Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Station, Methods, Instruments, and Datasets

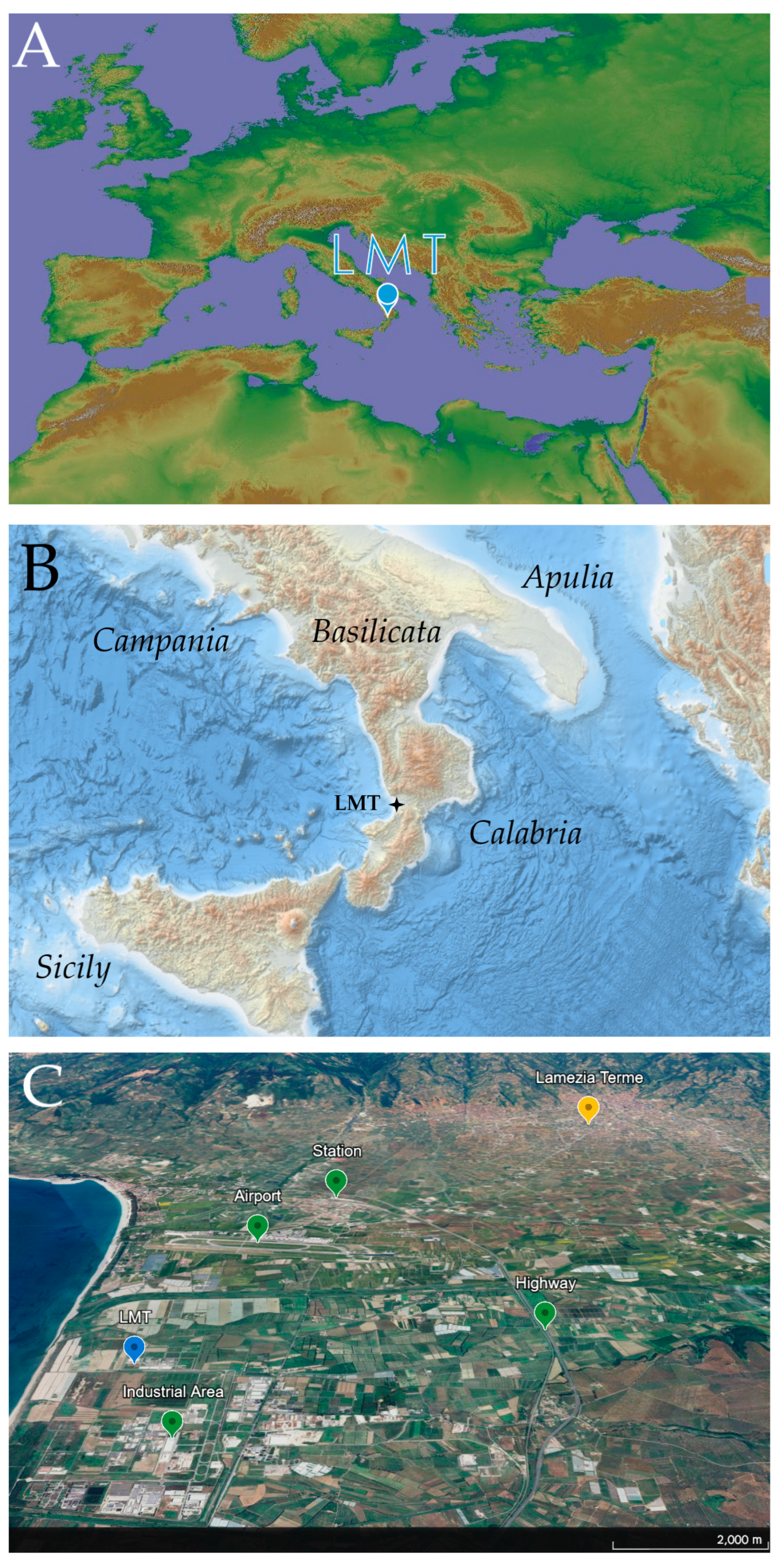

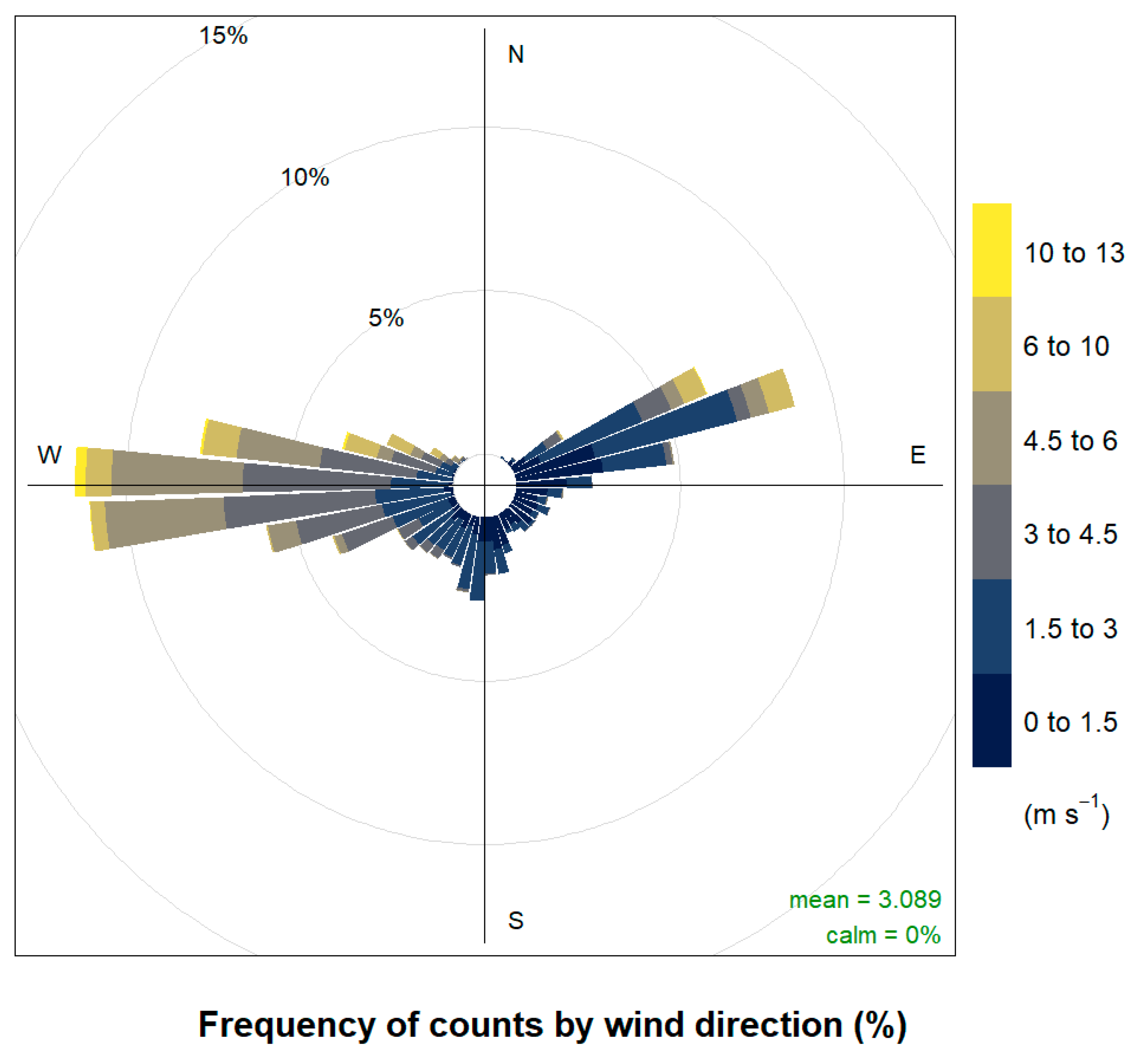

2.1. The Observation Site and Its Characteristics

2.2. Instruments, Methodologies, and Datasets

3. Results

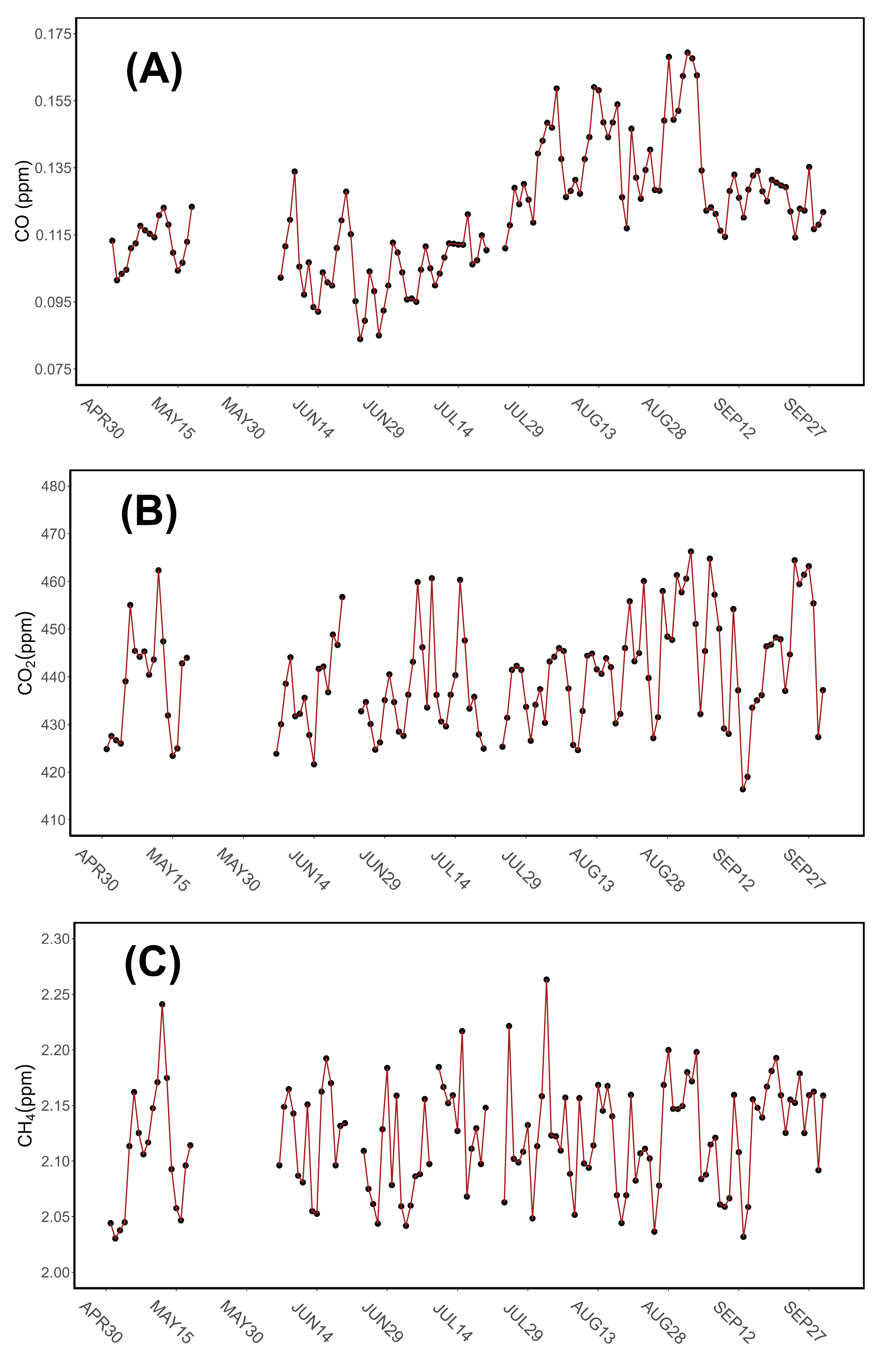

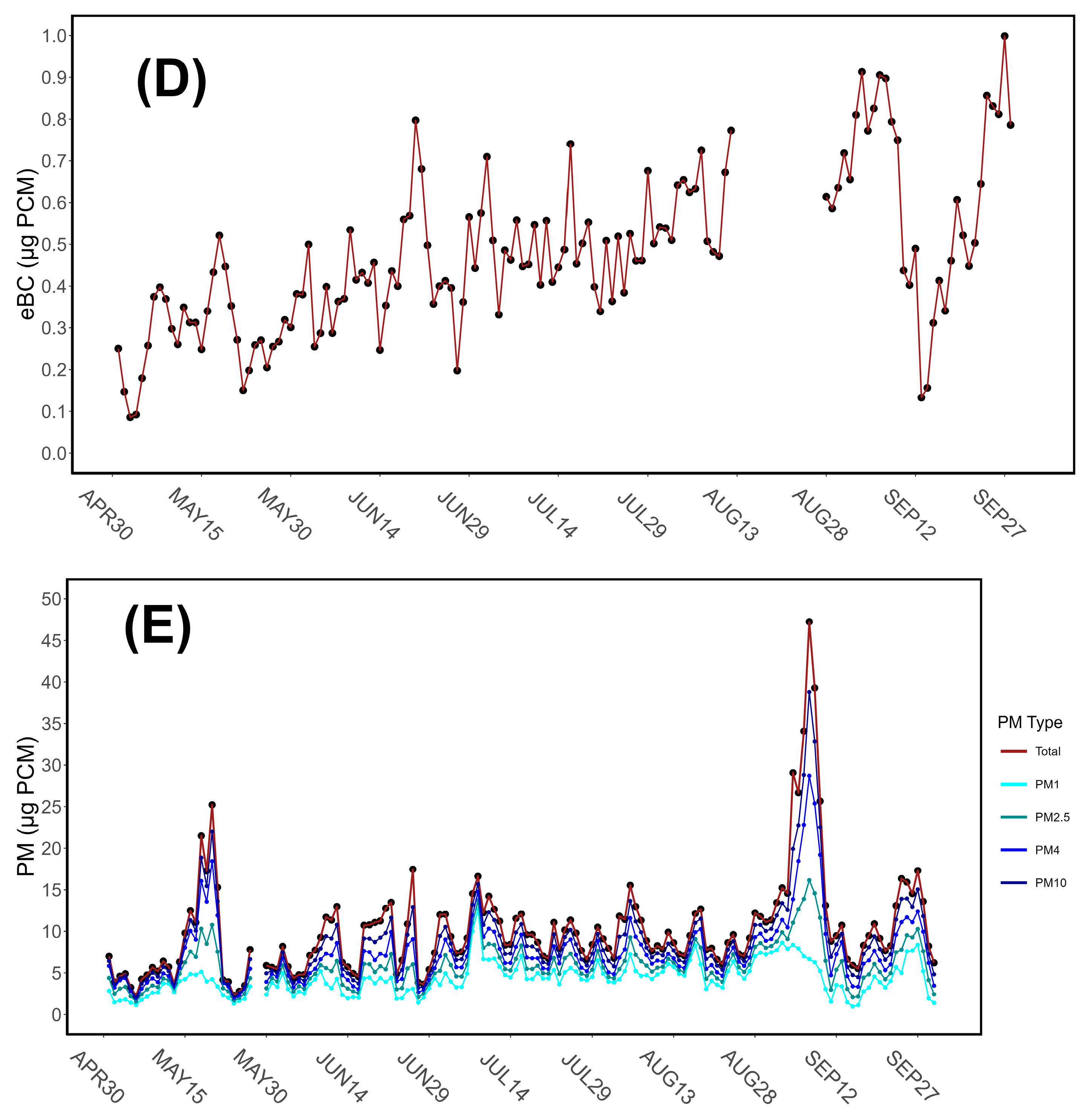

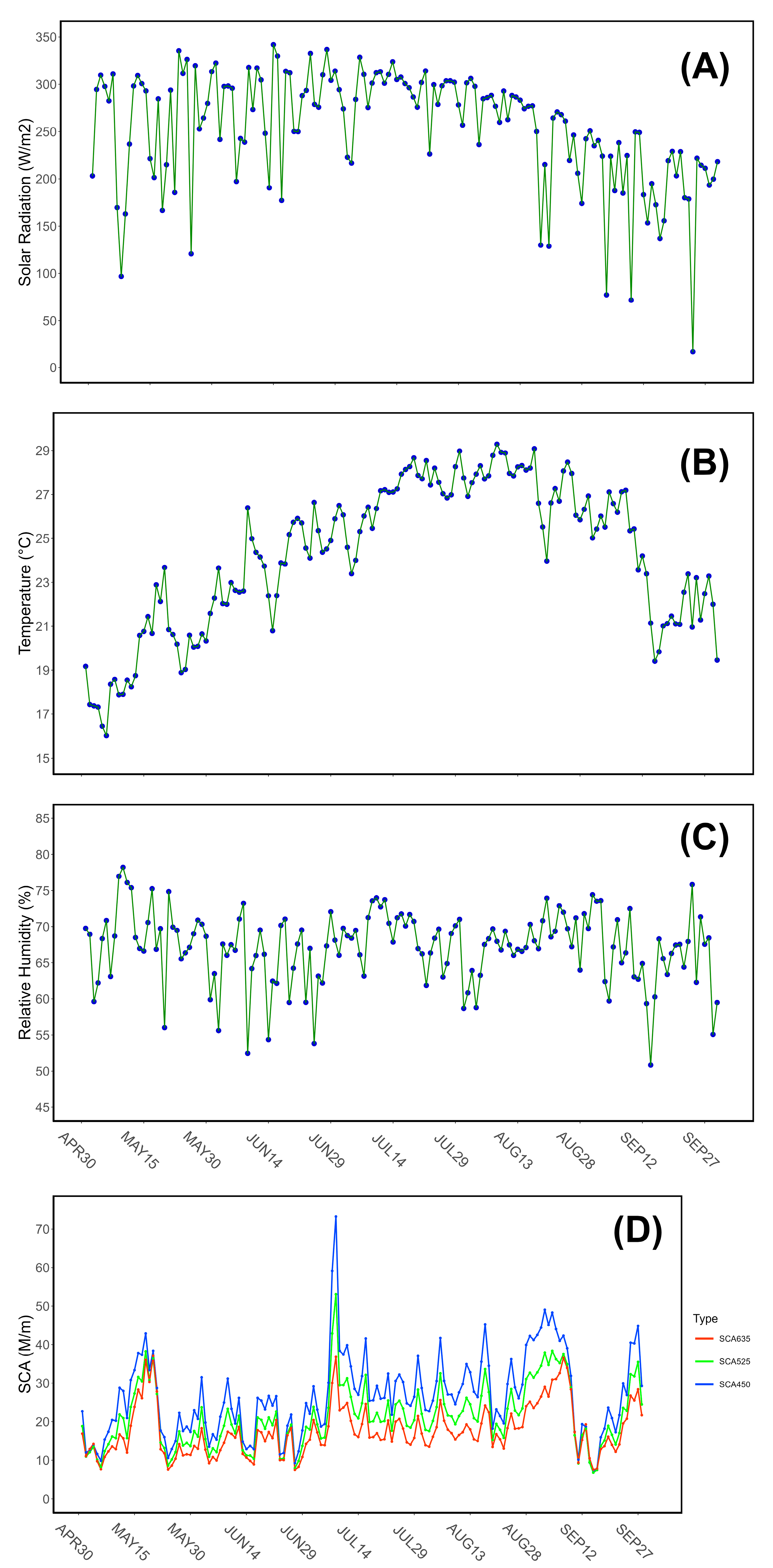

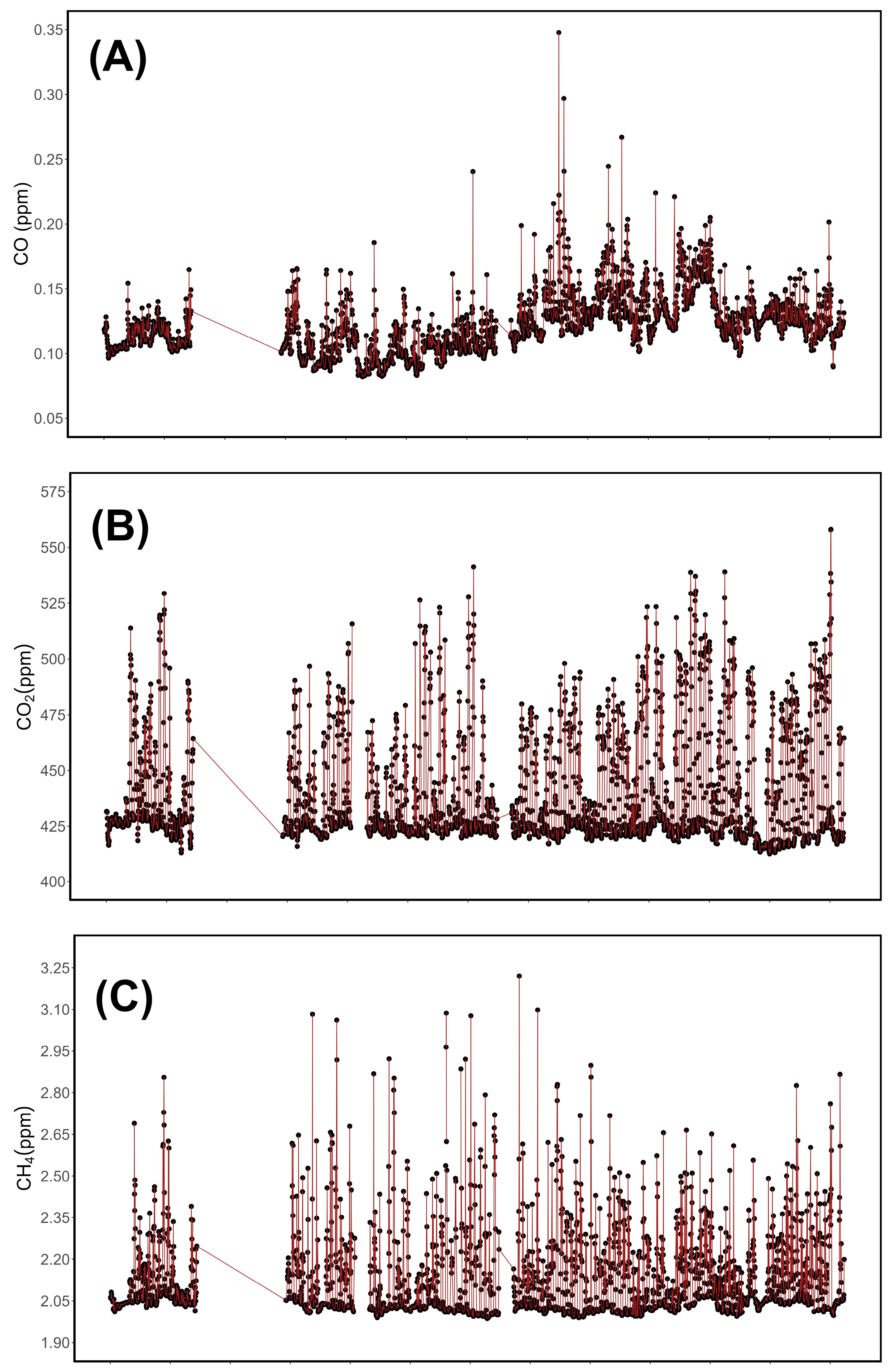

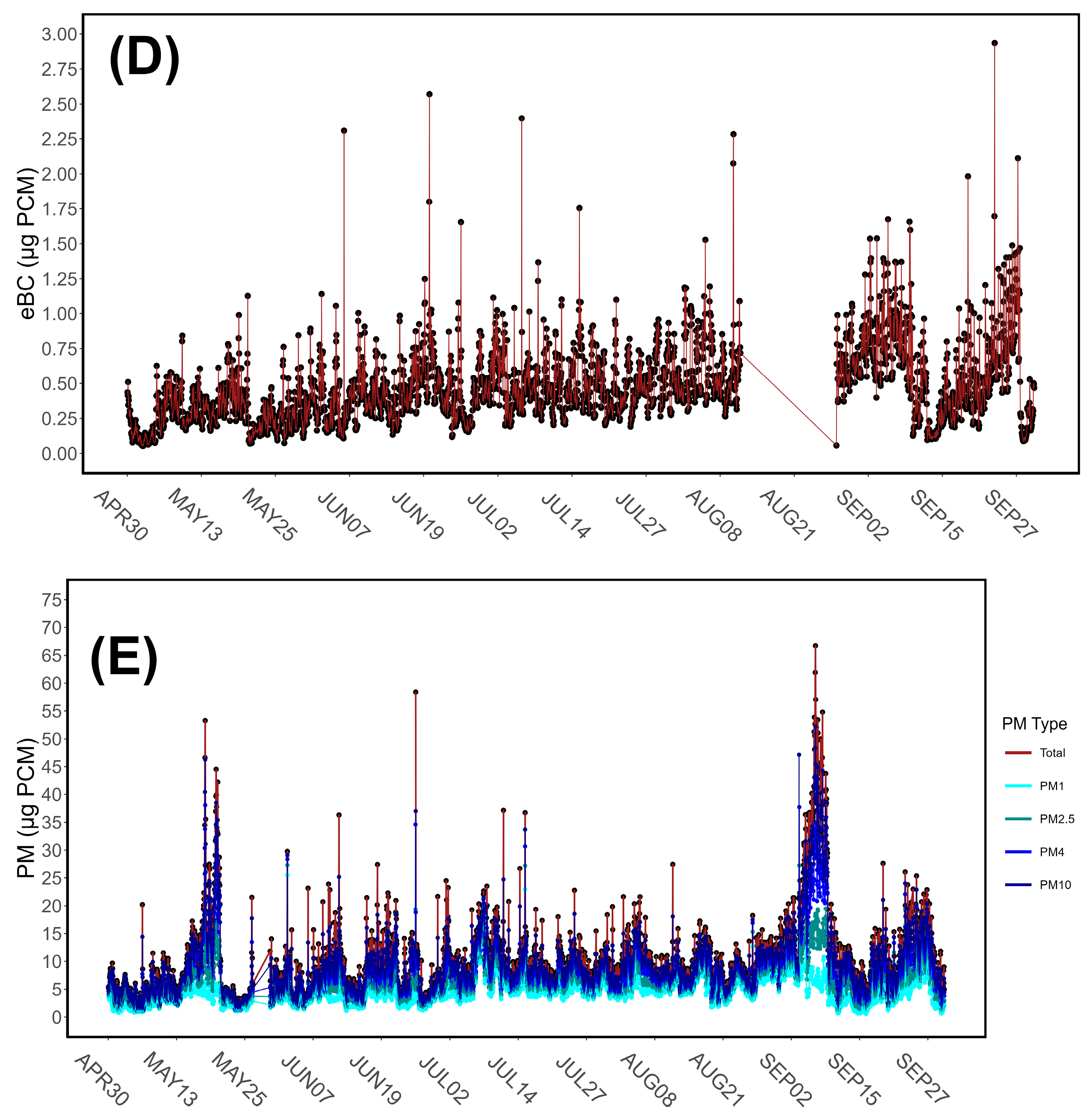

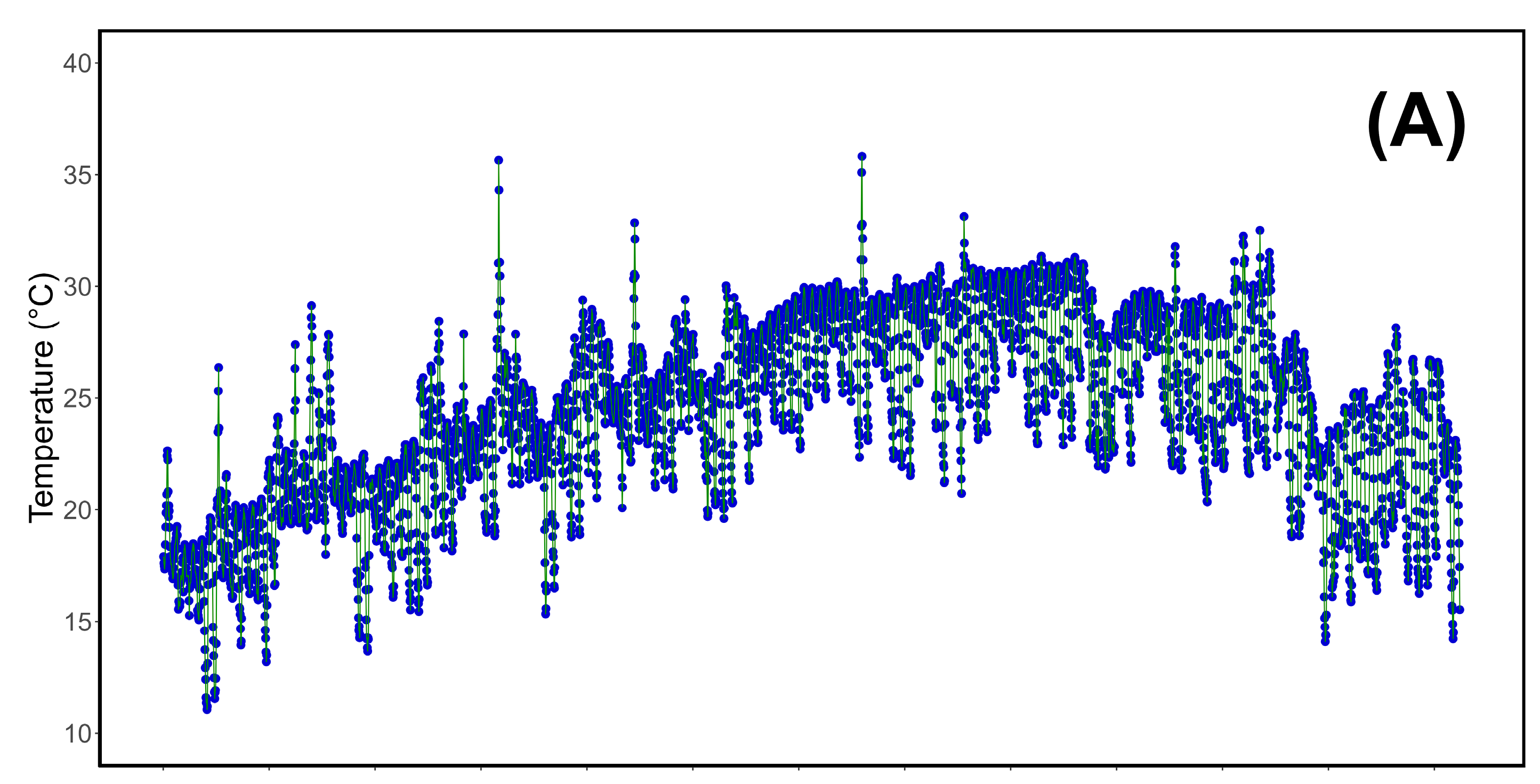

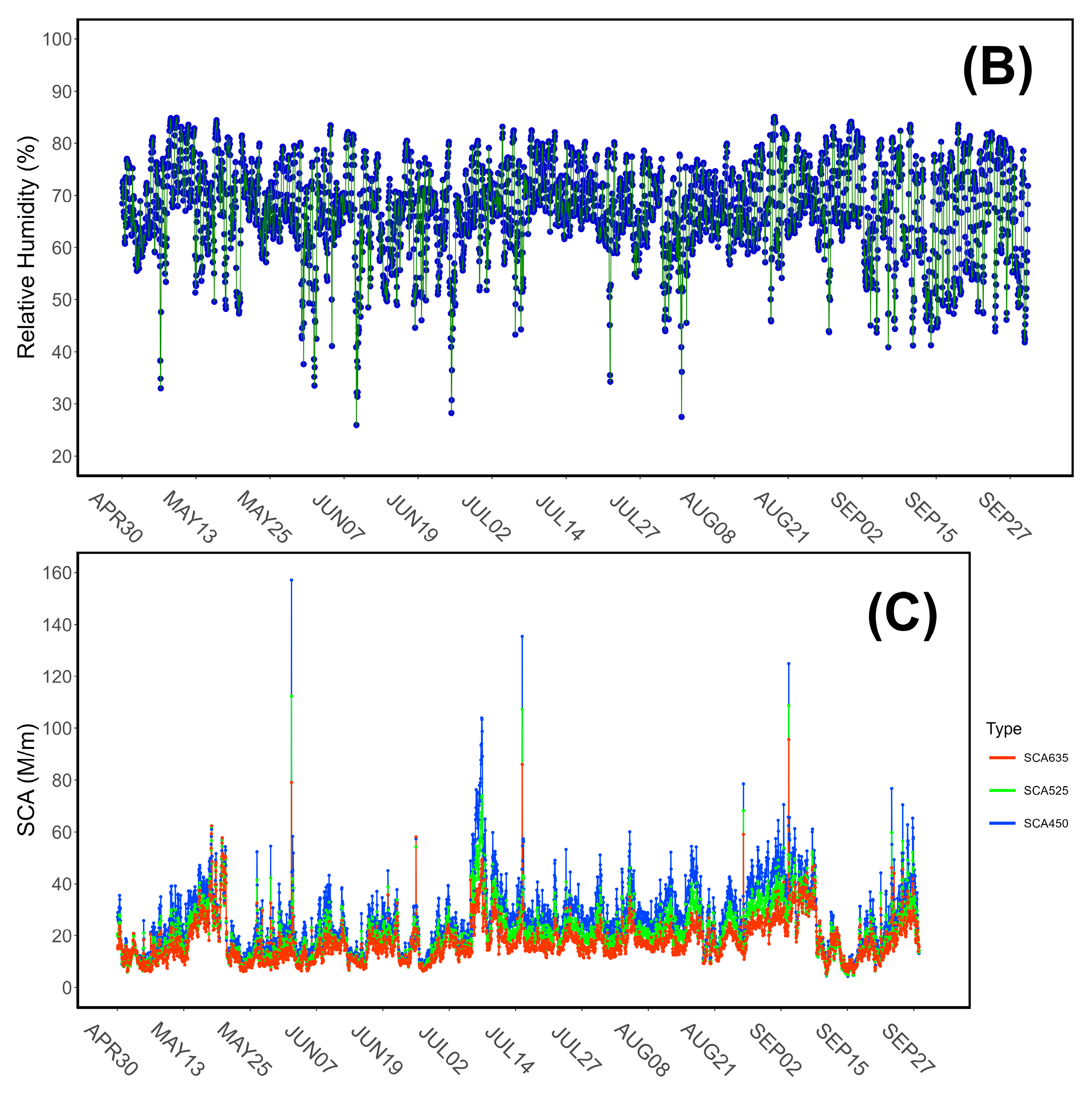

3.1. Daily Variability During the Observation Period

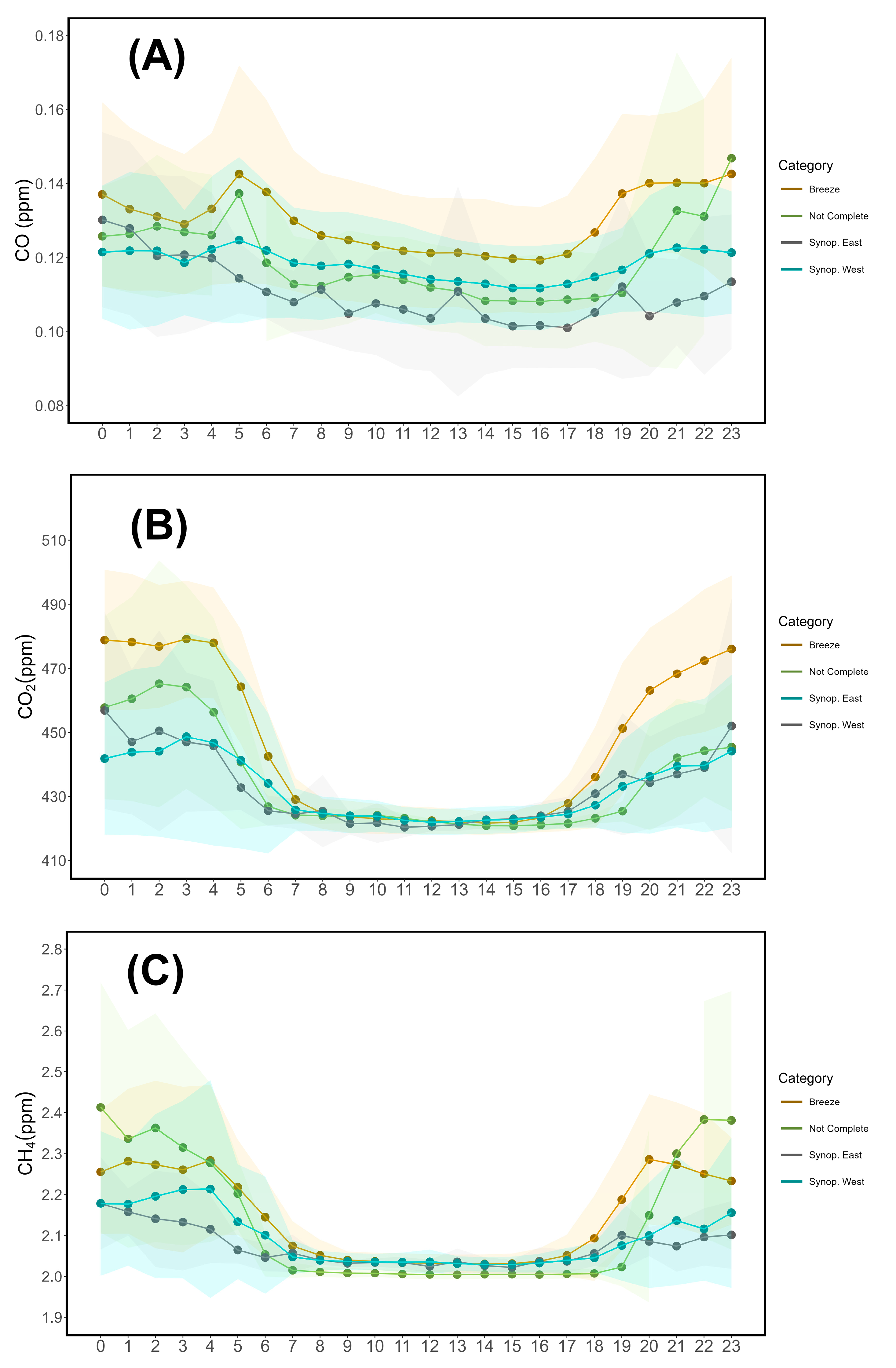

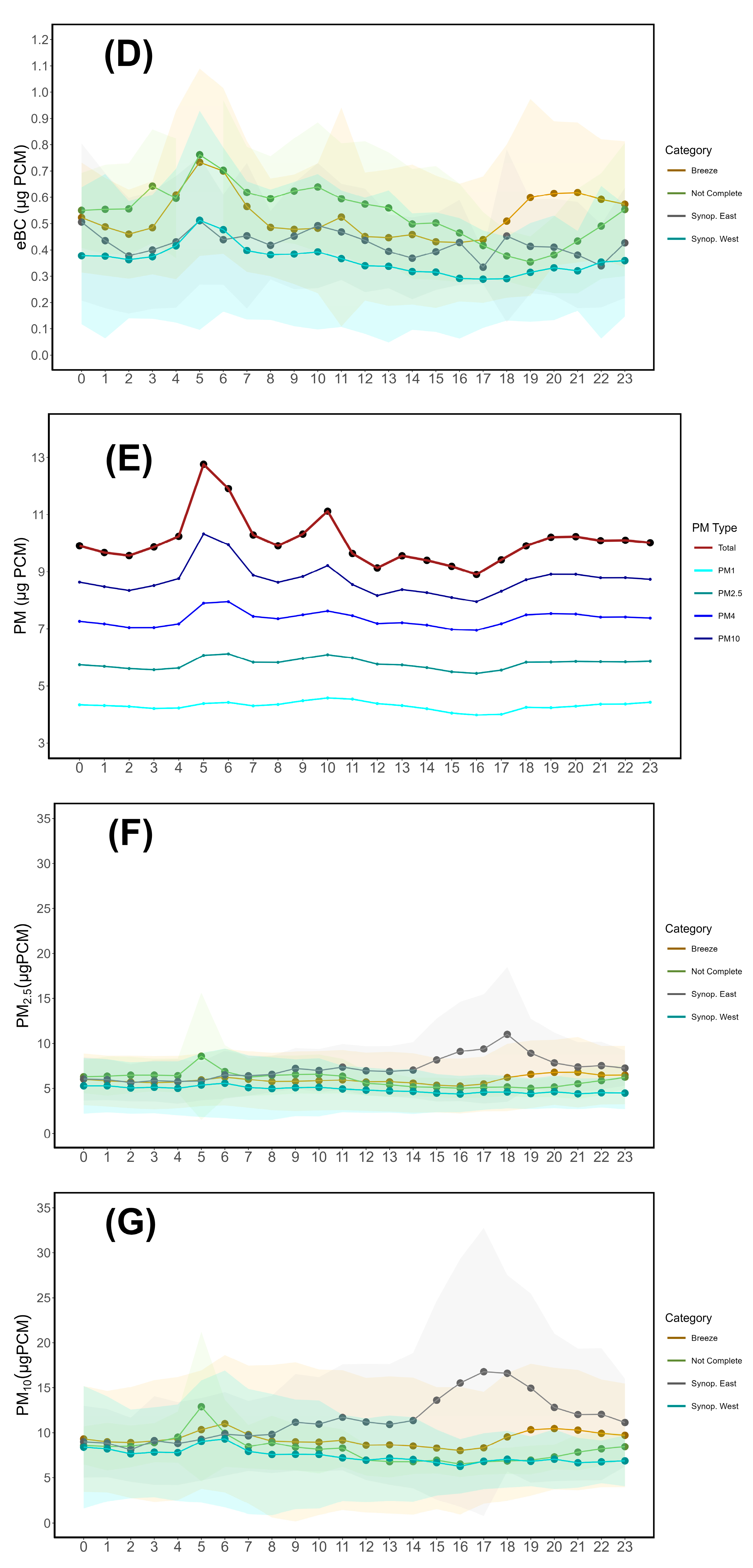

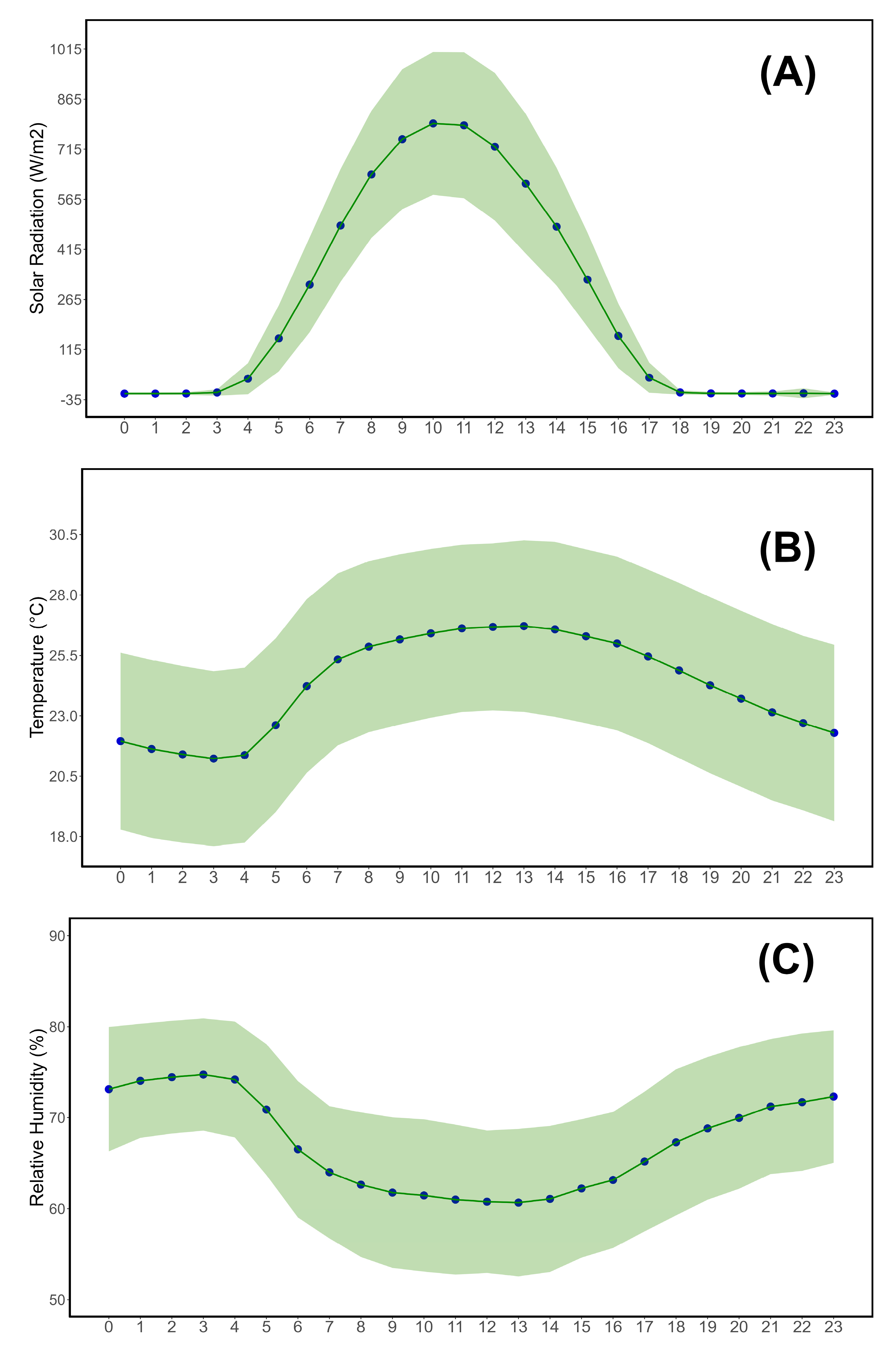

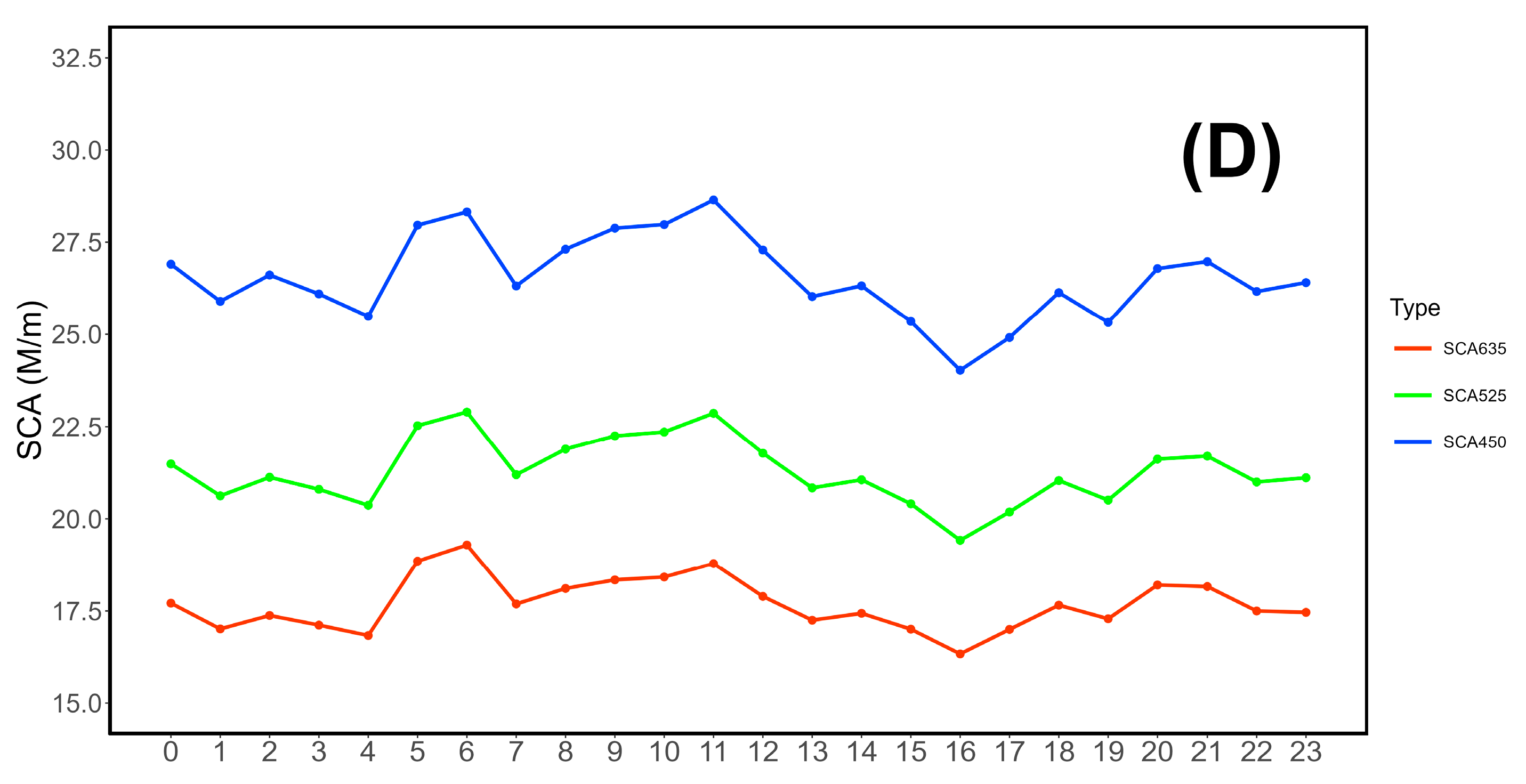

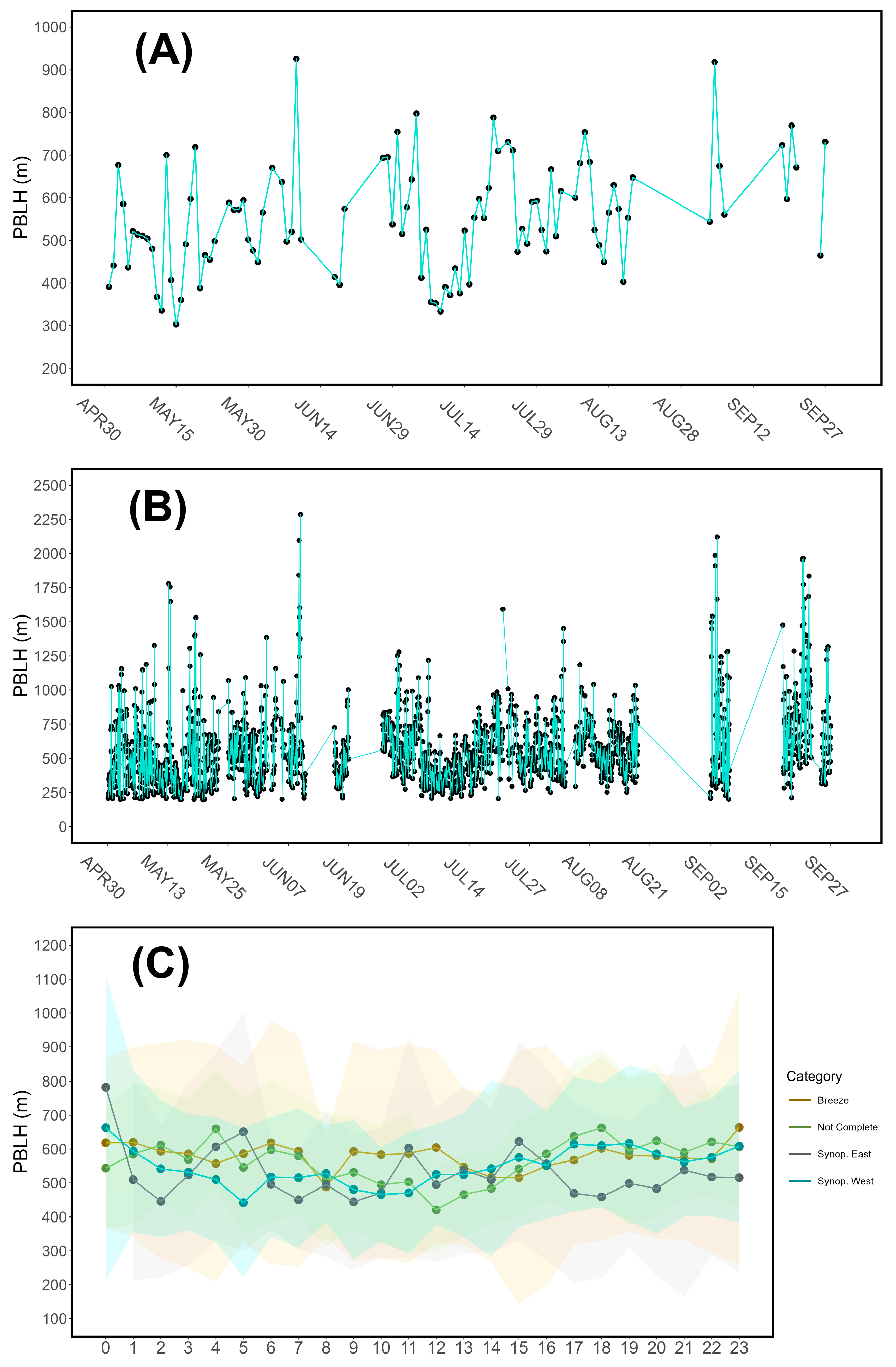

3.2. Daily Cycles

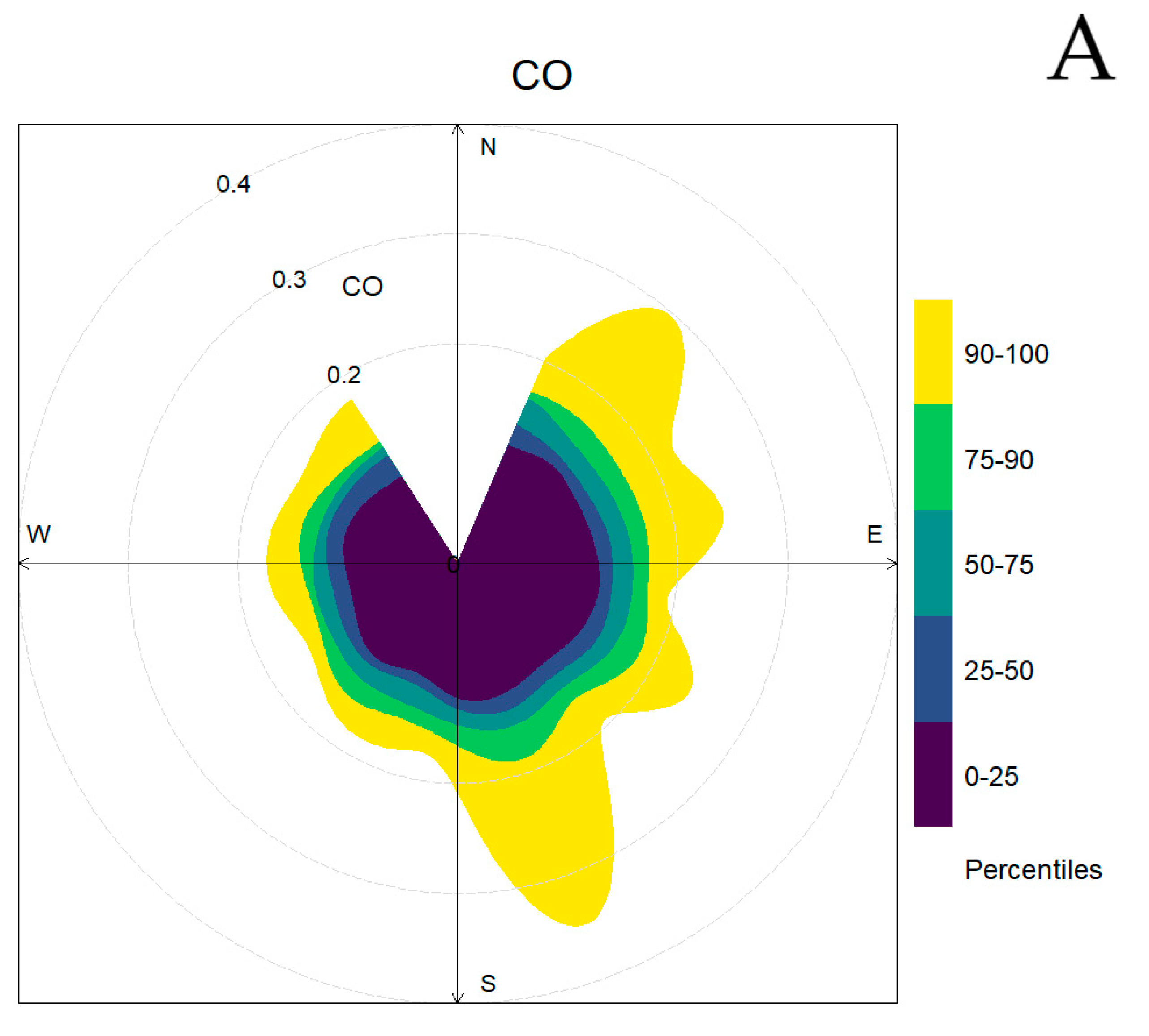

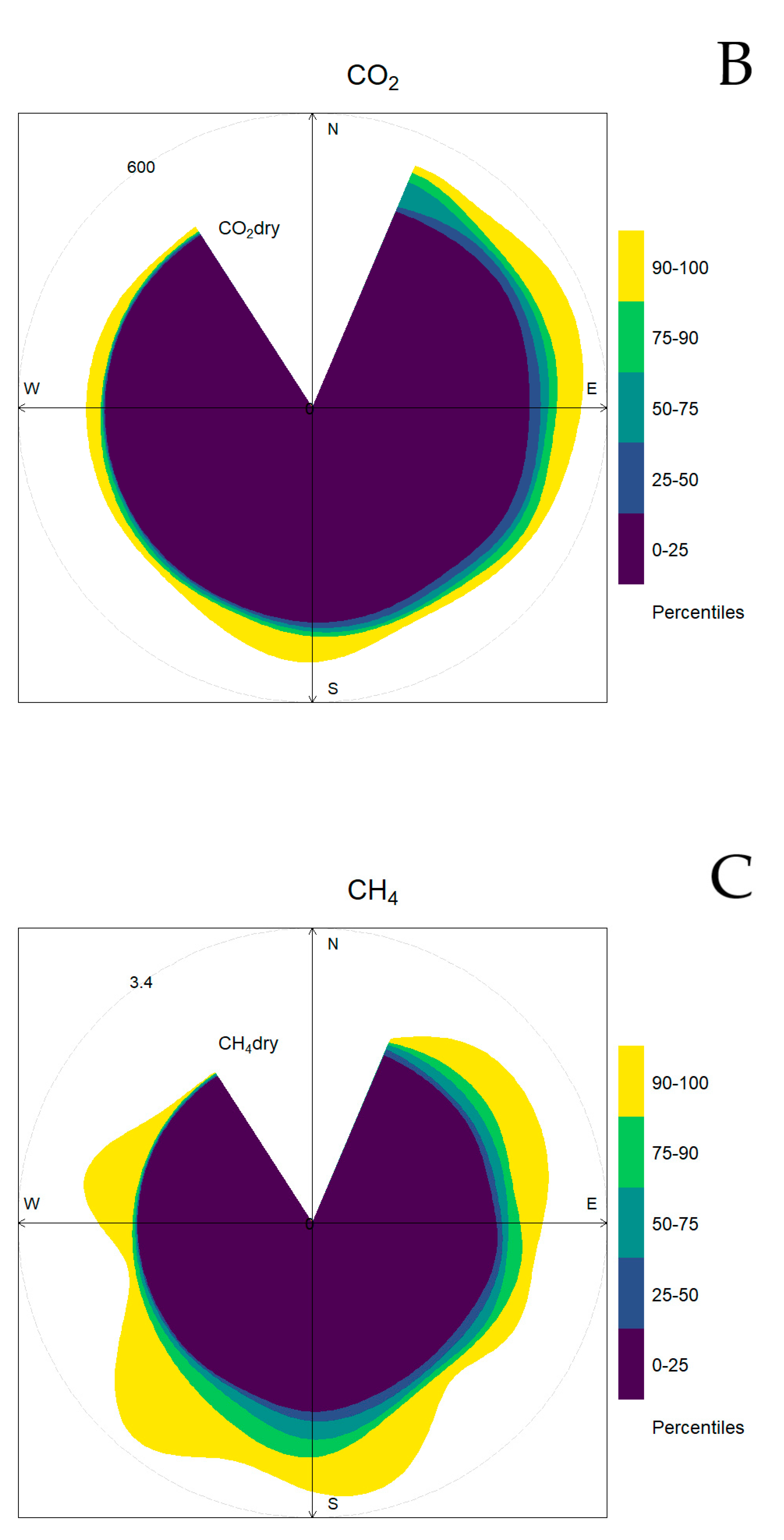

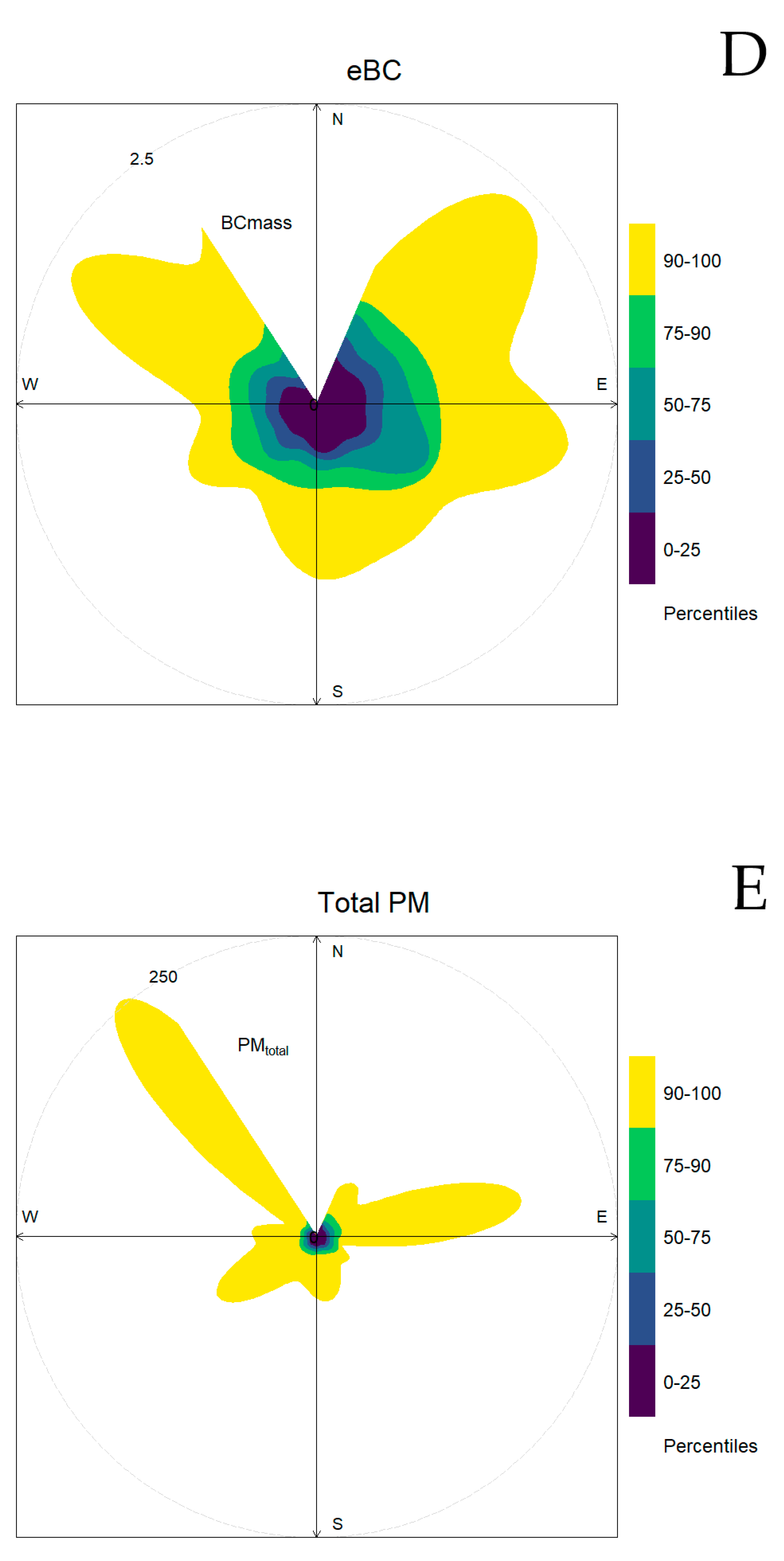

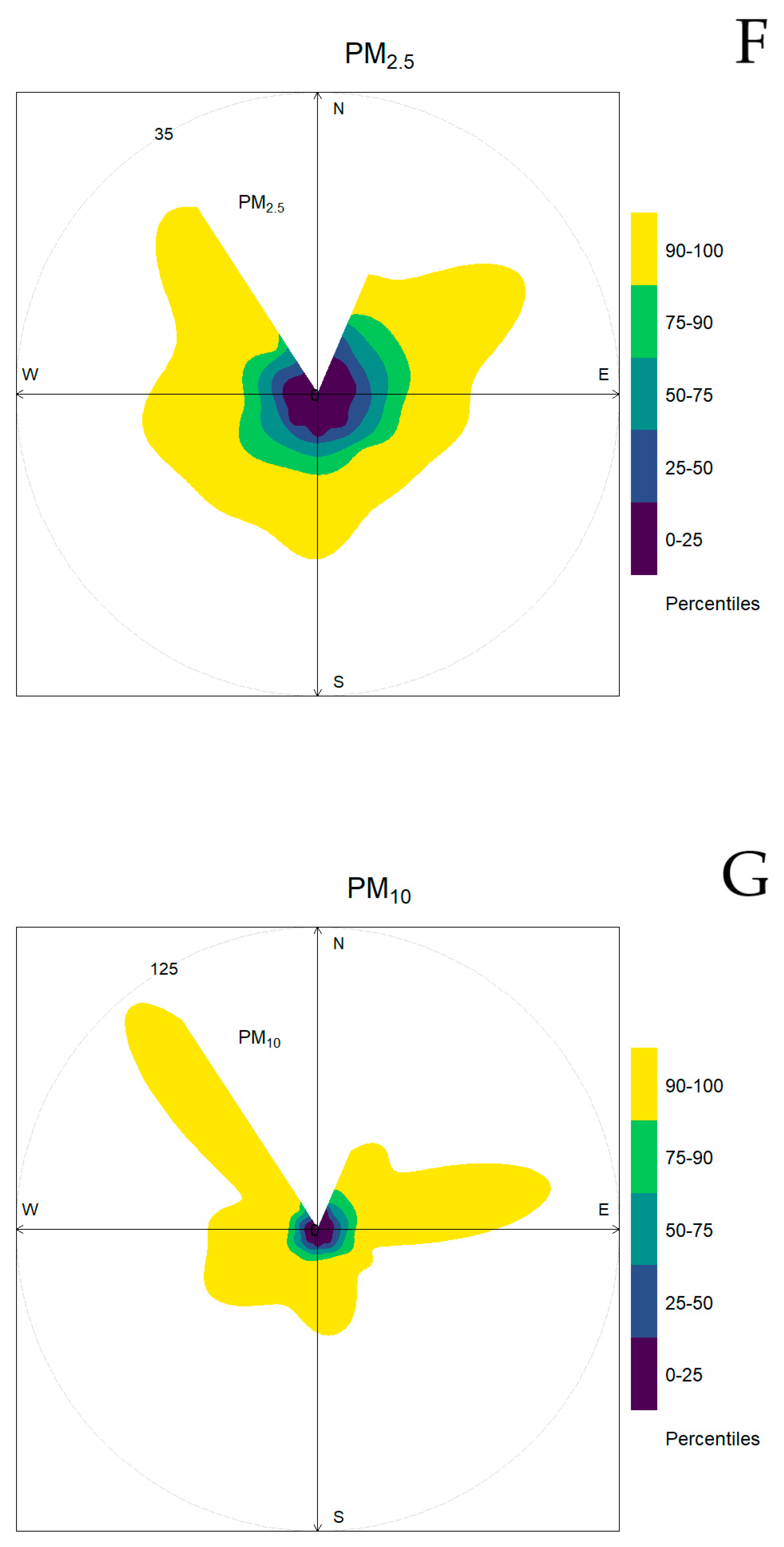

3.3. Percentile Roses

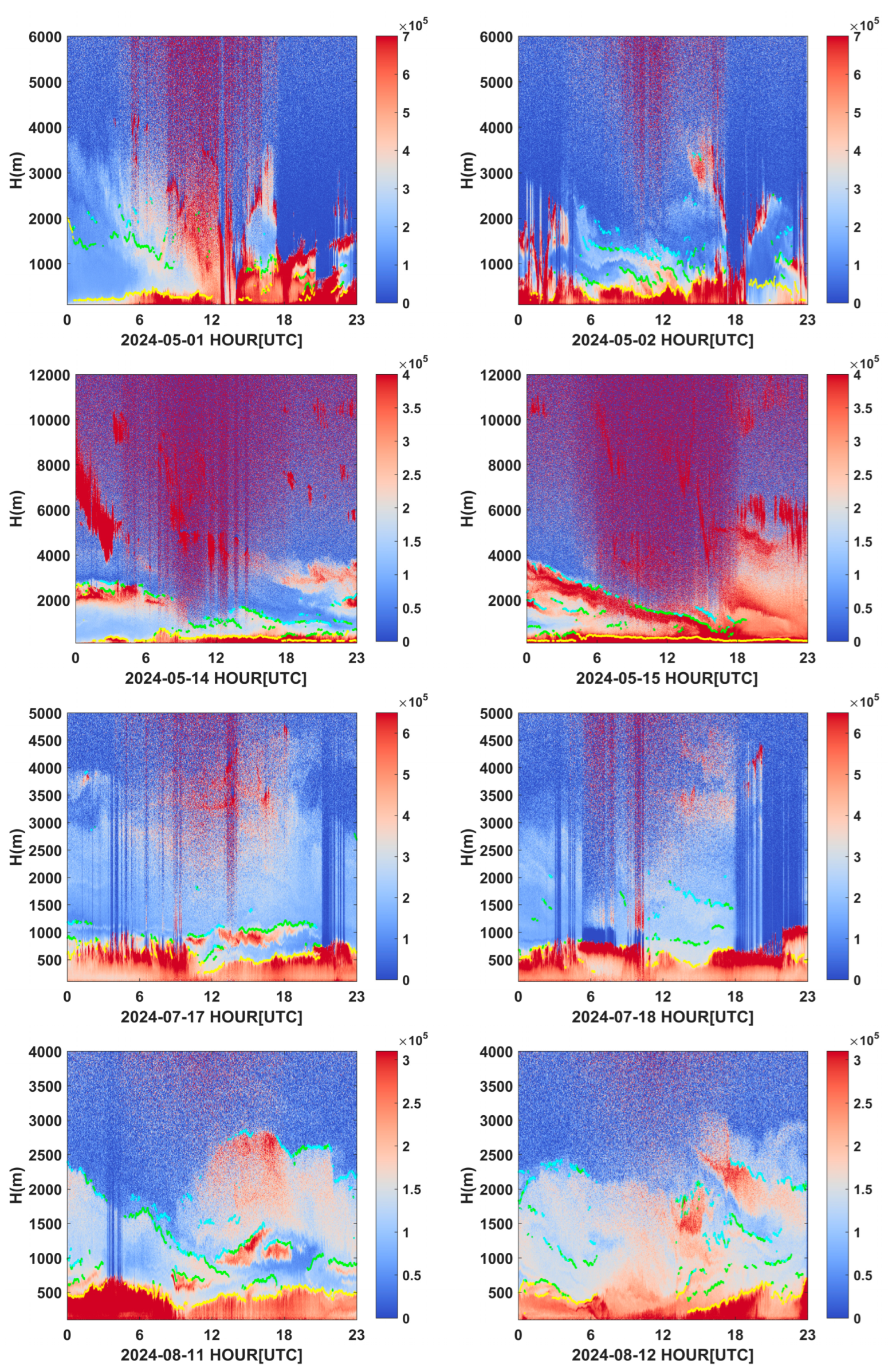

3.4. PBL Variability and Cycles

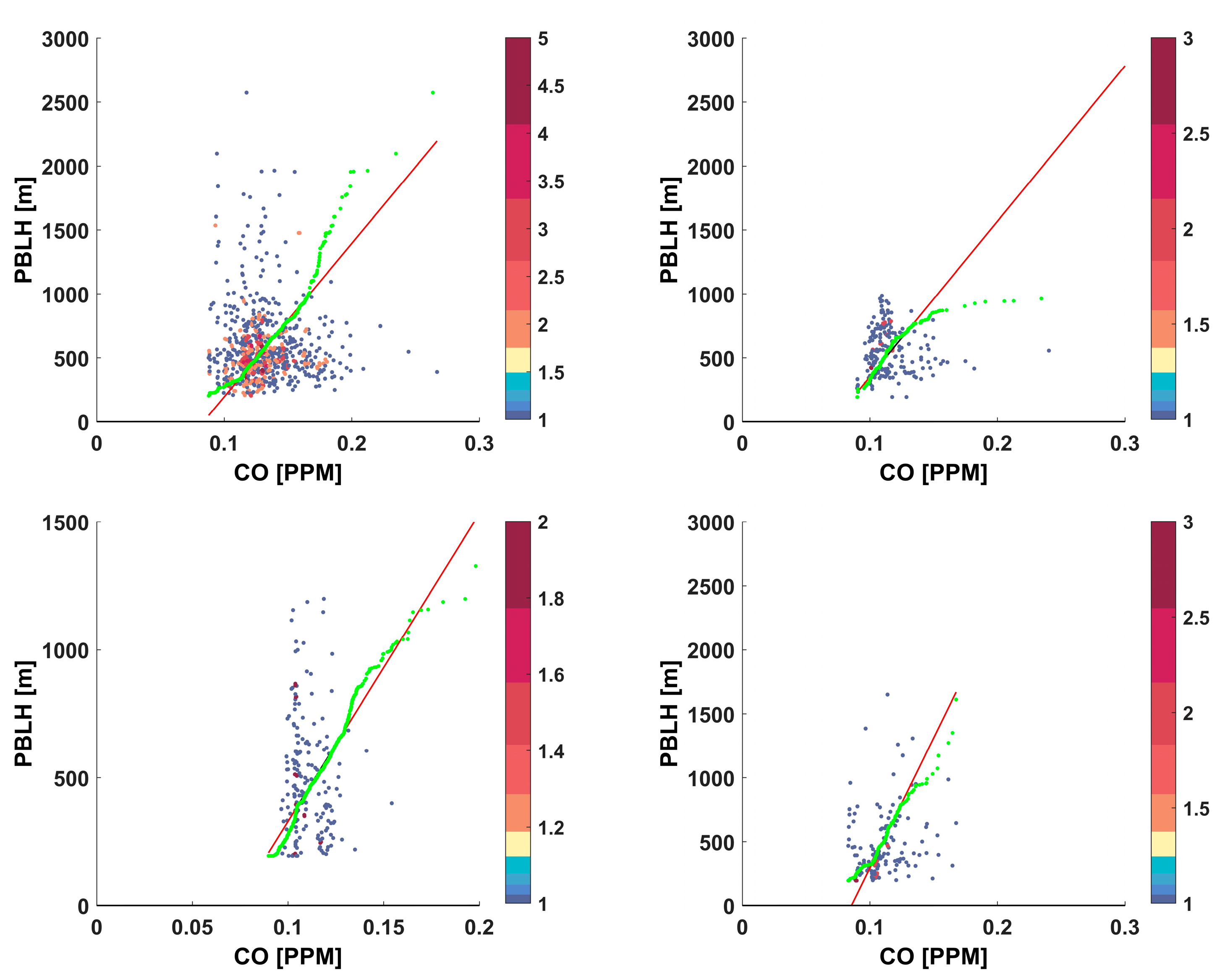

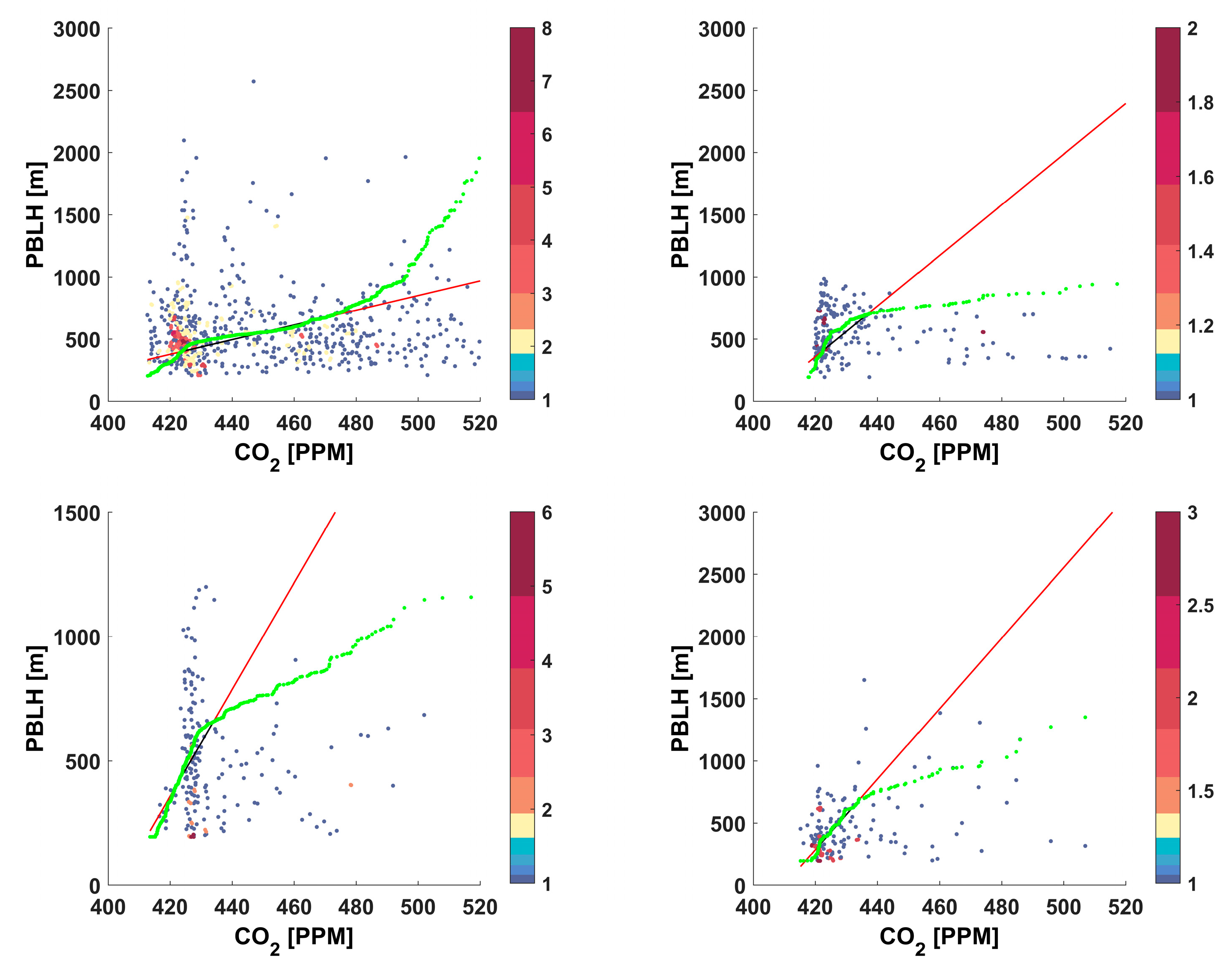

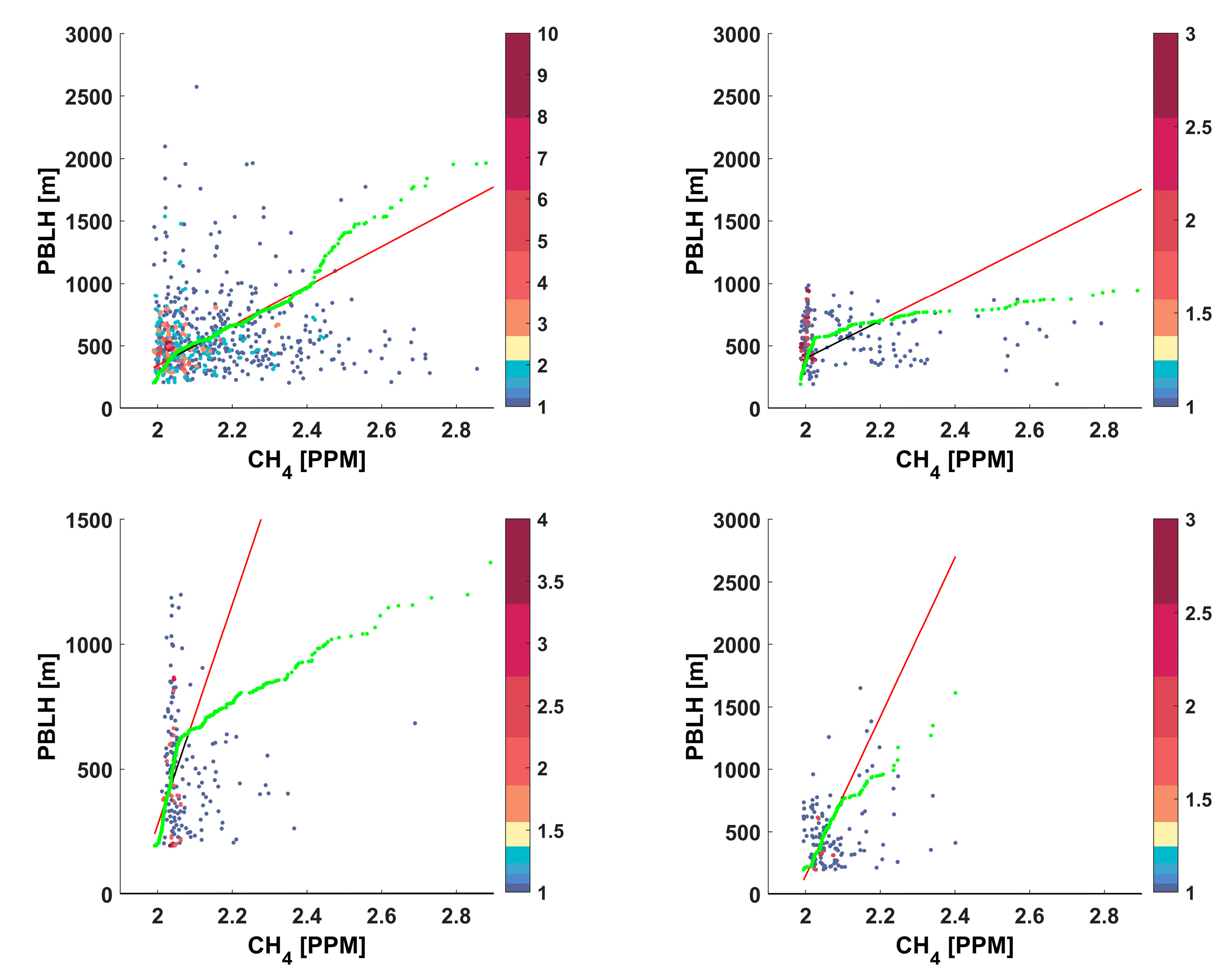

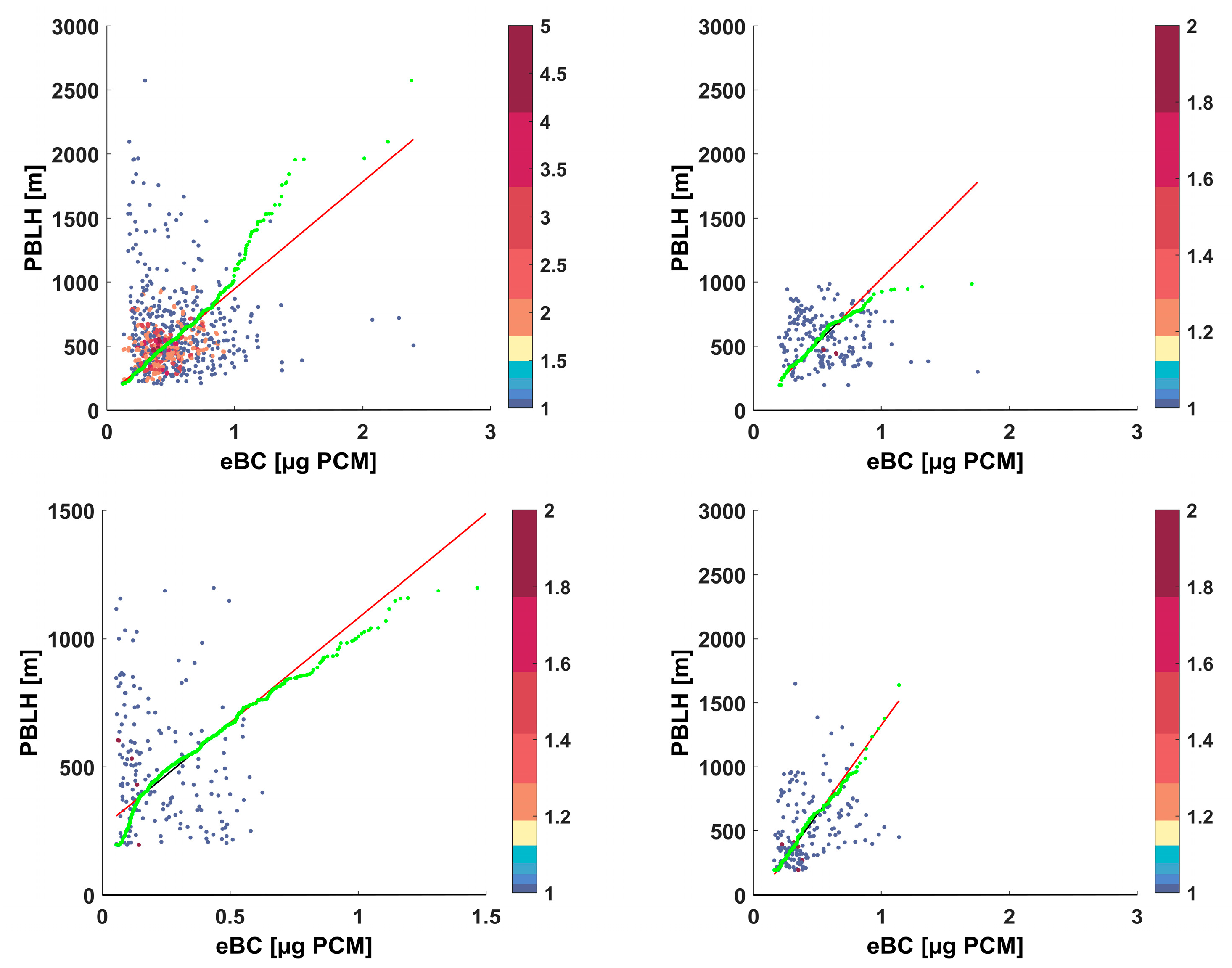

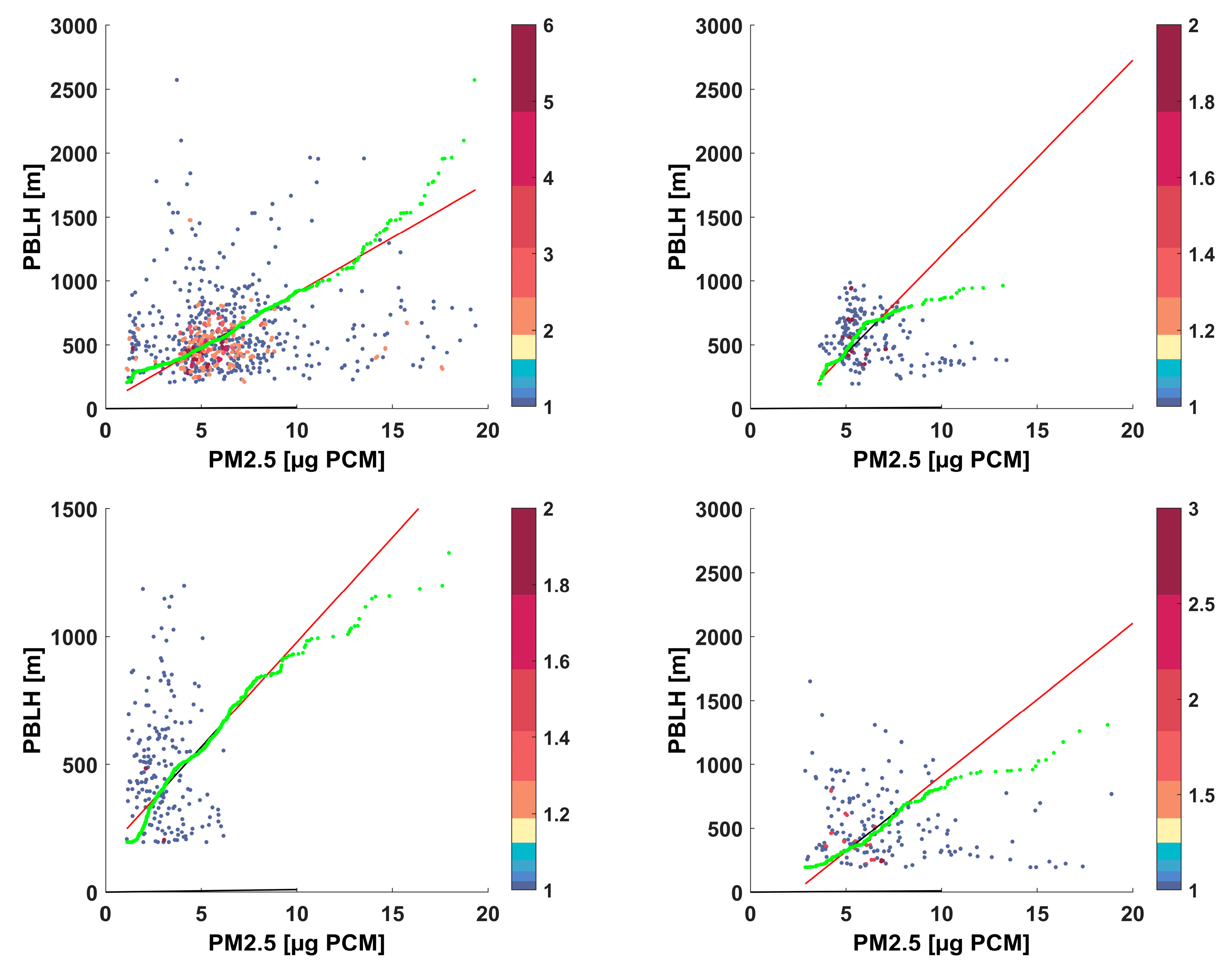

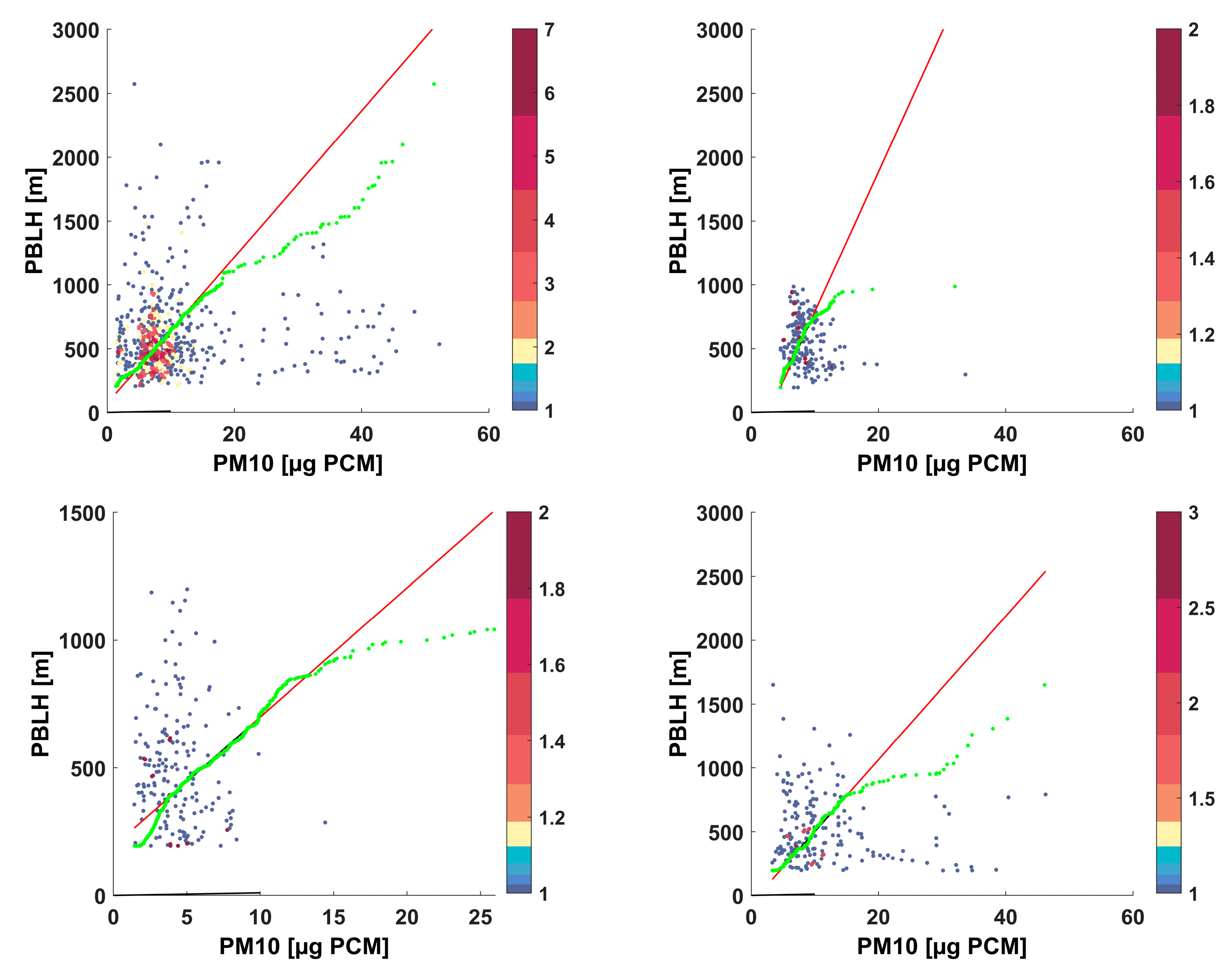

3.5. Correlations Between PBLH, Gases and Aerosols

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buajitti, K.; Blackadar, A.K. Theoretical studies of diurnal wind-structure variations in the planetary boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1957, 83(358), 486-500. [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.J.; Munn, R.E. Use of radioactive tracers in studying mass transfer in the atmospheric boundary layer. Phys. Fluids 1967, 10(9), S263–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, M.A.; Bhumralkar, C.M. A method for solving the planetary boundary-layer equations. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1970, 1, 169–194. [CrossRef]

- Godev, N. On the cyclogenetic nature of the Earth's orographic form. Arch. Met. Geoph. Biokl. A. 1970, 19, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.H. Observational studies in the atmospheric boundary layer. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1970, 96(407), 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, J.W. The surface roughness and planetary boundary layer. PAGEOPH 1980, 119(2), 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.W.; Wilson, J.R.; Burling, R.W. Some statistical properties of small scale turbulence in an atmospheric boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 1970, 41, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Atta, C.W.; Chen, W.Y. Structure functions of turbulence in the atmospheric boundary layer over the ocean. J. Fluid Mech. 1970, 44, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, J.R.; Francey, R.J. Bulk characteristics of heat transfer in the unstable, baroclinic atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1978, 15(4), 399-421. [CrossRef]

- Schönwald, B. Determination of vertical temperature profiles for the atmospheric boundary layer by ground-based microwave radiometry. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1978, 15(4), 453-464. [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.P.S. Comparative effects of stability, baroclinity and the scale-height ratio on drag laws for the atmospheric boundary layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 1978, 35, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. A numerical experiment of the PBL with geostrophic momentum approximation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 1988, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, J.K. Correlations in the vertical component of the wind at heights of 600, 1,600 and 2,600 ft at Cardington. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1964, 90(385), 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Kluwer Acad.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; p. 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensrud, D.J. Parameterization Schemes: Keys to Understanding Numerical Weather Prediction Models; Cambridge University Press, UK, 2007; p. 459. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, X.Z. Observed diurnal cycle climatology of planetary boundary layer height. J. Clim. 2010, 23(21), 5790–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gong, W.; Mao, F.; Pan, Z. An Improved Iterative Fitting Method to Estimate Nocturnal Residual Layer Height. Atmosphere 2016, 7(8), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, N.A.; Fotiadi, A.; Kariofillidi, S. Climatology of the Boundary Layer Height and of the Wind Field over Greece. Atmosphere 2020, 11(9), 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, N.; Wang, R. Diurnal variability of the planetary boundary layer height estimated from radiosonde data. Earth Planet. Phys. 2020, 4(5), 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.S.; Snodgrass, H.F. Some parameterizations of the nocturnal boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979, 17, 15-28. [CrossRef]

- Mahrt, L.; Heald, R.C.; Lenschow, D.H.; Stankov, B.B.; Troen, I.B. An observational study of the structure of the nocturnal boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979, 17(2), 247-264. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.A. Mesoscale nocturnal jetlike winds within the planetary boundary layer over a flat, open coast. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979, 17(4), 485-494. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, V.; Li, Z. Detection, variation and intercomparison of the planetary boundary layer depth from radiosonde, lidar and infrared spectrometer. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 79, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, M.C.; Praz, C.; Haefele, A.; Ruffieux, D.; Kaufmann, P.; Calpini, B. Determination and climatology of the planetary boundary layer height above the Swiss plateau by in situ and remote sensing measurements as well as by the COSMO-2 model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14(23), 13205–13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R. The thickness of the planetary boundary layer. Atmos. Environ. 1969, 3(5), 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeda, M.S. A bulk model for the atmospheric planetary boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979, 17(4), 411-427. [CrossRef]

- Odintsov, S.; Miller, E.; Kamardin, A.; Nevzorova, I.; Troitsky, A.; Schröder, M. Investigation of the Mixing Height in the Planetary Boundary Layer by Using Sodar and Microwave Radiometer Data. Environments 2021, 8(11), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Els, N.; Baumann-Stanzer, K.; Larose, C.; Vogel, T.M.; Sattler, B. Beyond the planetary boundary layer: Bacterial and fungal vertical biogeography at Mount Sonnblick, Austria. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2019, 6, e00069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tignat-Perrier, R.; Dommergue, A.; Vogel, T.M.; Larose, C. Microbial Ecology of the Planetary Boundary Layer. Atmosphere 2020, 11(12), 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthes, R.A. The height of the planetary boundary layer and the production of circulation in a sea breeze model. J. Atmos. Sci. 1978, 35(7), 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.K.; Yeh, E.N. A model of the effects of stack and inversion heights on the transport and diffusion of pollutants in the planetary boundary layer. Atmos. Environ. 1979, 13(6), 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, M. Ergebnisse von Modellrechnungen zur Ausbreitung von Stoffbeimengungen in der planetarischen Grenzschicht. Z. Meteorol. 1980, 30, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jordanov, D.L.; Dzolov, G.D.; Sirakov, D.E. Effect of planetary boundary layer on long-range transport and diffusion of pollutants. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie Bulgare des Sciences 1979, 32(12), 1635-1637.

- McNider, R.T.; Moran, M.D.; Pielke, R.A. Influence of diurnal and inertial boundary-layer oscillations on long-range dispersion. Atmos. Environ. 1988, 22(11), 2445–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; Freney, E.; Chauvigné, A.; Baray, J.-L.; Rose, C.; Picard, D.; Colomb, A.; Hadad, D.; Abboud, M.; Farah, W.; et al. Seasonal Variation of Aerosol Size Distribution Data at the Puy de Dôme Station with Emphasis on the Boundary Layer/Free Troposphere Segregation. Atmosphere 2018, 9(7), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptis, I.-P.; Kazadzis, S.; Amiridis, V.; Gkikas, A.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Mihalopoulos, N. A Decade of Aerosol Optical Properties Measurements over Athens, Greece. Atmosphere 2020, 11(2), 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.P.; Lauvaux, T.; Feng, S.; Liu, J.; Bowman, K.W.; Davis, K.J. Atmospheric Simulations of Total Column CO2 Mole Fractions from Global to Mesoscale within the Carbon Monitoring System Flux Inversion Framework. Atmosphere 2020, 11(8), 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Ngan, F. Coupling of Important Physical Processes in the Planetary Boundary Layer between Meteorological and Chemistry Models for Regional to Continental Scale Air Quality Forecasting: An Overview. Atmosphere 2011, 2(3), 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tie, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, H.; Bi, K.; Jin, Y.; Chen, P. In-Situ Aircraft Measurements of the Vertical Distribution of Black Carbon in the Lower Troposphere of Beijing, China, in the Spring and Summer Time. Atmosphere 2015, 6(5), 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S. Relationships between Springtime PM2.5, PM10, and O3 Pollution and the Boundary Layer Structure in Beijing, China. Sustainability 2022, 14(15), 9041. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Ming, J.; Wang, F. One-Year Measurements of Equivalent Black Carbon, Optical Properties, and Sources in the Urumqi River Valley, Tien Shan, China. Atmosphere 2020, 11(5), 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlich, R.M.; Ludwig, F.L.; Uthe, E.E. An automatic method for determining the mixing depth from lidar observations. Atmos. Environ. 1979, 13(7), 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Pérez, C.; Comerón, A.; Baldasano, J.M.; Rocadenbosch, F. Determination of the mixing layer height from regular lidar measurements in the Barcelona Area. Proceedings of SPIE – The International Society for Optical Engineering 2004, 5235, 505-516. [CrossRef]

- Münkel, C.; Räsänen, J. New optical concept for commercial lidar ceilometers scanning the boundary layer. Proceedings of SPIE – The International Society for Optical Engineering 2004, 5571. [CrossRef]

- Emeis, S.; Schäfer, K. Remote Sensing Methods to Investigate Boundary-layer Structures relevant to Air Pollution in Cities. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 2006, 121, 377–385. [CrossRef]

- Emeis, S.; Schäfer, K.; Münkel, C. Surface-based remote sensing of the mixing-layer height: a review. Meteorol. Z. 2008, 17(5), 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melfi, S.H.; Spinhirne, J.D.; Chou, S.-H.; Palm, S.P. Lidar observations of vertically organized convection in the planetary boundary layer over the ocean. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 1985, 24(8), 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, W.J. Importance of the atmospheric boundary layer over the oceans in synoptic scale meteorology. Phys. Fluids 1967, 10(9), S203–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynor, G.S.; Sethuraman, S.; Brown, R.M. Formation and characteristics of coastal internal boundary layers during onshore flows. Boundary-Layer Meteorol. 1979, 16(4), 487-514. [CrossRef]

- Burk, S.D.; Haack, T.; Samelson, R.M. Mesoscale simulation of supercritical, subcritical, and transcritical flow along coastal topography. J. Atmos. Sci. 1999, 56(16), 2780–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.A.; Rogerson, A.M.; Winant, C.D.; Rogers, D.P. Adjustment of the marine atmospheric boundary layer to a coastal cape. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58(12), 1511–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmis, C.G. An experimental case study of the mean and turbulent characteristics of the vertical structure of the atmospheric boundary layer over the sea. Meteorol. Z. 2007, 16, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantonio, G.; Petenko, I.; Viola, A.; Argentini, S.; Coniglio, L.; Monti, P.; Leuzzi, G. Influence of the synoptic circulation on the local wind field in a coastal area of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Earth Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.; Gryning, S.-E.; Hahmann, A.N. Observations of the atmospheric boundary layer height under marine upstream flow conditions at a coastal site. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 1924–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, V.; Rappenglueck, B.; Cuchiara, G.; Flynn, J.; Ferrare, R.; Scarino, A.J.; Berkoff, T.; Senff, C.; Langford, A.; Lefer, B. Bay breeze and sea breeze circulation impacts on the planetary boundary layer and air quality from an observed and modeled DISCOVER-AQ Texas case study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124(13), 7359–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barantiev, D.; Batchvarova, E.; Novitsky, M. Breeze circulation classification in the coastal zone of the town of Ahtopol based on data from ground based acoustic sounding and ultrasonic anemometer. Bulg. J. Meteorol. Hydrol. 2017, 22, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lyulyukin, V.; Kallistratova, M.; Zaitseva, D.; Kuznetsov, D.; Artamonov, A.; Repina, I.; Petenko, I.V.; Kouznetsov, R.; Pashkin, A. Sodar Observation of the ABL Structure and Waves over the Black Sea Offshore Site. Atmosphere 2019, 10(12), 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.-M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. A Review of Techniques for Diagnosing the Atmospheric Boundary Layer Height (ABLH) Using Aerosol Lidar Data. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11(13), 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Quantifying and comparing fuel-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions: Coal, oil and natural gas consumption. Energy Policy 1990, 18, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheraga, J.D.; Leary, N.A. Improving the efficiency of policies to reduce CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 1992, 20, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.M. CO2 and climatic change: An overview of the science. Energy Convers. Manag. 1993, 34, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zeng, N. Continued increase in atmospheric CO2 seasonal amplitude in the 21st century projected by the CMIP5 Earth system models. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2014, 5, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.D.; Whorf, T.P.; Wahlen, M.; van der Plichtt, J. Interannual extremes in the rate of rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide since 1980. Nature 1995, 375, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabbutt, J.A. Impacts of carbon dioxide warming on climate and man in the semi-arid tropics. Climatic Change 1989, 15(1-2), 191-221. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.C. Greenhouse effect and climate change: scientific basis and overview. Renew. Energy 1993, 3(4-5), 403-420. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Satish, U.; Santanam, S.; Vallarino, J.; Spengler, J.D. Associations of cognitive function scores with carbon dioxide, ventilation, and volatile organic compound exposures in office workers: A controlled exposure study of green and conventional office environments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124(6), 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Golden, C.D.; Myers, S.S. Potential rise in iron deficiency due to future anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. GeoHealth 2017, 1(6), 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, F.; Ashrafi, A.; Kinney, P.; Mills, D. Towards a fuller assessment of benefits to children’s health of reducing air pollution and mitigating climate change due to fossil fuel combustion. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, B.; Eriksson, E. Changes in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere and sea due to fossil fuel combustion. Rossby Meml. Vol. 1959, 130–142. In The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion: Scientific Contributions to the Rossby Memorial Volume. Bert Bolin, ed. New York.

- Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Hauglustaine, D.A.; Chu, D.A.; Gille, J.C.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Pétron, G.; Yurganov, L.N.; Giglio, L.; Deeter, M.N.; et al. Observations of carbon monoxide and aerosols from the Terra satellite: Northern Hemisphere variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2004, 109, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chevallier, F.; Ciais, P.; Yin, Y.; Deeter, M.N.; Worden, H.M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, K. Rapid decline in carbon monoxide emissions and export from East Asia between years 2005 and 2016. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.K.; Rasmussen, R.A. Carbon Monoxide in the Earth's Atmosphere: Increasing Trend. Science 1984, 223(4644), 54-56. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.224.4644.54.

- Buchholz, R.R.; Worden, H.M.; Park, M.; Francis, G.; Deeter, M.N.; Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Gaubert, B.; Gille, J.; Martínez-Alonso, S.; et al. Air pollution trends measured from Terra: CO and AOD over industrial, fire-prone, and background regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J. Lifetimes and time scales in atmospheric chemistry. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2007, 365, 1705–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenco, A. Variations of CO and O3 in the troposphere: Evidence of O3 photochemistry. Atmos. Environ. 1986, 20, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopa, S.; Naik, V.; Adhikary, B.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Collins, W.D.; Fuzzi, S.; Gallardo, L.; Kiendler-Scharr, A.; Klimont, Z.; et al. Short-Lived Climate Forcers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 817–922. [Google Scholar]

- Skeie, R.B.; Hodnebrog, Ø.; Myhre, G. Trends in atmospheric methane concentrations since 1990 were driven and modified by anthropogenic emissions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Stavert, A.R.; Poulter, B.; Bousquet, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Raymond, P.A.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Patra, P.K.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Fahey, D.; Forster, P.M.; Newton, P.J.; Wit, R.C.N.; Lim, L.L.; Owen, B.; Sausen, R. Aviation and global climate change in the 21st century. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 3520–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Fahey, D.W.; Skowron, A.; Allen, M.R.; Burkhardt, U.; Chen, Q.; Doherty, S.J.; Freeman, S.; Forster, P.M.; Fuglestvedt, J.; et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.E.; Lowry, D.; France, J.L.; Allen, G.; Bakkaloglu, S.; Broderick, T.J.; Cain, M.; Coleman, M.; Fernandez, J.; Forster, G.; Griffiths, P.T.; Iverach, C.P.; Kelly, B.F.J.; Manning, M.R.; Nisbet-Jones, P.B.R.; Pyle, J.A.; Townsend-Small, A.; al-Shalaan, A.; Warwick, N.; Zazzeri, G. Methane Mitigation: Methods to Reduce Emissions, on the Path to the Paris Agreement. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58(1), e2019RG000675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, H. Atmospheric light absorption: A review. Atmos. Environ. Part A 1993, 27, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chameides, W.L.; Bergin, M. Soot takes center stage. Science 2002, 297, 2214–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, T.C.; Doherty, S.J.; Fahey, D.W.; Forster, P.M.; Berntsen, T.; DeAngelo, B.J.; Flanner, M.G.; Ghan, S.; Kärcher, B.; Koch, D.; et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 5380–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighty, J.S.; Veranth, J.M.; Sarofim, A.F. Combustion aerosols: Factors governing their size and composition and implications to human health. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2000, 50, 1565–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z. Strong radiative heating due to the mixing state of black carbon in atmospheric aerosols. Nature 2001, 409, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Carmichael, G. Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artíñano, B.; Salvador, P.; Alonso, D.G.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A. Influence of traffic on the PM10 and PM2.5 urban aerosol fractions in Madrid (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 334-335, 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.G.; Robertson, L.A.; Hamilton, R.S.; Gorbunov, B. A Lagrangian model of the evolution of the particulate size distribution of vehicular emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 334-335, 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Claiborn, C.S.; Finn, D.; Larson, T.V.; Koenig, J.Q. Windblown dust contributes to high PM2.5 concentrations. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2000, 50(8), 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Rodriguez, S.; Plana, F.; Ruiz, C.; Cots, N.; Massagué, G.; Puig, O. PM10 and PM2.5 source apportionment in the Barcelona Metropolitan area, Catalonia, Spain. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35(36), 6407-6419. [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Gangoiti, G.; Menéndez, M. PM levels in the Basque County (Northern Spain): Analysis of a 5-year data record and interpretation of seasonal variations. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37(21), 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttinen, P.; Timonen, K.L.; Tiittanen, P.; Mirme, A.; Ruuskanen, J.; Pekkanen, J. Ultrafine particles in urban air and respiratory health among adult asthmatics. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 17(3), 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, T.F.; Larson, T.V.; Stier, R.A.; Claiborn, C.; Koenig, J.Q. An analysis of the association between respiratory symptoms in subjects with asthma and daily air pollution in Spokane, Washington. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004, 16(13), 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, T.; De Donno, A.; Serio, F.; Genga, A. Source Apportionment of PM10 as a Tool for Environmental Sustainability in Three School Districts of Lecce (Apulia). Sustainability 2024, 16(5), 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, F. Urban boundary layer height characteristics and relationship with particulate matter mass concentrations in Xi'an, central China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2013, 13(5), 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Che, H.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Hong, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gui, K.; Sun, T. Aerosol vertical distribution and typical air pollution episodes over northeastern China during 2016 analyzed by ground-based lidar. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2018, 18(4), 918–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Hong, Y. Vertical distribution of particulate matter and its relationship with planetary boundary layer structure in Shenyang, northeast China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019, 19(11), 2464–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Di, H.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Hua, D.; Wang, L.; Chen, D. Detection of aerosol mass concentration profiles using single-wavelength Raman Lidar within the planetary boundary layer. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2021, 272, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazeau, B.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Grégory, G.; Mesbah, B.; D’Anna, B.; Wortham, H.; Marchand, N. Measurement report: Fourteen months of real-time characterization of the submicronic aerosol and its atmospheric dynamics at the Marseille-Longchamp supersite. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21(9), 7293–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Sempreviva, A.M. Study of the Vertical Structure of the Coastal Boundary Layer Integrating Surface Measurements and Ground-Based Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20(22), 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Burlizzi, P.; Perrone, M.R. Solar eclipse of 20 March 2015 and impacts on irradiance, meteorological parameters, and aerosol properties over southern Italy. Atmos. Res. 2017, 198, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Bellecci, C.; Colacino, M. Quantitative precipitation forecast of the Soverato flood: The role of orography and surface fluxes. Nuovo Cimento Soc. Ital. Fis. C. 2003, 26(1), 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Bellecci, C.; Colacino, M. Numerical simulation of Crotone flood: Storm evolution. Nuovo Cimento Soc. Ital. Fis. C. 2003, 26(4), 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Avolio, E.; Bellecci, C.; Lavagnini, A.; Colacino, M.; Walko, R.L. Numerical analysis of an intense rainstorm occurred in southern Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 8, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; De Leo, L.; Bellecci, C. A study of the breeze circulation during summer and fall 2008 in Calabria, Italy. Atmos. Res. 2010, 97(1-2), pgs. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; Sempreviva, A.M.; De Leo, L.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Bellecci, C. The seasonal characteristics of the breeze circulation at a coastal Mediterranean site in South Italy. Adv. Sci. Res. 2010, 4, pgs. 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Lo Feudo, T.; Torcasio, R.C.; Sempreviva, A.M. Two years of wind-lidar measurements at an Italian Mediterranean Coastal Site. In European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2017, EGU – Division Energy, Resources & Environment, ERE. Energy Procedia 2017, 125, pgs. 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Federico, S.; Miglietta, M.M.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A.M. Sensitivity analysis of WRF model PBL schemes in simulating boundary-layer variables in southern Italy: An experimental campaign. Atmos. Res. 2017, 192, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Calzolari, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Dinoi, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Sferlazzo, D.; Di Iorio, T.; Piacentino, S.; Marinoni, A.; Maione, M.; Bonasoni, P. Investigation of reactive gases and methane variability in the coastal boundary layer of the central Mediterranean basin. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T.; Marinoni, A.; Dinoi, A.; Avolio, E.; Merico, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Bonasoni, P. Characterization of In Situ Aerosol Optical Properties at Three Observatories in the Central Mediterranean. Atmosphere 2018, 9(10), 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Integrated analysis of methane cycles and trends at the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 15(8), 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Gullì, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Ammoscato, I.; Avolio, E.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Cyclic and multi-year characterization of surface ozone at the WMO/GAW coastal station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): implications for the local environment, cultural heritage, and human health. Accepted on MDPI Environments. Preprint:. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. Digital Elevation Model (DEM) for Europe at 30 arc seconds (ca. 1000 meter) resolution derived from Copernicus Global 30 meter DEM dataset, 2022. https://data.opendatascience.eu/geonetwork/srv/api/records/948c3313-9957-4581-a238-812439d44397. (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium. EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM 2016). EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium, 2016, 2016). EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Trends in CO, CO2, CH4, BC, and NOx during the first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown: source insights from the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Sustainability 2024, 16(18), 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Republic. Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 9 March 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 62. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T.; Marinoni, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Bonasoni, P. Long-term observations of aerosol optical properties at three GAW regional sites in the Central Mediterranean. Atmos. Res. 2020, 241, 104976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Anthropic-induced variability of greenhouse gases and aerosols at the WMO/GAW coastal site of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): towards a new method to assess the weekly distribution of gathered data. Sustainability 2024, 16(18), 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T. Five Years of Dust Episodes at the Southern Italy GAW Regional Coastal Mediterranean Observatory: Multisensors and Modeling Analysis. Atmosphere 2020, 11(5), 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Avolio, E.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Sinopoli, S.; Cristofanelli, P.; De Pino, M.; D’Amico, F.; Calidonna, C.R. Multiparameter detection of summer open fire emissions: the case study of GAW regional observatory of Lamezia Terme (Southern Italy). Fire 2024, 7(6), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Sugimoto, N.; Shimizu, A.; Nishizawa, T.; Kai, K.; Kawai, K.; Yamazaki, A.; Sakurai, M.; Wille, H. Evaluation of ceilometer attenuated backscattering coefficients for aerosol profile measurement. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2018, 12(4), 042604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Tiwari, S.; Mishra, A.; Singh, S.; Hopke, P.K.; Singh, S.; Attri, S.D. Characteristics of absorbing aerosols during winter foggy period over the National Capital Region of Delhi: Impact of planetary boundary layer dynamics and solar radiation flux. Atmos. Res. 2017, 188, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, P.; Beyrich, F.; Gryning, S.-E.; Joffre, S.; Rasmussen, A.; Tercier, P. : Review and intercomparison of operational methods for the determination of the mixing height. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1001–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lufft G. Manual Ceilometer CHM 15k “NIMBUS”. Campbell Scientific, Canada, 2016 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Philipona, R.; Kräuchi, A.; Brocard, E. Solar and thermal radiation profiles and radiative forcing measured through the atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L13806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, T.; Avolio, E.; Gullì, D.; Federico, S.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A. Comparison of Hourly Solar Radiation from a Ground-Based Station, Remote Sensing and Weather Forecast Models at a Coastal Site of South Italy (Lamezia Terme). Energy Procedia 2015, 76, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.M.; Hodges, J.T.; Rhoderick, G.C.; Lisak, D.; Travis, J.C. Methane-in-air standards measured using a 1.65 μm frequency-stabilized cavity ring-down spectrometer. Proc. SPIE 6378, Chemical and Biological Sensors for Industrial and Environmental Monitoring II 2006, 63780G. [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Kramer, H.; Schönlinner, M. Continuous Measurement of Atmospheric Black Carbon Using a Multi-angle Absorption Photometer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2002, 4, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Petzold, A.; Schönlinner, M. Multi-angle absorption photometry—a new method for the measurement of aerosol light absorption and atmospheric black carbon. J. Aerosol Sci. 2004, 35(4), 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Schloesser, H.; Sheridan, P.J.; Arnott, P.; Ogren, J.A.; Virkkula, A. Evaluation of multiangle absorption photometry for measuring aerosol light absorption. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, D.C.; K. Ropkins. openair — an R package for air quality data analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 27-28, 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, D.C. The openair manual — open-source tools for analysing air pollution data. Manual for version 2.6-6, 2019, University of York.

| Parameters | Description / Values |

|---|---|

| Laser source | Nd: YAG solid-state laser |

| Wavelength | 1064 nm |

| Operating mode | Pulsed |

| Pulse energy | 7 µJ |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 5–7 kHz |

| Filter bandwidth | 1 nm |

| Field of view receiver | 0.45 mrad |

| Type | G2401 | MAAP | Fidas | WXT520 | Nimbus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | 86.27% | 88.88% | 98.69% | 100% | 66.66% |

| Hours | 81.26 % | 89.1% | 97.76% | 99.7% | 59.47% |

| Months | East. Synoptic | West. Synoptic | Breeze | NC Breeze |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | 4 | 15 | 1 | 0 |

| June | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| July | 2 | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| August | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

| September | 0 | 7 | 17 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).