1. Introduction

Proteins exhibit remarkable versatility, performing various functions in biological systems with a wide range of applications including therapeutics. However, using proteins outside their natural environments presents significant challenges including chemical stability issues due to protease activity, as well as complex supply chain requirements such as the need for refrigeration for many protein-based therapeutics and vaccines. Additionally, the large-scale synthesis and purification of proteins are often energy-intensive, can have high waste levels and can be difficult to scale up production. There is a growing interest is in developing complex macromolecular assemblies that combine proteins with other synthetic materials to address the intrinsic limitations of proteins. These macromolecular assemblies offer enhanced chemical tunability beyond what is possible with traditional protein modification strategies [

1].

Creating synthetic materials that mimic the functional complexity of proteins requires a synergistic approach, combining multiple material types to form these composite macromolecules. Synthetic macromolecules can self-assemble on various length scales, from nanometres to micrometres, via single-chain folding and multichain assembly processes. Although synthetic macromolecules do not possess the same degree of structural control as proteins, they offer advantages in terms of scalability, stability, and chemical diversity [

2,

3]. Recent advances, such as controlled polymerisations and efficient macromolecule conjugation reactions, have expanded the toolkit for creating these new hybrid materials. For example, controlled radical polymerisations allow the production of low polydispersity polymers with versatile end groups suitable for post-polymerization modifications. Coupling reactions, such as Diels-Alder reactions and click chemistry reactions, enable the efficient assembly of building blocks, including protein fragments or polymer chain ends. These methodologies facilitate the creation of hybrid materials, which blend natural and synthetic components. Furthermore, advances in architectural control enable the design of synthetic assemblies with well-defined structures, imparting bioinspired functionalities such as catalysis, protection and transport of small molecules, directed mineralisation, and responsiveness to environmental stimuli.

One prominent class of protein-mimetic self-assemblies is the aqueous solution-phase assembly of peptides. Peptides, composed of multiple amino acid monomers linked by peptide bonds in a specific sequence, are common in living organisms and play crucial biological roles. Through molecular design and peptide synthesis, numerous peptides with distinct structures and functions can be produced, facilitating the exploration of different self-assembly and optimising assembly conditions. Self-assembling peptides can form nanostructures with enhanced stability by utilising intramolecular free energy to drive the assembly process. These new nanostructures have significant implications for biomedicine [

4,

5]. For example, Ghadiri et al. pioneered the use of self-assembly technology to create nanotubes from synthesised cyclic polypeptides into peptide nanotubes [

6]. Subsequently, the discovery of self-assembling ionic peptides by the Zhang group sparked considerable interest in peptide self-assembly and its applications in drug delivery and biomedical fields [

7]. In summary, following the introduction of the molecular self-assembly concept, it has earned significant scientific interest. Continuous efforts across various disciplines have shown that self-assembled peptides can aid in studying complex biological phenomena and enable diverse applications.

2. Classification of Self-Assembled Peptides

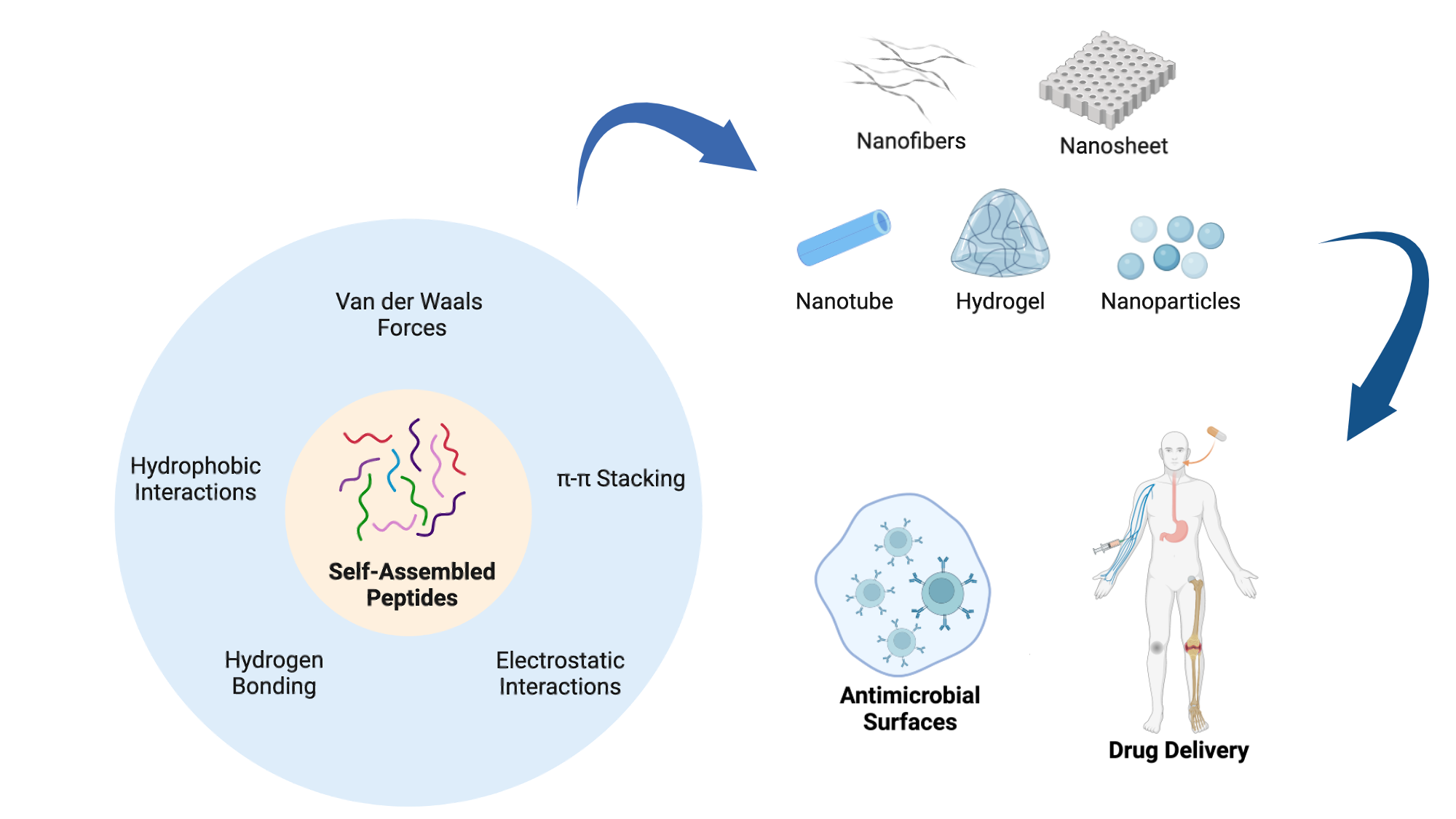

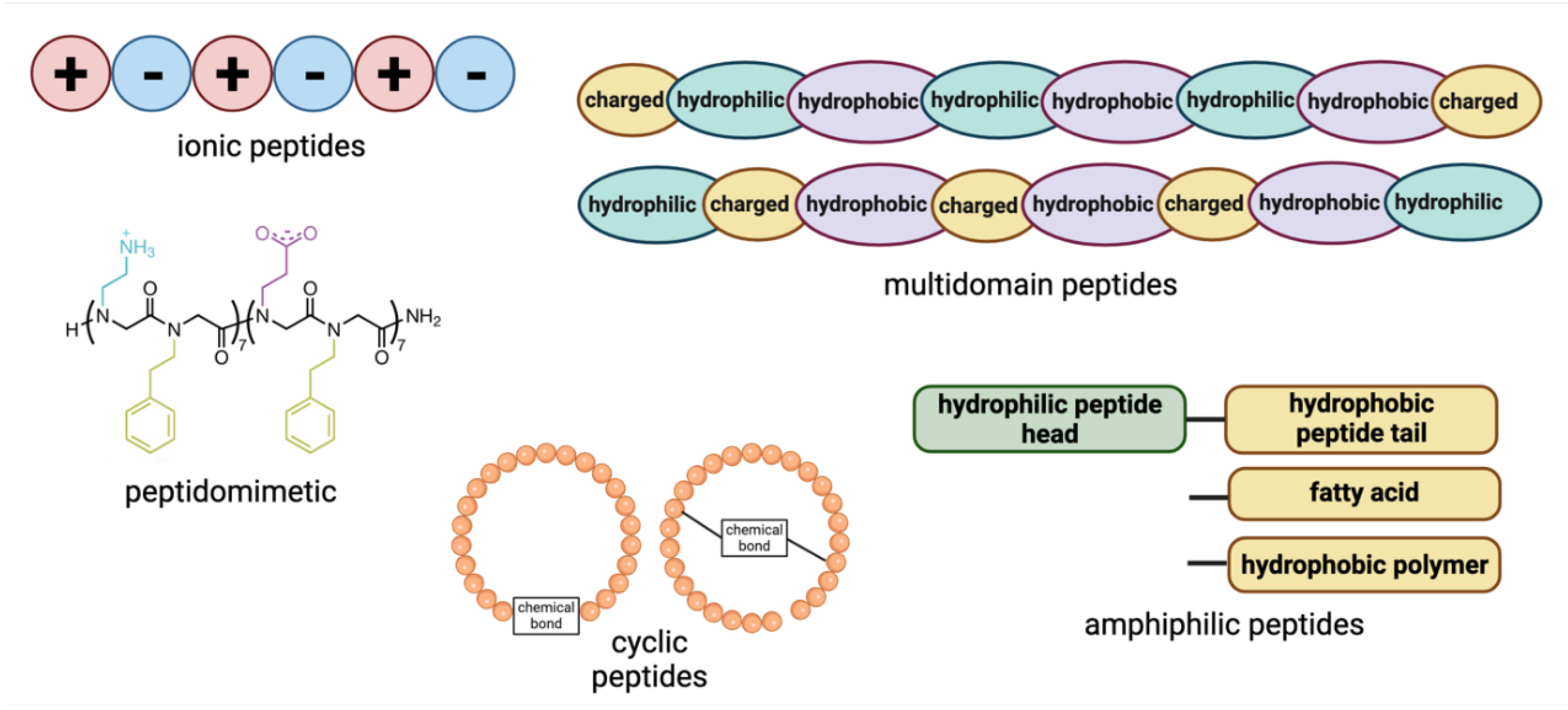

Peptide self-assembly can occur spontaneously or be induced under specific solution conditions. Like other macromolecules, peptide self-assembly predominantly relies on non-covalent intermolecular interactions. The driving forces behind peptide self-assembly are primarily determined by the physico-chemical characteristics of the amino acids within the peptide and its sequence. These forces include hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions and van der Waals forces and often coexist within aggregates, with certain forces dominating [

8]. Broadly, peptides can be classified into different categories as outlined below (

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

2.1. Ionic Peptides

Ionic peptides are a class of peptides with an alternating arrangement of negatively and positively charged residues, leading to electrostatic interactions that drive self-assembly, along with hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces. These peptides can form stable β-sheet structures in aqueous solutions, making them valuable in designing biomaterials that mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM). Due to their pure amino acid composition and sol-gel transition properties, they have gained significant attention in biomaterials science and regenerative medicine [

9]. For instance, Yang et al. used the ionic complementary peptide EFK16-II to modify electrodes for glucose biosensing, demonstrating its potential in biocompatible interfaces for molecular sensing [

10]. Wan et al. studied EAK16-II-derived peptides, revealing that peptide length and the amino acid arrangements influence the morphology and anticancer activity of peptide-drug complexes [

11].

2.2. Amphiphilic Peptides

Peptide amphiphiles (PAs) consist of hydrophilic bioactive sequences linked to hydrophobic regions, such as fatty acid lipids or hydrophobic amino acid chains or synthetic polymers. These peptides self-assemble into structures with specific morphologies and sizes driven by intermolecular hydrophobic interactions [

12,

13]. Diverse structures of proteins across different length scales, from intrachain folding to the complex assembly of multiple protein units, are driven by the precise sequences of amino acids. Similarly, PAs, which consist of peptides coupled to synthetic hydrophobic tails, mimic this versatility by offering tunable structures and multichain assembly behaviour. Synthetic methods, including solid-phase peptide synthesis, enable precise control over amino acid sequences, allowing for the strategic placement of functional groups. Typically, PAs feature diblock or triblock structures with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments.

Amphiphilic peptides can be further divided into some subcategories, including surfactant-like peptides, bolaamphiphilic peptides, and lipidated peptides, depending on the number of hydrophilic groups, and the composition of hydrophobic region. Surfactant-like peptides contain either positively charged or negatively charged amino acids in the hydrophilic head linked to the hydrophobic tail, such as Ac-A

6K

2, Ac-V

6K, and Ac-A

6D [

14,

15]. This structure enables the peptides to self-assemble in aqueous solution with hydrophobic groups orientating away from the water molecules in the formation of different nanostructures. In contrast to surfactant-like peptides, which typically feature one single polar head group in the structure, bolaamphiphilic peptides, or bolaforms, are characterised by the presence of two polar head groups connected by a hydrophobic spacer. Lipidated self-assembling peptides contain peptide sequences modified with hydrophobic lipid chains which facilitate the formation of secondary structures and enable the self-assembly into a range of well-defined morphologies. The most commonly investigated lipidated peptides feature a single alkyl chain attached to the N-terminus, which allows for the attachment of various bioactive ligands at the C-terminus, expanding their functional applications [

16,

17]. For instance, lipopeptides C

16IKPEAP and C

16IKPEAPG which are derived from gastrointestinal peptide hormone PYY3−36 can self-assemble into micelles, and further develop into β-sheet amyloid fibrils when deprived of water [

18].

Similar to traditional surfactants and lipids, many of these amphiphilic peptides also have a defined critical aggregation concentration (CAC), above which the peptides will self-assemble into various nanostructures depending on solution pH, temperature, and ionic strength [

19,

20]. For example, Mondal et al. designed a cationic bolaform, which formed elongated micelles with a relatively low CAC due to its hydroxyl functionality and demonstrated good gene transfection efficiency despite their strong DNA-binding affinity [

21].

2.3. Peptidomimetics

Synthetic peptides or peptidomimetics, including peptoids, are gaining significant attention in materials science, nanotechnology, medicine, and biomedical engineering for their stable and intriguing self-assembled structures.

The synthesis of functional two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, especially polymer- and protein-based varieties, is gaining prominence across diverse applications. Peptoids, which are protein-mimetic polymers, exhibit potential for constructing 2D nanostructures applicable in molecular recognition, catalysis, membranes, and nanoparticle assembly. Recently discovered peptoid nanosheets form through a distinctive monolayer collapse mechanisms at either the air-water or the oil-water interface. Chemical modifications to the peptoid sequence affect nanosheet formation, presenting challenges in maintaining the necessary hydrophobicity for interfacial adsorption. Peptoids featuring alternative sequences of ionic and hydrophobic monomers which spontaneously adsorb at the liquid-air interface, creating a highly ordered monolayer intermediate in a dilute aqueous solution. Compression of these surfaces layers induces monolayer buckling and collapse into a bilayer in the aqueous phase, with the hydrophobic groups forming an interior core and ionic groups exposed on the surface. To assess the chemical modification tolerance for nanosheet formation, the Zuckermann group systematically examined chemical analogues of prototype sheet-forming peptoids. Decreasing the peptoid hydrophobicity may disrupt nanosheet formation, affecting interfacial adsorption, while an increase in peptoid hydrophobicity may result in unwanted aggregation. Recent studies, however, reveal that the ability to form a monolayer is not the sole requirement for nanosheet formation [

22].

2.4. Cyclic Peptides

Cyclic peptides are commonly found in natural products, sometimes offering a range of pharmacological activities. Compared to linear peptides, cyclic peptides often show higher binding affinity, improved protease stability, and enhanced cellular uptake. They can be classified based on their origin, physicochemical properties, and conformation. Zhang et al. demonstrated the efficient synthesis of cyclic peptides using ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA)-amine-thiol reactions, offering a new tool for constructing DNA-encoded peptide libraries [

23]. Shirazi et al. synthesised a peptide-based cyclic [WH]5 drug delivery system that improved the cellular uptake of cell-impermeable cargo [

24].

2.5. Multidomain Peptides

Multidomain peptides (MDPs) consist of hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and charged regions that can drive their self-assembly into nanofibers by eliminating water from the hydrophobic core and forming hydrogen-bonding networks [

25]. Their structural properties can be tuned by manipulating the electrostatic interactions between the peptides, including changes in the solution ionic strength, pH and salt concentration of the solvent, allowing the formation of hydrogels that are shear recoverable [

26,

27]. MDPs have demonstrated antimicrobial properties and can be tailored to exhibit a range of biological functions through structural modifications. For instance, Wickremasinghe et al. demonstrated that MDP nanofibers, when combined with growth-factor-loaded liposomes, can create composite hydrogels that enable time-controlled release of placental growth factor-1 (PlGF-1) [

28]. It was demonstrated that these MDP-liposome hydrogels offered enhanced angiogenic responses and promoted vessel regeneration, offering a biocompatible platform for drug delivery and potential treatments for ischemic tissue diseases.

The classification provided above is a broad approach to categorising self-assembled peptides, primarily based on structural attributes such as hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and charged domains. However, numerous other classification systems exist due to overlapping and complex characteristics and multifunctional behaviours of SAPs. For instance, SAPs can also be grouped according to their self-assembly mechanisms, peptide length, or biofunctional roles [

29]

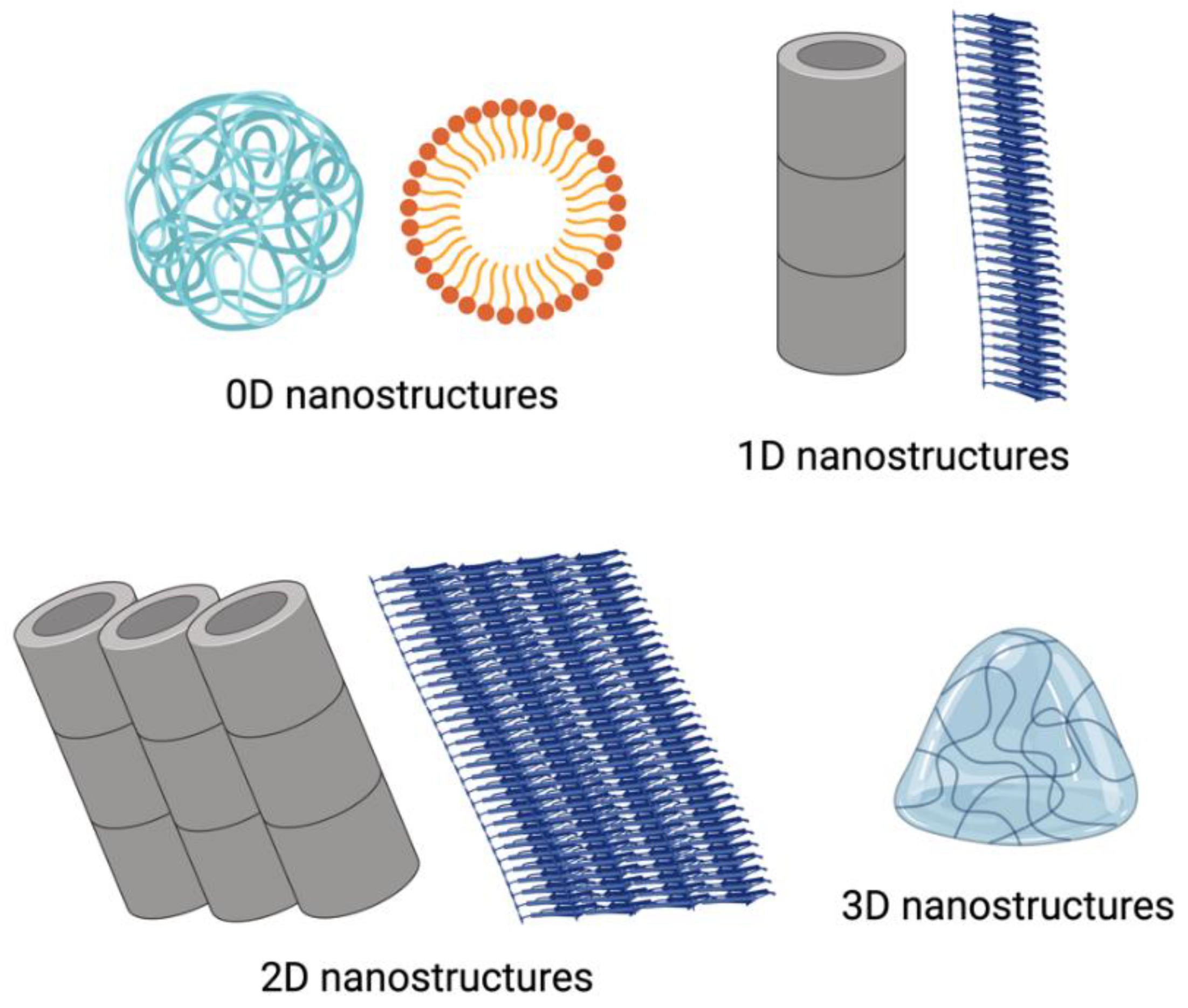

3. Different Types of Self-Assembled Nanostructures

Peptides can self-assemble into diverse hierarchical structures, including 0D nanoparticles and 1D, 2D, and 3D conformations (

Figure 2) [

30]. In contrast to bulk materials which can exhibit three-dimensional characteristics such as height, length and width, 0D nanostructures are individual particles or clusters without these three canonical dimensions. Due to their small size and high surface-to-volume ratio, they offer many reactive sites per unit mass, making them ideal for nanomaterial applications [

31]. Such self-assembled peptide nanoparticles and nanospheres are common examples of 0D nanostructures, typically formed through noncovalent π-π interactions, van der Waals and hydrophobic forces between different peptide sequences [

32]. Hydrophobic interactions are crucial in the self-assembly of these spherical nanoparticles. Following the principles of entropy minimisation and stability, the hydrophobic regions of amphiphiles aggregate into a core. At the same time, hydrophilic segments arrange themselves on the outer surface to form a shell-like morphology, thereby enhancing their interactions with water [

33].

Amyloid fibrils represent a well-characterized example of a 1D self-assembly structures, where peptides form nanofibrillar structures characterised by β-sheet-like secondary structures [

34]. Amyloids, which are aggregates of peptides or proteins, result from the oligomerisation of amyloidogenic sequences and are often associated with degenerative and chronic diseases [

35]. A minimalistic model developed by the Gazit group demonstrated the self-assembly of diphenylalanine (FF), the shortest functional unit, into nanofibrillar structures [

36]. Furthermore, the non-destructive self-assembly of Y-rich peptide nanofibers was conjugated with silver nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes to create functional nanoelectrodes [

37]. Similarly, Cormier et al. explored the self-healing properties of nanofibers formed from the peptide RADA16-1. In this case, alternating hydrophobic and charged subunits led to the formation of β-strands, creating a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic surface, with two β-strands stacking into the fundamental fibril unit [

38].

2D nanostructures have a planar lattice geometry extending in two dimensions. The inherent chirality of amino acids facilitates 1D elongation while limiting lateral growth, with peptide helices often employed to generate 2D morphologies [

39]. The self-assembly of heptapeptide KLVFFAK resulted in amyloid 2D nanosheets, as distinct from traditional amyloid fibrils, and was investigated in aqueous solutions, The study revealed a two-dimensional expansion along the fibril axis and a perpendicular “zippering” axis. In classic amyloid fibril assembly, β-sheets extend through hydrogen bonding, while perpendicularly arranged β-sheets pair into “steric zippers” with hydrophobic interfaces formed by side chains [

40]. Lee et al. identified a peptide sequence (YFCFY) that underwent a transition from monomer to dimer via disulfide bridge formation between cysteine subunits. This disulfide linkage initiated and stabilised helix formation, resulting in 2D macroscopic flat sheets [

41].

Peptides can also form 3D structures like hydrogels, commonly used in drug delivery and wound healing. The formation of these hydrogels depends on a balance between hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions and the presence of aromatic residues [

42]. Various secondary structures contribute to this hierarchical assembly, including β-pleated sheets and α-helices. These hydrogels can offer stimuli-responsive properties (e.g., pH and enzyme responsiveness), enabling targeted drug delivery. For example, a pH-responsive octapeptide, FOE, can self-assemble into a hydrogel at physiological pH, displaying injectability and anticancer properties [

43]. Peptide hydrogels, especially β-peptide hydrogels, have shown promise in several applications in tissue engineering due to their enhanced metabolic stability.

4. Hybrid Materials

Substantial progress has been achieved in conjugating peptides to various biomaterials, significantly enhancing their functional properties. Peptides offer several advantages, including high specificity, potency, cost-effectiveness, small size for improved tissue penetration and targeted delivery, biodegradability, and novel therapeutic potential. By incorporating these unique features into biomaterials, numerous advancements have been made. Among the various methods used for biomaterials modification, chemical techniques are the most well-established, providing an efficient means to immobilise target molecules onto specific surfaces.

Bioconjugation is a chemical process that links two substances through covalent or non-covalent bonds. Covalent bioconjugation is a preferred approach due to the stability of the bond and, generally, requires more stringent conditions than molecule organic synthesis. For instance, it is essential to maintain mild reaction conditions such as temperatures below 37°C, neutral pH, and aqueous buffers, to preserve the integrity and functionality of biomolecules. Furthermore, the presence of charged amino acids, including negatively charged acidic residues and positively charged basic residues, can affect the bioconjugation process, so controlling the pH conditions is an essential requirement and conjugation strategies must be tailored to the specific peptide sequence [

44,

45]. Currently, no single method for peptide conjugation is universally accepted, as each technique presents distinct advantages and limitations. Key factors to consider include the selectivity of the binding site, reaction efficiency, accessibility of reactants, and reaction rate. Among the most common methods are amine-reactive, thiol-reactive, and click chemistry reactions, which offer high levels of accessibility and selectivity [

46,

47].

Peptides are particularly suitable for bioconjugation due to their protein-like functionality and relative ease of their synthesis including specific amino acid sequences. Attaching peptides to the structural components of synthetic and natural materials is a common strategy to confer bioactive properties for clinical applications [

48]. Peptide-biomaterial conjugates can perform various functions, such as mimicking the native extracellular matrix (ECM) and enhancing cell adhesion with application in tissue regeneration. Peptides can also provide degradable linkers for scaffold remodelling or modulate cell signalling to promote tissue growth and differentiation.

5. Application of Peptide Materials to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections

The use of surgically implanted medical devices has significantly increased over the past five decades, greatly enhancing the quality of life for millions of patients worldwide. Progress in biomedical research has led to the development and improvement of various medical devices, such as stents, catheters and pacemakers. However, introducing foreign materials into the body carries an inherent risk of microbial colonisation and infection. Infections can occur during surgery or post-operatively, often originating from the patient's own microbiota [

49].

Infections associated with implanted medical devices pose a particular challenge due to the formation of bacterial biofilms. In natural environments, nearly all bacterial species have the capacity to form biofilms. Biofilms are organised systems that protect bacteria from host immune responses and antibiotics, making infections difficult to eradicate [

50].

Biofilm-related infections on implanted devices often lead to device failure, requiring high doses of antibiotics and subsequent removal and replacement of the infected device. This procedure subjects patients to additional surgeries, which carry significant risks and can increase mortality. Current treatments for device-associated infections are both expensive and often ineffective, largely due to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains and the risk of reinfection in newly implanted devices. As matter of fact, when biofilms are mature, nutrient depletion and the accumulation of toxic byproducts can cause the outer bacterial layers to revert to a planktonic state, enabling them to spread and cause new infections throughout the body. As a result, bacterial biofilms are a major reservoir for chronic infections, contributing to up to 80% of chronic bacterial infections [

51].

5.1. Peptide-Modified Polymers as Promising Antimicrobial Materials

To address the problem of chronic infections, the development of antimicrobial materials has become an active area of research. These materials, which include polymers, ceramics, metals, and composites, exhibit microbicidal activity against a single or a combination of pathogens (

Figure 3). One example of such material that has garnered significant attention are hydrogels. Hydrogels are soft biomaterials composed of highly hydrated polymeric networks, which can be engineered with various functional groups for applications in antibacterial therapy, tissue regeneration, and drug delivery [

52]. Due to their customisable nature, hydrogels can incorporate or tether a wide range of antimicrobial agents, offering a versatile platform to combat biofilm-associated infections [

53,

54,

55].

In many instances, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been directly incorporated into polymer blends without requiring extensive preparation while still retaining their functional efficacy. For example, the antimicrobial peptide Tet213 was directly added to a collagen solution following direct mixing with no reported decline in its functional activity [

56]. Similarly, the AMP piscidin-1 was introduced into chitosan scaffolds after scaffold fabrication [

57]. Alternatively, AMPs can be chemically conjugated to polymers. Cathelicidin LL-37 was conjugated onto a collagen scaffold by reacting the peptide on hydrophobic PDMS mats [

58]. Cross-linkers can also be utilised to attach AMPs to polymers. For instance, extracellular matrix-derived peptides were added to a chitosan matrix using the cross-linker maleimidobenzoyl [

59].

Research on the conjugation of AMPs to polymers primarily aims to enhance their stability and reduce toxicity while preserving their antimicrobial efficacy. Thus, in place of entrapping the peptides within the polymeric network, AMPs are immobilised onto solid surfaces. This can be accomplished through methods like simple adsorption, electrostatic interactions, or more stable covalent bonding. While physical adsorption can increase peptide stability, it presents challenges in controlling the degree of immobilisation and the release rate, as these processes rely on passive diffusion. Covalent conjugation offers more precise control over peptide concentration and retention time at the target site, thereby minimising side effects and reducing accumulation in organs such as the brain, liver, and spleen. This method typically involves modifying both the AMP and the polymer with functional groups necessary for chemoselective conjugation reactions. Given their moderate size, AMPs can be functionalised without significantly compromising their antimicrobial activity [

60]. Additionally, it was observed that AMPs not encapsulated demonstrated higher antimicrobial activity than those which were encapsulated. However, this difference might be attributed to the intrinsic properties of the peptides themselves rather than the encapsulation method.

Antimicrobial peptides can be conjugated to polymers via their N- or C-terminus. Since one of the termini is often more critical for antimicrobial activity, conjugation should be carried out via the terminus that is less involved in this activity. For example, anoplin that was conjugated to chitosan at the C-terminus was more effective against certain bacteria than N-terminal conjugation [

61]. Similar results were observed with Dhvar5 conjugated to chitosan, where N-terminal conjugation provided stronger anti-adhesive effects, while C-terminal conjugation showed higher bactericidal activity [

62,

63]. Conjugation through amino acid side chains is usually avoided due to the potential loss of antimicrobial activity. Generally, hydrophobic amino acids should be positioned away from the linkage site to enhance antimicrobial activity. However, this is not a universal rule.

Another key factor is the density of tethered AMPs on the surface with a minimum effective concentration required to achieve bacterial killing [

64]. A direct correlation exists between peptide concentration and antimicrobial activity, as higher graft densities often force peptides to interact with bacterial membranes. However, some bacteria, like

S. aureus, can become insensitive to increased AMP surface density. The choice of polymer plays a crucial role in enhancing AMP characteristics. Hydrophilic polymers, whether neutral or cationic, minimise the formation of a protein corona around the AMP-polymer conjugate, which can otherwise reduce antimicrobial activity by blocking interactions with bacteria. Neutral, hydrophilic polymers increase solubility and lower cytotoxicity to mammalian cells, while cationic polymers, despite increasing potency, may cause higher toxicity [

65]. Attention should be also paid to the polymers molecular weight. Higher molecular weight polymers may hinder access to bacterial membranes due to steric hindrance, reducing their likelihood of promoting membrane destabilisation [

65].

Antimicrobial peptides, being macromolecules, can have significant and varying impacts on the scaffolds into which they are incorporated, depending on the specific AMP used. For instance, the incorporation of AMP Tet213 into an alginate/hyaluronic acid/collagen wound dressing scaffold was found to negatively affect porosity. Although the porosity decreased, it remained close to the optimal porosity required for wound dressing applications. This reduction in porosity also contributed to a lower swelling rate. However, Tet213 had a slightly positive effect on the tensile strength of the scaffold, enhancing its mechanical stability in the presence of lysozyme [

56]. Other AMPs, such as piscidin-1, have been shown to produce highly porous chitosan scaffolds with favourable biodegradation rates [

57]. On the other hand, cathelicidin LL-37 exhibited strong antibacterial activity against a range of pathogens, including

Escherichia coli,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and

Bacillus subtilis. Cathelicidin was successfully bound to the Puracol skin model, demonstrating improved retention compared to unmodified sequence [

66].

Conjugation of AMPs to nanoparticles (NPs) is gaining interest due to their physicochemical properties, such as size and shape. NPs allow for higher AMP loading and require lower doses than soluble AMPs [

67,

68]. AMP-NP conjugates can more effectively penetrate bacterial biofilms, as their size, shape, surface charge, and composition facilitate initial interactions and penetration [

69]. However, AMP conjugation to NPs often diminishes antimicrobial activity, potentially due to aggregation and surface effects that alter AMP secondary structures [

65]. This issue can be mitigated by introducing large linkers like PEG, which provide conformational freedom, improving AMP-bacteria interaction [

70].

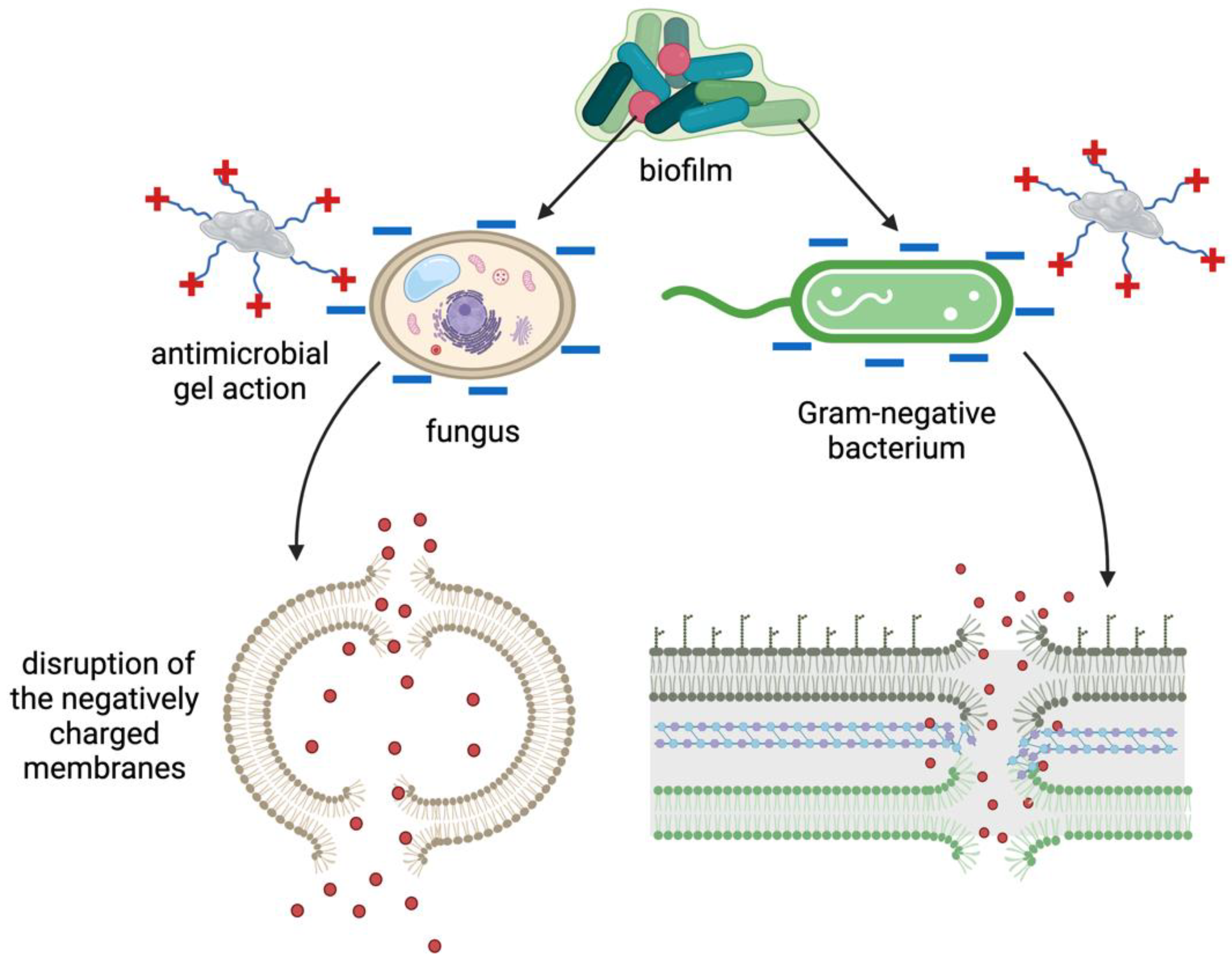

5.2. Antimicrobial Peptide-Based Hydrogels

Self-assembling hydrogels can be entirely peptide-based, forming 3D fibrous networks natively through noncovalent crosslinking involving ionic interactions, hydrophobic forces, hydrogen bonds, or π-π stacking interactions.

Peptides that self-assemble into these defined structures have gained attention for their diverse applications, ranging from materials to biomedical sciences. While AMPs produced by plants and animals exhibit natural antibacterial properties, their integration into self-assembling systems for biomedical applications has been limited.

Specific amphipathic AMPs can create supramolecular hydrogels, with self-assembly rates controlled by pH adjustments. For example, Azoulay et al. developed self-assembling AMP hydrogels using the FKF peptide sequence [

71]. This amphipathic, cationic peptide formed hydrogels when dissolved in an acidic buffer, with self-assembly occurring within minutes. The resulting hydrogels exhibited β-sheet structures stabilised by hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking interactions within a pH range of 3.3 to 4.3.

In vitro antibacterial assays demonstrated significant activity against

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa,

Acinetobacter baumannii, and

S. epidermidis.

In vivo, the hydrogel dressing reduced bacterial presence in a rat wound model inoculated with

P. aeruginosa. However, a 50% reduction in bacteria was accompanied by delayed wound closure, likely due to the acidic conditions necessary for hydrogel formation.

Amphipathic AMPs that self-assemble at physiological pHs can address biocompatibility concerns related to acidic aggregation conditions. D-amino acids, known for their resistance to bacterial proteases and inherent antibacterial properties, can be used to enhance the stability and efficacy of peptide hydrogels. The peptide KLVFFAK (KK-11) contains a self-assembling motif, and Guo et al. synthesised its D-amino acid analogue (KKd-11) to evaluate its antimicrobial potential. KKd-11 hydrogels formed rapidly at room temperature and effectively inhibited biofilm formation and eradicated bacteria within established biofilms of

E. coli and

S. aureus. Given their antimicrobial efficacy, biocompatibility, and resistance to proteolytic degradation, KKd-11 hydrogels show great potential for preventing wound infections and bacterial colonisation on medical devices [

72].

Cao and colleagues created a self-assembling hydrogel using the hexapeptide PAF26 (Ac-RKKWFW-NH

2), which aggregates at physiological pHs. PAF26 permeabilises through the microbial cell wall, leading to cell death. This amphipathic peptide forms hydrogels upon a gradual increase in pH from acid values to 7.5, with β-sheet structures confirmed in the final gel. The antimicrobial activity of PAF26 hydrogels was assessed by co-culturing them with fungi and bacteria, demonstrating a 100% killing efficiency against

Candida albicans,

S. aureus, and

E. coli. While these hydrogels show promise for clinical applications, further optimisation is needed to reduce potential cytotoxicity and ensure product safety [

73].

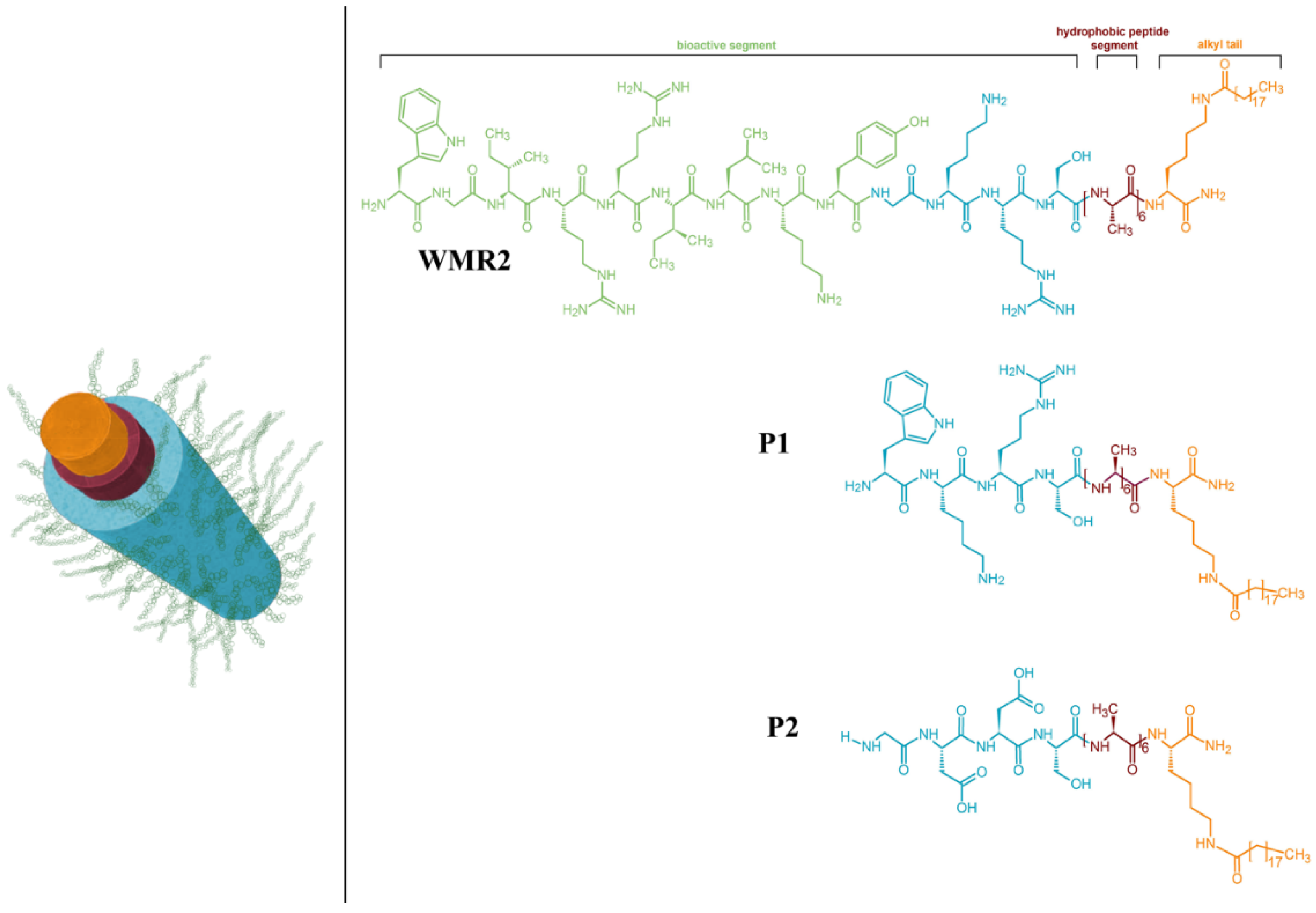

Most research on peptide-based hydrogels has focused on amphiphilic peptides that form β-sheet structures, disrupting bacterial cell walls. Lombardi et al. took a step further by integrating antimicrobial peptides into a self-assembling system, forming mixed β-sheet and α-helix structures, and offering opportunities to modulate their antimicrobial activity against a wide range of bacteria (

Figure 4). Combining multiple components, including AMPs and conventional antibiotics, presents a promising avenue for reducing antibiotic doses and the development of resistance. The study introduces peptide amphiphiles PAs, molecules containing a hydrocarbon chain attached to a peptide segment, as a versatile platform for self-assembly into cylindrical nanostructures. The antimicrobial peptide WMR, developed by the same group, is selected for its potent antibacterial activity, and the study aims to enhance antibiofilm activities against Gram-negative bacterium (

Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and the fungus

Candida albicans. [

55] This work demonstrates the potential of multivalent presentation of AMPs (WMR peptide) and short charged sequences, GDDS (PA2) and WKRS (PA1), on self-assembled nanostructures to improve antibiofilm activities, addressing the challenges posed by biofilm-related infections. The proposed nanosystem offers a strategy for designing smart materials with enhanced antibacterial efficacy and the potential for stimuli-responsive drug release [

54].

In a different approach, Adak et al. synthesised a novel antibacterial lipopeptide hydrogel containing palmitic acid conjugated to the peptide sequence NAVSIQKKK (PA-NV). These hydrogels exhibited biocompatibility, resistance to enzymatic degradation, and minimal cytotoxicity against mammalian cells. The cationic charge and amphiphilic nature of PA-NV enable interactions with bacterial membranes, facilitating disruption and bacterial killing. The formation of β-sheets here aids in gelation, producing a soft, biocompatible material. These properties make PA-NV hydrogels promising candidates for clinical applications, and their performance in in vivo models remains a topic of interest [

74].

Polymerisation techniques and conjugation strategies have facilitated the synthesis of well-defined peptide−polymer conjugates, introducing a wider range of hydrophobicity and tail flexibility compared to lipid tails [

75,

76]. These synthetic polymer tails also provide mechanisms to control PA morphology, allowing for the suspension of a hydrophobic peptide core in aqueous media. However, the introduction of solution dispersity by synthetic polymer tails can impact on self-assembly bahaviour, with shorter polymers stabilising multichain assemblies, particularly in micellar structures.

In addition to multichain structures like micelles and vesicles, single-chain organisation is also significant for biological function. Recent advances in the design of single-chain polymer nanoparticles (SCNPs) aim to replicate the sophisticated folding observed in proteins. SCNPs, synthetic polymers with intrachain folding driven by crosslinking or noncovalent interactions, exhibit protein-mimetic structures. While SCNPs may lack the precision of folded proteins, their morphology resembles that of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Unlike well-defined proteins, IDPs fold on a complex energy landscape with transiently coexisting structures. SCNPs, with biomimetic functions like enzyme-like catalysis, demonstrate their potential to mimic and expand upon the roles of natural biomaterials, showcasing their importance in synthetic biology [

77].

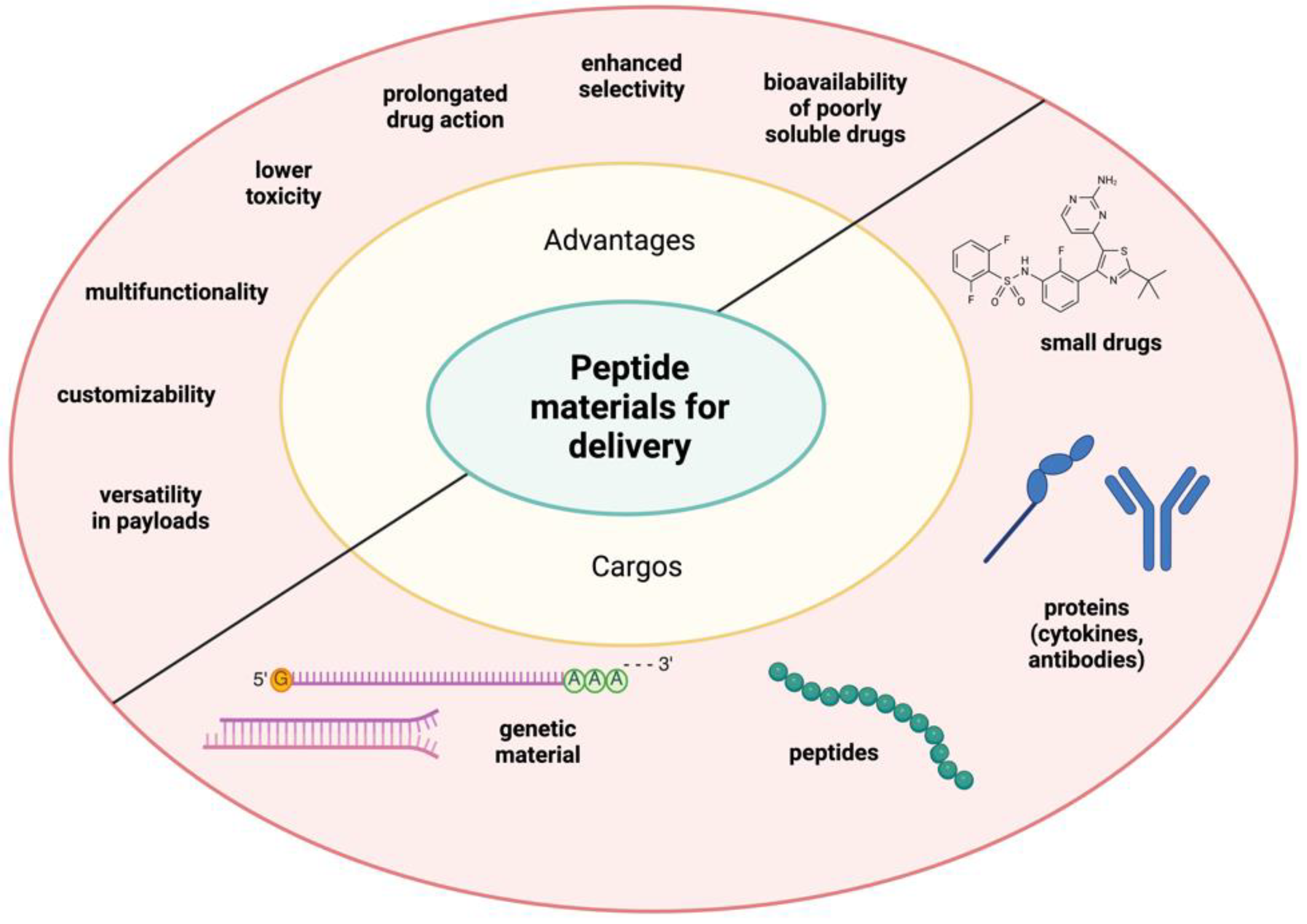

6. Application of Peptide Materials for Drug Delivery

The biocompatibility, biodegradability, and multifunctionality of self-assembled peptides have made them efficient materials for delivering small molecules, protein drugs, cytokines, and genetic materials into the body. This delivery system can improve the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs, enhance the selectivity of active agents, and prolong drug action (

Figure 5) [

78,

79]. Furman et al. identified two new EGFR-specific short cyclic peptides, P6 and P9, which, when combined with camptothecin (CPT), did not interfere with its chemotherapeutic effects. In fact, these peptides targeted drug delivery to tumoural cells overexpressing EGFR and EGFRvIII mutations [

80].

Mehrabi Nasab et al. created an asthma model using spherical nanoparticles combined with corticotropin peptides and treated it with nanomedicines. The results showed that the anti-inflammatory effects of the peptide-nanoparticle combination were significantly greater than those of the peptide alone, indicating the potential of peptide-nanoparticle formulations to target and deliver drugs precisely to inflamed lung tissue [

81].

Peptide-based nanosystems, including nanotubes, nanofibers, and hydrogels, have emerged as promising drug delivery vehicles due to their inherent biocompatibility, gaining attention for anticancer drug delivery and enhancing cancer therapy outcomes. These peptide-based nanostructures are promising for developing new advanced, targeted, and effective anticancer therapies.

Self-assembling peptides can form nanovesicles influenced by the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties of their constituent amino acid chains. These nanovesicles can encapsulate a range of therapeutic agents, including vitamins, anticancer drugs, and antibiotics, and demonstrate sustained release behaviour [

82]. Nanovesicles created from dipeptides exhibit excellent encapsulation and targeted release in response to specific stimuli. They have also been used for improved photodynamic therapy (PDT) and for targeted drug delivery by enhancing cellular uptake [

83,

84]. Tian et al. developed a peptide-paclitaxel conjugate (PPC) that naturally self-assembled into uniform nanospheres in an aqueous environment, leveraging the inherent self-assembly characteristics of paclitaxel. The formation of these nanospheres did not diminish the cytotoxic activity of paclitaxel, showing similar effectiveness to that of the free drug. This indicates the potential of this system as an efficient carrier for delivering anticancer agents such as doxorubicin [

85]. Peptide-based micellar systems offer an inner hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic surface for drug encapsulation. Modified micelles incorporating targeting peptides have shown increased specificity and sensitivity toward tumour antigens, enhancing drug delivery efficiency [

86]. Tumour-homing peptides and enzyme-responsive micelles have been designed for improved tumour targeting and controlled drug release, demonstrating their potential in cancer therapy [

87].

Due to their nanoscale size and shape, peptide nanotubes are efficient drug delivery scaffolds, facilitating cell membrane interaction and intracellular transport. Drugs can be easily encapsulated within these structures, effectively targeting cell organelles. Diphenylalanine (FF) and its analogues self-assemble into various nanostructures, including nanotubes that offer sustained drug release, particularly in acidic environments [

88].

Xu et al. synthesised a novel peptide analogue, Fc-FFRGD, consisting of a ferrocene group (Fc), an FF dipeptide, and an RGD motif. This molecule could form stable nanostructures and hydrogels in an aqueous environment thanks to its amphiphilic properties and strong non-covalent interactions. It shows great potential as a biomimetic material for cell adhesion and growth and as a nanocarrier for drug encapsulation and delivery through integrin-dependent interactions [

89]. Both linear and cyclic peptides can form nanotubes, with cyclic peptides offering precise diameter control [

90].

Additionally, peptide nanorods and chimeric peptides have been developed for targeted and synergistic cancer therapies, offering improved cellular uptake and nuclear localisation upon light irradiation [

91]

Self-assembled peptide nanosheets can improve the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of entrapped drugs. pH-sensitive tetrapeptides have been synthesised to form nanosheets, which exhibit safe internalisation and shape-dependent cytotoxicity in cancer cells [

92]. The co-assembly of peptides with other molecules can result in supramolecular peptide nanoparticles for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Peptide hydrogels formed through self-assembly offer higher biodegradability, low toxicity, and high drug-loading capacity. They can enhance direct contact of chemotherapeutic drugs with targeted cancer tissues, improving therapeutic efficacy. Hydrogels can be stabilised through ionic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and pH-responsive assembly, providing stimuli-responsive drug release [

12].

7. Self-Assembling Peptides as Matrix Mimetics in Pharmaceutical Market and Clinical Trials

Several self-assembling peptides have successfully transitioned from research and development into the clinical setting, demonstrating their efficacy in the pharmaceutical market. These products are notable for their ability to improve drug delivery, enhance therapeutic efficacy, and offer more patient-friendly dosing regimens. With their 3D fibrous networks, peptide-based self-assembled materials are utilised in commercial products, such as Matrixyl in dermatological formulations and C

16-GHK for addressing skin ageing issues. PuraMatrix, another commercially available peptide gel, is used in 3D tissue cultures, promoting tissue growth with biodegradable and nonimmunogenic properties [

93]. Recognising the significance of self-assembled peptide-based materials, understanding the self-assembly process and relevant techniques becomes crucial. While short peptides are economically viable and easily manufacturable, ultrashort peptides (up to seven amino acids) also exhibit self-assembly capabilities, offering the advantage of prompt sequence fine-tuning for specific requirements. [

94] Ultrashort peptides have applications that extend beyond biology, including toxic metal detection, wastewater treatment, crop protection, and green energy generation. Their diverse physicochemical properties in different organic solvents make them useful for compound purification and as platforms for chemical catalysis. With their mild and rapid synthesis, along with the ability to be fine-tuned through modifications, functionalisation, and self-assembly, ultrashort peptides are versatile biomaterials suited for a wide range of applications [

95].

Other examples of peptide materials on the market include the well-studied sequences lanreotide or RADA16. Lanreotide is a synthetic octapeptide analogue of somatostatin, a natural compound that typically regulates growth hormones and inhibits the secretion of other hormones such as serotonin, gastrin, and pancreatic polypeptide [

96]. Due to its rapid degradation in the body, lanreotide has been explored for its self-assembly behaviours. The peptide was engineered as a more pharmacologically stable form. This compound emulates the inhibitory effects of somatostatin on hormone release, including growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), positioning it as a key therapeutic agent in the management of acromegaly and certain gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP-NETs) [

97]. The development of lanreotide started with the sustained release (lanreotide SR) formulation using a microparticle-based drug-delivery system to enhance patient adherence, which required intramuscular injections every 7 to 14 days [

98]. Later, in 2007, the FDA approved lanreotide autogel (ATG) (marketed as Somatuline® Depot), an advanced formulation containing lanreotide acetate in a supersaturated aqueous solution, delivered as a deep subcutaneous injection every four weeks, significantly reducing the treatment frequency [

99]. The self-assembly characteristics of lanreotide are integral to its controlled-release mechanism. Its cyclic structure, stabilised by disulphide bridges, facilitates the formation of dimers that subsequently arrange into β-sheet-rich filaments through non-covalent forces, such as hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions [

100]. These filaments then form nanotubes, forming a hydrogel structure in aqueous environments. This unique hydrogel slowly disassembles at low concentration solutions, enabling a slow and controlled release profile for drug delivery. Additionally, the formulation incorporates acetic acid (AcOH) as a counterion, which plays a crucial role in modulating the self-assembly behaviours of lanreotide containing two basic amino acids [

99].

RADA16 is a synthetic ion-complementary self-assembling peptide designed after EAK16 and has been extensively studied for its unique properties and diverse biomedical applications. The peptide consists of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids with charged distribution as + - + - + - + -, allowing it to self-assemble into β-sheet nanofibrous structures in physiological environments. This self-assembly results in the formation of hydrogels, which possess high stability and mimic natural ECM. Due to its biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and ability to support cell attachment and proliferation, researchers and surgeons have utilised the distinctive features of RADA16 in various experimental and clinical settings [

101,

102]. Commercialised as PuraMatrix™ (1% RADA16), RADA16 functions as an ECM substitute for investigating cell adhesion, chemotaxis, proliferation, and development in laboratory settings, and as a 3D scaffold for in vitro and preclinical in vivo studies on wound healing, and tissue engineering [

103]. Another application of RADA16 is as a hemostatic agent marketed as PuraStat® (2.5% RADA16), which is a CE-marked class III medical device used to control bleeding during surgeries by forming a physical barrier that stabilises clot formation [

104]. PuraStat® has gained approval in several regions, including Europe and Asia, for use in gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures and surgeries to prevent delayed bleeding. It offers a safe profile with minimal side effects, making it a widely accepted solution in clinical settings. Additionally, RADA16 has found utility in wound care, marketed as PuraDerm® in the United States for treating complex wounds, including diabetic and surgical ulcers [

105]. Another formulation approved by the FDA in 2019, PuraSinus® (2.5% RADA16), is designed to prevent adhesions following nasal surgery and promote wound healing in the sinus cavity [

106].

8. Sheets of Peptidomimetics

Natural and synthetic peptides, including peptoids and other peptidomimetics, are gaining significant attention in materials science, nanotechnology, and biomedical engineering for their stable and intriguing self-assembled structures. Inspired by natural proteins, these peptides emulate the functions and structures of proteins like silk, ECM, fibronectin, and collagen, with potential applications in biotechnology and medicine. Leveraging their biological qualifications including biocompatibility, bioactivity, and microporous structure, peptidomimetic molecules show promise in various fields, including drug delivery, optical waveguides, photothermal conversions, and photocatalysis.

The Zuckermann group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory has probed the physical properties of peptoid monolayers influencing nanosheet collapse by employing interfacial dilatational rheology. Peptoid analogues were compared to assess their nanosheet-forming abilities. Using small sample volumes, rapid and convenient rheological studies provided insights into molecular-level processes crucial for designing nanosheets with advanced functionality. Understanding the self-assembly mechanism and its tolerance to chemical modifications is crucial for designing nanosheets with advanced chemical functionality. While monolayer adsorption at the air-water interface is necessary for nanosheet formation, it is not the sole limiting factor. A set of design rules for peptoid sequences forming collapse-competent monolayers was established by characterising peptoid monolayers using surface dilatational rheology. Monolayer fluidity, represented by the residence time (τ

D), correlates with the ability to collapse into bilayer nanosheets. Nanosheet-forming monolayers exhibit solid-like behaviour with strong interchain interactions (τ

D > 5000 s), while non-forming monolayers are fluid-like with weaker interactions (τ

D < 500 s). Small chemical modifications to peptoid chains directly impacts rheological behaviour, offering insights for sequence design and rapid screening for nanosheet-forming ability. This understanding enhances the potential applications of peptoid nanosheets in diverse fields. Zuckermann introduces an innovative approach centred on the design and synthesis of antibody-mimetic materials utilising functionalised peptoid nanosheets. While antibodies hold promise for molecular recognition in chemical and biological sensors due to their high specificity and affinity for various analytes, challenges such as poor stability and high production costs limit their widespread use in sensing devices. In addressing these challenges, this group presents a novel strategy involving the utilisation of peptoid nanosheets. These nanosheets feature a high density of conformationally constrained peptide and peptoid loops on their free-floating surfaces, creating a chemically and biologically stable, extended, multivalent two-dimensional material. Serving as a robust scaffold with a large surface area, the nanosheet facilitates the presentation of diverse functional loop sequences. [

107] Characterisation methods such as atomic force microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and X-ray reflectivity measurements have highlighted the potential of the functionalised nanosheets. These nanosheets are particularly effective as substrates for enzymes like protease and casein kinase II and templates for the controlled growth of specific inorganic materials, such as gold. This novel approach shows promise in addressing the stability and cost issues commonly encountered with traditional antibodies in sensing applications.

9. Conclusions and Future Vision

Peptides hold immense potential in the development of advanced biomaterials. Their unique properties, including self-assembly, responsiveness to biological stimuli, and selective binding to specific tissues or cells, position them to drive significant advancements in scaffold design for tissue engineering, improved drug delivery systems, and enhanced coatings for medical implants that promote integration while minimising infection risks. Additionally, with our increasingly deeper understanding of disease pathways, peptides can be modified to carry small molecules or receptor domains, further improving therapeutic outcomes. These biomaterials can be customised to respond to environmental changes within the body, allowing for on-demand and targeted drug release and dynamic adjustments in their physical properties to better integrate with surrounding tissues.

Synthetic peptides demonstrate exceptional versatility in their conjugation chemistry and can be engineered to replicate the active amino acid sequences of various proteins, thereby enhancing their binding affinity for specific targets. Furthermore, chemical modifications such as cyclisation and the use of peptoids can improve peptide stability, making them even more suitable for clinical applications.

Peptides present promising solutions to several pressing medical challenges, including tissue regeneration, infection control, and targeted drug delivery. A notable example, PuraMatrix, exemplifies the practical potential of peptide-based biomaterials in clinical settings. However, transitioning these innovations from laboratory research to clinical applications requires long effort and interdisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, chemists, biologists, and clinicians.

Despite the significant advances reported here, a substantial knowledge gap persists in this field. Further research is needed to expand the repertoire of peptides suitable for biomaterial development. Moreover, future investigations should explore combinatorial peptide approaches to uncover potential synergistic effects. Challenges remain including ensuring the stability of three-dimensional structures in self-assembled peptide hydrogels. Additionally, establishing comprehensive monitoring systems is essential, especially when integrating self-assembled peptides with other materials or drugs, and in tissue regeneration, where precise control over repair processes is critical.

Addressing these challenges will be pivotal for driving further progress. As research advances, peptides are expected to play a crucial role in significantly enhancing the specificity and functionality of biomaterials, potentially transforming the landscape of biomedical engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L., J.L., D.R.W.; figures and table, L.L. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Imperial College London and XXXX.

Acknowledgments

The continuous support of Imperial College London is acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frokjaer, S.; Otzen, D.E. Protein drug stability: a formulation challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.D.; Wagener, K.B. Precision Polymers through ADMET Polymerization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2014, 215, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, S. 50th Anniversary Perspective: RAFT Polymerization A User Guide. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 7433–7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, H.; Xiao, M.; Jia, H.; Ren, C.; Liu, J. Peptide-Based Supramolecular Therapeutics for Fighting Major Diseases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; An, H.-W.; Wang, H. Self-Assembled Peptide Drug Delivery Systems. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 4, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, M.R.; Granja, J.R.; Milligan, R.A.; McRee, D.E.; Khazanovich, N. Self-assembling organic nanotubes based on a cyclic peptide architecture. Nature 1993, 366, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lockshin, C.; Cook, R.; Rich, A. Unusually stable β-sheet formation in an ionic self-complementary oligopeptide. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 1994, 34, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-T.; Xia, Y.-Y.; Gao, J.-Q.; Xu, D.-H.; Han, M. Recent Progress in the Design and Medical Application of In Situ Self-Assembled Polypeptide Materials. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Gao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, S. “PP-type” self-assembling peptides with superior rheological properties. Nanoscale Advances 2021, 3, 6056–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Fung, S.-Y.; Pritzker, M.; Chen, P. Ionic-Complementary Peptide Matrix for Enzyme Immobilization and Biomolecular Sensing. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7773–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Lu, S.; Zhao, D.; Ding, Y.; Chen, P. Arginine-rich ionic complementary peptides as potential drug carriers: Impact of peptide sequence on size, shape and cell specificity. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Ji, W.; Palmer, L.C.; Weber, B.; Barz, M.; Stupp, S.I. Programmable Assembly of Peptide Amphiphile via Noncovalent-to-Covalent Bond Conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8995–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epps III, T.H.; O'Reilly, R.K. Block copolymers: controlling nanostructure to generate functional materials–synthesis, characterization, and engineering. Chemical Science 2016, 7, 1674–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Maltzahn, G.; Vauthey, S.; Santoso, S.; Zhang, S. Positively Charged Surfactant-like Peptides Self-assemble into Nanostructures. Langmuir 2003, 19, 4332–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauthey, S.; Santoso, S.; Gong, H.; Watson, N.; Zhang, S. Molecular self-assembly of surfactant-like peptides to form nanotubes and nanovesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 5355–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.J.; Appel, E.A.; Meijer, E.; Langer, R. Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.; Notman, R.; Anwar, J.; Rodger, A.; Hicks, M.; Parkinson, G.; McCarthy, D.; Daviter, T.; Moger, J.; Garrett, N.; et al. Nanofiber-Based Delivery of Therapeutic Peptides to the Brain. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.A.; Hamley, I.W.; Torras, J.; Alemán, C.; Seitsonen, J.; Ruokolainen, J. Self-Assembly of Lipopeptides Containing Short Peptide Fragments Derived from the Gastrointestinal Hormone PYY3–36: From Micelles to Amyloid Fibrils. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, Z. Self-Assembly of Bolaamphiphiles into 2D Nanosheets via Synergistic and Meticulous Tailoring of Multiple Noncovalent Interactions. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3152–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, A.; Nagai, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhang, S. Dynamic Behaviors of Lipid-Like Self-Assembling Peptide A6D and A6K Nanotubes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007, 7, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Dey, J.; Roy, S.; Dasgupta, S.B. Self-Assembly, In Vitro Gene Transfection, and Antimicrobial Activity of Biodegradable Cationic Bolaamphiphiles. Langmuir 2023, 39, 10021–10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannige, R.V.; Haxton, T.K.; Proulx, C.; Robertson, E.J.; Battigelli, A.; Butterfoss, G.L.; Zuckermann, R.N.; Whitelam, S. Peptoid nanosheets exhibit a new secondary-structure motif. Nature 2015, 526, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wong, C.T.T.; Li, X. Chemoselective Peptide Cyclization and Bicyclization Directly on Unprotected Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 12274–12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, A.N.; Mozaffari, S.; Sherpa, R.T.; Tiwari, R.; Parang, K. Efficient Intracellular Delivery of Cell-Impermeable Cargo Molecules by Peptides Containing Tryptophan and Histidine. Molecules 2018, 23, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Aulisa, L.; Regan, K.R.; D’Souza, R.N.; Hartgerink, J.D. Self-Assembling Multidomain Peptide Hydrogels: Designed Susceptibility to Enzymatic Cleavage Allows Enhanced Cell Migration and Spreading. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3217–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.N.; Hartgerink, J.D. Self-Assembling Multidomain Peptide Nanofibers for Delivery of Bioactive Molecules and Tissue Regeneration. Accounts Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Silva, T.L.; Leach, D.G.; Li, I.-C.; Wang, X.; Hartgerink, J.D. Self-Assembling Multidomain Peptides: Design and Characterization of Neutral Peptide-Based Materials with pH and Ionic Strength Independent Self-Assembly. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 5, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickremasinghe, N.C.; Kumar, V.A.; Shi, S.; Hartgerink, J.D. Controlled Angiogenesis in Peptide Nanofiber Composite Hydrogels. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, L.; Lu, K.; Zhao, D. Mechanism of Peptide Self-assembly and Its Study in Biomedicine. Protein J. 2024, 43, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, S.; Di Natale, C.; Onesto, V.; Marasco, D. Self-assembling peptides: From design to biomedical applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, T.; Liang, R.; Wei, M. Application of Zero-Dimensional Nanomaterials in Biosensing. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wan, K.; Zhou, N.; Wei, G.; Su, Z. Supramolecular peptide nano-assemblies for cancer diagnosis and therapy: from molecular design to material synthesis and function-specific applications. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Fang, T.; Li, M.; Chen, G.; Chen, Q. Supramolecular biomaterials for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 7183–7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvirdipour, S.; Huang, X.; Mihali, V.; Schoenenberger, C.-A.; Palivan, C.G. Peptide-Based Nanoassemblies in Gene Therapy and Diagnosis: Paving the Way for Clinical Application. Molecules 2020, 25, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, E.; Toniolo, C.; Venanzi, M. Peptide Self-Assembled Nanostructures: From Models to Therapeutic Peptides. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmachari, S.; Arnon, Z.A.; Frydman-Marom, A.; Gazit, E.; Adler-Abramovich, L. Diphenylalanine as a Reductionist Model for the Mechanistic Characterization of β-Amyloid Modulators. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 5960–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, E.; Lee, Y.; Yi, H.; Kim, D. Facile Nondestructive Assembly of Tyrosine-Rich Peptide Nanofibers as a Biological Glue for Multicomponent-Based Nanoelectrode Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, A.R.; Pang, X.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Zhou, H.-X.; Paravastu, A.K. Molecular Structure of RADA16-I Designer Self-Assembling Peptide Nanofibers. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 7562–7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merg, A.D.; Touponse, G.; van Genderen, E.; Zuo, X.; Bazrafshan, A.; Blum, T.; Hughes, S.; Salaita, K.; Abrahams, J.P.; Conticello, V.P. 2D Crystal Engineering of Nanosheets Assembled from Helical Peptide Building Blocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13507–13512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Li, D.; Xi, W.; Luo, F.; Zhang, X.; Zou, M.; Cao, M.; Hu, J.; Wang, W.; Wei, G.; et al. Tunable assembly of amyloid-forming peptides into nanosheets as a retrovirus carrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 2996–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choe, I.R.; Kim, N.-K.; Kim, W.-J.; Jang, H.-S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Nam, K.T. Water-Floating Giant Nanosheets from Helical Peptide Pentamers. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8263–8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.B.P.; Gomes, V.; Ferreira, P.M.T.; Martins, J.A.; Jervis, P.J. Peptide-Based Supramolecular Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Agents: Recent Advances. Gels 2022, 8, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ge, L.; Zhang, Y. Short and simple peptide-based pH-sensitive hydrogel for antitumor drug delivery. Chinese Chemical Letters 2022, 33, 1936–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri-Ledari, R.; Maleki, A. Antimicrobial therapeutic enhancement of levofloxacin via conjugation to a cell-penetrating peptide: An efficient sonochemical catalytic process. J. Pept. Sci. 2020, 26, e3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, K.P.; Suhas, R.; Gowda, D.C. Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Peptide-Conjugates: Modulation of Activity by Charged and Hydrophobic Residues. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2017, 25, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanson, G.T. Bioconjugate Techniques; Academic press: 2013.

- Alves, P.M.; Barrias, C.C.; Gomes, P.; Martins, M.C.L. How can biomaterial-conjugated antimicrobial peptides fight bacteria and be protected from degradation? Acta Biomaterialia 2024, 181, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S.A.; Baker, A.E.; Shoichet, M.S. Designing Peptide and Protein Modified Hydrogels: Selecting the Optimal Conjugation Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7416–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms and Device-Associated Infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.-F. Biofilm-Specific Antibiotic Resistance. Futur. Microbiol. 2012, 7, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Ahmad, W.; Andleeb, S.; Jalil, F.; Imran, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, M.; Kamil, M.A. Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2018, 81, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliari, S.R.; Burdick, J.A. A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, E.; Lombardi, L.; Falanga, A.; Libralato, G.; Guida, M.; Carotenuto, R. Biofilms: Novel Strategies Based on Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Shi, Y.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, E.; de Alteriis, E.; Franci, G.; Chourpa, I.; Azevedo, H.S.; Galdiero, S. Enhancing the Potency of Antimicrobial Peptides through Molecular Engineering and Self-Assembly. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, L.; Stellato, M.I.; Oliva, R.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, M.; Petraccone, L.; D’errico, G.; De Santis, A.; Galdiero, S.; Del Vecchio, P. Antimicrobial peptides at work: interaction of myxinidin and its mutant WMR with lipid bilayers mimicking the P. aeruginosa and E. coli membranes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep44425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, T.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; Xia, H.; Zhang, T. Biofunctions of antimicrobial peptide-conjugated alginate/hyaluronic acid/collagen wound dressings promote wound healing of a mixed-bacteria-infected wound. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, N.; Hamidabadi, H.G.; Khosravimelal, S.; Zahiri, M.; Ahovan, Z.A.; Bojnordi, M.N.; Eftekhari, B.S.; Hashemi, A.; Ganji, F.; Darabi, S.; et al. Antimicrobial peptides-loaded smart chitosan hydrogel: Release behavior and antibacterial potential against antibiotic resistant clinical isolates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Ma, G.; Cui, F.; Liu, H. An antimicrobial peptide-loaded gelatin/chitosan nanofibrous membrane fabricated by sequential layer-by-layer electrospinning and electrospraying techniques. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozumi, K.; Nomizu, M. Mixed Peptide-Conjugated Chitosan Matrices as Multi-Receptor Targeted Cell-Adhesive Scaffolds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hong, T.; Cui, P.; Wang, J.; Xia, J. Antimicrobial peptides towards clinical application: Delivery and formulation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahariah, P.; Sorensen, K.K.; Hjalmarsdottir, M.A.; Sigurjonsson, O.E.; Jensen, K.J.; Masson, M.; Thygesen, M.B. Antimicrobial peptide shows enhanced activity and reduced toxicity upon grafting to chitosan polymers. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11611–11614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.; Costa, F.; Monteiro, C.; Duarte, F.; Martins, M.C.L.; Gomes, P. Antimicrobial coatings prepared from Dhvar-5-click-grafted chitosan powders. Acta Biomater. 2018, 84, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, P.M.; Pereira, R.F.; Costa, B.; Tassi, N.; Teixeira, C.; Leiro, V.; Monteiro, C.; Gomes, P.; Costa, F.; Martins, M.C.L. Thiol–Norbornene Photoclick Chemistry for Grafting Antimicrobial Peptides onto Chitosan to Create Antibacterial Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 5012–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpert, K.; Elliott, M.; Jenssen, H.; Kindrachuk, J.; Fjell, C.D.; Körner, J.; Winkler, D.F.; Weaver, L.L.; Henklein, P.; Ulrich, A.S.; et al. Screening and Characterization of Surface-Tethered Cationic Peptides for Antimicrobial Activity. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Luo, Q.; Bannon, M.S.; Gray, V.P.; Bloom, T.G.; Clore, M.F.; Hughes, M.A.; Crawford, M.A.; Letteri, R.A. Molecular engineering of antimicrobial peptide (AMP)–polymer conjugates. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 5069–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozeau, L.D.; Grosha, J.; Kole, D.; Prifti, F.; Dominko, T.; Camesano, T.A.; Rolle, M.W. Collagen tethering of synthetic human antimicrobial peptides cathelicidin LL37 and its effects on antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity. Acta Biomater. 2017, 52, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiero, E.; Falanga, A.; Siciliano, A.; Maselli, V.; Guida, M.; Carotenuto, R.; Tussellino, M.; Lombardi, L.; Benvenuto, G.; Galdiero, S. Daphnia magna and Xenopus laevis as in vivo models to probe toxicity and uptake of quantum dots functionalized with gH625. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, ume 12, 2717–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiero, E.; Siciliano, A.; Maselli, V.; Gesuele, R.; Guida, M.; Fulgione, D.; Galdiero, S.; Lombardi, L.; Falanga, A. An integrated study on antimicrobial activity and ecotoxicity of quantum dots and quantum dots coated with the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, ume 11, 4199–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkodenko, L.; Kassirov, I.; Koshel, E. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles Against Bacterial Biofilms: Perspectives and Limitations. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.R.; Moura, A.; Leiro, V.; Silva-Carvalho, R.; Estevinho, B.N.; Seabra, C.L.; Henriques, P.C.; Lucena, M.; Teixeira, C.; Gomes, P.; et al. Grafting MSI-78A onto chitosan microspheres enhances its antimicrobial activity. Acta Biomater. 2021, 137, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, Z.; Aibinder, P.; Gancz, A.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Rapaport, H. Assembly of cationic and amphiphilic β-sheet FKF tripeptide confers antibacterial activity. Acta Biomater. 2021, 125, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, T.; Ji, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. Antimicrobial D-peptide hydrogels. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Mei, L.; Zhu, G.; Song, M.; Zhang, X. An injectable molecular hydrogel assembled by antimicrobial peptide PAF26 for antimicrobial application. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 30803–30808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Ghosh, S.; Gupta, V.; Ghosh, S. Biocompatible lipopeptide-based antibacterial hydrogel. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartgerink, J.D.; Beniash, E.; Stupp, S.I. Self-Assembly and Mineralization of Peptide-Amphiphile Nanofibers. Science 2001, 294, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, H.-A. Peptide/protein− synthetic polymer conjugates: quo vadis. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 7990–8000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artar, M.; Souren, E.R.J.; Terashima, T.; Meijer, E.W.; Palmans, A.R.A. Single Chain Polymeric Nanoparticles as Selective Hydrophobic Reaction Spaces in Water. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.B.; Ozguney, B.; Vlachou, A.; Chen, Y.; Gazit, E.; Tamamis, P. Peptide Self-Assembled Nanocarriers for Cancer Drug Delivery. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 1857–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhàn, N.T.T.; Yamada, T.; Yamada, K.H. Peptide-Based Agents for Cancer Treatment: Current Applications and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, O.; Zaporozhets, A.; Tobi, D.; Bazylevich, A.; Firer, M.A.; Patsenker, L.; Gellerman, G.; Lubin, B.C.R. Novel Cyclic Peptides for Targeting EGFR and EGRvIII Mutation for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, D.M.; Taheri, A.; Athari, S.S. Evaluation Anti-inflammatory Effect of Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles with Cortistatin Peptide as Drug Delivery to Asthmatic Lung Tissue. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2023, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.S.; Alam, S.; Panda, J.J. Novel dipeptide nanoparticles for effective curcumin delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 4207–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hell, A.J.; Fretz, M.M.; Crommelin, D.J.; Hennink, W.E.; Mastrobattista, E. Peptide nanocarriers for intracellular delivery of photosensitizers. J. Control. Release 2010, 141, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shi, B.; Wang, K.; Fan, M.; Jiao, D.; Ao, J.; Song, N.; Wang, C.; Gu, J.; Li, Z. Development of self-assembling peptide nanovesicle with bilayers for enhanced EGFR-targeted drug and gene delivery. Biomaterials 2016, 82, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Wang, H.; Niu, R.; Ding, D. Drug delivery with nanospherical supramolecular cell penetrating peptide–taxol conjugates containing a high drug loading. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 453, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Yang, J.; Mamuti, M.; Hou, D.Y.; An, H.W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. Controllable Self-Assembly of Peptide-Cyanine Conjugates In Vivo as Fine-Tunable Theranostics. Angewandte Chemie 2021, 133, 7888–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barve, A.; Jain, A.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, K. Enzyme-responsive polymeric micelles of cabazitaxel for prostate cancer targeted therapy. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Geng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Fan, X.; Mei, D.; Gazit, E.; Tao, K. Fmoc-diphenylalanine gelating nanoarchitectonics: A simplistic peptide self-assembly to meet complex applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 636, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, J.; Tian, J.; Gao, L.; Cheng, X.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, X. Supramolecular Self-Assemblies with Nanoscale RGD Clusters Promote Cell Growth and Intracellular Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 29906–29914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotto, O.; D’andrea, P.; Marchesan, S. Nanotubes and water-channels from self-assembling dipeptides. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 5378–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, A.; Rana, P.; Das, K.; Pan, I.; Mandal, D.; Stewart, A.; Maity, B.; Ghosh, S.; Das, P. Fabrication of self-assembled nanostructures for intracellular drug delivery from diphenylalanine analogues with rigid or flexible chemical linkers. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 6176–6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibh, S.; Aggarwal, N.; Mallick, Z.; Sengupta, D.; Sachdeva, P.K.; Bera, C.; Yadav, N.; Chauhan, V.S.; Mandal, D.; Panda, J.J. Bio-piezoelectric phenylalanine-αβ-dehydrophenylalanine nanotubes as potential modalities for combinatorial electrochemotherapy in glioma cells. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 3469–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushner, A.M.; Guan, Z. Modular Design in Natural and Biomimetic Soft Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9026–9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, W.Y.; Hauser, C.A. Short to ultrashort peptide hydrogels for biomedical uses. 17. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Gayakvad, B.; Shinde, S.D.; Rani, J.; Jain, A.; Sahu, B. Ultrashort Peptides—A Glimpse into the Structural Modifications and Their Applications as Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5474–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Porras, M.; Cárdenas-Salas, J.; Álvarez-Escolá, C. Somatostatin Analogs in Clinical Practice: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- berg, K.; Lamberts, S.W. Somatostatin analogues in acromegaly and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: past, present and future. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2016, 23, R551–R566. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, G.; Mazziotti, G.; Rotondi, M.; Iorio, S.; Doga, M.; Sorvillo, F.; Manganella, G.; Di Salle, F.; Giustina, A.; Carella, C. Long-term effects of lanreotide SR and octreotide LAR® on tumour shrinkage and GH hypersecretion in patients with previously untreated acromegaly. Clin. Endocrinol. 2002, 56, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, M.; Santoro, A.; Buonocore, M.; Crivaro, C.; Funicello, N.; Saponetti, M.S.; Ripoli, C.; Rodriquez, M.; De Pasquale, S.; Bobba, F.; et al. A New Approach to Supramolecular Structure Determination in Pharmaceutical Preparation of Self-Assembling Peptides: A Case Study of Lanreotide Autogel. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouget, E.; Fay, N.; Dujardin, E.; Jamin, N.; Berthault, P.; Perrin, L.; Pandit, A.; Rose, T.; Valéry, C.; Thomas, D.; et al. Elucidation of the Self-Assembly Pathway of Lanreotide Octapeptide into β-Sheet Nanotubes: Role of Two Stable Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4230–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ren, H.; Peng, A.; Cheng, H.; Chen, J.; Xia, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, X. The Effect of RADA16-I and CDNF on Neurogenesis and Neuroprotection in Brain Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Cai, G.-H.; Liang, J.; Ao, D.-S.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.-H. Three-dimensional culture and clinical drug responses of a highly metastatic human ovarian cancer HO-8910PM cells in nanofibrous microenvironments of three hydrogel biomaterials. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Z. Design of a RADA16-based self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold for biomedical applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2019, 30, 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelain, F.; Luo, Z.; Rioult, M.; Zhang, S. Self-assembling peptide scaffolds in the clinic. npj Regen. Med. 2021, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankar, S.; O’Neill, K.; Bagot D’Arc, M.; Rebeca, F.; Buffier, M.; Aleksi, E.; Fan, M.; Matsuda, N.; Gil, E.S.; Spirio, L. Clinical use of the self-assembling peptide RADA16: a review of current and future trends in biomedicine. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9, 679525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serban, M.A. Translational biomaterials—the journey from the bench to the market—think ‘product’. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2016, 40, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, G.K.; Cho, A.; Sanii, B.; Connolly, M.D.; Tran, H.; Zuckermann, R.N. Antibody-Mimetic Peptoid Nanosheets for Molecular Recognition. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9276–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).