Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

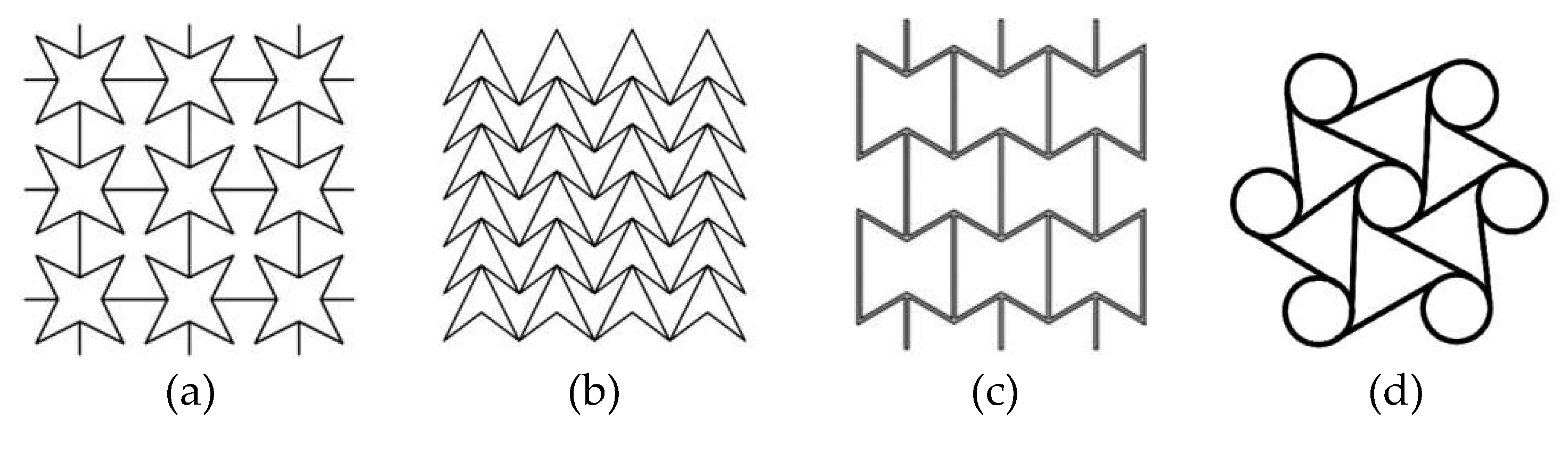

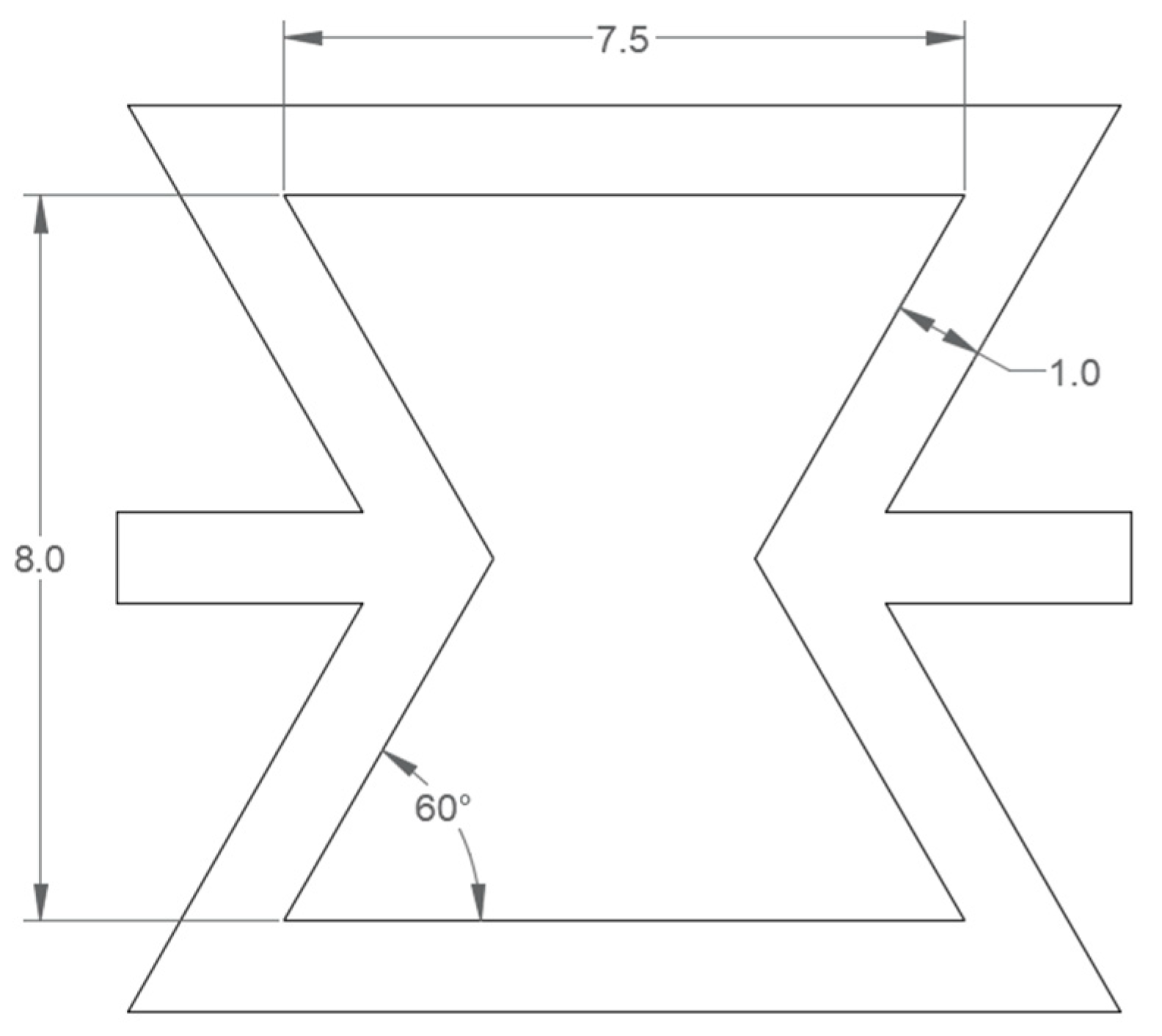

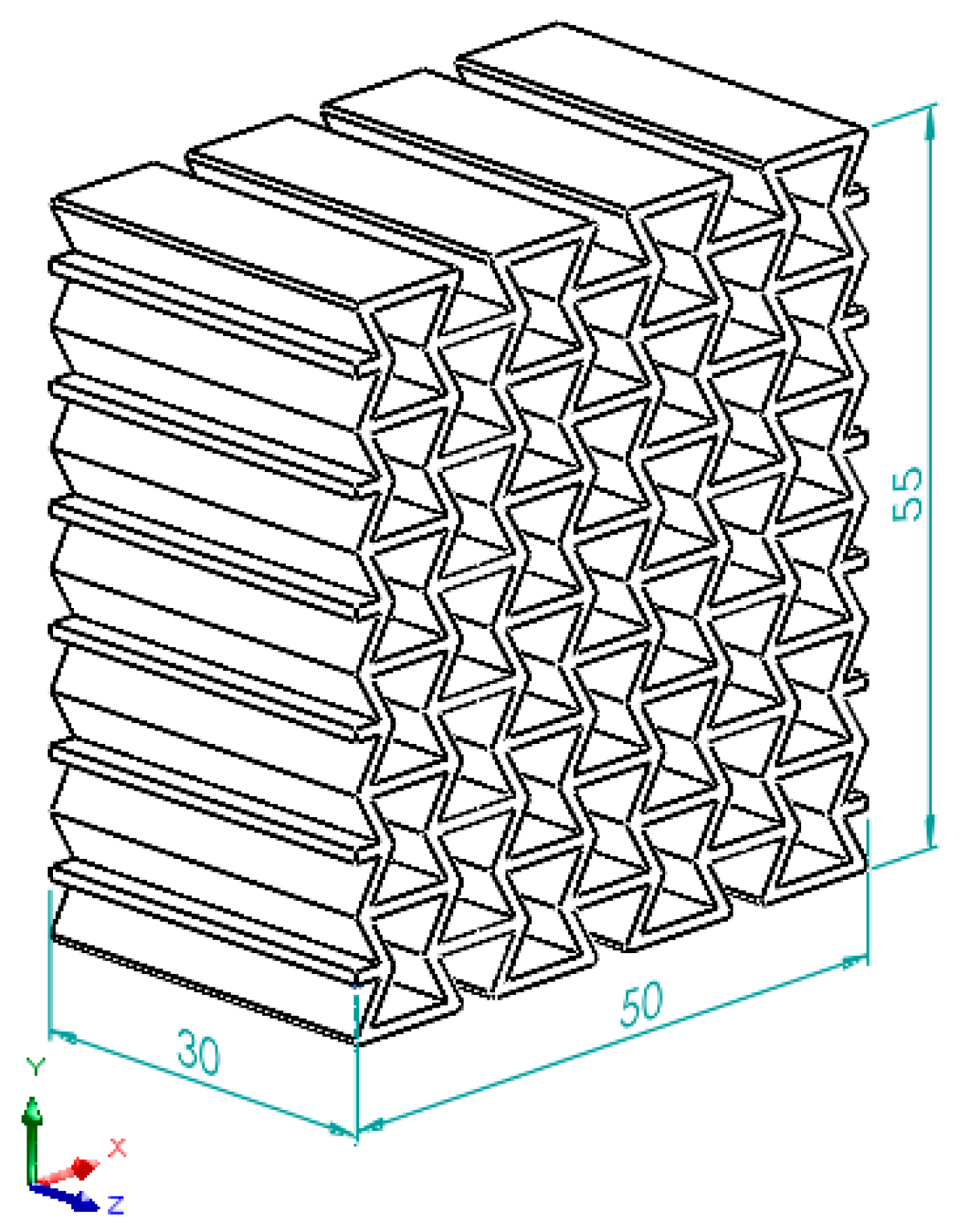

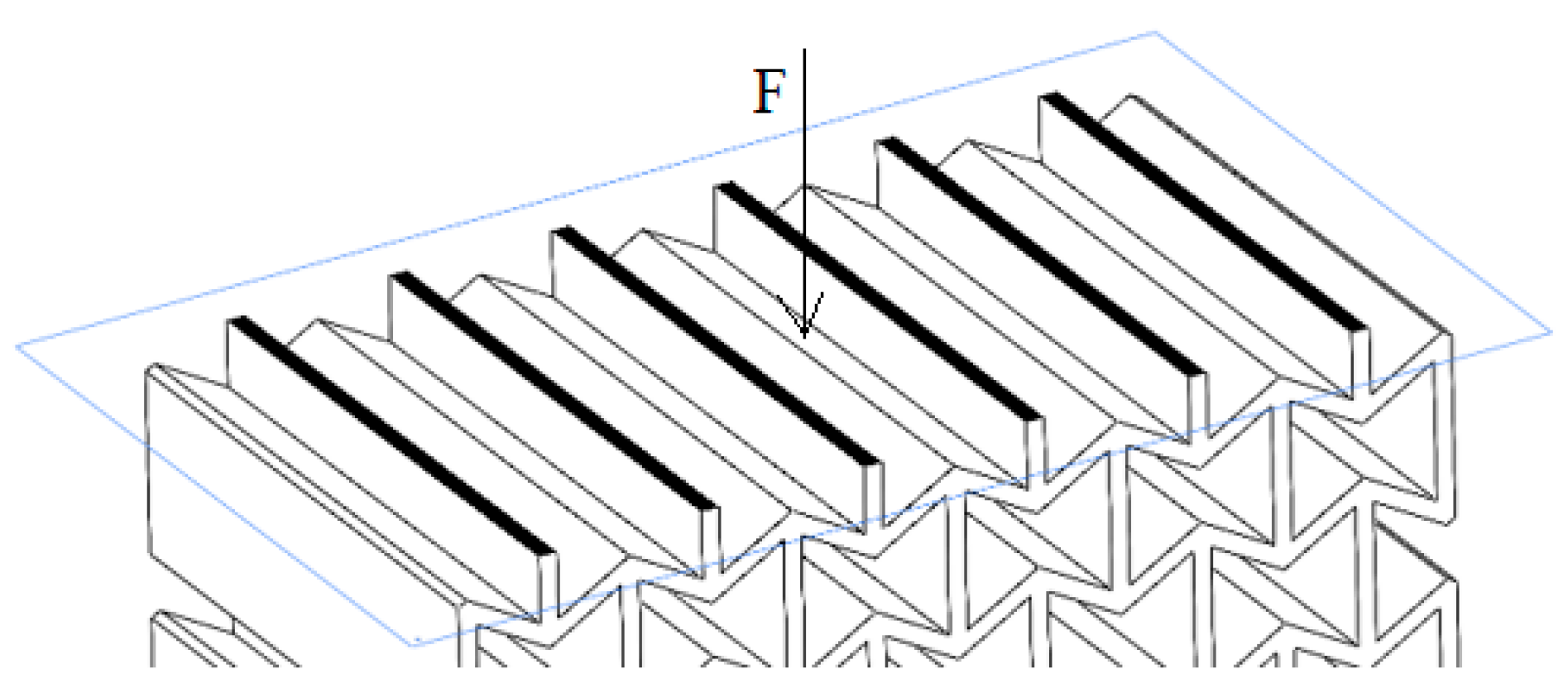

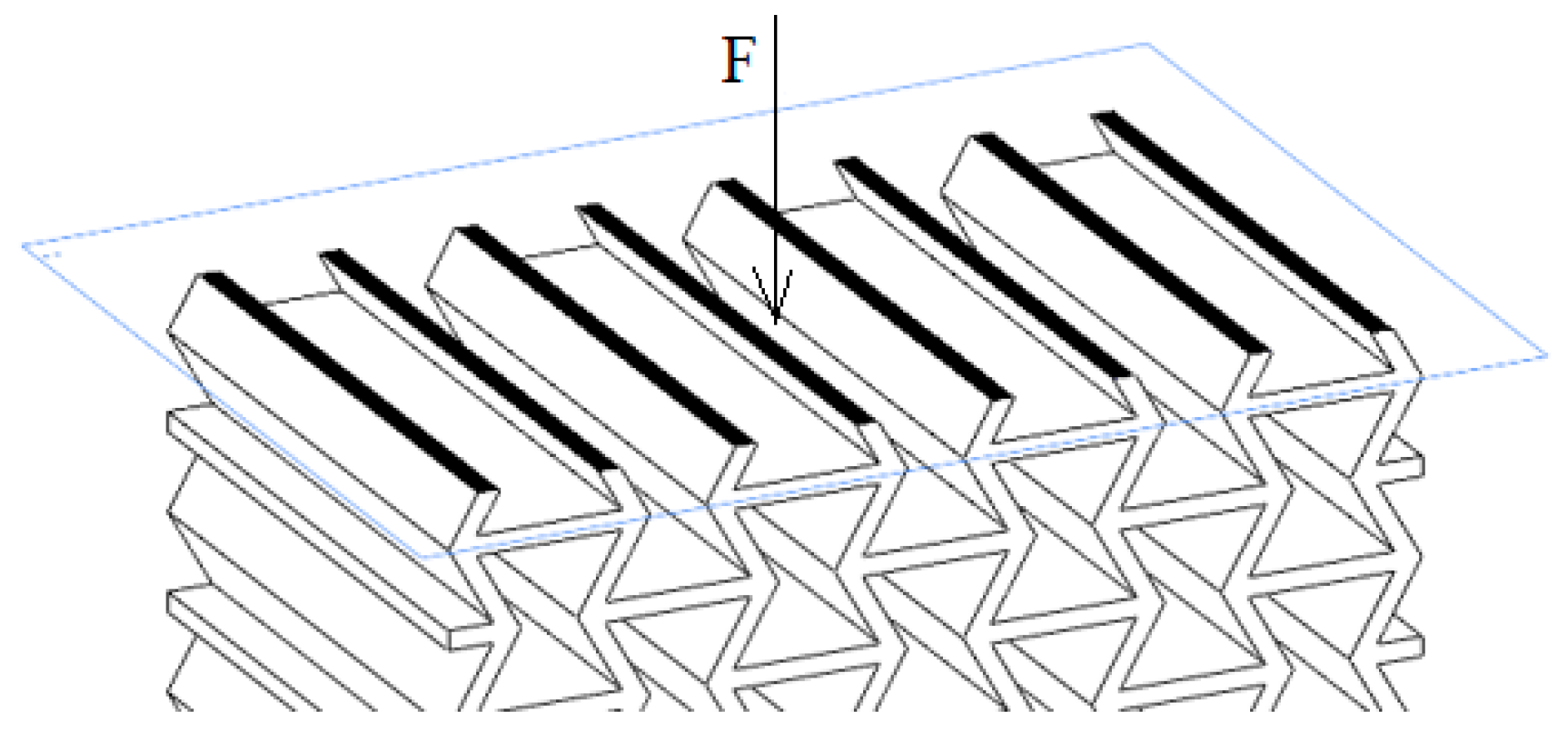

2.1. Geometry Preparation and Building Orientations

2.2 .3D Printing Apparatus and Materials

2.3. Test Equipment and Method

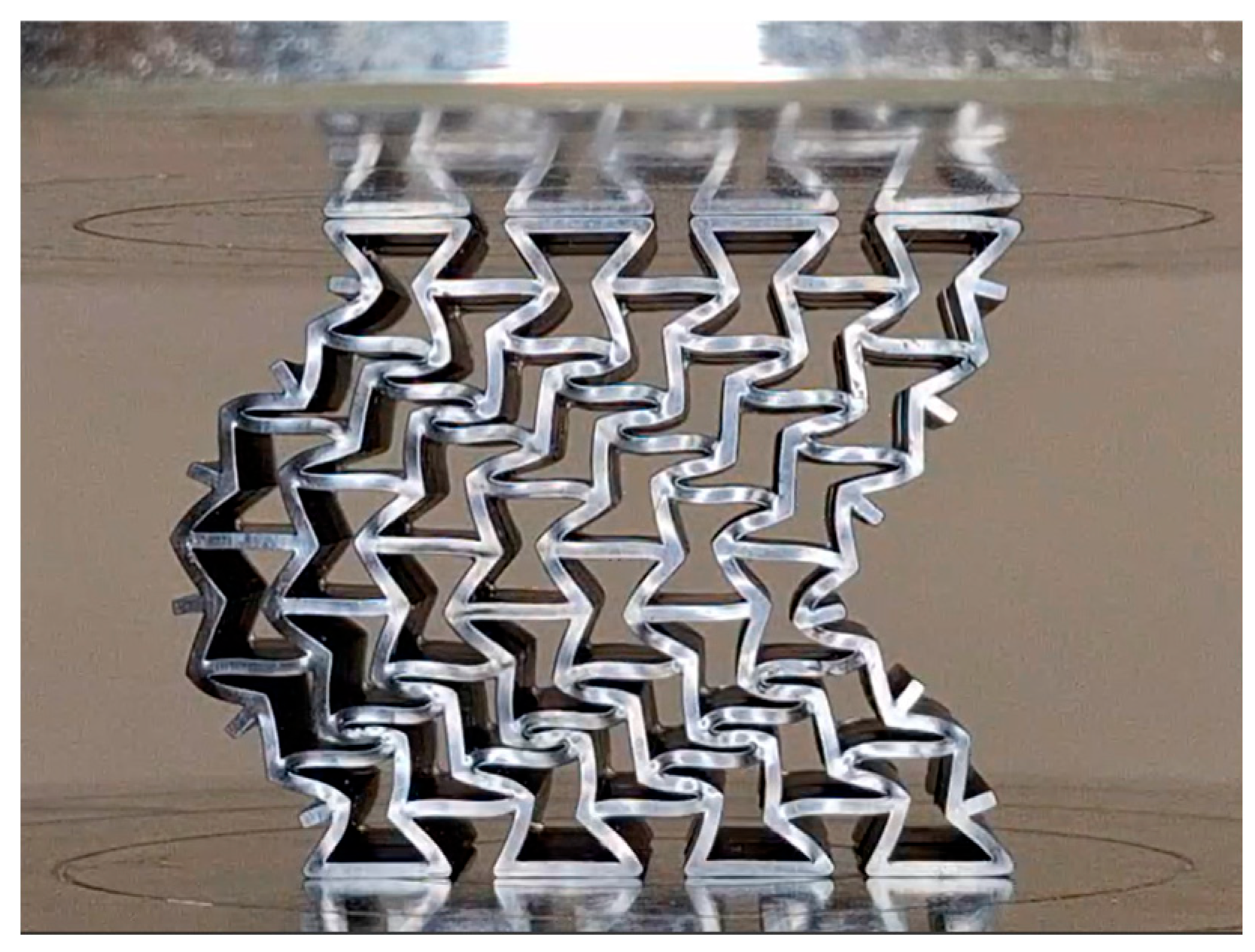

3. Results and Discussion

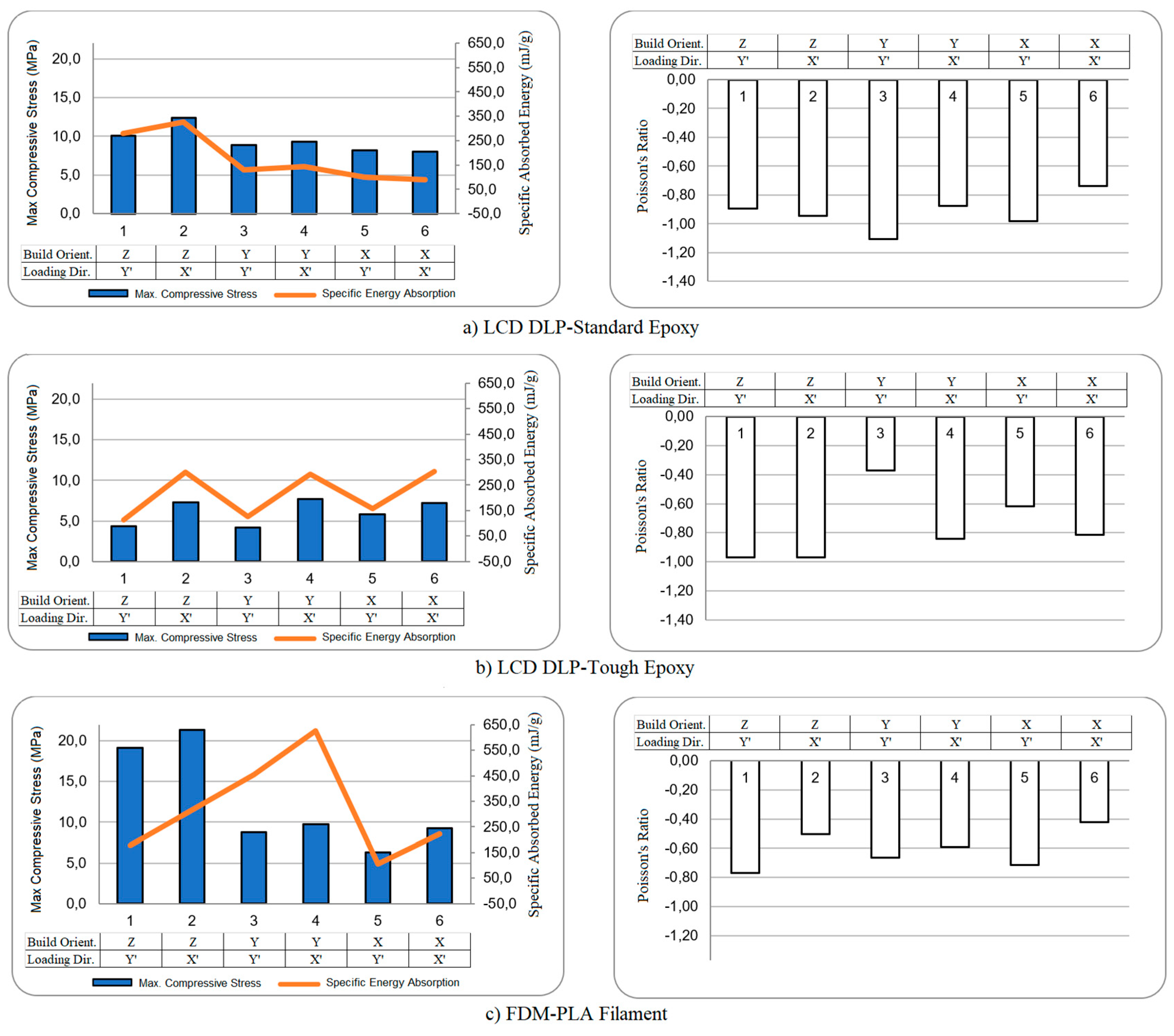

3.1. LCD-DLP – Standard Epoxy

3.2. LCD-DLP – Tough Epoxy

3.3. FDM – PLA Filament

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| SLA | Stereolithography Apparatus |

| SAE | Specific Absorbed Energy |

References

- Lakes, R., 1987, Foam structures with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Science, 235(4792), 1038-1040.

- Evans, K.E., Nkansah, M.A., Hutchinson, I.J., Rogers, S.C., Molecular network design, Nature, 353(6340), 124, 1991.

- Greaves, G.N., Greer, A.L., Lakes, R.S., & Rouxel, T. (2011). Pois-son’s ratio and modern materials. Nature Materials. 10 (11), 823–837.

- Cho, H., Seo, D., and Kim, D. N. (2019). Mechanics of Auxetic Materials. Singapore: Springer.

- Chen, Y., and Wang, Z. (2022). In-plane elasticity of the re-entrant auxetic hexagonal honeycomb with hollow-circle joint. Aerospace Science and Technology, 123, 107432.

- Rossiter, J., Scarpa, F., Takashima, K., and Walters, P. (2012). Design of a deployable structure with shape memory polymers. Behavior and Mechanics of Multifunctional Materials and Composites, 8342, 188-194.

- Bostan, S. (2023). Ökzetik çekirdeğe sahip sandviç plakların par-çacık etkili patlama yükü altında dinamik davranışı. İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Eğitim Enstitüsü Uçak ve Uzay Mühendisliği Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

- Liu, Z., Lei, Q., and Xing, S. (2019). Mechanical characteristics of wood, ceramic, metal and carbon fiber-based PLA composites fabricated by FDM. Journal of Materials Research and Technolo-gy, 8(5), 3743–3753.

- Lay, M., Thajudin, N. L. N., Hamid, Z. A. A., Rusli, A., Abdullah, M. K., and Shuib, R. K. (2019). Comparison of physical and mechanical properties of PLA, ABS and nylon 6 fabricated using fused depo-sition modeling and injection molding. Composites Part B: Engi-neering, 176, 107341.

- Gao, Q., Liao, W. H., and Wang, L. (2020). An analytical model of cylindrical double-arrowed honeycomb with negative Poisson’s ratio. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 173, 105400.

- Singh, D., Singh, R., and Boparai, K. S. (2018). Development and surface improvement of FDM pattern-based investment casting of biomedical implants: A state of art review. Journal of Manufactur-ing Processes, 31, 80–95.

- Nunes, J. P., and Silva, J. F. (2016). Sandwiched composites in aerospace engineering. In Advanced Composite Materials for Aerospace Engineering. 129-174.

- Najmon, J. C., Raeisi, S., and Tovar, A. (2019). Review of additive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry. Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry. 7-31.

- Matta, A. K., Prasad Kodali, S., Ivvala, J., and Kumar, P. J. (2018). Metal prototyping the future of automobile industry: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings, 5(9), 17597–17601.

- Sharma, R., Singh, R., Penna, R., and Fraternali, F. (2018). Investigations for mechanical properties of HAP, PVC and PP based 3D porous structures obtained through biocompatible FDM filaments. Composites Part B: Engineering, 132, 237–243.

- Mohd Pu’ad, N. A. S., Abdul Haq, R. H., Mohd Noh, H., Abdullah, H. Z., Idris, M. I., and Lee, T. C. (2020). Review on the fabrication of fused deposition modelling (FDM) composite filament for biomed-ical applications. Materials Today: Proceedings, 29, 228–232.

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R. Material Anisotropy in Additively Manufactured Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3368. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen C.H.P., Choi Y., Concurrent density distribution and build orientation optimization of additively manufactured functionally graded lattice structures, Computer-Aided Design,Volume 127,2020, 102884, ISSN 0010-4485, . [CrossRef]

- Yan, C., Hao, L., Hussein, A., Bubb, S. L., Young, P., and Raymont, D. (2014). Evaluation of light-weight AlSi10Mg periodic cellular lat-tice structures fabricated via direct metal laser sintering. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 214(4), 856-864.

- Pan, C., Han, Y., and Lu, J. (2020). Design and optimization of lattice structures: A review. Applied Sciences, 10(18), 6374.

- Seharing, A., Azman, A. H., and Abdullah, S. (2020). A review on integration of lightweight gradient lattice structures in additive manufacturing parts. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 12(6), 1687814020916951.

- Nagesha, B. K., Dhinakaran, V., Shree, M. V., Kumar, K. M., Chala-wadi, D., and Sathish, T. J. M. T. P. (2020). Review on characteri-zation and impacts of the lattice structure in additive manufactur-ing. Materials Today: Proceedings, 21, 916-919.

- Tang, Y., Dong, G., Zhou, Q., and Zhao, Y. F. (2017). Lattice structure design and optimization with additive manufacturing constraints. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 15(4), 1546-1562.

- Banhart, J., and Seeliger, H. W. (2008). Aluminium foam sandwich panels: manufacture, metallurgy and applications. Advanced En-gineering Materials, 10(9), 793-802.

- Zhu, F., Lu, G., Ruan, D., and Wang, Z. (2010). Plastic deformation, failure and energy absorption of sandwich structures with metallic cellular cores. International Journal of Protective Structures, 1(4), 507-541.

- Gromat, T., Gardan, J., Saifouni, O. et al. Generative design for additive manufacturing of polymeric auxetic materials produced by fused filament fabrication. Int J Interact Des Manuf 17, 2943–2955 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Valle, R., Pincheira, G., Tuninetti, V., Garrido, C., Treviño, C., & Morales, J. (2022). Evaluation of the Orthotropic Behavior in an Auxetic Structure Based on a Novel Design Parameter of a Square Cell with Re-Entrant Struts. Polymers, 14(20), 4325. [CrossRef]

- Erkan, S., Orhan, S., & Sarikavak, Y. (2024). Effect of production angle on low cycle fatigue performance of 3D printed auxetic Re-entrant sandwich panels. Construction and Building Materi-als, 426, 136119.

- Cakan, B. G. (2021). Effects of raster angle on tensile and surface roughness properties of various FDM filaments. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 35, 3347-3353.

- Usta, F., Türkmen, H. S., & Scarpa, F. (2021). Low-velocity impact resistance of composite sandwich panels with various types of auxetic and non-auxetic core structures. Thin-Walled Struc-tures, 163, 107738.

- Longinos S.N, Hazlett R, Cryogenic fracturing efficacy in granite rocks: Fracture toughness and brazilian test differences after ele-vated temperatures and liquid nitrogen exposure, Geoenergy Sci-ence and Engineering, Volume 244, 2025, 213436, ISSN 2949-8910, https://. [CrossRef]

- 32. Jiang X, Shan W, Fu C, Wang G, Enhanced fracture toughness of epoxy composites via 3D printed PLA Bouligand structures,Materials Letters,Volume 382,2025, 137806, ISSN 0167-577X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2024.137806. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J., Zhang, L., & Gain, A. K. (2023). A novel auxetic unit cell for 3D metamaterials of designated negative Poisson’s ratio. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 260, 108614. [CrossRef]

- Lvov VA, Senatov FS, Veveris AA, Skrybykina VA, Díaz Lan-tada A. Auxetic Metamaterials for Biomedical Devices: Cur-rent Situation, Main Challenges, and Research Trends. Materials (Basel). 2022 Feb 15;15(4):1439. [CrossRef]

- Kolken, H. M., & Zadpoor, A. A. (2017). Auxetic mechanical metamaterials. RSC Advances, 7, 5111–5129. [CrossRef]

- Teng, X. C., Ren, X., Zhang, Y., Jiang, W., Pan, Y., Zhang, X. G., Zhang, X. Y., & Xie, Y. M. (2022). A simple 3D re-entrant auxetic metamaterial with enhanced energy absorption. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 229, 107524. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Harrysson O, West H, Cormier D, Mechanical properties of 3D re-entrant honeycomb auxetic structures realized via additive manufacturing, International Journal of Solids and Structures, Volumes 69–70, 2015, Pages 475-490, ISSN 0020-7683. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M.F. (2024) Ökzetik (auxetic) çok hücreli kiriş yapıların eğilme davranışı. Sakarya üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Makine Mühendisliği Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi.

- Uğurlu, O. (2023) Beton dolgulu öksetik kompozitlerin mekanik özelliklerinin nümerik olarak belirlenmesi. Erzurum Teknik Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

| Parameters | PLA Filament |

| Layer height (mm) | 0.12 |

| Line width (mm) | 0.4 |

| Infill density | %100 |

| Print speed (mm/s) | 50 |

| Support Overhang Angle | 59 |

| Parameters | Standard Resin | Tough Resin |

| Layer height (mm) | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Bottom layer exposure time (s) | 40 | 50 |

| Build platform lift distance (mm) | 5 | 7 |

| Build platform motor speed (mm/s) | 3 | 3 |

| Delay time (s) | 2 | 3 |

| Test Type Name | Printing Orientation | Loading Direction | Schematic representation of testing according to building orientation |

| ZY’ | Z | Y’ |  |

| ZX’ | Z | X’ |  |

| YY’ | Y | Y’ |  |

| YX’ | Y | X’ |  |

| XY’ | X | Y’ |  |

| XX’ | X | X’ |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).