Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

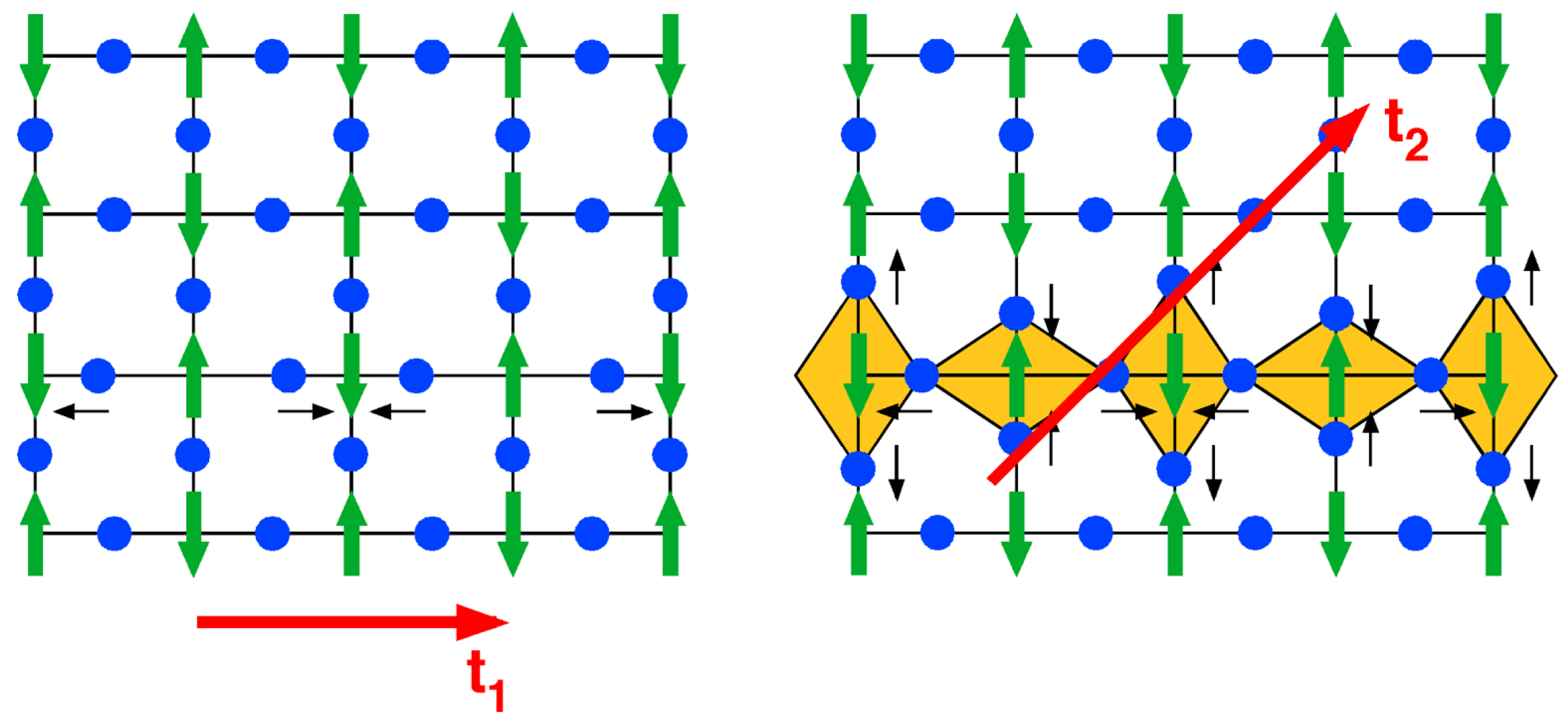

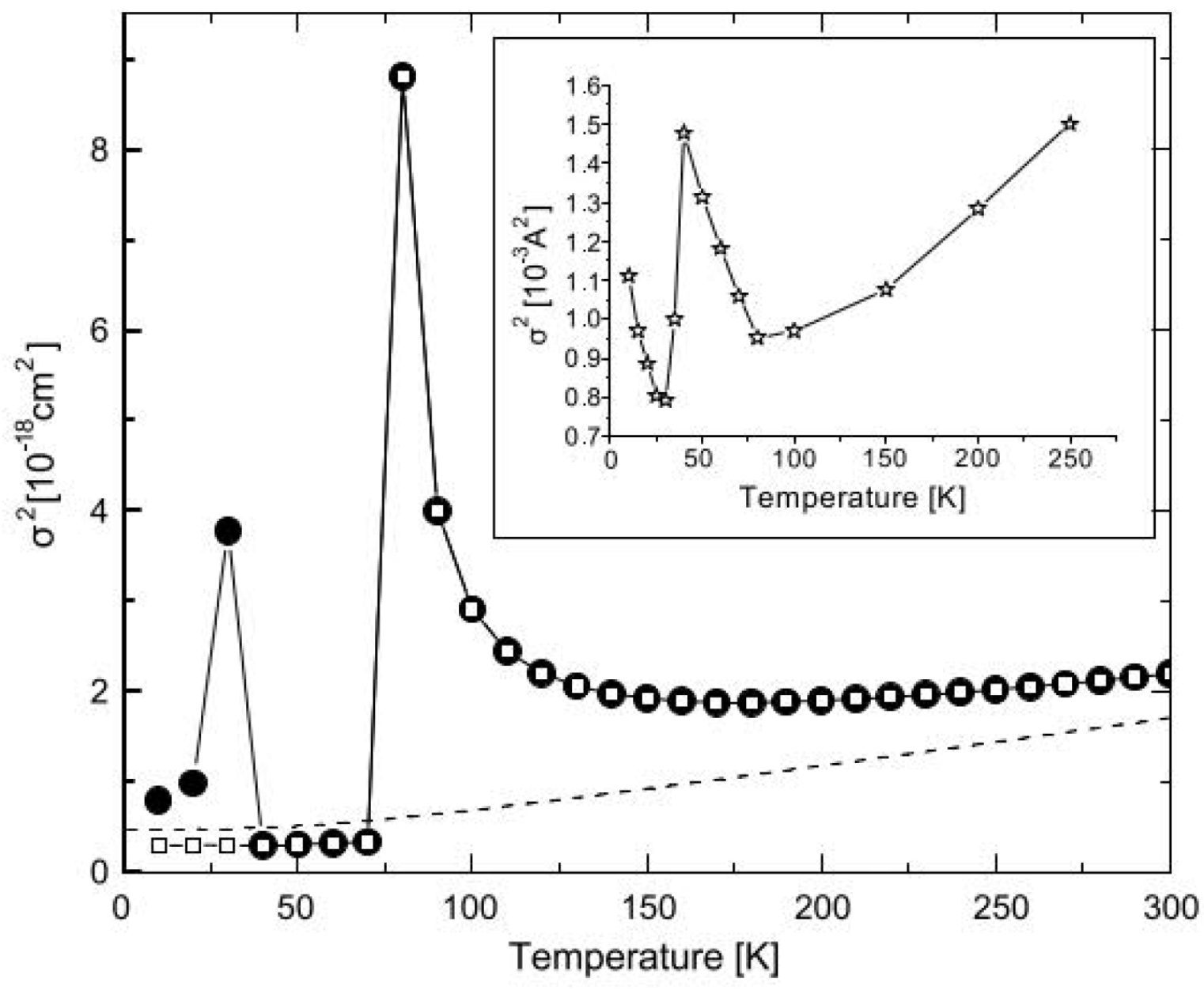

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

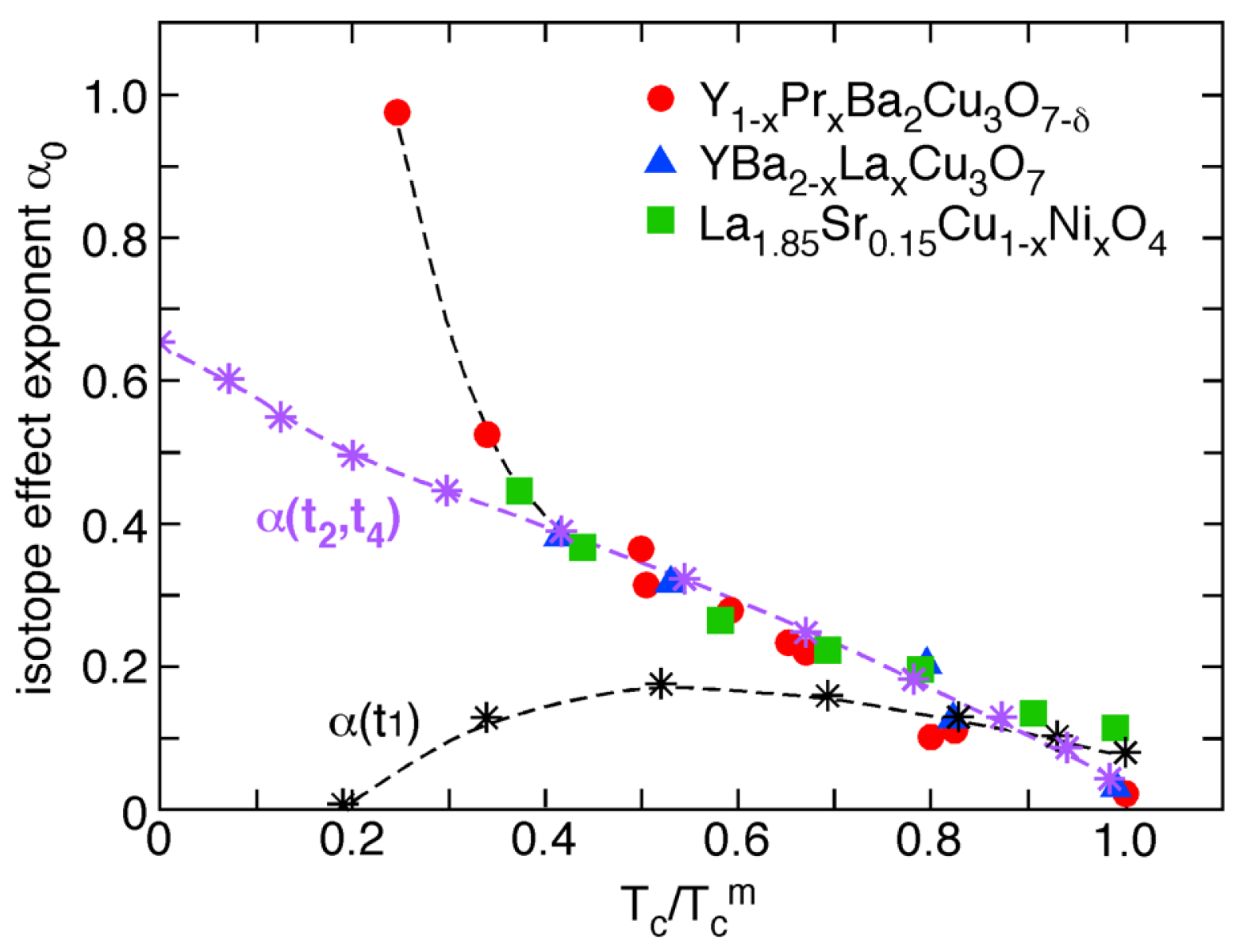

2. Isotope Effects

3. Essential Ingredients for High-Temperature Superconductivity: Heterogeneities and Mixed-Order Parameters in Cuprate Superconductors

4. Theoretical Understanding

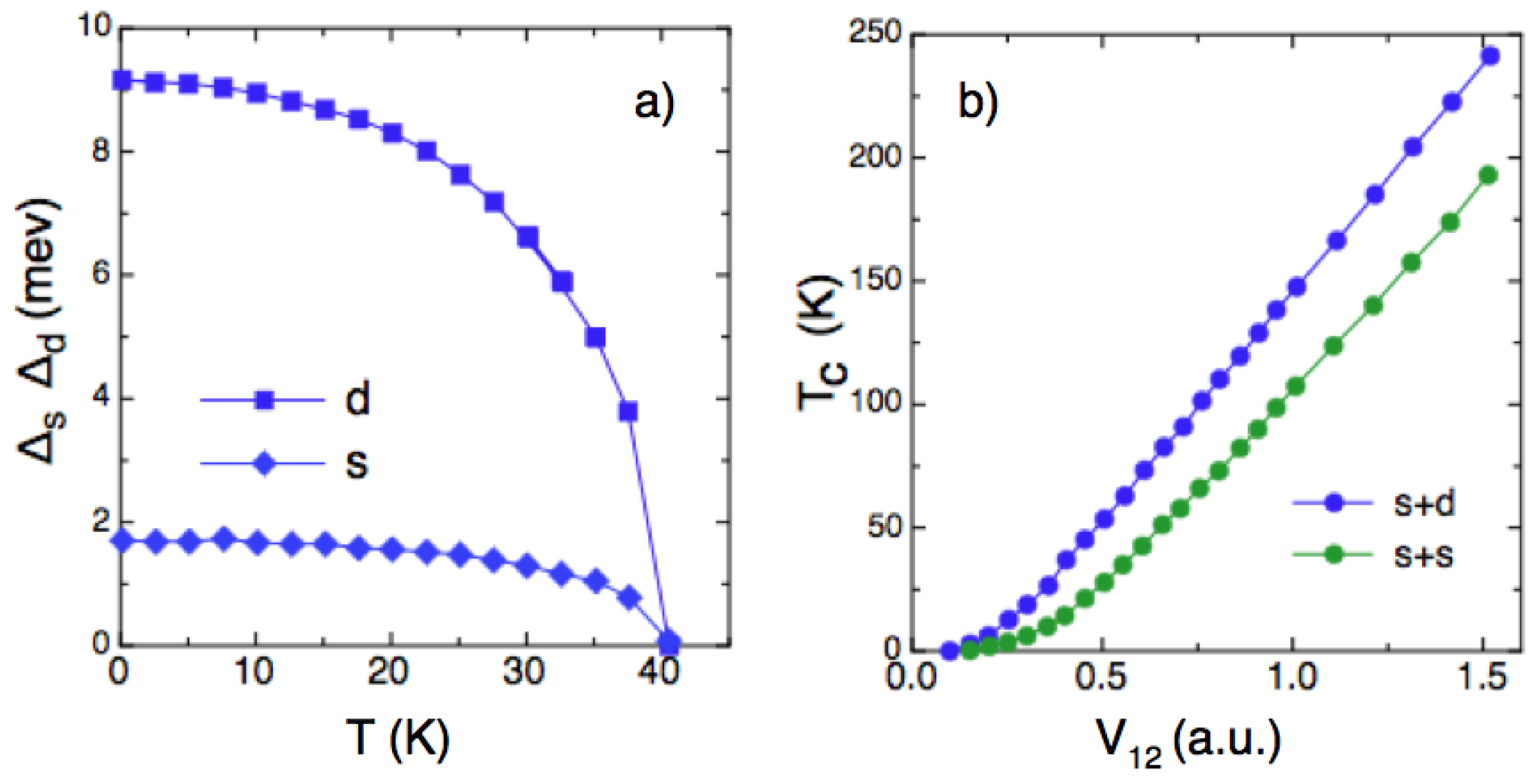

5. Isotope Effects in a Multiband Polaron Approach

6. Conclusions and Outlook for Further Search for High-Temperature Superconductivity

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schooley, J.F.; Hosler, W.R.; Cohen, Marvin L. Superconductivity in Semiconducting SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 12, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, J. Soft-Mode Superconductivity in SrTiO3-x. Phys. Rev. 1969, 180, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, Ch.J.; Sweedler, A.R.; Jensen, M.A.; Broadston, S.; Matthias, B.T. Superconductivity of Sodium Tungsten Bronzes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 746–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, A.W.; Gillson, J.L.; Bierstedt, P.E. High-temperature superconductivity in the BaPb1-xBixO3 systems. Solid State Commun. 1975, 17, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnig, G.; Baratoff, A.; Hoenig, H.E.; Bednorz, J.G. Two-band superconductivity in Nb-doped SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 1352–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastiasoro, Maria N. ; Ruhman, Jonathan; Fernandes, Rafael M. Superconductivity in dilute SrTiO3: A review. Annals of Physics 2020, 417, 168107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessman, Jack. R.; Kahn, A.H.; Shockley William. Electronic Polarizabilities of Ions in Crystals. Phys. Rev. 1953, 92, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilz, H.; Buttner, H.; Bussmann-Holder, A.; Vogl, P. Phonon anomalies in ferroelectrics and superconductors. Ferroelectrics 1987, 73, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

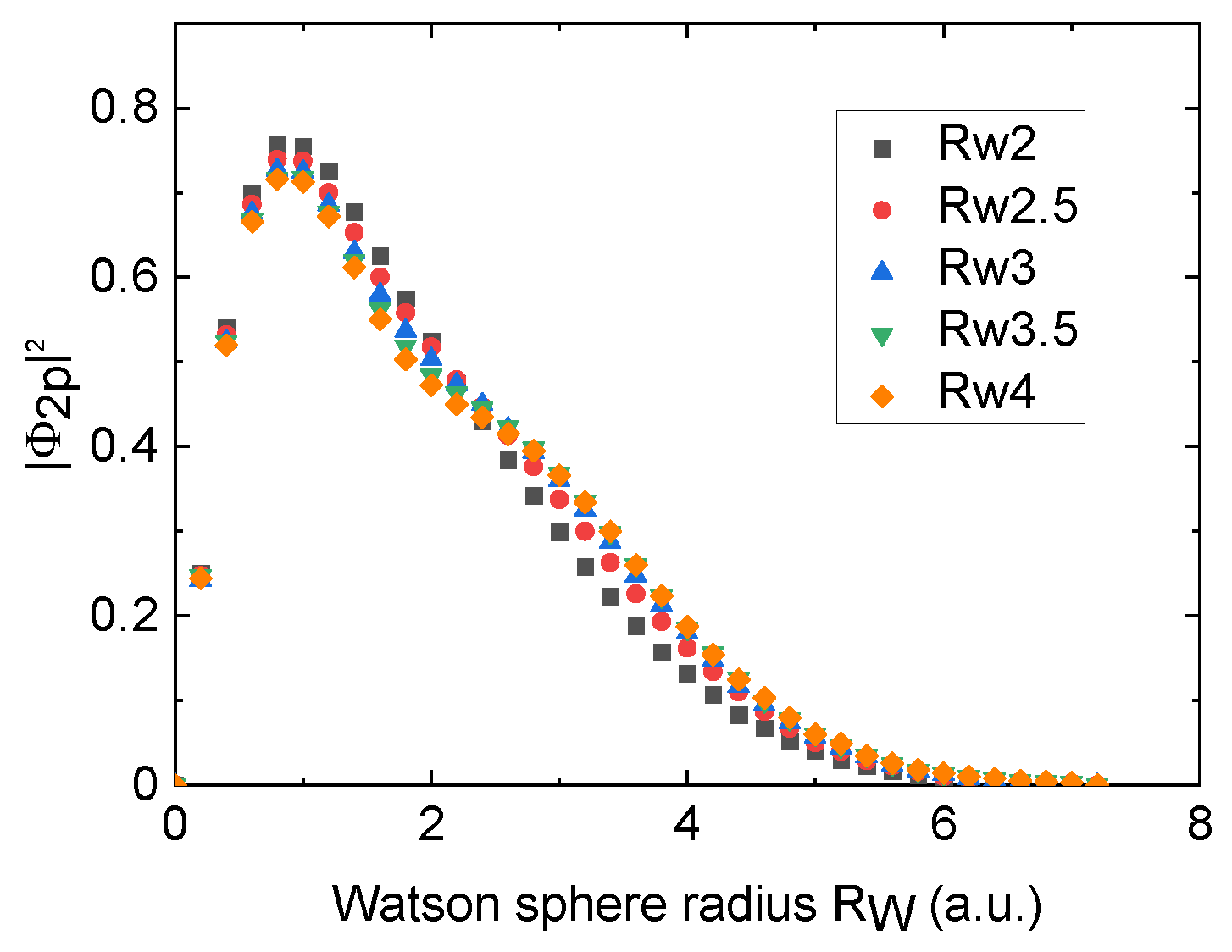

- Watson, Richard E. Analytic Hartree-Fock Solutions for O=. Phys. Rev. 1958, 111, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

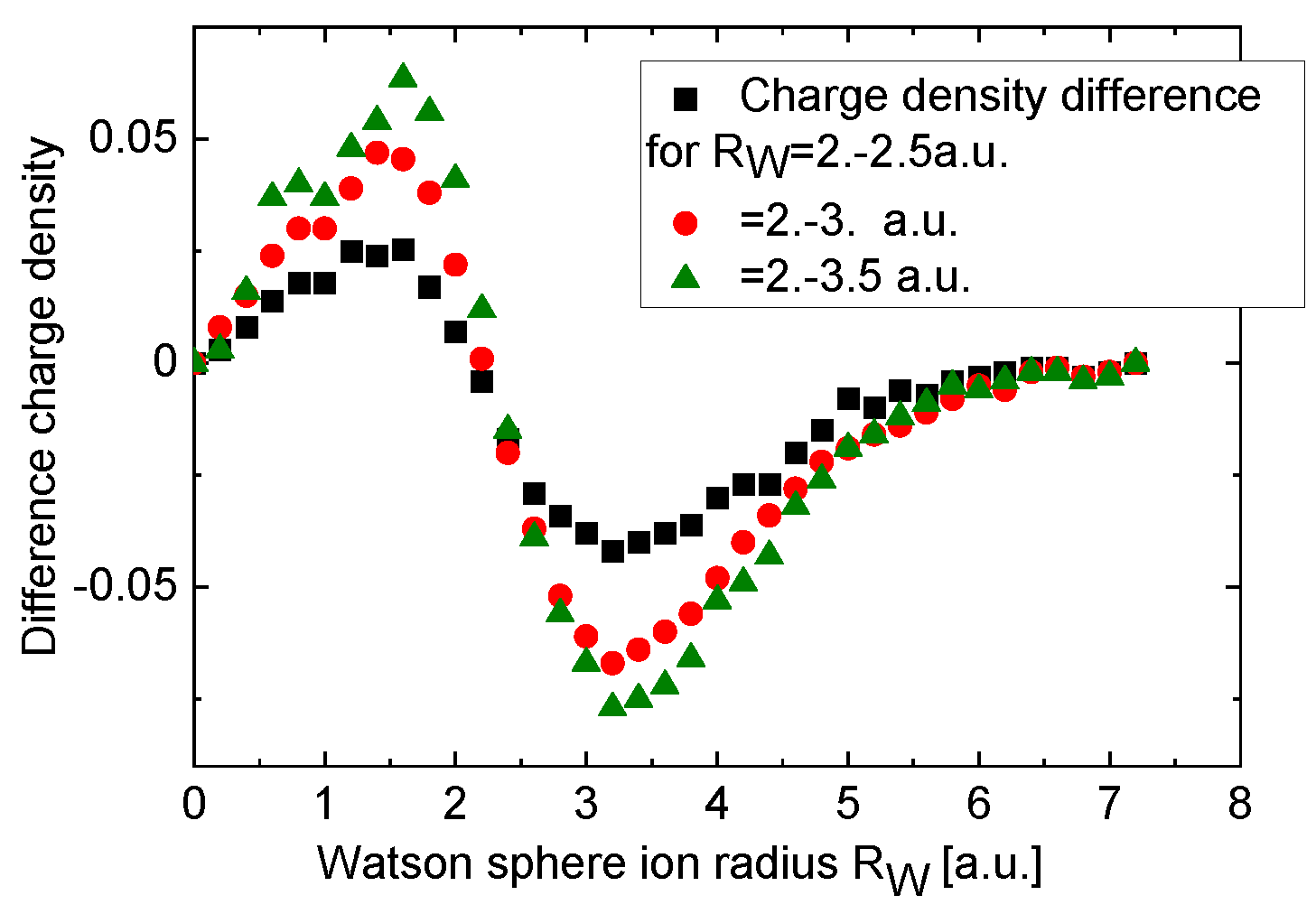

- Bussmann, A.; Bilz, H.; Roenspiess, R.; Schwarz, K. Oxygen polarizability in ferroelectric phase transitions. Ferroelectrics, :1.

- Bussmann-Holder Annette. The polarizability model for ferroelectricity in perovskite oxides. J. Phys: Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 273202. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Jorge E. Superconductivity begins with H. World Scientific (New Jersey, London, Singapore).

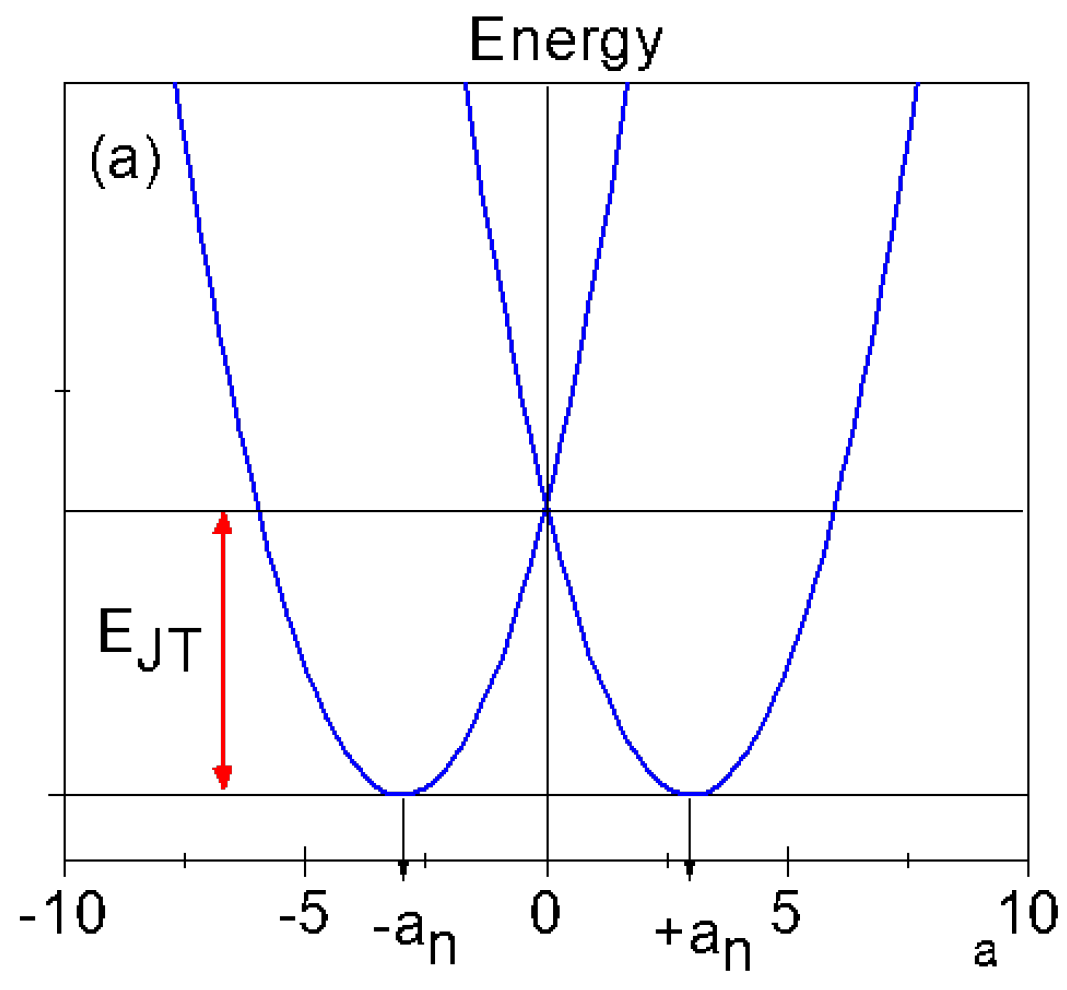

- Höck, K.-H.; Nickisch, H.; Thomas, H. Jahn-Teller effect in itinerant electron systems: the Jahn-Teller polaron. Helv. Phys. Acta 1983, 56, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bednorz, J.G.; Müller, K.A. Possible High Tc Superconductivity in the Ba-La-Cu-O System. Z. Phys. B - Condensed Matter 1986, 64, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlogg, B. : Cava, R.J.; Jayaraman, A.; van Dover, R.B.; Kourouklis, G.A.; Sunshine, S.; Murphy, D.W.; Rupp, L.W.; Chen, H.S.; White, A.; Short, K.T.; Mujsce, A.M.; Rietman, E.A. Isotope Effect in the High-Tc Superconductors Ba2YCu3O7 and Ba2EuCu3O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, Toru; Takahashi, Yoshinori; Ueda, Kazuo. Antiferromagnetic Spin Fluctuations and Superconductivity in Two-Dimensional Metals - A Possible Model for High Tc Oxides. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1990, 59, 2905–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.K.; Farneth, W.E.; McCarron, E.M.; Harlow, R.L.; Moudden, A.H. Oxygen Isotope Effect and Structural Phase Transitions in La2CuO4-Based Superconductors. Science 1990, 250, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

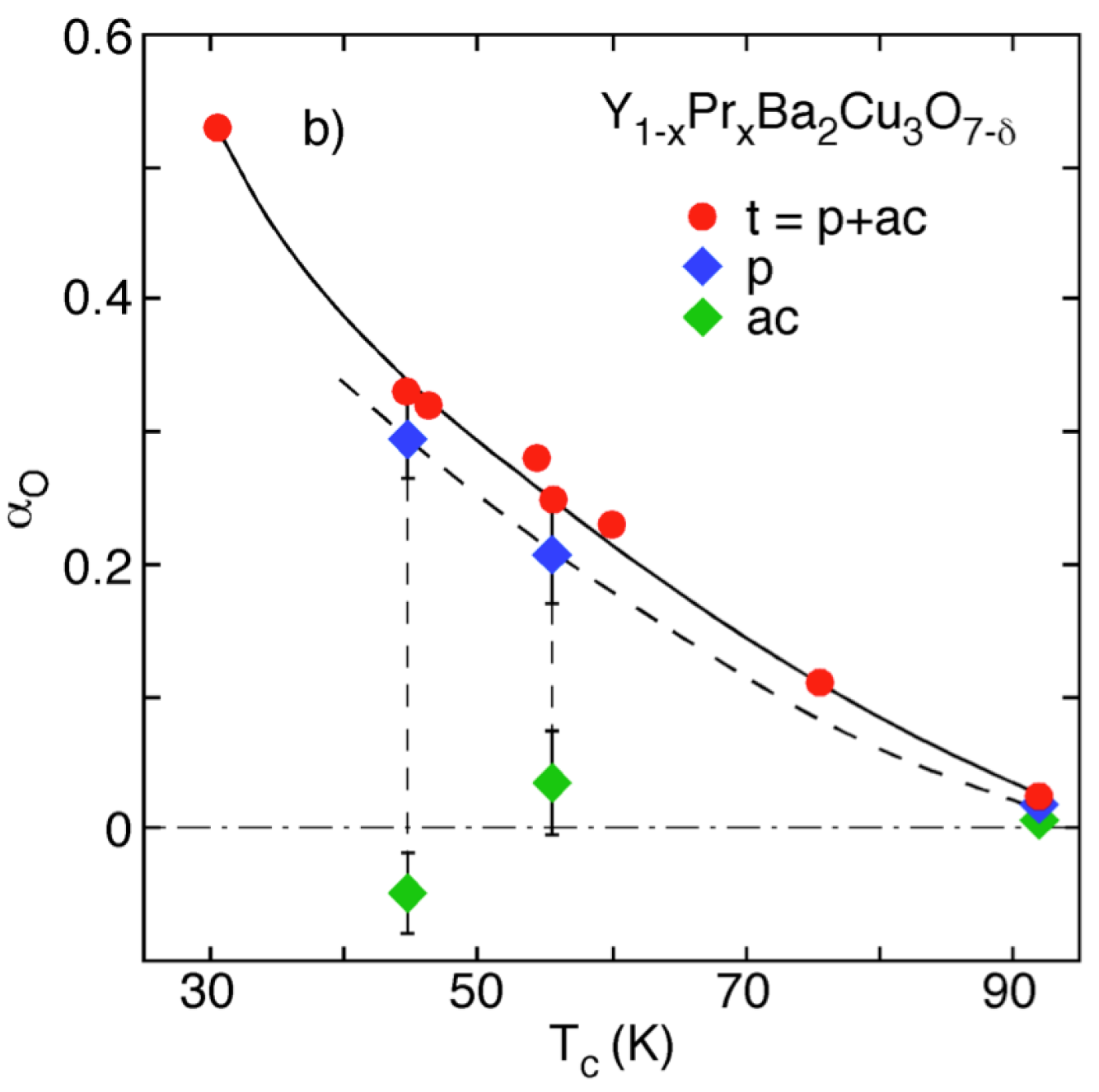

- Franck, J.P.; Jung, J.; Mohamed, A.K.; Gygax, S.; Sproule, G.I. Observation of an oxygen isotope effect in superconducting (Y1-xPrx)Ba2Cu3O7-δ. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 5318–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, JP. Experimental studies of the isotope effect in high temperature superconductors. In Physical properties of high temperature superconductors IV, Ginsberg, D.M., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994; pp. 189–293. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, M.; Liu, R.; Thomsen, C.; Kress, W.; Schönherr, E.; Bauer, M.; Genzel, L.; König, W. Effect of isotopic substitution of oxygen on Tc and the phonon frequencies of high Tc superconductors. Solid State Commun. 1988, 76, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K. A. On the oxygen isotope effect and apex anharmonicity in high-Tc cuprates. Z. Phys. B - Condensed Matter 1990, 80, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, D.; Keller, H.; Conder, K.; Kaldis, E.; Liarokapis, E.; Poulakis, N.; Müller, K.A. Site-selective oxygen isotope effect in optimally doped YBa2Cu3O6+x. Nature (London) 1994, 371, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.M.; Ager III, J.W.; Morris, D.E. Site dependence of large oxygen isotope effect in Y0.7Pr0.3Ba2Cu3O6.97. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 14982–14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasanov, R.; Shengelaya, A.; Morenzoni, E.; Angst, M.; Conder, K.; Savić, I.M.; Lampakis, D.; Liarokapis, E.; Tatsi, A.; Keller, H. Site-selective oxygen isotope effect on the magnetic field penetration depth in underdoped Y0.6Pr0.4Ba2Cu3O7-δ. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 220506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H. Unconventional Isotope Effects in Cuprate Superconductors. In Superconductivity in Complex Systems; Müller, K.A., Bussmann-Holder, A., Eds.; Structure and Bonding 114, Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 2005; pp. 143–169. [Google Scholar]

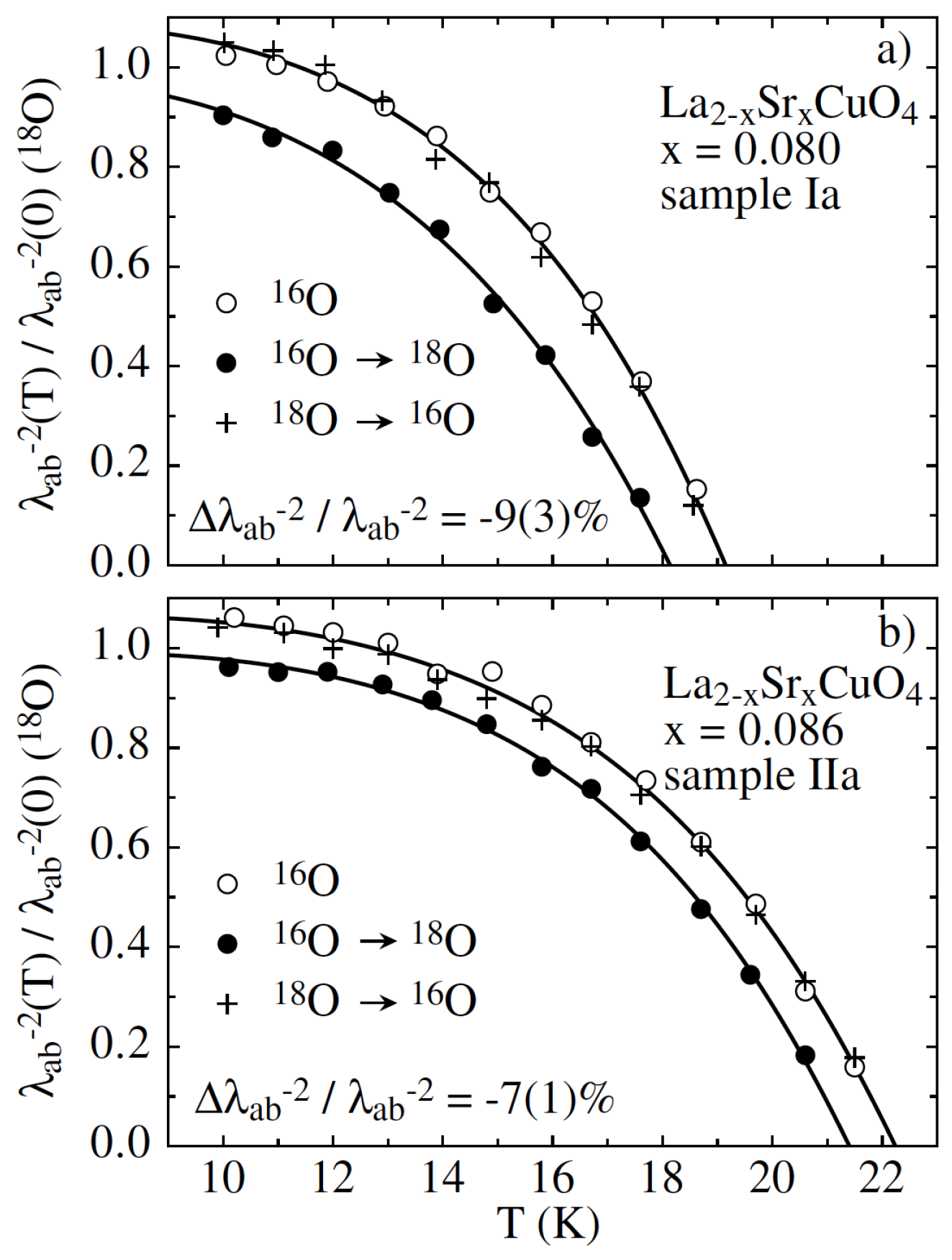

- Hofer, J.; Conder, K.; Sasagawa, T.; Zhao, G.M.; Willemin, M.; Keller, H.; Kishio, K. Oxygen-isotope effect on the in-plane penetration depth in underdoped La2-xSrxCuO4 single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 4192–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianconi, A.; Saini, N.L.; Lanzara, A.; Missori, M.; Rossetti, T.; Oyanagi, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Oka, K.; Ito, T. Determination of the Local Lattice Distortions in the CuO2 Plane of La1.85Sr0.15CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 3412–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campi, G.; Bianconi, A.; Poccia, N.; Bianconi, G.; Barba, L.; Arrighetti, G.; Innocenti, D.; Karpinski, J.; Zhigadlo, N.D.; Kazakov, S.M.; Burghammer, M.; v. Zimmermann, M.; Sprung, M.; Ricci, A. Inhomogeneity of charge-density-wave order and quenched disorder in a high-Tc superconductor. Nature (London) 2015, 525, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollman, D.A.; Van Harlingen, D.J.; Lee, W.C.; Ginsberg, D.M.; Leggett, A.J. Experimental determination of the superconducting pairing state in YBCO from the phase coherence of YBCO-Pb dc SQUIDs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 2134–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuei, C.C.; Kirtley, J.R.; Chi, C.C.; Yu-Jahnes, Lock See; Gupta, A. ; Shaw, T.; Sun, J.Z.; Ketchen, M.B. Pairing Symmetry and Flux Quantization in a Tricrystal Superconducting Ring of YBa2Cu3O7-δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawner, D.A.; Ott, H.R. Evidence for an unconventional superconducting order parameter in YBa2Cu3O6.9. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.G.; Gajewski, D.A.; Maple, M.B.; Dynes, R.C. Observation of Josephson pair tunneling between a high-Tc cuprate (YBa2Cu3O7-δ) and a conventional superconductor (Pb). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 72, 2267–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.; Mali, M.; Roos, J.; Brinkmann, D. Spin pseudogap and interplane coupling in Y2Ba4Cu7O15: A 63 Cu nuclear spin-spin relaxation study. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 15478–15483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, N.; Scalapino, D.J. Calculation of the transverse nuclear relaxation rate for YBa2Cu3O7 in the superconducting state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 2898–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, K. Alex. Possible coexistence of s- and d-wave condensates in copper oxide superconductors. Nature (London) 1995, 377, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.A.; Keller, H. s and d Wave Symmetry Components in High-Temperature Cuprate Superconductors. In High-Tc Superconductivity 1996: Ten Years after the Discovery; Kaldis, E., Liarokapis, E., Müller, K.A., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht/Boston/London, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K.A. On the macroscopic s- and d-wave symmetry in cuprate superconductors. Phil. Mag. Lett. 2002, 82, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanov, R.; Shengelaya, A.; Maisuradze, A.; La Mattina, F.; Bussmann-Holder, A.; Keller, H.; Müller, K.A. Experimental evidence for two gaps in the high-temperature La1.83Sr0.17CuO4 superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 057007–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

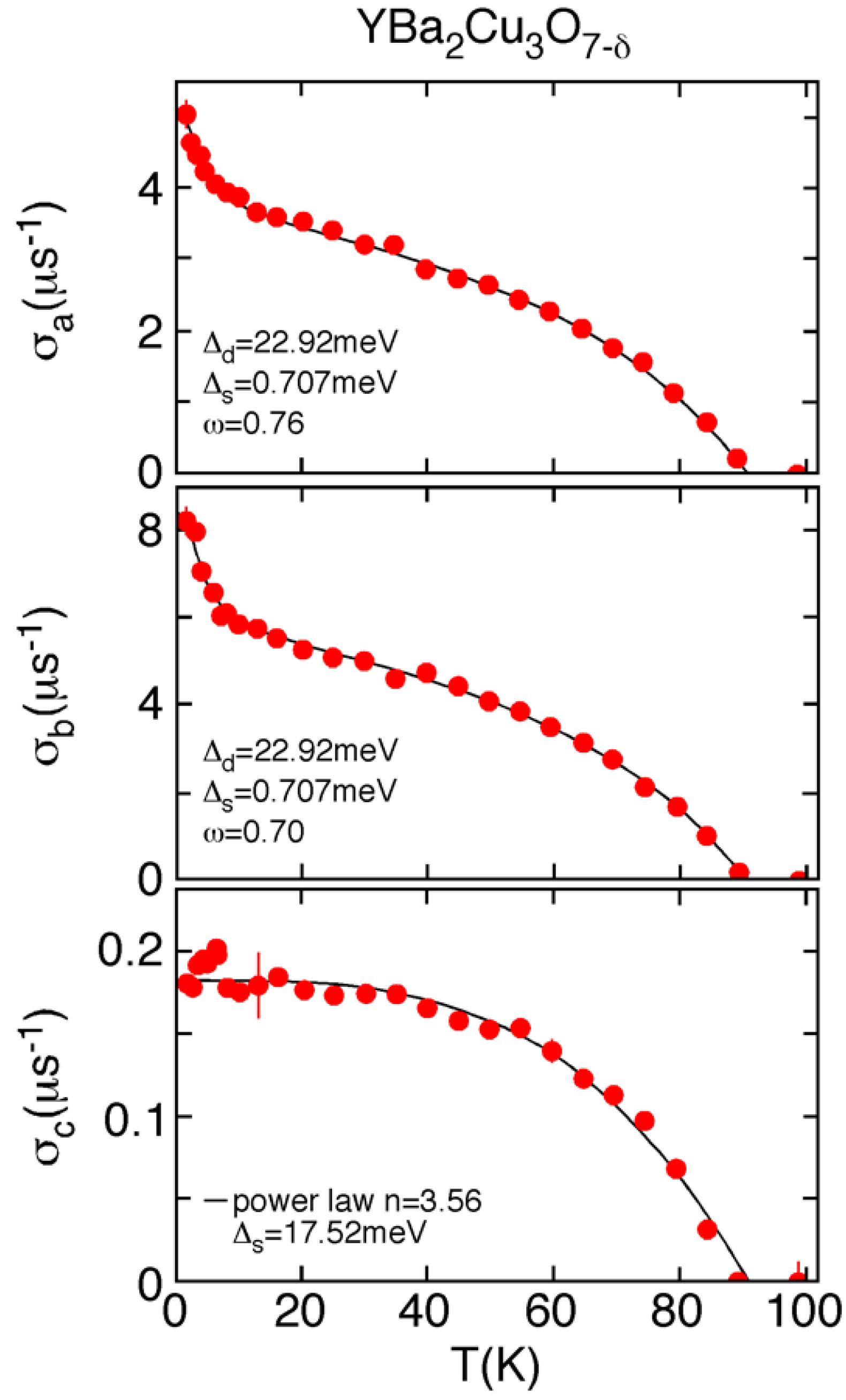

- Khasanov, R.; Strässle, S.; Di Castro, D.; Masui, T.; Miyasaka, S; Tajima, S. ; Bussmann-Holder, A.; Keller, H. Multiple gap symmetries for the order parameter of cuprate superconductors from penetration depth measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 237601–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasanov, R.; Shengelaya, A.; Karpinski, J.; Bussmann-Holder, A.; Keller, H.; Müller, K.A. s-wave symmetry along the c-axis and s+d in-plane superconductivity in bulk YBa2Cu4O8. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2008, 21, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

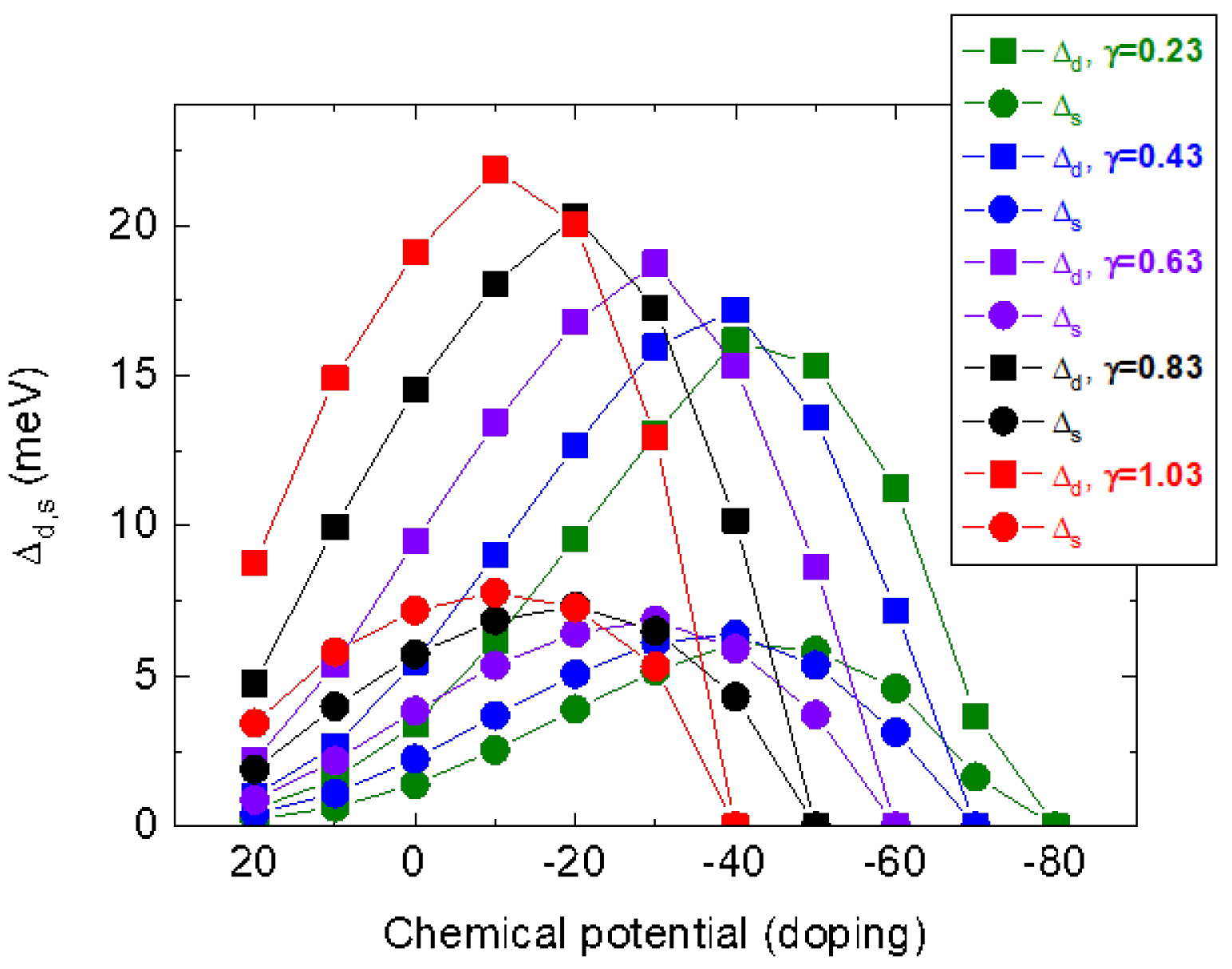

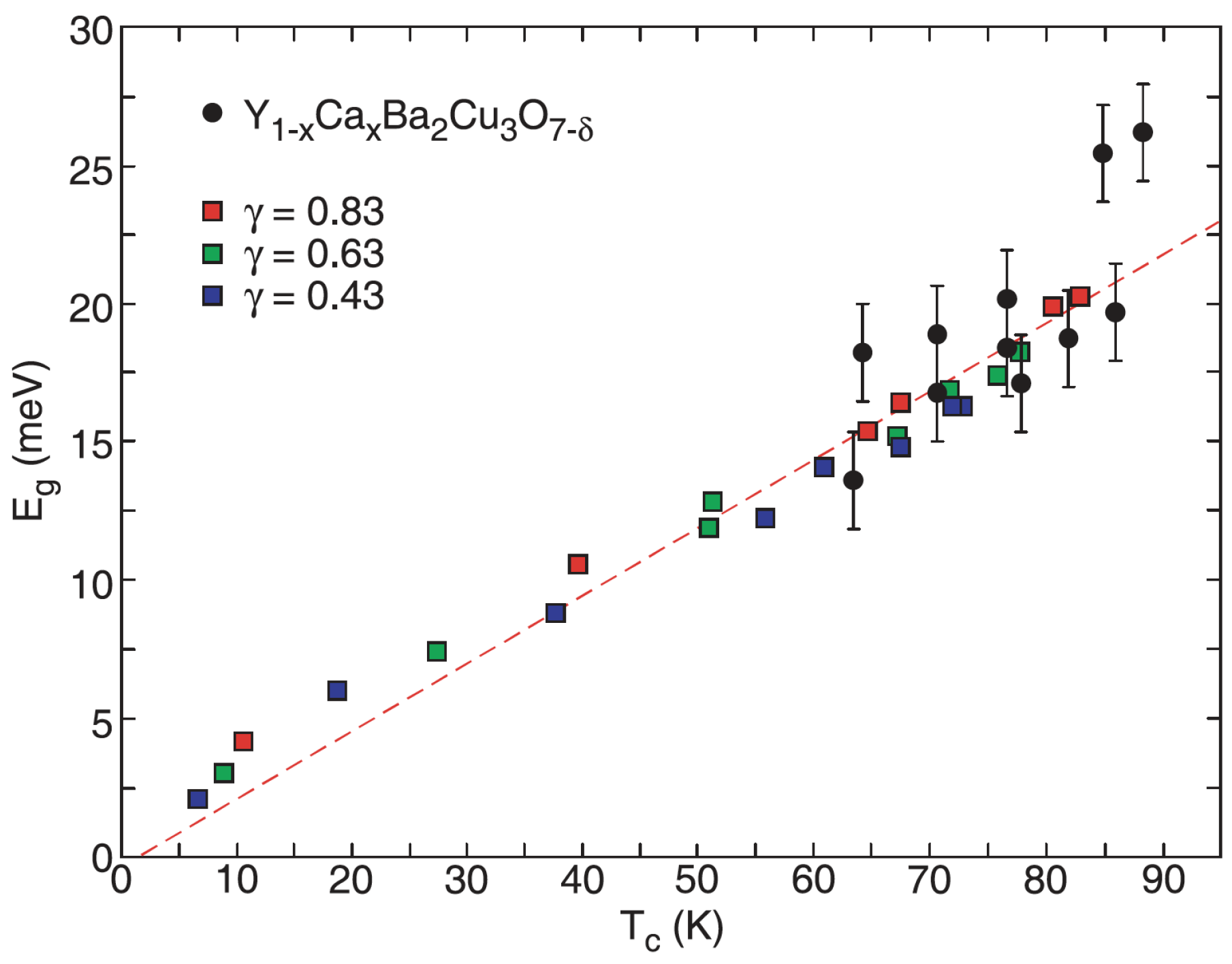

- Bussmann-Holder, A.; Khasanov, R.; Shengelaya, A.; Maisuradze, A.; La Mattina, F.; Keller, H.; Müller, K.A. Mixed order parameter symmetries in cuprate superconductors. Europhys. Lett. 2007, 77, 27002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann-Holder, A. Evidence for s+d Wave Pairing in Copper Oxide Superconductors from an Analysis of NMR and NQR Data. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2012, 25, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Nantoh, M.; Heike, S.; Takagi, S.; Ogino, M.; Kawasaki, M.; Koinuma, H.; . Kitazawa, K. Scanning tunneling spectroscopy on high Tc superconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1993, 54, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.; Slichter, C.P.; Williams, G.V.M. Evidence for two electronic components in high-temperature superconductivity from NMR. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 455702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandur, Daniel; Nachtigal, Jakob; Lee, Abigail; Tsankov, Stefan; Haase, Jürgen. Cuprate universal electronic spin response and the pseudogap from NMR. arXiv:2309.11874v3 [cond-mat.supr-con] 3 Mar 2024, arXiv:2309.11874v3 [cond-mat.supr-con] 3 Mar 2024.

- Pelc, Damian; Vuc̆ković, Marija; Grbić, Mihael S.; Poz̆ek, Miroslav; Yu, Guichuan; Sasagawa, Takao; Greven, Martin; Baris̆ić, Neven. Emergence of superconductivity in the cuprates via a universal percolation process. Nat. Commun. 4327.

- Li, Q.P.; Koltenbah, B.E.C.; Joynt, Robert. Mixed s-wave and d-wave superconductivity in high- TC systems. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, Daniel; Continentino, Mucio A. ; Thomas, Christopher; Lacroix, Claudine. s-and d-wave superconductivity in a two-band model. Annals of Physics 2016, 373, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Micnas, R.; Robaszkiewicz, S.; Bussmann-Holder, A. Two-Component Scenarios for Non-Conventional (Exotic) Superconductors. In Superconductivity in Complex Systems; Müller, K.A., Bussmann-Holder, A., Eds.; Structure and Bonding 114, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 13–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann-Holder, A.; Keller, H. Polaron formation as origin of unconventional isotope effects in cuprate superconductors. Eur. Phys. J. B 2005, 44, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhl, H.; Matthias, B.T.; Walker, L.R. Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer Theory of Superconductivity in the Case of Overlapping Bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1959, 3, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalenko, V. Superconductivity in metals with overlapping energy bands. Fiz. Met. Metalloved. 1959, 8, 2518–2529. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, I.G.; Firsov, Y.A. Kinetic Theory of Semiconductors with Low Mobility. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 1962, 43, 1843–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, H.; Bussmann-Holder, A.; Müller, K.A. Jahn-Teller physics and high-Tc superconductivity. Materials Today 2008, 11, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanagi, H.; Zhang, C.; Tsukada, A.; Naito, M. Lattice instability in high temperature superconducting cuprates probed by x-ray absorption. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 108, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann-Holder, A.; Keller, H.; Bishop, A.R.; Simon, A.; Müller, K.A. Polaron coherence as origin of the pseudogap phase in high temperature superconducting cuprates. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2008, 21, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).