Submitted:

09 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Cosmological Constant Problem: By attributing the cosmological constant to the elastic properties of spacetime and incorporating into our calculations, the model provides a natural mechanism for incorporating dark energy and the accelerated expansion of the universe [6,8]. Additionally, the time averaging of quantum fluctuations explains why large theoretical predictions of vacuum energy do not manifest in observable large-scale effects.

- Black Hole Singularities and Information Loss Paradox: Through the quantisation of energy levels within black holes and encoding information in standing waves, the STM model prevents the formation of singularities and proposes a resolution to the information loss paradox [2,9], aligning with quantum principles.

- Quantum Interference Phenomena: The model explains quantum interference patterns through persistent waves on the STM membrane, derived from first principles, providing a geometric interpretation of quantum mechanics [10].

2. Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework of the STM Model

-

Mirror Universe and Mirror Particles:

- -

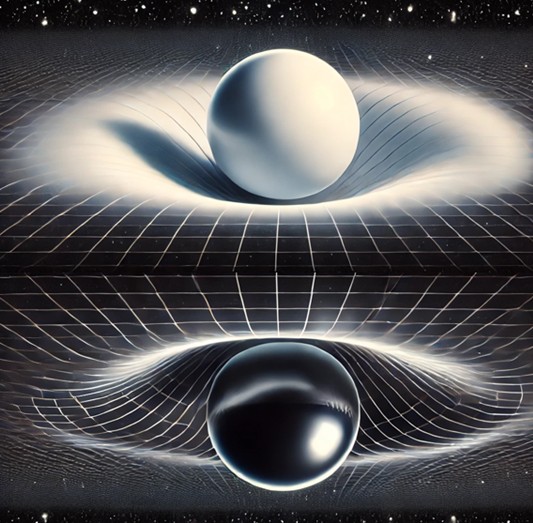

- Existence of a Mirror Universe: The STM model posits the existence of a mirror universe that is a reflection of our own universe. This mirror universe is an adjacent layer of the spacetime membrane, mirroring the properties and dynamics of our universe.

- -

-

Particles and Mirror Antiparticles:

- *

- Mirror Antiparticles: For every particle in our universe, there exists a corresponding mirror antiparticle in the mirror universe. These mirror antiparticles are not antimatter in the conventional sense but are mirror counterparts that possess opposite properties in certain aspects, such as charge or parity.

- *

- Symmetry and Balance: The existence of mirror antiparticles ensures the preservation of symmetry and balance within the STM framework. This duality between particles and their mirror antiparticles is fundamental to the model’s explanation of energy exchange and force interactions.

-

Particles and Mirror Particles Interactions:

- -

-

Attraction and Repulsion Mechanisms:

- *

- Attraction between Particles and Mirror Antiparticles: Particles in our universe are attracted to their corresponding mirror antiparticles in the mirror universe. This attraction facilitates the transfer of energy into the STM membrane.

- *

- Repulsion between Particles and Mirror Particles: Conversely, particles repel their identical mirror particles. This repulsion promotes the movement of energy out of the STM membrane.

- -

- Balancing of Forces and Energy Exchange: The interplay between these attractive and repulsive forces results in a dynamic exchange of energy between the particles and the STM membrane. This balancing of forces is crucial for maintaining the stability of the membrane and for governing the interactions at the quantum level.

-

Photons as Composite Particle–Antiparticle Pairs:

- -

- Oscillation Dynamics: Photons are modelled as composite entities consisting of particle–antiparticle pairs oscillating transversely along the x or y axis on the STM membrane. These oscillations involve the continual conversion of energy between the particles and the membrane, influenced by the interactions with mirror particles and mirror antiparticles.

- -

- Energy Dynamics: The oscillating particle–antiparticle pairs transfer energy into and out of the STM membrane, affecting the local curvature of spacetime. Energy not absorbed by the membrane manifests as mass–energy, influencing spacetime curvature in accordance with General Relativity (GR). In contrast, energy absorbed into the membrane contributes to a homogeneous background, consistent with the cosmological constant .

-

Preservation of Quantum Characteristics:

- -

- Spin-1 Nature: The composite photon model preserves the spin-1 characteristic of photons because the combined angular momenta of the particle and antiparticle pair sum to one.

- -

- Polarisation: Transverse oscillations inherently account for the two polarisation states of photons, consistent with electromagnetic wave behaviour.

- -

- Masslessness: The net zero mass–energy over a full oscillation cycle ensures that photons remain massless, as observed in Quantum Field Theory (QFT).

- -

- Lorentz Invariance: The oscillatory dynamics maintain Lorentz invariance, ensuring consistency with the principles of special relativity.

-

Interaction Dynamics:

- -

- Energy Exchange Mechanism: The interactions between particles, mirror particles, and composite photons facilitate the transfer of energy into and out of the STM membrane. This mechanism is fundamental to the model, as it explains how localised energy variations influence spacetime curvature and how the membrane’s properties govern particle interactions.

- -

- Membrane Deformations: These interactions induce deformations in the STM membrane, resulting in observable gravitational and quantum phenomena. The balancing of attractive and repulsive forces ensures that energy dynamics are consistent with conservation laws and that the membrane’s stability is maintained.

- Independence from QFT Forces: The STM model operates independently of the forces described by QFT, requiring no modifications to the established quantum framework. This independence ensures that QFT remains unchanged, preserving its successful descriptions of particle interactions while the STM model provides a complementary framework for gravitational phenomena.

2.2. Mathematical Formulation

2.2.1. Modelling Photons as Composite Particle–Antiparticle Pairs

- Energy Transfer: The oscillating particle–antiparticle pairs transfer energy into and out of the STM membrane. When particles and mirror antiparticles attract, energy is absorbed into the membrane, contributing to its homogeneous energy density. Conversely, when particles and mirror particles repel, energy is released from the membrane, presenting as localised mass–energy that affects spacetime curvature.

- Effect on Spacetime Curvature: The energy not absorbed by the STM membrane manifests as mass–energy influencing local spacetime curvature, consistent with GR. The energy absorbed into the membrane contributes to a homogeneous background energy, aligning with the cosmological constant .

- Spin-1 Nature: The composite photon maintains a total spin of 1, consistent with observations in QFT, due to the vector addition of the particle and antiparticle spins.

- Polarisation: The transverse oscillations account for the photon’s polarisation states, aligning with electromagnetic wave properties.

- Masslessness: The net zero mass–energy over a full cycle ensures the photon remains massless, in agreement with QFT predictions.

- Lorentz Invariance: The model respects Lorentz invariance, as the equations are formulated using relativistically invariant quantities.

2.2.2. Modified Elastic Wave Equation

- is the membrane’s mass density.

- T is the membrane’s tension.

- is the intrinsic elastic modulus of the membrane.

- represents local variations in the elastic modulus due to particle oscillations.

- represents any external forces acting on the membrane.

- and are the Laplacian and biharmonic operators, respectively.

- Understanding Persistent Waves: It explains how the oscillating adjustments to the elastic modulus generate persistent waves on the spacetime membrane (see Section 2.2.2).

- Energy Dynamics: It provides insight into how energy is transferred into and out of the membrane through particle interactions.

- Linking to Cosmological Constant: By relating to the cosmological constant (as detailed in Appendix A.1.6), it offers a potential solution to the cosmological constant problem.

2.2.3. Derivation of the Potential Energy Function

2.2.4. Derivation of the Force Function

2.2.5. Modelling Particles and Mirror Particles Interaction

- Attractive Forces: Particles attract mirror antiparticles, facilitating the transfer of energy into the STM membrane.

- Repulsive Forces: Particles repel mirror particles, promoting the release of energy from the STM membrane.

- Stable Equilibrium (n odd): Particles are localised at positions where the potential energy is minimised, corresponding to the balance of forces due to attraction and repulsion.

- Unstable Equilibrium (n even): Particles are at positions where any small perturbation leads to destabilisation.

2.2.6. Energy Dynamics of the STM Membrane

2.2.7. Modelling Persistent Waves

- Localised Oscillations: As particles oscillate, they induce localised changes in the membrane’s properties. Specifically, the elastic modulus experiences time-dependent variations due to the energy exchange between the particles and the membrane.

- Mathematical Representation:

-

Where:

- -

- is a proportionality constant.

- -

- is the amplitude of the particle oscillation.

- -

- k is the wave vector.

- -

- is the angular frequency.

- -

- is the position vector.

- Coupling to the Membrane: The oscillating acts as a source term in the elastic wave equation, effectively coupling the particle’s oscillations to the membrane’s dynamics.

- Induced Wave Propagation: These oscillations in generate disturbances in the membrane that propagate as waves. The periodic nature of leads to continuous generation of waves, resulting in persistent wave patterns on the membrane.

- Mathematical Description:

- The modified elastic wave equation incorporating is:

- The oscillating term introduces a time-dependent modulation in the stiffness of the membrane, which acts as a driving force for wave propagation.

- Sustained Oscillations: The continuous oscillation of particles ensures that the adjustments to the elastic modulus are ongoing, leading to sustained wave generation.

- Coherent Wave Patterns: The waves generated are coherent due to the consistent frequency and phase of the particle oscillations, resulting in persistent wave patterns that can interfere and produce observable quantum effects.

- Interference Patterns: The persistent waves on the membrane explain the interference patterns observed in quantum experiments, such as the double-slit experiment.

- Wave–Particle Duality: The dual nature of particles as both wave-like and particle-like entities is naturally incorporated into the STM model through the dynamics of the membrane and the generation of persistent waves.

- Rationale: To analyse the overall effect of the oscillating on the membrane dynamics, we perform a time averaging over a full oscillation period.

- Effect on Wave Equation: The time-averaged elastic modulus simplifies the elastic wave equation while capturing the essential features of the persistent wave generation.

- Expression:

- Interpretation: The effective elastic modulus reflects the average effect of the particle-induced oscillations on the membrane’s stiffness, contributing to the propagation of persistent waves.

2.2.8. Derivation of Einstein Field Equations and Time Dilation from the STM Model

- is the Einstein tensor representing spacetime curvature.

- is the stress–energy tensor derived from the membrane’s elastic properties.

- is Einstein’s gravitational constant.

- is the cosmological constant.

2.2.9. Addressing the Cosmological Constant Problem

2.2.10. Quantum Interference and Persistent Waves

- is the phase difference between the two paths.

- Interference Arises from Persistent Waves: The interference arises from the superposition of persistent waves on the STM membrane.

- Membrane’s Elastic Properties: The membrane’s elastic properties allow for the coherent propagation and interference of these waves.

- Alignment with Quantum Mechanics: This derivation aligns with standard quantum mechanical predictions, demonstrating the STM model’s ability to reproduce quantum phenomena from first principles [10].

2.2.11. Black Hole Physics and Information Loss Paradox

- Standing Wave Modes: The quantised energy levels correspond to specific standing wave modes within the black hole.

- Information Storage: Information about infalling matter is preserved in the configuration of these standing waves.

3. Results

3.1. Theoretical Predictions from the STM Model

3.1.1. Reproduction of Einstein Field Equations

3.1.2. Quantum Interference and Persistent Waves

3.1.3. Energy Dynamics and the Cosmological Constant

3.1.4. Prevention of Singularity Formation in Black Holes

3.1.5. Resolution of the Information Loss Paradox

3.1.6. Implications for High-Energy Physics and Quantum Gravity

3.1.7. Experimental Proposals

- Gravitational Wave Detection: Looking for anomalies in gravitational wave signals that could indicate the elastic properties of spacetime.

- Quantum Interference Experiments: Testing the persistence of interference patterns over extended distances to support the concept of persistent waves.

- Vacuum Energy Measurements: Precise measurements of vacuum energy density to test the model’s explanation of the cosmological constant.

3.2. Comparative Analysis with Existing Theories

3.2.1. Comparison with String Theory

- Dimensional Framework: The STM model operates within the familiar four-dimensional spacetime, avoiding the need for extra dimensions. This adherence to observed dimensions aligns the STM model more closely with empirical evidence, whereas string theory’s extra dimensions remain unobserved despite extensive experimental searches.

- Fundamental Entities: String theory introduces fundamentally new entities—strings and higher-dimensional branes—as the building blocks of matter and forces. In contrast, the STM model utilises the existing concept of spacetime, attributing elastic properties to it. Particles are manifestations of oscillations on this spacetime membrane, eliminating the need for introducing new fundamental objects.

- Mathematical Complexity and Accessibility: String theory involves highly complex mathematics, including advanced topics in differential geometry, topology, and conformal field theory. The STM model, while mathematically rigorous, is grounded in classical elasticity theory extended to four dimensions. This potentially makes the STM model more accessible and easier to integrate with established physical theories.

- Experimental Testability: A significant challenge for string theory is the lack of direct experimental evidence, primarily due to the extremely high energies required to probe string-scale physics. The STM model, on the other hand, proposes phenomena that could be tested with current or near-future technology (see Appendix B and Appendix F). For instance, deviations in gravitational wave signals or quantum interference patterns predicted by the STM model could be within the reach of upcoming experiments.

3.2.2. Comparison with Loop Quantum Gravity

- Continuity vs Discreteness: LQG posits that spacetime is fundamentally discrete, with quantised volumes and areas. In contrast, the STM model treats spacetime as a continuous elastic membrane. This difference leads to distinct predictions about spacetime’s behaviour at the smallest scales.

- Mathematical Formalism: LQG relies on advanced mathematical constructs like spin networks and loop variables, requiring complex quantisation techniques. The STM model employs differential equations and elasticity theory, potentially offering a more straightforward mathematical framework that builds directly on classical physics.

- Unification Scope: While LQG focuses on quantising gravity without necessarily integrating the other fundamental forces, the STM model provides a framework that could, in principle, incorporate electromagnetic and other interactions through the dynamics of the spacetime membrane. By modelling particles as oscillations on the membrane, the STM model hints at a more unified approach.

- Phenomenological Predictions: Both theories face challenges in making experimentally testable predictions. However, the STM model suggests specific experiments, such as observing persistent wave effects or deviations in gravitational phenomena, which may be more accessible with current technology.

3.2.3. Application of Occam’s Razor

- Minimal Assumptions: The STM model posits that the known four-dimensional spacetime, endowed with elastic properties, is sufficient to describe both quantum and gravitational phenomena. This contrasts with string theory’s introduction of additional dimensions and fundamental entities like strings and branes.

- Simplicity of Framework: By using the established concepts of elasticity and spacetime, the STM model avoids the complexities associated with quantising gravity or introducing new mathematical structures. This simplicity aligns with Occam’s razor by not multiplying entities beyond necessity.

- Direct Correspondence with Observables: The STM model directly relates its theoretical constructs to observable phenomena, such as spacetime curvature and particle oscillations. This direct correspondence reduces the gap between theory and experiment, adhering to the principle of parsimony.

3.2.4. Overall Assessment

- STM Model: Reproduces key aspects of GR by deriving the Einstein Field Equations from first principles within its framework (see Appendix A.2). It also provides explanations for quantum interference phenomena through persistent waves on the spacetime membrane.

- String Theory: Aims to unify all fundamental forces, including gravity, within a quantum framework. It naturally includes GR in the low-energy limit but introduces additional complexities and unobserved dimensions.

- Loop Quantum Gravity: Successfully quantises gravity while preserving the principles of GR. However, it does not inherently unify gravity with the other fundamental forces.

- STM Model: While offering a potentially simpler mathematical framework, it requires further development and refinement to tackle complex phenomena and ensure internal consistency.

- String Theory and LQG: Both have undergone extensive mathematical development, with well-established formalisms and a wealth of literature exploring their implications.

- STM Model: Proposes experiments that could test its predictions within current technological capabilities, such as gravitational wave observations and quantum interference experiments.

- String Theory: Faces challenges in making experimentally testable predictions due to the high energy scales involved.

- Loop Quantum Gravity: While offering some potential observational signatures, such as modifications to the cosmic microwave background or high-energy astrophysical phenomena, these are also difficult to test with current technology.

3.2.5. Conclusion

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Implications for Physics and Cosmology

4.2.1. Unification of Fundamental Forces

4.2.2. Dark Energy and Cosmic Expansion

4.2.3. Black Hole Thermodynamics and Information Preservation

4.3. Limitations

- Experimental Verification: The STM model requires empirical validation through proposed experiments.

- Mathematical Complexity: Further development of mathematical tools may be necessary to explore all implications of the model and to solve complex equations arising from it [5].

- Extension to All Fundamental Interactions: While the STM model successfully incorporates gravitational phenomena and explains certain quantum behaviours, extending the model to fully encompass all fundamental interactions as described by the Standard Model remains an area for further research. However, the independence of QFT and STM forces suggests that the STM model is compatible with the Standard Model, as it does not interfere with the established quantum field theories. The composite photon in the STM model retains characteristics expected by QFT, such as spin-1, polarisation, masslessness, and Lorentz invariance, supporting this compatibility.

4.4. Future Work

- Experimental Tests: Implement the proposed experiments outlined in the appendices to test the model’s predictions and gather empirical evidence.

- Mathematical Refinement: Develop advanced mathematical techniques to solve complex equations and fully explore the model’s implications [5].

- Collaboration and Peer Review: Engage with the scientific community to scrutinise, challenge, and build upon the STM model, fostering collaboration and further exploration.

5. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability

Ethics Approval

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Mathematical Derivations

Appendix A.1. Simplification of the Elastic Wave Equation

A.1.1 Original Elastic Wave Equation

- is the membrane’s mass density.

- T is the membrane’s tension.

- is the intrinsic elastic modulus of the membrane.

- represents local variations in the elastic modulus due to particle oscillations or other perturbations.

- represents any external forces acting on the membrane.

- and are the Laplacian and biharmonic operators, respectively.

A.1.2 Derivation of Modelling Particle Oscillations and Their Effect on the Elastic Modulus

- is the amplitude of the oscillation.

- k is the wave vector.

- is the position vector.

- is the angular frequency of the oscillation.

- The term represents the constant component of the change in the elastic modulus, resulting from the average energy density of the oscillation.

- The term represents the oscillatory component, indicating that varies in space and time due to the particle’s oscillation.

- Local Stiffness Variation: The oscillations of particles cause local variations in the membrane’s stiffness. Regions where the displacement is at a maximum (antinodes) correspond to greater changes in the elastic modulus.

- Wave Propagation Impact: These variations affect how waves propagate through the membrane, influencing phenomena such as interference and diffraction.

- Energy Exchange: The proportionality constant encapsulates the efficiency of energy transfer between the particle oscillations and the membrane’s elastic properties.

A.1.3 Time Averaging

- The time average of the constant term 1 over one period T is 1.

- The time average of the cosine term over one period is zero:

A.1.4 Redefining the Effective Elastic Modulus

A.1.5 Simplifying the Elastic Wave Equation

A.1.6 Relating to the Cosmological Constant

- A Constant Term:

- An Oscillatory Term:

- Time-Averaged Effect: By averaging over time, we capture the constant contribution of particle oscillations to the membrane’s stiffness, which manifests as the cosmological constant in GR.

- Large-Scale Properties: The oscillatory components average out over cosmological timescales, meaning they do not contribute significantly to the large-scale structure of spacetime.

- Vacuum Energy and : The identification of with provides a natural link between the STM model and the cosmological constant problem, offering an explanation for dark energy and the universe’s accelerated expansion.

- Why Time Averaging is Necessary: Since varies over time due to the oscillations, its instantaneous value fluctuates. However, the cumulative effect on spacetime’s large-scale properties depends on the average value.

- Quantum Fluctuations: Time averaging demonstrates how high-frequency quantum fluctuations do not accumulate to affect the macroscopic properties of spacetime, aligning with observations that the cosmological constant is small despite the presence of quantum fluctuations.

Appendix A.2. Derivation of Einstein Field Equations from the STM Model

A.2.1 Elastic Membrane and Spacetime Geometry

- is the Minkowski metric of flat spacetime.

- represents small perturbations due to membrane deformations.

- The displacement field is related to through the strain tensor.

A.2.2 Elastic Energy and Action Principle

A.2.3 Variation of the Action

A.2.4 Deriving the Field Equations

A.2.5 Relating Strain Tensor to Curvature

A.2.6 Arriving at the Einstein Field Equations

- is the Ricci scalar.

- is the cosmological constant, arising from the membrane’s intrinsic properties.

- .

A.2.7 Incorporation of the Cosmological Constant

Appendix A.3. Quantisation in Black Holes and Information Encoding

A.3.1 Modified Schrödinger Equation within Black Holes

- is the gravitational potential inside the black hole.

- represents the elastic correction due to the membrane.

A.3.2 Solving for Quantised Energy Levels

A.3.3 Prevention of Singularity Formation

A.3.4 Information Encoding in Standing Waves

Appendix A.4. Double-Slit Interference Derivation

A.4.1 Introduction

A.4.2 Wave Function Splitting

- : Wave function component passing through slit 1.

- : Wave function component passing through slit 2.

A.4.3 Mathematical Representation of the Wave Functions

- and are the amplitudes of the wave functions after passing through slits 1 and 2, respectively.

- k is the wave number.

- is the angular frequency.

- and are the distances from slits 1 and 2 to the point of observation on the detection screen.

A.4.4 Calculation of the Probability Density

A.4.5 Evaluation of the Cross Terms

A.4.6 Final Expression for the Probability Density

A.4.7 Interpretation of the Interference Pattern

- Constructive Interference: Occurs when , where n is an integer, leading to maxima in .

- Destructive Interference: Occurs when , leading to minima in .

A.4.8 Explanation within the STM Model

- Persistent Waves on the Membrane: The particle’s wave function corresponds to a persistent wave propagating on the spacetime membrane.

- Superposition Principle: The splitting of the wave function at the slits represents the branching of the membrane waves into two coherent components.

- Elastic Properties Enabling Interference: The membrane’s elasticity allows the waves to propagate without loss of coherence, essential for interference to occur.

- Phase Difference Arising from Path Lengths: The difference in distances and translates to a phase difference between the two membrane waves.

- Resulting Interference Pattern: The superposition of the two waves leads to interference, reproducing the observed pattern on the detection screen.

A.4.9 Alignment with Quantum Mechanics

- Wave–Particle Duality: The particle exhibits both wave-like (interference) and particle-like (discrete detections) properties.

- Probability Interpretation: The probability density derived from the wave functions predicts the statistical distribution of particle detections.

- No Contradiction with Observations: The STM model’s explanation is consistent with experimental results, reinforcing its validity.

A.4.10 Implications of the STM Model

- Geometric Interpretation: Provides a geometric basis for quantum interference, attributing it to the behaviour of waves on the spacetime membrane.

- Unification of Concepts: Bridges the gap between quantum mechanics and spacetime geometry, supporting the unification efforts of the STM model.

- Potential for Further Exploration: Encourages the examination of other quantum phenomena within the framework of membrane dynamics.

Appendix A.5. Interaction Between Particles and Mirror Particles

A.5.1 Introduction

A.5.2 Attraction and Repulsion Mechanisms

- Particles and Mirror Antiparticles Attract: This attraction facilitates the transfer of energy into the STM membrane.

- Particles and Mirror Particles Repel: This repulsion promotes the movement of energy out of the STM membrane.

A.5.3 Mathematical Representation of Forces

A.5.4 Energy Exchange with the STM Membrane

- Energy into the Membrane: When particles attract mirror antiparticles, energy is absorbed into the STM membrane, contributing to its homogeneous energy density.

- Energy out of the Membrane: When particles repel mirror particles, energy is released from the STM membrane, presenting as localised mass–energy that affects spacetime curvature.

A.5.5 Balancing of Forces

- Conservation of Energy: The total energy remains constant, with energy dynamically shifting between the particles and the membrane.

- Stability of the Membrane: Prevents runaway effects that could destabilise the spacetime fabric.

Appendix A.6. Derivation of Time Dilation from STM Deformation

A.6.1 Introduction

A.6.2 Metric Tensor and Displacement Field

A.6.3 Time Component of the Metric

A.6.4 Relating Gravitational Potential to Displacement

- is the stress tensor.

- and are Lamé’s first and second parameters, related to the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio .

A.6.5 Deriving Time Dilation

A.6.6 Conclusion

- The perturbation in the metric tensor due to membrane deformation leads to time dilation effects.

- The time dilation experienced in a gravitational field is a direct consequence of the deformation of the spacetime membrane in the STM model.

- This derivation reinforces the correspondence between the STM model and General Relativity, demonstrating the model’s capability to reproduce gravitational phenomena like time dilation.

Appendix B. Proposed Experiments to Test the STM Model

Appendix B.1. Gravitational Wave Detection Through Membrane Oscillations

- Enhanced Interferometers: Modify existing gravitational wave detectors to be sensitive to the predicted oscillation modes.

- Frequency Bands: Focus on detecting higher-order modes that may arise due to the membrane’s elasticity.

- Data Analysis: Compare observed waveforms with predictions from both GR and the STM model.

- Anomalies in Waveforms: Detection of deviations from GR predictions, such as additional oscillations or phase shifts.

- Evidence of Membrane Elasticity: Confirmation of the STM model’s predictions about spacetime elasticity.

Appendix B.2. Quantum Interference Experiments with Extended Path Lengths

- Long-Range Interferometry: Set up double-slit experiments with significantly increased distances between slits and detectors.

- Particle Types: Use particles with longer coherence lengths, such as cold neutrons or atoms.

- Isolation Techniques: Implement advanced isolation methods to minimise decoherence.

- Sustained Interference Patterns: Observation of interference fringes at distances where standard quantum mechanics might predict decoherence.

- Support for STM Predictions: Evidence that the spacetime membrane’s properties enable persistent coherence.

Appendix B.3. Black Hole Information Retrieval via Hawking Radiation Analysis

- Observations of Black Holes: Collect data on Hawking radiation from astrophysical black holes or analog systems (e.g., sonic black holes in condensed matter systems).

- Spectral Analysis: Look for specific patterns or correlations in the radiation spectrum.

- Comparison with Models: Compare observations with predictions from the STM model and standard Hawking radiation theory.

- Information-Carrying Radiation: Identification of non-random patterns suggesting that information is encoded in the radiation.

- Resolution of Information Paradox: Empirical support for the STM model’s solution to the information loss paradox.

Appendix B.4. Testing the Cosmological Constant Through Vacuum Energy Measurements

- Casimir Effect Measurements: Use precise Casimir force experiments between closely spaced plates.

- Advancements in Technology: Employ nanotechnology and cryogenic environments to reduce noise and improve sensitivity.

- Data Comparison: Contrast results with theoretical predictions from the STM model and quantum field theory.

- Alignment with STM Predictions: Measurements of vacuum energy that match the small value implied by the cosmological constant in the STM model.

- Insights into Dark Energy: Improved understanding of the role of vacuum energy in cosmic expansion.

Appendix C. Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Positions

Appendix C.1. Potential Energy Function and Force Derivation

- s is the separation between a particle and its mirror particle.

- is a characteristic wavelength of the STM membrane.

Appendix C.2. Equilibrium Points and Stability

- Stable Equilibrium: Occurs when , which happens at .

- Unstable Equilibrium: Occurs when , which happens at .

Appendix C.3. Physical Interpretation

- Quantisation of Positions: Particles tend to occupy discrete positions corresponding to stable equilibrium points.

- Consistency with Quantum Mechanics: This quantisation arises naturally from the STM model, mirroring the quantised nature of particle states in quantum mechanics.

Appendix D. Additional Mathematical Derivations

Appendix D.1. Modified Klein–Gordon Equation in the STM Model

- The term accounts for higher-order spatial derivatives due to the membrane’s elastic properties.

Appendix D.2. Solution and Implications

- The additional term introduces corrections at high energies or small scales.

- This may lead to observable deviations from standard predictions, particularly at energies approaching the Planck scale.

Appendix E. Implications for High-Energy Physics

Appendix E.1. Predictions for Particle Accelerators

- Deviation in Particle Behaviour: The STM model predicts slight deviations in particle trajectories and energies at high energies due to the elastic properties of spacetime.

- Testing at the LHC: High-energy collisions could reveal discrepancies in particle masses or lifetimes consistent with STM predictions.

Appendix E.2. Quantum Gravity Effects

- Planck Scale Phenomena: The STM model provides a framework to explore quantum gravity effects, potentially observable through precise measurements of particle interactions.

- Unification Efforts: The model contributes to efforts to unify quantum mechanics and gravity by offering testable predictions.

Appendix F. Further Experimental Proposals

Appendix F.1. Testing Lorentz Invariance

- High-Energy Astrophysical Observations: Study cosmic rays and gamma-ray bursts for evidence of Lorentz invariance violations.

- Laboratory Experiments: Use synchrotron radiation facilities to test high-energy particle behaviour.

- Confirmation of Lorentz Invariance at Standard Energies: No violations are expected at accessible energy levels.

- Potential Violations at Extreme Energies: Observations of tiny deviations could support the STM model’s predictions.

Appendix F.2. Observations of Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)

- Analysis of CMB Data: Use data from missions like Planck and future CMB experiments.

- Anisotropy and Polarisation Studies: Look for anomalies or patterns unexplained by standard cosmology.

- Detection of Anomalies: Identifying features that could be attributed to the elastic properties of spacetime.

- Impact on Cosmological Models: Refinement of models of the early universe incorporating the STM framework.

Appendix G. Glossary of Terms and Symbols

- : Density of the STM membrane.

- : Displacement field representing membrane deformations.

- : Intrinsic elastic modulus of the STM membrane.

- : Effective elastic modulus after incorporating time-averaged local variations.

- T: Tension of the STM membrane.

- : Characteristic length scale of the STM model.

- : Einstein tensor representing spacetime curvature.

- : Stress–energy tensor representing matter and energy content.

- : Wave function or scalar field in quantum equations.

- : Effective potential in radial coordinate r.

- ℏ: Reduced Planck constant.

- c: Speed of light in a vacuum.

- G: Newton’s gravitational constant.

- : Angular frequency.

- : Wave vector.

- A: Amplitude of oscillation.

References

- instein, A. (1915). Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin.

- awking, S. W. (1975). Particle Creation by Black Holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3), 199–220.

- ekenstein, J. D. (1973). Black Holes and Entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8), 2333–2346. [CrossRef]

- reen, M., Schwarz, J., & Witten, E. (1987). Superstring Theory. Cambridge University Press.

- ovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- einberg, S. (1989). The Cosmological Constant Problem. Reviews of Modern Physics, 61(1), 1–23.

- horne, K. S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy. W. W. Norton & Company.

- iess, A. G., et al. (1998). Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. The Astronomical Journal, 116(3), 1009–1038. [CrossRef]

- usskind, L. (2008). The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics. Little, Brown.

- eynman, R. P., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (1965). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Addison-Wesley.

- lanck Collaboration. (2018). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).