The issue of facility location planning, especially in the domain of public health facilities, is significant [

1]. The term “facility location” refers to the process of determining the optimal locations for facilities where services are provided to a certain population. Facility location involves considerations such as accessibility, service coverage, cost-effectiveness, and the socio-economic impact of the facility location on the surrounding community. In the context of healthcare facility location, it entails determining the optimal locations for the establishment of medical facilities to provide timely and effective healthcare services to the population [

2]. Several studies and research have been conducted in the field of hub location so far [

3,

4,

5,

6]. including both emergency and non-emergency facilities. However, a crucial aspect that has received less attention so far is the comprehensive evaluation of facility locations’ efficiency [

7,

8]. This entails assessing whether the decisions made over time regarding the location of facilities, considering various needs and constraints, are collectively optimal. Therefore, it is essential to comprehensively examine whether the chosen hub locations are optimal across different time periods and in relation to each other [

9]. Therefore, the topic of optimal hub location is raised in a multidimensional manner, where the aim is to comprehensively and systematically examine the optimality of hub locations across the entire target region, and if necessary, to carry out hub location [

10]. This hub location may involve establishing new hubs, removing existing hubs, increasing or decreasing the capacity of a hub. If the location is not considered for the target area, we will face a number of local optimal solutions, each obtained at a specific time, which not only may not provide us with a globally optimal solution but also does not consider the changes in demand over time in the covered areas after the location is determined [

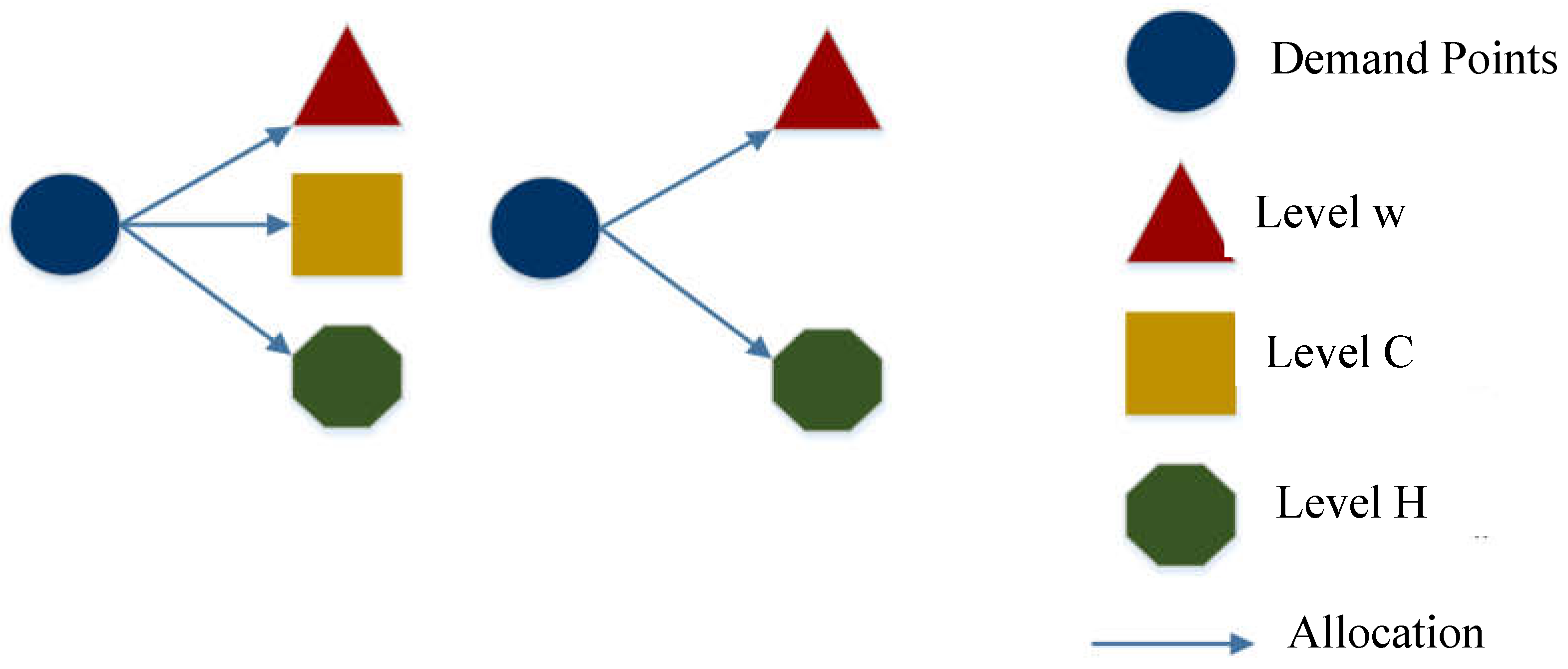

11]. One of the challenges in the hub location problem is considering the hubs at different points equally and with similar services and capacities. This is because the characteristics of the selected locations, constraints, and the type and amount of needs in each area are not necessarily similar to each other, and these differences make uniform facilities not have sufficient efficiency [

12]. From these differences, we can, for example, mention the following: In an area with a high population density, there is a need for facilities with high capacity, or in an area where there are suitable and extensive access routes, the coverage radius of a hub can be greater than other hubs or the types of needs may vary in different areas and require hubs with different services [

13]. Despite these conditions, to reach an optimal solution, facilities with different characteristics and capacities should be considered. This is known in location literature as hub location, and considering this feature can lead to a more suitable solution for the problem [

14]. In the field of hub location in various domains, including healthcare, uncertainty is one of the influential factors. For various facilities, many parameters such as the amount, type, and timing of demand creation are uncertain, and considering this uncertainty in the parameters can increase the practicality of the problem [

15]. One of the assumptions that has been prevalent in location problems in the past is the assumption of facilities operating under different conditions [

16]. However, this assumption is not valid in the real world, and facilities may be disrupted due to various reasons such as pollution and environmental issues, causing their activities to be halted [

17]. The reasons for disruptions can be natural, such as disruptions due to the failure of wastewater and air catalysts, or human-induced, such as disruptions in the performance of air, water, and soil settlement due to operational errors [

18]. Therefore, considering the probability of disruptions in pollutant production and providing a model that can continue its work under environmental disruption conditions is of paramount importance and high applicability [

14]. In this article, we also attempt to provide a model that addresses hub location in a green state by considering environmental disruptions. Another aspect to consider in hub location is the limitations present in facility capacities and communication routes. Each facility has a limited capacity based on various factors, and it cannot provide services beyond this capacity. Therefore, considering limited capacities for facilities is necessary, and if these constraints are not considered, we deviate from real conditions, and the model will not be practical. On the other hand, many hub location problems have multiple objectives [

19,

20,

21].

The objectives commonly considered in hub location problems are summarized below. Cost is one of the most common objectives in hub location problems [

5]. Costs come in various types, divided into variable and fixed costs. Variable costs include installation expenses, while fixed costs include relocation expenses [

15]. Typically, in hub location problems, a unified objective comprising all types of costs is considered. Another objective is coverage, which is used in maximal coverage problems. In this case, an objective is added to the model to maximize demand coverage. Other objectives exist in hub location problems, but we will not delve into them here. In this study, we aim to establish a balance between objectives such as maximizing demand coverage, minimizing costs, and maximizing greenness in the hub location.

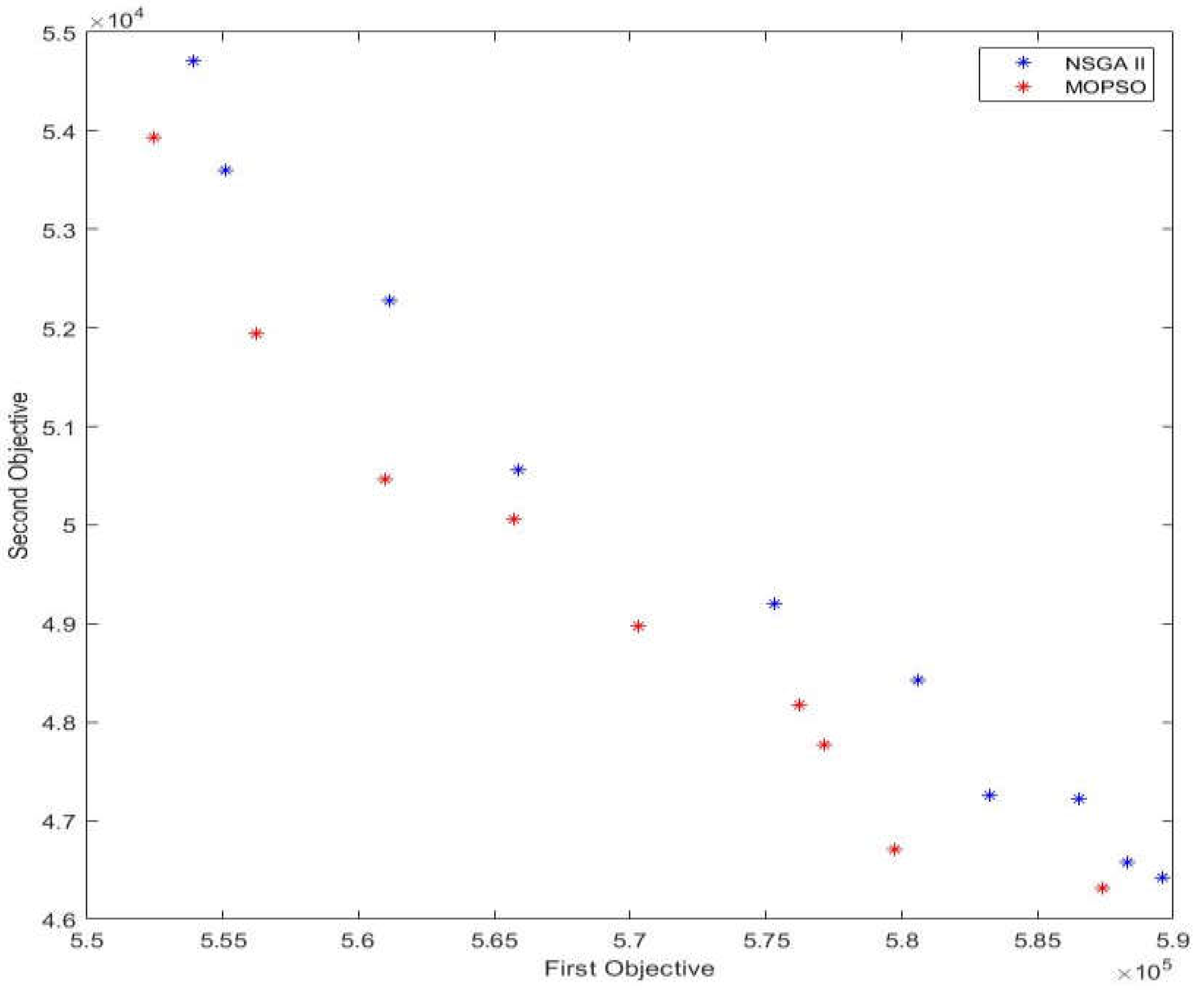

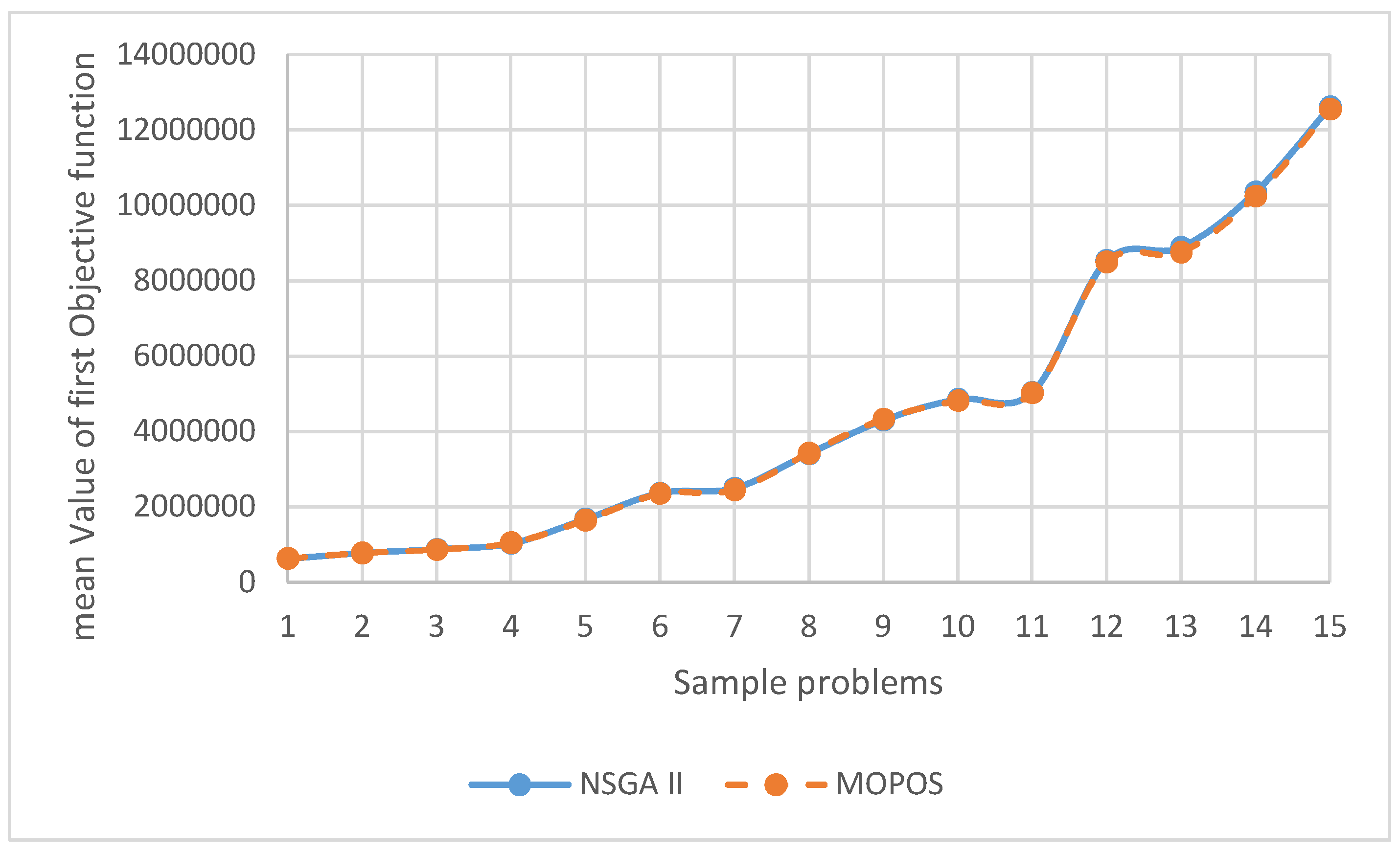

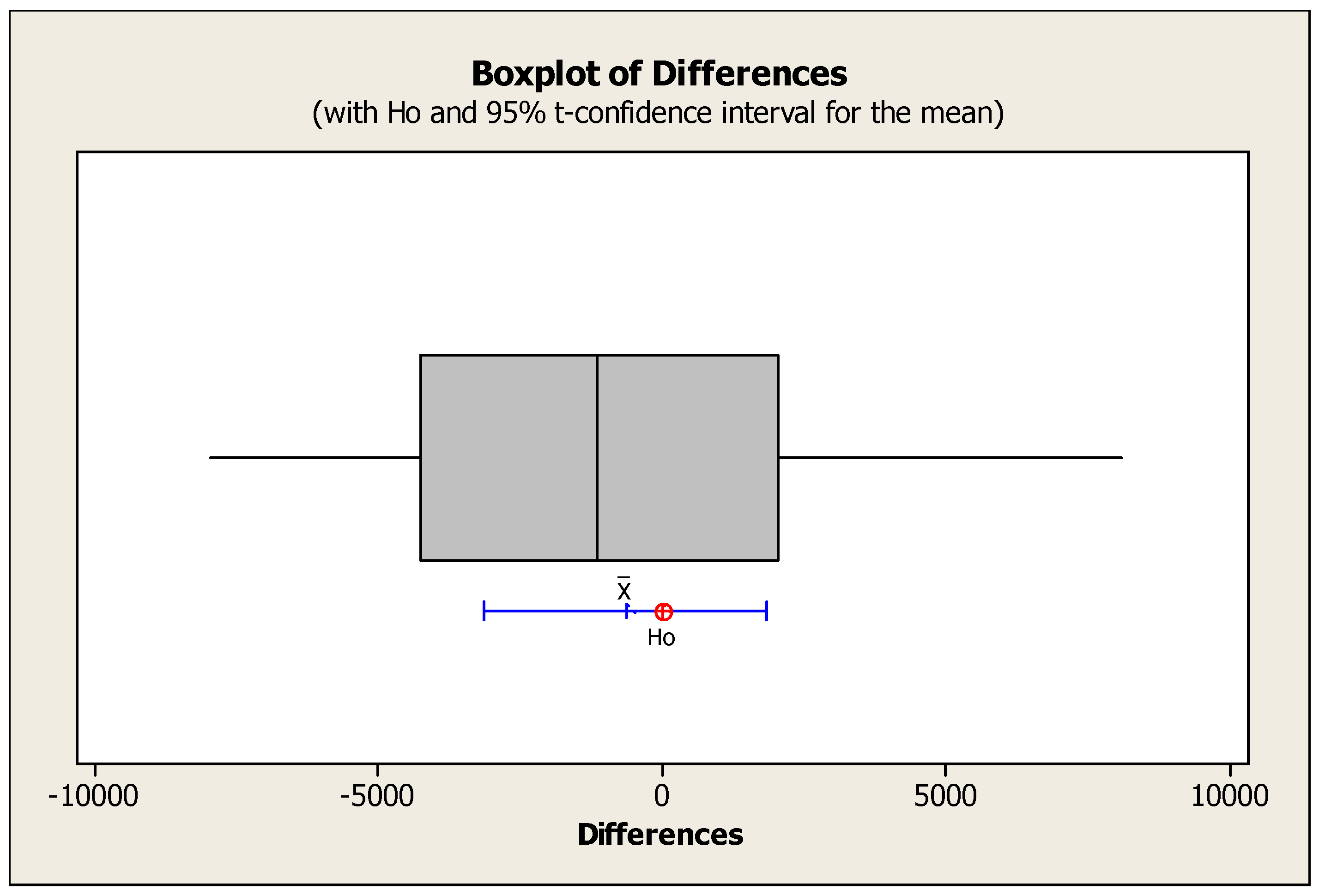

This article presents a multi-objective mathematical programming model in which the objectives of cost, demand coverage, and greenness of location are considered, aiming to address hub location under a comprehensive perspective to examine the optimality of the current facility locations and, if necessary, relocate existing facilities or locate new facilities. In order to find an effective and efficient solution, factors of uncertainty are also addressed. Given the nature of the problem under study and researchers’ opinions, the hub location model is NP-HARD. To validate the mathematical model, initially, the Pareto front of optimal solutions will be evaluated using an epsilon-constraint approach, and ultimately, to validate the model on larger scales, metaheuristic algorithms will be utilized. This article consists of five sections. The first section discusses the problem under study. The second section reviews the research literature, and the third section presents the mathematical model. The fourth section analyzes the mathematical model, and finally, conclusions and future research recommendations are provided.