Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

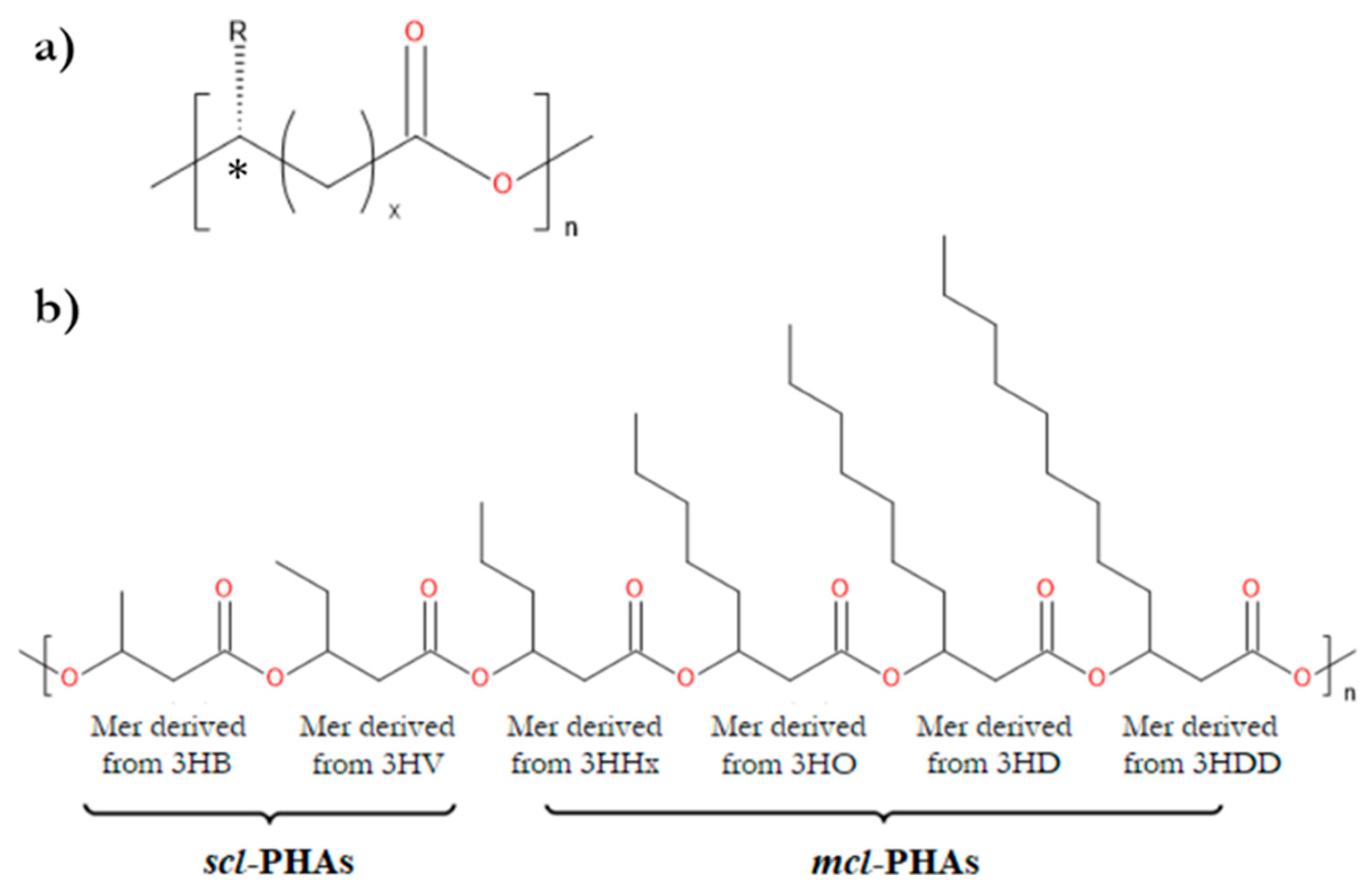

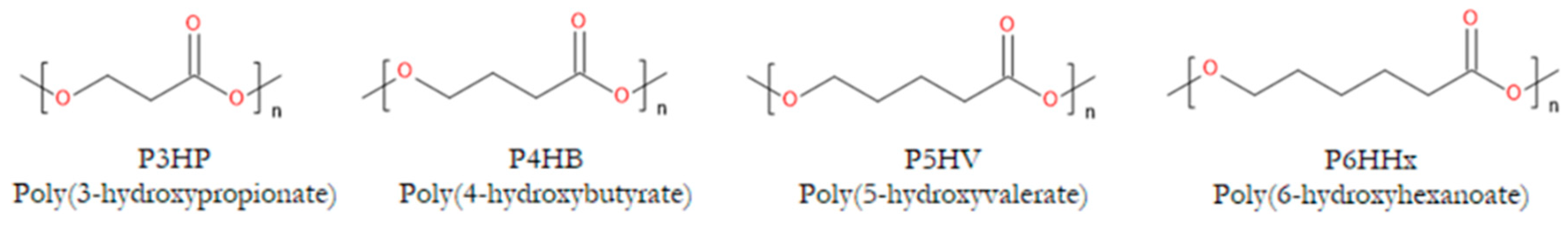

2. Properties of PHAs Important for Their Applications in Tissue Engineering

2.1. Mechanical Properties and Piezoelectricity

| Biopolyester | Tg [°C] | Tm [°C] | Xc [%] | E [GPa] | Rm [Mpa] | A [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHB | 5–10 | 173–180 | 60–80 | 3.5–4 | 20–40 | 3–8 |

| PHBV 3% | 8 | 170 | 59 | 2.9 | 38 | 5 |

| PHBV 9% | N/A | 162 | N/A | 1.9 | 37 | N/A |

| PHBV 14% | N/A | 150 | N/A | 1.5 | 35 | N/A |

| PHBV 20% | –1 | 145 | 56 | 1.2 | 32 | 50 |

| PHBV 25% | –6 | 137 | 54 | 0.7 | 30 | 100 |

| PHBHHx 10% | –1 | 127 | 35 | 0.23 | 21 | 400 |

| PHO | –38 | 49 | 25 | 0.017 | N/A | 300 |

| P4HB | –50 | 53 | < 40 | 149 | 104 | 1000 |

| P34HB 19–94% | –4–(–46) | 52–158 | 18–54 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| P34HB 3% | N/A | 166 | N/A | N/A | 28 | 45 |

| P34HB 10% | N/A | 159 | N/A | N/A | 24 | 242 |

| P34HB 16% | –7 | 130 | 43 | N/A | 26 | 444 |

| P34HB 64% | –35 | 50 | N/A | 30 | 17 | 591 |

| P34HB 90% | –42 | 50 | N/A | 100 | 65 | 1080 |

2.2. In Vivo Degradability

2.3. Biocompatibility

2.4. Cytocompatibility

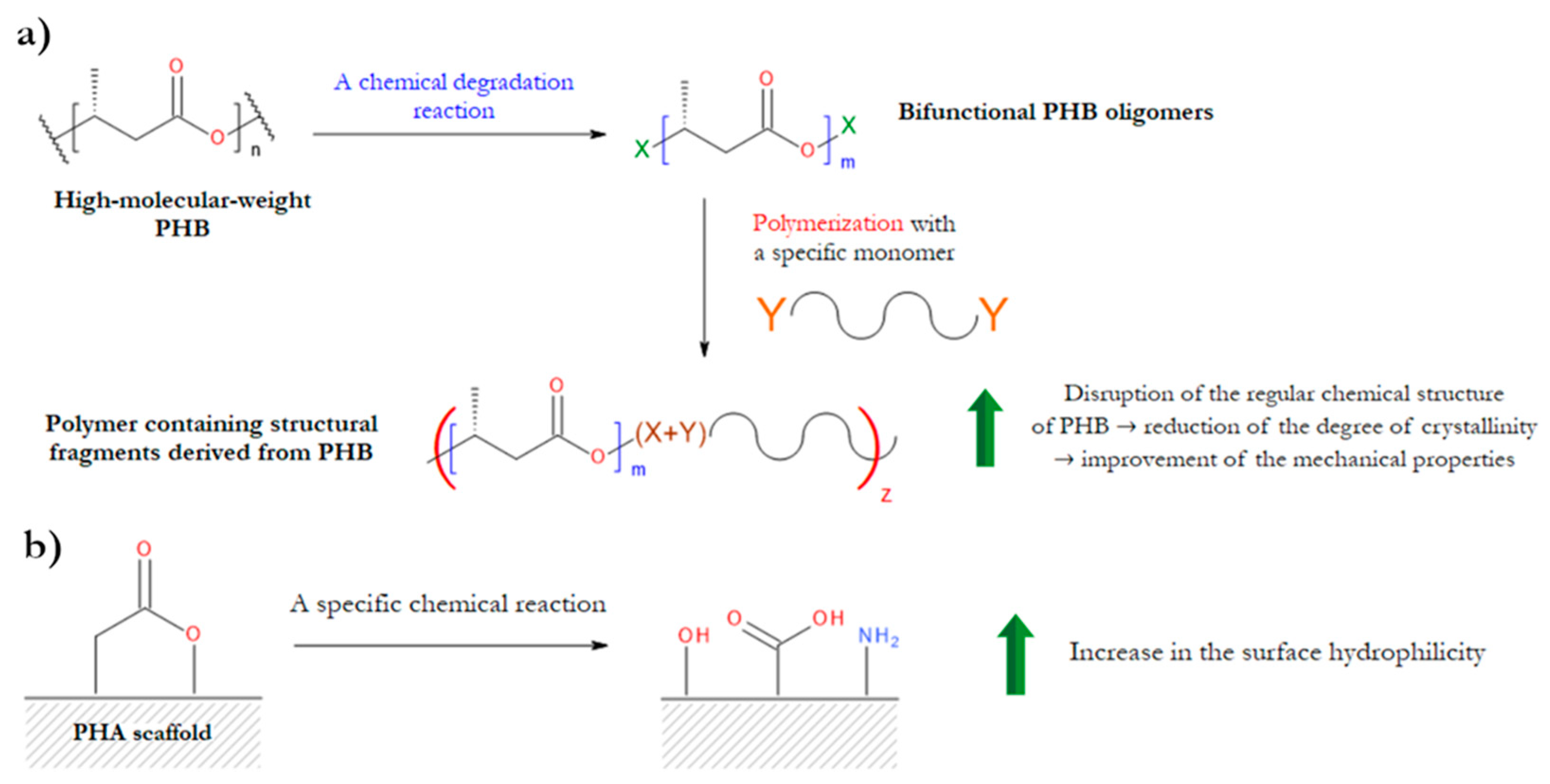

3. Chemical Modifications of PHAs

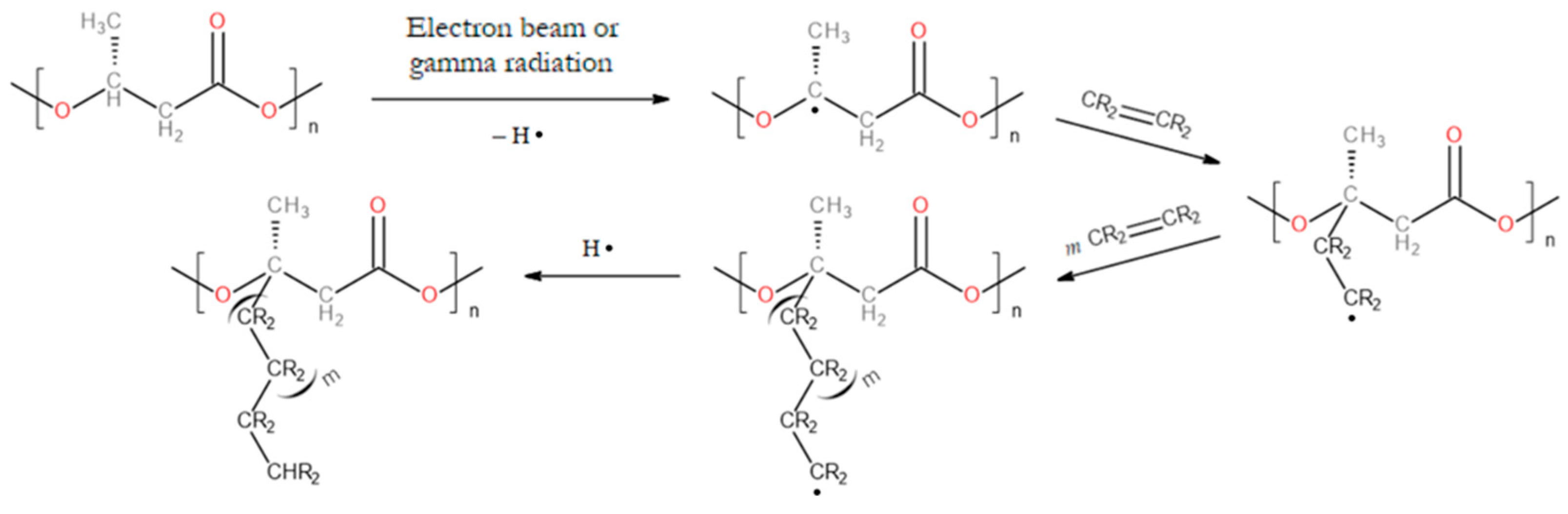

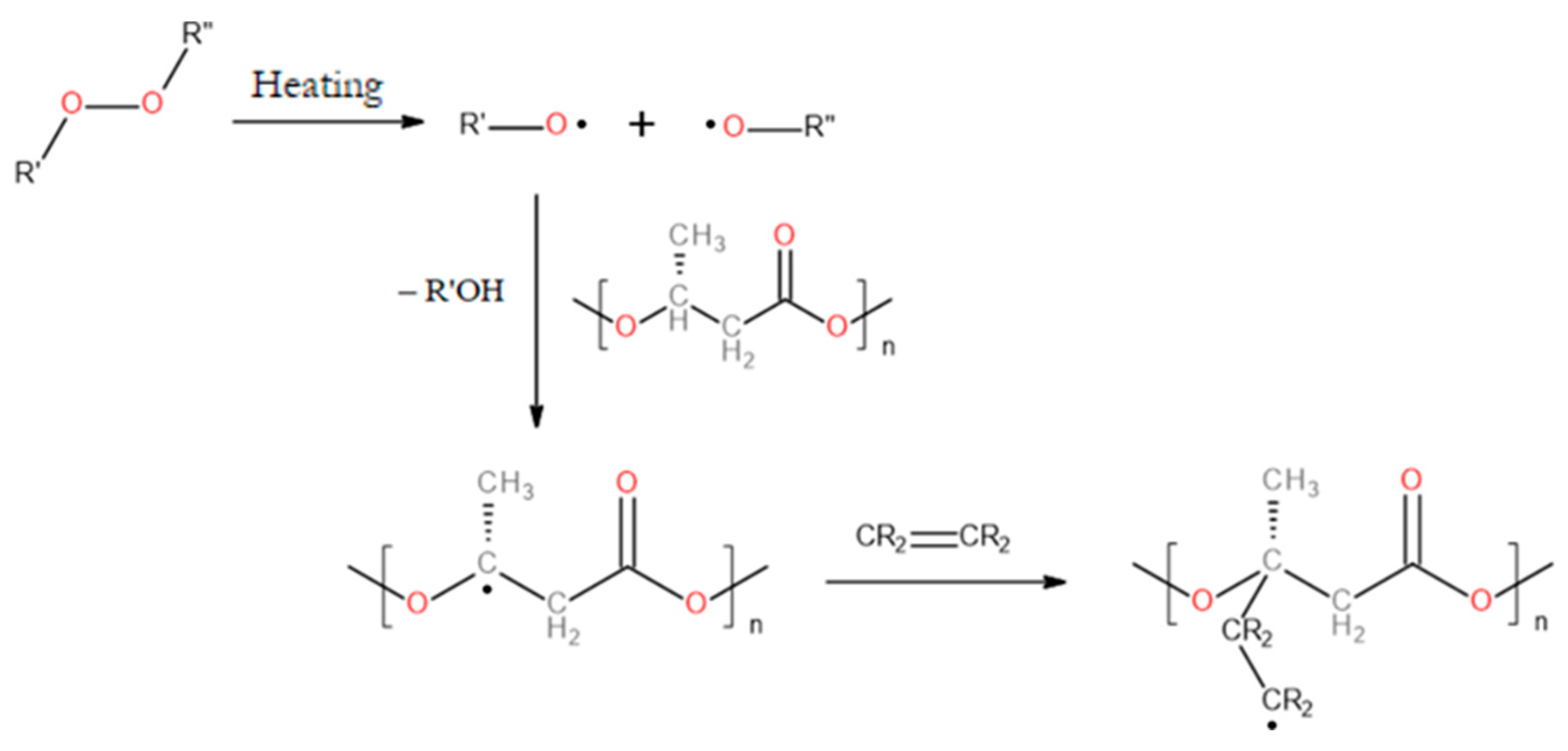

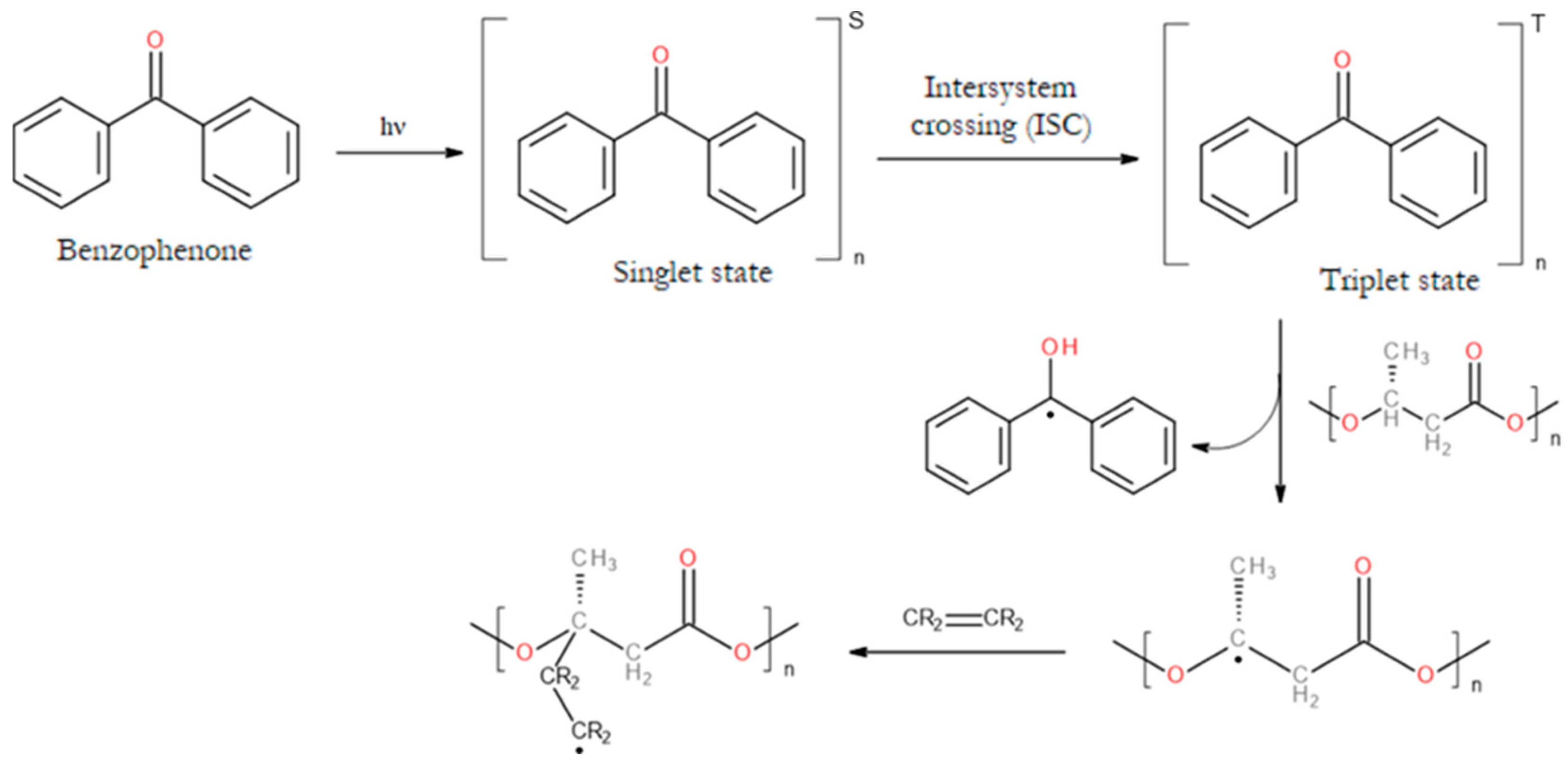

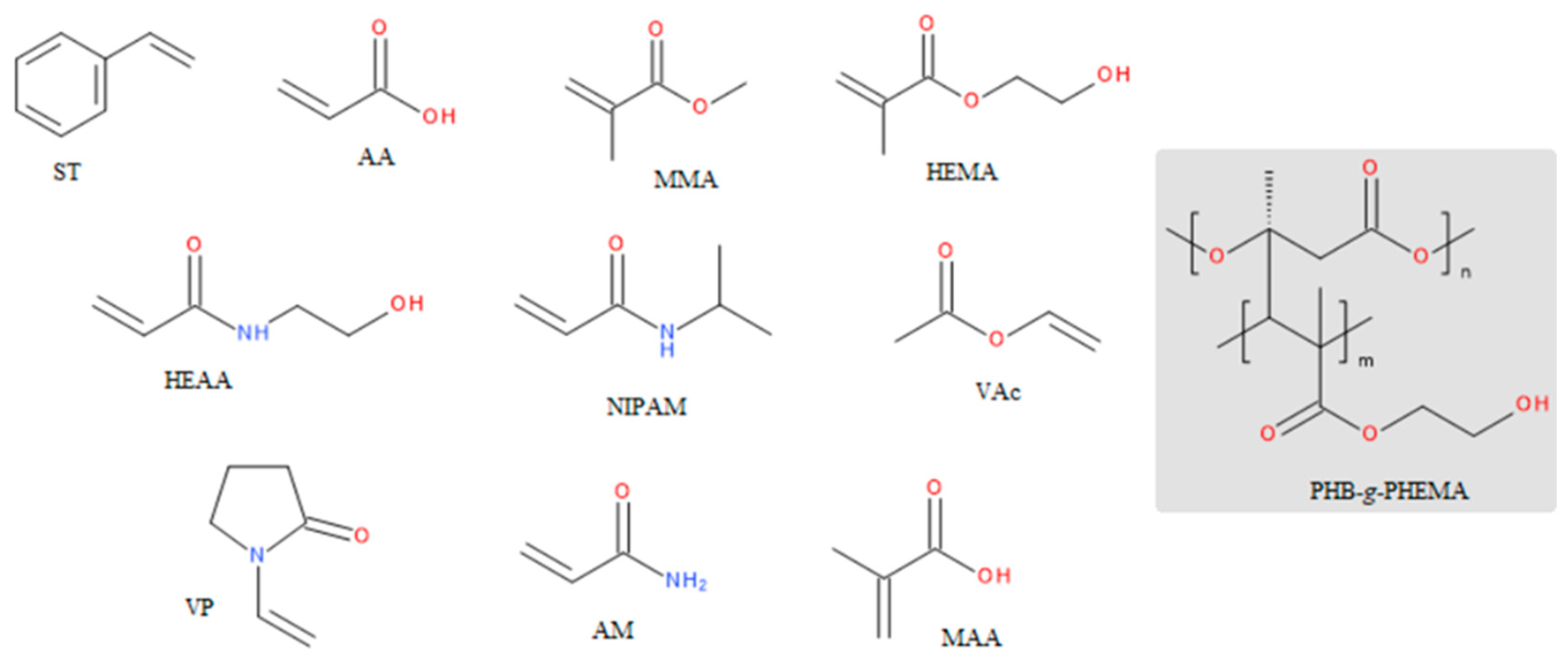

3.1. Graft Copolymers of PHAs

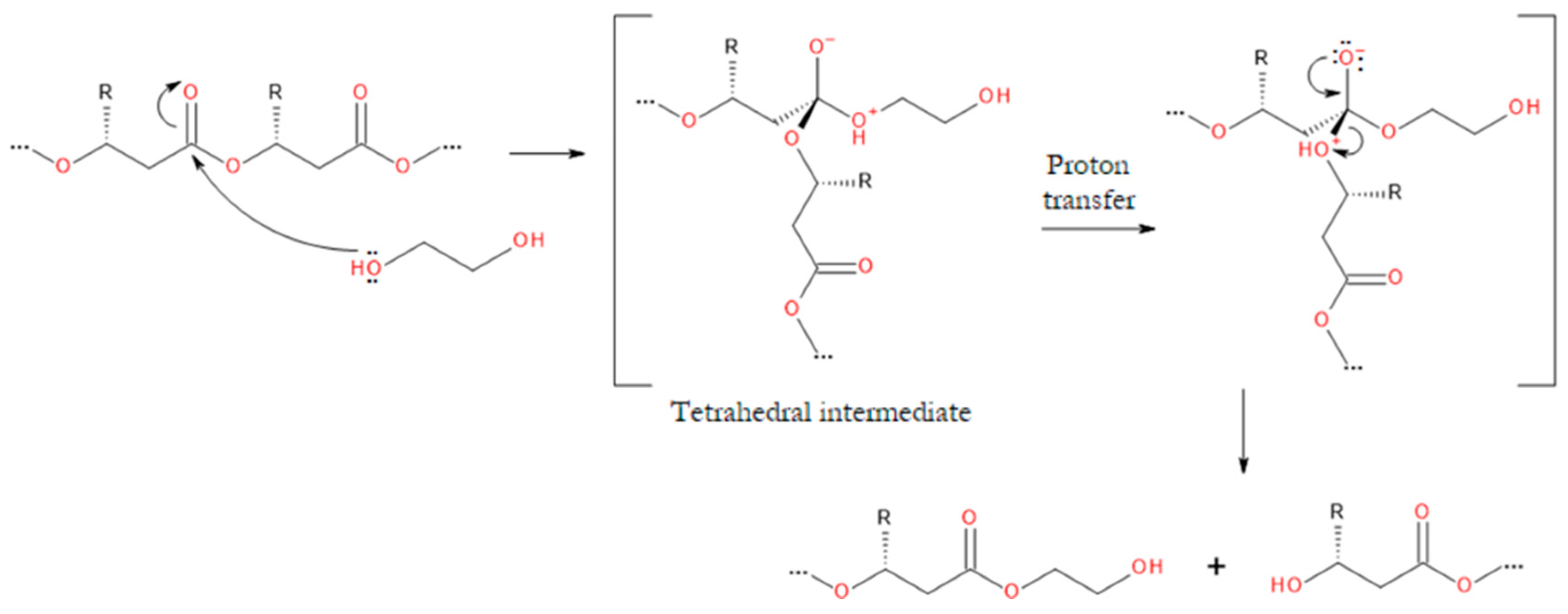

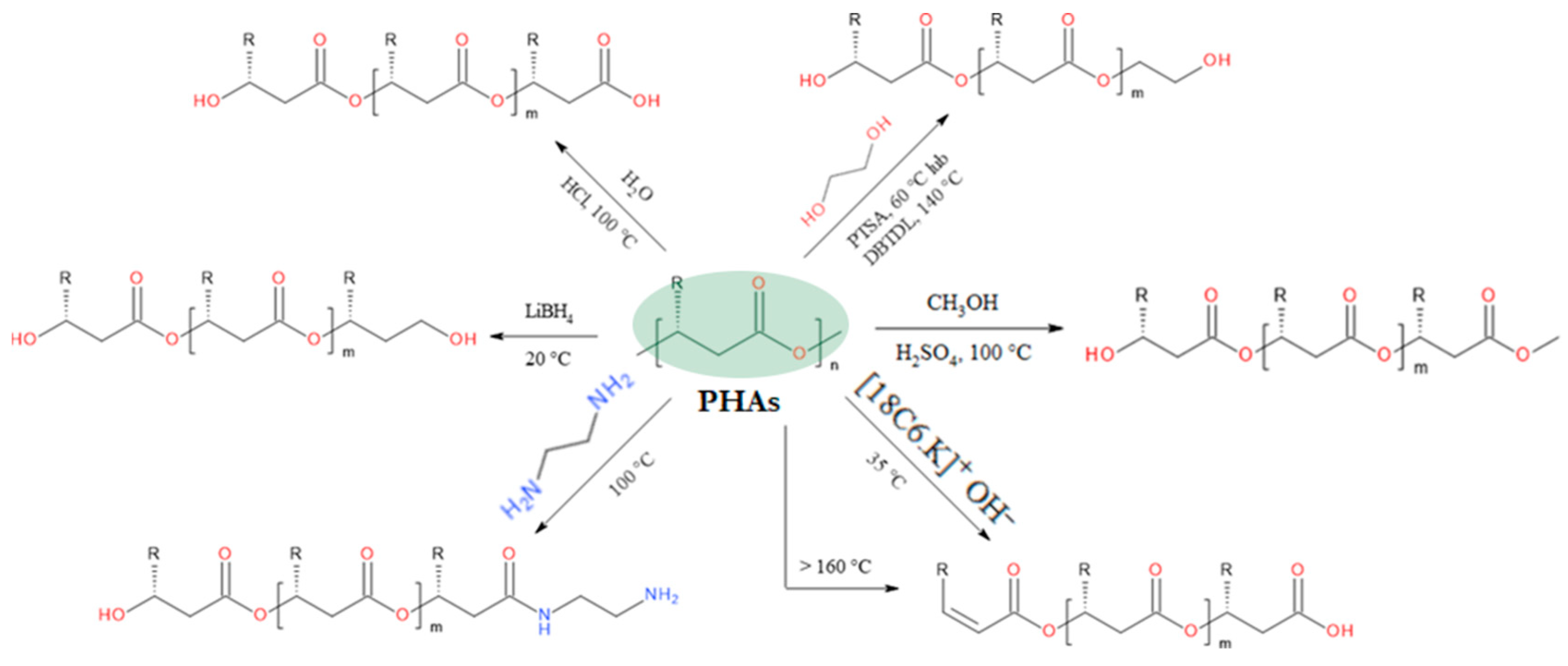

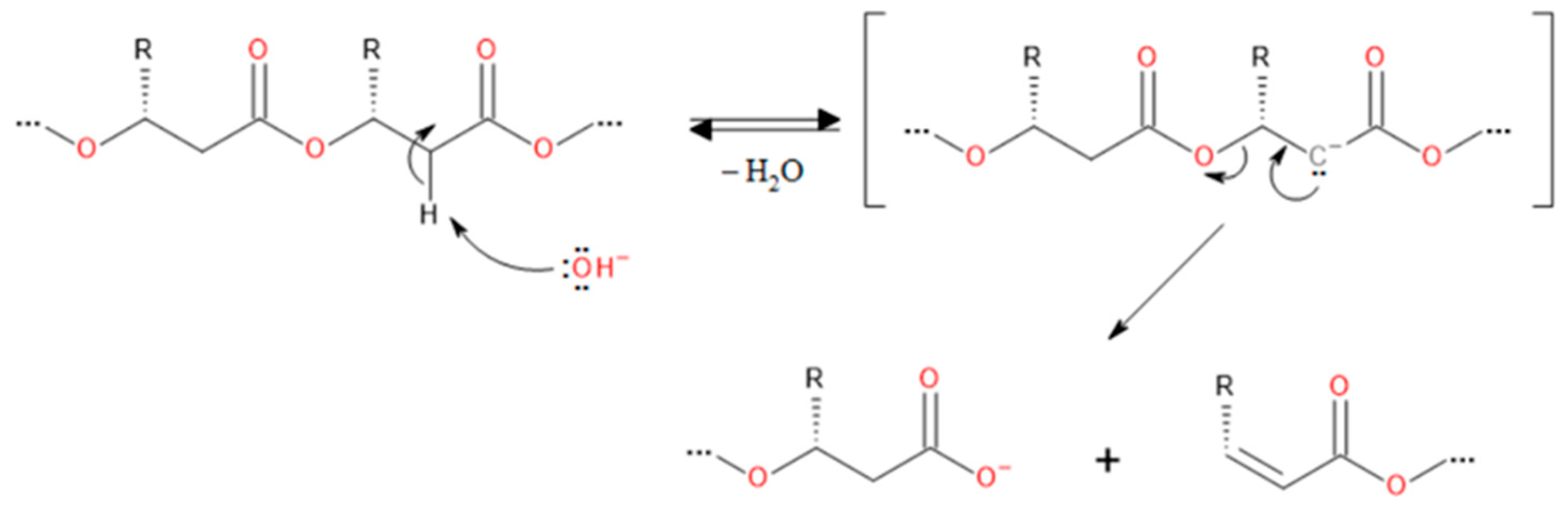

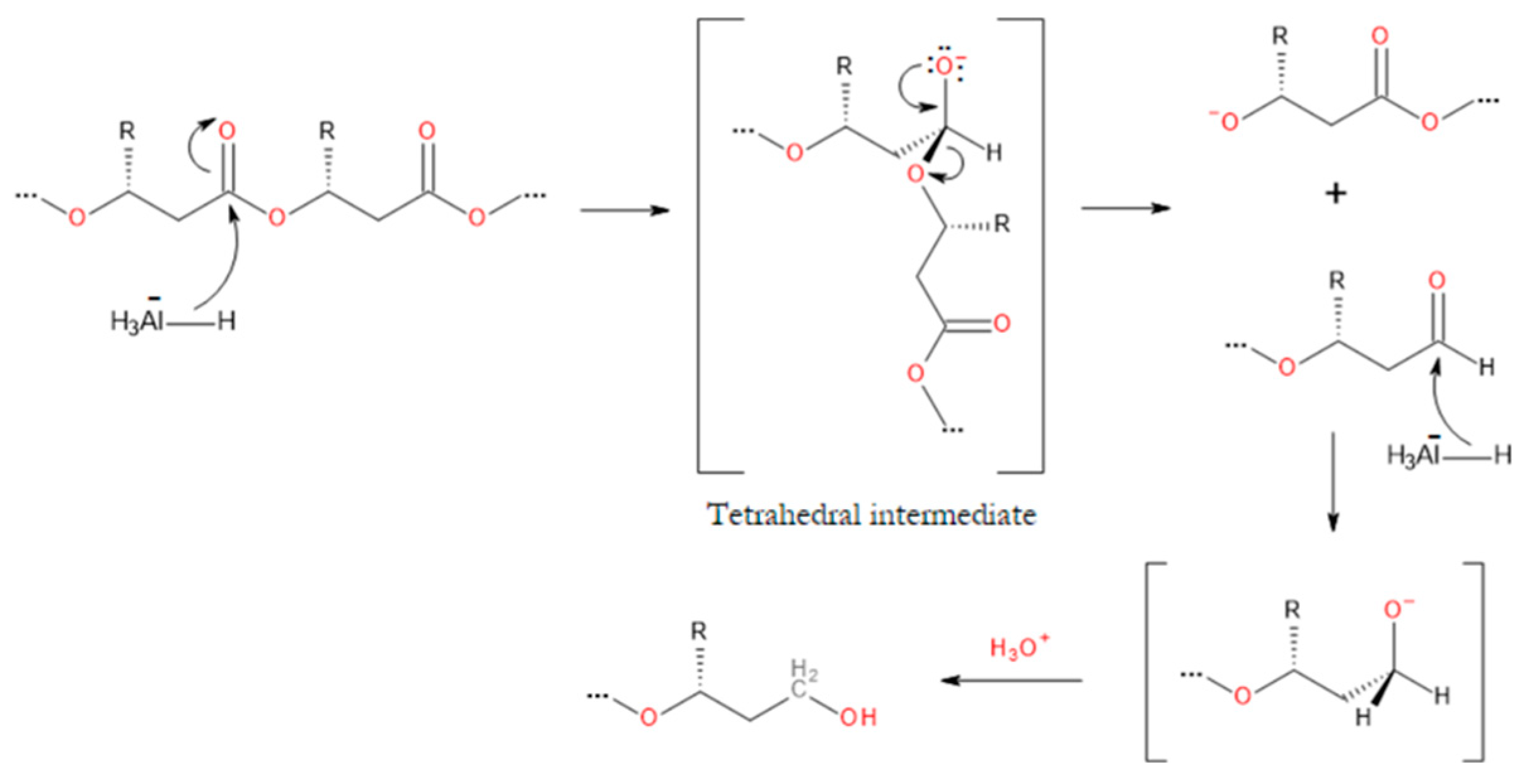

3.2. Degradation Reactions of PHA Chains

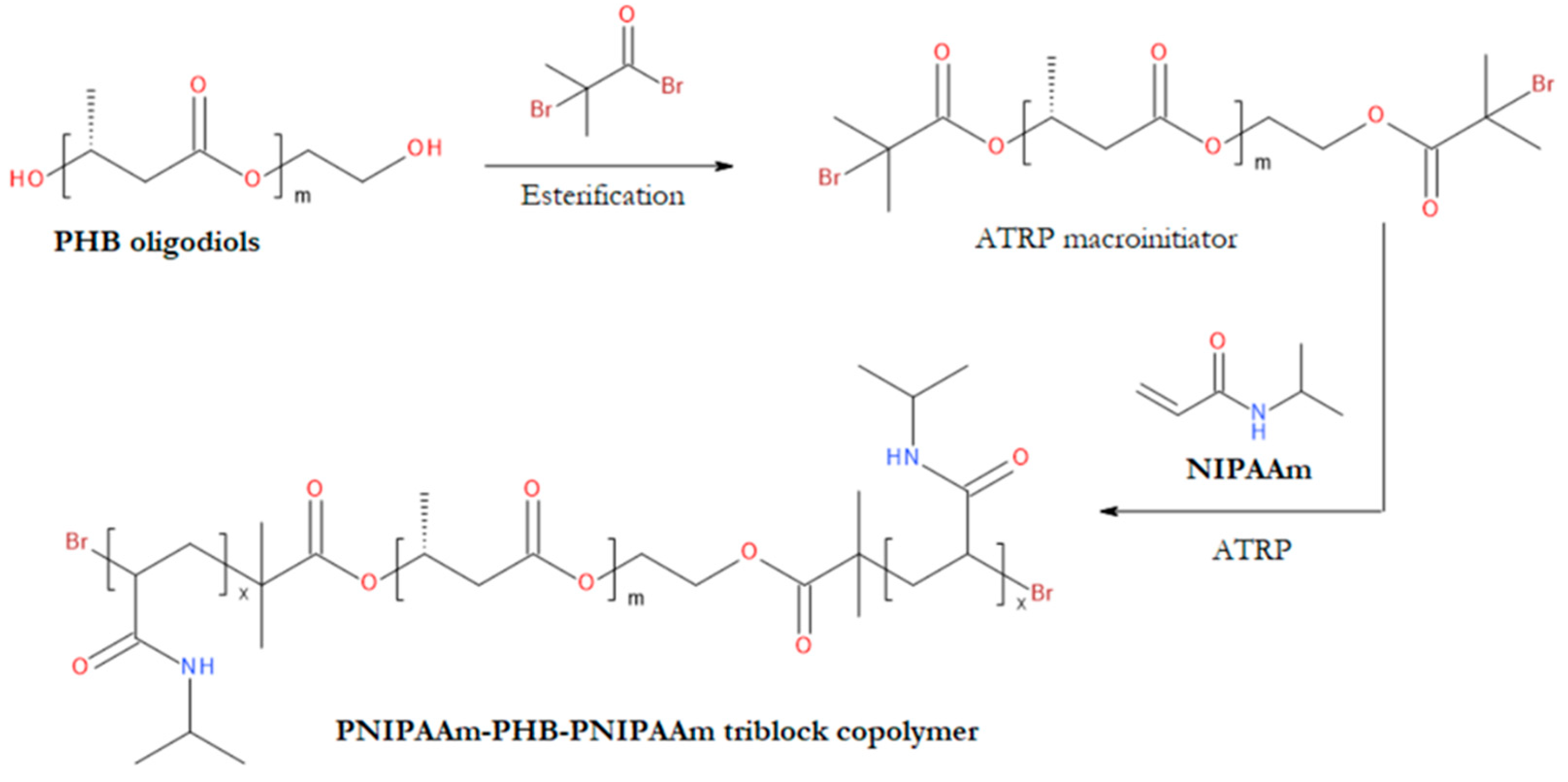

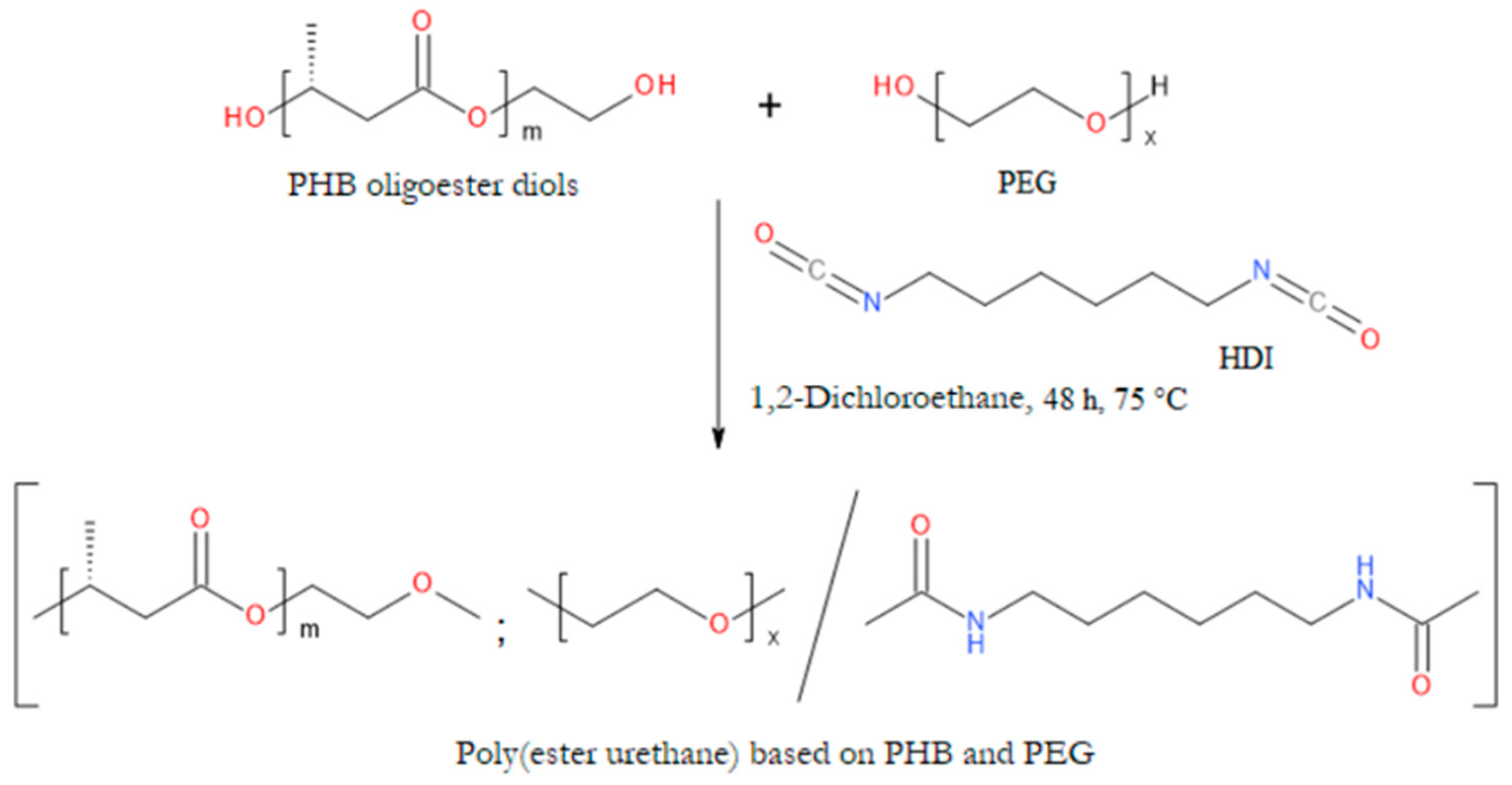

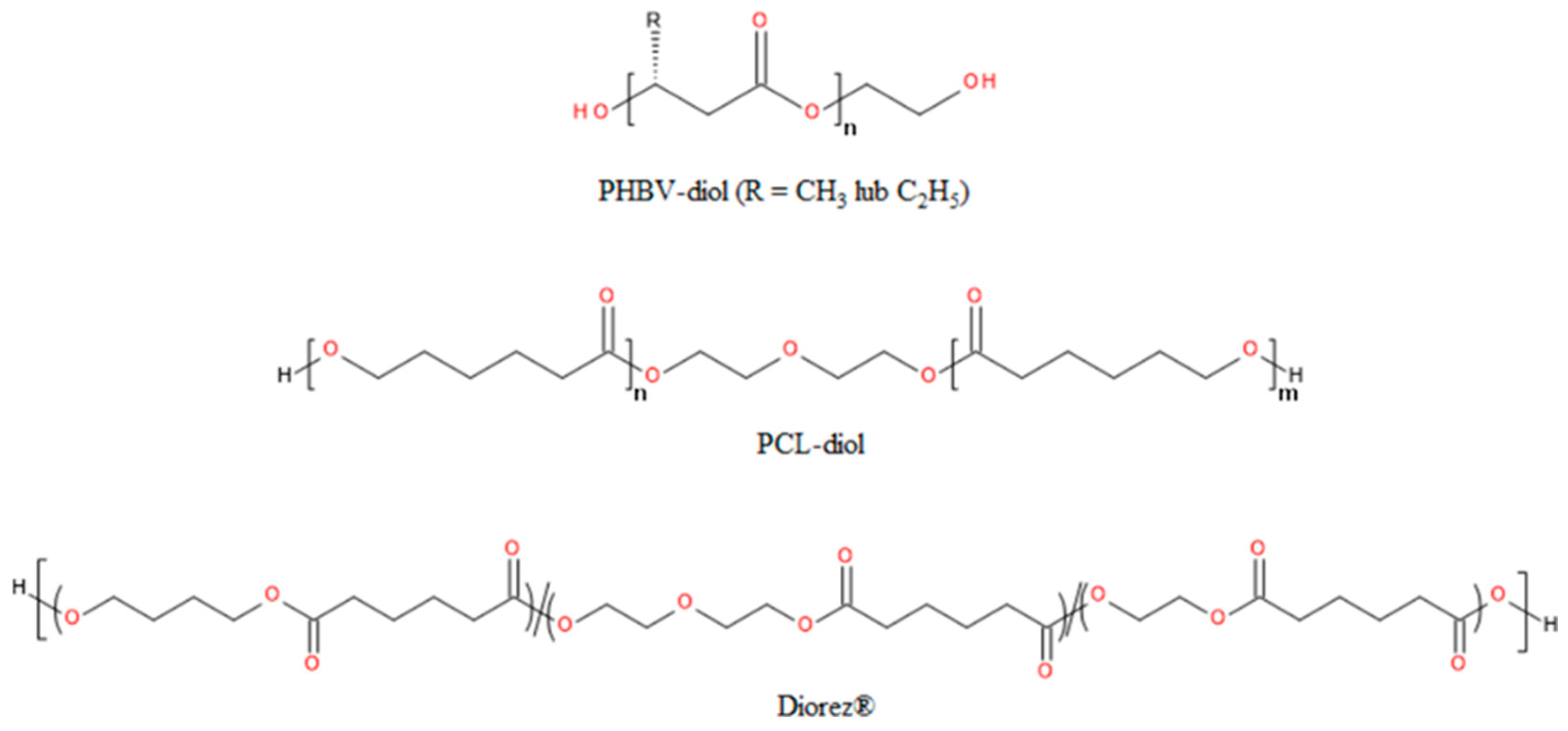

3.3. Block Copolymers Containing Blocks Derived from PHAs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castro-Sowinski Susana and Burdman, S. and Burdman, S. and M.O. and O.Y. Natural Functions of Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. In Plastics from Bacteria: Natural Functions and Applications; Chen, G.G.-Q., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; ISBN 978-3-642-03287-5. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, A.; Zuber, M.; Zia, K.M.; Noreen, A.; Anjum, M.N.; Tabasum, S. Microbial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and Its Copolymers: A Review of Recent Advancements. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 89, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Show, P.L.; Ooi, C.W.; Ling, T.C.; Lan, J.C.-W. Current Trends in Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Biosynthesis: Insights from the Recombinant Escherichia Coli. J Biotechnol 2014, 180, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Roy, I. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: The Emerging New Green Polymers of Choice. In A Handbook of Applied Biopolymer Technology: Synthesis, Degradation and Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011; pp. 79–101 ISBN 978-1-84973-151-5.

- Anderson, A.J.; Dawes, E.A. Occurrence, Metabolism, Metabolic Role, and Industrial Uses of Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev 1990, 54, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafim Luísa, S. and Xavier, A.M.R.B. and L.P.C. Storage of Hydrophobic Polymers in Bacteria. In Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes; Geiger, O., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-43676-0. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbüchel, A.; Valentin, H.E. Diversity of Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoic Acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1995, 128, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tappel, R.C.; Nomura, C.T. Mini-Review: Biosynthesis of Poly(Hydroxyalkanoates). Polymer Reviews 2009, 49, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii-Hyakutake, M.; Mizuno, S.; Tsuge, T. Biosynthesis and Characteristics of Aromatic Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, G.-Q. Production and Characterization of Terpolyester Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) by Recombinant Aeromonas Hydrophila 4AK4 Harboring Genes PhaAB. Process Biochemistry 2007, 42, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunasundari, B.; Sudesh, K. Isolation and Recovery of Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Express Polym Lett 2011, 5, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneswari, S.; Noor, M.S.M.; Amelia, T.S.M.; Balakrishnan, K.; Adnan, A.; Bhubalan, K.; Amirul, A.-A.A.; Ramakrishna, S. Recent Advances in the Biosynthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Lignocellulosic Feedstocks. Life 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolewski, S.; Jovanovic, M.; Perren, S.M.; Dillon, J.G.; Hughes, M.K. Tissue Response and in Vivo Degradation of Selected Polyhydroxyacids: Polylactides (PLA), Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHB/VA). J Biomed Mater Res 1993, 27, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.-H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, K.-Y.; Chen, G.Q. In Vivo Studies of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) Based Polymers: Biodegradation and Tissue Reactions. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3540–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, D.; Blanes, M.; Marco, B.; Cerrada, I.; Ruiz-Saurí, A.; Pelacho, B.; Araña, M.; Montero, J.A.; Cambra, V.; Prosper, F.; et al. A Comparison of Electrospun Polymers Reveals Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Fiber as a Superior Scaffold for Cardiac Repair. Stem Cells Dev 2014, 23, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Wu, L.-P.; Liu, X.-B.; Hou, J.; Zhao, L.-L.; Chen, J.-Y.; Zhao, D.-H.; Xiang, H. Biodegradation and Biocompatibility of Haloarchaea-Produced Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Copolymers. Biomaterials 2017, 139, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, S.L.; Sivashankari, R.; Shaharuddin, B.; Chuah, J.-A.; Tsuge, T.; Abe, H.; Sudesh, K. Potential Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanoates as a Biomaterial for the Aging Population. Polym Degrad Stab 2020, 181, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Zhang, J. Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates as Medical Implant Biomaterials. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2018, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniuk, Ł.; Stachewicz, U. Development and Advantages of Biodegradable PHA Polymers Based on Electrospun PHBV Fibers for Tissue Engineering and Other Biomedical Applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2021, 7, 5339–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.-Q. Medical Application of Microbial Biopolyesters Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology 2009, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yang, K.; Qin, X.; Luo, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, R. Polyhydroxyalkanoates in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Engineered Regeneration 2022, 3, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Lee, W.-H.; Loo, C.-Y.; Wong, H.S.J.; Parumasivam, T. Advances in Polyhydroxyalkanoate Nanocarriers for Effective Drug Delivery: An Overview and Challenges. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Kurcok, P.; Hakkarainen, M. Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Polym Int 2017, 66, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barouti, G.; Jaffredo, C.G.; Guillaume, S.M. Advances in Drug Delivery Systems Based on Synthetic Poly(Hydroxybutyrate) (Co)Polymers. Prog Polym Sci 2017, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Kalia, V.C. Biomedical Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Indian J Microbiol 2017, 57, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthuraj, R.; Valerio, O.; Mekonnen, T.H. Recent Developments in Short- and Medium-Chain- Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Production, Properties, and Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 187, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, C.; Tanner, E.T.; Bonfield, W. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Polyhydroxybutyrate and of Polyhydroxybutyrate Reinforced with Hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials 1991, 12, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; You, M.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Emerging Bone Tissue Engineering via Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)-Based Scaffolds. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 79, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabapathy, P.C.; Devaraj, S.; Meixner, K.; Anburajan, P.; Kathirvel, P.; Ravikumar, Y.; Zabed, H.M.; Qi, X. Recent Developments in Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Production – A Review. Bioresour Technol 2020, 306, 123132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obulisamy, P.K.; Mehariya, S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Extremophiles: A Review. Bioresour Technol 2021, 325, 124653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xi, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, M.; Xi, B.; Hou, L. A Review on Polyhydroxyalkanoates Production from Various Organic Waste Streams: Feedstocks, Strains, and Production Strategy. Resour Conserv Recycl 2023, 198, 107166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukala, I.; Kučera, I. Natural Polyhydroxyalkanoates—An Overview of Bacterial Production Methods. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, D.; Loh, X.J. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Chemical Modifications Toward Biomedical Applications. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2014, 2, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Loh, X.J. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Opening Doors for a Sustainable Future. NPG Asia Mater 2016, 8, e265–e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, M.; Wu, G. Surface Modification of Polyhydroxyalkanoates toward Enhancing Cell Compatibility and Antibacterial Activity. Macromol Mater Eng 2017, 302, 1700258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Z.A.; Riaz, S.; Banat, I.M. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Properties and Chemical Modification Approaches for Their Functionalization. Biotechnol Prog 2018, 34, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-malek, F.A.; Steinbüchel, A. Post-Synthetic Enzymatic and Chemical Modifications for Novel Sustainable Polyesters. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffur, B.N.; Kumar, G.; Jeetah, P.; Ramakrishna, S.; Bhatia, S.K. Current Advances and Emerging Trends in Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoate Modification from Organic Waste Streams for Material Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 126781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wu, C.; Yang, W.; Liang, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, L. Recent Advance in Surface Modification for Regulating Cell Adhesion and Behaviors. Nanotechnol Rev 2020, 9, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer-Lombarte, A.; Chen, S.-T.; Malliaras, G.G.; Barone, D.G. Foreign Body Reaction to Implanted Biomaterials and Its Impact in Nerve Neuroprosthetics. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandi, L.-J.; Chan, C.M.; Werker, A.; Richardson, D.; Laycock, B.; Pratt, S. Wood-PHA Composites: Mapping Opportunities. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Udduttula, A.; Fan, Z.S.; Chen, J.H.; Sun, A.R.; Zhang, P. Microbial-Derived Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: Biosynthesis, Properties, and Perspectives. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H.; Barletta, M.; Laheurte, P.; Langlois, V. Additive Manufacturing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Biopolymers: Materials, Printing Techniques, and Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 127, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulingam, T.; Appaturi, J.N.; Parumasivam, T.; Ahmad, A.; Sudesh, K. Biomedical Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanoate in Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.A.; Taylor, C.S.; Fricker, A.T.R.; Asare, E.; Tetali, S.S.V.; Haycock, J.W.; Roy, I. Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Their Advances for Biomedical Applications. Trends Mol Med 2022, 28, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puppi, D.; Pecorini, G.; Chiellini, F. Biomedical Processing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Bioengineering 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdam, B.; Brennan Fournet, M.; McDonald, P.; Mojicevic, M. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and Factors Impacting Its Chemical and Mechanical Characteristics. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitomo, H.; Hsieh, W.-C.; Nishiwaki, K.; Kasuya, K.; Doi, Y. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) Produced by Comamonas Acidovorans. Polymer (Guildf) 2001, 42, 3455–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazer, B.; Steinbüchel, A. Increased Diversification of Polyhydroxyalkanoates by Modification Reactions for Industrial and Medical Applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P.A. Applications of PHB—A Microbially Produced Biodegradable Thermoplastic. Physics in Technology 1985, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, E.; Ando, Y. Piezoelectric Properties of Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate and Copolymers of β-Hydroxybutyrate and β-Hydroxyvalerate. Int J Biol Macromol 1986, 8, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryadko, A.; Surmeneva, M.A.; Surmenev, R.A. Review of Hybrid Materials Based on Polyhydroxyalkanoates for Tissue Engineering Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, B.; Blaker, J.J.; Cartmell, S.H. Piezoelectric Materials as Stimulatory Biomedical Materials and Scaffolds for Bone Repair. Acta Biomater 2018, 73, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, D.; Basu, B.; Dubey, A.K. Electrical Stimulation and Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ji, J.; Lv, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, D. Application of Piezoelectric Material and Devices in Bone Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichý, J.; Erhart, J.; Kittinger, E.; Přívratská, J. Principles of Piezoelectricity. In Fundamentals of Piezoelectric Sensorics: Mechanical, Dielectric, and Thermodynamical Properties of Piezoelectric Materials; Tichý, J., Erhart, J., Kittinger, E., Přívratská, J., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; ISBN 978-3-540-68427-5. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A.; Popowski, K.; Cheng, K.; Greenbaum, A.; Ligler, F.S.; Moatti, A. Enhancement of Bone Regeneration through the Converse Piezoelectric Effect, A Novel Approach for Applying Mechanical Stimulation. Bioelectricity 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernozem, R.V.; Surmeneva, M.A.; Shkarina, S.N.; Loza, K.; Epple, M.; Ulbricht, M.; Cecilia, A.; Krause, B.; Baumbach, T.; Abalymov, A.A.; et al. Piezoelectric 3-D Fibrous Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)-Based Scaffolds Ultrasound-Mineralized with Calcium Carbonate for Bone Tissue Engineering: Inorganic Phase Formation, Osteoblast Cell Adhesion, and Proliferation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11, 19522–19533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Basirun, W.J.; Razak, B.A.; Alias, R. Bioinspired Ceramics for Bone Tissue Applications. In Ceramic Science and Engineering: Basics to Recent Advancements; Misra, K.P., Misra, R.D.K., Eds.; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 111–143 ISBN 978-0-323-89956-7.

- O’Brien, F.J. Biomaterials & Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Materials Today 2011, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskin, E. Biodegradable Polymers as Biomaterials. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 1995, 6, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Kanesawa, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kunioka, M. Hydrolytic Degradation of Microbial Poly(Hydroxyalkanoates). Die Makromolekulare Chemie, Rapid Communications 1989, 10, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishatskaya, E.I.; Volova, T.G.; Gordeev, S.A.; Puzyr, A.P. Degradation of P(3HB) and P(3HB-Co-3HV) in Biological Media. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2005, 16, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freier, T.; Kunze, C.; Nischan, C.; Kramer, S.; Sternberg, K.; Saß, M.; Hopt, U.T.; Schmitz, K.-P. In Vitro and in Vivo Degradation Studies for Development of a Biodegradable Patch Based on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate). Biomaterials 2002, 23, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuikov, V.A.; Bonartsev, A.P.; Makhina, T.K.; Myshkina, V.L.; Voinova, V.V.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Shaitan, K. V Hydrolytic Degradation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Its Copolymer with 3-Hydroxyvalerate of Different Molecular Weights in Vitro. Biophysics (Oxf) 2018, 63, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudesh, K.; Abe, H.; Doi, Y. Synthesis, Structure and Properties of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Biological Polyesters. Prog Polym Sci 2000, 25, 1503–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodicka, J.; Wikarska, M.; Trudicova, M.; Juglova, Z.; Pospisilova, A.; Kalina, M.; Slaninova, E.; Obruca, S.; Sedlacek, P. Degradation of P(3HB-Co-4HB) Films in Simulated Body Fluids. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunze, C.; Edgar Bernd, H.; Androsch, R.; Nischan, C.; Freier, T.; Kramer, S.; Kramp, B.; Schmitz, K.-P. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies on Blends of Isotactic and Atactic Poly (3-Hydroxybutyrate) for Development of a Dura Substitute Material. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonartsev, A.P.; Boskhomodgiev, A.P.; Iordanskii, A.L.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Rebrov, A.V.; Makhina, T.K.; Myshkina, V.L.; Yakovlev, S.A.; Filatova, E.A.; Ivanov, E.A.; et al. Hydrolytic Degradation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate), Polylactide and Their Derivatives: Kinetics, Crystallinity, and Surface Morphology. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 2012, 556, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroiné, M.; Le Duigou, A.; Corre, Y.-M.; Le Gac, P.-Y.; Davies, P.; César, G.; Bruzaud, S. Accelerated Ageing and Lifetime Prediction of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) in Distilled Water. Polym Test 2014, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, P.-S.; Ch’ng, D.H.-E.; Ong, S.-P.; Numata, K.; Sudesh, K. Characterization of the Depolymerizing Activity of Commercial Lipases and Detection of Lipase-like Activities in Animal Organ Extracts Using Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) Thin Film. AMB Express 2016, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeiter, D.; Lebahn, K.; Reske, T.; Senz, V.; Eickner, T.; Schmitz, K.-P.; Grabow, N.; Oschatz, S. Comparison of Accelerated and Enzyme-Associated Real-Time Degradation of HMW PLLA and HMW P3HB Films. Polym Test 2022, 107, 107471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskhomdzhiev, A.P.; Bonartsev, A.P.; Makhina, T.K.; Myshkina, V.L.; Ivanov, E.A.; Bagrov, D.V.; Filatova, E.V.; Iordanskii, A.L.; Bonartseva, G.A. Biodegradation Kinetics of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)-Based Biopolymer Systems. Biochem Mosc Suppl B Biomed Chem 2010, 4, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng, D.H.-E.; Sudesh, K. Densitometry Based Microassay for the Determination of Lipase Depolymerizing Activity on Polyhydroxyalkanoate. AMB Express 2013, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, N.A.; Machatschek, R.; Lendlein, A. Influence of Depolymerases and Lipases on the Degradation of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Determined in Langmuir Degradation Studies. Adv Mater Interfaces 2020, 7, 2000872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuikov, V.A.; Zhuikova, Y.V.; Makhina, T.K.; Myshkina, V.L.; Rusakov, A.; Useinov, A.; Voinova, V.V.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Berlin, A.A.; Bonartsev, A.P.; et al. Comparative Structure-Property Characterization of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate)s Films under Hydrolytic and Enzymatic Degradation: Finding a Transition Point in 3-Hydroxyvalerate Content. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuikov, V.A.; Akoulina, E.A.; Chesnokova, D.V.; Wenhao, Y.; Makhina, T.K.; Demyanova, I.V.; Zhuikova, Y.V.; Voinova, V.V.; Belishev, N.V.; Surmenev, R.A.; et al. The Growth of 3T3 Fibroblasts on PHB, PLA and PHB/PLA Blend Films at Different Stages of Their Biodegradation In Vitro. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melani, N.B.; Tambourgi, E.B.; Silveira, E. Lipases: From Production to Applications. Separation & Purification Reviews 2020, 49, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M. Human Digestive and Metabolic Lipases—a Brief Review. J Mol Catal B Enzym 2003, 22, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Doi, Y.; Sema, Y.; Tomita, K. Substrate Specificities in Hydrolysis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates by Microbial Esterases. Biotechnol Lett 1993, 15, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, J.-A.; Yamada, M.; Taguchi, S.; Sudesh, K.; Doi, Y.; Numata, K. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Containing 5-Hydroxyvalerate Units: Effects of 5HV Units on Biodegradability, Cytotoxicity, Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Polym Degrad Stab 2013, 98, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonartsev, A.P.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Reshetov, I.V.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Shaitan, K. V Application of Polyhydroxyalkanoates in Medicine and the Biological Activity of Natural Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate). Acta Naturae 2019, 11, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volova, T.G.; Shishatskaya, E.I.; Nikolaeva, E.D.; Sinskey, A.J. In Vivo Study of 2D PHA Matrices of Different Chemical Compositions: Tissue Reactions and Biodegradations. Materials Science and Technology 2014, 30, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, B.; Ciardelli, G.; Matter, S.; Welti, M.; Uhlschmid, G.K.; Neuenschwander, P.; Suter, U.W. Degradable and Highly Porous Polyesterurethane Foam as Biomaterial: Effects and Phagocytosis of Degradation Products in Osteoblasts. J Biomed Mater Res 1998, 39, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.-C.; Yao, Y.-C.; Zhan, X.-Y.; Chen, G.-Q. Application of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Nanoparticles as Intracellular Sustained Drug-Release Vectors. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2010, 21, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonartsev, A.P.; Voinova, V.V.; Bonartseva, G.A. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Human Microbiota (Review). Appl Biochem Microbiol 2018, 54, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cool, S.M.; Kenny, B.; Wu, A.; Nurcombe, V.; Trau, M.; Cassady, A.I.; Grøndahl, L. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Composite Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Regeneration: In Vitro Performance Assessed by Osteoblast Proliferation, Osteoclast Adhesion and Resorption, and Macrophage Proinflammatory Response. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007, 82A, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pol, B.J.M.; van der Does, L.; Bantjes, A.; van Wachem, P.B.; van Luyn, M.J.A. In Vivo Testing of Crosslinked Polyethers. I. Tissue Reactions and Biodegradation. J Biomed Mater Res 1996, 32, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wachem, P.B.; van Luyn, M.J.A.; Damink, L.H.H.O.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J.; Nieuwenhuis, P. Biocompatibility and Tissue Regenerating Capacity of Crosslinked Dermal Sheep Collagen. J Biomed Mater Res 1994, 28, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, Z.; Brooks, P.J.; Barzilay, O.; Fine, N.; Glogauer, M. Macrophages, Foreign Body Giant Cells and Their Response to Implantable Biomaterials. Materials 2015, 8, 5671–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.B.; Kyriakides, T.R. Molecular Characterization of Macrophage-Biomaterial Interactions. In Proceedings of the Immune Responses to Biosurfaces; Lambris, J.D., Ekdahl, K.N., Ricklin, D., Nilsson, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Artsis, M.I.; Bonartsev, A.P.; Iordanskii, A.L.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Zaikov, G.E. Biodegradation and Medical Application of Microbial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate). Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 2012, 555, 232–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.H.; Ishii, D.; Mahara, A.; Murakami, S.; Yamaoka, T.; Sudesh, K.; Samian, R.; Fujita, M.; Maeda, M.; Iwata, T. Scaffolds from Electrospun Polyhydroxyalkanoate Copolymers: Fabrication, Characterization, Bioabsorption and Tissue Response. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M. 9.19—Biocompatibility. In Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; Matyjaszewski, K., Möller, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2012; ISBN 978-0-08-087862-1. [Google Scholar]

- Iordanskii, A.L.; Bonartseva, G.A.; Pankova, Y.N.; Rogovina, S.Z.; Gumargalieva, K.Z.; Zaikov, G.E.; Berlin, A.A. Current Status and Biomedical Applications of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) as a Bacterial Biodegradable Polymer. Journal of Information, Intelligence and Knowledge 2014, 6, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Reusch, R.N. Physiological Importance of Poly-(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrates. Chem Biodivers 2012, 9, 2343–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedkova, E.N.; Blatter, L.A. Role of β-Hydroxybutyrate, Its Polymer Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate and Inorganic Polyphosphate in Mammalian Health and Disease. Front Physiol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Burgberger, M.; Wojtasik, W. 3-Hydroxybutyrate as a Metabolite and a Signal Molecule Regulating Processes of Living Organisms. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggam, M.I.; O’Kane, M.J.; Harper, R.; Atkinson, A.B.; Hadden, D.R.; Trimble, E.R.; Bell, P.M. Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis Using Normalization of Blood 3-Hydroxybutyrate Concentration as the Endpoint of Emergency Management: A Randomized Controlled Study. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Lenzen-Schulte, M.; Schloot, N.C.; Martin, S. Ketone Bodies: From Enemy to Friend and Guardian Angel. BMC Med 2021, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffel, L. Ketone Bodies: A Review of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Application of Monitoring to Diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 1999, 15, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, T.; Hirschey, M.D.; Newman, J.; He, W.; Shirakawa, K.; Le Moan, N.; Grueter, C.A.; Lim, H.; Saunders, L.R.; Stevens, R.D.; et al. Suppression of Oxidative Stress by β-Hydroxybutyrate, an Endogenous Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor. Science (1979) 2013, 339, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.-H.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Grant, R.W.; Goldberg, E.L.; Bodogai, M.; Kim, D.; D’Agostino, D.; Planavsky, N.; Lupfer, C.; Kanneganti, T.D.; et al. The Ketone Metabolite β-Hydroxybutyrate Blocks NLRP3 Inflammasome–Mediated Inflammatory Disease. Nat Med 2015, 21, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Morales, P.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Tapia, E. Ketone Bodies, Stress Response, and Redox Homeostasis. Redox Biol 2020, 29, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.M.; Wang, Z.H.; Luo, H.N.; Xu, M.; Ren, X.Y.; Zheng, G.X.; Wu, B.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Lu, X.Y.; Chen, F.; et al. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate)-Based Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2014, 47, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.Q. In Vitro Effect of Oligo-Hydroxyalkanoates on the Growth of Mouse Fibroblast Cell Line L929. Biomaterials 2007, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, J.A.; Webster, M.W.I.; Armstrong, G. First-in-Human Implantation of a Fully Bioabsorbable Drug-Eluting Stent: The BVS Poly-L-Lactic Acid Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2007, 69, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliephake, H.; Weich, H.A.; Schulz, J.; Gruber, R. In Vitro Characterization of a Slow Release System of Polylactic Acid and RhBMP2. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007, 83A, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böstman, O.; Pihlajamäki, H. Clinical Biocompatibility of Biodegradable Orthopaedic Implants for Internal Fixation: A Review. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kum, C.H.; Cho, Y.; Seo, S.H.; Joung, Y.K.; Ahn, D.J.; Han, D.K. A Poly(Lactide) Stereocomplex Structure with Modified Magnesium Oxide and Its Effects in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties and Suppressing Inflammation. Small 2014, 10, 3783–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistner, H.; Gutwald, R.; Ordung, R.; Reuther, J.; Mühling, J. Poly(l-Lactide): A Long-Term Degradation Study in Vivo: I. Biological Results. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Nguyen, T.D.; Yi, X.; Lyu, Y.; Lan, Z.; Xia, J.; Wu, T.; Jiang, X. Evaluation of Long-Term Inflammatory Responses after Implantation of a Novel Fully Bioabsorbable Scaffold Composed of Poly-L-Lactic Acid and Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles. J Nanomater 2018, 2018, 1519480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C.M.; Athanasiou, K.A. Technique to Control PH in Vicinity of Biodegrading PLA-PGA Implants. J Biomed Mater Res 1997, 38, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Otsuki, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Inoue, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Sato, H.; Neo, M. Establishment of Novel Meniscal Scaffold Structures Using Polyglycolic and Poly-l-Lactic Acids. J Biomater Appl 2017, 32, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manavitehrani, I.; Fathi, A.; Wang, Y.; Maitz, P.K.; Dehghani, F. Reinforced Poly(Propylene Carbonate) Composite with Enhanced and Tunable Characteristics, an Alternative for Poly(Lactic Acid). ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 22421–22430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, A.A.; Claes, L.E. In Vitro Biocompatibility of Bioresorbable Polymers: Poly(L, DL-Lactide) and Poly(L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide). Biomaterials 1996, 17, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceonzo, K.; Gaynor, A.; Shaffer, L.; Kojima, K.; Vacanti, C.A.; Stahl, G.L. Polyglycolic Acid-Induced Inflammation: Role of Hydrolysis and Resulting Complement Activation. Tissue Eng 2006, 12, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, Q.A.; Fricker, A.T.R.; Gregory, D.A.; Davidenko, N.; Hernandez Cruz, O.; Jabbour, R.J.; Owen, T.J.; Basnett, P.; Lukasiewicz, B.; Stevens, M.; et al. Natural Biomaterials for Cardiac Tissue Engineering: A Highly Biocompatible Solution. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Y. Study of the in Vitro Cytotoxicity Testing of Medical Devices. Biomed Rep 2015, 3, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Tian, L.; Wang, C.; Liao, S.; Teo, W.E. 6 - Safety Testing of a New Medical Device. In Medical Devices; Ramakrishna, S., Tian, L., Wang, C., Liao, S., Teo, W.E., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2015; pp. 137–153 ISBN 978-0-08-100289-6.

- Sombatmankhong, K.; Sanchavanakit, N.; Pavasant, P.; Supaphol, P. Bone Scaffolds from Electrospun Fiber Mats of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate), Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) and Their Blend. Polymer (Guildf) 2007, 48, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwantong, O.; Waleetorncheepsawat, S.; Sanchavanakit, N.; Pavasant, P.; Cheepsunthorn, P.; Bunaprasert, T.; Supaphol, P. In Vitro Biocompatibility of Electrospun Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Fiber Mats. Int J Biol Macromol 2007, 40, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaber, P.; Tylko, G.; Włodarczyk, J.; Nitschke, P.; Hercog, A.; Jurczyk, S.; Rech, J.; Kubacki, J.; Adamus, G. Surface Modification of PHBV Fibrous Scaffold via Lithium Borohydride Reduction. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalcik, A.; Obruca, S.; Kalina, M.; Machovsky, M.; Enev, V.; Jakesova, M.; Sobkova, M.; Marova, I. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Scaffolds. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-W.; Guo, X.-Y.; Shang, G.-G.; Li, J.; Xu, X.-Y.; You, M.-L.; Li, P.; Chen, G.-Q. An Assessment of the Risks of Carcinogenicity Associated with Polyhydroxyalkanoates through an Analysis of DNA Aneuploid and Telomerase Activity. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2546–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Chen, D.; Guo, J.-L.; Feng, D.-F.; Sun, M.-Z.; Lu, Y.; Chen, D.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Feng, X.-Z. Evaluating the Biological Impact of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) on Developmental and Exploratory Profile of Zebrafish Larvae. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 37018–37030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazão, L.P.; Vieira de Castro, J.; Neves, N.M. In Vivo Evaluation of the Biocompatibility of Biomaterial Device. In Biomimicked Biomaterials: Advances in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine; Chun, H.J., Reis, R.L., Motta, A., Khang, G., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-3262-7. [Google Scholar]

- Volova, T.; Shishatskaya, E.; Sevastianov, V.; Efremov, S.; Mogilnaya, O. Results of Biomedical Investigations of PHB and PHB/PHV Fibers. Biochem Eng J 2003, 16, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, C.J.; Sinskey, A.J. Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanoates in the Medical Industry. Int J Biotechnol Wellness Ind 2012, 1, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, W.M.; Kyriakides, T.R. Chapter 16 - Cell Interactions with Polymers. In Principles of Tissue Engineering (Fifth Edition); Lanza, R., Langer, R., Vacanti, J.P., Atala, A., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 275–293 ISBN 978-0-12-818422-6.

- Taraballi, F.; Sushnitha, M.; Tsao, C.; Bauza, G.; Liverani, C.; Shi, A.; Tasciotti, E. Biomimetic Tissue Engineering: Tuning the Immune and Inflammatory Response to Implantable Biomaterials. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7, 1800490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishatskaya, E.I.; Voinova, O.N.; Goreva, A.V.; Mogilnaya, O.A.; Volova, T.G. Biocompatibility of Polyhydroxybutyrate Microspheres: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2008, 19, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkusuz, F.; Korkusuz, P.; Ekşioĝlu, F.; Gürsel, İ.; Hasırcı, V. In Vivo Response to Biodegradable Controlled Antibiotic Release Systems. J Biomed Mater Res 2001, 55, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, R.J.; Jones, K.S. The Recognition of Biomaterials: Pattern Recognition of Medical Polymers and Their Adsorbed Biomolecules. J Biomed Mater Res A 2013, 101A, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Campisi, J. Chronic Inflammation (Inflammaging) and Its Potential Contribution to Age-Associated Diseases. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2014, 69, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba, M.; Chaber, P.; Duale, K.; Martinka Maksymiak, M.; Basczok, M.; Kowalczuk, M.; Adamus, G. Polymeric Carriers for Delivery Systems in the Treatment of Chronic Periodontal Disease. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, H.K.; Das, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Ramakrishna, S. Biocompatibility of Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration or Replacement. Biotechnol J 2020, 15, 2000160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, R.J.; Jones, K.S. Biomaterials, Fibrosis, and the Use of Drug Delivery Systems in Future Antifibrotic Strategies. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 2009, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. Chapter 9 - Fibrotic Response to Biomaterials and All Associated Sequence of Fibrosis. In Host Response to Biomaterials; Badylak, S.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2015; ISBN 978-0-12-800196-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, X.; Lennartz, M.R.; Loegering, D.J.; Stenken, J.A. Long-Term Calibration Considerations during Subcutaneous Microdialysis Sampling in Mobile Rats. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4530–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.F.; Martin, D.P.; Horowitz, D.M.; Peoples, O.P. PHA Applications: Addressing the Price Performance Issue: I. Tissue Engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 1999, 25, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevastianov, V.I.; Perova, N.V.; Shishatskaya, E.I.; Kalacheva, G.S.; Volova, T.G. Production of Purified Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) for Applications in Contact with Blood. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2003, 14, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigot-Luizard, M.F.; Warocquier-Clerout, R. In Vitro Cytocompatibility Tests. In Test Procedures for the Blood Compatibility of Biomaterials; Dawids, S., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1993; ISBN 978-94-011-1640-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Bian, Y.Z.; Wu, Q.; Chen, G.Q. Evaluation of Three-Dimensional Scaffolds Prepared from Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) for Growth of Allogeneic Chondrocytes for Cartilage Repair in Rabbits. Biomaterials 2008, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Fu, N.; Xie, J.; Fu, Y.; Deng, S.; Cun, X.; Wei, X.; Peng, Q.; Cai, X.; Lin, Y. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) Based Electrospun 3D Scaffolds for Delivery of Autogeneic Chondrocytes and Adipose-Derived Stem Cells: Evaluation of Cartilage Defects in Rabbit. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Li, X.-T.; Chen, G.-Q. Interactions between a Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) Terpolyester and Human Keratinocytes. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3807–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Li, X.-T.; Peng, S.-W.; Xiao, J.-F.; Liu, C.; Fang, G.; Chen, K.C.; Chen, G.-Q. The Behaviour of Neural Stem Cells on Polyhydroxyalkanoate Nanofiber Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3967–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniuk, Ł.; Krysiak, Z.J.; Metwally, S.; Stachewicz, U. Osteoblasts and Fibroblasts Attachment to Poly(3-Hydroxybutyric Acid-Co-3-Hydrovaleric Acid) (PHBV) Film and Electrospun Scaffolds. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 110, 110668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.-H.; Wu, Q.; Liang, J.; Zou, B.; Chen, G.-Q. Effect of 3-Hydroxyhexanoate Content in Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) on in Vitro Growth and Differentiation of Smooth Muscle Cells. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2944–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.S.; Kwon, O.H.; Meng, W.; Kang, I.-K.; Ito, Y. Nanofabrication of Microbial Polyester by Electrospinning Promotes Cell Attachment. Macromol Res 2004, 12, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, B.; Witholt, B. Synthesis, Recovery and Possible Application of Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Short Overview. Macromol Symp 1998, 130, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Loh, X.J.; Wang, K.; He, C.; Li, J. Poly(Ester Urethane)s Consisting of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] and Poly(Ethylene Glycol) as Candidate Biomaterials: Characterization and Mechanical Property Study. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 2740–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, K.L.; Li, J.; Tan, E.P.S.; Chan, L.M.; Lim, C.T.; Goh, S.H. Synthesis, Characterization, and Morphology Studies of Biodegradable Amphiphilic Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]-Alt-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Multiblock Copolymers. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 3112–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekere, A.I.; Radecka, I.; Kurcok, P.; Adamus, G.; Konieczny, T.; Zięba, M.; Chaber, P.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F.; Kowalczuk, M. Bioactive and Functional Oligomers Derived from Natural PHA and Their Synthetic Analogs. In The Handbook of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Postsynthetic Treatment, Processing and Application; Koller, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Don, T.M.; Liao, K.H. Studies on the Alcoholysis of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and the Synthesis of PHB-b-PLA Block Copolymer for the Preparation of PLA/PHB-b-PLA Blends. Journal of Polymer Research 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domiński, A.; Krawczyk, M.; Konieczny, T.; Kasprów, M.; Foryś, A.; Pastuch-Gawołek, G.; Kurcok, P. Biodegradable PH-Responsive Micelles Loaded with 8-Hydroxyquinoline Glycoconjugates for Warburg Effect Based Tumor Targeting. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2020, 154, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insomphun, C.; Chuah, J.-A.; Kobayashi, S.; Fujiki, T.; Numata, K. Influence of Hydroxyl Groups on the Cell Viability of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2017, 3, 3064–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

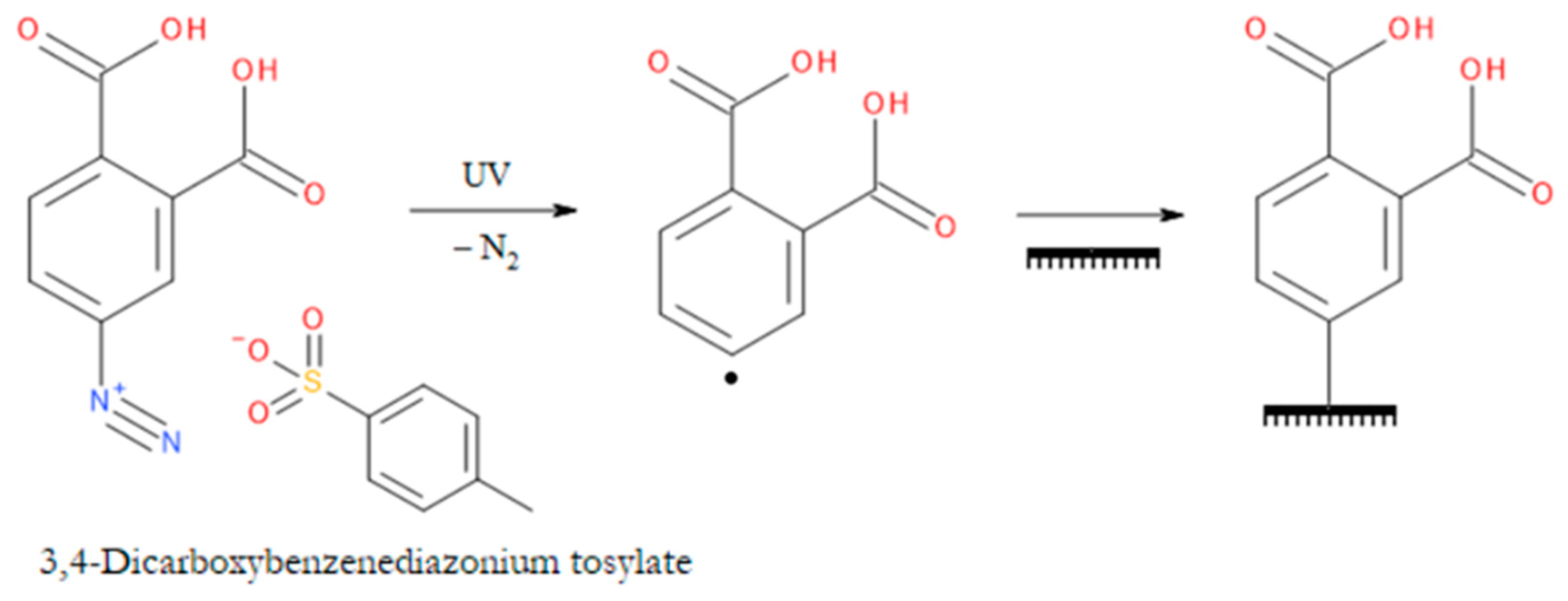

- Chernozem, R.V.; Guselnikova, O.; Surmeneva, M.A.; Postnikov, P.S.; Abalymov, A.A.; Parakhonskiy, B.V.; De Roo, N.; Depla, D.; Skirtach, A.G.; Surmenev, R.A. Diazonium Chemistry Surface Treatment of Piezoelectric Polyhydroxybutyrate Scaffolds for Enhanced Osteoblastic Cell Growth. Appl Mater Today 2020, 20, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompe, T.; Keller, K.; Mothes, G.; Nitschke, M.; Teese, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Werner, C. Surface Modification of Poly(Hydroxybutyrate) Films to Control Cell–Matrix Adhesion. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazer, D.B.; Kılıçay, E.; Hazer, B. Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoate)s: Diversification and Biomedical Applications: A State of the Art Review. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2012, 32, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasita, R.; Shanmugam, K.; Katti, D.S. Improved Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications: Surface Modification of Polymers. Curr Top Med Chem 2008, 8, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, P.; Messori, M. 5 - Surface Modification of Polymers: Chemical, Physical, and Biological Routes. In Modification of Polymer Properties; Jasso-Gastinel, C.F., Kenny, J.M., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing, 2017; pp. 109–130 ISBN 978-0-323-44353-1.

- Nemani, S.K.; Annavarapu, R.K.; Mohammadian, B.; Raiyan, A.; Heil, J.; Haque, Md.A.; Abdelaal, A.; Sojoudi, H. Surface Modification of Polymers: Methods and Applications. Adv Mater Interfaces 2018, 5, 1801247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, H.; Arzaghi, H.; Bayandori, M.; Dezfuli, A.S.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Shafiee, A.; Moradi, L. Controlling Cell Behavior through the Design of Biomaterial Surfaces: A Focus on Surface Modification Techniques. Adv Mater Interfaces 2019, 6, 1900572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, M.; Sitkowska, A.; Sobota, M.; Sieroń, A.L.; Komar, P.; Kurcok, P. Human Procollagen Type I Surface-Modified PHB-Based Non-Woven Textile Scaffolds for Cell Growth: Preparation and Short-Term Biological Tests. Biomedical Materials 2014, 9, 65005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, M.; Peng, G.; Li, J.; Ma, P.; Wang, Z.; Shu, W.; Peng, S.; Chen, G.-Q. Chondrogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Scaffolds Coated with PHA Granule Binding Protein PhaP Fused with RGD Peptide. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmail, A.; Pereira, J.R.; Zoio, P.; Silvestre, S.; Menda, U.D.; Sevrin, C.; Grandfils, C.; Fortunato, E.; Reis, M.A.M.; Henriques, C.; et al. Oxygen Plasma Treated-Electrospun Polyhydroxyalkanoate Scaffolds for Hydrophilicity Improvement and Cell Adhesion. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.A.; Qin, L.A.; Meyerson, H.; Kwon, I.K.; Matsuda, T.; Anderson, J.M. Instability of Self-Assembled Monolayers as a Model Material System for Macrophage/FBGC Cellular Behavior. J Biomed Mater Res A 2008, 86A, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncin-Epaillard, F.; Vrlinic, T.; Debarnot, D.; Mozetic, M.; Coudreuse, A.; Legeay, G.; El Moualij, B.; Zorzi, W. Surface Treatment of Polymeric Materials Controlling the Adhesion of Biomolecules. J Funct Biomater 2012, 3, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.M.; Quijada-Garrido, I.; López, L.; París, R.; Núñez-López, M.T.; de la Peña Zarzuelo, E.; Garrido, L. The Surface Modification of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) Copolymers to Improve the Attachment of Urothelial Cells. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2013, 33, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chen, C.H.; Tseng, H.W.; Liu, Y.W.; Chen, Y.P.; Lee, C.H.; Kuo, Y.J.; Hsu, C.H.; Sun, Y.M. Surface Functionalized Electrospun Fibrous Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Membranes and Sleeves: A Novel Approach for Fixation in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. J Mater Chem B 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pandey, J.; Raj, V.; Kumar, P. A Review on the Modification of Polysaccharide Through Graft Copolymerization for Various Potential Applications. Open Med Chem J 2017, 11, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Ramos, V.H.; Ramos-Ballesteros, A.; López-Saucedo, F.; López-Barriguete, J.E.; Varca, G.H.C.; Bucio, E. Radiation Grafting for the Functionalization and Development of Smart Polymeric Materials. Top Curr Chem 2016, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Misra, B.N. Grafting: A Versatile Means to Modify Polymers: Techniques, Factors and Applications. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2004, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, J.K.; Kaith, B.S.; Kalia, S. Recent Developments in Surface Modification of Natural Fibers for Their Use in Biocomposites. In Biodegradable Green Composites; 2016.

- Ashfaq, A.; Clochard, M.-C.; Coqueret, X.; Dispenza, C.; Driscoll, M.S.; Ulański, P.; Al-Sheikhly, M. Polymerization Reactions and Modifications of Polymers by Ionizing Radiation. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padeste, C.; Neuhaus, S. Polymer-on-Polymer Structures Based on Radiation Grafting. In Polymer Micro- and Nanografting; 2015.

- Saito, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Sugo, T. Fundamentals of Radiation-Induced Graft Polymerization. In Innovative Polymeric Adsorbents; 2018.

- Russell, K.E. Free Radical Graft Polymerization and Copolymerization at Higher Temperatures. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2002, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hioe, J.; Zipse, H. Radical Stability and Its Role in Synthesis and Catalysis. Org Biomol Chem 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; McDonald, A.G.; Stark, N.M. Grafting of Bacterial Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) onto Cellulose via In Situ Reactive Extrusion with Dicumyl Peroxide. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Segundo, E.I.; González-Torres, M.; Cabrera-Wrooman, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Huerta-Martínez, B.M.; Melgarejo-Ramírez, Y.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.M.; Cortés, H.; Velasquillo, C.; et al. Gamma Radiation-Induced Grafting of n-Hydroxyethyl Acrylamide onto Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate): A Companion Study on Its Polyurethane Scaffolds Meant for Potential Skin Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials Science and Engineering C 2020, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, C.H.; Davis, N.P.; Garnett, J.L.; Yen, N.T. The Nature of Bonding during Film Formation of Polyolefins and Cellulose Using UV and Ionizing Radiation Initiation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 1977, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, C.R.; Zhang, X.Q. Preparation, Thermal Properties, and Morphology of Graft Copolymers in Reactive Blends of PHBV and PPC. Polym Compos 2012, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanou, Y.; Fontanille, M. Chain Polymerizations. In Organic and Physical Chemistry of Polymers; 2008; pp. 249–356 ISBN 9780470238127.

- Tamizifar, M.; Sun, G. Control of Surface Radical Graft Polymerization on Polyester Fibers by Using Hansen Solubility Parameters as a Measurement of the Affinity of Chemicals to Materials. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 13299–13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, W. Developments and New Applications of UV-Induced Surface Graft Polymerizations. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2009, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, K.; Maeda, T.; Hotta, A. 9 - Polymer Surface Modifications by Coating. In Printing on Polymers; Izdebska, J., Thomas, S., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing, 2016; pp. 143–160 ISBN 978-0-323-37468-2.

- Moad, G. Synthesis of Polyolefin Graft Copolymers by Reactive Extrusion. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 1999, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Clénet, J.; Xu, H.; Odelius, K.; Hakkarainen, M. Two Step Extrusion Process: From Thermal Recycling of PHB to Plasticized PLA by Reactive Extrusion Grafting of PHB Degradation Products onto PLA Chains. Macromolecules 2015, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formela, K.; Hejna, A.; Haponiuk, J.; Tercjak, A. 8 - In Situ Processing of Biocomposites via Reactive Extrusion. In Biocomposites for High-Performance Applications; Ray, D., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2017; pp. 195–246 ISBN 978-0-08-100793-8.

- Rudnik, E. Chapter 4 - Thermal and Thermooxidative Degradation. In Compostable Polymer Materials; Rudnik, E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2008; ISBN 978-0-08-045371-2. [Google Scholar]

- de Koning, G.J.M.; Lemstra, P.J. Crystallization Phenomena in Bacterial Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]: 2. Embrittlement and Rejuvenation. Polymer (Guildf) 1993, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-G.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, W.H.; Cho, D.; Chung, H.Y.; Kwon, O.H. Surface Modification of PHBV Nanofiber Mats for Rapid Cell Cultivation and Harvesting. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2018, 29, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xi, T.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H. Quercetin Modified Electrospun PHBV Fibrous Scaffold Enhances Cartilage Regeneration. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2021, 32, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbart, L.; Renard, E.; Tessier, M.; Langlois, V. Monohydroxylated Poly(3-Hydroxyoctanoate) Oligomers and Its Functionalized Derivatives Used as Macroinitiators in the Synthesis of Degradable Diblock Copolyesters. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk-Soczynska, B.; Gradys, A.; Sajkiewicz, P. Hydrophilic Surface Functionalization of Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitomo, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshii, F.; Makuuchi, K. Radiation Effect on Polyesters. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 1995, 46, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitomo, H.; Enjôji, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshii, F.; Makuuchi, K.; Saito, T. Radiation-Induced Graft Polymerization of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Its Copolymer. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 1995, 32, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitomo, H.; Sasaoka, T.; Yoshii, F.; Makuuchi, K.; Saito, T. Radiation-Induced Graft Polymerization of Acrylic Acid onto Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Its Copolymer. Journal of Fiber Science and Technology 1996, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, K.; Mitomo, H.; Enjoji, T.; Hasegawa, S. Radiation-Induced Graft Polymerization of Styrene onto Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Its Copolymer with 3-Hydroxyvalerate. Angewandte Makromolekulare Chemie 1997, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Mitomo, H.; Kasuya, K.I.; Nagasawa, N.; Seko, N.; Katakai, A.; Tamada, M. Control of Biodegradability of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyric Acid) Film with Grafting Acrylic Acid and Thermal Remolding. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Seko, N.; Nagasawa, N.; Tamada, M.; Kasuya, K. ichi; Mitomo, H. Biodegradability of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Film Grafted with Vinyl Acetate: Effect of Grafting and Saponification. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2007, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, H.K.; Renard, E.; Linossier, I.; Langlois, V.; Vallée-Rehel, K. Modification of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Film by Chemical Graft Copolymerization. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, J. UV-Photodegradation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) (PHB-HHx). Macromol Res 2016, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastow, E.; Cook, S.; Dean, P.; Ott, P.; Wilson, J.; Yoon, H.; Dietz, T.; Bateman, F.; Al-Sheikhly, M. Single-Step Synthesis of Atmospheric CO2 Sorbents through Radiation-Induced Graft Polymerization on Commercial-Grade Fabrics. Radiat Res 2019, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, H.K.; Renard, E.; Langlois, V.; Vallée-Rehel, K.; Linossier, I. Surface Functionalization of PHBV by HEMA Grafting via UV Treatment: Comparison with Thermal Free Radical Polymerization. J Appl Polym Sci 2010, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L.; Lu, L.; Wu, G.; Chen, X.; Chen, J. Photografting Polymerization of Polyacrylamide on PHBV Films (I). J Appl Polym Sci 2007, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ke, Y.; Ren, L.; Wu, G.; Chen, X. Photografting Polymerization of Polyacrylamide on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate- Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Films. II. Wettability and Crystallization Behaviors of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate)-Graft-Polyacrylamide Films. J Appl Polym Sci 2008, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L.; Wu, G.; Xue, W. Surface Modification of PHBV Films with Different Functional Groups: Thermal Properties and in Vitro Degradation. J Appl Polym Sci 2010, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Jia, H.; Wu, G.; Xue, W.; Wang, Y. Biomimetic Ca-P Coatings on Polyacrylic Acid Modified Poly(3- Hydroxybutyrate- Co -3-Hydroxyvalerate) Films. Soft Mater 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Qu, Z.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y. Thermal and in Vitro Degradation Properties of the NH2- Containing PHBV Films. Polym Degrad Stab 2014, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Ren, L.; Zhao, Q.C.; Huang, W. Modified PHBV Scaffolds by in Situ UV Polymerization: Structural Characteristic, Mechanical Properties and Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cell Compatibility. Acta Biomater 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, L. Surface Modification of PHBV Scaffolds via UV Polymerization to Improve Hydrophilicity. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2010, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, D.P.; König, B. The Photocatalyzed Meerwein Arylation: Classic Reaction of Aryl Diazonium Salts in a New Light. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2013, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lee, T.Y. Graft Polymerization of Acrylamide onto Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Hydroxy- Valerate) Films. Polymer (Guildf) 1997, 38, 4505–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, R.J.; Rawn, J.D. 218. Ouellette, R.J.; Rawn, J.D. 21 - Carboxylic Acid Derivatives. In Organic Chemistry Study Guide; Ouellette, R.J., Rawn, J.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Boston, 2015; ISBN 978-0-12-801889-7. [Google Scholar]

- Špitalský, Z.; Lacík, I.; Lathová, E.; Janigová, I.; Chodák, I. Controlled Degradation of Polyhydroxybutyrate via Alcoholysis with Ethylene Glycol or Glycerol. Polym Degrad Stab 2006, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, G.; Sikorska, W.; Kowalczuk, M.; Montaudo, M.; Scandola, M. Sequence Distribution and Fragmentation Studies of Bacterial Copolyester Macromolecules: Characterization of PHBV Macroinitiator by Electrospray Ion-Trap Multistage Mass Spectrometry. Macromolecules 2000, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauzier, C.; Revol, J.F.; Debzi, E.M.; Marchessault, R.H. Hydrolytic Degradation of Isolated Poly(β-Hydroxybutyrate) Granules. Polymer (Guildf) 1994, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, M.A.; El-Barbary, A.A.; El-Said, K.S.; El Naggar, S.A.; ElKholy, H.M. Evaluation of Antibacterial and Anticancer Properties of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Functionalized with Different Amino Compounds. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cheng, S.; Xu, K. Block Poly(Ester-Urethane)s Based on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-Hydroxyhexanoate-Co-3-Hydroxyoctanoate). Biomaterials 2009, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, W.; Qiu, H.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. Biodegradable Block Poly(Ester-Urethane)s Based on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) Copolymers. Biomaterials 2011, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naguib, H.F.; Aziz, M.S.A.; Sherif, S.M.; Saad, G.R. Synthesis and Thermal Characterization of Poly(Ester-Ether Urethane)s Based on PHB and PCL-PEG-PCL Blocks. Journal of Polymer Research 2011, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Khomlaem, C.; Aloui, H.; Kim, B.S. Biodegradable Polyurethanes Based on Castor Oil and Poly (3-Hydroxybutyrate). Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, D.; Lv, W.; Zhang, H. Telechelic Diols from Polyhydroxybutyrate via Alcoholysis with Ethylene Glycol or Glycerol. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Machinery, Materials Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology; Atlantis Press, December 2015; pp. 259–263.

- Hirt, T.D.; Neuenschwander, P.; Suter, U.W. Telechelic Diols from Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyric Acid] and Poly{[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyric Acid]-Co-[(R)-3-Hydroxyvaleric Acid]}. Macromol Chem Phys 1996, 197, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.P.; Witholt, B.; Chang, D.; Li, Z. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Thermoplastic Polyester Containing Blocks of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxyoctanoate] and Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]. Macromolecules 2003, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liow, S.S.; Loh, X.J. Synthesis of a New Poly([R]-3-Hydroxybutyrate) RAFT Agent. Polym Chem 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.; Chan, C.M.; Colwell, J.; Pratt, S.; Laycock, B. Characterisation of End Groups of Hydroxy-Functionalised Scl-PHAs Prepared by Transesterification Using Ethylene Glycol. Polym Degrad Stab 2022, 205, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.H.; Choi, T.-R.; Yang, Y.-H.; Lee, E.Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Self-Healing Bio-Based Polyurethane from Microbial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Produced in Methanotrophs. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 281, 136533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbart, L.; Renard, E.; Langlois, V.; Guerin, P. Novel Biodegradable Copolyesters Containing Blocks of Poly(3- Hydroxyoctanoate) and Poly(ε-Caprolactone): Synthesis and Characterization. Macromol Biosci 2004, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, K.; Chen, G.Q. Synthesis, Characterization and Biocompatibility of Novel Biodegradable Poly[((R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate)-Block-(D,L-Lactide-Block- (ε-Caprolactone)] Triblock Copolymers. Polym Int 2008, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Goh, S.H.; Li, J. Hydrolytic Degradation and Protein Release Studies of Thermogelling Polyurethane Copolymers Consisting of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate], Poly(Ethylene Glycol), and Poly(Propylene Glycol). Biomaterials 2007, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawalec, M.; Adamus, G.; Kurcok, P.; Kowalczuk, M.; Foltran, I.; Focarete, M.L.; Scandola, M. Carboxylate-Induced Degradation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)s. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anslyn, E.V.; Dougherty, D.A. Organic Reaction Mechanisms, Part 1: Reactions Involving Additions and/or Eliminations. In Modern Physical Organic Chemistry; University Science, 2006; pp. 537–617 ISBN 9781891389313.

- Smith, M.B. Elimination Reactions. In March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure; John Wiley & Sons, 2020; pp. 1273–1333.

- Bunnett, J.F.; Kearley, F.J. Comparative Mobility of Halogens in Reactions of Dihalobenzenes with Potassium Amide in Ammonia. Journal of Organic Chemistry 1971, 36, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, M.; Kawalec, M.; Kurcok, P.; Kowalczuk, M.; Adamus, G. Selective Carboxylate Induced Thermal Degradation of Bacterial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) - Source of Linear Uniform 3HB4HB Oligomers. Polym Degrad Stab 2014, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Doi, Y.; Kasuya, K.I.; Inoue, Y. Visualization of Enzymatic Degradation of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] Single Crystals by an Extracellular PHB Depolymerase. Macromolecules 1997, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedliński, Z.; Kowalczuk, M.; Adamus, G.; Sikorska, W.; Rydz, J. Novel Synthesis of Functionalized Poly(3-Hydroxybutanoic Acid) and Its Copolymers. In Proceedings of the International Journal of Biological Macromolecules; 1999; Vol. 25.

- Žagar, E.; Kržan, A.; Adamus, G.; Kowalczuk, M. Sequence Distribution in Microbial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Co-Polyesters Determined by NMR and MS. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, G.; Sikorska, W.; Janeczek, H.; Kwiecień, M.; Sobota, M.; Kowalczuk, M. Novel Block Copolymers of Atactic PHB with Natural PHA for Cardiovascular Engineering: Synthesis and Characterization. Eur Polym J 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, G.; Sikorska, W.; Kowalczuk, M.; Noda, I.; Satkowski, M.M. Electrospray Ion-Trap Multistage Mass Spectrometry for Characterisation of Co-Monomer Compositional Distribution of Bacterial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) at the Molecular Level. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2003, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, F.; Reinhoudt, D.N. Stability and Reactivity of Crown-Ether Complexes. Adv Phys Org Chem 1980, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarzewicz, A.; Neugebauer, D.; Grobelny, Z. Influence of the Kind of Crown Ether on the Anionic Polymerization of (Phenoxymethyl)Oxirane Initiated by Potassium Tert-butoxide. Macromol Chem Phys 1995, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Yu, G.E.; Marchessault, R.H. Thermal Degradation of Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoates): Preparation of Well-Defined Oligomers. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Xiang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, M. Modification and Potential Application of Short-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate (SCL-PHA). Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramier, J.; Grande, D.; Langlois, V.; Renard, E. Toward the Controlled Production of Oligoesters by Microwave-Assisted Degradation of Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoate)s. Polym Degrad Stab 2012, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, R.; Santagata, G.; Corrado, I.; Pezzella, C.; Di Serio, M. In Vivo and Post-Synthesis Strategies to Enhance the Properties of PHB-Based Materials: A Review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawalec, M.; Sobota, M.; Scandola, M.; Kowalczuk, M.; Kurcok, P. A Convenient Route to PHB Macromonomers via Anionically Controlled Moderate-Temperature Degradation of PHB. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 2010, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Marchessault, R.H. Atom Transfer Radical Copolymerization of Bacterial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Macromonomers and Methyl Methacrylate. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyandin, A.N.; Bessonova, V.A.; Ertiletskaya, N.L.; Sukhanova, A.A.; Shalygina, T.A.; Kondrasenko, A.A. Aminolysis of Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate in N,N-Dimethylformamide and 1,4-Dioxane and Formation of Functionalized Oligomers. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, M.; Adamus, G.; Kowalczuk, M. Selective Reduction of PHA Biopolyesters and Their Synthetic Analogues to Corresponding PHA Oligodiols Proved by Structural Studies. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber, P.; Kwiecień, M.; Zięba, M.; Sobota, M.; Adamus, G. The Heterogeneous Selective Reduction of PHB as a Useful Method for Preparation of Oligodiols and Surface Modification. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35096–35104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, J.M.; Pilau, E.J.; Gozzo, F.C.; Felisberti, M.I. Synthesis of Polyurethane from Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(p-Dioxanone): Molar Mass Reduction via Sodium Borohydrate. In Proceedings of the Macromolecular Symposia; January 2011; Vol. 299–300, pp. 10–19.

- Rouxhet, L.; Duhoux, F.; Borecky, O.; Legras, R.; Schneider, Y.-J. Adsorption of Albumin, Collagen, and Fibronectin on the Surface of Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHB/HV) and of Poly(ε-Caprolactone) (PCL) Films Modified by an Alkaline Hydrolysis and of Poly(Ethylene Terephtalate) (PET) Track-Etched Membranes. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 1998, 9, 1279–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yun, H.; Gong, Y.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, X. Effects of Surface Modification of Poly (3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx) on Physicochemical Properties and on Interactions with MC3T3-E1 Cells. J Biomed Mater Res A 2005, 75A, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahaliloğlu, Z.; Ercan, B.; Taylor, E.N.; Chung, S.; Denkbaş, E.B.; Webster, T.J. Antibacterial Nanostructured Polyhydroxybutyrate Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2015, 11, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyandin, A.N.; Sukhanova, A.A.; Nikolaeva, E.D.; Nemtsev, I.V. Chemical Modification of Films from Biosynthetic Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate Aimed to Improvement of Their Surface Properties. Macromol Symp 2021, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, I.; Broota, P.; Rintoul, L.; Fredericks, P.; Trau, M.; Grøndahl, L. Introducing Amine Functionalities on a Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Surface: Comparing the Use of Ammonia Plasma Treatment and Ethylenediamine Aminolysis. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, K.; Chen, G.-Q. Effect of Surface Treatment on the Biocompatibility of Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, Y.; Iwata, H. Effect of Wettability and Surface Functional Groups on Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion Using Well-Defined Mixed Self-Assembled Monolayers. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3074–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinot, J.; Renard, E.; Langlois, V. Controlled Synthesis of Well Defined Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoate)s-Based Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers Using Click Chemistry. Macromol Chem Phys 2011, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinot, J.; Guigner, J.M.; Renard, E.; Langlois, V. A Micellization Study of Medium Chain Length Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoate)-Based Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers. J Colloid Interface Sci 2012, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Ni, X.; Leong, K.W. Synthesis and Characterization of New Biodegradable Amphiphilic Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-b-Poly [(R)-3-Hydroxy Butyrate]-b-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Triblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2003, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mya, K.Y.; Ni, X.; He, C.; Leong, K.W.; Li, J. Dynamic and Static Light Scattering Studies on Self-Aggregation Behavior of Biodegradable Amphiphilic Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]- Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Triblock Copolymers in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2006, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ramakrishna, S.; He, L.M.; Wu, G. Synthetic Routes to Degradable Copolymers Deriving from the Biosynthesized Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Mini Review. Express Polym Lett 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.H.; Kwon, S.H.; Kim, Y.J. Characterizations and Release Behavior of Poly [(R)-3-Hydroxy Butyrate]-Co-Methoxy Poly(Ethylene Glycol) with Various Block Ratios. Macromol Res 2008, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, K.; Ganguly, K.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Stowbridge, J.; Rudzinski, W.E.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Ultra-Small Fluorescent Bile Acid Conjugated PHB-PEG Block Copolymeric Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Cellular Uptake. RSC Adv 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, F.; Marchessault, R.H. Self-Assembly of Poly([R]-3-Hydroxybutyric Acid)-Block-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diblock Copolymers. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, M.S.; McCarthy, S.P.; Gross, R.A. Preparation and Characterization of (R)-Poly(.Beta.-Hydroxybutyrate)-Poly(.Epsilon.-Caprolactone) and (R)-Poly(.Beta.-Hydroxybutyrate)-Poly(Lactide) Degradable Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluthge, D.C.; Xu, C.; Othman, N.; Noroozi, N.; Hatzikiriakos, S.G.; Mehrkhodavandi, P. PLA–PHB–PLA Triblock Copolymers: Synthesis by Sequential Addition and Investigation of Mechanical and Rheological Properties. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 3965–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wu, Y.-L.; Lee, T.S.; Li, J. Synthesis of Novel Biodegradable Thermoresponsive Triblock Copolymers Based on Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] and Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) and Their Formation of Thermoresponsive Micelles. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Gong, J.; Sakuragi, M.; Kitajima, T.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Ito, Y. Surface Coating with a Thermoresponsive Copolymer for the Culture and Non-Enzymatic Recovery of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Macromol Biosci 2009, 9, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Cheong, W.C.D.; Li, J.; Ito, Y. Novel Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]-Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Triblock Copolymer Surface as a Culture Substrate for Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, T.D.; Neuenschwander, P.; Suter, U.W. Synthesis of Degradable, Biocompatible, and Tough Block-Copolyesterurethanes. Macromol Chem Phys 1996, 197, 4253–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, G.R.; Lee, Y.J.; Seliger, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable Poly(Ester-Urethanes) Based on Bacterial Poly(R-3-Hydroxybutyrate). J Appl Polym Sci 2001, 83, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.R.; Kuo, C.J.; Lin, Y.J. Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable Polyhydroxy Butyrate-Based Polyurethane Foams. Journal of Cellular Plastics 2003, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, G.R.; Seliger, H. Biodegradable Copolymers Based on Bacterial Poly((R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate): Thermal and Mechanical Properties and Biodegradation Behaviour. Polym Degrad Stab 2004, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Goh, S.H.; Li, J. New Biodegradable Thermogelling Copolymers Having Very Low Gelation Concentrations. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, S.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Xu, K.; Chen, G.Q. Novel Amphiphilic Poly(Ester-Urethane)s Based on Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxyalkanoate]: Synthesis, Biocompatibility and Aggregation in Aqueous Solution. Polym Int 2008, 57, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhu, W.; Xu, K. Alternative Block Polyurethanes Based on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Biomaterials 2009, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.L.; Choo, E.S.G.; Wong, S.Y.; Li, X.; He, C. Bin; Wang, J.; Li, J. Designing Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]-Based Polyurethane Block Copolymers for Electrospun Nanofiber Scaffolds with Improved Mechanical Properties and Enhanced Mineralization Capability. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2010, 114, 7489–7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, W. The Synthesis of Hydroxybutyrate-Based Block Polyurethane from Telechelic Diols with Robust Thermal and Mechanical Properties. J Chem 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.P.; Neuenschwander, P.; Hany, R.; Egli, T.; Witholt, B.; Li, Z. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Copoly(Ester-Urethane) Containing Blocks of Poly-[(R)-3-Hydroxyoctanoate] and Poly- [(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]. Macromolecules 2002, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.J.; Tan, K.K.; Li, X.; Li, J. The in Vitro Hydrolysis of Poly(Ester Urethane)s Consisting of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] and Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, X.J.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Li, J. Compositional Study and Cytotoxicity of Biodegradable Poly(Ester Urethane)s Consisting of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] and Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Materials Science and Engineering: C 2007, 27, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.X.; Gao, W.C.; Ren, X.M.; Ouyang, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wu, W.; Huang, C.X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; et al. A Review of Microphase Separation of Polyurethane: Characterization and Applications. Polym Test 2022, 107, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Korom, S.; Welti, M.; Hoerstrup, S.P.; Zünd, G.; Jung, F.J.; Neuenschwander, P.; Weder, W. Tissue Engineered Cartilage Generated from Human Trachea Using DegraPol® Scaffold. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2003, 24, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, B.; Matter, S.; Ciardelli, G.; Uhlschmid, G.K.; Welti, M.; Neuenschwander, P.; Suter, U.W. Interactions of Osteoblasts and Macrophages with Biodegradable and Highly Porous Polyesterurethane Foam and Its Degradation Products. J Biomed Mater Res 1996, 32, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Walsh, K.; Hoff, B.L.; Camci-Unal, G. Mineralization of Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, M.; Kwiecień, I.; Radecka, I.; Kannappan, V.; Morris, M.R.; Adamus, G. Biocompatible Terpolyesters Containing Polyhydroxyalkanoate and Sebacic Acid Structural Segments – Synthesis and Characterization. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 20469–20479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-C.; Yao, C.-L.; Xieh, K.-Y.; Hong, S.-G. Improvement of Physical Properties of Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) by Copolymerization with Polyhydroxybutyrate-Diols. Journal of Polymer Research 2017, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, S.S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Afshar-Taromi, F. Design and Characterization of Bio-Elastomers Containing Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Application. Life Sci 2023, 312, 121203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, Y.; Suzuki, T. Hydrolysis of Polyesters by Lipases. Nature 1977, 270, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).