2.2 Methods

2.2.1. Blend preparation

- a)

Design of Experiment

As the first step, the various formulations of blends containing three different types of PHAs were investigated to determine the optimal compositions for materials suitable for Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) 3D printing. The primary objective was to develop materials that are 100% bio-based, home-compostable, biocompatible, and flexible. For this purpose, the Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology was employed. A two-factor, five-level DoE was designed, the factors were chosen as follows:

The first factor (x

1) was PHA2-to-(PHA1 + PHA3) mass ratio (PHA2/(PHA1 + PHA3)) and second factor of the experiment (x

2) was the PHA3-to-PHA1 mass ratio.

Table 1 presents the encoded values of both factors based on their actual real values and

Table 2 present composition in encoded values of all prepared blends. The limit values in coded levels -1.141 and 1.141 correspond with the limit composition of the samples, while the mean value is located at the coded coordinate 0. The confidence interval for evaluation of results was 95%.

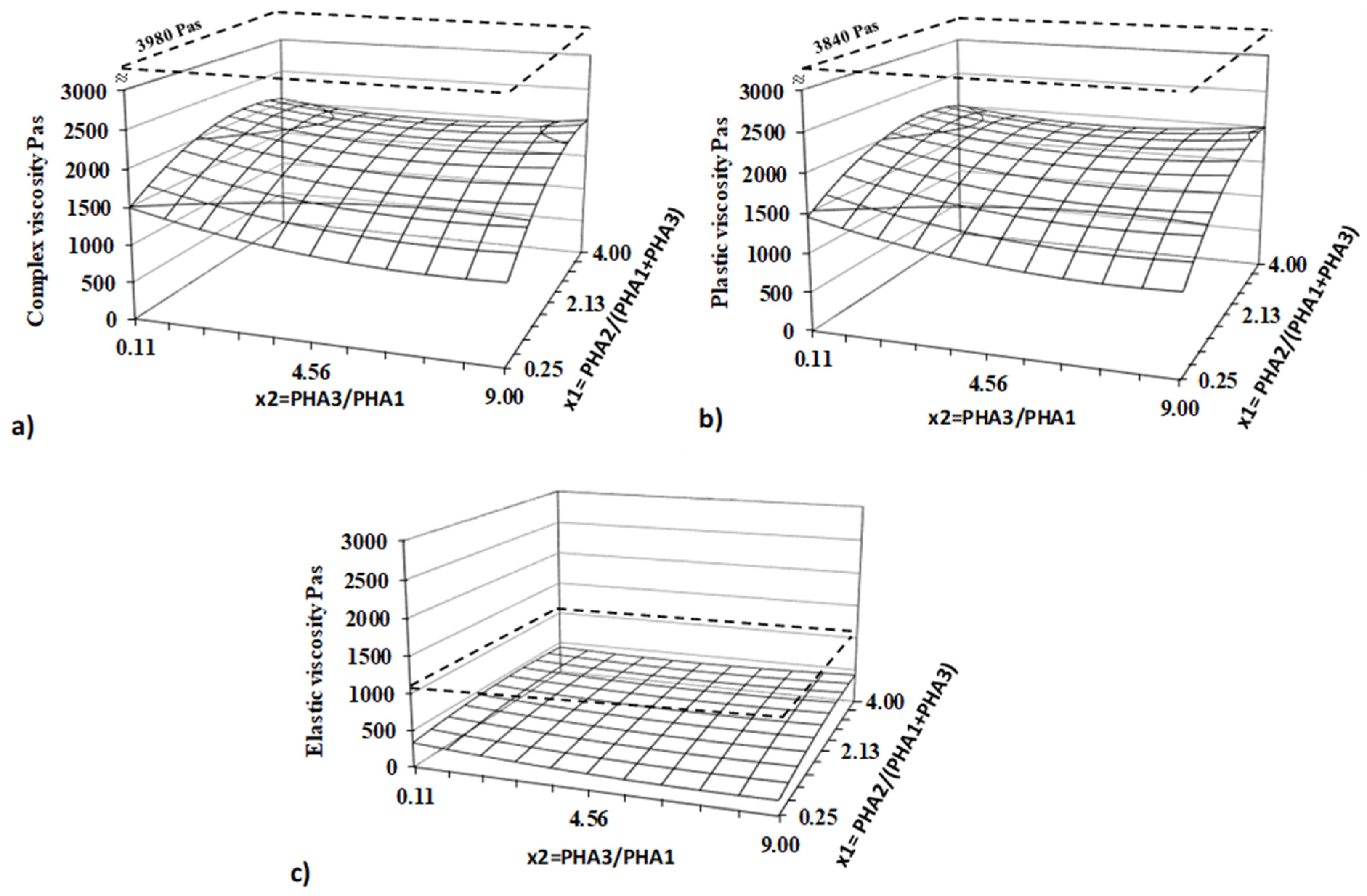

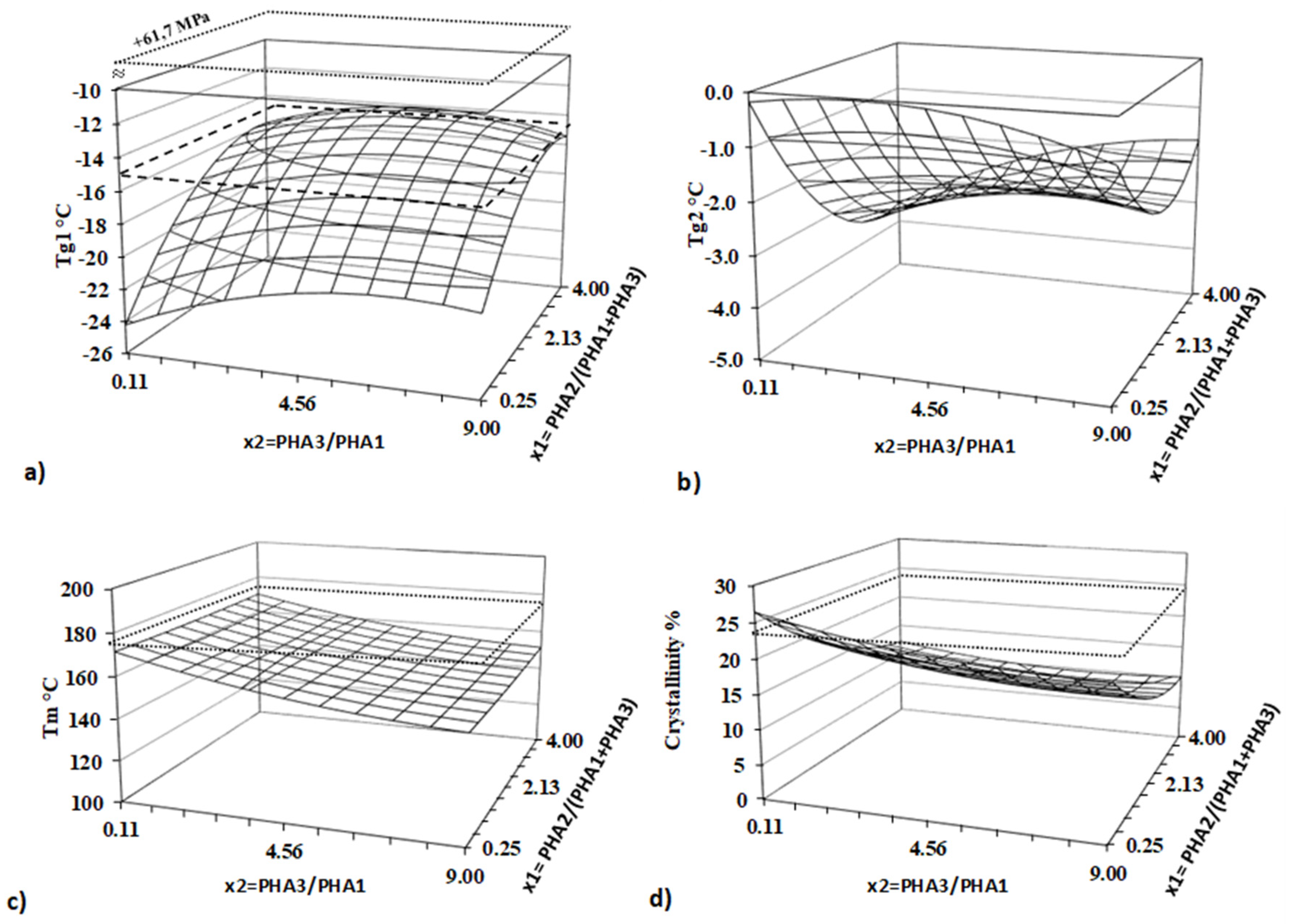

All measured and evaluated properties were analysed using the DoE methodology. The regression coefficient of Equation (1) was calculated, and an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed for the DoE.

Parameters x1 and x2 represent independent DoE factors and regression coefficients bi, bii, and bij were calculated for each property from the statistical and regression analysis together with the calculation of critical values used for statistical significance evaluation.

In general, from ANOVA analysis for all the tests in this paper, the important parameters will be discussed as follows:

F1 – Fischer – Snedecor criteria for testing of significance of linear part of equation (1) for given property

F2 – Fischer – Snedecor criteria for testing of significance of non-linear part of equation (1) for given property

FLF - Fischer – Snedecor criteria for testing of significance of equation (1) accuracy (Lack of Fit criteria)

sE+/- – experimental standard deviation

sLF+/- – Lack of fit standard deviation (inaccuracy of regression equation (1)

b) Experimental Blending

All blending components were introduced into the hopper of a laboratory twin-screw extruder (Labtech, Thailand) with a screw diameter of 16 mm and a length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio of 40. The screw geometry incorporated three kneading zones, and atmospheric venting was positioned at the 38D mark on the barrel. Extrusion was conducted at a screw speed of 150 RPM, with the temperature profile along the barrel set to 70-120-170-180-190-190-190-180-175-170°C from the hopper to the die.

The extruded melt was cooled in a water bath maintained at 20°C. After exiting the water bath, surface moisture was removed by vacuum suction, and the strand was pelletized using a pelletization cutter. The pellets were then dried in a hot air oven at 50°C for 24 hours before further processing.

2.2.2. Rheology Measurement

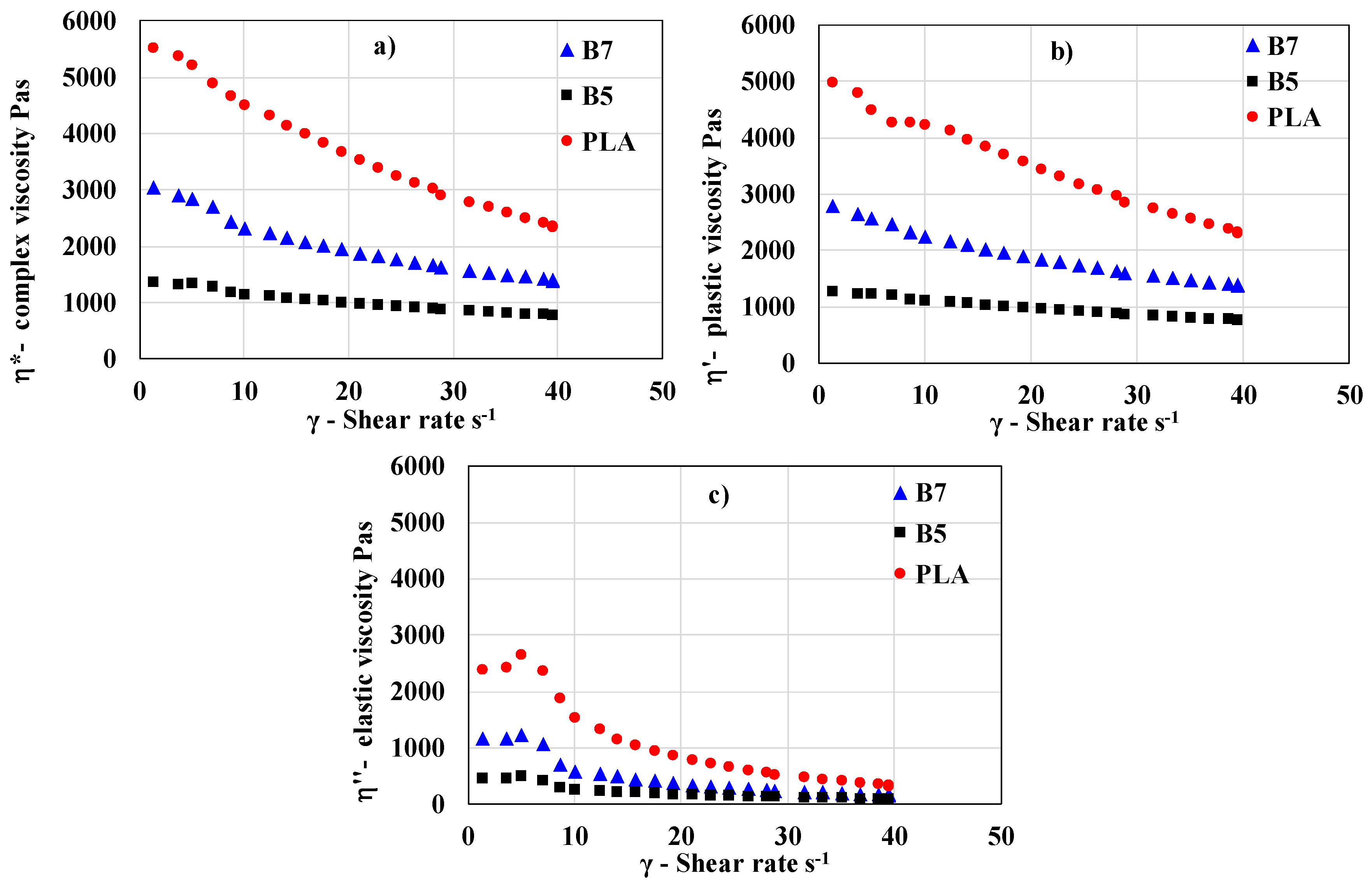

The samples were placed in the biconical chamber of the rheometer, and the testing program was initiated. After sealing the chamber, the temperature was set to 180°C, and the samples were preheated for 1.5 minutes at an oscillation angle of 6° and an oscillation frequency of 60 CPM. Following the preheating stage, the temperature was adjusted to 160°C, and the flow curve measurement began at the same oscillation frequency of 60 CPM. The oscillation angle was gradually increased from 2° to 50°, resulting in shear rates ranging from 1.34 to 40 s⁻¹. The complex viscosity was recorded using the rheometer software, and the relationships between complex viscosity and shear rate were evaluated for all samples. Thermal properties measurements

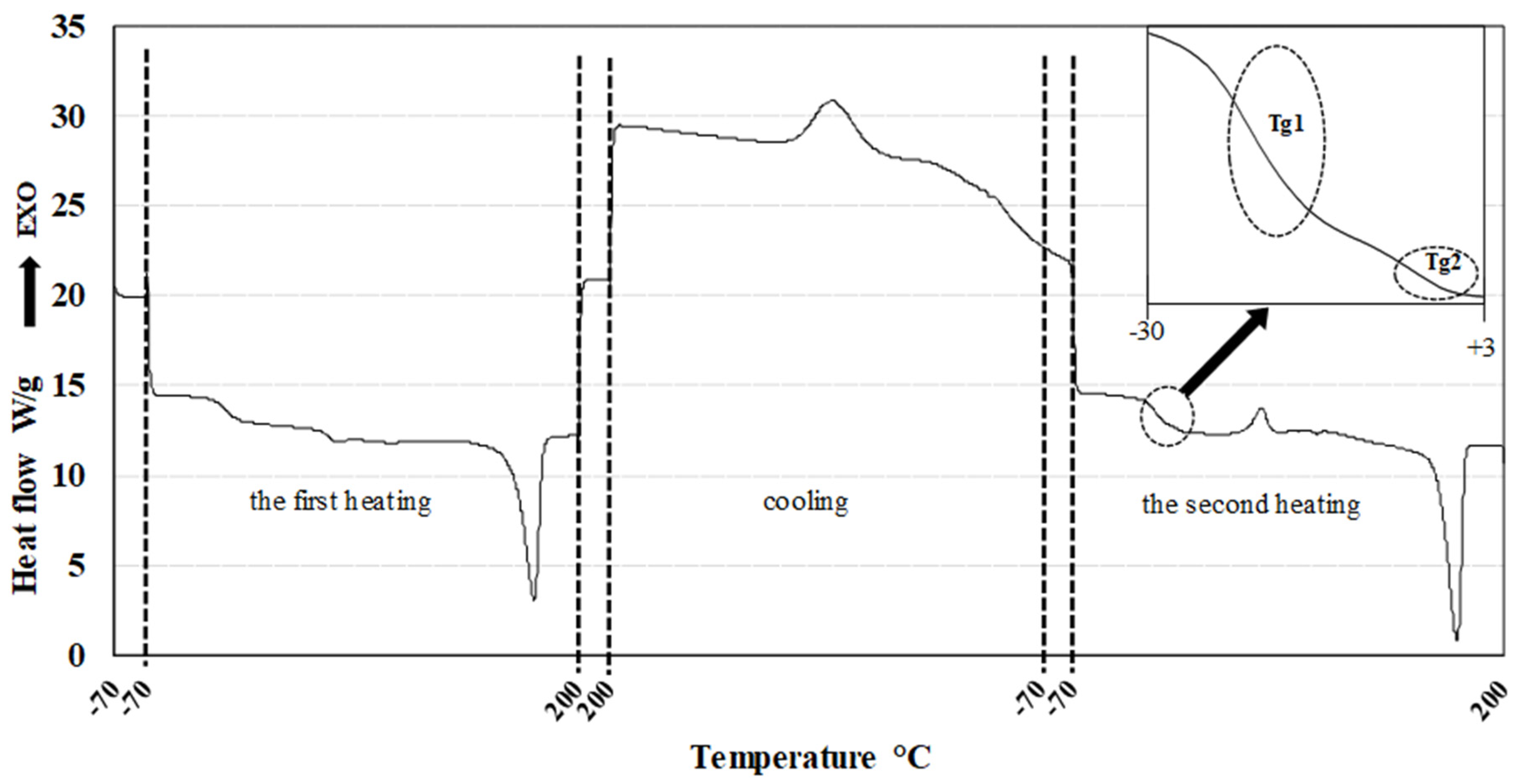

The thermal properties of all blends were determined using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 1, Mettler-Toledo Inc., USA). Key thermal characteristics, including the glass transition temperature (Tg), crystallization temperature (Tc), and melting temperature (Tm), were evaluated from measurements conducted on blend pellets..

A sample weighing 10–15 mg was placed in a standard aluminum pan and inserted into the measurement chamber, while an empty aluminum pan was used as a reference. Nitrogen was employed as the inert gas with a flow rate of 50 mL/min. The measurement protocol was as follows:

Isothermal hold at -70°C for 3 min

First heating cycle: -70°C to +200°C at a heating rate of 10 K/min

Isothermal hold at +200°C for 3 min

Cooling cycle: +200°C to -70°C at a cooling rate of 10 K/min

Isothermal hold at -70°C for 3 min

Second heating cycle: -70°C to +200°C at a heating rate of 10 K/min

The heat flow dependency on temperature was recorded as the output of the measurement. All investigated thermal parameters were analyzed using DSC curves, processed with the SW STARe 16.40 evaluation software (Mettler-Toledo Inc.). Flow curves for all samples were recorded at 160°C. Complex viscosity as well as plastic and elastic part of viscosity were evaluated for all 13 blends and PLA standard.

2.2.3. Preparation of Filaments for 3D Printing

Filaments suitable for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printing were produced from pre-dried pellets using a single-screw extruder (Plasticorder Brabender, Germany). The extruder was equipped with a 19 mm diameter screw, an L/D ratio of 25, and a compression ratio of 1:2. The extrusion process was conducted at a screw speed of 20 RPM, with a barrel temperature profile ranging from 160°C to 190°C (from the hopper to the die).

The extruder head was fitted with a round die of 2.0 mm diameter, and the extruded filaments were cooled in a water bath maintained at 45°C. The filament diameter was regulated through a variable pulling speed on the pull-off device, ensuring a final filament diameter of 1.75 mm ± 0.15 mm.

2.2.4. 3D Printing Procedure

All prepared samples in filament form were tested for 3D printability, and all specimens for mechanical testing were fabricated using 3D printing technology. For this purpose, an FDM 3D printer (Ender 3, Creality, China) was employed. The printer was modified to enable printing with elastic filaments, featuring a direct-drive extruder and a dual 4010 cooling fan.

All samples were printed using a standard 0.4 mm nozzle on a textured PEI print bed, which was not heated during the printing process (resulting in a bed temperature range of 23-29°C). 3D lac spray was applied to enhance bed adhesion when necessary.

The print parameters were as follows:

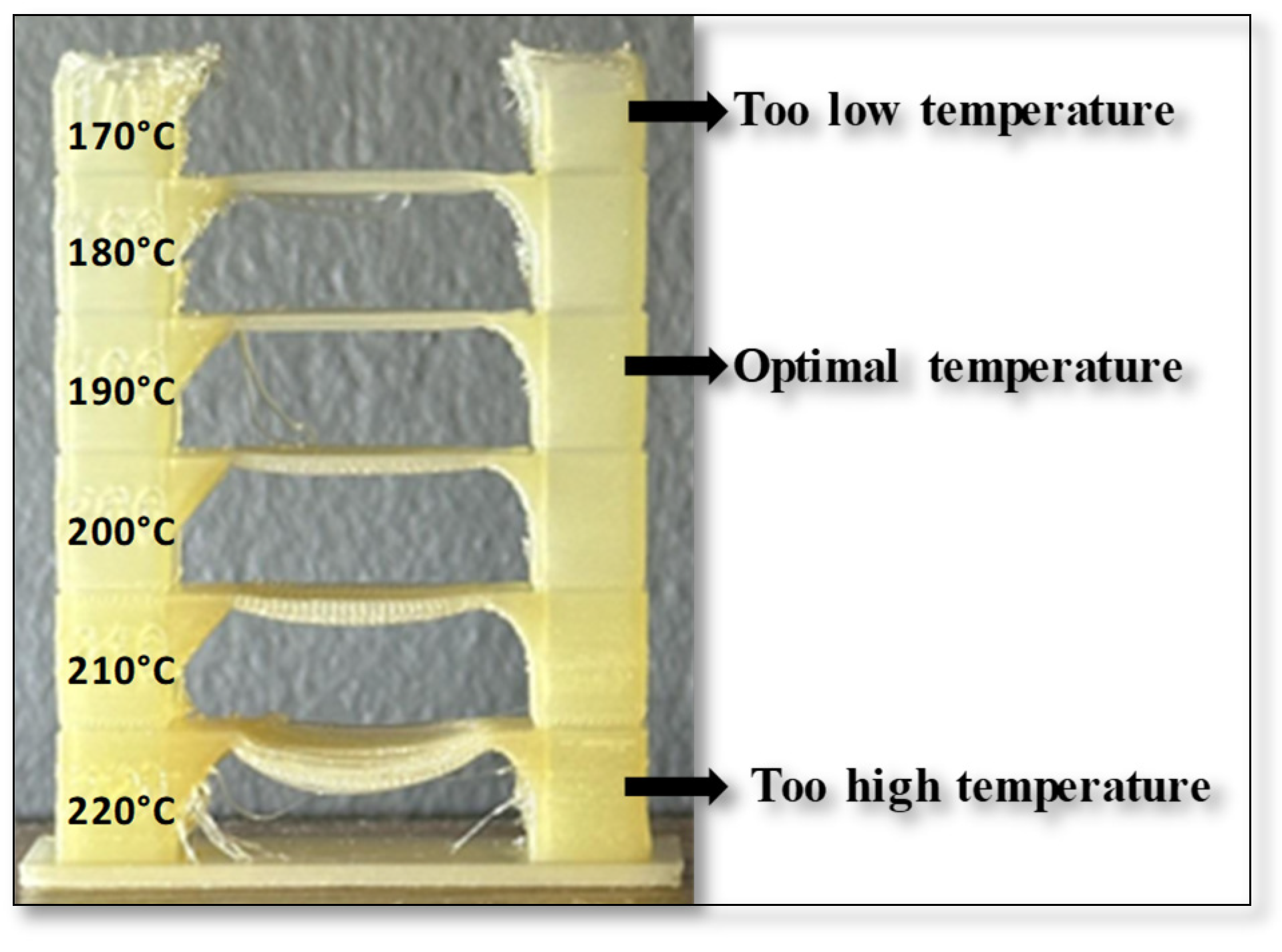

Each sample was 3D printed at optimal temperature, determined through temperature tower printing. Using FDM technology, temperature towers were printed for each biodegradable PHA polymer blend. For each material, a temperature tower was fabricated within a temperature range of 220°C to 170°C, with a temperature gradient of 10°C per printed layer (

Figure 15). The optimal printing temperature and overall print quality were assessed by analyzing geometric features such as interlayer bridges, overhangs, and the rounding of the outer wall.

The temperature tower consists of multiple levels, with each level printed at a different temperature. The first level was printed at 220°C, and each subsequent level was printed at a temperature 10°C lower until a printing temperature of 170°C was reached. The quality of each level was visually inspected, and the optimal printing temperature for the polymer blend was determined based on the best-performing level. The design of the temperature tower is shown in

Figure 1.

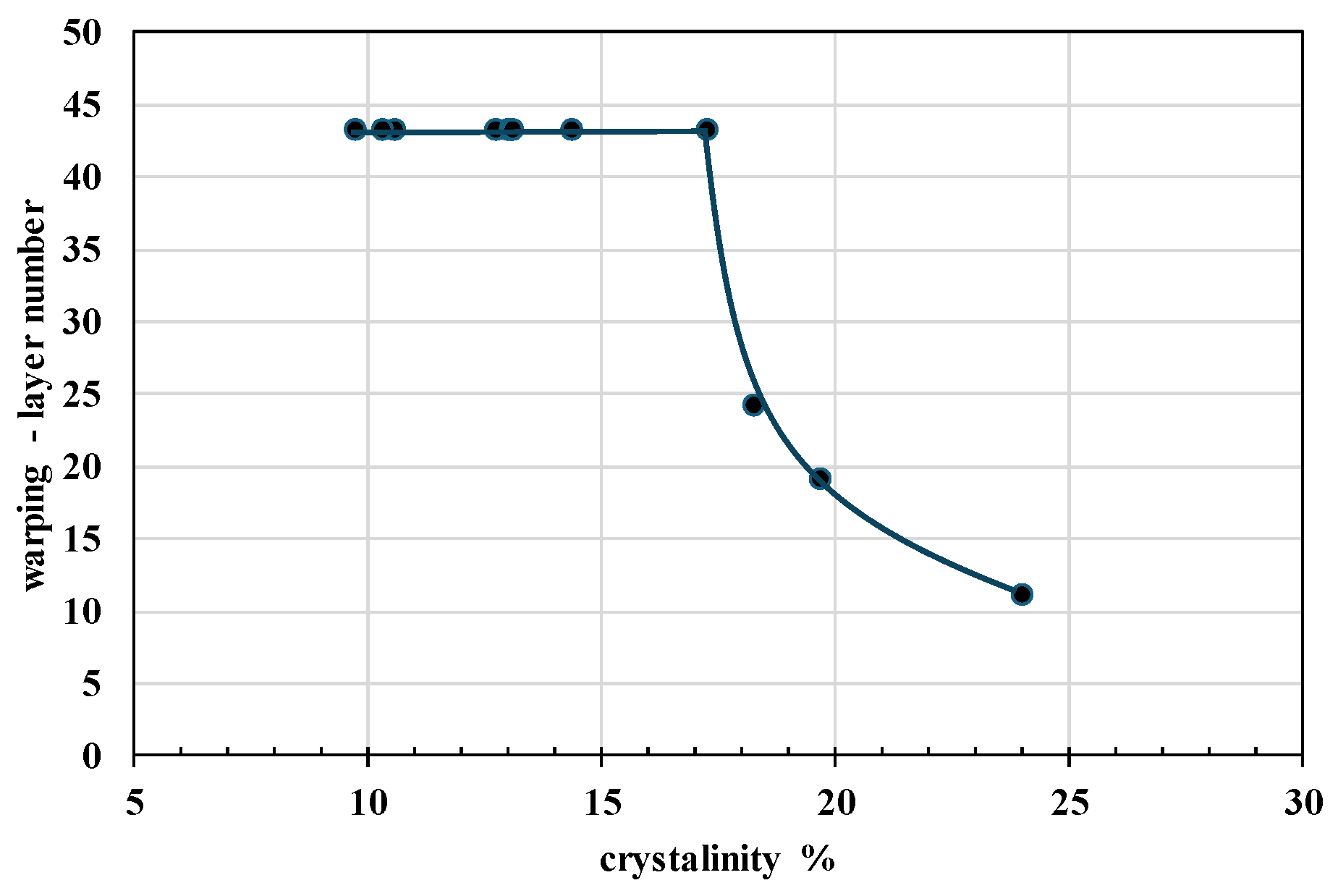

2.2.5. Warping Test

The warping tendency of each prepared sample was evaluated by 3D printing a specially designed test object (

Figure 2) with a low contact surface at the optimal printing temperature. The printed object had a triangular cross-section prism shape, with an apex angle of 60° and a prism length of 6 cm.

The printing procedure was as follows:

The first layer, with a width of 0.4 mm and a thickness of 0.2 mm, was applied to the bed, forming the apex of the triangular cross-section of the prism.

Each subsequent layer was wider, ensuring that the apex angle remained at 60°.

The height of each printed layer was 0.2 mm

With each additional layer, the bending force acting on the bottom layer, due to the volumetric shrinkage of the cooled material, caused the edges of the prism to lift away from the build plate (bed). The printing process was monitored to determine at which layer the edges of the bottom layer detached from the bed. No warping effect was observed if the number of layers reached the maximum (43 layers) without detaching the edges of the bottom of the prism from the bed.

After each printing procedure, the build plate was thoroughly cleaned with water and degreased with isopropanol (IPA). The warping effect was evaluated based on the number of printed layers at which the first detachment from the bed was observed.

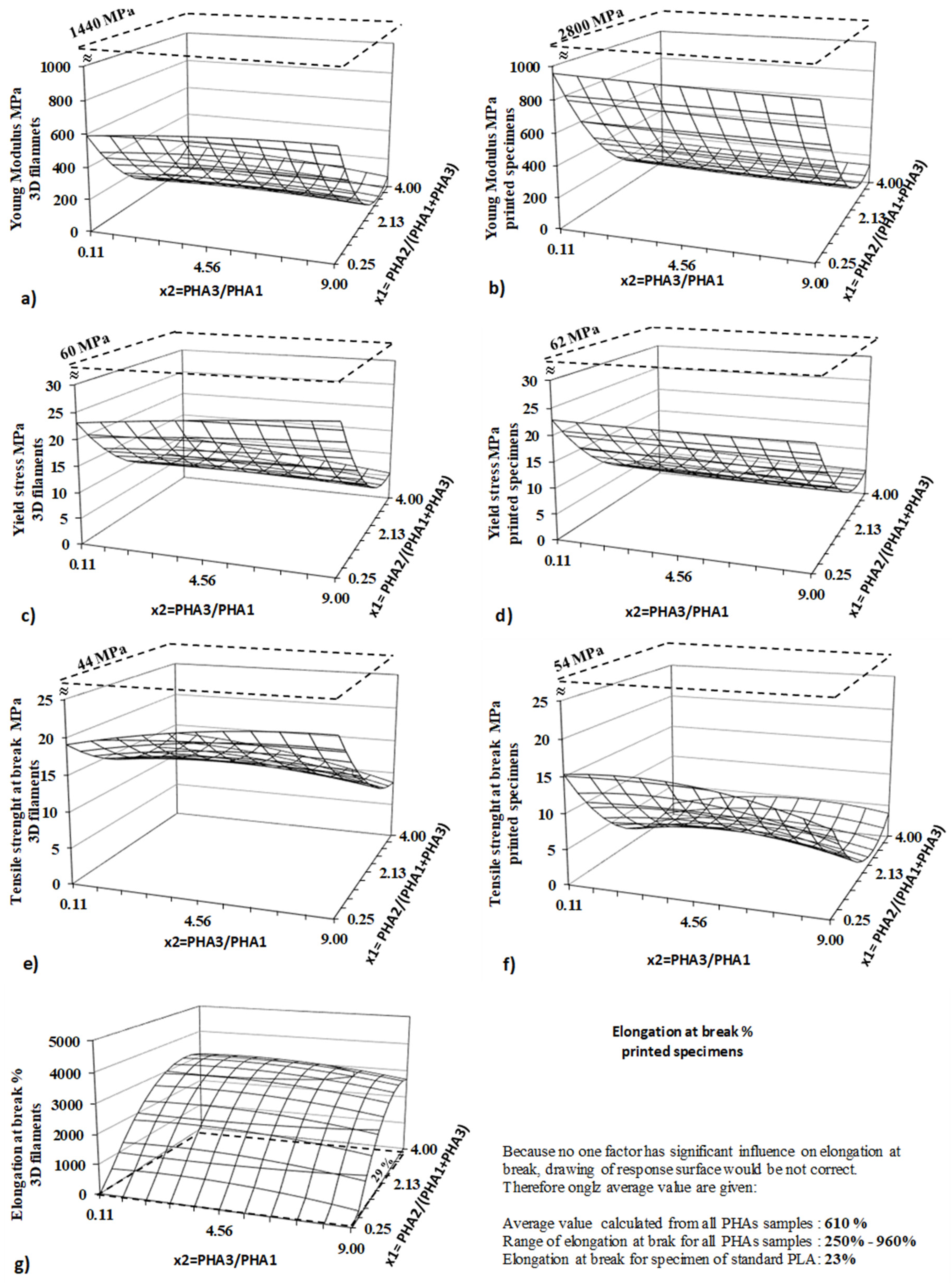

2.2.6. Tensile Test

For the test, dog-bone tensile bars (STN ISO 37, Type 2) were 3D printed using an FDM 3D printer. For each polymer blend, 8 tensile bars were printed at the optimal printing temperature with a layer height of 0.2 mm. Each sample was then tested using a universal testing machine (Zwick Roell, Germany) according to STN ISO 37 standards. The grip separation was set to 50 mm, with the contact extensometer working distance set to 30 mm. The cross-head speed was set to 50 mm/min. Yield stress, tensile strength at break, Young’s modulus, and tensile strength at break were evaluated from the tensile curves.

Tensile tests were also conducted on 3D filaments. The same universal testing machine was used for testing the filaments as for the tensile bars. The grip separation was set to 20 mm, with a cross-head speed of 50 mm/min. Elongation was determined from the grip separation at the point of break.

2.2.7. Bending Test

For the determination of Young’s modulus in bending mode (flexural modulus), the three-point bending test was applied according to ISO 178. The specimens, in a bar shape, were printed using an FDM 3D printer at the optimal temperature, with dimensions of 80 x 10 x 4 mm. The three-point bending test was performed on a universal testing machine (Zwick Roell, Germany) by ISO 178. The distance between the support points was set to 64 mm, and the load was applied using a load pin at the center of the span, with a cross-head speed of 5 mm/min. During the test, the stress-strain dependency of the specimen was recorded, and the flexural modulus was determined according to the ISO 178 standard.

2.2.8. Hardness Testing

The same specimens used for the bending test were employed for hardness measurements according to ISO 868. For each sample, 3 measurements were performed on each of the 8 specimens, resulting in a total of 24 measurements. The hardness was measured using the Shore D scale.

2.2.9. Impact Strength Testing

The same 3D printed bars used for the bending and hardness tests, with dimensions of 80 x 10 x 4 mm, were utilized for Charpy impact strength testing according to ISO 179. For each polymer blend, 5 bars were printed at the optimal printing temperature with a layer height of 0.2 mm. The test was performed using an impact pendulum tester (Instron, USA). The specimens were unnotched, and before testing, all specimens were cooled to -30°C for 30 minutes. The potential energy of the pendulum used was 5 J.

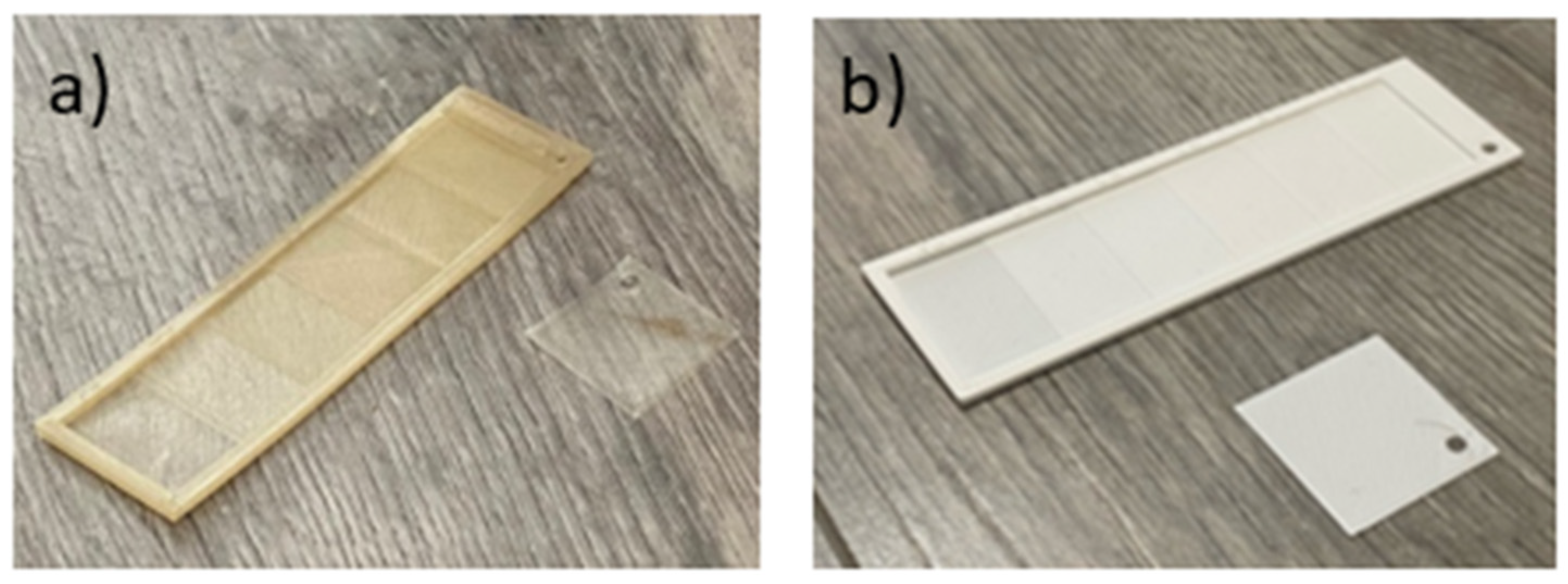

2.2.10. Home Composability in Real Conditions

The composability test was conducted under real conditions using a home compost system. Specially designed with varying wall thicknesses (increasing from 0.2 mm to 1.2 mm) and a sample with a thickness of 0.2 mm in a square shape were 3D printed from selected polymer blends as well as from standard PLA for reference (The slicer models of the 3 printed specimens are shown in

Figure 3a and b.

Each specimen was placed separately in a perforated cage with dimensions of 20 x 20 x 20 cm (

Figure 3c), along with a specific marker for identification. The specimens were positioned in the center of the cage, surrounded by substrate from a home composter (

Figure 3d). These cages were then evenly distributed in a regular composter (dimensions: 1x1x1 m), placed at the middle height, and surrounded by the same substrate (

Figure 3e). The composter was left outdoors in the garden, uncovered.

Each week, fresh vegetable scraps and cut-offs were added to the composter and incorporated into the substrate. If the top layer became dry, the composter was thoroughly watered. The composting process took place over two months, with average temperatures ranging from 0 to 15°C at night and 10 to 20°C during the day.

At the end of the experiment, the specimens were carefully removed from the compost and cleaned under water. Decomposition was evaluated visually, and surface destruction was analysed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2.2.11. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy was used for surface observation of samples before and after the home compostability test. Surface changes on the tested specimens before and after composting were observed using JEOL F 7500 SEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Samples were coated by a gold/platinum alloy using Balzers SCD 050 sputtering equipment.

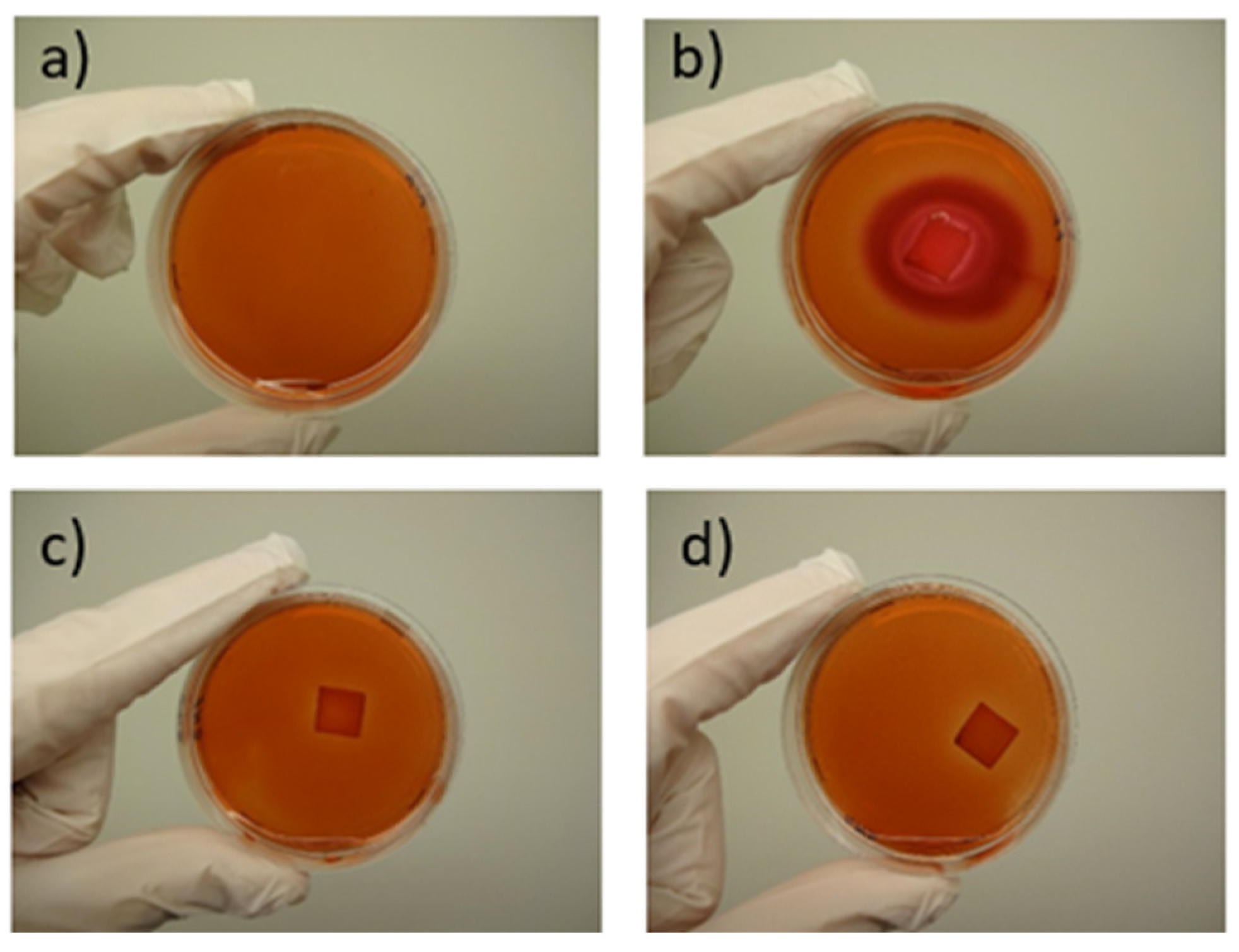

2.2.12. Cytotoxicity Testing

The agar diffusion test was performed in accordance with the ISO 10993-5 standard to evaluate cytotoxicity. Gingival fibroblasts (GFs) were seeded as a suspension at a concentration of approximately 0.5 × 10⁶ cells per Petri dish in sterile 60 mm Petri dishes. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 6% CO₂ atmosphere until they reached confluence.

Once confluence was achieved, the culture medium was aspirated, and the scaffolds, along with the negative and positive controls, were placed at the center of each Petri dish. The negative control consisted of cells without a matrix, while the positive control was a piece of sterile gauze (1 × 1 cm) moistened with a 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution. The samples and controls were subsequently covered with 4 mL of agar medium, composed of 1% agar in DMEM with 2% FBS, and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours.

After incubation, the cells were stained with 1% agar containing 0.2% neutral red. The samples were tested in triplicate, and the cytotoxicity was evaluated at 24 and 48 hours based on cellular uptake of neutral red. This dye preferentially stains the acidic regions of viable cells, particularly lysosomes, resulting in red coloration. The cytotoxicity of the scaffolds was assessed by measuring the width of the unstained zone around the samples, which corresponds to areas where cell membranes were compromised. The response index was calculated as the ratio of the zone index to the lysis index.

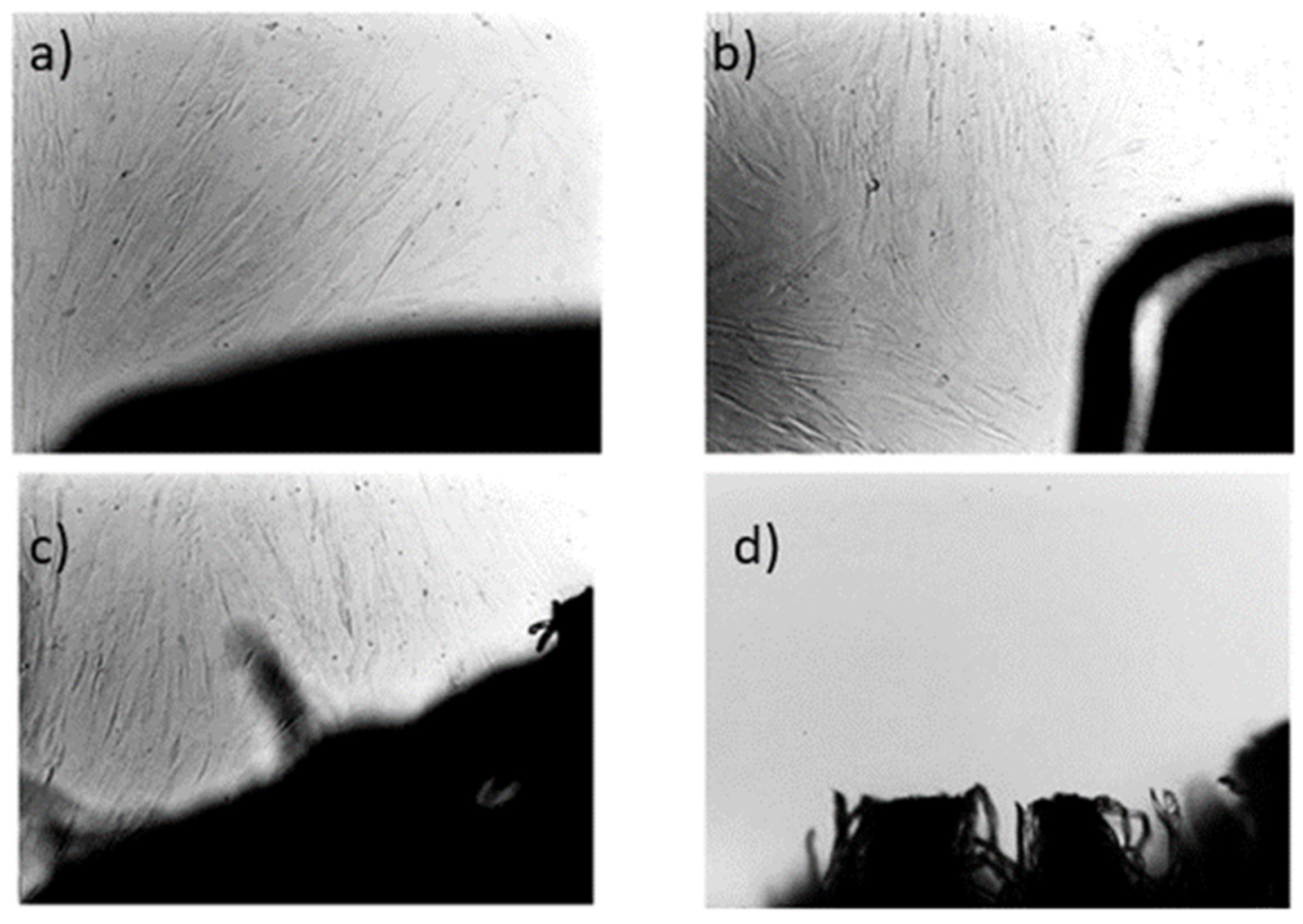

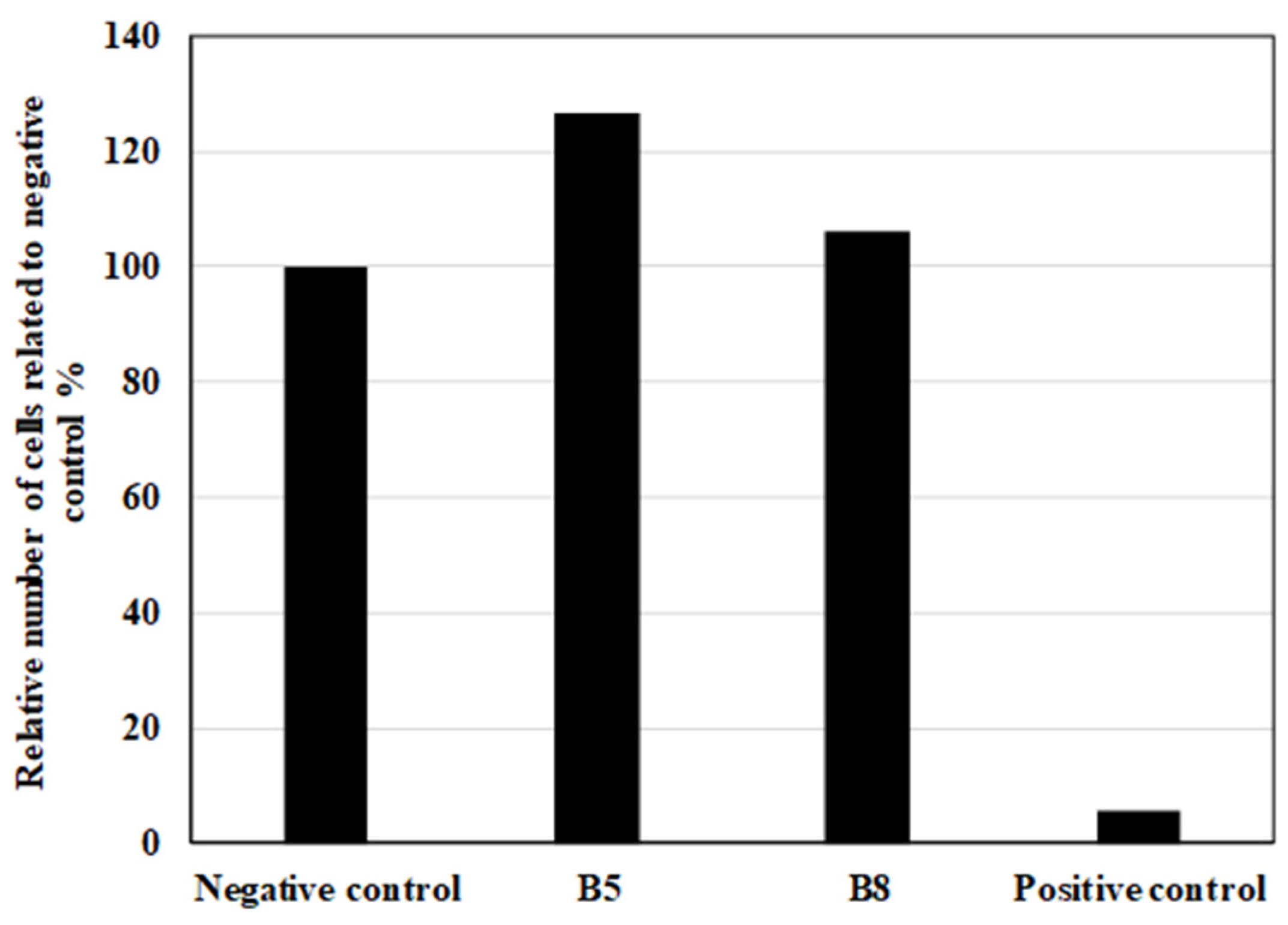

2.2.13. Contact Toxicity Testing (TCT)

Contact toxicity testing was conducted according to the ISO 10993-5 standard. A cell suspension of gingival fibroblasts (GFs) was prepared at a concentration of 0.5 × 10⁵ cells/mL. The polymer scaffolds, fabricated via 3D printing, were sterilized by UV radiation before testing. Each scaffold was placed at the center of a sterile 60 mm Petri dish and fixed in place with a sterile U-shaped glass. To each Petri dish, 1 mL of the cell suspension and 4 mL of DMEM were added.

Cell morphology was observed daily under an inverted microscope. At the end of the experiment, the cells were trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA, and the cell count was determined using a Bürker counting chamber. For evaluating cell proliferation in the presence of the tested polymer samples, negative and positive controls were included. The negative control (NC) consisted of a 1 × 1 cm sterile gauze piece, while the positive control (PC) was a sterile gauze piece moistened with a 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution. Each sample was tested in triplicate.