, M. Antioxidant Effect of the Fibre Content of Foods | Az Élelmiszerek Rosttartalmának Antioxidáns Hatása. Orv Hetil 2018, 159, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Centeno, M.R.; Rosselló, C.; Simal, S.; Garau, M.C.; López, F.; Femenia, A. Physico-Chemical Properties of Cell Wall Materials Obtained from Ten Grape Varieties and Their Byproducts: Grape Pomaces and Stems. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2010, 43, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordiga, M.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M. Valorisation of Grape Pomace: An Approach That Is Increasingly Reaching Its Maturity – a Review. Int J Food Sci Technol 2019, 54, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, D.; Vincenzi, S.; Gastaldon, L.; Tolin, S.; Pasini, G.; Curioni, A. The Proteins of the Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Seed Endosperm: Fractionation and Identification of the Major Components. Food Chem 2014, 155, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Hejtmánková, A.; Hejtmánková, K.; Horníčková, T.; Pivec, V.; Skala, O.; Dědina, M.; Přibyl, J. Towards Complex Utilisation of Winemaking Residues: Characterisation of Grape Seeds by Total Phenols, Tocols and Essential Elements Content as a by-Product of Winemaking. Ind Crops Prod 2013, 49, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, L.; Lavelli, V.; Duba, K.S.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Mohamed, H.B.; Guella, G. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Oil from Seeds of Six Grape Cultivars: Modeling of Mass Transfer Kinetics and Evaluation of Lipid Profiles and Tocol Contents. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2014, 94, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šporin, M.; Avbelj, M.; Kovač, B.; Možina, S.S. Quality Characteristics of Wheat Flour Dough and Bread Containing Grape Pomace Flour. Food Science and Technology International 2018, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, F.; Cervini, M.; Giuberti, G.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Simonato, B. Distilled Grape Pomace as a Functional Ingredient in Vegan Muffins: Effect on Physicochemical, Nutritional, Rheological and Sensory Aspects. Int J Food Sci Technol 2022, 57, 4847–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, A.M.; Dellacassa, E.; Nardin, T.; Larcher, R.; Ibañez, C.; Terán, D.; Gámbaro, A.; Medrano-Fernandez, A.; Del Castillo, M.D. Tannat Grape Skin: A Feasible Ingredient for the Formulation of Snacks with Potential for Reducing the Risk of Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, M.; Özuǧur, G.; Etgü, H.; Şeker, I.T. Effect of Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Pomace on the Quality, Total Phenolic Content and Anti-Radical Activity of Bread. J Food Process Preserv 2014, 38, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakov, G.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Ivanova, N.; Stamatovska, V.; Dimov, I. Effect of Grape Pomace Powder Addition on Chemical, Nutritional and Technological Properties of Cakes. LWT 2020, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Giuberti, G.; Simonato, B. Breadstick Fortification with Red Grape Pomace: Effect on Nutritional, Technological and Sensory Properties. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.; Tseng, A.; Cavender, G.; Ross, A.; Zhao, Y. Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Sensory Qualities of Wine Grape Pomace Fortified Baked Goods. J Food Sci 2014, 79, S1811–S1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Bajerska, J.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Górecka, D. White Grape Pomace as a Source of Dietary Fibre and Polyphenols and Its Effect on Physical and Nutraceutical Characteristics of Wheat Biscuits. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enaru, B.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stǎnilǎ, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: Factors Affecting Their Stability and Degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, B.; Gul, K.; Wani, A.A.; Singh, P. Health Benefits of Anthocyanins and Their Encapsulation for Potential Use in Food Systems: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 56, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, N. and A. (NDA) Scientific Opinion on the Substantiation of Health Claims Related to Various Food (s)/Food Constituent (s) and Protection of Cells from Premature Aging, Antioxidant Activity, Antioxidant Content and Antioxidant Properties, and Protection of DNA, Proteins and Lipids from Oxidative Damage Pursuant to Article 13 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1489. [Google Scholar]

- Administration, U.S.F. and D. Code of Federal Regulations (Annual Edition) 2022.

- Ferreyra, S.; Bottini, R.; Fontana, A. Temperature and Light Conditions Affect Stability of Phenolic Compounds of Stored Grape Cane Extracts. Food Chem 2023, 405, 134718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troilo, M.; Difonzo, G.; Paradiso, V.M.; Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F. Grape Pomace as Innovative Flour for the Formulation of Functional Muffins: How Particle Size Affects the Nutritional, Textural and Sensory Properties. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; Geneva, 2019.

- FDA Daily Value on the New Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels.

- European Parliament and Council Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Official Journal of the European Union 2006.

- Dávila, L.A.; Escobar, M.C.; Garrido, M.; Carrasco, P.; López-Miranda, J.; Aparicio, D.; Céspedes, V.; González, R.; Chaparro, R.; Angarita, M.; et al. Comparison of Fiber Effect on Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load in Differents Types of Bread | Comparación Del Efecto de La Fibra: Sobre El Índice Glicémico y Carga Glicémica En Distintos Tipos de Pan. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacologia y Terapeutica 2016, 35, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Granito, M.; Pérez, S.; Valero, Y. Quality of Cooking, Acceptability and Glycemic Index of Enriched Pasta with Legumes | Calidad de Cocción, Aceptabilidad e Índice Glicémico de Pasta Larga Enriquecida Con Leguminosas. Revista Chilena de Nutricion 2014, 41, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulos, K.; Costa, J.M.S.; Portugal, P. V; Spranger, M.I.; Sun, B.S.; Moreira, O.C.; DENTINHO, M.T.P. Caracterización Química y Nutricional de Los Subproductos de La Vinificación Para Aplicacion En La Alimentación de Rumiantes. Soc ESPAÑOLA OVINOTECNIA Y CAPRINOTECNIA 2005, 48, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Prandi, B.; Faccini, A.; Lambertini, F.; Bencivenni, M.; Jorba, M.; Van Droogenbroek, B.; Bruggeman, G.; Schöber, J.; Petrusan, J.; Elst, K.; et al. Food Wastes from Agrifood Industry as Possible Sources of Proteins: A Detailed Molecular View on the Composition of the Nitrogen Fraction, Amino Acid Profile and Racemisation Degree of 39 Food Waste Streams. Food Chem 2019, 286, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbeoui, H.; Dakhlaoui, S.; Wannes, W.A.; Bourgou, S.; Hammami, M.; Akhtar Khan, N.; Saidani Tounsi, M. Does Unsaponifiable Fraction of Grape Seed Oil Attenuate Nitric Oxide Production, Oxidant and Cytotoxicity Activities. J Food Biochem 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canett Romero, R.; Ledesma Osuna, A.I.; Robles Sánchez, R.M.; Morales Castro, R.; León-Martínez, L.; León-Gálvez, R. Characterization of Cookies Made with Deseeded Grape Pomace | Caracterización de Galletas Elaboradas Con Cascarilla de Orujo de Uva. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2004, 54, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreyra, S.; Bottini, R.; Fontana, A. Tandem Absorbance and Fluorescence Detection Following Liquid Chromatography for the Profiling of Multiclass Phenolic Compounds in Different Winemaking Products. Food Chem 2021, 338, 128030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, A.R.; Bottini, R. High-Throughput Method Based on Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged and Safe Followed by Liquid Chromatography-Multi-Wavelength Detection for the Quantification of Multiclass Polyphenols in Wines. J Chromatogr A 2014, 1342, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Antoniolli, A.; D’Amario Fernández, M.A.; Bottini, R. Phenolics Profiling of Pomace Extracts from Different Grape Varieties Cultivated in Argentina. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 29446–29457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Analytical Chemists International. Official Methods: Gaithersburg, MD, USA 2000.

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat Versión 2018. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. 2020. Available online: http://www.infostat. com.ar.

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE g-1 DW) |

AA (μmol TE g-1 DW) |

|---|---|---|

| Muffin control | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 7.22 ± 0.03 |

| GP Muffin | 3.28 ± 0.19 | 47.84 ± 1.55 |

| Cereal bar control | 2.58 ± 0.15 | 24.00 ± 0.49 |

| GP Cereal bar | 6.27 ± 0.19 | 75.40 ± 6.77 |

| Biscuits control | 0.94 ± 0.10 | 15.43 ± 0.45 |

| GP Biscuits | 6.35 ± 0.20 | 68.32 ± 4.86 |

| Muffin (% w/w) | Biscuit (% w/w) | Cereal bars (% w/w) |

| Flour 24 |

Flour 25 |

Honey 63 |

| Egg 27 |

Egg 46 |

Oats 17.5 |

| Sugar 27 |

Sugar 23 |

Cornflakes 10.5 |

| Butter 21 |

Sunflower Oil 5 |

Rice flakes 9 |

| Vanilla 0.5 |

Vanilla 0.5 |

|

| Baking Powder 0.5 |

Baking Powder 0.5 |

| Anthocyanin | Muffin | Cereal bar | Biscuit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delphinidin 3-O-glucoside | 14.1 ± 0.3 | 28.8 ± 0.9 | 10.4 ± 2.9 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 |

| Petunidin 3-O-glucoside | 20.2 ± 0.7 | 36.9 ± 1.1 | 9.8 ± 0.1 |

| Peonidin 3-O-glucoside | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.1 |

| Malvidin 3-O-glucoside | 160.2 ± 4.1 | 224.9 ± 8.9 | 69.7 ± 1.6 |

| Total glycosylated | 212.9 | 310.7 | 100.5 |

| Delfinidin 3-O-acetylglucoside | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| Peonidin 3-O-acetylglucoside | 60.4 ± 1.9 | 80.8 ± 3.1 | 45.2 ± 0.0 |

| Total acetylated | 69.3 | 91.8 | 52.6 |

| Cyanidin 3-O-p-coumaroylglucoside | 13.8 ± 3.2 | 16.5 ± 3.7 | 7.8 ± 0.5 |

| Peonidin 3-O-p-coumaroylglucoside | 39.1 ± 1.3 | 50.1 ± 1.7 | 25.8 ± 0.2 |

| Malvidin 3-O-p-coumaroylglucoside | 558.1 ± 31.1 | 695.8 ± 34.7 | 361.5 ± 4.3 |

| Total coumaroylated | 611.1 | 762.3 | 395.1 |

| Total anthocyanins | 893.2 | 1164.8 | 548.2 |

| GP muffin | Control | GP cereal bar |

Control | GP biscuit |

Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | ||||||

| Syringic acid | 55.4±2.7 | n.d. | 45.5±1.8 | 4.4±1.3 | 107.8±2.4 | n.d |

| Total | 55.4 | 45.5 | 4.4 | 107.8 | ||

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | ||||||

| Caffeic acid | 60.6±3.03 | n.d | 48.4±1.8 | 20.8±2.0 | 99.3±3.5 | 6.8±0.8 |

| p-coumaric acid | 35.2±1.7 | n.d | 23.2±1.1 | n.d | 35.0±1.5 | n.d |

| Ferulic acid | 3.8±0.2 | n.d | 6.5±0.1 | n.d | 10.0±0.4 | n.d |

| Chlorogenic acid | 29.6±1.5 | n.d | 121.8± 0.1 | n.d | n/d | n.d |

| Total | 129.2 | 199.9 | 20.8 | 144.3 | 6.8 | |

| Stilbenes | ||||||

| trans-resveratrol | 2.7±0.1 | n.d | 2.0±0.1 | n.d | 4.5±0.1 | n.d |

| Total | 2.7 | 2.0 | 4.5 | |||

| Flavanols | ||||||

| (+)-catechin | 44.8±2.2 | n.d | 60.1±1.3 | n.d | 51.6±3.5 | n.d |

| (-)-gallocatechin | 253.4±12.7 | 162.8±8.1 | 53.2±23.7 | 105.3±23.7 | 162.3±23.9 | 58.2±1.1 |

| Total | 298.2 | 162.8 | 113.3 | 105.3 | 213.9 | 58.2 |

| Flavonols | ||||||

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 103.7±5.2 | 126.6±6.3 | 11.0±1.7 | 44.3±8.2 | 194.8±1.7 | 285.0±5.3 |

| Quercetin | n.d | n.d | 4.7±0.8 | 4.0±0.2 | 3.9±0.2 | n.d |

| Myricetin | 4.2±0.2 | n.d | 7.6±0.2 | 5.4±0.2 | 8.0±1.1 | n.d |

| Rutin | 62.8±3.1 | 4.1±0.2 | 51.1±1.2 | 3.4±0.3 | 80.5±0.5 | n.d |

| Total | 170.7 | 130.7 | 74.4 | 57.1 | 287.2 | 285.0 |

| Other compounds | ||||||

| OH-tyrosol | 8.6±0.4 | n.d | 6.9± 0.6 | n.d | 13.3± 1.2 | n.d |

| Total | 8.6 | 6.9 | 13.3 | |||

| Total PCs | 664.8 | 293.5 | 442.0 | 186.7 | 771.0 | 350.0 |

| n.d.: not detected. |

| Sample | Moisture | Proteins | Lipids | Fiber | Carbohydrates | Ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Muffin | 20.25±0.17 | 6.6±1.15 | 21.33±0.64 | 0.32±0.09 | 50.89±0.92 | 0.68±0.15 |

| GP Muffin | 21.51±0.32 | 7.33±0.12 | 20.33±0.47 | 1.9±0.17 | 47.7±0.35 | 1.22±0.05 |

| Control Cereal bar | 14.31±0.81 | 4.13±0.32 | 0.70±0.14 | 0.49±0.08 | 80.18±1.49 | 0.40±0.02 |

| GP Cereal bar | 20.54±0.51 | 4.67±0.29 | 1.17±0.25 | 3.31±0.43 | 69.48±0.97 | 0.84±0.06 |

| Control Biscuits | 3.55±0.01 | 11.3±0.69 | 12.40±0.62 | 0.90±0.26 | 70.64±1.40 | 1.21±0.18 |

| GP Biscuits | 6.13±0.28 | 11.27±0.72 | 14.20±0.30 | 5.83±1.59 | 60.65±0.43 | 1.91±0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).