Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

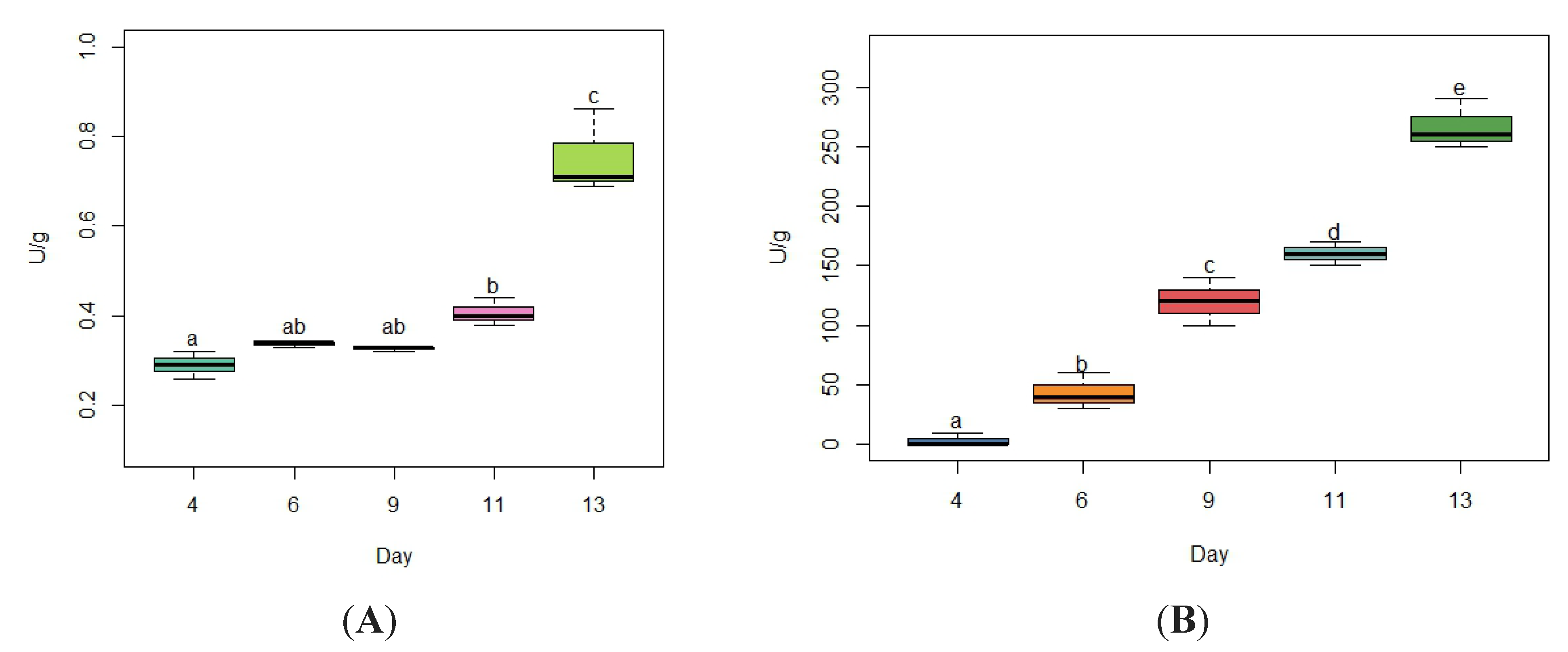

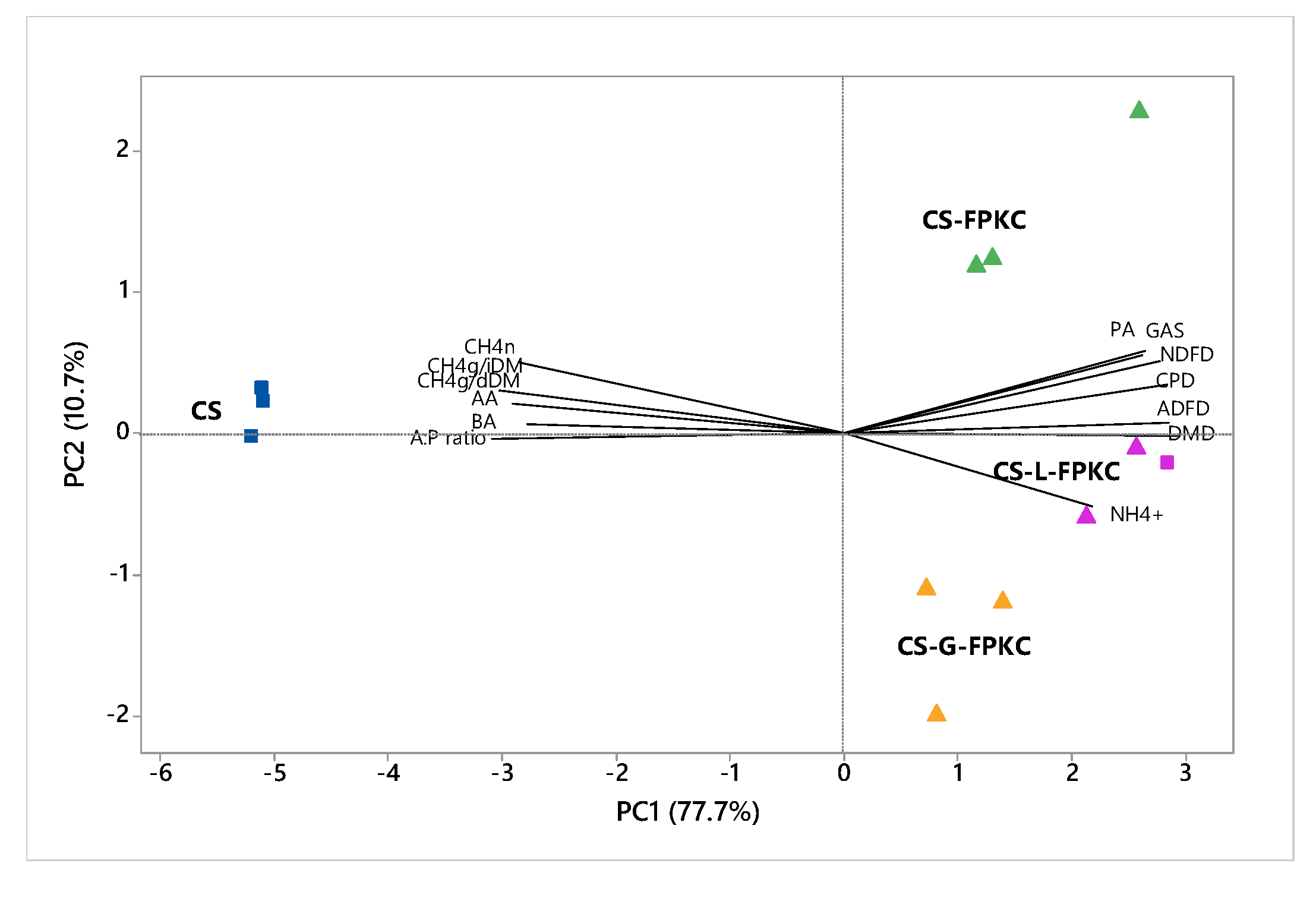

Agro-industrial lignocellulosic waste can be bioconverted to fungal biomass and then utilized as an alternative feed for ruminants, with potential for ruminal methane (CH4) mitigation. This study evaluated the changes in the enzymatic expression and nutritional value of palm kernel cake fermented with Pleurotus ostreatus (FPKC), as well as the differences in the in vitro fermentation parameters and methane production in diets based on tropical forages with the inclusion of FPKC and/or tropical forage legumes. The highest activity of laccases and cellulases occurred on day 13 with values of 0.75 ± 0.09 U/g and 266.7 ± 20.8 U/g, respectively. The biological pretreatment decreased (p< 0.05) the contents of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF) and lignin by 29%, 20.5% and 46.6% respectively, while those of crude protein (CP) increased by 69.6%. The inclusion of FPKC and legumes increased (p<0.05) the degradation of DM (DMD), NDF degradability, ADF degradability and CP degradability in the range of 16.9% to 17.3%, 10.9% to 23.8%, 25.7% to 27.5 % and 11.6% to 30.4%, respectively. Production of acetate decreased (p < 0.05) and that of propionate increased (p < 0.05), resulting in a low A:P ratio in the FPKC diets. The total synthesis of CH4, CH4/g incubated DM and mL CH4/g degraded DM decreased (p< 0.05) in the diets with FPKC and legumes between 15% to 24.3%, 15.6% to 24.9% and 27.3% to 35.9%, respectively. In conclusion, the combination of FPKC with legume species in tropical diets for ruminants reduces in vitro methane emissions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Solid State Fermentation of Palm Kernel Cake

2.3. Spectrometric Analysis of Enzyme Activity

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

2.5. Formulation of Experimental Diets

2.6. Chemical Composition of Palm Kernel Cake, Individual Forages and Experimental Diets

2.7. Short-Term (48-h) In Vitro Rumen Fermentation

2.8. In Vitro Rumen Degradability of Nutrients and Ammoniacal Nitrogen (N-NH3) Quantification

2.9. Gas and Methane (CH4) Volume Measurement

2.10. Determination of the Concentration of Volatile Fatty Acids (VFA)

2.11. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cellulase and Laccase Enzyme Activity

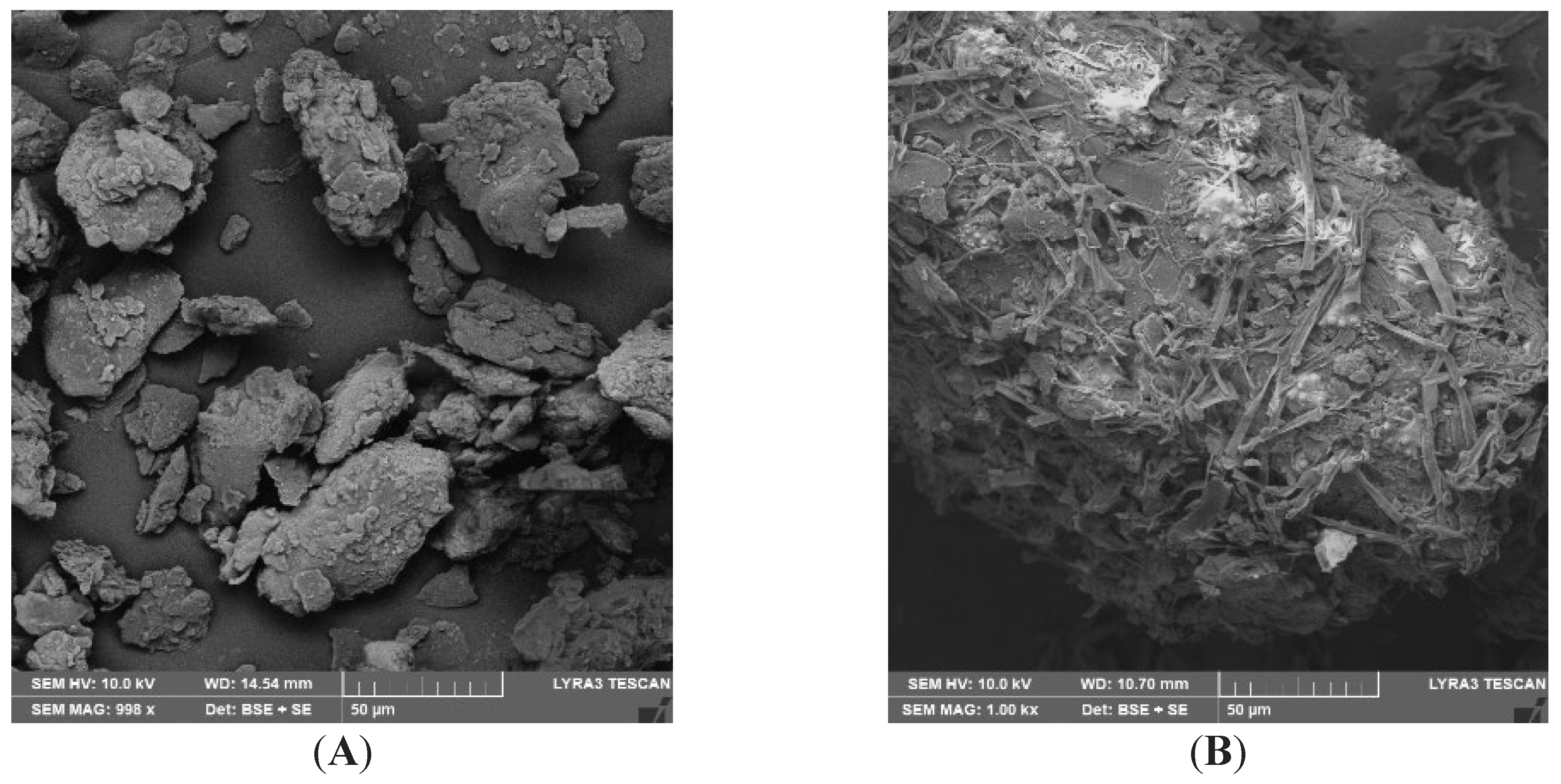

3.2. SEM Analysis

3.3. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of the Substrates and Diets Evaluated

3.4. Gas Production, Methane Synthesis and Parameters of Short-Term In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nabuurs, GJ.; Mrabet, A.; Abu Hatab, M.; Bustamanye, H.; Clark, P.; Havlik, J.; House, C.; Mbow, KN.; Ninan, A.; Popp, S.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). in Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change; Malley, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA. 2022, 747–860. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. An Eye on Methane – The road to radical transparency: International methane Emission Observatory. Nairoi, Africa, 2023. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/44129.

- Astudillo-Neira, R.; Muñoz-Nuñez, E.; Quiroz-Carreno, S.; Avila-Stagno, J.; Alarcon-Enos, J. Bioconversion in Ryegrass-Fescue Hay by Pleurotus ostreatus to Increase Their Nutritional Value for Ruminant. Agriculture 2022, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamke, J.; Kittelmann, S.; Soni, P.; Li, Y.; Tavendale, M.; Ganesh, S.; Janssen, PH.; Shi, W.; Froula, J.; Rubin, EM.; et al. Rumen metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of low methane yield sheep reveals a Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterised by lactic acid formation and utilisation. Microbiome 2016, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, DE.; Ward, GM. Estimates of animal methane emissions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1996, 42, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Palencia, L.; Sánchez Pulido, A.; Moreno Quitian, H.; Torres Triana C., F. y Manrique Luna, D. Intensidad de Emisiones por Unidad de Producto para la Ganaderia Bovina en Colombia. 2021. Available: https://biocarbono.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/03-intensidad-emisiones-unidad-producto-ganaderia-bovina-colombia.pdf.

- Calvin, K.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Rondón, AJ.; Fragoso-Castilla, PJ.; Giraldo-Valderrama, LA.; Mojica-Rodríguez, JE. Effect of tropical forage species in silvopastoral arrangements on methane production and in vitro fermentation parameters in a RUSITEC system. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Pecuarias. 2022, 35, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Botero, IC.; Arroyave-Jaramillo, J.; Valencia-Salazar, S.; Barahona-Rosales, R.; Aguilar-Pérez, CF.; Ayala, A.; Arango, J.; Ku-Vera, JC. Effects of tannins and saponins contained in foliage of Gliricidia sepium and pods of Enterolobium cyclocarpum on fermentation, methane emissions and rumen microbial population in crossbred heifers. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2019, 251, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candyrine, SCL. ; Mahadzir, MF.; Garba, S.; Jahromi, MF.; Ebrahimi, M.; Goh, YM.; Samsudin, AA.; Sazili, AQ.; Chen, WI.; Ganesh, S.; et al. Effects of naturally-produced lovastatin on feed digestibility, rumen fermentation, microbiota and methane emissions in goats over a 12-week treatment period. PLoS One 2018, 13, 7–e0199840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Vargas, JA.; Mezzomo, R. Effects of palm kernel cake on nutrient utilization and performance of grazing and confined cattle: a meta-analysis. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2023, 55, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, LV.; Silva, RR.; Silva, FF.; Silva, JW.; Barroso, DS.; Silva, AP.; Souza, SO.; Santos, MC. Increasing levels of palm kernel cake (Elaeis guineensis jacq.) in diets for feedlot cull cows. Chil J Agric Res. 2019, 79, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moftah, B.; Lah, T.; Nawi, A.; Kadir, M.; Aliyu-Paiko, M. Maximizing Glucose Production From Palm Kernel Cake (Pkc) From Which Residual Oil Was Removed Supercritically Via Solid State Fermentation (Ssf) Method Using Trichoderma Reesi Isolate Pro-A1. Internet J. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fitriyah, F.; Aziz, MA.; Wahyuni, S.; Fadila, H.; Permana, IG.; Priyono. ; Siswanto. Nutritional improvement of oil palm and sugarcane plantation waste by solid-state fermentation of Marasmiellus palmivorus. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. 2022, 974, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, JA.; Chand, N.; Naz, S.; Alhidary. IH.; Khan, RU.; Batool, S.; Zelai, NT.; Pugliese, G.; Tufarelli, V.; Losacco, C. Dietary Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Waste Inhibits Experimentally Induced Eimeria tenella Challenge in Japanese Quails Model. Animals 2023, 13, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzahra, YR.; Toharmat, T.; Prihantoro, I. Bio-processing Plantation by-products with White Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) to Improve Fermentability and Digestibility Based on Substrate Type and Fermentation Time. Buletin Peternakan 2022, 46, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, AML. ; Chin, CF.; Seelan, JS.; Chye, FY.; Lee, HH.; Rakib, MR. Metabolites profiling of protein enriched oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm.) grown on oil palm empty fruit bunch substrate. LWT 2023, 181, 114731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhabiba, Nuraini. ; dan Mirzah. Performance of Broiler Given Palm Oil Waste Fermented with Pleurotus Ostreatus In Ration. Quest J Res Agric Anim Sci. 2021, 8, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Panngoen, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Rachtanapun, P.; Chakrabandhu, Y.; Jinsiriwanit, S. Integration of white rot mushroom cultivation to enhance biogas production from oil palm kernel pulp by solid-state digestion. Front Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1204825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, BO.; Egigba, GO.; Bamikole, MA.; & Ezenwa, IV.; & Ezenwa, IV. ; Chemical Composition and in vitro Fermentation of Raw and Biodegraded Oil Palm Pressed Fibre (PPF) and PPF-Based Diets. Int Res J Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Rubiano-Orozco, LA.; Castro-Pacheco, Ac.; Jiménez-Rojas, F.; Fragoso-Castilla, Pj.; Ibarra-Rondón, Aj.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, DM. Evaluación de la actividad lignocelulolítica de hongos cultivados en subpro- ductos de la palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis). Biotecnol Sect Agropecu Agroind. 2024, 22, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Guo, Q.; Xu, R.; Dong, H.; Zhou, C.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Wu, X. Loop optimization of Trichoderma reesei endoglucanases for balancing the activity–stability trade-off through cross-strategy between machine learning and the B-factor analysis. GCB Bioenergy. 2023, 15, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sequeda, D.; Suspes, D.; Maestre, E.; Alfaro, M.; Perez, G.; Ramírez, C.; Pisabarro, AG.; Sierra, R. Effect of Nutritional Factors and Copper on the Regulation of Laccase Enzyme Production in Pleurotus ostreatus. J. of Fungi. 2021, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, S.; Cristian Garita, C.; Esquivel, C.; Villegas, LR. Aislamiento y Purificación de La Enzima Lacasa: Evaluación de Su Potencial Biodegradador En Residuos Agrícolas. Rev Soc Mex Biotecnol Bioingen. 2020, 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada López, I.; Esparza Jiménez, S.; Albarrán Portillo, B.; Yong Angel, G.; Rayas Amor, A.; García Martínez, A. Evaluación productiva y económica de un sistema silvopastoril intensivo en bovinos doble propósito en Michoacán, México. CIENCIA ergo sum 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia Diaz, E.; Mahecha Ledesma, L.; Angulo Arizala, J. Consumo de materia seca en un sistema silvopastoril de Tithonia diversifolia en trópico alto. Agronomía Mesoamericana 2017, 28, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozin, S.; Hatta, U.; Tantu, R.; Tahir, M.; Damayanti, AP.; Sundu, B. Crude Enzymes Produced by Fungi Improved Performance, Feed Digestibility, and Breast Percentage of Palm Kernel Meal-Fed Broilers. AIP AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2628, 140003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza Nieto, C.; Mayorga Mogollón, OL.; Parra Forero, DM.; Camargo Hernández, DB.; Buitrago Albarado, CP.; Moreno Rodríguez, JM. Tecnología NIRS para el análisis rápido y confiable de la composición química de forrajes tropicales. Corp Colom Invest Agropecu (Agrosavia). 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, MK.; Williams, BA.; Dhanoa, MS.; Mcallan, AB.; France, JA. Simple gas production method using a pressure transducer to determine the fermentation kinetics of ruminant feeds. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1994, 48, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, PJ.; Robertson, JB.; Lewis, BA. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, JA.; Givens, DI. Studies on in Situ Degradation of Feeds in the Rumen: 1. Effect of Species, Bag Mobility and Incubation Sequence on Dry Matter Disappearance. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol.. 1997, 64, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, NL.; Olson, VM.; Schwab, CG.; Chesbro, WR.; Cunningham, KD.; Lykos, T. Improved Techniques for Dissociating Particle-Associated Mixed Ruminal Microorganisms from Ruminal Digesta Solids. J Anim Sci. 1994, 72, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Preprint at 2023. https://www.R-project.

- Rueda, AM.; López, Y.; Vincent, AT.; Létourneau, M.; Hernández, I.; Sánchez, CI.; Molina, D.; Ospina, SA.; Veyrier, FJ.; Doucet, N. Genome sequencing and functional characterization of a Dictyopanus pusillus fungal enzymatic extract offers a promising alternative for lignocellulose pretreatment of oil palm residues. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, MA.; Yusof, MT.; Zunita, Z.; Hassim, HA. Enhancing the utilization of oil palm fronds as livestock feed using biological pre-treatment method. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 230, 012077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraini, Djulardi, A. ; Trisna, A. Palm oil sludge fermented by using lignocellulolytic fungi as poultry diet. Int J Poult Sci. 2017, 16, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, Y.; Siddiqui, Y.; Idris, AS. Comprehensive studies on optimization of ligno-hemicellulolytic enzymes by indigenous white rot hymenomycetes under solid-state cultivation using agro-industrial wastes. J Environ Manage. 2020, 259, 110056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, EA.; Mendes, TD.; Pacheco, TF.; Wischral, D.; dos Santos, DC.; Mendonça, S.; Camassola, M.; de Siquiera, FG.; Souza, MT. Colonization of oil palm empty fruit bunches by basidiomycetes from the Brazilian cerrado: Enzyme production. Energy Sci Eng. 2022, 10, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, NR.; Rudiyansyah. ; & Gusrizal, G. Microbial Degradation of Lignocellulose in Empty Fruit Bunch at Various Incubation Time. J Trop Biodivers Biotechnol. 2022, 7, jtbb69743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fithri, L.; Puspaningsih, N.; Asmarani, O.; Ni’matuzahroh. ; Dewi, G.; Arizandy, RY. Characterization of Fungal Laccase Isolated from oil palm empty fruit bunches (OPEFB) and Its Degradation from The Agriculture Waste. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020, 27, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaain, ENN. ; Bahrin, EK.; Ibrahim, MF.; Ando, Y.; Abd-Aziz, S. Biological pretreatment of oil palm empty fruit bunch by Schizophyllum commune ENN1 without washing and nutrient addition. Processes 2019, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksong, W.; Wongfaed, N.; Sangsri, B.; Kongjan, P.; Prasertsan, P.; Podmirseg, SM.; Insam, H.; O-Thong, S. Enhanced solid-state biomethanisation of oil palm empty fruit bunches following fungal pretreatment. Ind Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-Nazratul, FMY. ; Rakib, MRM.; Zailan, MZ.; Yaakub, H. Enhancing in vitro ruminal digestibility of oil palm empty fruit bunch by biological pre-treatment with Ganoderma lucidum fungal culture. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0258065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusli, ND.; Ghani, AA.; Mat, K.; Yusof, MT.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Hassim, HA. The Potential of Pretreated Oil Palm Frond in Enhancing Rumen Degradability and Growth Performance: A Review. Adv Anim Vet Sci. 2021, 9, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedousi, M.; Melanouri, EM.; Diamantopoulou, P. Carposome productivity of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii growing on agro-industrial residues enriched with nitrogen, calcium salts and oils. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2023, 6, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cateni, F.; Gargano, ML.; Procida, G.; Venturella, G.; Cirlincione, F.; Ferraro, V. Mycochemicals in wild and cultivated mushrooms: nutrition and health. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 339–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, G.; Berna, E. Comparison of amino acid content in canned Pleurotus ostreatus and Agaricus bisporus mushrooms. Veg. Crops Res. Bull. 2011, 74, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaye, AE.; Ajani, EJ.; Emikpe, BO.; Folorunso, LA. Incidence and Prevalence of Naturally Occuring Fungi on Palm Kernel Sludge and Its Attendant in Vitro Digestibility. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Alshelmani, MI.; Kaka, U.; Abdalla, EA.; Humam, AM.; Zamani, HU. Effect of feeding fermented and non-fermented palm kernel cake on the performance of broiler chickens: a review. World's Poult. Sci. 2021, 77, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazla, R.; Jamarun, N.; Agustin, F.; Zain, M.; Arief. ; Cahyani, NO. Effects of supplementation with phosphorus, calcium and manganese during oil palm frond fermentation by Phanerochaete chrysosporium on ligninase enzyme activity. Biodiversitas 2020, 21, 1833–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xiong, B.; Zhao, X. Could propionate formation be used to reduce enteric methane emission in ruminants? Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 855, 158867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Harstad, O. M.; McAllister, T.; Dörsch, P.; Holo, H. Propionic acid bacteria enhance ruminal feed degradation and reduce methane production in vitro. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2020, 69, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert-Williams, A. R.; McConnell, H.L.; Salisbury, C.M.; Lindholm-Perry, AK.; Lalman, D.L.; Pezeshki, A.; Foote, A.P. Effects of adding ruminal propionate on dry matter intake and glucose metabolism in steers fed a finishing ration. J Anim Sci. 2023, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, KA.; Ungerfeld, EM.; Eckard, RJ.; Wang, M. Review: Fifty years of research on rumen methanogenesis: Lesson learned and future challenges for mitigation. Animal 2020, 14, S2–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltan, YA.; Morsy, AS.; Lucas, RC.; Abdalla, A. L. Potential of mimosine of Leucaena leucocephala for modulating ruminal nutrient degradability and methanogenesis. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2017, 223, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, G.; Peixoto, N.; Arruda, H.; de Paulo, D.; Molina, G.; Pastore, G. Phytochemicals and biological activities of mutamba (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.): A review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maweu, AN.; Bebe, BO.; Kuria, SG.; Kashongwe, OB. In-vitro digestibility and methane gas emission of indigenous and introduced grasses in the rangeland ecosystems of south eastern Kenya. Reg Environ Change. 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archimède, H.; Eugène, M.; Marie Magdeleine, C.; Boval, M.; Martin, C.; Morgavi, DP.; Lecomte, P.; Doreau, M. Comparison of methane production between C3 and C4 grasses and legumes. Animal Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral Júnior, JM.; Guerreiro Martorano, L.; de Souza Nahúm, B.; Gomes de Castro, VC.; Fernandes Sousa, L.; de Carvalho 891 Rodrigues, TCG. ; Rodrigues da Silva,JA.; da Costa Silva, AL.; Lourenço Júnior, J.; Berndt, A.; Maciele e Silva, AG. Feed Intake, Emission of Enteric Methane and Estimates, Feed Efficiency, and Ingestive Behavior in Buffaloes Supplemented with Palm Kernel Cake in the Amazon. Biome 2022, 9, 1053005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanibada, B.; Hohenester, U.; Pétéra, M.; Canlet, C.; Durand, S.; Jourdan, F.; Boccard, J.; Martin, C.; Eugène, M.; Morgavi, DP.; Boudra, H. Inhibition of enteric methanogenesis in dairy cows induces changes in plasma metabolome highlighting metabolic shifts and potential markers of emission. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 15591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvant, D.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Serment, AA.; Broudiscou, L. Influences des régimes et de leur fermentation dans le rumen sur la production de méthane par les ruminants. INRA Prod. Anim. 2011, 24, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Masaki, T.; Ikuta, K.; Iwamoto, E.; Nishihara, K.; Hirai, M.; Uemoto, Y.; Terada, F.; Roh, S. Physiological responses and adaptations to high methane production in Japanese Black cattle. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 11154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, KA.; Johnson, DE. Methane Emissions from Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, MM. Using nutritional strategies to mitigate ruminal methane emissions from ruminants. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrego-Gacía, A.; Poggi-Varaldo, HM.; Robles-González, V.; Ponce-Noyola, T.; Calva-Calva, G.; Ríos-Leal, E.; Estrada-Bárcenas, D.; Mendoza-Vargas, A. Lovastatin as a supplement to mitigate rumen methanogenesis: an overview. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, AM.; Qazi, IH.; Matra, M.; Wanapat, M. Role of Chitin and Chitosan in Ruminant Diets and Their Impact on Digestibility, Microbiota and Performance of Ruminants. Fermentation 2022, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanegara, A.; Novandri, B.; Yantina, N.; Ridla, M. Use of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) to substitute soybean meal in ruminant diet: An in vitro rumen fermentation study. Vet World. 2017, 10, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiegbu, FO.; Morrison, IM.; Paterson, A.; Smith, JE. Analyses of fungal fermentation of lignocellulosic substrates using continuous culture rumen simulation. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1994, 40, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diets |

Megathyrsus maximus |

Leucaena leucocephala |

Guazuma ulmifolia |

NFPKC | FPKC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| CS-L | 70 | 30 | - | - | - |

| CS-G | 70 | - | 30 | - | - |

| CS-NFPKC | 80 | - | - | 20 | - |

| CS-FPKC | 80 | - | - | - | 20 |

| CS-L-FPKC | 70 | 10 | - | - | 20 |

| CS-G-FPKC | 70 | - | 10 | - | 20 |

| Chemical composition (% DM) | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| OM | 92.44 | 89.65 |

| ASH | 3.44 | 6.47 |

| EE | 12.46 | 6.83 |

| CP | 15.95 | 27.05 |

| NDF | 73.0 | 49.5 |

| ADF | 40.32 | 32.08 |

| LIG | 14.5 | 7.74 |

| Parameters, % DM | Diets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | CS-L | CS-G | CS-NFPKC | CS- FPKC |

CS-L- FPKC |

CS-G-FPKC | |

| CP | 9.36 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 15.25 | 10.75 | 14.41 | 12.81 |

| NDF | 66.00 | 56.0 | 60.7 | 59.72 | 62.01 | 59.82 | 57.12 |

| ADF | 37.99 | 30.8 | 34.9 | 32.84 | 33.43 | 31.85 | 30.88 |

| PARAMETERS | DIETS | p - Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | CS-L | CS-G | CS- NFPKC |

CS- FPKC |

CS-L- FPKC |

CS-G- FPKC |

||

| % DMD | 51.4±0.95a | 59.5±0.96 b | 59.52±1.05b | 50.0±1.23 a | 60.0±3.87 b | 60.6±1.07 b | 60.5±2.32b | <0.001 |

| % NDFD | 45.6±0.85a | 51.1±1.53 b | 50.2±0.32 b | 44.9±1.31a | 56.5c ±4.21 | 55.2c ±1.21 | 50.6±1.04b | <0.001 |

| % ADFD | 40.0±3.53a | 47.2b±1.78c | 47.7c±0.64b | 43.7±1.29ab | 51.0±4.75c | 50.4±1.34c | 50.3±0.98c | 0.0007 |

| % CPD | 50.5±0.81a | 66.3±1.58b | 57.8±0.84c | 53.5±1.05d | 63.0±3.58b | 65.9±0.93b | 56.4±0.65c | <0.001 |

| pH | 6.54±0.08 | 6.57±0.005 | 6.62±0.06 | 6.65±0.03 | 6.64±0.07 | 6.6±0.04 | 6.62±0.05 | 0.18 |

| N – NH3 (mg /dL) | 14.5±0.18a | 15.9±0.48ab | 14.9±0.64a | 14.6±0.4a | 15.3±0.23ab | 17.2±0.43c | 16.1±1.27bc | <0.001 |

| Acetic acid (mmol/L) | 20.4±1.14a | 16.1±0.69bc | 16.4±0.49bc | 16.2±1.2bc | 16.8±0.55b | 15.2±0.4c | 16.4±0.5bc | <0.001 |

| Propionic acid (mmol/L) | 7.6±2.28a | 8.76±0.39b | 8.93±0.78b | 9.72±0.07cd | 10.1±0.23ec | 9.22±0.31bc | 8.61±0.25b | <0.001 |

| Butyric acid (mmol/L) | 3.73±0.40a | 2.78±0.05b | 2.64±0.26b | 2.62±0.20b | 2.62±0.2b | 2.68±0.15b | 2.76±0.2b | <0.001 |

| Acetate/propionate ratio | 2.65±0.13 | 1.88±0.15 | 1.89±0.23 | 1.70±0.13 | 1.68±0.04 | 1.69±0.02 | 1.81±0.09 | <0.001 |

| Gas produced (mL) | 85.8±2.25a | 95.7±0.5b | 95.2±1.13b | 88.1±2.03c | 98±1.61b | 96±1.46b | 89.8±0.88c | <0.001 |

| CH4 produced (mL) | 14.0±0.07a | 11.6±0.53b | 11.4±0.49b | 12.5±0.62c | 11.9±0.22b | 10.8±0.27d | 10.6±0.32d | <0.001 |

| mL CH4/g incubated DM | 28.1±0.13a | 22.2±0.3b | 22.7±0.92b | 23.6±0.96c | 23.7±0.43c | 21.6±0.55d | 21.1±0.64d | <0.001 |

| mL CH4/g degraded DM | 54.6±1.26a | 36.3±1.5b | 37.5±3.4b | 38.8±1.6bc | 39.7±1.81bc | 35.7±1.40cd | 35.0±2.01d | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).