1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) found its place in the industry as a promising technology that allows for the prototyping and production of three-dimensional parts [

1,

2,

3]. Compared to conventional methods, the advantages of this manufacturing technique include the design freedom that it offers, a reduction in the price of prototype models, and a significant minimization in the time needed from design to production of the real models [

4]. Furthermore, AM enables the reduction of material wastage, especially when objects with complex shapes are built. The above-mentioned features caused AM to be successfully introduced and commonly used in many advanced branches of industry such as automotive, aerospace, defence, bioengineering, medicine, sports, and civil engineering [

3]. One of the most popular groups of AM techniques includes Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) and Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) methods [

5,

6], sometimes named interchangeably. Both of them are based on the extrusion of the thermoplastic materials through the nozzle onto the base plate [

7]. They allow for the manufacturing of objects made from various types of thermoplastic polymers characterized by different mechanical and physical properties. Moreover, currently, they enable building parts made from composite materials where continuous or cut fibres (carbon, aramid, Kevlar) are used to improve mechanical strength [

8,

9,

10]. This group of 3D printing techniques is well-known and commonly used [

6].

Despite many advantages, such as low cost of manufacturing, a wide variety of 3D printers with diverse technological capabilities [

11], and a broad range of filament materials with different physical and mechanical properties, the FFF/FDM technique also has some drawbacks [

12]. One of them is the limited mechanical strength resulting from the specific layer-by-layer building method which is highlighted in many research papers [

12,

13,

14,

15]. To improve the mechanical integrity of fabricated structural components, an approach that utilizes full in-fill is often adopted [

16]. In this technique, material is deposited in consecutive layers along adjacent parallel paths. To counteract the inherent anisotropic mechanical characteristics of the fabricated object, it is common to vary the orientation of these layers. A widely adopted strategy for adjusting the orientation of successive layers is to set them at a 45-degree angle relative to each other. This orientation adjustment aims to optimize the mechanical properties across different directions and enhance the overall robustness of the component. This 3D printing technique aims to achieve isotropic mechanical properties for an object when it is subjected to external loading, such as compression or tension, in the XY plane relative to the object’s fabrication direction along the Z-axis. By carefully aligning the deposition of material in varying orientations, the method seeks to balance mechanical properties across different axes, thereby enhancing the object’s overall mechanical integrity and performance under applied loads in the specified plane.

Nevertheless, changing the layer fill angle can adversely affect the surface roughness of components produced using Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) 3D printing technology. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the optimal layer fill angle that strikes a balance between the high surface quality of the produced parts and their mechanical strength.

Due to this reason to find a compromise between satisfying surface roughness and high mechanical properties various types of model fillings are used.

Furthermore, the mechanical properties provided by the filament producers are often limited to specific 3D printing conditions. These problems attract the attention of many researchers. Khosravani et al. [

17] studied the influence of raster layup and printing speed on the mechanical strength of material samples made from Polylactic Acid (PLA). They found that mechanical properties like stiffness and strength strongly depend on the raster angle. The highest and the lowest strengths were obtained for 0° and 90° raster angles. A similar problem was undertaken by Qayyum et al. [

18] where authors focused their attention on the relationship between the raster angles as well as infill patterns on in-plane and edgewise flexural properties of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) material. Based on the results of experimental studies they stated that the raster angle strongly determined the mechanical behaviour of material fabricated via 3D printing. The value of flexural strength registered for samples where the raster angle was 0° was approximately twice higher in comparison to results gathered for samples where the raster angle was 90°. Furthermore, the Authors withdraw the conclusion that materials manufactured additively via the FFF technique indicate a strong anisotropy, due to this reason they recommend further studies in this research area [

18]. Similar conclusions were formulated in the following works [

7,

19,

20]

Based on the conducted literature review, it was found that the research conducted by scientists on the influence of the infill angle of individual material layers has a limited scope [

21]. Most often, they are limited to one type of material and an infill angle range of 0, 45, 90 degrees. Moreover, the literature contains results of mechanical properties research mainly related to tensile strength tests. To supplement the knowledge in this area, the authors of the paper decided to expand the scope of the conducted material tests, including additional infill variants in the tests (15°/-75°, 30°/-60°, 45°/-45°, and 0°/90°). Additionally, the tests were carried out for two standard materials, PLA and ABS, commonly used in FFF additive manufacturing techniques, and an additional material variant, Mediflex, characterized by a very large range of plastic deformation. The assessment of mechanical properties was conducted not only based on static tensile testing but also included impact testing.

2. Materials and Methods

Three types of thermoplastic materials commonly used in FFF 3D printing technique were selected for experimental research. Among the wide range of available options, PLA, ABS, and Mediflex were chosen. PLA is one of the most frequently chosen materials due to its high technological versatility, low impact of thermal shrinkage on the deformation of produced objects, low cost, and wide range of available variants. On the other hand, ABS is characterized by higher mechanical strength and greater resistance to dynamic loading than PLA. Unfortunately, it is prone to thermal shrinkage and requires stable temperature during the 3D printing process.

Mediflex is purported to serve as a material bridging the gap between brittle and ductile materials. Mediflex blends seamlessly with ABS, allowing for the creation of composite materials. It indicates a thermal resistance up to 120°C. The filament is slightly harder than typical flexible materials, with a hardness of approximately 96-98 Shore A. Consequently, the authors selected materials listed in

Table 1, along with their respective properties, for comprehensive evaluation and comparison.

The FFF 3D printing process was carried out using a Prusa MK3S+ 3D printer (Prusa Research a.s., Prague, Czech Republic) for all materials enumerated in

Table 1. This printer features a single-nozzle printing head equipped with a direct feeding mechanism, specifically designed for handling flexible materials like Mediflex. The materials utilized for this 3D printer are supplied in a filament form with a diameter of 1.75 mm and wound onto a spool. Throughout the printing procedure, the material is extruded through the nozzle onto a heated build plate. The build plate is constructed with a magnetic steel textured bedplate, complemented by a Polyetherimide (PEI) surface to facilitate adhesion and fixation of the samples. The nozzle assembly moves along the 0ZX axes, while the build plate traverses along the 0Y axis, ensuring precise layer deposition and uniform build quality.

Initially, technological tests were conducted to determine the optimal 3D printing parameters for the selected filaments using a Prusa i3 Mk3S+ 3D printer. The results of these tests led to the identification of 3D printing parameters listed in

Table 2. The specified parameters deviate slightly from the manufacturers’ recommended settings for each filament type.

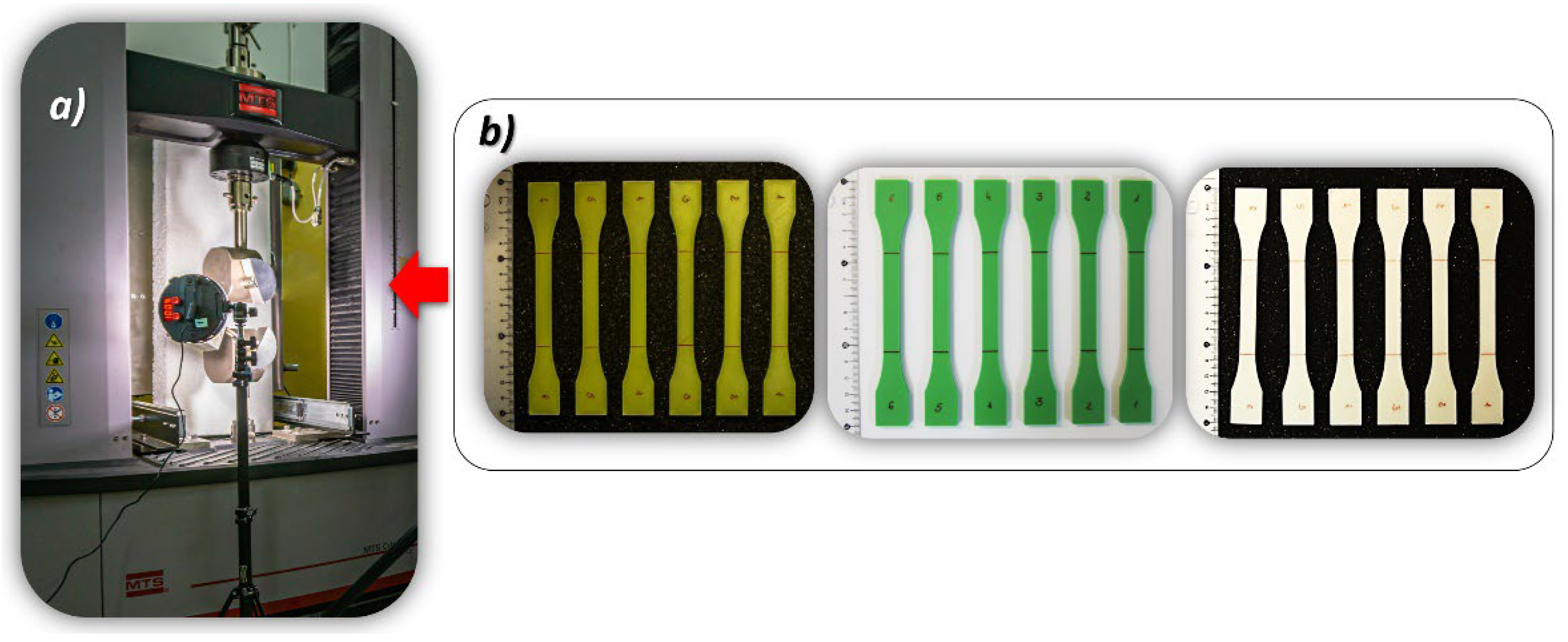

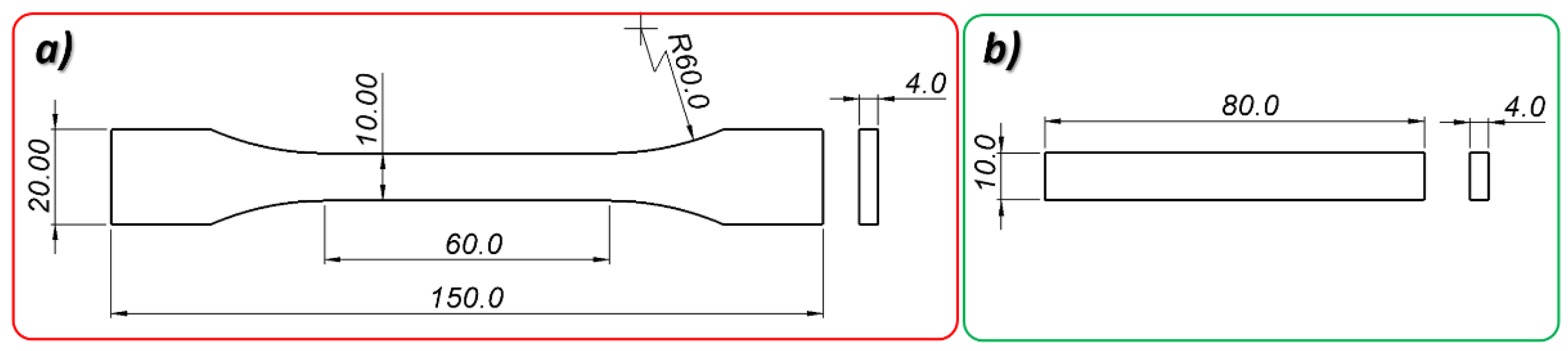

Subsequently, material samples were fabricated for mechanical property testing. The authors proposed an assessment of mechanical properties based on the results of static tensile tests and impact resistance tests. The study employed solid material samples with dimensions and shapes conforming to ISO 527-1 and ISO 179-1 standards (

Figure 1).

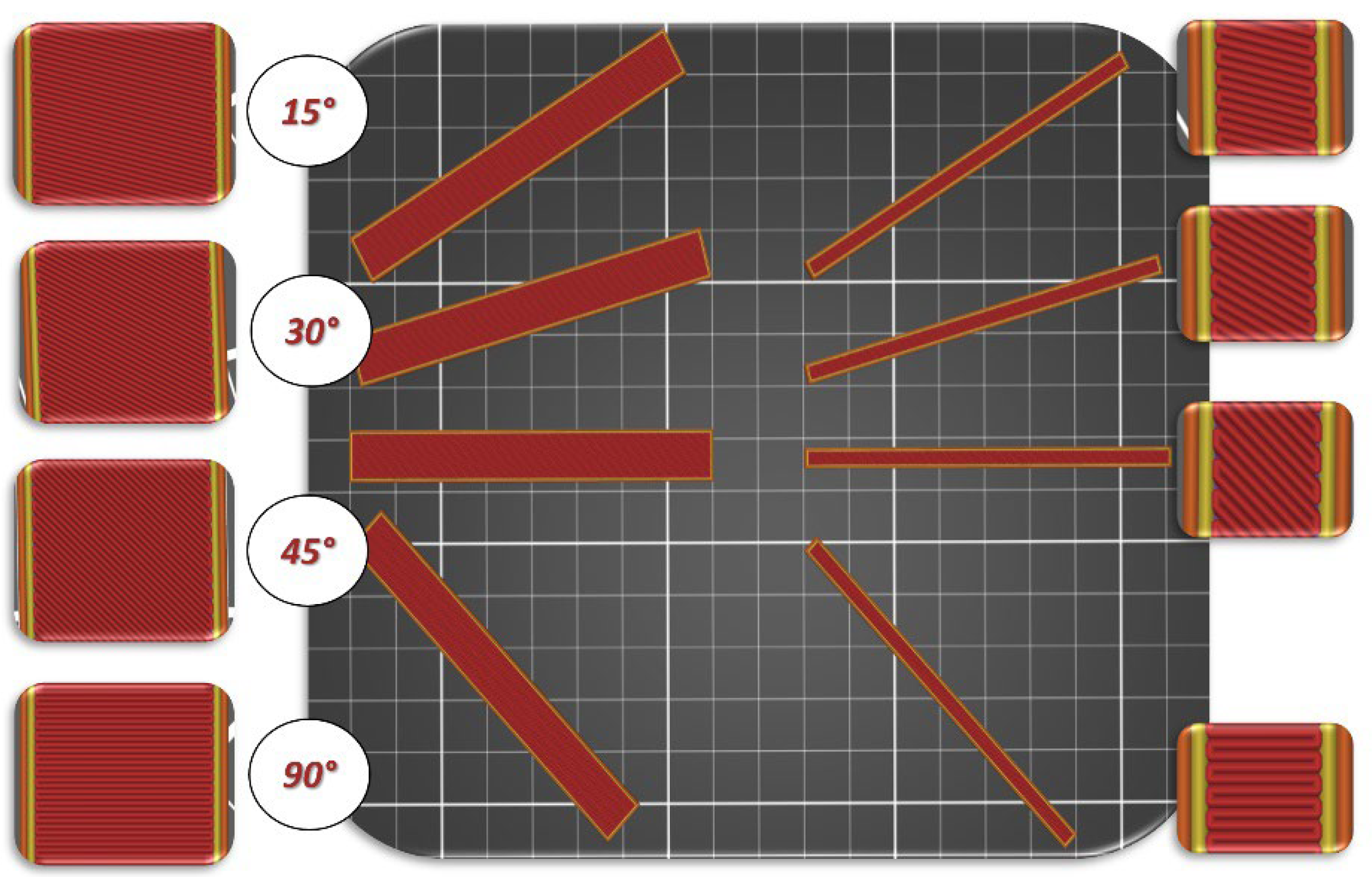

1To evaluate the influence of infill angle on the samples, it was decided to produce them using the following angular infill patterns: 15°/-75°, 30°/-60°, 45°/-45°, and 0°/90°, designated hereafter in the article as respectively: 15°, 30°, 45°, and 90°. Additionally, impact resistance test samples were fabricated considering two manufacturing orientations: horizontally and vertically, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The tensile mechanical properties of the polymer materials were evaluated using an MTS Criterion 45.105 testing machine, following the ISO 527-1 standard for uniaxial tensile testing. Tensile specimens, as depicted in

Figure 1a, were subjected to a strain rate of 0.01 s

-1. Throughout the tensile testing procedure, the TW-Elite software was employed to monitor and record the entire process. Additionally, a high-resolution camera was utilized to capture the tension behaviour of the specimens.

Experimental data were acquired at a sampling frequency of 50 Hz, enabling the generation of precise stress-strain curves. These tests were conducted to ascertain and compare the mechanical strength properties and failure mechanisms of samples fabricated with different variants of material infill.

Figure 3.

The main view of the laboratory stand used to perform quasi-static tensile tests: a) – MTS Criterion 45.105 strength machine with additional lightening system, b) dog-bone specimens made from PLA PolyMax, ABS+ and Mediflex filaments.

Figure 3.

The main view of the laboratory stand used to perform quasi-static tensile tests: a) – MTS Criterion 45.105 strength machine with additional lightening system, b) dog-bone specimens made from PLA PolyMax, ABS+ and Mediflex filaments.

Impact tests were carried out using the Zwick/Roell Amsler HIT2000F drop tower following the ISO 179-1 standard. The tests were executed under ambient room temperature conditions, with a striker mass 9.336 kg and speed precisely set to 2.9 mm/s at the point of impact. Prior research by Graupner et al. [

22] delved into the intricacies of specimen geometry, specifically exploring the impact of notches on sample behaviour. Their findings highlighted a nuanced sensitivity to notches, varying based on the angle of the notch and the absence or presence of notches altogether. Furthermore, the layered nature inherent in the manufacturing process can introduce geometric distortions to notches, potentially affecting test outcomes. In light of these considerations, this study employed unnotched specimens with dimensions of 80 x 10 x 4 mm (as illustrated in

Figure 1b), oriented for edgewise impact. The selected test conditions were tailored to account for the unique wall structure of the specimen relative to its infill pattern, recognizing the potential impact of these design intricacies on test results.

The mechanical characteristics of various sample configurations were evaluated through rigorous testing procedures, encompassing three distinct material types. A comprehensive total of 72 tensile tests and 144 impact tests were conducted to ascertain these properties.

3. Results

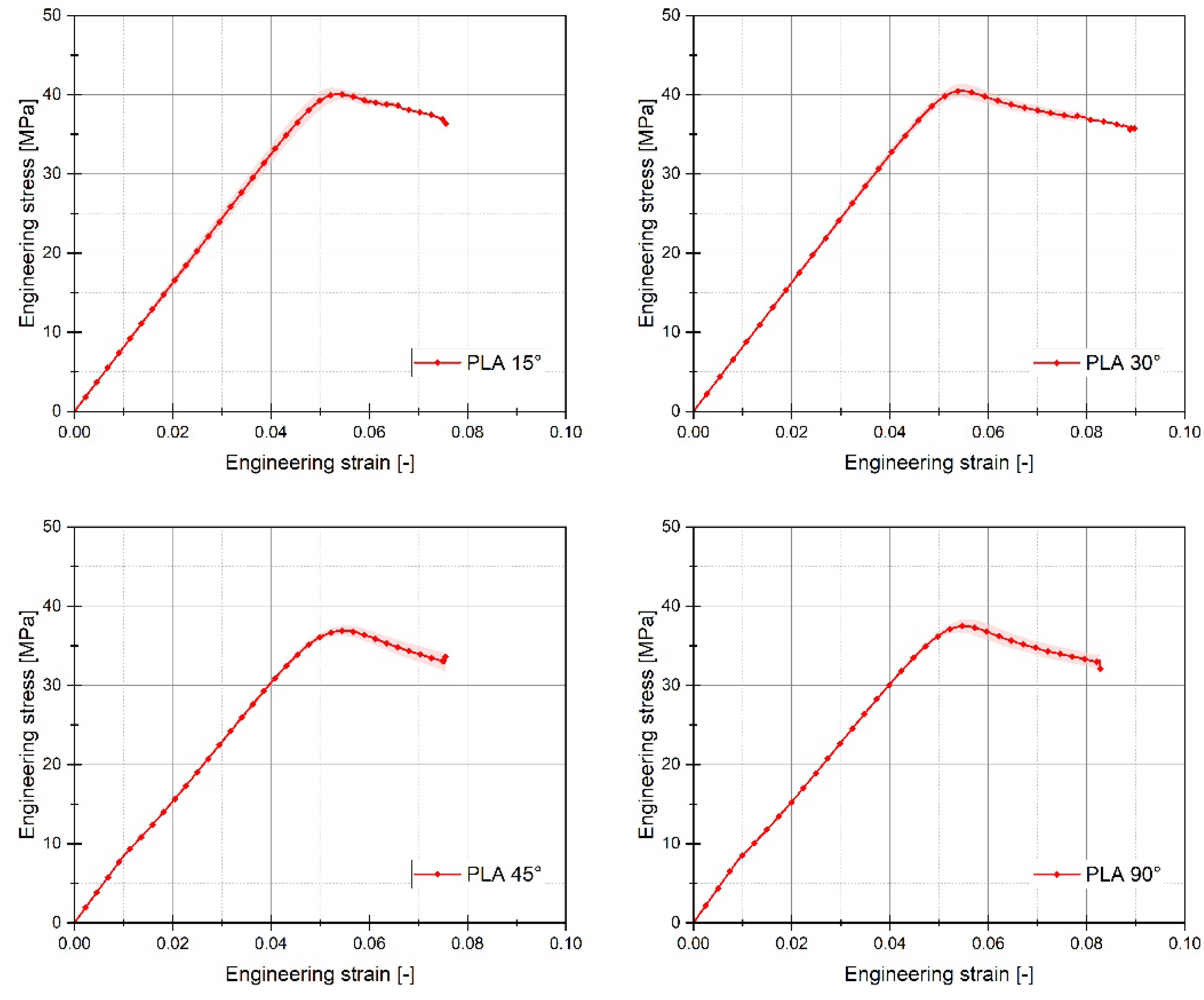

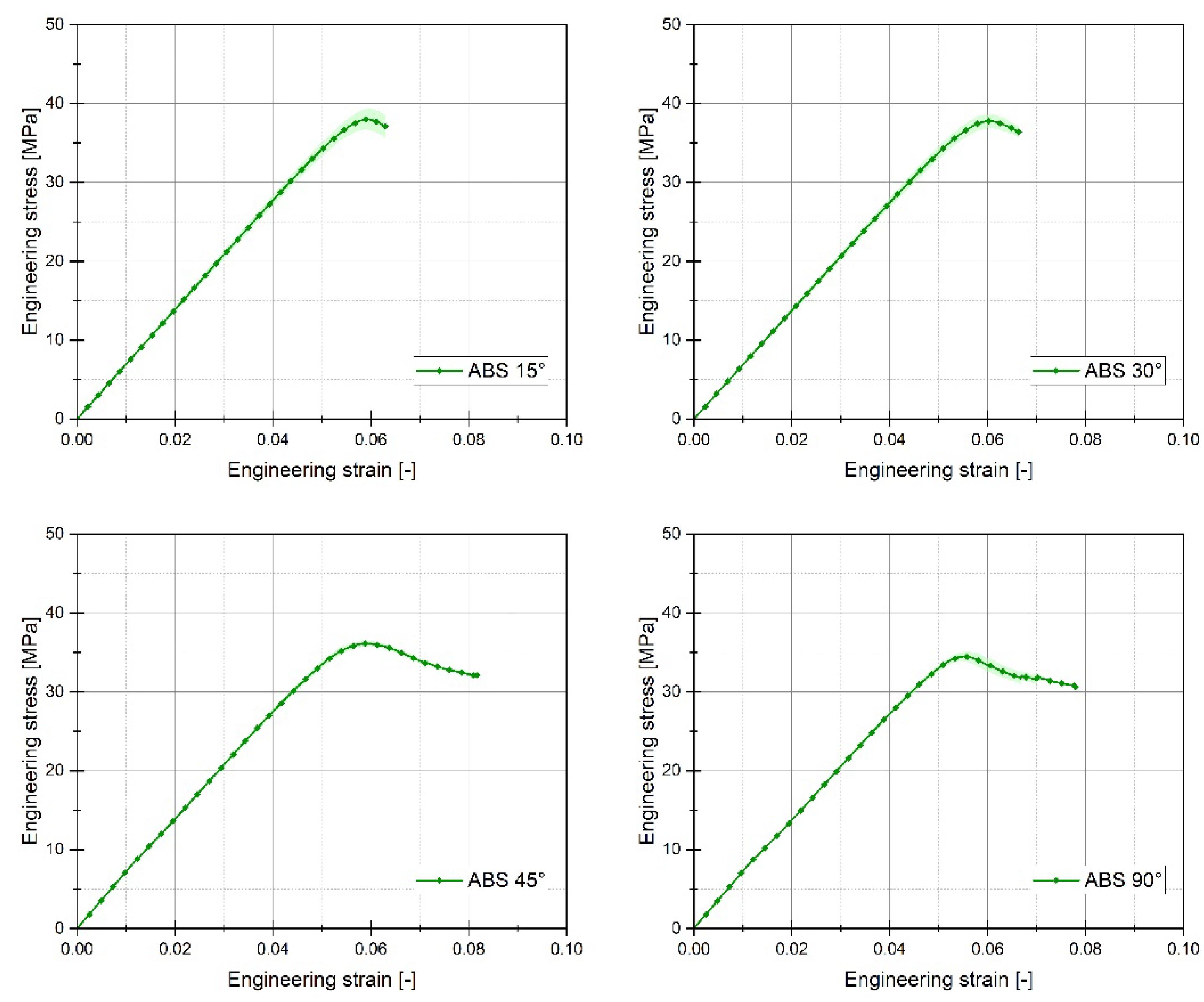

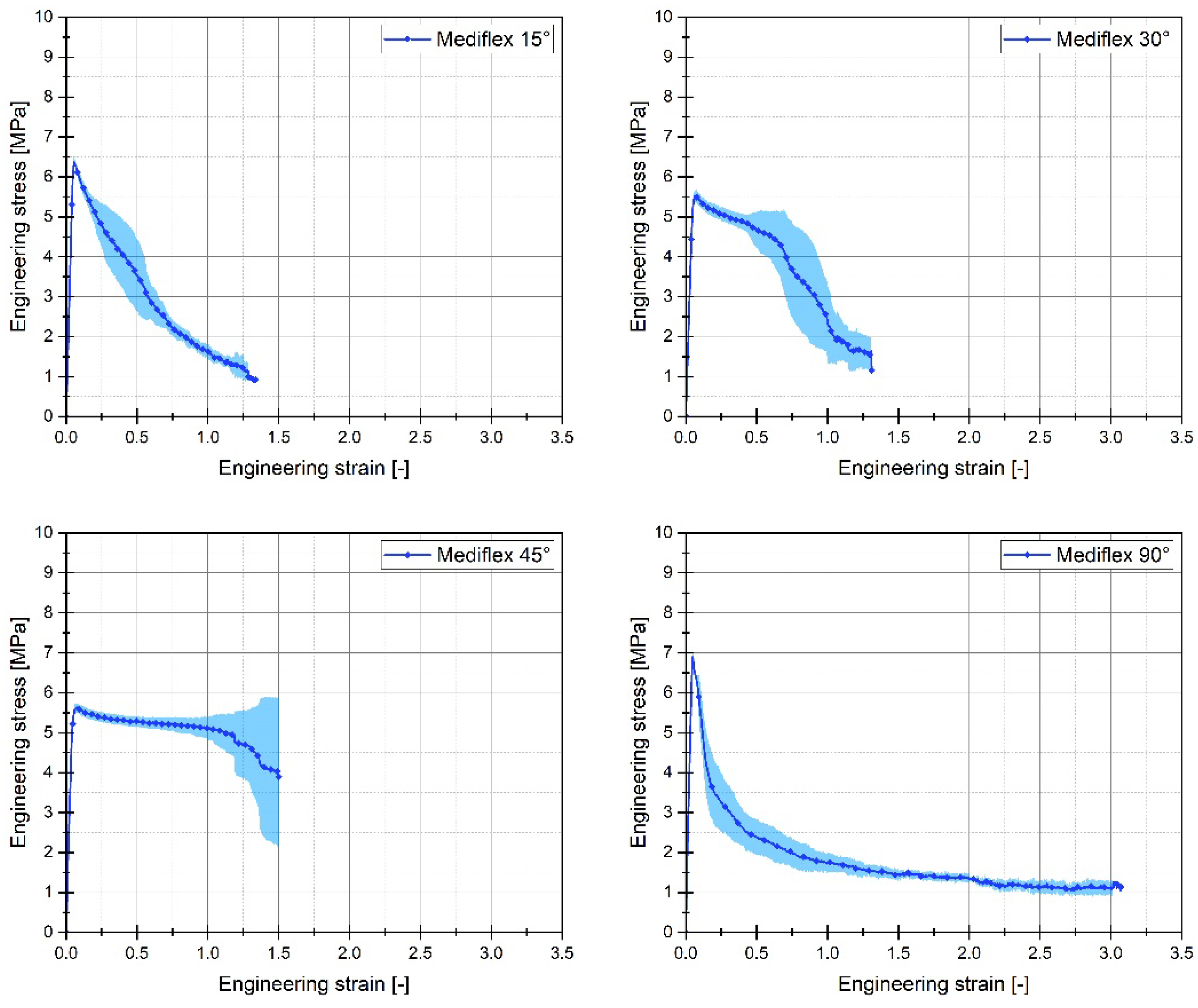

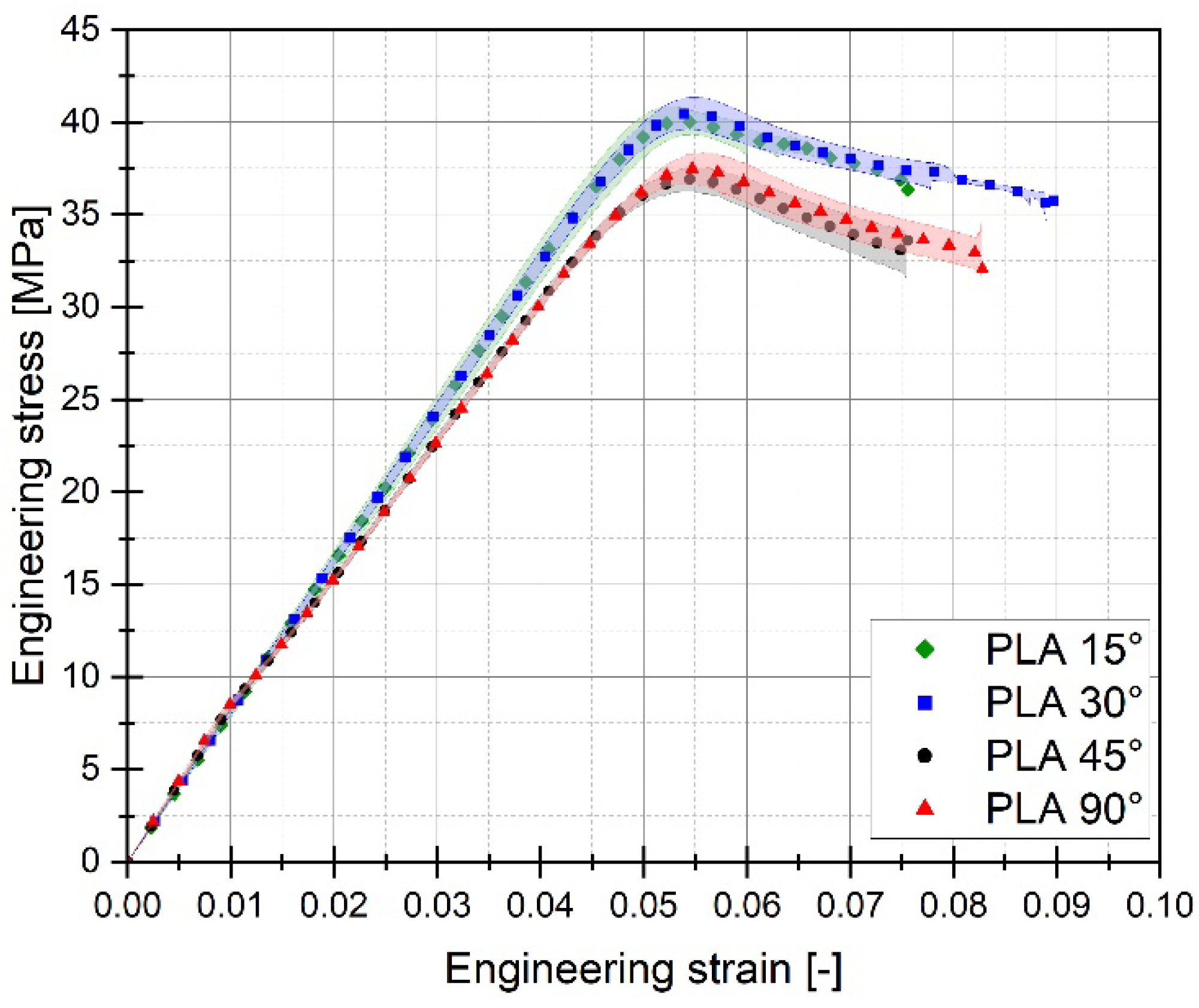

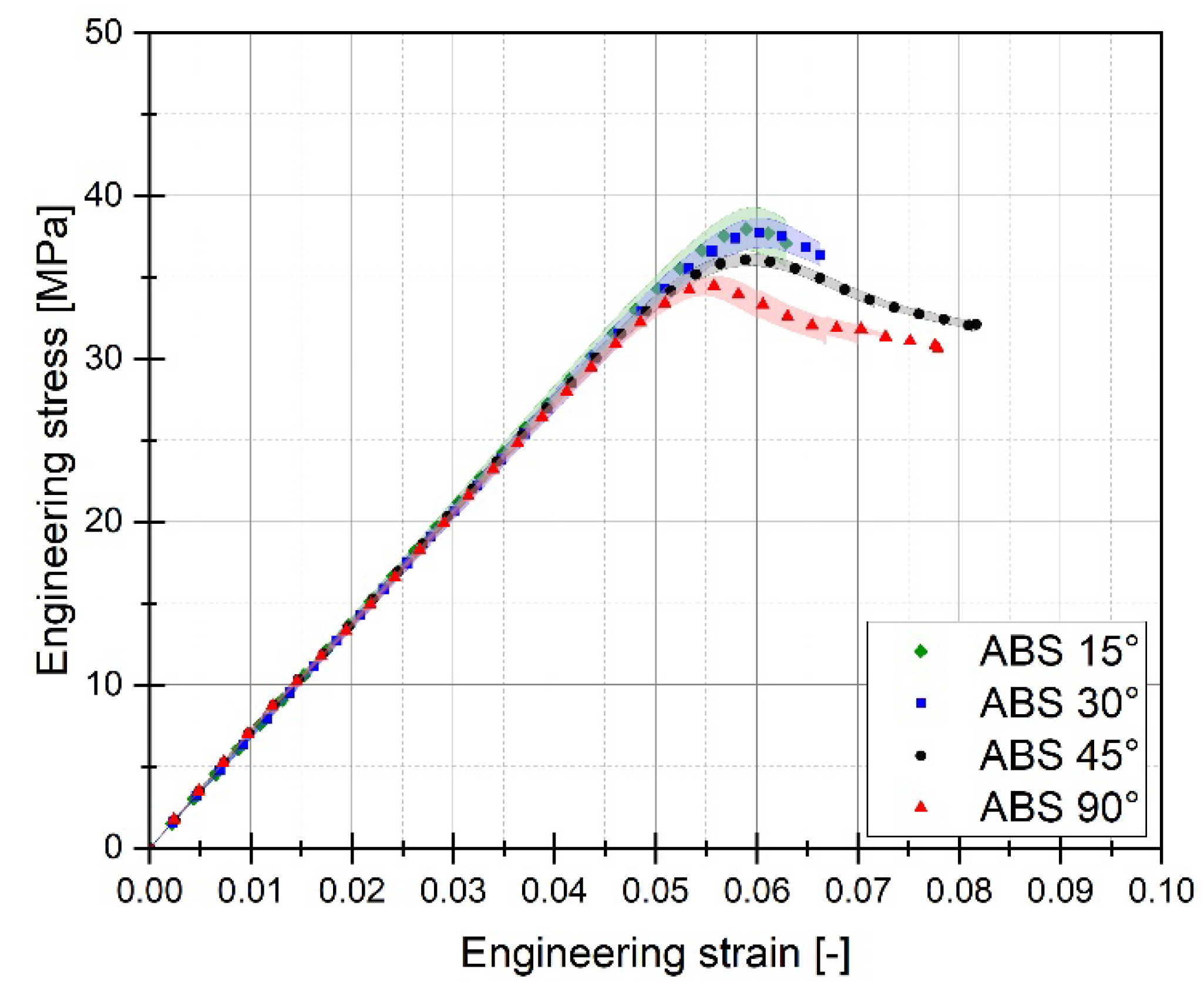

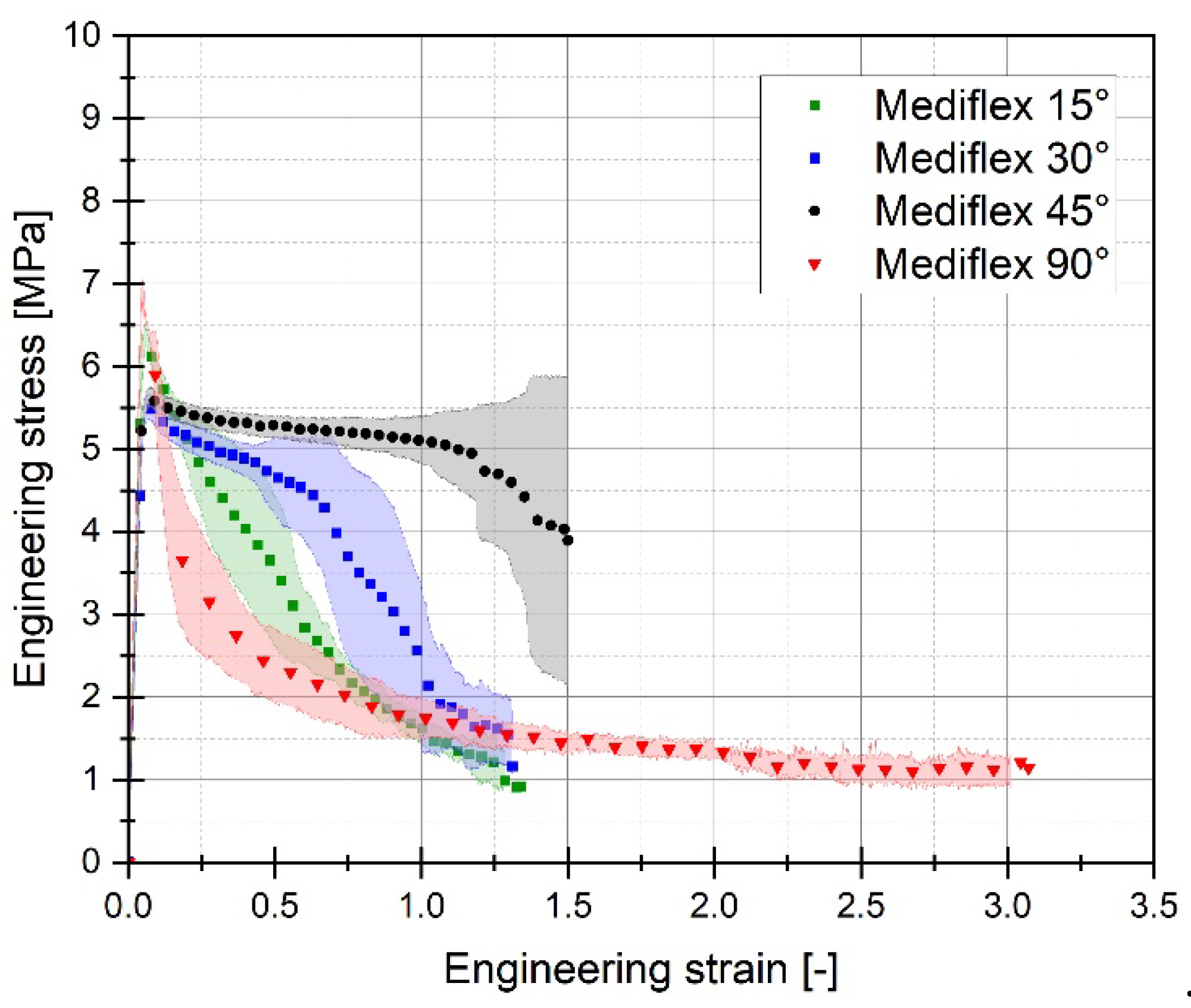

For each of the considered sample filling variants, the quasi-static tensile tests were conducted six times. The graphs below (

Figure 4÷6) present the averaged stress-strain curves along with the standard deviation. They were used to estimate the mechanical properties like Young’s Modulus, as well as tensile strength and maximum plastic strain which are presented in

Table 3. Furthermore, to enable a more precise comparison of the curves obtained for the individual variants of the conducted experimental studies, additional cumulative graphs were developed, as shown in the figures. (

Figure 7÷9).

Figure 4.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed PLA PolyMax filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 4.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed PLA PolyMax filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 5.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 5.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 6.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 6.

Stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 7.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed PLA PolyMax filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 7.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed PLA PolyMax filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Analyzing the stress-strain curves obtained from tensile tests for various infill angles of PolyMax PLA material, one can observe a consistent reproducibility of the curves and a small standard deviation relative to the mean values. The samples with infill angles of 15 and 30 degrees exhibited the highest mechanical strength. The lowest strength was observed for the samples with a 45-degree infill angle. Similar conclusions can be drawn from the tensile test results for ABS Plus material. The maximum strength was achieved at infill angles of 15 and 30 degrees, while infill angles of 45 and 90 degrees resulted in the highest range of plastic deformation. A different deformation behaviour was observed for Mediflex material. The stress-strain curves for different proposed infill angles showed a significant variation in the range of plastic deformation. There was a noticeable standard deviation relative to the mean values, and the individual curves differed significantly in the range of plastic deformation achieved.

Figure 8.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 8.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 9.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 9.

Comparison of stress-strain plots registered for 3D printed Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Table 3.

Average experimental results of tensile tests accordingly manufactured horizontally.

Table 3.

Average experimental results of tensile tests accordingly manufactured horizontally.

| Material |

Raster

Angle |

E (MPa) |

σy (MPa) |

ef (-) |

| PLA PolyMax |

15° |

2021 |

40.34 ± 0.59 |

0.065 ± 0.006 |

| 30° |

2079 |

40.53 ± 0.88 |

0.083 ± 0.007 |

| 45° |

1867 |

36.40 ± 0.23 |

0.064 ± 0.007 |

| 90° |

1772 |

37.78 ± 0.34 |

0.034 ± 0.003 |

| ABS+ |

15° |

1558 |

38.02 ± 1.34 |

0.065 ± 0.002 |

| 30° |

1707 |

37.79 ± 0.87 |

0.072 ± 0.003 |

| 45° |

1869 |

41.39 ± 0.82 |

0.037 ± 0.009 |

| 90° |

1780 |

39.67 ± 1.59 |

0.029 ± 0.01 |

| Mediflex |

15° |

253 |

6.44 ± 0.08 |

1.19 ± 0.11 |

| 30° |

132 |

5.58 ± 0.15 |

1.32 ± 0.17 |

| 45° |

243 |

7.00 ± 0.39 |

2.52 ± 0.52* |

| 90° |

145 |

6.33 ± 0.12 |

2.68 ± 0.18* |

Based on the analysis of the data presented in

Table 3, it can be stated that for the material PLA, the highest value of mechanical strength was recorded for an infill angle of 30 degrees. Additionally, for this particular variant, the range of plastic deformation of the material was also the largest. Similar observations can be made when analysing the data concerning the ABS plus material. In this case, the highest mechanical strength was noted for the sample variant with an infill angle of 15 percent, which does not differ significantly from the case where the infill angle was 30 percent. However, for this material, a significantly lower range of plastic deformation can be observed. For ABS plus, the highest deformation value was recorded for the sample material variant with an infill angle of 40 degrees.

Analysing the data from the static tensile test for the Mediflex material, it can be observed that it belongs to a group of polymer materials characterised by a very large range of plastic deformation with low mechanical strength. For this material, the highest strength was determined for an infill angle of 45 degrees. However, for the infill angle variant of 90 degrees, the range of plastic deformation was twice as high as for the variant with the highest mechanical strength. Unfortunately, despite the considerable range of deformation, this material exhibits a low range of mechanical strength, which for the 45-degree angle variant is only 7 MPa.

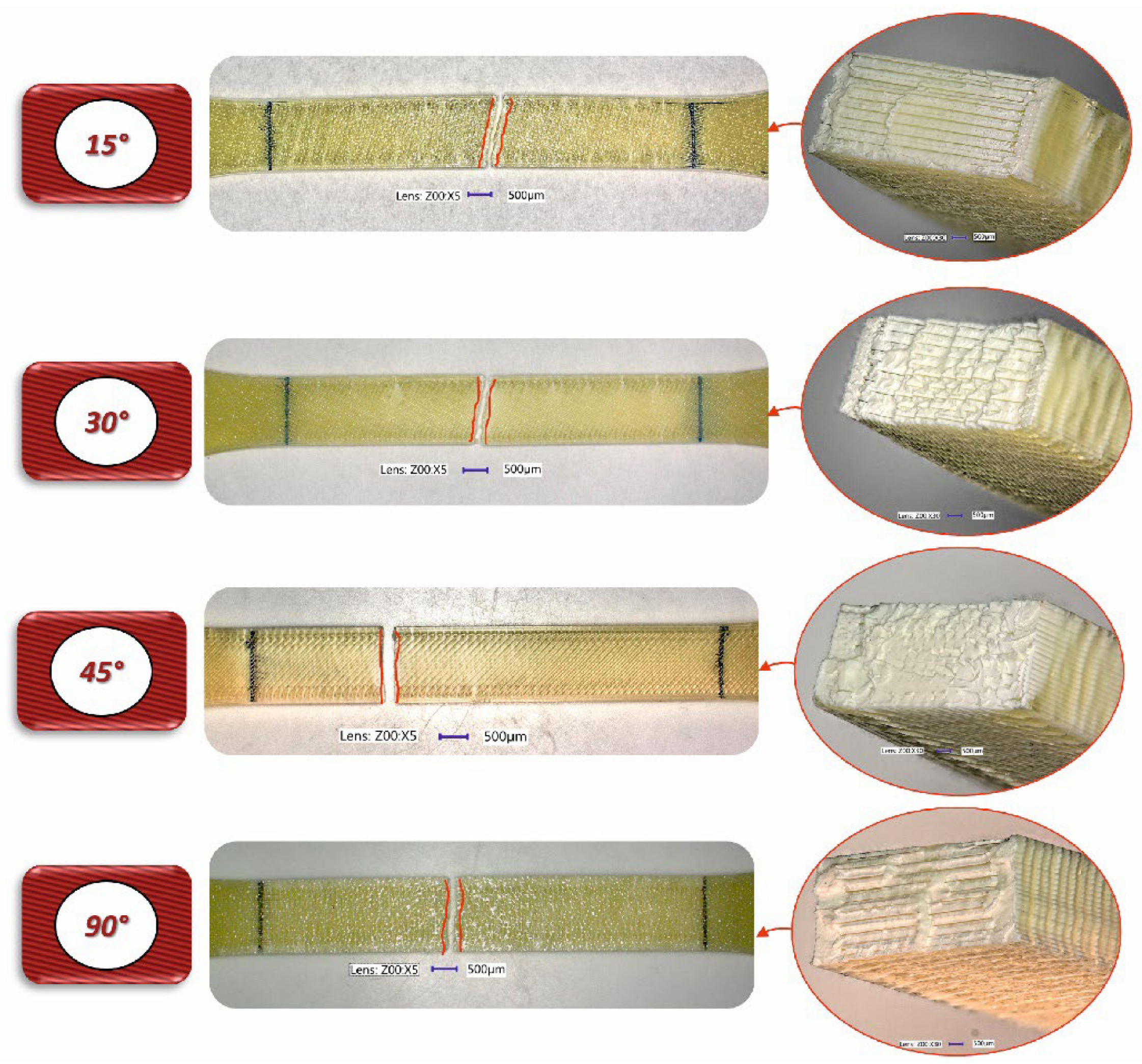

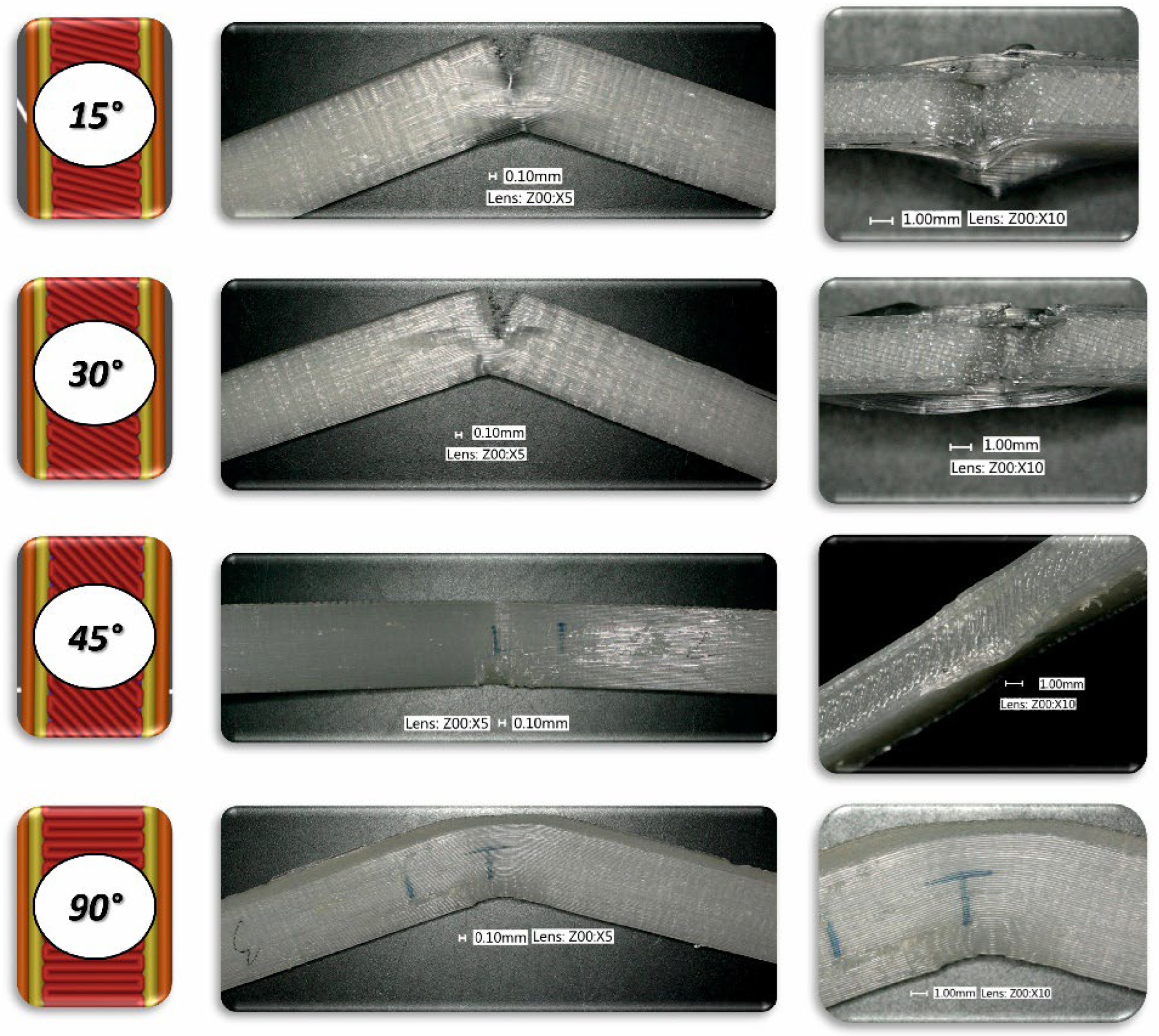

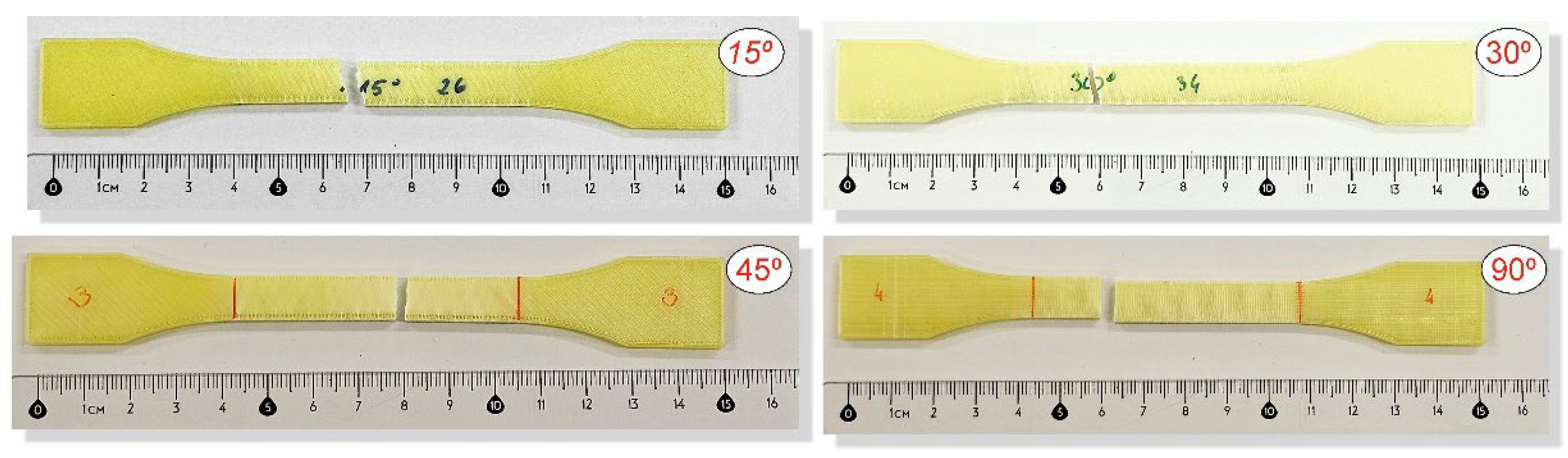

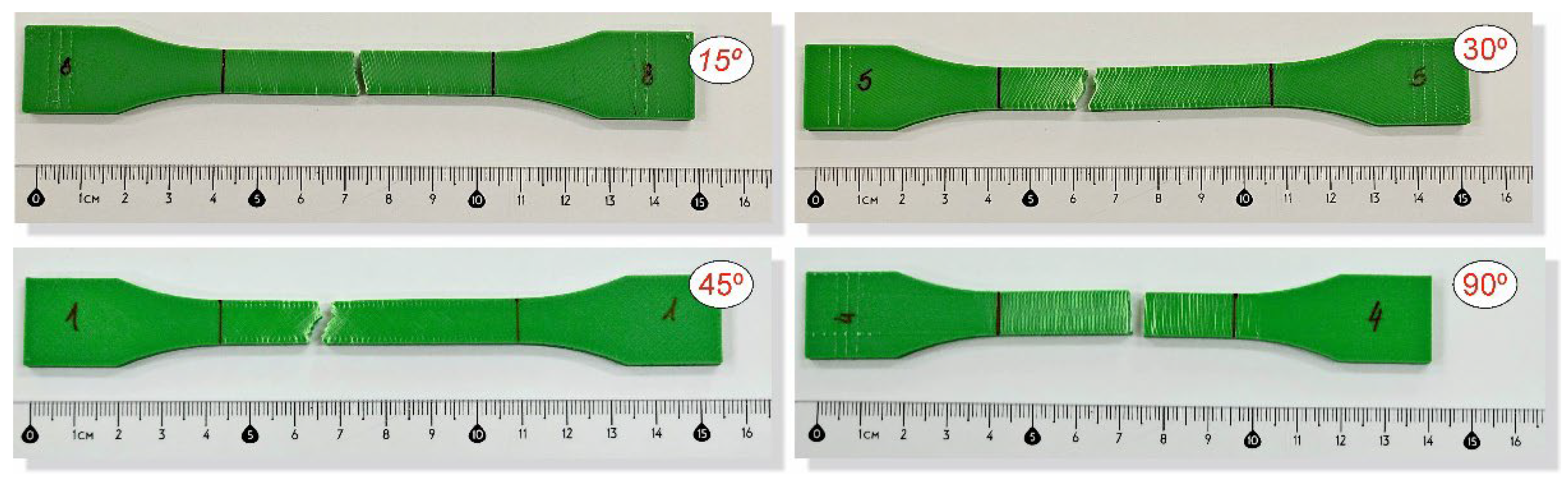

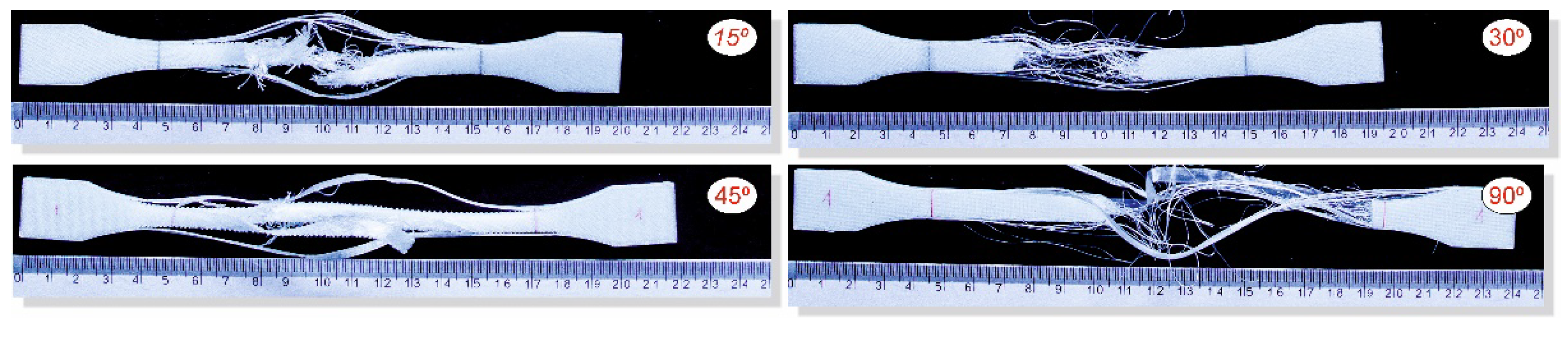

To analyse the impact of the infill angle of the material sample on its mechanical properties more precisely, a fractographic evaluation of the samples after testing was conducted.

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show images of the samples post-testing, taking into account the different infill angle variants. In the case of PLA material, no significant differences were observed in the fracture surface pattern of the material. For all cases analysed, it has a similar linear pattern (

Figure 10). The fracture surface pattern differs for samples made of ABS plus material. It can be observed that for the infill angle variants of 15 and 90 degrees, the fracture surface is relatively flat. For infill angles of 30 and 45 degrees, the fracture surface is significantly larger.

In the case of assessing the fracture characteristics of samples made from Mediflex material, it can be noted that this material exhibits properties similar to composite materials. After tensile testing, the sample was destroyed except for the side scraps. The failure mechanism pattern is similar to delamination.

Figure 13.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 13.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 14.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 14.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 15.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 15.

View of fracture surface of tensile specimen made form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

The next stage of evaluating the impact of infill angle on the mechanical strength of 3D-printed material samples was conducted using a Charpy impact testing setup. In the proposed study, the influence of the printing direction during the 3D printing process was also considered. The samples were oriented horizontally and placed on their side relative to the work table of the 3D printer.

The results of the dynamic non-instrumental Charpy test are presented in

Table 4 and Table 5 as well as in a graphical form in

Figure 16. A slight difference in impact strength properties, according to the raster angle and building orientation, particularly in maximum overload, is observed. PLA specimens printed horizontally exhibit a peak force approximately 25% higher than those printed vertically. Additionally, PLA samples printed horizontally with a raster angle of 45° demonstrate significantly higher impact strength compared to other PLA specimens. A similar trend is observed in Mediflex specimens printed both vertically and horizontally, where the maximum force and toughness are greater for 45° raster angles.

Table 4.

Toughness results of Charpy impact test for horizontally orientated samples:.

Table 4.

Toughness results of Charpy impact test for horizontally orientated samples:.

| Material |

Raster angle |

Fmax (N) |

acU (kJ/m^2) |

| PLA PolyMax |

90° |

550.41 ± 18.69 |

22.62 ± 1.80 |

| 15° |

637.95 ± 31.24 |

30.91 ± 1.91 |

| 30° |

587.35 ± 23.86 |

23.33 ± 2.31 |

| 45° |

583.01 ± 42.03 |

40.74 ± 7.47 |

| ABS+ |

0° |

561.13 ± 11.91 |

25.10 ± 2.54 |

| 15° |

447.16 ± 6.41 |

17.70 ± 1.17 |

| 30° |

440.93 ± 12.84 |

17.45 ± 1.21 |

| 45° |

534.21 ± 11.61 |

30.48 ± 2.94 |

| Mediflex |

0° |

125.86 ± 5.24 |

19.44 ± 2.00 |

| 15° |

81.66 ± 3.64 |

37.54 ± 7.14 |

| 30° |

92.79 ± 5.52 |

25.93 ± 2.78 |

| 45° |

111.59 ± 2.87 |

48.56 ± 2.44 |

Table 3.

Toughness results of Charpy impact test for vertically orientated samples:.

Table 3.

Toughness results of Charpy impact test for vertically orientated samples:.

| Material |

Raster angle |

Fmax (N) |

acU (kJ/m^2) |

| PLA PolyMax |

90° |

434.10 ± 36.58 |

20.59 ± 4.06 |

| 15° |

689.73 ± 32.57 |

45.24 ± 5.08 |

| 30° |

448.92 ± 22.67 |

24.66 ± 3.47 |

| 45° |

518.68 ± 31.93 |

29.59 ± 0.96 |

| ABS+ |

0° |

553.78 ± 72.56 |

19.46 ± 4.53 |

| 15° |

505.60 ± 8.67 |

26.40 ± 3.21 |

| 30° |

519.22 ± 11.28 |

25.58 ± 2.22 |

| 45° |

598.37 ± 65.85 |

31.92 ± 7.24 |

| Mediflex |

0° |

161.51 ± 1.20 |

79.49 ± 4.77 |

| 15° |

91.66 ± 2.79 |

37.54 ± 2.00 |

| 30° |

95.55 ± 2.72 |

25.93 ± 4.72 |

| 45° |

154.70 ± 6.04 |

84.01 ± 0.90 |

Figure 16.

Comparison of Charpy tests results obtained for samples with different angle raster orientation (15°, 30°, 45° and 90°) and 3D printing direction (horizontal and vertical).

Figure 16.

Comparison of Charpy tests results obtained for samples with different angle raster orientation (15°, 30°, 45° and 90°) and 3D printing direction (horizontal and vertical).

To conduct a thorough analysis of the effect of infill angle on the mechanical strength of additively manufactured samples under impact loading conditions, an additional fractographic assessment of the fracture surfaces of the samples after testing was performed. Using an digital microscope Keyence VHX-6000, a series of photographs was taken for each of the considered infill variants, which were subsequently analysed (

Figure 17÷22). The conclusions drawn from the fractographic assessment will be discussed in detail in the next chapter of the work. Nonetheless, it can be stated that the infill angle of the material sample has a significant impact on the obtained impact resistance test results.

Figure 17.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 17.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 18.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 18.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form PLA filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 19.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 19.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 20.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 20.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form ABS Plus filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 21.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 21.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made horizontally form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 22.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.

Figure 22.

View of fracture surface of Charpy test specimen made vertically form Mediflex filament with consideration different raster angle: 15°, 30°, 45° and 90°.