Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

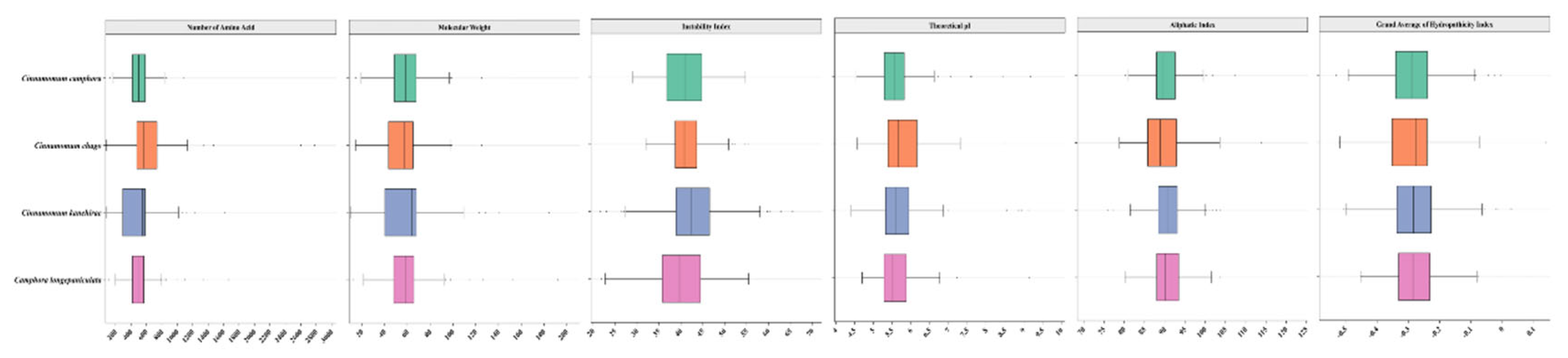

Characterization of TPS Gene Family

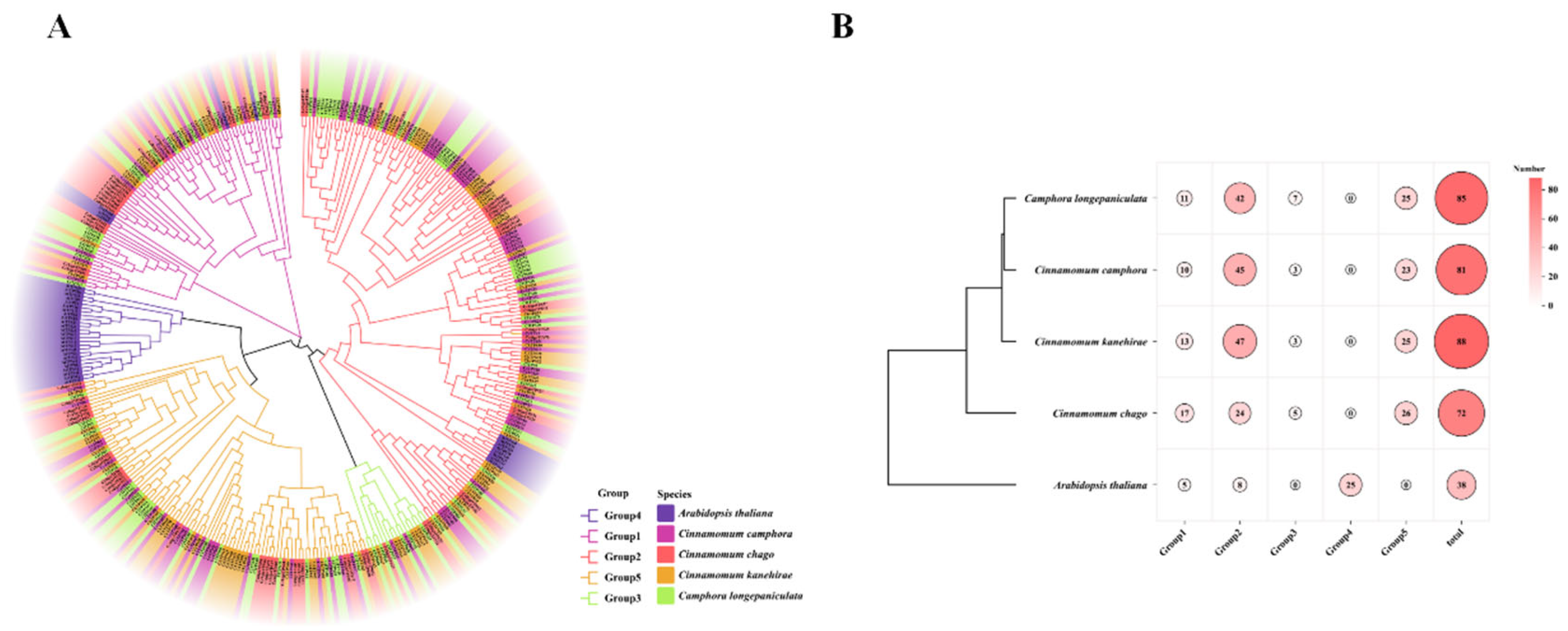

Analysis of Phylogenetic Relationships of TPS Gene Family

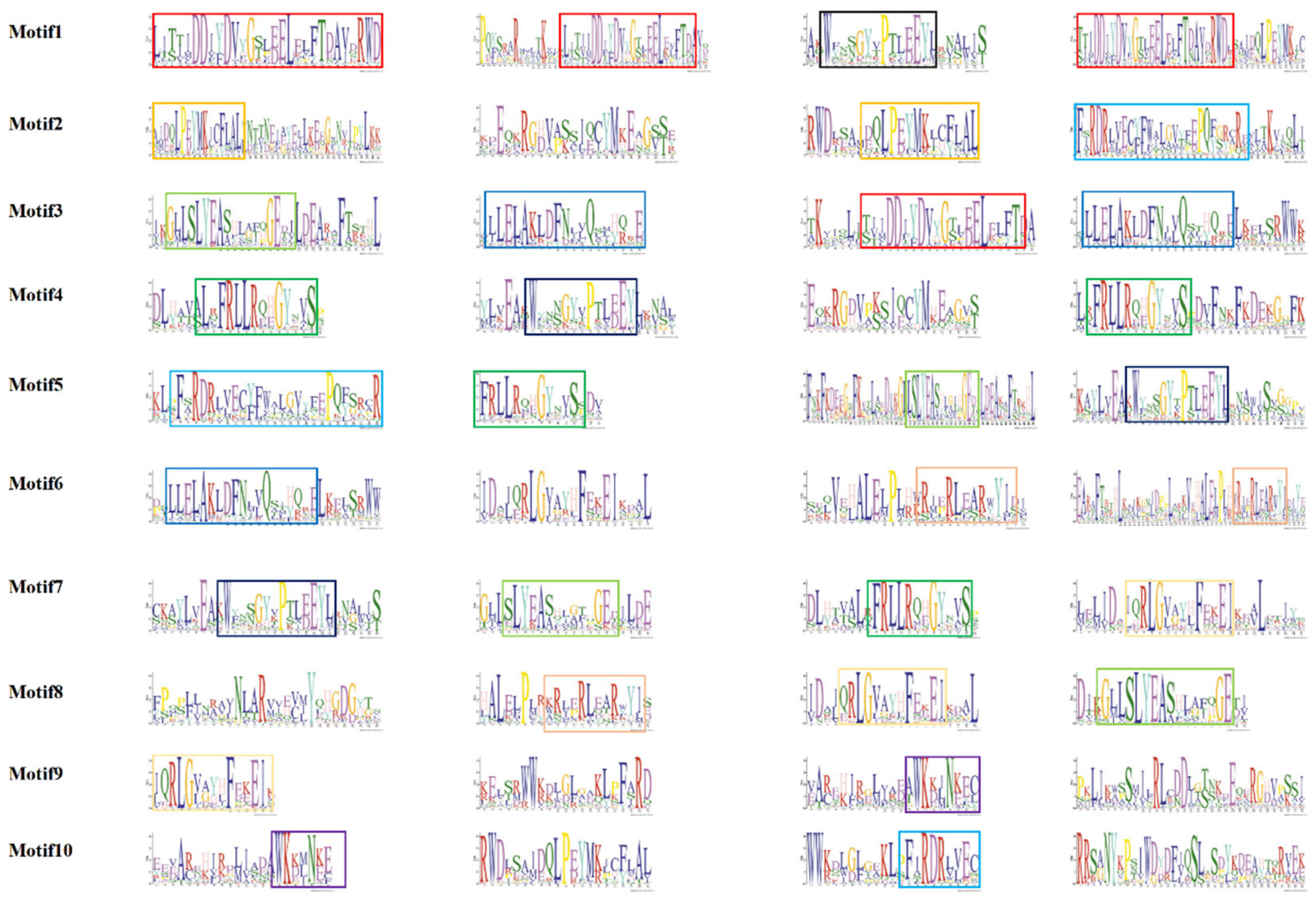

Conserved Motifs Analysis of TPS Gene Family

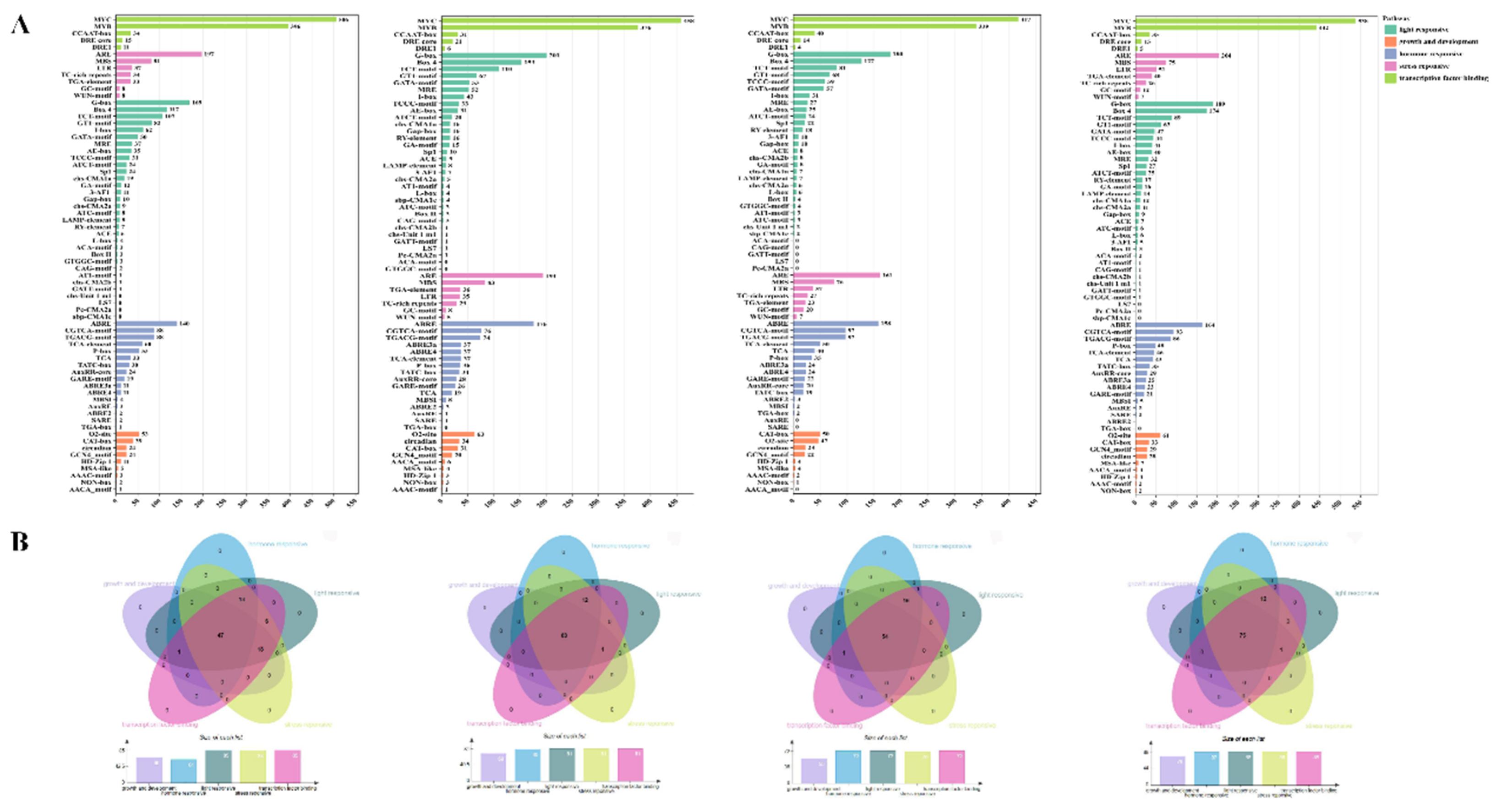

Promoters Analysis of TPS Genes

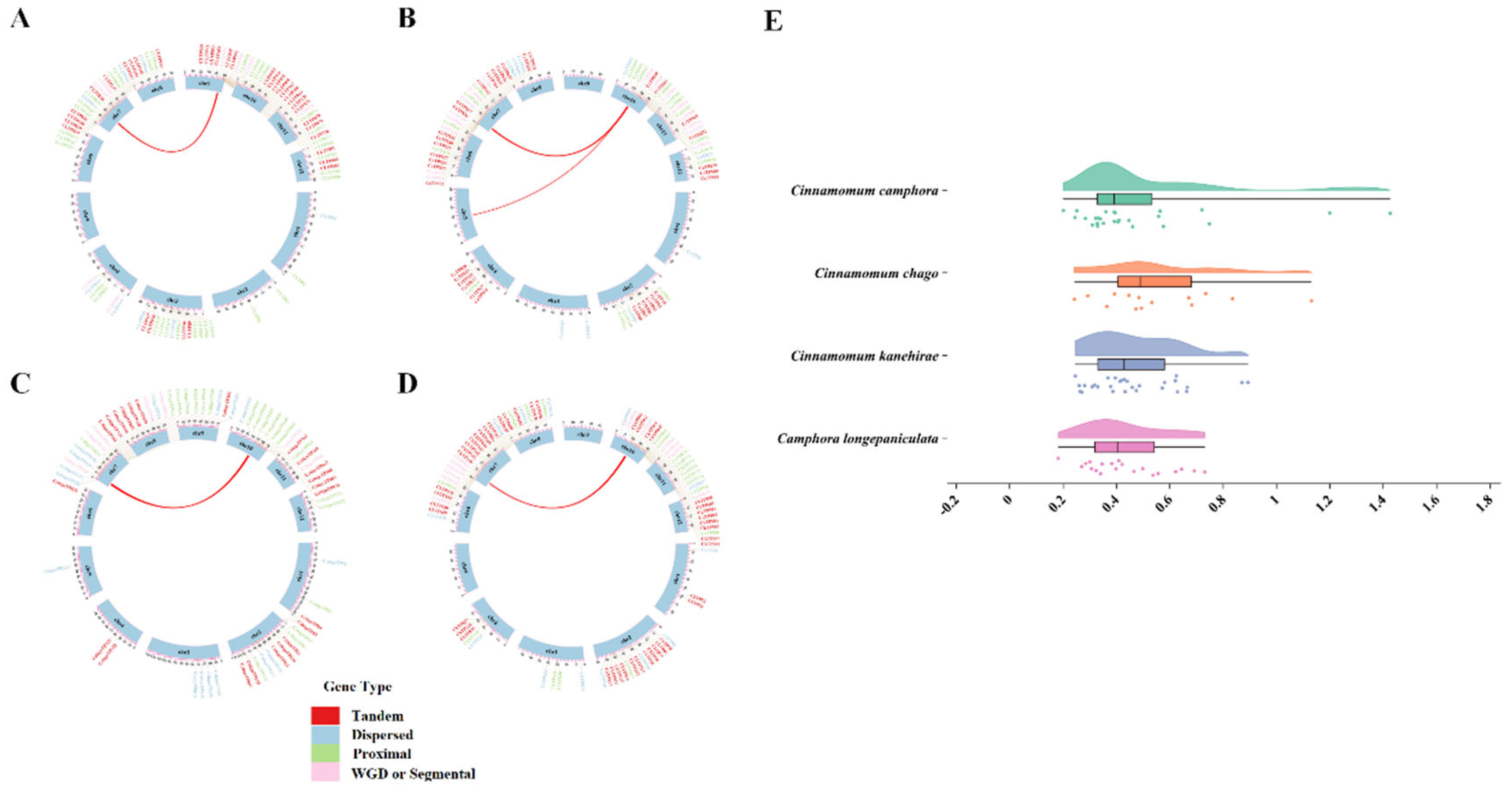

Duplication Events Analysis of TPS Genes

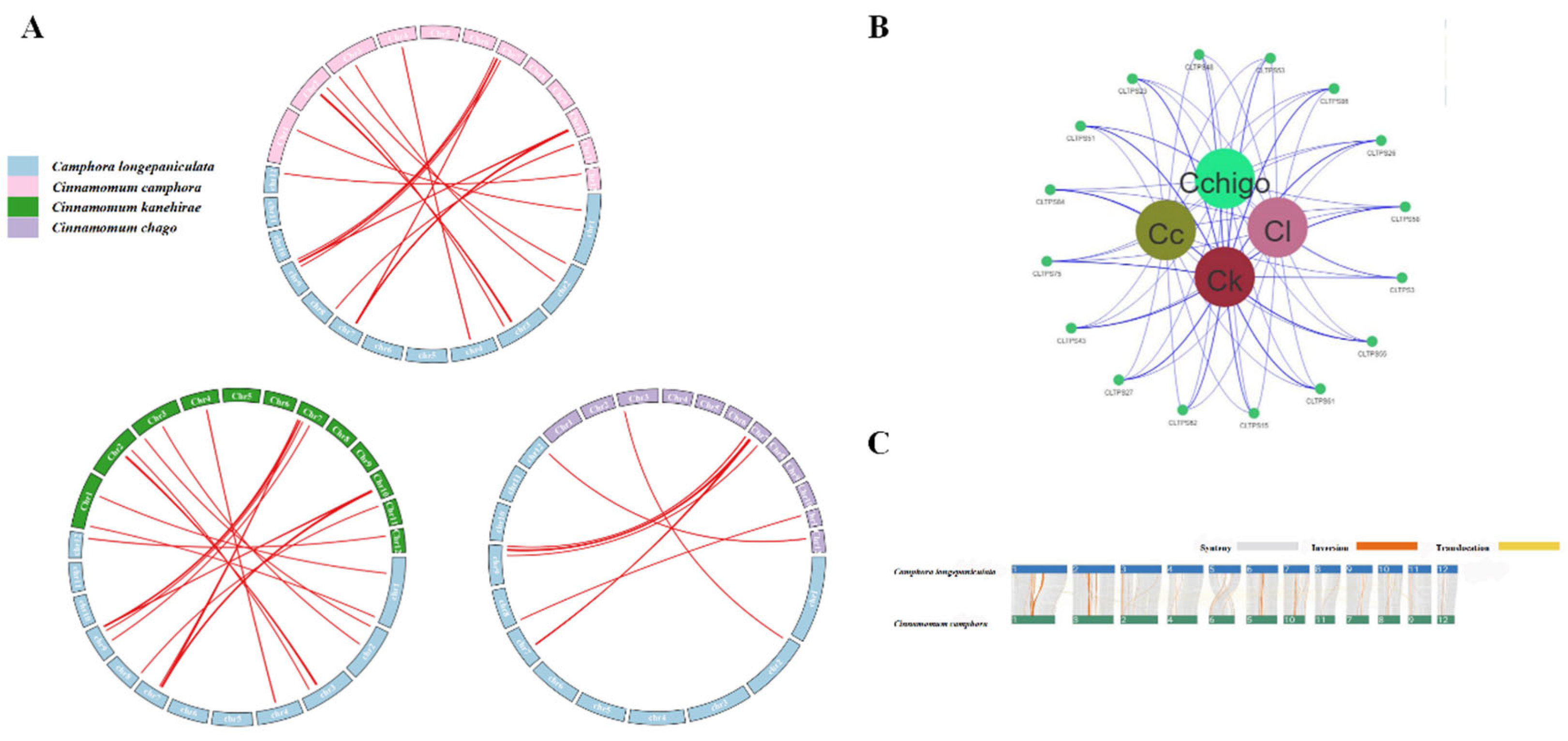

Collinearity Analysis of TPS Genes

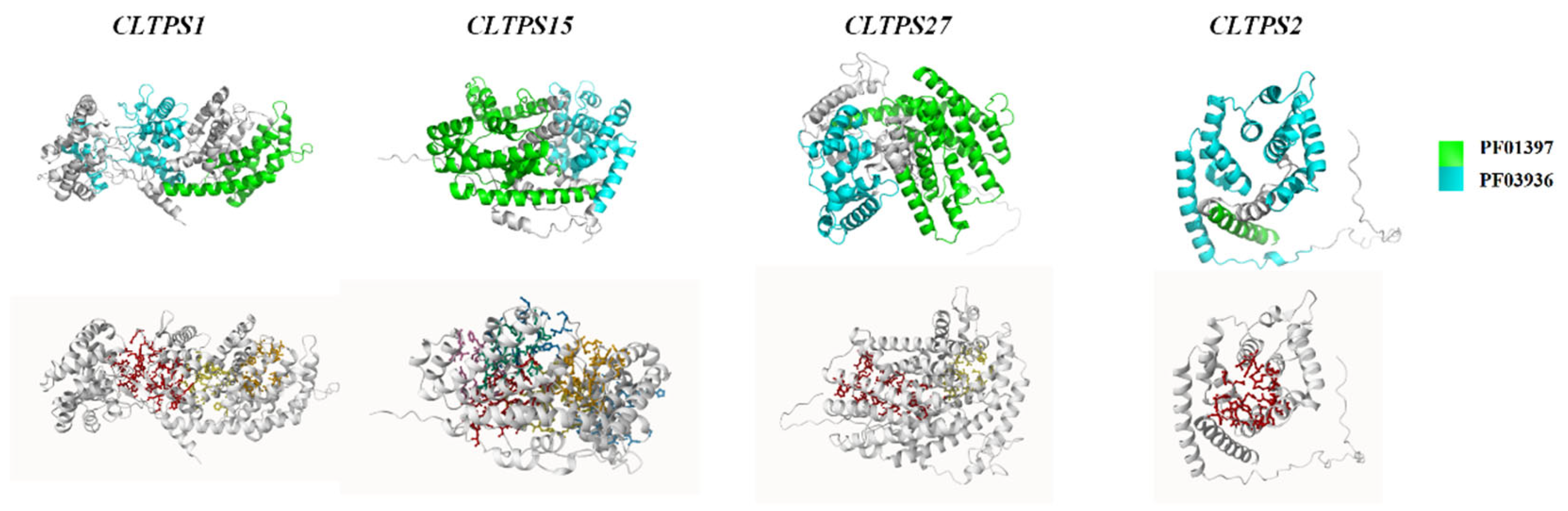

Prediction of Protein 3D Structure

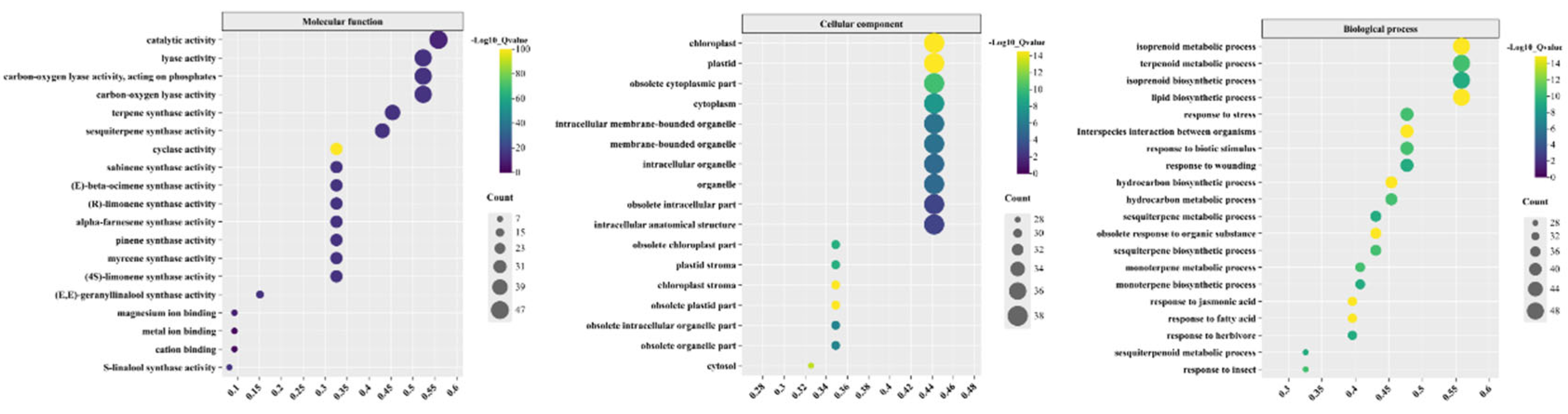

Gene Ontology Functional Annotation of CLTPSs

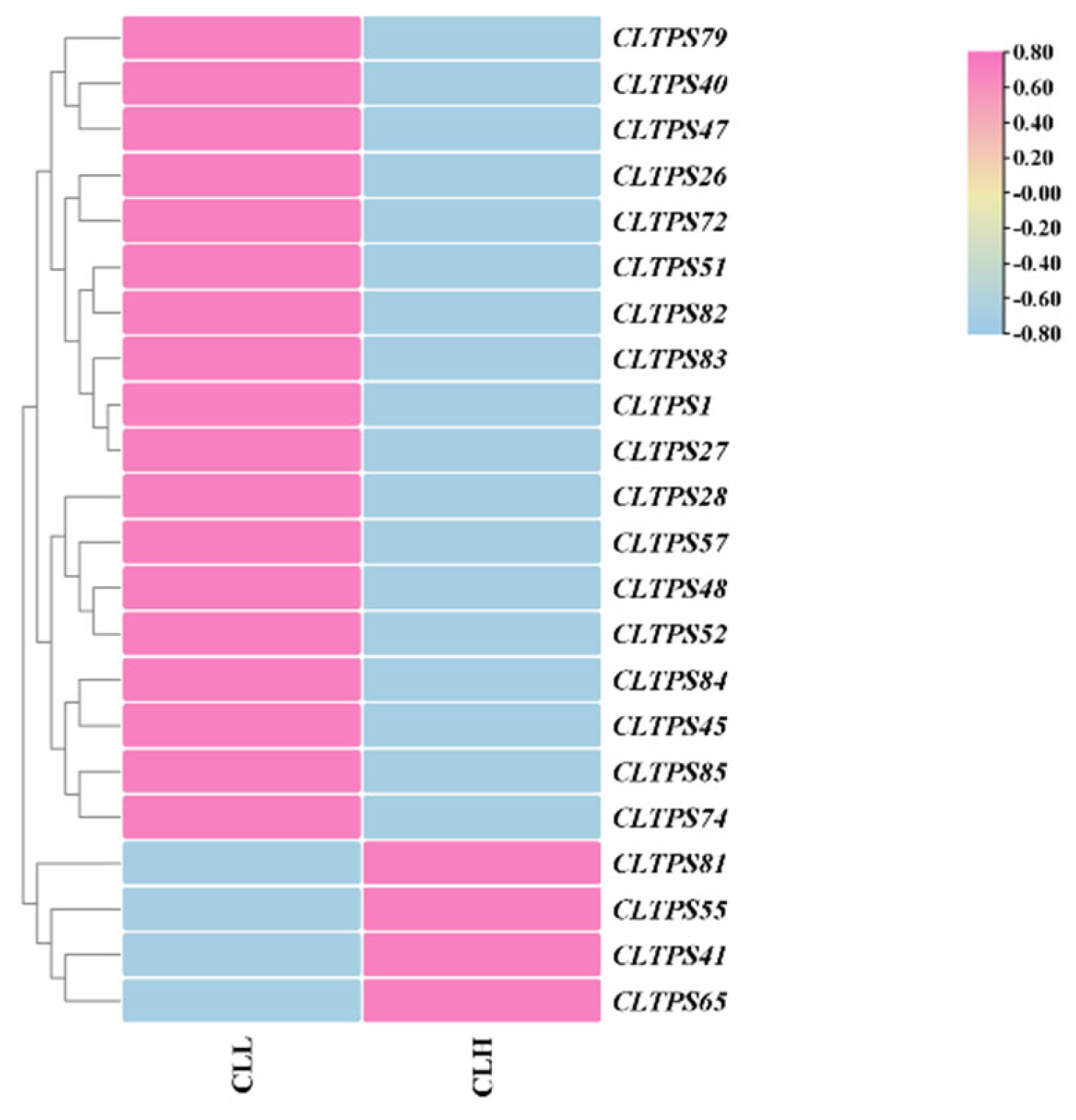

Expression Analysis of CLTPSs in C. longepaniculatum Varieties with Different Essential Oil Contents

Discussion

Materials and Methods

Identification and Chromosomal Location of TPS Gene Family in C. longepaniculata

Phylogenetic Relationship and Conserved Motifs Analysis

Analysis of Promoter Cis-Acting Elements

Synteny Analysis for TPS Genes

Prediction of Protein Pocket Binding Sites

Gene Ontology

Expression Patterns of Cltpss in C. longepaniculata With High Terpenoid Content

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bohlmann, J.; Keeling, C.I. Terpenoid Biomaterials. The Plant Journal 2008, 54, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreto, F.; Dicke, M.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Turlings, T.C. Plant Volatiles and the Environment. Plant, cell & environment 2014, 37, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A.-X.; Lou, Y.-G.; Mao, Y.-B.; Lu, S.; Wang, L.-J.; Chen, X.-Y. Plant Terpenoids: Biosynthesis and Ecological Functions. Journal of integrative plant biology 2007, 49, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarvey, D.J.; Croteau, R. Terpenoid Metabolism. The plant cell 1995, 7, 1015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zha, W.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; You, A. Advances in the Biosynthesis of Terpenoids and Their Ecological Functions in Plant Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 11561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangeer, M.; Fatima, R.; Ashiq, M.; Basharat, A.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H. Therapeutic and Biomedical Potentialities of Terpenoids-A Review. Journal of Pure & Applied Microbiology 2021, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Mabou, F.D.; Yossa, I.B.N. Terpenes: Structural Classification and Biological Activities. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci 2021, 16, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- O’maille, P.E.; Malone, A.; Dellas, N.; Andes Hess Jr, B.; Smentek, L.; Sheehan, I.; Greenhagen, B.T.; Chappell, J.; Manning, G.; Noel, J.P. Quantitative Exploration of the Catalytic Landscape Separating Divergent Plant Sesquiterpene Synthases. Nature chemical biology 2008, 4, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmisch, S.; Krause, S.T.; Kunert, G.; Gershenzon, J.; Degenhardt, J.; Köllner, T.G. The Organ-Specific Expression of Terpene Synthase Genes Contributes to the Terpene Hydrocarbon Composition of Chamomile Essential Oils. BMC Plant Biology 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Raguso, R.A. Why Do Plants Produce so Many Terpenoid Compounds? New Phytologist 2018, 220, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huang, X.; Jing, W.; An, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y. Identification and Functional Analysis of Two P450 Enzymes of Gossypium Hirsutum Involved in DMNT and TMTT Biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2018, 16, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tholl, D. Biosynthesis and Biological Functions of Terpenoids in Plants. Biotechnology of isoprenoids 2015, 63–106. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, J.; Köllner, T.G.; Gershenzon, J. Monoterpene and Sesquiterpene Synthases and the Origin of Terpene Skeletal Diversity in Plants. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.-L.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, C.-L.; Zeng, Q.-Y. Molecular Evolution of Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase (TPS) Gene Family in Populus, Arabidopsis and Rice. 2012.

- Chen, F.; Tholl, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Pichersky, E. The Family of Terpene Synthases in Plants: A Mid-Size Family of Genes for Specialized Metabolism That Is Highly Diversified throughout the Kingdom. The Plant Journal 2011, 66, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesteene, L.; Ramon, M.; Le Roy, K.; Van Dijck, P.; Rolland, F. A Single Active Trehalose-6-P Synthase (TPS) and a Family of Putative Regulatory TPS-like Proteins in Arabidopsis. Molecular plant 2010, 3, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mattson, N.; Yang, L.; Jin, Q. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Solanum Tuberosum (Potato) Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase (TPS) Gene Family: Evolution and Differential Expression during Development and Stress. BMC genomics 2017, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D.A.; Wise, M.L.; Urbansky, M.; Coates, R.M.; Croteau, R.B.; Christianson, D.W. Bornyl Diphosphate Synthase: Structure and Strategy for Carbocation Manipulation by a Terpenoid Cyclase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 15375–15380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhu, P.; Wu, H.; Dai, H. Industry Development Status and Prospect of Cinnamomum Longepaniculatum. Open Access Library Journal 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Gao, H.; Jiang, X.; Yang, H. Analysis on Constituents and Contents in Leaf Essential Oil from Three Chemical Types of Cinnamum Camphora. J Cent South Univ Technol 2012, 32, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zu, Y.; Wang, W. Antibacterial and Antioxidant of Celery Seed Essential Oil. Chin Condiment 2012, 37, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Li, Z.-W.; Yin, Z.-Q.; Wei, Q.; Jia, R.-Y.; Zhou, L.-J.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, Y.-H.; et al. Antibacterial Activity of Leaf Essential Oil and Its Constituents from Cinnamomum Longepaniculatum. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 2014, 7, 1721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, W.; Feng, R.; Shuai, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, M.; He, X.; Wei, Q. Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveal the Accumulation of Secondary Metabolites in Different Varieties of Cinnamomum Longepaniculatum. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.-M.; Zhou, S.-S.; Liu, H.; Zhao, S.-W.; Tian, X.-C.; Shi, T.-L.; Bao, Y.-T.; Li, Z.-C.; Jia, K.-H.; Nie, S.; et al. Unraveling the Evolutionary Dynamics of the TPS Gene Family in Land Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1273648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-del-Río, I.; López-Ibáñez, S.; Magadán-Corpas, P.; Fernández-Calleja, L.; Pérez-Valero, Á.; Tuñón-Granda, M.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J.; Lombó, F. Terpenoids and Polyphenols as Natural Antioxidant Agents in Food Preservation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Santosh Kumar, V.V.; Verma, R.K.; Yadav, P.; Saroha, A.; Wankhede, D.P.; Chaudhary, B.; Chinnusamy, V. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of ABA Receptor PYL Gene Family in Rice. BMC genomics 2020, 21, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yan, K.; Ren, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Q.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Q. Genome-Wide Investigation of the PYL Genes in Acer Palmatum and Their Role in Freezing Tolerance. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 210, 118107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Paterson, A.H. Genome and Gene Duplications and Gene Expression Divergence: A View from Plants. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2012, 1256, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delph, L.F.; Kelly, J.K. On the Importance of Balancing Selection in Plants. New phytologist 2014, 201, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Zhu, H.; Cao, G.; Meng, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, R.; Soaud, S.A.; et al. Chromosome Genome Assembly of the Camphora Longepaniculata (Gamble) with PacBio and Hi-C Sequencing Data. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1372127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Guo, S.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, R.; Sun, W. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Threatened Resource Plant Cinnamomum Chago. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaw, S.-M.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-W.; Wang, H.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y.I.; Wu, C.-S.; Ke, H.-M.; Chang, L.-Y.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Yang, H.-T.; et al. Stout Camphor Tree Genome Fills Gaps in Understanding of Flowering Plant Genome Evolution. Nature plants 2019, 5, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Lin, H.-Y.; Wang, X.; Bi, B.; Gao, Y.; Shao, L.; Zhang, R.; Liang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Y.-P.; et al. Genome and Whole-Genome Resequencing of Cinnamomum Camphora Elucidate Its Dominance in Subtropical Urban Landscapes. BMC biology 2023, 21, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Finn, R.D.; Eddy, S.R.; Bateman, A.; Punta, M. Challenges in Homology Search: HMMER3 and Convergent Evolution of Coiled-Coil Regions. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, e121–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular biology and evolution 2018, 35, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for Motif Discovery and Searching. Nucleic acids research 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, R.A.M.; Chen, Z.J. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis 2019.

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, e49–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Molecular Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.-X.; Huang, L. Visualizing Set Relationships: EVenn’s Comprehensive Approach to Venn Diagrams. iMeta 2024, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.-Q.; Wang, J.; Wong, G.K.-S.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator: Calculating Ka and Ks through Model Selection and Model Averaging. Genomics, proteomics and bioinformatics 2006, 4, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-W.; Yu, Z.-G.; Huang, X.-M.; Liu, J.-S.; Guo, Y.-X.; Chen, L.-L.; Song, J.-M. GenomeSyn: A Bioinformatics Tool for Visualizing Genome Synteny and Structural Variations. Journal of genetics and genomics= Yi chuan xue bao 2022, 49, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W.L. ; others Pymol: An Open-Source Molecular Graphics Tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr 2002, 40, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Forslund, K.; Coelho, L.P.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L.J.; Von Mering, C.; Bork, P. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Molecular biology and evolution 2017, 34, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-Optimal Probabilistic RNA-Seq Quantification. Nature biotechnology 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).