1. Introduction

Amidst the growing challenges posed by climate change, water scarcity has emerged as a critical issue. The need to remove contaminants from wastewater and conserve water resources is increasingly urgent, prompting researchers worldwide to seek innovative solutions [

1]. One promising approach in waste treatment is photocatalytic degradation, which utilizes irradiation to decompose pollutants. This advanced technology has gained significant attention, leading to the development of numerous semiconductor-based photocatalysts [

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is well-established that the efficiency of photocatalytic activity in semiconductors depends on their light absorption characteristics, which are directly linked to their band gap energy, as well as the rate at which photogenerated electron-hole pairs recombine [

6]. To enhance these properties, one effective strategy is to introduce additional energy levels within the semiconductor’s band gap. This modification reduces the band gap, enabling the semiconductor to absorb light at longer wavelengths, thereby improving its photocatalytic efficiency under a wider range of irradiation conditions [

7].

Photocatalytic process is usually carried out in a batch slurry photoreactors operating with nanoparticle suspensions [

8]. Unfortunately, slurry reactors exhibit numerous practical and economical disadvantages. The main obstacle, related to suspended photocatalyst systems, is the separation of the photocatalytic active particles after the treatment. This step could be avoided by supporting those particles catalyst on a suitable carrier, i.e. by forming stable oxide coatings directly on the surfaces of thin metal sheets. In industrial applications solid oxide coatings are more desirable than powders, since immobilized photocatalysts simplify the technology via avoiding the separation step and recirculation. On the other hand, utilization of immobilized oxide coatings reduces the net amount of catalyst surface available to photocatalysis, consequently decreasing the efficiency of the process [

9]. To enhance the efficiency of the process, significant efforts have been directed towards the synthesis of composite photocatalysts, where plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) proved to be an appropriate preparation technique for production of stable oxide coatings [

10].

PEO is an established industrial surface treatment method that can be used to convert the surface of a number of metals (Al, Mg, Ti, Zn and their alloys) to their oxides with possible incorporation of additional elements into obtained coatings through modification of electrolyte composition [

11]. A number of published articles is focused on the incorporation of particles into oxide coatings during the PEO treatment [

12,

13,

14]. Generally, addition of particles to electrolyte used for PEO processing can act as a sealant making obtained oxide coatings denser, thus increasing their wear and corrosion resistance. It has also been shown that incorporation of particles influences the onset of dielectric breakdown, chemical and phase composition of obtained oxide coatings and enhances luminescent and photocatalytic properties [

11].

Recently, a lot of attention has been focused on possible functional additives to PEO electrolytes. Among those additives, so-called nanocontainers (such as zeolites, layered double hydroxides and/or metal organic frameworks), play an important role, because they can be loaded with various components of interest that can be incorporated into PEO coatings [

15,

16,

17]. Zeolites are microporous crystalline materials with a three-dimensional framework composed of pores and channels of regular dimensions. The metal ions in the pore structure can be easily replaced by other cations through ion exchange process [

18]. Regardless the fact that zeolites are mainly used as adsorbents and heterogeneous catalysts, it has been shown that they could enhance the efficiency and selectivity of photocatalysts either by photoactivating the zeolite framework or by encapsulating nano-sized semiconductor oxides [

19,

20,

21]. Previously published papers investigated the incorporation of zeolites into oxide coatings through PEO processing and showed that Ce-exchanged zeolites feature respectable photocatalytic activity which is combined with lower degradation of samples in aggressive environment [

15,

22,

23]. Although the type of zeolite incorporation (inert or reactive) remained unclear in those studies, Al Abri et al. pointed at inert incorporation of Ce-loaded zeolites in so-called soft sparking mode [

24]. In all mentioned works, zeolites are loaded with Ce-ions through simple but time consuming ion exchange process, so in this manuscript we proposed a new method of co-deposition of zeolites with Ce-containing species from electrolyte in order to make less expensive photocatalytic materials. Photocatalytic coatings obtained by PEO processing from electrolyte solution containing both 13 X zeolite and CeO

2 are formed and characterized with respect to their surface morphology, chemical and phase composition, and for their possible application as photocatalysts in photodegradation of organic pollutants.

2. Materials and Methods

Aluminum samples (approximate surface area of 3 cm2) were cut from aluminum 1050 alloy foil and used as the anode. Stainless steel sheet of approx. 20 cm2 was used as the cathode in all experiments. The zeolite used in this work was synthetic FAU-type 13X zeolite (Na87[Al87Si105O384], Si/Al = 1.2) produced by Union Carbide. The average particle size of zeolite powders used in this study is (2.5 ± 0.5) μm, as estimated from SEM micrographs of zeolite powder.

PEO processing was performed in an electrolytic cell containing water solution of 0.01 M sodium tungstate (Na

2WO

4 ∙ 2H

2O), which was used as a supporting electrolyte with additions of 1 g/L 13X zeolite with various amounts of CeO

2 nanoparticles (

Table 1). The electrolyte was prepared using double distilled and deionized water. During the processing electrolyte solution circulated through chamber-reservoir system and the temperature of the electrolyte was kept under 25 °C. The PEO was conducted under a constant current density of 50 mA/cm

2 during 10 minutes using Consort EV 261 (0–600 V, 0-1 A, 300 W) DC power source. After the formation of PEO coatings, samples were rinsed in distilled water and dried in hot air stream. Voltage evolution was recorded using Tektronix TDS 2022 digital storage oscilloscope and a high voltage probe which was connected directly to anode and cathode of the electrolytic cell.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) JEOL JSM-6610 LV equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) Xplore 30 (Oxford Instruments) was used to characterize morphology and chemical composition of formed oxide coatings. Roughness and porosity were estimated from SEM micrographs using ImageJ software (LOCI University of Wisconsin).

Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer with Ni-filtered CuKα radiation source was used for crystal phase identification. Crystallographic data were collected in Bragg-Brentano mode, in 2θ range from 20° to 80° with a scanning rate of 2 °/min. High resolution diffraction patterns are recorded in 2θ range from 22° to 26°, with a scanning rate of 0.05 °/min.

Photoluminescence (PL) spectral measurements were performed on a Horiba Jobin Yvon Fluorolog FL3-22 spectrofluorometer at room temperature, with a 450 W xenon lamp as the excitation light source, in the range from 300 nm to 500 nm.

Photocatalytic activity of obtained coatings on Al substrate was investigated by photodecomposition of methyl orange (MO) at room temperature. Samples (approx. 1.5 cm2 exposed to irradiation) were immersed into 10 mL of 8 mg/L aqueous MO solution and placed on a perforated holder 5 mm above the bottom of the reactor (jacketed 50 ml glass beaker) with a magnetic stirrer underneath. Prior to irradiation, the solution and the catalyst were magnetically stirred in the dark until adsorption-desorption equilibrium was reached (30 min). Afterwards, MO solution was illuminated using a lamp that simulates solar spectrum (Osram Vitalux lamp, 300 W) which was placed 25 cm above the top surface of the solution. Every hour, a fixed amount (1 ml) of the MO solution was removed to measure the absorption at 464 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer Agilent Carry 60. The absorbance was converted to MO concentration in accordance with standard curve showing a linear relationship between the concentration and the absorbance at this wavelength. After each measurement aliquot was returned back to the photocatalytic reactor. Prior to the photocatalytic experiments, MO solution was tested for photolysis in the absence of the photocatalyst and the lack of change in the MO concentration after 6 h of irradiation revealed that the MO was stable under applied conditions and that degradation was only due to the presence of the photocatalyst.

3. Results

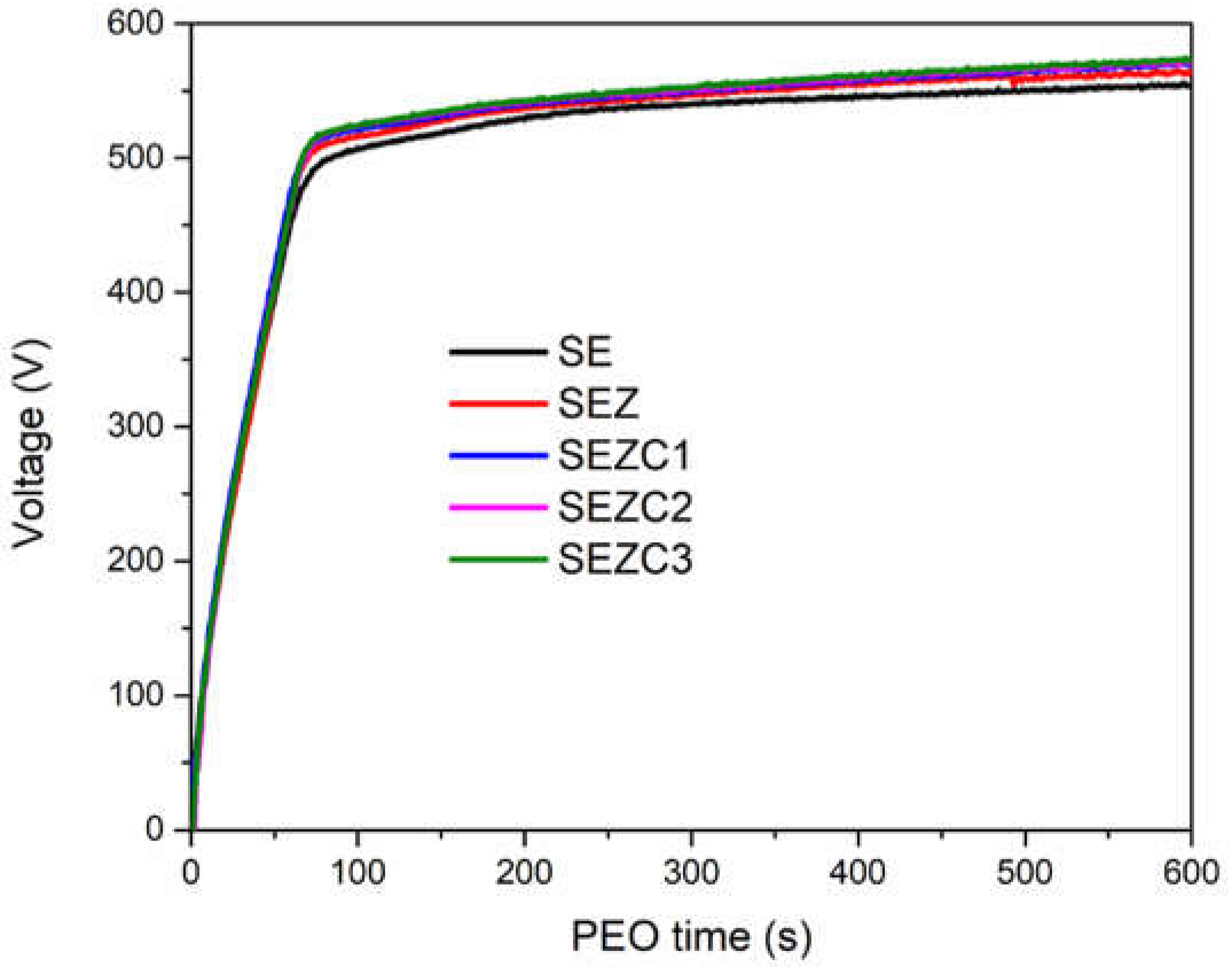

During the formation of PEO coatings voltage evolution was recorded in order to observe whether the coating preparation process follows the typical voltage-time evolution which is one of the characteristics of PEO processing [

25]. Time evolution of anodization voltage during PEO, under current control, in electrolyte solutions used in this work is shown in Figure1. First 90 s of the PEO processing are characterized by linear voltage increase with time. As discussed in many previously published articles, this part of the PEO process is similar to conventional anodizing, and during this time a relatively uniform increase of the barrier layer takes place [

10,

11,

25]. Linear thickening of formed oxide coating ends when dielectric breakdown occurs, which can be observed as deflection from linearity of voltage versus time curve. Further increase of voltage starts a trend of visible microdischarges appearing across the sample’s surface. As can be seen in

Figure 1, addition of zeolite (and CeO

2 powder) did not affect the voltage evolution, although the final PEO voltage did increase with the addition of 13X and CeO

2 to electrolyte solution. Since the breakdown is related to the conductivity (resistivity) of the electrolyte solution, it is expected that the breakdown voltage values do not change significantly as a consequence of similar conductivity values of all electrolytes used in this study (

Table 1). Unchanged voltage-time response suggests that the deposition mechanism remains the same, while a slight voltage increase can be attributed to the addition of pure 13 X zeolite and CeO

2 powder to supporting electrolyte solution.

3.1. Morphology, Chemical and Phase Composition of Formed PEO Coatings

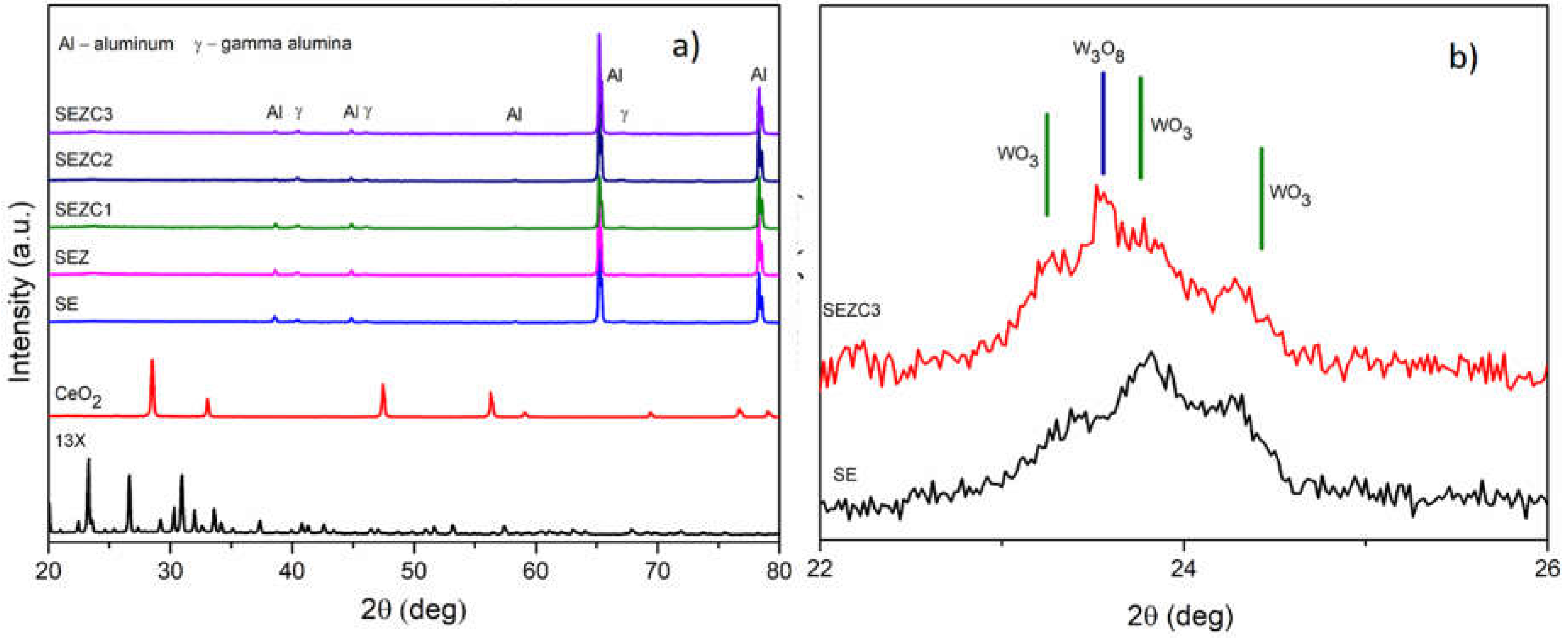

XRD patterns of oxide coatings prepared in all electrolyte solutions after 10 minutes of PEO processing are presented in

Figure 2a, as well as powder XRD patterns of pure 13X zeolite and CeO

2 powder. As one can see from

Figure 2, characteristic reflections of zeolite and CeO

2 powder are not visible in XRD patterns of prepared oxide coatings, most probably as a result of their low concentration or good dispersion. Alongside, previously published articles which were focused on the incorporation either zeolites or CeO

2 into PEO coatings did not observe the reflections corresponding to these additives even up to concentrations of 10 g/L and 4 g/L, respectively [

24,

26]. For all prepared coatings only pronounced XRD maxima originating from Al substrate and low maxima originating from γ-Al

2O

3 (denoted as Al and γ, respectively) are detected. Aside from these maxima, on high resolution scan (

Figure 2b) one can also observe a series of small maxima in the range from 23 to 25 degrees, which may be attributed to the appearance of reflection corresponding to WO

3 and non-stoichiometric phase W

3O

8 [

27].

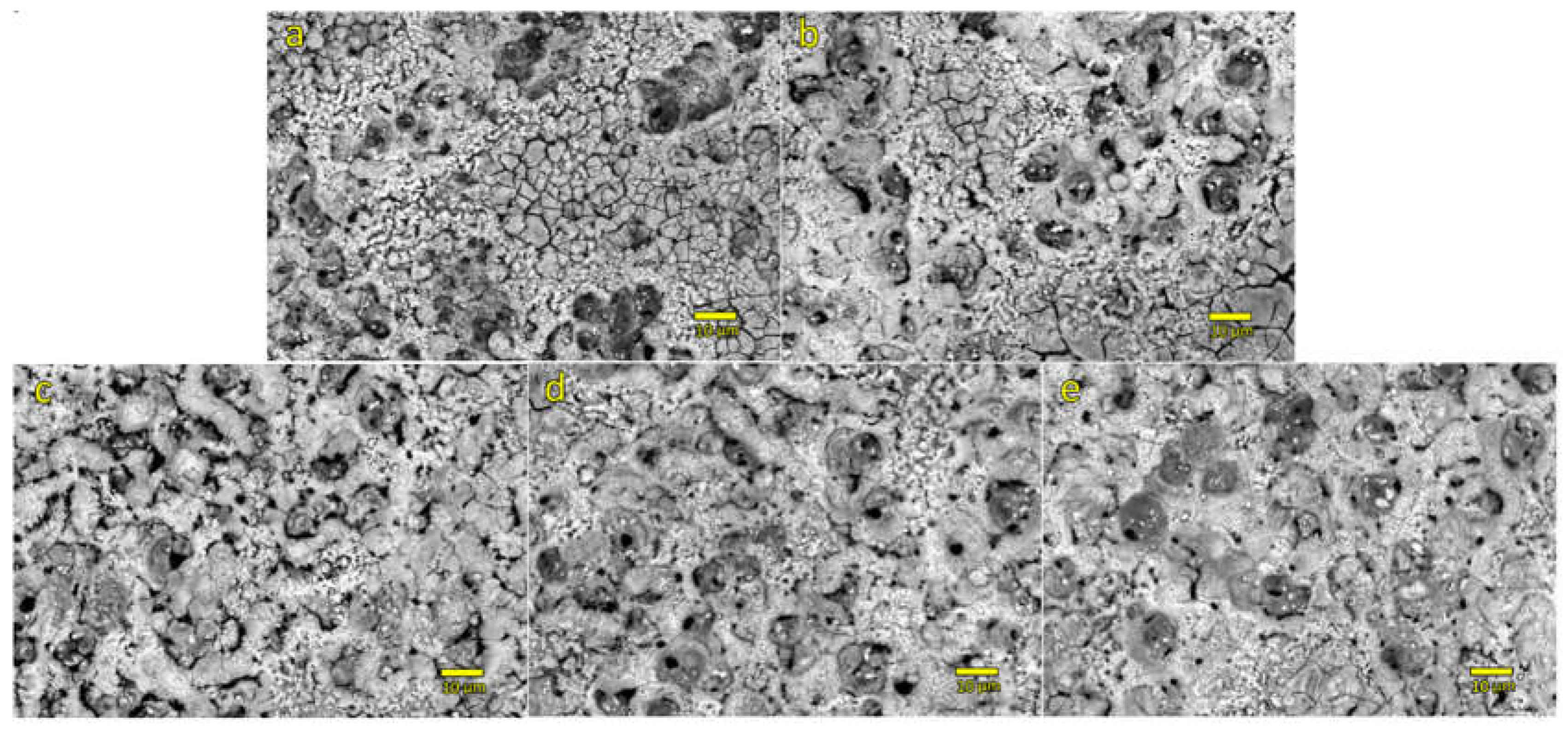

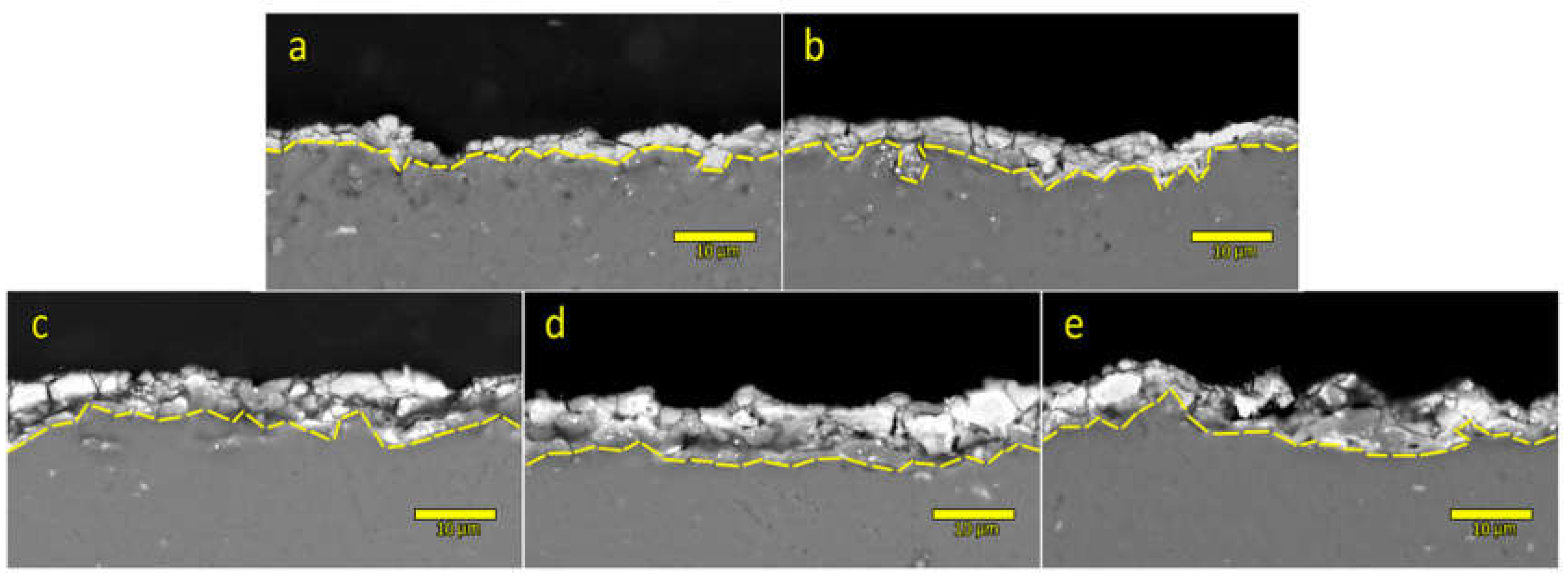

Figure 3 shows top-view SEM micrographs of coatings created during a 10 min PEO process performed in supporting electrolyte and in supporting electrolyte with the addition of 1 g/L of zeolite 13X and various concentrations of CeO

2 powder. Surface morphology of all PEO coatings prepared in this study is similar to each other. Most notable differences between the micrographs presented in

Figure 3 are related to the presence of cracks in coatings with lower concentration of particles in electrolyte solution (

Figure 3a,b) and appearance of nodules on coatings with the higher concentration of particles in electrolyte (

Figure 3c,d,e). Appearance of cracked coatings is inherent to PEO processing, especially when prepared coatings are thin [

11,

28], while the appearance of nodules may be related to increased concentration of particles and inert incorporation of particles on top of the formed coatings [

13]. To further analyze the surfaces of prepared PEO coatings a set of EDS analyses is conducted (

Table 2).

Data presented in

Table 2 are averaged results over three EDS analyses on different areas of prepared coatings. One can see that elements detected in all coatings are either coming from the substrate or from the electrolyte. However, one must be very careful when looking at EDS data because a large experimental error (up to 7 wt%) can be associated with measurement data (when standard deviation of EDS measurements is taken into account). It is interesting to observe that Ce is detected only in the case when 1 g/L of CeO

2 powder is added to electrolyte solution, and even this concentration is very low and it nears the detection limit of the EDS system used in this study. Another interesting result that can be extracted is the presence of Si in the coatings which exclusively originates from the zeolite powder in the solution, suggesting that zeolites are incorporated into prepared PEO coatings.

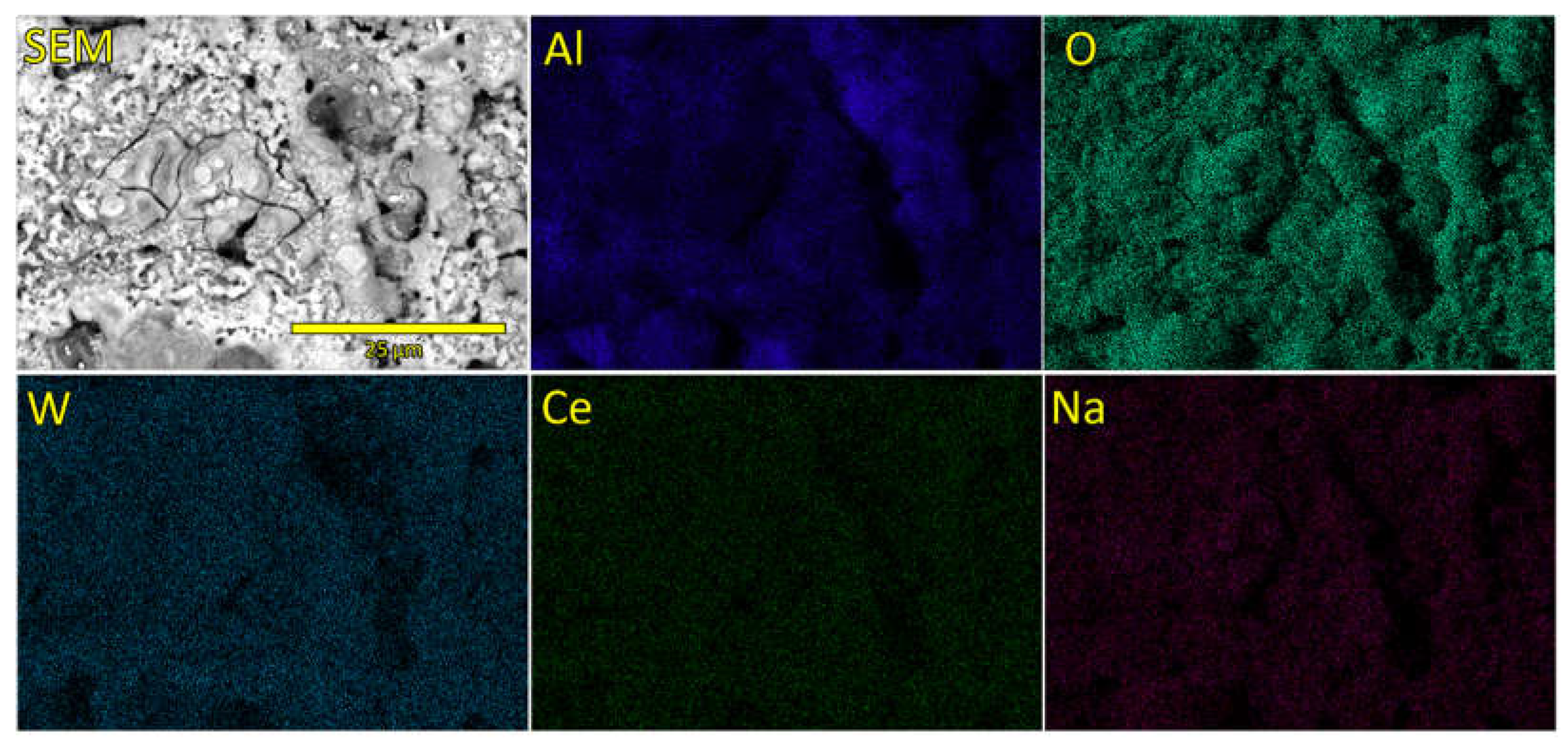

EDS mapping of elements detected on the surface of SEZC3 sample are presented in

Figure 4. While the content and distribution of Al, O and W are well visible and can be related to the growth mechanism of PEO coatings, Na and Ce distributions are barely visible, suggesting that their concentrations are very low (as can be deducted from

Table 2). However, from elemental maps it can be observed that those two elements are well dispersed over the surface, except in the microdischarging channels, suggesting that these are most likely trapped into oxide coatings when molten material which is ejected out of the microdischarge channels and cools down in contact with electrolyte solution [

10].

Top-view SEM images served as a source for extraction of important parameters such as surface roughness and porosity, which undoubtedly influence the photocatalytic properties of formed oxide coatings (

Table 3). Values reported in

Table 3 are average values for five different surface areas obtained using SEM. Evidently, average surface roughness increases with the concentration of particle additions to electrolyte solution, while the porosity decreases. This trend is also observed in our previous study [

27] and it strongly influences the photocatalytic properties of formed coatings, as will be discussed in details later.

Further inspection of formed PEO coatings was done by embedding samples in epoxy resin and cross-sectional polishing in order to extract more information regarding the coating thickness and elemental composition profile. Cross-sectional SEM images are presented in

Figure 5. Gradual thickening of formed coatings is observed starting with the thinnest coatings obtained in sodium tungstate electrolyte solution and ending with the thickest coating which is formed in the electrolyte SEZC3 which was processed in the electrolyte solution with the highest concentration of particles. In order to quantify thickening, precise thickness measurements were performed on five different locations in prepared cross-sections and average values are reported in the last column of

Table 3. It can also be observed that coatings denoted as SE and SEZ are more porous and less dense than the remaining coatings with addition of CeO

2 particles, which is in agreement with literature overview, i.e., with the fact that PEO coatings formed in electrolyte solutions that contain particles are denser and thicker than the coatings which are formed in electrolytes without the addition of particles [

13,

14,

29]. Observed qualitative decrease of porosity with increased concentration of particles in electrolyte in cross-sectional SEM images is also in agreement with quantitative porosity data extracted from top-view SEM images (

Table 3).

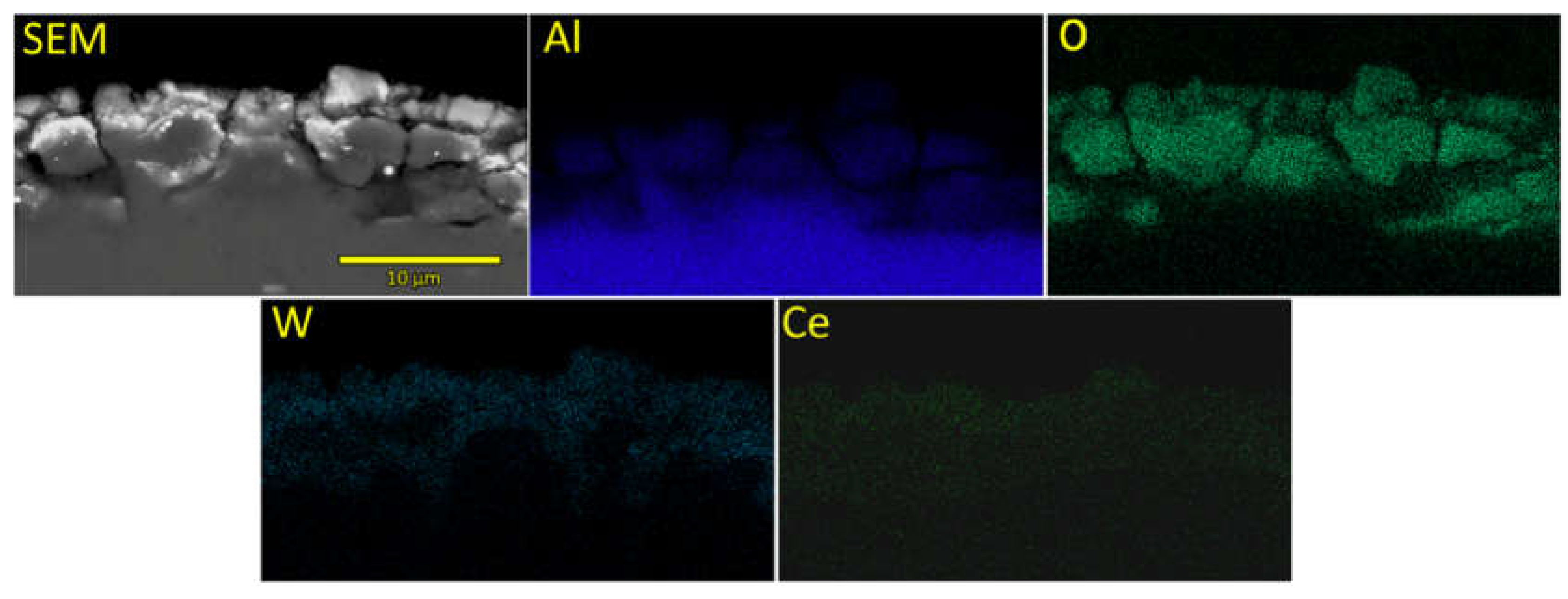

EDS mapping of cross-section corresponding to the sample SEZC3 is presented in

Figure 6. Utilized EDS attachment was not able to quantify the concentration of Ce detected in the cross-section, but Ce EDS map is shown in

Figure 6 so it can be seen that Ce is detected, but its concentration is below the detection limit of the system. All other detected elements, except Al, are evenly distributed through the formed PEO coating, while Al concentration is somewhat higher closer to the substrate.

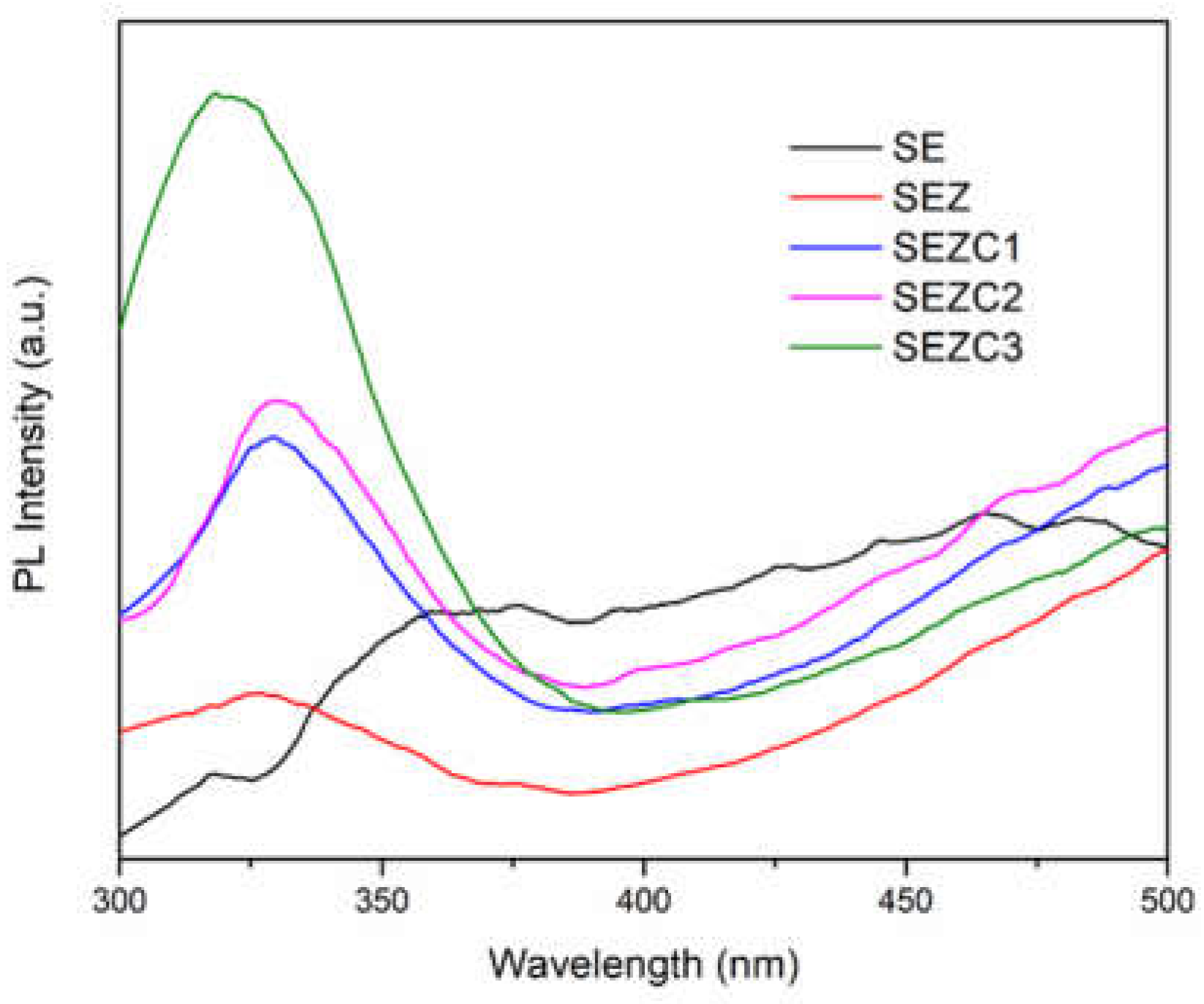

3.2. Photoluminescent and Photocatalytic Properties of Formed PEO Coatings

Previously shown characterizations of PEO coatings formed in sodium tungstate electrolyte solution with the addition of 13 X zeolite and different concentration of CeO

2 were not able to undoubtedly demonstrate the presence of cerium-containing species in the coatings. Since photoluminescence (PL) is a sensitive optical technique capable to identify small concentrations of optically active species on the surface of the samples, a set of emission PL measurements is conducted. Prepared PEO coatings were subjected to irradiation with 285 nm excitation wavelength and emission spectra were measured (

Figure 7). Oxide coating formed by PEO processing in sodium tungstate electrolyte as well as the coating formed with the addition of 13X zeolite to this electrolyte feature rather smooth emission PL spectra without clearly pronounced emission maxima. In contrast to this, all oxide coatings formed in electrolyte that contains CeO

2 powder showed well pronounced emission PL maxima at about 330 nm, which correspond to Ce

3+ emission [

26]. It is worth noting that the initial oxidation state of ceria powder used in this study as an additive to electrolyte solution is Ce

4+, but it is well documented that during the PEO processing Ce

4+ changes its oxidation state to Ce

3+ (for example see

Figure 3 in Ref 26).

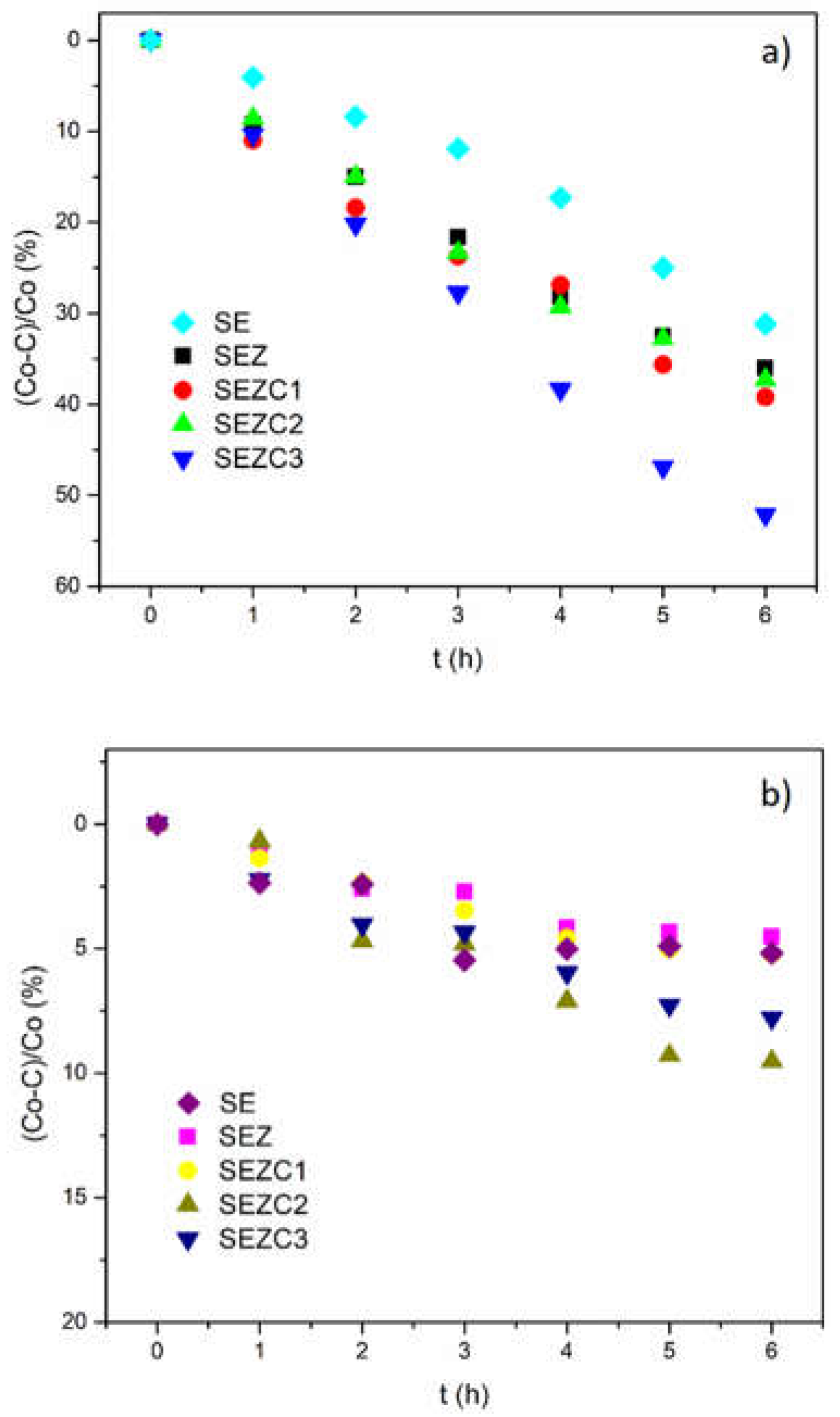

Photocatalytic activity of PEO coatings formed in the supporting electrolyte and with addition of 13X zeolite and CeO

2 powders is shown in

Figure 8a, while

Figure 8b presents the results of MO adsorption in the dark in the presence of prepared photocatalytic oxide coatings. In

Figure 8 C

0 denotes the initial concentration of MO, while C denotes the concentration of MO after time t. It can be observed that photocatalytic activity of PEO coatings prepared in electrolyte solution containing 13X zeolite and CeO2 powder increases with addition of zeolite to supporting electrolyte and it is further enhanced with addition of CeO2 powder. The highest photocatalytic activity of about 50 % is achieved with photocatalytic oxide coating processed in electrolyte solution containing 1 g/L of 13X zeolite and 1g/L of CeO

2 powder. Adsorption of MO in the presence of photocatalytic coatings and absence of light (

Figure 8b) is below 10 % so it can be assumed that results present in

Figure 8a are related only to photocatalytic decomposition of MO in the presence of photocatalytic oxide coatings.

Upon irradiation, the photocatalyst generates electron-hole pairs, initiating key reactions essential for efficient degradation of methyl orange. For optimal degradation, it's crucial to inhibit the recombination of these electron-hole pairs, as recombination would limit the availability of reactive species. In this process, photogenerated electrons migrate from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving behind positively charged holes in the valence band.

These conduction band electrons can readily interact with molecular oxygen (O2), producing the superoxide anion radical (O2•−). This radical species can further react, ultimately leading to the formation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which subsequently decomposes to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH), known for their high reactivity. Meanwhile, the holes in the valence band can react directly with water molecules, generating additional •OH radicals.

The oxidative degradation of azo dyes, such as methyl orange, is predominantly driven by repeated interactions with these highly reactive

•OH radicals, which break down the dye's molecular structure through successive oxidation steps [

30].

4. Discussion

The main goal of presented research was to identify whether it is possible to perform facile co-deposition of zeolite 13X and CeO

2 using PEO processing to form photocatalytically active oxide coatings. In our previous work [

27] Ce-loaded 13X zeolite was incorporated into PEO coatings using continuous DC PEO in sodium tungstate based electrolyte, where cerium containing form of 13X zeolite was obtained using conventional aqueous ion exchange procedure [

18]. This is a common procedure and it has been used by many authors [

22,

24] in order to load various types of zeolites with Ce ions. However, this procedure requires long preparation time and it may be possible to make this process more time efficient by adding CeO

2 directly into the electrolyte solution and to perform a co-deposition of CeO

2 and zeolite. As a source of Ce ions cerium oxide is used in which Ce atoms are in Ce

4+ oxidation state and it is well known that CeO

2 can accept or release O

2 where Ce changes its oxidation state from Ce

3+ to Ce

4+ or from Ce

4+ to Ce

3+ following the equation [

31]:

In the case of PEO processed oxide coatings, a large number of oxygen vacancy defects is present in formed coatings and Ce oxidation state is readily reduced to Ce

3+ [

26,

32]. Addition of CeO

2 to electrolyte was designed so it covers the concentration of Ce in Ce-loaded 13X zeolite (25.5±1.3 wt%) achieved in our previous work [

15] and obtained results showed that even with concentration as high as 1 g/L of CeO

2 in electrolyte solution, CeO

2 diffraction maxima were not present in XRD patterns, while the concentration of Ce on the surfaces of prepared PEO coatings was close to (or below) the limit of detection of EDS system. Furthermore, as in the case of incorporation of Ce-loaded zeolites, morphological characteristics followed similar trends, i.e., surface roughness increased, while porosity decreased with increased incorporation species coming from the electrolyte.

Obtained emission PL spectra feature luminescence maxima for all coatings containing Ce very close to the position which is characteristic for Ce

3+ ion luminescence, suggesting that due to a large number of oxygen vacancy defects present in PEO processed coatings Ce

4+ reduces to Ce

3+, showing once again that PEO processing may be also used for Ce

4+/Ce

3+ redox-controlled luminescence [

33].

Photodecomposition of MO under simulated sunlight irradiation in the presence of prepared oxide coatings (

Figure 8a) clearly demonstrates that addition of zeolite 13X to the sodium tungstate electrolyte solution increases photoactivity. Subsequent addition of CeO

2 in different concentrations also favors this increase, which can be related to changes in surface morphology of the samples. Namely, increased surface roughness is closely related to an increase of surface area available for photodecomposition of MO, which is favorable for photocatalytic activity. On the other hand, porosity decreases with increasing addition of particles to electrolyte solution, suggesting that tortuosity of microdischarge channels, i.e. pores, is rather high and prevents light as an immaterial agent to enter deep into microdischarge channels where it can trigger the photodecomposition of MO.

Figure 8a also demonstrates the contribution of increased CeO

2 concentration in electrolyte to the photocatalytic activity of formed coatings: higher concentration of CeO

2 in electrolyte solution results in higher photoactivity. This may lead to a speculation that Ce

3+ ions incorporated into Al

2O

3 matrix which emit strong PL in the near ultraviolet region (

Figure 7) act as secondary source of irradiation thus increasing irradiation intensity and enhancing photodecomposition of MO. Since the lamp that was used for irradiation covers UV part of the solar spectrum it can be expected that it serves as an excitation source for Ce

3+ ions which emit radiation that can participate in photocatalytic reactions [

34].

5. Conclusions

Oxide coatings with co-deposited 13X zeolite and CeO2 are formed using PEO processing for 10 min in 0.01 M Na2WO4 water based solutions. The main goal of this study was to investigate whether it is possible to use simple co-deposition of above mentioned species to obtain photocatalysts that are comparable to those made with the incorporation of Ce-exchanged zeolite 13X in the same electrolyte. Based on experimental data, the following conclusions can be drawn:

It is possible to form photoactive PEO coatings via co-deposition of 13X zeolite (1g/L) and varying concentration of CeO2 (0.25 g/L, 0.5 g/L, and 1g/L). The morphology of formed oxide coatings is very similar to coatings with Ce-loaded zeolites under the same conditions. Roughness of obtained coatings increases with the addition of CeO2 to solution, while their porosity decreases.

Chemical composition of formed oxide coatings reveals the presence of species originating both from the substrate and from the electrolyte solution. Although Ce can be detected in oxide coatings, its concentration is near or below the detection limit of used EDS system.

Semi-quantitative detection of Ce is performed utilizing photoluminescence as a surface sensitive technique. The concentration of Ce (observed as intensity of emission PL peak corresponding to Ce3+ ions) increases with increased addition of CeO2 to electrolyte solution.

Photodecomposition of MO registered for SEZC3 sample (highest photocatalytic activity observed in this study) is very close to that observed for oxide coatings with incorporated Ce-loaded 13X zeolite processed for 10 minutes under the same PEO conditions. However, the sample SEZC1, which is very close to chemical composition of PEO coatings with incorporated Ce-loaded 13X zeolite has photocatalytic activity which is about 1.5 times lower.

Although co-deposition of 13X zeolite and CeO2 is a viable method for producing photocatalytic coatings, it requires higher concentration of CeO2 in electrolyte to achieve similar values of photocatalytic decomposition as in the case of PEO incorporation of Ce-loaded zeolites.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.V. and K.M.; methodology, K.M. and N.T.; investigation, K.M., N.T., S.S..; data curation, K.M., N.T., S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V. and Lj.D.V.; writing—review and editing, R.V., Lj.D.V, and K.M.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, R.V. and Lj.D.V.; project administration, R.V.; funding acquisition, R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, grant number 7309 ZEOCOAT, by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 823942 (FUNCOAT), and by Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (451-03-65/2024-03/200162 and 451-03-65/2024-03/200146).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relation-ships that could have appeared to influence the results reported in this paper.

References

- Silva, J.A. Wastewater treatment and reuse for sustainable water resources management: A systematic literature review, Sustainability 2023, 15(14), 10940. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, Z.; Li, L.; Burt, R.; Zhao, X.S. Uptake and degradation of Orange 2 by zinc aluminum layered double oxides, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 469, 224–230. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wen, W.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.M., Photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanorods, nanowires and nanoflowers filled with TiO2 nanoparticles, Thin Solid Films 2018, 648 103-107. [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.S.; Lee, J.W.; Chong, W.C.; Pang Y.L.; Sim, L.C. An overview of photocatalytic degradation: photocatalysts, mechanisms, and development of photocatalytic membrane, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2522–2565. [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Anastasescu, C.; State, R.-N.; Vasile, A.; Papa, F.; Balint, I. Photocatalytic degradation of organic and inorganic pollutants to harmless end products: Assessment of practical application potential for water and air cleaning, Catalysts 2023, 13(2), 380. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.M.; Reddy, E.P.; Mehdi, S., Phase transformation study of titania in V2O5TiO2 and MoO3TiO2 catalysts by X-ray diffraction analysis, Mat. Chem. Phys., 1994, 36 (3-4), 276-281.

- Seyed Dorraji, M.S.; Rasoulifard, M.H.; Daneshvar, H.; Vafa, A.; Amani-Ghadim, A.R. ZnS/ZnNiAl-LDH/GO nanocomposite as a visible-light photocatalyst: preparation, characterization and modeling, J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 12152–12162.

- Lee, D-E.; Kim, M-K.; Danish, M.; Jo, W-K. State-of-the-art review on photocatalysis for efficient wastewater treatment: Attractive approach in photocatalyst design and parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation, Catal. Commun. 2023, 183, 106764. [CrossRef]

- Pansila, P.P.; Witit-Anun, N.; Chaiyakun, S. Effect of oxygen partial pressure on the morphological properties and the photocatalytic activities of titania thin films on unheated substrates by sputtering deposition method, Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 770, 18-21. [CrossRef]

- Yerokhin, A.L.; Nie, X.; Matthews, A.; Dowey, S.J. Plasma electrolysis for surface engineering, Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 122. [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Fatimah, S.; Nashrah, N.; Ko, Y.G. Recent progress in surface modification of metals coated by plasma electrolytic oxidation: principle, structure, and performance, Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100735. [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R.; Radić, N.; Tadić, N.; Stefanov, P.; Grbić, B. The formation of tungsten doped Al2O3/ZnO coatings on aluminum by plasma electrolytic oxidation and their application in photocatalysis, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 377, 37-43.

- Lu, X.; Mohedano, M.; Blawert, C.; Matykina, E.; Arrabal, R.; Kainer, K.U.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings with particle additions- A review, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307 1165-1182. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Blawert, C; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Kainer, K.U. Insights into plasma electrolytic oxidation treatment with particle addition, Corros. Sci. 2015, 101, 201-207.

- Mojsilović, K.; Božović, N.; Stojanović, S.; Damjanović-Vasilić, Lj.; Serdechnova, M.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R. Zeolite-containing photocatalysts immobilized on aluminum support by plasma electrolytic oxidation, Surf. Interfaces 2021 26 101307. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Serdechnova, M.; Blawert, C.; Wang, H.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Chen, F. Double-ligand strategy to construct an inhibitor-loaded Zn-MOF and its corrosion protection ability for aluminum alloy 2A12, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 51685-51694. [CrossRef]

- Wei, K; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Kong, W.; Zhang, Y. Duplex coating combining vanadate-intercalated layered double hydroxide and Ce-doped sol-gel layers on aluminum alloy for active corrosion protection, Materials 2023, 16(2), 775.

- Dondur, V.; Dimitrijević, R.; Kremenović, A.; Damjanović, Lj.; Kićanović, M.; Cheong, H.M.; Macura, S. Phase transformations of hexacelsians doped with Li, Na and Ca, Mater. Sci. Forum 2005 494, 107-112.

- Galvão, T.L.P.; Bouali, A.C.; Serdechnova, M.; Yasakau, K.A.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Tedim, J. Chapter 16 - Anticorrosion thin film smart coatings for aluminum alloys in Advances in Smart Coatings and Thin Films for Future Industrial and Biomedical Engineering Applications; Editor(s): Abdel Salam Hamdy Makhlouf, Nedal Y. Abu-Thabit, Elsevier, 2020, Pages 429-454.

- Alvarez-Aguiñaga, E.A.; Elizade-Gonzalez, M.; Sabinas-Hernandez, S.A. Unpredicted photocatalytic activity of clinoptilolite-mordenite natural zeolite, RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 39251-39260. [CrossRef]

- Latha, P.; Karuthapandian, S.; Novel, facile and swift technique for synthesis of CeO2 nanocubes immobilized on zeolite for removal of CR and MO dye, J. Clust. Sci. 2017, 28, 3265-3280. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lu, X.; Serdechnova, M.; Wang, C.; Lamaka, S.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Wang, F. Formation of self-healing PEO coatings on AM50 Mg by in-situ incorporation of zeolite micro-container, Corros. Sci. 2022 209, 110785. [CrossRef]

- Mojsilović, K.; Božović , N.; Stojanović, S.; Damjanović-Vasilić, LJ.; Serdechnova, M.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, ML.; Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R. Oxide coatings with immobilized Ce-ZSM5 as visible light photocatalysts, J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2022, 87(9), 1035–1048. [CrossRef]

- Al Abri, S.; Rogov, A.; Aliasghari, S.; Bendo, A.; Matthews, A.; Yerokhin, A.; Mingo, B. In-situ incorporation of Ce-zeolite during soft sparking plasma electrolytic oxidation, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 2365-2376. [CrossRef]

- Clyne, T.W.; Troughton, S.C.; A review of recent work on discharge characteristics during plasma electrolytic oxidation of various metals, Int. Mater. Rev. 2019, 64(3),127-162. [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R. Photoluminescence of Ce3+ and Ce3+/Tb3+ ions in Al2O3 host formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation, J. Lumin. 2018, 203, 576-581.

- Mojsilović, K.; Lačnjevac, U.; Stojanović, S.; Damjanović-Vasilić, LJ.; Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R. Formation and properties of oxide coatings with immobilized zeolites obtained by plasma electrolytic oxidation of aluminum, Metals 2021, 11, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Mojsilović, K.; Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R. The Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation of Aluminum Using Microsecond-Range DC Pulsing. Metals 2023, 13, 1931. [CrossRef]

- Arrabal, R.; Mohedano, M.; Matykina, E.; Pardo, A.; Mingo, B.; Merino, M.C. Characterization and wear beahviour of PEO coatings on 6082-T6 aluminium alloy with incorporated α-Al2O3 particles, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 269, 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Latha, P.; Prakash, K.; Karuthapandian, S. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of CeO2/alumina nanocomposite: Synthesized via facile mixing-calcination method for dye degradation, Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 2903-2913. [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, M.; Maiyalagan, T. Synergistically enhanced electrocatalytic activity of cerium oxide/manganese tungstate composite for oxygen reduction reaction, J. Mater. Sci. MMojsilovićater. Electron. 2022, 33 9538–9548. [CrossRef]

- Manojkumar, P.; Lokeshkumar E.; Premchand, C.; Saikiran, A.; Rama Krishna, L.; Rameshbabu, N. Facile preparation of immobilized visible light active W-TiO2/rGO composite photocatalyst by plasma electrolytic oxidation process, Physica B Condens. Matter 2022 632, 413680. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Byeon, S.-H. Ce4+/Ce3+ redox-controlled luminescence ‘on/off’ switching of highly oriented Ce(OH)2Cl and Tb-doped Ce(OH)2 Cl films, J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Radić, N.; Tadić, N.; Vasilić, R.; Grbić, B. Enhanced ultraviolet light driven photocatalytic activity of ZnO particles incorporated by plasma electrolytic oxidation into Al2O3 coatings co-doped with Ce, Opt. Mater. 2020, 101, 109768. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).