Introduction

Aquaculture is one of the fastest-growing food production sectors, providing a sustainable protein source for humans worldwide. Global aquaculture production reached 97.2 million tons in 2013 [

1]. Farmed fish production, including finfish, crustaceans, mollusks, and other aquatic animals, accounted for 70.2 million tons, reflecting a 5.6% increase from 66.5 million tons in 2012. Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) production increased by 70.2% between 2010 and 2018 to meet the global demand for fish [

2]. In Egypt, tilapia aquaculture represents 42% of global aquaculture fish production and 64% of Egypt's total fish production [

3].

However, tilapia farming faces significant challenges in regions with low winter temperatures. The optimal growth temperature for most tilapia species is 25–28°C, and temperatures below 20°C impair feeding, while reproduction halts at 22°C. Tilapia cannot survive prolonged exposure to temperatures below 10–12 °C [

4]. Cold winters in subtropical regions, including Egypt, lead to poor growth and mass mortality, hindering aquaculture productivity [

5].

Previous studies on tilapia cold tolerance may not completely capture natural stress responses as they relied on laboratory experiments [

6]. For example, the cold tolerance of three Nile tilapia strains was lower than that of strains introduced into China, which were naturally subjected to cold temperatures over several years. This merit suggests that natural selection for cold tolerance may have occurred. Additionally, Nile tilapia subjected to successive cold stress over multiple generations showed changes in the levels of genomic DNA methylation, resulting in significant epigenetic changes that could be inherited [

7]. Understanding the underlying genetic architecture and epigenetic mechanisms governing this trait is essential for developing breeding programs aiming to improve resilience to cold temperatures.

The genetic architecture of cold tolerance is not well understood, possibly because of the limited marker density that was used in previous studies, which mainly relied on microsatellites, AFLP markers, and small SNP datasets [

8,

9,

10]. Recent technologies such as low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (lcWGS) with genotype imputation offer a more robust approach to identifying genetic variants associated with the desired phenotypes. Thus, this study aims to use lcWGS to identify genetic markers for cold tolerance in Nile tilapia that could be used in breeding programs to develop cold-tolerant lines to mitigate winter-related mortality in aquaculture systems.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The fish utilized in this study were sampled in accordance with the standard operating procedures for the care and use of research animals, as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Central Laboratory for Aquaculture Research (CLAR). Every effort was made to minimize potential suffering experienced by the fish and ensure their overall welfare was maintained at all times.

Experimental Design

The tilapia fingerlings used in this study were derived from the genetically improved G9 strain from the WorldFish Center in Abbassa, Egypt. The genetic line was originally selected for enhanced growth.

The experiment was conducted under controlled winter and cold conditions at two different locations in Egypt: a rural area near Zagazig city and another near the 10th Ramadan city. These locations were chosen to represent different climatic conditions. The fish were divided into two groups, each housed in separate aquaria to assess their cold tolerance. At the first location, the fish were distributed into 6 aquaria, each with a stock density of 3.24 g/L and an initial average total weight of 227 g per aquarium, with a total of 549 fish at 16.63°C on average. At the Second location, 229 fish with an average weight of 2.9 g each were distributed into 7 aerated aquaria, with 35 fish per aquarium at 16.34°C on average. The fish were fed commercial diets with 30% protein, administered twice daily at a feeding rate of 5% of their total body weight. Water quality was maintained by changing 10% of the water volume daily, and water temperatures were monitored regularly. Fin clips were collected daily from the dead fish and, at the end of the experiment, from the surviving fish at both locations from December 1, 2020, until March 2021.

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

DNA extraction was carried out on fin clips following the salting out protocol, followed by library preparation. Libraries were generated using the Illumina DNA Prep kit. Final libraries were quantified with fluorometry, and library pools were assessed for quality with Fragment Analyzer (Agilent). Adapter sequences utilized for libraries were standard Illumina adapters. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Paired End Reads 2x150).

Phasing and Haplotype Reference Panel Generation

Reference genome assembly O_niloticus_UMD_NMBU (NCBI RefSeq Assembly GCF_001858045.2) was downloaded from NCBI. Gencove removed ALT contigs smaller than 100kb, with the only exception being the inclusion of the Mitochondrial contig. BWA indices were created using `bwa index -a bwtsw`. An index was created using `samtools faidx` [

11]. A Sequence dictionary was created using Picard's `CreateSequenceDictionary`. High depth FASTQs were provided by Neogen via sFTP transfer. Paired end sequences were aligned to the reference assembly using Sentieon Driver's optimized implementation of BWA-MEM [

12]. Variant calling was performed using Sentieon's `Haplotyper` with gVCF output per sample. Joint variant calling was performed using Sentieon's `GVCFtyper`. A maximum of 2 alternate alleles are reported for each site. Loci found to be non-variant persist in the output VCF. From the jointly called VCF, singletons and filtered sites were removed according to various INFO field thresholds, including QD, FS, MQ, MQRankSum, ReadPosRankSum, and SOR. We then filled in sporadic missingness and phase using Beagle. The resulting set of sites was observed in the Gencove Haplotype Reference Panel. DNA sequencing and genotyping were done at the Center for Aquaculture Technologies, San Diego, CA.

SNP Annotation

The software SnpEff v5.1d [

13] was used for SNP annotation. The GTF file of the Nile tilapia reference genome was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and was the basis for constructing a reference database. Subsequently, the SNPs were annotated using the default parameters of SnpEff.

Association Analysis

General linear regression association analysis was performed using PLINK version 1.07 [

14]. To correct for multiple testing, p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method. Subsequently, the qqman package was employed to create a Manhattan plot, visualizing the—log10-transformed p-values from the GWAS analysis [

15].

Open Reading Frames and Domain Analyses

Open reading frames (ORFs) within the genomic DNA sequences corresponding to the most significant SNPs were identified using the NCBI Open Reading Frame Finder (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/). To characterize potential functional domains within the identified ORFs, domain analysis was conducted using the SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) database [

16].

Prediction of MiRNA Recognition Sites

To predict miRNA targets, the target sequences were extracted from the reference genome, and Nile tilapia miRNAs were downloaded from the miRbase database [

17]. Target recognition sites were predicted with default settings using two popular prediction tools, miRanda and PITA, which are available on the sRNAtoolbox small RNA analysis server [

18]. A microRNA target site was considered valid when predicted by both miRanda and PITA. Further filtration based on a minimum energy threshold of -15 kcal/mol was applied for both tools to ensure the reliability of predicted miRNA-target interactions.

Results

Fish Exposure to Winter/Cold

We recorded the survivability, mortality, and average temperatures of fish raised over several weeks at the two different locations. At the first location, water and air temperatures were measured and recorded daily throughout the experiment. The lowest recorded water temperature was 10.4°C, and the highest was 20°C (

Table 1). At the Second location, water temperatures ranged from 12.3°C to 18.8°C, with the lowest temperatures recorded in January (12.3°C) and the highest in November (18.8°C) (

Table 1).

The survivability and mortality rates in relation to the average weekly temperatures are summarized in

Table 1. In location 1, a total of 541 fish were initially used, as shown in Week 1. The number of fish gradually declined to reach 334 by Week 13. The highest mortality of 53 fish was reported in Week 6. In contrast, less mortality was observed in location 2. The experiment started with 234 fish in Week 1 and ended up with 214 fish in Week 15. No dead fish were reported in the first 4 weeks of the experiment. The highest mortality of five fish was recorded during Week 13.

A detailed breakdown of the number of fish, their weights, and stocking density for aquaria (Q1 to Q7) at the two locations (Loc1 and Loc2) are provided in Table 2. For the first location, each aquarium was initially stocked with fish totaling 227 g. This resulted in a consistent stocking density of 3.24 g/L. By the end of the experiment, the number of surviving fish varied, with aquarium Q3 exhibiting the highest survival rate, as indicated by its final fish count (62 fish) and total weight (148 g). By the final days of the experiment, fish reached an average weight of 137.6 g at a stocking density of 1.97 g/L, as shown in Table 2. Also, mortality rates across the aquaria ranged from ~37% to ~43% fish, which might reflect differences in cold tolerance due to genetics or environmental differences.

For location 2, each aquarium was initially stocked with fish totaling 107 g, resulting in a consistent stocking density of 2.8 g/L. By the end of the experiment, the number of surviving fish varied, with aquarium Q3 exhibiting the highest survival rate, as indicated by its final fish count and total weight. At the end of the experiment, the fish reached an average weight of 91 g at a stocking density of 2.4 g/L (Table 2). Also, mortality rates across the aquariums ranged from 2 to 5 fish. This suggests that the fish at this location demonstrated better cold tolerance compared to those in location 1.

Cold Stress-Associated SNPs Are Located in a LncRNA on LG16

The sequencing coverage obtained varied from 0.22× to 0.97×, with an average of 0.67×. All sequence reads were used for genotype imputation, yielding 29,334,544 imputed genotypes (SNPs and INDELS). Following quality filtering, 7,300,252 biallelic SNPs were retained for downstream analysis.

A total of 843,982 SNPs had minor allele frequencies (MAFs) of ≤ 0.05, while 6,677,956 SNPs had MAFs >0.05. The ratio of transitions to transversions was 1.57. SNP annotation using SnpEff indicated that 543,166 SNPs are missense variants, and 4,286 are splice junction variants. Additionally, 7,829,854 of the SNPs were found in introns.

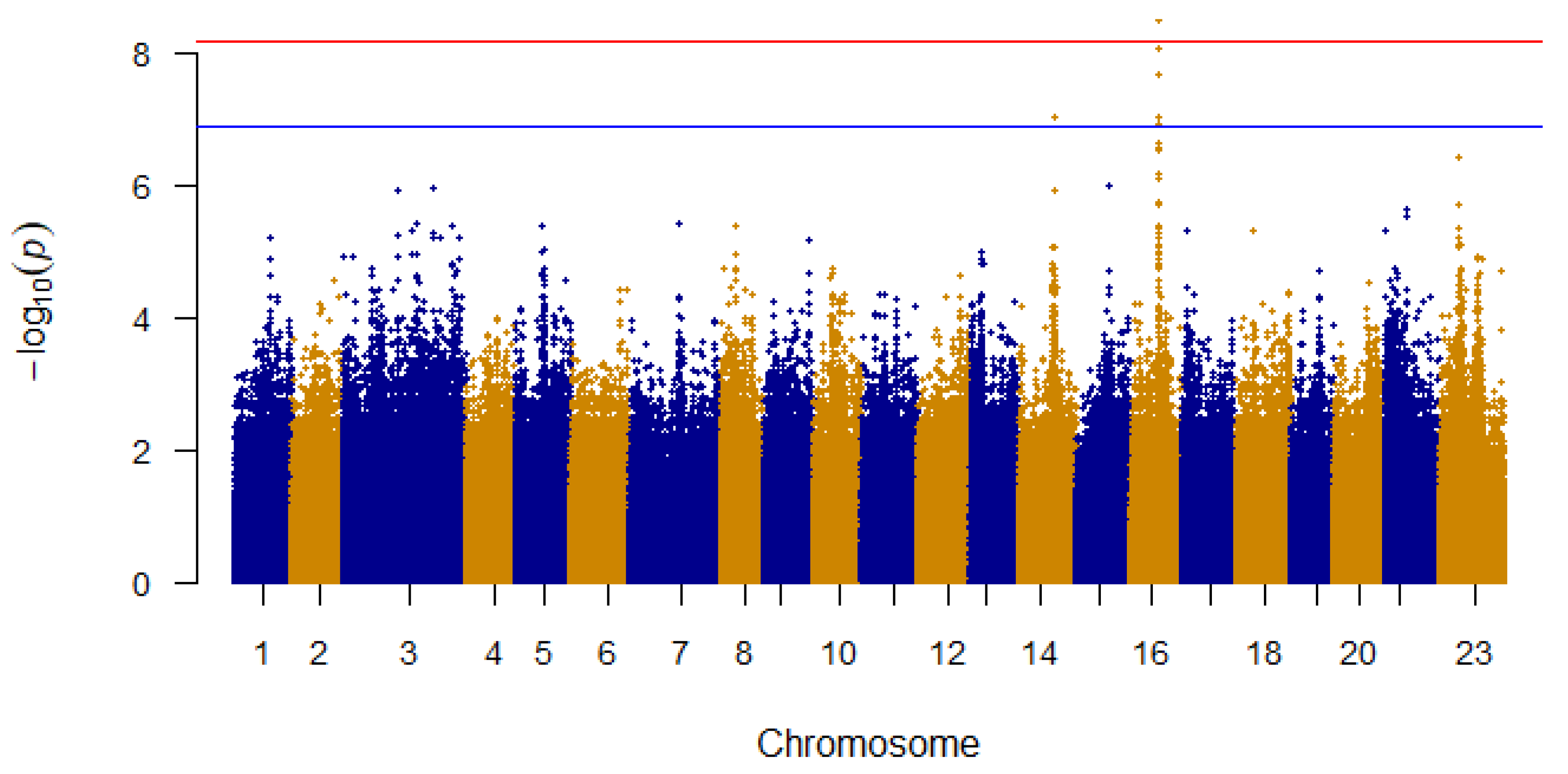

To pinpoint individual SNP markers linked to cold survivability, a total of 7,300,252 filtered variants underwent a comprehensive general linear regression analysis. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, several variants were identified as significantly associated with cold tolerance. Notably, three SNPs in linkage group 16 (LG16) exceeded the genome-wide significance threshold of 6.85×10

−9, whereas eight other SNPs showed significant associations with cold resistance at the suggestive significance threshold of 1.37×10

−7 (

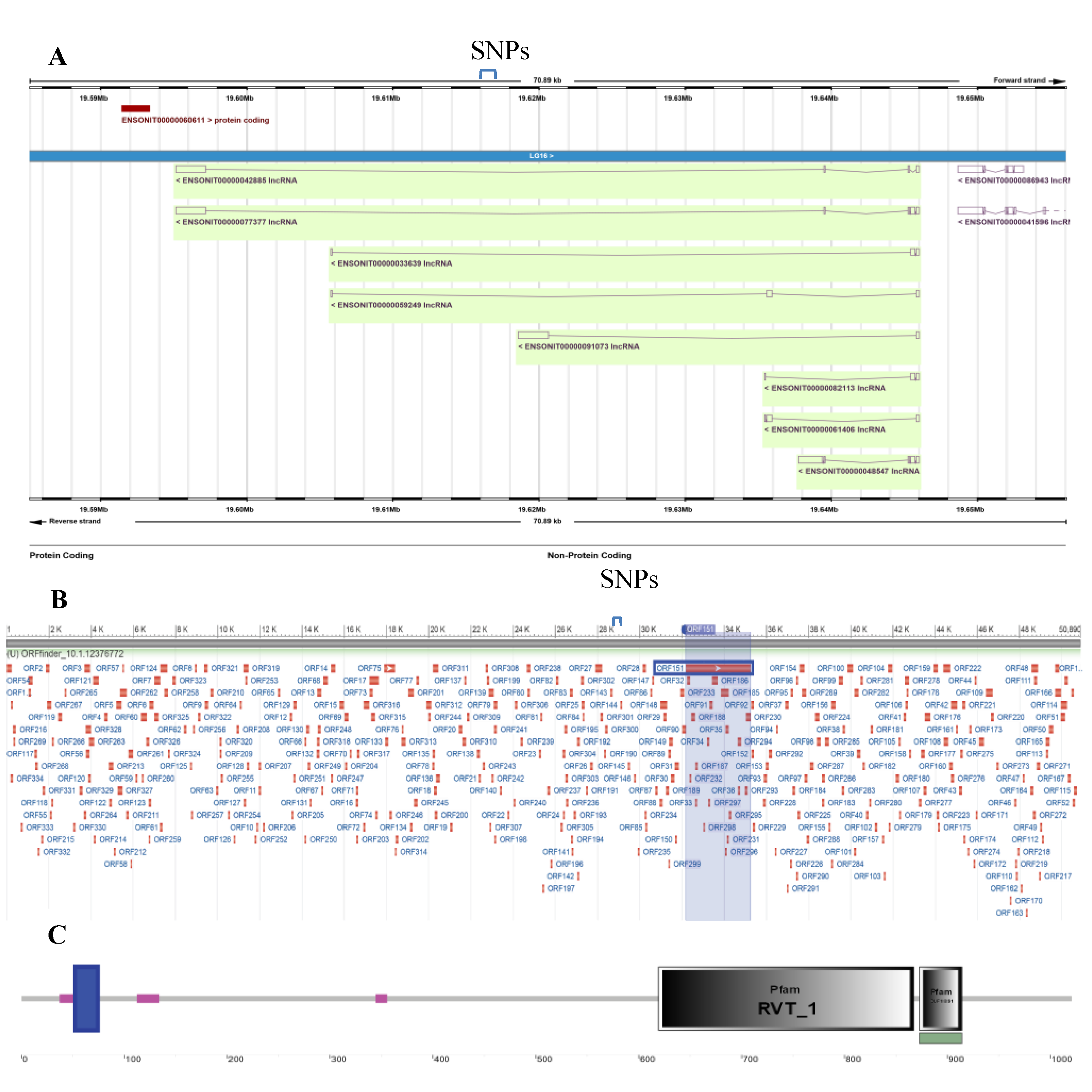

Figure 1). Seven of the suggestive significant SNPs were also situated on LG16. Intriguingly, the top five most significant SNPs on LG16 were found to span less than 400bp of the intronic region of the long noncoding RNA ENSONIG00000042717.1, as evidenced by the Ensembl genome browser annotation (

Figure 2 A).

Although Ensembl annotated this region as noncoding, computational analysis using the Coding Potential Calculator (CPC) revealed significant coding potential (CPC score of 4.51) for the genomic lncRNA region. To gain insights into this region, we searched for ORFs across the full length of the lncRNA (

Figure 2B). The NCBI Open Reading Frame Finder identified 249 potential ORFs. The ORFs size ranged from 30 to 1,021 amino acids with a median length of 44 amino acids. Significant SNPs did not overlap with the predicted ORFs. The largest ORF has two functional protein domains (Reverse Transcriptase Domain - Pfam: RVT_1 and Domain of Unknown Function - Pfam: DUF1891) (

Figure 2C). The RVT_1 domain is commonly identified in reverse transcriptase enzymes, which are linked to retro-transposable elements and retro-viruses.

Further, we sought to investigate the potential functions of the lncRNA ENSONIG00000042717.1. For this purpose, we identified and characterized the nearby genes. Ensembl annotation showed another lncRNA in close proximity to the lncRNA ENSONIG00000042717.1, as well as a neighboring single-exon protein-coding gene, ENSONIG00000028509.1, located on the forward strand (

Figure 2A). This gene encodes a transcript, ENSONIT00000060611.1, which translates into a protein (ENSONIP00000029192) of 653 amino acids (1962 bp). Domain analysis of the protein ENSONIP00000029192 revealed conserved regions, including reverse transcriptase and DNA/RNA polymerase domains, characteristic of retro-transposable elements (

Table 3), which are known to contribute to genetic diversity and evolutionary processes [

19].

Genetic Variations in miRNA Target Sites

We further aimed to explore the potential mechanism of action of the lncRNA ENSONIG00000042717.1. For this, we considered two mechanisms: namely, lncRNA-mRNA and lncRNA-miRNA interactions. Notably, lncTar predictions revealed no potential interaction between lncRNA ENSONIG00000042717.1 and the nearby coding gene ENSONIG00000028509.1. We then investigated lncRNA-miRNA interactions (molecular sponging), where lncRNAs sequester miRNAs to regulate target gene expression. To assess whether ENSONIG00000042717.1 functions as a miRNA sponge [

20], we conducted a thorough search to identify potential miRNA target sites using the flanking sequences surrounding the significant SNPs in association with cold stress.

Of the top five variants significantly associated with cold tolerance in tilapia, four SNPs were located within the miRNA recognition element seed site (MRESS) of the target lncRNA ENSONIG00000042717.1. These SNPs were found to alter miRNA-lncRNA interactions by disrupting existing miRNA binding sites or creating novel illegitimate targets. The analysis revealed alleles that potentially interfered with miRNA-target lncRNA interactions for miR-133b, miR-10573b, miR-10573c, miR-139, and miR-10832. For instance, both alleles of the SNP at LG16:19617272 were found to potentially disrupt miRNA recognition sites. Specifically, the T allele destroyed the MRESS for miR-10573b and miR-10573c, while the G allele disrupted the binding site for miR-139. We observed that the G allele, which disrupts the binding site for miR-139, was 3.4 times more prevalent in dead fish compared to surviving fish. In contrast, the T allele, which impairs the binding site for miR-10573c, was 2.6 times more common in surviving fish than in those that died. This suggests that the two alleles may have opposing regulatory effects on these miRNAs in the cold stress response pathway.

Table 4 lists the SNPs in lncRNA that either disrupt or create MRESS.

Discussion

The concept of Winter Stress Syndrome was introduced by Lemly (1993). It refers to the metabolic distress in warm-water fish when subjected to cold temperatures. In this study, Nile tilapia transfer from 25°C to ~16°C initiated an exhausted behavior and loss of equilibrium for about an hour. This response aligns with previous observations reported in red tilapia [

21].

Temperature tolerance is a critical trait in aquaculture, which influences the growth, survival, and overall performance of the fish. Research conducted by Charo-Karisa et al. [

5] and Baer and Travis [

22] emphasizes difficulties in the genetic improvement of cold tolerance using traditional methods, revealing that the heritability values for cold tolerance in juvenile Nile tilapia are notably low, specifically, 0.08 ± 0.17 for cooling degree hours and 0.09 ± 0.19 for the temperature at death. Such findings indicate that relying solely on conventional breeding strategies may not yield significant improvements in temperature tolerance.

Previous studies have identified QTL for cold tolerance in tilapia hybrids, such as O. mossambicus x O. aureus and O. niloticus x S. galilaeus using tens of microsatellites and AFLP markers [

8,

9]. Recently, 1,160 SNP variants were genotyped using ddRAD-Seq, facilitating the identification of a genome-wide significant QTL on LG18 for cold tolerance in GIFT tilapia [

10]. However, the ddRAD-Seq focuses on a specific portion of the genome, which limits genome coverage and flexibility in discovering novel variants [

23]. In contrast, low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (lcWGS) combined with genotype imputation is gaining traction as a more effective alternative[

24]. This approach entails sequencing the entire genome at lower depths, typically between 0.5× and 5×, and subsequently using imputation techniques to fill in the gaps by utilizing reference panels with high-coverage sequences. LcWGS provides greater marker density, mitigates ascertainment bias, and improves genome-wide resolution compared to ddRAD-Seq or SNP arrays, which are constrained by limited locus coverage and possible biases in marker selection [

25].

The main focus of this study was to use lcWGS to find genetic markers related to cold stress in Nile tilapia. The fish were raised in cold conditions at two locations in Egypt (Zagazig and the

10th of Ramadan) to evaluate their cold tolerance. Unlike earlier studies with hybrid tilapia and lower marker densities [

8,

9,

10], this study used much higher marker density that allowed for the identification of new markers tied to cold tolerance. The analysis revealed 7,300,252 filtered SNP markers from cold-tolerant and cold-sensitive fish, with 10 SNPs located in an intronic region of a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) on LG16, showing a significant association with cold stress. In humans, most of the variants identified through GWAS for increased risk of complex diseases are located within noncoding regions of the genome [

26].

SNPs within miRNA (miRNA) target sites can either disrupt or form new binding sites on lncRNAs, which affect miRNA-lncRNA interactions [

27]. The impact of each SNP on these interactions was assessed by predicting miRNA target sites using 100bp around the reference and alternative alleles of the top five most significant SNPs. Our analysis revealed four SNPs with the potential to disrupt existing miRNA target sites or create new potential miRNA target sites, namely miR-139, miR-133b, miR-10573b, miR-10573c, and miR-10832. Surviving fish showed no preference for the alleles that disrupt the interaction between miR-133b and miR-139 with the lncRNA. The role of miRNAs in cold acclimation has been recently explored in fish, including Nile tilapia [

28,

29]. Previous studies have indicated that miR-139 has the potential to alter how mice react to stress [

30]. LncRNA Gomafu acts as a molecular sponge for miRNA139, thereby alleviating the inhibition of Foxo1 [

31], a crucial transcription factor for autonomous cold adaptation [

32].

The cold stress markers identified in this study warrant future evaluation. Conducting evaluations under long-term low-temperature stress will provide a more comprehensive insight into the genetic mechanisms underlying cold stress in tilapia. Furthermore, it is important to verify the genetic markers identified in this specific tilapia line across multiple populations to validate the robustness of these findings and their potential application in breeding programs.

Acknowledgments

Ayman Ammar is acknowledged for his help in overseeing the project activities in Egypt. This publication is derived from the Subject Data supported by NAS, USAID, the Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF-Egypt), and the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MHESR), and any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in the publication are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NAS, USAID, STDF or MHESR.

References

- FAO. Fishmeal market report—May 2016; 2016.

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture; 2020.

- Hassan, B.; El-Salhia, M.; Khalifa, A.; Assem, H.; Al Basomy, A.; El-Sayed, M. Environmental isotonicity improves cold tolerance of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, in Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 2013, 39, 59-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejar.2013.03.004.

- Ernst, D.H.; Watanabe, W.O.; Ellingson, L.J.; Wicklund, R.I.; Olla, B.L. Commercial-Scale Production of Florida Red Tilapia Seed in Low- and Brackish-Salinity Tanks. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 1991, 22, 36-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-7345.1991.tb00714.x.

- Charo-Karisa, H.; Rezk, M.A.; Bovenhuis, H.; Komen, H. Heritability of cold tolerance in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, juveniles. Aquaculture 2005, 249, 115-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.04.029.

- Costa-Pierce, B.A. Rapid evolution of an established feral tilapia (Oreochromis spp.): the need to incorporate invasion science into regulatory structures. Biological Invasions 2003, 5, 71-84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024094606326.

- Zhu, H.P.; Liu, Z.G.; Lu, M.X.; Gao, F.Y.; Ke, X.L.; Huang, Z.H. Screening and identification of microsatellite markers associated with cold tolerance in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Genetics and molecular research : GMR 2015, 14, 10308-10314. https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.August.28.16.

- Cnaani, A.; Hallerman, E.M.; Ron, M.; Weller, J.I.; Indelman, M.; Kashi, Y.; Gall, G.A.E.; Hulata, G. Detection of a chromosomal region with two quantitative trait loci, affecting cold tolerance and fish size, in an F2 tilapia hybrid. Aquaculture 2003, 223, 117-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00163-7.

- Moen, T.; Agresti, J.J.; Cnaani, A.; Moses, H.; Famula, T.R.; Hulata, G.; Gall, G.A.E.; May, B. A genome scan of a four-way tilapia cross supports the existence of a quantitative trait locus for cold tolerance on linkage group 23. Aquaculture Research 2004, 35, 893-904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2004.01082.x.

- Ai, C.H.; Li, B.J.; Xia, J.H. Mapping QTL for cold-tolerance trait in a GIFT-derived tilapia line by ddRAD-seq. Aquaculture 2022, 556, 738273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738273.

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008.

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv: Genomics 2013.

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang le, L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80-92. https://doi.org/10.4161/fly.19695.

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics 2007, 81, 559-575. https://doi.org/10.1086/519795.

- Turner, S.D. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. bioRxiv 2014, 005165. https://doi.org/10.1101/005165.

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D458-D460. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa937.

- Griffiths-Jones, S.; Grocock, R.J.; van Dongen, S.; Bateman, A.; Enright, A.J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, D140-144. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj112.

- Aparicio-Puerta, E.; Gómez-Martín, C.; Giannoukakos, S.; Medina, José M.; Scheepbouwer, C.; García-Moreno, A.; Carmona-Saez, P.; Fromm, B.; Pegtel, M.; Keller, A.; et al. sRNAbench and sRNAtoolbox 2022 update: accurate miRNA and sncRNA profiling for model and non-model organisms. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, W710-W717. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac363.

- Eickbush, T.H.; Jamburuthugoda, V.K. The diversity of retrotransposons and the properties of their reverse transcriptases. Virus research 2008, 134, 221-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.010.

- Ali, A.; Al-Tobasei, R.; Kenney, B.; Leeds, T.D.; Salem, M. Integrated analysis of lncRNA and mRNA expression in rainbow trout families showing variation in muscle growth and fillet quality traits. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 12111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30655-8.

- Behrends, L.L.; Smitherman, R.O. DEVELOPMENT OF A COLD-TOLERANT POPULATION OF RED TILAPIA THROUGH INTROGRESSIVE HYBRIDIZATION. Journal of the World Mariculture Society 1984, 15, 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-7345.1984.tb00150.x.

- Baer, C.F.; Travis, J. Direct and correlated responses to artificial selection on acute thermal stress tolerance in a livebearing fish. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution 2000, 54, 238-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00024.x.

- Andrews, K.R.; Good, J.M.; Miller, M.R.; Luikart, G.; Hohenlohe, P.A. Harnessing the power of RADseq for ecological and evolutionary genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, 81-92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2015.28.

- Liu, S.; Martin, K.E.; Snelling, W.M.; Long, R.; Leeds, T.D.; Vallejo, R.L.; Wiens, G.D.; Palti, Y. Accurate genotype imputation from low-coverage whole-genome sequencing data of rainbow trout. G3 (Bethesda) 2024, 14. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkae168.

- Homburger, J.R.; Neben, C.L.; Mishne, G.; Zhou, A.Y.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V. Low coverage whole genome sequencing enables accurate assessment of common variants and calculation of genome-wide polygenic scores. Genome Medicine 2019, 11, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-019-0682-2.

- Zhang, F.; Lupski, J.R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, R102-110. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv259.

- Gong, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Miao, X.; Guo, A.Y. lncRNASNP: a database of SNPs in lncRNAs and their potential functions in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, D181-186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1000.

- Ji, X.; Jiang, P.; Luo, J.; Li, M.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, B. Identification and characterization of miRNAs involved in cold acclimation of zebrafish ZF4 cells. PloS one 2020, 15, e0226905. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226905.

- Blödorn, E.B.; Martins, A.W.S.; Dellagostin, E.N.; Nunes, L.S.; da Conceição, R.C.S.; Pagano, A.D.; Gonçalves, N.M.; dos Reis, L.F.V.; Nascimento, M.C.; Quispe, D.K.B.; et al. Toward new biomarkers of cold tolerance: microRNAs regulating cold adaptation in fish are differentially expressed in cold-tolerant and cold-sensitive Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2024, 589, 740942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.740942.

- Su, B.; Cheng, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, B. MicroRNA-139-5p acts as a suppressor gene for depression by targeting nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 11856-11866. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2022.2059937.

- Yan, C.; Li, J.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Tan, L. Long noncoding RNA Gomafu upregulates Foxo1 expression to promote hepatic insulin resistance by sponging miR-139-5p. Cell death & disease 2018, 9, 289. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0321-7.

- Zhang, X.; Ge, L.; Jin, G.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Chen, W.; Chen, L.; Dong, T.; Miyagishima, K.J.; Shen, J.; et al. Cold-induced FOXO1 nuclear transport aids cold survival and tissue storage. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2859. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47095-w.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).