1. Introduction

Linguistic Landscape studies focus on analyzing signs in public spaces, a subfield of linguistics that has gained increasing recognition since the late 1990s, with evolving methodologies, approaches, and areas of coverage (Gorter and Cenoz 2023; Kallen 2023). In recent decades, globalization has significantly transformed linguistic landscapes around the world, since “Cities around the globe are dealing with complex challenges like rapid expansion, increasing crowdedness, intersecting forms of diversity, and staggering inequality between the rich and the poor” (Verloo and Bertolini 2020, 13); this is leading to increased linguistic hybridization, especially in urban environments. This phenomenon is particularly evident in Colombia, where diverse linguistic influences converge, reflecting the interplay of local identities and global trends. Armenia, the capital of the Quindío department, serves as a compelling case study for examining these dynamics, as its public signage and business names increasingly exhibit a blend of Spanish and English.

Globalization is a term that has gained prominence in recent years due to its versatility and its capacity to serve as a reference point for addressing various aspects of society. Essentially, it encompasses the global interconnectedness that has transformed social life through multiple economic, political, cultural, technological, and social dimensions, both collectively and individually. This phenomenon is not new; rather, it is a continuous process that has intensified over the last century and has evolved through distinct phases, each characterized by unique features (Kumaravadivelu 2008). Eriksen (2014) aligns with this viewpoint, emphasizing that globalization manifests in diverse dimensions and that its rapid expansion in the 21st century is largely attributable to the communication revolution—driven by the development of the Internet and digitalization—alongside new consumption trends and migration patterns that have accelerated since the 1990s.

The connections established through globalization and global cultural exchange have broadened our perception of the world and other cultures. However, despite the continual growth of the population in numerical terms, “the world has become a smaller place” (Ardalan 2017, 31). This statement does not refer to a reduction in physical size but rather to an increased sensitivity toward cultures and the differences or otherness they embody. With globalization, discussions often center around cultural and even linguistic homogeneity, although it is important to note that alternative perspectives advocate for heterogeneity and hybridity (Hassi and Storti 2012).

From the standpoint of homogeneity, convergence is posited, suggesting that one of the repercussions of globalization is the global standardization of culture. This cultural convergence “promotes the possibility that local cultures may be shaped by more powerful cultures or even a global culture” (Hassi and Storti 2012, 8). From this perspective, cultural influence is often viewed as unidirectional, primarily driven by American cultural imperialism, which promotes consumer capitalism and homogenizes cultural aspects such as music, lifestyles, technology, and forms of entertainment (Ardalan 2017). Linguistically, the global status of English as a dominant language has been evident (Martin 2007; Vandenbroucke 2016), potentially impacting the speech forms and language used in public spaces within local communities. This phenomenon has been summarized as a process of Westernization, chiefly propelled by the American entertainment industry (Kumaravadivelu, 2008).

The dominance of English as a global language has been particularly observed in large cosmopolitan cities, where phenomena such as gentrification and the migration of diverse communities have influenced the linguistic practices of their inhabitants, as seen in Japan (Baudinette 2018), Korea (Choi, Tatar, and Kim 2021), Russia (Aristova 2016), and Mexico (Baumgardner 2008; 2007; 2006), among others. However, how does globalization affect the linguistic practices of cities that are not directly influenced by these social phenomena?

The present study aims to explore the linguistic hybridization present in the public signage of Armenia, focusing on the names of commercial establishments. The research is grounded in the sociolinguistic framework that emphasizes the relationship between language use and sociocultural processes. Our analysis employs quantitative methods, particularly Chi-square tests and logistic regressions, to investigate the statistical association between the choice of symbolic language and various contextual factors, such as the location of the establishment and the type of business.

The Pluri-Ethnic Identity of Quindío: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Realities

The Quindío Department was established in 1966, having previously belonged to Caldas, or Viejo Caldas [Old Caldas] ––a department that encompassed territories segmented from Antioquia, Cauca, and Tolima, founded in 1905––. Although it gained autonomy as a department, Quindío could not detach itself from the inherent imagery associated with its predecessor, which assumes that both territories are products of Antioquian colonization; therefore, the identity of its people is linked to being Antioquian in all its dimensions. However, some scholars argue that the reality is much more varied and complex. As Medina (2019, 9) notes, “Old Caldas is a multi-ethnic and multicultural human mosaic in search of its own identity, and not merely an appendix of Antioqueness.” This assertion equally applies to Quindío, as its historical formation reveals the convergence of individuals from different origins: Antioqueños, Caucanos, Santandereanos, Cundiboyacenses, Tolimenses, Nariñenses, and Vallunos.

The configuration of this pluri-ethnic mosaic has gradually been unveiled through the accumulation of various sources that, interwoven, give voice to a history of migration and colonization that had remained silent. For instance, the novel Hombres transplantados (Buitrago 1943) vividly depicts the diverse origins of Quindío's early inhabitants, highlighting not only Antioquians but also Caucanos, Santandereanos, and people from the Cundiboyacense highlands. Historical records from some municipalities in Quindío also confirm this pluri-ethnic configuration. For example, in Salento, it was initially considered a mandatory stop for immigrants traveling from Cartago to Ibagué via the National Road; these individuals were not solely Antioquians but came from all corners of Colombian territory, many of whom settled in the region (Muñoz 1993).

In Calarcá, a varied migration-colonization is evident. Examples of this can be found in the book Calarcá en anécdotas (Jaramillo 1976), which documents the rivalries between Antioquians settled in the municipality and the so-called Orientals (Tolimenses, Cundiboyacenses, and Santandereanos). Regarding the municipality of La Tebaida, it was the coffee boom and the arrival of the train that initially attracted a large contingent of Valluno migrants, followed by Caucanos, Santandereanos, and Boyacenses (Valencia 2016).

In summary, Quindío, like the former Old Caldas, is a territory where transhumance defines the coordinates of its identity, where the establishment of a symbolic capital has yet to be firmly rooted due to the mobile and transitory nature of those who, originating from various regions of Colombian territory, continuously populate and repopulate this young department.

Currently, migratory movements in Quindío are fueled by both internal and foreign human capital. The presence of foreigners in the department is so strong that the local perspective has turned towards them, as they constitute an additional element of the landscape. Consequently, cultural and economic dynamics have transformed to accommodate the needs and preferences of foreigners, a fact that impacts the fragile symbolic capital of Quindío's identity, leaving it vulnerable to globalization processes whose manifestations are evident in the daily life of some municipalities.

Thus, the influence of globalization has added a new layer of complexity to this already rich cultural diversity. A visible aspect of this global influence is the use of English in public spaces. This phenomenon is not yet a sign of gentrification but serves as palpable evidence of globalization's impact and the emblematic functions of language (Blommaert 2010, 29), in which the sign is purely semiotic, not linguistic. In other words, its function is emblematic rather than denotative, serving as a sign that does not convey information but rather possesses a “chic appeal.”

After a brief ethnographic survey of the streets of Armenia, it is not difficult to encounter linguistic borrowings and calques derived from English in various urban contexts: from commercial signs and restaurant menus to signage and cultural events. This linguistic transformation suggests a process of globalization and acculturation, reflecting changes in identity and the symbolic capital of the region.

2. Materials and Methods

To understand the changes occurring in the city of Armenia regarding the use of languages in public spaces, an urban ethnographic approach (Verloo 2020) was employed. This approach allows for the study of the city “from within.” It serves as a tool to analyze the impact of various sociopolitical changes such as segregation, gentrification, migration, and globalization on urban environments, as ethnographic data provide insights into “the process of production of culture, identity, and space or place” (Verloo 2020, 40).

Based on previous studies of linguistic landscapes (Carr 2021; Pastor 2021; Guarín 2024a; 2024b; Hassa and Krajcik 2016) which demonstrated a significant impact of location and type of establishment on language use—specifically, the linguistic code—these two variables were selected as the foundation for this study. The following research questions were formulated:

- (a)

To what extent is English part of the linguistic landscape of Armenia, Quindío?

- (b)

How does location affect the use of the linguistic code in the linguistic landscape of Armenia?

- (c)

In what ways does the type of establishment influence the linguistic code in the city of Armenia?

Data collection was conducted in three areas of the city—see

Figure 1. Zone 1 (points A and B) encompassed Carrera 14 between Calle 21 and Calle 12; a pedestrian boulevard known as

Cielos Abiertos [Open Skies]. This area is recognized for being busy with various food and craft sales points and connects two main parks in the city:

Plaza de Bolívar (point A) and

Parque Sucre (point B). Zone 2 included Carrera 14 from Calle 12 (point B) to Avenida Las Palmas (point C), where various restaurants, clothing stores, two shopping centers, and two universities are located. Finally, Zone 3 comprised Carrera 14 from Avenida Las Palmas (point C) to Calle 10 Norte (point D). This corridor features a variety of cafés, restaurants, health clinics, important parks for the city, and churches.

A total of 498 tokens were collected (N=498): 196 in Zone 1, 88 in Zone 2, and 214 in Zone 3. For the data distribution, the study followed the Variationist Linguistic Landscape Study (VaLLS) methodology (Amos and Soukup 2020), where independent variables are used to measure their impact on another variable, similar to a variationist sociolinguistic study. Previous studies of linguistic landscapes informed the selection of variables. Thus, symbolic language and informative language were treated as dependent variables (see

Figure 2 as an example), while location and type of establishment served as independent variables.

Following the principle of accountability concerning data, which requires the analyst to quantitatively analyze not only the forms of interest but also those that might appear within the same reference domain (Porcar Miralles, Velando Casanova, and Vellón Lahoz 2019), all languages found in the linguistic landscape were captured and recognized as valid tokens. This means that, although our objective is to measure the use of English in the linguistic landscape, every language encountered was collected and included in the corpus of this study.

For data analysis, since all variables were categorical, contingency tables were created, and chi-square tests were conducted to measure the association, impact, and statistical significance of location and type of establishment in relation to language use. Additionally, upon identifying a variable with significant association, logistic regression analysis was performed to measure that variable's predictive capacity. Furthermore, since some guidelines require the inclusion of effect size in research articles (Loerts, Lowie, and Seton 2020, 69), the association values of Cramér’s V were also reported.

In the chi-square tests, the null hypothesis (H₀) posits that no association exists between the categorical variables, indicating that the observed differences in frequency distribution among categories are due to chance. In our study, the null hypothesis (H₀) suggests that neither location nor type of establishment modifies the linguistic code. Conversely, the alternative hypothesis (H₁) would indicate that location or type of establishment does indeed impact and modify the use of languages in the public space of the city of Armenia, meaning there is an association between variables. As is common in studies of this nature, our results will be evaluated based on a significance level (p) of less than 0.05, suggesting sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The data analysis and statistical tests were conducted using JASP (JASP Team 2024), and the graphs were designed using the ggplot package (Wickham 2016) in R.

3. Results

The aim of this study was to analyze the presence and degree of use of English in the linguistic landscape (LL) of Armenia, Colombia, identifying in which contexts and how frequently this language appears in public spaces, and to measure the impact of location and type of establishment on the choice of linguistic codes in public spaces across three zones of the city.

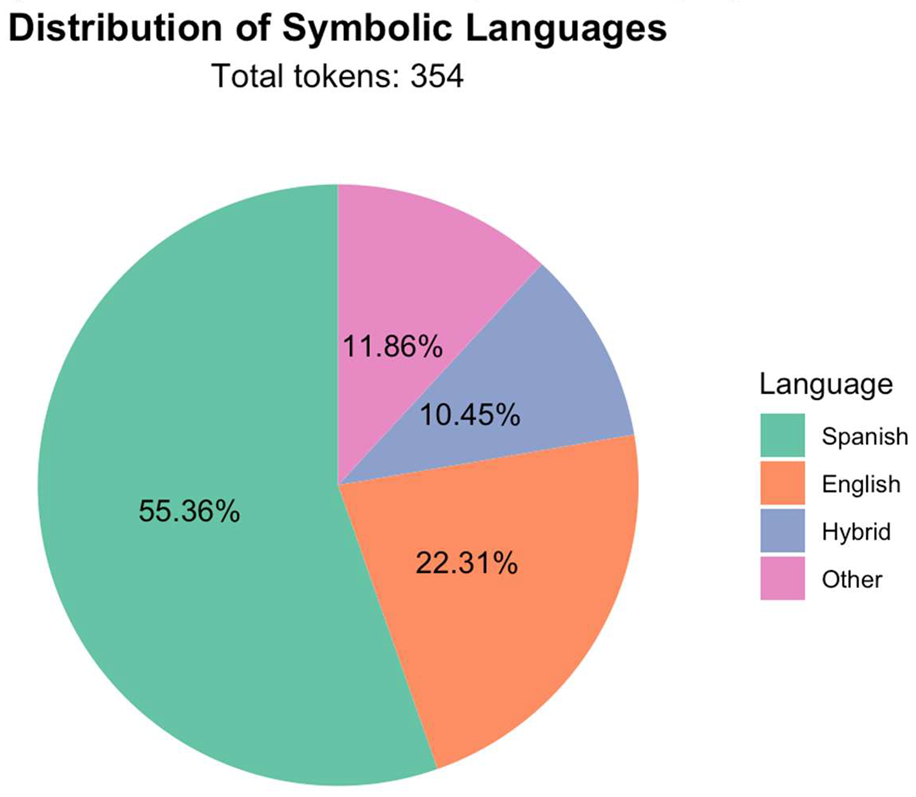

A total of 498 tokens were collected from the LL. After careful review and coding of the data for analysis, the dataset was reduced to 354 tokens, as some signs did not meet the parameters established for this study. Graphic 1 presents the distribution of symbolic languages identified in the dataset, meaning the languages used to name stores or establishments. The distribution of symbolic languages in our data shows that Spanish is the predominant language, representing 55.36% of the total instances. English comes in second place with 22.31%. The “Hybrid” and “Other” categories have similar percentages, with 10.45% and 11.86%, respectively.

Figure 3 presents some examples of English as a symbolic language. Establishments such as “Sport Medical Center,” “Glam Beauty Salon,” “The Grand Bell,” “Phone,” “Sky Blue Spa,” “Chicken Armenia,” “Fish Point,” “Mr. Beer Liquor Store,” and “Beauty Shop Esthetics [sic]” were found.

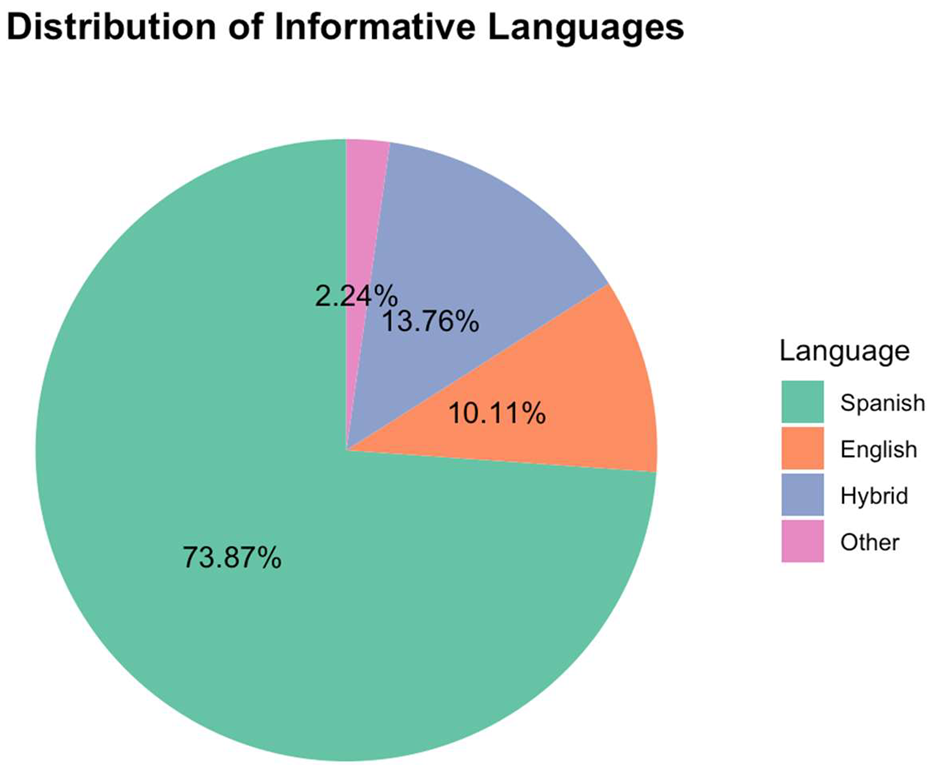

On the other hand, regarding informative languages, Spanish remains the most prevalent linguistic code. However, compared to symbolic languages, its use is much higher, representing 73.87% of the instances. English, on the other hand, is no longer the second most common language, as it was found in only 10.11% of the data. In the advertisements, according to our results, the second most used language was a hybrid of Spanish and English, that is, bilingual ads, which were found in 13.76% of the data, while information in other languages only represented 2.24% ––see Graphic 2.

Graphic 1. Distribution of symbolic languages found in the LL of Armenia

Graphic 2. Distribution of Informative Languages found in the LL of Armenia

These results indicate a strong predominance of Spanish in the context of informative languages, with a significant presence of bilingual or hybrid ads, where information is presented in a mixture of Spanish and English. In

Figure 4, we present examples of stores where English is used to provide information about the products offered, either partially or entirely. Ad A offers, among other items, snacks, smoke, and candies; Ad D offers cafe [sic] and food; and Ad F is presented as a smoke shop. Other ads provide all their information in English, such as sign B, which offers soufth [sic] ice cream; sign C, which offers a cocktail bar and food experience; or sign E, which offers retro games and burgers.

Thus, to answer our first research question (to what extent is English part of the linguistic landscape of Armenia, Quindío?), we can conclude that English has a moderate presence in the city’s linguistic landscape. In terms of store names (symbolic languages), English constitutes 22.31%, indicating a relevant, though not dominant, presence. Therefore, English ranks as the second most common language for symbolic names after Spanish. However, its presence significantly decreases in the realm of informative languages, where it only constitutes 10.11% of the instances observed, mainly because most information is given primarily in Spanish, followed by a hybrid or bilingual form, as exemplified in

Figure 4.

This suggests that while English is visible in the names of establishments, its use is far less frequent in the information about products and services, where Spanish predominates. Additionally, there is a significant percentage of bilingual or hybrid information.

Figure 3 shows some examples of the use of English as a symbolic language, while

Figure 4 presents examples of hybrid ads where morphological elements of both languages are used. Comments on these findings will be presented in the discussion section.

To determine which variables influence the choice of linguistic code in the LL of Armenia, two independent variables were considered: location (in which zone the sign was found) and type of establishment. To measure the impact of these variables on symbolic and informative languages, chi-square tests were conducted, and Cramer’s V was calculated to assess the strength of each association.

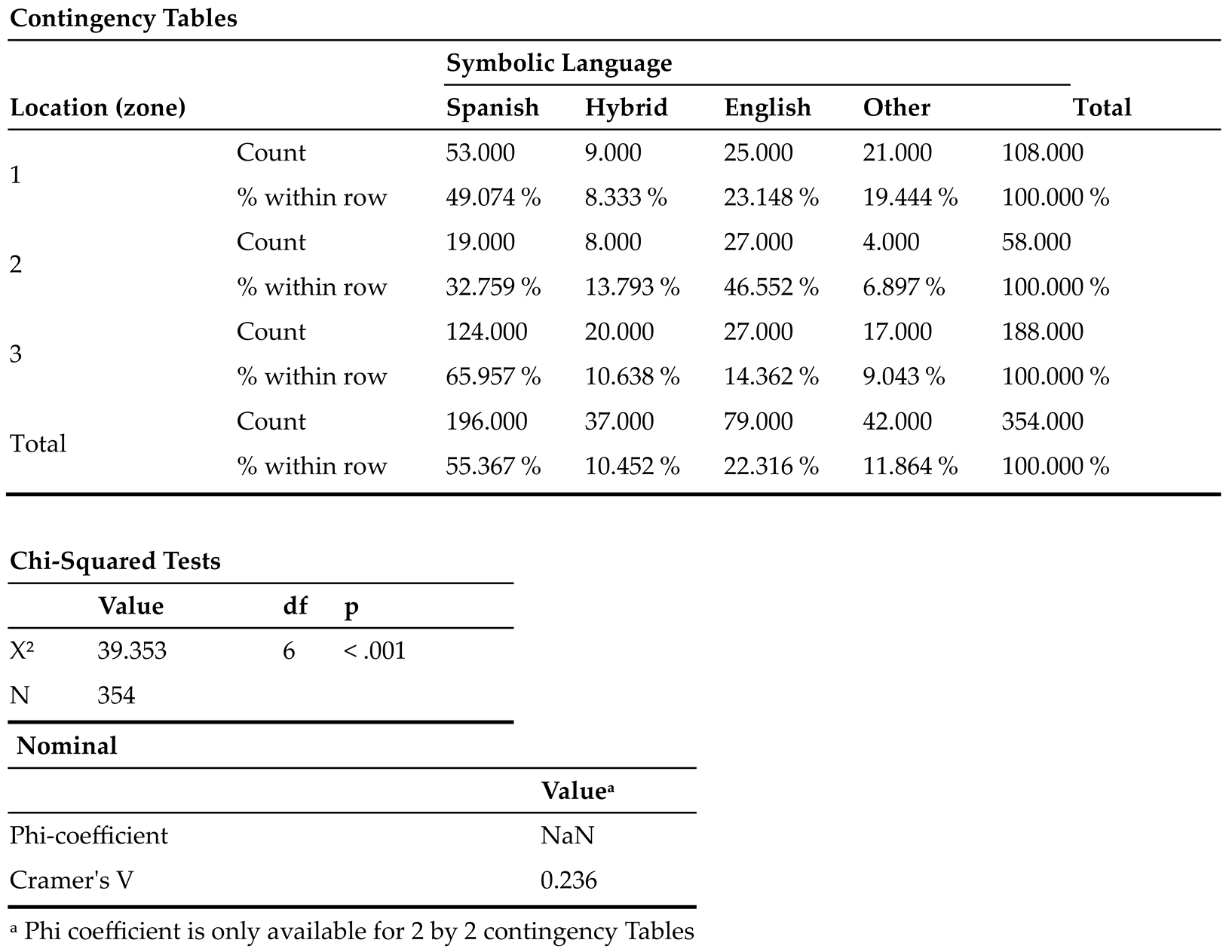

When combining the variables Location and Symbolic Language, our results reveal that there is a statistically significant association between these variables (Χ² = 39.353, df = 6, p < .001, V = 0.236). In zone 1, Spanish is the predominant symbolic language, with 49.07% of cases, followed by English (23.14%), other languages (19.44%), and hybrid languages (8.33%). In zone 2, English predominates, representing 46.55% of the instances, surpassing Spanish-language signs (32.75%), hybrid signs (13.79%), and other languages (6.89%). Finally, in zone 3, Spanish is clearly dominant, with 65.95% of the data, while English has a lower presence (14.36%). Other languages represent 9.04%, and hybrid signs 10.63%.

Table 1.

Contigency Table and Chi-Square test for Symbolic Language and Location.

Table 1.

Contigency Table and Chi-Square test for Symbolic Language and Location.

Since the chi-square test results were statistically significant (p < .001) and a moderate association (V = 0.236) was found between location and symbolic languages, a logistic regression analysis was conducted. The aim was to determine whether location, in addition to being associated with symbolic language, could also be a predictor of its use. However, the results indicated that location alone is not sufficient to predict the use of Spanish or other languages in the public spaces of the city, as reflected by the values of McFadden R² = 0.544 and Nagelkerke R² = 0.678, along with a p-value of 0.062.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression for Symbolic Language and Location.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression for Symbolic Language and Location.

| Model Summary – Symbolic Language |

|---|

| Model |

Deviance |

AIC |

BIC |

df |

Χ² |

p |

McFadden R² |

Nagelkerke R² |

Tjur R² |

Cox & Snell R² |

| H₀ |

|

13.496 |

|

15.496 |

|

15.981 |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| H₁ |

|

6.152 |

|

14.152 |

|

16.091 |

|

8 |

|

7.344 |

|

0.062 |

|

0.544 |

|

0.678 |

|

0.561 |

|

0.458 |

|

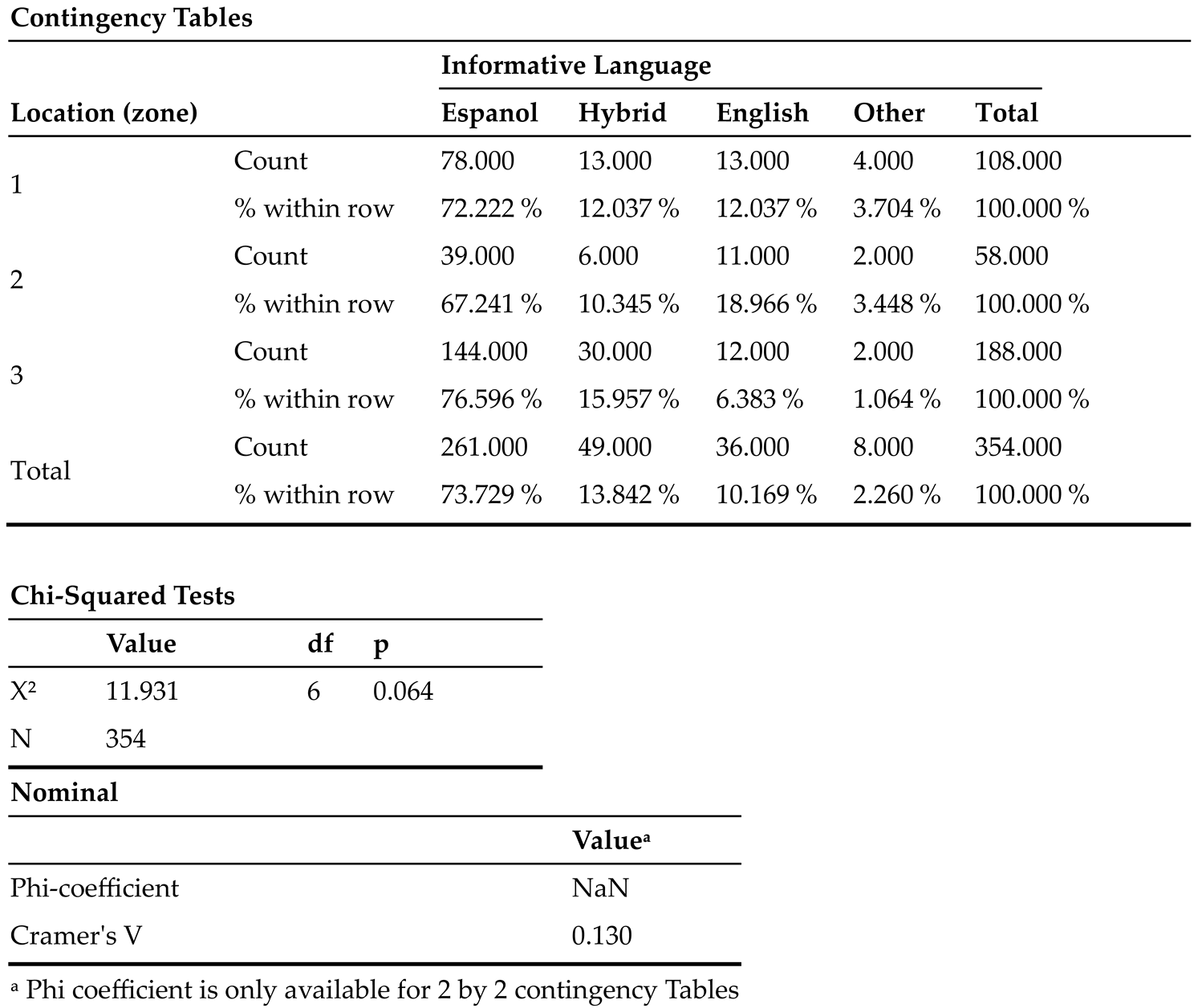

Regarding informative language, our results indicate that there is no association between this variable and location (Χ² = 11.931, df = 6, p = 0.064, V = 0.130). The predominant use of Spanish remains consistent across all three zones, representing 72.22% in zone 1, 67.24% in zone 2, and 76.84% in zone 3. While the use of English and hybrid signs shows slight variations across the zones, these results are not statistically significant. Therefore, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that postulates no association between the variables.

Table 3.

Contingency Table and Chi-Square test for Informative Language and Location.

Table 3.

Contingency Table and Chi-Square test for Informative Language and Location.

Thus, to answer our second research question (to what extent does location affect the use of linguistic codes in the linguistic landscape of Armenia?), it can be stated that location does influence the use of linguistic codes in Armenia’s public spaces, but differently depending on the type of language. There is a significant –though not predictive– association in the use of symbolic languages, which varies between zones, while the use of informative language remains stable and shows no significant association with location. This suggests that although geographic location influences the symbolic language used in public spaces, other factors may account for the stability in the use of informative language.

Another variable considered in this study was the type of establishment. Before conducting statistical analyses, the levels of symbolic and informative language were modified to reduce the degrees of freedom. Instead of considering the variables with the levels of Spanish, English, hybrid, and others, the measurement of the association of establishments was simplified by focusing solely on the use of Spanish versus other languages in general. Thus, the variables were redefined as Spanish vs. others.

The results indicate that there is a statistically significant association between the type of establishment and symbolic language (Χ² = 36.044, df = 12, p < .001, V = 0.319). This suggests that the type of establishment influences the choice of language used in signs and advertisements, reflecting the identity and target market of each business. In contrast, no significant association was found between the establishment type and informative language (Χ² = 20.727, df = 12, p = 0.055, V = 0.242), indicating that the type of establishment does not significantly affect the use of informative language in signs and advertisements. In this case, Spanish continues to be the majority language in informative communication, regardless of the type of business.

Graphic 1. Symbolic Languages and Establishments

These results reveal clear patterns in the use of Spanish versus other languages across different types of establishments. For example, in service establishments, such as payment services, money transfers, or law offices, 80.95% use Spanish. In contrast, in clothing stores, only 34.78% use Spanish, while 65.22% prefer other languages for naming their businesses. Thus, certain types of establishments show a clear preference for Spanish or for other languages. Sectors such as Health (74.24% in Spanish), Services (80.95% in Spanish), and Religion (80% in Spanish) tend to predominantly use Spanish. On the other hand, establishments like Clothing (65.22% in other languages), Entertainment (61.11% in other languages), and Beauty and Spa (53.12% in other languages) show a preference for other languages or for hybrid names where Spanish is combined with English or other languages.

In this way, we answer the third research question (how does the type of establishment influence the linguistic code of the city of Armenia?) by pointing out that the type of establishment presents a significant association with symbolic languages but not with informative languages. The results indicate that sectors such as vehicle sales and repair, clothing stores, entertainment venues, and beauty salons and barbershops show a clear tendency to use languages other than Spanish for naming their businesses. On the other hand, religious establishments, service offices, and home goods stores maintain their names in Spanish, reflecting a preference for this language in contexts involving more formal or traditional communication.

4. Discussion: Cultural Capital and Global Trends

Based on our findings, English holds a significant presence in the names of stores and businesses in the city of Armenia, Colombia, although it is not the dominant language. This presence can be seen as a reflection of the growing social and economic prestige of English in Spanish-speaking urban contexts, as well as the increasing support from Colombia's National Ministry of Education (MEN in Spanish) to promote bilingual and intercultural education (Galindo and Moreno 2019; Galindo and Murillo 2024).

On the other hand, the reach of globalization and the status of English as a prestigious language manifest in a form of “glocalization,” where the language adapts to local contexts. This phenomenon has been observed in different parts of the world (Bohuslavska and Ciprianová 2024; Manan et al. 2017). Although most of Armenia’s population is monolingual, the use of English in store names could be linked to perceptions of modernity, globalization, and economic status. Businesses use English not necessarily for communication but to project a modern, cosmopolitan image. In other words, they employ the language symbolically as a mark of prestige and cultural capital. According to Han and Shang (2024), signs in English in non-English-speaking territories aim to offer a sense of superiority to both residents and tourists who understand the language.

However, as revealed by our data, there is a clear distinction between the use of English as a symbolic language for naming businesses (22.31%) and as an informative language for providing information (10.11%). This suggests that English serves a more symbolic than practical function. As Silverstein (2021) explains, the interpretation of a sign depends on a prior interpretative process, which is influenced by cultural conventions. These conventions guide how we understand the relationship between a sign and its meaning, whether iconically, indexically, or symbolically. In this context, English in the linguistic landscape presents notions of modernity, internationalism, or sophistication rather than serving a purely communicative purpose.

This supports Han and Shang’s (2024) argument that English in the linguistic landscapes of non-English-speaking countries is often limited to business names: “When it comes to signs containing important information, the local people’s dominant language is generally used” (157). In Armenia, English functions purely symbolically rather than functionally. It decorates signs but provides no relevant information for the consumer. According to Blommaert (2010), in a globalized world, semiotic signs have shifted from a denotative (linguistic) function to an emblematic one. Language use in these contexts is “not language but a meaningless design” (31).

The signs shown in

Figure 4 illustrate how English adapts to a new sociolinguistic environment, becoming a local resource. Words like “Burger,” “smoke shop,” “snack,” “liquor store,” and “food” are associated with shared semantic meanings, influenced by globalization, even though these terms are not part of the local dialect repertoire.

For a sociolinguistics of globalization, it is important to observe how globalized language material—such as normative English literacy—enters and becomes adapted to a local sociolinguistic environment and begins to function as a local resource, only loosely connected to its globalized origins. This local resource belongs to a language, English, but it is more productive to see it as it is: as a set of specialized, localized semiotic resources that is related to a local economy of signs and meanings. (Blommaert 2010, 81)

Thus, the English usage reported in this study does not indicate genuine language use but rather reflects the local merchants’ desire to align with global trends and attract customers who associate English with quality, innovation, or modernity, even when their main audience is monolingual Spanish speakers. Furthermore, one of the aspects examined was the hybrid use of symbolic and informative languages. The hybrid signs found in

Figure 5, such as “El Hub” or “Mr. Fruta,” suggest a phenomenon of contact bilingualism, where merchants combine Spanish and English for creativity or differentiation.

This hybridization reflects a broader cultural process where “discrete structures, previously separate, combine to generate new practices” (García Canclini 1995, xxv). In Armenia, combining English and Spanish in business names creates new forms of communication and meaning, driven by globalization and intercultural contact. The coexistence and blending of languages, as observed in previous linguistic landscape studies (Cenoz and Gorter 2006; Fernández Juncal 2020), highlights how languages interact and influence each other in urban settings like Armenia.

Names like “King Presas,” “Big Presas,” “Mundo Bags,” or “The Kitchen Valluno” use morphological elements from two different languages — Spanish and English — in a single linguistic unit. These examples demonstrate how sociocultural and sociolinguistic processes of hybridization work and how new forms (in this case, business names) are generated by combining elements originally from different linguistic systems. In Armenia, English and Spanish elements intermingle, creating a new space for communication and meaning. Globalization and intercultural contact generate not only the coexistence of languages — as seen in previous studies on the linguistic landscape (Cenoz and Gorter 2006; Fernández Juncal 2020; Restrepo-Ramos 2024; Guarín 2024a)— but also their blending into hybrid forms, particularly visible in urban contexts like Armenia.

Following the ecological approach to linguistic evolution — ecolinguistics (Haugen 1972; Mufwene 2001)— these seemingly “discrete” languages (Spanish and English) are themselves the result of previous hybridizations. Thus, Armenia's linguistic landscape highlights the interconnectedness of languages and the continuous processes of linguistic and cultural exchange driven by globalization, leading to greater cultural exposure through digital media, tourism, or commerce. This is evident, for instance, in the annual diagnoses of the tourism situation in the Quindío department. The department receives close to one million tourists each year, about 9% of whom are foreigners. This percentage comes from measurements conducted by the Tourism Observatory from early 2016 to early 2020 (Gobernación del Quindío 2021, 15). This data is a significant indication of linguistic and cultural contact that begins to take shape in various forms of hybridization.

In this way, although bilingualism is limited, hoteliers, business owners, and tourism agents are partially familiar with English, which allows for the creation of hybrid texts that combine elements from both languages. This hybridization could also be seen as a manifestation of local linguistic creativity, particularly reflecting the role of younger generations, who, according to García Canclini (2017), are redistributing local creativity and incorporating English into Spanish without needing full proficiency in the language:

Even those who have not completed university education have at their disposal economic, school and family resources, a basic knowledge of English and personal IT equipment which enable them to consistently access programmes and complex digital services. Digital communication is at the core of their daily lives. (García Canclini 2017, 245)

Regarding location, this variable was found to be significant for the distribution of symbolic languages, suggesting that the language chosen for the names of establishments (Spanish, English, or others) varies considerably depending on the area of the city. These results align with previous work that shows how languages in public spaces reflect the social and cultural dynamics of a territory (Ben-Rafael et al. 2006; Landry and Bourhis 1997). The variation by zones found in our study suggests that the linguistic and cultural identity of the establishments changes based on socioeconomic and demographic factors. More commercial areas or those with higher tourist traffic may use English more intensively as part of a branding strategy aimed at attracting an audience that associates English with status and globalization.

Zone 2 appears to confirm this assertion, as the use of English as a symbolic language ranks first at 46.55%. In this part of the city, there are establishments focused on technology consumption, entertainment, education, health, beauty, and the sale of food and clothing. Notably, the presence of the Unicentro shopping center (one of the most visited in the city), the private university La Gran Colombia, and the English-language academy American School Way stands out because many establishments around these sites have names (symbolic language) in English or hybrid forms; for example, “Gloria’s designer clothes,” “crepes & sandwich,” “natural food plaza,” “sports mart,” “happy, clínica detal,” “coffea, café bar,” etc. It appears that the commercial and cultural dynamics of the area are marked by these three centers of interest, which radiate a status where English fits perfectly and becomes a sort of symbolic requirement for other establishments. It should also be considered that a predominantly young audience frequents this area, educated and entertained, with good economic prospects, integrating multiple digital practices into their lives, where the presence of English is constant. Perhaps these particularities help us understand the relevance of English in this area more than in others.

In contrast, in Zones 1 and 3, where Spanish is clearly dominant (49.07% and 65.95%, respectively), it is likely that businesses cater to a predominantly local and monolingual clientele, making the use of English less frequent or necessary. Zone 1 is characterized by a high presence of establishments focused on selling clothing, accessories, shoes, bags, and perfumes, resulting in a significant presence of English in these businesses (23.14%), although not more than Spanish. This area also allows for naming these businesses in other languages, such as French in “Caché” and “Fraiche,” which evoke a different kind of prestige ––the European influence that was more pronounced in the first half of the 20th century in Colombia––, as well as in names that differ from English and Spanish, such as “aka,” “DIBOUT,” and “Batuku,” which contribute to the “other” category, whose representation is 19.44%.

Additionally, there are many food-related businesses in this zone –restaurants, cafes– whose symbolic language is primarily Spanish; for example, “Superior,” “Riquísimas arepas de queso,” “Don chicharrón,” “Del gordo,” “Torito al carbón,” “Magangué,” “La Estancia,” “La casa del pandebono,” “Alpike,” “Luma pan,” “La plaza del café,” “Mi buñuelón,” etc. These establishments offer typical foods of the region, so it would not make much sense to promote them in a language other than Spanish. This is one of the reasons that motivate a greater presence of Spanish in Zone 1 than in Zone 2. In the latter, many establishments promote foreign foods (crepes, sandwiches, panzerotti, oriental food, vegetarian food, fast food), which aligns with the type of social and cultural dynamics referred to in the previous paragraph.

The greater presence of Spanish in Zone 3 is justified because its social and cultural dynamics are shaped by establishments that provide health and body care services for the citizens of Armenia and nearby municipalities. Here, there are Health Promotion Entities –Known in Colombian Spanish as EPS–, clinics, aesthetic centers, and pharmacies, the majority of which have their advertisements in Spanish since it wouldn’t make much sense to offer these basic care services in another language. It is well known by all residents of Quindío that visiting these places requires investing many hours, so to support such activities, there is a wide variety of food establishments with diverse offerings. Since those frequenting this area are from the region, it makes sense for the establishments to use Spanish to promote themselves. Below are some examples of what has been mentioned. For health and body care: “Doctorpies,” “Maicol Gallo (ortodoncia),” “De todo para la piel,” “Rostros y figuras,” “Mor, salón de belleza”; for food establishments in the area: “La tusa (Arepa e’chócolo),” “La huerta,” “La colinita (restaurant),” “Donde el tocayo,” “Mi perro.”

Finally, our second variable to study was the type of establishment. The results of the statistical analysis showed a significant association between this variable and the symbolic language (p < .001). In more traditional or formal sectors such as Services (80.95% in Spanish), Health (74.24% in Spanish), and Religion (80% in Spanish), the use of Spanish is predominant. This reflects the social function and the need to maintain closer and more comprehensible communication for the local community, which predominantly speaks Spanish.

In contrast to previous studies, in which religious temples are an important part of multilingualism in cities with significant migration patterns (Blommaert 2013; Guarín 2024a), religious temples in Armenia do not present this phenomenon. This suggests that, although there have been migration patterns toward Colombia in the last ten years (Ordóñez and Ramírez Arcos 2019), the contact that occurs is interdialectal rather than multilingual. That is, the people arriving seeking refuge in Colombia are native Spanish speakers, so the use of different languages that address a broader diaspora is not necessary. The cases of bilingualism in our corpus point more toward the international nature of these religious institutions, which use English emblematically or identitarily to show their international affiliation, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

In contrast, in sectors oriented towards consumption and fashion, such as Clothing (65.22% in other languages) and Entertainment (61.11% in other languages), there is a clear preference for languages other than Spanish, particularly English. This can be explained by the attempts of these establishments to connect with global trends, project modernity, and attract a younger or more cosmopolitan audience as part of their branding strategy, in which the use of English or other languages like Italian or French is associated with ideas of authenticity or exclusivity, potentially attracting consumers who view the use of these languages as a sign of prestige.

Following Bourdieu's (1993) principles, the use of other languages in certain types of establishments, and their variation by areas in the city of Armenia, can be interpreted as linguistic capital. English, as a global language, seems to confer a certain prestige or symbolic capital to businesses, especially in sectors like technology, fashion, entertainment, and gastronomy. According to Schirato and Roberts (2020), symbolic power is exercised through the valuation, acquisition, assessment, and exchange of cultural capital (knowledge, skills, education, etc.), a process that reflects and reinforces social hierarchies. In turn, symbolic capital is “a form of meta-capital that equates to cultural capital recognized as such and, by extension, a form of status that helps establish and determine regimes of capital within cultural fields” (198). In this regard, the use of English in Armenia can be interpreted as a type of cultural symbolic capital that seeks recognition through distinction.

5. Conclusions

Through our exploration of the LL of Armenia, Colombia, we have shed light on the impact of globalization on the use of Spanish and English in public signage, particularly in business names. Our findings aim to add to the literature of the sociolinguistics of globalization and to our understanding of linguistic hybridization, cultural identity, and social dynamics.

The study was guided by three primary research questions: the extent to which English is part of the linguistic landscape of Armenia, how location affects language choice, and how the type of establishment influences language use. These questions were addressed through a quantitative methodology, employing Chi-square tests and logistic regression to analyze the relationship between symbolic language choice and variables such as location and type of establishment.

The analysis revealed several significant findings. On the one hand, there was a statistically significant association between location and language choice (Χ² = 39.353, p <.001), with commercial zones having high tourist traffic, such as Zone 2, showing a pronounced preference for English (46.55%). This reflects branding strategies aimed at attracting a younger, cosmopolitan audience. Similarly, the type of establishment also significantly influenced language use. Traditional sectors like health services (74.24% in Spanish) and religious institutions (80% in Spanish) predominantly used Spanish, emphasizing the community's need for accessible communication.

On the other hand, we highlighted the presence of hybrid names, indicating a blending of languages, particularly in the most commercial areas. This hybridization serves as both a reflection and reinforcement of cultural identity and social hierarchies. At the same time, English functions as symbolic capital, enhancing the prestige and appeal of commercial establishments. This phenomenon is emblematic rather than denotative, possessing a "chic appeal" that reflects the influence of globalization on local cultural dynamics.

With our study we underscore the importance of location and type of establishment in shaping the linguistic landscape of urban environments and aim to support the notion that linguistic hybridization is a complex process influenced by both local identities and global trends. Furthermore, our study emphasizes that Quindío's pluri-ethnic and multicultural identity is further complicated by globalization. The use of English in public spaces is not a sign of gentrification but rather a manifestation of globalization's impact, adding a new layer of complexity to the region's cultural diversity.

Drawing from our sociolinguistic ethnographic approach, in this paper we aim to highlight the relationship between language use and sociocultural processes, demonstrating how language shapes and is shaped by social dynamics within urban landscapes, particularly in the context of globalization. Finally, we argue that ––in Armenia, Colombia–– English serves as symbolic capital, influencing social hierarchies and cultural identity within the urban landscape of the city. This symbolic function of language is crucial in understanding how globalization affects local language practices.

Future studies could further explore the dynamics of linguistic hybridization in other urban environments, particularly in regions with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Investigating the perceptions of local residents and business owners regarding the use of English in public signage could provide additional insights into the social and cultural implications of linguistic hybridization. Moreover, a longitudinal study could track changes in the linguistic landscape over time, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how globalization continues to shape local language practices.

Supplementary Materials

In alignment with ethical procedures in academic research, all data and corpus compiled for this study are available for exploration and use. Interested researchers can obtain access by contacting the corresponding author of this paper via email.

Author Contributions

[blinded for peer review]

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data for the reported results in this article are available in an Excel sheet hosted on Overdrive. This dataset contains the information analyzed during the study and is open for public scrutiny. Access to the dataset is facilitated through contacting the main author for further inquiries or clarifications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amos, H. William, and Barbara Soukup. 2020. “Quantitative 2.0: Toward Variationist Linguistic Landscape Study (VaLLS) and a Standard Canon of LL Variables.” In Reterritorializing Linguistic Landscapes: Questioning Boundaries and Opening Spaces, edited by David Malinowski and Stefania Tufi, 56–76. Advances in Sociolinguistics. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Ardalan, Kavous. 2017. Understanding Globalization. A Multi-Dimensional Approach. Routledge.

- Aristova, Nataliya. 2016. “Rethinking Cultural Identities in the Context of Globalization: Linguistic Landscape of Kazan, Russia, as an Emerging Global City.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 236:153–60. [CrossRef]

- Baudinette, Thomas. 2018. “Cosmopolitan English, Traditional Japanese: Reading Language Desire into the Signage of Tokyo’s Gay District.” Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal 4 (3): 238–56. [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, Robert J. 2006. “The Appeal of English in Mexican Commerce.” World Englishes 25 (2): 251–66. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2007. “English in Mexican Product Branding.” In Seeking Identity: Language in Society, edited by Nancy M. Antrim, 66–80. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishers.

- ———. 2008. “The Use of English in Advertising in Mexican Print Media.” Journal of Creative Communications 3 (1): 23–48. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Rafael, Eliezer, Elana Shohamy, Muhammad Hasan Amara, and Nira Trumper-Hecht. 2006. “Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 7–30. [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- ———. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Critical Language and Literacy Studies 18. Bristol ; Buffalo: Multilingual Matters.

- Bohuslavska, Olha, and Elena Ciprianová. 2024. “English in the Slovak Glocalized Urban Space: A Study of the English Language and the Processes of Glocalization in the Linguistic Landscape of Bratislava.” English Today 40 (1): 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. Language and Symbolic Power. Translated by Gyno Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Harvard University Press.

- Carr, Jhonni Rochelle Charisse. 2021. “Reframing the Question of Correlation between the Local Linguistic Population and Urban Signage: The Case of Spanish in the Los Angeles Linguistic Landscape.” In Linguistic Landscape in the Spanish-Speaking World, edited by Patricia Gubitosi and Michelle F. Ramos Pellicia, 35:239–66. Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. John Benjamins. [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2006. “Linguistic Landscape and Minority Languages.” In Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism, edited by Durk Gorter.

- Choi, Jinsook, Bradley Tatar, and Jeongyeon Kim. 2021. “Bilingual Signs at an ‘English Only’ Korean University: Place-Making and ‘Global’ Space in Higher Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24 (9): 1431–44. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, Thomas Hylland. 2014. Globalization: The Key Concepts. 2nd ed. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Fernández Juncal, Carmen. 2020. “Funcionalidad y convivencia del español y el vasco en el paisaje lingüístico de Bilbao.” Íkala 25 (3): 713–29. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, Angelmiro, and Lina Maria Moreno. 2019. “Educación Bilingüe (Españolinglés) En Tres Instituciones Educativas Públicas Del Quindío, Colombia: Estudio de Caso.” Lenguaje 47 (2S): 648–84. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, Angelmiro, and Andrés Felipe Murillo. 2024. “Implementación del Programa Integral de Bilingüismo Quindío Bilingüe y Competitivo: Percepciones de actores intervinientes.” Lenguaje 52 (1). [CrossRef]

- García Canclini, Néstor. 1995. Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity. University of Minnesota Press.

- ———. 2017. “Urban Spaces and Networks: Young People’s Creativity.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 20 (3): 241–52. [CrossRef]

- Gobernación del Quindío. 2021. “Diagnóstico de La Situación Turística Del Departamento Del Quindío.” https://www.quindio.gov.co/home/docs/items/item_100/Plan_de_Turismo/Diagnostico_PET_1.pdf.

- Gorter, Durk, and Jasone Cenoz. 2023. A Panorama of Linguistic Landscape Studies. Multilingual Matters. https://www.multilingual-matters.com/page/detail/?k=9781800417151.

- Guarín, Daniel. 2024a. “From Bilingualism to Multilingualism: Mapping Language Dynamics in the Linguistic Landscape of Hispanic Philadelphia.” Languages 9 (4): 1–23. [CrossRef]

- ———. 2024b. “Pronominal Address in the Linguistic Landscape of Hispanic Philadelphia: Variation and Accommodation of Tú and Usted in Written Signs.” Language, Culture and Society 6 (1). [CrossRef]

- Han, Yanmei, and Guowen Shang. 2024. The Linguistic Landscape in China: Commodification, Image Construction, Contestations and Negotiations. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Hassa, Samira, and Chelsea Krajcik. 2016. “‘Un Peso, Mami!’ Linguistic Landscape and Transnationalism Discourses in Washington Heights, New York City.” Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal 2 (2): 157–81. [CrossRef]

- Hassi, Abderrahman, and Giovanna Storti. 2012. “Globalization and Culture: The Three H Scenarios.” In Globalization - Approaches to Diversity, edited by Hector Cuadra-Montiel. InTech. 10.5772/45655.

- Haugen, Einar. 1972. The Ecology of Language. Essays by Einar Haugen. Stanford University Press.

- JASP Team. 2024. “JASP.” https://jasp-stats.org.

- Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2023. Linguistic Landscapes: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Kumaravadivelu, B. 2008. Cultural Globalization and Language Education. Yale University.

- Landry, Rodrigue, and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. [CrossRef]

- Loerts, Hanneke, Wander Lowie, and Bregtje Seton. 2020. Essential Statistics for Applied Linguistics. 2nd ed. Red Globe Press.

- Manan, Syed Abdul, Maya Khemlani David, Francisco Perlas Dumanig, and Liaquat Ali Channa. 2017. “The Glocalization of English in the Pakistan Linguistic Landscape.” World Englishes 36 (4): 645–65. [CrossRef]

- Martin, Elizabeth. 2007. “‘Frenglish’ for Sale: Multilingual Discourses for Addressing Today’s Global Consumer.” World Englishes 26 (2): 170–88. [CrossRef]

- Mufwene, Salikoko. 2001. The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact. Cambridge University Press.

- Ordóñez, Juan Thomas, and Hugo Eduardo Ramírez Arcos. 2019. “At the Crossroads of Uncertainty: Venezuelan Migration to Colombia.” Journal of Latin American Geography 18 (2): 158–64. [CrossRef]

- Pastor, Alberto. 2021. “Ethnolinguistic Vitality and Linguistic Landscape: The Status of Spanish in Dallas, TX.” In Linguistic Landscape in the Spanish-Speaking World, edited by Patricia Gubitosi and Michelle F. Ramos Pellicia, 35:73–104. Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. John Benjamins. [CrossRef]

- Porcar Miralles, Margarita, Mónica Velando Casanova, and Javier Vellón Lahoz. 2019. Sociolingüística Histórica Del Español: Tras Las Huellas de La Variación y El Cambio Lingüístico a Través de Textos de Inmediatez Comunicativa. Vol. 41. Lengua y Sociedad En El Mundo Hispánico 41. Iberoamericana / Vervuert.

- Restrepo-Ramos, Falcon. 2024. “Contrastive Language Policies: A Comparison of Two Multilingual Linguistic Landscapes Where Spanish Coexists with Regional Minority Languages.” International Journal of Multilingualism 21 (2): 906–31. [CrossRef]

- Schirato, Tony, and Mary Roberts. 2020. Bourdieu: A Critical Introduction. Routledge.

- Vandenbroucke, Mieke. 2016. “Socio-Economic Stratification of English in Globalized Landscapes: A Market-Oriented Perspective.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 20 (1): 86–108. [CrossRef]

- Verloo, Nanke. 2020. “Urban Ethnography and Participant Observations: Studying the City from Within.” In Seeing the City: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Study of the Urban, edited by Nanke Verloo and Luca Bertolini, 37–55. Amsterdam University Press. https://www.aup.nl/en/book/9789463728942.

- Verloo, Nanke, and Luca Bertolini. 2020. “Introduction.” In Seeing the City: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Study of the Urban, edited by Nanke Verloo and Luca Bertolini, 12–21. Amsterdam University Press.

- Wickham, Hadley. 2016. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Second edition. Use R! Switzerland: Springer. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).