Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

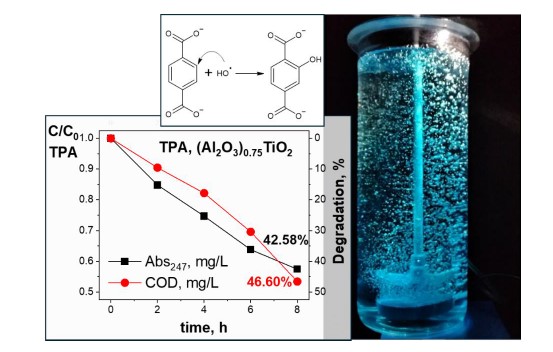

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

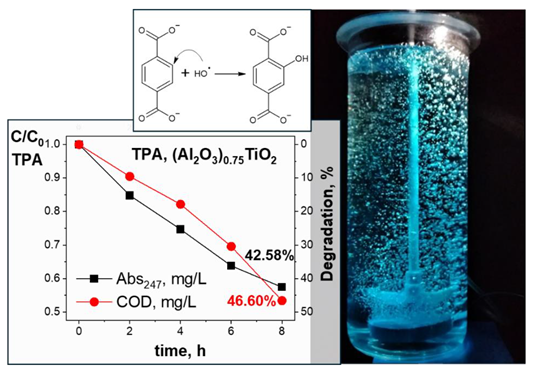

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coating Preparation by the Sol-Gel Route

2.2. Structural Characterization Measurements

2.3. Photocatalytic Degradation

3. Results and Discussion

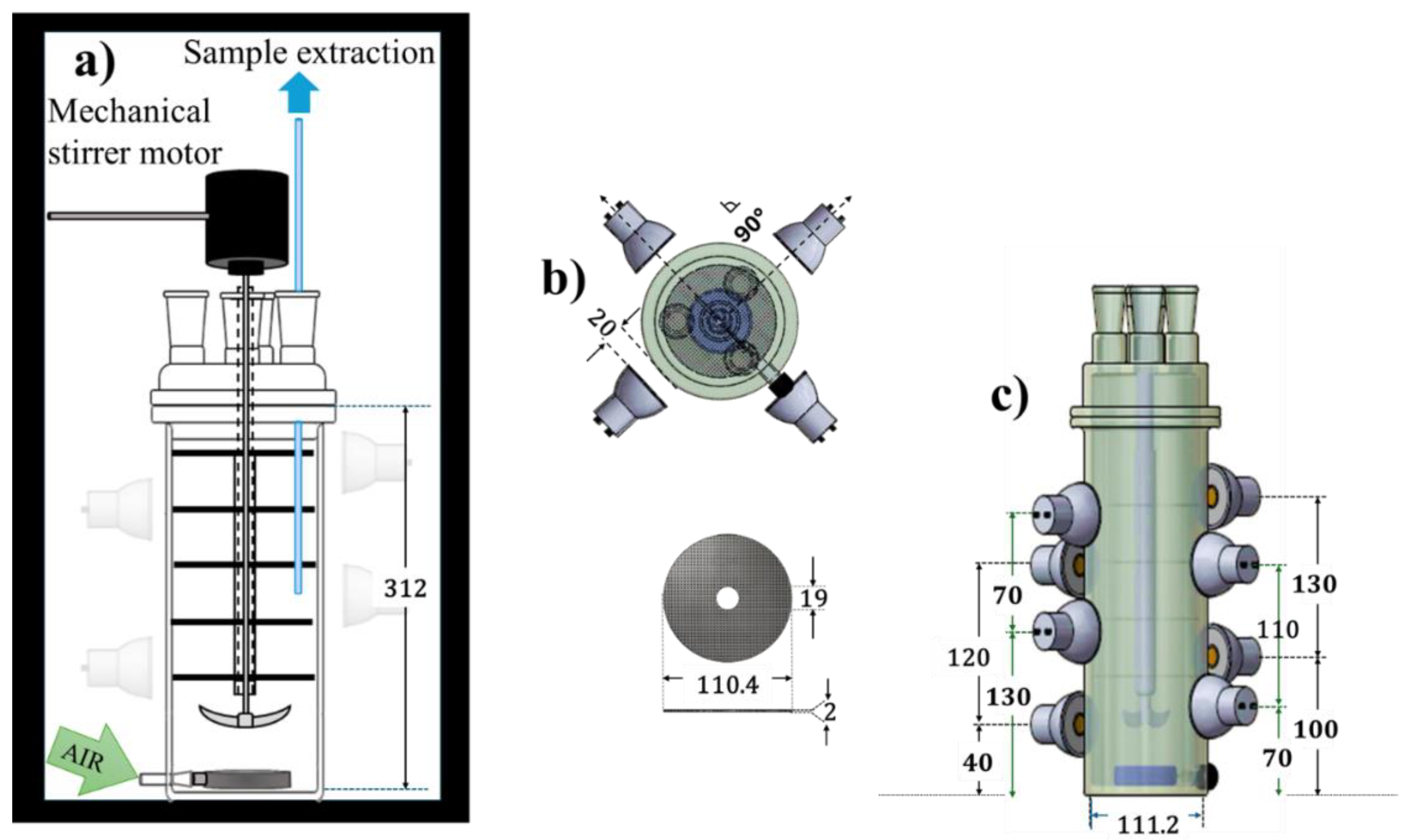

3.1. (Al2O3)0.75TiO2 Coating Characterization

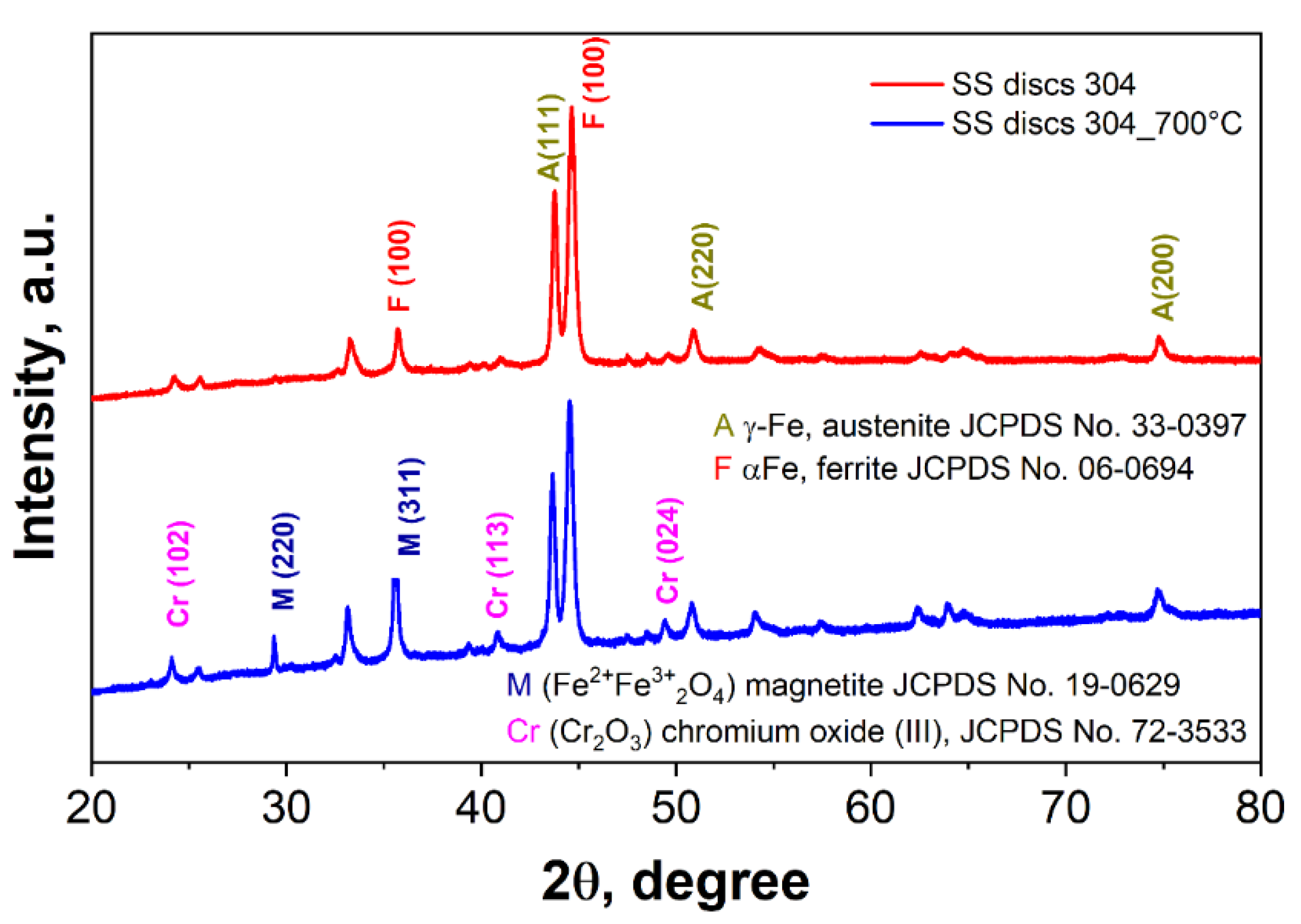

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction

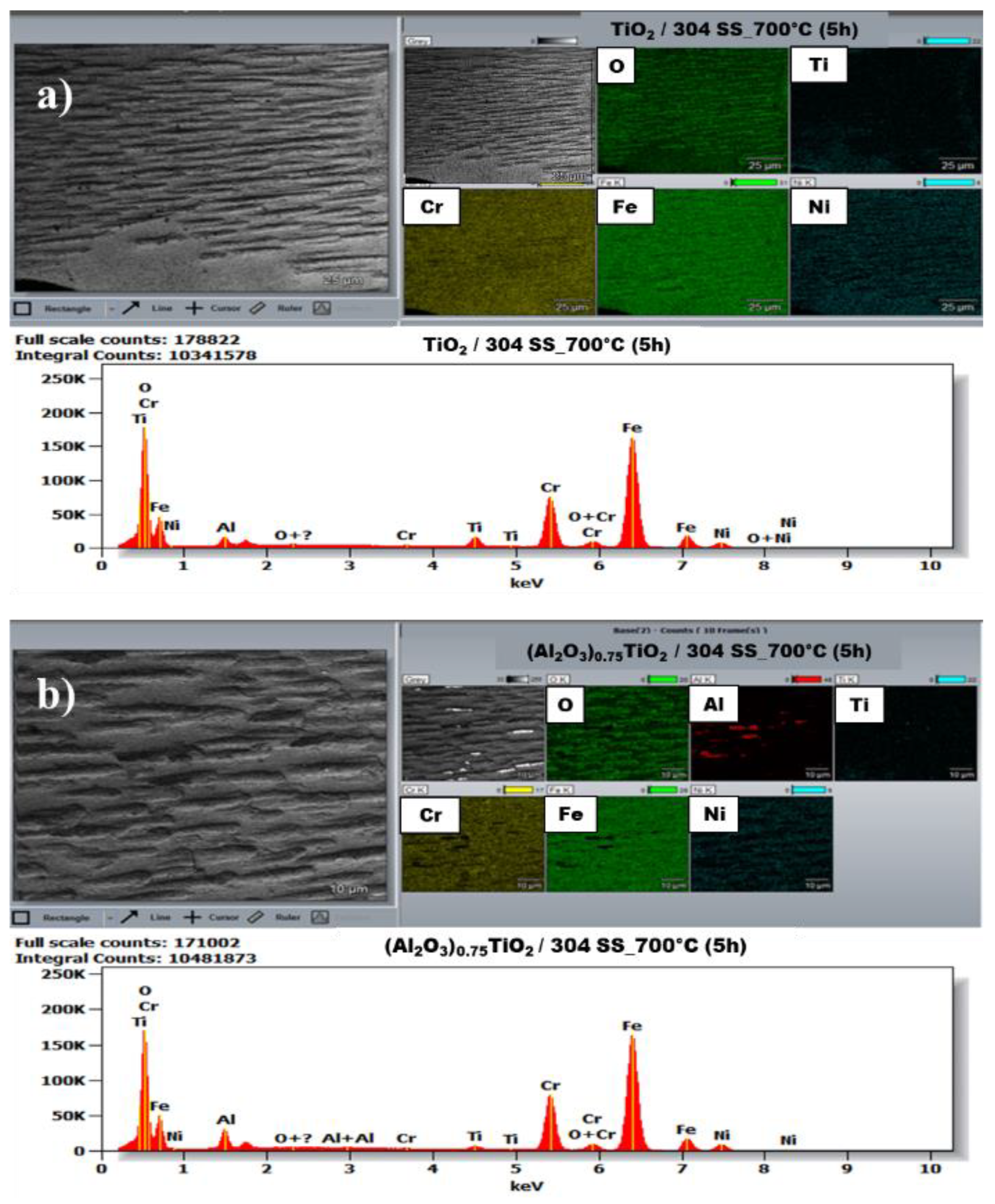

3.1.2. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy. Elemental Analysis

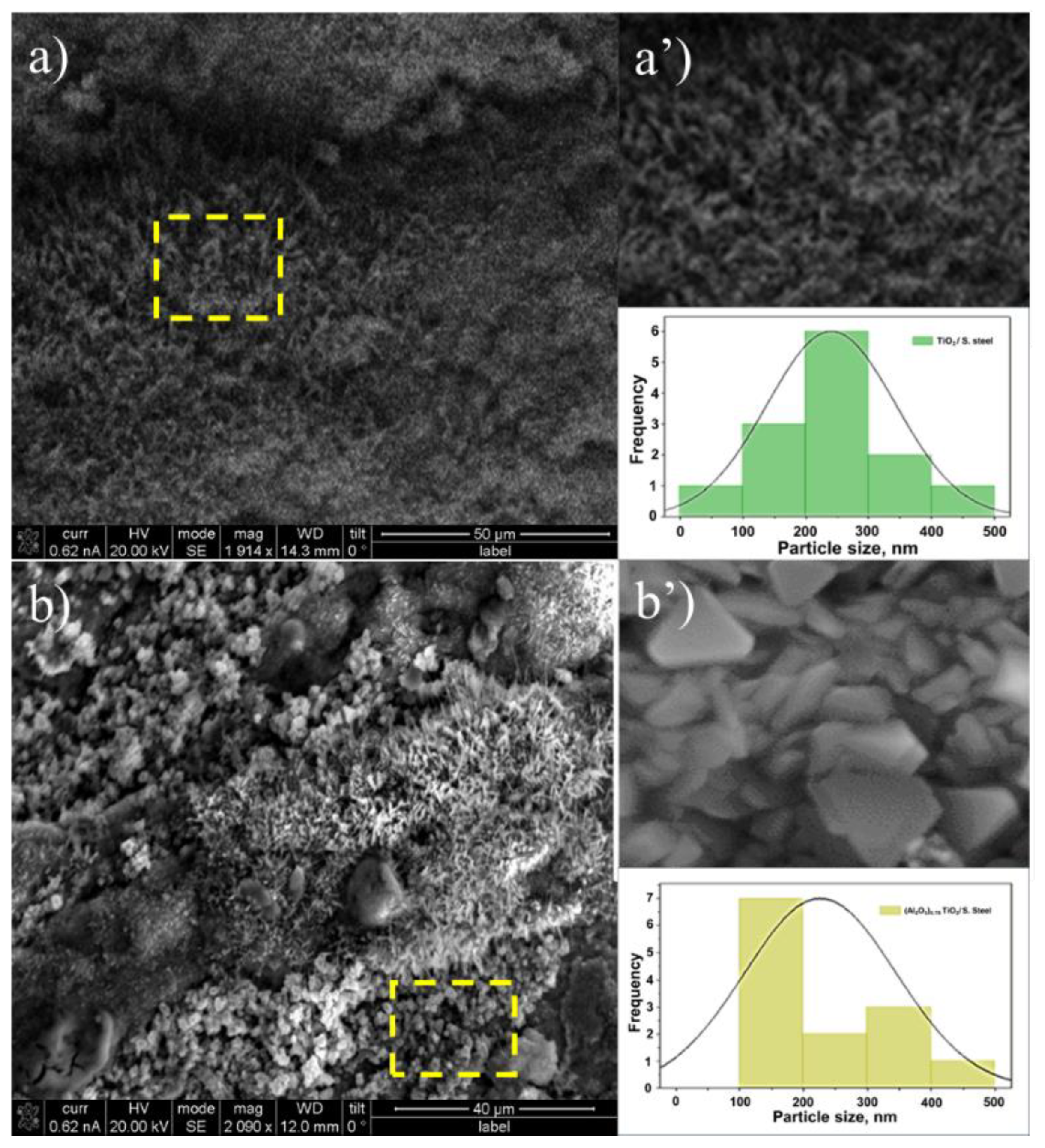

3.1.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy. Morphology and Particle Size

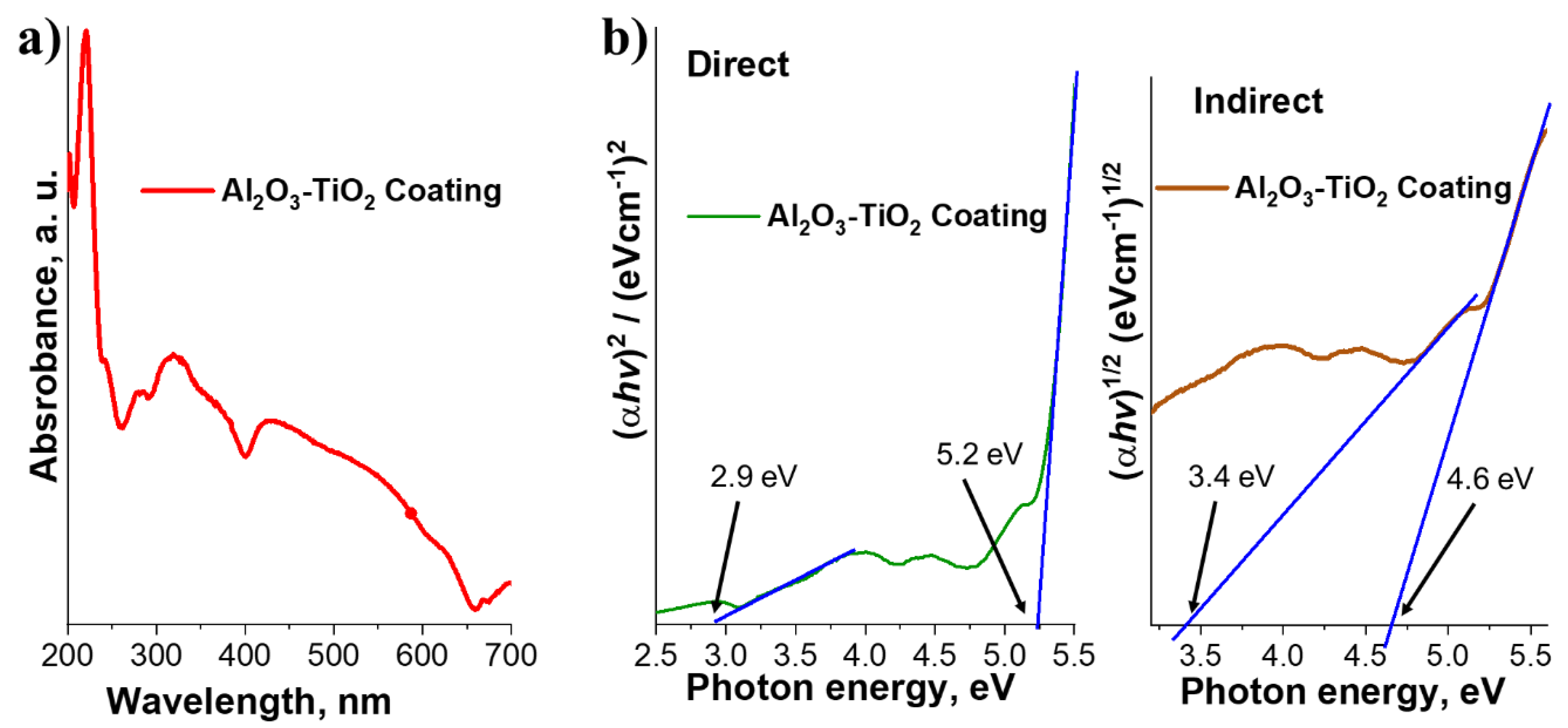

3.1.4. UV-Visible Spectroscopy. Optical Properties and Determination of the Forbidden Band Energy

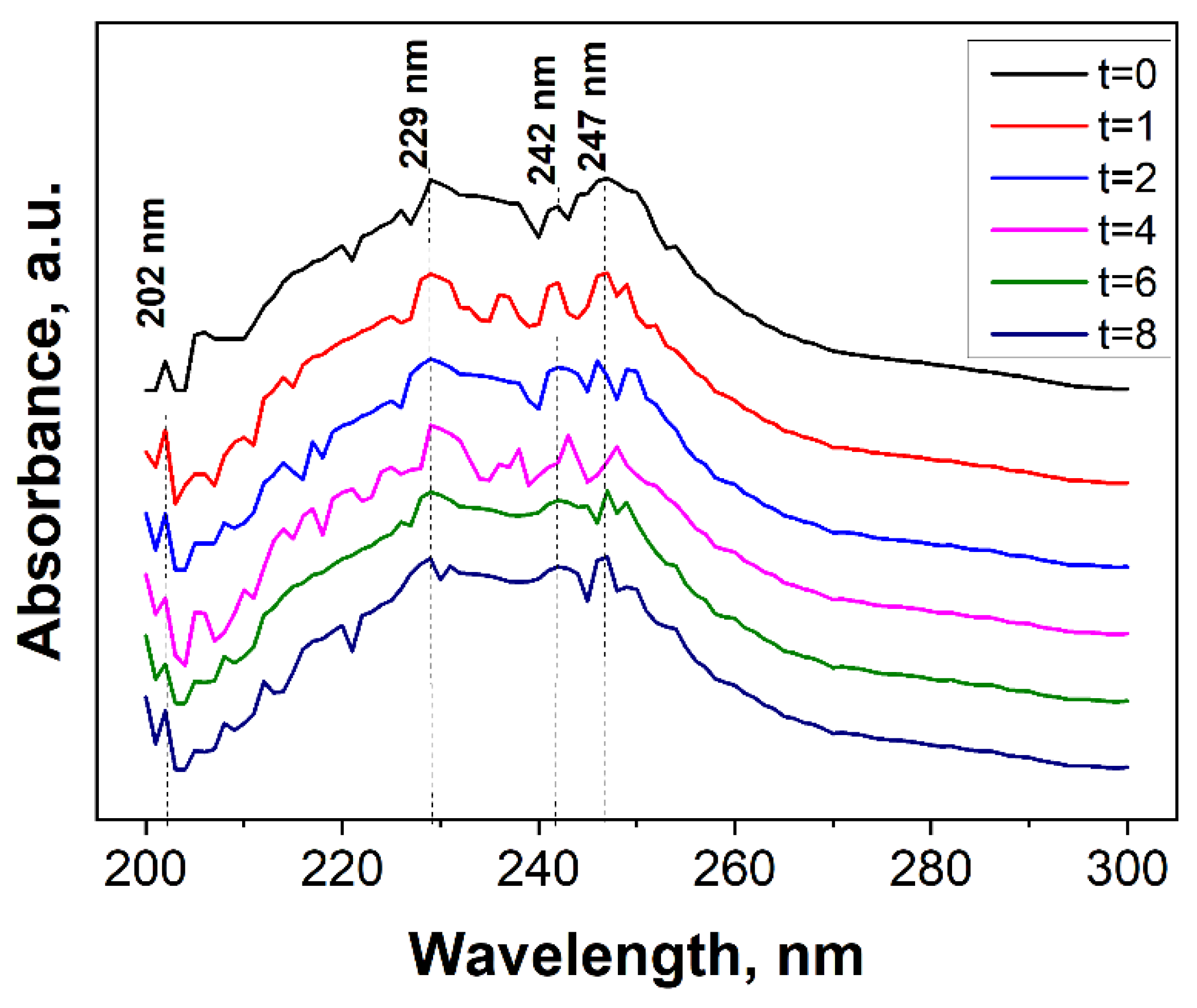

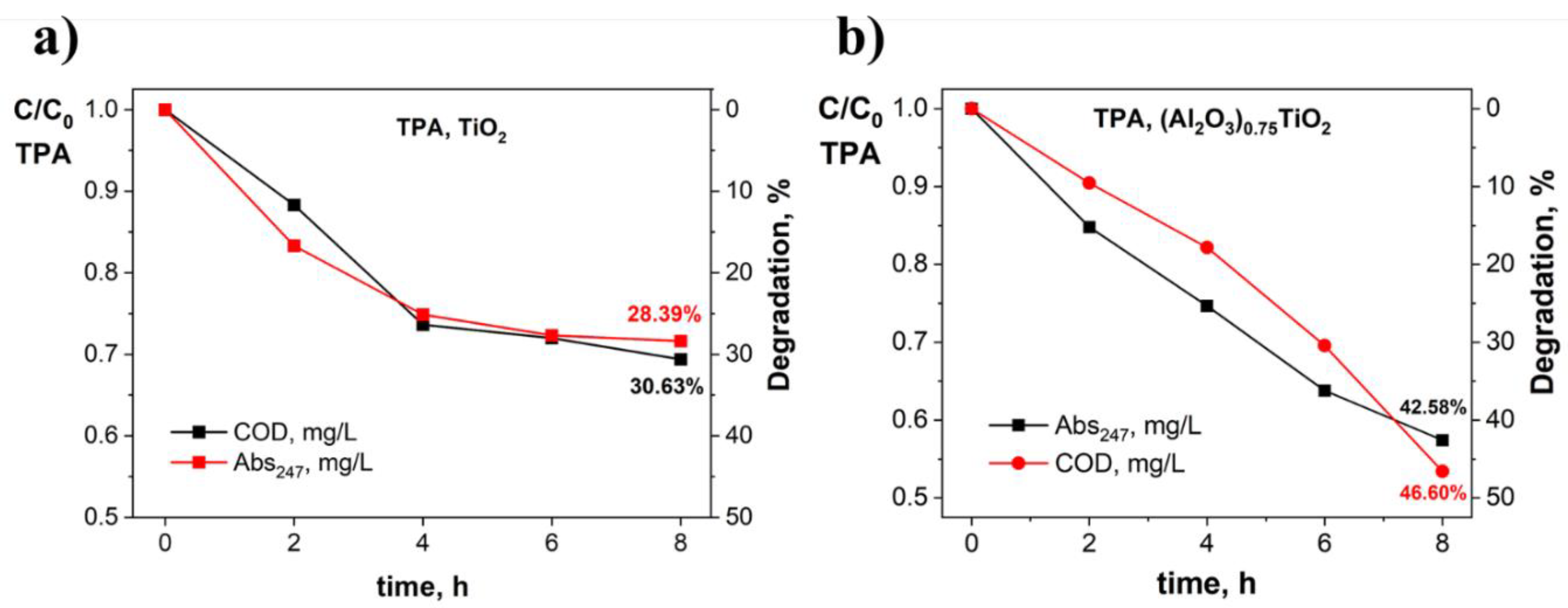

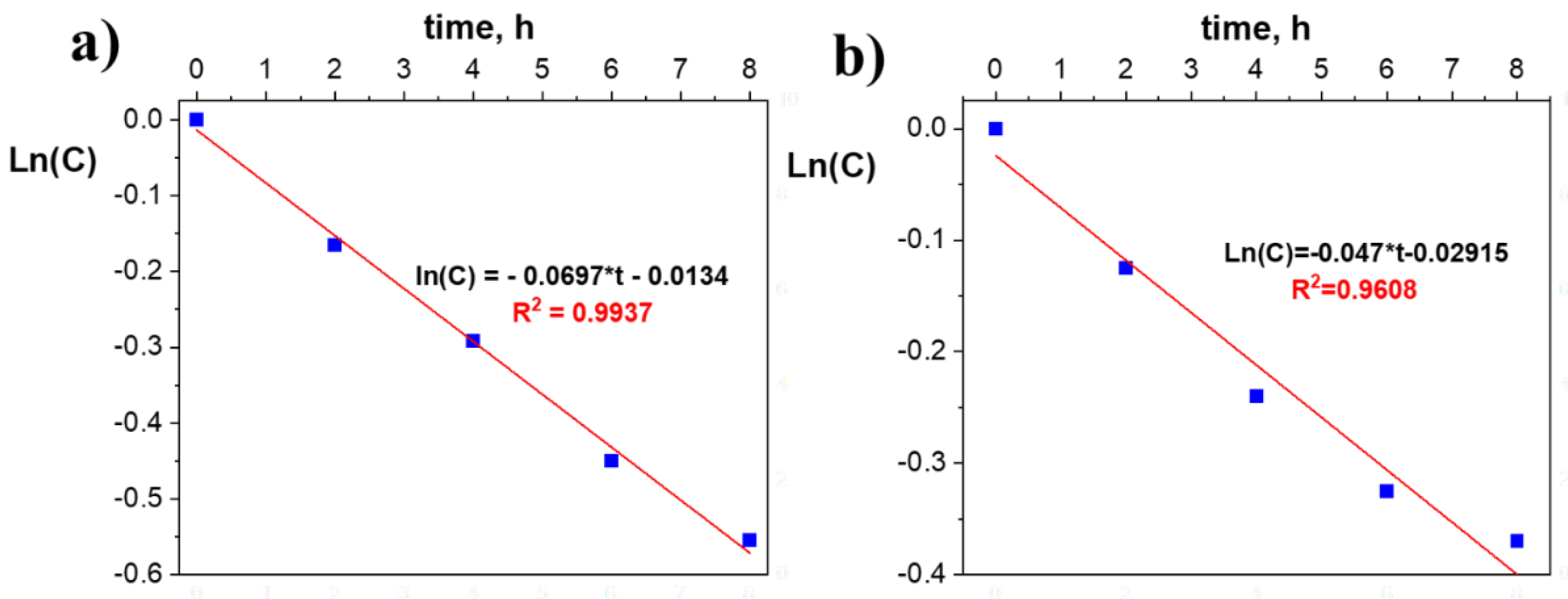

3.2. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Efficiency in the Degradation of Terephthalic Acid by the Immobilized (Al2O3)0.75TiO2 System

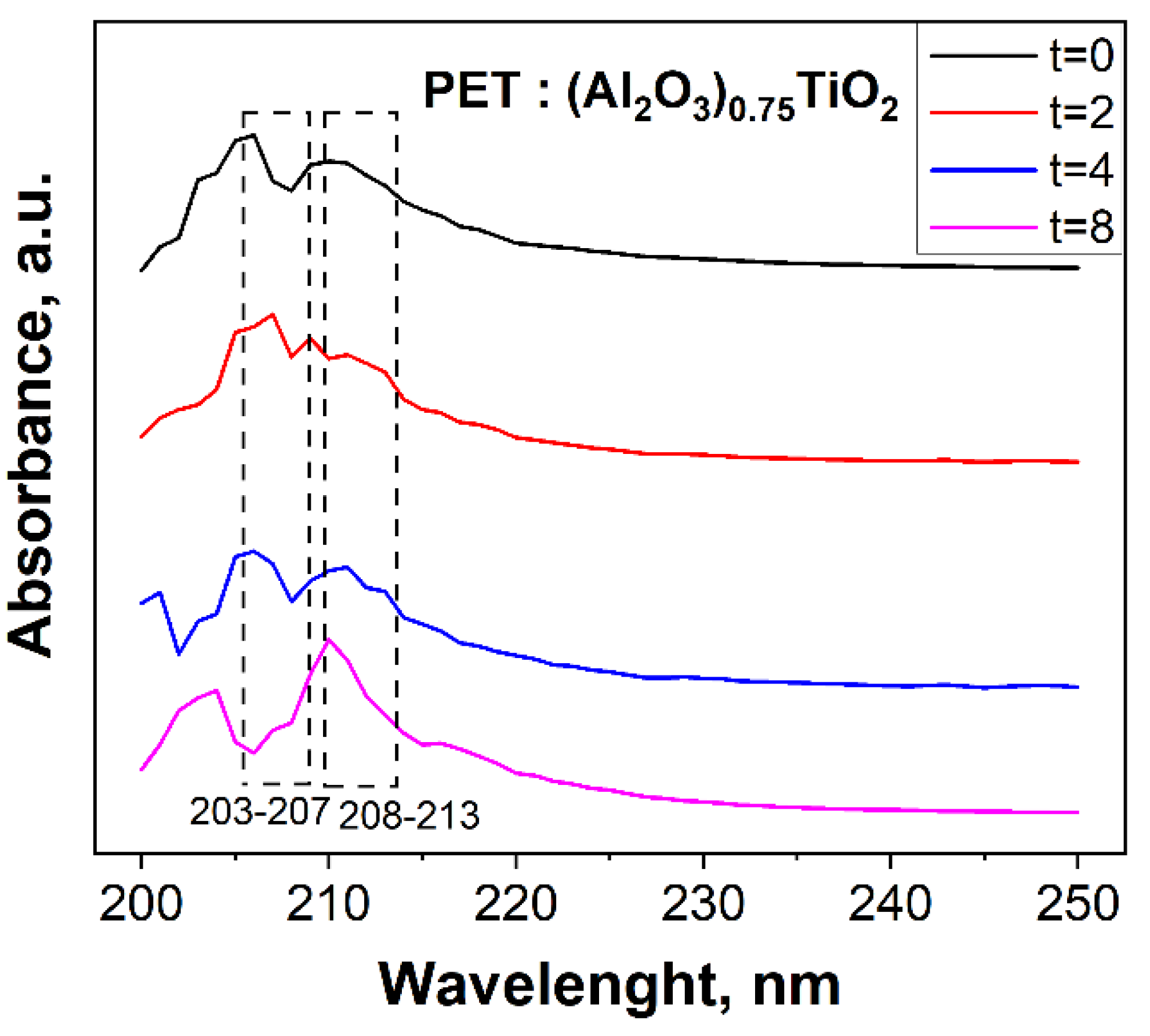

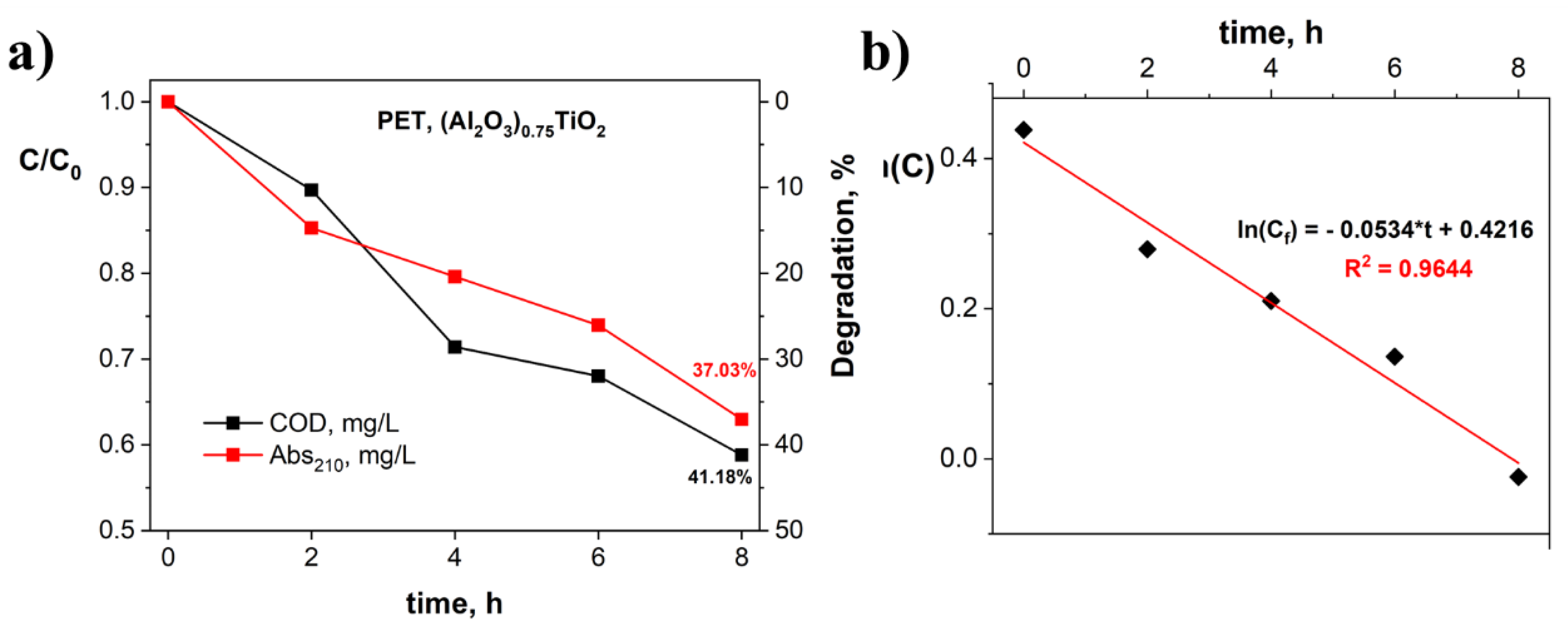

3.3. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Efficiency of PET Degradation by the Immobilized (Al2O3)0.75TiO2 System

4. Conclusions

References

- Agostini, I., Ciuffi, B., Gallorini, R., Rizzo, A. M., Chiaramonti, D., & Rosi, L. (2022). Recovery of Terephthalic Acid from Densified Post-consumer Plastic Mix by HTL Process. In Molecules (Vol. 27, Issue 20). [CrossRef]

- Al Miad, A., Saikat, S. P., Alam, M. K., Sahadat Hossain, M., Bahadur, N. M., & Ahmed, S. (2024). Metal oxide-based photocatalysts for the efficient degradation of organic pollutants for a sustainable environment: a review. Nanoscale Advances, 6(19), 4781–4803. [CrossRef]

- Ali, I., Suhail, M., Alothman, Z. A., & Alwarthan, A. (2018). Recent advances in syntheses, properties and applications of TiO2 nanostructures. RSC Advances, 8(53), 30125–30147. [CrossRef]

- Askeland, D. R., & Wright, W. J. (1998). Ciencia e ingeniería de los materiales (Vol. 3). International Thomson Editores México.

- Barajas-Ledesma, E., García-Benjume, M. L., Espitia-Cabrera, I., Ortiz-Gutiérrez, M., Espinoza-Beltrán, F. J., Mostaghimi, J., & Contreras-García, M. E. (2010). Determination of the band gap of TiO2–Al2O3 films as a function of processing parameters. Materials Science and Engineering: B, 174(1), 71–73. [CrossRef]

- Billings, A., Jones, K. C., Pereira, M. G., & Spurgeon, D. J. (2021). Plasticisers in the terrestrial environment: sources, occurrence and fate. Environmental Chemistry, 18(3), 111–130. [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C. J., & Scherer, G. W. (2013). Sol-gel science: the physics and chemistry of sol-gel processing. Academic press.

- Byrne, C., Subramanian, G., & Pillai, S. C. (2018). Recent advances in photocatalysis for environmental applications. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 6(3), 3531–3555. [CrossRef]

- Camacho-González, M. A., Lijanova, I. V, Reyes-Miranda, J., Sarmiento-Bustos, E., Quezada-Cruz, M., Vera-Serna, P., Barrón-Meza, M. Á., & Garrido-Hernández, A. (2023). High Photocatalytic Efficiency of Al2O3-TiO2 Coatings on 304 Stainless Steel for Methylene Blue and Wastewater Degradation. In Catalysts (Vol. 13, Issue 10). [CrossRef]

- Chang, B. V, Yang, C. M., Cheng, C. H., & Yuan, S. Y. (2004). Biodegradation of phthalate esters by two bacteria strains. Chemosphere, 55(4), 533–538. [CrossRef]

- da Trindade, C. de M., da Silva, S. W., Bortolozzi, J. P., Banús, E. D., Bernardes, A. M., & Ulla, M. A. (2018). Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 films onto AISI 304 metallic meshes and their application in the decomposition of the endocrine-disrupting alkylphenolic chemicals. Applied Surface Science, 457, 644–654. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L., Wang, B., Heck, K., Guo, S., Clark, C. A., Arredondo, J., Wang, M., Senftle, T. P., Westerhoff, P., Wen, X., Song, Y., & Wong, M. S. (2020). Efficient Photocatalytic PFOA Degradation over Boron Nitride. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 7(8), 613–619. [CrossRef]

- Fang, P., Liu, B., Xu, J., Zhou, Q., Zhang, S., Ma, J., & lu, X. (2018). High-efficiency glycolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) by sandwich-structure polyoxometalate catalyst with two active sites. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 156, 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Farhadian Azizi, K., & Bagheri-Mohagheghi, M.-M. (2013). Transition from anatase to rutile phase in titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles synthesized by complexing sol–gel process: effect of kind of complexing agent and calcinating temperature. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 65(3), 329–335. [CrossRef]

- Gogate, P. R., & Pandit, A. B. (2004). A review of imperative technologies for wastewater treatment II: hybrid methods. Advances in Environmental Research, 8(3), 553–597. [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S., & Jamshidi, M. (2020). Sol–gel synthesis of carbon-doped TiO2 nanoparticles based on microcrystalline cellulose for efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under visible light. Environmental Technology, 41(24), 3233–3247. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Zhao, S., & Yu, Y. (2020). Experimental method to explore the adaptation degree of type-II and all-solid-state Z-scheme heterojunction structures in the same degradation system. Chinese Journal of Catalysis, 41(10), 1522–1534. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, I. C. R., Dubé, I. Z., & Sánchez, M. F. G. (2020). 1. MX2019002787 - Reactor fotocatalítico para la degradación de contaminantes orgánicos a presiones por encima de los valores ambientales (Patent No. 2019002787). 2019002787. https://www.wipo.int/ipcpub/?symbol=B01J0003000000&menulang=es&lang=es.

- Jiang, Q., Liu, J., Qi, T., & Liu, Y. (2022). Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity and antibacterial behaviour on fluorine and graphene synergistically modified TiO2 nanocomposite for wastewater treatment. Environmental Technology, 43(25), 3821–3834. [CrossRef]

- Kamari, H. M., Al-Hada, N. M., Baqer, A. A., Shaari, A. H., & Saion, E. (2019). Comprehensive study on morphological, structural and optical properties of Cr2O3 nanoparticle and its antibacterial activities. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 30(8), 8035–8046. [CrossRef]

- Kanakaraju, D., Motti, C. A., Glass, B. D., & Oelgemöller, M. (2014). Photolysis and TiO2-catalysed degradation of diclofenac in surface and drinking water using circulating batch photoreactors. Environmental Chemistry, 11(1), 51–62. [CrossRef]

- Kaneco, S., Rahman, M. A., Suzuki, T., Katsumata, H., & Ohta, K. (2004). Optimization of solar photocatalytic degradation conditions of bisphenol A in water using titanium dioxide. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 163(3), 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, C., Magesan, P., Gomathisankar, P., & Vinayagamoorthy, P. (2015). Absorption, emission, charge transfer resistance and photocatalytic activity of Al2O3/TiO2 core/shell nanoparticles. Superlattices and Microstructures, 83, 659–667. [CrossRef]

- Kleerebezem, R., Beckers, J., Hulshoff Pol, L. W., & Lettinga, G. (2005). High rate treatment of terephthalic acid production wastewater in a two-stage anaerobic bioreactor. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 91(2), 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnik, O. (2024). UV-Vis Spectrum of Terephthalic acid. SIELC Technologies. https://sielc.com/uv-vis-spectrum-of-terephthalic-acid.

- Krishnan, A., Swarnalal, A., Das, D., Krishnan, M., Saji, V. S., & Shibli, S. M. A. (2024). A review on transition metal oxides based photocatalysts for degradation of synthetic organic pollutants. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 139, 389–417. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R. M., Patwardhan, N. S., Iyer, P. B., & Bharadwaj, T. D. (2024). A review on microbial bioremediation of polyethylene terephthalate microplastics. Environmental Quality Management, 34(2), e22264.

- Kurokawa, H., Ohshima, M., Sugiyama, K., & Miura, H. (2003). Methanolysis of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in the presence of aluminium tiisopropoxide catalyst to form dimethyl terephthalate and ethylene glycol. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 79(3), 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Zhang, W., Xia, D., Ye, L., Ma, W., Li, H., Li, Q., & Wang, Y. (2022). Improved anaerobic degradation of purified terephthalic acid wastewater by adding nanoparticles or co-substrates to facilitate the electron transfer process. Environmental Science: Nano, 9(3), 1011–1024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Iocozzia, J., Wang, Y., Cui, X., Chen, Y., Zhao, S., Li, Z., & Lin, Z. (2017). Noble metal–metal oxide nanohybrids with tailored nanostructures for efficient solar energy conversion, photocatalysis and environmental remediation. Energy & Environmental Science, 10(2), 402–434. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Wan, Y., & Zhang, X. (2023). Preparation and Corrosion Properties of TiO2-SiO2-Al2O3 Composite Coating on Q235 Carbon Steel. In Coatings (Vol. 13, Issue 12). [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., Xiang, Y., Tian, T., & Pan, X. (2021). An AFM-IR study on surface properties of nano-TiO2 coated polyethylene (PE) thin film as influenced by photocatalytic aging process. Science of The Total Environment, 757, 143900. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K., Li, X., Bao, L., Li, X., & Cui, Y. (2020). The performance and bacterial community shifts in an anaerobic-aerobic process treating purified terephthalic acid wastewater under influent composition variations and ambient temperatures. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 124190. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Li, X., Wang, X., Liu, G., Zuo, J., Wang, S., & Wang, K. (2020). Impact of salinity on anaerobic microbial community structure in high organic loading purified terephthalic acid wastewater treatment system. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 383, 121132. [CrossRef]

- Magnone, E., Kim, M. K., Lee, H. J., & Park, J. H. (2021). Facile synthesis of TiO2-supported Al2O3 ceramic hollow fiber substrates with extremely high photocatalytic activity and reusability. Ceramics International, 47(6), 7764–7775. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, N. M., & Arami, M. (2006). Bulk phase degradation of Acid Red 14 by nanophotocatalysis using immobilized titanium(IV) oxide nanoparticles. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 182(1), 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gómez, C., Rangel-Vazquez, I., Zarraga, R., del Ángel, G., Ruíz-Camacho, B., Tzompantzi, F., Vidal-Robles, E., & Perez-Larios, A. (2022). Photodegradation and Mineralization of Phenol Using TiO2Coated γ-Al2O3: Effect of Thermic Treatment. In Processes (Vol. 10, Issue 6). [CrossRef]

- Mazzarino, I., & Piccinini, P. (1999). Photocatalytic oxidation of organic acids in aqueous media by a supported catalyst. Chemical Engineering Science, 54(15), 3107–3111. [CrossRef]

- Merino, N., Qu, Y., Deeb, R. A., Hawley, E. L., Hoffmann, M. R., & Mahendra, S. (2016). Degradation and Removal Methods for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Water. Environmental Engineering Science, 33(9), 615–649. [CrossRef]

- Miglierini, M. B., Pašteka, L., Cesnek, M., Kmječ, T., Bujdoš, M., & Kohout, J. (2019). Influence of surface treatment on microstructure of stainless steels studied by Mössbauer spectrometry. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 322(3), 1495–1503. [CrossRef]

- Miwa, T., Kaneco, S., Katsumata, H., Suzuki, T., Ohta, K., Chand Verma, S., & Sugihara, K. (2010). Photocatalytic hydrogen production from aqueous methanol solution with CuO/Al2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 35(13), 6554–6560. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sierra, J. D., Lafita, C., Gabaldón, C., Spanjers, H., & van Lier, J. B. (2017). Trace metals supplementation in anaerobic membrane bioreactors treating highly saline phenolic wastewater. Bioresource Technology, 234, 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Mwema, F. M., Oladijo, O. P., Sathiaraj, T. S., & Akinlabi, E. T. (2018). Atomic force microscopy analysis of surface topography of pure thin aluminum films. Materials Research Express, 5(4), 46416. [CrossRef]

- Oladijo, O. P., Popoola, A. P. I., Booi, M., Fayomi, J., & Collieus, L. L. (2020). Corrosion and mechanical behaviour of Al2O3TiO2 composites produced by spark plasma sintering. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering, 33, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Park, T.-J., Lim, J. S., Lee, Y.-W., & Kim, S.-H. (2003). Catalytic supercritical water oxidation of wastewater from terephthalic acid manufacturing process. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 26(3), 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Yang, J., Deng, C., Deng, J., Shen, L., & Fu, Y. (2023). Acetolysis of waste polyethylene terephthalate for upcycling and life-cycle assessment study. Nature Communications, 14(1), 3249. [CrossRef]

- Radoń, A., Drygała, A., Hawełek, Ł., & Łukowiec, D. (2017). Structure and optical properties of Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method with different organic modifiers. Materials Characterization, 131, 148–156. [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y., Zhong, J., Li, J., Li, M., & Tian, C. (2023). Substantially boosted photocatalytic detoxification activity of TiO2 benefited from Eu doping. Environmental Technology, 44(9), 1313–1321. [CrossRef]

- Sacco, O., Vaiano, V., Rizzo, L., & Sannino, D. (2018). Photocatalytic activity of a visible light active structured photocatalyst developed for municipal wastewater treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 175, 38–49. [CrossRef]

- Sadeq, Z. S., Mahdi, Z. F., & Hamza, A. M. (2019). Low cost, fast and powerful performance interfacial charge transfer nanostructured Al2O3 capturing of light photocatalyst eco-friendly system using hydrothermal method. Materials Letters, 254, 120–124. [CrossRef]

- Samy, M., Ibrahim, M. G., Fujii, M., Diab, K. E., ElKady, M., & Gar Alalm, M. (2021). CNTs/MOF-808 painted plates for extended treatment of pharmaceutical and agrochemical wastewaters in a novel photocatalytic reactor. Chemical Engineering Journal, 406, 127152. [CrossRef]

- Sannino, D., Vaiano, V., Sacco, O., Morante, N., Guglielmo, L. De, Capua, G. Di, & Femia, N. (2021). Visible Light Driven Degradation of Terephthalic Acid: Optimization of Energy Demand by Light Modulation Techniques. In Journal of Photocatalysis (Vol. 2, Issue 1, pp. 49–61). [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A., Nikazar, M., & Arami, M. (2010). Photocatalytic degradation of terephthalic acid using titania and zinc oxide photocatalysts: Comparative study. Desalination, 252(1), 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Skoog, D. A., Holler, F. J., & Crouch, S. R. (2008). Principios de Análisis Instrumental (sexta edición ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Sun, Y., Tian, L., Liu, B., Chen, F., & Ge, S. (2021). Photocatalytic Destruction of Gaseous Benzene Using Mn/I-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticle Catalytic Under Visible Light. Environmental Engineering Science, 39(3), 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, M., & Eskander, S. (2015). Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate Plastic Wastes based on unsaturated Diol. KGK Rubberpoint, 68, 21–27.

- Thiruvenkatachari, R., Kwon, T. O., Jun, J. C., Balaji, S., Matheswaran, M., & Moon, I. S. (2007). Application of several advanced oxidation processes for the destruction of terephthalic acid (TPA). Journal of Hazardous Materials, 142(1), 308–314. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L., Alizadeh, A. A., Gentles, A. J., & Tibshirani, R. (2014). A Simple Method for Estimating Interactions between a Treatment and a Large Number of Covariates. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 109(508), 1517–1532. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xu, M., Li, J., & Zhang, T. (2024). Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using Al/TiO2 Composites Under Visible Light. Environmental Engineering Science, 41(5), 204–215. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Luo, W. P., Zhang, X. Y., Guo, C. C., Liu, Q., Jiang, G. F., & Li, Q. H. (2010). Aerobic Oxidation of p-Toluic Acid to Terephthalic Acid over T(p-Cl)PPMnCl/Co(OAc)2 Under Moderate Conditions. Catalysis Letters, 134(1), 155–161. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Song, H., & Chou, L. (2012). Facile synthesis of nano-crystalline alpha-alumina at low temperature via an absolute ethanol sol–gel strategy. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 132(2), 1071–1076. [CrossRef]

- Yakdoumi, F. Z., & Hadj-Hamou, A. S. (2020). Effectiveness assessment of TiO2-Al2O3 nano-mixture as a filler material for improvement of packaging performance of PLA nanocomposite films. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 40(10), 848–858. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., Cheng, S. P., Zhang, X. X., Shi, L., & Zhu, C. J. (2004). Effects of Four Metals on the Degradation of Purified Terephthalic Acid Wastewater by Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Strain Fhhh. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 72(2), 387–393. [CrossRef]

- Žerjav, G., Albreht, A., Vovk, I., & Pintar, A. (2020). Revisiting terephthalic acid and coumarin as probes for photoluminescent determination of hydroxyl radical formation rate in heterogeneous photocatalysis. Applied Catalysis A: General, 598, 117566. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wu, J., Li, R., Kim, D.-H., Bi, X., Zhang, G., Jiang, B., Yong Ng, H., & Shi, X. (2022). Novel intertidal wetland sediment-inoculated moving bed biofilm reactor treating high-salinity wastewater: Metagenomic sequencing revealing key functional microorganisms. Bioresource Technology, 348, 126817. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Li, R., Li, Z., Li, A., Wang, S., Liang, Z., Liao, S., & Li, C. (2016). The dependence of photocatalytic activity on the selective and nonselective deposition of noble metal cocatalysts on the facets of rutile TiO2. Journal of Catalysis, 337, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, Y., Wu, Q., & Hu, H. (2011). Removal of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds, Estrogenic Activity, and Escherichia coliform from Secondary Effluents in a TiO2-Coated Photocatalytic Reactor. Environmental Engineering Science, 29(3), 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yang, S., Li, J., & Wu, J. (2020). Temperature-dependent evolution of oxide inclusions during heat treatment of stainless steel with yttrium addition. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials, 27(6), 754–763. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., Lu, Q., Lv, L., Wang, Y., Hu, Y., Deng, Z., Lou, Z., Hou, Y., & Teng, F. (2017). Ligand-free rutile and anatase TiO2 nanocrystals as electron extraction layers for high performance inverted polymer solar cells. RSC Advances, 7(33), 20084–20092. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Ning, Y., Li, L., Chen, Z., Li, H., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Effective removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous system by biochar-supported titanium dioxide (TiO2). Environmental Chemistry, 19(7), 432–445. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Jurek, A., Wysocka, I., Janczarek, M., Stampor, W., & Hupka, J. (2015). Preparation and characterization of Pt–N/TiO2 photocatalysts and their efficiency in degradation of recalcitrant chemicals. Separation and Purification Technology, 156, 369–378. [CrossRef]

| Phase | % | Lattice parameters (nm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | ||

| 35.0 | 0.4748 | − | 1.294 | |

| 14.3 | 0.8017 | − | − | |

| 32.8 | 0.3801 | − | 0.9595 | |

| 17.6 | 0.4620 | − | 0.2958 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).