1. Introduction

Although dental implants generally have high success rates for the rehabilitation of missing teeth, their long-term maintenance directly depends on the health of the adjacent tissues [

1,

2]. The constant evolution in the field of implant dentistry has provided significant advances in the development of new designs of dental implants, especially with changes in their macrogeometry [

3]. As demonstrated in previous studies, the different macrogeometries of implants can bring different responses in the osseointegration process [

4]. These changes can be divided into 3 areas of the implant: cervical, body and apical. Among the changes proposed in each area, in the body of the implant we most frequently have new coil designs, in the apical portion the modifications are related to the cutting power and threading of the implant and, in the cervical portion, maintaining the stability of the peri-implant tissues is the main objective. This specific region of the implant (cervical) challenges conventional standards by exploring new configurations that aim to optimize both osseointegration and the aesthetic and functional integration of implants [

5].

The stability and maintenance of the health of the peri-implant tissues around the cervical portion (neck) of the implant represent primary objectives in the contemporary practice of implant dentistry [

6]. The integrity of the soft and bone tissues in this region not only directly influences the aesthetics and functional comfort of patients but is also crucial for the longevity and success of dental implant treatments [

6]. The cervical portion of the implant challenges professionals in the field to constantly seek new approaches and technologies that promote robust osseointegration and healthy adaptation of gingival tissues [

1]. The evolution of implant designs has been guided by studies that highlight the importance of characteristics such as shape, surface texture and biomechanical adjustments that minimize the impact on surrounding tissues [

7].

Several studies address the design of the implant neck and its relationship with marginal bone loss, but the results are varied in the literature [

8]. Studies in human showed that dental implants with triangular neck designs suggest better crestal bone preservation [

9]. Extra-short implants with a narrow ring demonstrated less bone loss at the crest, although with similar peri-implant tissue thickness [

10]. On the other hand, implants with micro-threads in the neck showed greater bone loss compared to implants with open-thread collars [

11]. Authors have indicated superior biomechanical behavior with dental implants that have a divergent neck design, favoring a more efficient stress/strain distribution, in comparison to straight and convergent crest module in ascending order of stress distribution [

12]. Furthermore, non-submerged implants with short, smooth collars did not show significant additional bone loss compared to similar but longer collar designs [

13].

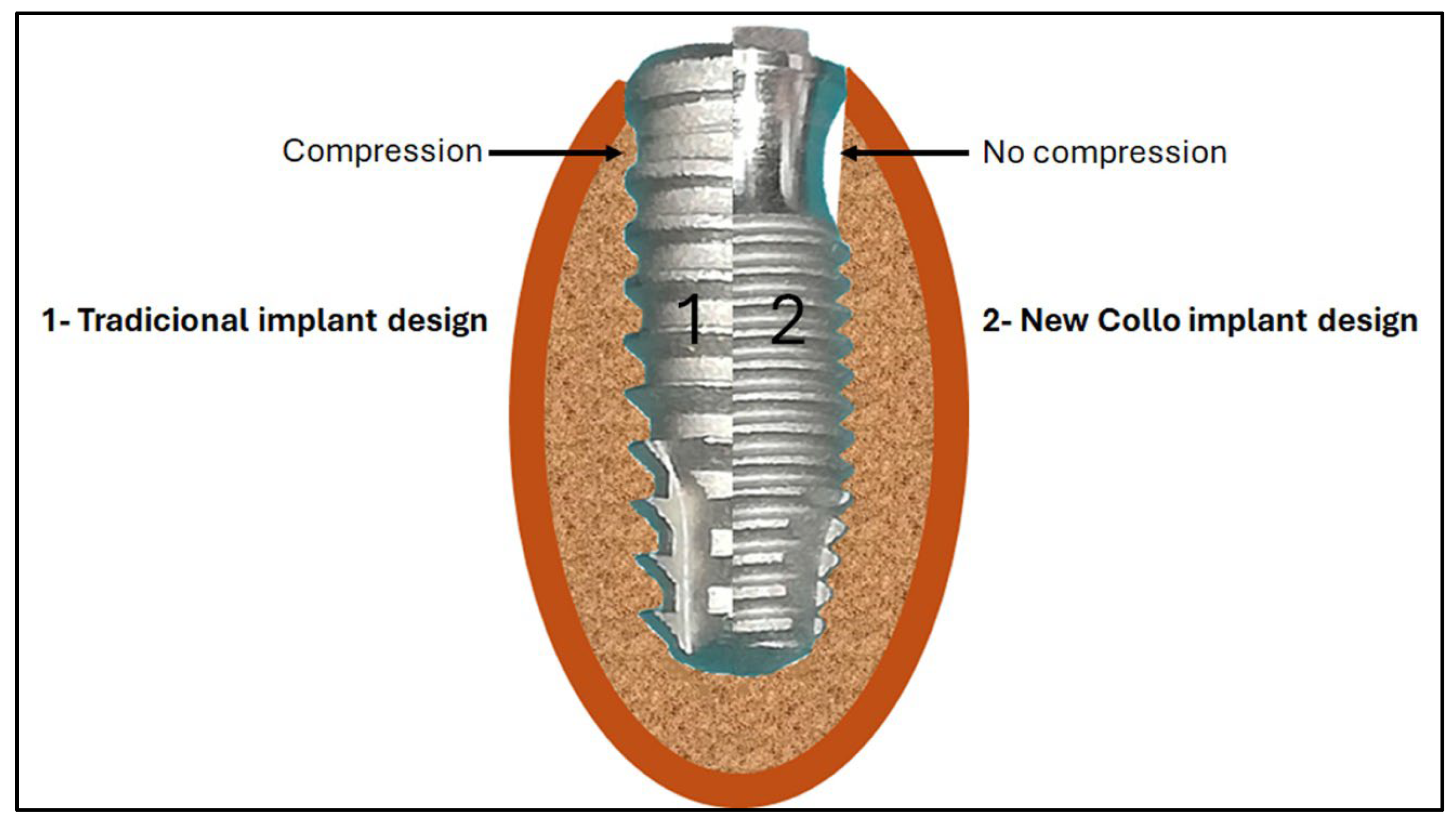

Recently, a new cervical macrogeometry design was developed as a promising alternative to traditional models [

14]. This new design not only aims to facilitate the formation and maintenance of peri-implant tissues, through carefully designed modifications, such as the introduction of a concave area in the cervical portion, and this new approach aims to promote more effective osseointegration and a biological response optimized. This new design generates a clot chamber in the cervical portion of the implant without causing compression in this area when compared to conventional implant designs (

Figure 1).

Therefore, this preclinical study, using rabbits as an experimental model, investigated a new implant design that incorporates specific changes in the cervical portion, using a conventional implant design as a control group. The main objectives of this experimental study were: (i) to evaluate the stability behavior of this new implant; (ii) evaluate the bone response in the concave area of the implant where the formation of a healing chamber occurs; (iii) analyze and compare the characteristics of the newly formed tissue in the initial stages of healing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Implants and Groups Formation

A total of 40 implants were used in this study. These samples were divided into two groups (n = 20 per group):

Collo group, where implants with a new cervical design were used, which present a concavity (reduction in diameter) in the first 3.5 mm and with this portion of the implant without surface treatment;

Control group, where conical implants with conventional design were used, which feature surface treatment throughout the body. Both implants were manufactured by the company Implacil De Bortoli (São Paulo, Brazil), with dimensions of 4 mm in diameter and 10 mm in length. The surface treatment presented by all implants of both groups was blasting with titanium oxide and subsequent acid etching [

15].

Figure 2 presents representative images of the implant models.

2.2. Animal Model and Care

In the present study, 10 adult rabbits weighing between 4 and 5 kg were used. Initially, the study protocol was analyzed and approved by the animal ethics committee of the University of Rio Verde – UnRV (Rio Verde, Brazil), under number 02-17/UnRV. The rabbit animal model represents a testing system commonly used in orthopedics as it is a model that presents adequate cost for acquisition, ease of handling and care, availability, tolerance to captivity and convenience of housing [

16]. Both tibias were selected as the site for installing the implants due to the simplicity of the surgical access and their anatomical characteristics (proportion of cortical and medullary bone). As in previous studies, international guidelines for animal studies were followed, where animals received a care and handling protocol [

17]. The present experiment was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and the ARRIVE guidelines were followed. All animals were kept in individual cages, with 12 hours of light and food and water

ad libitium throughout the experiment.

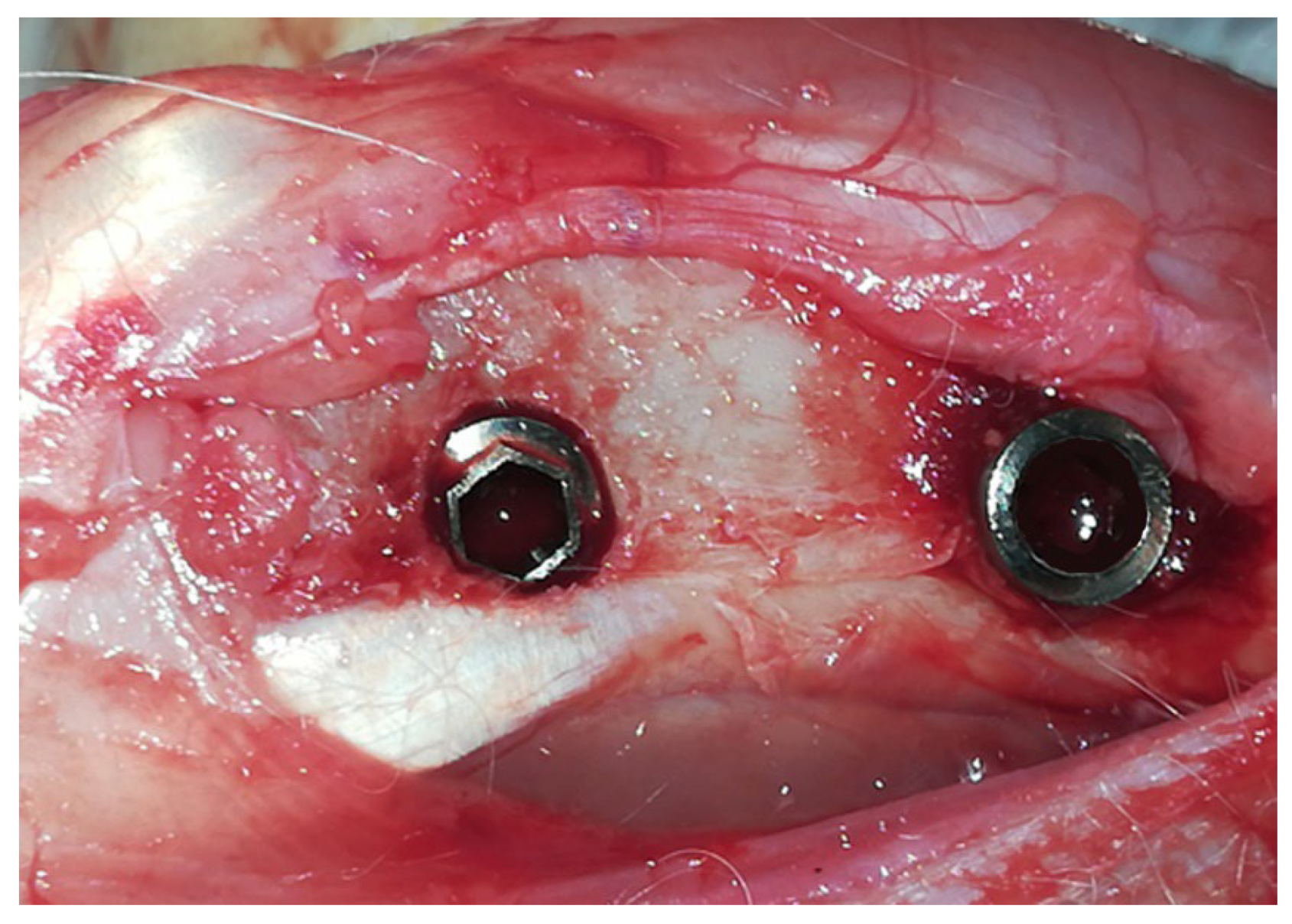

2.3. Implant Surgery and Distribution

Two implants were installed per tibia in each animal, in a proximal site (approximately 1 cm away from the joint) and another approximately 1 cm distally, as shown schematically in

Figure 3.

These implant installation positions were determined to reduce possible differences in the anatomical characteristics of the bone (amount of medullary and cortical bone), as in this area the tibia has a greater amount of medullary bone and less cortical bone [

4]. The distribution was determined using free software (available at

www.randomizer.org).

All animals were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of 0.35 mg/kg of ketamine (Ketamina Agener®; Agener União Ltd.a., São Paulo, Brazil) and 0.5 mg/kg of xylazine (Rompum® Bayer S.A., São Paulo, Brazil). Initially, a total incision was made from the proximal joint towards the distal of approximately 4 cm. Afterwards, the bone tissue was exposed, and drilling was carried out using the drill sequence and speed recommended by the manufacturer for each implant design, under intense irrigation with physiological solution. The implants were installed manually using a surgical torque wrench with an approximate torque of 15 Ncm. Finally, the tissues were sutured with a single stitch using a nylon suture (Ethicon 3-0, Johnson & Johnson Medical, New Brunswick, USA). To control postoperative infection, a single intramuscular dose of 0.1 ml/kg of Benzetacil (Bayer, São Paulo, Brazil) was injected. While controlling pain and inflammation, three doses (one per day) of 3 mg/kg of ketoprofen (Ketoflex, Mundo Animal, São Paulo, Brazil) were administered. After a period of 3 and 4 weeks, the animals were sacrificed using an overdose of anesthetics (n = 5 animals per time). Then, both tibias of each animal were removed and duly identified, and these samples were immediately immersed in a 4% formaldehyde solution, where they remained for 7 days to begin the treatment sequence for inclusion in resin.

2.4. Implant Stability Quotient (ISQ) Measurement

Immediately after installation of each implant, a magnetic sensor (SmartPeg, Gothenburg, Sweden) was threaded and manually tightened to measure initial stability: sensor type 49 for Control group and, sensor type 1 for Collo group. These measurements were carried out using the Osstell device (Osstell AB, Gothenburg, Sweden), which indicates a value from 0 to 100 determining the implant stability quotient (ISQ). For each sample, measurements were taken in two directions (proximo-distal and antero-posterior), generating an average between these values. The ISQ was measured at three times for each sample, that is, immediately after installing the implants (Time 1) and immediately after removing the samples (Times 2 and 3).

2.5. Histological Preparation and Measurements

After 7 days of fixing the samples in formaldehyde solution, they were subjected to a sequence of alcohol in progressive concentrations (50-100%), for a period of 72 hours at each concentration, for dehydration. Then, all samples were embedded in historesin Technovit 7200 VLC (Kultzer & Co, Wehrhein, Germany) and polymerized. These historesin blocks containing the samples (bone and implants) were subjected to cutting in the central portion of each implant in a metallographic machine (Isomet 1000; Buehler, Germany), being subsequently fixed on the blades and sanded on a bench polisher (Polipan- U, Panambra Zwick, São Paulo, Brazil) using an abrasive paper sequence (180, 320, 600, 1000, and 1200 mesh). To stain the slides, these slides were rehydrated using a decreasing sequence of alcohol (100–50%), plus a 100% ethanol solution and hydrogen peroxide 10 vol in a 50:50 ratio. Then, all sample slices were stained by Picrosirius red-hematoxylin. Image series were acquired using light optical microscopy (Nykon E200, Tokyo, Japan).

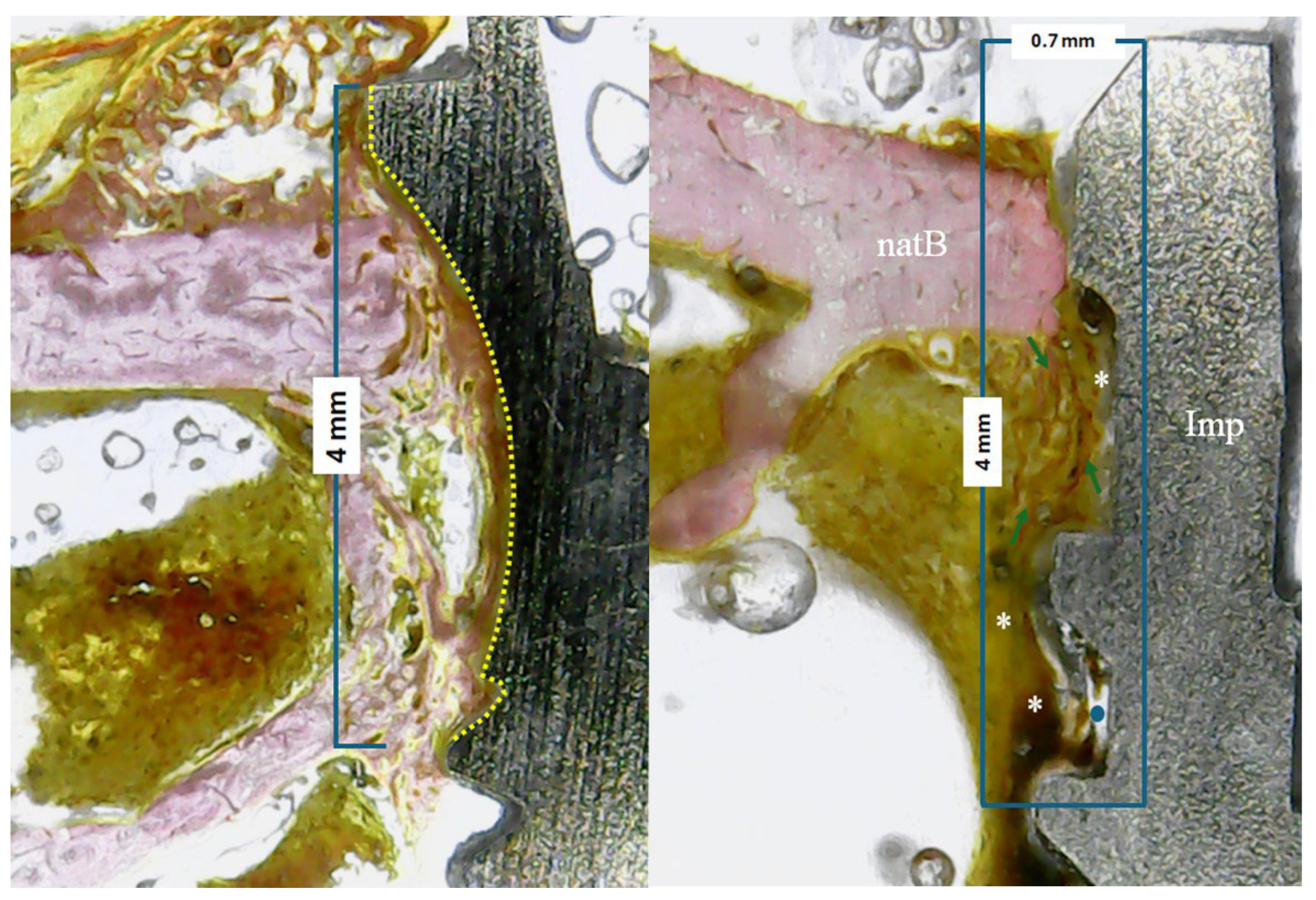

In all samples, the percentage of bone–implant contact (BIC%) parameters were evaluated within 4 mm from the implant platform in the apical direction, as shown schematically in

Figure 4a. Furthermore, in an area of 4 mm (from the implant platform towards the apical direction) by 0.7 mm (from the implant platform towards the native bone) the tissue area fraction occupancy (TAFO%) with anatomical characteristics of the newly formed tissue were evaluated, i.e., amount of newly formed bone, collagen matrix and medullary spaces present (

Figure 4b). For both evaluations and measurements, ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, USA) was used.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

No adverse events were observed during the healing period, such as inflammation and/or infection in the surgery area. All implants showed clinical stability at the percussion test, and radiographic signs of osseointegration during the predetermined evaluation period (3 and 4 weeks).

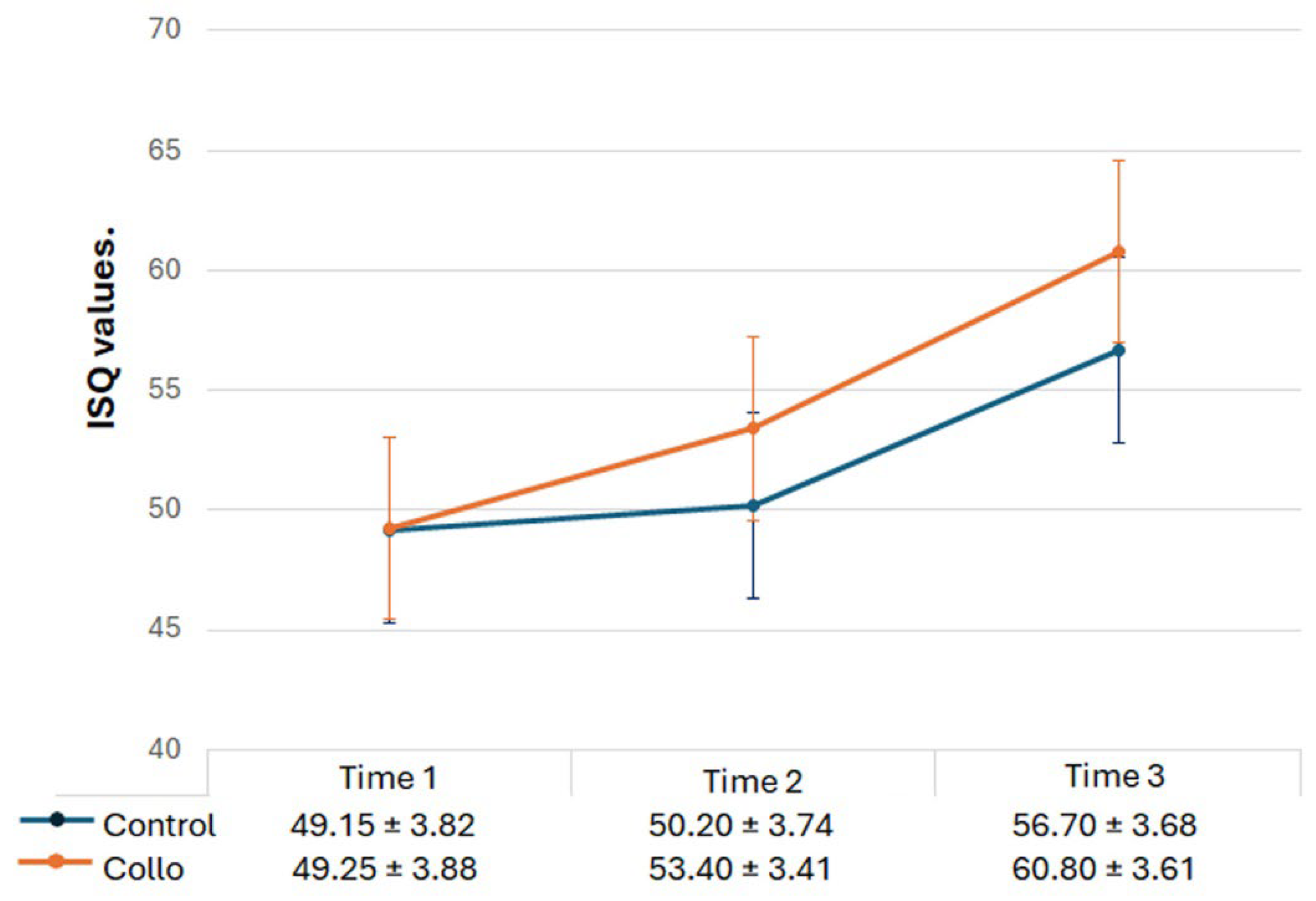

3.1. Implant Stability Quotient (ISQ) Results

The implant stability measured using Osstell

® in the three evaluation periods is shown comparatively in

Figure 5. Statistically, there were differences between the 3 times analyzed in both groups (ANOVA intragroup): for Control group p = 0.0003, and for Collo group p = < 0.0001. Intergroup (t-test), no statical differences were detected between the groups at Time 1 (p = 0.9458), and Time 2 (p = 0.1103). However, in the Time 3 p = 0.0475, showing statistical differences between the groups.

3.2. Histological Results

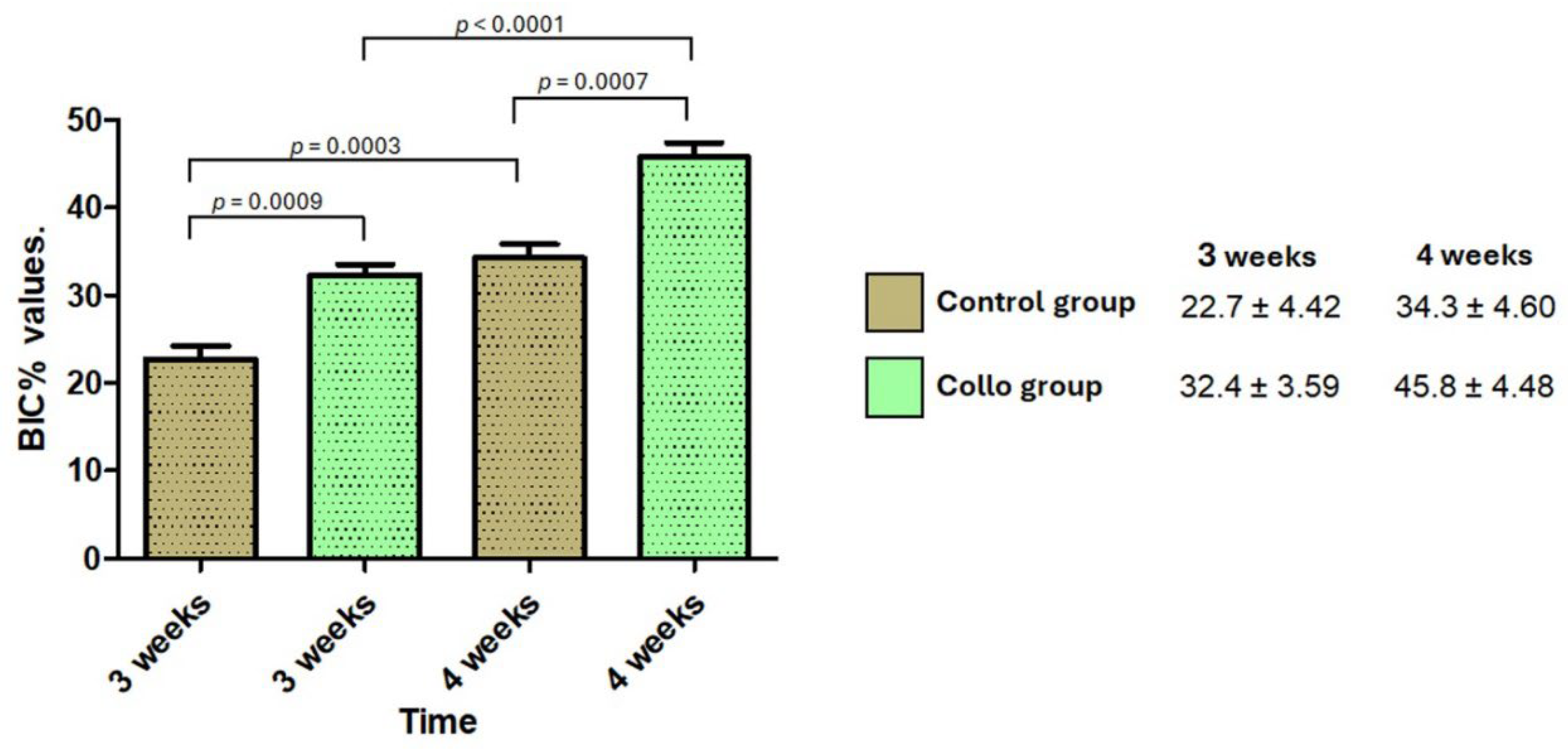

Higher BIC% values were presented in samples from the Collo group than in the Control group at both times. The data obtained (mean and standard deviation) and the statistical comparison calculated are graphically presented in

Figure 6.

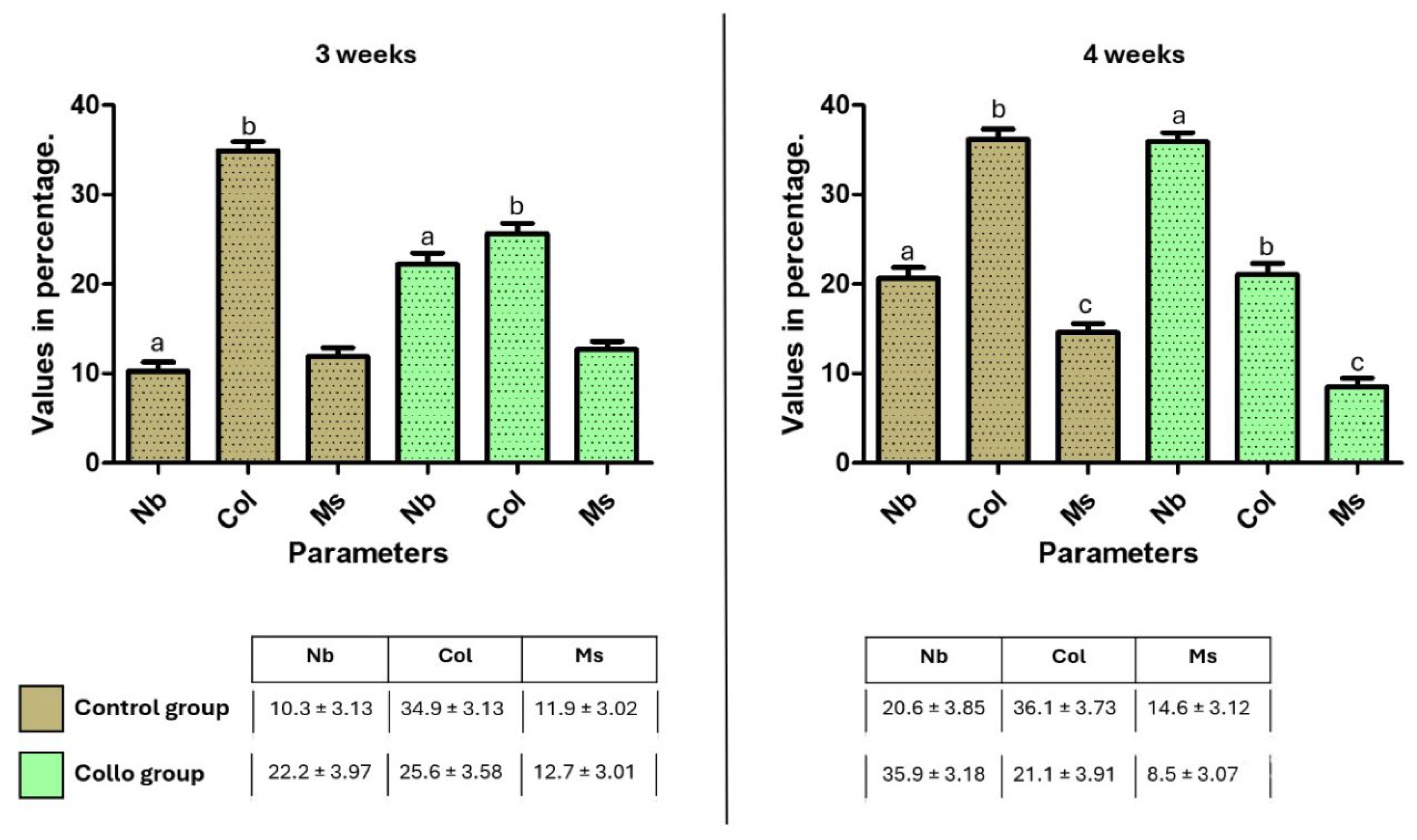

Figure 7 presented the mean and standard deviation of TAFO% values of the rectangle area in the cervical position, where the predetermined parameters were measured (new bone, collagen matrix, and medullary spaces). The statistical differences between the groups of the same parameters at each evaluation time are shown in the graph bar (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The present study presents a comparative analysis between a new implant design with changes in the cervical portion (Collo group) and a conventional implant (Control group), focusing on the initial stages of osseointegration in a pre-clinical trial. The main parameters evaluated were the initial stability of the implants (measured by ISQ) at the time of installation, in addition to stability at 3 and 4 weeks after installation. Additionally, histological analyzes were performed to evaluate the proportion of bone-implant contact (BIC%) and the tissue area fraction occupancy (TAFO%) of the predetermined cervical portion (initial 4 mm from the platform). The results revealed that the Collo group presented higher stability values (ISQ) both at the time of installation and in subsequent measurements after 3 and 4 weeks, compared to the Control group. Furthermore, histological evaluations demonstrated that the Collo group had a higher proportion of bone-implant contact (BIC%) and a higher rate of new bone formation (TAFO%) at both times analyzed. These findings are consistent with previous studies that suggest that macrogeometric changes in implants can exert a significant influence on the osseointegration process [

4,

15]. Furthermore, other studies have shown that changes in the macrogeometry and shapes of the external threads of dental implants are still topics that are widely explored in the literature [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Several studies on macrogeometric changes carried out focused on animal models, and most of them explored the biological mechanisms involved in the healing process with different surface treatments and macrogeometries [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The macrogeometry of implants is one of the factors that has the greatest influence on the primary stability of implants, on the initial torque and, consequently, promotes optimization of osseointegration [

26]. The observation of positive results in tissue neoformation around the cervical portion of the implants in the Collo group in comparison with the Control group corroborates the results of other studies showing that the proposed change in the macrogeometry of the implants can have a significant impact on the osseointegration process [

4,

15,

26]. Specifically, the more accelerated formation of peri-implant tissues was highlighted, attributed to the presence of an area of bone non-compression due to the formation of a healing chamber, as shown in

Figure 1. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that the presence of clot chambers in dental implants can optimize osseointegration [

4,

15,

22,

28]. These chambers promote an environment conducive to cell differentiation and tissue neoformation around the implant, which are essential for successful long-term osseointegration. Other studies have shown that in conjunction with appropriate surface treatments and adequate macrogeometry, it can accelerate healing and promote more effective osseointegration [

27,

28].

On the other hand, the bone portion in contact with the cervical area of the implant is characterized by the presence of cortical bone, which is directly related to the initial stability of the implants [

29,

30]. However, the cortical bone tissue presents anatomical characteristics with little vascularization compared to the medullary bone portion. Therefore, compression of this area (cortical) can cause unwanted effects, such as ischemia, necrosis and bone resorption [

31,

32]. Mosavar et al. [

33] suggested that dense cortical bone, especially the bone adjacent to the first thread, experiences the maximum strain upon insertion and bears maximum compressive force and shear stresses. Thus, the new macrogeometry of Collo implants, forming a compression-free area on the cortical bone tissue, appears to be effective for healing events based on the results obtained.

Regarding stability measured through resonance frequency analysis using Osstell, which is an effective and non-invasive method [

34], the initial values were similar for both groups, with no statistical difference between them. These findings demonstrate that the presence of the healing chamber, provided by the cervical design of the Collo group implants, did not reduce the initial ISQ values, as the final part of the implant platform (0.5 mm) is anchored in the cortical bone. In this sense, as demonstrated by other authors, contact with the cervical portion of the implant with the cortical bone favors initial stability [

30]. At other predetermined times for measurements (3 and 4 weeks after the implantations), the values were higher for the Collo group compared to the Control group, corroborating findings from other studies that related changes in macrogeometry with the ISQ values obtained [

4,

15].

Another factor that macrogeometry is capable of influencing is the biomechanics and distribution of chewing loads [

35]. However, studies have shown that primary stability may not be directly related to insertion torque [

36]. Therefore, some authors question the correlation of high insertion torque with high rates of clinical success of dental implants [

37], as it can result in high tension in the peri-implant region and, consequently, can provoke negative responses both biological and secondary stability. Therefore, macrogeometry stands out as one of the factors capable of directly interfering in the osseointegration of dental implants, enabling a reduction in loading time [

4,

15,

38].

Finaly, it is important to highlight that this study is a preclinical trial, and results observed under controlled conditions may vary in a real clinical setting, where additional factors such as individual patient characteristics, oral health conditions and implantation techniques may influence the results. Furthermore, it is essential to consider that this study was conducted in a controlled preclinical environment, and results may vary in real clinical conditions, where factors such as individual patient characteristics and implant installation techniques may influence results. Subsequent clinical studies are needed to confirm the applicability of these findings in everyday dental practice and to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of this new implant design.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of the present pre-clinical study, the results of this study suggest that the new implant design with changes in the cervical portion (Collo group) presents significant advantages in relation to the conventional implant (Control group), regarding stability in the initial times and osseointegration. Subsequent clinical studies are needed to validate these findings and verify their large-scale clinical applicability.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Approval

The present study was approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee (Number 02-17UnRV), University of Rio Verde (Rio Verde, Brazil). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Marco Aurélio Bianchini and Piedad De Aza; Data curation, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Guillermo Cortellari, Marco Aurélio Bianchini, Antonio Scarano and Piedad De Aza; Formal analysis, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke and Marco Aurélio Bianchini; Investigation, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Guillermo Cortellari, Jaime Aramburú Júnior and Tiago Luis Eirles Treichel; Methodology, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Guillermo Cortellari, Jaime Aramburú Júnior, Tiago Luis Eirles Treichel and Antonio Scarano; Validation, Piedad De Aza; Writing – original draft, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Jaime Aramburú Júnior and Tiago Luis Eirles Treichel; Writing – review & editing, Sergio Alexandre Gehrke, Antonio Scarano and Piedad De Aza.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation—Grant PID2020-116693RB-C21, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis; the decision to publish; or the manuscript preparation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are contained within the paper.

Acknowledgments

The author Sergio Alexandre Gehrke was funded by post-doctoral grant No. 2021/PER/00020 from the Ministerio de Universidades under the program “Ayudas para la recualificación del sistema universitario español de la Universidad Miguel Hernandez” modalidad “Margarita Salas para la formación de jóvenes doctores”.

References

- Perussolo J, Donos N. Maintenance of peri-implant health in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2024;236(10):781-789. [CrossRef]

- Sartoretto SC, Shibli JA, Javid K, Cotrim K, Canabarro A, Louro RS, Lowenstein A, Mourão CF, Moraschini V. Comparing the Long-Term Success Rates of Tooth Preservation and Dental Implants: A Critical Review. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14(3):142. [CrossRef]

- Naves MM, Menezes HH, Magalhães D, Ferreira JA, Ribeiro SF, de Mello JD, Costa HL. Effect of Macrogeometry on the Surface Topography of Dental Implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30(4):789-99. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke SA, Júnior JA, Eirles Treichel TL, Dedavid BA. Biomechanical and histological evaluation of four different implant macrogeometries in the early osseointegration process: An in vivo animal study. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2022;125:104935. [CrossRef]

- Monje A, González-Martín O, Ávila-Ortiz G. Impact of peri-implant soft tissue characteristics on health and esthetics. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023;35(1):183-196. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz F, Ramanauskaite A. It is all about peri-implant tissue health. Periodontol 2000. 2022;88(1):9-12. [CrossRef]

- Robau-Porrua A, González JE, Rodríguez-Guerra J, González-Mederos P, Navarro P, de la Rosa JE, Carbonell-González M, Araneda-Hernández E, Torres Y. Biomechanical Behavior of a New Design of Dental Implant: Influence of the Porosity and Location in the Maxilla. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;29:3255–3267.

- Montemezzi P, Ferrini F, Pantaleo G, Gherlone E, Capparè P. Dental Implants with Different Neck Design: A Prospective Clinical Comparative Study with 2-Year Follow-Up. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(5):1029. [CrossRef]

- Tokuc B, Kan B. The effect of triangular cross-section neck design on crestal bone stability in the anterior mandible: A retrospective study with a 5-year follow-up. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2023;34(11):1309-1317. [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Guirado JL, Morales-Meléndez H, Pérez-Albacete Martínez C, Morales-Schwarz D, Kolerman R, Fernández-Domínguez M, Gehrke SA, Maté-Sánchez de Val JE. Evaluation of the Surrounding Ring of Two Different Extra-Short Implant Designs in Crestal Bone Maintanence: A Histologic Study in Dogs. Materials (Basel). 2018;11(9):1630. [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Guirado JL, Jiménez-Soto R, Pérez Albacete-Martínez C, Fernández-Domínguez M, Gehrke SA, Maté-Sánchez de Val JE. Influence of Implant Neck Design on Peri-Implant Tissue Dimensions: A Comparative Study in Dogs. Materials (Basel). 2018;11(10):2007. [CrossRef]

- Patil SM, Deshpande AS, Bhalerao RR, Metkari SB, Patil PM. A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the influence of varying implant crest module designs on the stress distribution to the bone. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2019;16(3):145-152.

- Hanggi, M.P.; Hanggi, D.C.; Schoolfield, J.D.; Meyer, J.; Cochran, D.L.; Hermann, J.S. Crestal bone changes around titanium implants. Part I: A retrospective radiographics evaluation in humans comparing two non-submerged implant designs with different machined collar lengths. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 791–802.

- Bianchini MA, Junior NB, Dedavid BA, De Aza PN, Gehrke SA. Comparative analysis of the mechanical limits of resistance in implant/abutment set of a new implant design: An in vitro study. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280684. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke SA, Tumedei M, Aramburú Júnior J, Treichel TLE, Kolerman R, Lepore S, Piattelli A, Iezzi G. Histological and Histomorphometrical Evaluation of a New Implant Macrogeometry. A Sheep Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3477. [CrossRef]

- Scarano A, Khater AGA, Gehrke SA, Inchingolo F, Tari SR. Animal Models for Investigating Osseointegration: An Overview of Implant Research over the Last Three Decades. J Funct Biomater. 2024;15(4):83. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke SA, Bettach R, Aramburú Júnior JS, Prados-Frutos JC, Del Fabbro M, Shibli JA. Peri-Implant Bone Behavior after Single Drill versus Multiple Sequence for Osteotomy Drill. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9756043. [CrossRef]

- Trisi P, Berardini M, Falco A, Podaliri Vulpiani M. Effect of Implant Thread Geometry on Secondary Stability, Bone Density, and Bone-to-Implant Contact: A Biomechanical and Histological Analysis. Implant Dent. 2015;24(4):384-91. [CrossRef]

- Falco A, Berardini M, Trisi P. Correlation Between Implant Geometry, Implant Surface, Insertion Torque, and Primary Stability: In Vitro Biomechanical Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018;33(4):824-830. [CrossRef]

- Muktadar AK, Gangaiah M, Chrcanovic BR, Chowdhary R. Evaluation of the effect of self-cutting and nonself-cutting thread designed implant with different thread depth on variable insertion torques: An histomorphometric analysis in rabbits. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20(4):507-514. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tarawneh SK, Thalji G, Cooper LF. Macrogeometric Differentiation of Dental Implant Primary Stability: An In Vitro Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2022;37(6):1110-1118. [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna HR, Casati MZ, Mussi MC, Cirano FR, Pimentel SP, Ribeiro FV, Corrêa MG. Peri-Implant Repair Using a Modified Implant Macrogeometry in Diabetic Rats: Biomechanical and Molecular Analyses of Bone-Related Markers. Materials (Basel). 2022 1;15(6):2317. [CrossRef]

- Mussi MC, Ribeiro FV, Corrêa MG, Salmon CR, Pimentel SP, Cirano FR, Casati MZ. Impact of a modified implant macrogeometry on biomechanical parameters and bone-related markers in rats. Braz Oral Res. 2023;37:e44. [CrossRef]

- Bergamo ETP, de Oliveira PGFP, Jimbo R, Neiva R, Gil LF, Tovar N, Witek L, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG. The Influence of Implant Design Features on the Bone Healing Pathway: An Experimental Study in Sheep. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2023;43(3):337-343. [CrossRef]

- Benalcázar-Jalkh EB, Nayak VV, Gory C, Marquez-Guzman A, Bergamo ET, Tovar N, Coelho PG, Bonfante EA, Witek L. Impact of implant thread design on insertion torque and osseointegration: a preclinical model. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2023;28(1):e48-e55. [CrossRef]

- Heimes D, Becker P, Pabst A, Smeets R, Kraus A, Hartmann A, Sagheb K, Kämmerer PW. How does dental implant macrogeometry affect primary implant stability? A narrative review. Int J Implant Dent. 2023;9(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Bergamo ETP, de Oliveira PGFP, Jimbo R, Neiva R, Tovar N, Witek L, Gil LF, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG. Synergistic Effects of Implant Macrogeometry and Surface Physicochemical Modifications on Osseointegration: An In Vivo Experimental Study in Sheep. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2019;29(4):295-302. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke SA, Dedavid BA, Aramburú JS Júnior, Pérez-Díaz L, Calvo Guirado JL, Canales PM, De Aza PN. Effect of Different Morphology of Titanium Surface on the Bone Healing in Defects Filled Only with Blood Clot: A New Animal Study Design. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4265474. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Miron RJ. Health, Maintenance, and Recovery of Soft Tissues around Implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2016;18(3):618-34. [CrossRef]

- Chávarri-Prado D, Brizuela-Velasco A, Diéguez-Pereira M, Pérez-Pevida E, Jiménez-Garrudo A, Viteri-Agustín I, Estrada-Martínez A, Montalbán-Vadillo O. Influence of cortical bone and implant design in the primary stability of dental implants measured by two different devices of resonance frequency analysis: An in vitro study. J Clin Exp Dent. 2020;12(3):e242-e248. [CrossRef]

- Bashutski JD, D’Silva NJ, Wang HL. Implant compression necrosis: current understanding and case report. J Periodontol. 2009;80(4):700-4. [CrossRef]

- Hansson S, Werke M. The implant thread as a retention element in cortical bone: the effect of thread size and thread profile: a finite element study. J Biomech. 2003;36(9):1247-58. [CrossRef]

- Mosavar A, Ziaei A, Kadkhodaei M. The effect of implant thread design on stress distribution in anisotropic bone with different osseointegration conditions: a finite element analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30(6):1317-26. [CrossRef]

- Bavetta G, Paderni C, Bavetta G, Randazzo V, Cavataio A, Seidita F, Khater AGA, Gehrke SA, Tari SR, Scarano A. ISQ for Assessing Implant Stability and Monitoring Healing: A Prospective Observational Comparison between Two Devices. Prosthesis. 2024; 6(2):357-371. [CrossRef]

- Valente MLDC, de Castro DT, Macedo AP, Shimano AC, Dos Reis AC. Comparative analysis of stress in a new proposal of dental implants. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;77:360-365. [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Arrieta G, Brizuela-Velasco A, Fernández-González FJ, Chávarri-Prado D, Chento-Valiente Y, Solaberrieta E, Diéguez-Pereira M, Vega JA, Yurrebaso-Asúa J. Biomechanical evaluation of oversized drilling technique on primary implant stability measured by insertion torque and resonance frequency analysis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8(3):e307-11. [CrossRef]

- Scarano A, Piattelli A, Assenza B, Sollazzo V, Lucchese A, Carinci F. Assessment of pain associated with insertion torque of dental implants. A prospective, randomized-controlled study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(2 Suppl):65-9. [CrossRef]

- Carmo Filho LCD, Marcello-Machado RM, Castilhos ED, Del Bel Cury AA, Faot F. Can implant surfaces affect implant stability during osseointegration? A randomized clinical trial. Braz Oral Res. 2018;32:e110. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).